ABSTRACT

The representation of ethnic minorities is often investigated through the lenses of ethnic parties. Much less attention is paid to how parties belonging to the ethnic majority represent minorities. In particular, we know very little about why such parties nominate ethnic minority candidates on their lists in elections. This article aims to explain this process and focuses on the Roma candidates on ethnic majority party lists in the 2016 local elections in Romania. The study covers 289 party lists from 77 localities with a minimum Roma population of 1% from three different counties. The analysis proposes a supply-side approach that covers party and competition variables. The results indicate that the size of the party, the size of the Roma group and the presence of Roma parties in the electoral competition have an effect on the nomination of Roma candidates.

Introduction

The representation of ethnic minorities is often investigated through the lenses of ethnic parties. There is a consensus in the literature that ethnic parties aggregate and represent particular interests of minority groups and mobilise their support (Ishiyama Citation2009; Chandra Citation2011; Ishiyama and Stewart Citation2021). This literature focuses extensively on the characteristics of ethnic parties and regards the role of majority parties as marginal in the process. However, there are instances in which ethnic parties are either not formed, they are insufficiently developed to be strong competitors in elections, or they cannot be successful due to institutional arrangements, e.g. majoritarian electoral systems with low district magnitude (Norris Citation2004). Under these circumstances, the representation of ethnic groups can be ensured by majority political parties.Footnote1 One way to do so is through the nomination of minority candidates. So far, much attention has been devoted to candidate selection in either ethnic or majority parties. However, we know little about why candidates belonging to ethnic minorities are nominated on the lists of majority parties.

To address this gap in the literature, our article aims to explain what determines majority political parties to nominate Roma candidates on their lists in local elections in Romania. We focus on Roma, the second-largest and fastest-growing minority group, which has also been identified as the most under-represented minority group in Romania (Rostas Citation2009; Mcgarry Citation2010). Our study looks at Romania because of its large share of Roma population, its closed-lists proportional representation electoral system and its legislative framework oriented towards the inclusion of ethnic minority groups. The analysis is conducted at the local level because there is variation between political parties in terms of nominations and local politics is the primary level of interaction between political institutions and citizens. The analysis includes 77 localities with a minimum Roma population of 1% from three different counties (Galati, Iasi and Salaj) selected according to their total size of the Roma population.

Our analysis proposes a supply-side approach that covers party and competition variables. We argue and test for the effect of party size, leadership change, Roma parties running in election, strength of the competition and size of the Roma community on the likelihood of majority parties to nominate Roma candidates. We control for the size of the council and party re-nomination rate. Unlike previous studies that focus on macro (country/system) or micro (individual), our article uses a meso-level approach that looks at what happens within and between political parties. The macro-level of analysis is not appropriate because we seek to understand the variation of Roma nominations across counties within the same country. The micro-level of analysis is also not suitable because voters decide who gets elected, but they have little to say in the process of candidate nomination; voters can only elect what has been (pre)selected by parties. As such, we focus on the mediator of this relationship between the voter and the representative, namely the political party (Hazan and Rahat Citation2010).

The political representation of the Roma minority has been approached through ethnic lenses, either focusing on Roma ethnic parties or other types of institutionsFootnote2 (Sobotka Citation2001; Vermeersch Citation2007; Mcgarry Citation2010), the role of majority parties is not considered. There are two aspects that can question this perspective. First, the nomination does not equal representation since the candidates must be elected to provide representation. Second, even when it leads to minority representation, it is a ‘softer’ version because the monopoly of power of the majority population created ethnicized institutions that are governed by the norms and rules of the majority (Lowndes Citation2014). The political interests of Roma may be defined by what the majority considers to be important (Mcgarry Citation2014), which can discourage the representatives to act in the interests of the group they represent (Franceschet Citation2010; Verge and de la Fuente Citation2014) and thus create a direct effect on the marginalised communities (Cohen Citation1999). However, since the monopoly of power comes together with the exclusion of others, the gatekeepers to the elected office are important (Norris and Lovenduski Citation1995). Such a supply-side perspective sheds light on how majority parties perform their function of aggregation of interests, whose interests they represent and whether they are inclusive towards minority interests.

The article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature and formulates five testable hypotheses. The third section presents the research design with emphasis on the case selection, data and variables. The fourth section includes the statistical analysis and interpretation of results. The conclusions summarise the key findings and discuss the implications of this study for the broader field of study.

Theory and hypotheses

Research shows that ‘political parties are the main architects of parliamentary representation’ (Lilliefeldt Citation2012). The behaviour of political parties and political representation can be understood through an analysis of the ‘interaction of factors within the political system’ (Norris and Lovenduski Citation1993) because political parties do not operate in a vacuum. Their actions are constrained by both party external and internal conditions (Panebianco Citation1988). This article follows this path and argues that the nomination of Roma candidates by majority political parties can be explained through a combination of intra- and inter-party factors (Norris Citation2004, Citation2006; Kittilson Citation2006).

The argument can be briefly summarised as follows. Political parties are conservative organisations (Harmel and Janda Citation1994) that do not change their way of functioning easily. The nomination of candidates belonging to ethnic minorities is an important change. Traditionally, majority political parties defend the interests of the ethnic majority and are often inclined to ignore the interests of non-dominant groups (Bjarnegard Citation2013). In time, due to the lack of any contestation, these practices become the accepted way of doing things (Lowndes Citation2013) that create an ethnicized environment that provides more advantages to the individuals belonging to their own group. As the desires to be in power are the maxims of political power (Bjarnegard Citation2013) and appointing minority groups could mean a change from power over someone to power with someone, political parties may oppose nominating minority candidates.

Yet, reality shows that some political parties may include minority candidates under certain circumstances. They are more inclined to do so, especially when they face an external shock, such as electoral defeat (or danger of electoral defeat), which has a direct impact on their access to power (Harmel and Janda Citation1994). Political parties might have different goals (voting, office or policy seeking goals, see Strom Citation1990), but vote-maximisation goals ensure the realisation of the other two. As political parties care about votes and are sensitive to voters’ volatility, they will try to avoid this scenario of being in danger of losing votes and, even worse electoral defeat. As the access to power is conditioned by the votes of the electorate, political parties have to convince voters to maintain their loyalty towards them (Gherghina Citation2014). Consequently, political parties compete for votes. Earlier research shows how they use their organisation as means of communication and persuasion of voters (Adams, Merrill III, and Grofman Citation2005; Gherghina Citation2014). Consistent with this behaviour, in those areas with minority groups, political parties may seek to attract ethnic votes by appointing minority candidates. This strategic behaviour can be a function of party and competition characteristics, which are detailed in the following sub-sections.

Party characteristics

The party level characteristics that are likely to influence the nomination of Roma candidates by majority parties are party size and the existence of a new leader. To start with party size, this can reflect the party’s appeal to the electorate, better opportunities for communication and credibility based on past performance. Large parties – either in terms of organisation or electoral support – usually reach that level by appealing to multiple segments in the electorate. They build and augment their electoral support with messages targeted to broad audiences even when the campaigns or elections are polarising (Hansen and Kosiara-Pedersen Citation2017; Scarrow, Webb, and Poguntke Citation2017). They approach a variety of issues and hope that voters will either perceive them as competent in addressing them or associate them with these issues (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Tresch Citation2012). In their efforts, large parties cannot ignore particular groups in society because these can be mobilised by other competitors. For example, the electoral support for populists originates in segments of the electorate that do not find the messages of mainstream (and usually large) parties appealing. Consequently, large parties are likely to target ethnic minority groups and one way of doing so, in addition to programmatic appeals, is through the nomination of candidates belonging to that minority.

Large parties have better opportunities to communicate with voters compared to small parties. Political parties connect with voters using two types of linkages: elite and organisational level (Poguntke Citation2002). Elite level communication entails the use of traditional or social media (Kalsnes Citation2016). Large parties are better represented in office and gain more visibility in the media; they are in the spotlight because of their activities. Such an advantage remains important in spite of evidence indicating that small parties increasingly use social media to promote themselves (Magin et al. Citation2017; McSwiney Citation2021). Larger parties have more developed organisations that cover a broad territory and allow them to contact and mobilise large numbers of voters. This access to more resources for communication places large parties in a better position than small parties to advertise a potential nomination of an ethnic minority candidate. More precisely, if a large party nominates a Roma candidate, the communication channels will make this information quickly reach the members of the Roma community. With this advantage on their side, large parties are more likely to nominate a Roma candidate.

Large parties have more credibility due to their past performance. The high electoral support in previous elections (and the presence in central or local government) is a solid argument in favour of their competence in addressing issues. It is also a reason to claim the existence of a bond with specific segments of the electorate. In their case, it is likely to have a situation in which they are voted on the basis of their past performance rather than on ideological grounds (Seyd and Whiteley Citation2004). A judgment based on past performance may be more appealing to voters compared to ideology because the latter refers to promises, which may or may not be implemented (Clarke, Stewart, and Whiteley Citation2009). Equally important, past performance refers to deeds as opposed to ideological promises that require extensive information, which comes at a high cost for citizens (Birnir Citation2007; Bennett, Segerberg, and Knüpfer Citation2018). Consequently, the credibility based on past performance may drive large parties into nominating a Roma candidate. They would expect that such a nomination will be unlikely to affect their credibility on the side of the majority voters and may increase their credibility among the ranks of the ethnic minority voters.

The second party characteristic is a party leadership change. Party leaders continue to be crucial for contemporary parties for many reasons that relate both to the internal and external life of the party (Cross and Pilet Citation2016; Gherghina Citation2020). A change of leadership is relevant for political parties and can trigger a series of internal dynamics. One of these can be the nomination of candidates belonging to ethnic minorities. A new leader of a majority party is likely to favour the nomination of a Roma candidate on its lists for two reasons. First of all, a party that experiences leadership change may be characterised by a ‘broader commitment to change’ (Harmel and Janda Citation1994). Although parties adapt and gradually change as they pass from one stage to another depending on the external environment, changes of leadership happen in extraordinary circumstances (Harmel and Tan Citation2003). Parties resist change unless they face a necessity for change (Cross and Pilet Citation2016). As leadership change usually implies a clash between factions or at least certain disruption, the winning faction, together with the new leader, is likely to introduce changes to reflect its ideology and preferences (Harmel and Tan Citation2003) and to bring new ideas (Matland and Studlar Citation2004). New criteria for candidate selection or the targeting of specific segments of the electorate are likely to be included in the package of reforms that a new leader brings. Once in office, new leaders must show how different they are from their predecessors. Political parties that recently passed through party leadership changes might need to re-connect with their voters. The electorate may not automatically consider the new leader trustworthy or efficient, thus the risk of electoral instability is higher (Gherghina Citation2014; Cross and Pilet Citation2016).

Party leaders who have their position for a long time might be less inclined of making any change due to different reasons. Their continuity in office suggests both a good connection with party members and voters, and low leadership contestation. This makes leaders more confident in their style of leadership and are not motivated to change things. Moreover, the norms and practices (Searing Citation1991; Lowndes Citation2014) that guide parties that favour majority candidates, adding minority candidates might not be considered a suitable strategy. Following all these arguments, we hypothesise that the nomination of Roma candidates by majority political parties is more likely to occur in the case of:

H1: Large parties.

H2: Party leadership change.

Competition variables

There are three competition variables that can influence the nomination of Roma candidates by majority parties: the presence of a Roma party in elections, the strength of electoral competition and the size of the Roma population among the electorate. To start with the presence of a Roma party, in electoral competition, ethnic political parties have advantages over majority political parties in mobilising the ethnic electorate. Traditionally, ethnic parties serve the interests of ethnic groups and derive their support from that group (Horowitz Citation2000). As ethnic political parties promote exclusive claims, it makes them own the ‘ethnic issues’, providing them with certain electoral advantages when it comes to the ethnic electorate, which becomes a group exclusively devoted to them (Chandra Citation2011; Ishiyama and Stewart Citation2021). As such, even when majority political parties address minority claims, there are higher chances that the ethnic voters will still support the ethnic parties (Chandra Citation2011). This happens mainly because the membership inside a group creates certain connections between members, making members of that group to favour the other members (Birnir Citation2007). Membership in a group has the function of the information provider. Consequently, the members of an ethnic group have higher changes to get and familiarise more with the policies of an ethnic party than of majority parties. As voters in general use information shortcuts to make their political decisions (Popkin Citation1991), to minimise the time spent to obtain political information, ethnic voters can use the knowledge of the other members of that group. Ethnic voters prefer to have their interests defended by those within their groups (Birnir Citation2007).

In the absence of ethnic parties, majority parties could target the ethnic minority for votes. These parties have the possibility to build a discourse of minority representation (Sobolewska Citation2013) in which they do not face the possibility of an in-group opponent. There is no ethnic outbidding in the classic meaning of the term (Rabushka and Shepsle Citation1972; Horowitz Citation1985), and majority parties can openly compete for the votes of ethnic minorities. The nomination of candidates belonging to the ethnic minority is one way in which majority parties can convey a strong message to the ethnic groups about how important their voice is.

Let us now turn to party competition. Many competitors increase the availability of the electorate and the costs of information gathering. Voters, especially those with little or no party identification, must spend more time informing themselves about the competitors because they do not have partisan cues to guide their decision (Mainwaring and Zoco Citation2007; Vowles Citation2013). With many competitors, voters will find it more difficult to distinguish viable from non-viable contenders and votes are divided between different political parties (Mair Citation1997; Moser Citation1999). Strong party competition also narrows the policy distance between competitors. If voters choose political parties that are closer to their own preferences, then they can easily switch parties (Madrid Citation2005; Ceron Citation2015). If voters choose those parties they perceive as best at promoting their interests, the limited competition provides little space for the promotion of different preferences (Mainwaring, España, and Gervasoni Citation2009).

Even if voters do not use policy positions in forming their preferences, a crowded electoral space provides more alternatives. When citizens are dissatisfied with specific parties, they can punish them by turning to other parties. Parties have more incentives towards responsiveness in a competitive contest (Gherghina Citation2014). In a competitive environment, the electoral market is more permeable, and parties may identify voters who feel that their preferences are not represented or are dissatisfied with the past performance of some parties. All these characteristics indicate that in a competitive election, political parties struggle more for votes. As such, they must find strategies that allow them to establish (or strengthen) their connection with voters. The nomination of a candidate belonging to ethnic minorities can be an advantage because it provides majority parties the possibility to expand their electorate, i.e. access to ethnic votes.

A third competition-related factor that may determine majority political parties to have minority candidates is the size of the minority (Saggar and Geddes Citation2000; Sobolewska Citation2013). Using the rational argument, majority parties nominate minority candidates if the benefits outweigh the costs. The benefits consist of the potential number of voters coming from the ethnic group of the candidate. The costs are the potential loss of votes among the majority voters who might stop voting for the party due to stereotypes or prejudices against the ethnic group. The size of the ethnic group provides parties with information about the potential gain in electoral support. Large ethnic minorities may catch the eyes of several parties, which may decide to compete for their votes. The result is that more majority parties may end up nominating minority candidates. Earlier research shows that political parties might encounter barriers in having minority candidates if the size of the ethnic group is small, i.e. shortage of supply. Large ethnic groups increase the likelihood to recruit candidates (Sobolewska Citation2013).

In line with these arguments, we expect that the nomination of Roma candidates by majority political parties to be more likely to occur when there is:

H3: No ethnic party in elections.

H4: Strong electoral competition.

H5: Large ethnic group.

Controls

In addition to these main effects, we test for the explanatory power of two control variables that may influence the nomination of minority candidates: re-nomination rate and size of the local council. The re-nomination rate is directly related to the literature highlighting the large number of advantages that incumbents over challengers (Norris and Lovenduski Citation1995; Stonecash Citation2008; Hirano and Snyder Jr Citation2009). There is evidence that office holders have higher access to resources, more visibility and usually better connection with voters. They can discourage challengers to compete and develop superior speech performance that may attract more voters (Hirano and Snyder Jr Citation2009). For all these reasons, political parties may favour incumbents over challengers. Along these lines, we would expect lower re-nomination rates of incumbents to increase the likelihood to nominate an ethnic minority candidate. However, this happens only if the minority candidates are challengers. If the candidates are incumbents, which is quite rare in practice in Eastern Europe, then higher re-nomination rates can contribute to their nomination. Also, previous research showed that voters vote for the party and not necessarily for the individual (Butler and Kavanagh Citation1992). Consequently, incumbency may not have a direct effect on the nomination strategy.

The size of the local council corresponds to what is in the literature known as the district size. Earlier studies show that the chances of minority candidates being appointed are proportional to the number of seats in a district (Matland and Taylor Citation1997). When the number of seats is limited, only powerful groups inside the party will have access to the nomination, leaving no room for the accommodation of other groups. In theory, large local councils give political parties more room for manoeuvre and thus increase the likelihood of ethnic minority candidates on their lists. However, the empirical evidence is mixed and reveals a limited effect in practice (Darcy, Welch, and Clark Citation1994).

Research design

To test these hypotheses, we use data from 289 party lists in 77 localities in three Romanian counties. Our unit of analysis is the party list in a locality (local constituency), which is a commune (several villages), a town or a city. The 2016 elections used a closed-list proportional representation. The county is the territorial administrative division in Romania, which includes one or several cities, several towns and many communes/villages. Romania includes 41 counties (plus the capital city) that differ in terms of population: Covasna is the smallest with roughly 200,000 inhabitants and Iași is the largest with almost 800,000 inhabitants. Considering the uneven distribution of the Roma population in the counties (between 1% and 8.5%), the high number of counties and the extensive primary data collection required, the research has been limited to three counties.Footnote3 In order to ensure variation, these three counties differ with regard to the total size of the Roma population: small (Iasi, 1.5%), medium (Galati, 3.2%) and large (Salaj, 6.7%), ethnic composition, economic situation, areas within the country, etc. In each of these counties, we selected all the localities with a Roma population higher than 1% to identify the lowest threshold necessary for Roma nomination.

The analysis focuses on five majority political parties with parliamentary representation in 2016. We select the national parties competing in local elections. to ensure comparability across counties and to identify general trends within the political system rather than isolated cases. Local elections may be particular in terms of electoral strategies, candidate selection procedures, patterns of competition. However, due to the cartelisation of Romanian politics (Gherghina Citation2016; Volintiru Citation2016), the national political parties remain, with some exceptions, the main players at the local level. In brief, the local level competition reflects the national level party system.

The five parties fielded candidates for local elections in most counties: Social Democrat Party (PSD), National Liberal Party (PNL), Alliance of Liberals and Democrats (ALDE), People’s Movement Party (PMP) and National Union for the Progress of Romania (UNPR). According to their statutes, all these parties decide about candidates in local elections exclusively at the local level. The decisions involve the party leader, the political bureau and in the cases of ALDE and PMP, also the party members. The interviews conducted with the members of all these parties in the three counties covered in this article confirm that this formal procedure is applied in practice.Footnote4 In spite of their general presence within counties, these parties did not field candidates in all 77 localities covered by this study. At one extreme PMP fielded in 33 localities. At the other extreme, PNL (76) and PSD (77) covered every locality. ALDE and UNPR covered two-thirds of the localities with 50 and 53 lists.

PSD is the largest political party in Romania, winning the popular vote in all but one local election. In the 2016 local elections, the PSD won the highest number of local councillors (41%), as well as mayors and county councillors. The PNL is the second-largest political party, with important oscillations in terms of electoral support over time. It has often run in electoral alliances, including one with the PSD in 2012. In the 2016 local elections, the PNL got almost 33% of the seats for local councillors. ALDE was formed in 2015 after the merger between the Conservative Party and the Liberal-Reformatory Party, a splinter from the PNL. At the local election in June 2016, it got third with 6% of the local councillor seats at the country level. PMP was formed in 2014 after a split within the democrat liberals and the newly formed party rallied around the former country president. In the 2016 local elections, it won around 3% of the seats for local councillors. UNPR was formed in 2010 by a group of parliamentarians who defected from PSD, PNL and the Conservative Party. In the 2012 elections, it was part of an electoral alliance together with PSD and PNL but ran on its own in the 2016 local elections and won roughly 3% of the local councillor seats. After these elections, it merged with the PMP.

The dependent variable, the nomination of Roma candidates on the lists of majority political parties is dichotomous, coded as 1 for the presence of Roma candidates and 0 for the absence. Party size (H1) refers to the percentage of local council seats won by a party in the 2016 elections. Since the localities have different council sizes (see below), the paper uses percentages as a relative measure to ensure comparability across localities. Change in party leadership (H2) refers to the substitute of the local party leader that took place between the 2012 and 2016 elections and was coded dichotomously: 0 for continuation in leadership and 1 if a party leader was elected in that time frame.

The Roma party (H3) is a count variable that reflects the number of Roma political parties running in elections. Its values range between 0 and 2 since there were no cases in which more than two Roma political parties competed in the same locality. Party competition (H4) is a count variable that reflects the effective number of political parties running in the local elections, which gained at least one seat. It is calculated using Golosov’s formula (Citation2010) because it is sensitive to both the number of competitors and to the share of seats won by the largest competitor. The Roma size (H5) is a count variable that indicates the percentage of the Roma population in the locality according to the results of the most recent national census 2011. It has values between 1% and 30%.

The size of the council refers to the total number of local councillors who can have according to the size of the municipality and are established by law. It ranges between 9 and 17 councillors. Re-nomination refers to the percentage of councillors who candidate again on the list of the same party. The percentage has been calculated using Gherghina’s (Citation2014) formula because it is sensitive to the number of candidates proposed by the party, the number of re-nominated councillors, as well as the size of the party. The value is calculated for each political party and has a value between 0 and 100.

The analysis uses binary logistic regression to test these effects. We ran three binary logistic regression models: Model 1 only with the party level variables, Model 2 with the party and county level variables and Model 3 including the controls (see Appendix 1).Footnote5 Before running the regression, we tested for multicollinearity and the results indicate no highly correlated predictors, i.e. the highest value is 0.54. This is also reflected by the values of the VIF test for multicollinearity, which are smaller than 1.59.

The nomination of Roma candidates: understanding the effects

The analysis starts with an overview of the number of Roma candidates and councillors on the lists of the five majority political parties in the 2016 local elections. Out of the 289 party lists fielded in local constituencies that have a Roma minority larger than 1%, only 29.2% of the lists include at least one Roma candidate. In these local constituencies, there are 128 Roma candidates (3.1%) of the total number of 3960 candidates running in the 2016 elections.Footnote6 This under-representation is valid for all three counties (). In Galati, the percentage of the Roma population in the localities with at least 1% ethnic minorities is 19.1%. There are 18 Roma candidates, which account for 2.4% of the total number of candidates in the entire county. Iasi, the county with the lowest proportion of Roma population (1.5% from the total and 7.7% among those localities with ethnic minorities), has 52 of Roma candidates. Although the raw number of candidates is considerably higher than in Galati, the percentage of Roma candidates is lower (4.8%) than the share of the Roma population. Salaj, the county with the highest percentage of Roma relative to the entire population (6.5%), has the highest number of candidates in the three investigated counties (58). Nevertheless, this is only 2.6% of the total number of candidates, which shows great similarity with the situation in Iasi.

Table 1. Roma candidates and share of population.

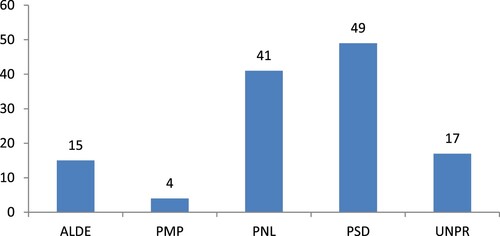

displays the distribution of Roma candidates across the five majority political parties in all three counties. These aggregate numbers are informative about important differences between the political parties. More fine-grained differences can be observed across counties, but that is beyond the goal of this article. The vertical axis represents the raw number of candidates, while the horizontal axis lists the parties alphabetically. Differences in the number of candidates are partially determined by the number of party lists fielded in the 77 localities investigated here. However, if the dynamic of the available number holds, this ranking would hold even if all parties field candidates in every locality. Most Roma candidates are on the PSD lists (49), which can be partially explained by the fact that the party has had in the past certain electoral alliances with Roma political parties at the national level. PNL nominated 41 Roma candidates, and the party also had in the past a connection to the Roma minority. Although there were no formal partnerships with the Roma parties, PNL had sent Roma representatives to the Romanian Parliament. Comparing the Roma nominations of the two large parties with the others, the number of Roma candidates is two times smaller for UNPR and ALDE and roughly ten times smaller for PMP.

Correlation and regression analysis

includes the correlation coefficients between the nomination of Roma candidates by majority parties and each of the five independent variables (H1–H5) plus controls. The results show empirical support for three independent variables, all statistically significant at 0.01. First, there is a positive correlation for H1 that indicates that larger parties nominate more Roma candidates compared to the smaller parties. The result is not surprising since the aggregate trend in had already pointed in that direction. The positive correlation for H3, although somewhat weak (0.16), indicates that the Roma candidates are nominated more in those localities in which Roma parties compete in elections. This effect goes against what the theory suggests, and we interpret it at length below. The strongest correlation is for H5, in which Roma candidates get nominated more in those localities with a larger size of Roma population.

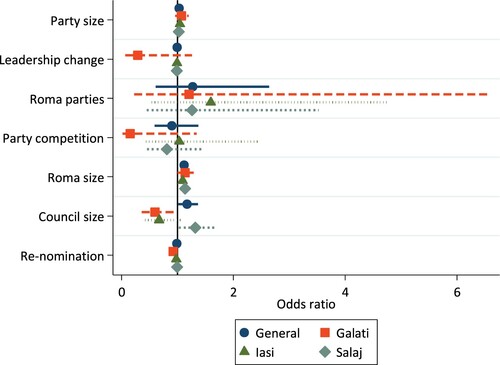

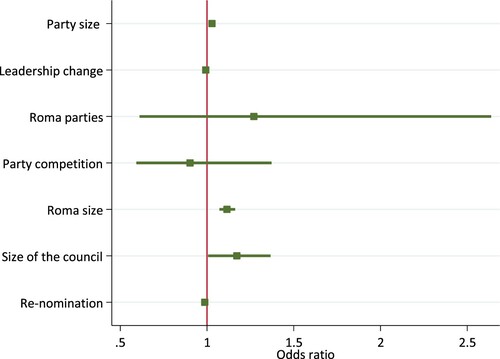

Figure 2. The effects on Roma candidate nomination (General). Note: The regression coefficients associated with the effects are presented in Appendix 1.

Table 2. The correlation coefficients with Roma nomination.

There is no empirical support for the hypothesised relationships between Roma nomination and leadership change (H2) or party competition (H4). The relationship goes in the opposite direction, the correlation coefficient is very weak, and none of them is statistically significant. With respect to controls, the size of the council is positively correlated to Roma candidates (0.08), not statistically significant. This shows that the Roma nominations are not more likely to occur in large localities. Similarly, a higher re-nomination rate is positively (but weakly) correlated with Roma nomination (0.07), not statistically significant. presents correlations also for individual counties to illustrate that the direction and strength of the correlation are similar across them. As such, the regression analysis uses only the general model for two reasons: from a substantive point of view, it reflects the situation in the counties, and from a methodological perspective, it includes an appropriate number of cases for statistical analysis. Appendix 2 illustrates how the effects of variables are similar across counties.

depicts the effects for the most comprehensive binary regression model (Model 3). Our interpretation refers to all statistical models, which are available in Appendix 1. Model 1 confirms the empirical support for H1, observable also in the bivariate correlations. Large political parties are more likely to nominate Roma candidates compared to the small parties. The effects are fairly limited but statistically significant at the 0.01 level. It is important to note that these results are consistent across the three models and confirm the theoretical expectations. One possible explanation for this result may be related to the recruitment potential. Small political parties, due to their limited organisational capacity, cannot field candidates in all elections and are not able to recruit effectively. Another explanation can be that small parties do not win many seats and thus, they fail to convince Roma candidates to run on their lists. A third potential explanation refers to how majority parties position themselves towards their electorate. The small parties may be afraid of not being appealing to the Romanian voters if they place Roma candidates on their lists, knowing the large number of stereotypes and prejudices against the Roma.

There is no empirical support for H2 in any of the models. The results are fairly inconsistent across the three models: in Model 1, leadership stability is slightly more likely to produce more Roma nominations, in Model 2, the leadership change is slightly more likely to lead to Roma nominations, while in Model 3, there is statistical independence. None of these are statistically significant. One explanation for this result is that the new leaders do not have candidate nominations as a priority on their agenda. Thus, even if a leadership change occurs, the likelihood for Roma nominees does not alter. Another possible explanation could be that both old and new leaders strive to nominate Roma candidates to a similar degree but for different reasons. For example, old leaders who benefit from their experience and previous success within the party have leeway in nominating Roma candidates. Regardless of the potential of a Roma candidate or about the reaction of the electorate, older party leaders can believe that their popularity can balance the electoral score. At the same time, new party leaders may wish to illustrate openness and nominate Roma candidates with the desire to become appealing to specific segments of the electorate. A third possible explanation is related to the party leader. It might be the case that other personal factors, such as norms or stereotypes, might be so widespread that they make party leaders not to choose Roma persons unless the electoral chances of winning of the party are low and the size of the Roma population could improve the electoral result.

Model 2 is a better fit for the data (pseudo R2 = 0.24) and adds important nuances to the broader picture. Although not statistically significant, the existence of Roma parties (H3) increases the likelihood of Roma nominations by majority parties by 1.3 times. For example, in each county there were cases when there was neither Roma political party competing nor mainstream political parties having Roma candidates, such as in Babeni or Balan (Salaj county), Liesti (Galati county) or Valea Seaca (Iasi county). The opposite can happen as well though, as in Dagata or Dolhesti (Iasi county), Ivesti or Movileni (Galati county) and Nusfalau or Agrij (Salaj county), where the effect goes against the hypothesised relationship. One possible explanation is that, contrary to the theories of ethnic voting, Roma groups might not necessarily give their electoral support only to Roma political parties just because they claim to defend only Roma interests. They might give the opportunity to majority political parties to persuade them, either because they are aware that Roma parties would have less power in the local councils in comparison with majority political parties or because in time they lost their trust in the capacities of Roma parties to defend Roma interests, as shown also by the decreasing support that Roma parties have had in the last years (Mcgarry Citation2010; European Roma Rights Centre Citation2012). As such, majority political parties may nominate Roma candidates to compete for the votes of the ethnic minority, which may undermine the long-term prospects for Roma parties to pass the electoral threshold or discourage them to run.

The results for H4 indicate that lower competition favours weakly the nomination of Roma candidates. The effect lacks statistical significance. One possible explanation for the absence of empirical support for H4 is that majority political parties find benefits in nominating Roma candidates both when there are both many and few competitors. The rationale behind their decision is somewhat different. When there are many competitors, there is a high likelihood that some of them would seek the support of the Roma minority. As such, majority parties are better off if they nominate themselves one candidate among the ranks of that ethnic group. When there are few competitors, every vote can make a difference, and in that situation, the majority parties could strategically target the electoral support of the minority by nominating a Roma candidate.

Finally, there is empirical support for H5. Political parties in municipalities where the size of the Roma population is large are 1.11 times more likely to nominate Roma candidates. The result is statistically significant and confirms previous studies according to which the chances of representation of minority groups are dependent on the size of that group (Saggar and Geddes Citation2000; Sobolewska Citation2013; Dancygier Citation2014). In the localities with a large Roma population, there are more majority parties with Roma candidates on their list. For example, in Lungani (Iasi county), where the Roma account for roughly 32% of the population, four out of the five political parties competing in the local elections have Roma candidates on their list. Another example is Sag (Salaj county), where there is a Roma population of roughly 20% all three majority political parties had Roma candidates on their lists. In these cases, the Roma as an important share of the population will create a contagion effect among the majority political parties, which will nominate Roma candidates. The size of the effect is not stronger because we have many parties with Roma candidates in localities where the Roma are a share of 1–2% in the population, e.g. Comarna (Iasi county), Dobrin or Letca (both in Salaj county). Similarly, in Umbraresti (Galati county), the Roma population is below 6% of the population, and both PSD and UNPR had a Roma candidate on their lists.

Model 3 confirms the explanatory power of the variables included in model 4, neither the size of the council nor re-nomination are statistically significant. The size of the council has an odds-ratio of 1.14, while the re-nomination rate has a negative effect on the nomination of Roma candidates (0.98). The presence of the two controls improves the fit of the model but to a limited extent.

Conclusion

This article explained why the majority of political parties nominate Roma candidates. The analysis included five political parties in 77 localities with at least 1% Roma population across three different counties in Romania. The findings indicate that large majority parties nominate Roma candidates more than other competitors. The elections organised in localities with a large Roma population and the presence of Roma parties in the electoral competition also increase the likelihood of Roma candidate nominations. These results point in the direction of an electoral strategic behaviour pursued by the majority political parties when nominating the Roma candidates. Two out of the three causes are characteristics of electoral competition. The size of the ethnic minority group can ensure greater benefits than costs if such nominations are pursued. The presence of ethnic parties determines the majority parties to compete for the share of ethnic votes and push for outbidding. The remaining driver of Roma nominations is organisational and refers to parties’ capacity to accommodate such candidates.

The implications of these findings reach beyond the case study analyzed here. At the normative level, the results provide important input for the theory of minority representation and some reflections about the broader idea of marginalised communities (Cohen Citation1999). Since the existence of large communities of Roma favours the nomination of Roma candidates, the majority of political parties represent these communities. This type of representation, although often derived from a strategic attempt to maximise votes, moves beyond ethnic lines. The Roma communities are represented both descriptively by candidates of Roma origin and substantively by mainstream parties that promote the group interests. Nevertheless, the story is more nuanced because the ethnic nominations of Roma are instrumental and misleading for representation. There is large disproportionality between the Roma group size and the number of nominated candidates. Majority of political parties use the possibility for descriptive representation as a symbolic act to gain leverage in the electoral competition. This illustrates how political parties act as gatekeepers and limit the representation of Roma communities to those they nominate on their lists. This has consequences for the quality of representatives because the parties nominate Roma candidates who are popular and can bring votes. However, there is little information about how the few Roma candidates selected by majority parties represent the communities in practice.

At an empirical level, the analysis shows the importance of factors related to potential electoral gains and organisational capacity in nominating candidates belonging to the ethnic minority. These have considerably more explanatory power compared to other variables such as a new party leader, the existence of strong competition or the size of the locality are much less relevant in the process of nomination. As such, they could form the basis for further analytical frameworks aimed at exploring the candidate selection in particular or the process of ethnic representation more broadly.

Further research could build on these findings and provide a more in-depth explanation of the patterns identified here. First, it is worth knowing if the presence of Roma candidates on the lists of majority political parties has an effect on the perception of the majority population about Roma, on the electoral strategies of other political parties or on the perceptions of the Roma about their political representation. Second, our study reveals a relationship between party organisation and the nomination of ethnic minority candidates. Future studies can approach seek to understand which aspects matter and how. Such an analysis could reveal the importance of both formal and informal aspects, especially that clientelism is widespread in many new democracies. Third, the strategic motivations for minority nomination can complement our findings. Future research could look into, for example, the extent to which the candidate selection norms and rules may influence the nomination of Roma candidates. This can be complemented with insights about the extent to which the Roma vote for Roma candidates to provide a full picture about the idea of minority representation at the local level.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article the terms ‘minority’ and ‘majority’ refer exclusively to groups in the population. Accordingly, “majority parties” stand for political parties that aim to represent the population that forms the majority in society.

2 This umbrella term covers a broad array of forms for Roma representation: non-government organizations, Roma activists or scholars, advisory and consultative bodies, government agencies, reserved seats, self-governments, lowered threshold, etc.

3 The counties were chosen randomly, however there are no reasons to believe that in similar counties the results would be different.

4 In November 2017, we conducted 39 semi-structured interviews with local leaders of the five parties in each of the three counties on the topic of candidate selection procedures.

5 We also run a four steps model, measuring party fixed effects at the third stage. The results show no significant difference compared to Model 3 and are not reported. The size of the Roma remains the only independent variable which has statistically significant effect and whose size remains mainly the same, while none of the political parties have a statistically significant effect.

6 The dependent variable of our study is the nomination of Roma candidates. Nevertheless, for the idea behind descriptive representation, it is worth mentioning that very few of the 128 Roma candidates were placed on electable positions. As a result, only 19 got elected in all three counties: four in Galati, 11 in Iasi and four in Salaj.

References

- Adams, J. F., S. Merrill III, and B. Grofman. 2005. A Unified Theory of Party Competition. A Cross-National Analysis Integrating Spatial and Behavioral Factors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., A. Segerberg, and C. B. Knüpfer. 2018. “The Democratic Interface: Technology, Political Organization, and Diverging Patterns of Electoral Representation.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (11): 1655–1680.

- Birnir, J. K. 2007. Ethnicity and Electoral Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bjarnegard, Elin. 2013. Gender, Informal Institutions and Political Recruitment. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Butler, D., and D. Kavanagh. 1992. The British General Election of 1992. London: Macmillan.

- Ceron, A. 2015. “The Politics of Fission: An Analysis of Faction Breakaways among Italian Parties (1946–2011).” British Journal of Political Science 45 (1): 121–139.

- Chandra, K. 2011. “What is an Ethnic Party?” Party Politics 17 (2): 151–169.

- Clarke, H. D., M. C. Stewart, and P. F. Whiteley. 2009. Performance Politics and the British Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen, C. 1999. The Boundaries of Blackness. AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cross, W., and J.-B. Pilet. 2016. The Politics of Party Leadership: A Cross-national Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dancygier, R. M. 2014. “Electoral Rules or Electoral Leverage? Explaining Muslim Representation in England.” World Politics 66 (2): 229–263.

- Darcy, R., S. Welch, and J. Clark. 1994. Women, Elections and Representation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- European Roma Rights Centre. 2012. “Challenges of representation: Voices on Roma politics, power and participation”.

- Franceschet, S. 2010. “The Gendered Dimensions of Rituals, Rules and Norms in the Chilean Congress.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 16 (3): 394–407.

- Gherghina, S. 2014. Party Organization and Electoral Volatility in Central and Eastern Europe: Enhancing Voter Loyalty. London: Routledge.

- Gherghina, S. 2016. “Rewarding the “Traitors”? Legislative Defection and Re-election in Romania.” Party Politics 22 (4): 490–500.

- Gherghina, S. 2020. Party Leaders in Eastern Europe: Personality, Behavior and Consequences. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Golosov, G. V. 2010. “The Effective Number of Parties.” Party Politics 16 (2): 171–192.

- Hansen, K. M., and K. Kosiara-Pedersen. 2017. “How Campaigns Polarize the Electorate: Political Polarization as an Effect of the Minimal Effect Theory Within a Multi-party System.” Party Politics 23 (3): 181–192.

- Harmel, R., and K. Janda. 1994. “An Integrated Theory of Party Goals and Party Change.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 6 (3): 259–287.

- Harmel, R., and A. Tan. 2003. “Party Actors and Party Change: Does Factional Dominance Matter?” European Journal of Political Research 42 (3): 409–424.

- Hazan, R. Y., and G. Rahat. 2010. Democracy Within Parties. Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hirano, S., and J. M. Snyder Jr. 2009. “Using Multimember District Elections to Estimate the Sources of the Incumbency Advantage.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 292–306.

- Horowitz, D. L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Horowitz, D. L. 2000. The Deadly Ethnic Riot. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Ishiyama, J. 2009. “Do Ethnic Parties Promote Minority Ethnic Conflict?” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 15 (1): 56–83.

- Ishiyama, J., and B. Stewart. 2021. “Organization and the Structure of Opportunities: Understanding the Success of Ethnic Parties in Postcommunist Europe.” Party Politics 27 (1): 69–80.

- Kalsnes, B. 2016. “The Social Media Paradox Explained: Comparing Political Parties’ Facebook Strategy Versus Practice.” Social Media + Society 2 (2): 1–11.

- Kittilson, M. C. 2006. Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments : Women and Elected Office in Contemporary Western Europe. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Lilliefeldt, E. 2012. “Party and Gender in Western Europe Revisited A Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Gender-balanced Parliamentary Parties.” Party Politics 18 (2): 193–214.

- Lowndes, V. M. 2013. Why Institutions Matter. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lowndes, V. 2014. “How Are Things Done Around Here? Uncovering Institutional Rules and Their Gendered Effects.” Politics & Gender 10 (04): 685–691.

- Madrid, R. 2005. “Ethnic Cleavages and Electoral Volatility in Latin America.” Comparative Politics 38 (1): 1–20.

- Magin, M., et al. 2017. “No TitleCampaigning in the Fourth Age of Political Communication. A Multi-Method Study on the use of Facebook by German and Austrian Parties in the 2013 National Election Campaigns.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (11): 1698–1719.

- Mainwaring, S., A. España, and C. Gervasoni. 2009. “Extra System Electoral Volatility and the Vote Share of Young Parties.” Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association.

- Mainwaring, S., and E. Zoco. 2007. “Political Sequences and the Stabilization of Interparty Competition: Electoral Volatility in Old and New Democracies.” Party Politics 13 (2): 155–178.

- Mair, P. 1997. Party System Change: Approaches and Interpretations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Matland, R. E., and D. T. Studlar. 2004. “Determinants of Legislative Turnover: A Cross-national Analysis.” British Journal of Political Science 34 (01): 87–108.

- Matland, R., and M. M. Taylor. 1997. “Electoral System Effects on Women’s Representation.” Comparative Political Studies 30 (2): 186–210.

- Mcgarry, A. 2010. Who Speaks for Roma? London: The Continuum International Publishing.

- Mcgarry, A. 2014. “Roma as a Political Identity: Exploring Representations of Roma in Europe.” Ethnicities 14 (6): 756–774.

- McSwiney, J. 2021. “Social Networks and Digital Organisation: Far Right Parties at the 2019 Australian Federal Election.” Information Communication and Society 24 (10): 1401–1418.

- Moser, R. G. 1999. “Electoral Systems and the Number of Parties in Postcommunist States.” World Politics 51 (2): 359–384.

- Norris, P. 2004. Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. 2006. “The Impact of Electoral Reform on Women’s Representation.” Acta Politica 41 (2): 197–213.

- Norris, P., and J. Lovenduski. 1993. ““If Only More Candidates Came Forward”: Supply-side Explanations of Candidate Selection in Britain.” British Journal of Political Science 23 (3): 373–408.

- Norris, P., and J. Lovenduski. 1995. Political Recruitment: Gender, Race, and Class in the British Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Panebianco, A. 1988. Political Parties: Organization and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poguntke, T. 2002. “‘Party Organizational Linkage: Parties Without Firm Social Roots?’.” In Political Parties in the New Europe, edited by K. R. Luther and F. Müller-Rommel, 43–62. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Popkin, S. L. 1991. The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasion in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rabushka, A., and K. A. Shepsle. 1972. Politics in Plural Societies: A Theory of Democratic Instability. Columbus: Charles Merrill.

- Rostas, I. 2009. “The Romani Movement in Romania: Institutionalization and (De)mobilization.” In Romani Politics in Contemporary Europe: Poverty, Ethnic Mobilization, and the Neoliberal Order, edited by N. Sigona and N. Trehan, 159–185. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Saggar, S., and A. Geddes. 2000. “Negative and Positive Racialisation: Re-examining Ethnic Minority Political Representation in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 26 (1): 25–44.

- Scarrow, S. E., P. D. Webb, and T. Poguntke. 2017. Organizing Political Parties: Representation, Participation, and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Searing, D. D. 1991. “Roles, Rules, and Rationality in the New Institutionalism.” The American Political Science Review 85 (4): 1239–1260.

- Seyd, P., and P. Whiteley. 2004. “British Party Members.” Party Politics 10 (4): 355–366.

- Sobolewska, M. 2013. “Party Strategies and the Descriptive Representation of Ethnic Minorities: The 2010 British General Election.” West European Politics 36 (3): 615–633.

- Sobotka, E. 2001. “Political Representation of the Roma : Roma in Politics in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland.” Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe 2 (1): 1–58.

- Stonecash, J. M. 2008. Reassessing the Incumbency Effect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strom, K. 1990. “A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties.” American Journal of Political Science 34 (2): 565–598.

- Verge, T., and M. de la Fuente. 2014. “‘Playing with Different Cards: Party Politics, Gender Quotas and Women’s Empowerment’.” International Political Science Review 35 (1): 67–79.

- Vermeersch, P. 2007. The Romani Movement : Minority Politics and Ethnic Mobilization in Contemporary Central Europe. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Volintiru, C. 2016. “Clientelism and cartelization in post-communist Europe: The case of Romania.” London: Doctoral dissertation, The London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Vowles, J. 2013. “Campaign Claims, Partisan Cues, and Media Effects in the 2011 British Electoral System Referendum.” Electoral Studies 32 (2): 253–264.

- Walgrave, S., J. Lefevere, and A. Tresch. 2012. “The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (4): 771–782.