ABSTRACT

For active internet users, exposure to racist content has become commonplace. However, little scholarly attention has been given to experiences of racism online. Building on a qualitative study, this article examines how young Muslims in Norway make sense of online racism and hateful content targeting their group identities. The article develops an analytical framework for studying lay understandings of online racism by analysing how young Muslims understand the a) nature, b) experience and c) causes of online racism. The analyses show that online racism appears distinct from common descriptions of contemporary racism that emphasise the subtle, covert and ambiguous nature of everyday racism. In contrast, online racism is understood to be massive and overt, but the nature of online communication creates a sense of control and distance for both the targets and perpetrators. The young Muslims’ ‘theories’ of the causes of online racism differ along two dimensions: the perceived intentionality of the perpetrators and the ordinary or exceptional nature of racism, yielding four distinct understandings of what online racism reflects: a racist Norway, exceptional racism, trolling and ignorance. This article argues that we cannot ignore the online sphere when seeking to understand everyday experiences of racism.

Introduction

The internet and social media have become a central arena for spreading racist content and hate speech (e.g. Foxman and Wolf Citation2013; Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas Citation2021). A common explanation is that the online sphere lowers social barriers, allowing people to write things they would otherwise not express in public (Hutchens, Cicchirillo, and Hmielowski Citation2015; Moor, Heuvelman, and Verleur Citation2010). The result is that for active internet users, exposure to racist content has become commonplace.

Scholarly and public attention has increasingly been paid to the everyday experiences of exclusion that people of minority backgrounds face based on their skin colour, phenotypical characteristics or (ascribed) ethnic, national or religious background. These experiences are often referred to as everyday racism (cf. Essed Citation1991). Numerous studies and theoretical contributions have shown how such everyday acts tend to come in the form of subtle and ambiguous experiences of stigmatisation and discrimination (Lamont et al. Citation2016; Sue Citation2010). It is common to understand this type of subtle and covert exclusion as characteristic of contemporary forms of racism, in contrast to the ‘old’ racism, which was expressed in more direct, overt and explicit ways (e.g. Bonilla-Silva Citation2017; Sue Citation2010).

However, the literature on everyday experiences of racism has largely overlooked the online sphere. As we spend an increasing amount of time online, this space has become a central part of our daily lives, particularly for young people (Auxier and Anderson Citation2021). In the online sphere, ‘old-fashioned,’ overt racism is still highly present, meaning that young people belonging to racialised groups regularly confront hateful rhetoric targeting their group identities (Eschmann Citation2019; Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas Citation2021; Ortiz Citation2021). Still, we have little knowledge about how members of targeted groups experience and understand hate and racism online (Bliuc et al. Citation2018).

In this article, I ask how young Muslims in Norway make sense of the racist content they encounter online. As Muslims in the Norwegian context, these young people belong to a racialised group that is typically ascribed a position as both ethnic and religious ‘other’ and is a common target of hate speech (Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022; Garner and Selod Citation2015). Building on Essed’s work (Citation1991) on ordinary people’s knowledge of racism, I develop an analytical framework for studying lay understandings of online racism, and analyse how young Muslims understand the a) nature, b) experience and c) causes of online racism.

This article makes two main contributions to the research literature. First, and empirically, it helps fill a notable research gap by studying lay understandings of racism in the online sphere, analysing how the (potential) targets of online racism understand and make sense of the phenomenon. Second, and theoretically, it develops an analytical framework for analysing cognitive understandings of racism, which can serve as a fruitful point of departure for future analysis.

Contemporary racism and Islamophobia

In analysing the nature of contemporary racism, the research literature typically describes a historical shift away from overt, blunt, hostile, segregationist and supremacist expressions of racism to more covert and subtle expressions. Both empirical and theoretical contributions emphasise how contemporary manifestations of racism are often subtle, indirect and ambiguous, operating below the level of conscious awareness (e.g. Bonilla-Silva Citation2017; Coates Citation2011; Lamont et al. Citation2016; Sue Citation2010). In their comparative empirical study of experiences of racism, Lamont and colleagues (Citation2016) show how people often experience racism through subtle incidents of stigmatisation, assaults on their worth or being assigned low status. Such incidents can take the form of microaggressions, which are ‘brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain people based on their group membership’ (Sue and Spanierman Citation2020, 36). As experiences of racism are often subtle, indirect and ambiguous, they can be difficult to identify, causing targets to become insecure about their interpretation of the situation and spend significant energy determining if the incident is related to their racial or ethnic background (Lamont et al. Citation2016; Sue and Spanierman Citation2020).

Such microaggressions and subtle experiences of exclusion constitute everyday experiences for many racialised individuals (Lamont et al. Citation2016; Sue and Spanierman Citation2020). In her influential account, Essed (Citation1991) understands everyday racism as manifestations of racism that occur through systematic, recurrent and familiar practices in everyday situations. Such experiences of racism often go unnoticed and unacknowledged because they become so familiar in daily situations (Sue and Spanierman Citation2020). Although everyday experiences of racism can be subtle and appear insignificant, when experienced frequently by racialized individuals, they cumulate to have a great impact on their victims (Sue and Spanierman Citation2020).

Numerous studies document that Muslims are subject to exclusion and discrimination (see Rehman and Hanley Citation2023 for an overview). Religion forms a ‘bright’ boundary in the European context, with Muslims and Islam being the ultimate ‘other’ (Alba Citation2005). While the term Islamophobia is often used to describe the exclusion and discrimination that Muslims experience, there are ongoing debates about the term and whether it should primarily be understood as religious intolerance or an expression of cultural racism (Bravo López Citation2011). Many scholars argue that the Islamic identity has been subject to a process of racialisation where it is assigned an inferior position in the societal hierarchy and where individuals are ascribed a set of characteristics seen as inherent to the members of the group ‘Muslims’ based on both physical and cultural traits (Garner and Selod Citation2015). The racialisation of Muslims means that the religious identity, which is in principle voluntary, becomes ascribed and thus compulsory (Bravo López Citation2011).

Much in parallel to the insights from the scholarship on experiences of everyday racism, empirical studies find that Muslims experience various subtle and overt forms of hostility. Muslims frequently experience negative stereotyping which dehumanise Muslims as ‘other’ and an enemy to be feared (Bravo López Citation2011; Rehman and Hanley Citation2023). Based on a qualitative study of young Muslims in Norway, Ellefsen and Sandberg (Citation2022:, 2602) conclude that ‘anti-Muslim hostility most frequently surfaces in incidents and comments that are part of the everyday lives of Muslims’, in experiences of hate speech, discrimination and hostility. At the same time, Muslims’ experiences of exclusion and rejection are shaped not only by their religious affiliation, but often also by being identified as non-white and in terms of their non-European descent and perceived culture (Modood Citation1997). Thus, it is not always possible to disentangle whether an experience of exclusion is based on an individual being identified with a ‘Muslim threat’ or on being identified as a foreigner or an ethnic other (Bravo López Citation2011). Although considerable scholarly attention has been paid to the nature of contemporary experiences of racism and Islamophobia, the specific nature of these experiences in the online sphere remains largely unexamined.

The online sphere

The digital realm has become significant for spreading more or less explicit racist content (Foxman and Wolf Citation2013; Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas Citation2021), and there is growing attention to ‘cyber-racism’ (Bliuc et al. Citation2018). While the internet is exploited by organised racist groups to strengthen their position and disseminate racist rhetoric, much of the racist content online appears to stem from individuals who do not act on behalf of organised interests (Bliuc et al. Citation2018). Scholars have shown how characteristics of digital communication, such as the lack of social cues, a sense of anonymity and group dynamics lower social barriers and enable people to express themselves in ways that they would not do otherwise (e.g. Hutchens, Cicchirillo, and Hmielowski Citation2015; Moor, Heuvelman, and Verleur Citation2010). Furthermore, the algorithms that determine what we are exposed to online tend to favour content that elicits strong reactions and emotions, thus often favouring and promoting racist material (Papacharissi Citation2015).

Internet users can be exposed to online racism by observing racist content or by receiving racist comments directly targeting them. Studies indicate that among Norwegian internet users it is relatively uncommon to have experienced direct and personal racist harassment, but ethnic and/or religious minorities are more at risk of harassment than others (Fladmoe and Nadim Citation2017). However, internet users frequently observe racist content online (Fladmoe, Nadim, and Birkvad Citation2019), to the extent that scholars argue that exposure to racist content has become an everyday experience (Eschmann Citation2019; Ortiz Citation2021).

Most research on online racism to date has relied on content analysis of online texts and analysis of the online behaviour of groups and individuals (Bliuc et al. Citation2018). Some survey-based studies have also examined experiences with online hate speech and harassment (e.g. Fladmoe and Nadim Citation2017; Nadim and Fladmoe Citation2021). However, empirical studies that examine the subjective experiences of the targets of online racism are sparse (Bliuc et al. Citation2018; but see Eschmann Citation2019; Gin et al. Citation2017; Ortiz Citation2019, Citation2021). One notable exception is the study by Ortiz (Citation2021) of young people’s experiences and perceptions of online racism in the United States. She finds that even overtly racist content and racial stereotypes are not considered true racism because they occur online – a social domain deemed less ‘real’ by both the targets of racism and outsiders (Ortiz Citation2019, Citation2021). These findings raise the question of how people understand and make sense of online racism. Although exposure to online racism is becoming a prevalent experience as we spend an increasing share of our lives online, we have little knowledge about how people experience and understand racism online (Bliuc et al. Citation2018) and how online experiences of racism differ from the offline experiences commonly studied (Ortiz Citation2021).

Making sense of online racism

Empirical research on subjective experiences of racism has largely focused on detailing specific incidents of racism or microaggressions and the resulting responses, reactions and consequences (e.g. Ellefsen and Sandberg Citation2022; Harris et al. Citation2012; Lamont et al. Citation2016). In this article, however, I am concerned with how ordinary people understand and make sense of online racism. This means that I consider the everyday meaning-making processes whereby young people create sense and understanding from the hateful rhetoric targeted at groups to which they belong. Everyday meaning-making provides the cognitive representations through which we categorise, understand and give value to the world. In the words of Jovchelovitch (Citation2007), it helps ‘tame’ the object world, making the unfamiliar familiar and manageable and allowing us to create lay theories of phenomena like racism. It gives tools and guidelines not only for how we interpret specific incidents and situations but also for how we react and act.

In her analysis of Black women’s ‘general knowledge’ of racism and their cognitive representations of race, ethnic relations and racism, Essed (Citation1991) distinguishes between descriptive knowledge about the nature of racism and explanatory knowledge, which consists of ‘theories’ of causes and functions of racism. She explicates a range of components that constitute ordinary peoples’ knowledge of racism, including notions about the nature of racism, its agents, processes, structuring factors, context and stereotypes, as well as strategies to counter it (Essed Citation1991, 106). I build on Essed’s descriptions of these components to develop an analytical framework for studying lay understandings of online racism, focusing on three components:

The nature of online racism. How do targets of racism understand the scope, content and expressions of online racism?

The experience of online racism. How do targets understand online racism as an experience? What constitutes a personal experience with online racism and what is specific to the experience of online versus offline racism?

‘Theories’ of online racism. How do people understand the causes of racism? What is the relationship between racism in the online and offline worlds, and who are the agents of racism?

Analysing these three components, this article comprises an empirical investigation into young Muslims’ understandings of online racism. The young Muslims in the study rarely distinguish between ethnic, racial and religious background as the target of hostility, and see these characteristics as interchangeable in racialised hostility (see also Garner and Selod Citation2015). Consequently, I use the term ‘online racism’ as a broad concept that includes online content that denigrates individuals and groups because of their skin colour, phenotypical characteristics or (ascribed) ethnic, national or religious background. However, the respondents occasionally slip between talking about phenomena like online racism or islamophobia and online harassment more generally. I understand online racism to be a form of hate speech, which can be distinguished from phenomena such as online harassment and trolling in that it targets its victim as a (perceived) member of a (racial/ethnic/religious) group rather than as an individual (cf. Fladmoe and Nadim Citation2017; Perry Citation2001). The study provides new insights into how targets of online racism understand and make sense of racism in the online sphere, which is both central to their everyday lives and potentially construed as something other than the real world (Ortiz Citation2019).

About the study

The study is based on qualitative interviews with 20 young Muslims in Norway, aged 19–29. The sample consists of 10 men and 10 women who identify as Muslim. While more than half of the sample live in Oslo, Norway’s capital city, the rest live in smaller cities or towns throughout the country.

The respondents were recruited by a market research institute (which was already responsible for a related survey in the main project that this study is part of). They created a Facebook advertisement calling for ‘participants who observe or participate in debates online’ for an interview, offering a gift certificate (NOK 500, approximately 50 euros). Respondents filled out a short survey intended to identify relevant participants. The criteria for inclusion were a) being aged 18–30; b) stating Islam as a religious affiliation and c) having observed hostility towards Muslims or immigrants online in the past three months. Respondents were also asked about their own online activity to ensure that the study included both participants active in online debates and those less active.

In addition to recruiting through the Facebook advertisement, the market research institute used its network of interviewers to recruit potential respondents, who were subsequently screened in the same manner described above.

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (ref 564101). In accordance with the ethics approval, the respondents gave oral consent to participate after volunteering to participate and having received information about the study, which was introduced as an inquiry about social media use and online debates.

Like most young people, the young Muslims in this study spend a substantial amount of time online, and they all follow news and debates on topics related to immigration, integration and religion, albeit to differing extents. As mentioned, the study was designed to capture both respondents who actively engage in online debates and those who do not. Nine of the respondents can be characterised as active participants in online debates. The most active respondents regularly engage in online discussions in social media or in the comments sections of news media. Some are active in politics and also participate in debates in traditional media. Others occasionally post comments and participate in online debates. Eleven of the respondents seldom or never participate in online debates, but they follow, read and occasionally react, such as with ‘likes’.

Although the respondents were screened to ensure that they had some experience with online racism, the extent to which they have been direct targets of online attacks varies. While the respondents most active in online debates regularly experience being targeted online, most of the respondents who have experienced being the direct target of online hostility describe one or a few such instances, typically after posting a comment or becoming visible in a news segment. The level of exposure to direct attacks among respondents is tightly linked to their online visibility. Nevertheless, some respondents who do not engage in online debates also describe being direct targets of online racism, such as by receiving racist comments from school peers or other acquaintances in private messages or private groups online.

All interviews were conducted by the author in May 2020. Due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, and to secure a broad geographical reach, the interviews were conducted digitally via Zoom. With a few exceptions, the respondents had the camera on, and the sound from all interviews was recorded and fully transcribed. The interviews lasted approximately an hour and covered topics such as personal online activity, negative experiences linked to the respondents’ ethnic or religious background both online and offline and the respondents’ perception of hostility towards ethnic and religious minorities in Norway. The interviewer did not use the term racism until the respondents introduced it or until later stages in the interview when asking if the respondents considered the type of online content they were talking about to be racist. Cognitive representations of online racism were analysed by tracing descriptive and explanatory statements about racist rhetoric and content online and exploring the understandings of online racism that emerge in implicit and explicit comparisons with offline instances of racism.

Normalised overt racism

To start the analysis, I examine the young Muslims’ descriptive understandings of the nature of online racism and ask how they understand its scope, content and expressions.

The young Muslims in this study unanimously describe online racism as commonplace and widespread in Norwegian comments sections and social media. They portray online debates as full of negative stereotypes about, and clear hostility towards, ethnic and religious minorities, particularly towards people with a visible immigrant background and those presumed to be Muslim. As one male respondent bluntly sums up, they experience the problem of online racism and Islamophobia as ‘very, very, very large. Very large’.

The respondents regularly use terms like ‘racist’ and ‘racism’ to describe what they encounter online, either spontaneously or when asked directly whether the terms are relevant. When describing the content of online debates, they seldom distinguish between hostile rhetoric directed at ethnicity, nationality and skin colour and that directed at religion. They tend to group negative rhetoric towards all such characteristics, terming it ‘xenophobic’, ‘prejudiced’ and/or ‘racist’, and experience the different types of hostility as more or less interchangeable. For instance, one of the most active respondents in the study, a young woman engaged in youth politics, describes her experience of becoming a target in the comments sections:

I have felt how I get it in the comments sections, and that people get really fixated on my ethnic background. And there are those who just assume my religious background and play with that. I wrote an opinion piece in [a national newspaper] two days ago, and there are almost 80 Islamophobic comments that are fixated on how I’m not Norwegian.

The inevitable nature of online racism is central to the young Muslims’ descriptions of the phenomenon. They appear to take as given that making oneself visible online, for instance, by posting comments, exposes one to direct racist attacks. As one respondent explains: ‘[…] when you post stuff, people are going to talk crap. That’s just the way it is’. Similarly, when a young man is asked if he has ever received unpleasant comments online because of his background, he replies: ‘Not without reason, but if I have commented on a post’. He thus implies that commenting online is a ‘reason’ for being attacked. While respondents who have been the target of racist comments attribute these experiences to commenting online, those who have not experienced personal attacks attribute it to their limited online exposure. In other words, both the young Muslims who are active online and those who are not share an understanding of the nature of online racism as unavoidable if you make yourself visible through posting comments, although their personal experiences with online hostility differ. As one woman concludes: ‘If others are [attacked] in the comments’ section, I’ll be as well’. Thus, the young Muslims in this study unanimously perceive online racism as prevalent and widespread (scope) and as an overt and unambiguous form of racism (expression) that targets ethnic and religious ‘difference’ almost interchangeably (content). The scope and inevitable nature of online racism mean that for these young Muslims, who spend a significant amount of time online, exposure to overt racism becomes an everyday and almost normalised aspect of their digital lives (cf. Ortiz Citation2021).

Experiencing racism online: the buffers of the online sphere

I now turn to how the young Muslims understand online racism as an experience: what constitutes a personal experience with racism, and what is particular about experiencing racism in the online sphere?

Online, the respondents most often encounter racism indirectly, by witnessing xenophobic, racist or Islamophobic content or attacks against other (perceived) ethnic and/or religious minorities. Although the racist and Islamophobic content they encounter typically does not target them directly, they understand these indirect experiences as a personal experience of racism. As one respondent says: ‘They’re kind of writing about you, if you know what I mean?’ Another respondent emphasises:

I know that that person [writing comments] doesn’t see the difference between me and the person they are directing this comment at. That rhetoric applies to me as well.

In detailing their understandings of online racism, the young Muslims explicitly and implicitly compare online experiences with offline experiences. Although the respondents perceive the racism that they encounter online as overt, explicit and even extreme, the fact that it happens online appears to buffer the sense of severity. The respondents describe this buffering occurring in three main ways.

First, the informants experience that racist comments online do not target them personally in the same way as comments they receive face-to-face. For instance, one of the women explains that when she is attacked online, she feels that she is ‘simply’ attacked as a member of a group; as an ‘immigrant’ or ‘Muslim’ rather than as an individual. In offline settings, however, she becomes uncertain about whether the hostility she experiences is about her as a person: ‘And that’s why it gets me – because I never understand if this is personal, against me, or is it because I look like I do?’ For her, the unambiguous and impersonal nature of online racism is easier to handle than the more subtle and ambiguous offline experiences, which create a greater sense of doubt and uncertainty (cf. for instance Salvatore and Shelton Citation2007). Other respondents argue that online, and in particular on platforms in which they do not appear with their full name and picture, it is really their avatar or internet persona that is attacked, rather than themselves. The nature of online communication appears to create a sense of distance that makes racist attacks become experienced as less personal.

Second, the unknown identity of the senders of online racism contributes to a further sense of distance but can also be experienced as threatening. As one woman says: ‘How seriously should you take someone behind the screen, who you don’t know and who doesn’t have a clue who you are?’ The respondents portray the perpetrators of online racism as an undefined mass, from which they can more easily distance themselves than a flesh-and-blood person standing in front of them. At the same time, several of the respondents point to examples of people who have been radicalised online and committed violent or deadly attacks and find the anonymity of the online sender threatening:

You know that people hate you, but you don’t know who that person is. Perhaps you’re at the wrong place at the wrong time, and someone decides to kill you. Or decides to attack you.

Third, the respondents’ experience of the severity of online racism seems to be buffered by a sense of being able to control their exposure to online racism. Although they understand online racism as inevitable in being widespread, massive and an unavoidable consequence of making oneself visible online, an important characteristic of the online sphere is that one can log off. As one respondent says: ‘When I read it, I feel I can stop at any time […]. I can just turn off and exit the comment section and not read on’. Online, they can choose the extent to which they want to engage with – and expose themselves to – racism and hate speech. Offline, however, racist incidents typically catch them off guard in interactions where they are not prepared. Moreover, the respondents highlight that online one has time to think about how to react and can choose to simply ignore racist talk.

Furthermore, the respondents feel that they can choose the extent to which they are exposed through their own online behaviour. By avoiding drawing attention to themselves by posting comments or engaging in online debates, they avoid exposing themselves to direct racist attacks. Consequently, many respondents describe being cautious in posting comments or expressing their opinions publicly (in line with what we find in other studies, e.g. Fladmoe and Nadim Citation2017).

In sum, the young Muslims in the study are in unison in how they understand online racism as an experience. Although they have an inclusive understanding of what constitutes a personal experience with online racism and experience online racism as more explicit and extreme than typical racist incidents offline, the nature of online communication creates a sense of distance which makes online racism easier to handle than offline experiences. The distance of the online sphere seems to create a sense of depersonalisation through which the respondents do not feel personally targeted and find it easier to distance themselves from the faceless mass of perpetrators. Furthermore, the respondents experience a sense of control over their exposure and reactions to online racism, even if this control entails logging off from a central arena of their everyday lives.

‘Theories’ of online racism

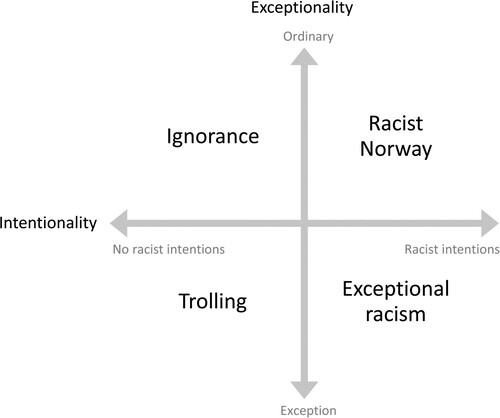

In this section, I examine the respondents’ explanatory understandings of the causes of online racism – or their ‘theories’ of online racism (cf. Essed Citation1991). I do so by analysing their understandings of the agents of online racism and of the relationship between racism in the online sphere and in wider Norwegian society. In analysing the respondents’ theories of online racism, two analytical dimensions emerged as central: intentionality and exceptionality. Intentionality refers to the extent to which the respondents understand online racism as reflecting racist intentions at the individual level. Exceptionality refers to the societal level and the extent to which online racism is understood as an exception in an otherwise non-racist society or as being ordinary and reflecting Norwegian society. An exceptional understanding of racism connects racism to isolated and extremist groups or events or to the results of ‘extraordinary’ behaviour (Goldberg Citation2009). In contrast, understanding racism as ordinary entails understanding it as intertwined in everyday practices, structures and institutions. While the interview guide included questions aimed at capturing the exceptionality dimension, the intentionality dimension was developed inductively as it was a central distinction in the respondents’ descriptions of the agents of online racism.

illustrates how these two analytical dimensions capture the distinctions between different explanatory understandings of racism in the empirical material. These understandings of online racism are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and the respondents sometimes draw on different understandings of online racism in different parts of the interviews.

In the upper right corner of , we find an understanding of online racism as ordinary and intentional. As the respondents generally hold that racist content online is produced by ‘ordinary people’, many respondents perceive online racism as reflecting the views of ordinary Norwegians. A male respondent elaborates:

My impression is that it is ordinary people who do it. I used to think that it was dark figures, but people who comment are people you could meet on the street. So, it’s the common guy on the street who comments stuff like that.

Furthermore, many respondents understand the internet as an arena in which people dare say what they really think and feel because of the social distance and potential for anonymity. For instance, a male respondent explains that he generally experiences Norwegians as friendly, but the online sphere gives a completely different impression:

Online, I feel you can see what people really feel. Then I see, ‘Wow, there are lots of people who … ’ There’s a lot of hate, I haven’t seen that before. Wow, there are lots of nasty, bad things, threats … Lots of really serious things online that I don’t see in my everyday life. Because people dare to write what they really mean.

I feel that you get a completely different impression of society online versus the real world. What do people really think when they don’t dare to say things in real life but are really harsh online? I makes me sceptical of what people really think and I get a different impression of society than if the internet hadn’t existed and I had only taken into account what happens in the real world.

One understanding of online racism is, therefore, that it reflects and reveals the covert attitudes and sentiments that exist in Norwegian society and that the online sphere offers the true picture of the extent of racist attitudes. This view entails understanding online racism as intentional (revealing true sentiments) and ordinary (reflecting common sentiments). It might be that the ties between the online and offline worlds are perceived as particularly strong in a small language community such as the Norwegian, where the racist online content the respondents refer to are written by a small Norwegian-speaking population.

While about half of the respondents see online racism as reflecting general racism in society in some way, the rest hold that the racist content online gives a skewed impression of Norwegian society. In the bottom-right corner of , we find an understanding of online racism as intentional but exceptional. This view entails perceiving online racism as reflecting racist sentiments – but of a selected group rather than society at large. For instance, one woman explains:

I don’t feel that [racist online content] reflects Norwegian society at all. It might seem like that if you look at the media, but I don’t experience Norwegians as racists like that, like online. There’s always one or another, but […] I don’t feel that internet, social media or media in general reflect the Norwegian people.

In understanding online racism as exceptional, some respondents emphasise how the online infrastructure can magnify the rhetoric of a small group. As one woman explains:

I don’t feel that they are very, extremely, many [who post racist comments online]. But there are enough that you kind of see the comments sections fill up. And the ones who assert their views the most come on top because they spark a lot of debate. And then they come on top. So even if you have the ones who write positive things in that debate, they come further down.

Another understanding of online racism sees it as exceptional but as ‘trolling’ more than a reflection of racist intentions (bottom left corner of ). Trolling refers to posting comments in online conversations to provoke emotional reactions from others or manipulate others’ perceptions (Buckels, Trapnell, and Paulhus Citation2014). For instance, one young man holds that the perpetrators of online racism are only out to provoke: ‘Online there are like only trolls – people who try to provoke and tease you in all sorts of ways. I can’t take the internet seriously.’

Trolling is generally understood as insincere, not reflecting the authors’ beliefs and sentiments but simply a tool to provoke a certain reaction (Buckels, Trapnell, and Paulhus Citation2014). The respondent’s quote similarly implies that the racist comments online are primarily a means for people to provoke and tease. As such, they do not necessarily reflect true racist intentions and sentiments as much as the online ‘game’ of debate. However, there can be ambiguity here, as one of the young men indicates:

I don’t know if I can call what I see on TikTok racism because there are really many trolls there, very many trolls. Many say things just to provoke you. But like, if you just look at it on the surface, it is, per definition, racism.

The last understanding of online racism presents it as predominantly reflecting ignorance (upper left corner of ), which entails understanding online racism as ordinary but not necessarily intentional. For instance, there is a common perception that the agents of online racism are predominantly older people – in particular ‘older white men’ – who are seen to be ignorant, with poor digital competence and little exposure to diversity. One woman describes the typical agent of online racism as follows:

It is typically uninformed, low-educated people. Usually older people from another time and who don’t know any better. That’s my experience. […] It’s usually people who don’t have anything better to do and don’t know any better about the world, haven’t gotten educated.

I would say that it is pretty normal people [who post racist comments online]. I wouldn’t say that they sit at home all day and just: ‘hate, hate, hate’. But I would also say that many of those who write those things online do it because they don’t know any better.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, I study how young Muslims in Norway, as potential targets of online racism, make sense of the phenomenon. The analysis is thus concerned with everyday meaning-making processes. Building on the work of Essed (Citation1991), I develop an analytical framework to study lay understandings of racism, capturing how ordinary people understand the a) nature, b) experience and c) causes (‘theories’) of online racism. These dimensions do not exhaust the different components that make up cognitive representations of racism, but they can provide a fruitful starting point for analysing people’s understandings, knowledge and experiences of racism.

So, what is online racism in the eyes of its targets?

The young Muslims in this study experience online racism as massive and widespread to the extent that they perceive it as an unavoidable and almost normalised aspect of being online. They see the content they encounter online as unambiguously racist. Online racism is described as overt and explicit, and the young Muslims rarely distinguish between ethnic, phenotypic or religious vitriol. ‘Racism’ becomes a term that encompasses the totality of their experiences of othering and exclusion, be it based on their religious affiliation, non-white appearance or non-European decent and perceived culture (see Modood Citation1997). Their understandings of the nature and expressions of online racism stand in stark contrast to accounts of the covert, ambiguous and subtle nature of ‘new’ and ‘modern’ forms of everyday racism (e.g. Bonilla-Silva Citation2017; Lamont et al. Citation2016; Sue Citation2010). However, as the online sphere has become an integral part of our everyday lives, experiences of racism in the online sphere become a part of racialised groups’ experiences of contemporary everyday racism, understood as manifestations of racism that occur through systematic, recurrent and familiar practices in everyday situations (Essed Citation1991).

The experience of online racism is shaped by the realm in which it occurs. Online racism is primarily experienced indirectly by observing racist content and attacks on others. However, respondents still understand such indirect experiences as personal experiences of online racism and attacks on who they are. Although the young Muslims see online racism as more explicit and extreme than the racism they typically encounter in offline settings, they consider online racism – including direct online attacks – as less serious and easier to handle. The distance in online communication seems to create a sense of depersonalisation, where the respondents do not feel personally targeted and find it easier to distance themselves from the perpetrator. Furthermore, the respondents see online racism as possible to avoid. They can control their exposure and reactions to it by avoiding or ignoring unpleasant content and regulating how visible (and thereby exposed) they make themselves. At the same time, online racism is only avoidable if they limit or log off a central arena of their everyday lives.

The young Muslims provide strikingly similar understandings of the nature of online racism and of online racism as an experience. Although their experiences of becoming direct targets of online attacks differ widely, their understandings of online racism draw not only on their direct personal experiences, but also on their knowledge of the experiences of others (cf. Essed Citation1991). Thus, they share a perception of online racism as widespread and an unavoidable risk of online participation, regardless of their previous experiences.

However, when it comes to explanatory understandings of the causes of online racism, clear differences emerge. The respondents’ ‘theories’ of online racism vary along two dimensions related to the extent to which they understand online racism as, first, intentionally racist and, second, an exceptional or ordinary part of Norwegian society. The main distinction in the respondents’ views is between those who understand online racism as ordinary, intentional and revealing Norway as a racist society, on the one hand, and on the other hand, those who for different reasons maintain that racist content online gives a skewed impression of Norwegian society. The latter view encompasses an understanding that racism online is perpetuated by a marginal group of people or that it does not reflect ‘true’ racist intentions but ignorance or a wish to provoke (trolling). Although the young Muslims’ theories of online racism clearly build on their previous experiences and knowledge of society, I do not find any systematic relationship between personal experiences and explanatory understandings of online racism. It differs how the respondents interpret and give priority to experiences in the online and offline worlds, and the theories of online racism appear anchored in unique individual configurations of experiences, knowledge and available cultural repertoires. Although there is a common perception that what happens online is ‘less real’ than what happens offline (see Ortiz Citation2019), this study shows that some targets online racism in fact interpret the online sphere as reflecting the real face of society.

It is interesting to note that intentionality acts a key dimension in the young Muslims’ theories of racism. In contrast, the academic literature has largely moved away from emphasising intentionality, arguing that contemporary racism is often perpetrated by well-intentioned people and that racist intentions is not a necessary criterion for racism (Høy-Petersen Citation2021; Sue Citation2010). This contrast might reflect that intentionality becomes particularly salient when making sense of explicit and at times extreme forms of racism, calling for an answer to the question ‘why would anybody write something like that?’ However, empirical studies in the US context do not report an emphasis on the intentionality of online racism among targets (Eschmann Citation2019; Gin et al. Citation2017; Ortiz Citation2021). When intentionality appears a key dimension in this study, it might reflect the available cultural repertoires for making sense of racism in the Norwegian context, where understandings of structural racism and ‘racism without racists’ are less prominent and developed than in the US context (e.g. Haugsgjerd and Thorbjørnsrud Citation2021).

How young Muslims make sense of online racism shapes the impact such rhetoric has on them. Understanding the massive amount of racist content they encounter online as reflecting the true sentiments of Norwegians bears enormously different implications for the young Muslims’ sense of exclusion and belonging than construing such content as something different from and not reflective of society at large. In other words, understandings of online racism do something. They mediate experiences and the consequences of experiences and dictate not only how we interpret specific experiences but also how we act and react (Jovchelovitch Citation2007). The current study suggests that although the young Muslims experience online racism as overt and at times extreme, the fact that it occurs online reduces some of its impact on its targets as the nature of online communication creates a distance and sense of control. Still, the constant exposure to overt and explicit racism in the online sphere can have very real and concrete consequences for its targets, including for their emotional reactions, health, sense of belonging and public participation (e.g. Fladmoe and Nadim Citation2017; Ortiz Citation2019).

As this study demonstrates, to fully understand the nature of contemporary racism, we also need to incorporate knowledge about the racism that occurs online and its specificities. Being exposed to overt racist and Islamophobic content online appears to be an integrated aspect of young people’s online lives, to the extent that many experience it as normalised (see also Eschmann Citation2019; Ortiz Citation2021). Thus, the ‘old’ overt forms of racism appear to live on in parallel with more subtle and covert forms. Consequently, there is an urgent need for more knowledge on and scholarly attention to the impact of online racism as a form of contemporary racism.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the project Far right politics online and societal resilience (FREXO). I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, in addition to members of the research group Equality, Integration and Migration at the Institute for Social Research and fellow project members in FREXO for valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. In particular, I want to thank Kari Steen-Johnsen for her support and indispensable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alba, R. 2005. “Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-Generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (1): 20–49. doi:10.1080/0141987042000280003.

- Auxier, B., and M. Anderson. 2021. Social Media Use in 2021. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2021/04/PI_2021.04.07_Social-Media-Use_FINAL.pdf.

- Bliuc, A.-M., N. Faulkner, A. Jakubowicz, and C. McGarty. 2018. “Online Networks of Racial Hate: A Systematic Review of 10 years of Research on Cyber-Racism.” Computers in Human Behavior 87: 75–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.026.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2017. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bravo López, F. 2011. “Towards a Definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of the Early Twentieth Century.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (4): 556–573. doi:10.1080/01419870.2010.528440.

- Buckels, E. E., P. D. Trapnell, and D. L. Paulhus. 2014. “Trolls Just Want to Have fun.” Personality and Individual Differences 67: 97–102. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016.

- Coates, R. 2011. “Covert Racism in the USA and Globally.” Sociology Compass 2 (1): 208–231. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00057.x.

- Ellefsen, R., and S. Sandberg. 2022. “A Repertoire of Everyday Resistance: Young Muslims’ Responses to Anti-Muslim Hostility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (11): 2601–2619. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1894913.

- Eschmann, R. 2019. “Unmasking Racism: Students of Color and Expressions of Racism in Online Spaces.” Social Problems 67 (3): 418–436. doi:10.1093/socpro/spz026.

- Essed, P. 1991. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory (Vol. 2). Newbury Park, California: Sage.

- Fladmoe, A., and M. Nadim. 2017. “Silenced by Hate? Hate Speech as a Social Boundary to Free Speech.” In Boundary Struggles: Contestations of Free Speech in the Public Sphere, edited by A. H. Midtbøen, K. Steen-Johnsen, and K. Thorbjørnsrud, 45–75. Oslo: Cappelen.

- Fladmoe, A., M. Nadim, and S. R. Birkvad. 2019. Erfaringer med hatytringer og hets blant LHBT-personer, andre minoritetsgrupper og den øvrige befolkningen (Rapport 2019: 4). Retrieved from Oslo: https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2584665/Erfaringer%2bmed%2bhatytringer.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

- Foxman, A. H., and C. Wolf. 2013. Viral Hate: Containing its Spread on the Internet. New York: Macmillan.

- Garner, S., and S. Selod. 2015. “The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia.” Critical Sociology 41 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1177/0896920514531606.

- Gin, K. J., A. M. Martínez-Alemán, H. T. Rowan-Kenyon, and D. Hottell. 2017. “Racialized Aggressions and Social Media on Campus.” Journal of College Student Development 58 (2): 159–174. doi:10.1353/csd.2017.0013.

- Goldberg, D. T. 2009. The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Harris, R., D. Cormack, M. Tobias, L.-C. Yeh, N. Talamaivao, J. Minster, and R. Timutimu. 2012. “The Pervasive Effects of Racism: Experiences of Racial Discrimination in New Zealand Over Time and Associations with Multiple Health Domains.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (3): 408–415. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.004.

- Haugsgjerd, A. H., and K. Thorbjørnsrud. 2021. “Innspill til debatten om strukturell rasisme: potensial, utfordringer og kritikk.” Tidsskrift for samfunnsforskning 62 (1): 78–79. doi:10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2021-01-04.

- Høy-Petersen, N. 2021. “Civility and Rejection: The Contextuality of Cosmopolitan and Racist Behaviours.” Sociology 55 (6): 1191–1210. doi:10.1177/00380385211011570.

- Hutchens, M. J., V. J. Cicchirillo, and J. D. Hmielowski. 2015. “How Could you Think That?!?!: Understanding Intentions to Engage in Political Flaming.” New Media & Society 17 (8): 1201–1219. doi:10.1177/1461444814522947.

- Jovchelovitch, S. 2007. Knowledge in Context: Representations, Community and Culture. London: Routledge.

- Lamont, M., G. M. Silva, J. Welburn, J. Guetzkow, N. Mizrachi, H. Herzog, and E. Reis. 2016. Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Matamoros-Fernández, A., and J. Farkas. 2021. “Racism, Hate Speech, and Social Media: A Systematic Review and Critique.” Television & New Media 22 (2): 205–224. doi:10.1177/1527476420982230.

- Modood, T. 1997. “Introduction: The Politics of Multiculturalism in the new Europe.” In The Politics of Multiculturalism in the new Europe: Racism, Identity and Community, edited by T. Modood, P. Werbner, and R. Werbner, 1–26. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moor, P. J., A. Heuvelman, and R. Verleur. 2010. “Flaming on Youtube.” Computers in Human Behavior 26 (6): 1536–1546. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.023.

- Nadim, M., and A. Fladmoe. 2021. “Mobbing og hatytringer blant skoleungdom i Oslo: Betydningen av elevenes minoritetsbakgrunn og skolekonteksten.” Nordisk tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning 2 (2): 129–149. doi:10.18261/issn.2535-8162-2021-02-03ER.

- Ortiz, S. M. 2019. ““You Can Say I Got Desensitized to It”: How Men of Color Cope with Everyday Racism in Online Gaming.” Sociological Perspectives 62 (4): 572–588. doi:10.1177/0731121419837588.

- Ortiz, S. M. 2021. “Racists Without Racism? from Colourblind to Entitlement Racism Online.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (14): 2637–2657. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1825758.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2015. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Perry, B. 2001. In the Name of Hate: Understanding Hate Crimes. New York: Routledge.

- Picca, L. H., and J. R. Feagin. 2007. Two-faced Racism: Whites in the Backstage and Frontstage. New York: Routledge.

- Rehman, I., and T. Hanley. 2023. “Muslim Minorities’ Experiences of Islamophobia in the West: A Systematic Review.” Culture & Psychology 29 (1): 139–156. doi:10.1177/1354067(221103996.

- Salvatore, J., and J. N. Shelton. 2007. “Cognitive Costs of Exposure to Racial Prejudice.” Psychological Science 18 (9): 810–815. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01984.x.

- Sue, D. W. 2010. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sue, D. W., and L. B. Spanierman. 2020. Microaggressions in Everyday Life. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.