ABSTRACT

This article explores how level of education and region of origin (EU versus non-EU) shape newcomers’ perceptions of being welcome and treated fairly upon arrival, as well as their feelings of closeness and belonging to majority members and their long-term commitment to their new country of residence. Our results show that the impact of these factors – education and EU background – varies between these dimensions in shaping individuals’ attitudes and feelings about their new home. Feelings of being welcome and treated fairly do not differ much between origin groups per se, but they do differ between highly skilled and less-skilled migrants, although in a paradoxical way. Skilled third-country nationals are more skeptical than individuals with lower levels of education, and they are also more likely to feel marginalized. As regards the other dimensions, origin clearly trumps education. Although EU migrants are not particularly skeptical about Germany, they feel less close to it and more hesitant to make a long-term commitment to the country. Our analysis shows that skilled migrants do not relate in a consistent or homogeneous way to their destination country.

Introduction

In most immigration countries, there is little debate about the individuals focused on in the global ‘race for talent’ (Shachar Citation2006). They are perceived as bringing new ideas, skills, and cultures; helping to rejuvenate the population and labor force; and minimizing the societal challenges and costs related to large-scale immigration (Winter Citation2024; Faist Citation2013; Schönwälder Citation2013). These challenges include growing perceptions of economic and cultural threat, especially among the low-skilled native labor force. Without much resistance from natives, barriers to immigration have been substantially lowered for skilled migrants in recent decades (Schmidtke Citation2024), and their numbers have increased in many destination countries. Germany is a good example of this (Plöger and Becker Citation2015; Sprengholz et al. Citation2021).

The literature on the experiences of skilled migrants portrays them as a sought-after and highly flexible group showing little inclination for commitment or adaptation beyond earning money in their new host country. They are described as privileged and always on the move: ‘the perception is that highly educated and professionally successful people move across borders easily and possess the relevant competencies for cross-border communication and exchange’ (Faist Citation2013, 1643). Likewise, in terms of their identification and commitment, they are depicted as identifying at best with supranational entities – if not with the world itself – and being rather unconstrained by social and emotional ties to a certain place: ‘the bearers of skills, education, and abilities that seek to maximize earnings in the short term while retaining little commitment to any particular society or national labor market over the longer term’ (on newcomers in the US see Massey and Redstone Akresh Citation2006, 954). With respect to their acculturation in host societies, the literature suggests that skilled migrants can find economic success while skipping the strenuous process leading to upward mobility for less-skilled and underprivileged migrants, as described in more classic approaches to assimilation (Alba and Nee Citation1997). This image of highly skilled migrants is, however, often shaped by the rather privileged subgroup of expatriates and other skilled migrants who come for work. In the European context, it often relates to intra-EU migrants. As a consequence, level of education, country of origin, and migration motive are confounded in this literature (Weinar and von Koppenfels Citation2020).

But there is little systematic empirical evidence on whether skilled newcomers relate to their country of residence in any specific or typical way. Many studies focus on highly skilled migrants’ labor-market integration, particularly on the challenges related to recognizing their educational degrees and overqualification (Gauthier Citation2016; Kogan Citation2006; Citation2012; Reitz Citation2013; Schittenhelm and Schmidtke Citation2011, 143). Their attitudes and feelings about their new home have received less attention (Hajro et al. Citation2019, 329). Although the number of empirical studies that tackle this aspect of highly skilled migration is rising (Gerber and Ravazzini Citation2022; Geurts, Davids, and Spierings Citation2021; Koikkalainen Citation2013; Plöger and Becker Citation2015; Plöger and Kubiak Citation2019; Ryan, Klekowski von Koppenfels, and Mulholland Citation2015; Ullah et al. Citation2021), systematic comparisons between migrants with high and lower levels of education are still rare. Accordingly, it has been argued that ‘given the importance attached to immigrants’ education, it is surprising that its role in shaping immigrants’ attitudes towards host states is not more thoroughly researched’ (Careja and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017, 153). This partially reflects the fact that research on skilled migrants is often based on qualitative data with small samples (Weinar and von Koppenfels Citation2020, 104; Winter Citation2021), while quantitative studies often focus on the large share of low-skilled migrants. To be sure, many studies control for an individual’s level of education statistically when analyzing specific aspects of migrants’ integration process. But the question of whether highly skilled migrants systematically differ from their less-skilled co-ethnics in how they relate to their new country of residence remains largely unanswered. Research is particularly scarce when it comes to highly skilled migrants from a wider range of origin groups than those focused on in studies of expatriates or internationally mobile individuals (Weinar and von Koppenfels Citation2020, 105).

We want to add to this literature by exploring educational gaps in the way newcomers think and feel about their country of residence in a more encompassing way. The concept of ‘middle-class nation building’ as outlined in the introduction to this Special Issue implies ‘social closure and boundary drawing towards the outside’ and, among those within the national boundaries, mutual respect, equal treatment and participation, and long-term belonging and commitment (Winter Citation2024). This entails that the very group focused on in this project, namely skilled migrants, do not remain skeptical about feeling welcomed in the destination country, or about their opportunities for upward mobility, and do not remain distant towards its citizens. Likewise, it would have little to do with the more encompassing idea of ‘middle-class nation building’ through immigration if skilled migrants did not strive for permanent settlement and full belonging at some point, even though their temporary presence in the country would, of course, still be economically beneficial.

We start out by discussing the theoretical mechanisms that link high levels of education to a broad set of indicators, and briefly summarize the respective empirical findings. Based on this, we provide systematic – and so far, scarce – descriptive evidence with the help of new and innovative data collected among newcomers to Germany, one of the most important immigration destinations worldwide. The ENTRA dataset (shown below) offers unique insight into the question of how skilled newcomers relate to their host country, for three reasons. First, it covers an exceptionally broad set of indicators for different dimensions of newcomers’ relationship with their host country. These include attitudes about Germany (e.g. their perceptions of opportunities for upward mobility), feelings of belonging and closeness (e.g. to Germans or the inhabitants of their municipality), and newcomers’ long-term commitment to the country (e.g. their plans to stay for good and naturalize). Second, these indicators are captured among migrants with high and lower levels of education who belong to different origin groups: EU migrants (Italians and Poles), and third-country nationals (Syrians and Turks). This allows us to disentangle the roles of skill level and country of origin, as outlined above. In Germany, the experiences and challenges faced by skilled third-country nationals may more closely resemble those faced by unskilled migrants from the same origins than those faced by similarly skilled EU migrants. A third advantage is that information on the above-mentioned indicators was captured during migrants’ early years in Germany. Our data will thus reveal how these migrants differ by education level or region of origin per se, rather than by group-specific experiences in the host country. In many immigrant surveys, respondents have already been in the host country a long time before being surveyed, or were even born there. Our analyses do not yet meet the goal of a ‘coherent narrative on the integration pathways of the highly skilled’, as demanded by Weinar and van Koppenfels in their encompassing study of the highly skilled (Citation2020, 105). Nonetheless, we hope to lay the groundwork for future detailed analyses with a more explanatory focus.

How do highly skilled migrants relate to their country of residence? The role of education and national origin

In our study of newcomers’ relationship with their country of residence, we explore three different dimensions. In this section, we briefly present the indicators used in the empirical section of the paper, describe their relevance, spell out the theoretical links between skill level – or, alternatively, region of origin – and the different dimensions, and briefly review the available quantitative empirical evidence for the case of Germany.

Attitudes about feeling welcome and treated fairly

Attitudes about feeling welcome and treated fairly are important, as is having a fair chance for upward mobility, and not just because their absence may put an emotional strain on those who experience exclusion and unfair treatment (Small and Pager Citation2020). Newcomers who feel blocked off from the host society's social networks and status systems may also feel less motivated to leave the ethnic niches of housing and labor markets and to connect with majority members – which ultimately fosters ethnic equality (Small and Pager Citation2020, 62). These attitudes have mostly been studied under the umbrella of perceptions of discrimination and unfair treatment (Diehl, Liebau, and Muehlau Citation2021; Schaeffer Citation2019; Saint Pierre, Martinovic, and Vroome Citation2015, 1842; Steinmann Citation2019; ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013; Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2012; Verkuyten Citation2016).

According to survey data, natives strongly prefer skilled migrants over less-skilled (Bansak, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Citation2016; Helbling and Kriesi Citation2014; Naumann, Stötzer, and Pietrantuono Citation2018). In Europe and North America, European migrants are also preferred (Heath and Richards Citation2018, 24). These preferences generally reflect the lower perceptions of economic and cultural threat that come with lower social distances towards migrants with higher skill levels, and from countries perceived as culturally less distant. As a consequence, migrants from these groups should be more welcome and less exposed to unfair treatment than low-skilled migrants and migrants perceived as culturally more distinct. However, natives’ preference for skilled migrants does not necessarily translate into greater feelings of acceptance and fair treatment among educated migrants. This has been pointed out by proponents of the ‘integration paradox’: the phenomenon that although migrants with higher levels of education are more popular than their lower-skilled counterparts, they hold more skeptical views about their host country (ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013; Verkuyten Citation2016). From a social-psychological perspective, these perceptions mirror not only actual exposure to unequal treatment, but also more awareness of unequal treatment and higher aspirations for equal treatment (Diehl, Liebau, and Muehlau Citation2021; Verkuyten Citation2016). Educated migrants are more likely to compare themselves to natives than to other migrants or individuals in their origin countries, and thus to feel more deprived, and react more sensitively, if they are blocked from upward mobility. They are also more aware of an exclusionary societal discourse in the media, partly due to their better language skills (Saint Pierre, Martinovic, and Vroome Citation2015, 1842; Steinmann Citation2019).

In Germany, natives clearly prefer skilled over unskilled migrants (Czymara and Schmidt-Catran Citation2016). However, empirical evidence on how migrants themselves experience acceptance and exclusion after migration is more in line with the ‘integration paradox’ – that is, educated migrants perceive more rather than less discrimination than migrants with low levels of education do (Schaeffer Citation2019; Steinmann Citation2019; Tuppat and Gerhards Citation2021; but: Careja and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017). Some studies show that both skill level and origin matter, and that educated migrants only perceive more discrimination when they belong to origin groups that face salient ethnic boundaries (Diehl, Liebau, and Muehlau Citation2021). The findings on origin-group differences suggest that social distances and levels of xenophobia are substantially higher against migrants from the Global South, especially when those migrants come from Muslim countries (Wallrich, West, and Rutland Citation2020). According to survey data, refugees and Turks face substantially greater social distances by native Germans than Italians do, for example.Footnote1 Audit studies consistently reveal more discrimination against members of these groups, such as on the labor market (Koopmans, Veit, and Yemane Citation2019; Veit et al. Citation2022). This is in line with what is known about these groups’ perceptions of exclusion and disadvantage. Third-country nationals in Germany, particularly Turkish migrants, are more likely to report being disadvantaged than other individuals belonging to the former guest-worker population (Wittlif Citation2018). The perceptions of Polish migrants are somewhere in between. According to a comparative survey on Poles in four European countries, only about a third of Polish respondents living in Germany reported that they are rarely or never discriminated against (McGinnity and Gijsberts Citation2015).

| (b) | Feelings of closeness and belonging | ||||

With respect to migrants’ feelings of closeness and belonging, empirical research mostly analyzes whether they feel connected to or identify with members of their origin group or with majority members (De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014; Phinney and Ong Citation2007; Verkuyten Citation2016). It is important to note that low feelings of closeness and belonging to either group are not inherently problematic and do not necessarily lead to ‘marginalization’ (Berry Citation2003; Verkuyten Citation2016). Collective identities above and beyond nation states may become more important after migration, especially among skilled migrants (Geurts, Davids, and Spierings Citation2021; Kunst and Sam Citation2013). In the end, what is important is whether minority members suffer from feeling disconnected or marginalized. From the perspective of the receiving country, some authors have raised questions about the possible repercussions of low levels of attachment on a shared sense of solidarity among a country's inhabitants (Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2012, 88). However, the public debate in this regard focuses mostly on migrants belonging to groups whose loyalty and integration is questioned, which in Europe is mostly the case for Muslims (Faist Citation2013, 1642).

Educated migrants are often more proficient in the majority language because of their higher learning efficiency (Careja and Schmidt-Catran Citation2017, 151; Esser Citation2006; Citation2009; Hochman and Davidov Citation2014, 346; Kristen and Seuring Citation2021; Miller Citation2000; Walters, Phythian, and Anisef Citation2007). Good language skills, in turn, foster newcomers’ exposure to the values, norms, and practices of the receiving country and enable contacts with natives, nurturing feelings of closeness and belonging. Likewise, feeling close to the majority should be an easily accessible option when the symbolic boundaries between newcomers and natives are not perceived as particularly salient or exclusionary (Esser Citation2009, 360; Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2012, 93). According to this logic, educated migrants and those from a European background should show stronger feelings of belonging.

Other arguments point in the opposite direction. In the last section, we showed that educated migrants are more aware of unfair treatment and react more sensitively to it. According to the rejection-disidentification model (RDIM, Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind, and Spolheim Citation2009), this should negatively affect their identification with the majority and also their emotional attachments to natives. Furthermore, identity choices are a matter of both constraint and choice (Koikkalainen Citation2013; Waters Citation1990, 19). Establishing close emotional and social ties to the majority may be a way to ‘shift sides and escape a minority stigma’ (Wimmer Citation2008, 19), but this incentive may only exist for minority members who belong to unpopular groups. The very groups that could easily develop feelings of closeness and belonging may be little inclined to do so.

Empirical research on Germany has mostly studied migrants’ national identification with the host country. Based on data from the German socio-economic Panel, Careja and Schmidt-Catran ‘find no indication that higher educated immigrants ‘turn away’ from the host society’ (Citation2017, 163). With respect to ‘gross differences’ between origin groups, it is difficult to compare findings across studies. Ethnic Germans and Poles identify more strongly with Germany than do groups that originally came to Germany during the recruitment period in the 1950s to 1970s (on adolescents, see Schulz and Leszczensky Citation2016, 179). According to a study by Hochman and Davidov (Citation2014, 357), Turks have a slightly lower identification than other large origin groups do. A study on recent migrants suggests that overall levels do not differ greatly between Polish and Turkish newcomers, but their trajectories over time do vary, partly reflecting the Turks’ lower feelings of being welcome (Diehl, Fischer-Neumann, and Muhlau Citation2016).

| (c) | Long-term commitment | ||||

From the perspective of the receiving countries, skilled migrants’ alleged lack of long-term commitment to their new homeland, as indicated by their high remigration and low naturalization rates, among other factors (Massey and Akresh Citation2006), is more problematic than the absence of strong feelings of closeness and belonging. After all, the global ‘race for talent’ (Shachar Citation2006) is not limited to attracting skilled migrants; it is also about making them stay (Weinar and von Koppenfels Citation2020, 104). And again, a large and growing share of noncitizens with no intentions to settle down for good may harm democratic legitimization processes and social cohesion.

Incentives and opportunities to apply for citizenship or settle permanently are strongly shaped by the receiving country's legal and political context. Within Europe, these incentives differ less between migrants with high and low levels of education, and more between those from within the EU and from outside. After all, EU migrants enjoy their privileges whatever their level of education, such as the opportunity to acquire German citizenship without surrendering their previous citizenship (Favell Citation2022, 126). In turn, the naturalization process is only marginally less demanding for educated migrants in general (for example, the wait time can be shortened by a year for candidates with good language skills).Footnote2 But again, the incentives for EU citizens to apply for a German passport are very small, and naturalization rates are low (Thränhardt Citation2017). EU citizens already enjoy many rights connected to the German passport, such as the right to vote in local elections. EU citizens can also freely move back and forth between their home and the host country, so they have few incentives to settle in one place. Third-country nationals, on the other hand, face bureaucratic hurdles when they want to pursue a transnational lifestyle or to leave their country of residence for longer time periods, whatever their skill level. Due to these higher transaction costs, they may feel greater pressure to choose between permanent settlement and remigration.

Among migrants in Germany, empirical evidence is mixed on the link between education level and intentions to stay for good or to remigrate (Steiner and Velling Citation1994). Diehl and Liebau (Citation2015) and Schiele (Citation2021) find that education and return intentions are unrelated among Turks; a more recent study by Bettin, Cela, and Fokkema (Citation2018, 1026) suggests that these factors are even negatively related in this group. In a study limited to labor migrants in Germany, Ette et al. conclude that those migrants with tertiary education are less likely to intend to stay for good (Citation2016, 440). With respect to naturalization, recent evidence indicates that education is unrelated to naturalization intentions, and EU origin is negatively related (Hübner Citation2022, 53; Witte Citation2014).

| (d) | Summing up: education, origin and migrants’ relationship with their new home | ||||

As shown by this brief sketch of theoretical arguments and empirical findings, it is by no means clear whether educated migrants per se can be expected to stay distant and detached from the receiving society. From a sociopsychological perspective, highly skilled migrants should feel treated unfairly and not welcome more often than low-skilled individuals do because of their higher aspirations for equal treatment. But most of the other mechanisms spelled out above refer to national origins rather than skill levels. Feeling close to majority members may be easier for members of groups who face blurred ethnic boundaries. At the same time, migrants who belong to nonstigmatized origin groups have less incentive for feeling close. In addition, the transnational movements and activities of EU migrants face fewer bureaucratic hurdles and come with lower transaction costs, even for migrants without German passports. Permanent settlement and naturalization offer few additional advantages and privileges beyond those already enjoyed by EU migrants.

Our summary also reveals that most studies focus on a narrow set of indicators for the three dimensions of newcomers’ relationship with their new home: migrants’ perceptions of unfair treatment, their national identification, and their intentions to stay and to naturalize. We are able to focus on a broader set of indicators in our analyses, including migrants’ perceptions of being welcome and opportunities for upward mobility; their feelings of closeness, not only to Germans but also to the inhabitants of their municipality; and their feelings of marginalization, as possibly mirroring a low sense of belonging. With respect to their long-term commitment, we consider newcomers’ ambitions to become ‘truly German’ one day, along with their intentions to naturalize and settle for good.

Data and measurements

We use data from the ENTRA project (Recent Immigration Processes and Early Integration Trajectories in Germany), funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, see Seuring et al. Citation2023. for a detailed methodological report). The origin groups surveyed were migrants from Italy, Poland, Turkey, and Syria. These groups represent different immigrant streams that have come to Germany since 1945. Large-scale migration from Turkey and Italy started during the labor recruitment period in the 1950s to 1970s, and was followed by a period of family reunification and marriage migration. Today, Italians arrive mostly as EU migrants with higher skill levels. Likewise, many Turks arrive as international students or – though fewer in number – refugees, often academics, who want to leave their country or were forced to. Immigration from Poland, which gained momentum after 2000, is no longer dominated by seasonal workers; it now includes many medium-skilled or highly skilled individuals who come to work or study. In 2015, large numbers of Syrians fled the civil war in their country and sought refuge in Germany. Between 25 and 30 percent of them have tertiary education (Welker Citation2022). To study the role of skill levels versus origin, we compare individuals with high and low levels of education (see below), and individuals from within the EU (Poles and Italians) and from outside (Turks and Syrians). To be sure, the patterns we present here might look different if other origin groups were included in the broader groups of EU and non-EU migrants, such as Bulgarians and Bosnians.

The survey’s target population was individuals from these four origin groups who came to Germany between 2015 and 2019.Footnote3 They were first interviewed in summer/fall 2019, and again in winter/spring 2020/2021. Our analyses are based on data from wave 1 (except for the intention to naturalize, which was only captured in the second wave). The survey questionnaires were available in the migrants’ native languages and covered integration in different areas, including several questions on newcomers’ attitudes about Germany and their attachments to Germans. presents an overview of the indicators we use in our empirical analysis.

Table 1. Indicators of new migrants’ attitudes and feelings about the host country.

Our key independent variable is level of education. It is challenging to define who is and who is not in the category of highly skilled migrants (Weinar and van Koppenfels: 9; Lowell and Findlay Citation2001). We differentiate between highly skilled migrants/migrants with tertiary levels of education (we use these terms interchangeably) and migrants with medium to low skill levels/without tertiary education, according to ISCED 1997. To be sure, the relationship between education and skills is complex. The advantage of capturing it by tertiary education is that it can be clearly delineated by the data at hand, without having to deal with tricky issues of codification and recognition of skills acquired abroad (Gowayed Citation2022). The recent migrants included in our data completed their education abroad, so their skill level does not reflect the processes and experiences of integration and exclusion that, in turn, may shape the attitudes and feelings about the host country under consideration here.

In our analyses, we control for demographic characteristics (age, gender), marital status (single, married, other), children (no/yes), and previous trips to Germany (no/yes). The presence of children in the household can make a big difference in migrants’ ability to engage in transnational activities, and this may also affect their attitudes and feelings about the receiving country. To look into change over time, we make use of the fact that newcomers included in the dataset have been in Germany for different periods of time, ranging from five to fifty months. We are able to interact time spent in Germany with level of education, and we display how the indicators presented in differ between individuals who arrived more recently and those who arrived earlier, and between those with and without tertiary education among EU and non-EU migrants. We present the results from linear and logistic regression models, depending on the respective indicator. Assuming there are no systematic differences in the attitudes of migrants who had lived in Germany for a shorter or longer time when they were interviewed, these differences can be interpreted as changes in migrants’ attitudes and feelings about Germany over time. To ease interpretation, we present the main results graphically as predicted means or probabilities for each indicator over time and by educational level and origin group. All variables were recoded so that higher values mean stronger agreement and feelings, higher frequencies, and so on. We exclude missing values variable-wise. For an overview on the distribution of variables and full regression models, see the Appendix.

Findings

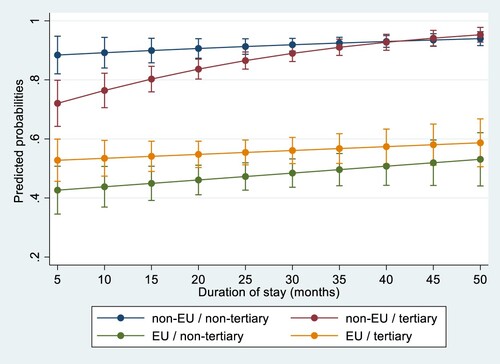

With respect to newcomers’ collective feelings of being welcome and treated fairly, reveals a somewhat mixed picture. Differences by origin or by level of education are negligible, nor is there a clear trend over time in these perceptions. But what is interesting against the backdrop of this Special Issue is that third-country nationals with low levels of education – the group that, for all we know, is least popular among natives – are least likely to say that members of their group are discriminated against (although confidence intervals overlap at most time points). This is in line with previous studies on the ‘integration paradox’ outlined above. Migrants from Turkey and Syria with low levels of education may have lower aspirations for equal treatment and – due to their limited proficiency in German – may also not be aware of more subtle forms of discrimination.

Figure 1. Predicted mean of agreement over time: How often do you think [country of origin people] are treated unfairly in Germany? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from never (1) to very often (5).

![Figure 1. Predicted mean of agreement over time: How often do you think [country of origin people] are treated unfairly in Germany? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from never (1) to very often (5).](/cms/asset/39f042ee-9116-4645-8be2-3470e3114590/cjms_a_2315356_f0001_oc.jpg)

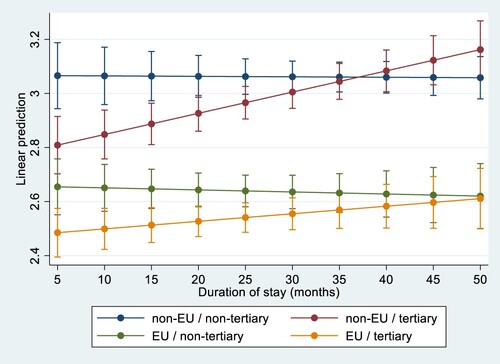

displays the share of individuals who agree that Germany is a welcoming country. After two to three years in the country, this share is again highest among the very groups that are actually least welcome in Germany, namely migrants from a Muslim-majority country with low levels of education. Interestingly, this share even increases over time, so it does not merely reflect a ‘honeymoon effect’ experienced by new arrivals who still use their origin country as a frame of reference during their stay (Röder and Mühlau Citation2012). Among third-country nationals, we clearly see a greater level of skepticism from individuals with tertiary levels of education. Upon arrival, they feel least welcome of all groups, and although their attitude becomes more positive over time, they remain significantly more skeptical than third-country nationals with lower levels of education. These differences in education are much less pronounced among EU migrants.

Figure 2. Predicted mean of agreement over time: In general, Germany is a welcoming country for [country of origin people]. Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

![Figure 2. Predicted mean of agreement over time: In general, Germany is a welcoming country for [country of origin people]. Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).](/cms/asset/a73876d9-e754-49f0-bb9b-932478cf7db9/cjms_a_2315356_f0002_oc.jpg)

We see a similar picture with respect to migrants’ assessment of the possibilities for upward mobility in Germany, as displayed in . Unlike Europeans, third-country nationals, who face a considerable labor-market disadvantage in Germany, increasingly agree with the statement that individuals from their origin group can get ahead in Germany if they work hard. Highly skilled third-country nationals are quite skeptical in the beginning, but the share of those who agree with the optimistic statement increases over time (though it remains lower than among less-skilled third-country nationals at all time points). Again, we see a stagnation over time and no systematic differences by level of education among EU migrants.

Figure 3. Predicted mean of agreement over time: In general, [country of origin people] can get ahead in Germany if they work hard. Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

![Figure 3. Predicted mean of agreement over time: In general, [country of origin people] can get ahead in Germany if they work hard. Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).](/cms/asset/5a9cbb83-acdb-4ada-ae92-6fbb103d36c6/cjms_a_2315356_f0003_oc.jpg)

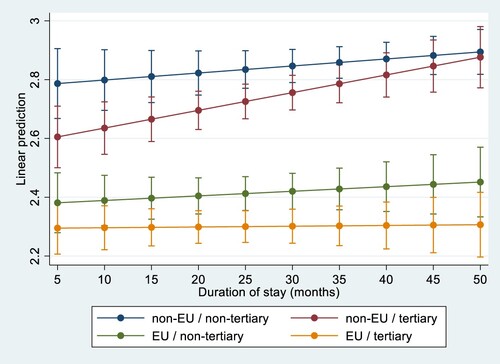

When we turn to the next dimension, migrants’ feelings of closeness and belonging, a similar picture emerges. Upon arrival, the group that is remarkably optimistic in terms of their perceptions of being welcome and treated fairly in Germany – third-country nationals with low levels of education – tends to report the highest feelings of closeness towards the inhabitants of the city in which they live () and towards Germans (), followed rather closely by highly educated third-country nationals. EU migrants, in turn, feel less close not only to Germans in general, but also to the inhabitants of the city in which they live. The cleavage clearly runs between the EU versus non-EU origin groups rather than between the highly educated and the less-educated, although educated migrants in both groups report slightly lower feelings of closeness. Note that the scales differ between and , and that feelings of closeness at the city level are overall higher than they are towards Germany in general.

Figure 4. Predicted mean over time: How close do you feel to the inhabitants of the city where you live? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from not close at all (1) to very close (4).

Figure 5. Predicted mean over time: How close do you feel to Germans? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from not close at all (1) to very close (4).

shows that agreement to the statement that comes closest to feelings of marginalization (How often do you feel like an outsider in Germany?) is high among very recently arrived migrants with high levels of education, but later declines. After three years in the country, no differences by origin group or level of education can be found. However, this finding confirms the argument by Ryan, Klekowski von Koppenfels, and Mulholland (Citation2015) that challenges related to belonging and exclusion also exist for educated migrants, especially those who belong to non-European and rather low-skilled groups. Results clearly indicate that for EU migrants, low feelings of closeness and belonging (see and ) are not mirrored by stronger feelings of marginalization.

Figure 6. Predicted means of frequency over time: How often do you feel like an outsider in Germany? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from never (1) to very often (5).

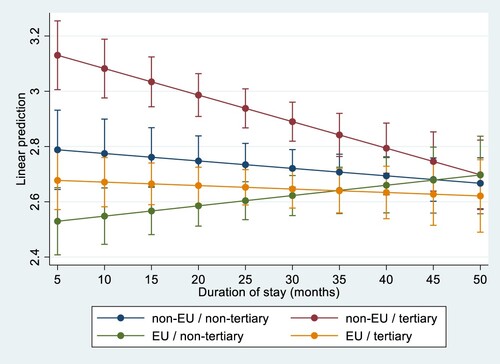

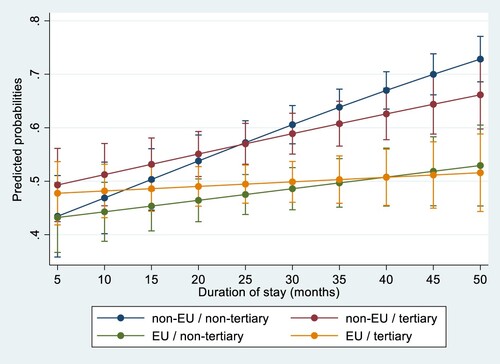

Turning to the final dimension, newcomers’ commitment to Germany, the picture is quite straightforward. Intentions to stay significantly increase over time only among third-country nationals. This increase is, however, somewhat less pronounced among skilled third-country nationals than among those with low levels of education. Apart from this, differences by level of education are rather marginal, whereas differences by origin become quite pronounced over time. After about two years in Germany, third-country nationals are more resolved to stay in Germany than Europeans are ().

Figure 7. Predicted probabilities over time: I expect to stay in Germany. Note: Predicted probabilities based on logistic regression model on intention to stay in Germany (yes = 1).

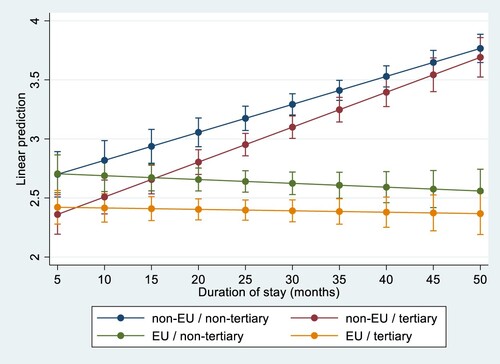

To be sure, staying for good does not imply fully belonging. We captured this additional aspect based on whether respondents think they can become truly German one day () and how important this is for them (). Third-country nationals, particularly those with low levels of education, are the most optimistic that they can become truly German. This difference between third-country nationals and Europeans becomes much more pronounced over time.

Figure 8. Predicted means of agreement over time: Do you think you can become truly German one day? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Figure 9. Predicted means of importance over time: How important is it to you to become truly German? Note: Predicted means based on linear regression model. Answers range from not important at all (1) to very important (4).

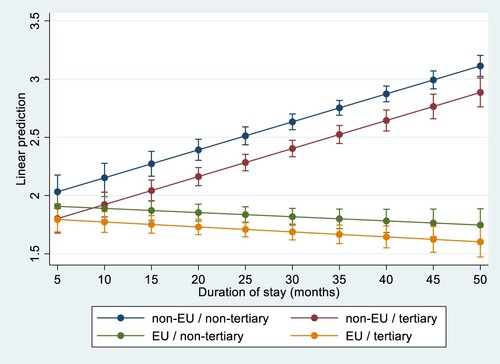

shows that becoming German is also more important for third-country nationals than it is for EU migrants. Differences by education are again small, but highly educated third-country nationals tend to find it less important to become ‘truly German’ than less-educated individuals from the same origin group do. Again, the differences and trends between Europeans and third-country nationals are much larger than those between migrants with high and low levels of education.

The previous questions refer to ‘belonging’ in an encompassing and far-reaching way (‘becoming truly German’). Respondents were also asked about their intention to formally naturalize, something that may reflect pragmatic rather than emotional reasons. As shown in , this question revealed a less dynamic pattern over time. Instead, the group differences seen in the previous figures are already quite pronounced upon arrival. Educated third-country nationals are one exception here: initially, they are more hesitant than low-educated third-country nationals to apply for a German passport, but they catch up with their less-educated counterparts after about two years.

Summary and discussion

We draw several conclusions from our encompassing analysis of recent migrants’ attitudes and feelings about their host country. The patterns seen in our results differ between dimensions, particularly between the first dimension, perceptions of being welcome and treated fairly, and the second and third dimensions, which capture newcomers’ feelings of closeness and belonging and their long-term commitment to Germany. Overall, we found very limited empirical evidence that skilled migrants prefer to stay ‘happily apart’ and keep their distance from their new home.

Instead, our findings suggest three things. The first is that the level of education matters most with respect to newcomers’ perceptions of being welcome and treated fairly. EU migrants and third-country nationals do not differ systematically on this dimension. Differences by education are more pronounced, but limited to third-country nationals. In this group, skilled individuals not only perceive more unfair treatment against members of their origin group than do those with low levels of education, but they are also less convinced that Germany is a welcoming country and that they can get ahead if they work hard. This finding is in line with recent work on the integration paradox, which suggests that aspirations for equal treatment and sensitivity towards unequal treatment – which are particularly pronounced among skilled migrants – play an important role in shaping these perceptions. Highly skilled and low-skilled migrants also differ with respect to another indicator, feelings of marginalization. Such feelings are initially more pronounced among highly educated third-country nationals, but they become weaker over time. This likely reflects the fact that the friendship ties of highly skilled individuals are often interethnic, frequently between immigrants and natives (Schlueter Citation2012). Establishing these ties may take more time for third-country nationals, who face larger social distances from natives. Highly educated third-country nationals also find it less important to become truly German one day. Taken together, these are the only pieces of evidence we found for skilled migrants’ allegedly higher propensity to keep their new home at a distance.

Our second finding is that, with respect to most dimensions of newcomers’ relationship with Germany, it is clearly the migrants’ origin that makes a difference, rather than their level of education. In short, EU migrants are not particularly skeptical about Germany (as we see in terms of their perceptions of unequal treatment), but they feel less close to its inhabitants – on both the national and the local level – and are also much more hesitant to make a long-term commitment to the country. Turks and Syrians, in turn, not only feel closer to Germans than EU migrants do, and even closer to the inhabitants of the city where they live. They are also more convinced that one day they will be ‘truly German’, and they find this more important. Likewise, they plan to stay for good and apply for German passports more often than Poles and Italians do.

The third important finding is that the educational differences we do see – mostly among third-country nationals – decrease over time, for example with respect to their perceptions of being welcome or being treated unfairly. This happens mostly because the highly skilled newcomers, who initially may be more skeptical, catch up with the more enthusiastic less-educated ones. But there is little indication that origin differences between EU migrants and third-country nationals become less pronounced over time. In fact, for the second and third dimensions in particular, the integration trajectories of EU and non-EU migrants diverge rather than converge over time for most indicators (feeling close, becoming truly German), because third-country nationals grow emotionally closer and more connected to Germany. In general, EU migrants do not show any significant change over time with respect to the indicators under consideration here. Although we can only compare migrants by duration of stay within the first few years after arrival, our overall findings suggest that a pattern of ‘integration’ over time is visible only among third-country nationals, not among EU migrants. Only Turks and Syrians (but not Italians or Poles) become more optimistic about their opportunities in Germany, and are more likely to decide to stay for good and become ‘truly German’ the longer they are in the country; this is largely independent of their education level. One limitation of our analyses is that we were only able to compare EU and non-EU migrants by studying four origin groups. We do not know what results we would find by comparing other origin groups. Except for the Syrians, the groups we studied have a long history of migration to Germany. This shapes the way those groups are perceived and treated by native Germans – and this, in turn, may affect their attitudes and feelings about the reception country.

Against the backdrop of this Special Issue, and with respect to newcomers’ attitudes and feelings about Germany, our results lend support to findings and arguments from other studies. Bilodeau and Gagnon show that, for the Canadian case, being a member of the middle class (indicated in a factorial survey conducted by the authors as ‘a computer technician’) ‘does not attenuate origin-based prejudices’. Nowicka emphasizes that ‘it is unproductive to consider higher education as a proxy for immigrants’ middle-class status, without understanding the context of origin of immigrants’. We were able to show that skilled newcomers per se do not relate to Germany attitudinally and emotionally in any cohesive way, but that EU versus non-EU origin is a crucial aspect of this ‘context’. Education matters, if it matters at all, in a ‘paradoxical’ way, only for how skeptical and marginalized newcomers from outside the EU feel about their new home. As regards the global race for talent (Shachar Citation2006), it is bad news that initially, the very individuals targeted by the ‘middle-class nation building project’ (Winter Citation2024) are the least likely to feel welcome and treated fairly in Germany. Although the attitudes of those we surveyed improve over time, others may have left Germany soon after their arrival because of their negative experiences and attitudes. Note that a survey like ours does not include individuals who leave soon after arrival, before they could be sampled and contacted by researchers like us. In any case, given that skilled migrants have high aspirations for equal treatment, making those individuals feel welcome and treated fairly upon arrival may require more effort than simply not ‘throwing sticks’ at them, as Joppke aptly puts it his contribution to this Special Issue.

The other dimensions we studied, feelings of closeness and belonging and long-term commitment, capture not so much cognitive aspects of newcomers’ relationship with their new home, but rather more emotional and pragmatic aspects. EU migrants’ low levels of attachment and belonging are fully compatible with a ‘neoliberal’ version of nation building through immigration that happens mostly on the labor market and does not require any ‘thick feelings’ of belonging (Joppke Citation2024). With respect to third-country nationals from predominantly Muslim countries, the good news from a policy perspective is that the very groups focused on in the societal debate among newcomers’ allegedly failing integration (Faist Citation2013, 1642) are the ones who are most determined to become ‘truly German’ one day, whatever this may mean.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant number DI 860/8-1). Claudia Diehl completed this article while she was a fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Measured on a 7-point scale from -3 to +3, 37% of German respondents (German citizenship, native-born with native-born grandparents) answered that a Turkish neighbor would make them feel uncomfortable (-3, -2, -1). This figure was 48% for refugees (own calculations based on ALLBUS data from 2016).

3 Individuals were randomly sampled from the local population registers. For practical purposes, the survey was limited to larger cities that were important destinations for these groups, according to official migration data. Migrants were approached by mail and could choose (by sending back a postcard) whether they wanted to complete the interview online, in person, or by phone.

References

- Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 1997. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839703100403.

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner. 2016. “How Economic, Humanitarian, and Religious Concerns Shape European Attitudes Toward Asylum Seekers.” Science 354 (6309): 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2147.

- Berry, John W. 2003. “Conceptual Approaches to Acculturation.” In In Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research, edited by Kevin M Chun, Pamela Balls Organista, and Gerardo Marín, 17–37. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Bettin, Giulia, Eralba Cela, and Tineke Fokkema. 2018. “Return Intentions Over the Life Course: Evidence on the Effects of Life Events from a Longitudinal Sample of First- and Second-Generation Turkish Migrants in Germany.” Demographic Research 39 (38): 1009–1038. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2018.39.38.

- Careja, Romana, and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. 2017. “Feeling German: The Impact of Education on Immigrants’ National Identification.” In In Lebensbedingungen in Deutschland in der Längsschnittperspektive, edited by Marco Giesselmann, Katrin Golsch, Henning Lohmann, and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran, 149–166. Würzburg: Springer VS.

- Czymara, Christian S., and Alexander W. Schmidt-Catran. 2016. “Wer ist in Deutschland willkommen? Eine Vignettenanalyse zur Akzeptanz von Einwanderern.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 68 (2): 193–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-016-0361-x.

- De Vroome, Thomas, Borja Martinovic, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2014. “The Integration Paradox: Level of Education and Immigrants’ Attitudes Towards Natives and the Host Society.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20 (2): 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034946.

- Diehl, Claudia, Marion Fischer-Neumann, and Peter Muhlau. 2016. “Between Ethnic Options and Ethnic Boundaries – Recent Polish and Turkish Migrants' Identification with Germany.” Ethnicities 16 (2): 236–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796815616156.

- Diehl, Claudia, and Elisabeth Liebau. 2015. “Turning Back to Turkey—or Turning the Back on Germany? Remigration Intentions and Behavior of Turkish Immigrants in Germany Between 1984 and 2011.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 44 (1): 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2015-0104.

- Diehl, Claudia, Elisabeth Liebau, and Peter Muehlau. 2021. “How Often Have You Felt Disadvantaged? Explaining Perceived Discrimination.” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 73 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-021-00738-y.

- Esser, Hartmut. 2006. Sprache und Integration. Die Sozialen Bedingungen und Folgen des Spracherwerbs von Migranten. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

- Esser, Hartmut. 2009. “Pluralisierung Oder Assimilation? / Pluralization or Assimilation?” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 38 (5): 358–378. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2009-0502.

- Ette, Andreas, Barbara Heß, and Lenore Sauer Tackling. 2016. “Germany’s Demographic Skills Shortage: Permanent Settlement Intentions of the Recent Wave of Labour Migrants from Non-European Countries.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 17 (2): 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0424-2.

- Faist, Thomas. 2013. “The Mobility Turn: A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (11): 1637–1646. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.812229.

- Favell, Adrian. 2022. The Integration Nation: Immigration and Colonial Power in Liberal Democracies. Cambridge: Polity.

- Gauthier, Carol-Anne. 2016. “Obstacles to Socioeconomic Integration of Highly-Skilled Immigrant Women: Lessons from Quebec Interculturalism and Implications for Diversity Management.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 35 (1): 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-03-2014-0022.

- Gerber, Roxane, and Laura Ravazzini. 2022. “Life Satisfaction Among Skilled Transnational Families Before and During the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Population Space Place 28 (6): 1–32.

- Geurts, Nella, Tine Davids, and Niels Spierings. 2021. “The Lived Experience of an Integration Paradox: Why High-Skilled Migrants from Turkey Experience Little National Belonging in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1): 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1770062.

- Gowayed, Heba. 2022. Refuge: How the State Shapes Human Potential. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hajro, Aida, Günter K. Stahl, Callen C. Clegg, and Mila B. Lazarova. 2019. “Acculturation, Coping, and Integration Success of International Skilled Migrants: An Integrative Review and Multilevel Framework.” Human Resource Management Journal 29 (3): 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12233.

- Heath, Anthony, and Lindsay Richards. 2018. “How do Europeans Differ in Their Attitudes to Immigration? Findings from the European Social Survey 2002/03–2016/17.” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 222.

- Helbling, Marc, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2014. “Why Citizens Prefer High- Over Low-Skilled Immigrants: Labor Market Competition, Welfare State, and Deservingness.” European Sociological Review 30 (5): 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu061.

- Hochman, Oshrat, and Eldad Davidov. 2014. “Relations Between Second-Language Proficiency and National Identification: The Case of Immigrants in Germany.” European Sociological Review 30 (3): 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu043.

- Hübner, Wiebke. 2022. “The Interplay of Immigrant Integration and Naturalization.” PhD diss., University of Cologne.

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, Inga, Karmela Liebkind, and Erling Spolheim. 2009. “To Identify or Not to Identify? National Disidentification as an Alternative Reaction to Perceived Ethnic Discrimination.” Applied Psychology 58 (1): 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00384.x.

- Joppke, Christian. 2024. “Neoliberal Nationalism and Immigration Policy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (7): 1657–1676. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2315349.

- Kogan, Irena. 2006. “Labor Markets and Economic Incorporation Among Recent Immigrants in Europe.” Social Forces 85 (2): 697–721. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0014.

- Kogan, Irena. 2012. “Potenziale nutzen! Determinanten und Konsequenzen der Anerkennung von Bildungsabschlüssen bei Zuwanderern aus der ehemaligen Sowjetunion in Deutschland.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 64 (1): 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-012-0157-6.

- Koikkalainen, Saara. 2013. “Transnational Highly Skilled Finnish Migrants in Europe: Choosing One's Identity.” National Identities 15 (1): 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2012.733156.

- Koopmans, Ruud, Susanne Veit, and Ruta Yemane. 2019. “Taste or Statistics? A Correspondence Study of Ethnic, Racial and Religious Labour Market Discrimination in Germany.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (16): 233–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1654114.

- Kristen, Cornelia, and Julian Seuring. 2021. “Destination-Language Acquisition of Recently Arrived Immigrants: Do Refugees Differ from Other Immigrants?” Journal for Educational Research Online 2021 (1): 128–156. https://doi.org/10.31244/jero.2021.01.05.

- Kunst, Jonas R., and David L. Sam. 2013. “Expanding the Margins of Identity: A Critique of Marginalization in a Globalized World.” International Perspectives in Psychology 2 (4): 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000008.

- Lowell, B. Lindsay, and Allan Findlay. 2001. “Migration of Highly Skilled Persons from Developing Countries: Impact and Policy Responses.” In International Migration Papers, 44. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Martinovic, Borja, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2012. “Host National and Religious Identification Among Turkish Muslims in Western Europe: The Role of Ingroup Norms, Perceived Discrimination and Value Incompatibility.” European Journal of Social Psychology 42 (7): 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1900.

- Massey, Douglas S., and Ilana Redstone Akresh. 2006. “Immigrant Intentions and Mobility in a Global Economy: The Attitudes and Behavior of Recently Arrived U.S. Immigrants*.” Social Science Quarterly 87 (5): 954–971. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00410.x.

- McGinnity, Frances, and Merove Gijsberts. “Perceived Group Discrimination among Polish Migrants to Western Europe: Comparing Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and Ireland.” ESRI Working Paper No. 502, The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Dublin.

- Miller, Jennifer M. 2000. “Language Use, Identity, and Social Interaction: Migrant Students in Australia.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 33 (1): 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3301_3.

- Naumann, Elias, Lukas Stötzer, and Giuseppe Pietrantuono. 2018. “Attitudes towards Highly Skilled and Low-Skilled Immigration in Europe: A Survey Experiment in 15 European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 1009–1030. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12264.

- Phinney, Jean S., and Anthony D. Ong. 2007. “Conceptualization and Measurement of Ethnic Identity: Current Status and Future Directions.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 54 (3): 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271.

- Plöger, Jörg, and Anna Becker. 2015. “Social Networks and Local Incorporation: Grounding High-skilled Migrants in Two German Cities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (10): 1517–1535. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1015407.

- Plöger, Jörg, and Susanne Kubiak. 2019. “Becoming ‘the Internationals’—how Place Shapes the Sense of Belonging and Group Formation of High-Skilled Migrants.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 20 (1): 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0608-7.

- Reitz, Jeffrey G. 2013. “Closing the Gaps Between Skilled Immigration and Canadian Labor Markets: Emerging Policy Issues and Priorities.” In In Wanted and Welcome? Policies for Highly Skilled Immigrants in Comparative Perspective, edited by Triadafilos Triadafilopoulos, 147–163. New York: Springer.

- Röder, Antje, and Peter Mühlau. 2012. “What Determines the Trust of Immigrants in Criminal Justice Institutions in Europe?” European Journal of Criminology 9 (4): 370–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370812447265.

- Ryan, Louise, Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels, and Jon Mulholland. 2015. “The Distance Between Us: A Comparative Examination of the Technical, Spatial and Temporal Dimensions of the Transnational Social Relationships of Highly Skilled Migrants.” Global Networks 15 (2): 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12054.

- Saint Pierre, di Francesca, Borja Martinovic, and Thomas De Vroome. 2015. “Return Wishes of Refugees in the Netherlands: The Role of Integration, Host National Identification and Perceived Discrimination.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (11): 1836–1857. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1023184.

- Schaeffer, Merlin. 2019. “Social Mobility and Perceived Discrimination: Adding an Intergenerational Perspective.” European Sociological Review 35 (1): 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy042.

- Schiele, Maximilian. 2021. “Life Satisfaction and Return Migration: Analysing the Role of Life Satisfaction for Migrant Return Intentions in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1): 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1763786.

- Schittenhelm, Karin, and Oliver Schmidtke. 2011. “Integrating Highly Skilled Migrants Into the Economy: Transatlantic Perspectives.” International Journal 66 (1): 127–143.

- Schlueter, Elmar. 2012. “The Inter-Ethnic Friendships of Immigrants with Host-Society Members: Revisiting the Role of Ethnic Residential Segregation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (1): 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.640017.

- Schmidtke, Oliver. 2024. “Migration as a Building Bloc of Middle-Class Nation-building? The Growing Rift Between Germany’s Centre-right and Right-wing Parties.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (7): 1677–1695. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2315350.

- Schönwälder, Karen. 2013. “Germany: Reluctant Steps Towards a System of Selective Immigration.” In In Wanted and Welcome? Policies for Highly Skilled Immigrants in Comparative Perspective, edited by Triadafilos Triadafilopoulos, 273–287. New York: Springer.

- Schulz, Benjamin, and Lars Leszczensky. 2016. “Native Friends and Host Country Identification among Adolescent Immigrants in Germany: The Role of Ethnic Boundaries.” International Migration Review 50 (1): 163–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12163.

- Seuring, Julian, Daniel Degen, Julia Rüdel, Felix Ries, Claudia Diehl, Cornelia Kristen, and Matthias Koenig. 2023. The ENTRA survey: Recent Immigration Processes and Early Integration Trajectories in Germany - Methodological Report. https://nbnresolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-85327-7.

- Shachar, Ayelet. 2006. “The Race for Talent: Highly Skilled Migrants and Competitive Immigration Regimes.” New York University Law Review 81: 101–158.

- Small, Mario L., and Devah Pager. 2020. “Sociological Perspectives on Racial Discrimination.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (2): 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.2.49.

- Sprengholz, Maximilian, Claudia Diehl, Johannes Giesecke, and Michaela Kreyenfeld. 2021. “From "Guest Workers" to EU Migrants: A Gendered View on the Labour Market Integration of Different Arrival Cohorts in Germany.” Journal of Family Research 33 (2): 252–283. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-492.

- Steiner, Viktor, and Johannes Velling. 1994. “Re-Migration Behaviour and Expected Duration of Stay of Guest Workers in Germany.” In In The Economic Consequences of Immigration to Germany, edited by Gunter Steinmann and Ralf E. Ulrich, 101–119. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag.

- Steinmann, Jan-Philip. 2019. “The Paradox of Integration: Why Do Higher Educated New Immigrants Perceive More Discrimination in Germany?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (9): 1377–1400. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1480359.

- ten Teije, Irene, Marcel Coenders, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2013. “The Paradox of Integration: Immigrants and Their Attitude Toward the Native Population.” Social Psychology 44 (4): 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000113.

- Thränhardt, Dietrich. 2017. “Einbürgerungen im Einwanderungsland Deutschland: Analysen und Empfehlungen.“ European Commission, August 21. Accessed 19 October 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/einbuergerung-im-einwanderungsland-deutschland-analysen-und-empfehlungen_de.

- Tolsma, Jochem, Marcel Lubbers, and Mérove Gijsberts. 2012. “Education and Cultural Integration among Ethnic Minorities and Natives in the Netherlands: A Test of the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.667994.

- Tuppat, Julia, and Jürgen Gerhards. 2021. “Immigrants’ First Names and Perceived Discrimination: A Contribution to Understanding the Integration Paradox.” European Sociological Review 37 (1): 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa041.

- Ullah, AKM Ahsan, Noor Hasharina Hasan, Siti Mazidah Mohamad, and Diotima Chattoraj. 2021. “Privileged Migrants and Their Sense of Belonging: Insider or Outsider?” Asian Journal of Social Science 49 (3): 161–169.

- Veit, Susanne, Hannah Arnu1, Valentina Di Stasio, Ruta Yemane, and Marcel Coenders. 2022. “The ‘Big Two’ in Hiring Discrimination: Evidence from a Cross-National Field Experiment.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 48 (2): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220982900.

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2016. “The Integration Paradox: Empirical Evidence from the Netherlands.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (5-6): 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764216632838.

- Wallrich, Lukas, Keon West, and Adam Rutland. 2020. “Painting All Foreigners with One Brush? How the Salience of Muslims and Refugees Shapes Judgements.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 8 (1): 246–265. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v8i1.1283.

- Walters, David, Kelli Phythian, and Paul Anisef. 2007. “The Acculturation of Canadian Immigrants: Determinants of Ethnic Identification with the Host Society.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 44 (1): 37–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2007.tb01147.x.

- Waters, Mary C. 1990. Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Weinar, Agnieszka, and Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels. 2020. Highly-Skilled Migration: Between Settlement and Mobility. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Welker, Jörg. 2022. “Relative Education of Recent Refugees in Germany and the Middle East: Is Selectivity Reflected in Migration and Destination Decisions?” International Migration 60 (2): 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12853.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2008. “The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 113 (4): 970–1022. https://doi.org/10.1086/522803.

- Winter, Elke. 2021. “Multicultural Citizenship for the Highly Skilled? Naturalization, Human Capital, and the Boundaries of Belonging in Canada’s Middle-Class Nation-Building.” Ethnicities 21 (2): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796820965784.

- Winter, Elke. 2024. “Middle Class Nation Building Through Immigration?.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50 (7): 1627–1656. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2024.2315348.

- Witte, Nils. 2014. “Legal and Symbolic Membership: Symbolic Boundaries and Naturalization Intentions of Turkish Residents in Germany.” In EUI/RSCAS Working Paper 2014/100, 1–39. Florence: European University Institute.

- Wittlif, Alex. 2018. “Wo Kommen Sie Eigentlich Ursprünglich her?” Diskriminierungserfahrungen und Phänotypische Differenz in Deutschland. Berlin: Forschungsbereich Beim Sachverständigenrat Deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR-Forschungsbereich).

Appendix

Highly skilled and highly skeptical? How education and origin shape newcomers' relationship with their new home

Table A1. Descriptive statistics of main variables.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics of control variables.

Table A3. Linear regression models – Perceptions of being welcome and treated fairly.

Table A4. Linear regression models – emotional attachments.

Table A5. Linear and logistic regression models – long-term commitment.