?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We examine how governance actors in first-asylum countries affect refugees' relocation preferences. We argue that external humanitarian actors and host country actors can have different effects on refugees' aspiration and perceived ability to relocate away from the first-asylum country. Using an original survey of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, we find that when refugees believe external actors are effective at dealing with refugee issues, they are significantly less likely to aspire to migrate but significantly more likely to feel able to do so. When refugees believe the host government is effective at providing security, they are significantly more likely to aspire to relocate but significantly less likely to feel able to do so. In other words, the effectiveness of host actors is associated with ‘involuntary immobility’. To probe this finding further, we rely on a modified conjoint experiment. In line with our observational findings, we find that refugees who believe host actors are effective are more likely to choose relocation over staying when presented with a legal opportunity, indicating involuntary immobility. Refugees who believe external actors are effective are no more likely than others to choose relocation when presented with a legal resettlement opportunity.

Wealthy states in the Global North and refugee-receiving countries in the Global South have struck a ‘grand compromise’. Instead of accepting or resettling refugees, wealthy nations mostly send aid to the countries where refugees are being received and hosted (Cuéllar Citation2005). As a result, more than three-quarters of the world's more than 100 million refugees live in economically-impacted first-asylum countries (UNHCR Citation2024), with average durations of displacement between 10 and 26 years (Ferris Citation2018). Under the grand compromise, first-asylum countries refrain from refoulement and provide basic security to refugees. Wealthy nations, on the other hand, finance humanitarian efforts through the United Nations.

A practical consequence of this international arrangement is that the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and associated agencies function like an impoverished ‘surrogate state’ in charge of providing refugees with food, healthcare, education and status determination (Abdelaaty Citation2021; Cuéllar Citation2005; Janmyr Citation2017; Kagan Citation2012; Miller Citation2017; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009)Footnote1. In first-asylum countries across Africa and the Middle East, refugees live below the poverty line with severe restrictions on their agency – or their ability to make choices regarding their and their family's wellbeing (e.g. UNHCR Citation2018b; UNICEF Citation2017). This lack of agency in the first-asylum country, paired with a dearth of legal resettlement opportunities, leads some refugees to resort to ‘negative coping mechanisms’ such as ‘desperate onward movement by sea’ (UNHCR Citation2020). For most, however, this lack of agency likely leads to a state of ‘involuntary immobility’ (Carling and Schewel Citation2018), where desires for onward movement remain unfulfilled.

In this paper, we examine how international refugee governance under the ‘grand compromise’ shapes refugees' feelings of involuntary immobility. Refugees in first-asylum countries are subject to the decisions of ‘street-level bureaucrats’ (Lipsky Citation1980) which, under the ‘grand compromise’, are charged with distinct tasks. Agents of the host state are primarily in charge of security and international humanitarian actors (who we refer to as ‘external actors’) provide aid, legal registration and other services.Footnote2 Because refugees face important barriers to self-sufficiency, they must routinely interact with these governance actors who, in turn, can expand and restrict their access to resources, shaping their day-to-day agency (Carlson, Jakli, and Linos Citation2018; Grabska Citation2008; Hynes Citation2003; Kagan Citation2012; Ostrand and Statham Citation2021; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009; Turner Citation2009).

We argue that external and host country actors can have different effects on refugees' aspiration and perceived ability to relocate away from the first-asylum country (e.g. Carling and Schewel Citation2018; UNDP Citation2009) through the goods and services they are in charge of providing under the ‘grand compromise’ (e.g. Cuéllar Citation2005; Kagan Citation2012; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009) and, thus, not solely in terms of the policies and laws they write (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker Citation2019). Specifically, we suggest that, if these two types of actors perform their roles effectively, they provide different quantities of agency-enhancing benefits. Host actors in charge of security provide a good that is agency-enhancing and suppressing at the same time – that is, they expand or facilitate refugees' existing choices by directly suppressing others. A host state that provides protection is likely to do so at the expense of restricting (others') freedom of movement. All in all, because external and host actors provide different amounts of these two distinct benefits under the ‘grand compromise’, they will also have distinct effects on refugees' aspirations and perceived ability to relocate.

To address this argument requires that we pay close attention both to the roles played by governance actors in forming the richness of refugees' lived experiences on the ground in host countries as well as refugees' prospective evaluation of future relocation options. For this, we present evidence from an original, representative survey () among Syrian refugees hosted in Lebanon, which includes two forms of data. Given that refugees live complex lives in their host countries, we first draw upon rich observational data that enable us to explore the heterogeneity of respondents' experiences and perceptions. Our findings demonstrate one clear way in which the ‘grand compromise’ affects refugee decision-making and planning. We show that the perceived effectiveness of external humanitarian actors is associated with a lower aspiration, but a higher perceived ability for onward movement, reflecting a higher state of social and economic well-being. The perceived effectiveness of host country actors, on the other hand, is associated with a higher aspiration to relocate and a lower perceived ability to do so. This is consistent with the tendency towards involuntary immobility (Carling Citation2002), as well as a reminder that providing refugees with effective security can simultaneously reduce their feeling protected and, thus, negatively impact their sense of agency.

To probe this finding further, we rely on a modified conjoint experiment. In this experiment we present respondents with relocation alternatives with varying levels of legality, thereby increasing their ability to relocate. We then ask them their preference about relocating to a third country, staying in Lebanon, or returning to Syria given the relocation alternatives with which they were presented. The extent to which a respondent chooses to stay when given the opportunity to relocate legally reflects their degree of involuntary immobility. A voluntarily immobile refugee will choose to stay in Lebanon even when they are given the opportunity to resettle. An involuntarily immobile refugee, by contrast, will choose to resettle when given the opportunity. In line with our observational findings, we find that refugees who believe host actors are effective are more likely to choose relocation over staying when presented with a legal opportunity. Refugees who view external actors as effective are no more likely than others to choose relocation when presented with a resettlement opportunity.

Our results show that effective governance by both sets of actors – host and external – within the ‘grand compromise’ arrangement will tend to decrease relocation – albeit in contrasting ways. When refugees believe the UNHCR is effective at dealing with refugee issues, they are significantly less likely to aspire to migrate but significantly more likely to feel able to do so.Footnote3 When refugees believe the host government is effective at providing security, they are significantly more likely to aspire to migrate but significantly less likely to feel able to do so. Confidence in the justice system displays the same pattern. Existing evidence suggests that, though most refugees consider a return to Syria in the near term unrealistic, many would prefer to remain close to home in case they can return, rather than resettling further away (Ghosn et al. Citation2021; Tiltnes, Zhang, and Pedersen Citation2019). This is, of course, contingent on whether refugees feel they are able to endure the remainder of their stay in the first-asylum host country. Here, governance actors appear to play an important role. Our results suggest that effective agency-enhancing actors may allow refugees to remain optimistic despite conditions that are objectively difficult (see, also, Tiltnes, Zhang, and Pedersen Citation2019, 135). On the other hand, effective host country actors appear to make refugees' stay less tolerable.

This paper contributes to our understanding of refugee decision-making. First, by developing a distinct theory of subsequent movement to a third country – which draws on literature from different disciplines and subfields – we depart from the standard model of decisions to flee countries of origin. Second, we address the long-standing ‘mobility bias’ in migration literature by examining the role of governance actors in creating different types of immobility. Research in migration has overwhelmingly focused on the determinants of migration, despite the fact that most people in the world do not migrate. This scholarly bias neglects not only the unique determinants of staying but also fails to disaggregate the types of immobility that are meaningful for refugees: For some, immobility may be voluntary decision and for others it may be involuntary (Braithwaite, Cox, and Ghosn Citation2020; Carling and Schewel Citation2018; Schewel Citation2020). Finally, we go beyond the standard push-pull framework by developing and testing a theory on the role of international refugee governance on refugee preferences.

Theory

In this paper, we argue that governance actors – following an internationally-agreed division of labor – affect refugees' aspiration and perceived ability to relocate in different ways. We divide our theory in three parts. First, we discuss how governance actors affect agency – defined as the freedom to choose – by facilitating or restricting access to resources. We, then, discuss how the internationally-agreed division of labor – the ‘grand compromise’ of refugee policy – provides a schema for external and host country actors. This schema affects the extent to which each actor provides access to different resources – specifically to what we call agency-enhancing or partially agency-suppressing benefits. Finally, we build on the above to derive our expectations on how the grand compromise shapes refugees' aspiration and ability to relocate.

How governance actors affect agency

Refugees have traditionally been portrayed as ‘helpless victims’ and ‘passive aid recipients’ due to their extraordinary dependence on external and host actors. Nowadays, researchers generally reject the conception of refugees as passive or helpless (Krause and Schmidt Citation2020; Singh Citation2020). According to Singh (Citation2020, 1), ‘while it is generally accepted that existing structures and institutions at best fail them and at worst violate their human rights, there is a growing body of literature on refugee camps that advances a material focus on the everyday life of the refugee camp’. This burgeoning literature examines how refugees retain a certain degree of agency despite limiting structures and institutions – for example, by engaging in entrepreneurship, or politics (e.g. Betts Citation2021; Jacobsen Citation2005; Lecadet Citation2016; Sanyal Citation2014; Singh Citation2020).

However, while it is true that refugees will find ways to regain their agency despite the structures of refugee governance, governance actors should not be seen as uniformly suppressing refugee agency. Indeed, according to Giddens (Citation1976, 161), ‘structures must not be conceptualized as simply placing constraints on human agency, but as enabling’. A key way governance actors can affect refugee agency is by facilitating or constraining access to resources (Simon, Schwartz, and Hudson Citation2023). Refugee entrepreneurship in Kenya's Kakuma and Kalobeyei camps, for example, is fuelled by aid provided, in large part, by UN agencies (Betts et al. Citation2019). This is not limited to camp settings. In urban settings like Lebanon, cash assistance provided by the UN can allow refugees to participate in the economy (Chaaban et al. Citation2020), and effective security provided by host governments can unburden refugees from fear when pursuing routine activities (though as we will discuss later, security also limits refugees' agency) (Linn Citation2022). According to Sewell (Citation1992), ‘part of what it means to conceive of human beings as agents is to conceive of them as empowered by access to resources of one kind or another’. Access to resources such as material goods or safety structures refugees' choices and, therefore, their agency.

Because governance actors play different roles in providing access to resources, they affect refugees' agency in different ways. When governance actors effectively provide access to resources, refugees should generally perceive them to be primarily agency-enhancing. That is, they should expand choices or facilitate existing choices. By the same token, some governance actors may actively suppress agency. The benefits that governance actors provide may also be agency-enhancing and suppressing at the same time. Security is a key example. The co-existence of agency enhancement and suppression are central to what we perceive to be the core function of security in a conceptual sense: Law enforcement protects individuals from harm by limiting (other) individuals' actions. Effective security provision, therefore, both enhances agency by sometimes suppressing agency. We refer to these as partially agency-suppressing benefitsFootnote4.

The ‘grand compromise’: a schema for for the provision of benefits

In this paper, we argue that governance actors' effects on agency can be traced back to the ‘grand compromise’ of refugee policy (Cuéllar Citation2005) – a schema that determines the responsibilities of host and external actors. According to Sewell (Citation1992), schemas and resources (material or human), which jointly comprise structures, simultaneously effect one another. Resources are shaped by schemas and schemas are shaped by resources. As Sewell (Citation1992, 11) puts it, ‘a given number of soldiers will generate different amounts and kinds of military power [resources] depending on the contemporary conventions of warfare (such as chivalric codes), the notions of strategy and tactics available to the generals, and the regimes of training to which the troops have been subjected [schema]’. In the same way, the grand compromise is the schema under which street-level bureaucrats facilitate or restrict refugees' access to material or human resources.

According to the ‘grand compromise’, host states' main role is to provide security to refugee communities and protect citizens from refugeesFootnote5, while external actors take on many of the traditional roles of the state when dealing with refugee matters (Bidinger et al. Citation2014; Cuéllar Citation2005; Grabska Citation2008; Kagan Citation2012; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009). According to Bidinger et al.'s (Citation2014) legal review of refugee management responsibilities in first-asylum countries, the Lebanese state ‘functions primarily as a coordinator of services and a security gatekeeper’ (169); similarly, the Jordanian government ‘views its obligations towards refugees primarily through a national security lens’ (397). External actors, on the other hand, provide food, health, education, refugees' registration and status determination, as well as managing refugee resettlement. In Lebanon and Jordan, substantial control over the refugee situation has been ‘relinquished’ to international actors (Bidinger et al. Citation2014). All in all, external actors often function like a ‘surrogate state’ (Miller Citation2017; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009). In large refugee settlements across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia ‘one can find a humanitarian infrastructure dwarfing local government and dominated by international agencies based in the West, funded by Western states, and led by international staff’ (Kagan Citation2012, 4).

Refugees observe this division of labor and come to expect different things from host states and external actors (Grabska Citation2008; Kagan Citation2012; Slaughter and Crisp Citation2009; Turner Citation1999). Grabska (Citation2008, 86) suggests that urban refugees hosted in Egypt ‘do not see themselves as the [host] government's responsibility… Some refer to the UNHCR as their government: “we live in a country of UNHCR”’. Indeed, refugees in Egypt, Kenya, and Uganda, among other countries, have staged protests against the UNHCR rather than the host government, suggesting that refugees ‘perceived the UNHCR as somehow responsible for protecting the rights that the government was either not able or not willing to provide or to guarantee’ (Harrell-bond Citation2008, 223). On the other hand, the association between the host state and security is likely accentuated by security's ‘publicness’ (Sandler Citation2004); security is the ‘most visible and proximate instantiation of state power in many citizens’ lives' (Soss and Weaver Citation2017, 574).

All in all, following the schema of the grand compromise, host country actors are more likely than external actors to be associated with providing larger quantities of a benefit that has an agency-suppressing element – security – and lower quantities of agency-enhancing benefits than external actors.

How the grand compromise affects relocation

Refugees who lack agency regarding their earning capacity, their health, and their children's education, for example, many are likely to aspire to move elsewhere (de Haas Citation2014; Simon, Schwartz, and Hudson Citation2023). However, lacking agency where one lives is also often associated with a lack of freedom to choose whether to stay or to leave (de Haas and Rodríguez Citation2010; UNDP Citation2009). For example, individuals who lack opportunities to earn money and escape conditions of poverty are often those with the lowest ability to migrate (see, e.g. Hagen-Zanker, Mosler Vidal, and Sturge Citation2017). As such, lack of agency means simultaneously aspiring to relocate and being unable to do so (‘involuntary immobility’). Conversely, while greater agency may manifest in a greater ability to leave, it will also make temporary living in the first-asylum country more tolerable for refugees as they await return, thereby possibly lowering their aspiration to leave (‘voluntary (im)mobility’).

External actors. Following this logic, if external actors effectively provide higher quantities of benefits that enhance refugees' agency, staying in the host country may become more tolerable. This is not to say that humanitarian assistance can fulfill refugees' needs, or make them feel less ‘out of place’ (Yotebieng, Syvertsen, and Wah Citation2019). However, refugees may be more willing to remain in the host state until they are able to return home if external actors do a good job providing the goods and services they require. In other words, refugees in an impacted host state should be better off (have greater agency) than they would have been without any humanitarian assistance. As such, we hypothesize that:

H1a: Perceived effectiveness of external actors will be associated with a lower aspiration to relocate.

In general, greater agency can help potential migrants finance the costs of migration – i.e. increase their ability to migrate. However, in the case of refugees, the UNHCR plays a unique role: It manages and coordinates movement to third countries. As such, a perception that the UNHCR is competent and acting in their best interests would increase refugees' perceived ability to relocate. This is the case regardless of whether their perception of effectiveness is well placed (e.g. Kvittingen et al. Citation2019; Yotebieng, Syvertsen, and Wah Citation2019). Kvittingen et al. (Citation2019), for example, cite the case of asylum-seekers who are still in refugee status determination and resettlement processes and, ‘since UNHCR files remain open until a solution is found, those recognized as refugees many years earlier still held onto the slim possibility of resettlement, believing their files were “still being studied”’ (117). As such, we hypothesize that:

H1b: Perceived effectiveness of external actors will be associated with a higher perceived ability to relocate.

Host actors. Host country actors are likely to provide some quantity of agency-enhancing benefits (more on this below). However, they are chiefly responsible for security which, we have argued, simultaneously enhances and suppresses refugee agency. Because effective security provision both enhances and suppresses agency, individuals are likely to have ambivalent attitudes about it, particularly if they are less-advantaged and, therefore, more vulnerable to both crime and police-related harm (Armenta and Rosales Citation2019; Hagan et al. Citation2018; Linn Citation2022; Pratto, Sidanius, and Levin Citation2006). For example, Linn's (Citation2022) fieldwork among Syrian women in Lebanon finds that ‘whilst [refugee] women perceive… security providers in ambivalent terms, they are deeply appreciative of State security presence in urban areas which seem vulnerable to tension and conflict’ (1). Surveys have shown that security (as we define it here) is among refugees' top concerns (Alsharabati and Nammour Citation2017). Insecurity in camps, for example, can be so dire that refugees may fear simple routines like going to the bathroom (Human Rights Watch Citation2019). As such, we might expect that law enforcement agents who are doing their job well will provide the security refugees need to complete routine activities, leading to a lower aspiration to relocate.

On the other hand, security also places significant constraints on refugees' agency in other domains. Under an official mandate to protect refugees and citizens, security officials have a state-sanctioned power to restrict refugee movement. For example, Jordan penalized and prevented refugees from leaving camps, even when conditions inside are extremely dire (Human Rights Watch Citation2018). In Lebanon, access to spaces is regulated through curfews and checkpoints, resulting in refugees' ‘criminalization and immobilization’ (Sanyal Citation2018, see also, Fakhoury Citation2020; Janmyr Citation2016; Nassar and Stel Citation2019), thereby also restricting refugees' access to essential services (e.g. Parkinson and Behrouzan Citation2015). Because refugees are likely to have conflicting attitudes towards the role of effective security provision on their well-being, we choose to remain agnostic on the effects of host country actors on refugees' aspiration to relocate.

The effects of security on perceived ability to migrate are more clear, however. Effective security places significant constraints on refugees' livelihood strategies and will, therefore, result in a lower perceived ability to meet the costs of onward movement (Kvittingen et al. Citation2019). However, there are many other ways in which effective security may reduce perceived ability to migrate. States may physically restrict refugees' exit from the host country. For example, to leave Lebanon, Syrian refugees need to secure an exit visa. For many, an exit visa is impossible to attain because it would require regularizing their legal status and settling any unpaid residency bills. If attempting to leave Lebanon through an official border without an exit visa, refugees are likely to be stopped by Lebanese security and would have to either pay the unpaid fees or receive a re-entry ban (Janmyr Citation2016, 74). Accordingly, the UNHCR is more likely to intervene and possibly provide resettlement based on individual protection needs if the state does not provide effective security (UNHCR Citation2011, 247). As such, regarding ability to relocate, we hypothesize that:

H2: Perceived effectiveness of host actors will be associated with a lower perceived ability to relocate.

We have argued that if governance actors perform their duties effectively, they should increase refugees' agency in general. Refugees' agency, in turn, affects their aspiration and perceived ability to relocate resulting in either voluntary or involuntary immobility. We have also argued that security – the main duty of the host state enhances certain dimensions of agency at the risk of suppressing others. And under the grand compromise, external actors are likely to provide a greater quantity of agency-enhancing benefits. Even if refugees are imperfectly aware of the division of labor, they should have a good idea of the relative role of each actor in providing higher or lower quantities of each kind of benefit (e.g. Grabska Citation2008; Harrell-bond Citation2008). In Appendix A, we examine how Syrian refugees in Lebanon access housing, household necessities, schooling and healthcare goods and services in Lebanon, and the governance actors with whom they interact in order to obtain these services. We complement a review of existing evidence with original interviews with representatives of two aid organizations working with refugees in Lebanon.

Research design and sample

We surveyed 1,750 Syrian refugees throughout Lebanon during June and July 2018Footnote6. Our sampling proceeded as follows. First, we grouped the 8 governorates of Lebanon into four contiguous governorate-pairs (regions) and used the known distribution of refugees in these regions to determine a proportionally representative survey distribution per region (See ). We further distributed the governorate-pair survey quota across the 24 districts of the Lebanon, so that the number of responses per district would be proportional to the size of the refugee population per district, as determined by the UNHCR in 2018. We then selected towns or settlements within each district with the probability of being selected proportional to the size of the refugee population in each town or settlement.

Table 1. Distribution of Survey Sampling Population For Syrian Refugees by Governorate-Pair.

Because all refugees must register with municipalities, we obtained a household listing of Syrian refugees for each town. Typically, Syrian refugee households were clustered within a town. We used systematic sampling to select households from this listing: The starting household in each town or settlement was randomly selected from the list until an adult respondent willing to participate was found (the enumerator team only selected one individual per household). The team then skipped three houses to go to the fifth house on the list to request their next respondent. We applied the same method in unofficial settlements: after the first tent was chosen, enumerators skipped the next three and chose the fifth tentFootnote7.

shows descriptive statistics for our main variables of interest.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics.

Analyses and results

We pursue two complementary modelling strategies drawing upon the data from these surveys. We use multivariate observational survey analysis followed by a survey experiment to examine our theoretical expectations related to involuntary immobility (H1a, b and H2). Our strategy focuses on gauging respondents' preferences for the future while considering their actual perceptions and experiences with governance actors in their time in Lebanon. We do so in order to learn from and convey refugees' actual lived experiences and conditions in exile (see Appendix B.1. on the principle of beneficence). For our observational analyses, we look at responses to two questions about relocation. The first question asks refugees to identify their aspiration to relocate: ‘Whether or not you think you are ABLE to do so, how much would you like to move on to another country (not including Syria)?’ The second question asks them to assess their ability to relocate: ‘How easy do you think it will be for you to move on to another country (not including Syria)?’

To test hypotheses H1 and H2, respectively, we include indicators on the perceived effectiveness of the UNHCR (Effectiveness UNHCR) and the host government (Effectiveness LBN Gov.) in dealing with issues affecting refugees. Specifically, these questions are worded: ‘How would you evaluate [UNHCR/ Lebanese Government] in dealing with the refugee issues in Lebanon?’ with a 5-point scale ranging from strongly negative to strongly positive. We have argued that the Lebanese government's main role is that of security provider. As such, we also include a variable measuring confidence in the Lebanese justice system (Conf. Justice System). Specifically, this variable measures' respondents confidence that crime would be dealt with if reported to the municipal authority, police and security forces, and the Lebanese army. For this analysis, we measure confidence in all three agencies as a combined indicator. According to Linn (Citation2022, 13–14), Syrian refugees cannot readily distinguish between the army and other security forcesFootnote8.

Our first analyses, shown in , test our expectations regarding the effect of perceived effectiveness on respondents' aspiration and perceived ability to relocate (H1 and H2). We present four models for each of our two dependent variables: Model 1 is our baseline model, presenting our main independent variables of interest, Effectiveness UNHCR and Effectiveness LBN Gov.; Model 2 includes standard demographics; Model 3 is our fully specified model, including our baseline variables, standard demographics, current living conditions, as well as attitudes toward general host country conditions and towards an eventual return to Syria. Model 4 includes Conf. Justice System instead of Effectiveness LBN Gov..

Table 3. Aspiration and ability to relocate: Regression results.

We control for several factors in Models 2 and 3. Relating to the UNHCR, we pay attention to factors that may affect the probability that an individual will receive UNHCR aid (employment status, UNHCR registration, or residence in a camp or in a majority Syrian neighborhood) or will be prioritized in resettlement programs (crime victimizationFootnote9, family abroad). Relating to the host country, we pay attention to factors that affect individuals' probability of interacting with security agents – for example, because of victimization or simply because of where they live – or may affect the experience of interacting with security agents due to, for example, their gender (Linn Citation2022) or legal registration (Sanyal Citation2018). Given the seven-point scale of our dependent variables, and for ease of interpretation, we use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

We find robust results in support of hypotheses H1 and H2 across all four models. When refugees believe that the UNHCR deals effectively with refugee issues they have a significantly lower aspiration to relocate but a higher ability to do so. When refugees believe that the host government – which is in charge of providing security – is effective, they have a significantly higher aspiration to relocate but a lower ability to do so. Confidence in the justice system displays the same pattern. These results indicate that, while perceived competence of host actors, who provide a partially agency-suppressing benefit, is associated with a tendency towards involuntary immobility, the perceived competence of external actors is associated with higher levels of voluntary immobility. That voluntary immobility is associated with the perceived effectiveness of external actors – even after we account for variation in current host country conditions and attitudes about the future – is an important finding. This suggests that strengthening the capacity of external actors (which are consistently underfunded) to increase overall effectiveness may allow refugees to remain optimistic despite their objectively difficult living situations. Many refugees prefer to remain close to home in case they can return, rather than resettling further away (Ghosn et al. Citation2021; Tiltnes, Zhang, and Pedersen Citation2019). This finding suggests that well-functioning organizations that enhance refugees' agency may have an important and positive influence on refugees' well-being, and help them endure the remainder of their stay in the host countryFootnote10.

Turning to our control variables, we find that unemployment is associated with a higher aspiration to relocate but we do not see statistically significant effects for perceived ability to relocate. In Lebanon, refugee employment is often infrequent and informal; refugees often rotate in and out of precarious jobs (Harb, Kassem, and Najdi Citation2019). As such, the general welfare of the host country may be a more stable indicator of future economic prospects than whether one is currently employed. Those who perceived the situation in Lebanon to be deteriorating perceived a lower ability to relocate. This is to be expected: The host country's economic and institutional environment is likely to affect refugees' economic prospects and ability to meet the costs of onward movement. We also find that whether an individual has suffered physical or verbal abuse in Lebanon does not have significant effects on aspirations to relocate. However, we do see a strong and positive relationship between individuals' experiences with verbal abuse and their perceived ability to relocate. Those who have been victimized are more likely to be prioritized for UNHCR resettlement (Grandi, Mansour, and Holloway Citation2018; UNHCR Citation2011)Footnote11. As expected, we find that having networks abroad is associated with a higher aspiration to migrate, but we do not find significant effects between this variable and perceived ability to migrate.

Survey experiment

To probe these findings further, we can also examine how perceptions of governance effectiveness affect involuntary immobility by randomly varying one of its components. Specifically, our next analysis examines whether refugees' perceptions of our two governance actors affects their aspiration to relocate when given a legal opportunity to do so. We expect that refugees with a more positive perception of external actors are less likely to aspire to relocate even when a legal opportunity is available (their ability to relocate is increased), relative to those with a more negative perception. This would indicate a lower level of involuntary immobility associated with the perceived effectiveness of external actors. We are theoretically agnostic about the role of host country actors but, if experimental results align with our observational results, refugees with a more positive perception of host actors are more likely to aspire to relocate when a legal opportunity, relative to those with a more negative perception, indicating higher levels of involuntary immobility.

To create two randomly assigned ‘ability’ conditions and examine their effects on aspiration to relocate, we used a modified choice-based conjoint experiment. Conjoint experiments ask respondents to evaluate and choose from different pairs of hypothetical alternatives described by randomized levels of a set of attributes. They are generally used to examine the influence of attributes (i.e. features) on choices – in our case, the choice to relocate. Conjoint experiments have a number of design advantages for our purposes. First, they present respondents with a more realistic multidimensional choice framework (Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Citation2022). Relocation alternatives vary a great deal (Brekke and Brochmann Citation2015) and, with a conjoint, we can make this variation explicit and identifiable. An additional advantage of this approach is that rather than directly asking for attitudes, preferences are calculated indirectly from the alternative selections, thereby minimizing social desirability bias related to irregular movement (Horiuchi, Markovich, and Yamamoto Citation2022).

The conjoint experiment was embedded into our survey. A randomly-selected sub-sample of 402 respondents were given 5 choice tasks, giving us a total of 1,828 complete observations split into two treatment conditions (more details below)Footnote12. The choice tasks asked respondents to choose between two relocation alternatives, each described by four attributes: the level of abuse that refugees might expect to experience in the country; the ease of finding work there; the diaspora present in that location; and whether legal resettlement was offeredFootnote13. The level for a given attribute in each choice alternative was randomly selected from three or four options shown in .

Table 4. Attributes and Levels.

The modified conjoint

Every time, after choosing a relocation alternative from the two alternatives given, respondents were asked a follow-up question asking them whether they preferred the relocation option they had just selected over staying in Lebanon or returning to Syria. We focus on this latter post-conjoint question in our subsequent analysis, but present a standard conjoint analysis examining the influence of each factor in their choice in Appendix F. The post-conjoint question is asked at the choice task level. Specifically, respondents are asked: ‘Keep in mind the answer you just provided us [referring to their consideration of conjoint task pairs]. Now, I would like to consider a situation where you and your family can return to your hometown in Syria without fear of violence. Please note that it is OK to change your answer. I would now like you to consider 3 options: (1) Resettle to the new country you chose (2) Return to Syria or (3) Stay in Lebanon. Which of these three options would you choose?’.

As such, when conducting our analysis, we pooled choice tasks (the pairs of options that subjects were given in the conjoint) into a legal category, comprised of choice tasks with at least one legal resettlement alternative from which to choose, and a no legal category. The no legal category was comprised of choice tasks with two no-resettlement alternatives, such that refugees had no legal options from which to choose.Footnote14 In Appendix G we present an alternative specification, where the legal category is composed of choice tasks with strictly two legal resettlement alternatives, mirroring the no legal category and we find substantively similar results. Recall that attribute levels and, therefore, choice task combinations are randomly assigned. As such we may consider the legal and no legal categories to be randomly assigned experimental conditions.

Having constructed our legal and no legal conditions, we examine: (i) whether a randomly assigned ability to relocate increases the likelihood of choosing relocation over staying or returning to Syria, and most importantly (ii) whether this effect is moderated by perceptions on the effectiveness of each governance actor.

Survey experiment results

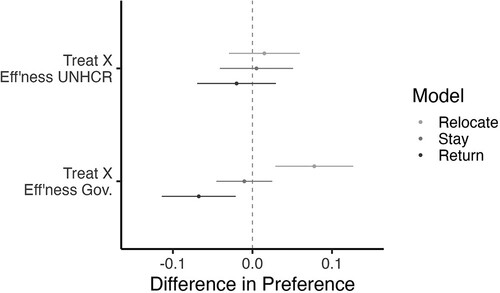

Overall, we find that respondents are significantly more likely to choose relocation when it is legal (the ‘high ability’ condition) (, p<0.001). presents our main results. In the first model, we examine whether refugees' perceptions of each governance actor affects their preference to relocate (relative to staying or returning) when given the option to resettle legally. For completeness, the figure also separately models the preference to stay and the preference to return relative to the remaining two options. For ease of interpretation, we estimate linear models, as recommended by Gomila (Citation2021). In all models, standard errors are clustered by respondent, and we include fixed effects for governorate to adjust for the sampling strategy (see ‘Research design and sample’ section). Each coefficient represents the interaction between the treatment – legal resettlement – and our effectiveness indicator.

Figure 1. Survey experiment results. Treatment is the opportunity to relocate legally. Coefficients reflect interactions between treatment and perceived effectiveness of external (UNHCR) or host government. OLS Models include standard errors clustered by respondent, and Governorate-level fixed effects.

We find that UNHCR effectiveness does not significantly moderate refugees' preference for relocation. In other words, refugees that consider the UNHCR to be effective are as likely to choose relocation as those who do not. Taken together with our survey results, we may conclude that the perceived effectiveness of external actors may have null to negative effects on aspiration to relocate. However, our results for Government Effectiveness align with our previous results: The more effective the government is perceived to be, the more likely refugees are to choose relocation relative to staying or returning. This is, perhaps, our most counter-intuitive finding, because it forces us to move beyond viewing effective security as being equivalent to effective protection. Instead, it appears that effective security might strip away or undermine a refugee's sense of agency.

Alternative explanations

Some alternative interpretations may explain our observational findings. First, our theory suggests that if refugees perceive the UNHCR to be more effective, they will be less likely to desire relocation. However, it is also possible that if refugees have a stronger desire to migrate, they will also be more likely to believe the UNHCR is less effective. The most straightforward mechanisms through which this might happen are as follows. First, refugees with a higher desire to relocate are more likely to approach UN agents multiple times to ask them about resettlement and become frustrated at the UNHCR's lack of response. Alternatively, they might wish to apply for resettlement directly and find that they cannot do so (UNHCR Citation2022). These mechanism would lead to observationally-equivalent results: A higher aspiration to relocate would be associated with a perception that the UNHCR is less effective.

We control for refugee characteristics that make a refugee more or less likely to receive relocation assistance by the UNHCR. The UNHCR prioritizes people who are at most risk of serious harm in the host country and their prospects for returning safely to their home country, considering family unity (UNHCR Citation2022). In Models 3 and 4 in , we control for refugees' experience with verbal abuse, and their experience with physical abuse in Lebanon. We also control for whether they believe the living situation in Lebanon has deteriorated and whether they live in a camp. We also control for whether they consider a return to Syria viable, as a proxy for their prospects of returning safely to Syria, and whether they have networks abroad – as a proxy for family unity. We also control for whether they are registered with the UNHCR. The inclusion of these control variables does not affect the sign and only weakly affects the magnitude of our main effects.

We might also suggest an alternative mechanism with observationally-equivalent results: If a refugee has a lower aspiration to migrate, they will likely perceive a longer time horizon for their stay in Lebanon. Consequently, we may argue, refugees with a lower desire to migrate may choose to be positive about how the UNHCR is managing refugee situations. However, to convincingly support this mechanism, we would have to also observe a positive attitude toward the Lebanese government among individuals with a lower desire to relocate. Both actors jointly constitute refugees' ‘context of reception’ and will affect their future experiences.

Second, our theory suggests that if the UNHCR is perceived to be more effective, then refugees will have a higher perceived ability to relocate. Reverse causality would suggest that a higher perceived ability to relocate will cause refugees to perceive the UNHCR to be more effective. Here, we could argue that refugees who have a higher perceived ability to migrate legally are more likely to engage with the UNHCR to obtain resettlement. Moreover, we may argue that, rather than feeling frustrated, refugees' engagement with the UNHCR causes them to believe that the UNHCR is more effective. In other words, refugees may simply be participating in ‘wishful thinking’: They want the UNHCR to be effective, therefore they convince themselves of this fact. We may also doubt this mechanism, however, because high aspiration to relocate – which should be a necessary condition for engaging with the UNHCR for this purpose – is negatively associated with UNHCR effectiveness.

Relating to the host government, our theory suggests that the perceived effectiveness of host actors will be associated with a lower perceived ability to relocate (our theory is agnostic on the effect of host actors on aspiration to relocate). It is possible that refugees who apriori consider themselves unable to relocate will think the government is more effective. This is akin to a ‘sour grapes’ hypothesis: Refugees who do not believe they are able to relocate might convince themselves that their current situation is better. However, once again, this causal relationship should also generalize to our findings on the UNHCR. In other words, refugees with a lower ability to relocate should believe all actors managing refugee situations are more effective; we should see parallel rather than opposing effects across H1 and H2. That the relationships between ability and the perceived effectiveness of each actor go in opposite directions suggests that the actors themselves are more likely to be the causal agents.

Discussion

In the ‘grand compromise’ of refugee policy (Cuéllar Citation2005), poorer host countries agree to provide security and keep refugee populations locally hosted, while wealthy nations fund international humanitarian efforts on the ground but take in fewer than one fifth of the world's refugees. We examine the ‘grand compromise’ from refugees' perspectives. We argue that refugees' preferences on whether to stay or relocate are a function of their perceptions of the effectiveness of host state and external governance actors managing refugee situations on the ground.

Using an original survey among Syrian refugees hosted in Lebanon, we find that when refugees believe external actors are performing well, they are significantly less likely to aspire to migrate but significantly more likely to feel able to do so, reflecting greater agency. On the other hand, when refugees believe the host government is effective at providing security – a partially agency-suppressing benefit – they are significantly more likely to aspire to migrate but significantly less likely to feel able to do so, indicating a greater sense of involuntary immobility. This finding appears to reflect a reality in which refugee agency is undermined by effective security for the very reason that this does not necessarily provide them with effective protection. Our second set of results – a survey experiment – show similar results for our host country actor. When refugees are given a hypothetical opportunity to relocate (legal resettlement), they are more likely to choose to relocate when they perceive the host country government to be effective than when they perceive it to be ineffective. In the survey analysis, we do not find any effects – positive or negative – for external actors.

Our results show that international arrangements like the ‘grand compromise’ can have clear implications on refugee preferences. First, if external actors are able to perform more effectively, their perceived ability to relocate increases – but refugees' preference for staying in the first asylum country may increase as well. In other words, enhancing refugee agency by strengthening the UNHCR works in the interest of donors who are, primarily, interested in containing refugee movement (Betts Citation2021). Paradoxically, domestic actors – who are often uninterested in hosting refugees – are likely to render refugees involuntarily immobile by restricting their agency. All in all, this explanation has two implications on our understanding of the grand compromise. First, this international arrangement may explain why so few refugees relocate despite dire living conditions. Second, it speaks to debates on whether the UNHCR – as a surrogate state – should be providing security to refugees (e.g. Cuéllar Citation2005; Kagan Citation2012). As the arrangement stands, host and external actors appear to be working at cross-purposes. A coherent policy framework that prioritizes enhancing refugee agency is in all parties best interest: donors, hosts and refugees.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.8 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In 2018, less than 3% of refugees in first-asylum countries returned home, and fewer than 1% were formally resettled to a wealthy third country (UNHCR Citation2018a).

2 It is worth noting, as well, growing attention is paid to extraterritorial management of immigration through which countries of the Global North seek to regulate immigration in advance of their own physical borders. In other words, we can add representatives of foreign governments to the list of potential ‘street-level bureaucrats’ (Ostrand Citation2020). However, we do not consider these foreign agents in our discussion, because they were not present in the Lebanese case with respect to the hosting of Syrian refugees in 2018.

3 Given that international humanitarian actors appear to be increasingly taking on important roles in the wealthier states in this process, e.g. Micinski (Citation2022) discussion of EU, UNHCR, and charitable organizations' efforts to support refugees in Italy and Spain, these findings may now travel beyond our initial dichotomy of wealthy vs. first asylum countries.

4 This definition relates to security measures and practices at an aggregate level: Not every security measure, taken independently, will enhance and suppress agency for a given individual.

5 Following Cuéllar (Citation2005), we consider security in a refugee context to refer to: (1) the protection of refugees' physical integrity from threats of violence, or non-violent acts which may deprive them of resources (e.g. theft). These acts may originate from other refugees or surrounding populations, or (2) protection of citizens from risks that refugees may be perceived to pose, such as criminal activity or conflict. We do not mean to claim that host states adequately protect refugees and citizens in this way; we simply claim that this is their role.

6 Approved by University of Arizona Human Subjects Committee, number: 1612089212. Please see Appendix B for a full account of ethical considerations such as minimizing risk to respondents and data security, and how we have addressed them.

7 About 70% of refugees live in residential buildings and 30% in unofficial settlements or camps. We aimed to ensure that the distribution of survey responses reflected the geographic distribution of the refugee population.

8 There is significant overlap in responses: 98% of respondents either had no confidence in any of the three agencies or had confidence in all of them.

9 This relates to resettlement due to lack of effective protection. See UNHCR (Citation2011).

10 In Appendix E, we examine the the extent to which these factors moderate our relationships of interest.

11 Threat to an individual's physical safety or fundamental human rights may qualify an individual for resettlement based on ‘individual protection needs’. Resettlement is commonly pursued only if protection by the host state cannot be re-established (UNHCR Citation2011, 247–249).

12 91% of all generated choice tasks were completed, the rest were non-response.

13 We keep the task simple and short to minimize fatigue among over-researched respondents (Sukarieh and Tannock Citation2013, see also Appendix B).

14 In constructing these two groups, we placed no restrictions on all other characteristics of the choice.

References

- Abdelaaty, Lamis Elmy. 2021. Discrimination and Delegation: Explaining State Responses to Refugees. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alsharabati, Carole, and Jihad Nammour. 2017. “Survey on Perceptions of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Between Resilience and Vulnerability.” Working Paper. Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth.

- Armenta, Amada, and Rocío Rosales. 2019. “Beyond the Fear of Deportation: Understanding Unauthorized Immigrants' Ambivalence Toward the Police.” American Behavioral Scientist 63 (9): 1350–1369.

- Betts, Alexander. 2021. The Wealth of Refugees: How Displaced People Can Build Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Betts, A., A. Delius, C. Rodgers, O. Sterck, and M. Stierna. 2019. Doing Business in Kakuma: Refugees, Entrepreneurship, and the Food Market, 1–44. Technical Report. Refugee Studies Centre. Accessed July 01, 2024. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:d5e87275-48af-469e-9fea-c1484b3a11f2.

- Bidinger, Sarah, Aaron Lang, Danielle Hites, Yoana Kuzmova, Elena Noureddine, and Susan M. Akram. 2014. Protecting Syrian Refugees: Laws, Policies, and Global Responsibility Sharing. Technical Report.

- Braithwaite, Alex, Joseph M. Cox, and Faten Ghosn. 2020. “Should I Stay Or Should I Go? The Decision to Flee Or Stay Home During Civil War.” International Interactions 47:221–236.

- Brekke, Jan Paul, and Grete Brochmann. 2015. “Stuck in Transit: Secondary Migration of Asylum Seekers in Europe, National Differences, and the Dublin Regulation.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (2): 145–162.

- Carling, Jørgen. 2002. “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28 (1): 5–42.

- Carling, Jørgen, and Kerilyn Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963.

- Carlson, Melissa, Laura Jakli, and Katerina Linos. 2018. “Rumors and Refugees: How Government-Created Information Vacuums Undermine Effective Crisis Management.” International Studies Quarterly 62 (3): 671–685.

- Chaaban, Jad, Nisreen Salti, Hala Ghattas, Wael Moussa, Alexandra Irani, Zeina Jamaluddine, and Rima Al-Mokdad. 2020. Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance in Lebanon: Impact Evaluation on the Well-Being of Syrian Refugees. Technical Report March.

- Crawley, Heaven, and Jessica Hagen-Zanker. 2019. “Deciding Where To Go: Policies, People and Perceptions Shaping Destination Preferences.” International Migration 57 (1): 20–35.

- Cuéllar, Mariano-Florentino. 2005. “Refugee Security and the Organizational Logic of Legal Mandates.” Georgetown Journal of International Law 37:583.

- de Haas, Hein. 2014. “Migration Theory: Quo Vadis?” International Migration Institute Working Paper. Issue 100. November 2014. University of Oxford.

- de Haas, Hein, and Francisco Rodríguez. 2010. “Mobility and Human Development: Introduction.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 11 (may): 177–184.

- Fakhoury, Tamirace. 2020. “Refugee Return and Fragmented Governance in the Host State: Displaced Syrians in the Face of Lebanon's Divided Politics.” Third World Quarterly 42 (1): 162–180.

- Ferris, Elizabeth. 2018. When Refugee Displacement Drags on, is Self-Reliance the Answer?, 1–3. Brookings Institute. June 19, 2018. Accessed July 01, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/when-refugee-displacement-drags-on-is-self-reliance-the-answer/.

- Ghosn, Faten, Tiffany Chu, Miranda Simon, Alex Braithwaite, Michael Frith, and Joanna Jandali. 2021. “The Journey Home: Violence, Anchoring, and Refugee Decisions to Return.” American Political Science Review 115 (3): 982–998.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1976. New Rules of Sociological Method: A Positive Critique of Interpretive Sociologies. London: Hutchinson.

- Gomila, Robin. 2021. “Logistic Or Linear? Estimating Causal Effects of Experimental Treatments on Binary Outcomes Using Regression Analysis.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 150 (4): 700.

- Grabska, Katarzyna. 2008. “Brothers or Poor Cousins? Rights, Policies and the Well-Being of Refugees in Egypt.” In Forced Displacement, 71–92. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grandi, Francesca, Kholoud Mansour, and Kerrie Holloway. 2018. Dignity and displaced Syrians in Lebanon ‘There is No Karama Here’, 1–29. London: Humanitarian Policy Group (Overseas Development Institute).

- Hagan, John, Bill McCarthy, Daniel Herda, and Andrea Cann Chandrasekher. 2018. “Dual-Process Theory of Racial Isolation, Legal Cynicism, and Reported Crime.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (28): 7190–7199.

- Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, Hannah Postel, and Elisa Mosler Vidal. 2017. “Poverty, Migration and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” ODI Briefing, September 2017. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10761.pdf.

- Harb, Mona, Ali Kassem, and Watfa Najdi. 2019. “Entrepreneurial Refugees and the City: Brief Encounters in Beirut.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (1): 23–41.

- Harrell-bond, Barbara. 2008. “Protests Against the UNHCR to Achieve Rights: Some Reflections.” In Forced Displacement, 223–241. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Horiuchi, Yusaku, Zachary Markovich, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2022. “Does Conjoint Analysis Mitigate Social Desirability Bias?” Political Analysis 30 (4): 535–549.

- Human Rights Watch. 2018. Jordan: Step Forward, Step Back for Urban Refugees. Technical Report.

- Human Rights Watch. 2019. Greece: Camp Conditions Endanger Women, Girls. Technical Report.

- Hynes, T. 2003. “The Issue of ‘Trust’ or ‘Mistrust’ in Research with Refugees: Choices.” Caveats and Considerations for Researchers, New Issues in Refugee Research Working Paper (98).

- Jacobsen, Karen. 2005. The Economic Life of Refugees. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Janmyr, Maja. 2016. “Precarity in Exile: The Legal Status of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 35 (4): 58–78.

- Janmyr, Maja. 2017. “No Country of Asylum: ‘Legitimizing’ Lebanon's Rejection of the 1951 Refugee Convention.” International Journal of Refugee Law 29 (3): 438–465.

- Kagan, Michael. 2012. The UN ‘Surrogate State’ and the Foundation of Refugee Policy in the Middle East, 308–340. Davis: University of California. 18:2(201).

- Krause, Ulrike, and Hannah Schmidt. 2020. “Refugees As Actors? Critical Reflections on Global Refugee Policies on Self-Reliance and Resilience.” Journal of Refugee Studies 33 (1): 22–41.

- Kvittingen, Anna, Marko Valenta, Hanan Tabbara, Dina Baslan, and Berit Berg. 2019. “The Conditions and Migratory Aspirations of Syrian and Iraqi Refugees in Jordan.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (1): 106–124.

- Lecadet, Clara. 2016. “Refugee Politics: Self-Organized ‘Government’ and Protests in the Agamé Refugee Camp (2005–13).” Journal of Refugee Studies 29 (2): 187–207.

- Linn, Sarah. 2022. “Ambivalent (In)Securities: Comparing Urban Refugee Women's Experiences of Informal and Formal Security Provision.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 44:594–624.

- Lipsky, Michael. 1980. Street-Level Bureaucracy. New York: Russell Sage Found.

- Micinski, Nicholas R. 2022. Delegating Responsibility: International Cooperation on Migration in the European Union. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Miller, Sarah Deardorff. 2017. UNHCR As a Surrogate State: Protracted Refugee Situations. London: Routledge.

- Nassar, Jessy, and Nora Stel. 2019. “Lebanon's Response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis–Institutional Ambiguity As a Governance Strategy.” Political Geography 70:44–54.

- Ostrand, Nicole. 2020. “Hidden in Plain Sight: The UK's Extraterritorial Management of Immigration.” PhD thesis, University of Sussex.

- Ostrand, Nicole, and Paul Statham. 2021. “‘Street-Level’ Agents Operating Beyond ‘Remote Control’: How Overseas Liaison Officers and Foreign State Officials Shape UK Extraterritorial Migration Management.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1): 25–45.

- Parkinson, Sarah E., and Orkideh Behrouzan. 2015. “Negotiating Health and Life: Syrian Refugees and the Politics of Access in Lebanon.” Social Science and Medicine 146:324–331.

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, and Shana Levin. 2006. “Social Dominance Theory and the Dynamics of Intergroup Relations: Taking Stock and Looking Forward.” European Review of Social Psychology 17 (1): 271–320.

- Sandler, Todd. 2004. Global Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sanyal, Romola. 2014. “Urbanizing Refuge: Interrogating Spaces of Displacement.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (2): 558–572.

- Sanyal, Romola. 2018. “Managing Through Ad Hoc Measures: Syrian Refugees and the Politics of Waiting in Lebanon.” Political Geography 66:67–75.

- Schewel, Kerilyn. 2020. “Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies.” International Migration Review 54 (2): 328–355.

- Sewell, William H. 1992. “A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation.” American Journal of Sociology 98 (1): 1–29.

- Simon, Miranda, Cassilde Schwartz, and David Hudson. 2023. “Can Foreign aid Reduce the Desire to Emigrate? Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Southern Political Science Annual Conference, St. Petersburg, FL, January 2023.

- Singh, A. L. 2020. “Arendt in the Refugee Camp: The Political Agency of World-Building.” Political Geography 77 (2019): 102149.

- Slaughter, Amy, and Jeff Crisp. 2009. A Surrogate State?: The Role of UNHR in Protracted Refugee Situations. UNHCR, Policy Development and Evaluation Service.

- Soss, Joe, and Vesla Weaver. 2017. “Police Are Our Government: Politics, Political Science, and the Policing of Race-Class Subjugated Communities.” Annual Review of Political Science 20:565–591.

- Sukarieh, Mayssoun, and Stuart Tannock. 2013. “On the Problem of Over-Researched Communities: The Case of the Shatila Palestinian Refugee Camp in Lebanon.” Sociology 47 (3): 494–508.

- Tiltnes, Åge A., Huafeng Zhang, and Jon Pedersen. 2019. The Living Conditions of Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Fafo-Report. Amman: Fafo Research Foundation.

- Turner, Simon. 1999. “Angry Young Men in Camps: Gender, Age and Class Relations among Burundian Refugees in Tanzania.” UNHCR Working Paper: New Issues in Refugee Research 9(January 1999): 145–156.

- Turner, Simon. 2009. “Suspended Spaces-Contesting Sovereignties in a Refugee Camp.” In Sovereign Bodies: Citizens, Migrants, and States in the Postcolonial World, 312–332. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- UNDP. 2009. “Human Development Report 2009 Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development.” United Nations Development Programme.

- UNHCR. 2011. “Chapter 6: UNHCR Resettlement Submission Categories.” In UNHCR Resettlement Handbook, 243–296. Geneva: UNHCR.

- UNHCR. 2018a. Global Trends, 2018. Technical Report. Accessed July 01, 2024. https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html.

- UNHCR. 2018b. Jordan: Fact Sheet. Technical Report October.

- UNHCR. 2020. “Lebanon.” https://reporting.unhcr.org/lebanon.

- UNHCR. 2022. Resettlement: Frequently Asked Questions. UNHCR. Technical Report. Accessed July 01, 2024. https://help.unhcr.org/faq/how-can-we-help-you/resettlement/.

- UNHCR. 2024. “Figures at a Glance.” UNHCR.

- UNICEF. 2017. UNICEF Turkey 2017 Humanitarian Results. Technical Report December.

- Yotebieng, Kelly A., Jennifer L. Syvertsen, and Paschala Wah. 2019. “‘Is Wellbeing Possible When You Are Out of Place?’: Ethnographic Insight Into Resilience Among Urban Refugees in Yaoundé, Cameroon.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (2): 197–215.