Abstract

Aims

To characterize a US population of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) or chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) using CONTOR, a real-world longitudinal research platform that deterministically linked administrative claims data with patient-reported outcomes data among patients with these conditions.

Methods

Patients with IBS-C or CIC were identified using diagnosis and treatment codes from administrative claims. Potential respondents received a mailed survey followed by 12 monthly online follow-up surveys and 2 mailed diaries. Surveys collected symptom severity, treatment use, quality of life, productivity, and condition/treatment history. Comorbidities and healthcare costs/utilization were captured from claims data. Diaries collected symptoms, treatments, and clinical outcomes at baseline and 12 months. Data were linked to create a patient-centric research platform.

Results

Baseline surveys were returned by 2,052 respondents (16.8% response rate) and retention rates throughout the study were high (64.8%–70.8%). Most participants reported burdensome symptoms despite having complex treatment histories that included multiple treatments over many years. More than half (55.3%) were dissatisfied with their treatment regimen; however, a higher proportion of those treated with prescription medications were satisfied.

Limitations

The study sample may have been biased by patients with difficult-to-treat symptoms as a result of prior authorization processes for IBS-C/CIC prescriptions. Results may not be generalizable to uninsured or older populations because all participants had commercial insurance coverage.

Conclusions

By combining administrative claims and patient-reported data over time, CONTOR afforded a deeper understanding of the IBS-C/CIC patient experience than could be achieved with 1 data source alone; for example, participants self-reported burdensome symptoms and treatment dissatisfaction despite making few treatment changes, highlighting an opportunity to improve patient management. This patient-centric approach to understanding real-world experience and management of a chronic condition could be leveraged for other conditions in which the patient experience is not adequately captured by standardized data sources.

Introduction

Analyses of administrative claims data generated when patients interface with the healthcare system can help answer research questions regarding healthcare resource utilization, costs, and outcomes outside the highly controlled environment of a clinical trial. However, patient experience with a disease often is not fully captured by examining their interactions with healthcare providers. Factors such as symptom severity, quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and impact on work and other activities of daily living, while not well reflected in claims data, are integral to representing the whole human experience of a disease.

The complex interweaving of personal experience and healthcare resource use in chronic disease is exemplified by irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC). Affecting as much as 11% and 14% of the general population, respectivelyCitation1, these conditions are 2 of the most common functional lower gastrointestinal (GI) disorders in the US. IBS-C (characterized by recurrent abdominal pain associated with bowel symptoms of constipation) and CIC (characterized by infrequent bowel movements, hard or lumpy stools, straining, sensations of incomplete rectal evacuation or anorectal blockage, and the need for manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation) negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL)Citation2–4 and have substantial direct and indirect economic costsCitation5,Citation6. Persons with IBS-C have more productivity loss and missed days of work than healthy controlsCitation7, and annual direct medical costs for all IBS subtypes are estimated be as high as $10 billion. Although the economic consequences of CIC are not as well definedCitation8, patients with this condition incur significant incremental medical and pharmacy costs compared with controlsCitation6.

Despite the prevalence of IBS-C and CIC, their true impact is difficult to assess because patients frequently have symptoms for a long time prior to seeking medical assistance, potentially due in part to embarrassment or self-consciousness associated with these conditionsCitation9,Citation10. In addition, common treatments include over-the-counter (OTC) medications and home remedies, which are not captured in most existing standardized data sources. Furthermore, experiences with this disease can be very different among patients, and may vary over time; thus, including the individual patient perspective is critical for a “real-world” understanding. Finally, the primary outcome measures of successful IBS-C or CIC treatment, such as bowel movements and abdominal pain, are best captured from the voice of the patient because they are not readily available in existing standardized data.

Considering the difficulty of symptom assessment in conjunction with the complex treatment landscape for IBS-C and CIC—which includes dietary and lifestyle interventions, OTC medications (e.g. stool softeners, bulking agents, and laxatives), and prescription medications—a better understanding of the relationships among patient symptoms, treatments, outcomes, and costs requires a patient-centric observational study. While sources of general-population survey information are available (e.g. the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]Citation11), they may not be able to adequately address research questions about specific patient populations. To meet these specialized needs, we developed a longitudinal research approach (referred to as a “platform” in the context of this study) that enabled the present analysis of insured US patients with IBS-C/CIC. The Chronic Constipation and IBS-C Treatment and Outcomes Real-world Research Platform (CONTOR) deterministically linked clinical and economic data from administrative claims with prospective, longitudinal patient-reported outcomes (PRO) data to create a more comprehensive picture of the real-world IBS-C/CIC patient. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the value of linked claims and patient-reported data by using CONTOR to provide a detailed characterization of symptom history, treatment patterns, and outcomes among a US population of patients with IBS-C/CIC. The results presented represent a small selection of the analyses conducted.

Methods

Study design and data sources

CONTOR is an observational, longitudinal research platform using administrative claims data from the Optum Research Database (ORD) linked with prospective, longitudinal PRO data. The ORD is a de-identified research database that contains commercial medical and pharmacy claims information, is geographically diverse across the US, and is representative of the US insured population. Medical claims include diagnosis and procedure codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM); Current Procedural Terminology or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes; site of service codes; and paid amounts. Pharmacy claims include drug name, National Drug Code, dosage form, drug strength, fill date, number of days’ supply, and paid amounts for outpatient pharmacy services. Unlike patients in datasets such as NHANESCitation11, CONTOR patients were identified from administrative claims data and deterministically linked with PRO measures collected from surveys and condition-specific diaries completed by CONTOR respondents.

This study was approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (#14-387). No patient's identity or medical records were disclosed for the purposes of this study except in compliance with applicable law.

Study population

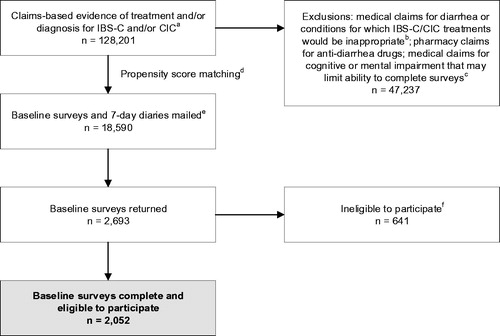

The study population comprised commercially insured adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with both medical and pharmacy benefits who had evidence of treatment for and/or diagnosis of IBS-C and/or CIC between 01 December 2012 and 30 June 2015 (patient identification period; ). To achieve a large and clinically diverse sample, patients were identified in 2 waves: the first from 01 December 2012 through 30 April 2014, and the second from 01 May 2014 through 31 January 2015. Patients were excluded if they had medical claims indicating severe diarrhea or other conditions for which IBS-C/CIC treatments would not be appropriate, pharmacy claims for anti-diarrhea medications (alosetron or diphenoxylate hydrochloride/atropine sulfate), or medical claims for profound cognitive or mental impairment that may limit the ability to participate in study surveys during the identification period. Exclusion criteria were implemented during the 9 months prior to baseline survey administration (sample identification period).

Figure 1. Patient selection and attrition. Notes: aAt least 1 pharmacy claim for linaclotide or lubiprostone, OR ≥1 medical claim for constipation (ICD-9-CM 564.0x), OR ≥1 medical claim for IBS (ICD-9-CM 564.1x) or abdominal pain (ICD-9-CM 789.0x) plus ≥1 pharmacy claim for a stool softener/laxative within 30 days. bDisqualifying conditions include ischemic colitis, opioid dependence or abuse, clostridium difficile, multiple sclerosis, gastrointestinal malignancy, intestinal malabsorption, Parkinson's disease, diabetic neuropathy, and pancreatitis. cAt least 1 claim with a diagnosis code for cerebral degeneration (including Alzheimer's disease; ICD-9-CM 331.x), dementia (ICD-9-CM 300.1x), or intellectual disorders (ICD-9-CM 317, 318.x, 319). dLinaclotide users were propensity score matched with lubiprostone/constipation patients on the basis of age; sex; geographic region; number of visits to a gastroenterologist; and the presence of claims for constipation, IBS, abdominal pain, neck/back pain, bloating, and depression/anxiety. eBaseline surveys and 7-day daily diaries were mailed to 2 groups of 9,590 and 9,000 unique patients, respectively. fPatients were ineligible to participate if they did not have internet access, were unable to complete the survey, were deceased, or did not meet ≥1 of the following criteria: patient-reported diagnosis by a health care provider of IBS-C, IBS, CIC, CC, or functional constipation on the baseline survey; pharmacy claim for linaclotide or lubiprostone; or fulfilled modified Rome III survey criteria for IBS-C or CIC based on patient self-report. Abbreviations. CC, chronic constipation; CIC, chronic idiopathic constipation; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification.

Propensity score matching and patient recruitment

The population of potential study participants who fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria included patients with pharmacy claims for prescription IBS-C and CIC treatments (linaclotide or lubiprostone) and/or evidence of constipation through medical and pharmacy claims. Some prescription treatments such as linaclotide were new to the US market at the time of sample identification; therefore, prior authorization requirements may have been in place at the time of sample identification, and linaclotide users may have had the most severe symptoms. In order to balance potential symptom severity differences among patients who were using linaclotide versus those who were not, propensity score matching was implemented as part of sample selection. Lubiprostone or constipation patients were matched to patients with claims for linaclotide based on the following covariates: age; sex; geographic region; number of visits to a gastroenterologist; and the presence of claims for constipation, IBS, abdominal pain, neck/back pain, bloating, or depression/anxiety. Eligible patients were invited to participate in the study via a mailed packet that included an invitation letter, statement of informed consent, baseline paper survey, baseline paper 7-day diary, and $5 cash incentive. Patients were included in CONTOR if they returned a completed baseline survey during the 9-week baseline data collection period and met at least 1 of the following criteria at baseline: patient-reported diagnosis by a healthcare provider of IBS-C, IBS, CIC, chronic constipation, or functional constipation on the baseline survey; a pharmacy claim for linaclotide or lubiprostone; or modified Rome III criteria for IBS-C or CIC.

Study observation period

Claims-based diagnoses and treatments were assessed for 6 months prior to and up to 12 months after the baseline survey date (study observation period, 18 months total). Patients were asked to complete 12 months of surveys; data from all returned patient surveys were included in the analyses. Because participants were not required to have continuous healthcare insurance coverage during the observation period or complete all surveys to remain in CONTOR, some had less than 18 months of claims data observation and/or less than 12 months of survey/diary data.

Collection of survey and diary data

In addition to the self-administered baseline paper survey, patients were asked to complete an online survey each month (monthly medication update or quarterly follow-up survey, depending on the month) over the 12-month post-baseline observation period. Questionnaire items from the monthly medication update were included in the quarterly surveys so that patients only received 1 CONTOR-related survey each month. Patients also completed a paper 7-day diary at baseline and Month 12. A combination of pre-paid incentives and post-paid payments was used. In addition to the pre-paid $5 cash incentive included with the initial survey packet, respondents received post-paid payments ranging from $10 to $20 for the baseline survey, baseline diaries, monthly medication updates, quarterly follow-up surveys, and follow-up diary. The maximum total amount a participant could have received was $180 for completion of all surveys and diaries over the study period. Survey response rates were calculated according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research guidance for mail surveysCitation12.

Study measures and outcomes

Patient-reported sociodemographic information, clinical history, and outcomes data collected via the surveys and diaries are summarized in . Symptom severity was measured by the disease-specific Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) questionnaire, consisting of 12 questions related to stool, abdominal, and rectal symptoms over a 2-week recall period with response options on a 5-point Likert scaleCitation13. Individual items in the 7-day daily diaries also assessed symptom severity specific to abdominal pain, bloating, discomfort, and distension reported on an 11-point numerical rating scale. Disease-specific HRQoL was measured by the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) questionnaire, consisting of 28 items related to worries and concerns, physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, and satisfaction over a 2-week recall period with response options on a 5-point Likert scaleCitation14. Condition-related impairment of work productivity and daily activity was measured via the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP)Citation15. IBS-C/CIC treatments used by patients were collected using pre-specified categories and free text which allowed the capture of prescription, OTC, and other treatments (such as dietary supplements and other home remedies). For some analyses, patient-reported treatments were categorized into medication groups: linaclotide, lubiprostone, polyethylene glycol (PEG)/osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives, and bulk laxatives. Use of nonpharmacologic treatments for IBS-C/CIC symptoms, such as diet change, exercise, or acupuncture, was captured on the baseline survey but not included among the treatments discussed here.

Table 1. Schedule of assessments.

Administrative claims–based data included geographic region based on health insurance coverage at baseline, Quan-Charlson comorbidity scoreCitation16 based on the presence of diagnosis codes on medical claims during the baseline period and 12-month observation period, and prescription treatments for IBS-C/CIC (pharmacy claims for linaclotide, lubiprostone, or prescription laxatives). Unlike treatments that patients reported via the surveys and diaries, the claims data captured filled prescriptions. All-cause (derived from claims with any diagnosis code) and GI-related (derived from claims with condition-specific diagnosis codes) healthcare costs and utilization were also collected via administrative claims data; per participant per month (PPPM) metrics were used to account for patients whose healthcare utilization and cost data were not available for the entire observation period. Healthcare costs (medical and pharmacy) were calculated as the combined PPPM health plan– and patient-paid amounts, adjusted to 2014 US dollars using the annual medical care component of the Consumer Price IndexCitation17. Healthcare utilization was calculated as PPPM counts of office visits, outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient admissions. GI-related healthcare utilization and medical costs were identified from medical claims with ICD-9/10-CM diagnosis codes for GI-related conditions (IBS, constipation, abdominal pain, bloating, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophagitis, dyspepsia, gallbladder/biliary disease, GI hemorrhage, hemorrhoids, peptic ulcer disease, fecal impaction, and anal fissure) in the primary or secondary position to best capture the constellation of IBS-C/CIC–related symptoms. Pharmacy costs for IBS-C/CIC–related medications (laxatives, bulk-forming agents, stool softeners, and combination products, plus linaclotide and lubiprostone) were categorized as GI-related.

Data analysis

As this was a hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-driven study, all variables were analyzed descriptively. Numbers and percentages are presented for dichotomous and polychotomous variables; means and standard deviations (SDs) are presented for continuous variables.

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Response rates

A total of 128,201 patients met the study inclusion criteria. Of those identified, 47,237 were excluded. After propensity score matching, a total of 18,590 patients were invited to participate in the study (). Complete baseline surveys were returned by 2,052 eligible respondents (), for a baseline response rate of 16.8%Citation12. Only 479 respondents were deemed ineligible for not having a condition of interest, indicating consistency between the claims and survey data with regard to diagnosis. Baseline 7-day daily diaries were returned by 1,725 respondents. Retention rates remained high throughout the survey observation period, averaging 70.5% (range: 66.9%–74.6%) for monthly surveys, 70.8% (range: 65.2%–74.2%) for quarterly surveys, and 64.8% for the 7-day daily diary at Month 12.

Demographic, treatment, and clinical characteristics

Of the 2,052 CONTOR participants included in the platform, 93.8% were female and mean (SD) age was 46.7 (11.9) years. Most patients (82.6%) identified as white or Caucasian; 11.1% identified as African American (). Only limited demographic data were available for patients who did not respond to the survey; there were no meaningful differences in age between respondents and nonrespondents (mean [SD] 46.5 [12.6] vs 45.7 [12.6], p = .004), but a greater proportion of nonrespondents were male (14.1% vs 6.2%, p < .001) and a greater proportion of respondents were from the Midwest (31.2% vs 23.3%, p < .001).

In general, the patient comorbidity burden calculated from administrative claims data was low; mean Quan-Charlson comorbidity score was 0.3 (). However, the survey data revealed that nearly 25% of participants reported they were diagnosed with IBS-C and/or CIC more than 10 years ago (data not shown), and 92.5% reported experiencing bowel and/or abdominal symptoms for more than 2 years, including 44.4% who had experienced symptoms for more than 10 years. Healthcare provider diagnoses of IBS-C, CIC (including chronic constipation and functional constipation), or IBS were each reported by approximately 41%–44% of patients (). Patients commonly reported that their most bothersome symptoms at baseline were abdominal distension (23.7%), abdominal bloating (21.4%), and infrequent bowel movements (16.9%). The mean (SD) baseline PAC-SYM overall summary score was 1.6 (0.8) out of 4 (), and mean (SD) patient-reported symptom severity from daily diary entries was 3.9 (2.9) for abdominal bloating, 3.6 (3.0) for abdominal distension, 3.6 (2.8) for abdominal discomfort, and 2.9 (2.7) for abdominal pain on a scale of 0–10.

Table 2. Patient sociodemographic and baseline clinical characteristics.

Participants reported trying a variety of treatments to manage their condition prior to completing the baseline survey. Nearly three-fourths of patients reported having been treated for bowel and/or abdominal symptoms for more than 2 years (), yet many of these treatments were not captured in the baseline claims data because they represented OTCs or other remedies.

Health-related quality of life and impact on work and daily activity

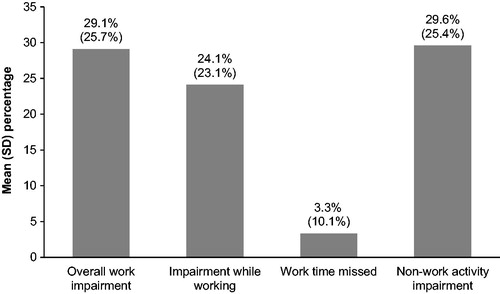

The mean (SD) baseline survey PAC-QOL overall summary score was 2.0 (0.8) on a scale of 0–4, meaning that patients described the impact of their IBS-C or CIC symptoms on their overall quality of life approximately halfway between no impact (summary score of 0) and most severe impact (summary score of 4). Baseline responses to the WPAI:SHP revealed a substantial impact on work productivity and daily activity interpreted as the proportion of time that work or non-work activity is impacted by IBS-C or CIC (). Overall work impairment was due more to presenteeism (impairment while working) than absenteeism (work time missed) ().

Figure 2. Patient-reported impairment of work productivity and non-work activity due to bowel/abdominal symptoms (WPAI:SHP). Data captured from the baseline survey. Of the 2,052 CONTOR participants, 1,591 (78%) responded affirmatively to the WPAI:SHP item regarding working for pay. Abbreviations. SD, standard deviation; WPAI:SHP, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Specific Health Problem.

Treatment patterns

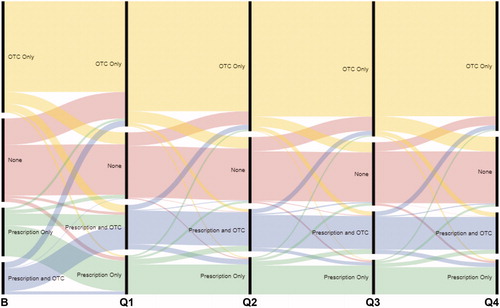

From the baseline survey, the most common treatments patients reported they had ever used to treat their bowel and abdominal symptoms included PEG (78.6%), probiotics (73.3%), psyllium/ispaghula (69.7%), and bisacodyl (68.6%). The treatments most commonly reported as being used in the past 7 days were probiotics, PEG, and linaclotide (). Patient-reported use of treatments was categorized as OTC only, prescription only, prescription and OTC, and none among patients who completed the baseline and all quarterly surveys (n = 1,050). OTC treatments were common, with 65.4% of patients reporting any OTC medication use and 43.3% reporting use of OTCs only. Prescription medication use was less prevalent, with 22.2% and 13.9% of patients reporting OTC/prescription combination regimens and prescription-only regimens, respectively.

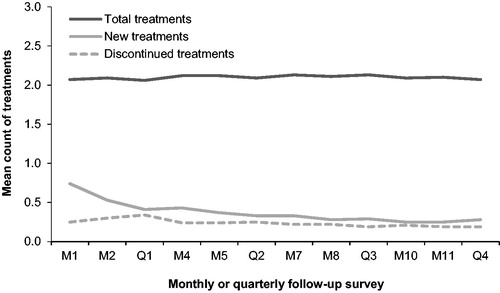

Over the 12 follow-up surveys, the mean number of treatments for bowel and abdominal symptoms reported by CONTOR respondents (including those reporting no treatments) was consistently 2 treatments per month (). Among all patients returning a monthly/quarterly follow-up survey, a low rate of treatment discontinuation was reported (0.19–0.34 treatments per month). The number of treatment category changes reported by patients on the quarterly surveys varied little across the observation period ().

Figure 3. Patient-reported total, new, and discontinued treatments by follow-up survey. Abbreviations. M, month; Q, quarter.

Figure 4. Patient-reported treatment category changes by quarterly follow-up survey. The number of category changes reported is indicated by the width of the transition lines (i.e. a narrower transition line indicates fewer changes). Abbreviations. B, baseline; Q, quarter; OTC, over-the-counter.

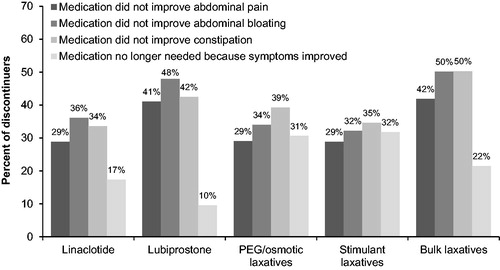

The most common reason for discontinuation (among those who reported using a treatment [non-probiotic]) was lack of constipation relief (41% of patients reporting discontinuation), followed by lack of relief from abdominal bloating (39%) and lack of abdominal pain relief (35%). Patient-reported reasons for discontinuation varied by treatment ().

Figure 5. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuation by treatment. Abbreviations. PEG, polyethylene glycol.

Most respondents who reported using linaclotide or lubiprostone to treat their bowel and abdominal symptoms used these medications daily throughout the study period. Respondents reporting other treatments of interest, such as PEG, reported less frequent use, with fewer than half using these treatments daily.

Treatment satisfaction

More than half of participants (55.3%) indicated they were dissatisfied with management of their condition at baseline; however, satisfaction varied by medication use. Patients reporting no current medication use as part of their treatment regimen (n = 424) had the lowest satisfaction, with 68.4% reporting they were not at all satisfied or a little satisfied. Among patients currently treated with medication, a higher proportion of patients reporting prescription medication use were satisfied with treatment (65.4% of linaclotide users [n = 381] and 57.8% of lubiprostone users [n = 74]). Patients treated with PEG (n = 413), which can be prescribed or purchased as an OTC treatment, or other OTC therapies only (n = 760) were less likely to be satisfied with their treatment (44.5% of PEG users and 40.6% of those using other OTC products only).

Healthcare costs and utilization

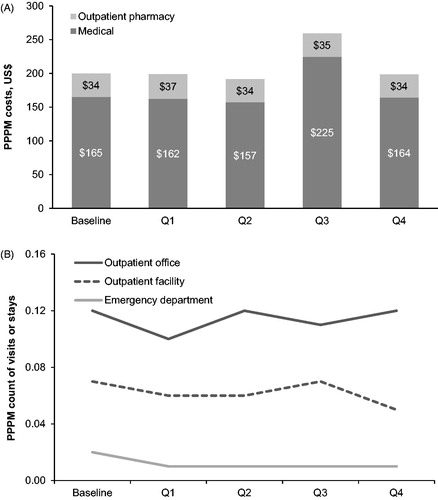

On average, total (medical and pharmacy) all-cause healthcare costs among CONTOR participants across the 18-month observation period were approximately $950 PPPM. Of that, approximately $228 were outpatient pharmacy costs (data not shown). GI-related costs accounted for 20% of all-cause total costs and 15% of all-cause pharmacy costs. GI-related healthcare costs remained largely unchanged over the entire observation period ().

Figure 6. Gastrointestinal-related healthcare resource costs (A) and utilization (B). Per-patient-per-month inpatient utilization was 0.0 across all survey periods (not shown). Abbreviations. PPPM, per patient-per-month; Q, quarter.

Across the observation period, outpatient office visits were the most frequent level of care utilized, with patients averaging 1 all-cause visit per month (data not shown). Outpatient office visits and outpatient facility visits were the most common GI-related health services, but accounted for only a small proportion of all visits (). GI-related healthcare utilization remained consistent over the entire observation period ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, CONTOR is the first research platform of its type for the study of constipation illnesses, collecting a wide range of longitudinal real-world data regarding condition history, treatment experiences, and outcomes among patients with IBS-C and CIC. By combining administrative claims and patient-reported data over time, CONTOR allowed for a deeper understanding of the IBS-C/CIC patient population than could be achieved with claims or survey data alone.

The baseline response rate of 16.8% likely reflects the length and complexity of the baseline survey and diary, as well as the request for a year-long commitment. However, retention rates for study participants were high and remained so throughout the study period, ranging from approximately 65% to 71%. The substantial patient retention achieved in CONTOR not only highlights the success of combining mixed-mode surveys with pre-paid incentives and post-paid payments to engage participants in a longitudinal observational study, but may also illustrate patients’ desire to share their experiences of living with IBS-C and CIC. Patients may find these conditions difficult to discuss; in previous survey-based analyses, feelings of embarrassment and self-consciousness related to IBS-C/CIC were commonly reported, particularly by those with more severe diseaseCitation9,Citation10. CONTOR participants’ sustained commitment to the study suggests they found it important and/or fulfilling to communicate the impact of their symptoms and treatments on their lives. Opportunities such as CONTOR that allow patients to safely share their disease journey may empower them to engage in this type of dialogue with their healthcare providers and help improve the patient experience with treatment for IBS-C/CICCitation9,Citation10.

CONTOR participants reported complex treatment histories with multiple disruptive symptoms occurring over many years; nearly all had experienced and sought treatment for bowel/abdominal symptoms for more than 2 years, with close to half experiencing symptoms for over a decade. These findings align with previous data indicating most patients with IBS-C and CIC report suffering from bothersome constipation-related symptoms on a long-term basisCitation18,Citation19, underscoring the clinical challenges these conditions present to physicians. Our findings also demonstrate patients with IBS-C/CIC have often tried multiple treatments to manage their disease in accordance with treatment guidelinesCitation20,Citation21. The majority of CONTOR participants indicated they had used several classes of treatments at the same time, and also reported using multiple treatments prior to study participation. However, despite having long treatment histories that included a variety of treatment approaches, many patients continued to experience abdominal symptoms and were dissatisfied with the management of their condition.

Treatment dissatisfaction is a common theme in the IBS-C/CIC literature; nearly without exception, studies conducted among patients with these conditions have shown that many suffer persistent abdominal symptoms despite active treatmentCitation9,Citation10,Citation22–24 and most are not satisfied with their treatment regimenCitation9,Citation10,Citation18. For example, only about 35% to 40% of patients with IBS-C and CIC reported satisfaction with their current treatment in 2 recent questionnaire-based studiesCitation9,Citation10. Notably, however, higher proportions of CONTOR patients treated with linaclotide or lubiprostone reported being satisfied with their treatment (about 65% and 58%, respectively), suggesting that patients may benefit from access to these prescription medications. Guidelines for treating IBS-C and CIC generally recommend a shift toward prescription medications if symptom control is not achieved with lifestyle modifications and/or OTC treatmentsCitation23,Citation25–27. Despite this, few patients with IBS-C/CIC are on prescription therapy—only 1 in 3 (36%) CONTOR participants, congruent with the 12% to 35% range found in previous analysesCitation9,Citation10,Citation18—even though many reported persistent burdensome symptoms. Together with findings that prescription medications are associated with higher treatment satisfaction and reduced healthcare resource utilization and costsCitation28–30, our results suggest some IBS-C/CIC patients may benefit from these treatments but do not receive them.

The underutilization of potentially beneficial treatments may indicate a disconnect between patient and provider perception of symptom impact. Although symptom severity scores in the present study were modest, patients reported a considerable negative impact on HRQoL, work performance, and daily activities due to their symptoms, as in previous studiesCitation9,Citation10,Citation18,Citation31–34. The mistaken perception that lower symptom severity, as measured on a validated instrument, necessarily correlates with negligible impact on daily life may limit payer coverage or lead physicians to delay prescribing treatment, which may contribute to ongoing symptoms and reduced treatment satisfaction. Data from CONTOR afford a better understanding of how less-severe but chronic symptoms affect patient wellbeing, which could improve management of IBS-C/CIC, increase patient quality of life, and potentially help reduce the higher healthcare costsCitation5,Citation6,Citation19,Citation35 and healthcare resource utilizationCitation31,Citation33 consistently found among patients with these conditionsCitation28–30.

Lessons learned from CONTOR

The CONTOR platform was successful in building a more holistic view of the IBS-C/CIC patient experience. Our findings include multiple observations that required data from both administrative claims and patient reports; in particular, the longitudinal measures of treatment use provided a robust understanding of real-world day-to-day treatment patterns that would not have been possible without a mixed-mode study—especially for OTC medications, which are not captured in claims data. In addition, claims data alone would not have identified some patients with long-standing symptoms of IBS-C and/or CIC, as specific diagnosis codes were introduced only recently. The survey data helped illustrate that a substantial number of patients had been experiencing symptoms for many years, well before they first received formal medical treatment. Similarly, the paired Quan-Charlson and patient-reported symptom data allowed us to better appreciate that many patients were dissatisfied with their treatment and continued to experience disruptive symptoms despite making few regimen changes, an observation which may otherwise have been interpreted as treatment satisfaction.

There are also some aspects of our approach that could be improved for future analyses. Although CONTOR’s longitudinal design was intended to capture changes in treatments and costs over time, these outcomes remained largely consistent over the observation period. It is possible that the study identification criteria may have inadvertently favored patients whose long-standing condition history resulted in a level of treatment and symptom familiarity that made frequent changes less likely. Furthermore, although patients were identified in 2 waves to achieve a large sample, the unexpectedly widespread use of polytherapy resulted in monotherapy subgroups that were too small to allow meaningful comparative analyses of effectiveness or cost; therefore, this type of design may be better suited for conditions in which complex treatment regimens are less common. Future studies should consider whether less-restrictive sample identification criteria would enhance the longitudinal findings by allowing for greater differentiation over time.

Study limitations

This study utilized both survey and claims data to address limitations associated with reliance on either data source alone. Limitations of survey data may include sampling error (including the existence of bias due to unmeasured differences in characteristics of survey respondents and nonrespondents), coverage error, and measurement error. Limitations of claims data include that the presence of a claim for a filled prescription does not indicate the medication was consumed or taken as prescribed; OTC medications and those provided as samples by a physician cannot be observed; and the presence of a diagnosis code on a medical claim is not proof of disease, as diagnosis codes may also be coded incorrectly or included as rule-out criteria. These limitations were addressed in part by asking participants to report current treatments, including frequency of use, and by collecting patient-reported OTC and prescription medication use as opposed to OTCs purchased or prescriptions filled. Use of diagnosis codes was also complicated by lack of IBS subtypes using ICD-9-CM codes for sample identification. This limitation was mitigated by a variety of approaches, including use of patient-reported health care provider diagnoses and modified Rome III criteria.

Sample identification in a health plan context may have skewed the sample to higher levels of severity than a more general sample of IBS-C/CIC patients since prior authorization may have been required for linaclotide or lubiprostone prescriptions. In addition, results may not be generalizable to uninsured and older populations because this study population was selected from persons with commercial coverage. Finally, our analyses of treatment patterns and satisfaction included treatments available at the time this study was conducted. Several new treatments have been approved since these data were collected.

Conclusion

The CONTOR research platform augments information from clinical trials to provide a deeper understanding of how symptom and treatment history relate to clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes among patients with IBS-C and CIC in a real-world setting. The combination of longitudinal data from administrative claims and patient surveys revealed characteristics that would not have been observable in existing standardized data sources; for example, the complex treatment histories involving use of both prescription and OTC medications that were common in this patient population. Many patients reported experiencing burdensome symptoms and treatment dissatisfaction despite making few treatment changes, highlighting an opportunity for improved patient management. While the CONTOR study was specific to IBS-C and CIC, the patient-centric research platform approach could be leveraged for other conditions in which a single data source fails to fully capture a patient’s real-world experience with illness. Future work should investigate how this approach could be applied to health systems outside the US.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by AbbVie (Madison, NJ) and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Boston, MA).

Declaration of financial/other interests

DCAT is an employee of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and owns stock and stock options. DR is a former employee of Ironwood Pharmaceutical, Inc. and owns stock. JLA and RTC are employees of AbbVie and own stock and stock options. CM, BE, SK, and AGH are employees of Optum (Eden Prairie, MN), which was contracted by AbbVie and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc. to conduct the study and provide medical writing assistance. JAD reports serving as a consultant to AbbVie and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She also reports serving as a consultant and/or advisory board member for Boehringer Ingelheim, Catabasis, Janssen, Kite Pharma, MeiraGTx, Merck, Otsuka, Regeneron, Sarepta, Sage Therapeutics, Sanofi, The Medicines Company, and Vertex, and has received research funding from Abbvie, Biogen, Humana, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, PhRMA, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Valeant, all unrelated to this study.

JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the study, helped analyze and interpret the data, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version for publication, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the CONTOR participants for their long-term commitment to this study and their willingness to share their experiences.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Will Spalding, MS; William Chey, MD; Brennan Spiegel, MD; Paul Buzinec, MS; and Susan Brenneman, PT, PhD to the project concept, design, analyses, and interpretation.

Medical writing assistance was provided by Yvette M. Edmonds, PhD, an employee of Optum.

was created using RAWgraphs (https://rawgraphs.io).Citation36

References

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1393.e5–1407.e5.

- Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, et al. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterology. 2002;97(8):1986–1993.

- Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, et al. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Suppl):S17–S26.

- Ballou S, McMahon C, Lee HN, et al. Effects of irritable bowel syndrome on daily activities vary among subtypes based on results from the IBS in America survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2471.e3–2478.e3.

- Doshi JA, Cai Q, Buono JL, et al. Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a retrospective analysis of health care costs in a commercially insured population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(4):382–390.

- Cai Q, Buono JL, Spalding WM, et al. Healthcare costs among patients with chronic constipation: a retrospective claims analysis in a commercially insured population. J Med Econ. 2014;17(2):148–158.

- Reilly MC, Bracco A, Ricci JF, et al. The validity and accuracy of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire–Irritable Bowel Syndrome version (WPAI:IBS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(4):459–467.

- Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, et al. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(5):461–476.

- Quigley EMM, Horn J, Kissous-Hunt M, et al. Better Understanding and Recognition of the Disconnects, Experiences, and Needs of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation (BURDEN IBS-C) study: results of an online questionnaire. Adv Ther. 2018;35(7):967–980.

- Harris LA, Horn J, Kissous-Hunt M, et al. The Better Understanding and Recognition of the Disconnects, Experiences, and Needs of Patients with Chronic Idiopathic Constipation (BURDEN-CIC) study: results of an online questionnaire. Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2661–2673.

- Johnson CL, Dohmann SM, Burt VL, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2:162.

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 9th ed. 2016 [Accessed 2019 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf.

- Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870–877.

- Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, et al. Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540–551.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index. Medical care; 2014 [Accessed 2017]. Available from https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm.

- Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(5):599–608.

- Herrick LM, Spalding WM, Saito YA, et al. A case-control comparison of direct healthcare-provider medical costs of chronic idiopathic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation in a community-based cohort. J Med Econ. 2017;20(3):273–279.

- Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313(9):949–958.

- McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H, et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29(5):549–575.

- Sonu I, Triadafilopoulos G, Gardner JD. Persistent constipation and abdominal adverse events with newer treatments for constipation. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000094

- McCormick D. Managing costs and care for chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(4 Suppl):S63–S69.

- Guerin A, Carson RT, Lewis B, et al. The economic burden of treatment failure amongst patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic constipation: a retrospective analysis of a Medicaid population. J Med Econ. 2014;17(8):577–586.

- Cash BD. Understanding and managing IBS and CIC in the primary care setting. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14(5 Suppl 3):3–15.

- Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):211–217.

- Tse Y, Armstrong D, Andrews CN, et al. Treatment algorithm for chronic idiopathic constipation and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome derived from a Canadian national survey and needs assessment on choices of therapeutic agents. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:8612189.

- Buono JL, Tourkodimitris S, Sarocco P, et al. Impact of linaclotide treatment on work productivity and activity impairment in adults with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: results from 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(5):289–297.

- Solem CT, Patel H, Mehta S, et al. Treatment patterns, symptom reduction, quality of life, and resource use associated with lubiprostone in irritable bowel syndrome constipation subtype. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(5):899–905.

- Taylor DC, Abel JL, Bancroft T, et al. Health care resource use and costs pre- and post-treatment initiation with linaclotide: Retrospective analyses of a U.S. insured population. Manag Care. 2018;27(2):33–40.

- DiBonaventura M, Sun SX, Bolge SC, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity and health care resource use associated with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(11):2213–2222.

- Heidelbaugh JJ, Stelwagon M, Miller SA, et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(4):580–587.

- Sun SX, Dibonaventura M, Purayidathil FW, et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(9):2688–2695.

- Stephenson JJ, Buono JL, Spalding WM, et al. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation on work productivity and daily activity among commercially insured patients in the United States. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A370.

- Mitra D, Davis KL, Baran RW. All-cause health care charges among managed care patients with constipation and comorbid irritable bowel syndrome. Postgrad Med. 2011;123(3):122–132.

- Mauri M, Elli T, Caviglia G, et al. RAWGraphs: a visualisation platform to create open outputs. Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter. Vol 28. New York, NY: ACM; 2017. p. 1–5.