Abstract

In recent years, a vast quantity of clinical data has been accumulated on the pathophysiology of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)/genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in peri- and postmenopausal women and on the treatment options for these conditions. Guidelines from several societies have recently been updated in favor of VVA/GSM vaginal therapy with the lowest possible doses of estrogens. The combination of a vaginal ultra-low dose of 0.03 mg of estriol (E3) and lyophilized, viable Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400 (0.03 mg-E3/L) is a unique product with a dual mechanism of action supporting not only the proliferation and maturation of the vaginal epithelium, but also restoration of the lactobacillary microflora. It has been demonstrated efficiently to establish and maintain a healthy vaginal ecosystem. Use of this combination considerably improves the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the quality of life of menopausal women suffering from vaginal atrophy. This combination therapy is well tolerated with a low overall incidence of side-effects and negligible estriol absorption. Based on recent scientific evidence and current treatment guidelines, the 0.03 mg-E3/L combination could be considered one of the options for the treatment of symptomatic vaginal atrophy in aging menopausal women.

Introduction

In recent years, a vast quantity of clinical data has been accumulated on vaginal atrophy issues. According to the International Menopause Society (IMS), up to 40% of postmenopausal women will experience urogenital atrophyCitation1. However, only 25% of symptomatic women are actively seeking treatment, and 70% report that their physician rarely asks about vaginal symptomsCitation1.

Various terms have been traditionally used to describe this medical condition: vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), urogenital atrophy, (symptomatic) vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis, etc. New terminology was recently proposed by American scientific societies (the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health) to describe the complexity of typical urogenital signs and symptoms, namely genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)Citation2,Citation3.

The current treatment options for VVA/GSM such as the use of low-dose estrogen or an ultra-low dose of estriol (E3), with or without lactobacilli combination, have been describedCitation4. The aim of this article is to review available scientific knowledge on the use of ultra-low-dose estriol (0.03 mg-E3) and Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400 (L) combination (0.03 mg-E3/L) and to provide state-of-the-art evidence for clinicians facing urogenital atrophy problems in aging women.

Vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause

Pathophysiology overview

For the normal functioning of the balanced vaginal ecosystem, sufficient estrogen levels leading to an intact vaginal epithelium as well as healthy microflora (vaginal microbiome) are essentialCitation1,Citation5,Citation6. The immune response also influences this ecosystemCitation7.

The defensive vaginal lactobacillary flora is in a dynamic state. The abundance and bacterial type composition can change rapidlyCitation6. Beneficial lactobacilli produce various antibacterial compoundsCitation5, can compete with pathogens for adherence (competitive exclusion), and interact with the local immune mechanisms in the vagina. Interestingly, estrogen levels also play a crucial role in maintaining lactobacilli-dominated floraCitation8.

Another basic element in the micro-ecology of the vagina is the stratified, squamous non-keratinized vaginal epithelium consisting of basal, parabasal, intermediate and superficial cell layers. The female sex hormones regulate the development and functioning of sex organs, supporting and maintaining vaginal elasticity and lubrication in particular. Thus, the development of the epithelium is related to circulating estrogen levels and varies depending on physiological conditions. Due to the high affinity of estrogen molecules for estrogen receptors (ERs), only a low dose of hormone is needed to generate sufficient effectCitation9. A vaginal epithelium stimulated by estrogen is a prerequisite for establishing and maintaining physiological floraCitation10,Citation11. The breakdown of proliferated superficial cells liberates glycogen, which serves as a substrate for the lactobacilliCitation12.

Urogenital atrophy is characterized by the changes in the urogenital tract due to a marked decrease in ovarian estrogen productionCitation10. Serum estrogen levels normally range from 40 to 400 pg/ml in premenopausal women, decreasing to less than 20 pg/ml during the postmenopausal periodCitation13. The usual underlying cause of estrogen deficiency is natural menopause, but this can also be triggered by lactation and premature ovarian insufficiency (POI). Interventions that indirectly reduce ovarian function, such as radiotherapy or tamoxifen therapy, may also cause atrophy. Heavy smokers might also be affectedCitation14,Citation15. The change in circulating estrogen levels is reflected in changes in vaginal physiology and symptoms, resulting in decreased barrier and lubrication functions of the epithelium, lower vaginal glycogen content, the presence of lactobacilli and increased penetration by pathogens, often culminating in atrophic vaginitisCitation1,Citation16.

Diagnostic considerations

Women are generally unaware of the fact that VVA can have a significant impact on sexual health or that effective and safe treatments are availableCitation17,Citation18. Society’s taboos, cultural background and misconceptions, etc. aggravate this situation. Hence, there is a medical need to provide reliable information on vaginal atrophy issuesCitation17.

The clinical picture, general menopausal signs, and gynecological examination are essential for diagnosis. The genitourinary syndrome may include, but is not necessarily limited to, genital symptoms of dryness, burning and irritation, sexual symptoms such as insufficient lubrication, pain during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia), urinary symptoms and recurrent urinary infectionsCitation2,Citation10,Citation14. Such atrophic effects usually become clinically apparent 4–5 years after the menopause, and vaginal atrophy is present in 25–50% of all postmenopausal womenCitation1.

Objective findings of vaginal atrophy include reduced epithelial thickness, epithelial pallor, shortening of the vagina, reduced elasticity of vaginal walls, reduction of the vaginal diameter, reduction of pubic hair, shrinkage of the labia, increased vaginal pH up to 6–7, and loss of vaginal mucosal folds (rugae)Citation2,Citation10,Citation14. The main symptoms are vaginal dryness (estimated at 75%), dyspareunia, vaginal itching as well as vaginal discharge and sorenessCitation2,Citation10,Citation14. Moreover, female urethral function may also deteriorate and urinary symptoms, such as incontinence and frequent urinary tract infections, are commonly observedCitation1,Citation14.

Although VVA is typically a clinical diagnosis, laboratory tests may support the findings. Low vaginal epithelium maturation, atrophic smears with or without inflammation, a vaginal pH of more than 5.0 and decreased serum estrogen levels confirm the diagnosis. A decreased vaginal maturation index (VMI) or value describes the cytological changes in vaginal smears as a shift from superficial squamous cells towards intermediate epithelial cellsCitation19. In healthy women, VMI is within the 50–64% range and shows moderate estrogenic stimulation whilst a VMI value below 49% is indicative of vaginal atrophyCitation10,Citation19. However, no consensus on optimal VMI calculation has been reached to dateCitation19.

Impact on quality of life

Estrogen loss affects different sexual domains leading to a negative impact on quality of life which is especially problematic for women who want to stay sexually activeCitation14,Citation20. Typical problems are significant increase in vaginal dryness, decrease in sexual desire, arousal, orgasm and dyspareuniaCitation17. The loss of sexual function leads to a redefinition of the feminine role of women as it affects all domains of quality of life, like self-esteem, including their social life and relationship with their partnerCitation17,Citation21.

Treatment with the combination of estriol and lactobacilli

Treatment principles

Vaginal atrophy is a progressive condition, but a positive vaginal response to therapy is rapid and sustainedCitation22. The IMS recommends using an ultra-low dose of vaginal estrogen, although long-term safety clinical data (more than 1 year) are still limitedCitation1,Citation23. A consensus on menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) stresses that local, low-dose estrogen therapy should be preferred in women with isolated vaginal dryness and/or associated dyspareuniaCitation24. The recommendation is to administer the lowest local dose estrogen therapy in case long-term treatment is requiredCitation1,Citation23. There is no documented evidence of clinically relevant endometrial effects if ultra-low-dose vaginal estrogen, especially E3, therapy is used. Nevertheless, before initiating the therapy, it is recommended to exclude endometrial pathology. Furthermore, other guidelines by scientific societies such as NAMS, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the European Menopause and Andropause Society, and German S3 are in line with the aforementioned approachCitation25–29.

Non-hormonal substances

If hormones are unsuitable, vaginal lubricants or moisturizers could provide improved lubrication. It has been reported that oral phytoestrogens do not alleviate menopausal symptoms in breast cancer patientsCitation30. In general, non-hormonal substances could provide temporary symptom relief but their long-term efficacy is very limitedCitation1,Citation23,Citation28.

DHEA and SERMs

Promising, novel menopause therapies such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are currently recommended by the IMS for the treatment of VVA/GSMCitation23. Topical use of DHEA is promising in the treatment of VVA, especially in the case of associated sexual symptoms in women with contraindications to estrogensCitation23. Ospemifene, a novel SERM, is indicated for the systemic oral treatment of dyspareunia associated with VVA in women who are unable to take vaginal estrogensCitation23,Citation31.

Estrogens

Due to the high concentration of estrogen receptors (ER – both ERα and ERβ) in the vulva and vagina as well as in the pelvic floor and urethral muscles, the bladder trigon is highly sensitive to estrogen deprivationCitation32,Citation33. Hence, vaginal atrophy can effectively be treated with estrogens, including locally applied estrogensCitation1,Citation34. Few studies have shown a correlation between the use of vaginal estrogens and a stimulating effect on the endometrium (development of endometrial atypical hyperplasia). However, only continuous vaginal use of high doses of ‘potent’ estrogens (like estradiol, E2) may have safety concerns as this effect is known to depend on hormone type, dose and frequency of administrationCitation35.

Vaginally administered estrogens are absorbed in a dose-dependent mannerCitation36,Citation37. Vaginal estrogens are more effective in relieving urogenital symptoms than oral preparations because lower doses are required due to the absence of hepatic metabolism and high local estrogen concentrationsCitation35,Citation38. The use of local estrogen is the option of choice – it provides an effective and safe treatment that improves symptoms and restores women’s quality of lifeCitation20. In severe cases, women receiving systemic hormone therapy may require an additional vaginal estrogen as systemic therapy alone relieves vaginal atrophy symptoms in only about 75% of womenCitation39.

Estriol

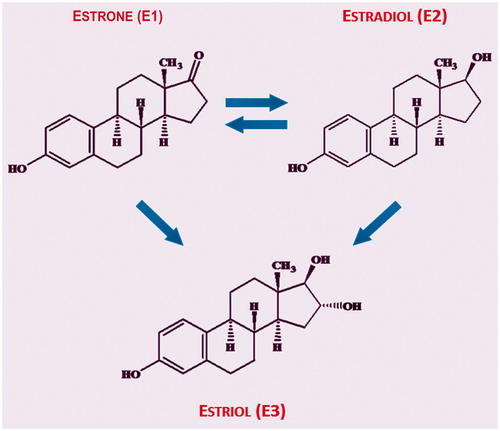

Estriol (E3) is a human-specific sex hormone. In addition to E3, two other estrogen hormones, namely estradiol (E2) and estrone (E1), are naturally present in humansCitation35. Whereas E2 and E1 can be reversibly metabolized into each other, E3 is a final metabolite of estrogen synthesisCitation40,Citation41. E3 has been defined as a short-acting estrogen, since it has the shortest receptor occupancy and lowest receptor affinity of all estrogens – about 10 times weaker than E2Citation35. Thus, some estrogenic effects, so-called ‘early effects’, can be observed following single administration of E3, whereas ‘late effects’, which are based on a longer receptor retention time, are seen only with E2Citation40,Citation42. In addition, rapid ER signaling seems to be important if E2 is usedCitation43.

The endogenous daily production of E3 during the premenopause, calculated from the metabolic clearance rate and plasma concentration, is known to range around 14 ± 2 µg/day in the follicular phase and 23 ± 2 µg/day in the luteal phase. During the postmenopause, the mean value is 11 ± 4 µg/dayCitation36,Citation44–49. In serum, 8% of E3 is unbound and 92% is bound to transport proteinsCitation50. The elimination half-life of E3 ranges from 9 to 10 h47. More than 95% of E3 is eliminated via the urine in the form of glucuronidesCitation50.

After oral administration, E3 is readily absorbed and metabolized in the liver, so that only 1–2% of the administered dose reach the circulation in an unchanged active form. Following administration of 8 mg of E3, a maximum serum level of 75–220 pg/ml is reached after 1–3 hoursCitation36,Citation50. Following vaginal application, about 20% of the dose reaches the circulation in an unchanged form. Correspondingly, similar systemic effects are produced by vaginal treatment compared to oral therapy with a 10–20-fold higher doseCitation40,Citation50. Vaginal absorption of estrogen depends on the maturation status of the epithelium: E3 absorption via a well-proliferated vaginal epithelium is markedly lower than that via an atrophic oneCitation47,Citation51–53. Various authors have also concluded that repeated intravaginal administration of E3 leads to a slight cumulative effectCitation37,Citation47. However, doses as high as 0.5 mg E3 twice weekly are not associated with a significant increase in serum estrogen levels after short- (weeks) and long-term (12 months) treatmentsCitation54.

After single-dose, oral or vaginal applications of E3 in conventional doses (oral: ≤ 8–10 mg; vaginal: ≤ 0.5 mg), there is no or only a weak proliferative effect on the endometriumCitation41,Citation42. The lack of or weak stimulation of the endometrium by E3 can be explained by its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic propertiesCitation41. The mechanism of action in the vagina and uterus is similar with E3 and E255 but differs in terms of a 10-fold lower affinity of the ER for E3 versus E2Citation33,Citation55.

Like all estrogens, E3 stimulates the proliferation and maturation of the vaginal epithelium but no clear differences in E3 receptor affinity have been found between the vagina and the endometriumCitation35,Citation55. The comprehensive review of clinical studies investigating E3 has shown that intravaginal E3 appears to be effective in controlling local symptoms of menopause with a vaginal dose of 0.5 mg E3Citation35. A meta-analysis of all published studies concluded that once-daily treatment with intravaginal E3 (0.5 mg) is safe and has no increased risk of endometrial proliferation or hyperplasiaCitation56.

Ultra-low-dose vaginal estriol (0.03 mg E3) has a beneficial efficacy-safety profileCitation1,Citation34,Citation49,Citation47,Citation57–62: (1) it displays similar efficacy to that of conventional dose (0.5 mg) preparations; (2) it does not increase systemic E2 and/or E1 levels, while its influence on systemic E3 levels depends on the dose and maturation status of the epithelium; (3) it shows no relevant influence on systemic levels of sex hormones; (4) it does not cause endometrial proliferation after 6 months of use and, accordingly, there is no need to use opposing progestogen; and finally, (5) no systemic adverse events are expected due to negligible absorption. Hence, as mentioned, topical administration of low-dose E3 is generally preferredCitation35.

Lactobacilli

For over a century, lactobacillary flora has been believed to maintain vaginal homeostasis, and any imbalance has potentially been associated with poor gynecological health outcomes.

Only probiotic Lactobacillus strains exhibit beneficial propertiesCitation63. Beneficial lactobacilli inhibit the growth of pathogens by producing various antimicrobial substancesCitation63. In vitro experiments with L. acidophilus have demonstrated that the strain is able to produce substantial amounts of lactic acidCitation64. Another important defense mechanismCitation12,Citation63,Citation65 of beneficial lactobacilli strains involves the production of H2O2. Additional defense mechanisms such as the production of bacteriocins and biosurfactants, co-aggregation and lactobacilli biofilm formation have also been describedCitation8. Furthermore, beneficial lactobacilli strains compete with pathogens for adherence to the vaginal epithelium and for nutrientsCitation63,Citation66. Probiotics also show immune-modulating propertiesCitation7,Citation63 – vaginal lactobacilli properly calibrate genital immune system responses via specific signaling processesCitation67,Citation68.

Postmenopausal women with diminished estrogen levels have quite different vaginal flora compared to premenopausal women. The abundance of lactobacilli is substantially decreased, and women with vaginal atrophy display increased vaginal bacterial diversityCitation59,Citation69,Citation70. The estrogen therapy of VVA in postmenopausal women results in a vaginal epithelium resembling the premenopausal periodCitation59 and beneficial lactobacilli flora are important for preventing vaginal infections. Concomitant treatment with probiotic lactobacilli is therefore considered as adjuvant therapy to restore the beneficial lactobacilli flora in these postmenopausal womenCitation4. The efficacy of exogenous lactobacilli for the restoration of the vaginal flora in premenopausal women having received anti-infective therapy is well documentedCitation66,Citation71. Furthermore, evidence of the synergistic effect of combined estriol–lactobacilli treatment in postmenopausal women has been shown in a clinical study investigating the improvement of urogenital agingCitation59.

Ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli combination

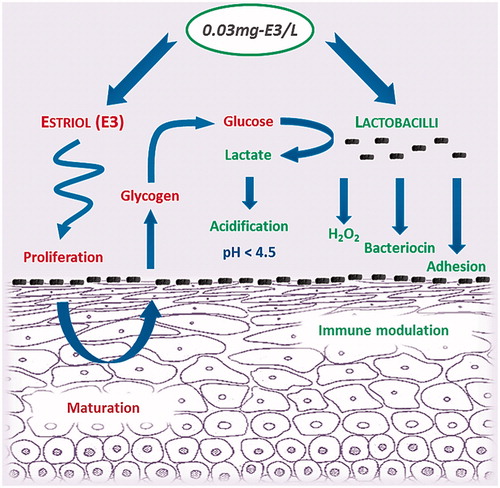

A combination containing a very low dose of E3 (0.03 mg) and lyophilized, 100 million cfu (colony forming units) viable Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400 per vaginal tablet (0.03 mg-E3/L) has also been used in clinical studies to treat VVA and is approved in many countries. Its dual mechanism of action has been used for many years for conditions where the establishment and maintenance of a healthy vaginal ecosystem is important ()Citation66, such as restoration of the vaginal flora, treatment of vaginal discharge and treatment of symptomatic vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. The dosage and duration of the estriol and lactobacilli combination depend on the clinical situation. The general rule in the treatment of vaginal atrophy is a single daily application for 12 days as initial therapy followed by a maintenance regimen of two to three doses per weekCitation66.

Figure 1. Dual mechanism of action of 0.03 mg estriol/Lactobacillus acidophilus (0.03 mg-E3/L) combinationCitation5,Citation7,Citation66.

The dose of E3 in 0.03 mg-E3/L combination therapy is substantially lower than that of conventional preparations. As stated earlier, topical E3 as the final metabolite of estrogen synthesis () is preferred for vaginal use in that it generates a sufficient local response without having a relevant effect on the endometriumCitation1.

Figure 2. Transformation of various estrogen typesCitation40,Citation41.

The Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400 strain contained in 0.03 mg-E3/L is of human origin and has been shown to possess the essential, beneficial in vitro properties for vaginal useCitation66.

In a pharmacokinetic study, Kaiser and colleaguesCitation72 demonstrated that basal plasma concentrations of unconjugated E3 during the 12-day treatment regimen with 0.03 mg-E3/L combination remained at the same level, indicating that no accumulation of E3 had taken place and that systemic effects were therefore unlikely. In contrast to the standard dose of 0.5 mg E3, 0.03 mg-E3/L combination neither produces significant absorption nor triggers a relevant increase in systemic E3 levels. Thus it is predominantly effective in the vagina with negligible systemic actionCitation73. Another pharmacokinetic clinical study carried out by Donders and colleaguesCitation53 in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors – the population with the lowest possible estrogen serum levels – suffering from severe symptomatic vaginal atrophy, clearly demonstrated that single vaginal application of 0.03 mg-E3/L generates only a small and transient rise in serum E3 levels (up to 44 pg/ml) in 50% of women at the start of treatment. However, serum levels of other sex hormones and binding proteins are not influenced at all. After repeated daily intravaginal application of the combination, E3 absorption could no longer be detected, presumably because of increased local metabolism by the matured epithelial maturation. Consequently, this treatment can be evaluated as being safe without any relevant risk of endometrial or other systemic effects and may be considered for breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitorsCitation53,Citation74.

Interestingly, combining E3 with lactobacilli has demonstrated synergistic effectsCitation59. A clinical study by Capobianco and colleaguesCitation59 demonstrated that 0.03 mg-E3/L combination was considerably more effective in reducing urogenital atrophy, the frequency of urinary tract infections and stress urinary incontinence compared to a 1 mg-E3 mono-preparation. The authors recommended this combination therapy as first-line treatment for urogenital aging in postmenopausal womenCitation59.

Overall, the clinical efficacy of 0.03 mg-E3/L combination in the treatment of vaginal atrophy has been demonstrated in various clinical studies ()Citation16,Citation53,Citation59,Citation61,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75–77. More than 600 women have been evaluated. Clinical data revealed that vaginal 0.03 mg-E3/L leads to similar efficacy compared to the 16-fold higher dose of 0.5 mgCitation73. Furthermore, the equivalent efficacy of ultra-low-dose E3 in the treatment of vaginal atrophy has been also demonstrated in clinical studies using E3 mono-preparationsCitation57,Citation58,Citation60. Recent clinical studies have highlighted the considerable efficacy of 0.03 mg-E3/L combination in treatment of VVA/GSM in various ways. Both initial (daily vaginal application for 2 weeks) and maintenance (two or three vaginal tablets weekly) therapeutic regimens have been studied and proved to be effective in treating and preventing the relapse of vaginal atrophyCitation53,Citation59,Citation61,Citation75,Citation76. Relevant improvements in signs and symptoms such as vaginal dryness, soreness and dyspareunia, in affected women have been demonstrated compared to placeboCitation61 and comparatorsCitation59. In a pivotal study, Jaisamrarn and colleaguesCitation61 demonstrated the superiority of 0.03 mg-E3/L combination over placebo, with a significantly higher increase in VMI. During initial treatment, VMI increased considerably from the start of treatment to the first follow-up (after 2 weeks of initial therapy) and remained within the normal estrogenization range (> 50%) during 2 months of maintenance therapyCitation53,Citation61. Interestingly, maximum E3 levels were inversely correlated with VMI values, demonstrating that the maturing epithelium rapidly precludes further E3 absorption after initial therapyCitation53. Additional flora parameters have also demonstrated positive dynamics in a consistent mannerCitation61,Citation76. The lactobacillary grade permanently improved from onset through to the end of initial therapy, and even during maintenance therapyCitation53,Citation61. In addition, the improvement in signs and symptoms was accompanied by positive effects on sexual and overall quality of lifeCitation75.

Table 1. Overview of main publications with 0.03 mg estriol (E3)–Lactobacillus acidophilus KS400 combination (0.03 mg-E3/L) relating to the treatment of vaginal atrophy.

Safety of ultra-low-dose estriol combined with lactobacilli

The safety of 0.03 mg-E3/L combination has been evaluated in more than 4000 women in various clinical studies, and only 1.7% adverse drug reactions were observed. Most of the side-effects (> 80%) were local reactionsCitation66. There was no evidence of typical side-effects of systemic estrogen treatment such as thromboembolic events, in women who were taking 0.03 mg-E3/L vaginal tabletsCitation1,Citation66. Moreover, probiotic lactobacilli are known to be very well toleratedCitation78.

Panay and FentonCitation79 clarified the confusion surrounding key safety issues relating to the use of local vaginal estrogen therapy: (1) concomitant progestogen application is not required because ultra-low-dose estrogens are unlikely to stimulate the endometrium; (2) the overall duration of treatment is usually not limited; and (3) the use of vaginal estrogens is often necessary even during systemic hormone therapy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the use of ultra-low-dose 0.03 mg E3 in combination with lactobacilli (0.03 mg-E3/L) for the treatment of VVA/GSM represents a modern medical concept. Both sufficient estrogen levels and colonization by lactobacilli are essential to restore and maintain a healthy vaginal ecosystem. An ultra-low-dosed E3, with no risk of endometrial proliferation, stimulates the vaginal epithelium and supports the development of physiological flora. Probiotic lactobacilli work through a variety of mechanisms to reinstate homeostasis by commensal colonization, blocking adhesion of pathogens, enhancing epithelial barrier function and influencing antimicrobial peptide secretion and the mucosal immunity of the human vagina. Hence, the 0.03 mg-E3/L combination displays synergistic action and considerably improves the clinical signs and symptoms as well as the quality of life of women suffering from vaginal atrophy. This combination therapy is well tolerated with a low overall incidence of side-effects and negligible E3 absorption. Based on recent scientific evidence and current treatment guidelines, 0.03 mg-E3/L combination could be considered one of the options for the treatment of symptomatic vaginal atrophy in aging menopausal women.

Conflict of interest

Dr Philipp Grob and Dr Valdas Prasauskas are employees of Medinova AG, Switzerland. Other authors over the past 2 years have had no conflict of interest in relation to this publication. The authors are solely responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gabriela Zwyssig, Medinova AG, Switzerland, and Dr Christian Rosé, Pierre Fabre, Germany, for their comments on the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2010;13:509–22

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the international society for the study of women’s sexual health and the North American menopause society. Climacteric 2014;17:557–63

- Panay N. Genitourinary syndrome of the menopause – dawn of a new era? Climacteric 2015;18(Suppl 1):13–17

- Muhleisen AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Menopause and the vaginal microbiome. Maturitas 2016;91:42–50

- Lamont R, Sobel J, Akins R, et al. The vaginal microbiome: new information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques. Bjog 2011;118:533–49

- Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, et al. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:132ra52

- Witkin SS, Linhares IM, Giraldo P, et al. An altered immunity hypothesis for the development of symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:554–7

- Wilson JD, Lee RA, Balen AH, et al. Bacterial vaginal flora in relation to changing oestrogen levels. Int J STD AIDS 2007;18:308–11

- Wierman ME. Sex steroid effects at target tissues: mechanisms of action. Adv Physiol Educ 2007;31:26–33

- MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:87–94

- McGroarty JA. Probiotic use of lactobacilli in the human female urogenital tract. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1993;6:251–64

- Redondo-Lopez V, Cook RL, Sobel JD. Emerging role of lactobacilli in the control and maintenance of the vaginal bacterial microflora. Rev Infect Dis 1990;12:856–72

- Archer DF. Efficacy and tolerability of local estrogen therapy for urogenital atrophy. Menopause 2010;17:194–203

- Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS. Diagnosis and treatment of atrophic vaginitis. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:3090–6

- Ruan X, Mueck AO. Impact of smoking on estrogenic efficacy. Climacteric 2015;18:38–46

- Kanne B, Jenny J. [Local administration of low-dosed estriol and viable Lactobacillus acidophilus in the post-menopausal period]. Gynäkol Rundsch 1991;31:7–13 [German]

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric 2014;17:3–9

- Krychman M, Graham S, Bernick B, et al. The Women’s EMPOWER survey: women’s knowledge and awareness of treatment options for vulvar and vaginal atrophy remains inadequate. J Sex Med 2017;14:425–33

- Weber MA, Limpens J, Roovers JP. Assessment of vaginal atrophy: a review. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26:15–28

- Simon JA. Identifying and treating sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women: the role of estrogen. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:1453–65

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 2010;67:233–8

- Weber MA, Kleijn MH, Langendam M, et al. Local oestrogen for pelvic floor disorders: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136265

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A, et al. 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric 2016;19:109–50

- de Villiers TJ, Gass ML, Haines CJ, et al. Global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 2013;16:203–4

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2013;20:888–902

- Lumsden MA, Davies M, Sarri G, et al. Diagnosis and management of menopause: the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1205–6

- Neves-e-Castro M, Birkhauser M, Samsioe G, et al. EMAS position statement: the ten point guide to the integral management of menopausal health. Maturitas 2015;81:88–92

- Ortmann O, Lattrich C. The treatment of climacteric symptoms. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012;109:316–23

- Ortmann O, Doren M, Windler E, et al. Hormone therapy in perimenopause and postmenopause (HT). Interdisciplinary S3 guideline, association of the scientific medical societies in Germany AWMF 015/062-short version. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:343–55

- Nikander E, Kilkkinen A, Metsa-Heikkila M, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial with phytoestrogens in treatment of menopause in breast cancer patients. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:1213–20

- Bruyniks N, Biglia N, Palacios S, et al. Systematic indirect comparison of ospemifene versus local estrogens for vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2017;20:195–204

- Iosif CS. Effects of protracted administration of estriol on the lower genito urinary tract in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 1992;251:115–20

- Palacios S. Advances in hormone replacement therapy: making the menopause manageable. BMC Womens Health 2008;8:22

- Suckling JA, Kennedy R, Lethaby A, et al. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:1–103; Art. No.:CD001500

- Head KA. Estriol: safety and efficacy. Altern Med Rev 1998;3:101–13

- Englund DE, Elamsson KB, Johansson EDB. Bioavailability of oestriol. Acta Endocrinol 1982;99:136–40

- Keller PJ, Riedmann R, Fischer M. [Oestrone, oestradiol and oestriol content following intravaginal application of oestriol in the postmenopause]. Gynäkol Rundsch 1980;20:77–9 [German]

- Trinkaus M, Chin S, Wolfman W, et al. Should urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors be treated with topical estrogens? Oncologist 2008;13:222–31

- Palacios S, Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, et al. Low-dose, vaginally administered estrogens may enhance local benefits of systemic therapy in the treatment of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women on hormone therapy. Maturitas 2005;50:98–104

- Heimer GM, Englund DE. Plasma oestriol following vaginal administration: morning versus evening insertion and influence of food. Maturitas 1986;8:239–43

- van der Vies J. The pharmacology of oestriol. Maturitas 1982;4:291–9

- Bergink EW. Oestriol receptor interactions: their biological importance and therapeutic implications. Acta Endocrinol 1980;(Suppl 233):9–16

- Lokuge S, Frey BN, Foster JA, et al. The rapid effects of estrogen: a mini-review. Behav Pharmacol 2010;21:465–72

- Longcope C. Estriol production and metabolism in normal women. J Steroid Biochem 1984;20:959–62

- Fink RS, Collins WP, Papadaki L, et al. Vaginal oestriol: effective menopausal therapy not associated with endometrial hyperplasia. J Gynaecol Endocrinol 1985;I:1–11

- Genazzani AR, Inaudi P, la Rosa R, et al. Oestriol and the menopause: clinical and endocrinological results of vaginal administration. In: Fioretti P, Martini L, Melis GB, et al., editors. The menopause: clinical, endocrinological and pathophysiological aspects. Serono Symposium No. 39. London (New York): Academic Press; 1982:539–50

- Mattsson L-A, Cullberg G. Vaginal absorption of two estriol preparations: a comparative study in post-menopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1983;62:393–6

- Rauramo L, Punnonen R, Grönroos M. Serum oestrone, oestradiol and oestriol concentrations during oral oestradiol valerate and oestriol succinate therapy in ovariectomized women. Maturitas 1978;1:79–85

- van Haaften M, Donker GH, Haspels AA, et al. Oestrogen concentrations in plasma, endometrium, myometrium and vagina of postmenopausal women, and effects of vaginal oestriol (E3) and oestradiol (E2) applications. J Steroid Biochem 1989;33:647–53

- Bundesgesundheitsamt (BGA), Kommission B4. [B. Processing Monograph Estriol]. Daz 1993;133:858 [German]

- Furuhjelm M, Karlgren E, Carlström K. Intravaginal administration of conjugated estrogens in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1980;17:335–9

- Samsioe G. Urogenital aging–a hidden problem. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:S245–9

- Donders G, Neven P, Moegele M, et al. Ultra-low-dose estriol and Lactobacillus acidophilus vaginal tablets (Gynoflor(®)) for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors: pharmacokinetic, safety, and efficacy phase I clinical study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;145:371–9

- Ponzone R, Biglia N, Jacomuzzi ME, et al. Vaginal oestrogen therapy after breast cancer: is it safe? Eur J Cancer 2005;41:2673–81

- van Haaften M, Donker GH, Sie-Go DM, et al. Biochemical and histological effects of vaginal estriol and estradiol applications on the endometrium, myometrium and vagina of postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol 1997;11:175–85

- Vooijs GP, Geurts TBP. Review of the endometrial safety during intravaginal treatment with estriol. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 1995;62:101–6

- Buhling KJ, Eydeler U, Borregaard S, et al. Systemic bioavailability of estriol following single and repeated vaginal administration of 0.03 mg estriol containing pessaries. Arzneimittelforschung 2012;62:378–83

- Cano A, Estevez J, Usandizaga R, et al. The therapeutic effect of a new ultra low concentration estriol gel formulation (0.005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from a Pivotal Phase III Study. Menopause 2012;19:1130–9

- Capobianco G, Wenger JM, Meloni GB, et al. Triple therapy with Lactobacilli acidophili, estriol plus pelvic floor rehabilitation for symptoms of urogenital aging in postmenopausal women. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:601–8

- Griesser H, Skonietzki S, Fischer T, et al. Low dose estriol pessaries for the treatment of vaginal atrophy: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy of pessaries containing 0.2mg and 0.03mg estriol. Maturitas 2012;71:360–8

- Jaisamrarn U, Triratanachat S, Chaikittisilpa S, et al. Ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli in the local treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: a double-blind randomized trial followed by open-label maintenance therapy. Climacteric 2013;16:347–55

- Caruso S, Cianci S, Amore FF, et al. Quality of life and sexual function of naturally postmenopausal women on an ultralow-concentration estriol vaginal gel. Menopause 2016;23:47–54

- Barbes C, Boris S. Potential role of lactobacilli as prophylactic agents against genital pathogens. AIDS Patient Care STDS 1999;13:747–51

- Schöni M, Graf F, Meier B. [Treatment of vaginal disorders with Döderlein bacteria]. Saz 1988;126:139–42 [German]

- Vaneechoutte M. The human vaginal microbial community. Res Microbiol 2017;168:811–25

- Unlu C, Donders G. Use of lactobacilli and estriol combination in the treatment of disturbed vaginal ecosystem: a review. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2011;12:239–46

- Anahtar MN, Byrne EH, Doherty KE, et al. Cervicovaginal bacteria are a major modulator of host inflammatory responses in the female genital tract. Immunity 2015;42:965–76

- Witkin SS, Linhares IM, Giraldo P. Bacterial flora of the female genital tract: function and immune regulation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:347–54

- Hummelen R, Macklaim JM, Bisanz JE, et al. Vaginal microbiome and epithelial gene array in post-menopausal women with moderate to severe dryness. PLoS One 2011;6:e26602

- Shen J, Song N, Williams CJ, et al. Effects of low dose estrogen therapy on the vaginal microbiomes of women with atrophic vaginitis. Sci Rep 2016;6:24380

- Borges S, Silva J, Teixeira P. The role of lactobacilli and probiotics in maintaining vaginal health. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;289:479–89

- Kaiser RR, Michael-Hepp J, Weber W, et al. Absorption of estriol from vaginal tablets after single and repeated application in healthy, postmenopausal women. Therapiewoche 2000;3:2–8

- Feiks A, Grunberger W. [Treatment of atrophic vaginitis: does topical application allow a reduction in the oestrogen dose?]. Gynäkol Rundsch 1991;31(Suppl 2):268–71 [German]

- Sousa MS, Peate M, Jarvis S, et al. A clinical guide to the management of genitourinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2017;9:269–85

- Buchholz S, Mogele M, Lintermans A, et al. Vaginal estriol-lactobacilli combination and quality of life in endocrine-treated breast cancer. Climacteric 2015;18:252–9

- Donders G, Bellen G, Neven P, et al. Effect of ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli vaginal tablets (Gynoflor(R)) on inflammatory and infectious markers of the vaginal ecosystem in postmenopausal women with breast cancer on aromatase inhibitors. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015;34:2023–8

- Kanne B, Patz B, Wackerle L. [Local treatment of vaginal infections with Doederlein bacteria and estriol in climacterium and senium.]. Frauenarzt 1986;3:35–40 [German]

- Barrons R, Tassone D. Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review. Clin Ther 2008;30:453–68

- Panay N, Fenton A. Vulvovaginal atrophy–a tale of neglect. Climacteric 2014;17:1–2