Abstract

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) has a significantly negative impact on affected women’s lives. However, despite the increasing number of GSM treatment options (e.g. non-hormonal vaginal products, vaginal hormones [estrogens], dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA; prasterone], vaginal laser therapy, oral ospemifene), many women remain untreated. The goal of the Swiss interdisciplinary GSM consensus meeting was to develop tools for GSM management in daily practice: a GSM management algorithm (personalized medicine); a communication tool for vaginal DHEA (drug facts box); and a communication tool for understanding regulatory authorities and the discrepancy between scientific data and package inserts. The acceptance and applicability of such tools will be further investigated.

摘要

更年期泌尿生殖系统综合征(GSM)对受影响女性的生活有显著的负面影响。然而, 尽管GSM治疗选择越来越多(例如非激素性阴道产品、阴道激素[雌激素]、脱氢表雄酮[DHEA;普拉睾酮]、阴道激光治疗、口服奥培米芬), 许多女性仍然没有得到治疗。瑞士跨学科GSM共识会议的目标是在日常实践中开发GSM管理工具:GSM管理算法(个性化医疗);阴道DHEA通讯工具(药物事实箱);以及一种沟通工具, 用于了解监管机构以及科学数据和包装说明书之间的差异。将进一步调查此类工具的可接受性和适用性。

Introduction

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) describes the hypoestrogenic changes to the vulvovaginal and bladder–urethral areas that occur in menopausal women [Citation1]. GSM symptoms may comprise genital symptoms (dryness, burning, irritation), sexual symptoms (lack of lubrication, discomfort or pain, impaired sexual function) and urinary symptoms (urgency, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections) [Citation2]. Symptoms associated with GSM are highly prevalent, affecting up to 84% of postmenopausal women [Citation3]. An international survey including more than 4000 menopausal women reported a decreased quality of life in 52% of women with symptomatic GSM [Citation4]. A recent case–control study comprising half a million women found a significantly increased risk for depression and anxiety in women with symptomatic GSM compared to women without GSM [Citation5]. In contrast to vasomotor symptoms, which will decrease with time, GSM symptoms, if untreated, will remain or even become worse with lasting hypoestrogenic state. However, despite the negative impact GSM may have on women’s lives, many women remain untreated.

Therefore, the goals of the Swiss interdisciplinary consensus meeting were to update scientific evidence for GSM treatment, and to provide tools to support daily clinical practice. These tools include: a GSM management algorithm (personalized medicine); a communication tool for vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA); and a communication tool for explaining the discrepancy between regulatory labeling and current scientific data.

In order to gather different points of view, experts and stakeholders from various (medical) fields were invited; for example, gynecological endocrinology (P.S., A.R., S.S.), sexual medicine (J.B., A.R., A.G.), psychiatry (A.G.), internal medicine endocrinology (M.B.), Swiss Menopause Society (P.S., A.R.), Swiss Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (S.S.), health-care research (S.B.), and risk communication and statistics (V.S.).

Estrogens for GSM treatment

According to international guidelines [Citation3], first-line therapy for women with symptomatic vaginal atrophy/GSM includes non-hormonal lubricants with sexual intercourse and, if indicated, regular use of long-acting vaginal moisturizers. For symptomatic women with moderate to severe vaginal atrophy and for those with milder vaginal atrophy who do not respond to lubricants and moisturizers, vaginal DHEA (prasterone) (see next section), the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene [Citation6] (not available in Switzerland) and estrogen therapy either vaginally at low dose or systemically are recommended. Low-dose vaginal estrogen is preferred when vaginal atrophy is the only menopausal symptom. For women receiving systemic estrogen therapy for other menopausal symptoms, such as hot flushes, low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy may be added if relief of atrophic symptoms is insufficient.

Internationally, there are various vaginal estrogen preparations containing either estradiol, estriol or conjugated equine estrogens, respectively. presents an overview of vaginal estrogen products approved by the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic). A progestogen for endometrium protection is generally not indicated when low-dose vaginal estrogen is administered for symptomatic GSM. However, endometrial safety data are not available for use longer than 1 year. However, based on observational safety data, vaginal estrogens may be used as long as needed [Citation3]. Vaginal estrogens may be applied as cream, gel, suppositories and tablets daily within the first 2–3 weeks, and then twice weekly, whereas the vaginal ring is applied once every 3 months. They all have a good efficacy and safety profile [Citation7]. However, about 12–15% of women will still have GSM symptoms despite vaginal estrogen treatment [Citation7].

Table 1. Vaginal estrogen products approved by the Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic).

Vaginal DHEA for GSM treatment

In recent years, additional GSM treatment options have become available including vaginal laser therapy [Citation8] (available in Switzerland but not covered by Swiss health insurances) and vaginal prasterone (DHEA, approved by Swissmedic in 2020).

DHEA is a prohormone produced by the adrenal glands. DHEA is metabolized to androgens (androstenedione, testosterone) and then aromatized to estrogens (estrone, estradiol). During the reproductive life stage, serum DHEA(-sulfate) levels are much higher than serum testosterone and estradiol levels. During reproductive aging DHEA and testosterone formation decrease, resulting in 50% lower serum levels around menopause compared to young adulthood [Citation9]. Development of vaginal DHEA for GSM treatment started almost 20 years ago. presents an overview of relevant clinical studies performed with vaginal DHEA ovules (suppositories/pessaries) [Citation10–31]. In 2016, vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (trade name Intrarosa®). In 2020, vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day was also approved by Swissmedic.

Table 2. Overview of clinical studies performed with vaginal DHEA ovules.

Vaginal DHEA is different from vaginal estrogens in some aspects. Based on the concept of intracrinology [Citation32], an inactive prohormone enters cells of peripheral target organs where it is transformed into an active hormone by intracellularly localized enzymes (). Thus, the active hormone exerts its effects within the cell only, but not systemically since they are inactivated within the same cells. This minimizes changes in serum sex steroid levels after daily vaginal DHEA application [Citation13,Citation29]. Similarly, there were no endometrial changes reported after 1 year of daily application of vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg [Citation31]. The most frequent adverse reaction reported in clinical trials with vaginal DHEA was vaginal discharge (9.9% of patients [Citation31]). The efficacy of vaginal DHEA on the symptoms of dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, as well as on three indicators of vaginal health (vaginal pH and percentage of parabasal and superficial cells), was shown in two pivotal 12-week placebo-controlled clinical trials [Citation31]. Furthermore, in women suffering from GSM, sexual function has been shown to improve in all Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) domains with vaginal DHEA application [Citation25]. At first sight, this may be a surprising finding as serum sex steroid levels remain within the normal range for postmenopausal women and thus the brain is not exposed to, for example, supraphysiological levels of androgens for that population. Most likely, it is not mediated by endocrine mechanisms. In contrast to vaginal estrogens, vaginal DHEA does not only have a beneficial effect on the vaginal epithelium but also on the cell layers below. Accordingly, in oophorectomized rats, vaginal DHEA has been found to increase the density of nerve fibers within the lamina propria and the density of sympathetic fibers within the muscularis [Citation34]. Sympathetic fibers induce rhythmic contractions of the vaginal wall (orgasm), as well as an elongation and widening of the vagina.

Figure 1. Fundamentals of intracrinology: mechanism of action of DHEA (reprinted with permission from Labrie and Labrie [Citation33]). DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHT, dihydrotestosterone.

![Figure 1. Fundamentals of intracrinology: mechanism of action of DHEA (reprinted with permission from Labrie and Labrie [Citation33]). DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHT, dihydrotestosterone.](/cms/asset/81b0f4a3-d3d8-48fd-b53d-a221ffff3222/icmt_a_2008894_f0001_c.jpg)

Of course, as for all GSM treatment options, there are conditions in which vaginal DHEA will not be the first choice for a patient. For example, if other menopausal symptoms are present requiring systemic menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), additional vaginal therapy might not be necessary. In women with a focus on urological GSM symptoms, vaginal estrogen therapy that has been specifically studied in, for example, urinary incontinence, overactive bladder or recurrent urinary tract infection, respectively, should be chosen. Also, other choices might be preferred based on patient’s preference on formulation and posology. For example, some women are happy to use a product daily (better to remember) while others do not like the idea of ‘putting something into the vagina’ every single day. In breast cancer survivors, international recommendations differ. For example, in Europe and Switzerland, vaginal DHEA is contraindicated in breast cancer survivors. In contrast, the American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline states that vaginal DHEA can be recommended for women with current or a history of breast cancer who are on aromatase inhibitors and have not responded to previous treatment [Citation35]. Furthermore, a retrospective cohort study has shown that vaginal DHEA was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence [Citation36]. Similarly, a pilot study demonstrated that in breast cancer survivors treated with aromatase inhibitors, serum estrogen levels did not increase when using vaginal prasterone [Citation37]. Finally, there is no contraindication for breast cancer survivors in the Intrarosa® package labeling in Canada and the USA.

Approval process for new products for GSM treatment

Internationally, the regulatory process for new drug approval differs, resulting in slightly different indications for vaginal (pro)hormones for GSM treatment. presents an overview of vaginal DHEA regulation for GSM treatment in selected markets. Vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg is administered daily with the use of the provided applicator or with fingers. In contrast to vaginal estrogens (tablet, cream, gel, suppository) where there is an initiation period followed by a maintenance therapy period, vaginal DHEA is always applied on a daily basis regardless of treatment duration. As all regulatory authorities require safety data (including endometrial biopsies) for at least 1 year, all studies investigating new (pro)hormones for GSM treatment fulfill these criteria – but not more. Thus, in general, endometrial safety data are usually limited to 1 year of treatment.

Table 3. Overview of vaginal DHEA regulation for GSM treatment in selected markets (status: March 2021).

The biggest challenge for communication, however, is the discrepancy between regulatory authorities’ demands () and scientific data (). For example, in European countries, as DHEA is metabolized to estrogens and was thus approved under guidelines used for estrogens. Product labeling is based on standard templates used for all hormonal products: all potential risks associated with long-term (!), systemic (!), oral (!), combined (!) estrogen–progestogen MHT had to be mentioned in the package insert, although vaginal DHEA does not increase serum estrogens levels (no systemic effect) [Citation13,Citation29] and has scientifically neither been associated with increased risks for cardiovascular events, cancer and dementia (no known safety issues) in clinical trials performed (n = 1196 patients exposed to 6.5 mg of prasterone from 12 to 52 weeks) [Citation23] nor from postmarketing experience since launch in 2017. Similarly, from a medical-scientific point of view there is no known reason not to combine vaginal (pro)hormones with systemic MHT – just the contrary applies: as many women still suffer from GSM despite being treated with systemic (ultra)low-dose MHT, additional vaginal (pro)hormones should be offered. However, there are no studies to document the combination is safe, and neither are there long-term studies on the safety of DHEA.

Practical recommendations

Taking the information already mentioned together, three main questions remain for patient consultation in practice. First, to whom should be offered which GSM treatment (personalized medicine)? Second, how to communicate real (scientific) benefits and risks of vaginal DHEA (drug facts box)? Third, how to communicate the discrepancy between scientific data and package inserts?

Personalized GSM treatment

Today in Switzerland, approved GSM treatment options comprise non-hormonal vaginal products (lubricant, moisturizer, cream), vaginal estrogens (tablet, gel, cream, suppository, ring), vaginal DHEA (suppository) and vaginal laser therapy, respectively. Some of the vaginal products come with an applicator, some do not. Vaginal DHEA is a suitable solution for all postmenopausal women suffering from dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and irritation/itching due to estrogen deficiency. Vaginal DHEA brings all benefits that can be expected from local estrogenic treatments with the added benefit to genitourinary health attributed to androgens [Citation38,Citation39]. Thus, vaginal DHEA is currently the only approved physiological treatment addressing both estrogen and androgen deficiencies causing GSM [Citation3].

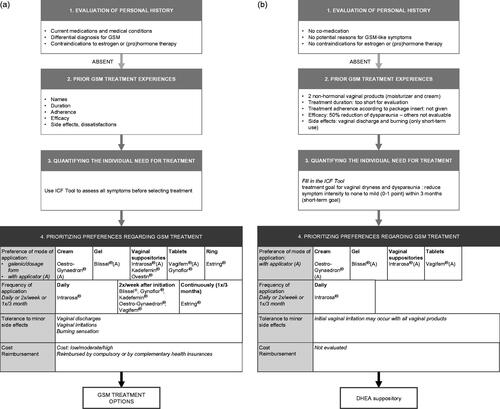

provides an algorithm for choosing the ‘right’ GSM treatment for the individual woman which, however, still needs testing and implementation in daily practice. This algorithm comprises four steps:

Figure 2. (a) Algorithm for choosing the ‘right’ GSM treatment for the individual woman. (b) Example algorithm for choosing the ‘right’ GSM treatment for the individual woman. DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; GSM, genitourinary syndrome of menopause; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Taking the personal history (comorbidities, co-medication)

Taking the personal history helps to rule out other potential reasons for GSM-like symptoms and to evaluate potential contraindications () approved by the Health Authority for vaginal (pro)hormone products.

Evaluating prior GSM treatment experiences (number of products, treatment duration, treatment adherence, efficacy, adverse events)

Many women have tried other GSM treatments before. For consultation it is helpful to know which product a woman has used before (how many?), for how long she has used it/them (long enough?), whether she adhered to the treatment regimen according to the package insert (if not, why?), how effective the treatment(s) was/were (symptom reduction on a scale 0–100%) and whether she experienced any side-effects (if yes, which?).

Quantifying the individual need for treatment

Although it seems obvious that reported GSM symptoms should improve with the GSM treatment to be chosen, it is helpful to quantify symptom intensity as well as urgency and expected degree of symptom relief prior to treatment start. To do so, a so-called ‘ICF categorical profile’ has been developed by linking the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS-II) to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation40]. First, a woman defines her global goal (>12 months), mid-term goal (<12 months) and short-term goal (3 months). Then the intensity of 11 MRS-II items including ‘sexual problems’, ‘bladder problems’ and ‘dryness of vagina’ can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (no symptom [0 points], mild symptom [1 point], moderate symptom [2 points], severe symptom [3 points], very severe symptom [4 points]). Each symptom is then linked to the goal category (global, mid-term, short-term). Finally, the expected extent of symptom reduction is defined on the MRS-II 5-point Likert scale (0–4 points). Obviously, if the patient’s focus is not on GSM symptoms or also involves other menopausal symptoms, the treatment options to be discussed need to be broader (not part of this algorithm).

Prioritizing preferences of the GSM treatment to be chosen (mode of application, frequency of application, willingness to eventually experience minor side-effects, cost)

Knowing and prioritizing the woman’s preferences of a treatment to be chosen are essential as this will increase her acceptance of and adherence to the treatment, improve the patient–physician communication and is thus the basis for shared decision-making.

For example, a 57-year-old healthy postmenopausal woman presents with menopausal symptoms, especially GSM ():

Step 1: Taking the personal history

No other potential reasons for GSM-like symptoms, no co-medication, no contraindications for vaginal (pro)hormone products.

Step 2: Assessing prior GSM treatment experiences

For GSM, she has tried two non-hormonal vaginal products before, a moisturizer and a cream. Both treatments were applied on demand only (prior to sexual intercourse) as she did not like the vaginal discharge and burning sensation upon application (for being able to have sexual intercourse these side-effects were acceptable). So far, we can summarize: number of products used before consultation, two; treatment duration, too short for evaluation; adherence to treatment according to package insert, not given; treatment effectiveness, 50% reduction of dyspareunia, other GSM symptoms not evaluable; side-effects, vaginal discharge and burning (only short-term use).

Step 3: Quantifying the individual need for GSM treatment

Her statements in the ‘Categorical ICF profile’ are as follows (): global goal (>12 months), feeling like the woman she used to be again; mid-term goal (<12 months), regain overall sexual function; short-term goal (3 months), reduce vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. The intensity of ‘sexual problems’ is rated as severe (3 points), the intensity of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia as very severe (4 points each). Her treatment goal for ‘sexual problems’ is to reduce symptom intensity to mild (1 point) within 12 months (mid-term goal). Her treatment goal for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia is to reduce symptom intensity to none to mild (0–1 point) within 3 months (short-term goal).

Step 4: Prioritizing preferences of the GSM treatment to be chosen

Finally, after providing an overview of treatment options, her GSM treatment preferences are prioritized as follows: applicator preferred (does not like to touch herself in the vagina), daily application (better to remember), initial vaginal irritation is ok (but not forever), low/moderate cost. Taking all information together, the following GSM treatment options emerge: vaginal (pro)hormone product > only products with applicators; estriol cream/gel, estradiol tablet, DHEA suppository > only product applied daily; DHEA suppository becomes the chosen treatment. Initial vaginal irritation may occur with all vaginal products. The first follow-up consultation will be scheduled after 3 months (short-term goal) for treatment evaluation and adjustment if needed.

Table 4. Example of an ICF categorical profile (modified according to Zangger et al. [Citation40]).

Drug facts box for vaginal DHEA

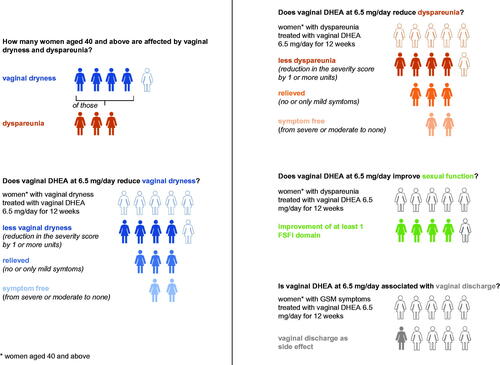

A drug facts box helps to communicate benefits and risks of vaginal DHEA ().

Figure 3. Drug facts box for vaginal DHEA. DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; GSM, genitourinary syndrome of menopause.

Question: How many women are affected by vaginal dryness and dyspareunia?

Answer: Four out of five women aged 40 years and above complain of vaginal dryness. Of those, three out of five complain of dyspareunia [Citation41,Citation42].

Question: Does vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day reduce vaginal dryness?

Answer: If five women with moderate/severe vaginal dryness are treated with vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day for 12 weeks, four out of five will have less vaginal dryness (84% responders, reduction in the severity score of 1 or more). Of those responders, three women (89%; 75% of total patients treated) will have their vaginal dryness relieved (only mild or no more symptom), including two women (48%; 40% of total patients treated) who will be symptom-free [Citation23].

Question: Does vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day reduce dyspareunia?

Answer: If five women with moderate/severe dyspareunia are treated with vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day for 12 weeks, four out of five will have less dyspareunia (79% responders). Of those responders, three women (80%; 63% of total patients treated) will have their dyspareunia relieved (only mild or no more symptom), including two women (36%; 28% of total patients treated) who will be symptom-free [Citation23].

Question: Does vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day improve sexual function (based on FSFI domains [desire, arousal, orgasm and pain])?

Answer: If five women with moderate/severe dyspareunia are treated with vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day for 1 year, four out of five will experience improvement of at least one (out of six) FSFI domain (p = 0.0124 versus women using a placebo) [Citation19].

Question: Is vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day associated with vaginal discharge?

Answer: If five women with GSM symptoms are treated with vaginal DHEA at 6.5 mg/day for 12 weeks, less than one woman (10%) will experience vaginal discharge as a side-effect [Citation23].

Communication tool for understanding regulatory authorities

Sometimes there is a huge discrepancy between the scientific data and the package insert of a certain drug. Not surprisingly, patients may then distrust her/his physician’s advice when reading the package insert. Similarly, also for physicians this discrepancy is hard to understand and they may start distrusting what they are told by so-called ‘key opinion leaders’. Therefore, this section aims to clarify some obscurities.

According to the authorities’ guidelines the category ‘adverse events’ within the package insert has to list all adverse events that have been observed in clinical trials and that may have a causal relationship to the drug (although this may be a subjective attribution). In contrast, criteria are less clear for the category ‘precautions’. In general, potential severe adverse events should be mentioned herein. Internationally, the approval processes differ. Thus, although the underlying scientific data are the same, the resulting decisions are not. For example, there is no internationally consented algorithm to evaluate safety issues. Thus, as there is no standard on the regulatory level there is also no internationally accepted algorithm for pharmaceutical companies to assess all safety aspects to support the approval process.

Furthermore, in some countries, history of a product class and ‘equal rights’ are important. If, for example, a vaginal estrogen product (in much higher and potentially systemically acting dosage) was approved 30 years ago and a certain adverse event was reported and included in the package insert, then a new vaginal estrogen product (in much lower dosage) has to report the same adverse events even if the causal relationship for the new product is questionable. In respect to vaginal DHEA this discrepancy in international approval processes becomes obvious. In the USA and Canada, the regulatory authorities accepted to have a labeling based on the scientific data (adverse events) obtained during the clinical studies, whereas in Europe the European Medicines Agency (EMA) preferred to keep the same CMDh HRT core labeling template [Citation43] of (old-fashioned) vaginal estrogens as there is no head-to-head trial showing another safety profile for vaginal DHEA compared to (old-fashioned) vaginal estrogens. Furthermore, this labeling is not based on evidence obtained with these vaginal preparations, but on deductions from oral systemic MHT. As DHEA is a prohormone, it has been evaluated according to hormone standards. Switzerland mainly follows the EMA decision.

Conclusion

GSM has a significantly negative impact on affected women’s lives. The Swiss GSM consensus group identified three major challenges in GSM management and developed the following tools: a GSM management algorithm (personalized medicine); a communication tool for vaginal DHEA (drug facts box); and a communication tool for understanding regulatory authorities. Yet both of the tools need testing and implementation in daily practice.

Potential conflict of interest

The authors have been part of an interdisciplinary expert board funded by Labatec Pharma SA. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ms Hostettler, secretary, for formatting support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. and P. Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the international society for the study of women’s sexual health and the North american menopause society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- Kim H-K, Kang S-Y, Chung Y-J, et al. The recent review of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. J Menopausal Med. 2015;21(2):65–71.

- The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of the North American menopause society. Menopause. 2020;27(9):976–992.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233–238.

- Moyneur E, Dea K, Derogatis LR, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in women newly diagnosed with vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. Menopause. 2020;27(2):134–142.

- Palacios S. Ospemifene for vulvar and vaginal atrophy: an overview. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2.

- Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD001500.

- Romero-Otero J, Lauterbach R, Aversa A, et al. Laser-Based devices for female genitourinary indications: position statements from the european society for sexual medicine (ESSM). J Sex Med. 2020;17(5):841–848.

- Lobo RA. Androgens in postmenopausal women: production, possible role, and replacement options. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56(6):361–376.

- Archer DF, Labrie F, Bouchard C, et al. Treatment of pain at sexual activity (dyspareunia) with intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone). Menopause. 2015;22(9):950–963.

- Bouchard C, Labrie F, Archer DF, et al. Decreased efficacy of twice-weekly intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone on vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18(4):590–607.

- Bouchard C, et al. Effect of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on the female sexual function in postmenopausal women: ERC-230 open-label study. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2016;25(3):181–190.

- Ke Y, Gonthier R, Simard J-N, et al. Serum steroids remain within the same normal postmenopausal values during 12-month intravaginal 0.50% DHEA. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2015;24(3):117–129.

- Ke Y, Labrie F, Gonthier R, et al. Serum levels of sex steroids and metabolites following 12 weeks of intravaginal 0.50% DHEA administration. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;154:186–196.

- Labrie F. DHEA, important source of sex steroids in men and even more in women. Prog Brain Res. 2010;182:97–148.

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (Prasterone), a physiological and highly efficient treatment of vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2009;16(5):907–922.

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Effect of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone) on libido and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16(5):923–931.

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Serum steroid levels during 12-week intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone administration. Menopause. 2009;16(5):897–906.

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. High internal consistency and efficacy of intravaginal DHEA for vaginal atrophy. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26(7):524–532.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Bouchard C, et al. Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone), a highly efficient treatment of dyspareunia. Climacteric. 2011;14(2):282–288.

- Labrie F, Archer D, Bouchard C, et al. Lack of influence of dyspareunia on the beneficial effect of intravaginal prasterone (dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA) on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2014;11(7):1766–1785.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Koltun W, et al. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause. 2016;23(3):243–256.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Martel C, et al. Combined data of intravaginal prasterone against vulvovaginal atrophy of menopause. Menopause. 2017;24(11):1246–1256.

- Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez JL, et al. Effect of intravaginal DHEA on serum DHEA and eleven of its metabolites in postmenopausal women. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111(3–5):178–194.

- Labrie F, Derogatis L, Archer DF, et al. Effect of intravaginal prasterone on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy. J Sex Med. 2015;12(12):2401–2412.

- Labrie F, Martel C. A low dose (6.5 mg) of intravaginal DHEA permits a strictly local action while maintaining all serum estrogens or androgens as well as their metabolites within normal values. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2017;29(2):39–60.

- Labrie F, Martel C, Bérubé R, et al. Intravaginal prasterone (DHEA) provides local action without clinically significant changes in serum concentrations of estrogens or androgens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:359–367.

- Labrie F, Montesino M, Archer DF, et al. Influence of treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy with intravaginal prasterone on the male partner. Climacteric. 2015;18(6):817–825.

- Martel C, Labrie F, Archer DF, et al. Serum steroid concentrations remain within normal postmenopausal values in women receiving daily 6.5mg intravaginal prasterone for 12 weeks. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;159:142–153.

- Montesino M, Labrie F, Archer DF, et al. Evaluation of the acceptability of intravaginal prasterone ovule administration using an applicator. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(3):240–245.

- Portman DJ, Labrie F, Archer DF, et al. Lack of effect of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, prasterone) on the endometrium in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1289–1295.

- Labrie F. Intracrinology and menopause: the science describing the cell-specific intracellular formation of estrogens and androgens from DHEA and their strictly local action and inactivation in peripheral tissues. Menopause. 2019;26(2):220–224.

- Labrie F, Labrie C. DHEA and intracrinology at menopause, a positive choice for evolution of the human species. Climacteric. 2013;16(2):205–213.

- Pelletier G, Ouellet J, Martel C, et al. Effects of ovariectomy and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on vaginal wall thickness and innervation. J Sex Med. 2012;9(10):2525–2533.

- Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation of cancer care Ontario guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):492–511.

- Moyneur E, et al., Absence of increase in the incidence or recurrence of breast cancer in women diagnosed with vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) treated with intravaginal prasterone (DHEA) on the risk of breast cancer: A retrospective matched cohort study. 2020: 19th world congress of Gynaecological Endocrinology.

- Dury A, et al. Serum estrogen levels do not increase following intravaginal administration of prasterone (DHEA) in women treated with an aromatase inhibitor for breast cancer – results from a pilot study. 2020: 19th world congress of Gynaecological Endocrinology.

- Palacios S. Expression of androgen receptors in the structures of vulvovaginal tissue. Menopause. 2020;27(11):1336–1342.

- Traish AM, Vignozzi L, Simon JA, et al. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6(4):558–571.

- Zangger M, Poethig D, Meissner F, et al. Linking the menopause rating scale to the international classification of functioning, disability and health – a first step towards the implementation of the EMAS menopause health care model. Maturitas. 2018;118:15–19.

- Krychman M, Graham S, Bernick B, et al. The women’s EMPOWER survey: Women’s knowledge and awareness of treatment options for vulvar and vaginal atrophy remains inadequate. J Sex Med. 2017;14(3):425–433.

- Huang AJ, Gregorich SE, Kuppermann M, et al. Day-to-Day impact of vaginal aging questionnaire: a multidimensional measure of the impact of vaginal symptoms on functioning and well-being in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22(2):144–154.

- CMDh, Core Package Leaflet For Hormonal Replacement Therapy Products based on core SmPC HRT revision 7, June 2020. 2020.