ABSTRACT

Resilience is a dominant humanitarian-development theme. Nonetheless, some humanitarian-development programmes have demonstrably negative impacts which encourage vulnerable people to actively resist these programmes. Based on 12 months ethnographic fieldwork in a Ugandan refugee settlement during 2017–18, this paper argues refugee residents articulated their refusal of humanitarian failure and corruption through active, largely non-political, resistance. I term the diverse strategies used ‘resistant resilience’, arguing that the agency central to these practices require that assumptions about resilience are reconsidered. I conclude that this refugee community’s most important resilience strategies were active resistance, demonstrating that resilience can be manifested through marginalised peoples’ desire to resist exploitation.

Introduction

This paper describes South Sudanese refugees’ practises of resistance to corruption and other bureaucratic failings within a Ugandan refugee settlement. By focusing on how refugees in Palabek Refugee Settlement (PRS) reacted to food aid delivery fraud in late 2017 and early 2018, I demonstrate how corruption within Uganda’s refugee programming impacted refugees’ lives and undermined their survival, coping, and resilience. In doing so, I detail some underappreciated and under-theorised elements of how humanitarian failure effects vulnerable peoples’ survival: in this case, by showing how fraud and corruption created a context that refugees were forced to resist in order to survive. I propose two main arguments: firstly, that agency is central to refugees’ diverse resistance and resilience strategies, and secondly, that vulnerable peoples’ inherent resilience is demonstrated by purposeful acts of resistance to exploitation. As Ryan (Citation2015, p. 300) has argued, ‘resilience itself may be a tactic of resistance employed collectively and strategically’.

However, although I emphasise how humanitarian failure systematically marginalises refugees, this is not my primary purpose. It is empirically important that not everyone affected by corruption is silent, and my focus is therefore refugees’ ground-up resistance to these humanitarian shortcomings. Following her work on the impacts of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in 2017, Sou (Citation2021b, p. 11) agitated that ‘further empirical studies investigating resilience may uncover how populations framed as “just coping” are in fact engaging in an adaptable, flexible resistance [and] … could explore responses to poverty or conflict, in contexts where people are systematically marginalised.’ This is what I do here. Indeed, I suggest refugees’ responses reveal three interconnected elements: firstly, the everyday agency of refugees, despite difficult conditions (cf. Bjørkhaug Citation2020, Stites et al. Citation2021); secondly, that many responses are, directly or indirectly, acts of resistance (cf. Ryan Citation2015); and thirdly, that ‘so-called apolitical acts of resilience can represent political acts of resistance’ (Sou Citation2021b, p. 3; cf. Sou Citation2021a). Because these are acts of resistance that simultaneously demonstrate refugees’ resilience, I argue they are important manifestations of what I will call ‘resistant resilience’: how vulnerable peoples, through their very attempts at survival, must often resist exploitation or oppression in ways demonstrating the underlying resilience of their lives more generally. As such, and following Bourbeau and Ryan (Citation2018, p. 221), I advocate ‘for the usefulness of a relational approach to the processes of resilience and resistance’.

Although the international system is responsible for maintaining the lives and security of the world’s refugee population, this usually amounts to providing little more than minimal survival requirements, like water, strictly regulated food, and basic shelter (sometimes supplemented by health and education services). Nonetheless, although the agencies tasked with providing services often talk about promoting resilience, they seem to demand refugees are passive, grateful recipients of what they give, no matter its quality or quantity. However, as with people anywhere, refugees have hopes, aspirations, and agency and, in my experience, few are prepared to passively submit just to receive the paternalistic provision of life’s minimum requirements. This is especially true when those providing their needs seem ineffective, inefficient or corrupt. In such cases, like those described here, refugees may instead undertake their own survival-oriented practices. I understand the ‘resilience’ of the refugees I worked with as this general attitude towards life, an attitude that is demonstrated through ordinary acts of survival-oriented agency and practices of ‘resistance’ (cf. Scott Citation1985, p. xvi; Sou Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

In this paper, I will argue that despite the periodic disappearance of food aid, Palabek’s refugees adapted to their often-inhumane living conditions by transforming existing coping strategies and developing new ones. Moreover, I argue that their resilience was enhanced, not only despite actions undertaken by humanitarian and governance actors and institutions, but specifically through active, ground-up development of ‘resistant resilience’: a diverse range of individual and collective survival practices developed precisely in response to the structural inequalities infusing their everyday lives. My inspiration for this formulation is Scott’s (Citation1985, Citation1986) ‘everyday forms of peasant resistance’: that ‘prosaic but constant struggle between the peasantry and those who seek to extract labour, food, taxes, rents, and interest from them. Most forms of this struggle stop well short of outright collective defiance [instead being] the ordinary weapons of relatively powerless groups’ (Scott Citation1985, p. xvi, emphasis in original).

In my analysis I am also informed by Ryan’s (Citation2015) concept of ‘resilient resistance’ among women practicing sumud in Israeli-occupied Palestinian territory, which Ryan (Citation2015, p. 299) defines as ‘a tactic of resistance that relies on qualities of resilience such as getting by and adapting to shock’. Ryan (Citation2015, p. 313; cf. Bourbeau and Ryan Citation2018, p. 229) argues that

for resilience to be resistance, it has to fulfil two criteria: First, it must entail a concerted effort to provide a means of adaptation, making do, getting on, or working with what is at hand. Second, it must challenge the conditions that are experienced [by] communicat[ing] a message that denies the legitimacy of the conditions experienced. Enacting a resilient resistance means finding a way to get on with daily life without acquiescing to the prevailing political, economic, or social situation. It also means relating your resilient resistance to other members of your community, making it a collective practice.

On this basis, I suggest the empirical and theoretical connections between the processes underlying resistance and what might be variously called survival, coping, or resilience are more significant than often recognised, although recently this has been changing (cf. Bourbeau Citation2015, Ryan Citation2015, Bourbeau and Ryan Citation2018, Sou Citation2021a, Citation2021b). This is because, as Scott (Citation1986, p. 22) notes, ‘such [ordinary] forms of resistance are the nearly permanent, continuous, daily strategies of subordinate rural classes under difficult conditions’. I therefore argue it is important that analysis pays attention to how practices of resistance manifest local survival mechanisms (cf. Bourbeau Citation2015, Ryan Citation2015, Bourbeau and Ryan Citation2018, Sou Citation2021a, Citation2021b). To quote Scott (Citation1986, p. 23), it is no coincidence ‘the core [concerns] of peasant rebellion are each joined to the basic material survival needs of the peasant household. Nor should it be anything more than a commonplace that … everyday peasant resistance … flows from these same fundamental material needs’. Survival-oriented practices of resistance should therefore be considered as important means in which people enhance their life chances. This suggests that, instead of ‘mak[ing] the mistake of equating a particular government’s use of resilience with the concept of resilience’ (Bourbeau Citation2015, p. 379, cf. Bourbeau and Ryan Citation2018, p. 225), there needs to be reconsideration of the evidential basis of many resilience-based programmes’ results as well as an increase in more community-based forms of humanitarian accountability.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: after providing necessary background information, I discuss theoretical issues of resilience within refugee and humanitarian programming. I then briefly detail some recent Ugandan refugee industry scandals before discussing humanitarian failure in PRS itself, demonstrating the scope and scale of the difficulties refugees faced, including lengthy periods without food. In the final sections I discuss how Palabek’s refugees attempted to resist corruption and exploitation, detailing how this is a manifestation of both their agency and their resilience. I will show that agency is central, not only to the processes underlying survival but also to the practice of resistance. Indeed, the ‘resistant resilience’ of refugees in PRS in early 2018 was most obviously articulated in their resistance to corruption and humanitarian failure. I conclude by following Scott (Citation1986, p. 23) and suggesting that marginalised people’s most sustainable manifestations of everyday resilience are those in which they actively resist the conditions of their exploitation.

Background, Context, Methodology, Rationale

Conflict and displacement have long histories in South Sudan and Uganda, and both countries have hosted large numbers of refugees from the other nation (Kaiser Citation2006).Footnote1 What is now South Sudan has been plagued by conflict since before Sudan achieved independence in 1956, suffering the ravages of the First Sudanese civil war (1955–72), the Second Sudanese civil war (1983–2005), and the South Sudanese civil war (2013–18).Footnote2 Hundreds of thousands were killed in South Sudan’s most recent conflict (Checchi et al. Citation2018) and one in four residents were displaced (OCHA Citation2017, p. 2). Indeed, by 2016 the South Sudan conflict was not only responsible for the largest refugee crisis in Africa but the third largest in the world (OCHA Citation2017, p. 1). Over two million of South Sudan’s total estimated population of 12 million were refugees during my fieldwork, 800,000 of whom were in Uganda (OCHA Citation2017, p. 3).

Despite the violence of the recent war’s initial phases, it was only after a first Comprehensive Peace Agreement broke down in mid-2016 that conflict reached parts of the Equatoria region. This included those previously untouched Acholi- and Lotuko-speaking groups close to Uganda who comprised most of PRS’s first (and still numerically dominant) residents (). During my fieldwork, PRS comprised 58 blocks of varying geographical and demographic size divided among eight zones (numbered 1–7, with zone 5 split into 5A and 5B).Footnote3 Although PRS may eventually house 100,000 refugees (UNHCR Citation2017), there were only 30,000 residents by the end of 2018 (REACH Citation2018).

This paper is grounded in twelve months ethnographic fieldwork between early October 2017 and late November 2018. Formal and informal interviews and discussions were conducted with staff of The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), The Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), and various NGOs while observed events included food delivery across multiple Food Distribution Cycles (FDCs), both before and after changes resulting from the introduction of biometric verification in June 2018 (see below). During fieldwork, around 70% of PRS residents and 85% of leadership were Acholi-speaking, as were most NGO staff. A native Acholi speaker was used as my primary translator. There are important potential ethical considerations about discussing the relatively widespread (in 2017–18) practice of kubwariga (multiple registrations) arising from this research which I address later.

Uganda’s refugee legislation has garnered significant attention for its supposedly refugee-friendly nature: underpinned by the 2006 Refugees Act and the 2010 Refugee Regulations, the Ugandan resettlement model is portrayed as ‘progressive, human rights and protection oriented’ (Oliver and Boyle Citation2020, p. 1114) to be emulated by other refugee receiving countries. These provisions are complemented by Uganda’s 2017 adoption of the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF) and Refugee and Host Population Empowerment (ReHoPE) strategy (UN and WBG Citation2017), which are together designed to deliver integrated humanitarian and developmental support to refugees and host communities. All South Sudanese in Uganda have prima facie refugee status (UNHCR Citation2019, p. 7) and are entitled to the same basic services as citizens as well as some freedom of movement and rights to employment and business ownership (UN and WBG Citation2017, p. 2). Further, these initiatives have been aligned with Uganda’s Settlement Transformative Agenda (STA) and the National Development Plan II (NDP II, 2016–21) within which the STA is embedded. Uganda’s Settlement Transformative Agenda (STA) provides a non-encampment policy settling refugees alongside host communities on plots of land amenable to farming (UNHCR Citation2019, p. 7).

Both UNHCR and the Ugandan government clearly distinguish between a refugee camp and a refugee settlement, and only settlements are utilised in Uganda. The government argues settlements provide refugees the best foundation for self-reliance and self-sufficiency and this is why they are given land and ‘settled in villages, located within refugee-hosting districts refugees … [allowing them] the potential to live with increased dignity, independence, and normality in their host communities’. (UN and WBG Citation2017, p. 22; cf. IRRI Citation2018, p. 4). However, the realities of Uganda’s settlements are not as positive as official narratives suggest. Refugees’ rights are often practically unavailable, effectively encamping many refugees despite national policies. This may either due a lack of settlement-based services (UNHCR Citation2019, p. 6, cf. Kaiser Citation2006, p. 601), a lack of assistance for urban refugees (Hovil Citation2018, p. 7), or, more usually, interpretation and implementation of law (IRRI Citation2018, p. 4). Further, many settlements are in chronically underdeveloped rural areas (IRRI Citation2018, p. 4, Kaiser Citation2006, p. 601, 620). As Betts et al. (Citation2019, p. 4; cf. Bjørkhaug Citation2020, p. 266; Oliver and Boyle Citation2020, p. 1123) summarised, then, ‘The picture that emerges is mixed. It shows that aspects of the Ugandan model are highly effective for some populations, but that other aspects may be less effective than is commonly assumed’.

Oliver and Boyle (Citation2020, p. 1114) have argued that, despite what these policies intend, implementation

has been deeply problematic for both refugees and host communities and … often works against, refugees’ wellbeing and protection needs … largely because current self-reliance efforts are operationalised within broader structural conditions that impede refugees’ rights and undermine refugees’ agentic capacities to rebuild their lives and relationships in self-determining and sustainable ways.

Moreover, as Krause and Schmidt (Citation2019, p. 34) have noted, issues of individual agency are not incorporated into Ugandan refugee policies, which operate as ‘a predefined framework that trivialises the ways in which refugees strive to achieve self-reliance and resilience’. IRRI (Citation2018, p. 4) has noted that ‘the ability of refugees to locally integrate and establish a sense of self-sufficiency remains limited’ and, because of this, Bjørkhaug (Citation2020, p. 266; cf. Betts et al. Citation2019) has argued that Uganda’s ‘welcoming open door is on the verge of collapse’.Footnote4

An ethically-grounded position might note that one reason it seems that these policies often fail is because, at best, they barely provide the minimum for basic physical survival (cf. Evans and Reid Citation2013, p. 91–93; Titeca Citation2021). Indeed, as the resilience-oriented NGO ActionAid (Citation2016) argues, Uganda’s resilience-equals-self-reliance model simply promotes ‘siloed’ microeconomic programmes with little real-world impact. In Palabek, for instance, every household is given a single plot of land measuring 30 m x 30 m, no matter household size. Alongside living quarters, this land must contain latrines and cooking and bathing areas, as well as the gardens on which self-reliance estimates are based (Poole Citation2019, p. 22). Moreover, the surrounding land is stony and relatively barren. ‘Heavy reliance on cultivation as a source of sustainable livelihoods for refugees is therefore not a realistic long-term strategy’ (Poole Citation2019, p. 22). Not only is the carrying capacity of PRS land relatively low, but during the January–June 2018 period discussed here, people had been in the settlement less than 1 year. This meant that although NGOs had given some residents seeds and tools, there had been no opportunity to reap the rewards of agriculture.

Thus, just as Stites et al. (Citation2021; cf. Stites and Humphrey Citation2020) found among Uganda’s north-west settlements, widespread lack of food, money, and other resources made daily life in PRS a struggle. Although most people tried to supplement their food supplies in some way – with the unreliable pickings from tiny gardens, the goodwill of others, or small and unsteady businesses – their lives were lived ‘from one humanitarian food distribution to the next’ (Stites and Humphrey Citation2020, p. 25). As PRS was considered an ‘emergency situation’ during this period,Footnote5 monthly food aid was most residents’ only source of food and UNHCR and the World Food Programme (WFP) intended it should supply 100% of nutritional needs. Food aid provides more than just ‘food’, however: if required, it can be sold, gifted, or shared, providing an important means for developing refugee agency and sociality as well as economic resilience (cf. Buchanan‐Smith and Jaspars Citation2007, Stites and Humphrey Citation2020, Stites et al. Citation2021).

Refugees, Resilience, and Resistance

Agency and the politics of everyday survival are central to ‘resistant resilience’. Following Scott (Citation1985, Citation1986), I suggest that, often due simply to the needs of basic survival, exploitative acts encourage the already-marginalised into forms of resistance designed, not to ‘overthrow or transform a system of domination but rather to survive – today, this week, this season – within it’ (Scott Citation1986, p. 30). Indeed, Scott demonstrates that the preferred strategies of the powerless are ‘marked less by massive and defiant confrontations than by a quiet evasion that is equally massive and often far more effective’ (Scott Citation1986, p. 8): ‘passive non-compliance, subtle sabotage, evasion and deception’ (Scott Citation1986, p. 7). This is because such tactics not only have the least chance of discovery – and greatest likelihood of success – but minimise retaliation (Scott Citation1985, Citation1986, Sou Citation2021a, Citation2021b). ‘Everyday forms of resistance make no headlines’, he writes (Scott Citation1985, p. xvii).

The concept of ‘resistant resilience’ highlights two inconsistencies between normative understandings of resilience and the theoretical implications of my findings: firstly, a significant yet under-theorised element of resilience is based in marginalised persons’ own agency and resistance; secondly, most definitions of resilience omit issues of agency (broadly) and resistance (specifically). Our definitions should therefore be reconfigured in a more actor-focused way, accounting as much for real peoples’ specific, everyday interests and activities as any past, present, or future shocks, crises, or conflicts. However, like Titeca (Citation2021, p. 4), I do not conceptualise agency ‘as ‘unlimited’, without any structural constraints; [but] rather, … in a ‘complex dialectical interplay’ with the structural context in which it operates’. In recognising this, I agree with Bjørkhaug (Citation2020, p. 270), who points out that, ‘more important than “having agency” is how refugees realise that agency, given the social, economic, and political conditions, constraints, and opportunities they face’. In this way, in what follows I demonstrate that some refugees’ responses to their exploitation are not simply apolitical acts of mere survival but rather involve complex dialectics of agency and their everyday attempts to thwart the more oppressive constraints of the settlement’s structural context.

Definitions of resilience abound, although most contemporary attempts resemble that of the Rockefeller Foundation (Citation2017), who funded my research:

The capacity of individuals, communities and systems to survive, adapt, and grow in the face of stress and shocks, and even transform when conditions require it. Building resilience is about making people, communities and systems better prepared to withstand catastrophic events – both natural and manmade – and able to bounce back more quickly and emerge stronger.

The resilience of poverty-afflicted and war-affected people is well established, with the continued survival of millions of refugees in often-abject conditions an obvious example (Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015, Hilhorst Citation2018). Nonetheless, I resist interpretations which reduce resilience ‘to pure “survivability”’ (Krause and Schmidt Citation2019, p. 34), especially for those most marginalised. Similarly, because ‘resilience is not necessarily positively correlated with wellbeing’ (Béné et al. Citation2012, p. 13) and ‘one can be very poor and unwell, but very resilient’ (Béné et al. Citation2012, p. 14), I find conceptualisations equating resilience with ‘livelihoods’ or ‘self-reliance’ equally problematic (cf. Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015, Krause and Schmidt Citation2019).

Panter-Brick (Citation2002, p. 163) has noted it is ‘wrong to assume that vulnerability or protection lies in the variable … rather than in the active role taken by individuals under adversity: resilience is a reflection of an individual’s agency’. Resilience simply cannot be understood without actively considering agency and its restrictions. Further, just as the capacity for agency is linked with access to power and resources (cf. Bjørkhaug Citation2020, p. 270; Titeca Citation2021, p. 4), it is similarly impossible to accurately understand resilience without incorporating issues of agency, power, and the allocation and distribution of resources (both locally and globally). It is notable, then, that ‘amongst the dozens of definitions proposed in the literature [by 2012], none … mentioned the terms ‘power’ or ‘agency’’ (Béné et al. Citation2012, p. 13).

It is because of these oversights around agency, power, and resources that many critics of normative resilience argue that the proponents of resilience programmes actively discourage challenges to the hegemony of their (often imported) activities and concepts (cf. Evans and Reid Citation2013, Cretney Citation2014, Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015). As Bourbeau and Ryan (Citation2018, p. 225) argue, many pro-resilience approaches can be justifiably criticised ‘for facilitating the adjustments to a given situation/shock without challenging the underlying conditions that make it necessary to adjust’. Indeed, not only do resilience programmes assume and promote self-reliance-type passivity over political or economic resistance, but “when one examines policies and programs which ‘build resilience’ in detail, it is abundantly clear that resilience is essentially a new way of talking about neoliberalism” (Ryan Citation2015, p. 302).

Perhaps more significantly, despite the obvious global and national inequalities contributing to many peoples’ ongoing marginalisation, most proponents of normative resilience programming do not encourage local resistance to the very political or economic conditions initially requiring external-led resilience-based development (Evans and Reid Citation2013). Neocleous (Citation2013, p. 7) has argued that this is because ‘resilience wants acquiescence’. No wonder early critiques of resilience (as increasingly hegemonic development discourse) considered the concept inherently non-political (Cretney Citation2014). Whether or not this is true – the real connections between neoliberalism and ‘resilience thinking’ (Cretney Citation2014) might be over-stated (cf. Bourbeau Citation2015, Bourbeau and Ryan Citation2018) – there are nonetheless significant ‘forgotten crises’ of global geopolitics that most resilience programmers entirely forget, such as the ongoing ‘silent and slow’ instabilities caused by colonialism or structural adjustment programmes (cf. Wandji Citation2019, p. 299).

Normative resilience thinking which focuses predominantly on ‘bouncing back’ or ‘returning to equilibrium’ is therefore doubly problematic: not just in negating agency or reducing resilience to survivability but also by ignoring the larger, long-term inequalities making the impacts of any crisis so unevenly distributed (Béné et al. Citation2012, Cretney Citation2014). Thus, as Bourbeau and Ryan (Citation2018, p. 225–226) note, ‘one can clearly see the problem with a “resilience-building” programme that tries to make the poor “adaptable” to the effects of poverty, and, in so doing, ignoring the root causes’. Such thinking is especially dangerous when inequality is a significant source of crisis, such as the politics of resource allocation in the South Sudan Civil War (De Waal Citation2014). Development programmes that divorce resilience from context by targeting aid-efficient development of local resilience thereby remove ‘the inherently power-related connotation of vulnerability’ (Cannon and Müller-Mahn Citation2010, p. 623).

Especially within the ‘resiliency humanitarianism’ (Hilhorst Citation2018, p. 1) of refugee-facing organisations, decontextualising resilience ‘condone[s] critical conditions such as inequality, insecurity and violence as semi-permanent circumstances’ (Krause and Schmidt Citation2019, p. 36; cf. Ilcan and Rygiel Citation2015). Ultimately, this marks insecurity and violence as defining characteristics of marginalised worlds, placing responsibility for their conditions on affected populations rather than larger systems in which they live. This not only suggests the marginalised must assume primary responsibility for their own survival (cf. Hilhorst Citation2018, p. 6) but highlights that ‘there is a real risk that the politics of resilience … [becomes] a politics of abandonment’ (Hilhorst Citation2018, p. 6).

Instead, in what follows I show how some refugees demonstrate their resilience despite their exploitation. By this, I mean the resilience underlying some refugees’ approach to life is seen in how they refuse to passively accept exploitation. Indeed, Scott (Citation1985, Citation1986) argues that exploitation is precisely why everyday forms of resistance evolve, and ‘to understand these commonplace forms of resistance is to understand much of what the peasantry has historically done to defend its interests’ (Scott Citation1985, p. xvi). Thereby, in basing my analysis on actual individuals’ attempts to engage with humanitarian failure, I detail the resilience shown by refugees’ direct and more subtle means of resisting exploitation.

Ghosts in the Machine: Corruption and Fraud Within the Ugandan Refugee Industry

Institutionalised theft is not new either within Uganda generally (DfID Citation2013, Martini Citation2013) or the Ugandan refugee industry specifically (HRW Citation2013, Titeca Citation2021). Indeed, Uganda has been rated ‘highly corrupt’ by Transparency International every year since 1996 (Martini Citation2013, cf. DfID Citation2013), and there have been high profile scandals involving aid money for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in 2005 and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation in 2006 (HRW Citation2013) as well as post-conflict reconstruction efforts during 2012 (Martini Citation2013: 4). Government audits from 2012 further revealed ‘an estimated 7600 ghost workers … costing billions of shillings [from public funds] made possible by a collusive agreement between officials within the Ministry of Public Service, supported by the Ministry of Finance’ (Martini Citation2013, p. 3).Footnote6

The 2018 refugee scandal erupted after a large proportion of the £300 million pledged at the Uganda Solidarity Summit on refugees in June 2017 went missing (Sserunjogi Citation2018b), corruption that senior UNHCR sources believe ‘has been going on a long time’ (Birrell Citation2018) – probably from at least 2016 (Titeca Citation2021: 7). Other allegations included ‘fraud regarding food assistance, fraud regarding refugee numbers, refugees being required to pay bribes in order to get registered, and allegations that scholarships meant for refugees are instead going to Ugandans’ (Sserunjogi Citation2018b, cf. Titeca Citation2021, p. 2).Footnote7

According to the Daily Monitor, bank accounts ‘would be opened in the names of persons who are not genuine refugees and the cash … find its way into the pockets of OPM officials’ (Sserunjogi Citation2018a), with ‘the heads of the [OPM] Refugee Department putting together food logs and cash logs that included “ghost” refugees’ (Sserunjogi Citation2018a).Footnote8 In the case of food, which involved agencies beyond the OPM, ‘bloated food logs’ would ‘be passed on to UNHCR, which would then pass them on to WFP, which would in turn pass them on to its appointed implementing agency’ (Sserunjogi Citation2018a). This agency ‘would then deliver the food relief to the camps for distribution to the waiting recipients, many of whom would be agents of OPM officials’ (ibid). Agents sold this food to local traders, who openly admitted purchasing goods from ‘corrupt state officials’ (Birrell Citation2018). The Daily Monitor also revealed, in reports confirmed by the State Minister of Internal Affairs, Obiga Kania, ‘possible collusion between officials of the Refugee department in the OPM and the UN agencies charged with the refugee operations, especially UNHCR and WFP’ (Kafeero Citation2018, cf. OIOS Citation2018, Titeca Citation2021). However, as Titeca (Citation2021, p. 2) has shown, despite ‘donor countries and UNHCR initially us[ing] strong language to voice their concerns and insist on accountability’, this scandal has had virtually no fallout for those most actively involved. ‘On the contrary, the commissioner [for Refugees in OPM, Apollo Kazungu] – whose role was seen as central to the scandal – is back in office and has not appeared before court. The same donor countries that previously called for action have accepted this as a fait accompli’ (Titeca Citation2021, p. 2).

Indeed, one might suggest that the only people who felt any real effects from the results of the 2018 scandal were refugees themselvesFootnote9: following a UNHCR investigation which found that most urban refugees were invented (so-called ‘ghosts’, see below), donors halted funding until refugee numbers were confirmed using a biometric verification exercise (BVE) (Sserunjogi Citation2018b). Running between March and October 2018, the BVE sought to accurately quantify Uganda’s alleged refugee population of 1.5 million (Kafeero Citation2018). This BVE sought to ‘mitigate the risk of fraud, ensuring that assistance is well managed and provided only to verified, eligible refugees and asylum-seekers’ (OPM and UNHCR Citation2018). When completed, the verified refugee population was 1.1 million, around 75% of the original estimate (OPM and UNHCR Citation2018). Although the OPM was initially blamed for these discrepancies, it was later revealed that similarly fraudulent practices were equally widespread within UNHCR (OIOS Citation2018, Titeca Citation2021). PRS’s own BVE was completed in May 2018, the settlement’s official population dropping 25% from 38,000 to 29,000 (OPM and UNHCR Citation2018).Footnote10

Although the presence of ‘ghosts’ is a well-known, officially acknowledged source of inflated refugee numbers in Uganda pre-BVE (Birrell Citation2018, Kafeero Citation2018, OIOS Citation2018, Titeca Citation2021), there is no doubt that ‘kubwariga’ – refugees holding multiple identities (see below) – also added to the discrepancies, both nationally and in PRS. Nonetheless, either because the totals involved are built into a distribution’s base numbers are therefore in addition to any multiple identities, or through the direct theft of humanitarian resources, the documents below show evidence of corruption beyond variance connected to kubwariga.

Documentary, Eyewitness, and Anecdotal Evidence of Fraud

This section sets out the food-aid deficiencies faced by refugees in PRS during early 2018. It shows the extent of failure in the settlement’s humanitarian systems at this time, demonstrating how and why members of this vulnerable community developed their own individual and collective tactics of resistance. I argue that, by taking advantage of PRS’ inherently unequal power dynamics, these failures were exploitative. Moreover, by highlighting refugees’ own awareness of their exploitation, I provide the groundwork for later discussing refugees’ ‘resistant resilience’.

Official Documents

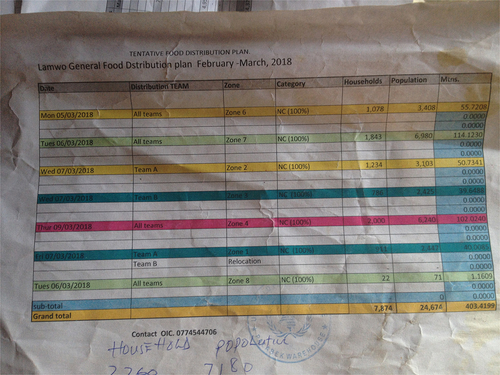

PRS residents gave me multiple eyewitness and anecdotal accounts of corruption. I discuss these later. More incriminating is the evidence shown in official documents like the Food Distribution Plans (FDPs) created and authorised at an organisational level by WFP and the OPM and detailing exactly how much food is given to how many people in which areas of PRS. I photographed many of these and three are reproduced here.Footnote11

My first document is the Lamwo General FDP for Cycle 2 (February 2018), created by WFP (). Things of note are it took two teams one full day to deliver food to 22 households (71 people) in Zone 8 – a very time and staff intensive exercise – and Zones 5A and 5B received no food. However, while PRS did not have Zone 8 until February 2021, the settlement’s most heavily populated areas (Zones 5A/5B) received nothing.Footnote12 Equally important is that, although food is designed to last four weeks, Cycle 2 delivery took place not in February but rather early March, nine-weeks after Cycle 1 delivery in January week two. Delays like this compound refugees’ other issues and are made additionally difficult by lack of communication: residents received no warning of Cycle 2’s delay, meaning they could not conserve Cycle 1 supplies if doing so were even possible given it provided only four weeks’ minimum needs. Further, Zones 5A and 5B still received nothing between Cycle 1 delivery in early January and Cycle 3 delivery at late March. Thus, hundreds of households comprising thousands of individuals existed on four weeks minimum-nutritional-level food for almost three months. Many people undoubtedly went hungry and undernourished. Some returned to war-torn South Sudan (O’Byrne and Ogeno Citation2020).Footnote13

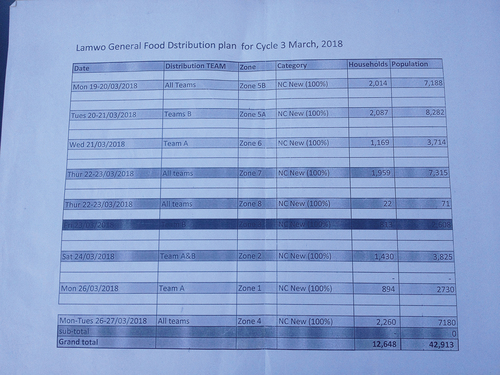

WFP’s FDP for Cycle 3 (March 2018) shows PRS’s highest alleged population count during fieldwork (): it suggests 43,000 residents were given food in March despite the verified post-BVE population being only 29,000 in June (). Cycle 3 still has 22 households (71 people) receiving aid in non-existent Zone 8 and needing a full day’s work from two teams.Footnote14 Meanwhile, although Zones 5A and 5B finally received food, several Zone 5 households told me that significant portions of this distribution were used to pay food debts incurred during Cycles 1 and 2, impacting their actual Cycle 3 consumption.

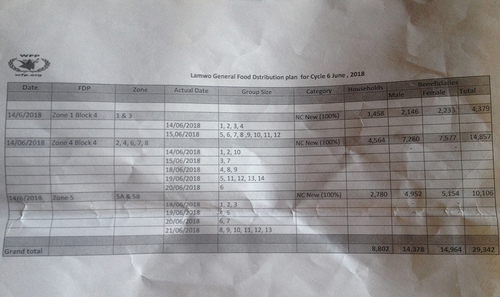

The final document is WFP’s FDP for Cycle 6 in June 2018 (). This document is the first FDP produced post-BVE and thus the first officially verified population. Population reduces substantially between the post-BVE Cycle 6 () and Cycle 3’s high-point (): households from 12,648 to 8,802 (minus 3,846) and population from 42,913 to 29,342 (minus 13,589). Indeed, BVE results indicate a total reduction of around 30%, despite increases in the number of actual residents through ongoing resettlement. ‘Ghosts’ likely account for these discrepancies.

So, what do these numbers mean?

First, perhaps 1500 households of 8000 people went without food in Zones 5A and 5B during February and March 2018.Footnote15 This documented statistic is backed up with a wealth of ethnographic evidence: many refugees’ food was simply not delivered. Second, for at least several months, food was distributed to a zone that did not exist. Given this likely involved staff involved in planning and implementation beyond PRS, it fits historical patterns of Ugandan corruption (Bailey Citation2008, HRW Citation2013, Martini Citation2013, Titeca Citation2021) and implies multiple employees of several organisations being at least minimally aware of what was happening. Thirdly, WFP documents attest food was provided to 43,000 refugees in March 2018, despite other WFP documents showing only 24,000 people received food in February and April. Where did those extra 19,000 people come from? Later, where did they go? How did no-one notice this discrepancy? Who actually received this food (or its associated funds) and why did this discrepancy occur in the month directly before BVE began?

The key point is this: the BVE showed that 30 per cent of PRS residents prior to June 2018 were not actually present although their humanitarian aid was still distributed to someone somewhere. To put this another way, 30 per cent of resources allocated to PRS prior to the BVE were not received by those they were allocated to. Most but not all probably went to ‘ghosts’. Who actually received this aid is an open question. Significantly, there are thus two different, interconnected crimes taking place here: the first defrauding donors by creating fictional refugees in the form of ‘ghosts’ (the 30 per cent population difference), the second stealing food directly from refugees via ‘lost’ or ‘missing’ aid.

Anecdotal and Eyewitness Accounts

In addition to these documents, PRS residents gave multiple accounts of similar humanitarian issues from 2017 and 2018. Much as Bailey (Citation2008) found among IDPs during northern Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) insurgency, people in PRS were ‘keenly aware of problems, such as exclusion from beneficiary lists and the inclusion of “fake” or “ghost” beneficiaries, but aside from cases where they have first-hand information, they [could] only offer theories about why a problem occurs and who is responsible’ (Bailey Citation2008, p. 9). Further echoing Bailey’s findings, ‘the vast majority of corruption issues described by camp residents [were] linked to registration processes for food and non-food items’ (Bailey Citation2008, p. 9). This suggests similar patterns of humanitarian corruption and theft were well established in Uganda by 2008, let alone the period of my 2017–18 fieldwork.

Take for example Margaret, a key female informant. Margaret was a rather typical middle-aged Acholi businesswoman: hard-working, religious, the head of a large intergenerational household. She also volunteered with food distribution in her zone. During a December 2017 interview, Margaret told me how widespread food aid corruption was:

You know there are cases of lost cards or stolen cards. Sometimes these are lost by [food] staff, sometimes by the person, sometimes they are taken by OPM or the NGOs to sell. People pay around UGX 50,000 ($13) for a ration card, some refugees have two or three. Many Ugandans also have them. And if you lose a card then you have to go to the police at the reception. If you pay them what they want, usually about 10-20,000 UGX ($3-6), then the police will write you a letter and that letter will help you get food.

In March 2018, a refugee leader informed me that 25 (10 per cent) households in his block missed food aid during both January and February. This effectively meant that, in one block alone, 100–200 people missed food for two whole months.Footnote16 This leader also said that a similar proportion of households missed food in every block in his zone during this period, a common pattern at that time. Given this leader did not live in Zone 5A or 5B – where everyone missed food for these months – this meant another significant group who went without food.

Later, in May 2018, a different leader told me four neighbouring families returned to South Sudan in March because they could not receive food. Some of these people had since died. He explained that such movements only occurred because of corruption:

There are issues of lost cards. Sometimes the real cards are detained by the registration officers in OPM. Then they sell them. You buy those cards for UGX 50,000 (US$13). Same with attestation formsFootnote17. You can buy them in villages, at the markets. And some of the cards OPM provided were fake, so they could sell the real ones. Then when you go for food, they say those are fake and retain them and ask money to get real cards. And you need those cards for food, so what can you do?

But when the scandal came [in early 2018], they realised they would be caught, so they started detaining fake cards during distribution, because they knew it would show evidence – you know, in Uganda they say to win a case you must destroy the evidence. So, OPM burnt those ration cards. I saw them myself, two whole boxes full were detained in a single day at February food distribution, and they just burnt them in front of everyone. Because they knew, once destroyed, even though saw there was nothing we could do (Refugee leader #2, May 2018).

This account was confirmed by a third leader who witnessed the OPM’s card burning exercise. He explained that missing food was due to corrupt registration processes which allowed anyone to pay to become a refugee. According to him, although some extra registrations were wealthy refugees who purchased additional documents to access distributions, most were Ugandans. In fact, his Ugandan neighbours had shown him proof of doing this: after paying OPM staff UGX 50,000 ($13) in April 2017, they were registered as refugees and received the registration forms allowing them access to food during every pre-BVE distribution.

However, food delivery was transformed with the completion of the BVE in June 2018, after which anyone not properly registered and verified was refused food. Unfortunately, these requirements meant many refugees remained without food because of original registration problems not rectified during the BVE. As one youth said in July 2018, ‘now they do not give food unless properly registered, and that is a problem: the OPM did not register everyone correctly, or refused to register people without payment, or took some forms and sold them. So now, because they have closed verification, you have people who cannot get food.’ That refugees with prima facie status might be denied legal resources is a significant problem: although in theory the BVE was a sound anticorruption measure, its implementation created new deficiencies, largely resulting from a loose alliance of bureaucratic organisations unaware of or unresponsive to issues with the BVE’s application.

Resisting Resilience

Organised Resistance?

Beyond simple fraud, however, are the humanitarian costs: from late 2017 to June 2018, thousands of refugees in PRS went without food because of bureaucratic failure or humanitarian corruption. In fact, the sheer scale of this might have led to riots if not for the intervention of refugee leaders: in February, the community held a large, refugee-only meeting to discuss how to respond to the issue of missing food.

People present said this meeting centred on a popular proposal for mass demonstrations, including a march along PRS’s main thoroughfare culminating in a protest at reception. This gained considerable traction among the ‘loud and angry’ crowd, who quickly decided this was their preferred action. However, two different leaders highlighted that, as authorities had already interceded violently in the settlement on a previous occasion, stopping mass demonstration was critical.Footnote18 Leaders felt any overt opposition would be seen as ‘a riot’ and violent retaliation would follow. This needed to be prevented because it would not only cause refugee injuries but would be used to invalidate their larger concerns. Thus, rather than backing a demonstration, leadership proposed an agenda of civil disengagement from non-essential (health, food, or education services) activities until distribution was reconstituted. Affected activities largely amounted to the plethora of workshops, meetings, and capacity-building exercises that formed most NGOs’ staple practices.

If reducing potential violence in a context of extreme power disparity was one reason to prefer non-violent civil disengagement, another was that leadership felt this was the most likely way to pressure NGOs into reconstituting consistent food delivery. As one leader said:

Our people were hungry. So how could we do those [NGO] things without food? You know, the only thing those organisations understand or care about are donors’ requirements. So, if there is no-one to sign the attendance sheets, no-one to say they received aid, then donors will start asking questions. Sometimes you need to go about these things softly, softly. Not reacting but thinking. That is the only power you have

After the meeting, attendees began disseminating the plan via word-of-mouth, hoping to achieve widespread community buy-in. Obviously, refugees are not a homogenous mass, despite tending to be treated as such by NGOs and settlement authorities. As with any social unit, there were dissenting views and opinions, issues of everyday interpersonal antagonisms, and larger political disagreements – especially in the civil war context. There were also issues of personal and familial need that might trump any wider community decisions. Together, such divergences meant total disengagement would always be impossible. Nonetheless, it did not have to be as long as a certain ‘critical mass’ was accomplished.

It seems critical mass was achieved: because no ‘official’ communication of the boycott was made, services largely continued as normal, with ‘community mobilisers’ informing people of upcoming events and inviting attendance. Nonetheless, NGO staff said it quickly became obvious refugees were not attending as expected and complained that, when they asked people about non-attendance, were told refugees were ‘crying with the hunger’ or ‘did not have enough energy to attend’. They further said that, although future attendance would invariably be assured, non-attendance remained a problem.

By not making official communication, the underlying logics echoed those highlighted by Scott, who argued for ‘many forms of peasant resistance, I have every reason to expect that the actors will remain mute about their intentions. Their safety may depend on silence and anonymity; the kind of resistance itself may depend for its effectiveness on the appearance of conformity’ (Scott Citation1986, p. 29, emphases in original). Nonetheless, civil disengagement allowed the community to communicate with powerholders in a way requiring neither direct dialogue nor interaction yet still providing widespread, non-threatening dissent.

As well as civil disengagement, signs reading ‘No food, No services’ and ‘No food, No entry’ demarcated some areas as no-go zones for service providers. These signs were perceived as threatening by NGOs, with several field officers saying they or their colleagues were ‘too afraid’ to enter certain areas during this period, particularly those ‘far away from reception’. As one female NGO worker said in March 2018, ‘the refugees in those places, the zones not receiving food, they are not happy. And so, even though I am supposed to work there [Zone 5], I do not go, I just stay in reception where it is safe’.

Mobile Resistance

Large-scale, organised action was not the only way corruption was resisted. Most responses were far more prosaic and immediate: while some refugees sold relief items or engaged in minimally compensated day labour, others returned to South Sudan.Footnote19 Border crossers generally travelled for three different (if connected) purposes: most wanted to access agricultural or trade opportunities (I call this ‘voluntary commuting’)Footnote20; others sought to register multiple identities (‘kubwariga’, see below); the most desperate engaged in a form of ‘survival repatriation’ (cf. O’Byrne and Ogeno Citation2020). I discuss these below. It should be noted, however, that despite being linked forms of mobility demonstrating agency, none of these are necessarily forms of either resistance or resilience. After all, as Sou (Citation2021b, p. 10) has argued, although ‘resilience and resistance are complimentary, rather than competitive … there are situations where the two concepts are irreconcilable and where resilience is the only means of survival and resistance is impossible’. For this reason, in this section I do not want to imply that all resistance is resilience or vice versa. Instead, I simply wish to describe the many mobility-based ways in which PRS residents responded to humanitarian failure. Nonetheless, although manifesting agency does not automatically entail resistance, it is certainly one pre-condition.

Survival Repatriation

Food access influences displaced peoples’ movements and food insecurity was the primary driver behind all instances of ‘survival repatriation’ I was told about (cf. Kaiser Citation2006, O’Byrne and Ogeno Citation2020, Stites and Humphrey Citation2020, Stites et al. Citation2021). Being among the community’s most vulnerable and marginalised individuals, most ‘survival repatriates’ did not return; multiple interlocutors said, for those without food, starving in Uganda was more concerning than war in South Sudan. In April 2018, for example, one man said ten households in his block had repatriated because OPM had not registered them correctly and they were not receiving food. According to him, one household said, ‘it is better to face fighting than to starve’. Although this was likely true for many ‘survival repatriates’, it was a high-risk strategy, and I heard the following in May 2018:

One woman left her husband in South Sudan to take refuge in the camp here, but she could not receive food for over two months and decided to return. Unfortunately, she died there during labour because no medical services. She would not have died from here. But maybe she would have died from hunger instead (Refugee leader #5 May 2018).

Voluntary Commuting

Nonetheless, most cross-border movements involved temporary forms of ‘voluntary commuting’ lasting several days oriented towards maximising settlement-based wellbeing through trade or agriculture. A common practice across the whole physically able demographic spectrum, ‘voluntary commuting’ continued patterns of refugee household dispersal seen during earlier displacements (Hovil Citation2010) and was used to supplement often-inadequate aid and provide access to items not included within most distributions, like medicines, clothing, and hygiene products. Such cross-border visits were not strictly legal, and commuters risked being refused re-entry to Uganda. Most refugees I spoke with felt the real risk of refusal was negligible, however: if discovered, a bribe would be demanded, and their journey could continue.Footnote21

While it is debatable if ‘voluntary commuting’ necessarily demonstrates a form of resistance, as agency is a pre-condition for resistance, such mobilities are definite signs of refugees’ ongoing, active agency. Mobility also shows the significance many refugees placed on not being dependent upon aid, a significant factor given its inconsistent distribution. Indeed, if – as I argue – refugees’ experiences showed the inherent unreliability of food distribution, then establishing a dependency relationship would demonstrate lack of resilience. Refugees’ mobilities then not only signal their intentional refusal of dependency but are also exemplary forms of the exactly those resiliencies advocated by many programmers: the ‘capacity of individuals, communities and systems to survive, adapt, and grow in the face of stress and shocks, and even transform when conditions require it’ (Rockefeller Foundation Citation2017).

Kubwariga (Multiple Registrations)

Another relatively common pre-BVE mobility strategy was ‘kubwariga’, or multiple registrations (cf. Poole Citation2019, p. 19 n21). To engage in kubwariga, a refugee travelled to the South Sudanese border and presented themselves as a new person with a different name and identity. After being processed, these new identities would be relocated to a nearby settlement and, as they had generally used the closest crossing point to PRS, this was often where their new identities were resettled too.

For some, kubwariga was a deliberately repeated livelihoods strategy, and they might have several identities. However, most who engaged in kubwariga did so opportunistically or accidentally, often during voluntary commuting. In such cases, the lines between resistance, resilience, and survival become blurred, especially when these might be the unforeseen outcomes of unequal power relations at the border, like when a refugee did not have the bribe required to pass unobstructed. No matter the variation, however, the outcome was identical: a new identity, new documents, additional one-off emergency relief items (cooking utensils, solar lights, building materials, and so on), and most significantly, extra monthly food rations. Although non-food items were usually sold for additional income, extra food had multiple uses. It could supplement a household’s meagre diet or be traded or sold for other purposes: as Stites and Humphrey (Citation2020, p. 16; cf. Buchanan‐Smith and Jaspars Citation2007; Poole Citation2019; Stites et al. Citation2021) note, ‘the sale of portions of a household’s humanitarian food ration’ is probably the most common way refugees in Uganda generate income.

Refugees knew they faced sanctions if they were discovered engaging in kubwariga, although the sheer scale of the 2017 South Sudanese refugee crisis meant discovery was generally unlikely if an individual did not bring too much attention to themselves. Even then the most likely result was a bribe. Prior to the completion of the BVE in mid-2018, therefore, kubwariga was integral to the livelihood, survival, and resilience strategies of many refugees. Moreover, some people engaged in kubwariga for distinctly political reasons: they highlighted the unequal and corrupt ways humanitarian staff profited from refugees’ misfortune. In this way, many practitioners directly framed kubwariga as a form of active resistance to exploitation with no immediate losers. Nonetheless, one manifestation of the refugee industry’s inherent contradictions is that, on several occasions both before and after the BVE, I observed OPM staff tell refugees being denied food that they should return to the border to re-register if they wanted their issue resolved. Indeed, demands for re-registration were so common they seemed part of PRS’s standard operating procedure.

Whether or not they engaged in cross-border practices themselves, before the institution of BVE-related changes in June 2018, everyone agreed it was better for such activities to remain unnoticed. As Scott (Citation1986, p. 29) argues, underclass resistance is often framed to challenge repression while eluding observation and minimising the likelihood of elite repression. Many refugees expressed anxiety about the discovery of their mobile tactics of resistance and resilience: not only would authorities siphon off resources through bribes, but the practices might be stopped entirely, leaving residents without an important livelihoods source. Having said this, most humanitarian actors I spoke with not only recognised that cross-border movements took place but also noted that these were often used to establish multiple identities and access much needed additional support.

Despite such unofficial recognition, however, there are significant ethical implications in discussing kubwariga, although these are mitigated by two important factors: firstly, the BVE led to the near complete disappearance of kubwariga by July 2018. This was not necessarily seen as a problem by most refugees, however, who were happier to have reliable food distribution than engage in expensive and risky border crossings. The second reason is the time between publication of this paper and the last occurrences of kubwariga – around four to five years. Since then, refugees in Uganda have been forced to change their strategies of resistant resilience to meet new difficulties, including Covid and post-Covid forms of inequality and containment. Kubwariga has gone. Resistance-based forms of resilience, I suggest, have only adapted.

Discussion: The Politics and Practise of Resistant Resilience

Not surprisingly, many PRS residents felt cheated and abandoned during early 2018: they were facing an ongoing problem of basic existence, brought on by individual and institutional corruption conducted by the same organisations tasked with their protection, and without any obvious end. Nonetheless, as Scott (Citation1985, p. xv; Citation1986, p. 30) noted, acts of everyday resistance like those underpinning refugees’ tactics of resilience often originate in the basic fact that life goes on, and so people must continue to survive. Survival often depends on a diverse range of mechanisms to cope with the positive and negative dimensions of everyday life, and I suggest that the responses of refugee in PRS show the importance of agency and resistance in their personal and communal resilience. Both the experience of exploitation and refugees’ resistant response are highly gendered as well as unequally distributed around demographic elements such as age and education, as Stites et al. (Citation2021; cf. Stites and Humphrey Citation2020) demonstrated among refugees in Uganda’s north-west. However, the small-scale, qualitative nature of my research precludes any in-depth analysis of such information. Further research is therefore suggested into how strategies of agency, resilience, resistance, and survival are impacted by demographic dimensions such as age, education, ethnicity, and gender.

Scott (Citation1986, p. 22) defines ‘peasant class resistance’ as ‘any act(s) by member(s) of the class … intended either to mitigate or to deny claims … made on that class by superordinate classes … or to advance its own claims … vis-à-vis these superordinate classes’. In this paper I have demonstrated numerous ways the refugees living in PRS in early 2018 attempted to resist the claims of predatory and perhaps parasitic superordinate humanitarian elites. Among the more obvious acts of ‘resistant resilience’ was the settlement-wide boycott undertaken during early 2018, a strategy that not only achieved significant community buy-in but which refugees themselves considered effective.

Not all forms of ‘resistant resilience’ were as structured and co-ordinated, however, especially at the individual and household level. Those who had reliable networks used them, showing the importance of relationality in individual and communal resilience. Many people without food engaged in socially embedded survival practices: asking friends or family for loans, selling non-essential items, or approaching church or other community leaders for assistance. Some voluntarily commuted across the border to engage in the trade or farming activities while others undertook kubwariga and gathered more than one identity. A number purchased extra food or ration cards from humanitarian staff. This was just those who had the social or physical resources to buy, borrow, work for, or otherwise access food, however. Many of the most vulnerable could not, and so either starved or crossed the border as survival repatriates to scrape out a marginal existence in an active warzone (cf. O’Byrne and Ogeno Citation2020). Significantly, many of these examples demonstrate the mobilisation of two central yet under-theorised facets of resilience: agency and resistance.

Indeed, although I have noted that there needs to be a clear analytical distinction between the concepts of resilience and survival, it nonetheless seems numerous refugees’ resistant practices were undertaken to ensure survival as much as resist corruption. This, again, is discussed by Scott, who argues, “it would be a grave mistake … overly to romanticise these ‘weapons of the weak’. They are unlikely to do more than marginally affect the various forms of exploitation which peasants confront” (Scott Citation1986, p. 6). The effects of the community boycott on either the reinstitution of food or on the settlement’s real functioning remains both unknown and difficult to measure. It did not expose the scandal beyond PRS. Further, as it likely affected smaller NGO partners more than the large government and UN organisations most involved in registration and food supply failures, there is no indication it had any instrumental effect upon the resumption of food deliveries. Indeed, neither I nor the community ever knew exactly how and why food delivery restarted.Footnote22 Moreover, not only was engagement with the boycott not homogenous in its reach but its direct effects were undoubtedly differentially felt too, with the poorest and most marginalised among the community most likely to be those who lost out from the provision of services. Furthermore, the boycott also had no bearing on the BVE, which was not only already pre-planned but operated for different purposes and on a larger scale than one settlement.

Conclusion

If the crises central to contemporary resilience are really ‘the new normal’, as is often assumed, then this ‘profoundly changes the core of how humanitarian aid is conceptualised’ (Hilhorst Citation2018, p. 5). Rather than being processual, much humanitarian and development programming commonly assumes resilience is something ‘real’ that can be built, grown or acquired, something which is inherently positive and capable of targeted development.Footnote23 However, I have suggested that such a conceptualisation is especially problematic when humanitarian intervention is the origin of crisis. Indeed, I have shown that some humanitarian activities directly impact the resilience of people in negative ways. Thus, in this paper I specifically discussed South Sudanese refugees’ responses to a humanitarian-induced food crisis in PRS during 2017–18. I argued that refugees’ responses to this crisis stemmed from the basic needs of survival. I further argued that many refugees’ strategies of survival depended on individual and communal abilities to base their ‘tactics of resilience’ in appropriate acts of resistance.

I therefore demonstrated that the most obvious manifestations of resilience among PRS refugees in early 2018 involved people trying to enhance their lives despite structural and systemic failure: simple activities undertaken while attempting to get on with and improve the lives and livelihoods of themselves and their families. However, resilience and survival are not the simple equivalents humanitarian actors often consider them. For ‘resilience’ to have any meaning, the term cannot simply be reduced to mere survival, just as continuing to survive cannot be assumed to be a demonstration of resilience. Instead, I argued agency is central, both to the processes underlying being resilient as well as to those ensuring survival. I further demonstrated that agency is fundamental to marginalised people’s practices of resistance. Indeed, I have shown how everyday life in PRS often required active resistance, simply because of the ambiguities and complexities of the often-exploitative relationships within which refugees live.

For this reason, I have argued that the most important indicator of this refugee community’s underlying resilience was active resistance. Indeed, the ‘resistant resilience’ of refugees in PRS in early 2018 was most obviously demonstrated in those individual acts of agency forming a wider, if largely unstructured system of communal resistance against corruption and humanitarian failure. Indeed, I suggest that the means by which the exploited actively resist the conditions of their exploitation may be the most sustainable manifestation of marginalised people’s resilience. After all, – as Scott (Citation1986, p. 23) similarly alludes – just as acts of everyday resistance are shown through ‘an understandable desire on the part of the peasant household to survive’, so too is everyday resilience most obviously manifest by exploited peoples’ understandable desire to resist.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I want to thank the residents of Palabek Refugee Settlement for generously sharing their food, lives, and thoughts. This paper is some small attempt at recompense. I wish to thank the myriad helpful organisational staff I spoke with during out time in PRS. An early draft of this paper was presented at the 2018 American Anthropological Association conference, and I acknowledge panel organisers and attendees for their helpful feedback. Finally, I thank all reviewers formal and informal for their insightful comments. All errors and omissions remain my own. This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [ES/P008038/1] and the Rockefeller Resilience Fund in collaboration with the Institute of Global Affairs and the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa (FLIA) at The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). The support of these sources is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ryan Joseph O’Byrne

Ryan Joseph O’Byrne is a Post-Doctoral researcher in the Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa at The London School of Economics and Political Science. He holds a MA in Cultural Anthropology from Victoria University Wellington (New Zealand) and a PhD in Social Anthropology from University College London (United Kingdom). His Masters research focused on South Sudanese Acholi refugees in New Zealand while his PhD fieldwork took place in the South Sudanese Acholi community of Pajok. His most recent fieldwork investigated the connections between mobility, resilience and public authority among South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda. He has published in the Australasian Review of African Studies, Human Welfare, the Journal of Refugee and Immigrant Studies, the Journal of Refugee Studies, the Journal of Religion in Africa, Sites, and Third World Thematics. He has chapters forthcoming in the edited volumes Informal Settlement in the Global South, (Gihan Karunaratne, ed.) and Migration, Borders, and Refugees in Africa (Joseph K. Assan, ed.). Email: [email protected]

Notes

1. Following my interlocutors, I use South Sudan(ese) to refer to this area and its peoples no matter the period.

2. Although large-scale conflict ceased with the 2018 Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), peace remains fragile.

3. Although all zones should receive equitable assistance, the actual distribution of resources is more sporadic, particularly for areas such as Zones 5A/5B/6 located over 5 km from the main compound.

4. For exhaustive overviews of Ugandan refugee legislation and its national and international frameworks, including applicable definitions of ‘self-reliance’ and ‘resilience’, the reader is directed to the work undertaken by the International Refugee Research Initiative (IRRI) and the Refugee Law Project (RLP), as well as the excellent summaries provided by Hovil (Citation2018), Oliver and Boyle (Citation2020), and Titeca (Citation2021).

5. In situations of humanitarian emergency, food rations should provide populations of concern with their complete minimum nutritional needs.

6. In Ugandan parlance, ‘ghosts’ are non-persons invented for the purposes of siphoning off supplies or funds destined for others. As well as ‘ghost refugees’ discussed later, this has also affected Ugandan military, public administration, and schools.

7. These claims were acknowledged as true by The Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees, Hilary Onek (Birrell Citation2018).

8. Although most refugees received direct aid, some urban refugees were given money transfers.

9. As I show below, although the BVE stabilised refugees’ access to food aid, it simultaneously removed a host of refugees’ own resilience and self-reliance strategies.

10. For further information about refugee industry corruption in Uganda, the reader is directed to Titeca (Citation2021).

11. As most documents show refugees’ identifying details, they cannot be reproduced.

12. Following BVE completion, Zone 5A/5B had a combined population of 2,780 households and 10,106 people, around 1/3 PRS’s entire population (see ).

13. Although I do not know of any deaths recorded due to starvation, there is little doubt it contributed to some mortality among the weak and vulnerable as well as stunting and malnutrition–related disabilities in children.

14. Given the fluctuating numbers on every other document, the stability of these figures is interesting.

15. This is based on comparisons of population differences in other zones over Cycle 2 (March; ), Cycle 4 (April), and Cycle 6 (June; ). Cycle 4 documents contain identifying material and cannot be reproduced.

16. Average PRS household size in mid-2018 was 6.1 persons, ‘larger than previous assessments conducted in Uganda’ (REACH Citation2018, p. 1).

17. An attestation form is a legal identity document issued by the OPM after border processing and proving an individual’s refugee status.

18. Further information cannot be given as doing so would compromise confidentiality and safety.

19. Scott (Scott Citation1986, p. 8) observes that ‘everyday forms of resistance make no headlines’. My investigation into refugee resistance was certainly not exhaustive, and many strategies likely escaped me. Indeed, following Scott (Scott Citation1986, p. 29; cf. Sou Citation2021a, p. 6), I suggest this is the point: underclass resistance is most effective when hidden and avoiding retaliation.

20. This term was suggested by Julian Hopwood.

21. Although this would result in the loss of goods or profit, refugees generally saw these encounters as an arbitrary – if hopefully avoidable – form of ‘taxation’.

22. Although individual UNHCR and NGO staff spoke about the food crisis, to my knowledge it was not officially acknowledged.

23. What Bourbeau and Ryan (Citation2018, p. 223) call ‘a substantialist ontological position’.

References

- ActionAid, 2016. Through a different lens: ActionAid’s resilience framework version 1.0. Johannesburg: ActionAid International Secretariat.

- Bailey, S., 2008. Perceptions of corruption in humanitarian assistance among internally displaced persons in Northern Uganda. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Béné, C., et al., 2012. Resilience: New utopia or new tyranny? Reflection about the potentials and limits of the concept of resilience in relation to vulnerability reduction programmes. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Betts, A., et al., 2019. Refugee economies in Uganda: What difference does the self-reliance model make?. Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre.

- Birrell, I., 2018. The foreign aid ghost camp: Shocking investigation reveals how corrupt Ugandan officials are manipulating refugee statistics in order to con the UK out of millions. [ online]. Available from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5799355/Refugee-numbers-Uganda-fake-officials-UK-foreign-aid-budget.html [Accessed 26 March 2022].

- Bjørkhaug, I., 2020. Revisiting the refugee–host relationship in Nakivale Refugee Settlement: A dialogue with the Oxford Refugee Studies Centre. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 8 (3), 266–281. doi:10.1177/2331502420948465

- Bourbeau, P., 2015. Resilience and international politics: Premises, debates, agenda. International studies review, 17 (3), 374–395.

- Bourbeau, P. and Ryan, C., 2018. Resilience, resistance, infrapolitics and enmeshment. European journal of international Relations, 24 (1), 221–239. doi:10.1177/1354066117692031

- Buchanan‐smith, M. and Jaspars, S., 2007. Conflict, camps and coercion: The ongoing livelihoods crisis in Darfur. Disasters, 31, S57–S76. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.00349.x

- Cannon, T. and Müller-Mahn, D., 2010. Vulnerability, resilience and development discourses in context of climate change. Natural Hazards, 55 (3), 621–635. doi:10.1007/s11069-010-9499-4

- Checchi, F., et al., 2018. Estimates of crisis-attributable mortality in South Sudan, December 2013-April 2018: A statistical analysis. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Cretney, R., 2014. Resilience for whom? Emerging critical geographies of socio-ecological Resilience. Geography Compass, 8 (9), 627–640. doi:10.1111/gec3.12154

- De Waal, A., 2014. When kleptocracy becomes insolvent: Brute causes of the civil war in South Sudan. African Affairs, 113 (452), 347–369. doi:10.1093/afraf/adu028

- DfID, 2013. DfID’s anti-corruption strategy for Uganda. London: DfID.

- Evans, B. and Reid, J., 2013. Dangerously exposed: The life and death of the resilient subject. Resilience, 1 (2), 83–98. doi:10.1080/21693293.2013.770703

- Hilhorst, D., 2018. Classical humanitarianism and resilience humanitarianism: Making sense of two brands of humanitarian action. Journal of international Humanitarian Action, 3 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1186/s41018-018-0043-6

- Hovil, L., 2010. Hoping for peace, afraid of war: The dilemmas of repatriation and belonging on the borders of Uganda and South Sudan. Geneva: UNHCR.

- Hovil, L., 2018. Uganda’s refugee policies: The history, the politics, the way forward. Kampala: International Refugee Rights Initiative.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW), 2013. “Letting the big fish swim”: Failures to prosecute high-level corruption in Uganda. YaleConnecticut: New Haven.

- Ilcan, S. and Rygiel, K., 2015. “Resiliency humanitarianism”: Responsibilizing refugees through humanitarian emergency governance in the camp. International Political Sociology, 9 (4), 333–351. doi:10.1111/ips.12101

- IRRI, 2018. “My children should stand strong to make sure we get our land back”: Host community perspectives of Uganda’s Lamwo Refugee Settlement. Kampala: International Refugee Rights Initiative.

- Kafeero, S., 2018. Refugee scam: Uncertainty hangs over UNHCR boss’ job. [ online]. Available from: http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Refugee-scam-Uncertainty-hangs-UNHCR-boss-job/688334-4299452-wnhdv0z/index.html [Accessed 26 March 2022].

- Kaiser, T., 2006. Between a camp and a hard place: Rights, livelihood and experiences of the local settlement system for long-term refugees in Uganda. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 44 (4), 597–621. doi:10.1017/S0022278X06002102

- Krause, U. and Schmidt, H., 2019. Refugees as actors? Critical reflections on global refugee policies on self-reliance and resilience. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33 (1), 22–41. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez059

- Martini, M., 2013. Uganda: Overview of corruption and anti-corruption, U4 expert answer no. 379. Berlin: Transparency International.

- Neocleous, M., 2013. Resisting resilience. Radical Philosophy, 178, 2–7.

- O’Byrne, R.J. and Ogeno, C., 2020. Pragmatic mobilities and uncertain lives: agency and the everyday mobility of South Sudanese refugees in Uganda. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33 (4), 747–765. doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa085

- OCHA, 2017. Humanitarian needs overview: South Sudan. Juba: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- OIOS, 17 Oct 2018. Internal audit version, report 2018/097, audit of the operations in Uganda for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. [ online]. Available from: https://oios.un.org/ru/file/7247/download?token=48QNfXL1 [Accessed 26 March 2022].

- Oliver, M. and Boyle, P., 2020. In and beyond the camp: The rise of resilience in refugee governance. Oñati Socio-Legal Series, 10 (6), 1107–1132. doi:10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1050

- OPM and UNHCR, 2018. OPM and UNHCR complete countrywide biometric refugee verification exercise. [ online]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/press/2018/10/5bd72aad4/opm-and-unhcr-complete-countrywide-biometric-refugee-verification-exercise.html [Accessed 26 March 2022].

- Panter-Brick, C., 2002. Street children, human rights, and public health: A critique and future directions. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31 (1), 147–171. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085359

- Poole, L., 2019. The refugee response in northern Uganda: Resources beyond international humanitarian assistance. HPG Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- REACH, 2018. Uganda joint multi-sector needs assessment: Identifying humanitarian needs among refugee and host community populations in Uganda, August 2018. Geneva: REACH Initiative.

- Rockefeller Foundation, 2017. Resilience research: IGA-Rockefeller funding call – third round. [ online]. Available from: http://www.lse.ac.uk/iga/research-and-publications/rockefeller-funding-calls [Accessed 26 March 2020].

- Ryan, C., 2015. Everyday resilience as resistance: Palestinian women practicing sumud. International Political Sociology, 9 (4), 299–315. doi:10.1111/ips.12099

- Scott, J.C., 1985. Everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Scott, J.C., 1986. Everyday forms of peasant resistance. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 13 (2), 5–35. doi:10.1080/03066158608438289

- Sou, G., 2021a. Aid micropolitics: Everyday southern resistance to racialized and geographical assumptions of expertise. Environment and Planning C: politics and space, 40 (4), 1–19.

- Sou, G., 2021b. Reframing resilience as resistance: Situating disaster recovery within colonialism. The Geographical Journal, 118 (1), 1–14.