ABSTRACT

This study proposes a patterned explanation for the unequal educational achievement between Yi and Han students in China. Family backgrounds, school settings, educational expectations and aspirations are examined when investigating ethnic gaps in educational achievement. Evidence suggests significant impact of family backgrounds in shaping educational gaps, especially for the Han group. When intersecting with educational expectations, family backgrounds are more restrictive in Han students’ formation of expectations. Comparatively, educational aspirations are less restricted by family backgrounds and are strong factors in affecting Yi students’ achievement. Moreover, educational aspirations have a stronger effect on both Han and Yi students’ achievement compared to educational expectations. However, school settings when intersecting with family backgrounds are significant only in Yi students’ achievement. These findings contribute to international debates on the importance of family backgrounds, educational expectations and aspirations, and provide hints to better explain the persistent ethnic gaps in educational achievement in China.

1. Introduction

This study examines the relationships between family backgrounds, school settings, students’ educational aspirations and expectations in affecting students’ educational achievement in Liangshan, China. Here educational aspirations refer to the level of education a student hopes to achieve while expectations are referring to the level a student estimates to achieve according to the actual socioeconomic circumstances (Gorard et al., Citation2012; Khattab et al., Citation2021). Aspirations and expectations are associated with educational attainment which Gorard et al. (Citation2012) have defined as “an individual's level of success in educational assessments of any kind” (p. 5). There are, however, differences in the usage of terminology, depending on the context. In the United Kingdom, educational attainment usually refers to school performance (Baker et al., Citation2014; Croll & Atwood, Citation2013) while in the United States, educational attainment means level of schooling (Sewell et al., Citation1970; Trinidad, Citation2020) and student's “level of success in educational assessments” refers rather to educational achievement or school performance (Tsui, Citation2005). The conceptual distinction between educational attainment referring to the educational level and educational achievement indexing to school performance is useful to understand different strands of studies and to avoid any terminological confusion in the present study. In this study, the term of educational achievement is used to referring to students’ school performance.

This study draws from sociological theories on (in)equality and previous research in social stratification on how education may reproduce, contribute to, or reduce societal inequalities. Focusing on the transition rate of students successfully going on from one school level to the next level, Raftery and Hout (Citation1993) have developed the “Maximally Maintained Inequality” theory. According to this theory, political interventions of democratization or expansion of education can increase access to education and ameliorate the educational attainment of students, especially for those from lower social classes. In a similar vein, China has experienced expansions of educational opportunities under policy changes. From the foundation of People’s Republic of China (1949) to the end of the Cultural Revolution until 1981, the educational empowerment policy in favor of children of workers and peasants allowed to offer them an important number of available schools. Consequently, the rate of enrolled primary school-age children has passed from 20% to 93%, and almost every commune has its own junior high school (Deng & Treiman, Citation1997). However, the policy-promoted equality of educational opportunity often with lower quality failed to eradicate the educational inequality between different social groups which turned to exacerbate after the introduction of the market economy with the Reform and Openness policy in 1978. The following political choice to first develop the eastern part of China has further enlarged the regional disparity that the Chinese government was capable to confront only from the year of 2000 with the policy of developing the western region.

The Chinese educational expansion is characterized by regional disparity which often intersects with ethnicity. In 2000, the average years of schooling was 6.31 years for people living in the regions concentrated by minorities, especially in the western part comparing to the general level of 7.12 years in China (He & Cheng, Citation2015). This inequality of educational attainment has persisted until 2010, especially in the western regions of China. For example, in the western area of Liangshan concentrated by Yi minority, the average years of schooling was only 6.28 years, which was 2.52 years less than the Chinese average level in 2010. The sounding gaps in educational attainment have urged the governments of different levels to multiply the financial support for developing the compulsory education in Liangshan, and the average years of schooling rose to 7.19 years in 2015 (Wang, Citation2019). Yet little is known about students’ educational achievement following the political intervention of educational expansion while an important body of literature in diverse contexts has shown the influence of family backgrounds, parental involvement, parental aspirations, and school settings in children's educational achievement (Wang & Lehtomäki, Citation2022; Croll & Atwood, Citation2013; Hannum, Citation2002, Citation2009; Hong, Citation2010, Citation2020; Strand, Citation2011; Xie & Postiglione, Citation2016). This paper aims to examine the associations between these key elements and to assess how they contribute to affect students’ educational achievement in Liangshan. The research on these associations in transitional China is crucial because it provides evidence to explain the persistent ethnic gap in educational achievement that political intervention of education expansion failed to bridge.

2. Theoretical frame

2.1 Students’ socioeconomic backgrounds and forms of capital

This study's theoretical frame builds on Bourdieu’s (Citation1985) and Coleman’s (Citation1988) theories on different forms of capital that potentially influence educational aspirations, expectations, and achievements. Their views, however, differ on how the forms of capital influence. Bourdieu (Citation1985) distinguished three forms of capital: economic capital, cultural capital, and social capital, in understanding the reproduction of social classes. Coleman (Citation1988) focused rather on the relationships between children's family backgrounds and school achievement in examining the three components of family backgrounds: financial capital, human capital, and social capital. Coleman (Citation1988) conceptualised the financial capital as the family's wealth or income, the human capital as parents’ education and the social capital as the intimacy of family relations between adults and children (p. S110). Croll (Citation2004) argued that Coleman's conceptual distinction of capital is to understand the achievement gaps between children from diverse family backgrounds, while Bourdieu’s (Citation1985) reflections on cultural capital originated from the “unequal scholastic achievement of children from different social classes” (p. 47) with the aim to understand the mechanisms of how middle and upper classes ensure their reproduction of capital. Secondly, Bourdieu (Citation1985) considered the social capital as connections endowed by cultural and economic capital (p. 54). This understanding departs from that of Coleman (Citation1987) who considered the social capital as the range of exchanges that children could have with adults of the family and the community (p. 37). According to Coleman's definition, working-class families are in the possession of social capital as well. Thirdly, Bourdieu (Citation1985) argued that the three forms of capital could be conversed to ensure the reproduction of capital, while for Coleman (Citation1988), the human capital of parents could be ineffective in children's school achievement if the family social capital is absent (p. S110).

These theoretical conceptions of capital have triggered multiple operationalisations of family backgrounds in empirical studies. For example, the father's occupation, parental education, and the rights to free school meals are frequently used to measure family backgrounds (Croll & Atwood, Citation2013; McCulloch, Citation2017; Portes et al., Citation2013; Rothon et al., Citation2011; Strand, Citation2011). In addition to these socioeconomic indicators, Teachman (Citation1987) suggested the inclusion of educational resources substantiated by cultural items such as reference books, dictionary or encyclopaedia in measuring students’ family cultural capital. This approach is widely adhered by scholars expanding the range of cultural items to different kinds of leisure activities such as playing a musical instrument or reading (Khattab et al., Citation2021; Long & Pang, Citation2016). To measure the family social capital, Khattab et al. (Citation2021) developed a parent support scale focused on the intensity of parental supportive behaviour in children and parental exchanges. In this study, the assumption is that family backgrounds influence students’ educational expectations, aspirations, and achievements.

2.2 Students’ educational expectations and aspirations

Educational aspirations are widely explored to examine the relationship with educational attainment and achievement. Sewell et al. (Citation1969) were pioneers in including students’ educational aspirations as a mediator to extend Blau and Duncan’s (Citation1967) occupational status attainment model, which was essentially based on the structural factor of socioeconomic status. Thereafter, researchers contribute in different ways to study the mediate effect of educational aspirations on educational attainment and achievement (Bozick et al., Citation2010; Croll & Atwood, Citation2013; Feliciano & Rumbaut, Citation2005; McCulloch, Citation2017; Rothon et al., Citation2011; Wang & Shi, Citation2014). For instance, Croll and Atwood (Citation2013) singled out the structural constraints that resulted in the difficulties to fulfil educational aspirations by students from disadvantaged social backgrounds in comparison to peers from higher social classes. McCulloch (Citation2017) pointed out the cumulative effect of aspirations, which was tightly related to an individual's educational achievement and limited by social circumstances in different periods of one's life course. These studies have highlighted the intersection of educational aspirations with socio-structural factors.

Meanwhile, a body of literature has conceived educational aspirations as different from educational expectations in affecting students’ educational achievements. For example, Feliciano and Rumbaut (Citation2005) summarised two views of expectations within the status attainment paradigm. Firstly, “expectations are essentially achievement ambitions, and therefore a psychological resource that individuals draw upon to decide upon further schooling” Secondly, “expectations are realistic calculations of the prospects for future education” (p. 1088). To further this idea, Portes et al. (Citation2013) distinguished the “realistic” educational expectations from the “ideal” educational aspirations. Recently, Khattab et al. (Citation2021) succeeded in determining the superiority of educational aspirations in affecting students’ educational achievement compared to educational expectations.

The importance of intersectionality is also evident in research on the variation of aspirations along ethnic and gender lines (Feliciano & Rumbaut, Citation2005; Kao & Tienda, Citation1998; Portes et al., Citation2013; Rothon et al., Citation2011; Strand, Citation2011). Previous literature indicates that ethnic groups differ not only in educational aspirations but also in the ability to translate aspirations into concrete educational achievement (Croll & Atwood, Citation2013; Hanson, Citation1994; Kao & Tienda, Citation1998; Portes et al., Citation2013; Strand, Citation2011).

In the Chinese context, the institutional rural-urban divide is often proven to be consequential in affecting children's educational achievement (Hannum, Citation2002; Hong, Citation2010). And from the beginning of this century, scholars have called for attention to the values of ethnicity as an independent factor in explaining inequality in schooling (Hannum, Citation2002; Hong, Citation2010). Hannum (Citation2002) pointed out the effect of family socioeconomic backgrounds in shaping the ethnic gap in education. Nearly a decade later, the effects of rural-urban registrations and family socioeconomic backgrounds remained, but the patterns of “inter-generational education reproduction” were claimed to differ between the majority Han and minorities (Hong, Citation2010). In concrete, Hong (Citation2010) found that Han group's inter-generational education reproduction was produced by “resource transfer and cultural reproduction”, while only “resource transfer” was practiced by parents of minority students in supporting children's schooling. The impact of educational aspirations on educational achievement is also widely explored (Baker et al., Citation2014; Khattab et al., Citation2021; Portes et al., Citation2013; Rothon et al., Citation2011; Strand, Citation2011). Focused on rural Gansu Province in China, Hannum et al. (Citation2009) pointed out the importance of parents’ aspirations and attitudes on children's educational success. While recent studies either showcased rural parents’ lack of competence and social capital to get involved in schools and support their children's educational achievement (Xie & Postiglione, Citation2016) or rural minority parents’ disenchantment with education (Hong, Citation2020). Similar evidence about the desire for living as migrant workers was noted during our interviews with Liangshan Yi pupils and their parents in 2016, but less is known about the associations between family socio-economic status, educational aspirations and children's educational achievement in this region, categorized as in deep poverty with high rurality and dense population of Yi minority (Li & Geng, Citation2018).

2.3 The particularity of school settings in Liangshan

School settings in Liangshan have been segregated according to the publics that they serve. From the 1950s onwards, a minzu educational system for minority students was established in China in parallel to the mainstream educational system (Ma, Citation2019). However, under the movement of Great Leap Forward (1958–1961) and Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the mother tongue education in Liangshan was cancelled. In the 1980s, minority bilingual education system was reintroduced in Liangshan under two models. In model 1 schools, the Yi language is the medium of instruction (MoI) and Mandarin is a subject; in model 2 schools, Mandarin is the MoI and the Yi language is a subject (Wang & Lehtomäki, Citation2022). However, the waning interest in Yi language education and constant unequal development between two models of bilingual school has incited some scholars to consider the language differences between mother tongue and language of instruction to be one reason of Yi minority's lower educational achievement, and to criticise the domination of Chinese Mandarin in the mainstream and bilingual educational systems and its power to sanction access to quality education (Ding & Yu, Citation2013; Zhang & Tsung, Citation2019). Others have singled out the malfunction of minority bilingual education in effectively ameliorating the Yi minority's learning outcomes (Wang, Citation2018; Ding & Yu, Citation2013; Rehamo & Harrell, Citation2018). Our recent findings (2021) provided evidence on a patterned relationship between school settings and Liangshan Yi minority students’ educational achievement. However, no evidence is yet available to suggest how school settings relate to the educational achievement of both Han and Yi students in Liangshan. This study set to compare the differences between school settings, educational expectations and aspirations in affecting in Liangshan Han and Yi students’ educational achievement.

3. Conceptual model and research questions

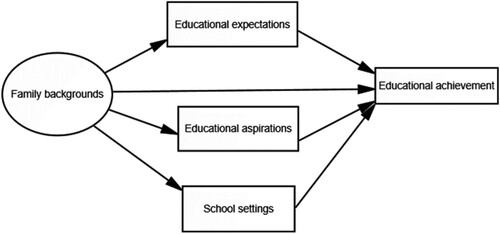

Drawing on the previous research findings, the conceptual model () was developed to depict the assumed connections and pathways between family backgrounds, educational expectations and aspirations, school settings, and educational achievement among Yi and Han students in Liangshan.

To further explore the conceptual model, the following three research questions were defined:

Do the minority Yi and the majority Han students differ in their educational achievement? If yes, how?

How do family backgrounds, school settings, students’ educational expectations and aspirations influence students’ educational achievement?

How do family backgrounds intersect with school settings, students’ educational expectations and aspirations to influence students’ educational achievement? Do these inter-relationships vary by ethnicity?

4. Methodology

4.1 Data

The data for this study is part of the survey collection that the first author led in 2017 on Liangshan Han and Minority Students’ Educational Achievement. The survey research examines factors affecting Liangshan Han and Yi ninth-grade students’ educational achievement. To include the institutional factor of school settings, the minzu-stream and mainstream schools were jointly sampled with the consent of the Liangshan educational authority. The research team randomly selected ten schools which consisted of five bilingual schools, including two Model 1 and three Model 2 schools located in Xichang city and Xide county seats and suburbs, and five mainstream schools that we named as Chinese-only schools, since minority language teaching is not available in mainstream schools. For data collection, teachers have briefly introduced the research team to students and left two lessons of 45 min under our responsibility for this survey. A total of 1,200 questionnaires and level-adapted tests in Mandarin and mathematics were distributed at the same time in the classrooms by researchers without the presence of teachers. The released China-Chinese for student questionnaire of PISA 2015 was referred with the authorization of the OECD (OECD PISA, Citation2015 Database). Of those questionnaires and performance evaluations, 1,179 were returned with 1 non-responded non-valid questionnaire. After its deletion, our sample was reduced to 1,178. The data used in this paper are based on the students’ self-reported information obtained from the survey, and thus the data on the students’ parents/family socioeconomic status is only indicative and to be interpreted with caution. However, the information is supported by references to available demographic data.

4.2 Statistical analysis

As already noted in the literature, ethnicity is claimed to be an independent factor in understanding educational gaps. In this study, the IBM SPSS Statistics is used to perform the independent sample T-test to check out the (non)existence of educational achievement gaps between Yi and Han groups. Followed with a hierarchical multiple regression model to assess the ability of different factors such as family backgrounds, school settings, students’ educational expectations and aspirations to predict students’ educational achievement after controlling for the socio-demographic characteristics of ethnicity, age, gender, and residence (Pallant, Citation2020). It is important to note that although the hierarchical multiple regression model can predict the correlation between sets of variables and the outcome variable, it cannot give information on the associations between these sets of variables. To have a more succinct model stating the causal process leading to the gaps in educational achievement, the structural equation modelling performed by Amos Graphical approach is adopted (Portes et al., Citation2013) The missing data in the hierarchical multiple regression analysis and structural equation modelling were included by using multiple imputations (Baker et al., Citation2014).

4.3 Variables

The outcome variable is students’ educational achievement, which is the sum of scores in mathematics and Mandarin. In the Chinese educational system, access to education and to quality education in the post-compulsory education stage depends mostly on scores obtained in selective entrance examinations (Zhang & Tsung, Citation2019). Educational achievement here is measured by excerpts from a prefecture-level eighth-grade standardized final test on Mandarin and mathematics provided by the research team after consulting the subject teachers. Official final examination results are not used since no uniform tests are practiced in Liangshan before the general entrance examination for senior secondary schools. In the sample, the average of educational achievement is 19 points with a standard deviation of 13.5 within the range from 0 to 45 points (). The explanatory variables include age, gender, ethnicity, residence, father's profession, father's education, family durable purchase, family educational resources, parental involvement, school settings, educational expectations, and educational aspirations.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

4.3.1 Demographic variables

Compared with the demographic distribution in Liangshan in 2014 (LSY, Citation2015), the percentages of rural students (83.80%) sampled are close to the rural population (88.1%) distributions in Liangshan. The percentage of Yi students sampled (67%) is slightly higher than the Yi population (51.7%). The distribution of gender with 50.7% of male is near to the 51.4% of male in Liangshan. In general, the demographic distribution of the sampled students is approximately representative of the Liangshan population. Age has a mean of 15.24, a standard deviation of 1.25 and ranging from 12 to 21. The 3.9% of students aged between 18 and 21 in the ninth grade is the result of the strict implementation of compulsory education in Liangshan where the previous dropped-out are required to return to school for accomplishing the compulsory education.

4.3.2 Family backgrounds

Financial capital. In the high-rurality Liangshan area, most parents are peasants or labour workers with a relatively low level of education. To get a more reliable measure of family financial capital, the family durable purchase is included because many people have little access to cash income (Zhang et al., Citation2007). A total of 14 items such as a TV, a computer, a microwave, a shower, a vacuum cleaner, a car, and a flushing toilet are included to measure family financial capital. Cronbach's alpha is 0.87 which is higher than the acceptable values of 0.7, and this measure is considered as with good internal consistency (Pallant, Citation2011, p. 100). The average of those items is used in the following data analysis. The mean of the family durable purchase is under the average (1.59) with a standard deviation of 0.40. Students were asked to describe their father’s profession in short sentences. The researcher coded the responses into the seven Chinese official profession categories (Ma, Citation2013) and then regrouped them into three groups of professions: peasants and labour workers (73.7%), merchants and clerks (17.7%), and professionals and administrators (8.6%).

Human capital. Father's education is adopted to measure the human capital with a five-point scale ranging from no schooling, primary school, junior high school, senior high school or vocational school to higher education. Nearly 82% of the sampled students’ fathers have never attended school or have only achieved the compulsory education level. 10.9% have attended senior high or vocational high school and only 7% have higher education level.

Cultural capital. Despite the high rurality in Liangshan, consuming symbolic cultural resources has gained popularity in families with good economic circumstances. The 13 items related to family educational resources include a table, a room, a quiet place to study, readings, poems, reference books, dictionaries, computer, educational applications, artwork, readings on technology and art, music and design, and a piano or violin. The mean of family educational resources measuring cultural capital is 0.45, with a standard deviation of 0.26, and with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.84. The average of those items was used in the following data analysis.

Social capital. Parental involvement is used to measure the family social capital in the sense defined by Coleman (Citation1988). In this study, students were asked to report their perceptions on the parental involvement in their schooling which consist of 9 questions such as “my parents are interested in my school activities”, “my parents require me to finish my homework”, “my parents encourage me to be self-confident”, “my parents care about my relationship with teachers and peers”. The mean of this variable is 2.98, and a standard deviation of 0.44, with a range from 1 to 4. Cronbach alpha is 0.82. The average of those items was used in the following data analysis.

4.3.3 School settings

The ten schools are sampled in Xichang and Xide with a rurality of 68.9% and 91.3% (LSY, Citation2015). In Liangshan, three school settings exist in parallel, namely Chinese-only schools, model 1 bilingual schools and model 2 bilingual schools. This paper focuses on the ninth-grade students in the last year of junior high schools. Model 1 bilingual junior high schools are mandated to recruit model 1 primary graduates in administered districts. Model 2 junior high schools should enrol students in local school districts, but with a quota limit, they have priority to recruit the top achieving rural primary school graduates either from the entire prefecture or from the whole county when they are county-affiliated model 2 schools. Chinese-only junior high schools’ enrolment is tightly related to local school district. According to local reputation, three school settings are coded as an ordinal variable: 1 = model 1 bilingual schools (20.4%), 2 = model 2 bilingual schools (29.5%) and 3 = Chinese-only schools (50.1%).

4.3.4 Educational expectations

Students’ educational expectations are measured by a series of items provided under the question: “You will soon pass the final examination of junior high education, how do you agree with the following statements?” and they were answered on a four-point scale (reverse coded to: 1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = disagree and 4 = strongly disagree). These items are related to students’ perceptions of family socioeconomic situations, parental expectations, and their own school performance. For example, “My family is poor, and my parents ask me to work as early as possible”, “My family is poor, and I want to work as early as possible to lighten the burden for my parents” and “My school performance is poor, and I cannot be recruited for senior high school”. Scores for each student respondent consist of the addition of scores on each of the items, and further divided by the number of items for facilitating the interpretation of these scores. And the mean of 3.15 is obtained with a standard deviation of 0.53 within the range from 1 to 4. Cronbach alpha is 0.77.

4.3.5 Educational aspirations

Students’ educational aspirations is measured by the following question: “What is the highest level of education that you aspire to?” and it was answered on a five-point scale (1 = compulsory education, 2 = vocational high school, 3 = academic senior high school, 4 = higher education of three years and 5 = higher education of four or more years). 88.2% of students have aspiration to higher education, and among them 55.8% for a university of four years or more and 26.4% for a three-year college. Only 2.8% of students expressed aspirations to compulsory education, while 4.3% expressed aspirations to vocational secondary schools compared to 10.6% aspired to general secondary schools.

5. Results

5.1 Educational achievement gaps between the Yi minority and the Han majority

We determine the influence of ethnicity in students’ educational achievement by comparing the Yi minority and the Han majority students’ educational achievement. An independent-samples t-test was used to compare the educational achievement for Yi and Han students. There was a significant difference in educational achievement between Han students (M = 21.52, SD = 13.93) and Yi students (M = 17.77, SD = 13.02; t (700) = 4.36, p< 0.001, two-tailed), and Han students significantly overachieve Yi peers. However, the eta squared values of 0.016 suggest a rather moderate effect size of ethnicity (Pallant, Citation2011, pp. 242–243). That is to say, only 1.6 percent of the variance in educational achievement is explained by ethnicity. To identify factors that resulted in the unequal educational achievement between Yi and Han students, we further explore in step students’ family backgrounds, school settings, educational expectations and aspirations after controlling for demographic variables.

5.2 Determinants of students’ educational achievement

presents in step the influences of family backgrounds, school settings and students’ educational expectations and aspirations on their educational achievement after the demographic variables which are crucial in understanding educational gaps in China. The hierarchical multiple regression results in (Model 1) provide strong evidence to confirm disparities in educational achievement by ethnicity, explaining 1.9% (R2) of its variance, F (1, 1172) = 23.34, p<0.001. In model 2, the entry of demographic variables of age, gender and residence has explained an additional 5.9% of the variance in educational achievement, F (3, 1169) = 25.06, p<0.001. Evidence suggests that age is negatively associated with educational achievement at the 0.05 level. There is also evidence that females overachieve male students at the 0.05 level. Among these demographic variables, the rural-urban divide is the most determinant (standardised β = 0.20, p<0.001), suggesting urban students’ better performance than rural peers. In contrast, the influence of ethnicity turns to be non-significant in explaining students’ educational achievement when the three other demographic variables are controlled for.

Table 2. Hierarchical multiple regression for educational achievement.

The entry of variables measuring family backgrounds (Model 3) explains an additional 7.6% of the variance in educational achievement F (5, 1164) = 20.77, p<0.001, while the indicator of residence becomes non-significant, the relation with age is significant at the 0.1 level, and the achievement between Yi and Han students is always non-significant but reversed. In contrast, females keep overachieving males. There is evidence that student-reported father's education and parental involvement are positively associated with the students’ achievement. Strong evidence suggests the positive influence of family educational resources on children's achievement. In other words, the disparity in educational achievement between rural and urban students relates more to family human capital, cultural capital and social capital rather than the simple residential location. Among these variables measuring family backgrounds, the effect of the cultural capital seems to be the strongest (standardised β = 0.28, p<0.001).

School settings seem to have significant influence on students’ educational achievement. Yet, the effect size is relatively small, since the entry of school settings in Model 4 explains only an additional 0.5% of the variance in educational achievement, F (1, 1163) = 6.74, p<0.05. However, when school settings are controlled for, there is very weak evidence that Yi students overachieve Han peers (standardised β = −0.60, p<0.1). In contrast, educational expectations and aspirations have explained a further 19.5% of the variance in educational achievement, F (2, 1161) = 175.07, p<0.001 (Model 5). Clearly, the effect of educational aspirations is stronger (standardised β = 0.36, p<0.001) than that of educational expectations (standardised β = 0.21, p<0.001) in influencing educational achievement. But strong evidence suggests that both are positively associated with educational achievement after controlling for students’ family backgrounds, school settings and demographic characteristics.

Overall, our model explained 35.3% of the variance in the students’ educational achievement, and the impact of the sets of predictors included in the different models is statistically significant. The most important predictors are the students’ educational expectations and aspirations, rather than family background, school settings or demographic characteristic. However, it is noteworthy that female students always overachieve male peers in different models, including in the final model where all the other sets of predictors are controlled for.

5.3 A synthetic model of factors impacting student's educational achievement

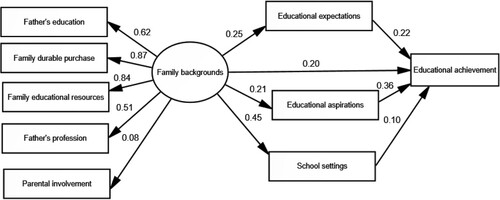

The hierarchical multiple regression in the previous section has not only shown the relationships between different sets of predictors and educational achievement, but also the relative contribution of each variable constituting the full model (Pallant, Citation2011). However, this method cannot tell the casual link between predictors in affecting educational achievement. For this reason, the structural equation modelling is used in this final section to show the pathways and effect size of each factor in predicting students’ educational achievement. The values of RMSEA (0.058) and CFI (0.902) suggested the good fitness of our model (Byrne, Citation2016; Kline, Citation2015). In , most of the factor loadings are superior to 0.5 and significant at the 0.05 level, suggesting the validity of the indicators in measuring the latent variables. However, the relative weakness of student-reported parental involvement in predicting educational achievement (0.08) needs to be ameliorated and parents’ responses can be included in further studies.

5.3.1 Determinants of educational achievement: analyses of the pathways and effect size

In general, the structural equation model has explained 20.6% of the variance in school settings, 6% of the variance in the students’ educational expectations, 4.3% of the variance in educational aspirations and 31.6% of the variance in the educational achievement.

Corresponding to the theoretical frame and assumptions, and as shown in , the differences in family backgrounds are found to directly impact on educational achievement and to interact with school settings, educational expectations and aspirations to produce inequalities in students’ educational achievement. As shown in , strong evidence suggests that students with better family backgrounds experience higher educational expectations and aspirations. Family backgrounds explain 6.2% of the variance in educational expectations (standardised β = 0.25, p<0.001), and 4.4% in educational aspirations (standardised β = 0.21, p<0.001). These results correspond to previous findings suggesting the higher impact of family backgrounds on educational expectations compared to aspirations (Baker et al., Citation2014; Khattab et al., Citation2021). Similarly, family backgrounds are significantly associated with school settings that students chose to attend and explain 20.3% of the variance in school settings (standardised β = 0.45, p<0.001). That means the better the family background is, the less probable the model 1 bilingual schools are chosen.

The standardised total effects (STE), that is the sum of the direct and indirect effects, are then used to compare the effect size of each factor on educational achievement. According to results in , the impact of family backgrounds on educational achievement is among the highest (STE = 0.37) explaining 13.7% of its variance. Educational aspirations have followed (STE = 0.36) and explained 13.0% of the variance in educational achievement. The accountability of educational expectations is smaller (STE = 0.22) compared to that of educational aspirations and explains 4.8% of the variance in educational achievement. The impact of school settings is the smallest (STE = 0.10), explaining only 1.0% of the variance in educational achievement.

Table 3. Standardized total effects of different factors on educational achievement.

5.3.2 Querying ethnic disparities in educational achievement

To understand the educational disparity between the Yi minority and the Han majority is the central concern of this study. The independent-samples t-test in previous section has already shown a significant educational achievement gap by ethnicity. To discern the influence patterns on Yi and Han students’ educational achievement, the same conceptual model is run separately for these two groups.

Results in suggest that firstly, the impact of family backgrounds on educational achievement is significant both for Yi and Han students. The standardised total effect of family backgrounds, however, explains 31.4% of the variance in Han students’ educational achievement (STE = 0.56) compared to 6.8% in Yi students’ (STE = 0.26). In other words, the impact of family backgrounds on educational achievement is much stronger for Han students than for Yi students. Secondly, the students’ educational expectations and aspirations both significantly relate to Yi and Han students’ family backgrounds. Yet Yi students’ educational expectations and aspirations are less restricted by family backgrounds in contrast to Han peers. Moreover, the effects of educational expectations on achievement seem stronger for Han students than for Yi students and explain 5.8% of the variance in educational achievement for Han students in contrast to 3.6% for Yi students. The impact of educational aspirations is relatively less affected by family backgrounds, and stronger in affecting Yi students’ achievement explaining 14.4% of its variance compared to 9% for Han students. Thirdly, strong evidence suggests the impact of family backgrounds on school settings for Yi students, yet no significant relation is found for Han students. In the same way, school settings significantly influence Yi students’ educational achievement and explains 1.4% of its variance, yet no significant impact is observed for Han students.

Table 4. Standardized total effects of different factors on educational achievement by ethnicity.

In brief, family backgrounds are strongly predicative in the Han students’ educational expectations which subsequently influence their educational achievement. However, family backgrounds are significant only in predicting school settings that the Yi students attend, which means that school setting is an impact factor of Yi students’ educational achievement. The students’ educational aspirations seem to be more determinant for Yi students’ educational achievement than for the Han students’ achievement.

6. Discussions

This study examined different factors affecting students’ educational achievement in Liangshan. The data analysis suggests important ethnic gap in educational achievement with the Han students outperforming the Yi counterparts. This finding confirms earlier research about the independent values of ethnicity in explaining educational gaps in China (Wang, Citation2018, Citation2019; Hannum, Citation2002; Hong, Citation2010; He & Cheng, Citation2015). However, our finding suggests a relatively weak effect of ethnicity itself in determining the educational achievement gap between Yi and Han students. A more complex pattern appears when the predictors of family backgrounds, school settings, educational expectations and aspirations are included.

Firstly, family backgrounds are found to significantly affect the educational achievement of Yi and Han students but in different ways. Apparently, family backgrounds account more in the intergenerational education reproduction for the majority Han students than for the minority Yi counterparts. However, the influence of family backgrounds has different pattern to Hong’s (Citation2010) study. Hong’s (Citation2010) finding suggested “resource transfer and cultural reproduction” in the Han group's inter-generational education reproduction while only “resource transfer” was in practice for minority students. In our study, both Han and Yi groups’ inter-generational education reproduction is realised by “resource transfer and cultural reproduction”, because financial capital and cultural capital () are both important factors in accounting for Han and Yi students’ family backgrounds. However, our study shows strong evidence on the impact of parental involvement in measuring Han students’ family backgrounds, yet this factor is inefficient in explaining Yi students’ family backgrounds. According to Coleman (Citation1988), if the parental involvement is absent, parents’ education could be ineffective in children's school achievement. In consequence, we could conclude that parental involvement is the main factor explaining the unequal effect of family backgrounds in affecting Han and Yi students’ educational achievement in Liangshan. The unequal power of family backgrounds in producing ethnic gap in educational achievement is equally evident when they are in intersection with educational expectations. When being from lower family backgrounds, Han students’ educational expectations seem to be more restricted than Yi counterparts’.

Secondly, educational aspirations are predominant in affecting Yi but not Han students’ educational achievement. Although both educational expectations and aspirations are found effective in influencing students’ educational achievement, it seems that educational aspirations are less restricted by family backgrounds (Baker et al., Citation2014; Khattab et al., Citation2021). Although our study is not longitudinal to demonstrate a probable downward adjustment of educational aspirations as suggested by other studies (Baker et al., Citation2014; McCulloch, Citation2017), evidence does confirm the positive effects of educational aspirations in determining the 9th grade disadvantaged Yi minority students’ educational achievement. Yi students’ educational aspirations are probably sustained through the inter-generational transmission of “concrete attitudes” concerning returns on education. For example, when asked about the expectations on children's learning in our interviews, Yi parents did always say that “only if they can be enough literate in Mandarin to find a job as migrant workers”. Similar evidence was found by Mickelson (Citation1989) in explaining women's achievement in the US regarding the predicting effect of “concrete attitudes” on achievement. The multiple educational empowerment measures administered for minority students in Liangshan could be source of aspirations for Yi minority students as well. The de-poverty discourses in Chinese Liangshan area describing education as upward mobility ladder (for example, “one undergraduate could change the fate of the whole family”) could be sources of motivation for Yi minority students who believe that they can change their fate by succeeding in the selective educational system. However, these administrative empowerment measures promoted as for minorities could hardly be source of aspirations for the Han majority students in this area.

Thirdly, the focus on the school settings in Liangshan minority area helps us to establish some evidence about the effects of the dual minzu-stream and mainstream school system in affecting students’ achievement. In line with previous findings (Wang & Lehtomäki, Citation2022; Ding & Yu, Citation2013; Pan, Citation2017; Zhang & Tsung, Citation2019), the present study showcases that school settings, when intersecting with family backgrounds, are significant in affecting the Yi minority's achievement but not significant in affecting the Han students’ educational achievement. This finding is meaningful for two reasons: firstly, although the minzu-stream school settings are administered in the favour of Yi minority, it contributes de facto to increase the educational gap within the Yi minority group. Secondly, Han students from similar lower family backgrounds are let alone despite of their low educational achievement.

There are some limitations in this study. As our data are collected from schools, the dropped-out students are not included in this sample. For this reason, we ignore the social characteristics of these students and their educational expectations and aspirations. In further studies, collecting this information could certainly enrich our understanding in explaining the educational achievement gaps by ethnicity in Liangshan. In our data, the student-reported parental involvement measuring students’ social capital is relatively weak in predicting Yi students’ educational achievement. However, the study of Xie and Postiglione (Citation2016) based on parent interview data in a Chinese county did showcase the relationship between rural parents’ involvement in children's schooling and the differential contribution to school success. More qualitative studies are needed in further research to understand the patterns of parental involvement in Liangshan and its relationship with children's educational achievement.

7. Conclusions

This study focuses on explaining the educational achievement gaps between Yi and Han students in Liangshan rather than their school-level attainment. This present study finds important gaps in educational achievement by ethnicity. Strong evidence suggests the outperformance of Han students in comparison to Yi counterparts. The subsequent inclusion of family backgrounds, school settings, educational expectations and aspirations provides more insights in explaining the ethnic gap in educational achievement. The evidence provided here suggests that students’ educational expectations and aspirations do matter in influencing their educational achievement. It seems that both educational expectations and aspirations are strongly restrained by family backgrounds. Comparatively, educational expectations are more determined by family backgrounds and have less impact on students’ achievement than educational aspirations. In contrast, students’ educational aspirations are relatively less restricted by family backgrounds but strongly important in affecting Yi minority students’ educational achievement compared to Han counterparts. School settings are in intersection with family backgrounds as well, but its effect is significant only for the Yi minority's achievement.

The findings in this study have potential implications for education policy and planning. Firstly, reducing family socioeconomic inequality in Liangshan is necessary to ameliorate both Yi and Han students’ educational achievement. Particular attention could be paid on the majority Han from lower family backgrounds since the effect of family backgrounds on Han majority's educational achievement is paramount. Secondly, equal distribution of educational resources among different school settings would be beneficial for further ameliorating the Yi minority's educational achievements, especially for those from disadvantaged socioeconomic background. Furthermore, increasing parental involvement in children's learning, and raising students’, especially Yi students’ educational aspirations could be beneficial to their educational achievement. This study focuses on Yi and Han groups in Liangshan area, the findings could hardly be generalised to other populations in the national or international scale. However, our findings will enrich the international studies on the relationships between family backgrounds, educational expectations, educational aspirations, school contexts and educational achievement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lijuan Wang

Lijuan Wang is senior research fellow in the University of Oulu in Finland. She received her Ph.D. from University of Paris Diderot in France in 2014 for a dissertation on Chinese Yi minority's education. From 2015 through 2018 she was Associate Professor at Sichuan University, Chengdu.

Elina Lehtomaki

Elina Lehtomäki is Professor of global education at University of Oulu in Finland. She is specialized in global education and learning, social meaning of education, equity and inclusion in and through education, cross-cultural collaboration, and internationalization in higher education.

References

- Baker, W., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E. C., & Taggart, B. (2014). Aspirations, education and inequality in England: Insights from the effective provision of pre-school, primary and secondary education project. Oxford Review of Education, 40(5), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.953921

- Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure. Wiley.

- Bourdieu, P. (1985). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

- Bozick, R., Alexander, K., Entwisle, D., Dauber, S., & Kerr, K. (2010). Framing the future: Revisiting the place of educational expectations in status attainment. Social Forces, 88(5), 2027–2052. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0033

- Byrne, B. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Coleman, J. S. (1987). Families and schools. Educational Researcher, 16(6), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175544

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital and the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Croll, P. (2004). Families, social capital and educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Studies, 52(4), 390–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2004.00275.x

- Croll, P., & Atwood, G. (2013). Participation in higher education: Aspirations, attainment and social background. British Journal of Educational Studies, 61(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2013.787386

- Deng, Z., & Treiman, D. J. (1997). The impact of the cultural revolution on trends in educational attainment in the People’s Republic of China. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 391–428. https://doi.org/10.1086/231212

- Ding, H. D., & Yu, L. J. (2013). The dilemma: A study of bilingual education policy in Yi minority schools in Liangshan. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(4), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2012.699943

- Feliciano, C., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2005). Gendered paths: Educational and occupational expectations and outcomes among adult children of immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(6), 1087–1118. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500224406

- Gorard, S., Huat, B., & Davies, P. (2012). The impact of attitudes and aspirations on educational attainment and participation. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Hannum, E. (2002). Educational stratification by ethnicity in China: Enrollment and attainment in the early reform years. Demography, 39(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2002.0005

- Hannum, E., Kong, P., & Zhang, Y. (2009). Family sources of educational gender inequality in rural China: A critical assessment. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(5), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.04.007

- Hanson, S. L. (1994). Lost talent: Unrealized educational aspirations and expectations among US youths. Sociology of Education, 159–183. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112789

- He, L. H., & Cheng, A. H. (2015). The educational development and education inequality of China’s ethnic minority regions: An empirical analysis based on the three recent nationwide population census. Ethno-National Studies, 2015(4), 11–21.

- Hong, Y. (2020). “Two basics” in a rural Muslim area of northwest China. In P. A. Kong, E. Hannum, & G. A. Postiglione (Eds.), Rural education in China’s social transition (pp. 73–87). Routledge.

- Hong, Y. B. (2010). Ethnic groups and educational inequalities: An empirical study of the educational attainment of the ethnic minorities in Western China. Chinese Journal of Sociology (in Chinese Version), 30(2), 45–77.

- Kao, G., & Tienda, M. (1998). Educational aspirations of minority youth. American Journal of Education, 106(3), 349–384. https://doi.org/10.1086/444188

- Khattab, N., Madeeha, M., Samara, M., Modood, T., & Barham, A. (2021). Do educational aspirations and expectations matter in improving school achievement? Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09670-7

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Li, J. J., & Geng, X. (2018). Minzudiqu shendu pinkun xianzhuanji zhili lujingyanjiu—yi ‘sanqusanzhou’ weili [Research on deep poverty status and poverty governance path in ethnic areas]. Minzu yanjiu, (1), 47–57.

- Long, H., & Pang, W. (2016). Family socioeconomic status, parental expectations, and adolescents’ academic achievement: A case of China. Educational Research and Evaluation, 22(5-6), 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2016.1237369

- LSY (Liangshan Statistical Yearbook). (2015). http://tjj.lsz.gov.cn/sjfb/lsndsj/tjnj2015/201710/t20171024_1177436.html

- Ma, R. (2013). Occupational mobility and migration of China’s ethnic minority regions: An empirical analysis based on 2010 nationwide population census. Zhongnan minzu daxue xuebao(renwen shehuikexueban), 33, 199 (6), 1–15.

- Ma, R. (2019). School education: The bridge towards modernization and common prosperity for ethnic minorities. Minzu Jiaoyu Yanjiu, 30(2), 5–12.

- McCulloch, A. (2017). Educational aspirations trajectories in England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1197883

- Mickelson, R. A. (1989). Why does jane read and write so well? The anomaly of women’s achievement. Sociology of Education, 47–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112823

- OECD, PISA. (2015). Database, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2015database/

- Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS (4th ed.). Allen & Unwin.

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. McGraw-hill education (UK).

- Pan, G. H. (2017). School merging, family background and opportunities of education attainment. Chinese Journal of Sociology (in Chinese Version), 37(3), 131–162.

- Portes, A., Vickstrom, E., Haller, W., & Aparicio, R. (2013). Dreaming in Spain: Parental determinants of immigrant children’s ambition. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(4), 557–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.757339

- Raftery, A., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112784

- Rehamo, A., & Harrell, S. (2018). Theory and practice of bilingual education in China: Lessons from Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(10), 1–16.

- Rothon, C., Arephin, M., Klineberg, E., Cattell, V., & Stansfeld, S. (2011). Structural and socio-psychological influences on adolescents’ educational aspirations and subsequent academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 14(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-010-9140-0

- Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Ohlendorf, G. W. (1970). The educational and early occupational status attainment process: Replication and revision. American Sociological Review, 1014–1027. https://doi.org/10.2307/2093379

- Sewell, W. H., Haller, A. O., & Portes, A. (1969). The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092789

- Strand, S. (2011). The limits of social class in explaining ethnic gaps in educational attainment. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903540664

- Teachman, J. D. (1987). Family background, educational resources, and educational attainment. American Sociological Review, 52(4), 548–557. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095300

- Trinidad, J. E. (2020). Will it matter who I’m in school with? Differential influence of collective expectations on urban and rural US schools. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 29(4), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2019.1673791

- Tsui, M. (2005). Family income, home environment, parenting, and mathematics achievement of children in China and the United States. Education and Urban Society, 37(3), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124504274188

- Wang, F. Q., & Shi, Y. W. (2014). Family background, educational expectation and college degree attainment: An empirical study based on Shanghai survey. Chinese Journal of Sociology (in Chinese Version), 34(1), 175–195.

- Wang, L. (2018). Recognition and redistribution in multicultural context --- A case study of bilingual education in Liangshan Yi Prefecture. Zhongnan Minzu Daxue Xuebao (in Chinese Version), 3, 70–73.

- Wang, L. (2019). Educational attainment in Liangshan: Analyses with education Gini Coefficient (2000-2015). Minzu Jiaoyu yanjiu (in Chinese Version), 30(2), 22–30.

- Wang, L., & Lehtomäki, E. (2022). Bilingual education and beyond: How school settings shape the Chinese Yi minority’s socio-cultural attachments. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(6), 2256–2268.

- Xie, A. L., & Postiglione, G. A. (2016). Guanxi and school success: An ethnographic inquiry of parental involvement in rural China. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(7), 1014–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.1001061

- Zhang, L. B., & Tsung, L. (2019). Bilingual education and minority language maintenance in China: The role of schools in saving the Yi language (Vol. 31). Springer International Publishing.

- Zhang, Y., Kao, G., & Hannum, E. (2007). Do mothers in rural China practice gender equality in educational aspirations for their children? Comparative Education Review, 51(2), 131–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/512023