ABSTRACT

International comparative measures show that South Africa has extremely low standards in reading. A variety of programmes aimed at boosting reading have been developed, however, the effectiveness of these programmes is unclear. Prior reviews of effective reading instruction practices have focused almost exclusively on learners whose first language and language of instruction is English. This paper reviews evidence from 17 intervention studies which focused on the teaching of reading comprehension in the distinctive multilingual context of South Africa. Although in line with prior reviews, we found some evidence that reading strategy instruction including vocabulary development are features of successful interventions alongside effective teacher education and resourcing of reading. These findings remained inconclusive due to variability in the quality of research, considerable methodological variations of the studies and the limited number of studies. Research in this field requires a more rigorous scientific approach to improve the evidence base.

Introduction

Being able to read is a foundational skill: it enables participation in education and society, it improves health outcomes and supports engagement in cultural and democratic processes (Castles et al., Citation2018). It is therefore unsurprising that teaching of reading is seen across the world as both an educational and public health priority (Progress in International Literacy Study, Citation2016; World Literacy Foundation, Citation2015). South Africa has long had issues with levels of literacy: international comparative studies place South Africa at the bottom of league tables (Mullis et al. Citation2011; Progress in International LIteracy Study, Citation2016). Effective reading comprehension, the focus of this review, is the ultimate objective of reading instruction (Oakhill & Cain, Citation2000). However, Mullis et al. (Citation2017) identify that 78% of South African learners in Grade 4 cannot read for meaning from a text compared to 4% of learners internationally. South Africa (SA) has a unique set of linguistic and socio-political factors that impact on education and so the teaching of reading. SA has eleven officially recognised languages, with English as the main language for learning and teaching from Grade 4 (Naidoo et al., Citation2014) in a population where English is the first language of just 10% (Howie et al., Citation2008). Prior systematic reviews or meta-analytic studies on reading instruction practices have almost exclusively been focused on learners whose first language is English in the USA or the UK where the community language and the language of instruction is English (Afflerbach et al., Citation2008; Block & Pressley, Citation2007; Paris & Myers, Citation1981). It therefore remains unclear whether “what works" in the Global North also works in countries like SA. Likewise, educational priorities for effective reading comprehension instruction for the Global North may not extend to SA. The primary objective of this systematic review, therefore, was to identify effective reading comprehension interventions that had been developed and implemented in SA.

Educational and linguistic context of SA

Learning to read in the community home language is first taught in the Foundation Phase (Grades 1–3) in South African schools and begins when learners are aged seven. During this period the extent of English language teaching varies from school to school (South African Human Rights Commission, Citation2021). Learners, often in the most socio-economically disadvantaged areas may engage in songs, rhymes and other simple language activities in English, whilst others, often from higher socio-economic status homes, are taught in “straight to English” schools (Spaull, Citation2013), learning to read in English from the start of Grade 1. When learners enter the Intermediate Phase of learning (Grades 4–6) the language of instruction becomes English in all schools (or in some schools, Afrikaans) and reading and reading comprehension is then taught in, and through English. Learners have different experiences of this transition and there is a topical and on-going debate about this point of transition to English (Taylor & von Fintel, Citation2016) and whether there should be a transition at all, with greater calls for a decolonisation of the education system including from policy makers (Basic Education minister, Angie Motshekga, Citation2021). Taylor and von Fintel (Citation2016, p. 88) contend that whilst the language of instruction is a pivotal factor in learning to read, SA has other more constraining factors, such as “poverty, weak school functionality, weak instructional practices, inadequate teacher subject knowledge, and a need for greater accountability throughout the school system”.

This becomes clear in the analysis by Spaull (Citation2016) of the prePIRLS (2011) data. PrePIRLS tests basic reading skills that are the prerequisites for achievement in the PIRLS assessments. Spaull (Citation2016) found that 58% of learners could not read for meaning in either their home language or in English and whilst this varied across provinces in SA, Spaull (Citation2016, p. 2) concluded that learners are not secure in reading for meaning in their home language before “they are switched into a second language” making even more complex the efforts to raise standards in reading. It is noteworthy that not all of the South African schools that participated in PIRLS in 2006 performed badly Mullis et al. (Citation2007) and this provides some evidence that the socio-economic stratification in the country plays out in the reading problem engulfing many classrooms. Spaull (Citation2013, p. 4) makes clear that the better performing 25% of learners “perform acceptably on national and international tests” and are drawn from the wealthiest quartile of students who attend schools that are well-resourced, have fewer teacher absences, are more likely to come from homes where English is spoken and have well-educated parents. The majority 75% have extremely low reading attainment performance and attend poorly resourced schools with high pupil to teacher ratios, high levels of staff absence, come from poor home backgrounds and where English is not spoken in the home. This is further compounded with regional variations: 83% of Grade 4 learners in Limpopo, one of the poorest provinces, cannot read for meaning, whilst that figure drops to 27% in the wealthier Western Cape (Spaull, Citation2016). Howie et al. (Citation2008) also highlight that it is learners who attend rural and township schools that demonstrate the lowest attainment. Zimmerman and Smit (Citation2014, p. 6) argue that the “differences in schooling conditions and learner achievement profiles across the PIRLS benchmark achievement spectrum were generally aligned with the differences between advantaged, high-achieving schools and disadvantaged, low-achieving schools”. Despite the South African government making education and reading specifically, a priority since 2008 (Department of Education, Republic of South Africa, Citation2008), there has been little measurable impact on reading achievement (Spaull & Taylor, Citation2022).

Naidoo et al. (Citation2014) in their review of educators’ perspective on the factors affecting reading literacy in SA, identify a number of issues that have impacted on reading comprehension achievement. It, alongside other studies identify the following four factors as impacting on the quality of teaching and on learning outcomes:

The contextual challenges faced at school level in relation to resources, class sizes, health and well-being of learners (Flint et al., Citation2019).

The lack of consistent and robust teacher education programmes that train pre-service teachers in the teaching of reading – in whatever Grade or subject they are training to teach (Klapwijk, Citation2012; Nel, Citation2011) leading to weak teacher pedagogical and subject knowledge of the teaching of reading and reading comprehension (Kruizinga & Nathanson, Citation2010; Kimathi & Bertram, Citation2019; Pretorius & Klapwijk, Citation2016; Zimmerman & Smit, Citation2014).

The complexity of the language challenges faced by teachers and learners – with English being the main language of learning, teaching and assessment alongside a multiplicity of home and community languages (Madikiza et al., Citation2018; Cekiso, Citation2012; Swanepoel et al., Citation2019; Nkomo, Citation2021).

The wider historical and political context of SA which impacts on every aspect of a learner’s educational experience (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; Combrinck & Mtsatse, Citation2019).

In relation to this historical and political context, the legacy of apartheid remains woven into the country’s reading tapestry. Stewart and Modiba (Citation2019, p. 149) highlight that the poor performance in education, particularly the reading problem in South Africa “persists despite the post-apartheid redistribution of resources, curriculum reforms within the education system”.

Teaching reading comprehension

Given the lack of systematic review studies on reading intervention research in SA, it is informative to examine “what works" in promoting reading comprehension skills in diverse populations of English as a Second Language learners (ESL). Our review of review studies indicated that most reading intervention studies targeting ESL students, had been conducted in the USA and on students from Latin American origins with Spanish as the main home language with fewer interventions conducted in Europe and/or on other bilingual language groups (Murphy & Unthiah, Citation2015; Oxley & De Cat, Citation2021; Rogde et al., Citation2019; Silverman et al., Citation2020).

Following the simple view of reading framework (Hoover & Gough, Citation1990), which states that reading comprehension is a product of decoding and language comprehension (listening comprehension), intervention studies of reading comprehension tend to focus on one of these two skills. Accurate word reading or deciphering the written code is clearly the essential first step for reading comprehension. Broadly, interventions targeting decoding skills tend to focus on improving children’s phonological skills or understanding of letter-sound relationships, which underpin effective word reading skills (Melby–Lervåg et al., Citation2012). However, accurate word reading is not sufficient to build a mental representation of the meaning of the written text and also requires language comprehension skills to access the meaning of words and sentences. Hence, intervention studies targeting language comprehension tend to focus on improving vocabulary and grammatical (morpho-syntactic) skills or a combination of these skills (Silverman et al., Citation2020).

The review studies concur that the interventions targeting phonological awareness or phonics are effective for promoting reading accuracy in both ESL and non-ESL students with relatively consistent results and moderate-to-large effect sizes (Richards-Tutor et al., Citation2016; Ludwig et al., Citation2019). By contrast, findings from interventions targeting language comprehension tend to be inconsistent with more varied effect sizes (Ludwig et al., Citation2019; Richards-Tutor et al., Citation2016; Rogde et al., Citation2019; Silverman et al., Citation2020). Most importantly, even when interventions targeting vocabulary or language comprehension may improve these skills as well as reading comprehension, these gains do not always generalise to standardised measures of vocabulary or reading comprehension and the reported effect sizes can vary from null to large depending on the outcome measure (Rogde et al., Citation2019; Silverman et al., Citation2020). Although these are surprising findings given the robust relationships between early language comprehension and later reading comprehension skills (Babayiğit et al., Citation2022), they are not entirely unexpected: language comprehension is complex and multidimensional, and draws on a wider range of interrelated language and cognitive skills, and can be affected by text and other social and cultural contextual factors. Therefore, intervention studies of language comprehension are highly varied in their approach and methodology, which may explain the observed varied outcomes.

Nonetheless for the purposes of the current review, it is important to note that both ESL and non-ESL students seem to benefit from the same interventions targeting vocabulary skills (see Silverman et al., Citation2020). Specifically, it has been found that integrated approaches, such as combining vocabulary with syntax contributed to large improvements in reading comprehension (Silverman et al., Citation2020). A few interventions which directly compared ESL with non-ESL students have noted that ESL students may improve their reading comprehension more than their non-ESL peers when the interventions focus on the specific linguistic strengths and needs of ESL students (Silverman et al., Citation2020). In accordance with these reports, targeting vocabulary or a combination of vocabulary and reading strategies has been found to help to close the ESL performance gap in vocabulary and reading comprehension (Dalton et al., Citation2011).

At this point, it should be noted that intervention studies focusing on strategies, text characteristics, motivation or qualitative studies are often excluded from the review studies (Silverman et al., Citation2020). The observed “cognitive bias" in reviews of interventions reflect the dominant cognitive view of reading comprehension which primarily focuses on decoding and related language and cognitive skills. The cognitive approach lends itself to experimental manipulation and calculation of effect sizes which is essential for making causal inferences. Therefore, the review studies of intervention which aim to draw causal inferences tend to exclude qualitative interventions of reading comprehension. It is also possible that observed cognitive bias in reading comprehension theory and interventions reflect the difficulty of operationalisation of these multidimensional variables and limited research.

The critics of the cognitive view of reading comprehension argue that literacy development cannot be confined to a set of cognitive skills: ESL students have unique linguistic and cultural knowledge and skills that shape their meaning making and engagement with written text. In fact, narrative review studies on effective reading instruction practices for ESL students in the USA, which included qualitative studies and expert opinions, have all emphasised the importance of rich vocabulary instruction along with native language support (Gersten & Baker, Citation2000; Klingner et al., Citation2006). The proponents of a “culturally relevant pedagogy” draw attention to the intrinsic effect of language and culture on meaning making. Promoting a critical understanding of linguistic and cultural heritage aims to empower ESL students to value their home language and culture and serves to bring closer together home and school, and thereby encourages the motivation to engage with learning while at the same time support higher teacher expectations and experience of success (for a review, see Kelly et al., Citation2021). For example, there is evidence that encouraging translanguaging (mixing home language with English) promotes better comprehension and critical thinking as well as higher motivation to engage with text (for a review, see García & Solorza, Citation2021).

However, effective implementation of culturally relevant reading comprehension instruction requires promoting teachers’ understanding of bilingualism and cultural practices that their ESL students bring to the classroom. Yet, culturally relevant pedagogy is often lacking in teacher training and there is a paucity of reading intervention studies targeting professional development of teachers in the USA and the UK (Murphy & Unthiah, Citation2015; Shelton et al., Citation2023).

To sum up, just as their peers with English as a first language, ESL students benefit from the same interventions targeting phonological skills, vocabulary, grammar and reading strategies and which aim to improve these skills and thereby their reading comprehension. Further, targeted approaches and drawing on ESL students’ cultural and linguistic heritage have been found to be both empowering and motivating with positive effects not only on their reading skills but overall academic development.

It remains unclear whether the findings from the review of effective reading comprehension interventions conducted mostly in the Global North can be extended to the South African context. It is likely that the highly diverse multilingual, socio-political and economic context of the SA present unique pedagogical opportunities as well as challenges. Accordingly, the most pressing issues that effective reading interventions must address to make a positive difference in children’s reading development may differ in SA and warrants further focused research.

Rationale and purpose

This systematic review aims to provide a narrative synthesis of successful reading comprehension interventions in the particular context of SA and the similarities and differences between interventions with favourable results. Whilst the review was designed to inform a larger intervention study which aimed to support South African pre-service and in-teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and skills in the effective teaching of reading comprehension in English, the findings from this review will also have implications for promoting the understanding of the issues that affect effective reading comprehension practices in similar countries with complex linguistic and socio-political contexts. The research questions for this review were therefore:

What are the most effective approaches to the teaching of reading comprehension in the South African context?

What are the issues raised by the review that should be the focus of educational policies to improve reading skills in the South African context?

Method

The question guiding the literature search and analysis was: What were the most successful approaches to the teaching of reading comprehension in the South African multilingual context? In the review we defined reading comprehension as the ability to extract meaning from written text.

In this review we focused on studies that were

Conducted in South Africa

Focused on the teaching of reading comprehension

Were intervention studies, with clear outcome measures, rather than descriptive accounts of classroom-based pedagogy

Search strategy

To identify relevant articles, thirteen databases were systematically searched to identify relevant research (). To expand the reach of the review, we also used the search engine Google Scholar to find additional sources not identified in the database search. Twelve Google pages were scanned for each combination of terms, at which a point of diminishing returns was established (Bowen et al., Citation2010). In addition, articles identified through the database search were subject to backwards citation searching. In addition, journals and other sources related specifically to the South African context were searched. The search was limited to peer reviewed articles, published in English after 31 December 2004. The majority of articles were identified through searches of the main databases.

Table 1. Databases, Search engines and South African Journals searched.

Key words used in the search

The original search terms were compiled through discussion between the authors, two of whom are based in South Africa and three in the UK. The terms chosen were related to reading comprehension, teaching, learning and pedagogy, intervention studies and learner outcomes in schools in South Africa. An iterative process was used to refine the search terms. Abstracts of the items identified were reviewed by the team and search terms were revised, added or removed. The full list of syntax is in Appendix 1.

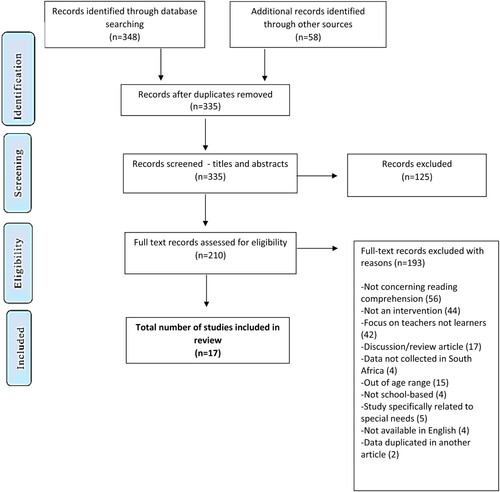

The search of the databases, journals and Google Scholar yielded a total of 335 records. These records were independently “eyeballed” (See et al., Citation2020) by one reviewer in South Africa and two in the UK using titles and abstracts, with disagreements resolved through discussion. This preliminary screening identified 210 articles for further scrutiny. Working in different universities in the UK and South Africa meant that not all articles were easily available to all researchers, so PDFs of all articles were saved in a shared folder.

Screening

The 210 records identified were then subject to full text screening. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were then used to screen the research papers.

Inclusion criteria

Conducted in South Africa

Published or reported in English

Primary, empirical research

About the teaching of reading comprehension, that is how learners are taught to extract meaning from written texts

Intervention study with a clearly defined outcome measure based on the effectiveness of the intervention study on reading comprehension (e.g., test scores)

Conducted with learners aged 5–16 years

School based rather than laboratory study

Mainstream school

Published after 31 December 2004

Exclusion criteria

Duplicates

Research not conducted in South Africa

Not primary empirical research (e.g., summary reports on the state of reading on South Africa, opinion pieces, descriptions of potential interventions with no evaluation of outcomes)

Not reported or published in English

Studies with preschool learners or learners in higher education

Research not specifically concerning reading comprehension (e.g., developing language skills, reading fluency)

Outcome is not about reading comprehension (e.g., reading fluency, reading enjoyment)

Not an intervention study (e.g. descriptive/anecdotal accounts of successful strategies with no outcome measures

Observational/ ethnographic research into teaching reading comprehension with no outcome measures

Studies not conducted in mainstream school settings

Research into how reading comprehension is addressed in teacher training programmes

The full text records were reviewed by one reviewer in South Africa and two in the UK. In order to ensure that the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied consistently, a number of steps were taken to ensure reliability between raters (Belur et al., Citation2021). Firstly a clear coding system for the inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed and all raters were trained in how to apply this. At the start, all the researchers independently assessed the same six studies and the results discussed. Only minor discrepancies between reviewers were noted, and discussion of these discrepancies between reviewers clarified the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each reviewer assessed between 60 and 70 articles each. Every 10th article assessed by each reviewer was reconsidered by the whole review team to ensure consistency. Taking a discussion-based view, rather than a numerical analysis of inter-rater reliability, followed Ashton’s (Citation2000) suggestion that discussion between reviewers is an effective way of improving the reliability of coding.

193 studies were excluded for the following reasons:

Not concerning reading comprehension (56)

Not an intervention (44)

Focus on teachers not learners (42)

Discussion/review article (17)

Data not collected in South Africa (4)

Out of age range (15)

Not school-based (4)

Study specifically related to special needs (5)

Not available in English (4)

Data duplicated in another article (2)

After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria and removal of duplicates, 17 studies remained for data extraction. The low number of studies included in the review is due to the specific nature of our research question, which is concerned with reviewing teaching strategies for reading comprehension which are potentially useful in South Africa. shows the number of studies at each stage of the review process.

Figure 1. Systematic review process (adapted from Moher et al. Citation2009 PRISMA flow chart).

Data extraction

Two reviewers from the UK and one from South Africa independently extracted the data from the articles. All the full text articles were examined by one of the UK based reviewers, the articles were also distributed between the other reviewers. A clear guide to the data extraction process was developed and the reviewers received training on how to use this guide to extract information from the identified articles. This helped ensure consistency in the process (Belur et al., Citation2021) as well as providing understanding of the education context in South Africa. Once this process was complete, all reviewers met to discuss the data extraction tables. No major discrepancies were apparent and through discussion any minor differences were addressed.

The Key information extracted included:

Description and focus of the intervention

Research design

o Is it a randomised control trial

o Is it a quasi-experiment with no randomised allocation to control condition?

o Are there control and comparison conditions?

o Are there pre and post event comparisons?

o Duration of intervention

Sample

o Sample size

o Age of participants

o Home language of participants

o Language of instruction

o Level of advantage/disadvantage of the school

Outcome measures

o What outcomes are measured?

Findings

o Reported results (including no effects or positive, with significance measures and effect sizes, where given)

Our data collection and analysis processes are shown in .

Assessing quality

Each of the seventeen studies were assessed initially for quality using the five criteria of Gorard et al.’s (Citation2017) sieve system, which considers the appropriateness of the research design for the research question, the scale of the study and/or the sample size, the attrition rate, the quality of outcome measure and any further threats to validity. Each study was assigned a score ranging from 1 for studies with the least secure evidence base for making causal claims to 4 which are the strongest. Studies with no comparator or control group were given a rating of 0 (See et al., Citation2020). The quality score for each article is shown in . The articles which presented qualitative data were assessed using the National Institute for Health and Care Guidance (NICE, Citation2012) critical appraisal checklist (CASP). This quality measure assesses how clear the purpose, context and focus to questions were, the relevance and range of studies referred to, validity and reliability of methods, rigour of analysis, strength of findings and recommendations, and if limitations were considered. A rating using CASP is determined by assigning studies with “++” meaning that most of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled, “+” that some of the checklist criteria have been fulfilled and “–" few or no checklist criteria have been fulfilled (NICE, Citation2012, p. 216).

Table 2. Summary of studies on reading comprehension interventions in South Africa.

Table 2. Continued

Of the 17 studies identified in the review, 13 studies presented quantitative outcomes (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Cekiso, Citation2012; Donald & Condy, Citation2005; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; le Roux et al., Citation2014; Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011; Sailors et al., Citation2010; Van Staden, Citation2011; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008) and 4 studies presented both quantitative and qualitative outcomes (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston et al., Citation2022; Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022).

Of the quantitative studies reviewed, no studies were rated as 4 padlocks, showing that overall quality was not high. Two studies were rated as three padlocks, (Donald & Condy, Citation2005; Sailors et al., Citation2010), six studies as two padlocks (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Cekiso, Citation2012; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; le Roux et al., Citation2014; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011; Van Staden, Citation2011) and five studies as one padlock. We decided to consider all the studies in the review, recognising that studies with a padlock level lower than 2 are to be treated with caution (See et al., Citation2020).

Four studies (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston et al., Citation2022; Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022) were rated as 0 padlocks in terms of Gorard et al.’s sieve system, as they reported some quantitative data. However, these studies also reported on qualitative findings. We determined an overall rating of ++ or + for all of these four articles, deeming them suitable for inclusion in the review.

Review approach

Following the identification of the seventeen studies, a narrative synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative outcomes presented in the studies was used to integrate the findings from the identified studies. This approach has been shown to be valuable in understanding the complexity of interventions carried out in specific contexts, where it is important not only to assess the difference in effect but also to understand how the intervention works (Noyes et al., Citation2019). Studies were grouped in relation to: the study contexts; language of instruction; sample sizes; duration of the intervention and methodology. A purely quantitative approach (meta-analysis) was not seen as appropriate for two reasons. Firstly due to the range of identified reading comprehension interventions and outcomes measures meant combining the results of the studies would not produce meaningful results. Secondly, only a small number of articles met both the inclusion criteria and the quality standards, meaning that a quantitative approach would be inappropriate and reductive.

Analytic procedure

Having grouped studies according to design features, as outlined above, the reviewers then identified the intervention approaches of the studies with the highest quality ratings. The 3 and 2 padlock studies were read and re-read by the four reviewers (three in the UK and one in South Africa) to identify and explore the key similarities and differences in the findings and intervention approach. The reviewers discussed these areas in online meetings to develop their understanding. Whilst the reviewers found some key similarities in these interventions, it was decided that the differences were significant enough to require the specifics of these interventions to be explored in the findings of this study, rather than just identifying generic themes. Studies with either a one of zero quality padlock, were then reviewed in relation to the higher quality studies and again, the specifics of these interventions were then incorporated in the discussion section of this article.

Limitations

The records included in the review were filtered to include peer reviewed journals, books and book chapters to ensure the quality of the articles included. However, this could lead to potential publication bias problems, where articles with positive or significant findings are more likely to be published, which may affect the results of this systematic review. No search of grey literature was conducted. This might have unearthed additional records of inclusion (e.g., practitioner reports, governmental and non-governmental organisation data and reports). The decision was taken to exclude these as it would not have been possible to assess the quality of these items.

Findings were limited to articles published in English, which may constrain the review. The four articles not published in English were available in Afrikaans.

Very few studies described a rigorous intervention with random allocation to conditions or a clear control group, as shown in the ratings given to the quality of research. As such, considerable caution is needed in drawing causal links between reading comprehension strategies and learner outcomes. In addition, reading comprehension is a complex process including a variety of cognitive and meta-cognitive sub-processes, many of the studies did not identify which of these subprocesses the intervention was addressing (Tárraga-Mínguez et al., Citation2021). Therefore, determining the processes underlying the effectiveness of a specific intervention is problematic.

Findings

Context of the studies

Of the 17 studies included in the review, nine were conducted in areas with high levels of poverty and disadvantage (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Donald & Condy, Citation2005; Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; le Roux et al., Citation2014; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011; Sailors et al., Citation2010). One study was conducted in an area described as a “previously disadvantaged community” (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013) and one described the area as “middle to lower income” (Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008). Two were conducted in affluent areas (Elston et al., Citation2022; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022). And four studies did not provide this information (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Cekiso, Citation2012; Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016; Van Staden, Citation2011).

Language of instruction

In eight of the studies, English was the language of instruction (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Cekiso, Citation2012; Elston et al., Citation2022; Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011). In one study the instruction was in home language and English (Sailors et al., Citation2010, this study was with Grades 1 and 2, foundation phase) and in three studies it was Afrikaans (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; le Roux et al., Citation2014; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008). In three studies the language of instruction was not stated clearly (Van Staden, Citation2011; Beck & Condy, Citation2017) (anticipated English); Donald & Condy, Citation2005 (anticipated Grades 1–3 isiXhosa and Grades 4–7 Afrikaans).

Sample size

The sample size varied between 1 and 1002 participants. Two studies included data from one learner (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston et al., Citation2022) and two studies had five participants (Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022). Four studies had fewer than 100 participants (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013, N = 20; Cekiso, Citation2012, N = 60; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011, N = 68; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008, N = 31). Nine studies had over 100 participants (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019, N = 215; Donald & Condy, Citation2005, N = 887; le Roux et al., Citation2014, N = 102; Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016, N = 152; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007, N = 104; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010, N = 227; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011, N = 142; Sailors et al., Citation2010, N = 1002; Van Staden, Citation2011, N = 288)

Duration of intervention

The duration of the interventions varied between 6 weeks and three years. Two studies conducted 6 week interventions (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston, Tiba & Condy, Citation2022), three conducted 8–10 week interventions (Fatyela et al., Citation2021; le Roux et al., Citation2014; Ntshikla et al., Citation2022). Four studies included interventions which lasted between 3 and 7 months (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; Cekiso, Citation2012; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; Van Staden, Citation2011; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008). Three studies did not give the duration of the intervention, but the pre- and post-tests were given 7/8 months apart (Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011). The intervention in one study was for one year (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019) and one study described a three-year intervention (Donald & Condy, Citation2005). Two studies did not provide clarity about the length of the intervention (Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016; Sailors et al., Citation2010).

Methodology

Of the 17 studies reviewed, twelve reported quasi experimental designs with pre- and post-testing. Of these twelve studies, two used control groups with random assignment to intervention conditions (Cekiso, Citation2012; le Roux et al., Citation2014), five used control groups (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Donald & Condy, Citation2005; Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011; Sailors et al., Citation2010) and five made no reference to control groups (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Van Staden, Citation2011; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008). Five of the studies reviewed were observations/case studies (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston et al., Citation2022; Fatyela et al., Citation2021; Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016; Ntshikila et al., Citation2022).

Scope and range of the seventeen studies

Following review, seventeen studies were identified that met the review criteria and these are outlined in . Studies had contrasting aims and focuses, from studies that had a focus on pedagogical approaches to teaching reading comprehension (Van Staden, Citation2011) to studies that concentrated on the resources for reading i.e., high quality books in the home language alongside professional development (Sailors et al., Citation2010) to a study that focused on whether it was possible to demonstrate the transfer of reading strategy knowledge (Klapwijk & Van der Walt, Citation2011). Studies that had a stated ESL focus, centred on the interrelationship between home and school language and reading instruction (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013), One study considered the impact of a reading comprehension programme on both the home language and English (Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011). It is also worthy of note that there were a number of linked studies: three of the articles identified (Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010; Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011) came from different stages of a longer study and each article focused on different aspects of the reading comprehension intervention. The Fatyela et al. (Citation2021), Ntshiklla et al. (Citation2022) and Elston et al. (Citation2022) studies all reported on the same intervention conducted in three different Grades of the same school. As none of the studies were rated as 4 in relation to quality, the overall quality of the research in this field is not high. It also means that caution must be taken when drawing conclusions. The features of the studies are set out in below.

Effective interventions

The two studies that had a quality rating of three had differing approaches. Sailors et al. (Citation2010) had “two-overarching” features: providing high-quality learners’ books in home languages and second languages alongside teacher education of appropriate strategy instruction and pedagogic approaches. The focus of the teacher education and subsequent mentoring and support was providing strategies to enable learners’ to engage with the texts offered – either as part of the whole class, shared reading teaching or to support children’s independent reading. The details of which strategies are not shared in the paper. The dual approach to securing reading comprehension and engagement in both the home and second language, was a key aim of the intervention. The other study that had a quality rating of three was Donald and Condy (Citation2005). This study also provided training for teachers and support materials and resources in an approach that integrated reading and writing. In Stage 1 of the programme, activity based approaches, shared reading, active pedagogic approaches designed to engage and motivate learners, individual and group work based around the text involving phonics and grammatical sentence structure development, were used in the programme. The intention was for this approach to be developed with learners in higher Grades, using more complex narrative text as well as non-fiction text and extending the role of discussion and reading comprehension strategy teaching. The programme was first embedded first in Grades 1–3 in the home language and then developed in higher Grades. The key similar features of these studies are the need for teacher education and training and continued support throughout an intervention. The teaching of a range of reading comprehension strategies was also evident in these studies but the detail of which strategies were taught, was not explicit. Both studies also identified motivation and engagement through culturally relevant resources and activities, as key elements of the intervention.

The six studies with a two quality rating also demonstrated some of these features. The study by Van Staden (Citation2011) emphasised teacher reading instruction and strategy education but the “education” was targeted at post-graduate students who were recruited to implement the intervention. The intervention prioritised the development of strategies and approaches to the teaching of vocabulary, for example, word-wall, word tracking, word games and sorting activities. Assessment was integrated into the intervention using a cloze procedure and this same activity was used to support reading strategy instruction (again with a focus on vocabulary by using context clues). Further reading strategies were taught through interactive discussion of text, including prediction, questioning, inference making, summarising and retelling. Castillo and Wagner (Citation2019) used a computer based programme which focused on specific literacy skills involving both reading and writing. These included phonemic awareness; sentence construction, spelling, grammar and short passage reading and comprehension questions. Explicit strategy instruction was not as evident in this intervention and the use of a computer programme negated the need for teacher education. Cekiso (Citation2012); Klapwijk and Van der Walt (Citation2011) and Pretorius and Lephalala (Citation2011) all focused interventions of developing teacher knowledge and understanding of strategy instruction and in providing teachers with on-going support to implement structured reading lessons. Strategies were modelled by teachers in each of these studies with common strategies as a focus: prediction; questioning; vocabulary; summarising; clarifying and connection making. Each of these studies also made clear the importance of motivation and engagement of learners, either through the teaching approach or as in Pretorius and Lephalala (Citation2011) the provision of culturally relevant reading resources. le Roux et al. (Citation2014) the fourth study to have a quality grading of two, also, it could be argued focused on motivation (learners read to therapy dogs) and resourcing (learners were provided with texts to read to the dogs). This final intervention also demonstrates a foundational principle of all of the three and two quality rated studies, that is they ensured that dedicated time each week was spent on the teaching of reading comprehension.

Discussion: issues raised by the studies

Scale, quality and reliability of studies

The final seventeen articles in this review raised questions about the scale, reliability and quality of the research in SA. Many of the studies were small scale, including two with a focus on one child (Beck & Condy, Citation2017; Elston et al., Citation2022) and one school (Basson & le Cordeur, Citation2013; Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007; Pretorius & Currin, Citation2010 and Pretorius & Lephalala, Citation2011). The context of learning to read in SA is set out at the beginning of this article and the complexity of the types of schools, school locations and languages spoken in each, mean that any research that is small scale and context specific, is difficult to generalise from in relation to reading comprehension in all schools. In addition to these language differences in schools, the study by Sailors et al. (Citation2010) highlighted the differing impact of their intervention across schools. They identified schools who implemented the intervention with fidelity saw greater impact than the other schools implementing the intervention. These differences in schools suggest that scalability of the interventions may be problematic and scalability is not addressed in any of the studies. However, whilst larger scale studies would be valuable, there clearly also needs to also be a recognition that each unique context may require a bespoke curricular, based first on general reading research evidence on effective approaches to teaching reading comprehension, but adapted to meet the differing needs of each context.

Another element of study design this review has noted, is the short term nature of the research studies, with none being longitudinal studies of more than three years. Identifying the continued impact of an intervention beyond the end of the intervention is an important area to consider in terms of a “what works" approach going forward.

In terms of study quality, many studies did not use standardised test instruments for pre and post intervention measurements. Whilst the case is made in some that these do not exist for many of the home languages (Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007) other studies designed their own tests (Donald & Condy, Citation2005) or relied largely on the self-reporting by teachers (Makumbila & Rowland, Citation2016). This lack of standardised measures makes the identification of effective interventions more difficult. This was the same issue found in many of the studies in the USA and UK, as outlined in the introduction to reading comprehension in this article.

Explicit identification of approaches that impacted on outcomes

Studies were often multi-layered, with a range of approaches used in combination in the intervention and this was both evident in the two studies with a two quality rating as well as all of the other studies. There was a lack of clarity about which aspect of the intervention impacted on the outcomes. Further studies are needed to identify the most effective combination of approaches to tackle reading comprehension attainment in SA. Silverman et al. (Citation2020) in the studies reviewed in the USA and the UK, recognised that the integration of approaches was often more effective and noted that the integration of vocabulary and syntax was found to be the more effective approach for the ESL learner but none of the South African studies focused explicitly on just this integration although vocabulary instruction was a feature of the South African studies. Klingner et al. (Citation2006) in the Global North studies also outlined the need for “culturally responsive pedagogy” and this was a feature of the studies in this review – with a particular focus on culturally relevant text and learning activities.

Systematic approach to Reading comprehension at all levels of readers

The final seventeen studies also varied in the Grade of learners they focused on. This may reflect the fact that SA is grappling with the complex nature of the development of the learner in becoming a reader. Stanovich (Citation1995) suggests learners need to first develop their skills in the automatic decoding skills that enable the initial ability to comprehend. Alongside this process, the multiple skills needed to comprehend first orally and then through reading, need to be practised and taught. Most of the final studies (and indeed the wider studies surveyed) identified the very low attainment levels of the learners at all ages and Grades. Without a systematic, robust and adhered to curriculum for the teaching of early reading, low attainment in reading comprehension becomes almost inevitable in the later Grades. The studies also make clear the rather obvious statement that if you cannot decode the words on the page, you will not be able to develop your skills in reading comprehension. Pretorius and Lephalala (Citation2011) make clear in their findings that the learners who made the greatest gains from the reading comprehension intervention were the learners who could read, who began the intervention at the 75th percentile in the pre-intervention comprehension test and those that made the least progress were the learners who began below the 25th percentile. They point out that this is consistent with Stanovich's (Citation1986) “Matthew Effect”: the rich get richer. This finding is particularly interesting as the other studies do not break down the impacts of their intervention, generally reporting mean effect sizes and this difference is significant when identifying effective reading comprehension interventions. To be effective, learners need to be able to decode. There is general agreement amongst reading researchers that being able to understand the relationship between the letters and their sounds is non-negotiable (Castles et al., Citation2018) and whilst not sufficient in itself, is essential. Klapwijk and Van der Walt (Citation2011) elaborate: whilst there is a link between word reading skill and comprehension, one does not guarantee the other: “reading comprehension is determined by more than word reading skill and conversely … strong word reading skills do not necessarily ensure good comprehension.” (p. 33). Studies in this review indicate that this skill is not secure in the home language or in the second language and yet only three of the studies in SA made explicit reference to phonics. This may have been because phonics is seen to be an early reading intervention and many of the studies focused on learners in the later Grades. Where studies also focused on the home language, it could be argued phonics is less useful in many African languages.

Variation in language focus

The studies varied in whether they focused on the home language reading comprehension, English reading comprehension or both. Studies generally referenced the need for the home language (L1) to be secure and that this would support second language (L2) learning however, this was not always evident in the research findings of these intervention studies. Pretorius and Mampuru (Citation2007) found that the relationship between L1 and L2 was not consistent with research in other national contexts. They contest that this is because L1 learning is also impacted by context and in particular the lack of reading resources in many of the South African home languages. This means that learners do not have sufficient opportunities to develop the skills of reading and reading comprehension in L1. Many more books are available in English, the main L2 of many learners and so their intervention saw a greater impact on L2 than L1 that they suggest may be due to the issue of resourcing. In reading comprehension reviews in other country contexts (Kelly et al., Citation2021) the beneficial role of “culturally relevant pedagogy” is made clear: without the appropriate resources and knowledge to develop the home language in SA, the resulting benefits will not be forthcoming.

Resourcing

Issues around resources for teaching and availability of books was a feature of the contextual background provided of where the interventions took place. Schools in the studies did not have basic resources to enable children to practise their reading. Pretorius and Mampuru’s (Citation2007) article is titled “Playing football without a ball” and conclude that even if a school has a sound literacy development programme, learners are not likely to experience success if they do not have the books that enable them to practise, to engage and so develop a habit of reading that becomes part of the “virtuous cycle” of reading development (OECD, Citation2014). Resourcing is also a factor to consider in the wider implementation of the computer-based interventions (Castillo & Wagner, Citation2019; Van Wyk & Louw, Citation2008). If schools do not have books, they may also not have functioning and up to date computer suites that can accommodate learners for computer-based interventions.

Whilst physical resourcing is one constraint on the implementation of interventions, the teacher as the main resource is another. Studies varied in their intervention organisation, for example, in the study by Van Staden (Citation2011) learners were taught in groups of two to six having been selected for the intervention following assessments of their attainment, with a focus on the lower attaining learners in Grades 4–6. As outlined earlier, class sizes in SA are often very large (with 60 learners in a class being common in township schools). There are few additional adults in schools with the required knowledge and expertise to implement small group interventions, and so there is a question as to whether this sort of intervention is a practical option for schools. Whilst the outcomes of studies using small group interventions are useful it is also equally pressing to identify whole class interventions that can address the high levels of underachievement in reading comprehension in SA.

Teacher and pre-service skills and knowledge

Issues of teacher skill and knowledge are highlighted in studies. Some studies included teacher training in their study design (Donald & Condy, Citation2005) and some provided in class coaching (Pretorius & Mampuru, Citation2007). Lack of teacher content and pedagogic knowledge about the teaching of reading was highlighted. It is not just a need to address what is taught in South African classrooms but also a need to provide teachers with the skills and pedagogic knowledge that they need. Initial teacher education needs to be at the forefront, not only ensuring teachers have both an understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of the teaching of reading but also the practical, pedagogic skills to teach reading and to teach reading for ESL learners. It is not only the foundation stage teachers who need to know how to teach reading but also those training to teach the intermediate Grades and higher Grades so they are equipped to manage the long tail of underachievement that exists currently. Klapwijk and Van der Walt (Citation2011) note that teachers need to see evidence that the intervention they are being asked to implement makes a difference to their learners before teachers have “buy-in” and this is an issue that needs to be addressed in any future curriculum policy. Studies reviewed in the USA and the UK (Murphy & Unthiah, Citation2015; Shelton et al., Citation2023) also highlight a lack of focus in teacher education on ESL learners.

Conclusion and recommendations

SA faces a wide range of complex challenges in relation to reading comprehension development. The legacy of apartheid in relation to inequalities in the education system continues to impact on class sizes, resources, teacher pupil ratios, the language of teaching and learning, teacher education and professional development. Interventions to address the underachievement in reading are constrained by all of these factors. The unique and diverse school contexts also highlight the difficulty of finding a single, research evidenced intervention, applicable to all. This systematic review therefore identified four key recommendations based on the issues raised by the review that should guide future educational policies in South Africa to improve reading skills. These are: the promising areas of focus for future studies; the need for interventions that develop teacher knowledge; the requirement to address issues of resourcing and the need for more robust study designs.

Future studies need to build on what is known about reading comprehension more widely and the specific features of successful interventions in SA. Interventions focusing on the modelled and explicit instruction of reading comprehension strategies including vocabulary development (in both the home and English language) have an impact on outcomes.

Studies that included teacher training and coaching offer some further indication of the need to focus not just on the curriculum taught but also on the subject and pedagogical knowledge and skills of teachers. Teachers in the foundation Grades need the skills to address language comprehension as well as word reading skills in learners’ first language so that learners have a chance of making the transition to their second language. To support this, schools need resourcing properly to enable learners to have the opportunities they need to practise reading in both their home and second language. In the studies surveyed it is issues around language that are most often cited with the transition from Grades 3–4 presenting learners with a huge challenge in relation to reading comprehension in their second language.

Larger scale, longitudinal studies with study designs that include standardised assessment instruments to demonstrate outcomes are needed. Randomised Control Trials with accompanying qualitative case studies that enable the contextualisation of intervention, would provide more reliable and valid data. In addition, consideration has to be made to the scaling of interventions and their applicability across the challenging context of many South African classrooms. It is this secure evidence that is needed on which to base policy initiatives going forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jane Carter

Dr Jane Carter is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Education and Childhood at the University of the West of England (UWE). Her work concerns all aspects of literacy with a particular interest in the teaching of early reading and comprehension as well as approaches to engaging all children and families with reading. She is currently leading a multi-disciplinary team at UWE and the University of Zululand funded by a British Academy Tackling Global Challenges award, which has designed and implemented a mobile phone app that aims to support teachers and student teachers in rural and township schools in South Africa with the teaching of comprehension.

Tessa Podpadec

Dr Tessa Podpadec is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Education and Childhood at the University of the West of England. Her work concerns sustainable futures in education, including children’s experiences of racism and well-being, futures thinking about climate changes, as well as the use of mixed-methods evidence to inform educational policy change.

Pravina Pillay

Dr Pravina Pillay is an Associate Professor of English Studies at the University of Zululand in South Africa. Her research interests include English Language Education, English Literary Studies, World Literatures and Higher Education in South Africa. Professor Pillay has published extensively in national and international journals.

Selma Babayiğit

Dr Selma Babayiğit is a Senior Lecture in Psychology at the University of the West of England. Her work concerns the language and cognitive skills that underpin literacy development of children from diverse language backgrounds. Her current research considers the cognitive effects of bilingualism and the ways in which strengths and weaknesses in cognitive and language skills interact to influence reading comprehension and academic attainment in both monolingual and bilingual/multilingual groups.

Khulekani Amegius Gazu

Dr Khulekani Gazu is a lecturer of English Studies in the School of Arts, University of South Africa (Unisa). His research foci include English second language teaching and learning, empirical literary studies, and discourse analysis. He is currently supervising research at post-graduate level and has examined theses in the area of English teaching and learning.

References

- Afflerbach, P., Pearson, P. D., & Paris, S. G. (2008). Clarifying differences between Reading skills and Reading strategies. The Reading Teacher, 61(5), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.61.5.1

- Ashton, R. H. (2000). A review and analysis of research on the test + retest reliability of professional judgment. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13(3), 277–294.

- Babayiğit, S., Hitch, G. J., Kandru-Pothineni, S., Clarke, A., & Warmington, M. (2022). Vocabulary limitations undermine bilingual children’s Reading comprehension despite bilingual cognitive strengths. Reading and Writing, 35(7), 1651–1673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10240-8

- Basson, M., & le Cordeur, M. (2013). Enhancing the vocabulary of isiXhosa mother tongue speakers in grade 4 to 6 in Afrikaans schools. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, 53(3), 377–390.

- Beck, S., & Condy, J. L. (2017). Instructional principles used to teach critical comprehension skills to a grade 4 learner. Reading & Writing, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v8i1.149

- Belur, J., Tompson, L., Thornton, A., & Simon, M. (2021). Interrater reliability in systematic review methodology: Exploring variation in coder decision-making. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(2), 837–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118799372

- Block, C. C., & Pressley, M. (2007). Best practices in teaching comprehension. In L. B. Gambrell, L. M. Morrow, & M. Pressley (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction. The Guildford Press.

- Bowen, F., Newenham-Kahindi, A., & Herremans, I. (2010). When suits meet roots: The antecedents and consequences of community engagement strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0360-1

- Castillo, N. M., & Wagner, D. A. (2019). Early-grade Reading support in rural South Africa: A language-centred technology approach. International Review of Education, 65(3), 389–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-019-09779-0

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the Reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271

- Cekiso, M. (2012). Reading comprehension and strategy awareness of grade 11 English second language learners. Reading & Writing, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v3i1.23

- Combrinck, C., & Mtsatse, N. (2019). Reading on paper or Reading digitally? Reflections and implications of ePIRLS 2016 in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 39(S2), 1771. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns2a1771

- Dalton, B., Proctor, C. P., Uccelli, P., Mo, E., & Snow, C. E. (2011). Designing for diversity. Journal of Literacy Research, 43(1), 68–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X10397872

- Department of Education, Republic of South Africa. (2008). National Reading strategy. Centre for evaluation and assessment. Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria. National_Reading.pdf (education.gov.za).

- Donald, D. R., & Condy, J. M. (2005). Three years of a literacy development project in South Africa: An outcomes evaluation. Africa Education Review, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146620408566288

- Elston, A,, Tiba, C., & Condy, J. (2022). The role of explicit teaching of reading comprehension strategies to an English as a second language learner. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v12i1.1097

- Fatyela, V., Condy, J., Meda, L., & Phillips, H. (2021). Improving higher-order comprehension skills of Grade 3 learners in a second language at a quintile 2 school, in Cape Town, South Africa. Reading & Writing, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/rw.v12i1.312

- Flint, A. S., Albers, P., & Matthews, M. (2019). ‘A whole new world opened up’: The impact of place and space-based professional development on one rural South Africa primary school. Professional Development in Education, 45(5), 717–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1474486

- García, O., & Solorza, C. R. (2021). Academic language and the minoritization of U.S. Bilingual Latinx students. Language and Education, 35(6), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1825476

- Gersten, R., & Baker, S. (2000). What we know about effective instructional practices for English-language learners. Exceptional Children, 66(4), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290006600402

- Gorard, S., See, B. H., & Siddiqui, N. (2017). The trials of evidence based education: The promises, opportunities and problems of trials in education. Routledge.

- Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of Reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00401799

- Howie, S. J., Venter, E., & Van Staden, S. (2008). The effect of multilingual policies on performance and progression in Reading literacy in South African primary schools. In: SJ Howie & T. Plomp (Eds.): Reading achievement: International perspectives from IEA’s progress in international Reading literacy studies (PIRLS). Educational Research and Evaluation, 14(6), 551–560.

- Kelly, L. B., Wakefield, W., Caires-Hurley, J., Kganetso, L. W., Moses, L., & Baca, E. (2021). What is culturally informed literacy instruction? A review of research in p–5 contexts. Journal of Literacy Research, 53(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X20986602

- Kimathi, F. K., & Bertram, C. (2019). Oral language teaching in English as first additional language at the foundation phase: A case study. Reading & Writing, 11(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v11i1.236

- Klapwijk, N., & Van der Walt, C. (2011). Measuring Reading strategy knowledge transfer: Motivation for teachers to implement Reading strategy instruction. Per Linguam, 27(2), 25–40.

- Klapwijk, N. M. (2012). Reading strategy instruction and teacher change: Implications for teacher training. South African Journal of Education, 32(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v32n2a618

- Klingner, J. K., Artiles, A. J., & Méndez Barletta, L. (2006). English language learners who struggle with Reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(2), 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390020101

- Kruizinga, A., & Nathanson, R. (2010). An evaluation of guided Reading in three primary schools in the Western Cape. Per Linguam, 26(2), 67–76.

- le Roux, M. C., Swartz, L., & Swart, E. (2014). The effect of an animal-assisted Reading program on the Reading rate, accuracy and comprehension of grade 3 students: A randomized control study. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(6), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9262-1

- Ludwig, C., Guo, K., & Georgiou, G. K. (2019). Are Reading interventions for English language learners effective? A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 52(3), 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219419825855

- Madikiza, N., Cekiso, M. P., Tshotsho, B. P., & Landa, N. (2018). Analysing English first additional language teachers’ understanding and implementation of Reading strategies. Reading & Writing, 9(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/rw.v9i1.170

- Makumbila, M. P., & Rowland, C. B. (2016). Improving South African third graders’ Reading skills: Lessons learnt from the use of Guided Reading approach. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 6(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.367

- Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S.-A. H., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2535–b2535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Motshekga, A. (2021). Introduction of Kiswahili in curriculum to contribute to decolonisation. https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/introduction-kiswahili-curriculum-contribute-decolonisation.

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Kennedy, A. M., & Foy, P. (2007). PIRLS 2006 International Report: IEA's Progress in International Reading Literacy Study in primary schools in 40 countries Boston College , Chestnut Hill, MA.

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Kennedy, A. M., Trong, K. L., & Sainsbury, M. (2011). PIRLS 2011 Assessment framework. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). Pirls 2016 international results in Reading. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.

- Murphy, V. A., & Unthiah, A. (2015). A systematic review of intervention research examining English language and literacy development in children with English as an Additional Language (EAL). Educational Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Presentations/Publications/EAL_Systematic_review.pdf.

- Naidoo, U., Reddy, K., & Dorasamy, N. (2014). Reading literacy in primary schools in South Africa: Educator perspectives on factors affecting Reading literacy and strategies for improvement. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 7(1), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/09751122.2014.11890179

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012). Methods for the development of NICE public Health guidance (3rd ed.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0089896/pdf/PubMedHealth_PMH0089896.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Nel, N. M. (2011). Second language difficulties in a South African context. In E. Landsberg, D. Kruger, & E. Swart (Eds.), Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspective. Van Schaik.

- Nkomo, S. A. (2021). Implementing a bilingual extensive Reading programme in the foundation phase: Theory and practice. Per Linguam, 36(2), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.5785/36-2-876

- Noyes, J., Booth, A., Moore, G., Flemming, K., Tunçalp, Ö, & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: Clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Global Health, 4, e000893. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000893

- Ntshikila, N., Condy, J. L., Meda, L., & Phillips, H. N. (2022). Five Grade 7 learners’ understanding of comprehension skills at a quintile 5 school in South Africa. Reading & Writing, 13(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/rw.v13i1.324

- Oakhill, J., & Cain, K. (2000). Children's difficulties in text comprehension: Assessing causal issues. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 5(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/5.1.51

- OECD. (2014). Reading performance (indicator), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris.

- Oxley, E., & De Cat, C. (2021). A systematic review of language and literacy interventions in children and adolescents with English as an additional language (EAL). The Language Learning Journal, 49(3), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2019.1597146

- Paris, S. G., & Myers, M. (1981). Comprehension monitoring, memory, and study strategies of good and poor readers. Journal of Reading Behavior, 13(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862968109547390

- Pretorius, E. J., & Currin, S. (2010). Do the rich get richer and the poor poorer? International Journal of Educational Development, 30(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.06.001

- Pretorius, E. J., & Klapwijk, N. M. (2016). Reading comprehension in South African schools: Are teachers getting it and getting it right? Per Linguam, 32(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5785/32-1-627

- Pretorius, E. J., & Lephalala, M. (2011). Reading comprehension in high-poverty schools: How should it be taught and how well does it work? Per Linguam, 27(1), 1–24.

- Pretorius, E. J., & Mampuru, D. M. (2007). Playing football without a ball: Language, Reading and academic performance in a high-poverty school. Journal of Research in Reading, 30(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2006.00333.x

- Progress in International Literacy Study. (2016). PIRLS 2016 international report. South African children’s reading literacy achievement, international report. Centre for Evaluation and Assessment, University of Pretoria, Pretoria .

- Richards-Tutor, C., Baker, D. L., Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., & Smith, J. M. (2016). The effectiveness of Reading interventions for English learners. Exceptional Children, 82(2), 144–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402915585483

- Rogde, K., Hagen, ÅM, Melby-Lervåg, M., & Lervåg, A. (2019). The effect of linguistic comprehension instruction on generalized language and Reading comprehension skills: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15(4), e1059. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1059

- Sailors, M., Hoffman, J. V., Pearson, P. D., Beretvas, S. N., & Matthee, B. (2010). The effects of first- and second-language instruction in rural South African schools. Bilingual Research Journal, 33(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235881003733241

- See, B. H., Gorard, S., El-Soufi, N., Lu, B., Siddiqui, N., & Dong, L. (2020). A systematic review of the impact of technology-mediated parental engagement on student outcomes. Educational Research and Evaluation, 26(3-4), 150–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2021.1924791

- Shelton, A., Hogan, E., Chow, J., & Wexler, J. (2023). A synthesis of professional development targeting literacy instruction and intervention for English learners. Review of Educational Research, 93(1), 37–72. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221087718

- Silverman, R. D., Johnson, E., Keane, K., & Khanna, S. (2020). Beyond Decoding: A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Language Comprehension Interventions on K-5 Students' Language and Literacy Outcomes. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rrq.v55.s1

- South African Human Rights Commission. (2021). The right to read and write. https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/The%20Right%20To%20Read%20and%20Write%20Report%20(12%20Aug%202021).pdf.

- Spaull, N. (2013). South Africa's Education Crisis: The quality of education in South Africa 1994-2011. https://nicspaull.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/spaull-2013-cde-report-south-africas-education-crisis.pdf.

- Spaull, N. (2013). Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(5), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.009

- Spaull, N. (2016). Learning to Read and Reading to Learn. Policy Brief (April). Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development (PSPPD). Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP). RESEP-Policy-Briefs_Nic_Spaull-EMAIL.pdf (sun.ac.za).

- Spaull, N., & Taylor, S. (2022). Early grade Reading and mathematics interventions in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Early grade interventions in South Africa: Reading and mathematics. Oxford Resource Hub.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.21.4.1

- Stanovich, K. E. (1995). How research might inform the debate about early reading acquisition. Journal of Research in Reading, 18(2), 87–105.

- Stewart, S. L., & Modiba, M. (2019). Reading grannies. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 8(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.32674/jise.vi0.725

- Swanepoel, N., van Heerden, J., & Hartell, C. (2019). Teacher perspectives and practices in teaching English Reading comprehension to grade 2 first additional language learners. Journal for Language Teaching, 53(1), https://doi.org/10.4314/jlt.v53i1.4

- Tárraga-Mínguez, R., Gómez-Marí, I., & Sanz-Cervera, P. (2021). Interventions for improving Reading comprehension in children with ASD: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 11), https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11010003

- Taylor, S., & von Fintel, M. (2016). Estimating the impact of language of instruction in South African primary schools: A fixed effects approach. Economics of Education Review, 50, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.01.003

- Van Staden, A. (2011). Put Reading first: Positive effects of direct instruction and scaffolding for ESL learners struggling with Reading. Perspectives in Education, 29, 10–21.

- Van Wyk, G., & Louw, A. (2008). Technology-assisted Reading for improving Reading skills for young South African learners. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 6(3), 245–254.

- World Literacy Foundation. (2015). The economic and social cost of illiteracy: A snapshot of illiteracy in a global context. https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/WLF-FINAL-ECONOMIC-REPORT.pd.

- Zimmerman, L., & Smit, B. (2014). Profiling classroom Reading comprehension development practices from the PIRLS 2006 in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 34(3), 1–9. doi:10.15700/201409161101