?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

For students who perform inconsistently across subjects, teachers face challenges in formulating track recommendations, as their achievement will not point to one secondary school track. This issue may be more prominent for students from diverse backgrounds, given the achievement differences between specific subject domains within these groups. Therefore, we examined the impact of achievement inconsistency (by comparing standardised achievement levels between reading comprehension and mathematics within students) on students’ track recommendations in the Dutch educational system (N = 4,248). Most student perform rather consistently. Approximately 20% of the students performed inconsistently (>1 SD difference between subjects). While the overall effect of inconsistency on track recommendations was small, achievement inconsistency primarily seemed to affect track recommendations when the inconsistency was moderate to large. Teachers formulated more “careful” (i.e., lower) track recommendations when the inconsistency was large. This effect was slightly more pronounced for higher-SES students, with no gender differences.

In some tracked educational systems, teachers’ track recommendations at the end of primary education are used to allocate students to different hierarchical secondary school tracks that determine their future educational career (Glock et al., Citation2012; Strand, Citation2020). Prior research (Feron et al., Citation2013; Timmermans et al., Citation2015; Van Leest et al., Citation2021) has indicated that these track recommendations are mostly based on students’ (prior) achievement in multiple subject domains, where correlations between subjects – for example, reading comprehension and mathematics – imply relatively consistent achievement within a student across different subject domains. However, some students may show discrepancies between these different subject domains (Luyten, Citation1998). As secondary school tracks typically offer the same educational level for all subject domains, teachers may find it difficult to formulate track recommendations for students who perform inconsistently, as their achievement will not point directly to one specific level of secondary education. In addition, achievement inconsistency may occur more often or look different among students with different background characteristics, such as gender or socioeconomic status (SES), due to different achievement levels in specific subject domains among these students. In case of achievement inconsistency, boys and lower-SES students typically perform lower in the language domain, whereas girls and higher-SES students with achievement inconsistency more often perform lower in mathematics (e.g., Hakkarainen et al., Citation2013; Jacobs & Wolbers, Citation2018; Plante et al., Citation2013; Sirin, Citation2005; Uerz et al., Citation2004; Van Leest et al., Citation2021). These group differences in achievement across different subject domains may cause differences in teachers’ track recommendations. This is particularly true if teachers place greater emphasis on a particular subject domain when formulating these track recommendations (Driessen et al., Citation2008; Smeets et al., Citation2014). For example, if teachers base their track recommendations more strongly on reading comprehension than mathematics, this may disproportionally affect lower-SES students and boys, especially if these groups have larger achievement inconsistencies than other groups.

However, it is thus far unknown how achievement inconsistency affects teachers track recommendations. It may lead to “careful” (i.e., lower) recommendations’ based on students’ achievement in their weakest domain, “aggregated recommendations” based on the mean achievement of two domains, or alternatively, “the benefit of the doubt-recommendation” based on students’ achievement in their strongest domain. Moreover, achievement inconsistency may lead to differences between teachers in which track recommendations they formulate for such students, with some teachers opting for more careful recommendations and others for aggregated or higher recommendations. If teachers do indeed consider achievement inconsistency when formulating track recommendations, this could impact students’ opportunities to attend higher secondary school tracks. For instance, if lower-SES students show more achievement inconsistency between subject domains than higher-SES students, and teachers tend to be more cautious in their track recommendations for students with inconsistent achievement, this might result in reduced opportunities for lower-SES students to attend higher tracks.

To improve educational equality at the transition from primary to secondary education for all students, it is important that teachers formulate track recommendations that fit students’ abilities and potential best (Tieben & Wolbers, Citation2010). Given the scarcity of prior research, it is not clear how achievement inconsistency across different subject domains affects students’ track recommendation in general, or whether teachers consider achievement inconsistency differently for students with different background characteristics. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to examine the extent to which achievement inconsistency between language (i.e., reading comprehension) and mathematics within students occurs, how this is associated with students’ SES and gender, and, in turn, with teachers’ track recommendations.

(In)consistency of students’ achievement and track recommendations

In some tracked educational systems, such as France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, teachers have to provide a recommendation for the school track that students will attend in secondary education (Boone & Van Houtte, Citation2013; Glock et al., Citation2012; Korpershoek et al., Citation2016; Le Métais, Citation2003; Timmermans et al., Citation2015). These track recommendations are formulated at the end of primary school, whereby teachers recommend a type of secondary education that they consider to match the student’s potential ability level best (De Boer et al., Citation2010; Glock et al., Citation2013; Timmermans et al., Citation2015). These track recommendations are important, since they determine students’ allocation to a specific educational level in secondary school, and thereby the educational qualifications students can acquire (Glock et al., Citation2012; Strand, Citation2020). These track recommendations are based on teachers’ expectations, i.e., teachers’ inferences about students’ potential behaviour or achievement (De Boer et al., Citation2010; Klapproth et al., Citation2012; Timmermans et al., Citation2015). Although the different factors that teachers consider when formulating track recommendations may differ per educational system, depending on the extent to which teachers are able to include their own perceptions in the track recommendations, research in various countries has shown that in general track recommendations are primarily based on students’ (standardised) achievement in mathematics and reading comprehension (Bos et al., Citation2004; Ditton & Krüsken, Citation2006; Feron et al., Citation2013; Geven et al., Citation2021; Klapproth et al., Citation2012; Südkamp et al., Citation2012; Timmermans et al., Citation2015).

Although most students perform rather similarly (or consistently) across both domains (i.e., there is a strong positive correlation between reading comprehension and mathematics), there are also students whose achievement across subject domains differs: their achievement across domains is inconsistent (e.g., high achievement in language and lower achievement in mathematics or vice versa) (Luyten, Citation1998; Timmermans et al., Citation2015; Van Leest et al., Citation2021). If students perform rather consistently, students’ achievement in both subjects will likely indicate a similar level of secondary education (Böhmer et al., Citation2015), whereas inconsistent achievement will not point directly to one specific level of secondary education. Hence, it seems plausible that it is more difficult for teachers to formulate a track recommendation for these students.

Different scenarios seem possible when students’ achievement is inconsistent. Teachers can (a) place most emphasis on the subject domain with the lowest achievement (a “careful” recommendation), (b) place most emphasis on the subject domain with the highest achievement (“giving the benefit of the doubt”), or (c) aggregate achievement in different subject domains (an “aggregated” recommendation). In addition, teachers may also weigh one subject domain (i.e., language or mathematics) more heavily than the other (“a predominant subject domain”). In the Netherlands, students’ mathematics achievement seems most decisive for the level of education a teacher recommended, followed by language achievement (Driessen et al., Citation2008; Smeets et al., Citation2014).

Research on inconsistency of students’ achievement across different subject domains is scarce. Previous research primarily focused on the consistency of students’ cognitive versus socio-emotional characteristics (Böhmer et al., Citation2015; Glock et al., Citation2013), students’ grades versus standardised test scores within subject domains (Glock et al., Citation2013), or teacher judgements versus standardised test scores (e.g., Südkamp et al., Citation2012; Timmermans et al., Citation2015; Van Leest et al., Citation2021; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2016). To our knowledge, only one study by Glock et al. (Citation2013) examined the relation between inconsistencies of achievement in different subject domains and track recommendations. Glock et al. (Citation2013) conducted two different experimental procedures based on vignettes, yielding mixed results. In the first experiment, where teachers reviewed numerous student profiles simultaneously, there was no significant effect of inconsistency on track recommendations. However, in the second experiment, where teachers formulated a track recommendation for each student before moving to the next one, students with inconsistent achievement received lower track recommendations than students with consistent achievement. According to the researchers, these mixed results were likely due to the difference in experimental procedures between the two studies. Given their mixed findings and the use of vignettes, it remains unclear how inconsistencies in students’ achievement affect track recommendations of actual students.

Impact of students’ gender and SES

The effect of students’ inconsistent achievement on track recommendations can be related to their background characteristics due to differences in achievement (e.g., Timmermans et al., Citation2015; Van Leest et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2018). In the present study, we included students’ gender and SES. Prior research (Gentrup & Rjosk, Citation2018; Plante et al., Citation2013; Spinath et al., Citation2014; Uerz et al., Citation2004) indicated that boys had stronger mathematical abilities than girls, and girls had stronger language and reading abilities than boys. Therefore, it could be that achievement inconsistencies occur as often for boys as for girls, but in different directions with boys having higher mathematics than language achievement and girls having higher language than mathematics achievement. If teachers rely more often on mathematics when formulating track recommendations (Driessen et al., Citation2008; Smeets et al., Citation2014), it could be that boys receive higher track recommendations than girls with the same average achievement. Yet, it is unknown whether the effect of inconsistency on track recommendations is different for boys and girls. In addition to the indirect effects of gender on track recommendations due to inconsistent achievement, there could potentially be differences between boys and girls in track recommendations despite their achievement levels. Previous research in various countries reported mixed findings with regard to the effect of students’ gender on track recommendations. Some research (e.g., Dutch Inspectorate of Education, Citation2014; Jürges & Schneider, Citation2011; Timmermans et al., Citation2016) reported that boys received on average a lower track recommendation than girls, whereas other research (e.g., Boone & Van Houtte, Citation2013; Driessen, Citation2005; Klapproth et al., Citation2013; Krolak-Schwerdt et al., Citation2018; Timmermans et al., Citation2018; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2016) found (almost) no difference between boys and girls.

Prior research also showed differences in achievement between students with different SES backgrounds. The higher students’ SES, the better they perform on mathematics and reading comprehension, and the higher the track recommendation they receive (Caro et al., Citation2009; Van Leest et al., Citation2021). Lower-SES students specifically perform lower on language than on mathematics achievement compared to higher-SES students (Jacobs & Wolbers, Citation2018; Sirin, Citation2005; Van Leest et al., Citation2021). Thus far, it is unclear whether the effect of inconsistency on track recommendations is different for students with different SES. In addition, it has been repeatedly found in various countries that students’ SES has a small direct impact on track recommendations. That is, irrespective of students’ prior achievement, track recommendations are, on average, slightly more positive for higher-SES students than for lower-SES students (e.g., Batruch et al., Citation2023; Boone & Van Houtte, Citation2013; Caro & Lehmann, Citation2009; Driessen et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Feron et al., Citation2016; Klapproth et al., Citation2012; Korpershoek et al., Citation2016; Luyten & Bosker, Citation2004; Pit-ten Cate et al., Citation2016; Timmermans et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, p. 2016, 2018; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2017).

Present study

Because track recommendations have a strong impact on students’ future educational careers (De Boer et al., Citation2010; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2017), it is important that teachers formulate the most appropriate track recommendations according to students’ (potential) abilities (Tieben & Wolbers, Citation2010). However, it may be more difficult for teachers to formulate a track recommendation when a student’s achievement between different subject domains is inconsistent. To our knowledge, there are no studies examining the effects of achievement inconsistency on track recommendations in a naturalistic setting.

The present study addressed two research questions (RQs) in the context of inconsistency in student achievement in the Dutch educational system. The first research question was: To what extent does achievement inconsistency between reading comprehension and mathematics occur (RQ1a) and to what extent is achievement inconsistency related to students’ gender and SES (RQ1b)? In addition, we explored whether the direction of students’ achievement inconsistency (that is, in which subject domain students showed the highest performance: reading comprehension or mathematics) differed based on students’ gender and SES (RQ1c). Our second research question was to examine whether inconsistency predicted track recommendations beyond students’ gender, SES, and overall achievement (RQ2a). Furthermore, we examined whether teachers considered achievement inconsistency differently for students with different gender or SES when formulating track recommendations (RQ2b). As there may be variation between schools in how the track recommendations are formulated, we also explored whether the effects of students’ prior achievement and the achievement inconsistency on track recommendations differed between schools (RQ2c). In the absence of prior research on the topic of inconsistency, we did not formulate detailed expectations regarding the relation between inconsistency, gender, SES, and track recommendations, except for the direction of the inconsistency. Based on prior research (Gentrup & Rjosk, Citation2018; Hakkarainen et al., Citation2013; Jacobs & Wolbers, Citation2018; Plante et al., Citation2013; Sirin, Citation2005; Uerz et al., Citation2004), we expected that in case of achievement inconsistency, boys were more likely to show better achievement in math than in language, and vice versa for girls, while lower-SES students overall perform lower than higher-SES students, but specifically lower on language than on mathematics.

Method

Sample

The data used in the present study were part of a larger data set on students’ educational development across the transition from primary to secondary education, including data from an online student monitoring platform containing different kinds of information about students, such as students’ educational achievement in primary school and background characteristics (Van Leest et al., Citation2021). An organisation representing primary schools with access to this online monitoring platform downloaded and anonymized the data from schools who approved using their data.

Our sample consisted of 4,248 Grade 6 students from 101 primary schools in a large city in the Netherlands. Students were from two cohorts: students who were in grade 6 of primary education in the academic year 2014–2015 (50.4% of the sample) and 2015–2016 (49.6% of the sample).Footnote1

Dutch educational system. In the Netherlands, students attend primary school until the age of twelve (OECD, Citation2020; Smeets et al., Citation2014; Strello et al., Citation2021). Whereas primary education consists of basic education without tracking, secondary education is organized hierarchically in different ability tracks. In the final grade (sixth grade) of primary educations, students receive a track recommendation formulated by their primary school teacher for one of the six hierarchical secondary school tracks (Naayer et al., Citation2016; Smeets et al., Citation2014). Secondary schools are required to allocate students to the secondary school track determined by the track recommendation (Dutch Ministry of Education Culture and Science, Citation2014). Therefore, students are (almost) always allocated to the secondary school track indicated by their track recommendation. Students also make a mandatory nationwide school leaver’s test. However, teachers do not have access to the results of this test when formulating track recommendations due to the fact that the test is taken after teachers formulated their track recommendations (Korpershoek et al., Citation2016; Oomens et al., Citation2019). In Dutch secondary education, each secondary school track represents a different educational path, including different educational qualifications for tertiary education. Switching upwards and downwards between different secondary school tracks, i.e., intra-secondary transitions, is possible, but does not happen very often due to limited possibilities within or between schools (Jacob & Tieben, Citation2009; Lek & Van de Schoot, Citation2019; LeTendre et al., Citation2003; OECD, Citation2016; Schnepf, Citation2002; Tieben & Wolbers, Citation2010). Therefore, placement in the first year of secondary education, which is based on the track recommendation, is very decisive for students’ future educational careers.

Measures

Track recommendations. In the Netherlands, teachers formulate an initial track recommendation at the end of primary education before a school leavers’ test is administeredFootnote2, but teachers do have access to standardised test scores throughout students’ primary school career. The six secondary school tracks, from lowest to highest track, are: (1) practical training, (2) basic pre-vocational secondary education, (3) middle pre-vocational secondary education, (4) theoretical pre-vocational education, (5) senior general secondary education, and (6) pre-university education. We considered track recommendation as a continuous variable (cf. Johnson & Creech, Citation1983; Norman, Citation2010; Sullivan & Artino, Citation2013; Zumbo & Zimmerman, Citation1993).

Prior achievement. Students’ most recent reading comprehension and mathematics scores on standardised tests of primary schools’ monitoring and evaluation system were included as measures for prior achievement, as these scores are generally most predictive of track recommendations (Primary Education Council & Secondary Education Council, Citation2014). Most tests were conducted in December or January of grade 6, otherwise an earlier test, at least conducted halfway grade 5, was included. The schools participating in this study, all used standardised tests developed by Cito (the Dutch National Institute for Educational Measurement). The reading comprehension test scores range from – 87 to 147, and mathematics test scores range from 0 to 168 (Cito, Citation2016). Prior research (Feenstra et al., Citation2010; Janssen et al., Citation2010) provided support for high internal consistency (α > .80) and high validity of these tests. Because different but comparable test versions were used, the test scores were standardised for each test version to account for potential differences between test versions.

Achievement inconsistency. We computed an absolute discrepancy score between students’ standardised achievement scores in reading comprehension and mathematics (see variable prior achievement for a description of both tests) to indicate achievement inconsistency within a student. We calculated this score by subtracting students’ standardised mathematics score from standardised reading comprehension score when their reading comprehension score was higher, and vice versa. Higher scores indicated a higher level of inconsistency between the two subject domains. Achievement inconsistency ranged from 0.00 to 4.54, with 1.00 meaning that there was 1 standard deviation difference between the achievement in both subject domains.

Direction of inconsistency. Based on the variable achievement inconsistency, we also created a variable to indicate the direction of inconsistency. Students were divided into five groups: (1) students with 1–2 SD higher achievement in mathematics, and (2) students with 1–2 SD higher achievement in reading comprehension, (3) students with 2 or more SD higher achievement in mathematics, (4) students with 2 or more SD higher achievement in reading comprehension, and (5) students with less than 1 SD difference between the two subject domains (i.e., the reference group).

Gender. A dichotomous dummy variable was created for students’ gender; boys formed the reference group (50.1% of the total sample).

Socioeconomic status (SES). Students’ six-digit postal code was used as an approximation of students’ families’ SES, as this measure can be an useful marker of SES (e.g., Danesh et al., Citation1999). The SES variable was composed of three indicators, provided by Statistics Netherlands (CBS): (a) the most recent mean household income after tax, (b), the mean real estate value, and (c) the number of people who are unemployed or have social welfare benefits (Van Leeuwen, Citation2019). Using principal component analysis (PCA), the indicators were recoded into a factor score. For Dutch cities, the six-digit postal code provides a valid indication of SES, shared by only 15–20 households (Deckers et al., Citation2016; Guhn et al., Citation2010; Van Hattem et al., Citation2009). The six-digit postal codes contained missing data (39.5% of the total sample is complete). In these cases, SES was estimated based on the five-digit postal codes (97.1% of the missing values) and the four-digit postal codes (2.7% of the missing values). For 0.1% of the total sample, the postal code was completely missing. The five-digit and four-digit postal code classifications were composed of the same indicators as the six-digit postal code classification. Students’ SES is a continuous variable ranging from – 2.66 to 3.65. A higher score on this variable indicated a higher SES.

Data analyses

First, to examine the occurrence and direction of achievement inconsistency, we examined the descriptive statistics. In addition, to examine the association between (the direction of) achievement inconsistency and students’ gender and SES, we performed an independent samples t-test for gender, and a chi-squared test for SES. Second, to examine whether the inconsistency of students’ achievement predicted track recommendations beyond students’ overall achievement, gender and SES, we estimated a two-level multilevel model in SPSS 27 with students (level 1) nested in schools (level 2) (Burstein, Citation1980; Hox et al., Citation2018). To investigate the distribution of variance at both levels, an empty model with school track recommendation as dependent variable was estimated (Model 0). In Model 1, students’ prior achievement was added to investigate whether students’ achievement was a predictor of track recommendation. Next, students’ background characteristics gender and SES were added as fixed effects to examine whether students’ gender and SES were predictors of track recommendation on top of prior achievement (Model 2). In Model 3a, achievement inconsistency was added as a continuous variable to examine whether students’ achievement inconsistency predicted track recommendations. In addition, we performed an additional analysis (Model 3b) to examine whether the effects of inconsistency were related to the level and direction of inconsistency. Subsequently, we included interaction effects of students’ background characteristics gender and SES with achievement inconsistency to investigate whether the effects of inconsistency were dependent on gender or SES (Model 4). Finally, we estimated a model in which random slopes were allowed for prior achievement and inconsistency to examine whether the relationships between achievement inconsistency, prior achievement, and track recommendations differed between schools (Model 5). Explained variance (R2) was calculated for all models, including the random slopes model (cf. Snijders & Bosker, Citation2014). Effect sizes were based on standardised regression coefficients with 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 as indicative of small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation2013). To facilitate the interpretation of the results, all continuous variables were standardised prior to being included in the analyses.

The dataset contained a low percentage of missing data, varying between 0.0% and 0.2% of the total sample (see for the N of all variables). The Little’s MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) test demonstrated the data can be considered as being missing completely at random (χ2 (7) = 10.09, p = .183). In other words, missing values were not systematically related to values of other variables in the dataset, meaning that there was no sign of attrition bias. Although the percentage of missing data was low, we accounted for it by the FIML (Full Information Maximum Likelihood) method (Schafer & Graham, Citation2002). The analyses were conducted for both cohorts together.Footnote3

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of track recommendation, SES, prior achievement, and achievement inconsistency.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in , and correlations between variables are reported in .

Table 2. Correlations between achievement inconsistency, SES, gender, prior achievement, and track recommendation.

Inconsistency of students’ achievement (RQ1)

The first aim of the present study was to examine the extent to which achievement inconsistency between mathematics and language occurred across students (RQ1a), and the extent to which inconsistency was related to students’ gender and SES (RQ1b). Additionally, we explored whether the direction of students’ achievement inconsistency was different for students based on their gender and SES (RQ1c).

Concerning RQ1a on the extent of achievement inconsistency, the results (see ) indicated that students had a mean inconsistency score of 0.61, meaning that, overall, there was an inconsistency of 0.61 standard deviation between the two subject domains. There was a high significant positive correlation between students’ reading comprehension and mathematics achievement, indicating that most students perform consistently across subject domains (see ). For the majority of the students (81.4%) the difference between the two subject domains was less than one standard deviation. Hence, the other 18.6% of the students had one or more standard deviation of difference between the two subject domains. Of these students, 12.1% (i.e., 2.2% of the total sample) had a difference of two or more standard deviations between the two subject domains.

As can be seen in , there was a small significant positive correlation between students’ reading comprehension and achievement inconsistency and a small significant negative correlation between students’ mathematics achievement and achievement inconsistency, indicating that students with higher reading comprehension had higher achievement inconsistency (i.e., a larger discrepancy between reading comprehension and mathematics achievement). Of the students whose achievement differed one or more standard deviations, 52.0% performed higher in reading comprehension than in mathematics, and, consequently, 48.0% performed higher in mathematics than in reading comprehension. Of the students whose achievement differed two or more standard deviations, 71.6% performed higher in reading comprehension than in mathematics, and, consequently, 28.4% performed higher in mathematics than in reading comprehension.

Concerning RQ1b, no significant differences in achievement inconsistency between boys and girls were found (t(4239) = −0.07, p = .946), as can be seen in . As expected for RQ1c, boys performed significantly higher in mathematics (t(4241) = 6.97, p < .001) than girls, while girls performed significantly higher in reading comprehension (t(4243) = −3.98, p < .001) than boys. Furthermore, boys with achievement inconsistency (≥ 1 SD) more frequently had higher mathematics than reading comprehension achievement (66.0% of the boys), while girls with achievement inconsistency (≥ 1 SD) more frequently had higher reading comprehension than mathematics achievement (71.5% of the girls), X2 (4, N = 4241) = 75.75, p < .001. Regarding SES, a small significant negative correlation between students’ SES and the inconsistency of students’ achievement was found (see ), indicating that lower-SES students had higher achievement inconsistency compared to higher-SES students (RQ1a). Concerning RQ1b, there was no significant relation between the students’ SES and the direction of the inconsistency (that is, whether students performed higher in reading comprehension or mathematics), X2 (8, N = 4235) = 10.75, p = .217.

Inconsistency and track recommendation (RQ2)

The second aim of the present study was to examine the extent to which inconsistency of students’ achievement between reading comprehension and mathematics was associated with their track recommendation (RQ2a), and the extent to which achievement inconsistency had a different effect on track recommendations based on students’ gender and SES (RQ2b).

The results of the multilevel regression models are presented in . The results of Model 0 revealed that 29.2% of the variance in track recommendations was attributable to factors at school level, and the remaining 70.8% to factors at student level. By adding students’ prior achievement to the model, Model 1 indicated that the variance in track recommendations was primarily explained by students’ prior achievement (RModel.12 = 75.9%). As expected, students’ mathematics achievement most strongly predicted track recommendations. After accounting for prior achievement, students’ gender and SES together explained approximately 0.6% of the variance in track recommendations (RModel.22 = 76.4%). For gender, no significant effect on track recommendations was found. For SES, there was a small significant effect of SES on track recommendations, indicating that students with lower SES received lower track recommendations.

Table 3. Standardised estimates of multilevel models predicting track recommendations with prior achievement, SES, gender, and achievement inconsistency (groups).

Concerning RQ2a, the results of Model 3a illustrated that, after accounting for prior achievement, gender, and SES, the inconsistency of students’ achievement was negatively associated with track recommendations (* = -.07, p < .001). This finding suggests that teachers tended to give lower track recommendations when the achievement inconsistency between subject domains was larger. Yet, the effect size was small; on top of students’ SES, gender and prior achievement, the achievement inconsistency explained only 0.1% of the variance in track recommendations (RModel.3a2 = 76.5%).

To further examine the effects of the level and direction of inconsistency in additional analyses, students were divided into five groups based on the degree of difference between the two subject domains: (1) within 1 SD difference, (2) 1–2 SD difference mathematics higher than reading comprehension, (3) 1–2 SD difference reading comprehension higher than mathematics, (4) 2 or more SD difference with mathematics higher than reading comprehension, and (5) 2 or more SD difference reading comprehension higher than mathematics (i.e., the reference group). The results of Model 3b revealed that, when controlling for students’ prior achievement, achievement inconsistency primarily had an effect on students’ track recommendations when students had a difference between 1 and 2 standard deviations between the two subject domains. Those students received lower track recommendations than students with low achievement inconsistency (i.e., < 1 SD difference between the two subject domains). When the achievement inconsistency was large (i.e., ≥ 2 SD difference), only students with higher mathematics than reading comprehension received lower track recommendations compared to students with low inconsistency.

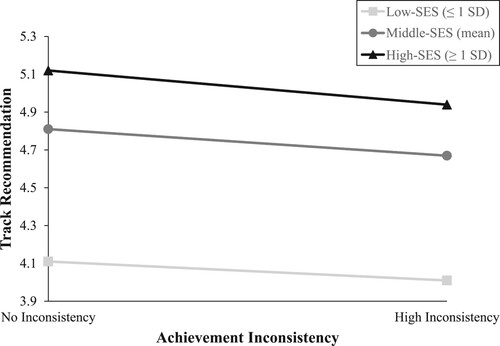

In Model 4, we added the interactions of students’ background characteristics and their achievement inconsistency to the multilevel model to examine whether the effect of inconsistency on track recommendations differed for students with different gender or SES (RQ2b). The interaction of inconsistency with students’ gender was non-significant. Hence, boys and girls with the same level of discrepancies between their achievement received similar track recommendations. Additionally, there was a small significant interaction effect of students’ SES and achievement inconsistency on track recommendations. That is, the effects of achievement inconsistency were slightly stronger for students with a higher SES. As can be seen in , this was a small effect. For presentation purposes of the figure, we divided students in three SES groups (low-SES, middle-SES and high-SES) and controlled for the variables prior achievement and gender. Even though the regression line was slightly steeper for the higher-SES group, the overall differences in track recommendations – which were mostly due to differences in overall achievement – were much larger in comparison. After accounting for students’ gender, SES, prior achievement and achievement inconsistency, the interaction effects together explained only 0.3% of the variance in track recommendations (RModel.42 = 76.8%).

Figure 1. Multilevel Regression Lines for the Effect of Students’ achievement inconsistency on track recommendations for students with different SES backgrounds.

Model 5 included random slopes for students’ prior achievement and achievement inconsistency to examine whether the effects of achievement and inconsistency differed between schools (RQ2c). The results indicated significant random slopes for prior achievement in both subject domains. Additionally, a non-significant random slope for achievement inconsistency was found, indicating that the small negative effect of inconsistency on track recommendations was similar across schools. Including random slopes added 2.3% to the explained variance in track recommendations (RModel.52 = 79.1%).

Discussion

In tracked educational systems, track recommendations determine students’ allocation in secondary education, and thereby, students’ educational careers (Glock et al., Citation2012; Strand, Citation2020). Therefore, it is important that track recommendations are based on students’ abilities and potential. It may be challenging for teachers to formulate track recommendations when students perform inconsistently across different subject domains, as their achievement will not directly indicate one particular level of secondary education. The aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which achievement inconsistency between reading comprehension and mathematics occurs, whether achievement inconsistency differs for students with different background characteristics, and how this is associated with track recommendations.

Overall, while most students performed rather consistently across the subject domains reading comprehension and mathematics, about 20% of the students performed inconsistently (i.e., ≥ 1 SD difference). Students’ achievement inconsistency played only a minor role in teachers’ track recommendations. When students performed inconsistently, track recommendations tended to be slightly lower on average. Although this effect suggests that teachers tend to give “careful recommendations” in case of achievement inconsistency, the effect was so small, it seems that teachers mostly give “aggregated recommendations” instead. Thus, teachers based their track recommendation mainly on an aggregation over students’ achievement in the subject domains reading comprehension and mathematics instead of placing emphasis on the subject domain with the lowest or highest achievement. The random slopes for this effect were not significant, indicating that this effect does not vary between schools. Hence, across different schools, teachers tend to give these aggregated, somewhat cautious, track recommendations.

Students’ inconsistency of achievement

While the overall effect of inconsistency on track recommendations was small, achievement inconsistency primarily seemed to have an effect on track recommendations, when the inconsistency itself was moderate (1 to 2 SD) to large (≥ 2 SD). Students with high achievement inconsistency whose reading comprehension achievement was lower than their mathematics achievement received lower track recommendations than students with small achievement inconsistency (< 1 SD). For students with large achievement inconsistency whose mathematics achievement was lower than their reading comprehension achievement, the effect of inconsistency on track recommendations just failed to reach significance (p = .057). This may be explained by the fact those students in general performed lower across both subject domains than other students and, consequently, already received lower track recommendations. In this case, there may be no additional effect of achievement inconsistency on track recommendation beyond students’ prior achievement. Teachers thus seemed to give more careful recommendations when the difference in achievement between the two subject domains is high, especially when students reading comprehension achievement is lower than their mathematics achievement. This could be due to the fact that the Dutch educational system is a tracked system, where students are allocated to one level of secondary education, and they take all their courses at that level. When students’ achievement is highly inconsistent, it will be extremely difficult for students to pass tests in their weaker subject domains. These findings suggest that, for these students, it might be better if they were able to take different courses at different levels, as, for example, happens in Sweden (Le Métais, Citation2003). That way, they can follow all their courses at a level that matches their abilities and prevents them from being underchallenged in their stronger subject domains.

Considering students’ achievement inconsistency in track recommendations

In line with previous Dutch research, students’ mathematics achievement appeared to be most decisive for track recommendations (e.g., Driessen et al., Citation2008; Smeets et al., Citation2014). These findings showed support for the idea that there was one subject domain most decisive for formulating a track recommendation (“a predominant subject domain”). However, these effects were small, and the results of the random slopes analyses also indicated that there was a difference between schools in the extent to which the subject domains reading comprehension and mathematics were considered when formulating track recommendations. Some schools mostly relied on students’ mathematics achievement, while other schools seemed to place more emphasis on students’ reading comprehension achievement. Consequently, two students with similar achievement levels could receive different track recommendations at different schools. Such differences between schools with regard to the (extent of) information and criteria they consider when formulating track recommendations may be considered undesirable, as students in different tracks will have very different educational opportunities, partly due to limited opportunities of switching between different school tracks (Schnepf, Citation2002; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2017). Differences between schools may be due to school characteristics or schools’ student population. Further research concerning differences between schools regarding how teachers formulate the track recommendations is needed to understand how these differences may be explained and how they impact students’ future school careers. It would also be interesting to examine whether and how guidelines for formulating track recommendations are used by schools. Such guidelines are available to schools in the region our data originates from, but it is unclear how these are being used.

Differences in track recommendations based on students’ background

In addition, as argued, it may be more difficult for teachers to formulate equal track recommendations for students given the varying achievement levels across subjects among different student groups. Regarding gender, the results indicated that the degree of inconsistency was similar for boys and girls. Yet, as expected, the achievement inconsistency of boys and girls was different in nature. Aligning with previous research (Gentrup & Rjosk, Citation2018; Hakkarainen et al., Citation2013; Plante et al., Citation2013; Uerz et al., Citation2004), we found that boys with achievement inconsistency mostly performed higher in mathematics than reading comprehension, while girls with achievement inconsistency mostly performed higher in reading comprehension than mathematics. Despite these differences, boys and girls received comparable track recommendations, and the effect of inconsistency on track recommendations was equally strong for boys and girls. Therefore, no gender effects seemed to be present when teachers formulate track recommendations. This is in line with some research (e.g., Boone & Van Houtte, Citation2013; Driessen, Citation2005; Klapproth et al., Citation2013; Krolak-Schwerdt et al., Citation2018; Timmermans et al., Citation2018; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2016), whereas some other research did find gender differences in track recommendations with girls receiving higher track recommendations than boys (e.g., Dutch Inspectorate of Education, Citation2014; Jürges & Schneider, Citation2011; Timmermans et al., Citation2016).

Concerning SES, lower-SES students performed, on average, somewhat more inconsistently than higher-SES students. Students’ SES was not related to the direction of the inconsistency, indicating that there was no difference between higher – and lower-SES students in whether they performed higher in reading comprehension or mathematics. In line with previous research (e.g., Batruch et al., Citation2023; Boone & Van Houtte, Citation2013; Caro & Lehmann, Citation2009; Driessen et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Feron et al., Citation2016; Klapproth et al., Citation2012; Korpershoek et al., Citation2016; Luyten & Bosker, Citation2004; Pit-ten Cate et al., Citation2016; Timmermans et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, p. 2016, 2018; Van Rooijen et al., Citation2017), lower-SES students received lower track recommendations than higher-SES students. This was mostly, but not completely, due to lower achievement of lower-SES students. Achievement inconsistency seemed to have a slightly stronger impact for higher-SES students than for lower-SES students. That is, teachers seemed to formulate somewhat more careful track recommendations for higher-SES students with achievement inconsistency than for lower-SES students with achievement inconsistency. This could be due to the fact that, on average, track recommendations are already higher for higher-SES students than for lower-SES students. Generally, teachers need to choose between the higher secondary tracks for higher-SES students. Consequently, when higher-SES students have achievement inconsistency, teachers may perhaps not choose the highest track, but tend toward the second-highest track. Although it was a small effect, it suggests that students with similar achievement inconsistency, but different SES may receive different track recommendations. Further research concerning these differences in track recommendations is needed to understand how these differences have an impact on students’ future school career.

Limitations

In interpreting the results of the present study, a few limitations need to be.

considered. First, in the present study, SES was measured using students’ six-digit postal code. While these six-digit postal codes are, on average, only shared by a small number of households and are therefore considered to be an accurate impression of the SES of those households (Deckers et al., Citation2016; Guhn et al., Citation2010; Van Hattem et al., Citation2009), they are not a measure of each individual household. Besides that, the six-digit classification contained missing values. For these missing values, we used the five-digit, and to a very small extent the four-digit postal codes which are less precise classifications. Therefore, these results need to be interpreted with some caution.

Second, the data was obtained from students from a large city in the Netherlands which might affect the generalisability of our results. Track recommendations can be formulated in different ways in different regions. Regions may, for example, differ in whether or not they allow combined track recommendations of two adjacent tracks. Moreover, results may also be different in other countries with different educational systems.

Third, we did not focus on the actual track placement of students, because these initial recommendations reflect primarily how teachers formulate a track recommendation, without interference of, for example, the results of a standardised school leavers’ test. Therefore, the initial track recommendations primarily reflect teachers’ inferences about students’ potential behaviour or achievement.

For future research, it would be interesting to examine the extent to which achievement inconsistency has an impact on students’ secondary school career. Although achievement inconsistency only had a minor effect on track recommendations, it is unknown how inconsistent achievement affects students’ future educational success. It could be that some students will be hindered by their subject domain with the lowest achievement, suggesting that a more careful recommendation may be suitable. In addition, it may also matter in which subject domain students with inconsistent achievement show the lowest achievement. It might be that lower achievement in reading comprehension may have more harmful effects on achievement in other subject domains, as most subjects typically rely heavily on comprehension of written texts, compared to lower achievement in mathematics. If so, careful recommendations may be more warranted in case of inconsistencies characterized by lower achievement in reading comprehension. However, prior research suggests that students who were placed in higher tracks than expected based on their performance, usually were successful in that track (Dutch Inspectorate of Education, Citation2014). If that also applies in case of achievement inconsistency, then getting “the benefit of the doubt”, that is, a track recommendation based on the subject domain with the highest achievement, seems beneficial for students’ future school careers. Furthermore, it would be interesting for future research to include other student characteristics that may be predictive of students’ future school success, such as motivation, development, work habits or classroom behaviour (Feron et al., Citation2016; Klapproth et al., Citation2012; Oomens et al., Citation2019), as well to examine the additional information such characteristics provide for formulating track recommendations.

Conclusion

The present study highlights the interplay between students’ achievement inconsistency, SES, and track recommendations. It contributes to the knowledge base on how teachers formulate track recommendations by studying the occurrence and effects of inconsistencies in achievement. The findings of the present study suggested that a tracked educational system, in which students follow all their courses at the same level, may not be appropriate for the rather substantial group of students whose achievement differs between subject domains (e.g., about 20% of the students showed a rather substantial inconsistency between subject domains). An educational system which allows for intrapersonal differences in abilities may potentially provide these students with a more suitable learning environment. Moreover, findings also indicated differences between schools in how track recommendations were formulated. Thereby, the findings also suggest a need for clearer guidelines on how to weigh different achievement indicators in students track recommendations to create equal opportunities for all students.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Renske de Kleijn and Karin van Look for their help with retrieving and selecting data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne van Leest

Anne van Leest is an assistant professor at the education department of Utrecht University. Her research interests include equal opportunities in education, teachers' judgements, and students' educational career. Her recent work focuses on teachers' track recommendations and students' transition from primary to secondary education.

Janneke van de Pol

Janneke van de Pol is an associate professor at the education department of Utrecht University and a senior researcher at the Kohnstamm Institute. Her research focuses on adaptive teaching, teacher judgements, and equal opportunities in education.

Jan van Tartwijk

Jan van Tartwijk is a full professor at the education department of Utrecht University. His research focuses on teacher education and the development of teacher expertise, teacher-students communication processes, and teaching culturally diverse classrooms.

Lisette Hornstra

Lisette Hornstra works as an associate professor at the education department of Utrecht University. Her research interests include teaching socially and culturally diverse classrooms, equal opportunities in education, and students' motivation for school.

Notes

1 In 2014, there was a policy reform of the Dutch educational system regarding the track recommendation procedures. The most important change of this reform was a changed time schedule, that resulted in not having results of the standardised school leavers' test available to teachers when formulating a track recommendation. This revised tracking recommendation procedure was followed in both cohorts from the present study.

2 In the city in which the data was collected, the initial track recommendations do not allow for combined track recommendations of adjacent tracks.

3 There were no significant differences between the two cohorts in the descriptive statistics of the variables (e.g., means, standard deviations, maximum values) (p values all > .05). Nevertheless, we also performed the multilevel analyses for both cohorts separately to check for differences between the cohorts, and no differences between the two cohorts were found. Therefore, only the combined analyses for both cohorts are reported.

References

- Batruch, A., Geven, S., Kessenich, E., & Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2023). Are tracking recommendations biased? A review of teachers’ role in the creation of inequalities in tracking decisions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 103985–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103985

- Böhmer, M., Glock, S., Gräsel, C., Hörstermann, T., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2015). Eine Analyse der Informationssuche bei der Erstellung der Übergangsempfehlung: Welcher Urteilsregel folgen Lehrkräfte? [An analysis of information search in the process of making school tracking decisions]. Journal for Educational Research Online, 7(2), 59–81.

- Boone, S., & Van Houtte, M. (2013). Why are teacher recommendations at the transition from primary to secondary education socially biased? A mixed-methods research. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.704720

- Bos, W., Lankes, E. M., Prenzel, M., Schwippert, K., Valtin, R., & Walther, G. (2004). Einige Länder der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich. [Germany in national and international comparison]. Waxmann.

- Burstein, L. (1980). Chapter 4: The analysis of multilevel data in educational research and evaluation. Review of Research in Education, 8(1), 158–233. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X008001158

- Caro, D. H., & Lehmann, R. (2009). Achievement inequalities in Hamburg schools: How do they change as students get older? School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 20(4), 407–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450902920599

- Caro, D. H., Lenkeit, J., Lehmann, R., & Schwippert, K. (2009). The role of academic achievement growth in school track recommendations. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 35(4), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2009.12.002

- Cito. (2016). Tabellen tussenopbrengsten Cito LVS. [Results of student monitoring tests in primary education]. Dutch Board of Tests and Examinations. http://www.sbzw.nl/userfiles/CITO_tabellen_tussenopbrengsten_-januari_2016.pdf

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Routledge (ed.); 2nd ed). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587.

- Danesh, J., Gault, S., Semmence, J., Appleby, P., & Peto, R. (1999). Postcodes as useful markers of social class: Population based study in 26,000 British households. BMJ, 318(7187), 843–845. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7187.843

- De Boer, H., Bosker, R. J., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. C. (2010). Sustainability of teacher expectation bias effects on long-term student performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017289

- Deckers, I. E., Janse, I. C., Van der Zee, H. H., Nijsten, T., Boer, J., Horváth, B., & Prens, E. P. (2016). Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is associated with low socioeconomic status (SES): A cross-sectional reference study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 75(4), 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.067

- Ditton, H., & Krüsken, J. (2006). Der Übergang von der grundschule in die sekundarstufe I. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 9(3), 348–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-006-0055-7

- Driessen, G. (2005). De totstandkoming van de adviezen voortgezet onderwijs: Invloeden van thuis en school. [The development of school track recommendations for secondary education: The impact of home and school]. Pedagogiek, 25(4), 279–298. https://journal-archive.aup.nl/pedagogiek/geert_driessen,_de_totstandkoming_van_de_adviezen_voortgezet_onderwijs.pdf

- Driessen, G., Doesborgh, J., Ledoux, G., Overmaat, M., Roeleveld, J., & Van der Veen, I. (2005). Van basis- naar voortgezet onderwijs. [From primary to secondary education].

- Driessen, G., Sleegers, P., & Smit, F. (2008). The transition from primary to secondary education: Meritocracy and ethnicity. European Sociological Review, 24(4), 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn018

- Driessen, G., Smeets, E., Mulder, L., & Vierke, H. (2007). De relatie tussen prestaties en advies: Onder- of overadvisering bij de overgang van basis- naar voortgezet onderwijs. [The relation between performance and track recommendation]. In Onderadvisering in beeld (Issue March). https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/211423/rapport-r1712.pdf?sequence = 1

- Dutch Inspectorate of Education. (2014). De kwaliteit van het basisschooladvies: Een onderzoek naar de totstandkoming van het basisschooladvies en de invloed van het basisschooladvies op de verdere schoolloopbaan. [The quality of the track recommendation]. https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl/binaries/onderwijsinspectie/documenten/publicaties/2014/10/14/de-kwaliteit-van-het-basisschooladvies/de-kwaliteit-van-het-basisschooladvies.pdf

- Dutch Ministry of Education Culture and Science. (2014). Toelating voortgezet onderwijs gebaseerd op definitief schooladvies. [Admission secondary education is based on final school track recommendation]. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/schooladvies-en-eindtoets-basisschool/toelating-voortgezet-onderwijs-gebaseerd-op-definitief-schooladvies

- Feenstra, H., Kamphuis, F., Kleintjes, F., & Krom, R. (2010). Leerling- en onderwijsvolgsysteem: Begrijpend lezen groep 3 t/m 6. [Student monitoring system: Reading comprehension in grade 1-6]. Cito.

- Feron, E., Schils, T., & Ter Weel, B. (2013). Test scores, teacher assessment and track placement in a secondary school system with early tracking. http://www.iwaee.org/PaperValidi2014/20140226204440_FeronSchilsterWeel.pdf

- Feron, E., Schils, T., & ter Weel, B. (2016). Does the teacher beat the test? The value of the teacher’s assessment in predicting student ability. De Economist, 164(4), 391–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9278-z

- Gentrup, S., & Rjosk, C. (2018). Pygmalion and the gender gap: Do teacher expectations contribute to differences in achievement between boys and girls at the beginning of schooling? Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(3–5), 295–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1550840

- Geven, S., Wiborg, ØN, Fish, R. E., & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2021). How teachers form educational expectations for students: A comparative factorial survey experiment in three institutional contexts. Social Science Research, 100, 1102599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102599

- Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Klapproth, F., & Böhmer, M. (2012). Improving teachers’ judgments: Accountability affects teachers’ tracking decision. International Journal of Technology and Inclusive Education, 1(2), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijtie.2047.0533.2012.0012

- Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Klapproth, F., & Böhmer, M. (2013). Beyond judgment bias: How students’ ethnicity and academic profile consistency influence teachers’ tracking judgments. Social Psychology of Education, 16(4), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9227-5

- Guhn, M., Gadermann, A. M., Hertzman, C., & Zumbo, B. D. (2010). Children’s development in kindergarten: A multilevel, population-based analysis of ESL and gender effects on socioeconomic gradients. Child Indicators Research, 3(2), 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-009-9053-7

- Hakkarainen, A., Holopainen, L., & Savolainen, H. (2013). Mathematical and Reading difficulties as predictors of school achievement and transition to secondary education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(5), 488–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.696207

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2018). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3nd Ed). Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Jacob, M., & Tieben, N. (2009). Social selectivity of track mobility in secondary schools. European Societies, 11(5), 747–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690802588066

- Jacobs, B., & Wolbers, M. H. J. (2018). Inequality in top performance: An examination of cross-country variation in excellence gaps across different levels of parental socioeconomic status. Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(1-2), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1520130

- Janssen, J., Verhelst, N., Engelen, R., & Scheltens, F. (2010). Wetenschappelijke verantwoording van de toetsen LOVS rekenen-wiskunde voor groep 3 t/m 8. [Scientific justification of the mathematics test in grade 1-6]. Cito.

- Johnson, D. R., & Creech, J. C. (1983). Ordinal measures in multiple indicator models: A simulation study of categorization error. American Sociological Review, 48(3), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095231

- Jürges, H., & Schneider, K. (2011). Why young boys stumble: Early tracking, age and gender bias in the German school system. German Economic Review, 12(4), 371–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0475.2011.00533.x

- Klapproth, F., Glock, S., Böhmer, M., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., & Martin, R. (2012). School placement decisions in Luxembourg: Do teachers meet the Education Ministry’s standards? Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal, Special 1(1), 856–862. https://doi.org/10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2012.0113

- Klapproth, F., Glock, S., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Martin, R., & Böhmer, M. (2013). Prädiktoren der sekundarschulempfehlung in luxemburg. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 16(2), 355–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-013-0340-1

- Korpershoek, H., Beijer, C., Spithoff, M., Naaijer, H. M., Timmermans, A. C., Van Rooijen, M., Vugteveen, J., & Opdenakker, M.-C. (2016). Overgangen en aansluitingen in het onderwijs. Deelrapportage 1: Reviewstudie naar de po-vo en de vmbo-mbo overgang. [Transitions and interconnections in education: Report 1]. GION Onderwijs/Onderzoek. https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/migrate/Eindrapport-405-14-402-project-1-Reviewstudie-naar-de-po-vo-en-de-vmbo-mbo-overgang.pdf

- Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Hörstermann, T., Glock, S., & Böhmer, M. (2018). Teachers’ assessments of students’ achievements: The ecological validity of studies using case vignettes. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(4), 515–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017.1370686

- Lek, K., & Van de Schoot, R. (2019). Wie weet het beter, de docent of de centrale eindtoets? [Who knows best: The teacher or the End of primary school test]. De Psycholoog, April, 10–21.

- Le Métais, J. (2003). Transition from primary to secondary education in selected countries of the INCA website. Slough, England: National Foundation for Educational Research. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264257658-en.pdf?expires=1695906386&id=id&accname=oid038041&checksum=6BD582D5E5BCD6FBD2754D42272FFDE1

- LeTendre, G. K., Hofer, B. K., & Shimizu, H. (2003). What is tracking? Cultural expectations in the United States, Germany, and Japan. American Educational Research Journal, 40(1), 43–89. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040001043

- Luyten, H. (1998). School effectiveness and student achievement, consistent across subjects? Evidence from Dutch elementary and secondary education. Educational Research and Evaluation, 4(4), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1076/edre.4.4.281.6950

- Luyten, H., & Bosker, R. J. (2004). Hoe meritocratisch zijn schooladviezen? [To what extent are track recommendations meritocratic?]. Pedagogische Studiën, 81, 89–103. https://pedagogischestudien.nl/article/view/14622/16105

- Naayer, H. M., Spithoff, M., Osinga, M., Klitzing, N., Korpershoek, H., & Opdenakker, M.-C. (2016). De overgang van primair naar voortgezet onderwijs in internationaal perspectief: Een systematische overzichtsstudie van onderwijstransities in relatie tot kenmerken van verschillende Europese onderwijsstelsels. [The Transition from Primary to Secondary ed. https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/migrate/NRO_OPRO_De-overgang-van-po-naar-vo-in-internationaal-perspectief_Opdenakker_projectleider.pdf

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y

- OECD. (2016). Netherlands 2016: Foundations for the future. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264257658-en.pdf?expires = 1695906413&id = id&accname = oid038041&checksum = 2345F995302D07468113965BA23069A7

- OECD. (2020). Sorting and selecting students between and within schools. In OECD (Ed.), Pisa 2018 results (Volume V): Effective policies, successful schools (pp. 69–86). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/ca768d40-en.

- Oomens, M., Scholten, F., & Luyten, H. (2019). Evaluatie wet eindtoetsing po. [Evaluation report of the end of primary school test policy]. https://www.oberon.eu/media/plzfih4q/evaluatie-wet-eindtoetsing-po.pdf

- Pit-ten Cate, I. M., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., & Glock, S. (2016). Accuracy of teachers’ tracking decisions: Short- and long-term effects of accountability. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0259-4

- Plante, I., De la Sablonnière, R., Aronson, J. M., & Théorêt, M. (2013). Gender stereotype endorsement and achievement-related outcomes: The role of competence beliefs and task values. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.03.004

- Primary Education Council, & Secondary Education Council. (2014). Handreiking schooladvies. [School track recommendation report] (pp. 1–9). ITS. https://www.vanponaarvo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Handreiking-schooladvies.pdf

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147

- Schnepf, S. V. (2002). A sorting hat that fails? The transition from primary to secondary school in Germany (Issue 92). https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/341-a-sorting-hat-that-fails-the-transition-from-primary-to-secondary-school-in-germany.html

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417

- Smeets, E., Van Kuijk, J., & Driessen, G. (2014). Handreiking bij het opstellen van het basisschooladvies. [Report for formulating school track recommendations]. ITS / Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1391.3929.

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2014Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling (2nd ed., p. Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Spinath, B., Eckert, C., & Steinmayr, R. (2014). Gender differences in school success: What are the roles of students’ intelligence, personality and motivation? Educational Research, 56(2), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2014.898917

- Strand, G. M. (2020). Supporting the transition to secondary school: The voices of lower secondary leaders and teachers. Educational Research, 62(2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1750305

- Strello, A., Strietholt, R., Steinmann, I., & Siepmann, C. (2021). Early tracking and different types of inequalities in achievement: Difference-in-differences evidence from 20 years of large-scale assessments. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 33(1), 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09346-4

- Südkamp, A., Kaiser, J., & Möller, J. (2012). Accuracy of teachers’ judgments of students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027627

- Sullivan, G. M., & Artino, A. R. (2013). Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5(4), 541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18

- Tieben, N., & Wolbers, M. (2010). Success and failure in secondary education: Socio-economic background effects on secondary school outcome in The Netherlands, 1927–1998. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425691003700516

- Timmermans, A. C., De Boer, H., Amsing, H. T. A., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2018). Track recommendation bias: Gender, migration background and SES bias over a 20-year period in the Dutch context. British Educational Research Journal, 44(5), 847–874. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3470

- Timmermans, A. C., De Boer, H., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2016). An investigation of the relationship between teachers’ expectations and teachers’ perceptions of student attributes. Social Psychology of Education, 19(2), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9326-6

- Timmermans, A. C., Kuyper, H., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2013). Schooladviezen en onderwijsloopbanen: Voorkomen, risicofactoren en gevolgen van onder- en overadvisering. [Track recommendations and educational careers]. GION. https://avs.nl/sites/default/files/documenten/artikelen/add/Rapport-schooladviezen-en-onderwijsloopbanen.pdf

- Timmermans, A. C., Kuyper, H., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. C. (2015). Accurate, inaccurate, or biased teacher expectations: DoDutch teachers differ in their expectations at the end of primary education? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12087

- Uerz, D., Dekkers, H., & Béguin, A. A. (2004). Mathematics and language skills and the choice of science subjects in secondary education. Educational Research and Evaluation, 10(1), 163–182. https://doi.org/10.1076/edre.10.2.163.27908

- Van Hattem, S., Aarts, M. J., Louwman, W. J., Neumann, H. A. M., Coebergh, J. W. W., Looman, C. W. N., Nijsten, T., & De Vries, E. (2009). Increase in basal cell carcinoma incidence steepest in individuals with high socioeconomic status: Results of a cancer registry study in The Netherlands. British Journal of Dermatology, 161(4), 840–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09222.x

- Van Leest, A., Hornstra, L., Van Tartwijk, J., & Van de Pol, J. (2021). Test- or judgement-based school track recommendations: Equal opportunities for students with different socio-economic backgrounds? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12356

- Van Leeuwen, N. (2019). Statistische gegevens per vierkant en postcode 2018-2017-2016-2015. [Statistical data per postal code of years 2018-2017-2016-2015]. Statistics Netherlands (CBS). https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/cbs/dossiers/nederland-regionaal/postcode/statistische-gegevens-per-vierkant-en-postcode-peiljaar-2015-en-2016.pdf

- Van Rooijen, M., Korpershoek, H., Vugteveen, J., & Opdenakker, M. C. (2017). De overgang van het basis- naar het voortgezet onderwijs en de verdere schoolloopbaan. [Transition from Primary to Secondary Education and Future Educational Career]. Pedagogische Studiën, 94(2), 110–134. https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/54246950/De_overgang_van_het_basis_naar_het_voortgezet_onderwijs_en_de_verdere_schoolloopbaan.pdf

- Van Rooijen, M., Korpershoek, H., Vugteveen, J., Timmermans, A. C., & Opdenakker, M.-C. (2016). Overgangen en aansluitingen in het onderwijs. Deelrapportage 2: Empirische studie naar de cognitieve en niet-cognitieve ontwikkeling van de leerlingen rondom de po-vo overgang. [Transitions and interconnections in education: Report 2]. GION Onderwijs/Onderzoek. https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/migrate/Rapport_Deelstudie-2-NRO_ProBO_Overgangen_aansluitingen_Opdenakker-po_vo … .pdf

- Wang, S., Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Meissel, K. (2018). A systematic review of the teacher expectation literature over the past 30 years. Educational Research and Evaluation, 24(3-5), 124–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2018.1548798

- Zumbo, B. D., & Zimmerman, D. W. (1993). Is the selection of statistical methods governed by level of measurement? Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 34(4), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0078865