Abstract

Background

Similar to other countries, Departments of Family Medicine in the former Yugoslavia had to transition from face-to-face to distance education during COVID-19.

Objectives

To elucidate obstacles and facilitators of the transition from face-to-face to distance education.

Methods

A cross-sectional, multicentre, qualitative study design was used to analyse nine open-ended questions from an online survey using inductive thematic analysis. The questionnaire was distributed to 21 medical schools, inviting them to involve at least two teachers/students/trainees. Data were collected between December 2021 and March 2022.

Results

In 17 medical schools, 23 students, 54 trainees and 40 teachers participated. The following themes were identified: facilitators and barriers of transition, innovations for enhancing distance education, convenience of distance education, classical teaching for better communication, the future of distance education, reaching learning outcomes and experience of online assessment. Innovations referred mainly to new online technologies for interactive education and communication. Distance education allowed for greater flexibility in scheduling and self-directed learning; however, participants felt that classical education allowed better communication and practical learning. Teachers believed knowledge-related learning outcomes could be achieved through distance education but not teaching clinical skills. Participants anticipated a future where a combination of teaching methods is used.

Conclusion

The transition to distance education was made possible thanks to its flexible scheduling, innovative tools and possibility of self-directed learning. However, face-to-face education was considered preferable for fostering interpersonal relations and teaching clinical skills. Educators should strive to strike a balance between innovative approaches and the preservation of personal experiences.

KEY MESSAGES

Participants found that distance education offers many possibilities, mainly self-directed, flexible learning.

Participants felt that face-to-face education remains invaluable since it facilitates communication and the development of practical skills.

A balance between new technologies and personal encounters was believed to be best.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic altered the functioning of academic institutions worldwide, with a marked impact on health professional education [Citation1]. The need for physical distancing, lockdown measures in clinical training sites, risks of potential spread or acquisition of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and an increased clinical workload challenged the inherent nature of medical education [Citation2,Citation3]. Previously predominant clinical placement-based learning and in-person didactic sessions in family medicine were substituted with alternate synchronous and asynchronous distant learning approaches to continue the education of students and family medicine trainees without compromising their safety [Citation2–6].

The change brought significant challenges to both teachers and students, with a need to master new skills and adapt to new student-group dynamics while ensuring that learning objectives were met and quality and safety of medical education preserved [Citation5,Citation6]. Similar to other countries, the seven countries of the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia) had to undergo the transition to distance education in family medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, given that family medicine is a standard part of undergraduate medical education and is also offered as a postgraduate training programme [Citation7,Citation8]. In our cross-sectional descriptive study of the transition from face-to-face to distance education in family medicine during COVID-19, among the countries of the former Yugoslavia, we found that despite limited preparedness, teachers and students made the transition to predominantly synchronous online teaching but struggled with online assessment and practical skills’ classes. [Citation9].

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the obstacles and facilitators of the transition from face-to-face to distance education during COVID-19. In addition, we explored innovations used in the transition process, plans for the future and the advantages and disadvantages of distance education. A better understanding of these issues might help educators and professional organisations identify key aspects of teaching that may lead to better quality training of students and family medicine trainees.

Methods

Study design

This study is part of a larger cross-sectional, descriptive study investigating the experience of under/postgraduate teachers and students in transitioning from face-to-face to distance education in family medicine [Citation9]. For the qualitative component, we explored how teachers/students/trainees in family medicine transitioned to distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic, and what were the obstacles and facilitators encountered during this process. We used aspects of phenomenological research to capture the ‘phenomenon’ of transitioning to distance education, and to gather opinions from participants on the future significance of distance learning. These opinions were analysed using descriptive thematic analysis, developed by Braun and Clarke [Citation10].

Recruitment and data collection

Participant recruitment took place from December 2021 to March 2022 among the Departments of Family Medicine in the countries of the former Yugoslavia. An online questionnaire, consisting of 31 questions, of which nine were open questions, was distributed to family medicine department representatives, who were asked to share the links with two family medicine teachers, students and trainees, respectively, involved in online teaching and learning during the 2020/2021 academic year. Reminder emails (sent to department representatives) and personal contacts were utilised to increase response rates, and all completed questionnaires were returned anonymously. The questionnaire was piloted in two medical faculties (Ljubljana, Split) and adapted according to the feedback received. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) were applied [Citation11]. The detailed methodology is available elsewhere [Citation9].

Participants

A convenient stratified sampling approach, consisting of a variety of learners (students/trainees) and all levels of teachers (from teaching assistants to professors), from all participating faculties and countries was used [Citation12].

The questionnaire

The open-ended questions covered the following topics: barriers and facilitators in transitioning to virtual delivery of family medicine education, what participants found rewarding about distance teaching, innovations used, experience of online assessment, the advantages and disadvantages of distance education compared to face-to-face, and intentions regarding future use of distance education. Only the teachers answered a question about achieving specific teaching objectives. Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents were also collected, including gender, age, affiliation, academic title, year of study and level of training. The questions are presented in Table S1 of the Supplementary materials.

The survey was created in 1 Ka survey online tool (www.1ka.si, version 21.11.16, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia). All responses were kept anonymous and stored securely on two servers with good system support, located at the University of Split and Ljubljana Departments of Family Medicine.

Analysis of the data

We analysed the data using descriptive analysis according to Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework: familiarisation of data, generation of codes, combining codes into themes, reviewing themes, determining the significance of themes, and reporting of findings [Citation10]. Analysis was performed by a core group of five researchers (DP, IZG, MT, VH, AS), starting with open and cross coding close to the text. Student and trainee responses were coded together while teacher responses were coded separately, and differences in the code list were discussed until agreement was reached. Codes with the same meaning, but differences in wording, were homogenised. The code list was presented to all core group members and discussed. The codes were then arranged into higher-level hierarchical units and finally into overarching themes. The process was performed over several online meetings. Shorter discussions were conducted by email. Throughout the process, we maintained the connection between the analytical content and the citations attributed to it. No software was used for data analysis.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Split, School of Medicine (Klasa: 003-08/21-03/0003; Ur. br.: 2181-198-03-04-21-0075) on 13th July 2021. All participants were informed of the purpose and content of the survey, and by commencing the survey, gave their voluntary consent to participate. Heads of Departments of Family Medicine were aware that the Ethics Committee of the University of Split had approved the study protocol, and this was considered sufficient, given the minimal risk for study participants.

Results

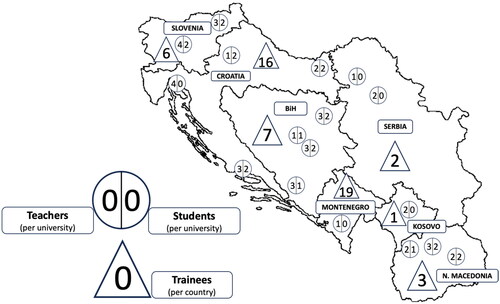

Seventeen of 21 (81%) medical schools responded involving a total of 23 students, 54 trainees and 40 teachers. Country distribution is presented in . Two-thirds (64%) of students/trainees and 78% of teachers identified as female. Most teachers (n = 26; 65%) were aged between 35 and 55 years. Three-quarters taught both students and trainees (n = 30; 75%), while 10 (25%), taught one or the other group. Most students/trainees were from Montenegro (n = 21; 27%) and Croatia (n = 22; 29%), whereas most teachers were from Bosnia and Herzegovina (n = 10; 25%) and Croatia (n = 10; 25%). A detailed description of the participants is given in our other publication [Citation9].

Figure 1. Faculties of medicine and included teachers, students and trainees in the countries of the former Yugoslavia.

*Two students did not answer the question about the location of their University.

The analysis of the open questions resulted in seven common themes, 29 subthemes for students and 38 subthemes for teachers ().

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes for students and teachers.

Facilitators and barriers to the transition to distance education

Given the need for rapid transition to distance education, technology was an essential facilitator, but frequently represented a barrier as well. One trainee listed the following technological requirements for distance education: wireless headphones, a laptop with a larger display and better camera, and a stable internet connection for all participants. (S30)

Formal instruction for teachers, namely training in usage of online tools, enabled smooth transition -- if it was timely. Students/trainees mentioned several activities offered by their institutions that were thought helpful. These included general support for distance learning, flexible teaching schedules, available materials in advance, a structured and well-organised web page for storing teaching materials, and good collaboration with teachers. One trainee stated:

Input from the faculty on how to hold classes and an agreement with the professors on the implementation details made distance learning easier. (S30)

Excessive workload in the outpatient clinic during the pandemic was a barrier (to transitioning to distance education). (T8)

Innovations for enhancing distance education

Students and trainees discovered several new possibilities for enhancing learning in a virtual environment: from attending virtual conferences to using innovative platform functions. They found these technical possibilities inspiring and conducive to interactive learning. For example, a student stated ‘I liked being able to restart lecture recordings and download learning materials’ (S13). Another student found ‘the use of Google jamboard during a virtual class was a real discovery for working in groups. A technique that facilitates interactive work!’ (S28). A trainee found ‘portals for continuing education of doctors, virtual congresses, virtual courses’ (S18) an innovative way for enhancing distance education.

Teachers used many functions offered by platforms for teaching and assessment – breakout rooms, creating a pool of questions for online tests, online quizzes – and also for communicating with students (chat function, communicating in the virtual classroom). To attract students’ attention and enhance their virtual presentations, some teachers used animation techniques, and others visual aids. For example, one teacher used ‘Survey and quizzes during class for better student participation, cameras on throughout class’ (T2), while another ‘Introduced written comments and questions via chat for students and teachers’. (T27)

Convenience and other advantages of distance education

The main benefits of distance education, described by students/trainees and teachers, were related to convenience: easier access to lessons, time saved on travel, and being able to attend classes when COVID-positive or feeling unwell. As one student stated, online learning enabled:

Less waste of time on arrival and departure from the hospital, epidemiological safety, and the possibility of attending classes even with the onset of a cold/illness. (S29)

Online teaching gave more flexibility to address different learning styles and use different technologies, plus provided comfort and the convenience of teaching from one’s own home (no need to travel and be at a certain place at a certain time). (T33)

Online accessible educational materials significantly motivated trainees to engage in self-directed learning, tailored to their individual time constraints and circumstances. As one trainee stated:

The possibility to adapt learning to some of my other obligations, especially when it came to recorded lectures that I came across unrelated to my faculty, which were useful for my education in certain fields. (S77)

Face-to-face teaching for better communication

Several advantages of classical education were described by students/trainees and teachers, from the quality of teaching and greater motivation for studying to improved communication. Better communication was experienced by participants not only between teachers and students but among students as well, as described by the following student:

Despite some subjects being better for virtual studying, I prefer the classical model because it enables better interaction not only with professors but among students. That is important for exchanging information, experience, advice, and knowledge. Online teaching distances us from each other. (S24)

Classical teaching is a hundred times better! When professors explain something in person, using gestures, you do not forget it; something you cannot experience sitting in front of a computer. (S34)

I prefer real classrooms. Communication is more personal. You can give students your full attention. Online teaching is often combined with problems with technology. (T33)

The future of distance education

Students and teachers felt that some features of distance education should be kept for teaching family medicine in the future. Specifically: having a readily accessible repositories of lectures and other teaching materials, online lectures and seminars, video-recorded clinical skills, small group work, international online presentations, and use of animations. A trainee stated:

It would be good if there was a page with all available recorded lectures, divided into topics, and one (not more) platform to connect to live lectures. (S18)

Lectures and seminars for large numbers of participants (would be good to keep). Easier to gather a large group of people and easier to follow. (S20)

Another student thought that a combination of classical and virtual learning would save them valuable time:

It depends on the timetable; if there are no practical classes on a particular day, then online lectures/seminars would provide more free time for study. (S14)

Reaching learning outcomes

Students agreed that distance teaching methods are effective in acquiring knowledge. However, acquiring skills in clinical practices represented a challenge. Nevertheless, some found virtual case presentations, coupled with simulation and interpretation of diagnostic procedures, to be partially helpful in addressing this difficulty. Teachers agreed that achieving knowledge-related outcomes was possible with online methods, as well as imparting certain attitudes. Opinions were divided when it came to teaching clinical skills, with some believing that they could be taught by video or online demonstrations, whereas others thought it was impossible. One student stated:

In the context of family medicine and virtual learning, case presentations should often be presented to students, focusing on the steps taken in examining the patient, possible laboratory tests and basic parameters, as well as imaging methods and therapy. (S24)

We cannot learn how to perform clinical skills or examine a patient virtually. With adequate IT literacy, we can attend lectures and seminars remotely without major problems. (S2)

Mostly knowledge, but skills can also be taught thanks to videos, which can be shown several times or paused for commenting. Attitudes can also be improved. (T27)

Almost anything can be achieved; one has to know how to motivate students to participate. (T3)

Experience with online assessment

Many students and trainees expressed appreciation for online assessment. As one student stated ‘Good organisation of the exam itself is essential for objective and correct virtual assessment’ (S13). Teachers’ experience with online assessment varied. Most teachers thought classical methods to be more suitable for final assessments. The main challenges were difficulty in being objective and preventing students from cheating on the exam. Thorough preparation, extra work and previous experience were thought to be needed.

Teachers and students believed virtual assessment to be inappropriate for assessing clinical skills. As one teacher stated:

Knowledge can be assessed (online), but not optimally; this requires extensive experience on behalf of the examiners. It’s impossible to assess clinical skills. (T40)

Exam.net allowed tests to be administered, but the validity of the score results was constantly questioned - so if possible, the tests should be live. For oral assessments, there is no significant advantage of in-person assessment over remote assessment. (T5)

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we gained insight into how students/trainees and teachers transitioned to distance education, what helped them in the process, what they liked/disliked about distance education and which aspects they would like to keep in the future. All participants emphasised the importance of collaboration and faculty support to achieve the best possible learning outcomes. Students/trainees expressed the need for well-organised virtual classes and a coherent structure of web pages that offer timely and readily available access to learning materials. Trainees could engage in self-directed learning opportunities by attending virtual conferences and workshops and accessing available online teaching materials. Online classes allowed for greater flexibility in scheduling, as students/trainees and teachers could more easily adapt their schedules to accommodate other obligations.

However, face-to-face education was still considered superior, particularly when it came to teaching and assessing practical skills, communicating with each other, and fostering interpersonal relations through direct communication. Proposed changes to education included hybrid methods, creating online repositories of teaching materials, conducting online lectures – including international lectures -- and small group work, using different animation and motivation techniques.

Facilitators and barriers to the transition to distance education

The immediate transition to online classes was necessary due to the characteristics of the Covid-19 pandemic and was highly dependent on available technical conditions [Citation13]. However, it was a process that required time for teachers to adapt teaching methods and to further develop technical skills [Citation14]. The teachers in our study were well aware of this and appreciated/expected support from the university, which was often lacking. The fact that teachers continued teaching, regardless of the difficult situation, was considered a success. The possibility of running classes from a remote location enabled teachers to carry out and coordinate clinical and pedagogical work during a period with an increased clinical workload.

Innovations for enhancing distance education

We found that a significant portion of teaching was delivered online, with both synchronous large-group lectures and small-group tutorials being utilised [Citation3]. Introducting new tools, such as blackboards and breakout rooms, enabled a higher quality of theoretical education. However, there were fewer attempts to provide online clinical education, and this topic was not extensively discussed in our study.

The lack of opportunities to learn practical skills and patient management was seen as the biggest limitation of distance education, both in our study and the scientific literature [Citation15]. It is clear that while distance education offers some advantages, there is still a significant need for in-person instruction for certain aspects of medical education.

A study examining the effectiveness of traditional and online learning methods revealed that students’ academic achievements were significantly influenced by their engagement level and attitude towards online learning [Citation14]. We found that students were more motivated and engaged in their education through various online techniques, including elements of gamification such as quizzes, polling questions, and online debates in breakout rooms. These findings suggest that using a variety of online teaching tools can increase student engagement and participation in the learning process and that the future might bring further development of so-called gamification techniques [Citation16,Citation17].

Classical teaching for better communication

Despite the advantages of distance learning, students preferred classical learning when it came to satisfaction with the quality of teaching, and social aspects [Citation15,Citation18,Citation19]. However, distance education was considered an acceptable alternative [Citation14]. Online communication between students and teachers through online platforms and virtual classrooms provided at least some social support for students during the pandemic [Citation13]. The social aspect of the teaching method, which includes socialising with peers and teachers, making friends, etc., was identified as an important factor in students’ academic success and well-being [Citation20]. In our study, students emphasised the importance of better face-to-face interaction with professors and among themselves in terms of exchanging information, experience, advice, and knowledge. Social interactions fostering interpersonal relationships are important positive predictors of psychological health [Citation21]. However, as mentioned by the students, face-to-face communication and social interactions can also be intensified through various online possibilities such as discussion forums, chats and virtual classrooms.

The future of distance education

Our study revealed several distance-learning methods that have the potential to remain in use post-COVID-19. These include synchronous lectures for large groups and small-group learning with various engagement techniques to keep students motivated [Citation22]. Student engagement has been emphasised more than ever, as well as the importance of continuously developing learning management systems [Citation22]. Additionally, our participants highly appreciated using teaching material repositories, although more research is needed to understand their impact on learning outcomes fully [Citation23].

Reaching learning outcomes

The satisfaction of learners, along with the transformation of their attitudes, knowledge and skills, are key outcomes of education. Distance education has been acknowledged as a successful method for both students and teachers to acquire knowledge. However, practical skills present a significant educational challenge. Notably, clinical skills training has been consistently rated as the most challenging aspect by both students and teachers, necessitating maximum adaptation and innovative approaches for effectively transferring education from a clinical environment to an online setting. Other studies have shown that various forms of telemedicine, such as following real patients via their electronic medical records have been used to replace clinical rotations. However, when it came to clinical skills training, most students felt that in-person learning was superior to online [Citation24]. Joseph et al. found that online clinical skills courses were often rated as inadequate but video recordings of interventions were seen as a helpful teaching tool for specific skills [Citation25]. Virtual ward rounds were introduced in the UK to provide clinical exposure to medical students [Citation26].

Experience with online assessment

Students and trainees expressed a positive attitude towards the validity of online assessments, whereas teachers expressed concerns about conducting summative assessments online. However, some studies have shown that online assessments with standardised test examinations, including assessing skills, can be reliable and comparable to face-to-face [Citation27,Citation28].

Strengths and limitations

We adhered to Korstjens’ four quality criteria for qualitative studies: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [Citation29]. All participants in our study had recent and active involvement in online classes. The questionnaire was carefully designed based on relevant literature, and extensive team discussions. During the pilot phase students/trainees provided feedback on the questionnaire. Data triangulation involved gathering data from diverse sources, including students, trainees and teachers from over 80% of medical faculties in the former Yugoslavia. Although some countries had more participants than others, we believe the diversity of included participants was satisfactory. We ensured transferability by capturing participants’ opinions, experiences and contexts maintaining reflexivity throughout the analysis with numerous discussions among researchers during coding and concept construction. The research process encompassed all necessary stages, ensuring reliability and validation.

However, the study has several limitations. While the online format allowed for an international sample, it may have resulted in less detailed responses than in-person interviews. The regional focus restricts insight into other distance education approaches. Furthermore, there was lower representation of students compared to trainees and teachers, e.g. students were not asked about reaching learning goals, possibly leading to a lack of specific student experience. Finally, the questions mainly focused on didactic classes; detailed feedback on clinical rotations and practical classes was not gathered.

Conclusion

The transition to distance education was made possible, thanks to its flexible scheduling, innovative tools and possibility of self-directed learning. However, face-to-face education was considered preferable for fostering interpersonal relations and teaching clinical skills. The challenge is how to combine the advantages of distance learning best with the necessary development of interpersonal relations and acquisition of clinical competencies. Educators should strive to strike a balance between these two methods.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Ana Marušić for critically reviewing our questionnaire. We are grateful to our esteemed colleagues for assisting with data collection: Olivera Batić-Mujanović, Edita Černi Obrdalj, Ines Diminić Lisica, Larisa Gavran, Zaim Jatić, Zalika Klemenc-Ketiš, Ilir Mencini, Branislava Milenković, Milena Rovčanin Cojić, Katarina Stavrić, Ljiljana Trtica Majnarić, Matilda Vojnović. We want to acknowledge all the medical students, family medicine trainees and teaching staff for their contributing to this research.

Disclosure statement

The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, et al. Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 63. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1807484.

- Windak A, Frese T, Hummers E, et al. Academic general practice/family medicine in times of COVID-19– perspective of WONCA Europe. Eur J Gen Pract. 2020;26(1):182–188. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2020.1855136.

- Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227.

- Khamees D, Peterson W, Patricio M, et al. Remote learning developments in postgraduate medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic - a BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 71. Med Teach. 2022;44(5):466–485. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2040732.

- Veerapen K, Wisener K, Doucet S, et al. A scaffolded structured approach for efficient transition to online small group teaching. Med Educ. 2020;54(8):761–762. doi: 10.1111/medu.14209.

- Daniel M, Gordon M, Patricio M, et al. An update on developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a BEME scoping review: BEME guide no. 64. Med Teach. 2021;43(3):253–271. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1864310.

- Zakarija-Grković I, Vrdoljak D, Cerovečki V. What can we learn from each other about undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine? Slovenian J Public Health. 2018;57(3):148–154. doi: 10.2478/sjph-2018-0019.

- European Academy of Teachers in General Practice [Internet]. Specialist training database. 2016 [cited 2023 July 15]. Available from: https://euract.woncaeurope.org/specialist-training-database.

- Zakarija-Grković I, Stepanovic A, Petek D, et al. Transitioning from face-to-face to distance education. Part 1: a cross sectional study in the former Yugoslavia during COVID-19. Eur J Gen Pract. 2023;2023:1.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Soc Res Online. 2004;9(4):177–180.

- Arja SB, Wilson L, Fatteh S, et al. Medical education during COVID-19: response at one medical school. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2021;9(3):176–182.

- Omole AE, Villamil ME, Amiralli H. Medical education during COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative effectiveness study of face-to-Face traditional learning versus online digital education of basic sciences for medical students. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e35837. doi: 10.7759/cureus.35837.

- Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, et al. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042378. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378.

- Lumsden L, Cannon P, Wass V. Challenge GP: using gamification to bring the reality and uncertainty of a duty doctor’s surgery to early year medical students. Educ Prim Care. 2023;30:1–6.

- Rutledge C, Walsh CM, Swinger N, et al. Gamification in action: theoretical and practical considerations for medical educators. Acad Med. 2018;93(7):1014–1020. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002183.

- Bączek M, Zagańczyk-Bączek M, Szpringer M, et al. Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study of polish medical students. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(7):e24821. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024821.

- Thind AS, Singh H, Yerramsetty DL, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on caribbean medical students: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;67:102515.

- Torda A, Shulruf B. It’s what you do, not the way you do it - online versus face-to-face small group teaching in first year medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):541. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02981-5.

- Velikonja NK, Erjavec K, Verdenik I., et al. Association between preventive behaviour and anxiety at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Slovenia. Slovenian J Public Health. 2020;60(1):17–24., doi: 10.2478/sjph-2021-0004.

- Khan RA, Atta K, Sajjad M, et al. Twelve tips to enhance student engagement in synchronous online teaching and learning. Med Teach. 2022;44(6):601–606. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1912310.

- Jeong D, Presseau J, ElChamaa R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to Self-Directed learning in continuing professional development for physicians in Canada: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(8):1245–1254. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002237.

- Franklin G, Martin C, Ruszaj M, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic impacted medical education during the last year of medical school: a class survey. Life (Basel). 2021;11(4):294. doi: 10.3390/life11040294.

- Joseph JP, Joseph AO, Conn G, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic-Medical education adaptations: the power of students, staff and technology. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1355–1356. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01038-4.

- Sangha MS, Hao BZ. Innovation in medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the future. Med Teach. 2022;44(3):335–336. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1934426.

- Gu S, Yuan W, Zhang A, et al. Online re-examination of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03100-8.

- Bouzid D, Mullaert J, Ghazali A, et al. eOSCE stations live versus remote evaluation and scores variability. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):861. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03919-1.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092.