Abstract

Many authors have argued that International Public Administration can influence policy-making through their expert authority. The article compares de jure and de facto expert authority of IPAs to evaluate their conformity. It comparatively assesses the two kinds of authority for five important IPAs (BIS, FAO, IMF, OECD and World Bank) active in agriculture or financial policy. It shows that, on average, de jure and de facto authority seem to conform. At the same time, it demonstrates that gaps between de jure and de facto authority exist at the level of the IPAs, the policy areas and the IPAs’ addressees.

Introduction

Many authors have argued that International Public Administrations (IPAs) can influence global and domestic policy-making through their authority (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Hooghe and Marks Citation2015; Bayerlein et al. Citation2020a; Goritz et al. Citation2020).Footnote1 Expert authority is a form of power that is based on voluntary deference to the knowledge-based requests of the authority holder (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Zürn Citation2018). This article builds upon the conceptual distinction between de jure authority and de facto authority and explores the question of how they are related empirically. De jure authority typically captures the extent to which states approve formal rules that delegate authority to IPAs. De facto authority is the recognition of and deference to this authority in practice (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004, p. 25). Scholars have long suspected that there might be gaps between the two forms of authority or that they are even unrelated (Hurd Citation2008; Alter et al. Citation2016; Krisch Citation2017; Sending Citation2017).Footnote2 To evaluate this argument, we ask: To what extent does IPAs’ de facto expert authority conform with their de jure expert authority?

Empirically, this article compares de jure and de facto authority of five IPAs in two policy areas. It links data on de jure authority, as measured by two major data collection efforts (Hooghe et al. Citation2017; Zürn et al. Citation2020), with original data on the de facto expert authority of IPAs. It evaluates the de jure and de facto expert authority of five centrally important IPAs, active in eight thematic fields in financial or agricultural policy: Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank. It assesses these IPAs using data from a global survey through which national bureaucratic units from over 100 countries evaluated the five IPAs in 2016.

The article illustrates that, on aggregate, IPAs with more de jure expert authority also have more de facto expert authority. However, comparative analysis also reveals that de jure and de facto expert authority do not always conform. We call these situations authority gaps. Some IPAs in some policy areas are characterised by positive authority gaps – they enjoy more authority de facto than de jure. Other IPAs are characterised by negative authority gaps – they enjoy less authority de facto than de jure. These patterns are shown through analysing three units of analysis, the IPA, different policy areas and different addressees.

The article makes two central contributions to the literature. First, it adds to the literature on international authority (Hooghe et al. Citation2017; Krisch Citation2017; Zürn Citation2018) through demonstrating empirically that authority gaps exist and that they vary on three levels of analysis: the global level, the policy level and the level of the addressees. While many authors have suspected that the two forms of authority are not always in conformity, we demonstrate gaps by use of novel survey data. Second, it contributes to the literature on IPAs (Eckhard and Ege Citation2016; Knill and Bauer Citation2016; Bayerlein et al. Citation2020b; Eckhard & Parizek Citation2020) by illustrating that they hold expert authority over national administrative units. This expert authority is not always related to their formal delegation and can give IPAs the potential to influence decisions in national administrations.

The article proceeds as follows. First, it identifies important similarities amongst authority concepts in existing studies and introduces the concept of authority that guides our analysis. Second, it discusses the argument that de jure and de facto authority might not always conform and presents explanations given in the literature on three levels of analysis: the IPA itself, different policy areas and addressees. Third, it compares our novel survey data with existing measures of authority. Finally, it concludes by summarising our main observations and by outlining their implications for the comparative study of expert authority of IPAs.

What Is Expert Authority, and How Does It Manifest?

Research on national administrations highlights the role of expertise in empowering national bureaucracies. These studies have mainly focused on the superior command of issue-specific knowledge that bureaucrats have due to their professional training or work experience (Atfield and Miller Citation1984; Bendor et al. Citation1985; Gailmard and Patty Citation2007; Liu et al. Citation2017). They have analysed, for example, how superior knowledge can give bureaucrats strategic opportunities to influence the choices of political principals (Atfield and Miller Citation1984; Bendor et al. Citation1985), and how different kinds of knowledge shape the decisions and motivations of bureaucrats (Gailmard and Patty Citation2007; Liu et al. Citation2017). These studies often focus on how the delegation of specific tasks requires expertise to be developed by bureaucratic agents and that this knowledge has certain consequences for political–administrative relationships and the fulfilment of tasks of national bureaucracies.

Studies of IPAs agree with the national administration literature in so far as they regard the possession of specialised knowledge as a core characteristic of IPAs and the main reason why political principals delegate power to the IPA (Hawkins et al. Citation2006; Knill and Bauer Citation2016). At the same time, the literature has also argued that IPAs can hold expert authority (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Zürn Citation2018). This expert authority is more than the possession of knowledge. Rather, the concept is based on Weber’s insights (Citation1980) that recognised expertise can be a source of power. Expert authority is commonly understood as a form of power that induces voluntary deference to knowledge-based requests of a certain actor (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Zürn Citation2018). Within IOs, IPAs are usually the main holders of expert authority because they generate, process, communicate and guard the knowledge from which expert authority is derived. An IPA may use its expert authority to inform and guide policies, to legitimise policy choices, to depoliticise actions and decisions, or to substantiate policy positions (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017). Expert authority is typically defined as the recognition of and deference to knowledge-based requests of IPAs (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017). In other words, authority addressees recognise that an IPA can make competent knowledge-based requests and defer to these requests by considering to take or by taking related actions or decisions.

Conceptualising and operationalising any type of authority is not an easy task. The operationalisation and measurement of authority struggles with the problem of observational equivalence (Hurd Citation2008; Lake Citation2010). One faces the difficult task to distinguish authority from other forms of power empirically. That said, existing studies increasingly agree on several elements that are seen as essential in conceptualising and operationalising authority. We base our concept of expert authority on these elements.

The study of international authority largely converges around an understanding of authority as a distinct form of power that is based on a social and hierarchical relationship. Several definitions of authority reflect this understanding, which is often derived from Weber’s concept of authority (Weber Citation1980) and similar work in political philosophy (Friedman Citation1990; Viehoff Citation2016). The social and hierarchical relationship manifests between an authority holder, in our case the IPA, and its addressees. Addressees are any actors that are targeted by IPAs’ activities. In the authority relationship, addressees recognise the privilege of an IPA to request certain actions and defer to these requests (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Krisch Citation2017). This understanding of the concept is widely shared in the literature (Lake Citation2010; Krisch Citation2017). The notion of deference is important for two reasons. First, deference implies that authority addressees refrain from a thorough preference-based examination of the content of requests by authority holder when they subordinate their behaviour to said requests. Instead, actors subordinate because they believe in certain qualities of the IPA (Zürn Citation2018). These qualities may include, for example, an authority holder’s general reputation, trustworthiness, credibility, overall utility, expert knowledge or performance. In other words, it is the source of the claim, not its contents, that sways addressees (Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2012). Second, deference is used to distinguish authority from other forms of power. In the prevailing view, deference involves a specific motive for subordinating to requests of IPAs that differs from the motives when actors are coerced or persuaded to take certain actions and decisions (Krisch Citation2017). When coerced, actors adapt their behaviour to a specific request of an IPA because they fear sanctions or other enforcement measures (Hurd Citation2008). In the case of persuasion, they do so because they thoroughly examined the content of the specific request, assessed its advantages in light of their interests and preferences and scrutinised the supporting arguments (Ecker-Ehrhardt Citation2012).

In addition, most authors emphasise that authority is not the same as compliance or performance. Authority is a property of the relationship between an authority and its addressees. First, authority can lead to compliance, but there are other ways to induce compliance with requests, like the discussed persuasion or coercion. In any authority relationship, authority addressees have “a certain degree of freedom to act otherwise” (Krisch Citation2017, p. 242). Hence, they might not always change their behaviour in line with an IPA’s requests even when they consider the IPA as an expert authority. An IPA can still enjoy authority even if its addressees do not always comply with its requests (Hurd Citation2008). Second, authority is not the same as high performance of the IPAs in their tasks. IPAs’ performance can be understood as the output, outcome or impact of IPAs (Gutner and Thompson Citation2010; Tallberg et al. Citation2016). Holding expert authority can empower IPAs to perform better. Nevertheless, performance refers to the quality of a given IPA action, while authority is a feature of the IPA itself. Indeed, there are important cases where IPAs used their authority in ways that ended up being detrimental to the performance of their tasks (Barnett Citation2002).

Moreover, most authors specify in what way authority addressees recognise and defer to the requests of IPAs. We find a variety of labels, such as delegated, de jure, de facto, legal, sociological, authority de facto or authority in principle. These labels mirror linguistic more than conceptual diversity. One group of labels (de jure, delegated, legal) captures the contractual understanding of authority in which the authority relationship becomes manifest in formal ways. These are usually written down in one way or another. The other group of labels (de facto, sociological) grasps the sociological understanding of authority in which authority becomes manifest in behavioural ways. We use the terms de jure authority and de facto authority to distinguish these two basic understandings on how authority becomes manifest (Green Citation2014; Alter et al. Citation2016; Busch and Liese Citation2017). De jure recognition, on the one hand, captures the contractual or formal–legal understanding of the authority relationship, where the IO or its IPA are put “in authority” (Friedman Citation1990) by the subordinate actors. De jure recognition means that actors formally acknowledge the IPA’s competence by making a joint decision to adopt legal rules that transfer specific powers to a particular IO. These actors subsequently promise to subordinate their acts to the decisions taken in said IO in the future. This form of authority becomes manifest in the formal structures and the legal mandate of IPAs. It is a relationship between states as principals and an IO, including its IPA, as agent (Hawkins et al. Citation2006; Hurd Citation2008).

De facto authority, on the other hand, captures the sociological understanding of the authority relationship, where the IPA is made “an authority” (Friedman Citation1990). Recognition of and deference to the IPA needs to be observable in present behaviour (Alter et al. Citation2016). An IPA, therefore, has de facto authority when it is observable that actors change or at least consider changing their behaviour based on requests of the IPA. The major difference between de facto authority and de jure authority is that de jure authority denotes a legal nominal recognition of authority. In contrast, de facto authority describes behavioural recognition.

De jure and de facto authority do not always conform. We use the term authority gap to describe these situations. Some scholars argue that assessments of de jure authority need to be complemented by assessments of de facto authority. They stress that it cannot be taken for granted that the delegation of authority to IPAs is followed by deference and warn that, in the worst case, delegated authority might only exist de jure (Friedman Citation1990; Hurd Citation2008; Krisch Citation2017; Sending Citation2017). States may reconsider or revoke the act of delegation at any time or simply decide not to defer (Hurd Citation2008). What follows from this debate is that de jure and de facto authority might deviate or even be entirely unrelated.

When taking the arguments of possible gaps between de jure and de facto authority seriously, one arrives at four different configurations of de jure and de facto authority (). First, IPAs may enjoy neither de jure nor de facto authority. Second, they can enjoy both. Third, IPAs that enjoy de jure authority are not necessarily recognised as an authority and deferred to de facto (negative authority gaps). Fourth, one may expect to find IPAs that have little authority de jure but which are de facto quite authoritative in their relationships with member states (positive authority gaps).

Table 1. Different possible authority configurations

So far, we have conceptualised the different elements of expert authority and the different configurations of de jure and de facto authority. Case studies of a range of IPAs substantiate these theoretical configurations. Authors have discussed positive authority gaps (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Bauer Citation2008; Hanrieder Citation2015; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017) and negative authority gaps (Sharman Citation2008; Best Citation2014; Edwards and Senger Citation2015) for several IPAs in specific cases. In order to better understand how authority gaps can emerge, we now turn to discuss what explanations these studies have provided for gaps in expert authority.

Why and How Gaps in IPAs’ Expert Authority Emerge

Authors have provided a range of explanations of the emergence of authority gaps of IPAs. These explanations focus on the IPAs themselves, specifics about the policy areas the IPAs are active in, and country-level variations. The first group of explanations focuses on the IPA itself and how it can extend its authority. These authors emphasise on task ambiguity, bureaucratic entrepreneurship, performance and impartiality as important drivers of authority gaps (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Sharman Citation2008; Best Citation2014; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017). Task ambiguity can extend IPAs’ authority. Barnett and Finnemore (Citation2004) argue that the IMF’s IPA has extended its reach and actions substantially beyond the originally intended competences imagined by its founders. The territory the IMF was commissioned to work in was unknown to the IMF staff. In response, the IMF research department developed problem-solving theories that not only allowed but necessitated involvement with formerly national economic policy. In addition, positive authority gaps can emerge at the initiative of staff members building up expertise on certain issues. For example, Littoz-Monnet (Citation2017) argues that building up expertise in new issue areas has expanded the expert authority of UNESCO. She illustrates how the IPA has expanded its expert authority because bureaucratic entrepreneurs inside the IPA developed expertise and technical skills on bioethics, even though it was not a part of UNESCO’s mandate. However, IPAs can also lose de facto authority which creates negative authority gaps – for example, when they lack impartiality. Sharman (Citation2008) argues that the reason why the OECD or the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) have decreased their use of blacklists as policy tools is because they suffered losses in expert authority due to the political nature of these blacklists. Another example for negative authority gaps is highlighted by Best (Citation2014), who argues that the Asian financial crisis and lack of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa led to an erosion of the expert authority of the IMF and World Bank. In response, they aimed to restore their authority by changing their policy paradigms to incorporate more diverse policy areas. These three explanations focus on factors that are innate to different IPAs. However, IPAs can also take advantage of certain specificities in the policy areas they are active in, as discussed by the next set of arguments.

The second group of explanations concentrates on differences in the policy areas within which IPAs are active. Explanations focusing on policy area characteristics emphasise the role of issue complexity and emerging opportunity structures within an issue area. IPAs can extend their authority beyond formal means if they work in complex regimes. For example, Bauer (Citation2008, p. 67) argues that issue complexities can serve to empower IPAs to generate positive authority gaps. UNEP’s ozone secretariat was able to use its technical expertise over the specific dimensions of the ozone regime and turn into “an authoritative and indispensable player in international ozone politics”. Furthermore, IPAs can utilise opportunity structures within their issue areas to further their authority. For example, Hanrieder (Citation2015) points to changes in the opportunity structures that allowed the WHO to expand its expert authority. She argues that the IPA was able to successfully position itself as a clearinghouse for rumours of outbreaks of diseases in the 1990s, when diffusion of information technology made containing such information increasingly difficult. Drawing on its expert authority, it did so by reference to its broad professional network and nearly universal membership. As Hanrieder (Citation2015, p. 207) puts it: “for the WHO Secretariat, these new sources of information were a welcome opportunity to enhance its authority”. These two studies show how IPAs can build more authority by engaging with specific developments in their policy areas. However, authority gaps can also be a function of factors on the level of authority addressees.

The third group of explanations highlights that authority gaps can occur because of differences in interest, power and capacity of authority-granting addressees. Some addressees might be less inclined to listen to outside expertise than others. For example, Edwards and Senger (Citation2015) raise doubts about whether de jure authority of the IMF that has been delegated to it in the context of Article IV consultations translates into de facto expert authority in, at least some, developed countries. During these consultations, the IPA meets regularly with national policy-makers to discuss the state of the economy and give policy recommendations. Edwards and Senger (Citation2015) use the case of Article IV consultations with the US and the debate around the debt ceiling in the USA in 2010–2011. They investigate whether IMF policy advice, given during these consultations, influences public debates in the US. Although the IMF thus has de jure authority to advise national policy-makers in the US on economic issues, the authors find little evidence for de facto authority. US policy-makers did not use the IMF Article IV consultations in justifications of policy proposals.

We draw upon these three levels of analysis (IPA, policy, addressees) in the empirical part of the article. Before we turn to the findings, we discuss how one can empirically grasp differences in de jure and de facto authority.

Measuring De Jure and De Facto (Expert) Authority of IPAs

Recent years have seen substantial advances in data collection on the authority of IPAs. These advances have resulted in several large-scale comparative studies. They are the Measuring International Authority database by Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) and the International Authority Dataset by Zürn et al. (Citation2020). In order to reveal whether and how de jure and de facto expert authority of IPAs are related, we contrast their findings with our data on de facto expert authority. This comparison offers a way to assess the relationship between IPAs de jure and de facto expert authority.

Content Analysis to Measure De Jure Authority

Before comparing the measures, we briefly introduce the two datasets. Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) measure the delegation to the 74 IPAs between 1950 and 2017. Their data is based on hand-coding of the “treaties, constitutions, conventions, special statutes, protocols, and rules of procedure” (Hooghe and Marks Citation2015, p. 314) of global and regional IOs. It enables singling out IPAs and thereby assessing their de jure authority. They measure the delegation of authority to the respective IO bodies by coding six decision domains: membership accession, membership suspension, constitutional revision, financial non-compliance, drafting the budget and policy-making. The delegation score is based on the agenda-setting competencies of the respective IPAs in each of these domains as well as indicators on whether IPAs are formally the executive and whether they have a monopoly of policy initiation (Hooghe and Marks Citation2015). Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) do not explicitly differentiate between expert and political authority even though they code authority in areas that come close to what is understood as expert authority (recommendations, resolutions and declarations). It is not possible to disaggregate their data to the point where one would get an authority score for IPAs for only this question. Nevertheless, we use their indicator to measure delegation to the IPA (Hooghe and Marks Citation2015) as an indicator for de jure authority of IPAs.

Like Hooghe et al. (Citation2017), Zürn et al. (Citation2020) also measure de jure authority of IOs, using a representative sample of 35 IOs and covering the period from 1919 to 2015. They also hand-code the content of a large number of IO documents and treaties based on a comprehensive list of 150 questions. Zürn et al. (Citation2020) distinguish political and expert authority (called “epistemic authority”). Specifically, they identify seven functions IOs perform and classify them according to political or expert authority. They catalogue agenda setting, rule-making, monitoring and enforcement as parts of political authority. The interpretation of norms, the evaluation of IOs, and the generation of knowledge are assigned to expert authority. They then assess for each function the IO’s degree of autonomy from its member states and the degree to which its decisions are binding. They do not distinguish different IO bodies, which means that it is not possible to single out de jure expert authority of IPAs specifically. That said, IPAs are usually the bodies within IOs that are chiefly responsible for the functions assigned to epistemic authority. Therefore, we consider the data of Zürn et al. (Citation2020) a close approximation to de jure expert authority of IPAs.

Survey-based Approach to Measuring De Facto Authority

In order to assess de facto expert authority and to single out IPAs as holders of that authority, we conducted a survey among domestic high-level civil servants. This approach has two key advantages. First, a survey promises to overcome the problems of observational equivalence. Surveys offer an opportunity to directly ask stakeholders for their recognition of and deference to an IPA’s request, instead of deriving these from other factors like behavioural consequences of the exercise of authority. This method, therefore, also enables one to distinguish expert authority from other forms of power or related concepts (Liese et al. Citation2017).

We decided to focus on one group of respondents to be able to make inferences about a larger group of similar actors. Consequently, we had to choose a single group of respondents. We decided to focus on high-level civil servants as survey respondents because they are seen as crucial interlocutors for IPAs in the literature (Woods Citation2006; Broome and Seabrooke Citation2015; Heinzel et al. Citation2020). They are “gate-keepers of policy research and analysis” in their respective countries (Doberstein Citation2017, p. 398). The importance of relationships between IPAs and national administrations have also been identified by scholars working on multilevel administrations (Egeberg and Trondal Citation2009; Benz et al. Citation2016) and the influence of globalisation on national administrations (Bauer et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the expert authority IPAs hold over them is very relevant for the performance of IPAs functions.

Our survey focused on eight thematic fields in agriculture and financial policy. This focus is based on qualitative research that highlights differences of authority between policy areas (Littoz-Monnet Citation2017). Furthermore, we wanted to allow respondents to evaluate the specific thematic fields they work on rather than to share with us broad views of different IPAs. We decided to focus on agriculture and financial policy as both are important areas of domestic policy-making where several IPAs are communicating their advice to national administrations. The survey was targeted at the highest civil servant in each ministry or central bank which were solely responsible for eight thematic fields in 121 countries. We chose the countries for the study using a stratified sampling process that focused on representativeness across United Nations regions and World Bank income classifications. We received 1,785 individual responses from 106 countries, which equates a response rate of 38 per cent.Footnote3

We chose IPAs that were active in the eight thematic fields and claimed expert authority over them by giving policy advice to consider in domestic policy-making. We evaluated whether they did so by reviewing websites, publications and policy documents of the respective IPAs. We report only the findings on the de facto expert authority of five global IPAs (BIS, FAO, IMF, OECD, World Bank) that are also covered in the datasets of Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) and Zürn et al. (Citation2020).Footnote4

In order to measure de facto authority, the survey asked the following question: “Thinking of all of the policy advice that, to your knowledge, has been provided by each of the following secretariats in banking regulation policy: How much of this policy advice has been taken into account specifically because your unit perceives the respective secretariat to be an expert in thematic field, whose policy advice can be considered without further examination? Please give a rough estimate for the last 24 months.” We constructed the question to correspond to the theoretical elements of expert authority discussed above. These include references to the expertise (considers the respective secretariat to be an expert) and to deference (whose policy advice can be considered without further examination). Respondents indicated their answers on a scale of one (no advice) to seven (all advice). A value of one indicates low expert authority and a value of seven high expert authority.

To compare the de facto expert authority scores with the data on de jure authority, we built two kinds of means. First, we built a mean score for each of the eight thematic fields. In a second step, we aggregate these scores to a global expert authority score for the whole IPA. We use data from 2014 for both Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) and Zürn et al. (Citation2020), to use values that immediately precede the period survey respondents were asked to evaluate.

Authority Gaps? Comparing De Jure and De Facto Authority of IPAs

To identify authority gaps, we compare the findings of our survey with de jure authority as measured by Hooghe et al. (Citation2017) and Zürn et al. (Citation2020). Do they conform, or can we observe gaps? We discuss the three levels of analysis identified in the theoretical discussion in turn: IPA, policy area and addressees.

We do so in two steps in each of the three levels of analysis. First, we plot the results regarding de jure and de facto expert authority against each other. Second, we categorise the cases into a two by two matrix to identify gaps and conformity. To identify gaps, we need to differentiate between IPAs with high authority and IPAs with low authority. This requires the definition of a cut-off point. First, we decide to focus on the actually observed rather than the theoretically possible value of authority. We do so because we are interested in the authority that IPAs have actually reached rather than what is judged as theoretically possible by the different data collection efforts. Therefore, we decide to use the mid-range of values among our five IPAs as a cut-off point, which is calculated by taking the average of the maximum and minimum value. While some might disagree with this choice, we also display the results graphically so that readers could make different choices when defining a cut-off point.

Authority Gaps at the IPA Level

The first level of analysis is the level of each IPA. plots de jure and de facto expert authority of IPAs comparing the aggregated survey results with the data collected by Hooghe et al. (Citation2017), focuses on the data presented by Zürn et al. (Citation2020). We used min–max transformation in order to collapse all three measures to the same scale.

Figure 2. De jure expert authority compared with de facto expert authority (Zürn et al. Citation2020)

Overall suggests that the de facto expert authority of IPAs tends to increase with their general de jure authority (Hooghe et al. Citation2017). A similar picture emerges in , which focuses on de jure expert authority (Zürn et al. Citation2020). Differences between IPAs in de facto expert authority seem to follow differences in de jure authority. However, there also are some gaps. Specifically, the OECD achieves less de facto expert authority than other IPAs that have less authority de jure.

We now identify these gaps by splitting the sample into two groups (above and below the midrange value). Subsequently, we use the data by Zürn et al. (Citation2020) because of its focus on expert authority. displays the configurations of high and low expert authority we observe at the global level. The BIS and World Bank achieve positive authority gaps. However, these gaps are small as both the BIS and the World Bank are just slightly above the cut-off point we defined for de facto expert authority. While some gaps exist at the global level, we also find a substantial degree of conformity between the two kinds of expert authority discussed throughout this paper.

Table 2. Different observed authority configurations IPA level

Authority Gaps in Agriculture and Financial Policy

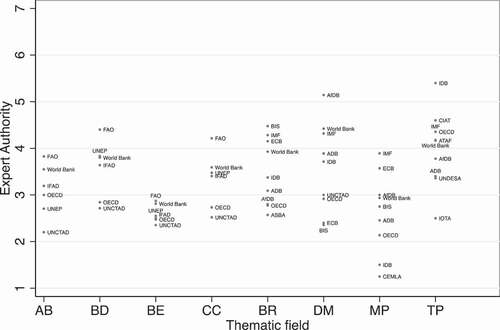

We now turn to the two policy areas. The two policy areas we focus on include four thematic fields each. In agriculture, these are agribusiness, biodiversity, bioenergy and agricultural policies on climate change (). In financial policy, the thematic areas are banking regulation, debt management, monetary policy and tax policy (). Overall, we observe that in the majority of thematic fields, an IPA’s de facto expert authority is in conformity with de jure expert authority. There is no exception to this trend in agribusiness policies, biodiversity, climate change and debt management. However, in bioenergy and tax policy, we observe gaps. In these two areas, IPAs enjoy more or less the same level of de facto expert authority. At the same time, de jure expert authority of the IOs to which they belong varies substantially.

Figure 3. De jure expert authority and de facto expert authority in agriculture (agribusiness (AB), biodiversity (BD), bioenergy (BE) and agricultural policies on climate change (CC))

Figure 4. De jure expert authority and de facto expert authority in finance (banking regulation (BR), debt management (DM), monetary policy (MP) and tax policy (TP))

What is also apparent is that some IPAs vary in their de facto authority across thematic fields. For example, the OECD is among the strongest expert authorities in tax policy, while it is around the bottom of the table in all other thematic fields. This is in line with the literature on the role of the OECD in tax policy, which has highlighted its role as an “informal world tax organization” (Cockfield Citation2006, p. 136) and the importance of the OECD’s IPA in tax policy through the Center for Tax Policy and Administration (Eccleston and Woodward Citation2014). A similarly prominent example is the role of the BIS in banking regulation. Our finding highlights a strong positive authority gap, which is in line with the literature on the role of the BIS in this thematic area (Ozgercin Citation2012). We also observe gaps, with less expression in the literature. The World Bank has quite strong de facto expert authority in tax policy, banking regulation and debt management; it only enjoys medium levels of expert authority in climate change, agribusiness, biodiversity and monetary policy. In bioenergy, the World Bank’s de facto expert authority score is quite low. Similar patterns emerge when looking at the FAO, with high de facto expert authority in climate change and biodiversity, medium authority in agribusiness and rather low authority in bioenergy. The IMF is the only IO that consistently achieves high de facto expert authority, though its monetary policy score is somewhat lower than its authority in the other three thematic fields.

In order to classify cases into positive and negative authority gaps, we now discriminate high and low levels of authority based on the mid-range value. displays the different configurations of authority we found when comparing values of IPAs by thematic fields. These comparisons reveal some gaps but also substantial alignment. Most of the IPAs are aligned in most thematic fields. However, we find that BIS in banking regulation, the OECD in tax policy and the World Bank in three thematic fields (banking regulation, debt management and tax policy) can extend their authority to create positive authority gaps. The only negative authority gap discovered on the thematic area level is the FAO in bioenergy policy. Nevertheless, the observed gaps are much greater than at the global level. The IPAs with positive authority gaps achieve similar de facto values as IPAs that have much more de jure expert authority.

Table 3. Different observed authority configurations IPA and policy level

Authority Gaps for Different Addressees

In a final step, we now examine authority gaps at the level of the addressees, the national bureaucratic units. As discussed, our survey was targeted at the most senior civil servant solely responsible in each policy area in the national ministries and central banks. plots the evaluations of these civil servants against de jure authority of the five IPAs. What becomes apparent is that all IPAs enjoy high levels of de facto expert authority with some respondents and very low levels of de facto expert authority with others. This implies that negative and positive authority gaps seem to emerge in the relationships between all IPAs and their addressees.

Figure 5. De jure expert authority and de facto expert authority distribution of addressees (labels indicate the percentage of respondents per IPA)

In order to better grasp the distribution of these gaps, we apply the mid-range benchmark to the individual evaluations. displays the configurations at the level of the bureaucratic units. The percentages add up to 100 per cent per row. Therefore, the values describe the percentage addressees over whom high (or low) de jure authority IPAs enjoy high (or low) de facto authority. Overall, conformity is still considerable. For both high and low de jure authority, roughly 60 per cent of respondents’ evaluations conform to de jure values. Nevertheless, circa 40 per cent of respondents indicate that positive or negative authority gaps exist in the individual relationships between IPAs and their addressees.

Table 4. Different observed authority configurations at the addressee level (national bureaucratic unit)

The descriptive statistics show that authority gaps materialise at different levels of analysis. At the global level, IPAs that have higher de jure expert authority also enjoy more de facto expert authority. However, when evaluating them according to the cut-off, we still see positive authority gaps for some IPAs. At the policy-area level, we find that differences in de facto expert authority conform with differences between IPAs in de jure expert authority. Nevertheless, we discover (mostly positive) authority gaps in some policy areas. When looking at the addressee level, we found that de facto expert authority conforms with de jure expert authority. However, 41.4 per cent of the cases of high de jure authority are characterised by negative authority gaps, and 40.3 per cent of the cases of low de jure authority show positive authority gaps. Therefore, the empirical picture indicates that authority gaps exist at all three levels of analysis, but they are much more pronounced when looking at the policy area and the addressee levels than when simply comparing aggregate values for different IPAs.

Conclusion

This paper explored the question of whether de jure expert authority and de facto expert authority are related empirically. In doing so, it evaluated the argument in the study of IPAs that both forms of authority might go separate ways or that they are even unrelated. To this end, existing data on de jure authority were contrasted with novel data on de facto expert authority. What lessons can we draw from this comparison?

We find that there is substantial conformity between de jure and de facto expert authority in our study but also reveal some gaps. Conformity can be observed at the global level, in policy areas and at the addressee level. IPAs with more authority de jure are also more authoritative de facto. At the same time, there are exceptions to this general tendency. We observe positive authority gaps at all three levels of analysis and negative authority gaps at the policy area and addressee level. This implies that some IPAs can extend their expert authority de facto beyond their levels of de jure authority and some IPAs lose authority with certain audiences. The observations beg the question why and how such authority gaps emerge. We aimed to demonstrate that such gaps exist but stopped short of explaining why specific gaps emerge. These questions have, to some extent, been addressed in case studies on the expert authority of IPAs. Studies suggest that positive authority gaps emerge when IPAs exploit ambiguities in their mandates, build up expertise in new policy areas, operate in complex regimes or seize temporal opportunity structures. In contrast, negative authority gaps emerge when IPAs’ work is perceived as lacking impartiality, or their performance is in question. While these studies are an important first step, more work is needed to understand under which conditions authority gaps emerge.

We demonstrated the usefulness of two concepts, de jure and de facto expert authority, that have been discussed mainly in the literature on IPAs. A substantial literature on expertise exists in the debate on national administrations (Kropp and Kuhlmann Citation2013; Christensen Citation2020). These studies have debated the role of expertise and knowledge of bureaucracies (Bendor et al. Citation1985). Recent contributions have argued that the influence of expertise can differ de facto and de jure (Strassheim and Canzler Citation2019). The concept of expert authority, and the methods used to capture it empirically, could be usefully applied to understand better how the relationships between national administrations and their addressees can make bureaucrats authoritative in some instances and why they are ignored in others.

Acknowledgments

The survey data was collected in the realm of the research project Expert Authority (DFG Research Unit “International Public Administration”) at the University of Potsdam, Germany, in 2016, see: https://www.uni-potsdam.de/en/intorg/research/expert-authority.html. We acknowledge the respective work by Hauke Feil and Jana Herold in this research project and thank them for sharing the data for the purpose of this article. We thank Martin Binder, Alexandros Tokhi and Michael Zürn for sharing their data with us. For their constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article, the authors would like to thank the editors, three anonymous reviewers, Louisa Bayerlein, Thomas Dörfler, Steffen Eckhardt, Constantin Kaplaner, Christoph Knill, Nina Kolleck, Nina Reiners, Ann-Kathrin Rothermel and Yves Steinebach. We also thank our survey respondents. Finally, we thank Benedict Bueb, Mamy Dioubaté, Serene Hanania, Luise Köcher, Sascha Riaz, Dunja Said, Antje Specht, Lily Young, and Matthias Tasser for support on the data collection and research assistance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Per-Olof Busch

Per-Olof Busch is a Senior Project Manager at adelphi, a leading independent think tank on climate, environment and development. From 2010-2020 he was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Potsdam, where he worked on international organisations, environmental governance, and policy diffusion and transfer.

Mirko Heinzel

Mirko Heinzel is a Research Associate at the Chair of International Relations at the University of Potsdam and a Research Affiliate at the Berlin Graduate School of Global and Transregional Studies. His research focuses on international organizations, specifically International Financial Institutions, and their bureaucracies.

Mathies Kempken

Mathies Kempken is a Research Associate at the Chair of International Relations at the University of Potsdam. He studies international organisations and their bureaucracies from a sociological perspective.

Andrea Liese

Andrea Liese is Professor for International Relations at the University of Potsdam. She mainly works on international organizations, international norms and international human rights policy. She is a member of the German Research Foundation group 1745 on “International Public Administration. The Emergence and Development of Administrative Patterns and their Effects on International Policymaking”.

Notes

1. International public administration (IPA) refers to the bureaucracy of an international organisation as collective entity and distinct body within an international organization (IO) that is staffed by non-elected civil servants (Knill and Bauer Citation2016). It is part of the international organization but distinct from its intergovernmental bodies. International public administration is used by the public administration literature, while scholars in international relations commonly use international bureaucracies to name the same bodies.

2. The literature on national administrations has used similar terms referring to de facto and de jure autonomy of administrations (Yesilkagit and Van Thiel Citation2008). Autonomy differs from authority. While autonomy refers to the ability to act independently, authority refers to the degree to which actors defer to the requests of the IPA. For a discussion of IPA autonomy see for example Bauer and Ege (Citation2016).

3. More information on the survey and all assessed IPAs can be found in the Appendix. The Appendix specifies the IPAs that were assessed in the survey (), the question that was put to administrative units to assess de-facto expert authority (), details on response rate (), details on work experience ( and ) seniority (), the distribution of expert authority evaluations () and the average de-facto expert authority value of all IPAs in the sample ().

4. The survey includes evaluations of 18 IPAs. Only five of them overlap with the existing data on de jure authority. Therefore, this paper focuses on these five IPAs.

5. AAPOR (Citation2016), “Standard Definitions. Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys.” American Association for Public Opinion Research, accessed 15 May 2018. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf

References

- AAPOR. 2016, Standard Definitions. Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys (Washington, DC: American Association for Public Opinion Research). Available at https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf (accessed 15 May 2018).

- Alter, K. J., Helfer, L. R., and Madsen, M. R., 2016, How context shapes the authority of international courts. Law and Contemporary Problems, 79(1), pp. 1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2574233

- Atfield, M. and Miller, G., 1984, Sources of bureaucratic influence: Expertise and agenda control. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 28(4), pp. 701–730. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002784028004006

- Barnett, M. N., 2002, Eyewitness to a Genocide: The United Nations and Rwanda (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

- Barnett, M. N. and Finnemore, M., 2004, Rules for the World. International Organizations in Global Politics (Cornell: Cornell University Press).

- Bauer, M. and Ege, J., 2016, Bureaucratic autonomy of international organizations’ secretariats. Journal of European Public Policy, Taylor & Francis, 23(7), pp. 1019–1037. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1162833

- Bauer, M., Ege, J., and Schomaker, R., 2019, The challenge of administrative internationalization: Taking stock and looking ahead. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(11), pp. 904–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2018.1522642

- Bauer, S., 2008, Bureaucratic authority and the implementation of international treaties: Evidence from two convention secretariats, in: J. Joachim, B. Reinalda, and B. Verbeek (Eds) International Organizations and Implementation: Enforcers, Managers, Authorities? (London: Routledge), pp. 62–74.

- Bayerlein, L., et al., 2020b, Singing together or apart? Comparing policy agenda dynamics within international organizations. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1813031

- Bayerlein, L., Knill, C., and Steinebach, Y., 2020a, A Matter of Style. Organizational Agency in Global Public Policy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Bendor, J., Taylor, S., and Gaalen, R. V., 1985, Bureaucratic expertise versus legislative authority: A model of deception and monitoring in budgeting. American Political Science Review, 79(4), pp. 1041–1060. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1956247

- Benz, A., Corcaci, A., and Doser, J. W., 2016, Unravelling multilevel administration. Patterns and dynamics of administrative co-ordination in European governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(7), pp. 999–1018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1162838

- Best, J., 2014, Governing Failure: Provisional Expertise and the Transformation of Global Development Finance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Broome, A. and Seabrooke, L., 2015, Shaping policy curves. Cognitive authority in transnational capacity building. Public Administration, 93(4), pp. 956–972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12179

- Busch, P. and Liese, A., 2017, The authority of international public administrations, in: M. W. Bauer, C. Knill and S. Eckhardt (Eds) International Bureaucracy. Challenges and Lessons for Public Administration Research (London, Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 97–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-94977-9_5

- Christensen, J. 2020, Expert knowledge and policymaking: A multi-disciplinary research agenda. Policy and Politics, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557320X15898190680037

- Cockfield, A. J., 2006, The rise of the OECD as informal “World Tax Organization” through national responses to E-Commerce tax challenges. Yale Journal of Law & Technology, 8(1), pp. 136–187. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/yjolt8&div=6&g_sent=1&collection=journals

- Doberstein, C., 2017, Whom do bureaucrats believe? A randomized controlled experiment testing perceptions of credibility of policy research. The Policy Studies Journal, 45(2), pp. 384–405. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12166

- Eccleston, R. and Woodward, R., 2014, Pathologies in international policy transfer: The case of the OECD tax transparency initiative. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 16(3), pp. 216–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.854446

- Ecker-Ehrhardt, M., 2012, “But the UN said so … “: International organisations as discursive authorities. Global Society, 26(4), pp. 451–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2012.710596

- Eckhard, S. and Ege, J., 2016, International bureaucracies and their influence on policy-making: A review of empirical evidence. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(7), pp. 960–978. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1162837

- Eckhard, S. and Parizek, M., 2020, Policy implementation by international organizations: A comparative analysis of strengths and weaknesses of national and international staff. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1813032

- Edwards, M. S. and Senger, S., 2015, Listening to advice: Assessing the external impact of IMF article IV consultations of the United States, 2010-2011. International Studies Perspectives, 16(3), pp. 312–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12059

- Egeberg, M. and Trondal, J., 2009, National agencies in the european administrative space: Government driven, commission driven or networked? Public Administration, 87(4), pp. 779–790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01779.x

- Friedman, R. B., 1990, On the concept of authority in political philosophy, in: J. Raz (Ed) Authority (New York: New York University Press), pp. 55–91.

- Gailmard, S. and Patty, J. W., 2007, Slackers and zealots: Civil service, policy discretion, and bureaucratic expertise. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), pp. 873–889. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00286.x

- Goritz, A. et al., 2020, International public administrations – Digital authorities in global climate governance? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice (forthcoming).

- Green, J., 2014, Rethinking Private Authority: Agents and Entrepreneurs in Global Environmental Governance (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Gutner, T. and Thompson, A., 2010, The politics of IO performance : A framework. Review of International Organizations, 5, pp. 227–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-010-9096-z

- Hanrieder, T., 2015, WHO orchestrates? Coping with competitors in global health, in: K. W. Abbott et al. (Ed.) International Organizations as Orchestrators (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 191–213.

- Hawkins, D. G. et al., 2006, Delegation and Agency in International Organizations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Heinzel, M. et al., 2020, Birds of a feather? The determinants of impartiality perceptions of the IMF and the World Bank. Review of International Political Economy, Routledge, pp. 1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1749711

- Hooghe, L. et al., 2017, Measuring International Authority: A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G., 2015, Delegation and pooling in international organizations. Review of International Organizations, 10(3), pp. 305–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-014-9194-4

- Hurd, I., 2008, Theories and tests of international authority, in: I. Hurd and B. Cronin (Eds) The UN Security Council and the Politics of International Authority (London: Routledge), pp. 23–40.

- Knill, C. and Bauer, M., 2016, Policy-making by international public administrations: Concepts, causes and consequences. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(7), pp. 949–959. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1168979

- Krisch, N., 2017, Liquid authority in global governance. International Theory, 9(2), pp. 237–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971916000269

- Kropp, S. and Kuhlmann, S., 2013, Wissen und Expertise in Politik und Verwaltung. Eine zusammenfassende Einleitung, in: S. Kropp and S. Kuhlmann (Eds) Dms – Der Moderne Staat (dms-Sonderheft(1/2013)).

- Lake, D. A., 2010, Rightful rules: Authority, order, and the foundations of global governance. International Studies Quarterly, 54(3), pp. 587–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00601.x

- Liese, A., Herold, J., Feil, H., and Busch, P., 2017., Explaining the Expert Authority of International Bureaucracies. Paper presented at the ECPR General Conference, 6-9 September, Oslo, Norway.

- Littoz-Monnet, A., 2017, Expert knowledge as a strategic resource: International bureaucrats and the shaping of bioethical standards. International Studies Quarterly, 61(3), pp. 584–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx016

- Liu, X., Stoutenborough, J., and Vedlitz, A., 2017, Bureaucratic expertise, overconfidence, and policy choice. Governance, 30(4), pp. 705–725. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12257

- Ozgercin, K., 2012, Seeing like the BIS on capital rules: Institutionalising self-regulation in global finance. New Political Economy, 17(1), pp. 97–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.569020

- Sending, O. J., 2017, Recognition and liquid authority. International Theory, 9(2), pp. 311–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971916000282

- Sharman, J. C., 2008, International organizations and the implementation of new financial regulations by blacklisting, in: J. Joachim, B. Reinalda, and B. Verbeek (Eds) International Organizations and Implementation: Enforcers, Managers, Authorities? (London: Routledge), pp. 48–61.

- Strassheim, H. and Canzler, W., 2019, New forms of policy expertise, in: D. Simon et al. (Ed.) Handbook on Science and Public Policy (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), pp. 243–266.

- Tallberg, J. et al., 2016, The performance of international organizations: A policy output approach. Journal of European Public Policy, Taylor & Francis, 23(7), pp. 1077–1096. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1162834

- Viehoff, D., 2016, Authority and expertise. Journal of Political Philosophy, 24(4), pp. 406–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12100

- Weber, M., 1980, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 5th ed. (Tübingen: Mohr).

- Woods, N., 2006, The Globalizers. The IMF, the World Bank, and Their Borrowers (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

- Yesilkagit, K. and Van Thiel, S., 2008, Political influence and bureaucratic autonomy. Public Organization Review, 8(2), pp. 137–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-008-0054-7

- Zürn, M., 2018, A Theory of Global Governance: Authority, Legitimacy, and Contestation (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Zürn, M., Tokhi, A., and Binder, M., 2020, The International Authority Database (IAD). Unpublished manuscript.

Appendix A.

IPAs included in the survey

Table A1. IPAs included in the survey in the different policy areas

Questionnaire

The questionnaire for the survey was developed in English and professionally translated into German, French and Spanish. It was pre-tested with bureaucrats active in other policy areas and working in regional administrations. Furthermore, we pre-tested the survey with academics working on public administration and political science and discussed the construct validity with this group of people. The question included the option to indicate that respondents are not aware of advice or do not know the work of the respective IPA (called secretariat in the survey). This was intended to capture only evaluations from respondents that were sure about what the IPA does. The question focusing on expert authority was asked of all respondents in the same way. The only alteration regards the name of the thematic field and the included IPAs. displays the question as it was put to administrative units active in banking regulation.

Thinking of all of the policy advice that, to your knowledge, has been provided by each of the following secretariats in banking regulation policy:

How much of this policy advice has been taken into account specifically because your unit perceives the respective secretariat to be an expert in banking regulation policy, whose policy advice can be considered without further examination?

Please give a rough estimate for the last 24 months.

Table A2. Question on expert authority in the survey

Respondents

For the survey, we sent the questionnaire to the highest-level civil servant solely responsible for each of the eight thematic fields in their national administrative unit (in the two policy areas agriculture and finance). Not all countries have a responsible administrative unit in all policy areas. Therefore, we ended up with 932 targeted high-level civil servants. In a few countries, there were multiple thematic fields that administrative units were responsible for. In these cases, respondents evaluated multiple thematic fields. If multiple administrative units were responsible, we sent the survey to all responsible administrative units. We received 362 questionnaires from 106 countries. These cover 354 different thematic area units. Consequently, our response rate is 38 per cent (). The calculation is based on the most conservative way to estimate the response rate (minimum response rate according to (AAPOR Citation2016)).Footnote5

Table A3 Response rate (based on n = 354)

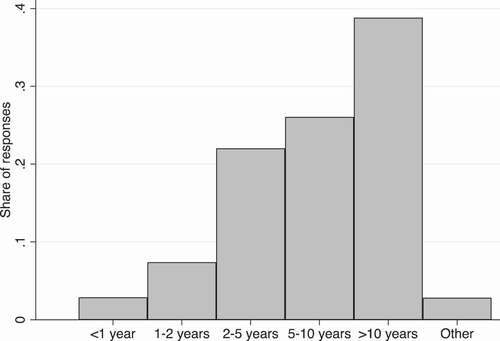

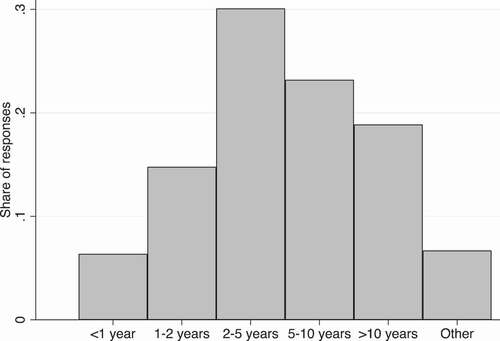

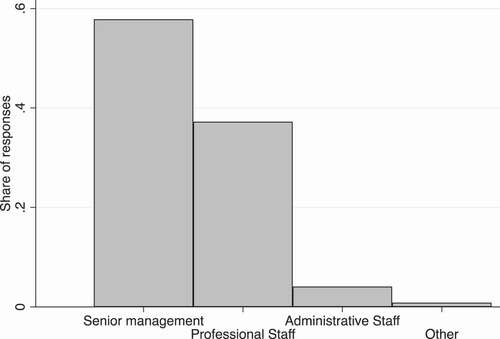

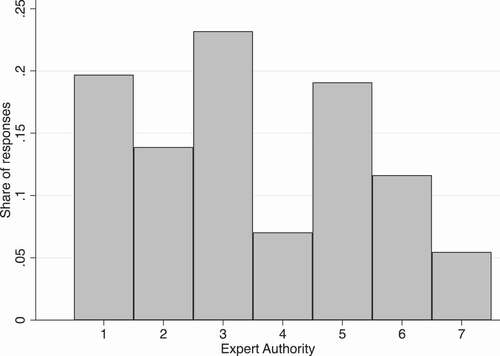

In addition, we display some descriptive statistics on the composition of our respondents (). In order to better understand who answered the survey, we asked respondents three questions on their background. The first two focus on their experience in the thematic field and in the administrative unit. displays the share of responses for the experience in the thematic field. One can see that respondents are overall quite experienced. Most have worked more than 10 years on the specific thematic field. visualises the experience in the specific national administrative unit. Most respondents have been working 2–5 years in the national administrative unit in their thematic area. visualises the respondents by staff category. One can see that most of our respondents are working as senior management in their national administrative units.

Survey Results

Finally, we give some further results on our de facto expert authority variable. In the main body of the article, we focused on the five IPAs that were covered by both our survey and the de jure data by Zürn et al. (Citation2020) and Hooghe et al. (Citation2017). Now, we use our full sample to give readers some indication of the overall distribution of de facto expert authority and where the five IPAs from the main body of the article stand compared to the IPAs that were not included. displays the distribution of respondents’ evaluations of IPAs expert authority. displays the distribution of expert authority evaluations for each IPA in each thematic area that was included in our survey. shows that in 7 out of the 8 thematic areas, the IPAs in the main body of the article are not clustered in the higher or lower end of all IPAs in our survey. The only thematic area, where we observe such clustering is tax policy. In tax policy, the IPAs in the main body of the article are at the higher end of all IPAs in the sample.