Abstract

This article investigates the nuanced and disaggregated role of state and civil society in the fight against COVID-19 in Hong Kong and Singapore through a comparative policy study. Hong Kong and Singapore provide two contrasting cases of state-society interaction under the framework of Political Nexus Triads (PNT). Hong Kong combats COVID-19 with greater dependence on its civil society and bureaucrats, while Singapore relies more on a state-centred approach. They represent the diversity of state-society relations and multiple configurational causality in the COVID-19 responses and question the efficacy of any single and contextless model.

1. Introduction

Taking a state-society relations perspective, this article examines the nuanced and disaggregated role of state and civil society in the COVID-19 responses through a comparative policy study of Hong Kong and Singapore under the analytical lens of Political Nexus Triads (PNT). Since COVID-19 has developed into a global pandemic, there has been an active search for transferable policy lessons to combat it. As experiences of both successful and less successful countries become more visible and available, they provide a valuable natural experiment for finding out the capacity and incapacity across governments by analyzing variations in their responses (Capano et al. Citation2020).

In the COVID Resilience Ranking by Bloomberg,Footnote1 which ranks the performance of the largest 53 economies on their success at containing the virus with the least amount of social and economic disruption, Hong Kong and Singapore ranked amongst the top ten in January 2021. They successfully outperformed many advanced countries in the West, including Canada (ranked 13th), France (ranked 19th), the U.K. (ranked 32nd), the U.S. (ranked 35th) and Germany (ranked 36th). The research puzzle, this article would like to address, is how such a remarkable COVID-19 containment performance can be accomplished, given their different contexts of state-society relations. In this regard, this article has a twofold objective. First, it would like to examine the policy responses of Hong Kong and Singapore, the two city-states in East Asia, and to compare their COVID-19 approaches. Second and more importantly, it would like to take advantage of the opportunity of a natural experiment to study how dissimilar cases of state-society relations affect their approaches to responding to COVID-19.

It is argued that similar COVID-19 outcomes have been achieved by two completely different approaches. Rather than representing a standardised, one-size-fits-all approach, Hong Kong and Singapore have adopted contrasting but contextually appropriate models for handling the pandemic. Although Hong Kong and Singapore share many similarities in regard to the legacy of their British colonial administrative systems and development trajectories (Perry et al. Citation1997; Weiss and Hobson Citation1995; Woo-Cumings Citation1999; Woo Citation2018), they have taken different approaches to tackling COVID-19, with the former taking a more society-oriented approach and the latter adopting a more government-centred approach.

This study adopts the analytical lens of Political Nexus Triads (PNT) (Moon and Ingraham Citation1998) from the perspective of state-society relations. PNT identifies three main actors (and their respective institutions) of policy-shaping power in state-society interaction: politicians (politics), bureaucrats (bureaucracy), and citizens (civil society). In reference to the principle of multiple configurational causality (Fischer and Maggetti Citation2017), our study tests the possibility of multiple approaches of responses to tackling COVID-19 under two contrasting cases of state-society relations. It also echoes the call in the state-society relation literature (Evans Citation1997a, Citation1997b; Sellers Citation2011) to advance its research by going beyond the outdated state-society dichotomy. This study aims to take a more nuanced approach to disaggregate state and society by identifying the interactions among different actors on shaping policies under diverse contexts of state-society configurations.

A comparative case analysis between Hong Kong and Singapore in their COVID-19 responses is implemented. Among other major indicators, health outcomes including the number of COVID-19 cases are the major performance indicators in the comparison. It uses multiple data sources, including media reports, government archives, and websites, international datasets, such as Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) by Oxford University and data from the World Health Organization (WHO). The study compares the nature of state-society relations between Hong Kong and Singapore, identifies the major state and societal actors and their role and impact in formulating and delivering the COVID-19 performance, and highlights the critical and defining events characterising the different paths taken by the two city-states under their distinctive state-society contexts.

2. The Analytical Framework: Political Nexus Triads (PNT) under State-Society Relations

Policy responses are made by institutions either independently or collectively as compromises and interactions among them and therefore are institutional responses (Wong and Welch Citation1998; Fukuyama Citation2013; Van de Walle and Brans Citation2018). Following this logic, this study asks the fundamental question of which actors and institutions under a state-society relations framework could step up for mobilising, formulating, and producing the appropriate and necessary policy responses to fight a major crisis. In identifying the major actors, it adopts the analytical lens of Policy Nexus Triads (PNT) (Moon and Ingraham Citation1998) as a general framework to guide the analysis in the comparative case study.

In PNT, any government action, including policy, can be understood as a product of state-society interactions among three distinct sets of state and societal actors: politicians, bureaucrats, and civil society (Moon and Ingraham Citation1998). Although PNT was originally developed to study the dynamic trajectory in Asian administrative reforms, it is an embracive framework with broad explanatory power as it pinpoints the macro institutions of governance, outlines their major characteristics, and lays out their interactions. As a dynamic model, under PNT, each institution has its own rationale to communicate with one another and attempt to increase its influence.

PNT is “an extended model which adds civil society as the third dimension to the traditional politics-administration model” (Moon and Ingraham Citation1998, p. 77) in which politicians and bureaucrats traditionally serve the functions of the state. According to Aberbach et al. (Citation1981), bureaucrats, as administrative elite and career civil servants who build their legitimacy to govern on expertise and professionalism, and politicians, who are given the power to govern through democracy and elections, are the powerful actors sharing the policymaking task with overlapping roles and images. They represent the two major forces of politicization, often in the form of democratization and bureaucratization, which shape politics and governance in many countries (Peters and Pierre Citation2004).

Civil society refers to “the non-government social forces other than politicians and bureaucrats in a society” (Kim and Moon Citation2003, p. 552). It is a useful but also broad concept so that its definite meaning is still evolving and being contested in social science (Edwards Citation2014). But in general, it is conceptualised as “the sum of institutions, organizations, and individuals located between the family, the state, and the market, in which people associate voluntarily to advance common interests” (Anheier Citation2004, p. 20). Schwartz (Citation2003, p. 23) describes civil society as “the sphere intermediate between family and the state in which social actors pursue neither profit within the market nor power within the state.” It is taken as “the self-organisation of society through the creation of autonomous, voluntary, nongovernmental organisations such as economic enterprises, religious and cultural organisations, occupational and professional associations, independent news media and political organisations” (Kim and Moon Citation2003, p. 552). With the inclusion of civil society, PNT has become not only an extension of a traditional “politics–administration nexus” (Kim and Moon Citation2003, p. 552) but also a comprehensive framework to study the three major policy institutions and their interactions.

The connection between PNT and the state-society relations literature should also be highlighted. PNT represents an effort to advance the frontier of theory and knowledge in state-society relations by transcending the outdated and unrealistic approaches of state-society dichotomy, which is increasingly incapable of capturing the changes and dynamics in state-society interactions (Sellers Citation2011). In the early studies of state-society relations, the main theories were dominated by the following premises and assumptions: state and society are taken as conflicting in nature – two gigantic, incompatible and antagonistic forces competing for social control (Migdal Citation1988). Not surprisingly, in such a state-society divide, a “strong state” is critical for a strong policy capacity while a “strong society” is interpreted as dysfunctional to modernisation, economic development, and nation-building (Migdal Citation2001). State, portraited as an authoritarian, hierarchical and unmalleable public institution, is broadly perceived as the only means of effective collective action (Haggard Citation1990). Besides, state and society are taken as unitary actors under which there are no sub-actors or constituting units (Evans Citation1995; Skocpol Citation2004).

While the traditional approach was useful in the past for analysing state-building in a developmental context, it has “proven increasingly inadequate to capture the realities of state–society relations” of the contemporary era (Putnam Citation1993; Sabatier Citation1988; Sellers Citation2011, p. 124). Evans (Citation1997b) points to the synergies between state and society as the crucial element for understanding state–society relations. Ostrom (Citation1997) further stresses the ability of state and societal actors to achieve co-production under the principles of complementarity and embeddedness to fully realize the synergy. Crucially, the shift towards “governance as a guiding approach to policy prescription and a focus of analysis has left the state-society dichotomy of increasingly limited utility for understanding state–society relations” (Pierson Citation1994; Fung Citation2004; Sellers Citation2011, p. 137). The paradigm of governance without government (Peters and Pierre Citation1998) underlines the importance and diversity of multiple policy actors not confined by the traditional public-private or state-society divides. Knowledge and awareness of “the exercise of societal actors as interplay and interdependence between state and society” (Sellers Citation2011, p. 135) becomes increasingly common and ineluctable (Pierson Citation1993; Ostrom Citation1997). All these new developments point to the limitation of the traditional paradigm of state-society dichotomy which fails to realize many important actors and forces.

Interactions among the policy actors can be further understood through their policy capacity (Wu, Ramesh, & Howlett Citation2015), and “the set of skills and resources or competencies and capabilities necessary to perform policy functions” at the analytical, operational and political levels (Wu, Ramesh, & Howlett Citation2015, p.166). The capacities of the three main PNT actors are summarised in in which examples of their actions in their interaction are also provided. Policy capacities contribute to the overall governing capacity though there can be tensions among different domains, which should be carefully negotiated (Gleeson et al. Citation2011)

Table 1. PNT actors and policy capacity: political support, analysis and actions

The challenge for the advancement of state-society relations research is to devise new and refined reformulations and more complex conceptualisations that can capture the diversity of actors and their dynamics in state-society interactions (Sellers Citation2011). In this study, PNT can help to push for its progress in the following areas. First, it has disaggregated the state into two major categories of actors, i.e., politicians and bureaucrats, and captured “the societal and state actors in joint processes of governance” (Sellers Citation2011, p. 135). Second, as new research acknowledges that effective governance is often “not the product of a state that achieved autonomy from civil society”, our analysis will “place the burden of explanation on factors beyond the state itself or the state–society divide” (Sellers Citation2011, p. 129) and consider how actors in civil society can mobilise state authority. Third, it embraces a more open and nuanced position towards state-society relations, embracing possibilities of both synergies and conflicts under different configurations of state-society relations with variations in stateness and state tradition.

3. Comparing the Two City-States

While Hong Kong and Singapore are similar in many major aspects, such as its British colonial history and socio-economic context, including having Chinese as the ethnicity of most of their populations, they are also different in some key variables of public policy. Their early economic miracle is often explained by the theoretical model of developmental state, which uses an elite Weberian bureaucracy as the driver of economic growth (Johnson Citation1982; Douglass Citation1994; Huff Citation1995). But in recent decades, they have embarked on a divergent path of administrative and policy reforms, such as the New Public Management (NPM) reform (Lee and Haque Citation2006; Cheung Citation2008; Woo Citation2018).

3.1. State-Society Relations

Hong Kong and Singapore have different sets of state-society configurations. Under PNT, Singapore exhibits much higher integration and congruence among politics, bureaucracy, and civil society under its strong political leadership. In contrast, in Hong Kong, growing tensions and intense conflicts exist between a weak state dominated by undemocratically-elected politicians, mainly among the Chief Executive and her political appointees, its bureaucracy and civil society.

Strong, weak and fragile states are major concepts commonly used in the literature of political economy and comparative politics (Skocpol & Finegold Citation1982; Migdal Citation1988, Citation2001; Hendrix Citation2010). They refer to the level of state capacity in fulfilling some core state responsibilities, such as the coercive, administrative, and extractive functions to provide law and order and major services to citizens (Ham Citation2018). Democracy and legitimacy are found by state capacity research to be the major enabling factors of a strong state (Hilderbrand and Grindle Citation1997; Back and Hadenius Citation2008). Similarly, the concept of civil society and its strength can also be operationalized and measured (Anheier Citation2004) from which many indicators and indexes of civil society have been developed accordingly (Heinrich Citation2010). For example, CIVICUS uses the framework of “civil society diamond” to evaluate civil society by the four dimensions of structure, environment, values, and impact to classify civil society of countries around the world into five categories: open, narrowed, obstructed, repressed, and closed (Chan Citation2012).

compares the state-society relations in Hong Kong and Singapore. Constitutionally, Hong Kong is an executive-led government, but there is a wide gap between the formal power of politicians and the reality as it has faced a huge and looming legitimacy crisis since the return of its sovereignty from the UK to China in 1997 (Lee Citation1999; Scott Citation2000; Ma Citation2007; Hartley & Darry Citation2020). With regard to its meritocratic and autonomous Weberian bureaucracy, its power and influence have also been considerably undercut by the politicians through a continuous process of politicization (Wong Citation2013). Citizens have enjoyed a high level of freedom fostering an active and autonomous civil society even in its colonial era (Fong Citation2013). A lot of tussles have occurred among the central government, the Hong Kong SAR government and lawmakers in Hong Kong as civil society faces more confrontations with the state in social movements in the last decade (Lee and Chan Citation2018).

Table 2. Key institutions under PNT in Hong Kong and Singapore: politics, bureaucracy and civil society

While the state-society relations are unstable and adversarial in Hong Kong, Singapore has supportive and integrative state-society relations (Cheung Citation2008; Haque Citation2009). Although the People’s Action Party (PAP), its governing party, is increasingly challenged by a growing civil society with the rise of youth activism and social media (Tan Citation2018), the integration between state and society remains strong under the reliable partnership between politicians and bureaucrats. The Singapore government continues to adopt a pragmatic approach to governing though it is constantly pushed by different societal and political forces to introduce reforms gradually over time (Tan Citation2012). Its civil society is still mainly allowed to be active in some non-political and non-sensitive policy areas (Rodan Citation2003; Ortmann Citation2015).

3.2. Policy Responses: State vs. Society

Both Hong Kong and Singapore encountered the first confirmed COVID-19 case on 23 January 2020. Although the number of cases in Singapore was higher than Hong Kong, close to 90% of the cases in Singapore were migrant workers living in dormitories in unsatisfactory hygiene conditions and separated from the general community (Koh Citation2020). To measure policy responses of governments around the world in regard to tackling COVID-19, Oxford University created the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) dataset (Hale et al. Citation2020). shows the data of Hong Kong and Singapore in the major items of OxCGRT and the Stringency Index.

Table 3. Policy responses: stringency and public health measures in Hong Kong and Singapore in 2020

One major difference which stands out is that Hong Kong, unlike Singapore and many other countries or regions, reached its policy outcome without a state-led large-scale lockdown. For Singapore, it had a major lockdown called Circuit Breaker in April and May of 2020. Another major discrepancy is the use of technology for contact tracing in combating COVID-19. Singapore has employed mobile apps such as TraceTogether and SafeEntry, for contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wu and Zhu Citation2020). Although Hong Kong launched its contact tracing app “LeaveHomeSafe”, because of the distrust of politicians, its utilisation by citizens was much lower than the adoption rate in Singapore.Footnote2

The level of Stringency Index is higher for Singapore than Hong Kong. Out of 100, the highest index recorded for Hong Kong is only 71 but is 85 for Singapore. This is difficult to interpret unless one accepts the conclusion that fewer actions are better. As the index captures mostly government actions, not voluntary collective actions by civil society, this adds more weight to the argument that Hong Kong’s performance in COVID-19 can be attributed much more to its civil society.

Under the paradigms of state-society synergy (Evans Citation1997b), co-production (Howlett et al. Citation2017), and collaborative governance (Emerson et al. Citation2012), it is becoming more common and crucial for citizens to be involved in producing policy outcomes. In Hong Kong, long before warnings were issued by officials and laws and regulations were passed, citizens had already taken many measures voluntarily including wearing masks, maintaining social distancing and personal hygiene, which could be as simple as washing one’s hands regularly to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The business sector has also played a role in the crisis in both Singapore and Hong Kong including ensuring the abundant and continuous supply of daily necessities in stores to avoid panic shopping. These societal actors which include corporations and the mass media can be taken as part of civil society as long as their actions are civic-based, not profit-motivated.

4. State-Society Relations and Approaches of COVID-19 ResponsesFootnote3

4.1. Hong Kong: Society-Centred Bottom-Up Approach

According to the state-society relations framework by Sellers (Citation2011), the COVID-19 responses in Hong Kong can be classified as a “society-centered bottom-up approach”. The partnership between bureaucracy and civil society led to strong accountability and freedom of information. One of the best examples was the daily press conference hosted by the Centre for Health Protection of the Department of Health, which was widely regarded by citizens and the mass media as an objective, authoritative, and reliable source of information about COVID-19. Advice given by well-respected medical scholars in the public media, which regularly challenges and questions the judgment of politicians, is also a highly credible source of information for citizens.

The provision of accurate and timely information by a professional bureaucracy to the public is widely regarded as one of the effective and essential solutions to combat pandemics (Moon Citation2020). In a pandemic, “speaking truth to citizens” is no less important than “speaking truth to power.” Valuable information can be utilised by medical professionals to formulate the appropriate treatment for the disease and contain its spread, while citizens take necessary preventive measures, which can be as simple as wearing a surgical mask and maintaining social distancing. In addition, online forums in social media are one of the major channels for organizing collective action against COVID-19. Using these online forums, many health professionals working in public hospitals also share the latest insider information about the situation of the pandemic and help citizens understand and analyse medical information from different sources, including official and policy messages by the politicians, on their accuracy, usefulness and reliability.Footnote4

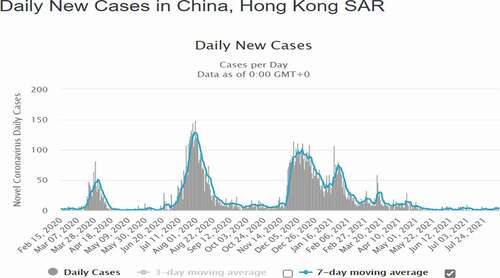

shows the daily number and the overall trend and longitudinal pattern of COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong. At the time of writing, there have been a total of four waves of COVID-19 outbreak. The ups and downs in the curve can be viewed as the tug of war between the politicians and the alliance of civil society and professional bureaucrats. COVID-19 cases were more under control when the latter were taking the lead but performance is deteriorating as politicians would like to dominate and suppress the societal actors (Wong Citation2021).

The first wave was from late January to early March 2020 in which Hong Kong was successful in preventing the outbreak as the number of total cases was kept at around 120 only. Border closure plus an effective quarantine policy are proven effective measures worldwide to prevent the spread of the pandemic, and Hong Kong is no exception. This was mainly attributed to the pressure of civil society and the professional bureaucrats, mostly medical workers, in relation to which a huge 5-day strike was launched by a union of medical workers. The strike, together with strong pressure from the public, forced the government to act and close some border crossings with mainland China on 5 February.Footnote5 The second wave was from mid-March to late June, in which cases rose to over 1,000. Despite that, society and most citizens were not affected by it since most of those cases were not community outbreaks but imported cases of Hong Kong citizens returning home from overseas.

What has been worrisome is the third and fourth waves starting in early July and mid-November 2020, respectively. In the third wave, the number of cases increased sharply within a short period and reached over 4,000. In the fourth wave, the number had jumped from about 5,500 to over 6,800 in just two weeks. Quarantine loopholes, including lenient and scientifically unjustifiable exemptions, related to the misjudgment and incompetence of unaccountable politicians, was regarded by both citizens and experts as the root cause of these two waves.Footnote6 For example, in the third wave, the government loosened the control over vessel and flight crews in early June to allow them to enter Hong Kong without medical proof and quarantine requirements.Footnote7 In the fourth wave, loopholes such as allowing people under quarantine in hotels to receive visitors were revealed.Footnote8 Although this triggered a huge public outcry, civil society was weak in checking against the state in the third and fourth waves. After the second wave, the government launched many new policies and initiatives to weaken civil society and bureaucracy.

July 1 is the major turning point in the power shift in Hong Kong since the national security law was passed in May 2020 (Davis Citation2020). The accountability of the politicians to civil society during the pandemic was significantly reduced when the legislative election scheduled in September 2020 was cancelled by citing the control of the pandemic as a justification. For bureaucrats, their autonomy and professionalism were also undermined and threatened through various reforms and structural changes. Around the world, an intact civil service system always plays a leading role in determining the ability of civil servants to defend public interests (Peters and Pierre Citation2004). But it is gradually replaced by political accountability under the politicization of the civil service that emphasizes obedience to the government of the day (Romzek and Dubnick Citation1987). Since January 2021, all civil servants in Hong Kong are required to take an oath to ensure their political loyalty to the politicians in that open dissent and opposition to the government would no longer be tolerated. The weakened civil society and constrained bureaucracy explain why Hong Kong has fewer tools and resources at its disposal to prevent the fourth wave.

4.2. Singapore: State-Centred Top-Down Approach

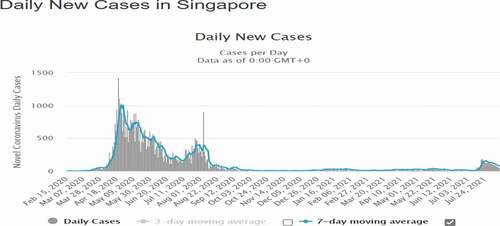

Singapore has been viewed as one of the countries that has got its COVID-19 responses largely right, but unlike Hong Kong’s society-driven response, Singapore’s precautions are mostly driven by the government. It has adopted a “state-centred top-down approach” under the state-society relations framework of Sellers (Citation2011). shows the overall trend and longitudinal pattern of COVID-19 cases in Singapore. It reveals a scenario that is very different from Hong Kong in the sense that it is a relatively smooth and normal curve, with fewer irregularities, ups, and downs. This reflects a typical case of state-centred approach in which it usually takes some time for the state apparatus to comprehend the crisis and mobilise its resources and capacities. After that, the state becomes an efficient machinery to control and eradicate the problem, leading to the sharp fall in cases after its peak in April 2020.

The peak passed after Singapore adopted the Circuit Breaker lockdown in April and May. The majority of daily cases were confined to be the migrant workers group. In early January 2020, the Ministry of Health (MOH) alerted all medical practitioners to look out for suspected cases of pneumonia in people who had recently returned from Wuhan and implemented temperature screening at Changi Airport for inbound travellers arriving on flights from Wuhan. The country also promptly enacted contact tracing for all confirmed cases.

Another key feature of Singapore’s response is the government’s efforts in overcoming the “fear factor” in society through timely communications (Quah Citation2020; Wong and Jensen Citation2020; Woo Citation2021). Individuals are uncertainty-averse; when the DORSCONFootnote9 turned Orange, some Singaporeans over-reacted and started panic-buying. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong calmed the nation with an open address to explain the government’s strategy in three different languages. In mid-February, Minister for Health Mr Gan Kim Yong and Minister for Culture, Community & Youth Ms Grace Fu met with church leaders to update them on the COVID-19 situation, and to provide guidance on precautionary measures that churches can take to reduce the risk of transmission of the virus.Footnote10 Besides, the Singapore government strictly enforced laws and restrictions to ensure that all travellers and citizens follow the quarantine order to contain the first wave of the outbreak. In addition, the Singaporean government also put in place measures to detect the spread of false news with the Infectious Diseases Act for False Information and Obstruction of Contact Tracing.Footnote11

With its “all-of-government approach,” Singapore was able to maintain a sense of normalcy and at the same time contain the outbreak of the virus. However, the number of daily cases has increased quickly since April and massive outbreaks happened among foreign worker dormitories. In late March, the authority started advising citizens to keep a safe distance in public places. On 7 April, Singapore’s Multi-Ministry Taskforce (MTF) implemented an elevated set of safe distancing measures, described as a “circuit breaker” (de facto lockdown), to pre-empt the trend of increasing local transmission of COVID-19.

The wearing of masks is an interesting example that highlights the differences in state-society relations between Hong Kong and Singapore. For Hong Kong, with little trust in the government and the strong memory of the SARS experience, citizens ignored government advice or comments to wear masks by themselves right from the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak. But there was a learning process led by the government in Singapore. At the very beginning, the Singaporean government advised citizens “not to wear a mask if you are well”, following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) advice. The authority emphasised that masks were not necessary when people practise good personal hygiene and wash their hands regularly.Footnote12 However, in early April, in view of the intractable cases, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that his government would advise the general public to wear masks for avoiding contracting the virus. The government distributed reusable masks from 5 April to all residents. On 14 April, the government tightened up the Circuit Breaker measures and required all to wear a mask in public.Footnote13

Apart from the nationwide lockdown in April, another good illustration of the state-centred top-down approach is the “Reopening of Singapore” project by three phases: Phase One (Safe Re-opening), Phase Two (Safe Transition) and Phase Three (Safe Nation). The state monitors the progress of each phase to decide when it is appropriate to proceed to the next phase. Singapore started its phase three of reopening in late December 2020, and due to the spread of the Delta variant, Singapore returned to Phase Two (Heightened Alert) on 22 July 2021.

The state-led integrative model in Singapore also has its weaknesses and blind spots. The large outbreak of COVID-19 cases among migrant workers was a signal about the weak position of civil society (Woo Citation2020). The sharp increase in COVID-19 cases among the foreign worker population revealed Singapore’s “two very different realities”.Footnote14 Although groups and associations in civil society have raised the issue of the poor living conditions of migrant workers, this was not taken seriously by the politicians and bureaucrats due to the weak and constrained influence of civil society in influencing policy directions in major areas (Tan Citation2018), making the issue difficult to reach the formal policy agenda before the COVID-19 crisis. Despite that, the state-centred approach has been proved to be quite efficient and effective; once the state machinery is mobilised, the problem can be rapidly contained. For example, many dormitories of migrant workers, which were believed to be the source of the outbreak, were immediately declared isolation areas with massive numbers of migrant workers being put in quarantine.Footnote15 In Singapore, civil society is still regarded more as an actor cooperating with the state rather than a co-decision maker or partner formulating key policy responses. But it should be noted that in recent years, the importance of civil society has been recognised by the government and opinion leaders in Singapore.

5. Implications for Policy and Research

In response to cutting-edge debates on state-society relations, this article examines the disaggregated and nuanced role of state and civil society in the fight against COVID-19 through a comparative study of Hong Kong and Singapore. By investigating the policy responses of Hong Kong and Singapore, this article compares their COVID-19 policies to find out how these contrasting cases of state-society relations affect their approaches to responding to COVID-19. Although both of them have had impressive COVID-19 performances, different paths and models have been adopted. Due to their different state-society configurations, a more society-centred approach has been adopted in Hong Kong while a more state-centred approach has been employed in Singapore.

The analysis provides implications for both research and policy. In terms of research, it has enriched the theoretical discussion of state-society relations by addressing two of its five future patterns of research: state-societal configurations in the process of governance; and policy outcomes and state-society feedback (Sellers Citation2011). They together reflect the static and dynamic views of nuanced and disaggregated state-society relations. In the former, the analysis in this study has shown how state-society configurations affect the policy approaches adopted, showing what would work and what does not work under a particular state-society context. For the latter, by tracking the state-society interactions, including the conflicts in Hong Kong and their synergy in Singapore, it has shown the dynamics and variations in the interplay between state and societal actors and how they influence policy outcomes and performance.

Furthermore, the experiences of these two city-states support the usefulness of multiple configuration causality in comparative policy analysis. Multiple configurational causality allows us to unpack and diagnose some complex observations often encountered in comparative policy analysis by pinpointing that a policy outcome can be caused by multiple factors, which may have different effects, including opposite ones, on it (multifinality) and the same outcome can be caused by different combinations of those factors (equifinality) (Fischer and Maggetti Citation2017). In comparative policy analysis, we should avoid the trap of oversimplification and over-generalisation to assume the existence of a single solution or the most superior model.

In the spirit of cross-fertilization of knowledge discovery through interdisciplinary research, in further enhancing comparative policy research, this study is to recognize the potential of multiple configurational causality as a theoretical and methodological lens for examining how different configurations of factors can lead to a policy outcome. Its use would immensely increase the ability of researchers to cut across contexts when comparing cases of different countries (Brans and Pattyn Citation2017), improve the level of external validity (Radin and Weimer Citation2018) and therefore the ability to integrate research and practice by drawing actionable lessons for policy transfer. At the same time, since the findings in this study are built on a comparative case study of two city-states, more studies of a larger number of cases would be recommended to enhance their validity and reliability.

In terms of policy contribution, these two cases show that all three key actors under PNT – politics, bureaucracy, and civil society, are capable of making policy responses for the purpose of addressing a crisis as severe as COVID-19. A broader and more inclusive definition of what constitutes a policy response to COVID-19 is therefore required. A policy response should not be confined to only the action by the state but should also include members of civil society. The overall effect of a policy response should be taken as the sum of all actions and reactions, which can be conflicts or synergy, cooperative or confrontational, thereby enriching the views of studies in state-society relations (Evans et al. Citation1985; Migdal Citation1988) and recognizing the state-in-society approach of their co-transformation and co-constitution (Migdal Citation2001).

Singapore is a case of cooperative state-society relations and Hong Kong belongs to the confrontational category. Different state-society relations reaching the same or similar outcomes dismisses any ethnocentric and parochial approaches by raising the possibility of multiple models of equivalent competence. Policymakers and citizens can vastly expand their policy toolkit by understanding state-society interactions and dynamics. This will also help to expand the scope of the practice and research of crisis policymaking in which the state is still treated as the dominant actor (Boin Citation2009; Ney Citation2012; Liu and Geva-May Citation2021). The role and influence of professionals and experts, who do not necessarily fall into the traditional categories under state-society and public-private divides, in leading policy changes under crisis should not be overlooked (Nohrstedt Citation2008; Béland Citation2016; Li and Wong Citation2019).

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Linda Li, Yee Lok Wong, Ching Ka Tsang, and Ki Chun Ng for their helpful inputs on earlier versions of this paper. The authors also benefited from helpful comments from the editors and the anonymous referees.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wilson Wong

Wilson Wong is the Director and Associate Professor of the Data Science and Policy Studies Programme, and Associate Director of the Center for Youth Studies, Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He had served as a visiting fellow of the Brookings Institution, an adjunct faculty member of Syracuse University, and a visiting scholar of Harvard University. His research areas include data science and governance, e-governance and ICT, science and technology policy, public management, and comparative public policy.

Alfred M. Wu

Wu Alfred Muluan is Associate Professor and Assistant Dean in Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at National University of Singapore. He is a development studies expert with publications in public finance, education, social protection, urban development, and local governance in China and East Asia. He previously held various positions at The Education University of Hong Kong, City University of Hong Kong, and Georgia State University. He was a senior journalist in China before he became an academic.

Notes

1. The COVID Resilience Score and its ranking are developed by Bloomberg based on 11 key metrices which are classified evenly into the two categories of “COVID Status” (1-month cases per 100,000, 1-month fatality rate, total deaths per 1 million, positive test rate, access to vaccines, doses given per 100) and Quality of Life” (lockdown severity, community mobility, 2021 GDP growth forecast, universal health care coverage, human development index). The ranking we referred to was released in January 2021. See https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-resilience-ranking/ for more information.

2. In Singapore, more than 90 per cent of the population uses TraceTogether. In Hong Kong, due to low trust in the government and concerns of privacy, the LeaveHomeSafe contact tracing app is only being used by about 20% of its citizens. Hence, instead of information and communication technology (ICT), Hong Kong mostly relies on actual tracing, the voluntary cooperation of citizens in revealing their contact traces, to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

3. For more details of the events and timeline of the COVID-19 crisis in Hong Kong and Singapore, please refer to Hartley and Darryl (Citation2020) and Woo (Citation2020) and websites such as: Hong Kong: www.otandp.co/covid-19-timeline; https://www.news.gov.hk/eng/categories/covid19/index.html;Singapore: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/six-months-of-covid-19-in-Singapore-a-timeline; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ij4gneB3V0o; https://www.asiaone.com/singapore/1-year-covid-19-singapore-timeline-milestones

4. Please refer to: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2020/05/how-hong-kong-beating-coronavirus/611524/

6. For the views of medical researchers and experts on how quarantine loopholes in Hong Kong led to the third and fourth waves, please refer to: https://fightcovid19.hku.hk/flaws-in-the-system-behind-hong-kongs-third-wave/; https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3110092/hong-kongs-latest-run-local-covid-19-cases-blamed

9. DORSCON refers to “Disease Outbreak Response System Condition” (a colour-coded framework showing the current disease situation). https://www.gov.sg/article/what-do-the-different-dorscon-levels-mean

12. https://www.gov.sg/article/covid-19-resources (Advisory on Wearing Masks – 5 Feb 2020; Practise Good Personal Hygiene (updated) – 12 Feb 2020).

15. One may refer to the BBC report “COVID-19 Singapore: A ‘Pandemic of Inequality’ Exposed” (Sept 17, 2020) for more details (www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-54082861).

References

- Aberbach, J., Putnam, R. and Rockman, B., 1981, Bureaucrats and Politicians in Western Democracies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

- Anheier, H. K., 2004, Civil Society: Measurement, Evaluation, Policy (U.K.: Earthscan)

- Back, H. and Hadenius, A., 2008, Democracy and state capacity: Exploring a J-shaped relationship. Governance, 21(1), 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00383.x

- Béland, D., 2016, Kingdon reconsidered: Ideas, interests and institutions in comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 18(3), 228–242

- Boin, A., 2009, The new world of crises and crisis management: Implications for policymaking and research. Review of Policy Research, 26(4), 367–377. doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.2009.00389.x

- Brans, M. and Pattyn, V., 2017, Validating methods for comparing public policy: Perspectives from academics and “pracademics”. Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 19(4), 303–312

- Capano, G., Howlett, M., Darryl, S. L. J., Ramesh, M., and Goyal, N., 2020, Mobilizing policy (in)capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in state responses. Policy and Society, 39(3), 285–308. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1787628

- Chan, E. Y. M., 2012, Civil society, in: W. Lam, P. L. Lui, and W. Wong (Eds) Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics (H.K.: Hong Kong University Press), 179–198

- Cheung, A. B. L., 2008, The story of two administrative states: State capacity in Hong Kong and Singapore. The Pacific Review, 21(2), 121–145. doi:10.1080/09512740801990188

- Davis, M., 2020, Making Hong Kong China (NY: Columbia University Press)

- Douglass, M., 1994, The ‘developmental state’ and the newly industrialised economies of Asia. Environment & Planning A, 26(4), 543–566. doi:10.1068/a260543

- Edwards, M., 2014, Civil Society (U.K.: Polity)

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., and Balogh, S., 2012, An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Evans, P. B., 1995, Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation (NJ: Princeton University Press)

- Evans, P. B., 1997a, The eclipse of the state? Reflections on stateness in an era of globalisation. World Politics, 50(1), 62–87. doi:10.1017/S0043887100014726

- Evans, P. B., 1997b, Government action, social capital, and development: Reviewing the evidence of synergy, in: P. B. Evans (Ed.) State-Society Synergy: Government and Social Capital in Development (Berkeley: University of Berkeley Press), 178–210

- Evans, P. B., Rueschemeyer, D. and Skocpol, T. (Eds), 1985, Bringing the State Back In (New York: Cambridge University Press)

- Fischer, M. and Maggetti, M., 2017, Qualitative comparative analysis and the study of policy processes. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 19(4), 345–361

- Fong, B., 2013, State-Society conflicts under Hong Kong’s hybrid regime: Governing coalition building and civil society challenges. Asian Survey, 53(5), 854–882. doi:10.1525/as.2013.53.5.854

- Fukuyama, F., 2013, What is governance? Governance, 26(3), 347–368. doi:10.1111/gove.12035

- Fung, A., 2004, Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy (NJ: Princeton University Press)

- Gleeson, D., Legge, D., O’Neill, D. and Pfeffer, M., 2011, Negotiating tensions in developing organizational policy capacity: Comparative lessons to be drawn. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 13(3), 237–263

- Haggard, S., 1990, Pathway from the Periphery: The Politics of Growth in the Newly Industrializing Countries (NY: Cornell University Press)

- Hale, T., Angrist, N., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T. and Webster, S., 2020, Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper, Oxford University. Available at www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker

- Ham, C., 2018, Strong states, weak elections? How state capacity in authoritarian regimes conditions the democratizing power of elections. International Political Science Review, 39(1), 49–66. doi:10.1177/0192512117697544

- Haque, M. S., 2009, Public administration and public governance in Singapore, in: P. S. Kim (Ed.) Public Administration and Public Governance in ASEAN and Korea (Seoul: Daeyong Moonhwasa Publishing Company), 246–271

- Hartley, K. and Darryl, J., 2020, Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society, 39(3), 403–423. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791

- Heinrich, V. F., 2010, Civil society indicators and indexes, in: H. K. Anheier and S. Toepler (Eds) International Encyclopedia of Civil Society (NY: Springer), 376–380

- Hendrix, C. S., 2010, Measuring state capacity: Theoretical and empirical implications for the study of civil conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 47(3), 273–285. doi:10.1177/0022343310361838

- Hilderbrand, M. E. and Grindle, M. S., 1997, Building sustainable capacity in the public sector, in: M. S. Grindle (Ed.) Getting Good Government (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 34–55

- Howlett, M., Kekez, A., and Poocharoen, O., 2017, Understanding co-production as a policy tool: Integrating new public governance and comparative policy theory. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 19(5), 487–501

- Huff, W. G., 1995, The developmental state, government, and Singapore’s economic development since 1960. World Development, 23(8), 1421–1438. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(95)00043-C

- Johnson, C. A., 1982, MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975 (CA: Stanford University Press)

- Kim, P. S. and Moon, M. J., 2003, NGOs as incubator of participative democracy in South Korea: Political, voluntary, and policy participation. International Journal of Public Administration, 26(5), 549–567. doi:10.1081/PAD-120019235

- Koh, D., 2020, Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 77(9), 634–636. doi:10.1136/oemed-2020-106626

- Lee, E. W. Y., 1999, Governing post-colonial Hong Kong: Institutional incongruity, governance crisis, and authoritarianism. Asian Survey, 39(6), pp. 940–959. doi:10.2307/3021147

- Lee, E. W. Y. and Haque, M. S., 2006, The new public management reform and governance in Asian NICs: A comparison of Hong Kong and Singapore. Governance, 19(4), 605–626. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2006.00330.x

- Lee, F. L. F. and Chan, J. M., 2018, Media and Protest Logics in the Digital Era: The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong (NY: Oxford University Press)

- Li, W. and Wong, W., 2019, Advocacy coalitions, policy stability, and policy change in China: The case of birth control policy, 1980-2015. Policy Studies Journal, 48(3), 645–671. doi:10.1111/psj.12329

- Liu, Z. and Geva-May, I., 2021, Comparative public policy analysis of COVID-19 as a naturally occurring experiment. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 23(2), 131–142

- Ma, N., 2007, Political Development in Hong Kong (H.K.: Hong Kong University Press)

- Migdal, J., 1988, Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World (N.J., Princeton: Princeton University Press)

- Migdal, J., 2001, State in Society (NY: Cambridge University Press)

- Moon, M. J., 2020, Fighting COVID-19 with agility, transparency, and participation: Wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 651–656. doi:10.1111/puar.13214

- Moon, M. J. and Ingraham, P., 1998, Shaping administrative reform and governance: An examination of the political nexus triads in three Asian countries. Governance, 11(1), 77–100. doi:10.1111/0952-1895.581998058

- Ney, S., 2012, Making sense of the global health crisis: Policy narratives, conflict, and global health governance. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 37(2), 253–294. doi:10.1215/03616878-1538620

- Nohrstedt, D., 2008, The politics of crisis policymaking: Chernobyl and Swedish nuclear energy policy. The Policy Studies Journal, 36(2), 257–278. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00265.x

- Ortmann, S., 2015, Political change and civil society coalitions in Singapore. Government and Opposition, 50(1), 119–139. doi:10.1017/gov.2013.41

- Ostrom, E., 1997, Crossing the great divide: Co-production, synergy, and development, in: P. B. Evans (Ed.) State-Society Synergy: Government and Social Capital in Development (Berkeley: University of Berkeley Press), 85–118

- Perry, M., Kong, L. and Yeoh, B., 1997, Singapore: A Developmental City State (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons)

- Peters, G. B. and Pierre, J., 1998, Governance without government? Rethinking public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(2), 223–243. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024379

- Peters, G. B. and Pierre, J. (Eds), 2004, The Politicisation of the Civil Service in Comparative Perspective: A Quest for Control (NY: Routledge)

- Pierson, P., 1993, When effect becomes cause: Policy feedback and political change. World Politics, 45(4), 595–628. doi:10.2307/2950710

- Pierson, P., 1994, Dismantling the Welfare State? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Putnam, R., 1993, Making Democracy Work (NJ: Princeton University Press)

- Quah, D., 2020, Singapore’s policy response to COVID-19, in: S. Agarwal, Z. He and B. Yeung (Eds.) Impact of COVID-19 on Asian Economies and Policy Responses (Singapore: World Scientific), 79–88

- Radin, B. A. and Weimer, D. L., 2018, Compared to what? The multiple meanings of comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 20(1), 56–71

- Rodan, G., 2003, Embracing electronic media but suppressing civil society: Authoritarian consolidation in Singapore. The Pacific Review, 16(4), 503–524. doi:10.1080/0951274032000132236

- Romzek, B. S. and Dubnick, M. J., 1987, Accountability in the public sector: Lessons from the challenger tragedy. Public Administration Review, 47(3), 227–238. doi:10.2307/975901

- Sabatier, P., 1988, An advocacy coalition model of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2–3), 129–168. doi:10.1007/BF00136406

- Schwartz, F., 2003, What is civil society, in: F. J. Schwartz and S. J. Pharr (Eds) The State of Civil Society in Japan (NY: Cambridge University Press), 23–41

- Scott, I., 2000, The disarticulation of Hong Kong’s post-handover political system. The China Journal, 43(Jan), 29–53

- Sellers, J. M., 2011, State-Society relations, in: M. Bevir (Ed.) The Sage Handbook of Governance (CA: Sage), 124–141

- Skocpol, T., 2004, Diminished Democracy (OK: University of Oklahoma Press)

- Skocpol, T. and Finegold, K., 1982, State capacity and economic intervention in the early new deal. Political Science Quarterly, 97(2), 255–278. doi:10.2307/2149478

- Tan, K. P., 2012, The ideology of pragmatism: Neo-liberal globalisation and political authoritarianism in Singapore. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 42(1), 67–92. doi:10.1080/00472336.2012.634644

- Tan, K. P., 2018, Singapore: Identity, Brand, Power (NY: Cambridge University Press)

- Van de Walle, S. and Brans, M., 2018, Where comparative public administration and comparative policy studies meet. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 20(1), 101–113

- Weiss, L. and Hobson, J., 1995, States and Economic Development: A Comparative Historical Analysis (Cambridge, MA: Polity)

- Wong, C. M. L. and Jensen, O., 2020, The paradox of trust: Perceived risk and public compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7–8), 1021–1030. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1756386

- Wong, W., 2013, The search for a model of public administration reform in Hong Kong: Weberian Bureaucracy, NPM or something else? Public Administration and Development, 33(3), 297–310. doi:10.1002/pad.1653

- Wong, W., 2021, When the state fails, bureaucrats and civil society step up: Analysing policy capacity with political nexus triads in the policy responses of Hong Kong to COVID-19. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 1–15. doi:10.1080/17516234.2021.1894314

- Wong, W. and Welch, E., 1998, Public administration in a global context: Bridging the gaps of theory and practice between Western and Non-Western nations. Public Administration Review, 58(1), 40–50. doi:10.2307/976888

- Woo, J., 2021, Pandemic, politics and pandemonium: Political capacity and Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 crisis. Policy Design and Practice, 4(1), 77–93

- Woo, J. J., 2018, The Evolution of the Asian Developmental State: Hong Kong and Singapore (London: Routledge)

- Woo, J. J., 2020, Policy capacity and Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy and Society, 39(3), 345–362. doi:10.1080/14494035.2020.1783789

- Woo-Cumings, M., 1999, The Developmental State (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press)

- Wu, A. M. and Zhu, L., 2020, Contact tracing: China’s health code offers some lessons. The Business Times, 16 July.

- Wu, X., Ramesh, M., and Howlett, M., 2015, Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competencies and capacities. Policy and Society, 34(3–4), 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.09.001