ABSTRACT

Purpose

This paper seeks to explore the manner in which secondary vocational education in agriculture can facilitate unlearning among young farmers. In this context, ‘unlearning’ means deliberately letting go of mindsets, practices, and routines that are no longer fit for purpose.

Design/Methodology/Approach

We use a course on sustainable family-farm succession as a case study in order to illustrate how unlearning may feature in agricultural education. We organised focus-group sessions with three teachers of that course. The sessions focused on three subprocesses of unlearning: (i) initial destabilisation, (ii) ongoing discarding and experimentation, and (iii) developing and relinquishing.

Findings

We show that teachers can facilitate unlearning, and discuss how teachers may help students to navigate intergenerational tensions in unlearning. We conclude that unlearning is a layered concept: it involves adaptation to a changing agriculture sector context as much as emancipation from the social context. We also show how expressions of solidarity and loyalty may undermine unlearning.

Practical implications

Agricultural educators are increasingly being tasked with helping future food professionals to manage the complexity of food systems. Our analysis points to means by which teachers who are seeking to reshape agricultural education may adopt the concept of unlearning in order to foster young farmers’ consciousness and agency in food system transformation.

Theoretical implications

A pedagogy of unlearning can contribute to designing education that enables young farmers to overcome path dependency in farm succession.

Originality/Value

This paper proposes unlearning as an innovative pedagogy for farmers’ training in view of food system transformation.

1. Introduction

Concerns about the ability of modern industrial agriculture to meet twenty-first-century expectations about sustainable food systems are mounting (Campbell et al. Citation2017; IPES-food and ETC Group Citation2021). Food systems are being challenged by persistent and complex issues, including interconnected ecological, health, social, economic, and cultural changes. Agricultural education, if it is to anticipate food system transformation, needs to equip students with new skills, attitudes, values, and types of knowledge so that they can predict and adapt to shifting societal and governmental demands by adopting new business models in a timely manner (Dooley and Grady Roberts Citation2020; Hartmann and Martin Citation2021).

Secondary vocational education and training in the Netherlands, which we will refer to as ‘MBO’Footnote1 hereafter, ‘prepares people for work and develops citizens’ skills to remain employable and respond to the need of the economy’ (EU Citation2021, np). MBO must align teaching with systemic changes and increased demand for skilled labour (Mitchell et al. Citation2003; Wals et al. Citation2004). However, the effort to surmount these challenges also requires a transformation of vocational agricultural education itself – it must provide training that not only increases subject knowledge among agricultural professionals but also empowers them and prepares next generations for a changing industry that is full of ‘uncertainties, tensions, barriers and ambiguities’ (Loorbach and Wittmayer Citation2023, 3; Østergaard et al. Citation2010; Sterling Citation2011; Tur Porres, Wildemeersch, and Simons Citation2014).

This paper aims to contribute to understanding and shaping transformative agricultural education at MBOs. In particular, we propose unlearning as an innovative pedagogy for farmers’ training in view of food system transformation. Unlike forgetting, which can be unconscious, unlearning entails a conscious decision to detach from and actively reject a previous position in order to welcome alternative or subaltern perspectives (Brook et al. Citation2016; Burt and Nair Citation2020; van Oers et al. Citation2023). ‘Old’ mindsets, perspectives, practices, or routines that are considered unsuccessful or inappropriate are discarded in a process of unlearning (Fiol and O’Connor Citation2017). Most definitions of unlearning suggest that there is a tension between past learning and the adoption of new perspectives, which is encouraged by critical reflection and active inquiry (Cochran-Smith Citation2003; Matsuo Citation2019). A pedagogy of unlearning received attention in anti-racist/anti-discriminatory/anti-violence teaching experiences and professional practice (e.g. Cochran-Smith Citation2000; Davies Citation2014) and its potential has been considered for transformative sustainability education too (e.g. Burns et al. Citation2022). However, it remains unclear how agricultural education can facilitate unlearning among students.

We explored this question by engaging with MBO teaching in the Netherlands and by using an extracurricular course on sustainable family-farm succession as a case study. We adopted a co-production approach, and we inquired how agricultural education may support three subprocesses of unlearning, namely (i) initial destabilisation, (ii) ongoing discarding and experimentation, (iii) and developing and relinquishing (Becker and Bish Citation2021; Fiol and O’Connor Citation2017).

The course on sustainable family-farm succession that we selected provided us with an especially interesting focus. Farm succession is a crucial moment of possibility for change, but it is also a process in which the capacity of path dependencies to block such change is at its most pronounced. Studies on family-farm succession have revealed the reluctance of older generations to step aside, and to transfer managerial duties and ownership to the next generation, which creates frictions (Conway et al. Citation2017; Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller Citation2003). The complex nature of family-farm succession can only be understood if one learns how the appointed successor navigates and potentially discards familial expectations, rights, and types of knowledge (Gill Citation2013). Practical involvement in the affairs of the farm and the identification of potential successors at an early age contribute to path dependencies, which are enforced by powerful genealogical analogies, such as, ‘you’re the offspring of what has been produced for generations’ (quoted in Fischer and Burton Citation2014, p. 425).

That young farmers are growing up in a changing and tumultuous ‘present’ (Friedrich, Faust, and Zscheischler Citation2023; Gill Citation2013) further complicates farm succession. For this reason, applying an unlearning perspective to a course on farm succession for Dutch livestock farmers is both timely and relevant. Many elements of the Dutch agricultural sector are being expected to adjust rapidly, and farmers are under immense pressure to make radical changes. The ongoing nitrogen crisis and the looming water-quality crisis (Stokstad Citation2019; Wuijts et al. Citation2023) have led scientists and government officials to call for the transformation of the Dutch food system repeatedly (e.g. Vermunt et al. Citation2022). Those calls tend to focus on the livestock sector. Efforts to curb the environmental impact of Dutch agriculture and to reduce nitrogen emissions, such as buy-out schemes in high-emissions areas, have been met with strong resistance and several mass demonstrations by farmers (van der Ploeg Citation2020). One sees the relevance of unlearning when one tries to understand what it means to be a farmer in an increasingly complex and uncertain world that requires mindsets, practices, and routines that no longer serve their purpose to be abandoned.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 conceptualises unlearning and its subprocesses. Section 3 describes the research design and the methods for data collection and analysis, as well as providing a more detailed introduction to the course that serves as the setting of our case study. Section 4 presents the findings from our focus-group conversations with the teachers on the course. The concluding Section 5 provides an outlook for agricultural educators who wish to consider incorporating unlearning into their teaching.

2. Conceptualising unlearning

This section introduces the term ‘unlearning’, which has been developed extensively in the literature on organisation, business, and management (e.g. Tsang and Zahra Citation2008) and in that on postcolonial and feminist literature (e.g. Spivak Citation1996). In addition, we draw insights from ‘transformative learning’, a well-established concept in the educational sciences (Mezirow Citation1991), which partly overlaps with unlearning as we understand it.

2.1. Defining unlearning

Unlearning has been defined in many ways in the literature. Most of those definitions proceed from the premise that it is an intentional process that involves individuals and/or organisations ‘abandoning’, ‘eliminating’, ‘rejecting’, ‘discarding’, ‘giving up’ or ‘stopping to use’ established practices and beliefs (e.g. Akgün et al. Citation2007; Brook et al. Citation2016).

In organisational theory, unlearning is perceived as key to increase an organisation’s capacity and flexibility to adapt to its environment (e.g. Cegarra-Navarro, Eldridge, and Martinez-Martinez Citation2010; Hislop et al. Citation2014; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008). If they are to survive and navigate turbulent environments, organisations must be prepared to abandon obsolete or outdated routines and to accommodate ‘better and more appropriate ones’ (Akgün et al. Citation2007; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008, 1438). Suboptimal organisational results can create doubts about the efficacy of established routines, and these doubts may initiate unlearning (Burt and Nair Citation2020). What we learn from this literature is that unlearning – also at the individual level – can be of strategic relevance and have utilitarian and rationalist motives (van Oers et al. Citation2023).

It has also been suggested that unlearning entails the uprooting and rejection of deeply held assumptions or beliefs (e.g. Choi Citation2008; Cochran-Smith Citation2000; Spivak Citation1996). It encourages individuals to detach from biased reasoning, defensive attitudes, and taken-for-granted assumptions that underpin their conscious and unconscious behaviours; those individuals then form new and less biased patterns of thought (Choi Citation2008; Cirnu Citation2015; Krauss Citation2019). Conner (Citation2010) concluded that ‘a key piece of unlearning is becoming keenly aware of some common understanding or way of acting that had previously gone unquestioned’ (117). The more ethically charged and, broadly speaking, political objectives of those who are involved in processes of unlearning have mainly been captured by feminist and postcolonial scholars. The scholars in question tend to consider the unlearning of subjectivities and identities to be an empowering and liberating process, ‘allowing meanings to be made and understandings to be found that would not otherwise be possible’ (Brook et al. Citation2016, 383; Davies Citation2014).

Originally, unlearning scholars tended to speak of the ‘discarding’ of a practice, habit, or routine (Fiol and O’Connor Citation2017; Tsang and Zahra Citation2008). At present, it is increasingly being suggested that learners might not be able to completely discard or eliminate previous knowledge, which would imply that unlearning is neither about forgetting nor about fully discarding old experiences. It would be more accurate, therefore, to define unlearning as a conscious decision to refrain from the continued use of particular values, knowledge, and/or behaviours (Hislop et al. Citation2014; Mavin, Bryans, and Waring Citation2004; van Oers et al. Citation2023). In a similar vein, Grisold, Kaiser, and Hafner (Citation2017) defined unlearning as ‘a process to reduce the influence of old knowledge’ (4,616) and to ‘free ourselves from our past’ (4,617). Burt and Nair (Citation2020) proposed that ‘unlearning requires letting go or relaxing the rigidities of previously held assumptions and beliefs, rather than forgetting them’ (12). In their discussions on unlearning racism, both Choi (Citation2008) and Cochran-Smith (Citation2000) considered unlearning to be a re-examination of past learning. In unlearning, the goal ‘is not to help people forget, but … to recognise that a current or old way of thinking is no longer effective or is incomplete’, or even harmful (Griffith and Semlow Citation2020, 377).

2.2. The process of unlearning

Unlearning should not be reduced to a single event or an end state in which an individual stops using a learned behaviour or rejects a long-held belief (Krauss Citation2019; van Oers et al. Citation2023). Instead, unlearning is an iterative process which is entangled with learning and involves mutually reinforcing feedback between the ‘old’ routines that are being discarded and the ‘new’ routines with which the individual is experimenting (Cegarra-Navarro and Wensley Citation2019; Fiol and O’Connor Citation2017; McLeod et al. Citation2020).

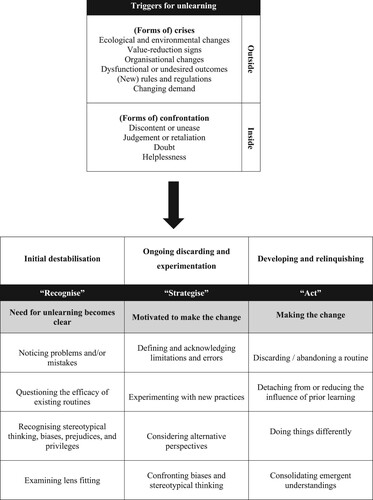

There have been numerous attempts to conceptualise the process of unlearning. For example, the process model of unlearning that Fiol and O’Connor (Citation2017) developed depicts unlearning by reference to three subprocesses: (i) the initial destabilisation of obsolete practices or beliefs, (ii) the displacement of old patterns of behaviour through experimentation and the discarding of old patterns; and (iii) the eventual release from old understandings and the development of new ones. It has been suggested that these three interactive subprocesses must occur before one can unlearn a deeply ingrained routine (Becker and Bish Citation2021). Along similar lines, Cegarra-Navarro, Eldridge, and Martinez-Martinez (Citation2010, but also 2019) cast unlearning as a process that begins with awareness, which is followed by relinquishing and (re)learning. In their study, unlearning transpired to begin with an ‘examination of the lens fitting’, which ‘refers to an interruption of the employees’ habitual, comfortable state of being’ (252). This process enables the individuals to access new perceptions. It is followed by changes to individual habits, when ‘an individual has not only understood the new idea but [is] motivated to make the change’ (252). The final stage entails the ‘consolidation of emergent understandings’ (252).

Griffith and Semlow (Citation2020) proposed a three-step process of unlearning. The three steps are deconstruction, reconstruction, and construction. In the deconstruction phase, the learner confronts their social world. The ‘key goal is to help people ‘read the world’ in such a way that they can recognise and “problematize” accepted explanations for the existence and persistence of [social phenomena]’Footnote2 (377). Strategies for addressing the limitations and errors that have been identified in this deconstruction exercise are proposed in the reconstruction phase, when different ways of understanding a particular phenomenon are evaluated. Finally, the goal of the construction phase is ‘praxis, or the creation of ways of thinking for the purpose of action and the expectation that insights from action will help to refine how we think about the problem and potential solutions’ (387).

Most scholars agree that unlearning is a process that responds to both external and internal triggers (Burt and Nair Citation2020; Fiol and O’Connor Citation2017). According to van Oers et al. Citation2023, a distinction can be drawn between the ‘forms of crises’ and the ‘forms of confrontation’ which may cause learners to embark on unlearning processes (van Oers et al. Citation2023). The authors distinguished between unlearning triggers to deal with environmental (‘outside’) changes and unlearning triggers emerging from confrontation and a desire to change from within (‘inside’) (see ).

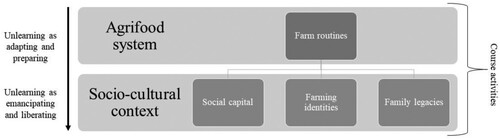

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of unlearning, based on van Oers et al. (Citation2023).

is based on van Oers et al. Citation2023 who for the first time combined strategic and pedagogical perspectives to capture unlearning in processes of sustainability transformation. The main focus of this paper is on the unlearning subprocesses that are presented in the three columns of . We made this decision in order to highlight the active involvement of teachers in facilitating and supporting unlearning by helping students to recognise, strategise, and act on the limits of their past learning. The triggers can be activated by the student, in virtue of the professional and personal experience that they bring to the classroom, or elicited by the teacher during a course.

2.3. Transformative learning

In the field of educational sciences, there is increased attention to forms of education that consider learning in terms of challenging underlying assumptions, paradigms, myths, stories and metaphors about the world and oneself (Brown Citation2005; Burns et al. Citation2022). Rather than referring to this as unlearning, though, Mezirow (Citation2000) calls this ‘transformational learning’ (TL) by which ‘we transform our taken-for-granted frames of reference […] to make them more inclusive, open, emotionally capable of change, and reflective so that they may generate beliefs and options that will prove more true or justified to guide action’ (7–8). TL should create conditions for learners to recognise and reflect on their reference frames that provide orientation for everyday actions (Sterling Citation2011). The outcomes of TL have been summarised as follows: ‘Acting differently; Having a deeper self-awareness; Having more open perspectives; Enhancing a deep shift in worldview’ (Stuckey, Taylor, and Cranton Citation2013, 217; Cranton and Taylor Citation2012).

TL’s aim of supporting reflective individuals as a precondition for changed mindsets overlaps with our understanding of unlearning, given that they both (a) characterise learning as a personal and emotional journey rather than a rational activity, (b) emphasise the importance of (critical) reflection, (c) emphasise the role of facilitators (or: teachers) to facilitate such reflection, and (d) consider the performativity of questioning past learning to make space for new perspectives. Yet, and whereas aforementioned outcomes of TL (‘Acting differently’, ‘Changed mindsets’ etc.) may overlap with unlearning outcomes, specific motivations and actions associated with unlearning are neglected in TL, most notably: the deliberate stoppage from retrieval and reproduction of knowledge, routines and mental models in discourses and practice (see van Oers et al. Citation2023).

This paper argues that learning to ‘think and act’ beyond the habitual implies a process of purposefully letting go. Nevertheless such unlearning remains obscured in TL. We consider transformative agricultural education from a pedagogy of unlearning, which brings in a clear imperative to disengage from previously held practices and beliefs (Akgün et al. Citation2007; Hedberg Citation1981; Matsuo Citation2019). To the authors’ knowledge, to date no study has applied unlearning to agricultural education and farmer’s training in MBO.

3. Material and methods

3.1. Case description

We used the extracurricular course Sustainable Family Farm Succession, which was organised at a Dutch MBO, as a case study in order to explore the manner in which agricultural education can facilitate unlearning. This course is designed for next-generation farmers and other agrarian professionals, and it is mostly attended by livestock farmers who are involved in the family business and intend to continue it. We provide an extensive definition of family-farm succession in Appendix 1.

The goal of the course is ‘to offer a programme in which future farm successors and their parents acquire knowledge and skills to start thinking about ownership transfer of the farm’ (PowerPoint slides, C.). The importance of parents and children ‘doing this together’ and understanding and sympathising with each other is stressed. In addition, the course deliberately positions family-farm succession within the challenging agrifood sector, which is strongly affected by fluctuations in demand, technology, policy, and the climate. The course offers a variety of interventions that can enable the participants to meet the financial, social, and communicative challenges that attend on farm succession.

The course is optional, and students and their parents join it on their own volition. They commit to six half-day sessions that are convened over a period of six months. The sessions are prepared by the teachers and do not take place at a school but at various external locations, such as farms in the region. Teachers often invite expert guest speakers from the agrifood sector to introduce each session. The topics range from the economic to the societal, and the activities include field trips and parent-student exercises. In the final session, the students present a plan for farm succession with their parent(s), if possible. contains an overview of the sessions that were held during the 2019–2020 edition of the course. The course has not been held in the last two years, but the teachers are aiming to reinstate it for the 2023–2024 academic year.

Table 1. Overview of sessions, Sustainable Family Farm Succession (2019–2020).

The course ran for the first time in 2017–2018, and has thus far run a total of 3 times. It is advertised in regular educational programmes, and it targets students in the final year of their MBO (age: 18–22), who must pass on the invitation to one or both of their parents and/or to other relatives. The teachers deliberately opt for a smaller group of between 8 and 12 students with one or more parent(s) to ensure personal interaction during sessions and farm visits. The students are expected to join all sessions, and they receive a certificate of participation at the end of the course. The five programmed sessions are designed to inspire the students to present their first visions and ideas for their takeover of the farm during the final session. There are neither graded assignments nor strict guidelines on the form and structure of the presentation.

3.2. Data collection and analysis

The qualitative study that this paper describes and analyses is an attempt to explore the means by which the course on family-farm succession may support unlearning. In designing this research, we built on constructivist pedagogy and assumed that teaching entails the facilitation of (un)learning and the creation of (un)learning opportunities, with students being active participants in the learning processes who shape what is learned, how it is learned, and when it is learned (Smith and Blake Citation2005). We analysed the teachers’ responses about the subjects that are taught, rather than learned, during the course because, according to Biesta (Citation2013, 460) ‘that what makes the school a school is the fact that it is a place for teaching’. Therefore, we can discuss the techniques that teachers use to facilitate unlearning in a manner that does not reduce them to ‘guides-on-the-side’ but acknowledge their roles as ‘classroom designers, editors, and assemblers’ (McWilliam Citation2008, 256). This research is primarily based on the reflection of teachers given that we aim to explore how unlearning may be facilitated in course design and teachers’ roles such facilitation. We therefore remain cautious in making claims about actual unlearning outcomes that occurred in the course.

The first author of this paper, as the focus group leader, adopted a participatory action research approach (cf. Wittmayer and Schäpke Citation2014). During each session, the first author alternated between roles of facilitation, participation and observation. The sessions were organised by the first author and their design were consulted with the other authors and with the teachers before the start of each session. The aim was to have an open discussion about how the course on family-farm succession and its activities facilitates unlearning. The teachers were encouraged to decide on the speed and direction of the sessions, without the focus group leader setting any expectations about desired outcomes. While having the ambition to guide group discussions as ‘neutral’ as possible, teachers’ expectations about the process and its outcomes; and their perception of the focus group leader as an ‘expert’ on unlearning evidently influenced the discussions (cf. Braakman Citation2003). Specific moments were allocated – during sessions and in between sessions – to collectively and transparently reflect on such issues.

3.2.1. Preparation phase

The first author of this paper held several exploratory meetings with the designers of the original course and the teachers (V. and C.) in preparation for the focus-group sessions. Those meetings enabled us to familiarise ourselves with the course and to arrive at a collective understanding of the aim of the project. These meetings lasted about an hour and were held either in person or online.

In order to organise and guide the main focus-group sessions, the first author conducted a study of other unlearning workshops and courses, and they interviewed the organisers of those courses about their experiences with unlearning. They conducted five semi-structured interviews that lasted 55 min on average. Two of the interviewees were involved in the organisation and design of unlearning experiments. The other interviewees included an alumnus of the 2018–2019 edition of the Sustainable Farm Succession course and two higher-education teachers whose teaching is based on transformative learning. The interview questions concerned the interviewees’ understanding of the concept of unlearning, the activities that can induce unlearning and/or transformative learning, and general experiences with the design of and/or participation in a course that is premised on unlearning or transformative learning. Finally, we reviewed publicly available training materials and reports from the Racial Justice Network (2023),Footnote3 the School of Unlearning (2022),Footnote4 and Unlearning Exercises (Casco Citation2019). The data was collected continuously and iteratively throughout the focus-group sessions, with each session informing new search directions.

3.2.2. Focus-group sessions

Our primary sources of data for this paper are the three focus-group sessions that were attended by the original course initiators (V. and C.), a teacher and teaching consultant (G.), and the first author of the paper (L.). Both V. and C. have been involved in all runs of the course and G. in the design of the last run. All three teachers have worked at MBO institutes for agricultural education for a long time and are most familiar with the type of students and families the course attracts. The sessions took place in April, May, and June of 2023. They were held in person. Each lasted between 2 and 3 h. All three sessions contributed to our understanding of the teachers’ recognition of unlearning in the course on family-farm succession. Each focus-group session unpacked different elements of the course. In Session 1, the participants explored the objectives of the course. In Session 2, the focus was on course activities. Session 3 covered the setting of the course, including the role(s) of teachers. The aim of each session was to enable the participants to discuss whether and in what ways the course contributed to unlearning and in what ways it could contribute to it in the future.

The sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. The transcripts were analysed through an iterative coding process. First, the relevant data on unlearning were selected from the transcripts and categorised in accordance with the subprocesses that are depicted in . In an iterative process of reflection, the findings that emerged from each session were discussed with the teachers, and the co-authors discussed the analysis of the data among themselves.

4. Findings

We present the findings from the study in the three subsections that follow. In Section 4.1, we briefly describe how the teachers came to understand unlearning in the context of farm succession. In Section 4.2, we explain how the course may be tailored to different unlearning subprocesses.Footnote5 In Section 4.3, we inquire how the course may help students to navigate intergenerational tensions by facilitating unlearning.

4.1. How the teachers came to understand unlearning

The teachers were introduced to the concept of unlearning during this project. They interpreted unlearning as a generative process in which letting go becomes a catalyst for transformative change. For example, V. suggested that ‘unlearning can help students to widen their scope of possibilities … to make space for novelty, previously unknown or disregarded’ (V.). In addition, the teachers recognised that unlearning can help young farmers to manage the turbulence that presently typifies the sector. To C., this meant that students should be asked questions such as, ‘What do you, as a young farmer in the Netherlands, need in order to prepare for the future? What needs to be picked up differently, thus unlearned, so that you can put what you have learned into practice?’.

In order to visualise unlearning, and specifically its liberating properties, one of the teachers introduced the metaphor of being ‘wrapped up in a cocoon’ (G.). This metaphor, which the other two teachers endorsed, recurred frequently during the group sessions. It builds on the twofold meaning of the Dutch word ‘ontwikkelen’ (‘to develop’ and ‘to untangle’). The metaphor casts unlearning as a process by which one breaks the ‘wraps’ or ‘tangles’ that surround one, that is, one’s accumulated learning, in order to reclaim space for further development. According to the teachers, an unlearning perspective on farm succession would help their students to (a) recognise how they are shaped, defined, encouraged, and restricted by these wraps as well as (b) find the ‘courage’ (C.) to leave those wraps behind in a process of liberation and emancipation. This process includes abandoning farm routines as much as it entails ‘breaking free’ (V.) from sociocultural expectations, demands, and identities.

As we were seeking an appropriate Dutch translation of the English term ‘unlearning’, we discovered that its direct Dutch analogue (‘afleren’) carries a ‘paternalistic connotation’ (V.) and ‘a judgemental tone’ (C. and G.) Therefore, we came to prefer the English word. In this regard, the teachers indicated that unlearning should not be about telling students ‘what’ they should cease to think or do but rather about creating conditions that encourage students to unlearn. The teachers insisted that they ‘cannot and will not tell their students what to unlearn’ because they wished to ‘grant students agency in their own unlearning’ (G.). They preferred to avoid the ‘counterproductive reactions’ (V.) that they thought would result from non-self-motivated unlearning. Instead, our conversations about unlearning revolved around the teachers’ roles in emphasising the importance of letting go during farm succession or other agricultural transitions.

The teachers agreed that, in family-farm succession processes, unlearning occurs against the backdrop of a familial legacy of decisions, priorities, and expectations, which, of course, also has to do with the history of Dutch agriculture. The teachers agreed that, from the point of view of the heir to the farm, unlearning is likely to be uncomfortable and conflict ridden. Even when they want to eliminate some element of their heritage, such heirs might encounter difficulties in enacting their plans because certain farming practices are ‘in their DNA’ (G.).

4.2. Identifying unlearning in the course on farm succession

This section discusses the means by which the course on sustainable farm succession facilitates unlearning. The findings are presented by reference to the unlearning subprocesses that are depicted in .

4.2.1. Initial destabilisation (‘recognise’)

We discussed the way in which the course on family-farm succession may help students to recognise the need for unlearning. In particular, we focused on the ways in which course activities could encourage reflection on established farm practices, routines, and beliefs, thus enabling recognition of the potential limits of their past learning.

The course would usually start with a presentation that would cast succession as a process in which ‘flexibility’ is necessary to ‘make space for the next generation’. The course materials make this argument explicit by presenting farm succession as an X-shaped curve in which the downward curve represents the disempowerment of the incumbent farmers and the upward curve represents the empowerment of the students, with a ‘friction period’ at the intersection of the two curves. One of the teachers framed that potential friction as follows: ‘When are parents ready to let go and initiate change, and when will their son or daughter be given the space and confidence to join in?’ (C.).

In this way, the teachers cast succession as a process of letting go that should involve preliminary discussions about the transfer of the management of the farm. The course mostly revolved around the promise of unlearning as a ‘liberating exercise for students’ (V.), who may have felt encouraged to reflect upon, challenge, and deviate from settled trajectories. Indeed, for students, the acknowledgement that ‘they have a choice and it is okay to do things differently’ (G.) implies the possibility of deviating from deeply internalised ideas about farm inheritance and family farming,

After five sessions, the students would be expected to present their initial vision for their takeover of the family farm. The teachers suggested means by which the different activities that formed part of the course could help students in their quest to become heirs to the farm. The course would begin with the proposition that ‘being a farmer today requires a different kind of entrepreneurship than in the past. Developments such as climate change, the changing environment, governmental decisions, public-health issues, and declining meat consumption are to be included in farm visions’ (PowerPoint Slides, C.). One of the teachers celebrated the course as an initial step towards overcoming path dependency in farm succession. Students would tend to perpetuate genealogical analogies: ‘[my parents] have always done it that way, so why would I do it differently?’. Those students could subsequently realise that they possess the agency to deviate from set paths that are no longer productive. V. explained how the course is unique in its ambition to challenge what students take for granted in farming and farm succession. C. added, ‘The course helps students to navigate new agricultural relations, in which process they may have come to realise that present-day society might not want them to do what their parents did’.

The teachers demonstrated how the course may help students to recognise the need for unlearning in farm succession and how the course activities were designed to introduce students to new perspectives and alternative farming methods and business models. To the teachers’ understanding, farm visits and encounters with novelty would contribute to the deconstruction of stereotypical thinking and biases against farming models that differ from the ones to which the students were accustomed. During the course, the students would visit regional farmers whom the teachers would select due to the novelty of their business models. Those farmers were often young and had disrupted family models in their farm succession. According to V., it ‘has always been a deliberate choice to visit places and farmers of whom the students may hold biased and/or stereotypical interpretations: organic, vegan, small scale, etc.’.

G. suggested that, in future editions of the course, the teachers should ask the farmers whom they invite to participate to be explicit about their unlearning experiences so as to inspire the students to recognise and normalise that process in farm succession. She saw the benefits of ‘asking entrepreneurs to be transparent about choices and experiences that shaped them to be the persons that they are today: what have they learned, but also what did they have to unlearn to get there’ (G.).

In order to help the students to notice failures in the prevalent farming models and to become aware of their agency in food system transformation through unlearning, the teachers would develop activities that can be interpreted as triggers for unlearning. In the first session of the course, students and their parents are invited to a lecture on the changing agricultural sector in the Netherlands. That lecture covers the most important trends that have been observed over the past decade. In addition, the teachers saw the mere fact that the course would remove students and their parents from their day-to-day farming routines as an important trigger for unlearning: ‘If you are working on autopilot, it is actually a gift … those six evenings when you can think and say to each other: Why are we doing this?’ (V.)

4.2.2. Ongoing discarding and experimentation (‘strategise’)

We now turn to the ways in which the course may encourage students to propose strategies for overcoming the limitations of established farm routines and to experiment with new ones. We also demonstrate how the course may prompt the students to confront their biases and their stereotypical thinking and to consider alternative perspectives as legitimate.

The teachers explained that the students are asked to incorporate the knowledge that they had acquired during the course into their final presentation on their visions for farm succession. This future-vision exercise can help students to think strategically about the practices that they need to abandon as well as the steps that they need to take in order to initiate that transition. G. proposed that, in the next editions of the course, the students should be asked explicitly to reflect on unlearning in this process.

Much of the conversations about ongoing discarding and experimentation gravitated towards making the course a safe spaces in which the students can consider alternatives to their parents’ farm routines. The teachers observed their role in nurturing ongoing unlearning, which is additional to the aforementioned roles in probing and facilitating initial destabilisation (see Section 4.2.1). The teachers believed that their role would require them to be attentive and to prepare, as much as possible, for the potential frictions and the emotional resistance that course activities which are directed at unlearning may engender.

Furthermore, the teachers argued that the students’ decision to participate in an extracurricular course with their parents might be interpreted as an act of care and as a sign of ongoing unlearning: ‘by doing this together, they have overcome an important first emotional barrier’ (G.). C. shared,

Yes, I always find it so beautiful that they come together and that they get into that car and go home together, so that is already an important moment … when they drive together to [the session] and back together, or … it is quiet in the car. (C.)

4.2.3. Developing and relinquishing (‘act’)

We also discussed how the course does or may support students in discarding old routines and in adopting new ones, in purposefully detaching from past behaviours and beliefs, and in consolidating emerging understandings.

Due to the duration of the course, the teachers concluded that it would not be feasible for it to be designed to support the ‘act’ of unlearning, that is, the deliberate rejection of certain practices or beliefs. However, they did mention that the presence of certain emotions and tensions hinted at relinquishment, sometimes during the course but usually during the final presentations. For example, V. shared, ‘during those presentations, I often found it very moving … some students, who were very resistant … and then come up with very beautiful things, which make me think that they are really breaking free from something’ (V.). Similarly, C. added: ‘It is nice to see when [students and parents] have been here, and you see that something has been broken open – that is our first objective’.

4.3. Navigating intergenerational tensions by facilitating unlearning

The discussion on facilitating unlearning that follows draws on Fiona Gill’s (Citation2013) seminal work. She introduced temporal elements to the literature on farm succession. We use it to demonstrate how the course has to strike a balance between unlearning as confronting the discord between current farming practices and contemporary agricultural realities and unlearning as liberation from parental expectations and farming identities. That balance, moreover, has to be struck in a manner that recognises solidarity and loyalty between generations of farmers and different farming communities.

The course on farm succession revolved around the following question: ‘in what way do you think you can take over the farm in the future, and how can you get there together with your parents?’(C.). For this reason, the course is unique in involving both students and parents, whose realities are linked by common familial and commercial experiences, memories, and routines, in an extracurricular setting.

As an heir prepares to take over a farm, they are caught between their responsibilities to the past and the future generations, which, according to the teachers, has implications for unlearning. Our conversations with the teachers turned our attention to the question of how teachers may respond to students’ resistance and reluctance to engage in critical reflection and discard established routines. For example, V. shared that what students often tell her is: ‘How am I going to do things differently without insulting my parents, without giving my mom and dad the feeling that they haven’t done it well?’ (V.). These students, in particular, V. added, ‘are very likely to revolt against the idea of unlearning if they feel it means being disloyal to their parents – “how we have always done it, how I have learned to do it”’ (V).

Facilitating unlearning, then, may help students to manage the discomfort and the emotional pain that accompany the re-evaluation of past learning. Past learning that is shared between generations of farmers and rooted in a historical and sociocultural assemblage of family, farm, and community relations (depicted in ). Indeed, the teachers acknowledged the ‘difficulties of radically deviating from parents to take the opposite turn’ (G.), and suggested that ‘students can only break away from the current models, from the current business models, if they no longer have to feel like they are losing their parents’ (V.).

Thus, attempts to unlearn in order to prepare for the future and to adapt to a changing agricultural sector are likely to be obstructed by the students’ reluctance to reject parental decisions and expectations and to distance themselves from them, ‘not out of ignorance but out of solidarity and respect’ (G.). V. shared,

I have also dried tears from students, who say: I don’t dare to talk to my mom and dad because I am afraid. That conflict, that feeling of ‘it’s like I’m criticising them; I don’t mean that at all’, that’s already where the blockage is. We encourage them to actually talk to each other, which, in my opinion, is a great asset of this course. (V.)

The teachers suggested that, beyond excluding parents from certain activities, they would mediate intergenerational differences by contextualising the choices that were made in farming in the past and which are being made at present instead of discrediting either. In this context, the teachers acknowledged that appeals to unlearn familial farm routines may appear judgemental if the circumstances of the learning processes of the past are overlooked. V. shared the following example of good practice: ‘I admire how you do that C. You always say: I taught your parents. But the reality is, the world has changed, so we have to adjust, we have to change, that is just the way it is’ (V.).

The teachers agreed on the important role of the course in helping students recognise that they can make choices in farm succession and ‘that it is okay to do things differently’. The students thus ‘realise that their parents also had to make a choice’ (G.) To that end, the teachers suggested adding a new student-parent activity to the course, in which they would draw a timeline of the farm, focusing on the choices that were made in the past:

If we can facilitate that conversation, about how mom and dad also had to make difficult choices, and why they made those specific choices, then a son or daughter hopefully feels confident to say: I too can make different choices. (V.)

The teachers suggested that the parents of the students are likely to have had have similar conversations with their parents, and they thought that sharing such intergenerational experiences of emancipatory unlearning may be a welcome addition to the course: ‘As long as we teach, there has always been something, and choices have always been made. Parents had to change and wanted to change. Making these choices transparent will help students and parents understand each other better’ (C.). The idea is that students ought to understand that ‘if my dad has made that decision, regardless of whether that turns out to be a good decision or not, it means that I can do that too – that is, kind of, a liberating feeling in itself’ (G.). Indeed, such conversations may initiate the unlearning of certain family conventions, including ‘unlearning a deeply rooted culture of not talking about emotions or voicing difficulties and doubts’ (V.).

4.4. Summary of findings

Our findings demonstrate how the course on farm succession may facilitate unlearning. They also show how the course is attuned to the initial deconstruction phase in which students become aware of the need to unlearn. Farm visits were mentioned as an important activity that can trigger the rejection of acquired biases. In addition, we explained how the course can alleviate the intergenerational tensions that farm succession brings about by facilitating unlearning. The teachers mentioned that students may perceive the unlearning of farm routines and practices as highly uncomfortable due to their reluctance to criticise their parents’ ways of farming and living.

In line with Gill (Citation2013), we emphasise that young farmers are caught between their responsibilities to different generations, which has obvious implications for the manner in which unlearning can and should be taught. If unlearning is about ‘letting go or relaxing the rigidities of previously held assumptions and beliefs’ (Burt and Nair Citation2020, 2), then our study stresses the manner in which these assumptions and beliefs are shared between and institutionalised within generations of farmers. Accordingly, to unmake a farm routine is to challenge the deep sociocultural foundations of farming and rural life – practicing farming in a certain way is grounded in social capital, farming identities, and family legacies. A firm commitment to old ways is therefore an expression of loyalty and social solidarity, which have a deeper meaning for young farmers than routines or practices per se. This finding casts doubt on the utilitarian and rationalistic perspectives on unlearning, whose proponents define that process as the abandonment of everything that no longer works. Teaching unlearning, when approached from this vantage point, entails balancing between adaptation and preparation; and unlearning as emancipation and liberation (). It is teachers who may facilitate the constant negotiation for which these processes call.

5. Concluding remarks

One of the objectives of secondary vocational education is to prepare young food professionals, including farmers, to work in current and future societies (EU Citation2021; OECD Citation2018; Østergaard et al. Citation2010). This paper considered unlearning as an innovative pedagogy for farmers’ training in the context of the transformation of Dutch food systems. We used a course on farm succession as an illustration of the means by which agricultural education may facilitate unlearning. Rather than providing a blueprint for unlearning, our findings should serve as an inspiration for teachers who wish to facilitate unlearning processes in agricultural education and who are mindful of the tendency of acquired farm routines to be rooted in social capital, farming identities, and family legacies. While our research is based on data from in-depth group sessions with teachers of a single course, the findings presented in this article have the potential to provoke new perspectives and practices in the delivery of agricultural education curricula.

With these considerations in mind, we propose to conclude by explaining how teachers can support unlearning. We consider teachers to be important ‘unlearning facilitators’ because students might be unaware of the need to unlearn or reluctant to do so because they dread the idea of confronting their past learning and challenging their peers and parents.

First, teachers may initiate and support unlearning in the context of the ecological, social, and economic pressures that have gripped food systems. Our findings confirm that unlearning is relevant to preparations for farm succession in a changing world. Course activities can be designed to help students to see the limits of their past learning and to become aware of the need to unlearn promptly. Since students might be unaware that they are unconsciously perpetuating taken-for-granted ways of being and doing (Stokke Citation2021), we argue that agricultural education can play a key role in the initial phases of destabilisation. In this regard, our findings confirm that ‘a bedrock for critical unlearning is the provision of encounters – with those of different (identity groups or ideological) backgrounds … which at the same time expose participants to alternative versions of the truth’ (Davies Citation2014, 465). At the same time, our findings show that unlearning cannot be taught through pleas that ‘convince’ young farmers to reject certain practices and beliefs and that, as Davies (Citation2014) wrote aptly, unlearning is not ‘about teachers “channelling” students into what they see as suitable activism, but about taking the risk to foster young people’s own initiatives’ (459). The questions that were posed at the start of each Section 4.2.1–4.2.3, which are summarised below () may inspire other teachers to design courses with unlearning in mind and to set up classrooms as unlearning spaces in which unlearning is pursued but not guaranteed.

Table 2. Suggested prompts to consider when incorporating unlearning into course design.

Second, our study revealed the importance of agricultural education as a ‘safe space’Footnote6 that accounts for sociocultural demands and expectations and helps students to break free from them through unlearning. Given the food system transformations that are expected to occur in the future, the unlearning of formulas for success that have proven useful in the past might be essential. At the same time, this unlearning is emotionally painful, and it can induce feelings of guilt and betrayal. We demonstrated how teachers can design course activities and settings so as to help students to navigate intergenerational tensions and to emancipate themselves from the past of their family farm. Their beliefs about the legitimate behaviour of farm heirs may be internalised rather than articulated fully (Spivak Citation1996). Previously, unlearning scholars have underestimated the role of loyalty and solidarity and tended to overemphasise goal-performance mismatches, leading to a rather rationalistic and functional treatment of the concept (van Oers et al. Citation2023). Farming is widely considered to be a way of life rather than a job, and it is associated with certain cultural and emotional values, family traditions, norms, ideologies, and behaviours (Conway et al. Citation2017). As we observed in the context of farm succession, unlearning may prompt students to deviate from the past learning that is rooted in forms of social capital of this kind, as well as in farming identities and family legacies. Beyond jeopardising certain routines, unlearning puts pressure on general social relations. That pressure may transpire to be a major deterrent to unlearning. Consequently, agricultural transitions are shaped and influenced by the conflicting and potentially irreconcilable implications of unlearning that may, in practice, favour the resumption of business as usual. This finding is important for transition scholars and practitioners interested in the drivers and obstacles that determine the utility of unlearning for the creation of a more sustainable and just agrifood futures. Thus far, that scholarship has neglected solidarity, loyalty, and sociocultural legacy as explananda.

Third, we added to the studies that depict unlearning as a process that is ‘deeply emotional and challenging as it brings individuals’ values, knowledges and practices into question’ (Burkšienė Citation2016, 31) by positing that ‘transition pain’Footnote7 is not an undesirable side effect of unlearning in agricultural transitions but part and parcel of it. The ability of teachers to foster the processes by which students navigate between maintenance work, through which they pass on what they have inherited and what performs well, and deconstruction work as part of their unlearning is of paramount importance in transformative agricultural education (Tur Porres, Wildemeersch, and Simons Citation2014). As a concluding recommendation for future practice and research, we invite agricultural educators to teach for unlearning in line with the particularities of their students and courses and to analyse their experiences for comparative purposes. We investigated an extracurricular course, which may have given the teachers a wider discretion to experiment with innovative pedagogies. In the future, researchers and practitioners may find it fruitful to reflect on the possibility of introducing unlearning into mandatory secondary vocational training and education. This development may require a shift from teaching for the job market and in line with existing contextual conditions to teaching for transformation in order to address the root causes of global and local challenges.

Author contributions

LvO – Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

GF – Conceptualisation; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Writing – review & editing.

EM – Conceptualisation; Writing – review & editing.

HR – Conceptualisation; Writing – review & editing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding provided by the European Research Council (Starting Grant 802441) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Vidi Grant 016.Vidi.185.173).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura van Oers

Laura van Oers is a PhD graduate of the Environmental Governance group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Giuseppe Feola

Giuseppe Feola is an Associate Professor at the Environmental Governance group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Ellen Moors

Ellen Moors is a Professor at the Innovation Studies group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Hens Runhaar

Hens Runhaar is a Professor at the Environmental Governance group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Notes

1 Middelbaar Beroepsonderwijs (MBO). After secondary education, MBO prepares students for a wide range of occupations and professions. The levels of training range from assistant training (1) to middle-management training (4). MBO combines practical training with classroom learning (Rijksoverheid Citation2023).

2 Griffith and Semlow (Citation2020) studied health disparities and health equity.

3 Accessible online : https://racialjusticenetwork.co.uk/causes/unlearning-racism/.

4 Accessible online: https://www.ahk.nl/onderzoek/artist-in-residence-air/2021-2022/school-of-unlearning-2022/.

5 All quotations were translated from Dutch to English by the first author of the paper.

6 Conversely, Arao and Clemens (Citation2013 proposed to create brave spaces, ‘shifting away from the concept of safety and emphasizing the importance of bravery instead, to help students better understand—and rise to—the challenges of genuine dialogue on diversity and social justice issues’ (136).

7 The concept was coined by Kristina Bogner et al. (forthcoming).

References

- Akgün, A. E., J. C. Byrne, G. S. Lynn, and H. Keskin. 2007. “Organizational Unlearning as Changes in Beliefs and Routines in Organizations.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 20 (6): 794–812. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810710831028

- Arao, B, and K. Clemens. 2013. “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces 135-150..” In The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators, edited by L. Landreman, 135–150. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Becker, K., and A. Bish. 2021. “A Framework for Understanding the Role of Unlearning in Onboarding.” Human Resource Management Review 31 (1): 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100730

- Bertolozzi-Caredio, D., I. Bardaji, I. Coopmans, B. Soriano, and A. Garrido. 2020. “Key Steps and Dynamics of Family Farm Succession in Marginal Extensive Livestock Farming.” Journal of Rural Studies 76:131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.030

- Biesta, G. 2013. “Receiving the Gift of Teaching: From ‘Learning from’to ‘Being Taught By’.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 32 (5): 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-012-9312-9

- Bloemen-Bekx, M., F. Lambrechts, and A. Van Gils. 2021. “An Exploration of the Role of Intuitive Forms of Planning in the Succession Process: The Explanatory Power of Effectuation Theory.” Journal of Family Business Management 13 (2): 486–502.

- Braakman, L. 2003. “The Art of Facilitating Participation: Unlearning Old Habits and Learning New Ones.” Planotes 15.

- Brook, C., M. Pedler, C. Abbott, and J. Burgoyne. 2016. “On Stopping Doing Those Things That are not Getting us to Where we Want to be: Unlearning, Wicked Problems and Critical Action Learning.” Human Relations 69 (2): 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715586243

- Brown, K. M. 2005. “Social Justice Education for Preservice Leaders: Evaluating Transformative Learning Strategies.” Equity & Excellence in Education 38 (2): 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680590935133

- Burkšienė, V. 2016. “Unlearning and Forgetting for Sustainable Development of Contemporary Organizations: Individual Level.” Organizacijų vadyba: sisteminiai tyrimai 75:25–40.

- Burns, H., N. Stoelting, J. Wilcox, and C. Krystiniak. 2022. “One of the Doors: Exploring Contemplative Practices for Transformative Sustainability Education.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Learning for Transformation, edited by A. Nicolaides, S. Eschenbacher, P. T. Buergelt, Y. Gilpin-Jackson, M. Welch, and M. Misawa, 129–146. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Burt, G., and A. K. Nair. 2020. “Rigidities of Imagination in Scenario Planning: Strategic Foresight Through ‘Unlearning’.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 153:119927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119927

- Campbell, B. M., D. J. Beare, E. M. Bennett, J. M. Hall-Spencer, J. S. Ingram, F. Jaramillo, R. Ortiz, et al. 2017. “Agriculture Production as a Major Driver of the Earth System Exceeding Planetary Boundaries.” Ecology and Society 22 (4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09595-220408

- Casco. 2019. Unlearning Exercises: Art Organisations as Sites for Unlearning, 166. Edited by Binna Choi, Annette Krauss, Yolande van der Heide and Liz Allan, Amsterdam, 2018: Valiz, Casco.

- Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., S. Eldridge, and A. Martinez-Martinez. 2010. “Managing Environmental Knowledge Through Unlearning in Spanish Hospitality Companies.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (2): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.11.009

- Cegarra-Navarro, J. G., and A. Wensley. 2019. “Promoting Intentional Unlearning Through an Unlearning Cycle.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 32 (1): 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-04-2018-0107

- Choi, J. A. 2008. “Unlearning Colorblind Ideologies in Education Class.” Educational Foundations 22:53–71.

- Cirnu, C. E. 2015. “The Shifting Paradigm: Learning to Unlearn.” Journal of Online Learning Research and Practice 4 (1): 26926.

- Cochran-Smith, M. 2000. “Blind Vision: Unlearning Racism in Teacher Education.” Harvard Educational Review 70 (2): 157–190. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.70.2.e77x215054558564

- Cochran-Smith, M. 2003. “Learning and Unlearning: The Education of Teacher Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 19 (1): 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00091-4

- Conner, J. O. 2010. “Learning to Unlearn: How a Service-Learning Project Can Help Teacher Candidates to Reframe Urban Students.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (5): 1170–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.02.001

- Conway, S. F., J. McDonagh, M. Farrell, and A. Kinsella. 2017. “Uncovering Obstacles: The Exercise of Symbolic Power in the Complex Arena of Intergenerational Family Farm Transfer.” Journal of Rural Studies 54:60–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.06.007

- Cranton, P., and E. W. Taylor. 2012. “Transformative Learning Theory: Seeking a More Unified Theory.” In Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by E. W. Taylor and P. Cranton, 3–20. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Daspit, J. J., D. T. Holt, J. J. Chrisman, and R. G. Long. 2016. “Examining Family Firm Succession from a Social Exchange Perspective: A Multiphase.” Multistakeholder Review. Family Business Review 29 (1): 44–64.

- Davies, L. 2014. “Interrupting Extremism by Creating Educative Turbulence.” Curriculum Inquiry 44 (4): 450–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/curi.12061

- Dooley, K. E., and T. Grady Roberts. 2020. “Agricultural Education and Extension Curriculum Innovation: The Nexus of Climate Change, Food Security, and Community Resilience.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 26 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1703507

- EU. 2021. “Vocational Education and Training.” https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/vocational-education-and-training/about-vocational-education-and-training.

- Fiol, M., and E. O’Connor. 2017. “Unlearning Established Organizational Routines.” The Learning Organization 24 (1): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-09-2016-0056

- Fischer, H., and R. J. Burton. 2014. “Understanding Farm Succession as Socially Constructed Endogenous Cycles.” Sociologia Ruralis 54 (4): 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12055

- Friedrich, J., H. Faust, and J. Zscheischler. 2023. “Incumbents’ in/Ability to Drive Endogenous Sustainability Transitions in Livestock Farming: Lessons from Rotenburg (Germany).” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 48:100756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100756

- Gill, F. 2013. “Succession Planning and Temporality: The Influence of the Past and the Future.” Time & Society 22 (1): 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X10380023

- Griffith, D. M., and A. R. Semlow. 2020. “Art, Anti-Racism and Health Equity:“Don’t Ask Me Why, Ask Me How!”.” Ethnicity & Disease 30 (3): 373. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.30.3.373

- Grisold, T., A. Kaiser, and J. Hafner. 2017. “Unlearning Before Creating New Knowledge: A Cognitive Process.”

- Hartmann, K., and M. Martin. 2021. “A Critical Pedagogy of Agriculture.” Journal of Agricultural Education 62 (3): 51–71.

- Hedberg, B. 1981. “How Organizations Learn and Unlearn.” In Handbook of Organizational Design, edited by P. C. Nystrom and W. H. Starbuck, 3–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hislop, D., S. Bosley, C. R. Coombs, and J. Holland. 2014. “The Process of Individual Unlearning: A Neglected Topic in an Under-Researched Field.” Management Learning 45 (5): 540–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507613486423

- IPES-Food & ETC Group. 2021. “A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045.”

- Krauss, A.. 2019. “Unlearning Institutional Habits: An Arts-Based Perspective on Organizational Unlearning.” The Learning Organization 26 (5): 485–499.

- Loorbach, D. A., and J. Wittmayer. 2023. “Transforming Universities: Mobilizing Research and Education for Sustainability Transitions at Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.” Sustainability Science 19 (1): 19–33.

- Matsuo, M. 2019. “Critical Reflection, Unlearning, and Engagement.” Management Learning 50 (4): 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507619859681

- Mavin, S., P. Bryans, and T. Waring. 2004. “Unlearning Gender Blindness: New Directions in Management Education.” Management Decision 42 (3/4): 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740410522287

- Mazzola, P., G. Marchisio, and J. Astrachan. 2008. “Strategic Planning in Family Business: A Powerful Developmental Tool for the Next Generation.” Family Business Review 21 (3): 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865080210030106

- Mcleod, K., S. Thakchoe, M. A. Hunter, K. Vincent, A. J. Baltra-Ulloa, and A. Macdonald. 2020. “Principles for a Pedagogy of Unlearning.” Reflective Practice 21 (2): 183–197.

- McWilliam, E. 2008. “Unlearning How to Teach.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 45 (3): 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290802176147

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 2000. “Learning to Think Like an Adult.” In Learning as Transformation: A Theory-in-Progress, edited by J. Mezirow and Associates, 3–33. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Miller, D., L. Steier, and I. Le Breton-Miller. 2003. “Lost in Time: Intergenerational Succession, Change, and Failure in Family Business.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (4): 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00058-2

- Mitchell, J., B. Clayton, J. Hedberg, and N. Paine. 2003. Emerging Futures: Innovation in Teaching and Learning in VET. Deakin University Book. https://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30010201.

- OECD. 2018. “The Future of Education and Skills.” Education 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf (30-10-2023).

- Østergaard, E., G. Lieblein, T. A. Breland, and C. Francis. 2010. “Students Learning Agroecology: Phenomenon-Based Education for Responsible Action.” Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 16 (1): 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240903533053

- Rijksoverheid. 2023. “Secondary Vocational Education MBO.” https://www.government.nl/topics/secondary-vocational-education-mbo-and-tertiary-higher-education/secondary-vocational-education-mbo.

- Smith, P. J., and D. Blake. 2005. Facilitating Learning Through Effective Teaching: At a Glance. Adelaide: NCVER.

- Spivak, G. C. 1996. The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Hove, East Sussex, United Kingdom: Psychology Press.

- Sterling, S. 2011. “Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground.” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 5 (11): 17–33.

- Stokke, C. 2021. “Discourses of Colorblind Racism on an Internet Forum.” Journal of Multicultural Discourses 16 (1): 27–41.

- Stokstad, E. 2019. “Nitrogen Crisis from Jam-Packed Livestock Operations has ‘Paralyzed’ Dutch Economy.” Science. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/12/nitrogen-crisisjampacked-livestock-operations-has-paralyzed-dutch-economy.

- Stuckey, H. L., E. W. Taylor, and P. Cranton. 2013. “Developing a Survey of Transformative Learning Outcomes and Processes Based on Theoretical Principles.” Journal of Transformative Education 11 (4): 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614540335

- Tsang, E. W., and S. A. Zahra. 2008. “Organizational Unlearning.” Human Relations 61(10) (10): 1435–1462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708095710

- Tur Porres, G., D. Wildemeersch, and M. Simons. 2014. “Reflections on the Emancipatory Potential of Vocational Education and Training Practices: Freire and Rancière in Dialogue.” Studies in Continuing Education 36 (3): 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2014.904783

- Van Der Ploeg, J. D. 2020. Farmers’ Upheaval, Climate Crisis and Populism.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (3): 589–605.

- van Oers, L., G. Feola, H. Runhaar, and E. Moors. 2023. “Unlearning in Sustainability Transitions: Insight from Two Dutch Community-Supported Agriculture Farms.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 46:100693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100693

- Vermunt, D. A., N. Wojtynia, M. P. Hekkert, J. Van Dijk, R. Verburg, P. A. Verweij, M. Wassen, and H. Runhaar. 2022. “Five Mechanisms Blocking the Transition Towards ‘Nature-Inclusive’agriculture: A Systemic Analysis of Dutch Dairy Farming.” Agricultural Systems 195:103280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103280

- Wals, A. E., F. Caporali, P. Pace, B. Slee, N. Sriskandarajah, and M. Warren. 2004. “Education for Integrated Rural Development: Transformative Learning in a Complex and Uncertain World.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 10 (2): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13892240485300141

- Wittmayer, J. M., and N. Schäpke. 2014. “Action, Research and Participation: Roles of Researchers in Sustainability Transitions.” Sustainability Science 9 (4): 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0258-4

- Wuijts, S., H. F. M. W. van Rijswick, P. P. J. Driessen, and H. A. C. Runhaar. 2023. “Moving Forward to Achieve the Ambitions of the European Water Framework Directive: Lessons Learned from the Netherlands.” Journal of Environmental Management 333:117424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117424

Appendix 1

Box 1. Family-farm succession

Family-farm succession is a long-term, multi-dimensional, and multi-stakeholder process that comprises actions and events that may result in the gradual transfer of farm management and/or ownership from one family-business generation to another (Bloemen-Bekx, Lambrechts, and Van Gils Citation2021; Mazzola, Marchisio, and Astrachan Citation2008). Effective planning is an integral part of the succession process. However, the incumbents might be reluctant to let go and to give space to the next generation (Conway et al. Citation2017). Intergenerational succession is generally depicted as a staged three-step process: an individual is recognised as a potential successor, that individual forms a desire to take over the farm, and they then take over it effectively (Bertolozzi-Caredio et al. Citation2020; Fischer and Burton Citation2014). Fischer and Burton (Citation2014) contended that ‘farm succession is not predominantly a matter of “rational” choices made by individuals when reaching a critical point in the farm family life cycle, but rather a long-term process of developing a successor and farm simultaneously in such a way that their expectation of being a farmer matches their farm’ (433).

The entanglement of business and family relationships at the farm makes family-farm succession emotionally fraught and complex, with significant personal and commercial consequences (Bloemen-Bekx, Lambrechts, and Van Gils Citation2021; Daspit et al. Citation2016). It is for this reason that Gill (Citation2013) framed family-farm succession as a ‘complicated temporal process involving, as it does, the simultaneous consideration of past, present and future’ (p.77). Similarly, Miller, Steier, and Le Breton-Miller (Citation2003) proposed that successful succession means finding an appropriate relationship between the past and the present of an organisation. They suggested that it is problematic if ‘there is too strong an attachment to the past on the part of the successor, too wholesale a rejection of it, or an incongruous blending of past and present’ (514).