Abstract

Purpose: It is increasingly more common for Speech and Language Pathologists in Sweden to encounter individuals with dysarthria who speak a different language. The aim of the present pilot study was to develop and test a systematic method to be used in collaboration with an interpreter, for assessment of acquired dysarthria in people speaking a language not familiar to the Speech and Language Pathologist.

Methods: Seven participants, speaking standard Arabic, were assessed by a Swedish speaking Speech and Language Pathologist using this method and with help of a certified interpreter. The participants were also assessed with equivalent test items from the Swedish “Dysarthria assessment,” with instructions translated to Arabic, by a Speech and Language Pathologist speaking standard Arabic and the results were compared.

Results: There were no significant differences between the assessments by the Swedish speaking Speech and Language Pathologist and the Arabic speaking Speech and Language Pathologist in the domains “Respiration and phonation,” “Articulation,” “Listener Comprehension” and “Severity of dysarthria.” There was a significant difference between assessments in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function.” Intra- and inter-rater reliability was also calculated using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient and their 95% Confidence Interval. Intra-rater reliability was excellent and inter-rater reliability was very good.

Conclusion: The study indicates that a Speech and Language Pathologist, with help of an interpreter, can carry out an assessment of dysarthria in a language unknown to the Speech and Language Pathologist with results comparable to results from an assessment carried out by a Speech and Language Pathologist who speaks the foreign language.

Introduction

Changes in speech production induced by neurological disease are termed dysarthria and are often the first signs of underlying pathology [Citation1,Citation2]. Dysarthria is defined as a group of motor speech disorders caused by disturbances in the central and/or the peripheral nervous system that are involved in the muscular control of speech production [Citation3,Citation4]. There is no exact information of prevalence and incidence of acquired dysarthria in Sweden, but there are about 26,500 people every year who suffer from stroke [Citation5] and about 45% of these individuals also have dysarthria in the acute phase [Citation6]. About 29% of patients with stroke have a remaining dysarthria [Citation7]. In addition to this, it can be estimated that dysarthria also is present in between 50 and 90% of people living with progressive neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) as well as for people afflicted by head trauma [Citation8–10].

The dysarthrias can be differentially diagnosed based on symptom profiles and underlying disease or location of impairment [Citation11–13]. Diagnosis and rating of severity is often based on a clinical examination that includes assessment of respiration and phonation, oromotor and velopharyngeal function, articulation, as well as prosody and intelligibility [Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation14]. Perceptual assessment is considered the gold standard for clinical assessment of dysarthria [Citation3,Citation4]. Differential diagnosis of dysarthria is often based on both perceptual and acoustic analysis, the latter including quantifiable tasks such as alternate and sequential motion rates and maximum duration of sustained vowel or fricative. The assessment usually also includes more subjective ratings that may be less reliable than objective measures [Citation7,Citation15]. The use of standardized methods of assessment and analyses are preferable as they provide more objective information as a bases for the sometimes challenging process of differential diagnosis [Citation7]. The severity of dysarthria should always be assessed and be related to the dysarthric person’s complaints, serve as a baseline to compare with later assessments and help the Speech and Language Pathologist (SLP) to make decisions about treatment and/or compensatory strategies for the person with dysarthria [Citation3]. Severity of dysarthria can be measured both subjectively and objectively [Citation3]. The level of severity of dysarthria does however not always reflect the communication difficulties and restrictions in communicative participation perceived by the individual with dysarthria [Citation16].

In Sweden there are about 200 different languages spoken [Citation17]. In the year of 2012, there were 1.5 million people in Sweden who spoke another language than Swedish [Citation18]. The most commonly spoken languages, in addition to Swedish, are Finnish, Arabic, Serbo-Croatian, and Kurdish [Citation17]. In the end of 2017, there were 1.9 million people in Sweden who were born abroad [Citation19] and this population will continue to increase [Citation20]. This most likely means that people with other native languages than Swedish, presenting with dysarthria, will be referred to speech and language pathology (SLP) clinics in Sweden more frequently in coming years. In most cases, clinicians do not speak the language of the patient with a different native language. Several aspects of speech production, such as prosody, articulation and dialects are language-specific and may impact intelligibility [Citation14,Citation21,Citation22]. Those aspects are also affected when the speaker uses another language than their native language. Intonation is language dependent and tonal languages, unlike most European languages, use pitch change in syllables to differentiate between lexical meaning [Citation23]. This makes the assessment of dysarthria for an SLP with no knowledge of the native language of the patient more difficult. In Sweden, there are no standardized methods or materials available for a systematic assessment of dysarthria in speakers of another language than Swedish. To be able to carry out reliable assessments of changes in speech production in a foreign language, it is important to use well designed speech materials and standardized methods for analysis of the material [Citation24]. There can be methodological difficulties when speech materials have been created for a specific language but is used for assessment in another language [Citation25]. Speech material, e.g. used for assessment of articulation, needs to be based on the specific languages’ speech sounds. It is difficult to meet those demands in the clinic and it is therefore important to evaluate data with caution [Citation24]. In Sweden many SLPs use the Swedish Dysarthria assessment [Citation7], a standardized test, for assessment of dysarthria of Swedish-speaking individuals. No study has yet investigated what material SLPs in Sweden use when assessing dysarthria in another language than Swedish. An interpreter is needed to assist the SLP with carrying out an assessment of dysarthria if the SLP does not speak the language of the person to be tested. Studies point out the importance of using certified interpreters, that interpreters have a good knowledge of medical terminology, good translation ability and speak the same language or dialect as the caretaker [Citation26]. For some people who need an interpreter it is important that the interpreter has the same sex and share the same cultural background [Citation27]. It is also recommended that the clinician meet the interpreter prior to the assessment to explain professional terminology and how to administer the tests used for assessment [Citation28–30]. Difficulties with using an interpreter may arise if the interpreter lacks linguistic knowledge in one or both languages and if the patient does not have confidence in the interpreter [Citation26–28]. Problems can arise if the interpreter reduces information and summarizes utterances while translating [Citation31] and working with an interpreter can also be time consuming [Citation32].

Few cross-linguistic studies have been carried out to investigate what items in a dysarthria assessment could be used irrespective of the language tested. There is also insufficient information about what distinctive features different dysarthria types have in common in different languages and/or if the listener can evaluate an individual’s performance in a dysarthria assessment, having little or no knowledge of the specific language. Hartelius et al. [Citation33] showed acceptably high inter-judge reliability in a cross-language study of people with MS from Australia and Sweden. Ten Australian individuals and ten Swedish individuals with MS were all assessed perceptually, using 33 speech parameters, by two SLPs from each country. The participants read a passage in the respective languages. The parameters that both Australian and Swedish SLPs agreed on despite language were imprecise consonants, harshness and glottal fry, reduced speech rate, pitch level, and loudness. These are parameters typically consistent with spastic-ataxic dysarthria, a common type of dysarthria in speakers with MS. Dysphonia, measured both as overall severity and related to breathiness and roughness, of French and Italian dysphonic speakers were evaluated by French and Italian specialists in phoniatrics [Citation34]. Six specialists from each country assessed a total of 67 individuals, 27 Italian native speakers, and 48 French native speakers with different voice disorders. They read a text passage in French and Italian respectively. No significant differences between the listeners’ assessments was found, regardless of the language of the speakers. The specialists agreed on overall severity of dysphonia and breathiness despite which language the French and Italian listeners were assessing.

Tasks designed to assess oral-motor and phonatory function are typically included in clinical dysarthria examinations and these tasks are possible to carry out irrespective of language. The Swedish Dysarthria assessment includes several such tasks [Citation7]. Assessment of sustained production of a vowel (usually /a/) and a fricative, gives information on respiratory and phonatory function [Citation14,Citation35,Citation36]. Maximum phonation time (MPT) of sustained vowel is a reliable assessment to evaluate voice function [Citation37]. Range of motion, co-ordination and speed in lip-and tongue movements can give information about cranial nerve damage that would not be possible to identify if only speech items were used for assessment [Citation1,Citation2]. These tasks, revealing deviations in oromotor functions can also give additional information when differentiating between dysarthria types or when trying to determine what part of the nervous system is involved [Citation7,Citation13]. Alternating motion rates (AMR), like “pa-pa-pa” and sequential motion rates (SMR), pa-ta-ka,” are examples of other tasks adding information of value for differential diagnosis between some dysarthria types [Citation7,Citation14,Citation35,Citation36]. AMR and SMR should be performed as rapidly and steadily as possible and is a sensitive index of motor speech impairment [Citation38].

Other aspects of speech production typically included in dysarthria assessment such as articulation, intelligibility and prosody are harder to assess in a foreign language. Although most articulatory changes require knowledge of the target language, some deviations in articulation seem to be possible to identify in a language unknown to the listener, e.g. imprecise consonants [Citation33]. An explanation for this could be that some consonants are common in many languages. The consonant /m/ is represented in 94.2% of 415 languages included in UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database [Citation39]. The consonant /k/ is represented in 89.4% of 415 languages, /j/ in 83.8% and /p/ in 83.2% [Citation39]. Reduced intelligibility often has a major negative impact on communication and is important to include in dysarthria assessment [Citation7]. Intelligibility can be defined as how well a speaker’s acoustic signal can be recovered by a listener and is usually evaluated when the speaker is reading lists of word and/or sentences [Citation7,Citation40]. The words and sentences must be created in the specific language the dysarthric patient is speaking. Listener comprehension on the other hand, can be defined as the listener’s ability to understand the content and intention in the speaker’s message without consideration of accuracy of speech sounds and words [Citation7] and this measure may be more relevant to use if the purpose is to describe a speakers’ capability to communicate information in a context more generally [Citation40]. In conversation it is possible to evaluate many perceptual dimensions like prosody and paralinguistics as well as voice quality and communicative interaction and conversation is therefore a suitable speech task to use for estimation of listener comprehension [Citation36,Citation40]. The task does not require speech material created for a specific language. Prosody, including speech rate, intonation, stress and rhythm can be evaluated based on text reading or connected speech [Citation4,Citation7,Citation36]. Deviation of prosody is a common feature in dysarthric speech and has a negative impact on speech intelligibility and communication [Citation21]. Prosody is language specific and most aspects of prosody are difficult to assess in a foreign language [Citation21].

There are many languages spoken in Sweden and people speaking a language unfamiliar to the SLP are more frequently referred to SLPs for assessment of motor speech disorders. There are no available test material and standardized procedures for assessment of motor speech disorders in a language unfamiliar to the SLP. The aim of the present study was therefore to develop and standardize a systematic method to use when assessing dysarthria in a language unfamiliar to the SLP. To test the method assessments of individuals with dysarthria speaking a different native language than the SLP were completed using this method with the aid of an interpreter and the results were compared with assessments of the same individuals completed by an SLP speaking the same language as the participants. The research question was:

Is a Swedish speaking SLP’s assessment of dysarthria in a person speaking a foreign language, completed with the aid of an interpreter and using a systematic method comparable with an assessment carried out by an SLP who speak the same foreign language?

Materials and method

Participants

Patients who spoke and understood modern standard Arabic [Citation41,Citation42] and had been referred for assessment of dysarthria to an SLP in a rehabilitation team were asked to participate after they were given verbal and written information in Arabic about the study. Verbal and written informed consent was given in Arabic by the participants who were included in the study. Inclusion criteria was that the participant could speak and understand modern standard Arabic and had been referred for assessment of dysarthria. Exclusion criteria were visual and hearing impairment that could not be compensated for and a known cognitive impairment.

Seven consecutive participants were included in the study, one female and six males, with a mean age of 56.3 (SD = 7.5) age range between 42 and 63 years. For more information about participants, see .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Participant 3 did not get a dysarthria diagnosis, but had strained/strangled and unstable voice quality during production of sustained /a/ and difficulties with alternating lateral tongue movements. Participant 6 had a mild to moderate unilateral upper motor neuron dysarthria after stroke when referred to the rehabilitation team and the SLP. The participant recovered quickly and at the time of the assessment of dysarthria only remaining symptoms were unstable voice quality, vocal fry and breathiness in sustained vowel and slow and uncoordinated tongue movements. The participant was not diagnosed with dysarthria. See Supplementary Table S1 for details of qualitative descriptions of all participants.

Test materials used for dysarthria assessment

In this study, assessment of Arabic-speaking participants were done in two different ways using two different protocols. Arabic participants with dysarthria were assessed by a Swedish SLP, partly with the assistance of an interpreter, using the newly developed standardized method based on the Swedish Dysarthria assessment [Citation7]. The Arabic speaking participants were also assessed by an Arabic speaking SLP using the Dysarthria assessment translated and adapted to Arabic.

The new protocol developed for assessment by the Swedish SLP is inspired by the Dysarthria assessment by Hartelius [Citation7]. The Dysarthria assessment is a comprehensive standardized clinical test of dysarthria based on the ICF-framework, i.e. assessment of both structure and function, activity and participation are included. The first part of the test is used for assessment of different aspects of structure and function related to speech production and includes the domains “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” and “Articulation.” The second part of the test is used for assessment of different aspects of speech activity and includes assessment of prosody and intelligibility [Citation7]. The third part of the test consists of a questionnaire for assessment of self-perceived speech and communication problems and restrictions in communicative participation. An ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 3 is used to rate each test items, where 0 corresponds to no or insignificant deviation of speech/function and 3 corresponds to severe deviation or absence of function. Both quantitative results of the test and qualitative descriptions e.g. of deviations in prosody and voice quality help the SLP to differentially diagnose and rate level of severity of dysarthria.

The new assessment protocol

A protocol was developed for assessment of speakers of a foreign language by a Swedish SLP not speaking the same language. The protocol included assessment of the domains “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” “Articulation” and “Prosody.” In addition, assessment of “Severity of dysarthria” and “Listener comprehension” in spontaneous speech were also part of the protocol. Questions regarding patient history were included as well.

This protocol was intended to be used by the Swedish speaking SLP together with the interpreter. The protocol included test items possible for the SLP to evaluate without the interpreter’s help, although the interpreter was needed to give instructions on how to perform the tasks. The protocol also included items that were rated by the interpreter, namely ratings of prosody and listener comprehension.

Ratings of all test items were made on a four-graded scale. The same scale was used for ratings of listener comprehension (0 = “no difficulties understanding the speech,” 1 =“some difficulties understanding the speech,” 2 = “moderate difficulties understanding the speech” and 3 = “severe difficulties understanding the speech”) and is the same scale as in the Swedish Dysarthria assessment [Citation7] to be able to compare the assessments between the Swedish speaking SLP, the interpreter and the Arabic speaking SLP. See Supplementary Table S2 for more detail.

Respiration and phonation

Maximum duration of sustained vowel /a/ and fricative /s/ were assessed by the Swedish SLP to obtain information about respiratory and phonatory capacity [Citation14,Citation21,Citation35,Citation36]. The test items could also be used to perceptually evaluate control of loudness and pitch, vocal stability and voice quality in sustained production of /a/ [Citation14,Citation36,Citation37]. Abruptly increasing intensity on /a/ was evaluated for information about ability to contract the abdominal wall to achieve vocal fold adduction and coughing for rapid and powerful vocal fold adduction, both needed in speech production [Citation7,Citation43]. Abrupt increasing intensity on /s/ was evaluated for ability to achieve a rapid and powerful expiratory pressure variation, also needed in speech production [Citation7].

Oromotor and velopharyngeal function

Test items included in assessment of “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” possible to evaluate without knowledge of the language spoken, were assessments of range of motion, co-ordination and speed of lip-and tongue movements. As mentioned earlier, these tasks can give information about cranial nerve damage and be useful for differential diagnosis in assessment of motor speech disorders [Citation1,Citation2]. AMR (“ba-ba-ba,” “ta-ta-ta” and “ka-ka-ka”) and SMR (“ba-ta-ka”) were also included as they can contribute information useful for differential diagnosis in assessment of motor speech disorders [Citation4,Citation7,Citation14,Citation36,Citation37,Citation43,Citation44]. In most languages the speech sound /p/ is used in the initial AMR repetition “pa-pa” and in SMR “pa-ta-ka.” In languages where /p/ is not represented, as in Arabic, the voiced /b/ can be used instead [Citation45].

Articulation

To investigate if the Swedish SLP, without help from the interpreter, could identify articulatory impairment, syllable repetitions with the most frequent consonants in the worlds languages [Citation39] were combined with the three most frequent vowels [a], [i], and [u] [Citation46]. Places of articulation included to evaluate articulation were bilabials, labiodentals, dentals, fricatives, palatals and velars. The purpose of using syllables was to examine if it is possible to distinguish if articulation deviates or not in a foreign language without need of creating speech material in the language tested.

Prosody

Prosody was evaluated and described by the interpreter from a speech sample where the participant was asked to talk about something he/she likes to do or is interested in. The interpreter was informed that prosody includes speech rate, lengths of phrases, pauses, stress, and intonation. Those terms were explained to the interpreter in a manner understandable for a person not familiar with terminology used by an SLP. The interpreter could make a note in the protocol if she could perceive a deviation in any of the following aspects; speech rate, length of phrases, pauses, stress and intonation.

Listener comprehension

As defined in the introduction of this paper, listener comprehension was the outcome measure used in the newly developed protocol. The participant’s speech was rated by the interpreter when listening to the participant asked to talk about something he/she liked to do and answering questions about medical history. Listener comprehension was also rated by a significant other. The significant other’s evaluation was based on daily communication between the participant and significant other. The participant’s own estimation of how much other people could understand his/her speech, was also included.

Severity of dysarthria

Rating of severity of the speech impairment was included and judged by the SLP, based on the results of assessment of “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” “Articulation” as well as result on the interpreter’s evaluation of “Listener comprehension” and overall impression of the participant’s speech.

The Swedish dysarthria assessment translated and adapted to Arabic

Instructions from the Swedish Dysarthria test were translated to Arabic by the Arabic speaking SLP. A person speaking both Swedish and Arabic translated the instructions back to Swedish and the Arabic speaking SLP then translated back to Arabic with some corrections where needed.

The Arabic speaking SLP assessed the participants in the study with equivalent test items from the same domains as the Swedish speaking SLP, using the translated version of the Swedish Dysarthria assessment [Citation7]. The Swedish test contains several test items in the domains “Respiration and phonation” and “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” which are typically included in dysarthria testing also in other languages [Citation14,Citation21,Citation35,Citation36,Citation43,Citation44]. Articulation is evaluated in the Swedish Dysarthria assessment by assessing the patient’s reading of phonetically balanced sentences. Corresponding sentences in Arabic were created for evaluation of bilabials, labiodentals, dentals, palatals and velars to be compared with the syllable repetitions with same articulation places used by the Swedish speaking SLP when assessing articulation. Prosody was also evaluated by the Arabic speaking SLP, using the same task as the Swedish SLP, i.e. a speech sample where the participant was asked to talk about something he/she likes to do or is interested in. The Arabic speaking SLP noted in the protocol if there were any deviations in descriptive features of speech rate, length of phrases, pauses, stress and intonation. The Arabic speaking SLP used connected speech for estimating listener comprehension. Intelligibility evaluated by reading words and sentences were excluded as well as text reading since those test items could not be compared with the test items used by the Swedish speaking SLP and materials for assessing intelligibility were not available in Arabic. Rating of severity of the speech impairment was included and judged by the Arabic speaking SLP, based on the results of assessment of “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” “Articulation” “Listener comprehension” as well as the SLP’s overall impression of how deviant or not the participants speech was.

Procedure

When the new protocol was developed to be used for assessment in a foreign language by the Swedish SLP, patients with dysarthria speaking another native language, referred to an SLP for assessment of dysarthria, were asked about their opinion of the items and the assessment procedure. The protocol was also reviewed by experienced SLPs who confirmed that the items were suitable to the purpose of the study, i.e. dysarthria diagnostics. No changes of test items or questions were needed after this procedure.

Before assessments were initiated, the Swedish SLP and the Arabic speaking SLP completed a training session during which ratings of dysarthria assessments were made from previous video recordings of dysarthria testing. If there were different opinions in judgements, the results from the assessments were discussed until consensus was reached.

The participants were assessed in Arabic with the new protocol by the Swedish speaking SLP with help of a certified interpreter. The same interpreter participated in all sessions. During the testing, the interpreter used the same protocol as the Swedish speaking SLP to be able to make notes if the interpreter perceived the participants speech as deviant. The testing took place either in the participants’ home or in a clinic setting. Audio recording were done using a Tascam DR-07MKII.

All participants were tested by the Swedish speaking SLP before they were tested by the Arabic speaking SLP. This was necessary as the results from the Swedish SLP with the interpreter had to be documented in the participants’ medical records and there was a risk of a drop-out after the first assessment. The Arabic speaking SLP was blinded to the results of the Swedish speaking assessments.

Testing procedures were the same during both testing sessions and the instructions from the manual of the Swedish Dysarthria assessment were followed. Instructions were to repeat the items in the domains “Respiration and phonation” and “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” three times. The SLP was instructed to rate the best of the three attempts. When executing the non-verbal oromotor tests, participants were asked to perform the movement for at least 5 seconds so the SLP can judge if there are signs of fatigue, reduced range, tremor and incoordination of muscular movements. Number of seconds a participant could sustain /a/ and /s/ was noted and for AMR and SMR, the syllables per second was counted. In the domain “Articulation,” assessed by the Swedish speaking SLP, the participants were asked to repeat each syllable three times and the SLP rated the best of the three attempts.

Time between the two assessments by the Swedish speaking SLP and the Arabic speaking SLP for each participant was between 1 and 2½ weeks. The assessments by the Swedish speaking SLP together with the interpreter took between 45 minutes and 60 minutes each to complete. The assessments by the Arabic speaking SLP were completed in between 30 and 45 minutes each.

Intra- and inter-rater reliability

Since there were no video recordings of the assessments, only test items that could be assessed with auditory-perceptual ratings and did not require knowledge of the Arabic language, were used for calculation of intra-rater and inter-rater reliability. For the domain “Respiration and phonation,” the items were duration of maximum sustained vowel /a/ and fricative /s/, increasing intensity on /a/ and /s/ and coughing. For the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” the items smack with the lips, AMR and SMR were used for assessment. Nine syllable repetitions were used for evaluation of the domain “Articulation.” Sound files including these items were constructed and then coded. Four SLPs with experience of assessing dysarthria, including the author, rated all seven sound files for inter-rater reliability independently in their workplaces. They could listen as many times as they needed to each sound file.

The Swedish-speaking SLP rated items from sound files on two occasions with about 10 weeks in between for calculation of intra-rater assessment.

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and MS Excel was used for calculations. The level of the alpha-value was set at 0.05. Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and their 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for intra-rater reliability were calculated using 2-way mixed-effect model, single measurement, absolute agreement. ICC and their 95% CI for inter-rater reliability were calculated using 2-way random-effect model, single measurement, absolute agreement. For ICC, values less than 0.5 were considered poor, between 0.5 and 0.75 moderate, between 0.75 and 0.90 were considered good and greater than 0.90 excellent as defined by Koo and Li [Citation47]. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted to compare if there were any differences between the assessments of the Swedish speaking SLP with and without interpreter and the Arabic speaking SLPs assessments of the domains “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” “Articulation,” as well as for “Listener comprehension” and “Severity of dysarthria.” The expected results were to find no significant differences between the assessments. A Friedman test was conducted to compare if there were any differences between ratings of listener comprehension between the interpreter, the significant other, the participant and the Arabic-speaking SLP. The expected result was to find no significant differences between the ratings. Due to the difference of the Swedish speaking SLP’s and Arabic SLP’s evaluations of the participants result in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” a Spearman’s rho was calculated for each item in this domain.

There were two missing data in the assessments. One item in one patient’s testing was missed by the test leader and one patient asked for permission to leave out one item due to ongoing dental treatment. The two missing items were imputed by calculating the mean from the results of the specific patients’ results in the specific dimension where data was missing.

Ethical considerations

The present study has been approved by the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2017/701-3). Verbal and written informed consent was obtained in Arabic, with help of an interpreter, from all participants. The participants were informed that they could withdraw their participation at any time. There was a risk that the duplicated testing could be tiresome for the participants, however this also meant that they got a more thorough assessment. Protocols and sound files were coded.

Results

Intra-rater reliability of the ratings of the seven participants' performance of the items in the domains “Respiration and phonation,” Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” and “Articulation” was calculated using ICC and their 95% CI. The intra-rater reliability was excellent with an ICC of 0.970 (CI 95% 0.958 to 0.979).

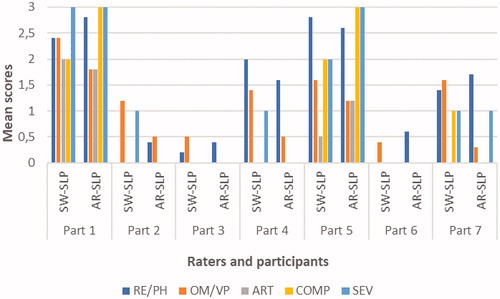

Inter-rater reliability of the ratings of the seven participants' performance of the items in the domains “Respiration and phonation,” Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” and “Articulation” was calculated using ICC and their 95% CI. Inter-rater reliability was considered good with an ICC of 0.805 (CI 95% 0.756 to 0.849). See for mean scores of the four SLP’s evaluations of the seven participants results in the domains “Respiration and phonation,” “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” and “Articulation.”

Table 2. The four raters’ evaluations, used when calculating ICC, of the seven participants’ results in the domains Respiration and phonation, Oromotor and velopharyngeal function and Articulation, presented as mean scores.

Comparisons between assessments by the Swedish speaking SLP and the Arabic speaking SLP

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted to compare results form the assessments by the Swedish speaking SLP together with the interpreter and the Arabic speaking SLP’s assessments. Results indicated no significant difference of the scores in the domains “Respiration and phonation” (Z = 57.00, p < .396), “Articulation” (Z = 14.00, p < .414), “Listener comprehension” (Z = 4.00, p < .564) and “Severity of dysarthria” (Z = 5.00, p < 1.000). There was a significant difference between the scores of the Swedish speaking SLP and the Arabic speaking SLP in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” (Z = 14.50, p < .001).

A Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was run for each of the eleven items included in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function” to find out where there were differences in the ratings. The output indicated positive correlations and statistically significant results between four of the items in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function.” The four items were SMR (rs(7) = 0.877, p < .01), AMR “ta-ta-ta” (rs(7) = 0.835, p < .05), AMR “ka-ka-ka” (rs(7) = 0.813, p < .05) and to stretch the tongue forward (rs(7) = 0.837, p < .05).

Mean values of ratings by the Swedish speaking SLP and Arabic speaking SLP of the domains “Respiration and phonation,” Oromotor and velopharyngeal function,” “Articulation,” “Listener comprehension” and “Severity of dysarthria” for the seven participants are presented in .

Figure 1. Mean ratings by the Swedish SLP (SW-SLP) and the Arabic SLP (AR-SLP) of the domains Respiration and phonation (RE/PH), Oromotor and velopharyngeal function (OM/VP), Articulation (ART), Listener comprehension (COMP), and Severity of dysarthria (SEV) for the seven participants (Part).

Listener comprehension

A Friedman test was conducted to calculate if there was a significant difference of ratings of listener comprehension between the interpreter, the significant other, the participant and the Arabic speaking SLP. The result indicated no significant difference χ2 (3) = 0.840, p = .896.

Prosody

The interpreter and the Arabic speaking SLP agreed in 67% of the evaluations of descriptive features in the domain “Prosody” which included speech rate, length of phrases, pauses and if palilalia was present or not. They agreed least in the features stress and intonation. See .

Table 3. Swedish speaking SLP’s/interpreter’s (SW-SLP) and Arabic speaking SLP’s (AR-SLP) descriptive features of participants’ prosody. Information about speech rate, lenght of phrases, pauses, stress, intonation and if the participant had palilalia or not is included.

Discussion

This pilot study indicates that results of a dysarthria assessment by an SLP who does not speak the native language of the patient but performs the assessment according to a systematic method in collaboration with an interpreter are comparable to results of the dysarthria assessment of an SLP who speaks the language. The systematic method proposed does not include using any written material for the patient to read, like words and sentences for assessing articulation and text reading for evaluation of prosody, and therefore it should be possible to generalize the method to other languages as well. One needs to be aware however that some consonants in syllable repetitions may have to be adjusted depending on the language in question. The proposed method can also be used for assessments of dysarthria in people who are illiterate. It is important to point out that an interpreter is needed to acquire information about the patients’ medical histories, to give instructions on how to perform test items and to give valuable information to the SLP about language-specific features and listener comprehension. The interpreter in this study was not always able to describe exactly what kind of deviations in speech that were perceptually observable. However, when in dialog with the SLP, this could in most cases be explained in more detail and described using terminology appropriate for dysarthria with some clarifying questions to the interpreter.

A significant difference of the assessments of the Swedish speaking SLP and Arabic speaking SLP was found in the domain “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function.” The reason for this was a misinterpretation of the instructions regarding this part in the testing by the Arabic speaking SLP and not due to difficulties related to testing and evaluating results of the performance of the items in this domain.

The Swedish SLP was able, without the interpreter’s help, to distinguish between the participants with no impairment of articulation and participants with articulatory impairment. The Swedish SLP was able to identify places of articulation that were deviant in several cases when assessing the participants syllable repetitions. Imprecise consonants are a common feature in many dysarthria types and in different languages [Citation33,Citation48,Citation49]. For consonants common in many languages [Citation39] and familiar to the listener, it seems possible for an SLP with no knowledge of a language to evaluate if the articulation is affected or not. There are speech sounds in Arabic, e g pharyngeal and glottal sounds, that are not represented in the Swedish language and therefore not possible to evaluate if the SLP does not speak Arabic. One can assume that this is the case in several languages and it is probably not possible for an SLP without knowledge of the foreign language in question to be able to make distinctions of deviations of speech sounds, not represented in the SLP’s own language.

The results in the pilot study indicate that it is possible to perceptually assess several features of the dysarthria, such as changes of respiration and phonation, articulation and listener comprehension, without knowledge of the specific language, which has also been shown in previous research [Citation33,Citation48–50]. The Swedish speaking SLP could, without knowledge of the Arabic language, perceptually perceive some common speech features characteristics of different dysarthria types such as in ALS, Parkinson’s disease and MS. See Supplementary Table S1 for more details. Many features of motor speech production are universal across languages [Citation22] and could, to some degree, explain the Swedish speaking SLP’s ability to capture some deviant features in the participants’ speech. On the other hand, studies investigating what specific features in a language that may be affected differently in different type of dysarthria across languages are lacking [Citation22].

There was not satisfactory agreement between the Arabic speaking SLPs and the interpreter’s assessments of stress in four of the participants as well as in intonation in the domain “Prosody.” A reason for this could be that the Swedish SLP did not explain the terms in such a way that the interpreter understood how to evaluate them. It could also be the interpreter’s tolerance to deviations in speech. An interpreter usually does not listen to speech features since the purpose of their work is to translate what is said.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to this study. It should be noted that only one Swedish speaking SLP, one Arabic speaking SLP and one interpreter were included. There were also very few participants with dysarthria, and this increased the risk of the results not being representative for Arabic speaking people with dysarthria. The low number of participants of course also limits the extent to which findings can be generalized to a larger population. The statistical power is reduced with few participants in combination with use of a scale with few scale steps. There were no normative data available for Arabic speaking people for the test items in the domains of “Respiration and phonation” and “Oromotor and velopharyngeal function.” For AMR and SMR, most languages where normative data are available, like English, Hebrew and Greece, only small differences are found between these languages’ norms for AMR and SMR, compared with Swedish norms [Citation7,Citation51]. In Farsi though, as an example, normative data for SMR is higher than Swedish norms [Citation51].

Six of the participants already had neurological diagnoses when tested and this could have helped the Swedish SLPs to pay attention to specific perceptual features, characteristic for dysarthria types of those diagnoses.

Clinical implications

This pilot study of the suggested method indicates that it may be possible to use the proposed systematic assessment of people with acquired motor speech disorders, speaking a language unfamiliar to the SLP but it needs to be evaluated in more detail. The pilot study is promising in terms of possibilities to administer more equal treatment and care to the growing population who speak languages unfamiliar to the SLP and are referred to the clinic for assessment of dysarthria. Systematic assessments in languages unknown to the SLP could lead to increasing knowledge and be helpful in assessment of neurological diseases and differential diagnoses of patients speaking other languages than Swedish.

Future studies

It would be of interest to investigate the use of the proposed method in other languages than Arabic to investigate to what degree the method can be generalized. Languages including different speech sounds and variations in prosody compared to the Arabic language, as a tonal language, could be of special interest. It would also be of interest to investigate if articulatory deviations are detectable in other languages than Arabic. This could also contribute to decisions about which syllables in the protocol’s domain “Articulation” are needed for evaluation and which syllables could be removed. The difficulties for the interpreter in this study to evaluate prosody implicates the need of discussions before and after the assessments together with the interpreter for the SLP to make sure that the interpreter has understood the terms enough to make a reliable assessment in this domain. It could also be of interest to investigate if it is possible to distinguish between mild, moderate and severe dysarthria in other languages than Arabic. A larger study group, more listeners and systematic comparisons of all aspects are needed.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor change. This change do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (499.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We want to thank Nada El-Haj Ibrahim, the SLP who translated the needed material to Arabic and executed the assessments in Arabic. Thank you also to our colleagues Åsa Lindström, Marika Schütz and Theodor Ricklefs who helped with the assessments of interrater reliability.

References

- Ball LJ, Willis A, Beukelman DR. A protocol for identification of early bulbar signs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191:47–53.

- Rong P, Yunusova Y, Wang J. Predicting early bulbar decline in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a speech subsystem approach. Behav Neurosci. 2015;2015:1–11.

- Duffy JR. Motor speech disorders: substrates, differential diagnosis and management. 3rd ed. St Louis (MI): Elsevier Mosby; 2013.

- Darley FL, Aronson AE, Brown JR. Motor speech signs in neurologic disease. Med Clin North Am. 1968;52:835–844.

- Socialstyrelsen (Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare). Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid stroke (National guidelines for stroke care). Stockholm (Sweden): Socialstyrelsen; 2018.

- Lohmander A, McAllister A, Hansson K, et al. Kommunikations–och sväljstörningar genom hela livet - ett logopediskt ståndpunktsdokument, 2017. [Communication and swallowing disorders through the life span - a speech and language pathology position paper, 2017]. [cited 2018 Sept 30]. Available from: https://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1144268/FULLTEXT03.pdf

- Hartelius L. Dysartri-bedömning och intervention [Dysarthria – assessment and intervention]. Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2015 (Swedish).

- Hartelius L, Runmarker B, Andersen O. Prevalence and characteristics of dysarthria in a multple-sclerosis incidence cohort: relation to neurological data. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2000;52:160–177.

- Schalling E, Johansson K, Hartelius L. Speech and communication changes reported by people with Parkinson’s disease. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2017;69:131–141.

- Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering. Rehabiliteringsinsatser för personer med traumatisk hjärnskada. [Swedish agency for health technology assessment and assessment of social services. Rehabilitation of traumatic brain injury]. Stockholm; 2018. [cited 2018 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.sbu.se/sv/pagaende-projekt/rehabiliteringsinsatser-for-personer-med-traumatisk-hjarnskada/

- Darley FL, Aronson AE, Brown JR. Differential diagnostic patterns of dysarthria. J Speech Hear Res. 1969;12:246–269.

- Darley FD, Aronson AE, Brown JR. Clusters of deviant speech dimensions in the dysarthrias. J Speech Hear Res. 1969;12:462–496.

- Darley FL, Brown JR, Goldstein NP. Dysarthria in multiple sclerosis. J Speech Hear Res. 1972;15:229–245.

- Miller N, Mshana G, Msuya O. Assessment of speech in neurological disorders: development of a Swahili screening test. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2012;59:27–33.

- Knuijt S, Kalf JG, van Engelen BGM, et al. The Radbury dysarthria assessment: development and clinimetric evaluation. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2017;69:143–153.

- Hartelius L, Elmberg M, Holm R, et al. Living with dysarthria: evaluations of a self-report questionnaire. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2008;60:11–19.

- Institutet för språk och folkminnen [The Institute for language and folklore]. Uppsala: Culture department; 2006. [cited 2018 Apr 8]. Available from: http://www.sprakochfolkminnen.se/om-oss/for-dig-i-skolan/sprak-for-dig-i-skolan/spraken-i-sverige.html

- Parkvall M. Sveriges språk i siffror: vilka språk talas och av hur många? [Swedens languages in numbers: which languages are spoken and by how many?] Stockholm (Sweden): Morfem; 2016. Swedish.

- Statistiska Centralbyrån [Statistics Sweden]. Stockholm: 2018. [cited 2018 July 14]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/in-och-utvandring/

- Statistiska Centralbyrån [Statistics Sweden]. Stockholm: 2016. [cited 2018. July 14]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/Statistik/BE/BE0401/2016I60/BE0401_2016I60_SM_BE18SM1601.pdf

- Pascoe M, Norman V. Contextually relevant resources in speech-language therapy and audiology in South Africa-are there any? S Afr J Commun Disord. 2011;58:2–5.

- Pinto S, Chan A, Guimarães I, et al. A cross-linguistic perspective to the study of dysarthria in Parkinson disease. J Phon. 2017;64:155–167.

- Ma JKY, Ciocca V, Whitehill TL. The effect of intonation on Cantonese lexical tones. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;120:3978–3987.

- Lohmander A, Lundeborg I, Persson C. SVANTE - the Swedish articulation and nasality test-normative data and a minimum standard set for cross-linguistic comparison. Clin Linguist Phon. 2017;31:137–154.

- Hutters B, Henningsson G. Speech outcome following treatment in cross-linguist cleft palate studies: methodological implications. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;4:544–549.

- Krupic F, Hellström M, Biscevic M, et al. Difficulties in using interpreters in clinical encounters as experienced by immigrants living in Sweden. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:1721–1728.

- Hadziabdic E, Albin B, Hjelm K. Arabic-speaking migrants’ attitudes, opinions, preferences and past experiences concerning the use of interpreter in healthcare: a postal cross-sectional survey. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:71.

- Langdon HW, Quintar-Saranella R. Roles and responsibilities of the interpreter in interactions with speech-language pathologist, parents and students. Semin Speech Lang. 2003;3:235–244.

- Tribe R, Thompson K. Developing guidelines on working with interpreters in mental health: opening up an international dialogue?. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2011;4:81–90.

- Kambanaros M, van Steenbrugge W. Interpreter and language assessment: confrontation naming and interpreting. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2004;6:247–252.

- Sleptsova M, Weber H, Schöpf AC, et al. Using interpreters in medical consultations: what is said and what is translated-a descriptive analysis using RIAS. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:1667–1671.

- Fatahi N, Hellström M, Skott C, et al. General practitioners’ views on consultations with interpreters: a triad situation with complex issues. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:40–45.

- Hartelius L, Theodoros D, Cahill L, et al. Comparability of perceptual analysis of speech characteristics in Australian and Swedish speakers with multiple sclerosis. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2003;55:177–188.

- Ghio A, Weisz F, Baracca G, et al. Is the perception of voice quality language-dependant? A comparison of French and Italian listeners and dysphonic speakers. 12th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association INTERSPEECH]; 2011 Aug 27–31; Florence, Italy.

- Ackermann H, Ziegler W. Cerebellar voice tremor: an acoustic analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:74–76.

- Kent RD, Kent JF. Task-based profiles of the dysarthrias. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2000;52:48–53.

- Speyer K, Yorkston KM, Duffy JR. Behavioral management of respiratory/phonatory dysfunction from dysarthria: a flowchart for guidance in clinical decision-making. J Med Speech Lang Pathol. 2003;11:XXXIX–XXLXI.

- Ziegler W. Task-related factors in oral motor control: speech and oral diadochokinesis in dysarthria and apraxia of speech. Brain Lang. 2002;80:556–575.

- UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database [Internet]. Available from: http://www.web.phonetic.uni-frankfurt.de/upsid_info.html

- Bunton K, Kent RD, Duffy JR, et al. Listener agreement for auditory-perceptual ratings of dysarthria. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:1481–1496.

- Aljasser F, Vitevitch M. A web-based interface to calculate phonotactic probability for words an nonwords in modern standard Arabic. Behav Res. 2018;50:313–322.

- Boudelaa S, Marslen-Wilson WD. Morphological structure in the Arabic mental lexicon: parallels between standard and dialectal Arabic. Lang Cogn Process. 2013;28:1453–1473.

- Cardoso R, Guimarães I, Santos H, et al. Frenchay dysarthria assessment (fda-2) in Parkinson’s disease: cross-cultural adaption and psychometric properties of the European Portuguese version. J Neurol. 2017;264:21–31.

- Knuijt S, Kalf J, Van Engelen B, et al. Reference values of maximum performance tests of speech production. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2017;21:56–64.

- Abou-Elsaad T, Baz H, El-Banna M. Developing an articulation test for Arabic-speaking school-age children. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2009;61:275–282.

- Lindblom B. Phonetic universals in vowel systems. In: Ohala JJ, Jaeger JJ, editors. Experimental phonology. Orlando (FL): Academic Press; 1986. p. 13–44.

- Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficient for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–163.

- Whitehill TL, Ma JK, Lee AS. Perceptual characteristics of Cantonese hypokinetic dysarthria. Clin Linguist Phon. 2003;17:265–272.

- Chakraborty N, Roy T, Hazra A, et al. Dysarthric Bengali speech: a neurolinguistic study. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:268–272.

- Kent RD, Kent JF, Duffy JR, et al. Ataxic dysarthria. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000;43:1275–1289.

- Icht M, Ben-David BM. Oral-diadochokinesis rates across languages: English and Hebrew norms. J Commun Disord. 2014;48:27–37.