Abstract

This paper uses a policy design perspective with which to examine the formulation of programmes that are based on the concept of co-production. In doing so, the paper reviews essential literature on policy design and co-production to identify that a limited focus on outcomes and specifically how behavioural change can make these outcomes sustainable represents a major gap in the current discussion of co-production. We firstly argue that in designing programmes involving co-production, outcomes need to be considered at the initial design stages where broad policy objectives are being defined. Secondly, we argue that for these outcomes to be sustainable, behavioural change on the part of policy targets needs to be an important objective of a coproduction programme. To illustrate our point, we use the example of rural sanitation programmes from three developing countries to specifically demonstrate how the absence or inclusion of behavioural change considerations in the early phases of policy design can elicit different levels of success in achieving desired policy outcomes.

Introduction: co-production and policy design

The term ‘co-production’ has emerged over the last few decades as a concept that generally indicates greater and an active civic community or ‘end-user’ or ‘policy target’ participation in social policy processes (Pollitt & Hupe, Citation2011, Voorberg, Bekkers, & Tummers, Citation2014). Situated within the broad reform trend of New Public Governance (NPG), co-production embodies the contemporary emphasis on increased citizen participation in the policy process and a move away from the bifurcation between traditional public administration and market-oriented emphasis of public management (Osborne, Citation2010; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011).

While the literature on policy co-production has concentrated on the participation of civic society in the delivery of services, it rarely touches on the role that these participants play in the design and continuity of the desired outcomes of those services. That is, while the academic discussion of the term focuses on community involvement in the implementation or delivery of a defined service or programme, the role of the community in sustaining that service once it has been produced has not received equal attention.

This distinction relates to whether and how actively citizens are involved in the core service delivery process, as well as the maintenance of the flow of benefits that emanate from that co-produced service, well after it has been implemented. Brandsen and Honingh (Citation2015) have made an important analytical start in this direction by identifying ‘two variables along which different types of co-production can be distinguished: the extent to which citizens design services delivered to them and the proximity of co-production to the primary process’ (p. 7), allowing for types of co-production to be distinguished based on whether communities are involved in the design and/or the implementation of the service under consideration. Furthermore, some authors have suggested that ‘co-production’ as a term should refer to the involvement of communities in the implementation of a policy programme while ‘co-creation’ should indicate their input in its formulation (Pestoff, Brandsen, & Verschuere, Citation2013).

However, much remains to be said about what community behaviours need to be specifically addressed at the initial, design stages of any policy dealing with co-production, which can have direct effects on the sustainability of the desired results. In employing a policy design perspective, the depiction of co-production in this paper supports an analytical extension of the concept beyond the co-production of services to the co-production of outcomes and the sustainability of those outcomes.

With a focus on lessons from rural sanitation solutions in developing countries that have succeeded in sustaining the outcomes of co-production to various degrees, this paper argues that behavioural change considerations must be incorporated into the design of policy programmes that adopt co-production. In doing so, the paper first reviews essential literature on policy design and co-production to identify that a limited focus on outcomes and behavioural change represents a major gap in the current discussion of co-production. We argue that in formulating programmes involving co-production, a consideration of outcomes needs to be included at the initial design stages where broad policy objectives are being defined. Secondly, we use the example of rural sanitation programmes from three developing countries as critical cases (Yin, Citation1994) of co-production policy to specifically illustrate how the absence or inclusion of behavioural change considerations can elicit different levels of success in achieving desired policy outcomes. In using these cases, therefore, we argue that the sustainability of co-production depends on whether and to what extent behavioural change is considered during policy design. The paper concludes by drawing lessons from the case of rural sanitation and the prospects of future co-production research.

A policy design approach: co-production as a policy instrument preference and behavioural change as a policy objective

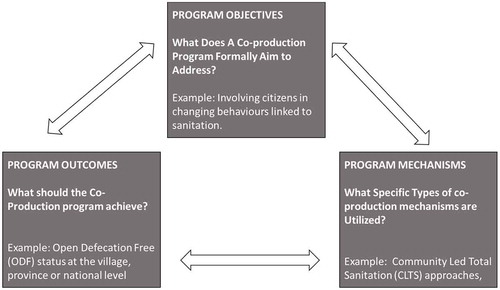

Defining policy goals and proposing means to meet these goals are the cornerstones of policy design and purposive policy formulation by governments (Gunningham & Sinclair, Citation1999; Howlett & Lejano, Citation2013; Howlett, Mukherjee, & Rayner, Citation2014). Policy design takes place in the policy formulation stages of the policy process once an issue has already been raised on the government’s agenda. It is the way in which policy formulation processes create a policy programme or instrument to meet a stated policy goal. Here, it is important to recognise (see ) that policies are composed of several elements, distinguishing between abstract or theoretical/conceptual goals, specific programme content or objectives and operational settings or calibrations of instruments (Hall, Citation1993; Howlett & Cashore, Citation2007, 2009).

Each of these component elements is conceived and created by policy-makers in the course of the policy-making process. Some components of a policy are very abstract and exist at the level of general ideas and concepts about policy goals and appropriate types of policy tools which can be used to achieve them. Others are more concrete and specific and directly affect administrative practice on the ground. Policy programmes, such as those explored in this paper, exist between these two levels, operationalising abstract goals and means and encompassing specific on-the-ground measures and instrument calibrations.

The articulation of a broad policy aim – for example, involving citizens in improving public services – and the resulting general logic and norms to guide policy implementation represent the broadest level in the multi-layered process of policy-making (). At this stage, policy design nests and heavily impacts more specific mechanism-level preferences, which then in turn impact more operational-level settings and calibrations of on-the-ground policy measures (Hall, Citation1993; Howlett & Cashore, Citation2007, 2009).

Table 1. Co-production and the multiple levels of policy design. (Adapted from Howlett & Rayner, Citation2013).

Thinking of co-production in these policy design terms situates it as a policy instrument preference, borne from the broad goals of the NPG movement to increase citizen involvement in public service production (Osborne, Citation2010; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011). While no unanimously accepted, specific definitions currently exist for co-production practices, scholars have attempted to describe it as the mechanisms of social innovation that the public sector espouses to increase civic participation in addressing social needs (Brandsen and Pestoff Citation2006; Prahalad and Ramaswamy Citation2000; Voorberg et al., Citation2014).

A renewed interest through the 1990s and early 2000s towards new forms of participatory public governance invigorated a recognition that ‘publicly-desirable outcomes are likely to rely quite heavily on the contributions of multiple stakeholders, amongst whom users and communities in which they live are centrally important’ (Bovaird, Stoker, Jones, Loeffler, & Roncancio, Citation2015, p. 47).Terms such as ‘collaborative governance’ and ‘network governance’ have also been used to define the NPG reform movement to highlight the vision of a democratic and inclusive government looking to create more bottom-up mechanisms for policy-making (Bevir, Citation2007; Milward & Provan, Citation2000; Rhodes, Citation1994; Koppenjan & Klijn, Citation2012).

Co-production, in this sense, embodies a governance reform principle involving more inclusive participation by communities, citizens and a move away from top-down or managerial emphasis of earlier reform movements (Ostrom, Citation1996). Sicilia, Guarini, Sancino, Andreani, and Ruffini (Citation2016), expands this notion to emphasise that there are several reasons that have brought about the preference for increased citizen participation, and these include ‘the attempt to improve public service quality by bringing in the expertise of users and their networks; the need to provide public services that are better targeted and more responsive to users; the possibility of using co-production as a way of cutting costs; the opportunity to create synergies between government and civil society with a positive impact on social capital’ (p. 2, citing Brudney & England, Citation1983; Ostrom, Citation1996; Pestoff, Citation2009; Seligman, Citation1997).

Co-production of outcomes and behavioural change

While the ideals of NPG and the principles of co-production indicate, respectively, broad policy-level goal and policy preferences (column 1 in ), at the operational level of policy design, these translate to programme-level objectives and mechanisms (column 2 in ). The stage of design involves addressing questions regarding its desired outcomes, or what exactly a co-production-inspired policy expects to achieve through more inclusive policy processes. However, outcomes of co-production are an area of research that has not enjoyed as much attention as the broader principle of increased civic participation. Voorberg et al. (Citation2014), in their meta-analysis of the co-production concept, for example, delineate such processes that actively involve citizens in public service delivery as

the creation of long-lasting outcomes that aim to address societal needs by fundamentally changing the relationships positions and rules between the involved stakeholders, through an open process of participation, exchange and collaboration with relevant stakeholders including end-users, thereby crossing organizational boundaries and jurisdictions. (Voorberg et al., Citation2014, p. 1334)

Even though such a focus on outcomes may be implied in academic discussions of co-production, empirical studies have been traditionally more concerned with an understanding of citizen inputs when policy programmes are created (for example, Alford, Citation2002). Although this trend appears to be changing (Steen, Nabatchi, & Brand, Citation2016), and outcomes have been explicitly gauged in co-production studies in the past few years, they mostly surround efficiency measures, for example an increase in treatment quality for heart patients after the co-production of health care (Leone, Walker, Curry, & Agee, Citation2012), or where monetised measurements are possible and increased financial efficiency of service providers (Verschuere, Brandsen, & Pestoff, Citation2012). Still missing is an explicitly normative stance about what should co-production strive to achieve. As surmised by Bovaird and Loeffler (Citation2012, p. 1119),

public services should be designed to bring about ‘outcomes’ and not just ‘results’ and these outcomes should, in large measure, correspond to those which service users and citizens see as valuable, not simply those which are valued by politicians, service managers and professionals.

Along the same lines, the design of co-production programmes also needs to consider what instruments can be used to sustain these desired outcomes in the long-term. That is, what types of policy instruments can be used to achieve the policy outcomes that co-production formally aims to address (column 2, ). Answering this question relates to long-term behavioural change on the part of citizens and how this is a critical programme objective that needs to be addressed in order to see sustainable outcomes.

Aside from a few seminal studies that have emerged in this past year (for example, Bovaird et al., Citation2015), most empirical studies of citizen behaviour and co-production have, again, been in the context of how people contribute to the implementation of the activity rather than in the context of what social goals have been achieved through it. The widely used academic depictions of co-production have emphasised citizen inputs into the service delivery process as being largely ‘voluntary’ (Parks et al., Citation1981; Pestoff, Citation2006). And civic contribution, rather than community-level results of public activity, has remained central in major academic discussions of co-production. For example, Ostrom (Citation1996) illustrates co-production as the provision of ‘inputs used to produce a good or service by individuals who are not “in” the same organization’ (Ostrom, Citation1996, p. 1073).

In addressing this empirical deficit on links between behaviour and the outcomes of co-production, one major recent finding through an EU-wide comparative study has been that there is a marked difference in

the nature and level of collective co-production compared to individual co-production. It appeared that citizens are more likely to engage in co-production of public services and social outcomes with public agencies when the actions involved were relatively easy and could be carried out individually rather than in groups. (Bovaird et al., Citation2015; citing Löffler, Parrado, Bovaird, & Van Ryzin, Citation2008; Parrado, Van Ryzin, Bovaird, & Löffler, Citation2013)

The lessons derived from the cases below allow us to go a step further to suggest that the success of co-production is linked to the extent to which community-level behavioural change is articulated as an important objective during the design of a policy programme. The design of specific operational settings and tool calibrations (column 3, ) depend on empirical contexts and the operational experience with community-led total sanitation (CLTS) projects and their role in co-production-oriented sanitation policy in Bangladesh, India and Indonesia is therefore presented below.

Case selection and methodological considerations

An exploratory case study approach (Yin, Citation1994) informs this paper. The rich findings about community behaviour and the success of rural sanitation practices that have resulted from over 15 years of CLTS research in more than 50 countries present it as a critical case of co-production. Aligned with the stipulated definition of critical cases in case study research, lessons derived from CLTS projects ‘are likely to yield the most information and have the greatest impact on the development of knowledge’ (Patton, Citation2001, p. 236), in this case about the behavioural aspects of co-production success.

As discussed above, the empirical research informing the theoretical development of the co-production concept has been traditionally skewed towards a focus on participation and inputs by citizens, rather than on outcomes. Additionally, the concept has so far been explored as examples of post-New Public Management reforms, rather than as a subject of formal policy studies. In this light, CLTS examples provide an important opportunity to not only study co-production outcomes, but also learn about how they can be incorporated into the design of policy programmes based on co-production. By exploring the CLTS cases below through a policy design lens, a unique opportunity arises to inform theory (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), allowing for greater comparability of policy design across a group of co-production cases.

Case description and background

There is little doubt that a key determinant of the general health of any community has to do with its collective levels of hygiene and sanitation. Unhygienic practices surrounding the disposal of human excreta, in particular, are inextricably linked with the transmission of infectious diseases such as typhoid, cholera and other diarrhoeal and parasitic diseases that present a significant challenge to public health. While lacking access to effective mechanisms of disposing sewage and other wastes is clearly a major hindrance towards upholding sanitation in a community, it is only half the challenge. The provision of resources may not in itself be adequate in helping communities improve sanitation, if it is not accompanied by a collective will to change behaviours towards the handling and removal of waste. Achieving community-wide sanitation, then, is a target that relies on effective co-production by policy-makers and civil society because it is as heavily dependent on behaviours of citizens themselves as much as it is on the design of relevant policies by governments.

A major example of collective benefits through community-wide behavioural changes is found in the improved health outcomes in rural areas from the eradication of unhygienic waste disposal methods such as open defecation (OD). Diarrhoea is a major cause of childhood mortality in developing countries, where it leads to the death of approximately 800,000 children each year and unsanitary practices such as OD and lack of sustainable disposal facilities have been established as leading causes for such deaths (Liu et al., Citation2012; Prüss-Üstün, Bos, Gore, & Bartram, Citation2008). Furthermore, there is evidence that stunting in children can result in communities with OD, even if a child lives in a home with a toilet (Spears, Citation2013). The United Nations and the World Health Organization estimate that targets for improving global sanitation as a part of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) could become undermined and approaches such as CLTS have emerged to help mitigate against this challenge (Who, Citation2015). CLTS is defined as

an innovative methodology for mobilising communities to eliminate open defecation (OD). Communities are helped to conduct their own appraisal and analysis of open defecation (OD) and take their own decisions and actions to become open defecation free (ODF). CLTS focuses on the behavioural change needed to ensure real and sustainable improvements – investing in community mobilisation instead of providing sanitary hardware, and shifting the focus from toilet construction for individual households to the creation of ODF villages. By raising awareness that as long as even a minority continues to defecate in the open everyone is at risk of disease, CLTS triggers the community’s desire for collective change, propels people into action and encourages innovation, mutual support and local solutions, thus leading to greater ownership and sustainability. (Snel, Carrasco, & Dube, Citation2014, p. 5)

The CLTS approach was first pioneered in Bangladesh in 2000. By the end of 2016, CLTS has spread to over 60 countries, as sanitation sector leaders and financiers have recognised its value as a rapid catalyst of collective behaviour change for improving rural sanitation conditions (Kar & Chambers, Citation2008; Sigler, Mahmoudi, & Graham, Citation2014). CLTS has been adopted under various names in different jurisdictions, for example as Community-based Total Sanitation in Indonesia and Community Approaches to Total Sanitation (CATS) as promoted globally by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). By putting communities at the helm of improving their own public sanitation situations, CLTS has triggered a rethink of previous sanitation programme policies that were based on governments providing free or subsidised latrines to rural households (Kar & Chambers, Citation2008; Sigler et al., Citation2014).

The role of government agencies in improving rural sanitation is being redefined by CLTS in the three cases discussed below, from being providers of sanitation to becoming enablers and facilitators of community-wide behavioural changes that are chosen and executed by the communities themselves. For example, these behaviours include the eradication of OD and conversion of unimproved facilities to improved latrines. Thus, intrinsically CLTS is an instrument of co-production requiring specific types of collaboration between the state and its citizens in producing desired policy outcomes. The most vital of these outcomes is improved sanitation behaviours surrounding the use and maintenance of improved sanitation facilities, which improve living environments and promote human development and health.

During the first years following the launch of the CLTS, the movement spread across Bangladesh mainly through the information dissemination work of multiple NGOs. In 2003, Bangladesh hosted the first South Asian Conference on Sanitation (SACOSAN), wherein CLTS was showcased as an innovative example of co-production that can be scaled-up to national levels, indicating its applicability to other countries with rural sanitation policy objectives. Thereafter, exchanges supported by multilateral agencies such as the World Bank Water and Sanitation Program (WSP) helped the spread of CLTS into India and Indonesia during 2003–2005. In the years that followed, CLTS was further adopted across other countries in Asia and also Africa. While the particular methodology of CLTS has been adopted widely as a co-production tool, the larger changes to overarching policy objectives which are needed to maximise its transformative potential have taken much longer. In some countries, where CLTS has been fully incorporated in the co-production policy logic for rural sanitation, the outcomes have been vastly different than in others where sanitation services are still being forwarded without the active collaboration of target communities.

To illustrate this range of outcomes, this paper presents three CLTS cases where rural sanitation programmes are occurring at a national scale, namely in Bangladesh, Indonesia and India. The case studies have been chosen as major examples of the CLTS experience in order to illustrate the range of government responses to the rural sanitation challenge in Asia, from prioritising the construction of toilets over other interventions, to focusing entirely on catalysing behaviour changes and a combination of both. The paper examines the outcome and lessons learnt from the policy choices in the three countries during the period 2003–2015.

All three countries have long histories of donor-funded as well as government projects and programmes to improve rural sanitation, providing free or subsidised toilets to rural households, building communal latrines and dispensing health education. In all three countries, sector histories include rural sanitation approaches that have failed to scale up, slowing the growth of access to sanitation despite many years of interventions, and delivering weakly sustained results – measured mainly in terms of toilets constructed. With the emergence of collective behaviour-changing approaches like CLTS and sanitation marketing in the early 2000s, improvements to this situation have begun to emerge as governments in the region and elsewhere are beginning to adopt CLTS as a viable mode of co-production.

Methods

This analysis covers 12 years of CLTS experience, from 2003 to 2015. It is based on findings from census data, rural sanitation programme monitoring data from the relevant ministries, UNICEF-WHO Joint Monitoring Program updates, national programme evaluation surveys by government agencies and four independent research studies incorporating multi-province quantitative surveys of impact evaluation in India, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

Case study analysis: CLTS in Asia

Each case is organised in three broad sections. Firstly, a brief description of the particular national sanitation scenario introduces each case. Secondly, to focus on objective and mechanism design aspects of co-production (column 2, ), each case discusses to what extent behavioural change was incorporated into the initial definition of co-production policy objectives and the related instruments that were chosen to address them. Thirdly, each case then examines the progress and sustainability to date of the resulting behavioural outcomes.

Bangladesh

A country of just over 153 million people, Bangladesh is 72% rural and one of the most densely populated countries with 1050 persons per square kilometre. Although poverty rates have been declining in the last decade, its current Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is USD 1,314 (BBS, Citation2015). Bangladesh has achieved steady progress in improving population sanitation behaviour, in that the country has reduced the population practising open defecation from 42 to 1% within 12 years, from 2003 to 2015. Sanitation progress has contributed significantly to improvements in public health, and especially to the health of children. Child mortality of under five years of age has fallen from 133 to 38 per 1000 live births between 1990 and 2015 (UN-IGME, Citation2015) and the rate of decline has accelerated sharply after 2003.

In 2003, a nationwide baseline survey had found poor levels of sanitation, with only 33% of households with access to hygienic latrines and approximately 55 million people (42% of the population) practicing open defecation, the majority of whom lived in rural areas (Min LGRD&C, GoB, Citation2005). As a densely populated, flood-prone country inhabited by a large proportion of poor and ultra-poor communities, the resulting environmental contamination led to a heavy burden of diarrheal and parasitic diseases, and high levels of child mortality and malnutrition, with consequent negative impacts on the economy.

By 2015, the scenario had changed dramatically, as 61% of households have improved sanitation facilities and the population practising open defecation had fallen to 1%. Those who did not directly own improved latrines were making use of neighbourhood utilities rather than openly defecating as open defecation had become socially unacceptable in Bangladesh (Government of Bangladesh [GoB], Citation2016). In 2016, Bangladesh was officially declared ODF.

Phase 1: setting behavioural objectives and mechanisms (2003–2009)

Government commitment in Bangladesh and a multi-stakeholder approach to catalyse large-scale behavioural change began by setting policy objectives for sanitation in behavioural terms. In 2003, the GoB set a target of 100% sanitation by 2010. Policy instruments chosen to address this objective included a national directive to earmark 20% of annual local government development budgets for sanitation, and extensive project promotion at the sub-district level to raise awareness of the government sanitation goals. From 2003 to 2006, the government reached all parts of the country with a national sanitation campaign that was defined in behavioural terms ‘to achieve 100% sanitation coverage and stop open defecation in rural areas by 2010’. While these two criteria were the ones prioritised for monitoring during the 2003–2006 national campaign, the government’s National Sanitation Strategy in 2005 defined ‘100% sanitation’ in behavioural terms, emphasising a stop to open defecation, the availability and use of hygienic latrines, proper maintenance of latrines for continued use and improved hygiene practices by communities (Ministry of LGRD&C, GoB, Citation2005).

The behavioural focus of this objective had far-reaching implications on the approaches chosen to implement the campaign, and the indicators by which progress was measured. While previous sanitation programmes had only aimed at the construction of durable sanitary latrines by individual households, the 2003 campaign focused on eliminating human faeces from the living environment by getting all community households to stop open defecation. Sanitation promotion techniques included those that triggered collective change by whole communities – because success was to be measured in terms of collective change, i.e. totally sanitised households with latrines or ODF communities. The campaign was implemented through a range of additional interventions such as:

Local government leaders promoting collective change

Collaborations between government, NGO and donor agencies at national, district and sub-district levels, all linked to the same target outcome

Media campaigns helping to promote social norms against open defecation

Technological innovations and creative marketing approaches to provide the poorest consumers with access to affordable supplies and skills

Increased access to latrine materials and skilled masons in local market

During the campaign, central, district and sub-district governments played a lead role in social mobilisation to influence whole communities to stop open defecation. Rewards were also offered by the central government to local villages that successfully promoted the installation of latrines in all resident households, and successfully achieved the ‘100 percent sanitized’ status by becoming open defecation-free (ODF).

Behavioural aspects related to the willingness to pay for community sanitation were also encouraged by the local governments. For example, the co-production of sanitation facilities required voluntary investment by citizens, even though it was common for village leaders to provide free or subsidised latrine construction packages to the poorest households. The recipients in turn had to get their facilities installed using their own or paid labour and masons. Better off households preferred to procure supplies of their choice from local markets. For neither of these groups did the government build the actual facilities, focusing instead on empowering citizens to change their attitudes towards defecation.

While the local government took a lead role in facilitating behavioural transitions related to open defecation, NGOs supported the continued implementation in many regions even after the campaign concluded. Behavioural change promotions directed towards households were communicated through mass, group and interpersonal media channels and settings, including information mobilisation by local government officers through meetings, rallies, loudspeaker announcements and household visits. Advocacy from the central government down to the local governments with a clear single agenda to shift people from open defecation to fixed point defecation through construction of low-cost latrines – sometimes shared among two or three families – was the key factor in unifying the country around sanitation (Ministry of LGRD&C, GoB, Citation2016)

Phase 2: Sustainability of behavioural outcomes (2010–present)

A large-scale quantitative and qualitative assessment was undertaken during 2010–2011, following the 2003–2006 campaign, in local village units that were declared ODF four and a half years ago. The study (Hanchett, Khan, Krieger, & Kullmann, Citation2011) found that the sanitation behaviour change campaign has had sustained impact on the whole. Given that only 29% of rural households were using any type of improved latrines in 2003, the 2010–2011 study found that:

89.5% of sample households continued to use their own or share a latrine that safely confines waste.

70% of sample households owned their current latrine for at least three years, indicating that the majority of latrines that were built are fairly durable.

All implementation approaches focused on achieving total sanitation but implemented by various agencies (government, donor or NGOs) resulted in sustained high latrine use and low rates of open defecation.

The social norm of defecating in the open had generally been rejected and was a significant factor in sustaining the use of latrines. Previously, latrine use was the norm mostly among upper income groups or in areas covered by earlier campaigns. In 2011, however, it had become a socially accepted practice at all levels of society, including the poorest wealth quintile. Those who continued to practice open defecation were socially criticised. Social norms pertaining to marriage arrangements, village respectability and village purity for religious events were widely assumed to require the use of improved latrines.

Households with female heads were more likely to have an improved or shared latrine compared to households headed by males. The study suggested that the 2003–2006 campaign possibly tapped into latent demand by millions of females to have a latrine for cultural and hygiene reasons.

Follow-up programmes that continued to reinforce sanitation behaviours were associated with the sustained use of improved or shared latrines. Approximately 65% of local government chairpersons continued to remind constituents of the importance of ‘hygienic’ latrine use, providing latrine parts to poor families, declaring local rules against open defecation and following up on sanitation-related complaints.

High access to latrine parts and maintenance services from local markets (catalysed by the spurt in demand) had likely contributed to sustained use of latrines. The emergence of a mature private sector meant that heightened market demand by communities had allowed most households to access affordable parts and services that can help sustain the use of improved and shared latrines.

Indonesia

Indonesia is a country of 254.5 million, spread over 17,000 islands. It has achieved impressive poverty reduction milestones indicated by a GNI per capita increase from $560 in the year 2000 to $3,650 in 2014. However, income inequities are high with 11% of Indonesians currently below the poverty line and another 40% clustered around it. Access to improved sanitation facilities currently stands at 61% of the population, and around 52 million still defecate in the open of whom 34.3 million live in rural areas (JMP 2014 Update). Meanwhile, costs to the country from poor sanitation practices have been estimated at US$6.3 billion annually equivalent to 2.3% of its GDP (Hutton, Haller, & Bartram, Citation2007).

Phase 1: setting behavioural objectives and mechanisms (2007–2010)

For several decades, rural sanitation efforts in Indonesia had focused on improving access to basic sanitation using hardware subsidies and hygiene education without much effort to change behaviours related to sanitation. The approach proved to be ineffective, highlighting the size of the challenge. Rural household access to improved sanitation grew at less than 1% per year from 1985 to 2006, reaching only 20.6% in 2006. With less than 10 years to 2015, the rural MDG target of achieving 56% sanitation seemed well beyond reach. In order to adopt a new approach to sanitation, policy-makers and sector administrators began to implement CLTS principles as policy successes in Bangladesh and elsewhere become well known in the region.

Adopting a new, behaviour-oriented approach to sanitation, the Ministry of Health (MoH) declared CLTS as the main instrument to target rural sanitation in 2006 in addition to a parallel campaign to encourage handwashing with soap. By 2007, Indonesia became the first country in East Asia to embark on a new rural sanitation initiative combining CLTS and sanitation marketing with strengthening enabling policy and institutional environments. This was the Total Sanitation and Sanitation Marketing (TSSM) project covering all of East Java, a province of 37.5 million people.

After several decades of stagnation, the rural sanitation scene began to change radically. TSSM signalled a complete break away from past subsidy-based approaches, and offered only a nine-month window of technical assistance to local governments interested in becoming ODF districts. Almost all of East Java district governments opted to participate in the TSSM project, with the investment of their own human resources and budgets in this learning initiative. Indonesia’s first definition of an ODF community and methods to verify ODF status were developed by TSSM for the use of district governments in East Java, in 2008. It has been adopted for national use since the year 2012. Four years later, by the end of TSSM, 2,200 communities had been verified as ODF, and more than 1.4 million people had gained access to improved sanitation over the baseline of 2007, with 100% of the sanitation improvements being financed by rural households themselves.

Within a year of TSSM implementation in East Java, the MoH officially discontinued hardware subsidies for household latrines nationally by identifying key hygiene behaviour changes in communities – including eliminating open defecation – as its main objective for achieving improved sanitation. The national rural sanitation goal was first set in collective behaviour terms as ‘Indonesia ODF 2014’, in the National Medium Term Development (MTD) Plan 2010–2014. Although initially unrealistic, the 2014 ODF target served to highlight what it will take to push collective behaviour changes on a nationwide scale. The definition of ODF status and ODF verification guidelines first applied in East Java by the TSSM project in 2008 were adopted for national use by the MoH in 2011.

Phase 2: sustainability of behavioural outcomes (2010–present)

The 2015–2019 Plan for achieving sanitation has now set the national goal as 100% universal access by 2019. It has become evident that the 11% annual access growth rate required to achieve such a goal will require a lot more than ‘business as usual’ practices. While funding levels and channels of intervention are being greatly enhanced, sector monitoring systems continue to track and publicise both access gains and ODF achievements by villages, sub-districts and districts. To further encourage behavioural transformation, the verification procedure provides for sustainability checks every two years and even allows for ODF status to be revoked when communities are found to have slipped (MoH, Citation2013).

Sustainability of outcomes was investigated in Indonesia through three major studies, a market research study (Nielsen, Citation2009) during the course of TSSM which informed the sanitation marketing strategy developed for East Java; a participatory evaluation of TSSM project outcomes with 80 communities that experienced the TSSM interventions (Mukherjee, Robiarto, Effentrif, & Wartono, Citation2012); and an impact evaluation by the World Bank (Cameron, Shah, & Olivia, Citation2013). Each study provides important learning about how behavioural aspects impact the sustainability of co-production of improved sanitation behavioural outcomes at scale.

The Nielsen market research identified underlying motivations that drive rural population behaviours to continue with open defecation or switch to building and using sanitary toilets. It identified the barriers that poorer consumers experience in making the switch and helped craft a marketing strategy that is now being implemented in multiple Indonesian provinces (Nielsen, Citation2009). The impact evaluation by the World Bank (Cameron et al., Citation2013) found a reduction in open defecation among households that had lacked latrines before TSSM. It also found measurable positive health impact on children under five in communities that had experienced TSSM interventions for sanitation behaviour change, as compared to control communities that did not. However, it also revealed that the poorest households had gained much less access to sanitation than their non-poor neighbours in TSSM project areas. The findings helped refine the sanitation marketing strategy to target poorest consumers better. Lastly, the participatory action research with TSSM communities found that, provided the CLTS triggering process was of sufficient quality, ODF achievement and sustainability were hastened by:

A community’s social capital and the involvement of leadership in the change process,

The local availability and affordability of latrine attributes desired by poor and non-poor consumers,

An absence of externally provided subsidies to a few households and

Post-triggering monitoring and follow-up by external agencies working together with communities.

The action research also found that sanitation behaviour change is difficult to ignite in riverbank and waterfront communities and special strategies were needed for them. The national Strategy has been since refined using these findings. Recent estimates show that household access to improved sanitation has risen to 61%. With the adoption of behavioural goals and consequent changes in programme approaches, Indonesia’s rural sanitation access growth rate has accelerated from less than 1% in the years before 2006 to 3.4% per annum during 2007–2013. Rural access to improved sanitation has more than doubled in seven years: from 20% in 2006 to 44% households in 2013 (BPS Indonesia, Citation2014). The percentage of the population defecating in the open in 1990 has been halved by 2015, with the bulk of the decline occurring in rural areas.

India

According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) update (2014), India houses one-sixth of the world’s population, but more than half of the world’s open defecators. The problem is predominantly rural. The 2011 National Census showed that of 1.2 billion Indians, 833 million live in rural areas, and 67% defecate in the open. While that percentage has declined marginally to 61% as of 2015 WHO/UNICEF (Citation2014, Citation2015), the actual numbers of open defecators have increased rather than declined, from 2011 to 2015. The real numbers of open defecators in India are even higher, as recent behavioural research reveals that 46% of latrine owners continue with open defecation in villages, out of a preference for the practice (Coffey et al., Citation2014). And despite massively funded national sanitation programmes, economic losses due to poor sanitation are estimated to be costing India as much as US$53.8 billion annually, equivalent to 6.4% of its GDP at 2006 prices. (WSP, Citation2010). Recent research in multiple countries is pointing out even more challenging consequences of poor sanitation practices. Children growing up in communities where open defecation is practised or unhygienic unimproved facilities are used suffer physical and cognitive growth losses that are often irreversible. This relationship holds true whether or not the children’s families themselves use sanitary latrines (Quattri, Smets, & Nguyen, Citation2014; Spears, Citation2013).

The rural sanitation sector in India has attracted unprecedented and steadily rising levels of national government funding for several decades, with suboptimal outcomes. Sector research over several years has shown that since the first national effort towards sanitation began in the 1990s, the Central Rural Sanitation Program (CRSP) was not able to show desired results. With successive revisions of the CRSP formula, funding was scaled up further and policies tweaked peripherally, however, without many positive results.

Despite growing evidence from these efforts, the original premises underlying CRSP were never reformulated as the government continued its policies of providing increasing levels of hardware or cash subsidies to household for toilet construction, as it transitioned from CRSP to subsequent yet similar sanitation policies in 1999 and 2012. The latest in the series, the SWACHH Bharat Mission – Grameen launched in 2014 is arguably the largest ever rural sanitation programme to date globally. It retains the same core policy commitment to building millions of toilets for households that are without access. However, there seems to be a new openness to change at the level of defining policy objectives, with recent research evidence about the impact of poor sanitation behaviours on health, human development and the economy.

Phase 1: absence of behavioural objectives and mechanisms (1980s–2013)

Rural access to improved sanitation increased from 1990 to 2015 at the rate of less than 1% per year, despite the following progression of generously funded national programmes (WHO/UNICEF JMP, Citation2015). Throughout this period, rural sanitation policies and programmes were designed to be focused on increasing access to sanitation, aimed at targets set for latrine construction and consequently monitored only the extent of budgets expended and numbers of facilities built. Improvement of population sanitation behaviours remained absent from definitions of programme objectives and targets, missing from the indicators of progress and performance monitoring and therefore often missing from approaches used for implementation.

The CRSP was introduced in 1986 and its approach of providing cash subsidies per household to cover full costs of toilet construction produced only 8% improvement in rural sanitation coverage between 1981 and 1991, way below the target of 25% during the same period. A newer iteration of the programme in 1999 incorporated new terminology into objective design including ‘community-led’ and ‘people- centred’, along with the need to ‘generate community demand’ for improved sanitation (Government of India, Citation2004). Yet, subsidies for household latrine construction remained and were renamed as an incentive for households that were below poverty line. The extent of subsidies was initially much reduced, but continued to be revised upwards till it was meeting a bulk of the construction cost. Still, the campaign failed to produce the expected acceleration of sanitation coverage.

In 2003, a behavioural focus was added, though not in programme objectives or targets and instead as a minor principle. A reward component was added to the policy, for helping villages achieve ODF status with access to improved solid and liquid waste disposal mechanisms (GoI, Citation2004). While the awards generated sanitation awareness, they also brought pressure from village leadership and local governance on ordinary citizens to fall-in-line and acquire standard sanitation facilities regardless of their consent. Principles of community-led collective behaviour change and co-production of outcomes were placed increasingly at risk as the programme proceeded to scale-up. By 2011 more than 28000 of India’s 250,000 Gram Panchayats (village councils) had received awards following one-time checks. Subsequent evaluations of the programme revealed high levels of slippage from ODF status and sustainability problems with latrine usage and functionality. (Government of India, Citation2011)

In April 2012, the sanitation policy was recast as Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (NBA) with a renewed emphasis on even more accelerated toilet construction and monitoring of construction. The new features were a strategy of ‘saturation’ of population pockets with toilets, even larger cash subsidies for household latrines and further resource mobilisation for construction by converging rural sanitation programmes with rural livelihood and employment guarantee schemes. Beset with many implementation bottlenecks, the NBA programme was replaced in 2014 by the present sanitation policy, the SWACHH Bharat Mission – Gramin (SBM-G) (Government of India, Citation2014).

Phase 2: setting behavioural objectives and mechanisms (2012–present

Several landmark evaluations and research studies during 2011–2014 laid bare the nature of the real challenge in India. An evaluation of previous sanitation policies by the Government of India (GOI Planning Commission, Citation2013) found that nearly 73% of the rural population practised open defecation, including households that had their own latrines. A survey of 22,000 households in the rural heartlands of open defecation found hitherto un-researched motivations underlying open defecation, which have possibly been confounding government efforts for years to improve sanitation by providing toilets for all. Some examples of the survey findings include:

A distinct preference for open defecation was common as 47% open defecators find the practice pleasant, comfortable and convenient. Some even think it is better for health than using a household latrine. Over 40% of households with a working latrine have at least one open defecator. Government latrines are particularly unlikely to be used. Most people who own a government-constructed latrine defecate in the open anyway. (Coffey et al., Citation2014)

Through these findings and others, it is increasingly being recognised that SBM-G is acknowledging the need to incorporate a behavioural goal focus and build institutional capacity accordingly. The SBM-G Guidelines issued in late 2014 include, for the first time, ‘elimination of open defecation’ among the principal mission objectives. This behaviour change is stated as instrumental for achieving SWACHH Bharat (Clean India) by October 2019, a target espoused by the Prime Minister. Methodologies for implementation recommend community-led and community saturation approaches for collective behaviour change rather than toilet construction. Recognising that objective setting is meaningful only if progress is measurable; the December 2014 SBM-G guidelines state, also for the first time, that ‘the main focus of the monitoring arrangements for the Mission is on toilet usage through the creation of ODF Communities. The system [monitoring] shall be upgraded to enable the reporting of the creation of ODF communities and their sustenance’. During 2015, the government has followed through with standardising a definition for ODF communities and procedural requirements for verifying ODF achievements uniformly by all state governments (GOI, Citation2016).

The next immediate challenge for the rural sanitation sector institutions in India is scaling up understanding of the changed nature of the task ahead, and building institutional capacity fast enough to be able to facilitate sanitation behaviour change in a country of India’s scale by October 2019. The sustainability of this new focus on behavioural change as a sanitation policy objective would be assessable at that time.

Concluding comments – designing co-production policy for sustainability

As examined through the lens of policy design, the principles of co-production can penetrate three levels of policy-making. Building on the foundations of greater civic participation as advanced by the NPG reforms of the past two decades, co-production firstly embodies a broad policy-making logic. It is a norm which involves a preference for policy instruments that espouse the participation of civic society. Secondly, at a more specific level of policy programmes, co-production means the participation of citizens in the defining of policy programme objectives and the choice of mechanisms to meet those objectives. Thirdly, co-production can influence the way in which instrument settings and calibrations are used on-the-ground, in tune with different empirical contexts.

Incorporating outcomes into coproduction design

In an endeavour to understand how co-production can be studied through its desired outcomes, this paper explored an important case of civic engagement towards meeting societal goals. Years of experience with the particular case of co-production represented by the CLTS movement have shown that achieving an important public outcome such as rural sanitation depends equally on individual inputs as well as community behaviours in order to be successful and have lasting results. In summing up the findings of the paper, the three cases show three different levels of progress in co-production policy, designed with an explicit outcome-oriented, behavioural focus. Bangladesh was the first to incorporate a behavioural focus in its national rural sanitation interventions, in 2003, many years before other developing countries in Asia and Africa. Indonesia came on board with a behavioural policy objective in 2009, which catalysed its national sanitation strategy. India made the change later, in 2014 with the Swachh Bharat Mission – Gramin. While none of the three countries met its MDG target for sanitation by end 2015, Bangladesh and Indonesia were very close and their progress has been directly linked to incorporating behavioural change as their co-production programme objective for rural sanitation. India is still facing several hindrances towards fulfilling its Swachh Bharat (Clean India) target by October 2019. With its newly adopted behavioural focus, progress towards achieving rural sanitation looks promising and remains to be observed.

The three cases highlight how adopting behavioural change as an objective of a coproduction programme has led to the long-term sustainability of the desired outcomes, that in this case surround improved rural sanitation. As discussed earlier in this paper, empirical work on co-production has mostly concerned the inputs that citizens can bring to a policy or a programme, or on defining what the stated outputs of such collaborative efforts should be. The CLTS cases in Bangladesh, India and Indonesia all indicate that an equal emphasis on the long-term outcomes of a coproduction necessitates that the design of programme objectives and mechanisms be aligned with these outcomes.

Using the lessons derived from the cases to extend from the policy design framework discussed earlier, incorporates a concern for outcomes into the design considerations for co-production programmes. Policy design thinking already emphasises a dialectic between programme-level objectives and programme-level mechanisms in order to maximise the complementarity with existing policy settings (Howlett et al., Citation2014). However, the CLTS cases reveal a third important consideration that of programme-level outcomes that need to be included to uphold the sustainability of any co-production effort.

In the CLTS cases, this three-way complementarity of policy programme components is indicated by the finding that including citizens in changing sanitation behaviour should be a programme objective as it is directly necessary for achieving the desired programme outcome of total sanitation (or an open-defecation free status). The adoption of behavioural change objectives in rural sanitation programmes also leads to the selection of programme mechanisms and monitoring indicators that support and track community-wide sanitation practices, thus increasing the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes (rather than just the production of outputs). As the case in India has particularly shown, if the objectives are not aligned with the desired outcomes, and instead are only concerned with outputs (for example, increasing the number of toilets instead of addressing sanitation behaviours), this can lead to challenges in achieving stated policy goals.

Highlighting the impact that behavioural considerations can have on co-production, the findings from these cases indicate a basic theoretical groundwork for advancing the work on co-production outcomes and inspire future questions regarding what it takes to design participatory policy at multiple levels of governance: ranging from broad policy goals to micro-level policy instruments. In this light, co-production outcomes need to be defined holistically, including both the services and the behaviours associated with them that need to be produced, in order that the outcome benefits and streams of benefits that are generated are sustained over the long-term.

Notes on contributors

Ishani Mukherjee is a research fellow (Adj.) at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore and Practice Lead (Sustainability) at Global Counsel. Her research interests combine policy design and policy formulation, with a thematic focus on policy instruments

for environmental sustainability and renewable energy. She is the recipient of the World Future Foundation Prize for Environmental and Sustainability Research in 2014. She has worked previously at the World Bank’s Energy practice in Washington, DC on formulating guidelines and evaluating projects related to renewable energy, rural electrification and energy efficiency. She received her PhD in Public Policy from NUS and her MS in Natural Resources and Environmental Economics from Cornell University.

Nilanjana Mukherjee , World Bank Water and Sanitation Program (WSP), 1996–2015. Mukherjee has worked with country governments of India, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Philippines, Mongolia and Vietnam in WASH policy formulation, sustainability and equity. From 2006 to date she has focused on developing national strategies and institutional capacities for scaling up rural sanitation programs in Indonesia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. She currently works as an independent international consultant.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alford, J. (2002). Why do public-sector clients coproduce? Toward a contingency theory. Administration & Society, 34(1), 32–56.10.1177/0095399702034001004

- BBS. (2015). GDP of Bangladesh 2014–2015 (p) (Base: 2005–06), Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

- Bevir, M. (2007). (Ed.). Public governance. (Vol. 4). London: Sage.10.4135/9781446263082

- BPS Indonesia (2014). Statistik Indonesia 2014 Badan Pusat Statistik - Statistics Indonesia. Jakarta: Government of Indonesia.

- Bovaird, T., & Loeffler, E. (2012). From engagement to co-production: The contribution of users and communities to outcomes and public value. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23, 1119–1138.

- Bovaird, T., Stoker, G., Jones, T., Loeffler, E., & Roncancio, M. P. (2015). Activating collective co-production of public services: Influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82, 47–68. doi: 10.1177/0020852314566009

- Brandsen, T., & Honingh, M. (2015). Distinguishing different types of coproduction: A conceptual analysis based on the classical definitions. Public Administration Review, 76, 427–435.

- Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2006). Co-production, the third sector and the delivery of public services: An introduction. Public Management Review, 8, 493–501.

- Brudney, J. L., & England, R. E. (1983). Toward a definition of the coproduction concept. Public Administration Review, 59–65.10.2307/975300

- Cameron, L., Shah, M., & Olivia, S., (2013) Impact evaluation of a large-scale rural sanitation project in Indonesia ( World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 6360). The World Bank.

- Coffey, D., Gupta, A., Hathi, P., Khurana, N., Spears, D. Srivastav, N., & Vyas, S. (2014). Revealed preference for open defecation: Evidence from a new survey in rural north India ( SQUAT Working Paper No. 1.). Research Institute for Compassionate Economics (RICE)

- Eisenhardt K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management, 14, 532–550.

- Government of Bangladesh (GoB). (2005). Ministry of local government, rural development and cooperatives. Dhaka: National Sanitation Strategy.

- Government of Bangladesh (GoB). (2016). Bangladesh country paper. Sixth South Asian Conference on Sanitation (SACOSAN-VI), Local government Division, Ministry of Local government, Rural Development and Cooperatives, Dhaka.

- Gunningham, N., & Sinclair, D. (1999). Regulatory pluralism: Designing policy mixes for environmental protection. Law and Policy, 21(1), 49–76.10.1111/lapo.1999.21.issue-1

- Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning and the state: The case of economic policy making in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296.10.2307/422246

- Hanchett, S., Khan, M. H., Krieger, L., & Kullmann, C. (2011). Sustainability of sanitation in rural Bangladesh. In The future of water sanitation and hygiene: Innovation, adaptation and engagement in a changing world. Loughborough, UK: 35th WEDC International Conference.

- Howlett, M., & Cashore, B. (2007). Re-visiting the new orthodoxy of policy dynamics: The dependent variable and re-aggregation problems in the study of policy change. Canadian Political Science Review, 1(2), 50–62.

- Howlett, M., & Cashore, B. (2009). The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11(1), 33–46.10.1080/13876980802648144

- Howlett, M., & Lejano, R. P.. (2013, April 1). Tales from the crypt: The rise and fall (and Rebirth?) Oof policy design. Administration & Society, 45(3), 357–381. doi:10.1177/0095399712459725

- Howlett, M., & Rayner, J. (2013). Patching vs packaging in policy formulation: Assessing policy portfolio design. Politics and Governance, 1(2), 170–182.10.17645/pag.v1i2.95

- Howlett, M., Mukherjee, I., & Rayner, J. (2014). The elements of effective program design: A two-level analysis. Politics and Governance, 2(2), 1–12.

- Hutton, G., Haller, L., & Bartram, J. (2007). Global cost-benefit analysis of water supply and sanitation interventions. Journal of Water and Health, 5, 481–502.

- Kar, K., & Chambers, R. (2008). Handbook on community-led total sanitation. London: Plan UK.

- Koppenjan, J. F. M., & Klijn, E. H. (2012). Managing uncertainties in networks: A network approach to problem solving and decision making. London: Routledge.

- Leone, R., Walker, C., Curry, L., & Agee, E. (2012). Application of a marketing concept to patient-centered care: Co-producing health with heart failure patients. Online journal of issues in nursing, 17(2), 7–14.

- Liu, L., Johnson, H. L., Cousens, S., Perin, J., Scott, S., Lawn, J. E., … Mathers, C. (2012). Child health epidemiology reference group of WHO and UNICEF global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2151–2161.10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1

- Löffler, E., Parrado, S., Bovaird, T., & Van Ryzin, G. (2008). If you want to go fast, walk alone. If you want to go far, walk together. Citizens and the co-production of public services. Report to the EU Presidency. Paris: Ministry of Finance, Budget and Public Services.

- Milward, H. B., & Provan, K. G. (2000). Governing the hollow state. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(2), 359–380.10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024273

- Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India. (2014, December). Guidelines For SWACHH BHARAT MISSION (Gramin)

- Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India. (2016, January). Country Paper – India. Sixth Asian Conference on Sanitation (SACOSAN VI), Dhaka.

- Ministry of Health. (2013). RI, Buku Saku Verikasi Sanitasi Total Bernbasis Masyarakat [Community-based total sanitation verification booklet]. Jakarta: Directorate of Environmental Health, Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia.

- Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives (LGRD&C), Local Government Division, People’s republic of Bangladesh. (2005). National Sanitation Strategy.

- Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives (LGRD&C), Local Government Division, People’s republic of Bangladesh. (2016, January). Bangladesh country paper. Sixth South Asian Conference on Sanitation (SACOSAN).

- Ministry of Rural Development, Department of Drinking Water Supply, Government of India. (2004). Guidelines on Central Rural Sanitation Programme, Total Sanitation Campaign.

- Ministry of Rural Development, Department of Drinking Water Supply, Government of India. (2011, March). Assessment study of Iimpact and sustainability of Nirmal Gram Puraskar.

- Mukherjee, N. & with Robiarto, A., Effentrif, S. and Wartono, D. (2012). Achieving and sustaining open defecation free communities: Learning from East Java. Washington, DC: Water and Sanitation Program (WSP).

- Nielsen, Indonesia (2009). Total sanitation and sanitation marketing research report. Washington, DC: Water and Sanitation Program, World Bank.

- Osborne, S. P. (2010). The new public governance: Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance. London: Routledge.

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087.10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Parks, R. B., Baker, P. C., Kiser, L., Oakerson, R., Ostrom, E., Ostrom, V., … Wilson, R. (1981). Consumers as coproducers of public services: Some economic and institutional considerations. Policy Studies Journal, 9(7), 1001–1011.10.1111/psj.1981.9.issue-7

- Parrado, S., Van Ryzin, G. G., Bovaird, T., & Löffler, E. (2013). Correlates of co-production: Evidence from a five-nation survey of citizens. International Public Management Journal, 16(1), 85–112.10.1080/10967494.2013.796260

- Patton, M. Q. (2001). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pestoff, V. (2006). Citizens and co-production of welfare services: Childcare in eight European countries. Public Management Review, 8(4), 503–519.10.1080/14719030601022882

- Pestoff, V. (2009). Towards a paradigm of democratic participation: Citizen participation and co-production of personal social services in Sweden. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 80(2), 197–224.10.1111/apce.2009.80.issue-2

- Pestoff, V., Brandsen, T., & Verschuere, B. (Eds.). (2013). New public governance, the third sector, and co-production . (Vol. 7). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Planning Commission. (2013). Evaluation study on total sanitation campaign. Programme Evaluation Organisation, Government of India.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform: A comparative analysis-NPM, governance and the neo-Weberian State (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pollitt, C., & Hupe, P. (2011). Talking about government: The role of magic concepts. Public Management Review, 13(5), 641–658.10.1080/14719037.2010.532963

- Prahalad, C. K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2000). Co-opting customer competence. Harvard Business Review, 78, 79–90.

- Prüss-Üstün, A., Bos, R., Gore, F., & Bartram, J. (2008). Safer water, better health: Costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Quattri, M., Smets, S., & Nguyen, M. (2014). Investing in the next generation: Children grow taller and smarter, in rural, mountainous villages of Vietnam where community members use improved sanitation, WSP Research Brief. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1994). The hollowing out of the state: The changing nature of the public service in Britain. The Political Quarterly, 65(2), 138–151.10.1111/poqu.1994.65.issue-2

- Sancino, A. (2015). The meta co-production of community outcomes: Towards a citizens’ capabilities approach. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–16.

- Seligman, A. B. (1997). The problem of trust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sicilia, M., Guarini, E., Sancino, A., Andreani, M., & Ruffini, R. (2016). Public services management and co-production in multi-level governance settings. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82, 8–27. doi: 10.1177/0020852314566008

- Sigler, R., Mahmoudi, L., & Graham, J. P. (2014). Analysis of behavioral change techniques in community-led total sanitation programs. Health promotion international, 30(1), 16–28.

- Snel, M., Carrasco, M., & Dube, A. (2014, November). The role of community-led total sanitation (CLTS) in providing sustainable sanitation. IRC Report. Delft, Netherlands.

- Spears, D. (2013). How much international variation in child height can sanitation explain? ( Policy Research Working Paper; No. WSP 6351). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Steen, T., Nabatchi, T., & Brand, D. (2016). Introduction: Special issue on the coproduction of public services. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 3–7. doi:10.1177/0020852315618187

- UN-IGME. (2015). Levels & trends in child mortality, UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. New York, NY: WHO, Unicef and World Bank.

- Verschuere, B., Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2012). Co-production: The state of the art in research and the future agenda. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit, 24, 1083–1101.

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2014). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, ( ahead-of-print), 1–25.

- Water and Sanitation Program. (2010). The economic impact of inadequate sanitation in India. Economics of sanitation initiative. New Delhi, India: WSP, The World Bank.

- Who, U. (2015). Progress on drinking water and sanitation–2015 update. World Health Organization, Organizations, 23(4), 1083–1101.

- WHO, UNICEF. (2014). Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2014 Update and SDG assessment. New York, NY: UNICEF and World Heath Organization.

- WHO, UNICEF. (2015). Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2014 Update and SDG assessment. New York, NY: UNICEF and World Heath Organization.

- Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage.