ABSTRACT

Understanding the performance of collaborative governance regimes (CGRs) necessitates an understanding of how stakeholders and their interactions evolve over time. However, few studies assess the evolution of the structure or process dynamics of CGRs over time. This paper contributes to our understanding of the longitudinal dynamics of CGRs. We apply a modified grounded theory approach to a dataset of collaboration case studies to develop empirically-based theory about how often CGRs persist over time, how different components of CGRs evolve over time, what conditions support or hinder this evolution, and how different developmental trajectories lead to differences in the outputs and outcomes achieved by these groups. We find that CGRs follow a variety of trajectories, from failing to initiate, to achieving their work in a relatively quick time, to sustaining their operations for decades, to incurring slow or rapid declines in health. Additionally, many characteristics of CGRs, including leadership, collaborative process, accountability, and outputs/outcomes, peak at the midpoint of the observed time, suggesting that at some point, even stable and healthy collaborations incur some decline in their robustness. As an exploratory study, this work highlights the need for a better accounting of how CGRs develop, sustain, evolve, and decline over time.

Introduction

Collaborative governance regimes (CGRs) are systems in which ‘the processes and structures of public policy decision making … engage people across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public private and civic spheres to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished’ (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b, p. 18). Like all institutions, CGRs are dynamic entities that can change and evolve. They are not static at either the individual or organizational level, nor is the world they operate in static (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Imperial et al., Citation2016; Newig, Derwort, & Jager, Citation2019). As such, collaborations need different resources, facilitation, and support at different times to be successful or healthy (Genskow & Born, Citation2006; Imperial et al., Citation2016). Likewise, their outputs and outcomes are likely to vary based on their temporal development (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Imperial et al., Citation2016). Understanding the full performance of CGRs necessitates an understanding of how stakeholders and their interactions evolve over time. With this understanding, we can learn how to sustain healthy collaborations over time, assist in their adaptation, or manage their termination when the time comes (Imperial et al., Citation2016; Newig et al., Citation2019).

However, few studies assess how the structure or process dynamics of CGRs evolve over longer periods of time (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b). The handful of theoretical frameworks on the evolution of collaborative and networked governance generally suggest that networks start out relatively turbulent as participants establish relationships and goals, and then formalize as the group works together over time. For instance, focusing purely on the structure of collaboration, Provan and Kenis (Citation2008) propose that networks should evolve from being more participant-governed, grassroots groups to more formalized, externally directed entities. Mandell and Keast (Citation2007) posit a four-stage lifecycle: 1) formation entails bringing people together, setting goals, and starting to build the trust and relationships to work together; 2) in stabilization, the group begins to develop the skills to sustain collaboration and gain external legitimacy; 3) in routinization, collaboration has become a norm; and 4) in extension, collaboration becomes seen as a viable, self-sustaining entity.

Importantly, this theoretical work does not extend to how collaborative arrangements – once they are established – change, evolve, transform, or decline. Not all collaborations become successful or remain successful once they reach maturity. Trying to more fully capture the lifecycleFootnote1 of CGRs, Imperial et al. (Citation2016) adapt a complex systems framing for collaborations. While the early stages of their framework are familiar (wherein the group activates, becomes institutionalized over time, and eventually reaches a stable setting), they argue that eventually the group will shift in response to internal or external demands, and that this shift – depending on how it is managed – could either lead to a decline of the CGR or a reorientation to become a ‘new’ entity (Imperial et al., Citation2016). The few existing empirical studies of collaboration over time suggest a decline in both participation (stakeholders tending to drop out over time) and engagement (internal communication becoming less prominent) (Heikkila & Gerlak, Citation2016; Hui, Ulibarri, & Cain, Citation2018; Scott, Ulibarri, & Scott, Citation2020).

Besides observing how collaborations evolve, it is important to consider what factors drive different trajectories of change. For instance, under what conditions do newly-formed collaborations fail to achieve a mature enough stage to reach their goals? What makes a CGR successfully reorient to internal or external changes, as opposed to decline? Here, we again have some theoretical guidance. Regarding reorientation, Emerson and Gerlak (Citation2014) draw on a collaborative watershed management case study to propose four factors enabling successful adaptation: engaging a diversity of interests which lead to a broader commitment; a focus on internal and external legitimacy, which enabled influence; shared learning, which lead to cognitive flexibility; and shared access to resources, which enabled better leveraging of available resources. Newig et al. (Citation2019) examine institutional decline to explore different trajectories of decline and argue that some trajectories may indeed be productive. When actors have the flexibility to adapt during a crisis and/or the ability to reflect and learn from their situation, develop creative solutions, or actively manage the decline, the ‘death’ of a CGR may be still be beneficial (Newig et al., Citation2019).

This paper builds on existing theoretical frameworks to elaborate an empirically-based understanding of the longitudinal dynamics of CGRs. We apply a modified grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2007) to a dataset of collaboration case studies to derive patterns regarding how often CGRs persist over time, how different components of CGRs evolve, what conditions support or hinder this evolution, and how different developmental trajectories lead to differences in the outputs and outcomes.

Methods

This research uses the Collaborative Governance Case Database (Douglas et al., Citation2020), which aggregates information on the starting conditions, process, and outcomes of 39 case studies representing a mix of CGRs across countries and policy domains. As explained in the introduction to this special issue, for each case a datasheet was compiled of case descriptions and Likert-scale variables drawing on Ansell and Gash (Citation2008) and Emerson and Nabatchi (Citation2015a)’s theories of collaborative governance; cases were submitted on a volunteer basis, often by the authors of the original published case studies. From the full database, we limited our analysis to cases where the datasheet: 1) had high-quality data, exemplified by few missing values and strong-to-high confidence in reported data; 2) examined a collaboration with diverse actors (to match our definition of collaborative governance); and 3) described the case dynamics over an extended period of time to match our focus on developmental processes. This yielded a sample of 21 cases from the full database of 39 ().

Table 1. Developmental trajectories of CGRs in the database

Geographically, our sample is confined to the Western, developed context, with 11 cases in the United States or Canada, 7 in Europe, and 3 in Australia. The majority of cases (12) focuses on environmental policy, followed by social/employment policy (5). 20 cases were local or regional in scale, and one was national. The cases vary substantially in their lifespan. Approximately ⅓ of the cases lasted less than 10 years, ⅓ between 10 and 20 years, and ⅓ over 20 years. The median lifespan was 13.2 years, with a minimum of 0.2 years and a maximum of 60.2 years (with the assumption that ongoing collaborations ‘ended’ in March 2019, when cases were entered into the database; these numbers thus constitute truncated minimum estimates). Researchers’ data captured a median of 6.0 years of collaboration, with a minimum of 0.2 years and a maximum of 49.0 years.

To generate observations about how CGRs evolve over time, we use a modified grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2007) in which we use existing literature to identify broad categories to assess (e.g. how a CGR is initiated or the importance of leadership) and then draw on the database to develop more nuanced observations about characteristics of each category and interactions between them. The analysis draws on both qualitative and quantitative data captured in the database. First, we use the qualitative case narratives to identify patterns in trajectories within and across cases. Second, we explore the quantitative data derived from Likert scale questions on the case datasheet by calculating basic descriptive statistics and graphical depictions of how individual variables evolve over time, as well as by constructing basic indices representing broader concepts describing CGRs. We additionally use Spearman’s rank correlations to explore the relationship between multiple variables. In our analysis, we focus on both overarching developmental trajectories and the evolution of the collaborative process, leadership, accountability, and outputs and outcomes over time.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the dataset. First, these cases are not representative of all collaborative governance processes as they were not systematically nor randomly selected for inclusion, and the data itself is reported by individual authors without any assessment of intercoder reliability. Thus, there are inherent biases built into the data, both in how reliably they represent the ‘quality’ of collaboration in each CGR and in their ability to represent the suite of CGRs that exist globally. The cases we compare across also have very different lengths and contexts. The trajectory of a two-month disease outbreak network and a multi-decade watershed group are very different, despite the data for both being reported for ‘start, middle, and end’ time periods.

Given these limitations, our research aims are purely exploratory. We aim to generate an initial empirically-based understanding from a medium-n set of cases about how CGRs evolve over time – a topic about which there is minimal existing research.

Results

Developmental trajectories

We first assess the developmental patterns of CGRs–how they start and then change over time. provides an overview of the cases in our dataset and their general trajectories. A core question related to the activation of CGRs is the extent to which they are self-initiated or driven by some type of external actor or higher order set of rules (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Imperial, Citation2005). About half (10) were self-initiated and the other half (11) were externally initiated. However, the qualitative data suggest that there are two distinct types of self-initiated cases, based on the level of external constraints placed on the CGR. Many of the self-initiated CGRs emerged with few constraints on their collaborative process; these aimed to protect a place (e.g. Lake Tahoe, Friends of Redington Pass) or to solve a problem (e.g. Foodborne disease outbreak, Steering Committee to Reduce Family Violence). Others emerged to provide a collaborative solution to what otherwise might have been a conflict-riddled regulatory process (e.g. Desert Tortoise Habitat Conservation Planning, Baker River Hydroelectric Project) or as a self-initiated response to solve a local problem such as the use of a vacant building (e.g. Community Enterprise Het Klokhuis). This latter group had to grapple with some external constraints such as requirements imposed through a regulatory process like the U.S. Endangered Species Act or Federal Power Act and/or requirements imposed by a local government authority. The data thus suggest two categories of self-initiated processes: those with and without external constraints.

Likewise, for the 11 externally-initiated cases, the qualitative data suggest that there are two distinct categories of externally-initiated CGRs: mandated and incentivized. The first is the product of an external mandate that required a collaborative process be used to address a problem. There are many different types of mandates. The Hase Area Cooperation emerged as a response to the EU’s Water Framework Directive, and the Revitalization of Central Dandenong was initiated by the regional government in Victoria, Australia. Local government authorities also mandated collaborative processes in Stockholm, Sweden (Neighborhood Renewal Program) and Gentofte, Denmark (Collaborative policy making committees). In each case, the external mandate imposed rules that shaped the collaborative process. The other group of externally initiated cases emerged as a voluntary response to a set of incentives provided by a higher-level government authority. Four cases involved watershed planning under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program (Inland Bays, Narragansett Bay, Tampa Bay, Tillamook Bay). As a result of getting planning funds, these processes had to use a committee structure called a management conference, engage in consensus decision making, and develop a comprehensive plan, but individual CGRs still had substantial flexibility and very different collaborative processes emerged. The Homelessness policy development in Vancouver, Canada was one of many collaborations that emerged in response to incentives provided by the federal government that provided federal resources to develop a plan and the promise of additional funds to implement the plan.

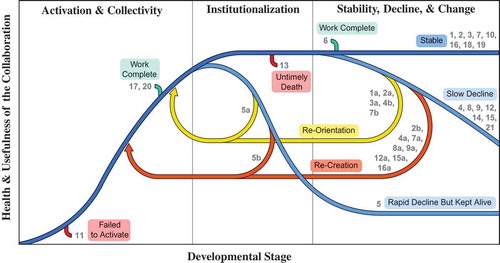

As for how the cases evolved over time, the 21 cases illustrate that a wide range of developmental trajectories can occur in CGRs. plots these general trajectories (summarized in ), drawing on the qualitative and quantitative data from the dataset to make a general estimate of the health and usefulness of the CGRs over time. The developmental stages – activation/collectivity, institutionalization, and stability/decline/change – are derived from Imperial et al. (Citation2016) (as described in the introduction).

Figure 1. Lifecycle trajectories. Numbers refer to the cases in.. Developmental stages follow Imperial et al. (Citation2016)

After activating and institutionalizing, eight CGRs converged on a relatively stable institutional structure that endured for a considerable time, remained relatively unchanged, and sustained a relatively healthy and useful life (e.g. Homelessness policy development, Area C, Community Enterprise Het Klokhuis). Seven CGRs produced a stable structure that persisted, but when viewed over time, had a relatively slow decline in usefulness, as measured by their ability to continue producing outputs and outcomes (e.g. Tillamook Bay, Hase Area Cooperation). One case (Narragansett Bay) had a rapid decline in usefulness but managed to secure resources to survive as a collaboration.

There were also numerous examples of change – reorientations and recreations – that occurred in both healthy and unhealthy processes, matching the pattern predicted by Imperial et al. (Citation2016). Reorientations involve relatively rapid and discontinuous changes in rules that alter the character of the network’s structure and processes in some tangible way. In , they are represented by the yellow line returning to the initial stage because participants make new decisions regarding the rules used to structure the CGR. Five cases reported some minor changes that occurred at least once in their collaborative process in response to some sort of need to address a new problem or improve the health and usefulness of the CGR. In two cases, the reorientations occurred as an attempt to address rapid declines in the health and usefulness of their collaborative processes (Lake Tahoe and Narragansett Bay). Most reorientations consisted of introducing new members or refining goals. This is consistent with prior research that suggests that reorientations occur for various reasons such as dissatisfaction with the perceived return on investment in network processes, the emergence of new priorities, a shift in purposes, the loss of valued network members (or their resources), or excessive turnover that causes network members to question prevailing norms, values, or the network’s way of doing things (Imperial et al., Citation2016).

Recreations, which involve a much larger shift in the core values or purposes of the CGR (Imperial et al., Citation2016), were equally common. These are indicated by the orange line; changes are larger in scope and take longer to achieve than reorientations because members must negotiate rule changes that modify their institutional infrastructure. Eight cases involved some sort of recreation, including changes in shared rules, significant core members, values, purposes that motivated participation in the prior structure, and branding. The data suggest three general and possibly interrelated reasons that recreations occur. Some recreations occurred following a shift in purpose, best exemplified by the fact that the institutional infrastructure needed to develop a plan often needed to be reconfigured to better accommodate the purposes associated with implementing a plan. For example, it was common for participants to find that the collaborative process used to develop a plan was not going to be useful for implementing said plan; they then developed a new structure to oversee its implementation (e.g. Blackfoot Challenge, Inland Bays). Similarly, once the Baker River Hydroelectric Project successfully obtained an operating license, it transformed itself into a new arrangement for implementation. In other cases, the recreation occurred as part of the institutionalization process as participants developed new collaborative organizations to enhance their ability to work together. For example, Friends of Redington Pass and Blackfoot Challenge formed section 501(c)3 nonprofit organizations while Tampa Bay formed a binding interlocal agreement. Lastly, in two cases (Narragansett Bay and Tillamook Bay), recreations occurred in response to rapid declines in the health and usefulness of the CGR.

Finally, the cases illustrate that CGRs end for a variety of reasons and at a variety of stages in the life course. One collaboration failed to progress beyond initial stages of activation (Container Deposit Legislation). One case appears to have suffered an untimely death when a shift in political parties ended the mandated collaborative process (Neighborhood Renewal Program). Two collaborations completed their work relatively quickly, arguably never progressing into a fully institutionalized CGR (Foodborne disease outbreak and Collaborative policy making in Gentofte, Denmark). Another took longer to finish its work and had an institutionalized process before completion (Desert Tortoise Habitat Conservation Planning).

Relating developmental trajectories to process dynamics

To begin understanding what factors shape these developmental trajectories, we next review qualitative and quantitative evidence on longitudinal evolution (or lack thereof) of CGRs’ collaborative processes, leadership, and accountability, and relate these features to initiation type and developmental trajectory.

Collaborative process

Collaborative governance distinguishes itself from other governance arrangements by its interactive engagement of diverse participants in addressing shared problems, challenges, and/or opportunities. Collaboration is essentially understood as the process by which participants co-labor or work together. This involves several behavioral, relational and functional components (Emerson, Nabatchi, & Balogh, Citation2012). Here we focus on specific behavioral elements identified by practitioners and scholars alike, including face-to face dialogue, engaging in single forums, joint fact finding, knowledge sharing, aligning of interests and values, joint problem solving, and focusing on immediate and/or strategic tangible outcomes (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Huxham, Citation2003).

We first consider whether the frequency of or investment in these process elements changed over time (). ‘Start’, ‘middle’, and ‘end’ refer to three time points collected by the Collaborative Governance Case Database coding sheet; cutoffs between these are defined by the individual contributors of each case, so are not consistent across cases. Importantly, more than 50% of individual cases had no change across time periods for these variables. That collaborative dynamics are relatively stable despite changes in the structure or goals of the collaboration reinforces the core role that features like face-to-face dialogue, shared interests, and joint problem-solving play in CGRs (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b).

Table 2. Reported mean process characteristics over time, standard deviation in parentheses

Mean responses to the eight process questions tended to remain steady over time or show a slight decrease toward the end period. Alignment of interests and values, joint problem solving, and the focus on intermediate outputs increased slightly from the start to middle; frequency of face-to-face engagement, joint fact finding, and knowledge sharing decrease from middle to end. These preliminary trends confirm best practice guidance in the initial period and the expected diminution in the second period of intense collaborative deliberation when task differentiation and implementation actions occur.

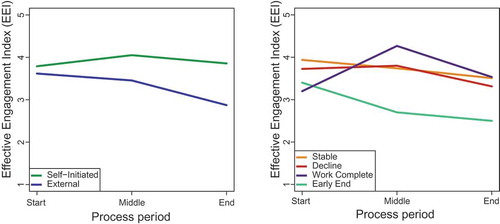

To assess the relationship between process characteristics and developmental trajectory, we created an Effective Engagement Index (EEI), which combines five process variables (face to face dialogue, joint fact finding, knowledge sharing, alignment of interest and values, joint problem-solving) (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.85). plots the mean EEI over time. The left panel disaggregates by initiation type (self-initiated versus external),Footnote2 and right by trajectory.

Figure 2. Mean trajectories of EEI, disaggregated by initiation type (left) and developmental trajectory (right)

At the start, EEI was similar for both self-initiated and externally-initiated CGRs, but EEI declined over time in externally-initiated CGRs. This suggests that self-initiated CGRs show more characteristics of robust collaborative governance – i.e. deliberative, shared decision-making – than externally-initiated ones. As for trajectory, EEI in CGRs that completed their work peaked in the middle period, and CGRs that ended prematurely had a lower focus on EEI by the middle and end stage. This suggests that the relative abundance or lack of collaborative engagement contributed to their success versus demise. CGRs that were both stable in usefulness and those with a decline had relatively constant levels of EEI over time. This perhaps contradicts Emerson and Gerlak’s (Citation2014) proposition about the importance of shared learning and shared access to resources in enabling adaptation, as cases that declined show similar trends as those that stayed stable.

Leadership

Leadership is recognized to be a key factor in initiating and sustaining collaboration (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Crosby & Bryson, Citation2005; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Page, Citation2010). Leadership can play many different roles, from catalyzing the group to work together and convening stakeholders, to stewarding the process and protecting its integrity, to mediating conflicts between stakeholders, to providing technical problem-solving expertise (Ansell & Gash, Citation2012; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Ryan, Citation2001). Likewise, effective leadership can help frame the agenda of the collaboration, structure deliberation, and manage power imbalances (Page, Citation2010). Leadership is therefore critical for helping collaborations achieve their goals.

In our cases, leadership varied from being concentrated in a single actor/organization, to shared among a few, to being distributed across all involved organizations. Over time, the locus of leadership tended to remain steady or expand (from one organization to a few, or from a few organizations to all organizations) over the course of the CGR’s work, with 9 cases expanding, 2 contracting, and 10 remaining steady. This suggests that leadership was becoming more distributed across actors, better aiming toward the distributed power model of collaborative governance. Considering trends by initiation type () shows that both externally- and self-initiated CGRs demonstrate the tendency toward expansion, but that a greater proportion of self-initiated cases have shared leadership.

Interestingly, for the longer cases in our sample (over 20 years), the locus of leadership tended to trend more toward sharing across all involved organizations than for shorter CGRs. This suggests that it may take more time for shared leadership to emerge.

The reported effectiveness of leadership tended to vary across the case trajectory (). From the start to midpoint, case leadership increased in how effective they were in both bringing together relevant actors, in guarding the focus and integrity of the collaboration, and in creating opportunities for creative problem-solving. Leadership was initially steady in its ability to resolve or mitigate conflicts over time. However, from the midpoint to the end, leadership declined in effectiveness across all four variables. This suggests first that it takes time for leadership to become effective and second that effective leadership may be difficult to sustain toward the end of long collaborative processes. Alternatively, toward the end of a process, rules and processes may be well enough institutionalized that leadership is no longer as necessary.

Table 3. Reported mean leadership quality over time, standard deviations in parentheses

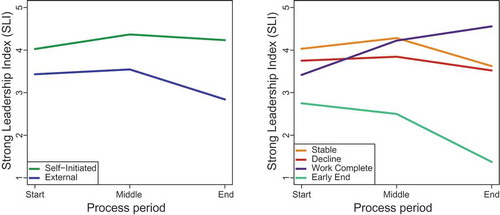

The Strong Leadership Index (SLI) combines the four leadership items () (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.89). plots SLI over time, disaggregating by initiation type (left panel) and developmental trajectory (right). Self-initiated CGRs have consistently higher ratings of leadership than externally-initiated; externally-initiated CGRs also show a decline in leadership toward the last period. Regarding developmental trajectory, the patterns are similar to EEI (). The stable and declining CGRs both have relatively stable levels of leadership over time, suggesting that leadership is not the key factor in driving stability versus decline. However, CGRs that terminated early have quite low leadership in the last period and CGRs that completed their work show an increase in leadership, suggesting that leadership does matter for successful implementation and/or keeping CGRs alive.

Accountability

Accountability refers to a set of mechanisms designed to make sure promises are kept, duties performed, and compliance is forthcoming. It implies that the person or entity being held accountable has an obligation or responsibility to an authority, group, standard, or mandate external to the individual or organizational entity. In the case of CGRs, leadership and authority are distributed, making accountability more challenging to achieve. Thus, a CGR should be simultaneously accountable to the broad constituencies with a stake in the problem or policy and to more traditional hierarchical political actors (Behn, Citation2001; Weber, Citation2003).

There are many different paths toward accountability. Because democratic public policy is ultimately the product of political demands from various interests, one path toward accountability is ensuring transparency and reporting/communication to hierarchical political actors and key constituencies (Marantz & Ulibarri, Citation2019; Pozen, Citation2018). Accountability also entails that a collaboration is meeting its objectives, first via the articulation of goals (e.g. to develop a plan or policy), then via the operationalization of those goals (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b). Lastly, in order to measure compliance and performance, accountability also requires monitoring of substantive policy objectives and regulatory standards (Bardach & Lesser, Citation1996). In cases of collaboration, these goals should be articulated and implemented by a broad cross-section of stakeholders.

shares reported trends in four accountability variables over time: the extent to which (1) the CGR was transparent, (2) joint goals were articulated, (3) these joint goals were operationalized, and (4) there was monitoring to ensure compliance with goals. Here, we see a similar pattern to leadership effectiveness, wherein reported accountability increases between the start and middle periods and then decreases. The exception, however, is monitoring of goals, which increases consistently through the end phase.

Table 4. Reported mean accountability over time, standard deviations in parentheses

As with leadership, these data suggest that accountability takes time to build. The decrease in the end period suggests either that accountability is challenging to sustain over long times or that, once attained, it plays a less central role for mature (end-stage) CGRs.

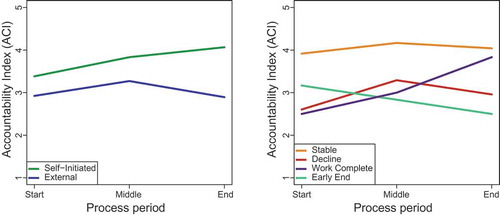

The Accountability Index (ACI) combines goal articulation, goal operationalization, and monitoring (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.78). displays mean ACI over time, disaggregated by initiation type (left) and developmental trajectory (right). Regarding initiation type, self-initiated CGRs are again consistently higher in perceived accountability than externally-initiated, and show an increase in accountability over time. Regarding trajectory, stable CGRs have the highest ACI of all trajectories, suggesting that accountability may be a key feature in driving a CGR’s ability to sustain performance over time.

Outputs and outcomes

One of the core questions of CGR performance is the extent to which they produce outputs and outcomes – whether they achieve some benefits for society (Koontz & Thomas, Citation2006). Outputs and outcomes of collaborative governance span multiple dimensions, from the substantial policy or plan at hand and its implementation, to societal consequences like conflict resolution, social learning and capacities, or the proliferation of legitimacy (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015a; Koontz, Jager, & Newig, Citation2020). Collaboration may contribute to these outcomes, e.g. by facilitating plan and policy development and improving the effectiveness and efficiency of those (Beierle & Cayford, Citation2002; Ulibarri, Citation2015), by spurring innovation and novelty (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2014; Sørensen & Waldorff, Citation2014), or increasing effective service-delivery (Chen & Graddy, Citation2010; Schalk, Citation2017).

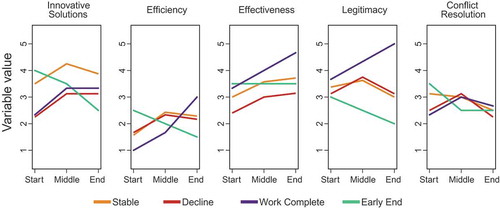

Here, we aim to see how outputs and outcomes are shaped by a CGR’s developmental trajectory. We focus on 5 specific outcomes: whether they created innovative solutions, increased efficiency, increased effectiveness, increased legitimacy, or resolved conflicts.

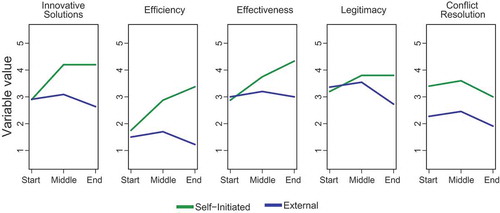

First, we consider whether the initiation type affects the different outcome qualities, as it can be assumed that processes might be initiated out of distinct rationales, focusing on specific goals. Indeed, we can observe rather distinct trajectories when it comes to effective and efficient problem-solving (see ). While all processes have a similar record of achieving each outcome at the start, self-initiated processes increase their achieved outcomes over time, while externally-initiated CGRs are flat toward the midpoint and then decrease in the end stage. The only exception is conflict resolution, for which self-initiated CGRs are consistently higher performing, but both initiation types show a decrease over time. These differences may be due to a relative absence of conflict or greater shared willingness to reduce conflict in self-initiated CGRs.

Second, we consider the same outcome variables by developmental trajectory (). Here, we see overall similar trends for stable versus declining CGRs, with the highest gains in innovative solutions, efficiency, and legitimacy in the middle phase. The stable CGRs have higher perceived innovation and effectiveness than CGRs that declined over time, but do not outperform on the other outcome dimensions. Early-ending CGRs have a decline in outcomes over time, suggesting that low performance contributed to their premature end. CGRs that completed their work increase over time, suggesting that they worked toward a successful peak of performance.

Lastly, we set the temporal dynamics of process characteristics–engagement, leadership, and accountability–into relation with the outputs and outcomes reported in different phases. shows the Spearmen’s Rho correlation between the Effective Engagement Index (EEI), Strong Leadership Index (SLI), and Accountability Index (ACI) in a particular phase with outcomes in that and subsequent phases. Numeric correlations are reported in .

Table 5. Correlations between process and outcome variables across time periods

EEI in the start period correlates moderately with building innovative solutions and legitimacy in the start and middle periods, but no variables at the end phase. SLI in the starting period is not significantly correlated with any outcome variable across any time period. ACI at the start correlates strongly with creating innovative solutions in both the start and middle periods.

Turning to the middle period, we again see a strong correlation between EEI and legitimacy in the current and subsequent phase. Middle-phase SLI is correlated with creating innovative solutions at the end. ACI also begins to play a stronger role in the middle period, being significantly correlated with innovative solutions and conflict resolution.

Finally, all three process variables (EEI, SLI, ACI) have significant effects across multiple outcomes in the end period.

The analysis also reveals two broader trends: First, relationships between process characteristics and outcomes are most prevalent within the same process phase; put differently, effective engagement, strong leadership, or accountability in early phases appear only weakly correlated with outcomes in subsequent phases. Second, effects become stronger towards the middle and end. Collectively, these observations suggest that early efforts to enhance process characteristics, leadership, and accountability do not pay off until much later in the developmental process. In other words, these variables require a sustained and accumulated effort over some period of time to remain ‘useful’ for enhancing outputs.

Discussion

This paper identifies developmental patterns for collaborative governance regimes that include both the overarching trajectory of the collaboration and its individual components. Drawing on 21 cases from the Collaborative Governance Case Database, we highlight the various pathways and trajectories these CGRs took. While several cases experienced a rather linear development from their initialization to stabilization and institutionalization, most cases followed a curvier path involving instances of re-orientation, re-creation, and/or decline.

These trajectories were mirrored in our temporal analysis of process characteristics. Many of the variables peaked at the midpoint, including collaborative process, leadership, accountability, and outputs/outcomes. On one hand, these results suggest that CGRs take time to unfold and enter functional work mode; on the other, even stable and healthy collaborations incur some decline in their usefulness while others may fall into a steady period of decline reflected in reduced meetings, scope of activity, or a narrowing of ambitions or purposes over time.

Together, these insights draw a nuanced picture regarding CGRs’ temporal development. The activation phase is often characterized as a turbulent time, subject to unstable membership and uncertain roles and objectives (Imperial et al., Citation2016). Given these challenges during the early phase, focus on outcomes appeared the weakest, and our cases displayed the most centralized levels of leadership, executed by only one or a few people. Failure to activate is a realistic threat in this early phase, as one of the cases demonstrated. After this initial phase, a working mode may be reached, where collaboration among remaining members intensifies, leadership is spread more widely and becomes more effective, and effective problem-solving plays a larger role. Additionally, measures for ensuring accountability and transparency peak during this phase. Finally, in the end phase, we observed declining ratings for most of our variables. Turnover of participants may be one major driver for this tendency. CGR members can experience ‘burnout’ because of the energy and commitment they put into roles (Huxham & Vangen, Citation2000). Once stability is achieved, participants may feel it is safe to ‘pass the baton’ and let others represent their organization. Members and support staff also move jobs, get promotions, and retire that can disrupt processes and lead to high levels of turnover (Scott et al., Citation2020). New members may eventually dominate network membership and their level of personal commitment and priorities may be quite different than the founding members. Structurally, CGRs may change their focus and rationale, especially if initial goals have been reached; mission drift may occur due to incremental shifts in the network’s programmatic focus as members chase scarce resources or funders change priorities (Auer, Twombly, & de Vita Citation2011). After the excitement and challenge of initial formation wears off, the likelihood of social loafing or freeriding increases (Wageman, Citation1999). Our results additionally suggest that the declining effectiveness of leadership and attention to accountability in the end phase may also contribute to this general decline in CGRs.

However, our study reminds us that these declines in health later in the developmental process need not be viewed solely as a negative, undesirable dynamic. Collaborations transform and end for many different reasons; they may simply finish their work or they may ‘fail’ to garner the support or resources needed to start or continue. Decline, and ultimately the ‘death’ of a CGR may indeed free resources and make room for alternative fora or institutions when the CGR is no longer useful for addressing the targeted problems or when it loses its legitimacy. By acknowledging this, we can begin to understand how to better anticipate and manage their decline (Newig et al., Citation2019). Indeed, many CGRs need not last forever.

In addition to these wider tendencies, this research reinforces the importance of contextual conditions for the trajectories of CGRs. This became particularly apparent in our analysis of initiation type and process duration and their influence on the characteristics and performance of CGRs (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b). Self-initiated CGRs had higher reported levels of effective engagement, leadership, and accountability, and achieved higher levels of outputs and outcomes achieved. Further, we could observe that leadership patterns evolved quite differently depending on process duration, with longer CGRs (<20 years) allowing for more shared leadership in the end phase.

Taken together, these findings echo recent calls for a context-sensitive understanding of CGRs (e.g. Newig et al., Citation2018) and extend these further in a temporal dimension. CGRs not only vary from instance to instance, but are further subject to considerable internal dynamics that evolve throughout their lifecycle. For example, we observed considerable change in the role and effectiveness of leadership over time. Despite the critical role leadership plays in initiating collaborations (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008; Crosby & Bryson, Citation2005; Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b; Page, Citation2010), leadership did not reach its full effectiveness until the midpoint of the collaboration – simply having leaders in place does not ensure that they will be effective in stewarding or mediating the collaboration. Similarly, we found a delayed relationship between accountability and legitimacy over time, with the correlation between these two being much more pronounced in more mature CGRs. Accountability also appeared to be a key factor shaping a CGR’s tendency toward stability versus decline over time.

For managers and decision-makers, our findings suggest that an explicit consideration of changing temporal dynamics may be beneficial for the health and effectiveness of CGRs. Specifically, we highlight that a fixed process design and early investments in leadership and accountability are not enough to sustain a healthy CGR over time. Instead, a conscious temporal perspective may involve periodic reflection on the state and dynamics of the CGR, the active formulation and reconsideration of priorities and milestones, and the adjustment of main process features such as engagement, leadership and accountability. Such explicit periodic reflection and adjustment appears particularly pertinent for externally-initiated CGRs given their more pronounced decline towards the end when compared to self-initiated processes. This finding highlights that the initiation and management of CGRs is not a single act but a continuous process. Hence, authorities or policies mandating or incentivizing collaboration may benefit from including this longitudinal perspective, supporting periodic evaluations, adjustments and transformations. Finally, a temporal perspective may also include a strategy for deactivating a CGR when its usefulness begins to wane and decline appears irreversible or would require a significant investment in shared resources. There are many reasons this can occur, such as effectiveness and legitimacy are lacking, overall benefits are decreasing or are no longer worth the cost, or if goals are reached. Indeed, there are many situations where deactivating a CGR would allow those shared resources to be utilized for more productive public purposes.

Conclusion

As an exploratory study, this paper developed new empirically-based ideas about how CGRs and their components evolve over time. However, it is important to recognize several limitations of our data and analysis. First, the case reports are all third-party reports, usually written by the authors of an original study and drawing on a variety of data sources (Douglas et al., Citation2020). Every case has a different reporter, and it is likely that each variable is interpreted uniquely based on the authors’ perspective. While reporters were asked to rate their confidence in answering questions, they are single reporters and cannot benefit from multiple coders or methods to assure inter-coder reliability. Another observer might rate legitimacy or leadership quality drastically different for the same case. Second, with few exceptions, we have considered the three reported time points (start, middle and end) as equivalent across cases. However, those cutoffs were determined by the case authors and are not standardized. The cases themselves also cover drastically different durations, from less than a year to multiple decades. Comparing the ‘start’ of a 20-year process is very different than a five-year process, and they are unlikely to be equivalent. The cases also initiated and evolved in very different contexts, which shape people’s motivation to collaborate, access to resources, and numerous other features that affect the quality of collaboration (Emerson & Nabatchi, Citation2015b); our assessment could not capture all the nuances of context. Lastly, as noted in , a number of ongoing cases were truncated in March 2019; these CGRs are continuing to operate and evolve, so our analysis has not captured the full trajectory of these cases. However, all of the ongoing cases do appear to have reached a level of institutionalization (they are not still in a developmental phase), and many of them have undergone various reorientations or recreations. Even though they are still evolving, our observations about the developmental trajectories still hold.

Despite these limitations, many of the findings noted above are consistent with the growing body of scholarship on CGRs. However, this work suggests that the field needs a better accounting of how CGRs develop, sustain, evolve, and decline over time. To conclude, we propose a series of research questions whose answers will improve our understanding of the longitudinal dynamics of CGRs and their performance over time.

How can we ensure successful activation and management of CGRs over time?

What factors lead a CGR to achieve stability versus enter other trajectories?

How do collaborative leaders or participants identify the need for reorientations or recreations, and how can they successfully manage these changes?

Is decline inevitable, or could adjustments in leadership, accountability, and process dynamics stave off premature endings?

Is formalization of long-standing CGRs inevitable? How do successful CGRs maintain the early benefits of flexibility, adaptation, and responsiveness in the face of demands for formalization and specialization?

How can useful strategies for intentional, productive ending of CGRs be identified?

While we offered a first, exploratory appraisal of these questions, building on the emergent potential of the Collaborative Governance Case Database may provide an important and promising avenue for pursuing these further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicola Ulibarri

Nicola Ulibarri is Assistant Professor of Urban Planning & Public Policy at the University of California, Irvine.

Kirk Emerson

Kirk Emerson is Professor of Practice in Collaborative Governance at the University of Arizona School of Government and Public Policy with joint appointments in the Schools of Planning and Public Health.

Mark T. Imperial

Mark T. Imperial is an Associate Professor and Director of the Master of Public Administration (MPA) Program in the Department of Public and International Affairs at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Nicolas W. Jager

Nicolas W. Jager is a postdoctoral associate in Ecological Economics at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg.

Jens Newig

Jens Newig is Professor of Governance and Sustainability and head of the Institute of Sustainability Governance at Leuphana University Lüneburg.

Edward Weber

Edward Weber is Ulysses Dubach Professor of Political Science at Oregon State University.

Notes

1 The term ‘lifecycle’ is often used to depict stage-specific linear developmental patterns in group and organizational settings (Quinn & Cameron, Citation1983; Smith, Citation2001). Nonlinear patterns of development, like punctuated equilibrium (Gersick, Citation1988) and complex open adaptive systems (McGrath, Arrow, & Berdahl, Citation2000), have been identified as well. CGRs, of course, as interorganizational arrangements, differ in marked ways from work groups and formal organizations. Here, in line with our exploratory, inductive analysis, we refer to the developmental dynamics of CGRs as life courses or trajectories, avoiding any theoretical claims about sequential or nonsequential developmental patterns.

2 For this and following figures, we use two categories of initiation type – self and external – rather than the four introduced in , as the results are more straightforward when comparing just the two categories. In general, self-initiated CGRs of both types perform better than externally-initiated CGRs of both types.

References

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2012). Stewards, mediators, and catalysts: Toward a model of collaborative leadership. Innovation Journal, 17(1), 2–21.

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2014). Public innovation through collaboration and design. London: Routledge.

- Auer, J. C., Twombly, E. C., & de Vita, C. J. (2011). Social service agencies and program change. Public Performance & Management Review, 34(3), 378–396. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576340303

- Bardach, E., & Lesser, C. (1996). Accountability in human services collaboratives—For what? And to whom? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 6(2), 197–224. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024307

- Behn, R. D. (2001). Rethinking democratic accountability. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press.

- Beierle, T. C., & Cayford, J. (2002). Democracy in practice: Public participation in environmental decisions. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- Chen, B., & Graddy, E. A. (2010). The effectiveness of nonprofit lead-organization networks for social service delivery. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 20(4), 405–422. doi:10.1002/nml.20002

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Crosby, B. C., & Bryson, J. M. (2005). A leadership framework for cross-sector collaboration. Public Management Review, 7(2), 177–201. doi:10.1080/14719030500090519

- Douglas, S, Ansell, C, Parker, C, Sørensen, E, Hart, P. T, & Torfing, J. (2020). Collaborating on collaborative governance research: introducing the collaborative governance case databank. Policy & Society.

- Emerson, K., & Gerlak, A. K. (2014). Adaptation in collaborative governance regimes. Environmental Management, 54(4), 768–781. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0334-7

- Emerson, K., & Nabatchi, T. (2015a). Evaluating the productivity of collaborative governance regimes: A performance matrix. Public Performance & Management Review, 38(4), 717–747. doi:10.1080/15309576.2015.1031016

- Emerson, K., & Nabatchi, T. (2015b). Collaborative governance regimes. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., & Balogh, S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(1), 1–29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011

- Genskow, K. D., & Born, S. M. (2006). Organizational dynamics of watershed partnerships: A key to integrated water resources management. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education, 135(1), 56–64. doi:10.1111/j.1936-704X.2006.mp135001007.x

- Gersick, C. J. G. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1), 9–41. doi:10.5465/256496

- Heikkila, T., & Gerlak, A. K. (2016). Investigating collaborative processes over time a 10-year study of the South Florida ecosystem restoration task force. The American Review of Public Administration, 46(2), 180–200. doi:10.1177/0275074014544196

- Hui, I., Ulibarri, N., & Cain, B. E. (2018). Patterns of participation and representation in a regional water collaboration. Policy Studies Journal. doi:10.1111/psj.12266

- Huxham, C. (2003). Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Management Review, 5(3), 401–423. doi:10.1080/1471903032000146964

- Huxham, C., & Vangen, S. (2000). Leadership in the shaping and implementation of collaboration agendas: How things happen in a (Not quite) joined-up world. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6), 1159–1175. doi:10.5465/1556343

- Imperial, M. T. (2005). Using collaboration as a governance strategy: Lessons from six watershed management programs. Administration & Society, 37(3), 281–320. doi:10.1177/0095399705276111

- Imperial, M. T., Johnston, E., Pruett-Jones, M., Leong, K., & Thomsen, J. (2016). Sustaining the useful life of network governance: Life cycles and developmental challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(3), 135–144. doi:10.1002/fee.1249

- Koontz, T. M., Jager, N. W., & Newig, J. (2020). Assessing collaborative conservation: A case survey of output, outcome, and impact measures used in the empirical literature. Society & Natural Resources, 33(4), 442–461. doi:10.1080/08941920.2019.1583397

- Koontz, T. M., & Thomas, C. W. (2006). What do we know and need to know about the environmental outcomes of collaborative management? Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 111–121. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00671.x

- Mandell, M., & Keast, R. (2007). Evaluating network arrangements: Toward revised performance measures. Public Performance & Management Review, 30(4), 574–597.

- Marantz, N. J., & Ulibarri, N. (2019, January). The tensions of transparency in urban and environmental planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research. doi:10.1177/0739456X19827638

- McGrath, J. E., Arrow, H., & Berdahl, J. L. (2000). The study of groups: Past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 95–105. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_8

- Newig, J., Derwort, P., & Jager, N. (2019). Sustainability through institutional failure and decline? Archetypes of productive pathways. Ecology and Society, 24(1). doi:10.5751/ES-10700-240118

- Newig, J., Edward Challies, N. W., Jager, E. K., & Adzersen, A. (2018). The environmental performance of participatory and collaborative governance: A framework of causal mechanisms. Policy Studies Journal, 46(2), 269–297. doi:10.1111/psj.12209

- Page, S. (2010). Integrative leadership for collaborative governance: Civic engagement in Seattle. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2), 246–263. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.005

- Pozen, D. E. (2018). Transparency’s ideological drift. Yale Law Journal, 128, 47.

- Provan, K. G., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum015

- Quinn, R. E., & Cameron, K. (1983). Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Management Science, 29(1), 33–51. doi:10.1287/mnsc.29.1.33

- Ryan, C. M. (2001). Leadership in collaborative policy-making: An analysis of agency roles in regulatory negotiations. Policy Sciences, 34(3–4), 221–245. doi:10.1023/A:1012655400344

- Schalk, J. (2017). Linking stakeholder involvement to policy performance: Nonlinear effects in Dutch local government policy making. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(4), 479–495. doi:10.1177/0275074015615435

- Scott, T. A., Ulibarri, N., & Scott, R. P. (2020). Stakeholder involvement in collaborative regulatory processes: Using automated coding to track attendance and actions. Regulation & Governance, 14(2), 219–237. doi:10.1111/rego.12199

- Smith, G. (2001). Group development: A review of the literature and a commentary on future research directions. Group Facilitation, 3(April), 14.

- Sørensen, E., & Waldorff, S. B. (2014). Collaborative policy innovation: Problems and potential. Innovation Journal, 19(3), 1–17.

- Ulibarri, N. (2015). Tracing process to performance of collaborative governance: A comparative case study of federal hydropower licensing. Policy Studies Journal, 43(2), 283–308. doi:10.1111/psj.12096

- Wageman, R. (1999). Task design, outcome interdependence, and individual differences: Their joint effects on effort in task-performing teams (Commentary on Huguet et al., 1999). Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(2), 132–137. doi:10.1037//1089-2699.3.2.132

- Weber, E. P. (2003). Bringing society back in: Grassroots ecosystem management, accountability, and sustainable communities. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Appendix

Table A1. Correlations between process and outcome variables across time periods