Abstract

ABSTRACT Inclusive paediatric mobility (IPM) design is a growing field in need of critical and foundational designerly transitions in order to better deal with a wicked problem. This article adopts an illustrative mapping review method to interrogate the past 50 years of IPM design, aiming to identify alternative designerly ways that could help transition the field towards a more desirable long-term future. IPM Design contributions between 1970 and 2020 are mapped chronologically across Theoretical, Methodological, Empirical, and Interventional categories. A Reflection-for-Transition framework of Designerly Ways is developed to identify existing and alternative designerly ways, through categorizing key insights from the mapping review. The framework consists of five interrelated dimensions, including Designerly: Investigations, Processes, Contributions, Collaborations, and Contexts. Proposed alternative designerly ways include: exploring high-level narratives and social imaginaries; shifting focus towards problem-framing, child-centred design and transdisciplinarity; improved documentation and sharing to build a body of knowledge; and exploring extended design contexts.

Introduction

Before being able to effectively tackle wicked problems, designers should first reflect on and question their designerly ways (Schön Citation1983; Tonkinwise Citation2015). This article aims to reflect on and improve the current state of design practice by observing and questioning the history and heritage of designerly ways within a specific context i.e. design for inclusive paediatric mobility. Within the study of design, the term ‘designerly ways’ represents a vast and well-established body of literature, first discussed by Cross (Citation1982) in his paper ‘Designerly Ways of Knowing’, with the aim of establishing the criteria which design must satisfy in order to be treated as a coherent discipline of study. Over time, this body of literature has grown, alluding to multiple distinctive types of ‘designerly ways’ including: ‘Knowing’ (Cross Citation1982), ‘Thinking’ (Oxman Citation1999; Laursen and Møller Haase Citation2019), ‘Acting’ (Cross Citation2006), ‘Doing’ (Self, Dalke, and Evans Citation2013), ‘Researching’ (Grocott Citation2012), ‘Being’ (Tenenberg, Socha, and Roth Citation2014), and more recently, ‘Futuring’ (Joseph Citation2019). In this article, the term ‘designerly’ is used in a sense which pertains to the academic design research tradition of studying design practice and linking it to design theory, as distinguished by Johansson-Sköldberg, Woodilla, and Çetinkaya (Citation2013).

Rather than focusing on a specific type of designerly way from the outset, various designerly ways are explored and interrogated within a field-specific context; the case study of design for inclusive paediatric mobility (IPM) is chosen as an area of design which presents a wicked problem in need of designerly changes in order to transition towards a more desirable long-term future. Designerly contributions to IPM are used as a starting point to analyse design principles, practices, and techniques (Carlgren, Rauth, and Elmquist Citation2016) and curate a narrative account (Grimaldi, Fokkinga, and Ocnarescu Citation2013) of designerly ways in the field over the past 50 years. This article maps and synthesizes findings to highlight gaps, issues and patterns and to propose alternative designerly ways to improve IPM design.

Design meets childhood mobility

Inclusive Paediatric Mobility (IPM) design is the application of an inclusive design approach to create mobility interventions such as wheelchairs, walking aids and exoskeletons, with the fundamental goal of optimizing the experience of childhood. IPM design unifies various design elements and high-level approaches, making the content of this article pertinent to various neighbouring fields. Nesting within the wider field of inclusive design, IPM design draws heavily from Design Research, Child-centred Design, Design for Disability, and Mobility Design. The field is rich with technological, sociocultural and commercial considerations and inherits contradictory and permutable opinions and knowledge from a variety of disciplines, stakeholders and subject areas. The overarching problems that exist within IPM design are consequently wicked; they are ill-defined, complex, and are reframed whenever sociotechnical imaginaries transform (Taylor Citation2003; Jasanoff and Kim Citation2013) or societal narratives evolve (Venditti, Piredda, and Mattana Citation2017). For example, in the late 1970s, the widely accepted narrative used to address paediatric mobility disabilities began to evolve from the goal of ‘normalizing’ children's movement, with walking being the ultimate achievement, to the goal of encouraging children to use their ‘most efficient mobility approach’ to optimize their experience of childhood (Butler Citation2009). This directly influenced the design of ensuing IPM interventions, and highlights the importance of interrogating societal narratives when reflecting on how and why designers arrived at their end products.

The contemporary landscape of IPM design materialized shortly after this, with a breakthrough in design thinking that embodied the new societal narrative; in 1983, the first paediatric power wheelchair was designed. The stark lack of independence-promoting IPM interventions other than walking aids up until this point was simply a reflection of society’s conventionally acknowledged narratives (Wiart and Darrah Citation2002). New developments and knowledge in the field have since continued to grow, yet there remain myriad issues with the design of IPM interventions (Livingstone and Paleg Citation2014).

The ‘I’ in IPM design

Inclusive Design centres on the diversity of users' physical and psychosocial needs (Lim, Giacomin, and Nickpour Citation2021), often starting with considering ‘extreme’ users (Newell and Gregor Citation1997), before exploring how further substantial structures of intersectional disadvantages such as race, gender, income and class, come to bear on design (Konstantoni and Emejulu Citation2017). In the context of commercially available mobility interventions, young children are one of the most underserved and excluded age group of users (Feldner, Logan, and Galloway Citation2016), hence becoming ‘extreme’ users of an already ‘extreme’ group.

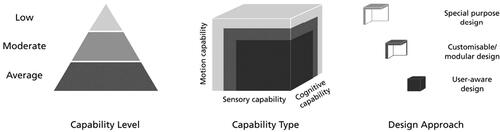

There are three predominant approaches to the application of inclusive design () and it is important to consider all three in order to build a comprehensive, accurate and critical picture of the IPM design landscape. ‘Special-purpose’ design approach caters specifically for the needs of an extreme user group without serving a mainstream market, such as wheelchairs and walking aids. ‘Customizable/modular’ design approach enables mainstream products to be adapted to cater for the needs of extreme user groups, such as ride-on toy vehicles. The ‘User-aware’ design approach considers extreme user groups in the design of mainstream products, such as supportive tricycles and go-karts.

Figure 1. Three predominantly used Inclusive Design approaches (Clarkson and Coleman Citation2015).

The significance of IPM

Mobility, as well as being a human right, is a necessary and significant part of life that, amongst children in particular, influences multiple health outcomes. Independent mobility facilitates children's physical, emotional, psychosocial, perceptual and cognitive development (Nilsson et al. Citation2011; Bray et al. Citation2020), as well as providing opportunities to make social interactions (Guerette, Furumasu, and Tefft Citation2013) and increase confidence and participation with peers in everyday activities (Casey, Paleg, and Livingstone Citation2013). For infants and children with mobility disabilities, early intervention and provision of IPM can avoid irreversible developmental delays. Using independent mobility interventions has been shown to facilitate childhood development from as young as seven months old (Lynch et al. Citation2009).

Design issues with IPM

A myriad of unresolved issues exist around IPM design, some of which act as barriers for incorporating IPM into a child’s life. Many IPM interventions are as restrictive as they are enabling, are generally viewed as ‘compromises’ rather than ‘ideals’, and often exclude children with complex needs (Livingstone and Paleg Citation2014; Feldner, Logan, and Galloway Citation2016). Furthermore, they lack up-to-date integrated and assistive technologies, let alone desirability and childhood appeal which has long been the norm in parallel sectors. Hence, problems with IPM designs can be classified under three meta-levels:

Desirability, i.e. acceptability, pleasurability, emotional durability and personal meaning (Desmet and Dijkhuis Citation2003).

Feasibility, i.e. functionality and features, technicalities and usability (Livingstone and Paleg Citation2014).

Viability, i.e. economies of scale, affordability and sustainability (Pituch et al. Citation2019).

Whilst each problem has been separately investigated and addressed within adult services Leaman and La Citation2017), there is a considerable lack of holistic, convergent and innovative thinking within paediatric services (Feldner, Logan, and Galloway Citation2016).

Design opportunities for IPM

IPM is a global need as well as a worldwide market. From the perspective of health economics, there lies an opportunity to build a case for state provision of early IPM interventions and potential funding for further research and development in the field of IPM design. Children who receive adequate developmental opportunities during early childhood have a better chance of becoming healthy and productive adults, which can reduce future costs of education, medical care and other social spending (Bray et al. Citation2020).

The combination of advanced manufacturing technologies, social product development and crowdfunding, provides a significant opportunity for continued development, full customization and viable routes to market for IPM products. Open source design platforms can save time and money on research and development, whilst providing tools to drive rapid innovation at a global scale (Özkil Citation2017). The emergence of new design approaches for solving complex or wicked problems (Tonkinwise Citation2015) presents an opportunity to seek out improved designerly ways for the future of IPM design practice. This article aims to investigate such opportunities through reflecting on and questioning the past half century of designerly ways in the field.

Methodology

Data collection methods

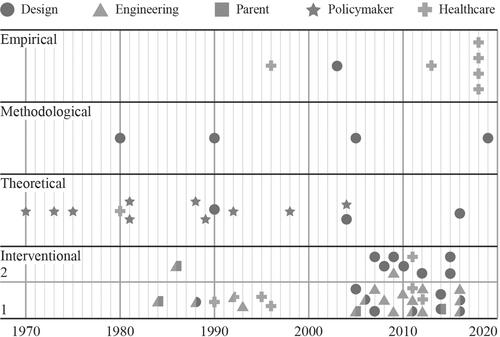

An illustrative mapping review was used to objectively categorize designerly contributions to the field of IPM as one of four types, i.e. Interventional, Theoretical, Methodological or Empirical. These four categories encapsulate all types of designerly contribution to the field of IPM (Wobbrock and Kientz Citation2016). outlines the contribution classification system.

Table 1. Classification of IPM design contributions.

Using these categories to chronologically map contributions at a high level of granularity, enables holistic visualization and analysis of the field throughout history. It also enables identification of trends, clusters, deserts and gaps in knowledge (Grant and Booth Citation2009) across all types of designerly contribution. The data collection methodology (including all utilized search strings and databases) is outlined in detail on Mendeley data (O'Sullivan and Nickpour Citation2020a) along with details of the captured contributions. It is suggested to review the aforementioned dataset before proceeding to the discussion section, in order to better engage with the analysis. Each search result was reviewed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in .

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data analysis frameworks

Contributions that met the inclusion criteria were categorized, mapped and then further analysed to enable a thorough understanding of the context of their creation and relationship to other contributions on the map (O'Sullivan and Nickpour Citation2020b). translates the objectives of this analysis into high-level questions and serves as the first of two frameworks used to structure this data analysis (O'Sullivan and Nickpour Citation2020c). The questions are used to guide further investigation into each contribution and thus facilitate exploration of designerly ways.

Table 3. Contribution analysis objectives translated into high-level questions.

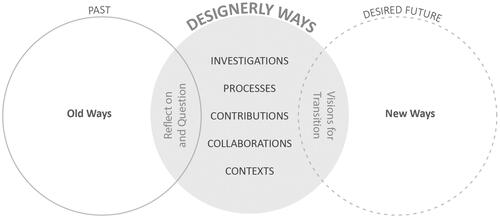

A second framework was required in order to structure the identification and discussion of deeper insights around designerly ways, and to ensure they were rigorously reflected on and questioned at multiple levels (Carlgren, Rauth, and Elmquist Citation2016). Whilst various distinctive designerly ways have been well investigated, there appears to be a lack of existing theories, models, or frameworks which specifically facilitate reflection on, and questioning of, designerly ways on a macro-level, with a long-term, and future-oriented approach. Hence, relevant frameworks were reviewed, three were identified as points of reference and were synthesized to make a single framework suitable for this purpose. Combining the works of Schön (Citation1983), Irwin, Tonkinwise, and Kossoff (Citation2020) and Aristotle (Sloan Citation2010), a new Reflection-for-Transition framework has been devised to capture and curate insights around multiple aspects of designerly ways ().

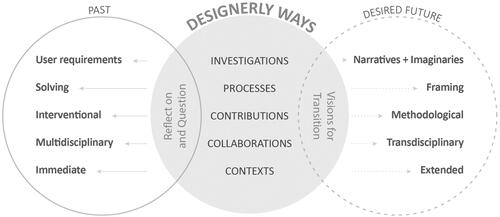

Schön’s (Citation1983) reflection-on-action approach has been adopted in this framework to retrospectively contemplate the designerly ways utilized by contributions. Adding to this, the forward-oriented reflective approach of the Transition Design Framework developed by Irwin, Tonkinwise, and Kossoff (Citation2020) has been adopted to facilitate long-term reflection at a macro-level. It also offers an action-planning aspect for new ways of designing which expands on the attitudes and actions required to reach the desired future. The final facet of the framework encapsulates Aristotle's ‘elements of circumstance’ to provide a comprehensive reflective structure for separating insights into types of designerly ways. These consist of seven questions used as a means of rigorous, contextual, and holistic information capture (Sloan Citation2010). Adopting and adapting the elements of circumstance, the new Reflection-for-Transition framework of Designerly Ways consists of five types of designerly ways, each representing an instrumental dimension in the shaping of IPM contributions. These include: Designerly Investigations (Why); Designerly Processes (How and by What means); Designerly Contributions (What); Designerly Collaborations (Who); and Designerly Contexts (Where and When). Each designerly way is to be examined in the contexts of old and new ways, according to reflections, questions and visions for transition, as illustrated in . This framework will be used as a vehicle to identify, reflect on, and question key insights in both the context of the IPM design mapping review and the wider context of design practice.

Illustrative mapping results

In total, 61 design contributions from the 1970-2020 period were deemed eligible for inclusion. Full details of these results and their references are recorded in tables on Mendeley data (O'Sullivan and Nickpour Citation2020a). The data collection results were translated into a visual map () to illustrate designerly contributions to the field of IPM based on type of contribution and contributors’ stakeholder group(s).

Questioning our designerly ways

The Reflection-for-Transition framework of Designerly Ways is used in this section to structure the discussion around 'Reflections On' old ways and 'Visions for Transition' to new ways regarding each of the five identified designerly ways.

Designerly investigations

Designerly investigations account for the ways in which designers systematically explore a subject to identify, question, and make sense of insights, in pursuit of a definition or a direction. Designerly investigations tend to occur at the earliest stage of a design process as a sensemaking or framing exercise (Dillon Citation1982) seeking to answer the question of why - to better understand and define the problem at hand.

Reflecting on and questioning designerly investigations

Examining the mapping review data confirmed that interventional contributions to the field of IPM have primarily been driven by designers' habitual solution-focused impulse to specify and satisfy unmet ‘user requirements’, as their first point of investigation. This is archetypical of the design process (Cross Citation2006) and often results in designers neglecting to interrogate higher level dominant and alternative narratives and social imaginaries around a problem, as part of the designerly investigation.

Narratives operate as an instrument of mind in the construction of reality and the way we perceive problems; they provide perspective or a point of view (Bruner Citation1991; Grimaldi, Fokkinga, and Ocnarescu Citation2013). Venditti, Piredda, and Mattana (Citation2017) describe narratives as a way of presenting interpretations of reality, going beyond time, space, aesthetic form, and medium of conveyance. Narrative and theme investigations assist in broadening perspectives and understanding of a problem, which in turn enables designers to better define and frame a problem, and thus better solve it (Leeuwen et al. Citation2020). Within each act of design, proactively or passively, designers are either approving or rejecting a high-level narrative or ideology through conforming and contributing to it, transforming, challenging, or opposing it (Jakobsone Citation2017).

Contemporary narratives put forward by Critical Disability Studies and Crip Theory around empowerment, techno-ableism, crip technoscience and design justice could help critique, alter, and reinvent the material-discursive world (Fritsch et al. Citation2019; Shew Citation2018; Costanza-Chock Citation2020). However, engagement with alternative narratives, social imaginaries, and approaches to framing IPM have remained underexplored and relatively unchanged. As a result, the landscape of IPM design has witnessed incremental changes focusing on the refinement of existing products and technologies (e.g. power wheelchairs) rather than substantial innovation or critical design.

Vision for transition and new way of designing; investigations

Designerly investigations in the field of IPM design currently tend to focus on identifying and questioning underlying requirements and specifications for a design. It is proposed that designerly investigations transition to prioritize exploration, identification and questioning of alternative narratives and social and sociotechnical imaginaries to help reframe or even redefine the problems at hand, leading to critical design practices.

Designerly processes

Designerly processes comprise the ways in which designers manage the application of their resources, including the nature and order of their actions, answering the question of how designers design (Bobbe, Krzywinski, and Woelfel Citation2016). Processes represent a fundamental design characteristic influenced by both the lens used to view a subject, and the design approach adopted by the designer. Two distinct stages of the design process include problem framing and problem solving (Dillon Citation1982). Nessler (Citation2016) illustrates these in his Revamped Double Diamond model, as two sets of aims and outcome. Priority is given to first ‘designing the right things’, which establishes a point of view and enables ‘problem framing’, followed by ‘designing things right’ which embodies ‘problem solving’.

Reflecting on and questioning designerly processes

Detailed analysis of interventional contributions illuminated a distinct spectrum of design profiles. Both ends are heavily invested in problem solving, and neglect to evidence investment in problem framing. On one end of the spectrum, exist designers who have a vested personal interest, lived experience, or social and corporate responsibility, such as family members or charities (e.g. Everard Citation1983; Flodin Citation2008). Designers at this end of the spectrum tend to have a strong point of view about the problem they are seeking to solve, or even an idea of a solution from the outset, and thus tend to jump into the design process without attempting to reframe or consider the problem from alternative perspectives.

On the other end of the spectrum, exist designers in larger commercial organizations which typically mass-manufacture adult mobility equipment. They tend to commence the design process with a closed brief or product specification that is framed from a commercial or health service provider perspective; to prioritize unit cost and physical user requirements, over children’s lived experiences and personal preferences.

The mapping review illustrated a considerable number of interventional concepts or prototypes never making it to commercialization, highlighting a disparity between design application and successful intervention or impact. With this being such a prominent characteristic of the IPM design landscape, it seems surprising that market sustainability is not framed as a higher priority design problem from the outset.

Vision for transition and new way of designing; processes

Designerly processes in the field of IPM design currently tend to commence with discovering and defining the needs of stakeholders with a solution-centred approach. Following on from designerly investigations, it is proposed that designerly processes transition their starting points from problem solving to problem framing, and incorporate the opportunity to explore alternative narratives from the outset.

Designerly contributions

Designerly contributions encapsulate the ways in which design efforts materialize to reflect what designers do on all levels. Theories, methods, interventions and empirical outcomes are all types of designerly contribution (Wobbrock and Kientz Citation2016). The way a contribution is recorded forms a critical part of its ability to be communicated or shared, and thus significantly influences its representation. As the role of designers, and the very definition of design evolves over time, so too should the types of contribution that make up designerly knowledge.

Reflecting on and questioning designerly contributions

The IPM mapping review revealed a somewhat disjointed and unbalanced landscape of designerly contributions, heavily focused on interventions. Moreover, these efforts were poorly recorded, making it difficult to locate and capture grey literature and unpublished fieldwork or artefacts, especially for discontinued interventional contributions. This could reflect an ‘end-result-oriented’ mentality that considers only certain polished aspects of a final solution valuable or worthy of being recorded, communicated, and represented (Wong and Radcliffe Citation2000). Media coverage from IPM related design projects and competitions glorify well-presented inspirational prototypes, videos, or illustrations of final products as indicators of success (Norman Citation2010) even if they never materialized or achieved impact (examples in of: O'Sullivan and Nickpour Citation2020a). Long-term measures of success, design processes, failures and empirical knowledge are typically kept in-house, if documented at all, and consequently have little or no representation as contributions. Additionally, there are no rigorous principles or measures to assess quality, guide future thinking or define success within IPM design, which leaves little foundation for new contributions to learn from and build upon.

The representation of contributions by stakeholder groups suggests that documentation and dissemination of knowledge is typically encouraged and allocated more time in academic settings than in industry. This makes it highly likely that IPM design contributions, particularly interventional ones which did not reach commercialization, could have been made by stakeholders unconnected to academia without being recorded in literature, and hence may not be represented in this mapping review.

Vision for transition and new way of designing; contributions

Designerly contributions in the field of IPM currently lack a balanced and holistic approach that recognizes the full spectrum and potential of design contributions. Contributions are predominantly focused on interventions and delivering end products, hence neglecting and lacking attempt, recognition, documentation, investment, and prioritization of other types of designerly contribution. It is proposed that the priorities for designerly contributions transition from being interventionally focused towards a more balanced representation of the spectrum of designerly contributions, placing greater value on theories, methodologies and empirical research.

Designerly collaborations

Designerly collaborations embody the ways designers engage with others throughout the design process, answering the question of who designers work with and the nature of their engagement. There is a clear distinction between concepts of consultation, collaboration, and participation (Ansell and Gash Citation2007). While participatory design and co-design are well established within design, there is strong evidence around lack of uptake, misuse, and ineffective adoption of such approaches (Keast, Brown, and Mandell Citation2007).

Reflecting on and questioning designerly collaborations

The development of 30 out of the 36 interventional contributions in the mapping review were led by engineers or designers. There is little evidence or trend of continued involvement from other disciplines, stakeholders or children (users) throughout the design process. It seems, at best, collaborations in the field of IPM design have been multidisciplinary, but designers and engineers appear to have the final say on which features are compromisable or significant enough to be included in an intervention. Evidence shows that children, parents and therapists are not always satisfied with this (Pituch et al. Citation2019). Such critique echoes arguments from within crip technoscience (Fritsch et al. Citation2019), advocating expertise or even design initiation to be shifted from designers to those with lived experience, to minimize likelihood of designs being rejected by the disability community (Shew Citation2018). In this case, utilizing a child-centred design approach would ensure children’s individual and collective voices, perspectives, priorities and lived experiences of IPM are captured and considered as a core part of the design process.

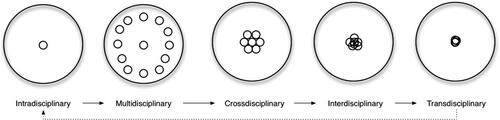

Due to the nature of the field, each stakeholder is equally knowledgeable when it comes to defining their perspective of the problems around IPM, and so all stakeholders need to be involved to frame the key questions and most important facets of the design problem. Jensenius (Citation2012) proposes a spectrum of collaborative setups () and suggests that a closer collaborative effort to not only share information, but to work together to develop solutions and ideas in a transdisciplinary approach, could transform the dynamics of IPM design and stimulate innovation in the field.

Figure 4. The disciplinary data integration spectrum (Jensenius Citation2012).

Designers can support multi-stakeholder collaboration and foster co-creativity among fellow participants by taking on the role as a participant-facilitator (Aguirre, Agudelo, and Romm Citation2017). Involving children, key stakeholders and experts from foundational subject areas could bring new perspectives and narratives to the IPM field, stimulating and altering the way interventions are imagined, and subsequently designed. It is also important to acknowledge and balance tensions between disciplines regarding narratives and requirements.

Being a field of such specific scope puts IPM design at risk of contributing to the fragmentation of knowledge through siloing its discoveries if it does not maintain strong connections and collaborations with its broader foundational subject areas and adopt a unifying approach to knowledge.

Vision for transition and new way of designing; collaborations

Designerly collaborations in the field of IPM design have typically been multidisciplinary, however this has clearly not been satisfying the requirements and desires of all stakeholders and critiques (Livingstone and Paleg Citation2014). It is proposed that designerly collaborations transition towards a more child-centred and transdisciplinary approach, with designers taking on the role of a facilitator, a sensemaker and a bridge between a breadth of disciplines and stakeholders, both in terms of narratives and requirements. This will ensure design acts as an agent of knowledge unification throughout the design process, and is led with a rich array of experiences, skill sets, narratives and definitions of the problem.

Designerly contexts

Designerly Contexts encompass the ways in which designers are influenced by factors connected with, or relevant to, the time (when) and place (where) they are designing for. Contextual sources of influence are dynamic and wide-ranging, embracing the breadths of social, technological, environmental, political, economic and legal states. As such, contextual influences manifest in a variety of forms, from deep-seated and imperceptibly evolving values, goals and interests at an individual level, to abrupt changes commanding immediate action at a global level. Having awareness of context and its influences bestows designers with greater consciousness over their design motivations (Mitchell Citation1997), inspirations (Gonçalves, Cardoso, and Badke-Schaub Citation2014), identity (Björklund, Keipi, and Maula Citation2020), thinking and choices (Gray Citation2013), all of which directly shape their design outcomes.

Reflecting on and questioning designerly contexts

The dimension of Time can be related to short-term present thinking (immediate), or long-term future thinking (extended). It is interesting, yet unsurprising, that the first IPM interventions captured in the mapping review were created by parents (Everard Citation1983; Flodin Citation2008) as urgent responses to satisfy the mobility needs of their own children. These designs hence adopted an immediate approach to time. This relates closely to the ecological perspective of Place as the level of proximity to the designer: at an individual level, designers address their own problem; at a community level designers address the problem of their connections or networks; at a national level designers address the problem of those with similar social and cultural values without direct contact; and at a global level designers address the problem at scale, for the benefit of all, crossing the borders of social and cultural values (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979). Designers at the individual level are typically proactive in creating a design brief from their own understanding or lived experience of a problem. Designers who are designing at a less immediate level, or who are given a design brief, are typically reactive to somebody else’s interpretation of a problem, making it important they unpick and interrogate the narratives, motivations, scope and any expected deliverables as part of their designerly investigation.

A more common interpretation of Place relates to geography. The mapping review highlights a significant lack of novel IPM design contributions recorded from developing regions of the world. This could be due to limitations of the search strategy, poor documentation of possible contributions, or general lack of contributions to the field of IPM design from these regions. Design for Scalability, Design for Diversity, and Context Variation by Design, are approaches and mind-sets that acknowledge large-scale wicked problems often occur in multiple contexts, and encourage designers to scale solutions across contextual boundaries (Kersten, Diehl, and van Engelen Citation2018). These approaches start by intentionally sourcing insights from across all relevant contexts to create richer, more creative solutions that are more adaptable and adaptive for scalability. This can lead to lower end-to-end costs and shorter overall timelines for adoption on a substantial scale, which can be an effective way to extend the reach of IPM designs to also suit developing regions of the world (Nickpour and O'Sullivan 2016).

Vision for transition and new way of designing; contexts

Designerly contexts in the field of IPM design currently tend to focus on the designer’s immediateness in terms of both time and proximity to the problem. It is proposed that designerly contexts transition towards more extended perspectives, thinking about the longer-term landscape of IPM and considering it from a global sustainable perspective. This transition aims to provide designers with awareness of the bigger picture of IPM design, to be alive and responsive to the struggles of others and the planet, to set the world on a path to achieving better IPM design and thus more inclusively optimize experiences of childhood.

Summary of transitions for designerly ways in IPM design

The aforementioned ‘Reflections On’ old ways and ‘Visions for Transition’ to new ways regarding each of the five identified designerly ways in the field of IPM design are summarized in . It is suggested that: Designerly investigations should change from capturing underlying requirements to first exploring high-level narratives and imaginaries; Designerly processes should shift focus from problem-solving to problem-framing; Designerly contributions should move beyond being interventionally-focused to attend more rigorously to documenting and sharing theories, methodologies and empirical research, to build a body of knowledge; Designerly collaborations should transition from multidisciplinary involvement towards transdisciplinary design teams; and Designerly contexts should progress from adopting immediate perspectives of time and place to exploring extended perspectives. Engaging in this reflective process has highlighted alternative designerly ways which could help the transition towards a more desirable long-term future for IPM design.

Conclusion and future research

This article reviewed 61 contributions to the field of IPM design between 1970 and 2020. Adopting an illustrative mapping review method, design contributions were captured and classified under Theoretical, Methodological, Empirical, and Interventional categories.

On a macro-level, a Reflection-for-Transition framework of Designerly Ways was developed to curate key insights in a critical, reflective, and future-facing manner. The framework consists of five interrelated dimensions including Designerly: Investigations, Processes, Contributions, Collaborations, and Contexts. The framework could help identify existing and alternative designerly ways in both the context of IPM design over the past fifty years, and the wider context of design practice.

On a micro-level, key issues were identified with the current designerly ways of IPM and alternative designerly ways were proposed (). These included: exploration of high-level narratives and social imaginaries prior to engaging with user and system requirements; shifting towards problem-framing, child-centred design and transdisciplinarity; attending more rigorously to capturing theoretical, methodological, and empirical contributions to build a foundational body of design knowledge; and exploring extended contexts.

Going forward, the Reflection-for-Transition framework of Designerly Ways could be applied in other domains (both closely related and distant from IPM) as a framework to help capture context-specific insights, and as a framework to reflect on and transition the wider context of design practice as a whole.

Furthermore, future research needs to explore how each of the proposed new designerly ways should be applied in IPM design practice, in order to equip the next generation of designers with the tools, processes and knowledge required to drive progress, accelerate learning, and reimagine a more desirable future for IPM. Future design research in the field should prioritize establishing a more rigorous problem framing process, which will primarily entwine aspects of research into designerly investigations, processes and collaborations. This should pay specific attention to capturing stakeholders’ narratives and optimizing the child-centred design approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cara Shaw

Cara Shaw is an Inclusive Design practitioner and PhD Researcher with expertise in inclusive paediatric mobility. Cara has developed mobility products for a variety of user groups and contexts; from low-cost evolvable walking aids in Peru, and all-terrain wheelchairs in Kenya, to rehabilitation equipment and paediatric power chairs in the UK.

Farnaz Nickpour

Dr Farnaz Nickpour is a Reader in Inclusive Design and Human Centred Innovation at University of Liverpool. Her work explores critical and contemporary dimensions of design for inclusion across Healthcare and Mobility sectors. Farnaz has over 30 publications and leads The Inclusionaries – Lab for Human Centred Innovation.

References

- Aguirre, M., N. Agudelo, and J. Romm. 2017. “Design Facilitation as Emerging Practice: Analyzing How Designers Support Multi-Stakeholder Co-Creation.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 3 (3): 198–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2017.11.003.

- Ansell, C., and A. Gash. 2007. “Collaborative Governance in Theory.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032.

- Björklund, T., A., T. Keipi, and H. Maula. 2020. “Crafters, Explorers, Innovators, and co-Creators: Narratives in Designers’ Identity Work.” Design Studies 68: 82–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2020.02.003.

- Bobbe, T., J. Krzywinski, and C. Woelfel. 2016. “A Comparison of Design Process Models from Academic Theory and Professional Practice.” International Design Conference.

- Bray, Nathan, Niina Kolehmainen, Jennifer McAnuff, Louise Tanner, Lorna Tuersley, Fiona Beyer, Aimee Grayston, et al. 2020. “Powered Mobility Interventions for Very Young Children with Mobility Limitations to Aid Participation and Positive Development: The EMPoWER Evidence Synthesis.” Health Technology Assessment, 24 (50): 1–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24500.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. 1991. “The Narrative Construction of Reality.” Critical Inquiry 18 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/448619.

- Butler, C. 2009. Effective Mobility for Children with Motor Disabilities, 1–36. Seattle, Washington: GHO Publications.

- Carlgren, L., I. Rauth, and M. Elmquist. 2016. “Framing Design Thinking: The Concept in Idea and Enactment.” Creativity and Innovation Management 25 (1): 38–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12153.

- Casey, J., G. Paleg, and R. Livingstone. 2013. “Facilitating Child Participation through Power Mobility.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 76 (3): 158–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.4276/030802213X13627524435306.

- Clarkson, J., and R. Coleman. 2015. “History of Inclusive Design in the UK.” Applied Ergonomics 46 (B): 235–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.002.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2020. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cross, N. 1982. “Designerly Ways of Knowing.” Design Studies 3 (4): 221–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(82)90040-0.

- Cross, N. 2006. Designerly Ways of Knowing. London: Springer-Verlag.

- Desmet, P., and E. Dijkhuis. 2003. “A Wheelchair Can Be Fun: A Case of Emotion-Driven Design.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces. 2003, 22–27.

- Dillon, J. 1982. “Problem Finding and Solving.” The Journal of Creative Behavior 16 (2): 97–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1982.tb00326.x.

- Everard, L. 1983. “The Wheelchair Toddler”. Contact Magazine (Radar), November 1983. Accessed 01 May 2020. http://www.daneverard.co.uk/mobility/article02.php.

- Feldner, H., S. Logan, and J. Galloway. 2016. “Why the Time is Right for a Radical Paradigm Shift in Early Powered Mobility: The Role of Powered Mobility Technology Devices, Policy and Stakeholders.” Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology 11 (2): 89–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2015.1079651.

- Flodin, E. 2008. “The Desire for Autonomous Upright Mobility: A Longitudinal Case Study.” Technology and Disability 19 (4): 213–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-2007-19407.

- Fritsch, K., A. Hamraie, M. Mills, and D. Serlin. 2019. “Introduction to Special Section.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v5i1.31998.

- Gonçalves, M., C. Cardoso, and P. Badke-Schaub. 2014. “What Inspires Designers? Preferences on Inspirational Approaches during Idea Generation.” Design Studies 35 (1): 29–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2013.09.001.

- Grant, M., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Gray, C., M. 2013. “Factors That Shape Design Thinking.” Design and Technology Education: An International Journal 18 (3): 8–20.

- Grimaldi, S., S. Fokkinga, and I. Ocnarescu. 2013. “Narratives in Design: A Study of the Types, Applications and Functions of Narratives in Design Practice.” In Sixth International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces, 2013, 201–210.

- Grocott, L. 2012. “Designerly Ways of Researching: Design Knowing and the Practice of Researching.” Studies in Material Thinking 6: 1–24.

- Guerette, P., J. Furumasu, and D. Tefft. 2013. “The Positive Effects of Early Powered Mobility on Children's Psychosocial and Play Skills.” Assistive Technology : The Official Journal of RESNA 25 (1): 39–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2012.685824.

- Irwin, T., C. Tonkinwise, and G. Kossoff. 2020. “Transition Design: An Educational Framework for Advancing the Study and Design of Sustainable Transitions.” Notebooks of the Center for Design and Communication Studies 105: 31–65.

- Jakobsone, L. 2017. “Critical Design as Approach to Next Thinking.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S4253–S4262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352923.

- Jasanoff, S., and S. Kim. 2013. “Sociotechnical Imaginaries and National Energy Policies.” Science as Culture 22 (2): 189–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2013.786990.

- Jensenius, A. R. 2012. “Disciplinarities: Intra, Cross, Multi, Inter, Trans”. Accessed 05 May 2020. http://www.arj.no/2012/03/12/disciplinarities-2/

- Johansson-Sköldberg, U., J. Woodilla, and M. Çetinkaya. 2013. “Design Thinking: Past, Present and Possible Futures.” Creativity and Innovation Management 22 (2): 121–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023.

- Joseph, J. 2019. “Designerly Ways of Futuring: Virtual Reality as a Foresight Tool for Long Term Sustainability.” Third International Anticipation Conference.

- Keast, R., K. Brown, and M. Mandell. 2007. “Getting the Right Mix: Unpacking Integration Meanings and Strategies.” International Public Management Journal 10 (1): 9–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490601185716.

- Kersten, W. C., J. C. Diehl, and J. M. L. van Engelen. 2018. “Facing Complexity through Varying the Clarification of the Design Task”. Accessed 05 May 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.2621.

- Konstantoni, K., and A. Emejulu. 2017. “When Intersectionality Met Childhood Studies: The Dilemmas of a Travelling Concept.” Children's Geographies 15 (1): 6–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1249824.

- Laursen, L., and L. Møller Haase. 2019. “The Shortcomings of Design Thinking When Compared to Designerly Thinking.” The Design Journal 22 (6): 813–832. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1652531.

- Leaman, J., and H. M. La. 2017. “A Comprehensive Review of Smart Wheelchairs: Past, Present and Future.” In IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems 47 (4): 486–499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2017.2706727.

- Leeuwen, J., D. Rijken, L. Bloothoofd, and E. Cobussen. 2020. “Finding New Perspectives through Theme Investigation.” The Design Journal 23 (3): 441–461. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2020.1744258.

- Lim, Y., J. Giacomin, and F. Nickpour. 2021. “What is Psychosocially Inclusive Design? A Definition with Constructs.” The Design Journal 24 (1): 5–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2020.1849964.

- Livingstone, R., and G. Paleg. 2014. “Practice Considerations for the Introduction and Use of Power Mobility for Children.” Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 56 (3): 210–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12245.

- Lynch, A., J. Ryu, S. Agrawal, and J., C. Galloway. 2009. “Power Mobility Training for a 7-Month-Old Infant with Spina Bifida.” Pediatric Physical Therapy: The Official Publication of the Section on Pediatrics of the American Physical Therapy Association 21 (4): 362–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181bfae4c.

- Mitchell, S. 1997. Influence and Autonomy in Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge.

- Nessler, D. 2016. “How to Apply a Design Thinking, HCD, UX or Any Creative Process from Scratch”. Accessed 11 May 2020. https://medium.com/digital-experience-design/how-to-apply-a-design-thinking-hcd-ux-or-any-creative-process-from-scratch-b8786efbf812

- Newell, A., and P. Gregor. 1997. “Human Computer Interfaces for People with Disabilities.” In Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, edited by M.G. Helander, T.K. Landauer and P.V. Prabhu, 2nd ed., 813–824. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Nickpour, F., and C. O'Sullivan. 2016. “Designing an Innovative Walking Aid Kit; a Case Study of Design in Inclusive Healthcare Products.” In Designing around People, edited by Langdon P., Lazar J., Heylighen A., and Dong H. Cham: Springer.

- Nilsson, L., M. Eklund, P. Nyberg, and H. Thulesius. 2011. “Driving to Learn in a Powered Wheelchair: The Process of Learning Joystick Use in People with Profound Cognitive Disabilities.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy : Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 65 (6): 652–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.001750.

- Norman, D. 2010. “Why Design Contests Are Bad” Accessed 03 May 2020. https://www.core77.com/posts/17024/Why-Design-Contests-Are-Bad

- O'Sullivan, C., and F. Nickpour. 2020a. “Mapping 50 Years of Design for Childhood Mobility.” Mendeley Data, V1, Accessed 19 May 2020. doi:https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/sfwzw25tjn.1.

- O'Sullivan, C., and F. Nickpour. 2020b. “50 Years of Inclusive Design for Childhood Mobility; Insights from an Illustrative Mapping Review.” In Synergy - DRS International Conference, edited by S. Boess, M. Cheung, and R. Cain, 11-14 August 2020.

- O'Sullivan, C., and F. Nickpour. 2020c. “Drivers for Change: Initial Insights from Mapping Half a Century of Inclusive Paediatric Mobility Design.” In Advances in Usability, User Experience, Wearable and Assistive Technology, edited by T. Ahram, C. Falcão, Vol 1217. Cham: Springer.

- Oxman, R. 1999. “Educating the Designerly Thinker.” Design Studies 20 (2): 105–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-694X(98)00029-5.

- Özkil, A., G. 2017. “Collective Design in 3D Printing: A Large Scale Empirical Study of Designs, Designers and Evolution.” Design Studies 51: 66–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.04.004.

- Pituch, E., P. W. Rushton, M. Ngo, J. Heales, and A. Poulin Arguin. 2019. “Powerful or Powerless? Children's, Parents', and Occupational Therapists' Perceptions of Powered Mobility.” Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics 39 (3): 276–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2018.1496964.

- Schön, D.,A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Self, J., H. Dalke, and M. Evans. 2013. “Designerly Ways of Knowing and Doing: Design Embodiment and Experiential Design Knowledge”. DRS EKSIG 2013: Knowing Inside Out - Experiential Knowledge, Expertise and Connoisseurship.

- Shew, A. 2018. “Different Ways of Moving through the World: How Does Technology Fail Disabled Bodies?” Logic Magazine 5: 207–214.

- Sloan, M., C. 2010. “Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics as the Original Locus for the Septem Circumstantiae.” Classical Philology 105 (3): 236–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/656196.

- Taylor, C. 2003. Modern Social Imaginaries.Durham, USA: Duke University Press.

- Tenenberg, J., D. Socha, and W. Roth. 2014. “Designerly Ways of Being.” DTRS 10: Design Thinking Research Symposium 2014.

- Tonkinwise, C. 2015. “Design for Transitions ‒ from and to What?” Design Philosophy Papers 13 (1): 85–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2015.1085686.

- Venditti, S., F. Piredda, and W. Mattana. 2017. “Micronarratives as the Form of Contemporary Communication.” The Design Journal 20 (sup1): S273–S282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352804.

- Wiart, L., and J. Darrah. 2002. “Changing Philosophical Perspectives on the Management of Children with Physical Disabilities-Their Effect on the Use of Powered Mobility.” Disability and Rehabilitation 24 (9): 492–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280110105240.

- Wobbrock, J., and J. Kientz. 2016. “Research Contribution Types in Human-Computer Interaction.” Interactions 23 (3): 38–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2907069.

- Wong, W., and D. Radcliffe. 2000. “The Tacit Nature of Design Knowledge.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 12 (4): 493–512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713698497.