Abstract

Co-design has been acknowledged as a promising approach to stimulating creativity and promoting local innovation. This paper presents a participatory case study on how co-design stimulates the creativity of the young elderly aged 50–64 in Chinese cities and towns for the first time. The 3-year study analyzes changes in design behavior (making, enacting, telling) of the young elderly in the co-design activity through comparison, and provides insights in the co-design approach, organization structure, and co-design principles. This paper provides experience for co-designing with the young elderly and encourages more stakeholders to engage in co-design for an active aging society.

Introduction

The global aging population is experiencing rapid growth, leading to an increased focus on ‘Active Aging’ among designers. The combination of the elderly and co-design presents a new trend ‘design by everyone’ in design practice. Manzini (Citation2015) contends that co-design plays a crucial role in solving social problems. Additionally, Sanders and Stappers (Citation2008) highlight the popularity of co-design in social innovation.

Cross (Citation1982) introduces the concept of ‘design-style cognition’ and underlines that design knowledge is embedded in design activities and acquired through active participation and reflection (Schön Citation1983). Design achievements generated through the design process can serve as solutions to design problems and sources of design themes (Biggs Citation2002; Mäkelä Citation2007). Therefore, case studies provide valuable empirical knowledge and opportunities for design practices.

The Future Aging, a participatory case study conducted for three years, explores how to co-design with the young elderly aged 50–64 in Chinese cities and towns to stimulate their creativity. The project is a collaborative design project led by Tsinghua University and Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, and jointly initiated by Beijing Science and Technology Association, Beijing Women’s Federation, Qiaoniang Development Association, Qiaoniang Studios, senior citizens, and designers. The study provides insights into the co-design approach, organization structure, and co-design principles.

Literature review

The situation of the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns

China has entered an aging society since 1999. Reports shows the percentage of individuals aged over 60 could surpass 35% within the next 30 years (Han Citation2018). However, the birth population in China continues to decline, as stated by the National Bureau of Statistics. This has created a paradoxical situation characterized by a shortage of labor force alongside an oversupply of retired individuals.

Mui (Citation1996) indicates that in developed countries, 65 years old is commonly regarded as the threshold for entering old age. As of 25 May 2023, Guangming reported on its website that the retirement age in China is 50 for female workers, 55 for female cadres, and 60 for male workers and cadres. Only 26.9% of the aging population aged over 60 report poor health (Lu Citation2015). Notably, the retired population in China is relatively young compared to other countries, highlighting a distinct characteristic of the Chinese context. Consequently, individuals aged 50–64 in China are referred to as the ‘young elderly’. The sixth national census indicates that there are over 100 million retired individuals aged 50–64 in Chinese cities and towns (National Bureau of Statistics of Database Citation2010).

According to activity theory, social activities form the foundation of people’s lives, and finding meaning in social interactions is essential for everyone (Bertelsen and Bødker Citation2003). Social roles and participation in social activities contribute to our sense of identity, and our actions shape the way we live (Moody and Sasser Citation2020). For senior citizens, social activities are also important. When the elderly cannot participate in formal social activities due to retirement, disability, or accidents, they actively seek alternative activities or roles to fill the void (Atchley Citation1985). The elderly need to reduce frustrations stemming from disrupted or changed social roles and enhance social interactions through various social activities. The young elderly in Chinese cities and towns actively participate in a range of social activities. Approximately 30.1% of them use the Internet to access social information, 57.4% express a strong desire to acquire new knowledge and enrich their retirement life, and many are enthusiastic participants in group activities (Lu Citation2015).

The National Population Development Plan (2016–2030) emphasizes the importance of keeping the enthusiasm and initiative of the elderly and tapping into their human resources. With the transformation of the Chinese economic model and the development of the service industry, there is a decrease in labor demand and an increase in needs for creativity. Therefore, it becomes crucial to explore how the co-design approach can empower the young elderly and stimulate their creativity.

Co-design

Co-design is an approach to address social problems (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). The early stage of co-design is often characterized as chaotic and disordered, referred to as the ‘fuzzy’ which involves various activities to inspire exploration of open-ended questions (Herstatt and Verworn Citation2004; Sanders and Stappers Citation2014). Yūsuke (Citation2013), Action (Citation2012), and Brown and Wyatt (Citation2010) emphasize that stakeholders survey problems and needs at the micro level in the early stage of co-design activities. However, the existing research usually overlooks the investigation of social resources from a macro perspective.

To address complex social problems, co-design activities require analyses and discussions from multiple perspectives, as this can promote service exchange and resource integration (Yang and Sung Citation2016). However, co-design often faces challenges of limited participants or resources (Cottam and Leadbeater Citation2004). Therefore, Drew (Citation2019), Yūsuke (Citation2013), Action (Citation2012), Mulgan (Citation2006), and Mulgan et al. (Citation2007) emphasize the importance of recruiting stakeholders and building teams so that provide sufficient resources and manpower for co-design activities. In the activities, the roles and responsibilities of designers change as design objects and activities change. Manzini (Citation2015) highlights that in the era of co-design, anyone can become a designer, and professional designers’ roles shift from experts to facilitators. Experts initiate and support open co-design activities and organize co-design teams. It is an interesting research topic for designers to explore how to organize co-design teams and activities to attract stakeholders to participate in projects.

The key characteristic of co-design is the equality of all stakeholders. Every participant should have an equal opportunity to engage in open co-design activities, in which they can propose new solutions and create new meanings (Manzini Citation2015). However, achieving equal status in co-design activities is not always easy. Pirinen (Citation2016) and Murray, Caulier-Grice, and Mulgan (Citation2010) indicate that differences in power stemming from various professions or educational backgrounds can hinder effective communication. Additionally, other issues exist within co-design projects, such as ambiguity in communication between participants with different backgrounds (Pirinen Citation2016) and excessive reliance on designers by other stakeholders in collaborative development, leading to a lack of autonomy (Huybrechts et al. Citation2018). The absence of education not only diminishes authority but also undermines people’s confidence in their own experiences. In addressing these issues, Huybrechts, Dreessen, and Hagenaars (Citation2018) emphasize designers need to help participants build capacity through visualization, reflection, and action, as well as establish the corresponding relationships among abilities, dialogue, design roles, and infrastructure when participants lack dialogue and participation skills. On the other hand, Drew (Citation2019) and Sanders and Stappers (Citation2014, Citation2008) highlight the importance of establishing design principles or standards in co-design activities. Therefore, it is a growing research trend for designers to consider the key elements of co-design principles to enhance the discourse power and equality of participants.

New challenges for the elderly and co-design

Manzini (Citation2015) proposes it is the era of design by everyone. In other words, the elderly could become a potential creative group. To build an active aging society, the elderly, designers, and non-designers need to take part in co-design activities.

Co-design with the elderly can be categorized into two types. Firstly, designers collaborate in designing artifacts for the elderly. Chavalkul, Saxon, and Jerrard (Citation2011) conduct a study on packaging design to help the elderly understand how to unwrap items. Secondly, designers explore the key factors of co-design with the elderly. Bergvall-Kåreborn and Ståhlbrost (Citation2008) classify the different participatory relationships in the co-design process as design for users, design with users, or design by users. Botero and Hyysalo (Citation2013) focus on co-designing with ordinary old people in the community and propose a series of appropriate design strategies. In line with the concept of ‘design for practice’, design should bring about changes in daily practice, incorporating both internal systems and external design factors (Righi et al. Citation2018). Gonzalez-de-Heredia et al. (Citation2019) survey the elderly and disabled individuals to build a specialized database, providing a quantitative tool for a more inclusive future.

It is a challenge for old people to participate in a co-design activity. Most co-design research for the elderly often restricts dialogues to one or a few stages (Cozza, Tonolli, and D'Andrea Citation2016). Joshi and Bratteteig (Citation2016) discover that older individuals face challenges when distinguishing the final goal of a project. Uzor, Baillie, and Skelton (Citation2012) and Rice and Carmichael (Citation2013) indicate old people may feel uncomfortable when required to paint, provide comments, or solve design problems. To address these issues, researchers have explored tailoring co-design activities and techniques specifically for the elderly (Leong and Robertson Citation2016).

In China, design schools play an important role in initiating co-design projects, with a focus on designing for vulnerable groups. Dong et al. (Citation2020) indicate design is a means to mediate social connections and combat the loneliness experienced by older people. Wang et al. (Citation2021) propose a design strategy for playful products for older adults. However, research on co-design with the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns is limited. Therefore, it is a significant challenge to explore a co-design approach suitable for them, organize design teams to participate in the project, and propose co-design principles that ensure the equality of all participants.

Methodology

China is currently facing the dual challenges of an aging population and declining birth rates. This paper explores how to stimulate the creativity of the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns.

The research adopts a participatory case study approach that has developed for 3 years. Reilly (Citation2010) notes that participatory case studies enable addressing specific problems in a particular context by involving stakeholders, participants, or local groups. This approach allows for the collection of rich contextual data that may not be attainable through other research methods (Evans Citation2010). Cross (Citation2001) indicates that the uniqueness of design knowledge lies in design activities and is acquired through active participation and reflection practice. Hence, a participatory case study can provide valuable contextual data and experiential knowledge to understand the fundamental situation of the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns.

The participant selection criteria among the young elderly in China includes five key aspects (). Firstly, participants are required to fall within the age range of 50 to 64, which reflects the characteristics of the young elderly in China. Secondly, participants need to possess a certain level of knitting experience, which is beneficial to the development and research of co-design activities. Thirdly, participants need to have good physical and mental health, as individuals with severe health issues may struggle to participate in long-term co-design activities. Fourthly, participants should be able to use smartphones, since co-design activities involve both online and offline. Fifthly, participants do not need design experience, since participants with no design experience are more conducive to studying changes in their design behavior during co-design activities.

Table 1. Participant selection criteria.

This study mainly investigates and analyzes the changes in the design behavior of the young elderly – ‘making, enacting, telling’ (Sanders, Brandt, and Binder Citation2010), during co-design activities about handicraft products through comparison ().

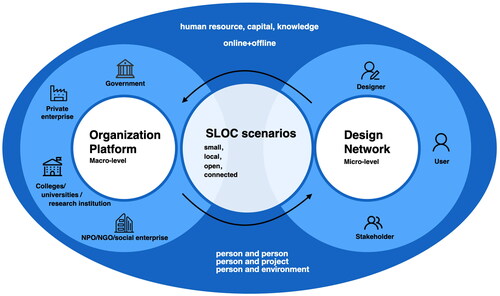

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the adapted co-design process (Drew Citation2019) and data collection process and methods.

The ‘making’ aspect mainly refers to design knowledge and design process applied consciously during the young elderly design a product (Drain and Sanders Citation2019). In this part, questionnaires and semi-structured interviews repeated 4 times are utilized to compare the design knowledge and design processes before and after in a new handicraft product. The ‘enacting’ aspect focuses on how the young elderly demonstrate or perform their designed product. This part mainly compares the presentation tools or methods utilized by the young elderly to show products. The ‘telling’ aspect refers to the communication among team members or individuals involved in the co-design process. This part primarily compares the duration and frequency of each product design cycle.

The data analysis includes project documents (photography, diary writing, sketching, and group discussion), workshops, direct observations, participatory observations, and the content of internal social networks. It is conducted throughout the study period. The summary of the data is refined and confirmed through discussions with participants. Participatory processes need reflection and validation of data and improve the reliability of the findings.

Case study

The Future Aging has been initiated since 2016 by Tsinghua University and the NFO Qiaoniang, which is an organization under the Beijing Women’s Federation. The Qiaoniang provides professional training for retired and unemployed women during their spare time.

The demonstration site is Dongcheng District in Beijing. The study selects eight participants with different backgrounds, who has learned handicrafts for a period from a few months to years. It is the first time for all participants to take part in the co-design. The project explores a co-design approach to stimulate their creativity through the design practice of modern handicraft products.

Exploration and focus stage

The paper utilizes a co-design approach to empower the young elderly in China. The approach consists of several stages: the exploration and focus stage, the team-building stage, the co-development stage, and the communication and promotion stage. provides an overview of the co-design and research activities.

Resource and problem exploration

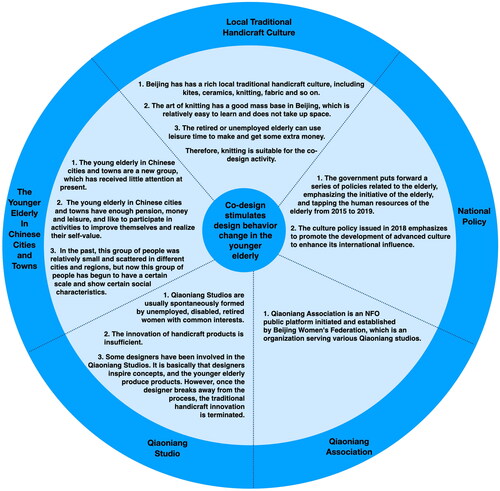

The study explores available resources, which include government policies, local cultural resources, available organization resources, and an understanding of the general situation of the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns ().

The government has frequently issued some national policies including four aspects - keeping the enthusiasm of the elderly, developing the human resources of the elderly to protect the basic rights and welfare of the young elderly, guaranteeing a high-quality labor force, promoting the development of the country and society ().

Table 2. List of national policies related to the elderly.

Beijing has a rich traditional handicraft culture, including kites, ceramics, knitting, and fabric (). The art of knitting has a good base in Beijing due to its ease of learning and minimal space requirements. Retired or unemployed individuals can use leisure time to make and get some extra money. Therefore, knitting is suitable for the co-design activity.

Figure 3. The Future Aging: (a) Traditional handicraft cultural resources in Beijing, (b) Survey on local organization resources: Qiaoniang Association, Qiaoniang Studios, (c) Survey on the manager of the Qiaoniang Association, the Qiaoniang Studio, and the young elderly, (d) The co-design team, (e) Sharing knowledge in the co-design workshop, (f) The goals’ discussion and tasks in the workshop, (g) survey on a factory, (h) acrylic lamp, (i) Recording opinions, (j) Sharing the Future Aging Project, (k) The final fabrics are designed by the young elderly.

Qiaoniang Studios are usually spontaneously formed by unemployed, disabled, retired women with common interests, which have driven nearly 300,000 old people to work at home flexibly. However, there is a lack of innovation in handicraft products within these studios. Although, some designers have been involved in the Qiaoniang Studios, senior citizens are not really involved in design activities. In these activities, it is basically that designers inspire concepts, and the young elderly produce products (Fang Citation2012; Yang Citation2014). Once the designer goes away from the process, the traditional handicraft innovation is terminated (Fang Citation2012).

Qiaoniang Association is an NFO public platform initiated by the Beijing Women’s Federation for serving various Qiaoniang studios.

The study surveys the young elderly, managers, and other stakeholders from a micro perspective (). The young elderly in Chinese cities and towns are a new group. They have enough pension, leisure time, and like to participate in activities to improve themselves and realize their self-value. In the past, this group was relatively small and scattered in different cities and regions, but now they have begun to have a certain scale and show certain social characteristics.

Problem definition

The co-design team discusses the final design direction () and prefers to tap into the creativity of the young elderly in Beijing by designing traditional handicraft products. The young elderly have free time, and easily find crafts materials and factories. Furthermore, universities, governments, and NFOs/NGOs in Beijing can provide human resources, policy resources, and funds.

Team-building stage

The early stage of co-design generally is chaotic, such as unclear participation organization, and poor communication in a team (Sanders and Stappers Citation2014). Therefore, designers focus on the organization structure to ensure co-design effectively and efficiently.

Stakeholder recruitment

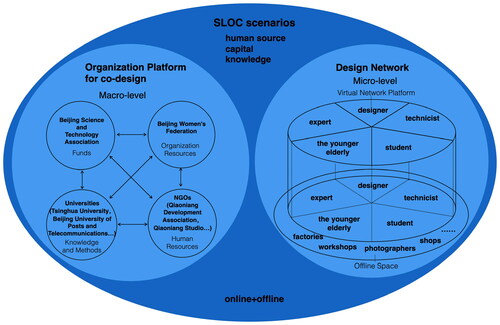

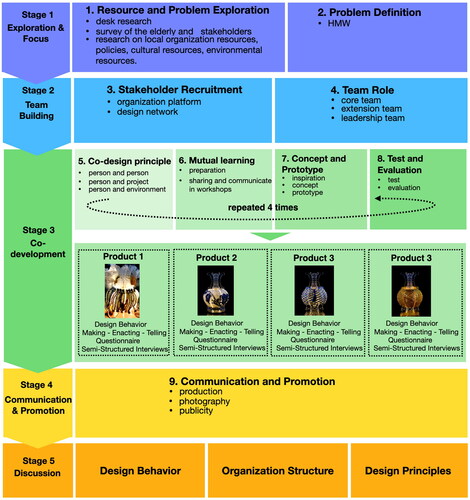

Manzini (Citation2011) proposes the SLOC (small, local, open, and connected) scenario, which could be applied to establish a small, local, open, and connected organization. Two core organization systems are established: the macro-level organization platform and the micro-level design network ().

At the macro level, the project integrates various social resources to provide human, capital, and knowledge for the co-design organization platform (). The platform is jointly constructed by Tsinghua University, Beijing Association for Science and Technology, Beijing Women’s Federation, Qiaoniang Association, Qiaoniang Association in Dongcheng District, and Qiaoniang Studios. Beijing Association for Science and Technology provides funds, Beijing Women’s Federation recommends suitable NGOs/NFOs, and Qiaoniang Studios provides the young elderly.

At the micro level, the design network is formed among designers, experts, students, the young elderly, and technicists (). The project is implemented both online and offline. Each stakeholder has a unique role. Designers organize stakeholder’ participation; experts provide professional feedback during important co-design stages; the young elderly form small teams or independently to design; students design lamp styles, assemble lamps, and provide help for old people; technicists offer technical support including welding, installation, and wiring.

Team role

To better co-design with stakeholders, the study divides team members into three types: core team, extension team, and leadership team (Nesta and IDEO Citation2017). The core team is composed of experts, students, the young elderly, and designers, who communicate frequently and input/output in the whole process of the co-design activity. The expansion team is composed of all kinds of factories, workshops, photographers, and shops, which are involved in the phased co-design activity. The leadership team is composed of universities, governments, and NGOs/NPOs, which is the management organization and needs to inform the progress and problems regularly.

Co-development stage

Sanders and Stappers (Citation2008) and Drew (Citation2019) indicate the importance of establishing design standards or principles before co-designing to manage stakeholders, improve communication efficiency, keep the same goal, and avoid unnecessary conflicts. Therefore, the study proposes co-design principles for the young elderly to complete the project.

Co-design principle

The first principle is about interpersonal relationships. The young elderly participate in the co-design activity for the first time, and it is difficult to quickly build group trust. Karlsen, Græe, and Massaoud (Citation2008) indicate that building group trust relies heavily on sincerity. Preston and De Waal (Citation2002) point out empathy is related to altruism, while Wang, Bryan-Kinns, and Ji (Citation2016) and Wang et al. (Citation2022) emphasize that empathy and inclusion is an effective means of connecting with vulnerable groups and tapping into their indigenous wisdom. Additionally, Fuchs (Citation2008), Luck (Citation2018), and Veselova and Gaziulusoy (Citation2019) mention the importance of equality and peering in fostering collective intelligence. Furthermore, Drew (Citation2019) notes visual communication is important in design for social innovation. A person is the smallest unit in a team, so team members need sincerity, empathy, equality, and intuition.

The second principle is goal orientation, as a common goal can drive people to co-design. Joshi and Bratteteig (Citation2016) say it is hard for old people to distinguish project goals. Goal orientation is recognized as a significant factor for learners to engage in various learning activities (Setiawan, Dunn, and Cruickshank Citation2019; Song and Grabowski Citation2006).

The third principle is about the relationship between individuals and the environment. Some studies indicate that a positive atmosphere can motivate team members to create (McCoy and Evans Citation2002; Schepers and Van Den Berg Citation2007). Therefore, the team should provide a friendly atmosphere to encourage multi-discipline cooperation and mutual assistance.

Mutual learning

To turn a design network into a design alliance, researchers should establish workshops where participants share professional knowledge, tools, and experience to achieve a common design goal and language environment (Manzini Citation2015). However, the elderly may not be good at imagining design effects (Zitkus and Libanio Citation2019). Asheim, Coenen, and Vang (Citation2007) suggest that face-to-face communication is the most effective way to acquire invisible knowledge as it provokes in-depth dialogues. Therefore, stakeholders in the workshop are encouraged to communicate the background, meaning, goals, tasks, principles, process, experience of the project, and expertise to facilitate understanding through visualization.

Szabó and Négyesi (Citation2005) highlight that empirical knowledge acquired through collaboration is an important factor. The co-design team shares knowledge and expertise in workshops to guide participants to engage in the project. Designers and experts share cultural knowledge and design strategies through design cases and theories, while the young elderly introduce handicraft techniques ().

The elderly may have limited understanding abilities (Zitkus and Libanio Citation2019), slower new knowledge absorption rates (Rice and Carmichael Citation2013), and memory difficulties (Zitkus and Libanio Citation2019). Repeated sharing and communication are necessary to ensure that the young elderly become increasingly integrated into the co-design activity and that relationships among participants strengthen. Before the workshops, the study should prepare a virtual co-design platform, websites, physical spaces, physical models, tools, and materials ().

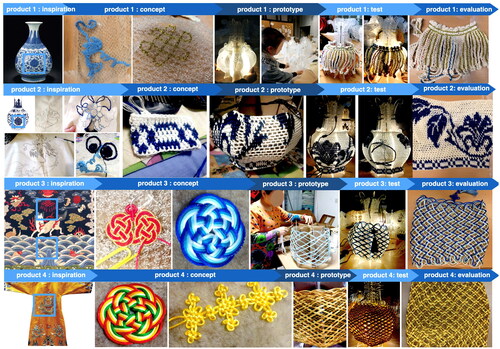

Concept and prototype

The young elderly have started to focus on various aspects, such as CMF (color, material, finish), culture, technologies, design strategies, and users. They consciously select interesting materials, classical Chinese traditional colors and patterns to express ideas by rapidly prototyping or sketching. Some of them choose to knit a production inspired by blue and white porcelain (), while others opt for elastic materials for easy installation. And they begin to pay attention to the design process.

Test and evaluation

The young elderly use their leisure time to design twenty-seven novel fabrics based on Chinese traditional culture through fifteen workshops, and test the fabrics on acrylic lamps (). They acquire design knowledge and master procedure to improve creativity and realize self-worth. Some participants continue discussing design knowledge and design procedure beyond the project duration.

Communication and promotion stage

Stakeholders select specific fabrics and acrylic lamps for mass production, and systematically summarize the key highlights of the Future Aging, including the co-design approach, organization structure, and co-design principles. Various communication channels are utilized to promote the co-design project internally and externally (). The project is recognized as an excellent example about design for social innovation. Beijing Women’s Federation and Qiaoniang Association invite other colleagues to visit and learn. shows the final fabrics designed by the young elderly in Beijing.

Discussion and conclusion

The first application of the co-design approach to stimulating the creativity of the young elderly in Chinese cities and towns

The young elderly in Chinese cities and towns are a new group. This paper is the first time to use co-design to stimulate the creativity of the young elderly in Beijing and analyzes changes in their design behavior in the whole co-design process through comparison.

Although this paper has gained inspiration from the classical co-design approach (Brown and Wyatt Citation2010; Drew Citation2019; Sanders and Stappers Citation2014), it brings several modifications tailored to the research subject. These adaptations are highlighted in four key aspects ():

During the early stage of co-design, the paper emphasizes the importance of exploring local resources, such as national and local government policies, local culture resources, civil organization resources, and environmental resources, which can provide a realization foundation and diverse perspectives.

During the team building stage, the paper emphasizes the importance of two core organization systems which are from the three aspects of people, capital, and knowledge within the SLOC scenarios- a macro-level organization platform and a micro-level design network.

During the co-development stage, the paper proposes co-design principles: ‘the relationship between person and person’, ‘the relationship between person and project’, and ‘the relationship between person and environment’, which play an important role in co-design activities.

During the communication and promotion stage, it is important to encourage each participant to publicize the co-design activities, processes, ideas, products, and systems both internally and externally. This contributes to scaling effects in different regions and organizations.

This study analyzes changes in the design behavior (making, enacting, telling)of the young elderly when they design handicraft products in the co-design activity through comparison.

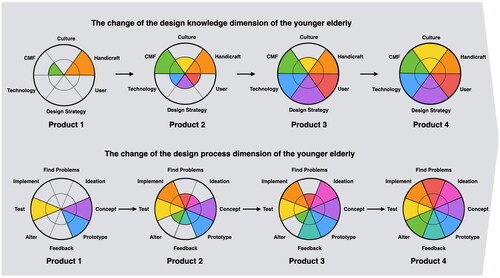

Regarding the changes in making behavior, the study compares the changes in design knowledge and design process when the young elderly are creating products. With the increasing number of co-design activities, their design knowledge and design process become more diversified and enriched ().

Figure 6. The changes in making behavior (the dimensions of design knowledge and design process) of the young elderly.

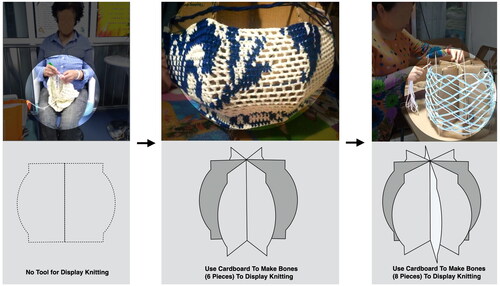

Concerning the changes in enacting behavior, the study focuses on the presentation tools made by the young elderly to showcase their products (). Initially, they rarely create specific tools for displaying their knitting products. However, as their involvement in co-design activities increases, they begin to develop their tools to present their knitting products more effectively. For example, the skeleton is made of six cardboard pieces for display, but the size of the knitting fabric is too small to fit on the lamps. To achieve a more suitable and realistic effect, they subsequently create eight cardboard pieces to display again.

Regarding the changes in telling behavior, the study mainly examines the duration and frequency of product design cycles among the young elderly in the co-design activity. As the elderly do more and more skilled, the duration of each product design cycle decreased, and the frequency of communication sessions also gradually reduced. The first product design needs four months and six communications sessions. The second product design takes three months and four communication sessions. The third product design lasts two months with three communication sessions. The fourth product design needs 1.5 months and two communications sessions.

Through a participatory case study, the paper presents a shift from unself-conscious design to self-conscious design among the young elderly, which is quite crucial. The transformation from ‘design with the elderly’ to ‘design by the elderly’ may come true.

The organization structure of the Co-Design activity

As initiators of co-design activities, designers not only focus on design development but also consider the organization structure and teams involved. To recruit multi-stakeholders, the study proposes the two core organization groups within the SLOC scenarios - a macro-level organization platform and a micro-level design network ().

The organization platform of the co-design activity integrates various resources, including human resources, capital, and knowledge. It combines the resources of governments, social enterprises, research institutions, and private enterprises to provide a solid foundation for co-design activities. The Chinese government provides funding, policies, and social resources. Research institutions have excellent talents, cutting-edge theoretical knowledge, and practice methods. Social enterprises provide suitable human resources and new perspectives, while private enterprises offer skilled technicians, products, and materials.

The design network of the co-design activity establishes an online and offline co-design alliance, bringing together designers, users, researchers, technicians, and other stakeholders. The online alliance provides a platform for stakeholders to exchange information, knowledge, and address issues anywhere and anytime. The offline alliance involves a physical space for face-to-face communication and design practice.

The organization platform and design network complement and reinforce each other. The organization platform provides people, knowledge, and funds for the design networks, while the design network empowers individuals and organizations. A good organization platform can attract more social sources, and a good design network also can attract more organizations and citizens to practice. The organization structure can develop into a spiral structure of the organization model.

The proposed co-design principles from three perspectives: ‘Person-Project-Environment’

It is necessary to propose co-design principles to solve these problems. First, since all participants in a co-design activity cooperate for the first time, building trust and understanding can be challenging initially, leading to project development difficulties. Second, stakeholders from diverse backgrounds and social statuses may have unequal discourse power (Huybrechts et al. Citation2018). Third, participants with varying experiences and backgrounds may also hold different work standards.

To advance co-design with stakeholders, the paper proposes co-design principles from three perspectives: ‘the relationship between person and person’, ‘the relationship between person and project’, and ‘the relationship between person and environment’, which play an important role in team building and project development.

Firstly, the relationship between person and person should be sincere, empathetic, equal, and intuitive, as a person is the smallest unit in a team. Sincere communication among all participants helps establish quick trust. Empathy and understanding are important to avoid conflicts. Equal and diverse dialogues with stakeholders foster trust within the group and ensure equal discourse power. Visual communication improves participants’ intuition, and the improvement of intuition can promote the efficiency of communication.

Secondly, participants may have different perspectives about the relationship between individuals and the project, such as ‘project-oriented’, ‘relationship-oriented’, ‘person-oriented’, which can cause issues and conflicts. So to avoid confusion, the paper emphasizes the importance of the ‘goal-driven’ principle in co-design activities.

Thirdly, a positive organizational environment stimulates team members’ enthusiasm and creativity (De Alencar and De Bruno‐Faria 1997). Therefore, the co-design team needs to create a friendly atmosphere to encourage positive communication and creativity.

The 3-year participatory case study aims to explore how co-design stimulates the creativity of the young elderly (aged 50–64) in Chinese cities and towns. The paper analyzes changes in the design behavior among the young elderly through comparison, while also exploring the co-design approach, organization structure, and co-design principles. The findings of this case study are expected to contribute to design research on co-design with the elderly, while also attracting more stakeholders in co-design efforts for an active aging society.

Note

The Qiaoniang Development Association in Beijing: http://www.bjwomen.gov.cn/fnw_2nd_web/static/catalogs/00000000644466db0164455f1d0a00cb/index.html

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all participants in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jiapei Zou

Jiapei Zou is an Assistant Professor at the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications. Her research interests include co-design for or with the elderly, and social design.

Zhensheng Liu

Zhensheng Liu is an Associate Professor at the Tsinghua University. He researches social design, design for old people, and initiates the project with the government, NGOs/NFOs, citizens, and private companies.

Chao Zhao

Chao Zhao is Professor at the Tsinghua University. His research interests include design for the elderly, social design, and service design.

References

- Action 2012. "5% Design Action - The Four Stages of the Social Design Process [5% Design Action-社会设计四大步骤执行流程]." 5% Design Action Social Design Platform. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://5percent-design-action.com/about.php

- Asheim, B., L. Coenen, and J. Vang. 2007. “Face-to-Face, Buzz, and Knowledge Bases: Sociospatial Implications for Learning.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25 (5): 655–670. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0648

- Atchley, R. C. 1985. Social Forces and Aging. California, USA: Wadsworth Pub. Co.

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., and A. Ståhlbrost. 2008. “Participatory Design: One Step Back or Two Steps Forward?.” In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design, 102–111. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. https://doi.org/10.1145/179523

- Bertelsen, O. W., and S. Bødker. 2003. “Activity Theory.” In HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks: Toward a Multidisciplinary Science, edited by John M. Carroll, 291–324. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Biggs, M. 2002. “The Role of the Artefact in Art and Design Research.” International Journal of Design Sciences and Technology 10 (2): 19–24.

- Botero, A., and S. Hyysalo. 2013. “Ageing Together: Steps towards Evolutionary Co-Design in Everyday Practices.” CoDesign 9 (1): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.760608

- Brown, T., and J. Wyatt. 2010. “Design Thinking for Social Innovation.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 8: 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1596/1020-797X_12_1_29

- Chavalkul, Y., A. Saxon, and R. N. Jerrard. 2011. “Combining 2D and 3D Design for Novel Packaging for Older People.” International Journal of Design 5: 43–58.

- Cottam, H., and C. Leadbeater. 2004. RED Paper 01: Health: Co-Creating Services. London: Design Council.

- Cozza, M., L. Tonolli, and V. D'Andrea. 2016. “Subversive Participatory Design: Reflections on a Case Study.” In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Interactive Exhibitions, Workshops-Volume 2, 53–56. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2948076.2948085

- Cross, N. 1982. “Designerly Ways of Knowing.” Design Studies 3 (4): 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(82)90040-0

- Cross, N. 2001. “Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science.” Design Issues 17 (3): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/074793601750357196

- De Alencar, E. M. L. S., and M. F. De Bruno-Faria. 1997. “Characteristics of on Organizational Environment Which Stimulate and Inhibit Creativity.” The Journal of Creative Behavior 31 (4): 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1997.tb00799.x

- Dong, Y., H. Weng, H. Dong, and L. Liu. 2020. “Design as Mediation for Social Connection against Loneliness of Older People.” In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 41–52. Cham: Springer.

- Drain, A., and E. B. N. Sanders. 2019. “A Collaboration System Model for Planning and Evaluating Participatory Design Projects.” International Journal of Design 13 (3): 39–52.

- Drew, C. 2019. "The Double Diamond: 15 Years on." Design Council. Accessed September 3 2022. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/newsopinion/doublediam-ond-15-years.

- Evans, M. 2010. “Researcher Practice: Embedding Creative Practice within Doctoral Research in Industrial Design.” Journal of Research Practice 6 (2): M16.

- Fang, D. 2012. “Research on the Innovative Design of Handicrafts in Qiaoniang Studio [巧娘工作室背景下的手工艺品创新设计研究.”., ]M.A. thesis., Tsinghua University.

- Fuchs, C. 2008. “Don Tapscott & Anthony D. Williams: Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything.” International Journal of Communication 2: 11.

- Gonzalez-de-Heredia, A., D. Justel, I. Iriarte, A. Beitia, and J. Hernandez-Galan. 2019. “Analysis of the Pilot Survey INKLUGI about Aging and Disabilities to Promote Inclusive Design in Industry.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595429

- Han, Z. 2018. “Research on Aging Issues [老龄化问题应对研究].”.,." PhD diss., Central Party School of the Communist Party of China[中共中央党校].

- Herstatt, C., and B. Verworn. 2004. The ‘Fuzzy Front End’of Innovation. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Huybrechts, L., K. Dreessen, and B. Hagenaars. 2018. “Building Capabilities through Democratic Dialogues.” Design Issues 34 (4): 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00513

- Huybrechts, L., N. Hendriks, S. L. Yndigegn, and L. Malmborg. 2018. “Scripting: An Exploration of Designing for Participation over Time with Communities.” CoDesign 14 (1): 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1424205

- Joshi, S. G., and T. Bratteteig. 2016. “Designing for Prolonged Mastery. On Involving Old People in Participatory Design.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 28 (1): 1.

- Karlsen, J. T., K. Græe, and M. J. Massaoud. 2008. “Building Trust in Project‐Stakeholder Relationships.” Baltic Journal of Management 3 (1): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465260810844239

- Leong, T. W., and T. Robertson. 2016. “Voicing Values: Laying Foundations for Ageing People to Participate in Design.” In Proceedings of the 14th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers-Volume 1, 31–40. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2940299.2940301

- Lu, J. 2015. “The ‘Rise’ of ‘Chinese Aunts’: An Inevitable Historical Phenomenon——Based on the Data Analysis of the Three Surveys of Women’s Social Status in Shanghai [“中国大妈”的“崛起”:一个必然的历史现象——基于三期上海妇女社会地位调查的数据分析].” New Normal and Grand Strategy——Collected Papers of the 13th Annual Academic Conference of Shanghai Social Sciences 2015: 16.

- Luck, R. 2018. “What is It That Makes Participation in Design Participatory Design?” Design Studies 59: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2018.10.002

- Mäkelä, M. 2007. “Knowing through Making: The Role of the Artefact in Practice-Led Research.” Knowledge, Technology & Policy 20 (3): 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12130-007-9028-2

- Manzini, E. 2011. “The New Way of the Future: Small, Local, Open and Connected.” Social Space, 100–105.

- Manzini, E. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs. Cambridge, USA: MIT press.

- McCoy, J. M., and G. W. Evans. 2002. “The Potential Role of the Physical Environment in Fostering Creativity.” Creativity Research Journal 14 (3-4): 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1434_11

- Moody, H. R., and J. R. Sasser. 2020. Aging: Concepts and Controversies. California, USA: Sage Publications.

- Mui, A. C. 1996. “Depression among Elderly Chinese Immigrants: An Exploratory Study.” Social Work 41 (6): 633–645.

- Mulgan, G. 2006. “The Process of Social Innovation.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 1 (2): 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1162/itgg.2006.1.2.145

- Mulgan, G., S. Tucker, R. Ali, and B. Sanders. 2007. Social Innovation: What it is, Why it Matters and How it can be Accelerated.

- Murray, R., J. Caulier-Grice, and G. Mulgan. 2010. The Open Book of Social Innovation. Vol. 24. London: Nesta.

- National Bureau of Statistics of Database 2010. Summary Data of the Sixth National Census. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm

- Nesta and IDEO. 2017. “Designing for Public Services: A Practical Guide.” Design for Europe. Accessed 18: 2019. http://designforeurop-e.eu/newsopinion/designing-public-services-practical-guide-nesta-ideo

- Pirinen, A. 2016. “The Barriers and Enablers of Co-Design for Services.” International Journal of Design 10 (3): 27–42.

- Preston, S. D., and F. B. De Waal. 2002. “Empathy: Its Ultimate and Proximate Bases.” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 25 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x02000018

- Reilly 2010. Participatory Case Study.

- Rice, M., and A. Carmichael. 2013. “Factors Facilitating or Impeding Older Adults’ Creative Contributions in the Collaborative Design of a Novel DTV-Based Application.” Universal Access in the Information Society 12 (1): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-011-0262-8

- Righi, V., S. Sayago, A. Rosales, S. M. Ferreira, and J. Blat. 2018. “Co-Designing with a Community of Older Learners for over 10 Years by Moving User-Driven Participation from the Margin to the Centre.” CoDesign 14 (1): 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2018.1424206

- Sanders, E. B. N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

- Sanders, E. B. N., and P. J. Stappers. 2014. “Probes, Toolkits and Prototypes: Three Approaches to Making in Codesigning.” CoDesign 10 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.888183

- Sanders, E. B. N., E. Brandt, and T. Binder. 2010. “A Framework for Organizing the Tools and Techniques of Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference: 195–198. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900476

- Schepers, P., and P. T. Van Den Berg. 2007. “Social Factors of Work-Environment Creativity.” Journal of Business and Psychology 21 (3): 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-006-9035-4

- Schön 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London, UK: Routledge.

- Setiawan, A., N. Dunn, and L. Cruickshank. 2019. “Geographical Context Influence on Co-Design Practice between Indonesia and the UK Context.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595398

- Song, H. D., and B. L. Grabowski. 2006. “Stimulating Intrinsic Motivation for Problem Solving Using Goal-Oriented Contexts and Peer Group Composition.” Educational Technology Research and Development 54 (5): 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-006-0128-6

- Szabó, K., and Á. Négyesi. 2005. “The Spread of Contingent Work in the Knowledge-Based Economy.” Human Resource Development Review 4 (1): 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304274073

- Uzor, S., L. Baillie, and D. Skelton. 2012. “Senior Designers: Empowering Seniors to Design Enjoyable Falls Rehabilitation Tools.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1179–88. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208568

- Veselova, E., and А. İ. Gaziulusoy. 2019. “Implications of the Bioinclusive Ethic on Collaborative and Participatory Design.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 1571–1586. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1594992

- Wang, D., H. Wei-An, C. Shu-Yi, and H. H. Tang. 2022. “The Complexities of Transport Service Design for Visually Impaired People: Lessons from a Bus Commuting Service.” International Journal of Design 16 (1): 55.

- Wang, T., D. Xiao, Y. Dong, and R. H. Goossens. 2021. “Development of a Design Strategy for Playful Products of Older Adults.” The Design Journal 24 (4): 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2021.1912903

- Wang, W., N. Bryan-Kinns, and T. Ji. 2016. “Using Community Engagement to Drive Co-Creation in Rural China.” International Journal of Design 10: 37–52.

- Yang, C. F., and T. J. Sung. 2016. “Service Design for Social Innovation through Participatory Action Research.” International Journal of Design 10 (1): 21–36.

- Yang, X. 2014. “Innovative Application of Handicraft Art of Rural Qiaoniang Studios in Furniture Industry [农村巧娘工作室手编工艺在家具产业中的创新应用].” M.A. thesis., Tsinghua University.

- Yūsuke, K. 2013. The Essence of Social Design. Tokyo, Japan: Eiji Press.

- Zitkus, E., and C. Libanio. 2019. “User Experience of Brazilian Public Healthcare System. A Case Study on the Accessibility of the Information Provided.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595449