ABSTRACT

As in many other countries, Finnish primary school teacher education has reduced substantially the amount of music studies during recent decades. From the perspective of the National Core Curriculum, there is a reason to reflect on teacher education and primary school student teachers’ skills to teach music. The present study investigates 392 student teachers’ musical skills in five different teacher training programmes in Finland. The data, mainly based on students’ self-assessment, was collected through a quantitative questionnaire. The results reveal significant shortcomings of music education in teacher training. For example, many key content areas such as singing or composing, are addressed extraordinarily little. Only 4% of the students fully agreed with the statement that primary school teacher education has given them good musical skills to teach music. It seems obvious that some skills have already been acquired from students’ previous musical activities. The results of the study show that primary school teacher education may be graduating teachers who are at risk of not meeting the National Core Curriculum goals in music.

Introduction

In many western countries, generalist primary school teachers are expected to teach arts, including music (Lummis, Morris, and Paolino Citation2014; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015). In recent decades, music as well as other arts, have been given extremely limited attention in primary school teacher education (Burak Citation2019; Hennessy Citation2017). This is mainly a political question, as many governments are reluctant to fund arts education because it is considered non-productive in economic terms (Hennessy Citation2017; Juntunen Citation2017; Lummis, Morris, and Paolino Citation2014; Russell-Bowie Citation2009). Consequently, the expertise in music teaching depends on individual teachers’ personal interest and activities in music (Holden and Button Citation2006; Rosa-Napal et al. Citation2021; Saetre Citation2018). The issue of primary school teachers’ lack of musical skills has been a concern for teacher educators internationally, such as in Australia (Russell-Bowie Citation2009; Vries Citation2013), England (Atkinson Citation2018; Henley Citation2017), Ireland (Kenny Citation2017; Moore Citation2019), the Nordic Countries (Juntunen Citation2017; Saetre Citation2018) and Turkey (Burak Citation2019).

The musical experiences children have at the primary level, are largely dependent on the teachers they encounter (Moore Citation2019; Saetre Citation2018). Because music education is often the responsibility of general primary school teachers, pupils are in an unequal position when there is no guarantee they will have a competent and enthusiastic teacher in music (Burak Citation2019; Henley Citation2017). Furthermore, the low level of musical self-efficacy of primary school teachers often leads them to lack confidence about music teaching and deem teaching music as an exceedingly difficult and complicated task (Burak Citation2019; Lummis, Morris, and Paolino Citation2014; Vries Citation2013).

One of the reasons for this teaching insecurity that is often not articulated in previous studies is the music curriculum itself (Hennessy Citation2017). The National Curriculum represents the official curriculum, the aims and content of which are set out in some detail (Ornstein and Hunkins Citation2018). In Finland, the national music curriculum was written by a group of music teachers and teacher educators, and the group was nominated by the National Board of Education.

Primary school teachers are charged with delivering a broad music curriculum; thus, they must meet many curricular requirements such as singing, playing one or two instruments, knowing music theory and listening to a repertoire of musical genres and history (Hennessy Citation2017; Moore Citation2019; Rosa-Napal et al. Citation2021). Perhaps the most difficult requirement is to teach the pupils to create their own music, for example, simple childrens’ songs (Saarelainen and Juvonen Citation2017). The high standard required by the National Curriculum is a major challenge to primary teacher education both internationally (Henley Citation2017; Holden and Button Citation2006; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015), and in Finland (Juntunen Citation2017; Mäkinen and Juvonen Citation2017).

The study of learning outcomes of arts conducted by the Finnish National Board of Education revealed that pupils (n = 4792) leave basic education with a rather varied knowledge and skill level in music (Juntunen Citation2017). Juntunen refers to Finnish primary teacher education as one of the key reasons for the results. The situation is further complicated by the fact that since 1990s, the entrance exams for the teacher education programme do not assess the students’ musical abilities or prior activities (Hietanen, Koiranen, and Ruismäki Citation2017; Juntunen Citation2017). The present study complements Juntunen’s (Citation2017) research by focusing on primary teacher education, and student teachers’ musical skills from the perspective of the National Core Curriculum implementation in music.

Music education in Finland – determined by the National Core Curriculum

In Finland, primary school teachers have the formal qualifications to teach all subjects in grades 1–6 according to the National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Government Decree Citation2018). The National Curriculum aims to unify education and make it comprehensive in every school (Salminen and Annevirta Citation2014; Thomson and Lehtinen-Schnabel Citation2019). There is a strong confidence in Finnish society that primary school teachers are significant experts in this task (Sahlberg Citation2011; Salminen and Annevirta Citation2014). However, general primary school teachers have a high degree of autonomy and pedagogical freedom to implement the music curriculum, make decisions on the content and choose teaching methods (Vitikka, Salminen, and Uusivirta Citation2012).

In basic education, music is taught 1–2 h a week, depending on the local policy makers’ decisions (Government Decree Citation2018). The task of the subject of music is to ‘create opportunities for versatile music activities’ by music making which includes singing, playing, moving, composing and listening (FNBE Citation2014, 348). In the National Core Curriculum, the goals and contents of music are presented separately for grades 1–2, and 3–6. This study focuses mainly on music making in grades 3–6.

Objectives of instruction in music in grades 3–6 (FNBE Citation2014, 350):

O1 (singing) to guide the pupil in the use of natural voice and singing,

O2 (playing instruments) to develop the pupil’s skills in using body percussion and rhythm, melody, and chord instruments as a member of a group,

O3 (moving) to encourage the pupil to express music and emotions through movement,

O4 (composing) to encourage the pupil to improvise as well as to plan and implement small-scale compositions and

O5 (listening) to guide the pupil to explore his or her musical experiences and the aesthetic, cultural, and historical diversity of music.

To be able to implement a music curriculum, a primary school teacher needs diverse musical skills. For example, directing a pupil to the correct use of natural voice requires familiarity with singing techniques, and voice control (Lamont, Daubney, and Spruce Citation2012; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015). Improvising and composing refer to the conception and production of compositions as well as music technology (Kenny Citation2017; Saetre Citation2018). In terms of listening to music, the teacher should master a relatively wide repertoire, such as music from diverse cultures and genres (Anttila Citation2010; Saarelainen and Juvonen Citation2017).

The National Core Curriculum also defines the goals and contents of primary teacher education, the purpose of which is to provide all student teachers with the requisite qualifications to teach music, as well as other subjects (Government Decree Citation2018). The primary school teacher education programme takes five years, and the students receive a master’s degree in Education (300 ECTS). During the first two years, the students complete their subject studies, such as mathematics, mother tongue language, history, music, art, and science (60 ECTS). Currently, students must acquire five credits (5 ECTS) in music studies on average (Juntunen Citation2017), of which a considerable part consists of the students’ independent work (Mäkinen and Juvonen Citation2017).

Although teacher education departments have a common goal, they make extensive use of their autonomy in developing their own curricula (Niemi Citation2011). The latest study (Suomi and Ruismäki Citation2021) revealed that 86% of music lecturers (n = 27/29) in Finnish teacher training almost or completely disagreed that music education (only 5–6 ECTS) would be able to provide all students with sufficient skills to teach music in grades 1–6. Most of the teacher training units focus on playing school or band instruments, resulting in significantly less content related to singing and listening to music (Suomi and Ruismäki Citation2021).

Generally, music studies are built on two or three courses consisting of music pedagogy, different music making contents and piano accompaniment (Mäkinen and Juvonen Citation2017; Suomi and Ruismäki Citation2021). In Finland, it is expected that a generalist primary school teacher has an ability to accompany at least easy school songs (Anttila Citation2010; Ketovuori Citation2015; Sepp, Ruokonen, and Ruismäki Citation2015). Many primary school teachers also perceive piano playing as an essential skill in music teaching, along with singing skills (Mäkinen and Juvonen Citation2017; Vesioja Citation2006).

In Finnish universities, student feedback is routinely collected after courses and this feedback is used when developing courses further. Additionally, there are some investigations carried out in primary school teacher education music courses. Sepp et al. (Citation2018) studied students’ expectations and reflections about piano courses in Finnish primary school teacher education. Most of the students described themselves as beginners, which may cause some challenges with their motivation and goal setting in music studies.

Because education in arts is crucial to children’s development (Tervaniemi, Tao, and Huotilainen Citation2018), it is vital that general primary school teachers are equipped with the skills and knowledge necessary to provide meaningful arts experiences (Henley Citation2017; Jorgensen Citation2008; Lummis, Morris, and Paolino Citation2014). Teacher’s prior musical activities, experiences and values regarding music have a significant impact on how music is taught in schools (Kenny Citation2017; Georgii-Hemming Citation2013). As an implementer of the curriculum, the teacher plays an incredibly significant role (Moore Citation2019; Saetre Citation2018). The question, therefore, arises as to whether the skills of student teachers are sufficient for the requirements of the music curriculum.

Method

The present quantitative study examines the equivalence of student teacher’s musical skills with the objects and contents of the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (FNBE Citation2014). The main problem ‘Does the primary school teacher education provide student teachers with adequate musical skills to implement the National Core Curriculum?’ is examined with the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the amount of different music making contents (singing, playing, moving, listening, and composing) in primary school teacher education?

RQ2: How sufficient do students consider their musical skills to teach music?

RQ3: How strongly do primary school teacher education, and previous musical activities affect students’ musical skills?

The first research question describes and compares the amount of music studies in all five teacher training units based on student evaluations. The responses to these are explanatory variables in the third research question. In the second research question, students’ musical skills are both self-assessed and measured. The third research question compares the amount of music education and the impact of students’ previous musical background on musical skills.

Participants

Of the eight teacher training departments (units) in Finland, five participated in the study: Unit A (n = 82); Unit B (n = 93); Unit C (n = 62); Unit D (n = 88) and Unit E (n = 67). They formed a purposive sample that ensured that it was geographically representative (Vogt Citation2007). The sample consisted of second-year student teachers (n = 392), who had completed the compulsory music studies (3–6 ECTS). Of the sample, 84% were female and 16% were male. Based on previous music activities (see also, next chapter), the students were divided into five categories: no previous music activities (24%); a little (33%) moderate (22%); a lot (14%) and very much (7%). This is an important variable relating to the third research question.

Research instrument

The survey instrument was developed specifically for this study by the authors of this paper who have been teaching music at the teacher training departments for some decades. The survey was mainly based on the goals and contents laid down for music teaching in the National Core Curriculum (FNBE Citation2014). The survey was piloted twice because it was very important to ensure the clarity of all questions. The first pilot study was carried out with a few students in Jyväskylä and Tampere, after which some changes were made to the survey. The final version was piloted with a larger group (n = 20). The pen-and-paper survey consisted of 47 items that were divided into five sections. Responses were provided on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with the exception of the piano chord test.

Previous musical activities, 10 items.

The amount of music making contents in teacher education, 7 items ()

Students’ self-assessed musical skills, 14 items ()

Piano accompaniment skills, 3 items (Appendix, and )

Piano chord test, 13 items (one point for each correct note)

In the first section, students responded to questions containing information about their previous musical activities: regular instrument learning, playing in a band and an orchestra, singing in a choir, singing lessons and Degrees in Music. The theoretical range of sum scores was 10–50. In the second section, students estimated the amount of different music making contents (singing, playing, listening, moving and composing) in primary teacher education. The musical skills were self-assessed in an assignment in which the contents of music making were modified into statements (e.g. ‘I can play chords on guitar’). The piano accompaniment skills were assessed using three school songs of varying degrees of difficulty. The students estimated the time needed to learn how to accompany the song. In a measured chord task, students were asked to identify on a keyboard graphic the following chords: C and D major, E minor and G7 (sum score from 0 to 13).

The research data was collected using a group-administered questionnaire with a rather large group of students gathering to complete the questionnaire simultaneously under the guidance of the researcher. The key advantages in this method are a high response rate and the uniformity of the research events in every teacher training unit (Gravetter and Forzano Citation2016; Whitley and Kite Citation2018). The ethical issues of the study were carefully considered. For students, participation was completely voluntary, and they responded anonymously to the survey. Students were also made aware that answering the survey did not affect the assessment of their music studies in any way. According to the guidelines of the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity TENK (TENK Citation2019) separate ethical approval was not required.

Statistical method and reliability

The data was analysed using descriptive indicators (mean values, standard deviations, percentages and diagrams) typical of quantitative research. The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was applied in the determination of dependences. It should be noted that because of the large sample size (n = 392), almost all correlation coefficients are statistically very significant in this study. However, it does not mean that the relationship is significant in practice or scientifically (Cumming Citation2012). For example, the correlation coefficient of r = .21 (see ) is already statistically significant but it only explains 4.4% (r² = .044) of the relationship between two variables. To describe the real relationship, we use a classification typical in educational sciences: r .20 = weak; r .40 = moderate; and r .60 = strong relationship (Gall, Gall, and Borg Citation2007).

The internal homogeneity of the survey was determined by Cronbach’s alfa (Whitley and Kite Citation2018), which proved to be high: (1) Music activities α = .900, (2) Music making contents α = .892, (3) and Self-assessed music skills α = .944. Internal homogeneity was not sensible to determine for both the accompaniment section (only three items) and chord test (dichotomous response). Instead, students’ assessments of the time needed to accompany the three songs and the measured chore task were strongly correlated: song A = r .57; song B = r .62 and song C = r .56 (see ). The result is important, because it indicates the reliability of students’ self-assessment in piano accompaniment (alternative form reliability, Kubiszyn and Borich Citation2013). Self-assessment can be considered a reliable method if the criteria are clear (Kelvin Citation2012). In this study, it has been an important starting point in compiling the entire survey. In Finnish universities, self-assessment has been identified as a key and a reliable method for students evaluating or developing their own education.

Results

RQ1: the amount of different music making contents in primary teacher education

Students estimated the amount of different music making contents – singing, playing, moving, composing and listening – from ‘none’ (1) to ‘a lot’ (5). shows the range of means between the five teacher training units (A–E) and means and standard deviations of the whole sample (n = 392).

Table 1. The amount of different music making contents in primary teacher education (n = 392).

Singing (O1). According to students’ estimates, the amount of singing and use of natural voice varied considerably between the units (M = 1.79–3.66) and it was addressed adequately in only one unit. About half of the students (54%) estimated the amount of singing and use of natural voice as low or non-existent in music studies.

Playing instruments (O2). All teacher training units emphasised playing class instruments. This is evidenced by the small range of means and the low standard deviation. A substantial proportion of students (66%) estimated that class instruments included quite a lot or a lot in music studies. In contrast, there was significantly less band playing.

Moving (O3). Expressing music through movement was rated the second highest content. It seems obvious that moving (also body percussion) is an important and useful method in learning different concepts or phenomena in music.

Composing (O4). The number of creative musical activities, such as composing or improvising, proved to be considerably below moderate (M = 3.00). In some units, there were no opportunities to create individual music at all and only a small group of students (16%) had more experience in this content.

Listening (O5). There was also little music listening, with the except of one teacher training unit, where students also listened to quite a lot of western classical music. Between the units, the range of means in music listening was considerable (M = 1.60–3.17).

According to the results, music studies in primary teacher education are characterised by an abundant practice of playing class instruments. In contrast, there is significantly less singing and use of the natural voice. It should also be noted that music listening and composing received little attention in most of the teacher training units.

RQ2 and RQ3: students’ musical skills

Students self-assessed their musical skills through statements. The alternatives of the responses were: I cannot (1); I can a little (2); moderately; (3), quite well (4) and well (5). indicates self-assessed musical skills (M, SD), and their correlations r (e) between the amounts of contents (see ) and previous musical activity r (a). As mentioned earlier, students were divided into five categories: no music activities (24%); a little (33%); moderate (22%); a lot (14%) and very much (7%).

Table 2. Students’ (n = 392) self-assessed musical skills (M, SD) and the correlation between the amount of music education r (e) and previous musical activity r (a).

Singing (O1). Students’ ability to sing the melody in accurate pitch was moderate. About one-fifth (22%) rated themselves as good singers and a little less (18%) as non-vocalists. Since one teacher training unit had clearly profiled in singing, this was also reflected in students’ corresponding skills (r = .49). Instead, the ability to sing in accurate pitch (r = .25) may not develop during the brief period of studies and for this reason the correlation with previous music activities was stronger (r = .57).

Playing class instruments (O2.1). Students mastered class instruments slightly above average and there were no major differences in their skills among the different instruments. The strength of the correlation coefficient between the amount of playing class instruments and students’ playing skills were close to weak.

Playing band instruments (O2.2). In this content area, students’ ability to play chords on keyboard was strongest (M = 3.49). Students also managed quite well in playing the basic comp with drums (4/4 beat). It should be noted that the amount of playing band instruments correlated very weakly with students’ ability to play (piano) chords. Indeed, it would appear, that chord playing skills are affected by the number of piano lessons (from 10 to 22 h), which is discussed later. The playing skills of both class and band instruments were influenced more by students’ previous music activities than music studies in teacher education.

Moving (O3) and Composing (O4). The students’ skills in moving and body rhythm clearly exceeded the average level and the amount of education correlated slightly more with skills than previous hobbies. Instead, the ability to create own music (improvise or compose) was relatively low in all teacher training units and only a small proportion of students (7%) rated their skills as good. The correlation coefficient with previous music activities proved clear (r = .49).

Listening (O5). Students’ knowledge of the music of other countries and the eras of western music history was limited. As there was clearly more listening to music in one of the teacher training units, students’ corresponding skills also proved to be better. However, the strength of the correlation coefficient (r = .28) is not exactly strong. Instead, previous musical activities affected moderately on the knowledge of Western art music.

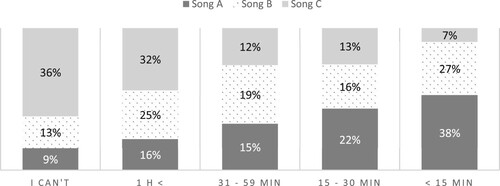

Piano accompaniment skills were assessed using three school songs of varying degrees of difficulty (Appendix). Students estimated the required rehearsal time to learn the accompaniments: I cannot accompany (1); I need to rehearse more than an hour (2); 31–59 min (3); 15–30 min (4) and less than 15 min (5).

Song A is a typical children’s song for grades 1–2 and 60% of the students estimated they need a maximum of 30 min of practice time. A Finnish folk song (B) for grades 3–4, proved to be more difficult, with 43% of the students estimating they would learn it in less than 30 min. A short excerpt from Bach’s Matthew Passion (C) for grades 5–6, proved to be ‘easy’ for only 20% of the students.

In the measured chord test, the students marked the correct tones of the chords on the keyboard image: C and D major, E minor and G7. One point was awarded for each correct tone (sum score 0–13 points). The result (M = 7.4, SD = 4.7) indicates, that the students knew seven tones, which means ‘just over two chords’. The result is only moderate, even in the case of basic chords, such as C (60.45% correct) and D major (44.38% correct) ().

Table 3. Students’ (n = 392) measured chord test: percentages of correct tones.

The number of hours of piano lessons (from 10 to 22 h) in teacher education was quite important to the students’ ability to play chords (r = .36) but no longer to the ability to accompany the songs A–C. In these cases, too, the student’s previous musical activity proved to be a significant factor in explaining playing skills ().

Table 4. Students’ (n = 392) piano accompaniment skills’ correlations to the number of piano lessons in primary teacher education and students’ previous musical activity.

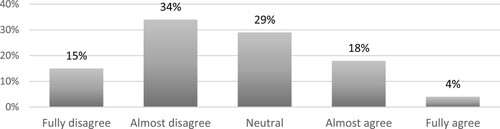

In conclusion, student teachers’ musical skills proved to be ‘moderate’ at most and there were significant differences between students as well as the teacher training units. A student’s previous hobby would seem to have a significantly greater impact on skills than the music education in primary teacher training. However, the strength of correlation coefficient between the students’ musical skills and the number of music education credits (from 3 to 6 ECTS) is nearly moderate (r = .34). However, in general, students were not satisfied with their education, as only 4% fully agreed with the statement: ‘The primary school teacher education has given me good musical skills to teach music’ ().

Discussion

The present study complemented Juntunen’s (Citation2017) research by focusing on primary school teacher education and student teachers’ musical skills. The results indicate that teacher education in Finland is not able to provide all students with sufficient musical skills to teach music according to the National Core Curriculum (FNBE Citation2014). Due to the limited time and credits offered per course (5 ECTS) in music programmes, many key content areas of music making are insufficiently addressed or overlooked. In most cases, musical skills have already been acquired through students’ previous musical activities (Rosa-Napal et al. Citation2021; Saetre Citation2018); however, that experience and training are not considered in teacher training entrance exams (Juntunen Citation2017).

Currently, the emphasis on primary teacher education is on playing class instruments, which means that less attention is paid to listening, singing and composing. The small share of lessons of singing in school music has also emerged in the Nordic countries and Australia but it still has a strong role in the Baltic countries (Sepp, Ruokonen, and Ruismäki Citation2015; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015). However, a teacher has a great responsibility in teaching singing, as the evolving vocal system of a child may be damaged by incorrect teaching methods (Lamont, Daubney, and Spruce Citation2012; Phillips and Doneski Citation2011). Therefore, much more attention should be paid to the technique of natural vocal use and singing in teacher education, as a teacher’s correct example has been shown to have a key effect on pupils’ learning (Elliott and Silverman Citation2015; Georgii-Hemming Citation2013; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015).

Furthermore, the amount of creative musical activity lessons was inadequate. However, composing is one of the most useful methods teachers can use in classrooms as it benefits all pupils regardless of musical background (Burnard Citation2013; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015). It is important to consider all students as capable of creating their own music. Providing children with opportunities to participate in creative processes can support their faith in their own musical abilities (Burnard Citation2013; Muhonen Citation2016). Through more creative musical experiences in primary teacher education, students could gain new understandings of music education practices that they can later utilise in their own music teaching (Kenny Citation2017).

Music listening skills remained also marginal. However, it could prove to be an important tool in music teaching, especially for less musically skilled teachers. It seems that school music education does not pay enough attention to the significance of listening to music (Anttila Citation2010). However, pupils do listen to a great deal of music together outside of school. Similar interactive listening situations should also be organised in school music, where pupils evaluate and present their opinions on the music they hear (Dunn Citation2011; Smialek and Boburka Citation2006). Therefore, music teachers should be familiar with a relatively wide musical repertoire and understand the meanings conveyed by musical works so that music can further give meaning to pupils (Dunn Citation2011; Jorgensen Citation2008; Russell-Bowie Citation2009). We may ask, is music listening realised in school music only with teachers who listen to (art) music, for whom music is especially important and who are also able to guide pupils to experience musical meanings?

In Finland, it is expected that a general primary school teacher can accompany at least easy school songs (Ketovuori Citation2015; Vesioja Citation2006). Although students’ accompaniment skills proved to be moderate for grades 1–2, almost half of the students (45%), questioned their skills to accompany songs in these grades. In the case of teachers, it is not only about accompaniment skills, for piano playing skills serve as an important tool in opening the music curriculum’s diversity and phenomena of musical world to the pupils.

Students’ prior musical activities had a significantly stronger impact on skills than primary school teacher education. The results are remarkably like previous studies (Atkinson Citation2018; Kenny Citation2017; Saetre Citation2018). One of the key reasons is the limited amount of contact teaching which reduces students’ potential to implement the curriculum later in actual music teaching (Russell-Bowie Citation2009; Thorn and Brasche Citation2015). Therefore, students need much more practical experience for their own musical learning (Hennessy Citation2017) and they need more creative challenges in order for meaningful learning to happen (Kenny Citation2017; Suomi and Ruismäki Citation2021). It is essential that primary school teacher education could provide these important factors in musical development for all students in the future.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that for a large proportion of student teachers, musical skills are insufficient to implement the National Core Curriculum in music. The findings must be taken seriously, and they can also be generalised because of the large sample size (n = 392). If implemented, the music curriculum could ‘create opportunities for versatile music activities’, which is one of the main tasks of the subject of music (FNBE Citation2014, 348). According to the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (1989) and its General Comments, especially No. 17 (CRC Citation2013), children’s participation in cultural life and the arts is of utmost importance. This should also be considered in primary school, as it is the only institution where all children have the opportunities to participate in music education. The gap between the policy programmes and their practical implementation (Buck and Snook Citation2016; Russell-Bowie Citation2009) must not be accepted any longer. As the music content in the National Core Curriculum is so extensive we may ask if subject teachers should teach music in all basic education (also grades 1–6). Nonetheless, every child has the right to versatile music making, such as singing, playing various instruments, listening to a wide range of music styles, composing their own music and especially enjoying the positive feelings that arise from music in all its forms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Henna Suomi

Henna Suomi PhD is Post-Doctoral Researcher in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä. She is working at the Department of Music, Arts, and Culture Studies. Suomi’s research interests are music education, primary school teacher education, music composing in primary school, and music curriculum. She has worked as a class teacher specialising in music for 20 years in comprehensive schools and in primary school teacher education.

Lenita Hietanen

Lenita Hietanen PhD is Adjunct Professor in Entrepreneurship Education in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä and University Lecturer in Music Education in the Faculty of Education at the University of Lapland in Finland. Hietanen’s research interests are music education, entrepreneurship education, teaching and learning in general, and social and societal equality.

Heikki Ruismäki

Heikki Ruismäki PhD is Professor in the Faculty of Educational Sciences at the University of Helsinki. His research interests are teacher education, music education and its development, music technology, music teachers’ well-being, pedagogic possession of music as a school subject, entrepreneurship education, and arts education in general.

References

- Anttila, Mikko. 2010. “Problems in School Music in Finland.” British Journal of Music Education 27 (3): 241–253.

- Atkinson, Ruth. 2018. “The Pedagogy of Primary Music Teaching: Talking About Not Talking.” Music Education Research 20 (3): 267–276.

- Buck, Ralph, and Barbara Snook. 2016. “Teaching the Arts Across the Curriculum: Meanings, Policy and Practice.” International Journal of Education & the Arts 17 (29): 1–21.

- Burak, Sabahat. 2019. “Self-Efficacy of Pre-School and Primary School Pre-Service Teachers in Musical Ability and Music Teaching.” International Journal of Music Education 37 (2): 257–271.

- Burnard, Pamela. 2013. Musical Creativities in Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). 2013. General Comment No. 17. https://www.refworld.org./docid/51ef9bcc4.html.

- Cumming, Geoff. 2012. Understanding the New Statistics. Effect Sizes, Confidence Intervals, and Meta-Analysis. New York: Routledge.

- Dunn, Rob, E. 2011. “Contemporary Research on Music Listening. A Holistic View.” In MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning. Volume 2: Applications, edited by Richard Colwell, and Peter Webster, 3–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, David J., and Marissa Silverman. 2015. Music Matters. A Philosophy of Music Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- FNBE. 2014. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. Finnish National Board of Education. https://kosovo.finnish.school/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Basic-Education-Grades-1-9.pdf.

- Gall, Meredith D., Joyce P. Gall, and Walter R. Borg. 2007. Educational Research. An Introduction. Boston: Pearson.

- Georgii-Hemming, Eva. 2013. “Music as Knowledge in an Educational Context.” In Professional Knowledge in Music Teacher Education, edited by Eva Georgii-Hemming, Pamela Burnard, and Sven-Erik Holgersen, 19–37. Surrey: Ashgate.

- Government Decree. 2018. “Valtioneuvoston asetus (793/2018) perusopetuslaissa tarkoitetun opetuksen valtakunnallisista tavoitteista ja perusopetuksen tuntijaosta annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen 6 §:n muuttamisesta [Government Decree (793/2018) amending Article 6 of the Government Decree on the National Objectives of Teaching and the Allocation of Lessons in Basic Education].” https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2018/20180793.

- Gravetter, Frederik, J., and Lori-Ann B. Forzano. 2016. Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Henley, Jennie. 2017. “How Musical are Primary Generalist Student Teachers?” Music Education Research 19 (4): 470–484.

- Hennessy, Sarah. 2017. “Approaches to Increasing the Competence and Confidence of Student Teachers to Teach Music in Primary Schools.” Education 45 (6): 689–700.

- Hietanen, Lenita, Matti Koiranen, and Heikki Ruismäki. 2017. “Enhancing Primary School Student Teachers’ Psychological Ownership in Teaching Music.” In Theoretical Orientations and Practical Applications of Psychological Ownership, edited by Chantal Olckers, Llewellyn van Zyl, and Leoni van der Vaart, 229–248. Cham: Springer.

- Holden, Hilary, and Stuart Button. 2006. “The Teaching of Music in the Primary School by the Non-Music Specialist.” British Journal of Music Education 23 (1): 23–38.

- Jorgensen, Estelle. 2008. The Art of Teaching Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Juntunen, Marja-Leena. 2017. “National Assessment Meet Teacher Autonomy: National Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Music in Finnish Basic Education.” Music Education Research 19 (1): 1–16.

- Kelvin, Tan Heng Kiat. 2012. Student Self-Assessment: Assessment, Learning and Empowerment. Singapore: Research Publishing.

- Kenny, Ailbhe. 2017. “Beginning a Journey with Music Education: Voices from Pre-Service Primary Teachers.” Music Education Research 19 (2): 111–122.

- Ketovuori, Mikko. 2015. “With the Eye and the Ear—Analytical and Intuitive Approaches in Piano Playing by Finnish Teacher Candidates.” International Journal of Music Education 33 (2): 133–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415569117.

- Kubiszyn, Tom, and Gary D. Borich. 2013. Educational Testing and Measurement. Classroom Application and Practice. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

- Lamont, Alexandra, Alison Daubney, and Gary Spruce. 2012. “Singing in Primary Schools: Case Studies of Good Practice in Whole Class Vocal Tuition.” British Journal of Music Education 29 (2): 251–268.

- Lummis, Geoff W., Julia Morris, and Annamaria Paolino. 2014. “An Investigation of Western Australian Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Experiences and Self-Efficacy in the Arts.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (5): 50–64.

- Mäkinen, Minna, and Antti Juvonen. 2017. “Can I Survive This? Future Class Teachers’ Expectations, Hopes, and Fears Towards Music Teaching.” Problems in Music Pedagogy 16 (1): 49–61.

- Moore, Gwen. 2019. “Musical Futures in Ireland: Findings from a Pilot Study in Primary and Secondary Schools.” Music Education Research 21 (3): 243–256.

- Muhonen, Sari. 2016. “Songcrafting Practice: A Teacher Inquiry into the Potential to Support Collaborative Creation and Creative Agency Within School Music Education.” PhD diss., University of the Arts Helsinki.

- Niemi, Hannele. 2011. “Educating Student Teachers to Become High Quality Professionals – A Finnish Case.” Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 1 (1): 43–66.

- Ornstein, Allan C., and Francis B. Hunkins. 2018. Curriculum Foundations, Principles, and Issues. Harlow: Pearson.

- Phillips, Kenneth, H., and Sandra M. Doneski. 2011. “Research on Elementary and Secondary School Singing.” In MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning Applications. Volume 2: Applications, edited by Richard Colwell, and Peter Webster, 176–232. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rosa-Napal, Fransisco, C. Pablo-César Munoz-Carril, Mercedes González-Sanmamed, and Isabel R. Tabeayo. 2021. “Musical Expression in the Training of Future Primary Teachers in Galicia.” International Journal of Music Education 39 (1): 50–65.

- Russell-Bowie, Deirdre. 2009. “What Me? Teach Music to My Primary Class? Challenges to Teaching Music in Primary Schools in Five Countries.” Music Education Research 11 (1): 23–36.

- Saarelainen, Juha, and Antti Juvonen. 2017. “Competence Requirements in Finnish Curriculum for Primary School Music Education.” Problems in Music Pedagogy 16 (1): 7–19.

- Saetre, Jon H. 2018. “Why School Music Teachers Teach the Way They Do: A Search for Statistical Regularities.” Music Education Research 20 (5): 546–559.

- Sahlberg, Pasi. 2011. Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? New York: Teachers College Press.

- Salminen, Jaanet, and Tiina Annevirta. 2014. “Opetussuunnitelman Perusteiden Välittämä Ohjaus – Mitä, Kenelle ja Miksi? [Guidance Conveyed by the Basics of the Curriculum – What, to Whom and Why?].” Kasvatus 45 (4): 333–348.

- Sepp, Anu, Lenita Hietanen, Jukka Enbuska, Vesa Tuisku, Inkeri Ruokonen, and Heikki Ruismäki. 2018. “University Music Educators Creating Piano-Learning Environments in Finnish Primary School Teacher Education.” The European Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences EJSBS XXIV: 2301–2218.

- Sepp, Anu, Inkeri Ruokonen, and Heikki Ruismäki. 2015. “Musical Practices and Methods in Music Lessons: A Comparative Study of Estonian and Finnish General Music Education.” Music Education Research 17 (3): 340–358.

- Smialek, Thomas, and Renee R. Boburka. 2006. “The Effect of Cooperative Listening Exercises on the Critical Listening Skills of College Music-Appreciation Students.” Journal of Research in Music Education 54 (1): 57–72.

- Suomi, Henna, and Heikki Ruismäki. 2021. “Musiikin opetussuunnitelman laaja-alaisuus haasteena luokanopettajakoulutuksessa [The Breadth of the Music Curriculum is a Challenge in Primary School Teacher Education].” Conference Paper. The Finnish Educational Research Association (FERA) Conference of Education 25.11.2021. https://www.jyu.fi/en/congress/kasvatustieteenpaivat2021/days/kt-2021-abstraktikirja-18-11-21-_paivitetty-26-11.pdf.

- TENK. 2019. “Guidelines for Ethical Review in Human Sciences in Finland. Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK Guidelines 2019.” Accessed 8 July 2020. https://tenk.fi/en/advice-and-materials/guidelines-ethical-review-human-sciences.

- Tervaniemi, Mari, Sha Tao, and Minna Huotilainen. 2018. “Promises of Music in Education?” Frontier Education 3: 74. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00074.

- Thomson, Katja, and Johanna Lehtinen-Schnabel. 2019. “Where are the Teachers? Reflecting on the Language of the Finnish (Music) Core Curriculum for Basic Education.” Finnish Journal of Music Education 22 (1–2): 110–118.

- Thorn, Benjamin, and Inga Brasche. 2015. “Musical Experience and Confidence of Pre-Service Primary Teachers.” Australian Journal of Music Education 48 (2): 191–203.

- Vesioja, Terhi. 2006. “Luokanopettaja musiikkikasvattajana [Class Teacher as a Music Educator].” PhD diss., University of Eastern Finland.

- Vitikka, Erja, Jaanet Salminen, and Tiina Uusivirta. 2012. “Opetussuunnitelma opettajankoulutuksessa. Opetussuunnitelman käsittely opettajankoulutusten opetussuunnitelmissa. Muistiot 12:4. Opetushallitus [Curriculum in Teacher Education. Curriculum Processing in Teacher Education Curricula. Memorandum 12:4. Finnish National Board of Education].”

- Vogt, W. Paul. 2007. Quantitative Research Methods for Professionals. Boston: Pearson.

- Vries, de Peter. 2013. “Generalist Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in Primary School Music Teaching.” Music Education Research 15 (4): 375–391.

- Whitley, Bernard E., and Mary E. Kite. 2018. Principles of Research in Behavioral Science. New York: Routledge.

Appendix

SONG A (grades 1–2)

SONG B (grades 3–4)

SONG C (grades 5–6)