ABSTRACT

Current international trends in curriculum design tend to advocate an approach which defines broad ‘competences’ rather than disciplinary content or skills, encouraging the making of connections between subject disciplines. This article discusses the results of a survey of 75 secondary music teachers in Wales, a nation which is in the early stages of implementing a new curriculum framework. The survey sought to form an impression of the musical backgrounds and training of the teachers, their pedagogic beliefs about classroom music, and their attitudes towards the values embodied in their new national curriculum. The responses from music teachers suggested that the majority had been musically educated in the Western ‘classical’ tradition at university, but their beliefs about teaching music in the classroom indicated that they had moved beyond the conception of the subject embodied in their own higher education, to a more holistic, practical conception in which pupils learn by doing. While a significant body of literature suggests the existence of a gap between the musical values of classroom music teachers and those of their pupils, the teachers surveyed for this research indicated that they tend to prioritise the development of transferable creativity skills over the production of excellent musicians. .

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Recent international reports about the nature of curricula argue that their design needs to move away from defining content or skills and be conceptualised in terms of more broadly defined competences (OECD Citation2018) – although it has been argued that these can be ‘generic and free-floating, independent of knowledge and content’ (Deng Citation2021, 188). Responding to concerns expressed by the OECD (e.g. OECD Citation2018) about the suitability of existing curricula for preparing young people to participate successfully in the modern world, there have been a number of recent curricula designs which place attributes, referred to as ‘capacities’ (Education Scotland Citation2019), ‘competencies’ (New Zealand Ministry of Education Citation2015), ‘purposes’ (Welsh Government Citation2020a) or similar, at the core of a curriculum, with traditionally discrete subject disciplines grouped into larger ‘areas’. These areas explicitly encourage the creation of connections between subject disciplines, in the belief that this will improve the quality of learning and enable learners to develop the competences defined in the curricula (Education Scotland Citation2019; New Zealand Ministry of Education Citation2015, 16; Welsh Government Citation2020b). Music has not been exempt from such developments.

This article reports the results of a survey of 75 secondary school music teachers in Wales who are in the early stages of implementation of a new curriculum. It is important to note that this curriculum decentralisation (Mikser, Kärner, and Krull Citation2016) was led by a ‘pioneer’ teachers in a ‘genuine rather than contrived process of engagement’ (Sinnema, Nieveen and Priestley Citation2020, 181) and ‘sets a bold direction for teaching and learning in Wales’ (197). This new curriculum explicitly defines central ‘purposes’ and groups the music subject discipline with art, dance, drama and film & digital media into an expressive arts ‘Area of Learning and Experience’ (AoLE) (Welsh Government Citation2020c). The survey sought to discover secondary music teachers’ attitudes towards the idea of making connections with other subject disciplines and pursuing broadly defined competences, such as ‘creating new value’ (OECD Citation2018, 5). The survey sought to contextualise these views with musical background and training of the teachers, and their attitudes towards the teaching of the subject discipline, to investigate whether previously stated concerns about a gap between the ‘habitus’ of secondary music teachers and the needs of their learners (Wright Citation2008a), or a tendency to over-prioritise high-quality musical outcomes over pupils’ wellbeing (Regelski Citation2012), might affect teachers’ attitudes towards these new curriculum trends.

Literature review

Music pedagogy

The first attempt to introduce a national curriculum in England and Wales took place as a result of the Education Reform Act (Education Reform Act Citation1988). Since the introduction of the national curriculum – before control over education was devolved to Wales in 1999 – classroom music in Wales has had a different curriculum to its English counterpart. This was the result of heated debate in the UK between musicians, educators and politicians, reflecting both musical and political arguments. In music, Swanwick’s conception (Citation1979, Citation1988) of music as a practical subject, while also reflecting the musical heritage of Wales (Beauchamp Citation1995), where pupils learned by doing (a holistic mix of performing, composing and appraising), was pitted against an approach which gave increased prominence to music appreciation and ‘theory’ (Rainbow and Cox Citation2006, 367). While Wales adopted the Swanwick approach (Gammon Citation2006, 132), England’s curriculum design process produced a compromise between the two approaches (Gammon Citation2006, 140–141). Even in the latest iteration of the music curriculum in England, references to ‘great works’ and the ‘canon’ remain in contrast to the Welsh approach (Bate Citation2020, 5–9), so consideration of the pedagogic attitudes and perceptions arising from this survey should bear this historical divide in mind.

Since Swanwick outlined his conception of music education (Citation1979, Citation1988, Citation1999), competing philosophical positions for music have been noticeable by their absence. Green’s proposal that a more ‘horizontal’ informal approach, which more closely mirrors the working practices of popular music groups (Citation2002; Citation2008), led to the creation of the Musical Futures organisation to promote and support this approach. But it arguably does not provide a significantly contradictory view of music education to Swanwick, since it is similarly holistic and practical in nature. Meanwhile, Wright (Citation2014) proposes approaches to teaching music which ‘interrupt’ the normal order of things so that pupils can create ‘discursive gaps (where official knowledge is “up for grabs”)’ (23). Bate (Citation2020) further suggests that teachers encourage pupils to challenge the vertical authority of the ‘canon’, to propose and justify their own canon (12). These contributions, however, could be argued to be in broad agreement with Swanwick’s rejection of an imposed ‘appreciation’ of ‘great music’ (Bate Citation2020, 8), rather than a challenge to the dominance of his ideas.

Secondary music teachers

In the case of music at the secondary school level, a significant body of literature spanning several decades – for example Vulliamy (Citation1977) and Wright (Citation2008b) – questions the extent to which there is a ‘gap’ between the values and beliefs of teachers in relation to music, and those of the pupils they teach. In considering this, McPhail (Citation2015) suggests that ‘multiple discourses, knowledge structures, and identities create a problem that may be unique to music within the secondary curriculum’ (1154). Responding to this complexity, various authors have proposed a number of sociological theories as lenses through which to understand the nature of the subject (e.g. McPhail Citation2015; McPhail and McNeill Citation2019; Swanwick Citation1988, 122), or suggest new ones to make sense of its complexities (Wright Citation2014). Many secondary music teachers in the UK undertake a one-year PGCE programme leading to qualified teacher status (QTS) after a three or four-year music degree. In this case, the ‘pure’ subject knowledge of music is learned first in the music degree, with the pedagogic aspects coming afterwards, and separately from the learning of subject knowledge, in the PGCE. Some authors, such as Wright (Citation2008a), propose that, since the majority of teachers’ initial musical training is rooted in the western classical tradition, this can lead to their values being at odds with those of the majority of their pupils. Wright (Citation2008a) uses a theoretical framework drawn from the work of Bourdieu (1984 cited in Wright Citation2008a) and Bernstein (1971, 1990 cited in Wright Citation2008a) to document an attempt by a music teacher to transcend her western classical habitus by providing a music experience for her pupils that is based on the collective performance of musical arrangements. This included pieces that she judged were of contemporary interest. However, Wright points out that this teacher still retains strong control over the classification and framing of the learning, which is a contributory factor in a majority of pupils in her class describing the experience as not ‘real music’. More recently, Dwyer (Citation2019) presents a series of narrative enquiries into music teachers in Australia which make similar points: that the music teacher’s training and musical background can leave them unaware that aspects of their approach to teaching reveal their habitus and have an impact on the authenticity of the pupils’ experience. Richardson (Citation2003) outlines research which conclude that it is difficult to change the beliefs which new teachers bring with them to the teaching profession, which ‘relate strongly to the form of teaching they have experienced’ (2). Swanwick’s contention that we hear everyone’s accent but our own (Swanwick Citation1999, 22) is worth bearing in mind in relation to his own work here. It raises interesting questions which stem from recognising the long-standing dominance of Swanwick’s theories of how young people should learn music, when set against the learning experiences that many music teachers are themselves likely to have experienced while studying music at degree level – a level in which music has an élite code which calls for both the right kind of knowledge and the right kind of knower in order for the learner to succeed (Maton Citation2014).

New trends in curriculum design

Writing for UNESCO, Marope (Citation2013) outlines a need for a reconceptualisation of the curriculum to meet the demands of the twenty-first century. Specifically, Marope refers to the changing new demands of employment, in which the specific skills and knowledge that people may need to remain gainfully employed throughout their working life may shift so quickly that it is not feasible to impart these during a person’s schooling. This implies the need to imbue learners with competences, developing in them the ability to be lifelong learners, with the aptitudes to evolve their skills and knowledge to keep up with a rapidly changing world.

In seeking to reconceptualise curriculum, and considering both developing and developed countries, Marope (Citation2013) sets out eight ‘dimensions’ (29) for a twenty-first-century curriculum. These range from idealistic (‘a force for social equity, justice, cohesion, stability, and peace’) (31) to more pragmatic (‘a determinant of key cost drivers in education and learning systems’) (34). Accordingly, when looking at learners themselves, Marope, Griffin, and Gallagher (Citation2017) contend that the aims of a curriculum cannot be bound within specific subject disciplines and their associated knowledge and skills, but must be rooted in more aspirational competences, which are more centred in creativity and collaboration. In 2018, the OECD (Citation2018, 5) proposed three transformative competences transcending subject disciplines as part of its Education 2030 agenda, namely:

Creating new value,

Reconciling tensions and dilemmas,

Taking responsibility.

In the same vein, the new Curriculum for Wales favours an ‘integrated’ approach (Welsh Government Citation2020d) where subjects are organisedinto areas, including an AoLE for the expressive arts. The curriculum document for this AoLE (Welsh Government Citation2020a) was co-constructed by a group of ‘pioneer’ teachers, whose schools received funding to release them from the classroom to create the document. During this process, teachers in the expressive arts pioneer group noted particular difficulties concerning how to integrate multiple subject disciplines into one AoLE, and how the differing perspectives of primary and secondary colleagues presented multiple obstacles. The particular opportunities and challenges which presented themselves during the implementation of this ‘pioneer’ approach to curriculum design are explored in depth in two articles by Kneen et al. (Citation2020, Citation2021). These difficulties and concerns were expressed at the co-construction stage of a new national curriculum framework, the implications of which tended to be restricted to this small group of ‘pioneers’. Thus, it is timely to form a picture of the attitudes and perceptions of a wider group of secondary music subject specialists as the curriculum moves towards a competence-driven approach.

Methods

Due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, face-to-face access to teachers was impossible. Therefore, an online questionnaire was devised to survey Key Stage 3 (pupils aged 11–14 years) (KS3) music teachers’ attitudes towards a number of factors, contextualised by basic factual information about the respondents themselves. KS3 was selected as in Wales, music is a compulsory subject for children to the age of 14 and thus teachers involved in teaching this age group would embrace the full intention of the new curriculum development.

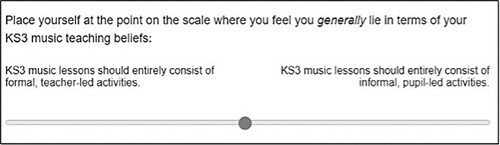

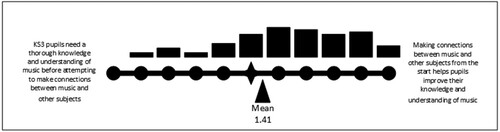

A central aim of the questionnaire was to gain an impression of the attitudes and beliefs of the music teachers in relation to a number of key concepts relating to music pedagogy, pedagogy more widely, and aspects of the new ‘competences’ being defined by the OECD. These Likert-style questions required teachers to place themselves at an appropriate point along a continuum, with opposing statements at each end. The questions examined aspects of Bernstein’s classification and framing cited in Swanwick (Citation1988), ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’ discourse (Bernstein 2000; cited in McPhail Citation2015) and, drawing on the work of Maton (Citation2014), the specialisation codes defined by McPhail and McNeill (Citation2019). An exemplar of a statement in the survey is given in , showing the two extreme positions presented to respondents on a continuum.

Figure 1. An example statement from the survey. Respondents were asked to place themselves on a continuum between two opposing positions.

Attitudinal questions using the same format then followed, examining respondents’ attitudes towards: the interdisciplinary working required in the new curriculum; the relative importance of disciplinary knowledge versus the more widely framed ‘purposes’ of the new curriculum; and the transformative competences defined by OECD (Citation2018).

Finally, satisfaction levels among respondent teachers were gathered in terms of: the extent to which they felt pupils had access to develop the transformative competences; how positive they felt about the interdisciplinary approaches implied by the creation of the AoLEs; and the extent to which they felt that the new curriculum would change what they did in the classroom in the next five years.

Ethics

The author sought ethical approval for this research from the research ethics committee of Cardiff School of Education and Social Policy on 11 December 2019, and following some further clarification to the committee, was granted approval to proceed with distribution of the questionnaire on 23 January 2020. The approval number was CSESP20192006. Participants’ informed consent was obtained through an information page at the start of the questionnaire, with tick-boxes to indicate participants’ consent. Proceeding to the survey was only possible once the boxes had been ticked.

Sample

Email addresses for all mainstream secondary schools (English and Welsh-medium) in Wales were gathered using local authority websites, and a link to the questionnaire was sent to the school’s main email address, requesting that it be forwarded to all music teachers in the school. Two follow-up reminders were sent before the questionnaire was closed to new responses. A total of 75 completed responses were received from a possible 205 schools. While it was not possible to know precisely how many music teachers were employed by these 205 schools, from experience of working with school music departments, the authors assumed that most schools would employ one or two music teachers. The 75 responses were therefore taken to represent approximately 25% of the available population.

Results

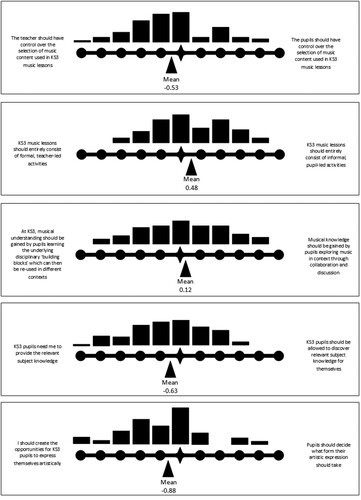

A significant proportion of the completed responses indicated that the teachers had received their music training at a conservatoire or a university offering an academic music programme, as shown in . The instruments identified as principal, second and third studies showed a marked preference for the piano and voice, with ‘orchestral’ instruments also well-represented. In terms of beliefs around music pedagogy, responses could be described as ‘moderate’, with a preference for mildly strong classification and generally mildly strong framing. They showed that teachers favoured a mix of the ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’, with the importance of teacher knowledge (and a ‘knower’ code) given slight emphasis. shows the series of questions relating to these concepts, and responses to all of them can be seen to be clustered around the midpoint, with few responses at the extreme ends of the continuums.

Table 1. Where did you study for your first music degree/diploma?

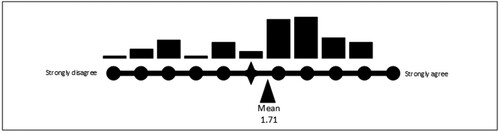

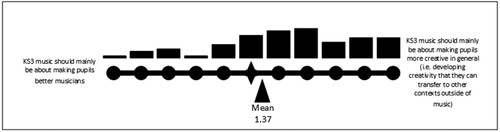

There was a positive response to the idea that music teachers should extend their subject knowledge beyond music (). The responses also indicate that teachers favour the prioritising of transferable creativity over musicianship ().

Figure 2. Respondents were asked to place themselves on a position on a continuum between two statements which best reflected their opinion. These questions related to classification and framing, horizontal vs. vertical discourse, and Maton’s legitimation code theory.

Figure 3. In order to give pupils the best experience in KS3 music, it is vital that KS3 music teachers’ subject knowledge and understanding should extend beyond music and into other relevant subjects.

The responses also indicated () that this sample of teachers agreed that making connections with other subjects from the start helped with understanding the subject of music, and that music (as taught in their departments) offered pupils opportunities to develop the transformative competences defined by the OECD (Citation2018).

Figure 4. Place yourself at the point on the scale where you feel you generally lie in terms of your KS3 music teaching beliefs.

One caveat in relation to the transformative competences was that some dissatisfaction could be discerned in relation to whether the subject as taught allowed pupils to create new material that has value (), an interesting insight into the extent to which music as taught in the classroom mightbe considered a ‘creative’ subject.

Table 2. ‘To what extent to you feel your KS3 music lessons currently give pupils opportunities to:’ and ‘How satisfied are you with this state of affairs?’. Respondents picked a score from 0 to 10.

Discussion

The institutions and instruments identified in the first the questionnaire and summarised in would seem to bear out the observations of Dwyer and others, that classroom music teachers predominantly come to the job having experienced music teaching in their university years which would correspond with Maton’s élite code (Maton Citation2014, 81). Richardson (Citation1996, Citation2003) would suggest such an experience would have a strong impact on these teachers’ own beliefs about music teaching. In terms of subject-specific pedagogic beliefs, the questionnaire results suggest that the music teachers prefer moderately strong classification and framing of the learning experience of their pupils. They believe that the subject needs to be experienced by pupils as a mix between instruction and encounter, with the teacher in control of the process, but not strongly enough to prevent some aspect of pupil discovery and creativity. It is interesting to note that these conceptions of the subject discipline seem to contrast with the more strongly classified and framed approach characterised by a music degree based in the Western classical tradition. This is noteworthy as the institutions which awarded the music degrees of the majority of respondents offer music degrees which accord with this description. If music teachers’ beliefs about the subject have moved beyond those embodied in their university education, this would offer a counterpoint to the argument that teachers find it difficult to make such a transition when joining the profession (Richardson Citation2003).

Also interesting, in light of the musical backgrounds and training of the respondents, is the strongly expressed optimism towards aspects of the new curriculum trends outlined above. The willingness to prioritise transferable creativity skills over creating excellent musicians (Figure 5), and interest in exploring connections between subject disciplines, allay concerns relating to the unethical disposition of ‘musicianism’ (Regelski Citation2012). Kneen et al. (Citation2020, 269) reported that secondary-phase expressive arts ‘pioneers’ (those teachers responsible for co-constructing the new curriculum that teachers involved in this survey are working towards implementing), initially found it challenging to move beyond the belief that their subject discipline was paramount in forming their teaching identity. It is interesting to note a more optimistic view among respondents in this survey to the notion of extending their own subject knowledge beyond the traditional boundaries of the discipline of music – although this does introduce the potential, however, for some subject disciplines to become overly ‘subservient’ to others deemed more important (Wiggins Citation2001, 44).

This move beyond traditional subject boundaries is also reflected in a positive response () to the suggestion that making connections between music and other subject disciplines ‘from the start’ helps pupils improve their knowledge and understanding of music. Such a positive attitude, reflected in classroom teaching, would alleviate concerns that meaningful connections cannot be made between subject disciplines without already being ‘knowledgeable not only about [both subjects] but also about the cultures that surround them’ (Pruitt, Ingram, and Weiss Citation2014, 17). It would not, however, prevent the need to ‘first create a strong, valid, concept-based music curriculum about which there is no compromise’ (Wiggins Citation2001, 44).

Figure 5. Place yourself at the point on the scale where you feel you generally lie in terms of your KS3 music teaching beliefs.

The teachers were also positive about implementing a new curriculum framework, which is more explicitly based on competences. This is supported by their perception that they give pupils opportunities to develop the transformative competences defined by the OECD. This is important as they are key ‘actors’ (Hizli Alkan and Priestley Citation2019) in making, and implementing, the new curriculum at a time of significant ‘institutional and epistemological reframing’ of curriculum policy-making as ‘powerful organisations … have started to promote competence-based approaches’ (Nordin and Sundberg Citation2021, 19). In addition, although working at the micro-level of the classroom, ‘teachers’ singular role within the education system provides them with the power to resist policy change, alter it, or forge new policy on the ground’ (Giudici Citation2021, 805).

Conclusion

This study suggests that KS3 music teachers will indeed, forge new policy on the ground, but they appear open to the aspirations of a new place for music in the curriculum as part of expressive arts area of learning and experience. In doing so, however, they hold firm pedagogic beliefs, which reflect Swanwick’s (Citation1979; Citation1988; Citation1999) conception of music as a holistic, practical subject. In forming these beliefs, they are able to transcend the values and beliefs implicit in their own experience of music education. This willingness to move beyond the values and beliefs internalised during university study of the subject – which is mostly steeped in the Western classical tradition and embodying an élite code – to a more holistic, practical conception of music, suggests that music teachers are open to change. Despite challenges to their subject-based identity expressed by the ‘pioneer’ teachers who co-constructed the new curriculum document for the expressive arts, this wider survey of serving music teachers suggests a willingness to work beyond the boundaries of their specialist discipline. They are optimistic about current curriculum trends, including the development of transferable competences and the creation of connections between subject disciplines. They also consider themselves responsible for moving beyond purely musical outcomes to developing more broadly defined, transferable creativity in their pupils.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Breeze

Thomas Breeze is a Programme Leader for PGCE Secondary Music at Cardiff Metropolitan University. His research interests include the pedagogic beliefs of music teachers, cross-curricular pedagogies in the expressive arts, and how beginning teachers learn within a clinical practice model of initial teacher education.

Gary Beauchamp

Gary Beauchamp is Professor of Education in the School of Education and Social Policy at Cardiff Metropolitan University. He worked for many years as a primary school teacher, before moving into higher education. His research interests focus on ICT in education, particularly the use of interactive technologies in learning and teaching.

Nicola Bolton

Nicola Bolton is the Head of Department for Marketing and Strategy in the Cardiff School of Management. She maintains strong industry links, being a Director for British Gymnastics and the British Gymnastic Foundation and has been a member of the Sport Wales Board.

Alex McInch

Alex McInch is a Senior Lecturer and is also the Professional Doctorate Coordinator in the School of Sport and Health Sciences at Cardiff Metropolitan University. He is a social policy researcher who publishes regularly in the domains of education, sport and health.

References

- Bate, E. 2020. “Justifying Music in the National Curriculum: The Habit Concept and the Question of Social Justice and Academic Rigour.” British Journal of Music Education 37 (1): 3–15.

- Beauchamp, G. 1995. “National Curriculum Music (Wales): ‘The Third Language?’.” The Welsh Journal of Education 5 (1): 42–54.

- Deng, Z. 2021. “Constructing ‘Powerful’ Curriculum Theory.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 53 (2): 179–196.

- Dwyer, R. 2019. Music Teachers’ Values and Beliefs: Stories from Music Classrooms. London: Routledge.

- Education Reform Act. 1988. United Kingdom.

- Education Scotland. 2019. “What Is Curriculum for Excellence?” Accessed December 16, 2020. https://education.gov.scot/education-scotland/scottish-education-system/policy-for-scottish-education/policy-drivers/cfe-building-from-the-statement-appendix-incl-btc1-5/what-is-curriculum-for-excellence/.

- Gammon, V. 2006. “Cultural Politics of the English National Curriculum for Music, 1991–1992.” Journal of Educational Administration and History 31 (2): 130–147.

- Giudici, A. 2021. “Teacher Politics Bottom-Up: Theorising the Impact of Micro-Politics on Policy Generation.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (6): 801–821.

- Green, L. 2002. How Popular Musicians Learn: A Way Ahead for Music Education. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Green, L. 2008. Music, Informal Learning and the School: A New Classroom Pedagogy. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hizli Alkan, S., and M. Priestley. 2019. “Teacher Mediation of Curriculum Making: The Role of Reflexivity.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 51 (5): 737–754.

- Kneen, J., T. Breeze, S. Davies-Barnes, V. John, and E. Thayer. 2020. “Curriculum Integration: The Challenges for Primary and Secondary Schools in Developing a New Curriculum in the Expressive Arts.” Curriculum Journal 31 (2): 258–275.

- Kneen, J., T. Breeze, S. Davies-Barnes, V. John, and E. Thayer. 2021. “Pioneer Teachers: How Far Can Individual Teachers Achieve Agency Within Curriculum Development?” Journal of Educational Change. doi:10.1007/s10833-021-09441-3.

- Marope, M. 2013. Reconceptualizing and Repositioning Curriculum in the 21st Century. Geneva: IBE UNESCO.

- Marope, M., P. Griffin, and C. Gallagher. 2017. Future Competences and the Future of Curriculum. Geneva: IBE UNESCO.

- Maton, K. 2014. “Knowledge-Knower Structures: What's at Stake in the ‘Two Cultures’ Debate, Why School Music Is Unpopular, and What Unites Such Diverse Issues.” In Knowledge and Knowers: Towards a Realist Sociology of Education, 77–97. London: Routledge.

- McPhail, G. J. 2015. “Music on the Move: Methodological Applications of Bernstein’s Concepts in a Secondary School Music Context.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (8): 1147–1166.

- McPhail, G., and J. McNeill. 2019. “One Direction: A Future for Secondary School Music Education?” Music Education Research 21 (4): 359–370.

- Mikser, R., A. Kärner, and E. Krull. 2016. “Enhancing Teachers’ Curriculum Ownership via Teacher Engagement in State-Based Curriculum-Making: The Estonian Case.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 48 (6): 833–855.

- New Zealand Ministry of Education. 2015. The New Zealand Curriculum. https://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/content/download/1108/11989/file/NZ%20Curriculum%20Web.pdf.

- Nordin, A., and D. Sundberg. 2021. “Transnational Competence Frameworks and National Curriculum-Making: The Case of Sweden.” Comparative Education 57 (1): 19–34.

- OECD. 2018. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

- Pruitt, L., D. Ingram, and C. Weiss. 2014. “Found in Translation: Interdisciplinary Arts Integration in Project Aim.” Journal for Learning Through the Arts: A Research Journal on Arts Integration in Schools and Communities 10 (1): 1–23.

- Rainbow, B., and G. Cox. 2006. Music in Educational Thought and Practice. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Regelski, T. A. 2012. “Musicianism and the Ethics of School Music.” Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education 11 (1): 7–42.

- Richardson, V. 1996. “The Roles of Attitudes and Beliefs in Learning to Teach.” In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: A Project the Association of Teacher Educators, edited by J. P. Sikula, T. J. Buttery, and E. Guyton, 102–119. London: Prentice Hall International.

- Richardson, V. 2003. “Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs.” In Teacher Beliefs and Classroom Performance: The Impact of Teacher Education, edited by J. Raths and A. Mcaninch, 1–22. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

- Sinnema, C., N. M. Nieveen, and M.. Priestley. 2020. “Successful Futures, Successful Curriculum: What Can Wales Learn from International Curriculum Reforms?.” Curriculum Journal 31 (2): 181–201.

- Swanwick, K. 1979. A Basis for Music Education. Windsor: NFER-Nelson.

- Swanwick, K. 1988. Music, Mind and Education. London: Routledge.

- Swanwick, K. 1999. Teaching Music Musically. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Vulliamy, G. 1977. “Music as a Case Study in the ‘New Sociology of Education’.” In Whose Music?, edited by J. Shepherd, P. Virden, G. Vulliamy, and T. Wishart, 201–228. London: Latimer.

- Welsh Government. 2020a. Curriculum for Wales. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales.

- Welsh Government. 2020b. Introduction to Curriculum for Wales Guidance. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/introduction/.

- Welsh Government. 2020c. Area of Learning and Experience: Expressive Arts. Accessed May 31, 2020. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/expressive-arts.

- Welsh Government. 2020d. Curriculum for Wales: Overview. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://gov.wales/curriculum-wales-overview.

- Wiggins, R. 2001. “Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Music Educator Concerns.” Music Educators’ Journal 87 (5): 40–44.

- Wright, R. 2008a. “Kicking the Habitus: Power, Culture and Pedagogy in the Secondary School Music Curriculum.” Music Education Research 10 (3): 389–402.

- Wright, R. 2008b. “Power, Culture and Pedagogy in Music Education: Whose Curriculum Is It?” In Sociological Explorations. Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on the Sociology of Music, edited by Ba Roberts, 395–406. St. John's: Binder's Press.

- Wright, R. 2014. “The Fourth Sociology and Music Education: Towards a Sociology of Integration.” Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education 13 (1): 12–39.