ABSTRACT

This article explores the potential of gestural migrations as a novel approach to violin pedagogy, allowing us to trace enlightening parallelisms between the learning of musical performative gestures and the gestural dimension of cinema as a time-shaped/shaping artistic discipline. As a case study, I take the first movement of Claude Debussy's Violin Sonata L. 140, composed in 1917, following an empirically grounded quantitative analytical approach. I attempt to trace gestural correspondences with selected scenes from the contemporary French cinematic movement that fascinated the composer in the early years of the twentieth century.

Introduction

One of the essential aspects involved in instrumental teaching is the transmission and assimilation of new gestural patterns. Let us assume that a performer/teacher employs a limited number of patterns that can be partially systematized. While the introduction of new compositional or performative styles comprises the expansion of the student's gestural vocabulary, the student's individual musicianship enables in return the transformation of the transmitted models, broadening the ever-expanding index of instrumental gesturality. The involved communication process is not simple, usually combining the use of mimicry/imitation and other non-gestural musical or non-musical (figurative interpretations, metaphors, references to other artistic disciplines, etc.) explanations. This article argues that the notion of gestural migration might be a novel and powerful source of inspiration for students and teachers alike to trace enlightening parallelisms between the learning of performative gestures and the gestural dimension of cinema as a time-shaped/shaping artistic discipline. A brief discussion of the intellectual framework grounding my overall hypothesis leads to an empirical quantitative analysis of the gestures involved in the performance of the first movement of Claude Debussy's Violin Sonata L. 140, composed in 1917. This serves to trace a comparative gestural analysis with selected scenes from the coetaneous French films that fascinated the composer in the early twentieth century.

A tentative definition of gesture

American scholar Carrie Noland proposes the following understandings of gesture

[i] as movement intimately and exclusively related to the body and its expressiveness (phenomenology); [ii] as conventionalized movement belonging to a system of signification imposed by culture upon the body (semiotics, linguistics, and rhetoric); [iii] as movement situated within operating chains responsible for producing knowledge, culture, and even types of consciousness (anthropology, palaeontology, and Marxism); and [iv] as movement that is not exclusively related to the body but generated instead by an apparatus – including the body understood as apparatus – capable of being displaced in space (deconstruction and new media studies). (Noland and Ness Citation2008, xi)

Our research focuses on a vision of gestures ‘as a corporeal practice engaging the fleshly human being’, a vision connected to their consideration ‘as the least conventional of signs’ (Ibid., xi). Such unconventionality justifies the diversity of readings found in seminal scholarship, currently divided between two predominant paradigms: the consideration of gestures ‘as indexical of subjectivity and presence versus … [their consideration] as signifiers for meanings generated by the mechanics and conditions of signification itself’ (Ibid., xii). From a music-based performative perspective, the ability of gestures to emotionally move us points to their understanding as ‘modelled energy’, using Eugenio Barba's terminology, an energy that gives shape to affects even if it lacks ‘precise, codified, or translatable meanings’.Footnote1 Performative gesturing presents the body’s struggle with its own potential semiotisation. Moreover, if gestures ‘encode, express, and perpetuate the values of specific historical and cultural formations’ (Noland and Ness Citation2008, ix), they will consequently morph, acquire new meanings, and evolve through their displacement or dislocation and geopolitical, sociocultural, or cross-disciplinary migration. Gestures can thus be seen as traces of a past that resists the oppressive homogenisation of post-industrial societies.

The musicological consideration of gesture has gained prominence over the past few decades thanks to the fundamental contribution of scholars such as Anthony Gritten, Elaine King, Rolf Inge Godøy, Robert Hatten, and Marc Leman.Footnote2 Beyond their theoretical approaches, the domain of gestural analysis has also evolved rapidly under the influence of scholars as diverse as Alexander Refsum Jensenius or Frederic Bevilacqua, among others.Footnote3 As Gritten points out, ‘definitions of musical gestures vary across … communities, as do methodologies, both theoretical and practical, for understanding how musical gestures originate, what they mean and how they work’ (Gritten and King Citation2006, xx). This paper contributes to such an array of theoretical and analytical studies, focusing instead on an examination of the planned instrumental manipulative gestures required to play the violin. While this narrow focus is a necessary analytical apriorism that carries theoretical significance, it overlooks the complexity of the examined material. I nonetheless believe that the notion of gestural migration may be connected to central ideas found in the theoretical frameworks developed by the above-mentioned authors: Hatten's vision of gestures as implied meanings derived from cultural correlations, Arnie Cox's interest in the transmission of gestures through unconscious imitative participation, and Steve Larson's exploration of the notion of musical forces.Footnote4 While these ideas will be revisited at a later stage let us first examine Debussy's Sonata, its formal structure, and overall historical background, as a necessary foundation for the forthcoming examination of gesturality.

Debussy's violin Sonata: formal remarks

Debussy's Sonata for violin and piano was the third and last completed work of a set of six pieces involving different instrumental combinations that the composer envisioned and only partially realised in the final days of his life.Footnote5 The Sonata involves a return to traditional nomenclature and compositional forms. Debussy mixes a reflective attitude with a symbolic heightening of French patriotism, an exaltation that illustrates the composer's effort to position himself against the overpowering weight of the Germanic tradition.Footnote6 In a certain sense, the Sonata at once embodies and defies the two fundamental categories that articulate Edward Said's notion of late style: aesthetic distillation and artistic alienation (Said Citation2006).

While some scholars have criticised the work's lack of musical and formal inventiveness others, such as Barbara L. Kelly, have argued that Debussy ‘was writing the past to justify innovation’ (in Trezise Citation2003, 40). Kelly stresses how the music's austerity might be linked to the composer's engagement with the music of Phillipe Rameau and a broader interest in the French Baroque, incorporating several baroque gestures such as the ‘dotted figures, syncopation, pedals, contrapuntal textures, Baroque bowing techniques and uncharacteristically expansive melodies' (in Trezise Citation2003, 40).

Debussy explores a combination of structural elements taken from the type of cyclic sonata employed in his earlier Quatuor à Cordes Op. 10 (1892–93) as well as traits that resemble a ‘traditional’ normative sonata form (Wheeldon Citation2005). The result is a flexible formal framework that, while representing a severe deviation from nineteenth-century standards, emerges from and integrates the distinct syntactical conventions found in his previous music. The following consideration of the first section of the first movement, marked Allegro vivo, illustrates this.

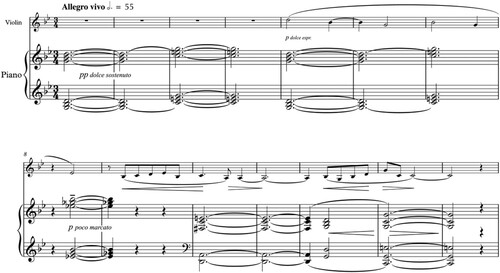

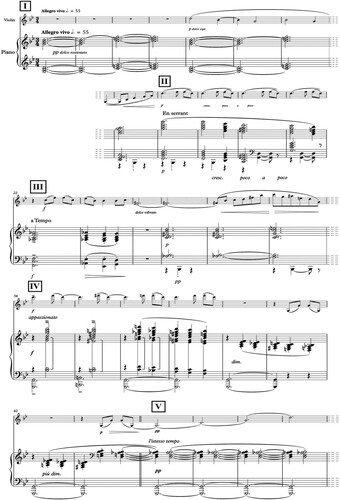

James A. Hepokoski argues that ‘Debussy's reliance on syntactical models in generating his own style is nowhere more evident than at the beginnings of his works’, which are often markedly formulaic (Hepokoski and Darcy Citation2011, 45). Hepokoski proposes a taxonomy that is clearly relevant to the opening of Debussy's Violin Sonata: a repeated sequence of a two-bar-long tonic G minor chord (i) and a variant of a subdominant chord (IV) that, through its raised third, implies a Dorian mode (see bars 1 to 7 in ). This is what Hepokoski defines as ‘modal/chordal opening’: repeated chords in equal time values that attempt to portray a ‘swaying, static circularity, a gentle rotation around a central axis' employing a ‘“mysterious” modal quality to suggest according to the designated context, primeval times, ecclesiastical austerity, quasi-mystical reverie, or uncommon experience in general’ (Hepokoski and Darcy Citation2011, 48).

In a second taxonomical group, the ‘monophonic opening’, a characteristic opening silence may be substituted by a pedal before an unaccompanied melodic line ‘typically beginning with a relatively prolonged initial pitch, piano or pianissimo … glides gracefully into more active rhythmic motion in a manner that is not emphatically metrical’. Here, the violin's melodic line, which is not emphatically metrical (a hemiola), melodically undular, and starts on a weakened tonic, interrupts the static harmonic pedal-like sequence (see bars 4 to 14 in ). The material then ‘gracefully glides' into more active rhythmical material from bar 9.

Hepokoski proposes a third type of formulaic opening, the ‘introductory sequences/expansions’, combinable with those discussed above. The American scholar differentiates several subsequent phases: i. a phrase of the monophonic or modal/chordal type, ii. a fermata or grand pause, iii. a varied repetition of the opening phrase, iv. another fermata, and v. contrasting material (Hepokoski and Darcy Citation2011, 48–50). The whole opening of Debussy's sonata, up to what would normatively correspond to the onset of the developmental rotation, fits Hepokoski's suggested phase structure (see ).

This brief formal analysis grounds our ensuing consideration of a selection of editing techniques found in early cinema that relate to Debussy's music and enable a comparative examination of their underpinning gestural dimensions. I take Anthony Newcomb's approach to the musicological adaption of narratological discourses (Newcomb Citation1987) as a starting point, expanding his study of the connections between literary narratives and formal structures in the music of composers such as Robert Schumann to introduce further trans-disciplinary mappings. While Newcomb's basic framework has already been explored in the research of scholars such as Rebeca Leydon, this article transcends it through a consideration of the cross-domain hybridisation of gestural topoi.Footnote7

Debussy and cinema

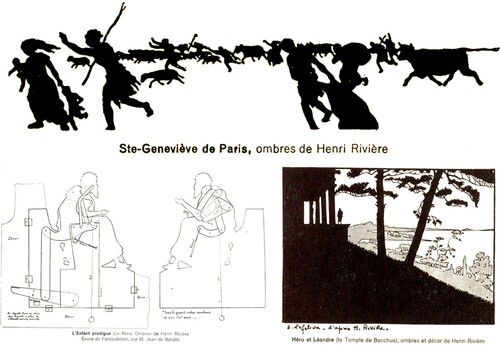

Many would argue that the attempt to trace a connection between the gesturing involved in the performance of Debussy's violin sonata and that found in the French cinema from the early twentieth century is a spurious unnecessary venture. Two key arguments counter this critique: first, its pedagogical significance—the one that this article attempts to demonstrate—and second, Debussy's fascination with cinema and its creative possibilities as an exemplification of his own musical and compositional principles. British scholar Richard Langham Smith points out that ‘the composer envisioned cinema as an inspiration from a technical and aesthetic point of view’ (Smith Citation1973, 64). In a 1913 article, Debussy stressed that there might still be ‘one means of renewing the taste for symphonic music among our contemporaries: to apply to pure music the techniques of cinematography. It's the film … which is going to allow us to escape from this disquieting labyrinth’ (Debussy in Smith Citation1973, 64). Reflecting on his craft, the composer admitted that ‘one might add here comments of cinema which passed through the composer's mind just when he was composing his works’ (Debussy in Smith Citation1973, 64). Withal, previous research has linked the French composer to Henri Rivière's ombres chinoises and his collaborations with cartoonist Adolphe Willette, a fascinating forerunner of the art of cinema, at Montmartre's famous cabaret Chat Noir (see ). Smith argues that ‘with his taste for the cinema established by Rivière's art, Debussy's concept of the ‘image’ may well owe a little to the techniques of cinema’ (Smith Citation1973, 68).

Figure 1. Henri Riviere, shadows and puppet mechanisms.Footnote8

Rebecca Leydon has explored the compositional approaches characteristic of the composer's final period and the filmic methods of ‘enchainment’ or ‘modes of continuation’ recurrent in these works. She compares ‘their enigmatic transitions, their disjunctive reiterations, and duplications’ to various editing devices extensively employed in the early twentieth century's silent cinema (Leydon Citation2001, 217). Leydon identifies paradigmatic modes of continuation that emerge to ‘modify the classical narrative syntax of traditional story-telling media’, representing a ‘radical departure from the temporal and spatial orientations to which traditional theatre-goers were accustomed (Leydon Citation2001, 218). According to Leydon, we may trace a connection between five early editing techniques and Debussy's oeuvre: i. the dissolve, ii. the direct cut, iii. the shot/reverse-shot technique, iv. cross-cutting, and v. the dream balloon technique.Footnote9 These parallelisms, explored below, point to a first potential connection between the musical and film realms that has clear gestural implications.

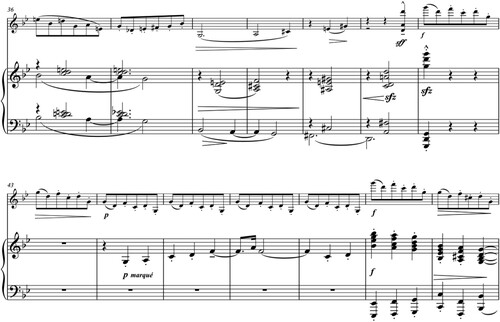

An enchainment resembling the dissolve technique, linking two shots through an apparently smooth transition that conceals the underlying cut (e.g. Georges Méliès’ Citation1899 Cinderella or his Citation1904 Le Roi du maquillage), can be found in the material leading up to bar 64 in , where the composer integrates the piano's left-hand sustained octave g pedal into the new material.Footnote10 The pedal works as an underpinning spring for the violin part on the pickup to bar 64 before the piano restates it to support the violin's new thematic development. While this was not an unprecedented approach to the connective transformation of musical material, the technique arguably acquired ‘new mimetic significance once the cinema … [had become] available as an interpretant’ (Leydon Citation2001, 224).

Contra the dissolve technique, the direct cut openly exposes transitions as abrupt shifts (e.g. J. H. Williamson’s Citation1901 films Stop Thief! and Fire! Citation1901 or Ferdinand Zecca’s Citation1905 Scenes of Convict Life). Debussy's music exemplifies this editing approach in the mode of continuation leading to rehearsal number 1 (see ). Leydon points out that

in his late works, Debussy often eschewed smoothness of formal continuity. Transition through graduated transformation is a characteristic associated more with his earlier … style, and his latter reliance on sudden musical contrasts can be understood as a rejection of those Impressionistic ideals (Leydon Citation2001, 226).

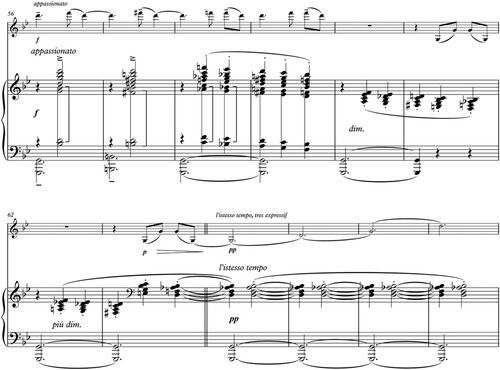

In the shot/reverse shot technique two cameras placed 180 degrees apart capture an exchange between two opposing actors (Bordwell Citation2008, 57–58 – e.g. D. W. Griffith’s Citation1911 The Primal Call). Compositionally, the technique implies the simultaneous depiction of two contrasting characters, that is, the concurrent appearance of two different musical ideas. Debussy introduces this in the enchainment leading to the recapitulation of the opening material. He maintains the characteristic accompaniment introduced in the previous section (the opening bar of ) as a counterpoint to the Sonata's opening motive (marked in green in ).

Leydon's research explores as well the use of the cross-cutting technique, the repetitive rotation of various shots to suggest the diegetic simultaneity of diverse film scenes (e.g. Griffith’s Citation1915 Birth of a Nation, Edwin Stanton Porter’s Citation1903 The Great Train Robbery, Luis Gasnier’s Citation1908 The Runaway Horse – ). Debussy parallels this in his reenaction of the eight-bar long violin motif found in the second movement, bars 72 to 78, and within a completely different texture and motivic development process in the third movement, bars 101 to 116 (see ). The composer integrates the theme in a rapid arpeggiated piano texture interrupted by the violin’s entrance with contrasting material accompanied by the Sonata’s opening hemiola before both instruments repeat the reinstated theme one final time.

Figure 2. Stills from The Runaway Horse, Louis Gasner, Citation1908.

A further film editing technique that originated from comic strip conventions and bears parallelisms to Debussy's Sonata is the aforementioned ‘dream balloon’. Through a process of double-exposure, this technique superimposes two different narrative levels, usually real and fictional, taking place within a single filmic space. Leydon connects this technique to Debussy's combination of what she terms as ‘contrasting musical environments’ in his late polytonal writing (Leydon Citation2001, 231). In early French cinema, the ‘dream balloon’ was extensively used to portray the simultaneity of a character's internal and external levels of narrative action, particularly to represent their dreams (e.g. Zecca's Citation1901 Histoire d’un crime and Melies’ Voyage à travers l’impossible – and ).

Figure 4. Stills from Voyage à travers l’impossible, Georges Méliès, Citation1904.

Having briefly analysed the opening formulaic nature of the first movement of Debussy's Sonata and explored its connection to cinema from both an aesthetic and formal perspective, the question remains: how can we link these concepts to a gestural-performative consideration of his music? Further, how can we trace patterns of gestural migration between specific representations of corporeality found in early French cinema and the performance of Debussy's violin sonata?

A new gestural taxonomy

I would like to propose a new gestural taxonomy, integrating and transcending the gestural implications underlying Hepokoski and Leydon's perspectives, to undertake the ensuing consideration of the first movement of Debussy's Sonata. My analysis focuses on the performer's right-arm, that is, the bow and its associated movements. This novel categorisation, while undeniably partial in scope and complexity, serves to accommodate the three main gestural patterns involved in the performance of this Allegro Vivo, subsuming the gestural narrative and the bodily representation associated with the novel paradigms established by early cinema: static expansive gestures, repetitive gestures, and stagnant gestures underpinned by a propulsive energy.Footnote11

Static expansive gestures

This apparently contradictory notion refers to directionless or slow and expansive gestures lacking a sense of forwardness. The notion thus relates to an exploration of gesture at a standstill, a vision of movement as a balancing act. Such gestural patterns abound in the movement's opening section corresponding to the first phase of Hepokoski's ‘introductory sequences/expansions’ taxonomy (see ). The espresiff section, starting at bar 64 and leading to the modulation that initiates the meno mosso at bar 84, is a further example (see ). Such gesturality emerges from the nature of the musical material: Debussy employs a combination of slow rhythmical writing and harmonies purposely lacking a sense of tonal/modal directionality.

Repetitive gestures

Repetitive gestures are also frequent in Debussy's Sonata, a characteristic example being the third phase of Hepokoski’s model: a one bar-long sequence repeated in either its original or transposed version a total of seventeen times (). This distinctive instance shows how is repetitiveness embedded, as in the case of the static expansive gestures, in the employed musical material. Here, Debussy's music seems to get stuck, generating a sense latency that differs from that considered earlier through recurrent but non-expansive gestures. The inability to move arises from the movement's circularity, from its continuous return to the point of departure, not from a lack of directionality.

Forward-moving stagnant gestures

We can find examples of stagnant gestures underpinned by a forward-moving dynamism in the second section of the analytical model explored earlier (). We have seen how both static and repetitive gestures generate a sense of quietude that implies a circular or expansive inability to move. However, Debussy occasionally enhances those gestures to generate a sense of forwardness through a number of elements related to tempi (i.e. the en serrant indication) and dynamics (i.e. the employment of directional crescendi). In contrast to the static expansive gestures considered above, these forward-moving stagnant gestures eventually resolve the accumulation of tension emerging from such a condensation of unrealised directional energy.

The following section will explore the relationship between the simplified gestural typology introduced thus far and specific representations of bodily movement in early films but let us first briefly explore the analytical methodology.

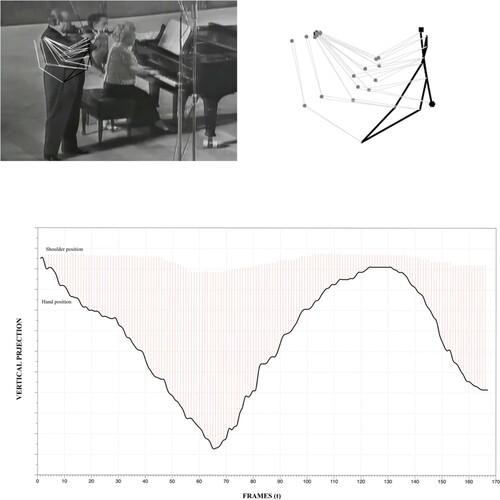

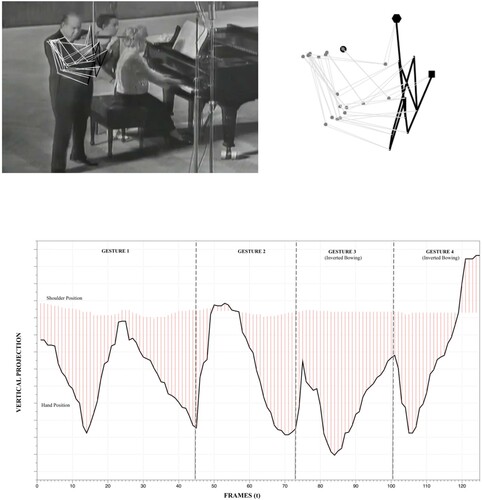

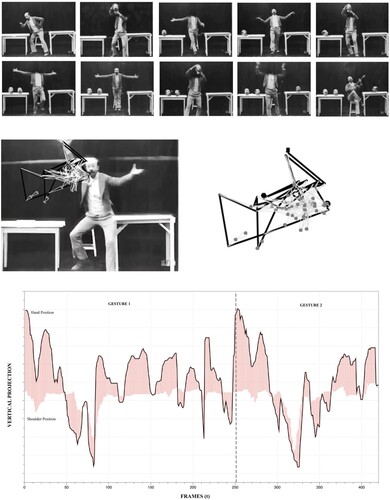

Methodology

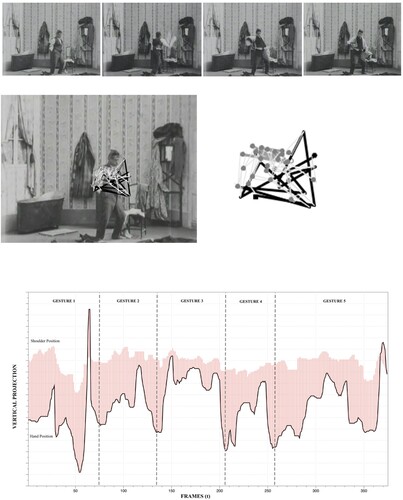

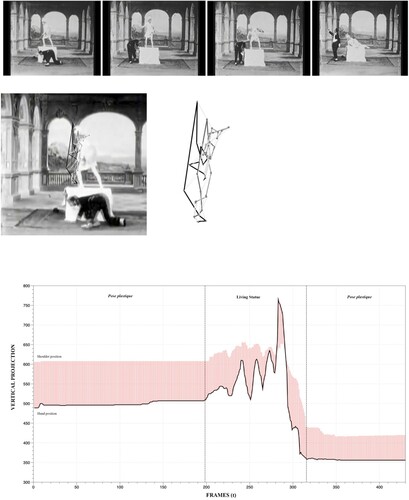

The analytical diagrams introduced below render three-dimensional gestures into a simple bi-dimensional format, allowing us to understand the linked arguments without resorting to the discussed videos. My approach acknowledges the different motion capture and gestural mapping techniques that have emerged during the past few years. While alternative analytical frameworks (the employment of motion image analysis, motion average image analysis, and motiongrams) were considered (Jensenius Citation2013, 55–57), I have chosen to introduce a novel process drawing from the so-called ‘motion history keyframe display’ that employs as raw material the original (2D) videos of David Oistrakh's recording of Debussy and the early movies considered below. I employed Processing, ‘a flexible software sketchbook’, to create a video canvas that allowed me to trace the movement of a number of key points manually positioned on the performers’ and actors’ bodies.Footnote12 The analysis was carried out on a frame-by-frame basis, extracting the stills from the video, and then rendered as a set of lines representing the movement of those points in space over time corresponding to one or various gestural units. This simple technique resonates with the work of Edward Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey and chrono- and stroboscopic photography, as well as with Gunnar Johansson's pioneering work in the 1970s.Footnote13 The images included here were extracted from the total number of frames, the frame-extraction-rate being indicated at all times, and the resultant x/y axis data was then exported to DataGraph. Each gestural analysis presented in this article includes the following elements: i. a first version of the gestural tracking superimposed on the first frame of the video selection; ii. a second cleaner version without the video background in which the original and final hand positions are respectively indicated by a square and a hexagon shape; and iii. a third version prepared in DataGraph showing the projection of the movement over time and the distance between hand and shoulder positions at all times, respecting the proportions between the elements extracted from the analytical canvas. Beyond the descriptive analyses of the videos introduced in the following sections and their employment as the basis of my meta-analytical narratives, the third version of the data discussed above will play a crucial role in the remainder of the article as an objectification of my arguments. below correspond to the previously discussed examples 1, 12, 11a, and 11b. The reader should examine them in detail as they will gain renewed transcendence in the final part of the article when compared to the film-based data discussed later.

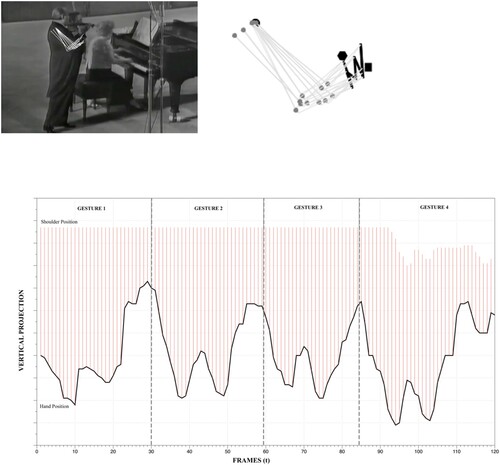

Figure 5. Stills and gestural analysis (166 frames at a 1/16 frame extraction rate) of David Oistrakh performing an expansive gesture in Debussy, Violin Sonata, mm. 5–8 ().

Figure 6. Stills and gestural analysis (125 frames at a 1/12 frame extraction rate) of David Oistrakh performing a forward-moving stagnant gesture in Debussy, Violin Sonata, mm 18–21 (Example 12).

Figure 7. Stills and gestural analysis (114 frames at a 1/13 frame extraction rate) of David Oistrakh performing a repetitive gesture in Debussy, Violin Sonata, mm 33–36 (Example 11a).

Figure 8. Stills and gestural analysis (318 frames at a 1/16 frame extraction rate) of David Oistrakh performing a repetitive gesture in Debussy, Violin Sonata, mm. 42–53 (Example 11b).

Early French cinema

My current analytical perspective focuses on early French films that showcase the editing techniques explored earlier, which might have been known to Debussy.Footnote14 Given the space limitation, I have selected a few examples from the pioneering work of Georges Méliès and Alice-Guy. However, my preliminary research involved the examination of key films from the directors that shaped the development of the art film scene and the emergence of different cinematic genres in France up to the composition of Debussy's sonata in 1917: Émile Cohl and animation, Georges Méliès’ trick films and the early development of science fiction, Max Linder and the emergence of comedy, Louis Feuillade and crime cinema, and Ferdinand Zecca and the drames sentimentaux, among others.

Static expansive gestures

The exploration of static and expansive gestures in early cinema adopts two main forms. First, what we could term as restricted movements, a type of partial (im)mobility linked to a Frankensteinian de- and re-attachment of body parts and to the expansive gestural quietude found in scenes introducing inebriated or intoxicated characters. Second, complete immobility, which is a much stranger feature of a new medium—the moving image—that was logically based on the time-based exploration of the gestural. Completely static gestures usually entailed a representation of the dreamlike, the magic, the hypnotic, and death.

Many of Méliès’ early films explored the Frankensteinian framework. In An Extraordinary Dislocation from Citation1901, the French director depicts the segmentation of the body into fragments that follow their own gestural patterns contra a static body/trunk that becomes a halted observer of the impossibility of its own dismemberment (see ). The Finnish film scholar Pasi Väliaho connects this approach to the very nature of the new medium and its ability to portray movements that may lack teleological continuity:

Méliès's films stimulate continuous transformations and thus portray the automatic character of the new medium that is capable of instigating movements and events without causes or origins and producing action that lacks agency. What one sees in Méliès … is how forms and figures melt into vectors of movement that automatically generate and reconstruct themselves, confusing and perpetually reworking in this way (Väliaho Citation2010, 27).

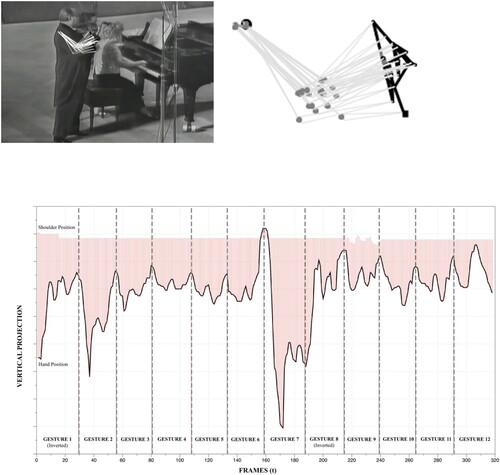

Figure 10. Stills and gestural analysis (157 frames at a 1/8 frame extraction rate) of Wonderful Absinthe, Alice Guy, Citation1899.

Repetitive gestures

During the final decade of the nineteenth century, existing technological constraints had an impact on the nature of early film's narrative paradigms, which were logically linked to the necessary spatiotemporal continuity of the single-shot approach. A few years later, such a linear teleology had already integrated different forms of recursion. As a matter of fact, the transformative repetition of gestures became a characteristic compulsion of newly emerging cinematic narratives. Primitive examples can be found in the work of Georges Méliès, in trick films such as Un homme de têtes from 1898 (see ), the Citation1901 feature The Man with the Rubber Head, and the Citation1903 The Melomaniac (see ).

Figure 11. Stills and gestural analysis (422 frames at a 1/16 frame extraction rate) of Un homme de têtes, Georges Méliès, Citation1899.

We may link this obsessive exploration of gestural recursion to the late nineteenth century's scientific perception of the body as a technological arrangement.Footnote15 Previous scholars have traced a connection between that vision and Méliès’ unique framing of bodily rhythms through the new cinematographic medium. Väliaho, for example, points out how his films ‘configure the zone of indetermination as a process of bodily decomposition that rather directly takes up the same problematic of convulsive and “formless” movements as the hysterical body’ (Väliaho Citation2010, 28–29). Such perspective accounts for Méliès’ interest in bodily detachment and duplication ).

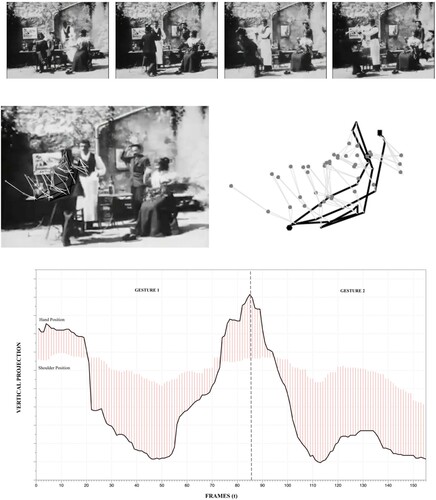

Figure 13. Stills from The Fisherman at the Stream, Alice Guy, Citation1897.

Adopting a completely different approach to the moving image as an extension of scientific apparatuses that we find in Méliès’ trick films, Guy produced a number of early films that were markedly costumbrist. The documentary portrayal of aspects of everyday life was nonetheless mixed with elements that added interest to the visual narrative. Such is the case in her 1897 film entitled The Fisherman at the Stream, () which portrays a group of kids repeatedly pushing a fisherman into a river; or that in her 1903 film How Monsieur Takes his Bath, which shows the main characters’ inability to undress himself in preparation for a bath as new layers of clothing magically reappear each time he attempts to remove them. By extracting a 374-frame gesture sequence and subjecting it to the same analytical procedure employed earlier, we can see the clear connections between and Oistrakh’s gesture in .

Figure 14. Stills and gestural analysis (374 frames at a 1/30 frame extraction rate) of How Monsieur takes his bath, Alice Guy, Citation1903.

Forward-moving stagnant gestures

I have noted how the idea of stagnant forwardness implied a different understanding of the static, one that conveyed an accumulation of energy that was eventually resolved. I pointed out how Debussy characteristically introduced a number of musical elements to modify repetition, thereby generating an unresolved inflation of dynamism entailing a teleological drive. We find gestural examples in early French cinema that are qualitatively different to those explored thus far but still connected to this gestural dimension of Debussy's music.

A clear example relates to early cinema's adaptation of the tableaux vivants or living paintings, a form of performance that gained increasing relevance throughout the nineteenth century. Many of the key topoi of the tableaux vivants (living statues, living pictures, etc.) found their way into a new medium ‘whose very essence revolved around bringing motion to static bodies’ (Adriaensens in Dahlquist et al. Citation2018, 25). The first instances, dating from the late 1890s, can be found in various films made by the American Mutoscope and Biograph companies. Early cinema's fascination with this format and its linked ‘effect of stasis goes hand in hand with a penchant for its opposite—the picture coming to life’, an oscillation that was ‘often used as metaphor of the tension between life and death’ (Adriaensens in Dahlquist, 2018, 25). While Méliès has at least seventeen films that depict this trope, I have opted to focus on one of Guy's films for the purpose of this analysis. It is in a retrospective consideration of the relationship between the living statue and its preceding motionless pose plastique that a sense of forwardness emerges from its apparent stagnancy. Guy's 1905 The Statue portrays a comical exchange between a statue that moves only when it cannot be seen and two clowns that get struck by the statue whenever they lose sight of it. Examining , one can see clear connections with Oistrakh's data as presented in . While Oistrakh's gesture exponentially evolves from a smaller to a more expanded contour (hence its forwardness), that of the living-statue is framed by two completely static linear outlines representing both phases of its apparently inanimate nature.

Figure 15. Stills and gestural analysis (434 frames at a 1/11 frame extraction rate) of The Statue, Alice Guy, Citation1905.

Both the gestural typology presented earlier, and the analyses introduced thus far aim to trace inter-medial gestural migrations between two different time-based realms. The prospect of such translation is valuable enough a reason—given its pedagogical implications—to explore its objective plausibility. My analyses encompass a broader consideration of their overall connections, following the proposed simplified typology, and the evident parallelisms between their resultant graphic representations, pinpointed in their occurrences throughout the text. Emerging from that analytical combination, this case study opens up a novel approach to the expansion of a musician's gestural thesaurus, one that delves into the exploration of transdisciplinary linkages as music teaching resources, that is, musical gestures taught from a contextualised apparent otherness (i.e. cinema). But how can we translate this into a real-life teaching situation? How can we move beyond the theoretical framing introduced thus far and extract a practice-led pedagogical reading?

Pedagogical implications

Let us stress once again the openly discussed biases and limitations advanced in the historical, analytical, and methodological sections: i. while the cross-media comparisons that underpin the proposed gestural migrations could be expanded to any other repertoire or time-based artistic media, our focus on the violin's right-hand technique in Debussy's music is but a case study that responds to the direct morphological connections between this Sonata and the emergence and evolution of early French cinema's editing techniques, the clear connection between right-hand movements and sound-production on the violin, and their adequacy for the ‘objective’ analytical method; ii. the proposed gestural migrations trace a bridge between the form of representability that cinematic gestures enact and the domain-specific ‘non-representational representability’ of violin right-hand movements as sound-producing gestures, iii. these migrations point to a hermeneutics of Debussyian performance and body movement in Early French Cinema that remains open to further theoretical discussion and is only presented here as a mode of thought, as thought-in-action, beyond the specific semantics of cross-media translations.

The proposed model emphasises the importance of integrating multi-modal stimuli into violin teaching routines in a classroom setting (introducing a different approach to Barton and Riddle Citation2022; Welch Citation2007, Volpe & Camurri in Solis and Ng Citation2011, and most importantly Volpe et al. Citation2017, among others) via a speculative pedagogical pragmatism that explores techniques of relation (gestural migration) and enacts our thinking through a critical attention to the body. The following diagram shows an early draft of a technological setup under development at my tertiary teaching institution (see ).

The student performs in front of a retro-projected translucent screen that plays the selected videos at a life-size scale while the teacher analyses their superimposition from the other side. The model transcends the shared viewing and discussion of the suggested film fragments, when working on the related sections from Debussy's Sonata, to introduce a non-discursive mechanism based on a partial real-time mimicking of gestural patterns – with and without the instrument – aimed at enhancing technic-stylistic learning.

This model expands previous work on multimodal interactive systems for violin learning (e.g. Volpe et al. Citation2017) integrating technology into string teaching routines (e.g. Axford Citation2015; Li Citation2020, etc.). In addition, it enables both teachers and students to explore intricately abstract aspects of difficult-to-grasp right-hand technique through the incorporation of auditory and visual feedback (e.g. Malandrino, Pirozzi, and Zaccagnino Citation2019; Pardue and McPherson Citation2019, etc.). Following Acquilino & Scavone, the model teaches ‘a specific technical concept in an exercise-like context’ (Acquilino and Scavone Citation2022, 8) to develop—through technologically-enhanced learning—fundamental instrument-specific technical skills that transcend the limiting tech-related focus on pitch and rhythm.

As stated above, the model also represents a key contribution to the exploration of non-discursive mechanisms and embodied learning in music pedagogy, elaborating on recent work on music and emotion research (e.g. Juslin and Timmers Citation2010), education philosophy (e.g. Elliott and Silverman Citation2012), music and gesture research (e.g. Toiviainen and Keller Citation2010), and performance and musical communication (e.g. Kawase Citation2014). Thus, the proposed approach involves the active engagement of the body in cognitive processes (Kosmas, Ioannou, and Zaphiris Citation2019), highlighting the pre-reflective, pre-discursive, and pre-social implicit aspects of human cognition, action, and interaction.

This article sits at the interdisciplinary intersection leveraging speculative theory and a critical engagement with pedagogy. Following our brief engagement with the latter, let us now return to the initial conceptual framework to undertake a critical reassessment of the overall analytical approach.

Conclusion

If we accept a vision of bodily movement as the primary factor in the ontogenesis of subjective and intersubjective worlds (Maxine Sheets-Johnstone Citation1999, 136) and the fact that gestures migrate through time and space, undergoing appropriations and transformations shaped by different sociohistorical imperatives, we must also acknowledge the transformative pedagogical potential of the overall argument raised thus far. The pedagogical implications of the present text transcend its inevitable limitations, partly derived from the nature of the analytical framework and the need to objectively codify some of the presented data (e.g. the simplification of a complex somatic element into a purely visual one and the ability of gestures to overflow their potential reading as signs).

First, the connections between Debussy's music and cinema go beyond the purely formal dimension explored in the opening section to unearth a shared web of gestural registers. In doing so, they showcase the ability of gestures to ‘enact the trace of other bodies, rituals, [and] networks of exchange’, demonstrating how ‘gestures solicit gestures’ (Stern in Noland, 2008, 200). From that perspective, they enable the exploration of instrumental gestures beyond and without the instrument—a vision of artistic learning and practice as unavoidably cross-disciplinary—while raising the question of the often-overlooked significance that kinaesthetic learning should have in violin and instrumental pedagogy.

Second, this article has set up a simple analytical framework that aims to show the potential of gestural cross-disciplinary linkages as a pedagogical tool in violin learning. In doing so, the proposed pre-experimental model, analysing the impact that such a migration-based explanation of gestures might have on a student's performative development, transcends the theoretical focus. While such a practical approach has been part of my teaching routines over the past few years, it is left here as an open path for future research.

Third, while my argument emerges from non-musicological discussions, it is nonetheless linked to current research in the field. Gestural migration is clearly connected to the patterns of exertion that we associate with mimetic participation and the vision of music as a form of an embodied sound-based process of communication. As Arnie Cox points out, one of the most interesting analytical approaches linked to this vision is the exploration of mimetic motor actions between instrumentalists. Related research has shown ‘a degree of isomorphic physical responses across modalities’ (Cox in Gritten and King Citation2006, 49). This implies that amodal mimetic response might work as a basis for cross-modal imitation, that is, ‘that a gesture has a meaning which is at once in accord with its mode of production and transcendent of its mode of production’ (Cox in Gritten and King Citation2006, 51) We may also trace a connection with Steve Larson's notion of ‘musical forces’, that is, the assumption that ‘musical motion is shaped by forces analogous to those that shape physical motion’ (Larson in Gritten and King Citation2006, 61).Footnote16 By arguing that the complexities and underlying principles of physical and musical forces are similar, Larson unconsciously opens up—from an analytical perspective in which the score may be seen as a gestural script that needs to be de-codified—the possibility of cross-disciplinary migrations. Hatten has also explored the notions of intersubjective exchange and intermodal mapping and syntheses to examine the relation between gestures and other musical elements such as tropes, topics, thematic content, tonal structure, etc. His argument transcends the scope of his analytical framework when he claims that ‘the immediacy of musical gestures provides direct biological as well as cultural access from the outset’, generating a ‘redundancy of mutually supporting cultural and stylistic meaning’ (Hatten in Gritten and King Citation2006, 19). This contextualised and culturally mediated understanding of gestures brings us back to their migratory nature and to the implications explored in this paper.

While this article is but a small addition to the consideration of gestural migrations in musicological discourses, it does nonetheless introduce a new analytical lens that traces gestural connections between different disciplines, expanding and morphing the rigid paradigms of traditional instrumental teaching. Following Aby Warburg's early fragmentary example and the notion of pathos formulai, the time might have come to start tracing a Mneymosene of instrumental gesturality (Warburg Citation2020).

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Alexis Mailles in the conception and codification of the Processing tool used in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roberto Alonso Trillo

Roberto Alonso’s (b. 1983) professional career embraces three interconnected levels of activity: performance, pedagogy, and research. His areas of interest include string-related subjects, an interest in the work and ideas of Theodor W. Adorno, the philosophy of music, contemporary music, a broad interest in the connections between post-structuralism and music, music and AI, and an increasing focus on interdisciplinary music studies.

Notes

1 For a more detailed discussion see Barba (Citation1994, 49–51).

2 See Hatten (Citation2001), Gritten and King (Citation2006), Godøy and Leman (Citation2009), Gritten and King (Citation2011), and Leman (Citation2016).

3 See Jensenius (Citation2009) for an early introduction to his research interests and Caramiaux, Bevilacqua, and Schnell (Citation2010) for an example of his approach.

4 These can be found in Gritten and King (Citation2006).

5 For a broader discussion of this set of sonatas, see Kecskeméti (Citation1962).

6 For an example of Debussy's reflections on this matter, see Debussy and Lesure (Citation1998, 273).

7 See Barthes S/Z (Citation1975) and Gombrich (Citation2014).

8 Jeanne (Citation1937, pp. 68, 64, and 73).

9 These techniques belong what are usually defined in cinema studies as ‘Institutional Modes of Representation’ or IMR. See Burch and Brewster (Citation1990).

10 It is worth pointing out that the dissolve was not used to signal a time-lapse until the 1920s, but merely served as a transition between two adjacent spaces- see Elsasser and Barker (Citation1990, 32). This technique can also be linked to Richard Parks’ notion of the ‘kinesthetic shift’ (Parks Citation1989).

11 For a summary of the different approaches to the classification of gestures found in different disciplines throughout history, see Kendon Citation2004, 84–107.

12 Please see https://processing.org and https://p5js.org for further reference.

13 See Marey (Citation1895, 54–67) and Johansson (Citation1973).

14 For an overview of early French cinema refer to Abel (Citation2005) and Gaudreault, Dulac, and Hidalgo (Citation2012). Although we will not explore them here, the early experiments to capture photographic motion (i.e. the work of Étienne -Jules Marey and Albert Londe) or early experimental approaches to the creation of motion pictures, such as Emil Reynaud's Théâtre Optique and Praxinoscope, are of great interest as well.

15 Think of Marey’s definition of the living being as an ‘animal machine’. See Marey Citation1883, 227.

16 For further discussion see Larson (Citation2002) and Larson (Citation2004).

References

- Abel, R. 2005. Encyclopedia of Early Cinema. London: Routledge.

- Acquilino, A., and G. P. Scavone. 2022. “Current State and Future Directions of Technologies for Music Instrument Pedagogy.” Frontiers in Psychology 13: 835609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835609.

- Axford, E. C. 2015. Music Apps for Musicians and Music Teachers. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Barba, E. 1994. The Paper Canoe: A Guide to Theatre Anthropology. London: Routledge.

- Barthes, R. 1975. S/Z. New York: Hill&Wang.

- Barton, G., and S. Riddle. 2022. “Culturally Responsive and Meaningful Music Education: Multimodality, Meaning-Making, and Communication in Diverse Learning Contexts.” Research Studies in Music Education 44 (2): 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X211009323.

- Bordwell, D. 2008. Poetics of Cinema. London: Routledge.

- Burch, N., and B. Brewster. 1990. Life to Those Shadows. University of California Press.

- Caramiaux, B., F. Bevilacqua, and N. Schnell. 2010. “Towards a Gesture-Sound Cross-Modal Analysis.” In LGesture in Embodied Communication and Human-Computer Interaction. GW 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5934, edited by S. Kopp and I. Wachsmuth. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12553-9_14.

- Dahlquist, M., D. Galili, J. Olsson, and V. Robert. 2018. Corporeality in Early Cinema: Viscera Skin and Physical Form. Indiana University Press.

- Debussy, C., and F. Lesure. 1998. Debussy on Music. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Elliott, D. J., and M. Silverman. 2012. “Rethinking Philosophy, Re-viewing Musical-Emotional Experiences.” In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy in Music Education, edited by W. D. Bowman, and A. L. Frega, 37–62. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elsaesser, T., and A. Barker, eds. 1990. Early Cinema: Space Frame Narrative. London: British Film Institute.

- Gasnier, Luis, dir. 1908. The Runaway Horse. https://youtu.be/vdWVM23AB-Y.

- Gaudreault, A., N. Dulac, and S. Hidalgo. 2012. A Companion to Early Cinema. Boston: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Godøy, R. I., and M. Leman. 2009. Musical Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning. London: Routledge.

- Gombrich, E. H. J. 2014. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. London: Phaidon.

- Griffith, David W., dir. 1911. The Primal Call. https://youtu.be/Sb8GFfwOd8Q.

- Griffith, David W., dir. 1915. Birth of a Nation. https://youtu.be/nGQaAddwjxg.

- Gritten, A., and E. King. 2006. Music and Gesture. London: Ashgate.

- Gritten, A., and E. King. 2011. New Perspectives on Music and Gesture. London: Ashgate.

- Guy-Blaché, Alice, dir. 1897. The Fisherman and the Stream. https://youtu.be/JSzHNlhDJ_k.

- Guy-Blaché, Alice, dir. 1899. Wonderful Absinthe. https://youtu.be/qYtJWb76fNU.

- Guy-Blaché, Alice, dir. 1903. How Monsieur Takes his Bath. https://youtu.be/skUEP-iI7YE.

- Guy-Blaché, Alice, dir. 1905. The Statue. https://youtu.be/0D4Rr6KqzR0.

- Hatten, R. 2001. Online lectures on music and gesture. Cyber Institute of Semiotics, 2001. http://chass.utoronto.ca/epc/srb/cyber/hatout.html.

- Hepokoski, J., and W. Darcy. 2011. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth Century Sonata. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jeanne, P. 1937. Les théâtres d’ombres à Montmartre de 1887 a 1923. Paris: Les Presses Modernes.

- Jensenius, A. R. 2009. Musikk og bevegelse [Music and Movement]. Oslo: UNIPUB Editions.

- Jensenius, A. R. 2013. “Sonifying the Shape of Human Body Motion Using Motiongrams.” Empirical Musicology Review 8 (2): 73–83.

- Johansson, G. 1973. “Visual Perception of Biological Motion and a Model for Its Analysis.” Perception & Psychophysics 14 (2): 201–211. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03212378.

- Juslin, P. N., and R. Timmers. 2010. “Expression and Communication of Emotion in Music Performance.” In Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, Research, Applications, edited by P. N. Juslin, and J. A. Sloboda, 453–489. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kawase, S. 2014. “Gazing Behavior and Coordination During Piano duo Performance.” Attention, Perception & Psychophysics 76 (2): 527–540. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-013-0568-0.

- Kecskeméti, I. 1962. “Claude Debussy, ‘musicien Français’, his Last Sonatas.” Revue Belge De Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift Voor Muziekwetenschap 16 (1/4): 117–149. 3686076.

- Kendon, A. 2004. Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kosmas, P., A. Ioannou, and P. Zaphiris. 2019. “Implementing Embodied Learning in the Classroom: Effects on Children’s Memory and Language Skills.” Educational Media International 56 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2018.1547948.

- Larson, S. 2002. “Musical Forces, Melodic Expectation, and Jazz Melody.” Music Perception 19(3), 351–385. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2002.19.3.351

- Larson, S. 2004. “Musical Forces and Melodic Expectations: Comparing Computer Models with Human Subjects.” Music Perception 21 (4): 457–498. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2004.21.4.457.

- Leman, M. 2016. The Expressive Moment: How Interaction (with music) Shapes Human Empowerment. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Leydon, R. 2001. “Debussy’s Late Style and the Devices of the Early Silent Cinema.” Music Theory Spectrum 23 (2) (Fall 2001): 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1525/mts.2001.23.2.217.

- Li, W. 2020. “Analysis on the Necessity of Diversified Cooperation Forms in Violin Teaching in Normal University.” Frontiers in Art Research 2/6: 11–14. https://doi.org/10.25236/FAR.2020.020603.

- Malandrino, D., D. Pirozzi, and R. Zaccagnino. 2019. “Learning the Harmonic Analysis: Is Visualization an Effective Approach?” Multimedia Tools and Applications 78 (23): 32967–32998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-07879-5.

- Marey, E. 1883. “La Station Physiologique de Paris.” La Nature 536: 226–230. doi:n/a.

- Marey, E. 1895. Movement. D. New York: Appleton and Company.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1899. Cinderella. https://youtu.be/s1hzP9yzb_U.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1899. Un homme de têtes. https://youtu.be/IKQRV4XKZt4.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1901. An Extraordinary Dislocation. https://youtu.be/ItgANeGeBOM

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1901. The Man with the Rubber Head. https://youtu.be/SOQwk_373ME.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1903. The Melomaniac. https://youtu.be/OX3XyAASNts.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1904. Le Roi du maquillage. https://youtu.be/xEiGt2l1ohc.

- Méliès, Goerges, dir. 1904. Voyage à Travers l’impossible. https://youtu.be/Pll3zftl5wg.

- Newcomb, A. 1987. “Schumann and Late Eighteenth-Century Narrative Strategies.” 19th-Century Music 11 (2): 164–174.

- Noland, C., and S. A. Ness. 2008. Migrations of Gesture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pardue, L. S., and A. McPherson. 2019. “Real-time Aural and Visual Feedback for Improving Violin Intonation.” Frontier of Psychology 10: 627. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00627.

- Parks, R. S. 1989. The Music of Claude Debussy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Porter, Edward S., dir. 1903. The Great Train Robbery. https://youtu.be/cT6Pz9t89Lk.

- Said, E. 2006. Late Style. London: Bloomsbury.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. 1999. The Primacy of Movement. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Smith, R. L. 1973. “Debussy and the art of the Cinema.” Music & Letters 54 (1): 61–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/734170. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/LIV.1.61

- Solis, J., and K. Ng. 2011. Musical Robots and Interactive Multimodal Systems. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22291-7.

- Toiviainen, P., and P. E. Keller. 2010. “Spatiotemporal Music Cognition.” Music Perception 28 (1): 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2010.28.1.1.

- Trezise, S. 2003. The Cambridge Companion to Debussy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Väliaho, P. 2010. Mapping the Moving Image: Gesture, Thought, and Cinema Circa 1900. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Volpe, G., K. Kolykhalova, E. Volta, S. Ghisio, G. Waddell, P. Alborno, S. Piana, C. Canepa, and R. Ramírez-Meléndez. 2017. “A Multimodal Corpus for Technology-Enhanced Learning of Violin Playing.” Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter.

- Warburg, A. 2020. Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas MNEMOSYNE the Original. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag.

- Welch, G. F. 2007. “Addressing the Multifaceted Nature of Music Education: An Activity Theory Research Perspective.” Research Studies in Music Education 28 (1): 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X070280010203

- Wheeldon, M. 2005. “Debussy and La Sonata cyclique.” Journal of Musicology 22 (4): 644–679. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2005.22.4.644.

- Williamson, James H., dir. 1901. Stop Thief! https://youtu.be/3wtFm19GXZc.

- Williamson, James H., dir. 1901. Fire! https://youtu.be/57SrYj32vmE.

- Zecca, Ferdinand, dir. 1901. Historie d’un crime. https://youtu.be/JuXYwF5JOj8.

- Zecca, Ferdinand, dir. 1905. Scenes of Convict Life. https://youtu.be/_QhM9HpxJ6U.