ABSTRACT

In the twenty-first century, there has been significant discussion worldwide about students and their learning processes. This study, designing with a student-centred education (SCE) training for three school music teachers over the nine weeks, aims to fill a gap left by the inadequate number of empirical studies examining the implementation of music lessons in China in an SCE era; it also aims to support a global understanding of SCE’s pedagogical adaptation to the Chinese context by using a multiple case study conducted in Province X. The findings illustrate that although SCE has been well promoted in China and its adaptation might seem to be characterised by teacher-centred education, there might be within music education an adjusted SCE adaptation with reasonable contextual challenges and difficulties. Thus, in lieu of descriptions of the Chinese adaptation of SCE as a ‘failed implementation’, this study reveals a more nuanced situation in which SCE is adapted to China’s specific cultural and logistical contexts with large classes, in which instruction takes place.

Introduction

Student-centred education (SCE), also called ‘learner-centred’ or ‘child-centred’ education, is an educational approach whereby students’ learning progress is founded on their responsibility and individuality, and whereby teachers’ control of the classroom and direct content delivery are deemphasised (Schweisfurth Citation2020). The epistemology that underpins SCE holds that learning occurs through a combination of individual and social interactive constructional processes. Internally, the cognitive constructional process provides new insights into knowledge inquiry driven by highly individual learning processes that receive, refine, adapt, and construct (Eni Astuti Citation2018). From an external perspective, the exploration of social construction has supported an understanding of how social interaction influences and shapes the process of knowledge construction (Wiggins Citation2015). Consequently, with its strong emphasis on both individual and social knowledge construction, SCE and its related pedagogies, such as autonomous learning, inquiry-based learning, activity-based learning, and project-based inquiry, have become the prevalent learning approaches in the twenty-first century and have been incorporated into many schools’ curricula internationally (Biase Citation2019; Mtika and Gates Citation2010; Schweisfurth Citation2013; Sin Citation2015).

However, after decades of promotion and much praise for its successful implementation, several issues have arisen relating to SCE’s adaptation to different contexts. The major obstacles to authentically implementing SCE in a given context include a lack of teachers’ belief in SCE (von Oppell and Aldridge Citation2021), physical difficulties related to handling large numbers of students (Wang Citation2011), insufficient support from local governments (Brinkmann Citation2015), inadequate professional development (Yu and Leung Citation2019), and multiple interpretations of SCE’s related concepts (Bremner Citation2020). The criticisms that SCE is a Western importation unacclimatised to every context (Thompson Citation2013) and that concepts related to it are interpreted differently (Bremner Citation2020) constitute essential concerns for educators seeking to adapt a worldwide educational approach to local practice. Educational contexts matter significantly.

In support of this view, this multiple case study investigates the adaptation of SCE from the perspective of school music teaching in China because (1) SCE has been widely promoted in China’s national curricula for decades (Sun and Leung Citation2014) and (2) China’s large class sizes, averaging 40–60 students (Yang Citation2023), provide a contrast to the implementation of SCE in Western contexts with smaller class sizes (Brinkmann Citation2015). The results not only offer an in-depth understanding of how teachers in China’s music teaching context have implemented lessons within the milieu of SCE but also provide unique insight into how well-acknowledged SCE pedagogies have been adapted to China’s local context and the challenges that have arisen.

School music education in China

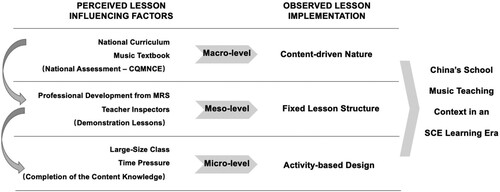

The formal school educational system in China comprises four levels: pre-school, primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education. Because primary (Years 1–6) and secondary (Years 7–12) education are required to follow the guidance for national school curricula, they are also commonly referred to as ‘school education’. In the case of China’s school music education, an overview of the current status of music teaching can be described at three levels.

At the macro level of national educational intention, current school music education is guided by national curriculum standards and teaching textbooks. The national goals for music education are outlined in the most recently issued integrated arts education curriculum for Primary (Years 1–6) and Junior Secondary (Years 7–9) called the Arts Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education (2022 Edition) (Ministry of Education Citation2022), the music curriculum for Senior Secondary (Years 10–12) called the General High School Music Standards (2017 Edition) (Ministry of Education Citation2017), and the 11-textbook series that complements these curricula. These provide teachers with theoretical guidance covering comprehensive content structure, knowledge, and instructional approaches (Yang Citation2023).

At the meso level, where theory is transformed into practice, school music education is guided additionally by the Music Researcher System (MRS), which was first established at different hierarchical levels (province, city, district/county, and school) in China in the 1950s (Wu Citation2021). A distinct group of music teachers, who are recognised as music inspectors and who function as music leaders/instructors, work for their local MRS. With the purpose of aligning local/contextual practices with national goals, the MRS organises professional educational events, such as curricula and textbook studies (Sun and Leung Citation2014), and lesson demonstration events (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023), not only to improve teaching quality, but also to sustainably support the supervision of teachers’ competencies (Liu Citation2011).

At the micro level of school practice, music teaching is highly influenced by the upper two levels of guidance. Researchers have noted a top-down knowledge transmission from curriculum goals to curriculum acceptance (Yu and Leung Citation2019) and a strong alignment between national goals and local practice (Yang Citation2023). Based on this, a few Chinese researchers have criticised this hierarchical knowledge transmission for being misaligned with contemporary constructivist educational philosophy in an era of SCE learning, arguing that learners should be allowed to build knowledge flexibly and autonomously (Ji Citation2013; Law Citation2014; Wang Citation2011). In contrast, schoolteachers have highly valued this top-down structure of teaching support and have demonstrated a keenness to participate in more professional development activities to extend their teaching competencies (Sun and Leung Citation2014; Yu and Leung Citation2019). Compared with contexts that have smaller sized classes where greater teaching flexibility is possible, the Chinese education system has developed distinctively (Liu Citation2011), partly because of factors such as large class sizes of 41–61 students (Yang Citation2023), class session durations of around 40 min each (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023), and heavy teacher workloads, whereby almost 50% of teachers teach 16–25 classes per week with additional administrative tasks (Yu and Leung Citation2019).

Adapting student-centred education for school music education

The concept of SCE has been included in China’s school music curricula since 2001 (Ministry of Education Citation2001). The philosophy behind SCE matches the present focus of China’s educational policy on core competencies and quality education, which aims to shift from an emphasis on didactic teacher-centred instruction to autonomous student-centred learning and the promotion of individuality and holistic education to foster well-rounded people (Cui Citation2022). Accordingly, its benefits in supporting students’ autonomy and engagement, enhancing students’ comprehensive learning abilities, and creating an effective learning environment have also led it to be highly recommended and further written about in many Chinese educational publications (Du Citation2022; Wang Citation2022; Yang Citation2018).

However, although SCE’s theoretical aspects have been globally recognised, few empirical studies have examined its application in the context of music teaching in China. Guo, Xu, and Li (Citation2021) conducted a meta-analysis comparing the proportion of empirical research studies contributing to the music education literature in China and the West and found that only 13.49% of Chinese literature provided any empirical evidence. Similarly, another meta-analysis explored the Chinese research articles in CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure – a database edited and published by the electronic magazine of Chinese academic journals) published between 2007 and 2019 and found that only 9.61% provided empirical evidence, with only 0.49% related to elementary school music studies (Yang, Yin, and Guan Citation2021).

Therefore, given the inadequate investigation of how music education lessons are implemented in China, especially involving the adaptation of SCE pedagogies from smaller to larger class sizes in an elementary teaching context (Alford et al. Citation2016; Lerkkanen et al. Citation2016; Windschitl Citation2002), it is necessary to explore the following questions:

In what ways do Chinese elementary school music teachers conduct their lessons?

How do they perceive and reflect on their pedagogical practices regarding SCE?

When strengthening teachers’ understanding of a well recognised SCE through training, how do participants perceive the adaptations and challenges of implementing training content designed for smaller classes in the context of their larger sized classes?

Methodology

In a previous study, the authors investigated the implementation of lessons in China by systematically observing general demonstration lessons in province X (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023). Building on research, the first author, with a Chinese identity, continued investigating this follow-up study, using a multiple case study method (Yin Citation2009) to explore lesson implementation in the same province but in regular school music settings. The second author is a professor from Hong Kong, China, with experience in music education research. As the supervisor of the first author and a mentor for this study, he acts as a triangulation to further strengthen the study’s trustworthiness.

Generally, the case study methodology investigates, observes, interprets, analyses, and interacts with a specific case or several cases by using a smaller targeted sampling strategy to gain in-depth understanding, facilitate reflection, and find solutions (Eriksson and Kovalainen Citation2008). In this study, a multiple case study was undertaken, taking each teacher within the same school teaching context as a single case to conduct comparisons across three teachers at School A in Province X. Within this similar context, the phenomena and results from the teachers, taken as three multiple cases, provided the significance and representativeness of School A. Besides, with the purpose of (1) exploring the natural state of how music lessons are conducted and perceived in China and (2) investigating teachers’ perceptions towards the adaption of SCE designed for a smaller size classroom in a large class size context, a training intervention was embedded in this study. The purpose of this training is first to strengthen participants’ understanding of SCE and then to provide them with teaching resources to design three SCE-based new lessons for experimenting with contextualised SCE implementation.

Participants

Purposeful sampling (Palys Citation2008) was used for this study. Province X is a rapidly changing province that is a leader in the implementation of reform policies, the economy, and education in China’s southern coastal area (Wang Citation2003). School A, located in Province X, is an elementary school, a Key School which has better facilities, teacher quality, and student enrolment numbers than common schools (Yu and Leung Citation2019), that advocates for innovative educational reform. Three female teachers, anonymised using the pseudonyms Sherry, Lily, and Teresa, were chosen as the three multiple cases within School A because (1) they were experienced teachers who had been working in their current positions since the school was founded in 2013, (2) they had participated in training sessions and had shown a willingness to try new pedagogies in practice, and (3) their combined teaching covered all elementary levels. Specific information about the participants is summarised in .

Table 1. Demographic data (N = 3).

Procedure

In general, the data were gathered across nine weeks through a process that was conducted online due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Observations (O) in tandem with semi-structured interviews (I) were the main data collection methods. Written documents in the form of lesson plans and reflection journals were also collected as complementary data to support the understanding and strengthen the triangulation of data interpretation (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2020). In addition, to understand the adaptations and challenges of implementing well-recognised SCE pedagogies in the local context, a three-part SCE training series based on the work of Wiggins (Citation2015) was designed to strengthen the participants’ theoretical and practical understanding. The two rounds of data collection, before and after the training, and the general working procedure are summarised in .

Table 2. The working procedure for data collection.

Observations were conducted on 18 regular school music lessons that were self-recorded by the participants, with each lesson averaging 38 min and involving 43–46 students per class. These comprised two rounds of observations (O1–O3 and O4–O6). With permission from the head of the school, a camera was set up at the back of the class to record both the teacher’s and students’ actions. The students and their parents were informed in advance that this study would be conducted and were given the option not to be recorded if they so preferred. Both the teachers’ and students’ in-class behaviour were observed during this process.

After each round of observations, semi-structured interviews (I1 and I2) were conducted using the online meeting platform Tencent Meeting, with each interview lasting 45–60 min. In each interview, four general interview questions were asked to gather the participants’ comparative perceptions of their implementation of their lesson in relation to SCE and to understand the factors that influenced the lesson. These questions were as follows:

How did you prepare and structure your lesson?

What activities have you organised to enhance students’ engagement?

What SCE pedagogies have you used to facilitate students’ learning?

What factors influenced your lesson preparation and implementation?

Another two general questions were added in the second round of interviews to answer the third research question:

What different pedagogies and strategies have you used in experimental lessons?

Were there any challenges and concerns when applying the trained SCE pedagogies in practice?

The conversations were audio-recorded and transcribed into Word documents for further data analysis.

Each written document package included one lesson plan and one reflection journal for each lesson. These were collected from each participant on the second day after each lesson; in total, six lesson plans and six reflection journals comprising six written document packages were collected. These documents were used to help the researchers (a) understand the observed teacher-student behaviours and conversations within lessons and (b) interpret the teachers’ views on lesson preparation, implementation, and reflection.

SCE training

The first author, who has seven years’ experience as a school music teacher and teacher trainer, was the SCE trainer for this project. The book Teaching for Musical Understanding by Wiggins (Citation2015) was chosen as the main training resource because (a) the theoretical content of the book was based on constructivism from a well recognised international perspective, (b) the book included specific detailed lesson plans arranged by grade levels and aligned with SCE pedagogies, and (c) a Chinese translation of the book had been published in 2019. It was thus determined that the book could build the participants’ confidence by helping them gain an international understanding of SCE theory in their mother tongue and by helping them see how it could be implemented in a different cultural context.

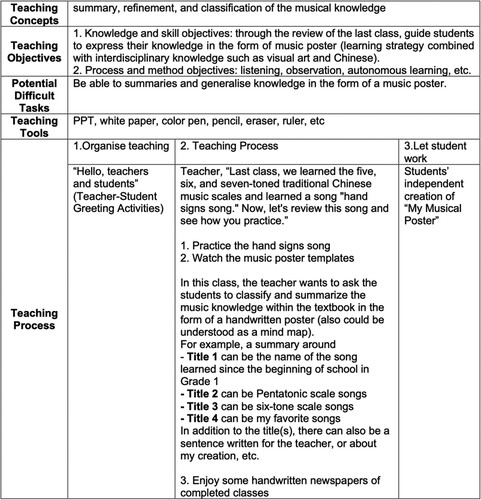

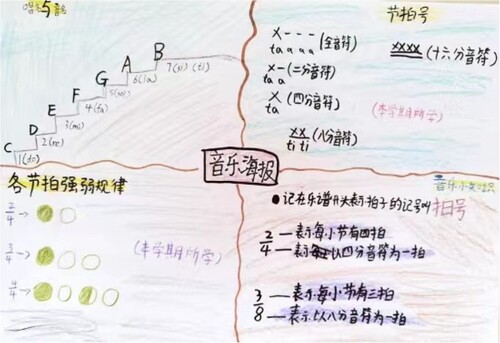

Each training session lasted one and a half hours. At the end of Week 3, before the first training session started, Wiggins’ book was introduced to the participants. The theme ‘What is student-centred education and how can it be implemented?’ also functioned as two guiding questions for teachers to think about and reflect on throughout the training sessions. The first training session focused on sharing the book’s content through a detailed introduction to constructivism in education. After a detailed presentation of the theory, the session focused on applying constructivist teaching to practical settings. The second training session started with a review of the theoretical knowledge discussed in the first training session. In addition to asking teachers to share their thoughts on the application of SCE in China, the second meeting introduced the lesson plans that Wiggins designed for her classroom. The focus of the second training session was how Wiggins’ lesson plans for different grade levels could be applied to the participants’ music classes. The second training session also included twenty minutes of discussion and reflection on the participants’ personal teaching experiences. The third training session started with a discussion of how to combine Wiggins’ lesson designs with China’s local music teaching content and knowledge. After a brief review of the content of the first and second sessions and 20 min of discussion on the design of the experimental lessons, the general structure of the three new lesson plans, the experimental lesson plans (see ), was collaboratively determined to consist of (a) using concept-based learning for students to make connections between different ‘music dimensions’ (Wiggins Citation2015, 34), (b) using interdisciplinary-based learning for students to make ‘interdisciplinary connections’ between multiple subjects (Wiggins Citation2015, 208), and (c) designing a regular textbook-based content-driven lesson plan drawn from participants’ personal understanding of SCE from the training.

Data analysis

A sequential analysis of the systematic observations (Bakeman and Quera Citation2011) and an inductive analysis of the interviews (Saldaña Citation2021) were undertaken for this study. The written documents were reviewed during the analysis of the observation and interview data to reduce the chances of possible bias inherent in any single method and to provide credible evidence to cross-check the consistency of the findings (Patton Citation2014). The first author’s primary school teaching and training experiences meant that there was high familiarity with China school music teaching and the educational context, which further enhanced the trustworthiness of the data. All of the data were anonymised after being collected, analysed, and stored safely within a separate file. Ethical standards and procedures were followed, and the authors’ university undertook the process of ethical review.

Observation data were first entered into the software MAXQDA to calculate the proportion of the teachers’ and students’ behaviours to get a general perception of the school’s regular implementation of music lessons (Alford et al. Citation2016). A list of five categories, Structure of the Lesson, Teacher Behaviour, Activity Types, Student Behaviour, and Learning Approaches, with detailed descriptions, previously defined by the Authors (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023) for understanding the implementing feature of the music lesson, was used to guide the deductive observation undertaken in this study (7). To ensure the accuracy of the coding scheme and the trustworthiness of the large data, initial codes deductively derived from the data were first reviewed by a university professor and later verified by another experienced school music teacher.

Interview data were inductively analysed through a two-cycle analysis (Saldaña Citation2021). The initial codes were selected from the data using descriptive coding but corresponded with the five main observation categories. A coding manual with detailed explanations was developed and arranged into three sections: the original categories from the observations, the descriptions of the codes, and their specific wordings in the interviews. The interviewees later verified all of the codes for credibility. Then, pattern coding (Saldaña Citation2021) was applied in the second cycle of coding. All of the first-cycle codes were clustered into subthemes according to their shared characteristics, and the subthemes were later gathered into several main themes to report the findings from the synthesised data pool (see ). The participants were invited to review the final data analysis and share their feedback and questions.

Table 3. An example of subthemes clustered into the main theme.

Results

In general, answers to the first two research questions came from the data gathered in the first round of data collection. The answer to the third research question mostly relied on the participants’ feelings and thoughts about the SCE training and the experimental lesson plans came from the second round of data.

To properly capture the observed behaviour and documented voices in the research, the findings are first organised below with a general summary of the cross-case analysis (see ) and then specifically describe the similarities and differences according to each of the three cases. The description of each case depicts lesson implementation based on (a) the general structure of the lesson, (b) the teacher’s behaviour and practices, and (c) students’ behaviour and status of learning; these address the first two research questions. The third research question is answered in a report that combines the three cases, also taking a comparative perspective.

Table 4. A summary of cross cases analysis.

Teachers’ lesson implementation and perceptions

Case 1

In terms of the general structure of each lesson, Sherry’s first three classes all demonstrated a similar tendency towards a content-driven structure with a fixed sequence: LI (leading-in)–LNC (learning new content)–GF (going further)–S/F (summary/reflection). For each section of the sequence, Sherry spent a similar amount of time across the three classes, changing the textbook content that was taught. Within each class, Sherry spent the most amount of time on LNC (77.11%, 65.89%, 54%) and the least on S/F (6.78%, 2%, 12.33%).

Sherry explained in her interview that this fixed sequence had a specific ‘structural meaning’ that has been highly recommended by music inspectors and MRS during professional development events:

LI was purposefully designed to support the understanding LNC; LNC was the knowledge from the textbook; GF was to conduct activities to strengthen and extend the knowledge from the LNC session; and S/F was to summarise whatever was learned in the lesson.

Time was so limited! If I extend too many things during the lesson, I will not finish the teaching task. … The required knowledge has been guided in the national curriculum and pretty much written (textualised) in the textbook already. I can easily teach them to students with a set of classroom activities for students to interact with each other. At least, students will be engaged in learning.

You may find out that I rarely conducted group discussions and collaboration. … Group work needs a lot of classroom management. … The large class size is the dominant reason for turning the classroom into chaos easily without good classroom management. So, when I plan, I must make sure that students know (memorise) the song (from the textbook) very well, and then they might be able to work in groups to explore other musical elements in the song. … Again, time is limited in teaching.

Case 2

Lily’s lesson structure showed two similar characteristics to Sherry’s. First, the lesson structural pattern LI–LNC–GF–S/F with a dominant teaching time on LNC (51.56%, 46.22%, 49.44%) was also observed in Lily’s regular lessons. According to Lily, LI and GF were essential for learning new knowledge: the former helped students unconsciously experience music before the transmission of new knowledge began, and the latter made further musical actions after learning. Second, a dominant content-driven and activity-based learning mode was also found in Lily’s lessons, which left limited time for the transitional stage of connecting the new knowledge with what students had previously learned. Similarly, Lily had the same attitude as Sherry when interpreting the importance of an activity-driven lesson structure:

I have to say, teaching music is a kind of artistic experience. Students somehow need to physically experience a musical environment, so they might understand teaching content much better.

While planning the lesson, we should not forget CQMNCE, which is taken once every two years in fourth grade and seventh grade. The tasks in this kind of national assessment are entirely related to the knowledge in the textbook. If we did not follow what the textbook required students to learn, then they might not be able to pass this exam once they get to these grades.

Vignette 1. Examples of Game-based Activities in Lily’s Class

After doing a few short vocal exercises, Lily took a tennis ball out of her toy bag. “I brought a new friend today, and I’m going to sing a song while playing this ball. Please watch carefully.” Then, she started singing a song titled, “Seagull.” “Seagull, seagull, our friend, you are our good friend. … ” Lily sang the entire song, simultaneously bouncing the tennis ball rhythmically on the floor in time with the beat. When she was finished, she turned to the students and asked for volunteers to try what she had done with the tennis ball.

She first called on a boy who bounced the ball while Lily accompanied him by singing “Seagull.” The boy seemed excited and nervous. The unsteadiness of his bouncing rhythm and his occasional expressions of, “Oh … my … god!” filled the class environment with happiness and fun. After providing feedback on how to improve rhythm-keeping while singing, Lily asked all of the students to imagine they had a ball in hand and use hand movements to pretend they were bouncing the ball while singing.

After three minutes of singing and hand-moving, Lily took another four tennis balls out and invited a group of students to “sing and play.” Later, Lily asked the students to explore two types of ball bouncing practices: how to bounce the ball to another student while keeping the beat and how to make the ball bounce around among four students while singing. This game lasted for 20 minutes, and 21 out of 43 students had a chance to play with a tennis ball during this lesson.

Case 3

Unlike Sherry and Lily, who both followed the fixed structural sequence LI–LNC–GF–S/F, Teresa maintained a comparatively simple structure of LI–LNC–GF, with a large amount of time on LNC (60.33%, 74%, 84%) but no time specifically allocated to formally summarise the learned content. This made Teresa’s lesson design more accommodating of different teaching strategies compared with the others. For example, in the second lesson, she spent 100% of class time teaching a new song by engaging in whole-class teacher-led repetitive singing-based practices, whereas, in the first lesson, she spent 7.78% of the time providing opportunities for students’ group exploration of their learning content and 9.22% of the time on individual learning. Consequently, consistent with Teresa’s relatively flexible teaching approach, the students not only had opportunities to work collaboratively and independently, but they also had a good balance of time between actively participating in activities and listening to the teachers statically.

Apart from mentioning the guiding function from national curricula and the textbook, Teresa’s opinion about receiving teaching guidance from professional development sessions organised by MRS was the opposite of Sherry’s, especially in relation to the lesson demonstration event:

I hardly remember that I was participating in any of the official professional teaching training. Although the demonstration lesson, as professional development, was supposed to guide us on how to teach, I preferred watching other teachers’ teachings in their regular music classes because teaching and learning happened differently in the demonstration lesson. … I mostly conduct my teaching behaviour based on my previous teaching experiences.

Vignette 2. Classroom Management in Teresa’s Class

When an activity was supposed to stop, half of the students were still either chatting or mumbling. Teresa walked slowly and closely to students, using her low register voice to say, “It is too loud. I want to praise XX, also praise to YY.” She stopped for a second and then walked slowly towards the students, saying, “praise XY, YZ, ZZ. … ” She called a few students’ names and complimented their good behaviour and attitudes. While she was calling their names, the class started to quiet down. Teresa repeated this classroom management strategy a few times until the students became familiar with this classroom routine and quickly responded to this reminder to be quiet.

Teachers’ perceptions of SCE’s adaptation and accompanying challenges

After the training and their implementation of their new lesson plans, all three participants first confidently described their experimental lessons as successful implementations of SCE. Instead of dichotomising teacher-centred and student-centred education, all three participants were optimistic about the possibility of adapting SCE pedagogies in their large-sized classes, even in a 'teacher-led mode’.

Sherry shared her thoughts in the interview on using a fixed structural sequence to design lessons in an era of SCE learning:

A student-centred teaching pedagogy is to think about students’ needs while preparing teaching content and paying attention to students’ progress in learning knowledge and acquiring skills during the class. I still believe that a fixed lesson structure is like the steady “skeleton of the lesson,” allowing teachers to effectively shape learning through the prepared teaching materials.

After I realised I should provide more chances for students to voice out their ideas, I created this drawing strategy to make my students create music quietly. The success of this strategy gave me confidence that a student-centred strategy can be applied in a large-sized class. I am not sure whether the music inspector or MRS will directly teach us how to do that, but we do need some inspiration on practical strategies to fire up our thinking.

It takes time for Chinese teachers to find a balance between simply imitating successful SCE pedagogies in other countries and adapting these pedagogies from an environment with smaller class sizes to the local context, which has large class sizes. For this, I think teacher training like what we have done previously will be so important for our teachers to work collaboratively and find out the solution.

Discussion

Lesson implementation in regular music classes in China

The research findings give an in-depth picture of how three Key school music teachers in City A conducted their music lessons with their perceptions and the adaptation of SCE in the context of China. Generally, the three participants first demonstrated the hierarchical knowledge transmission from the macro to the micro level, content-driven teaching, fixed lesson structures, and activity-based lesson designs. These features not only roughly depict how elements in China’s music education system appear at different levels and mutually interact but also provide empirical support for determining the causal structure between a perceived curriculum and an operated curriculum. Therefore, following previous studies that have similarly described China’s educational system to be hierarchical and top-down (Sun and Leung Citation2014; Yang Citation2023; Yu and Leung Citation2019), this study provides a comparative view of teachers’ perceptions and their operation of the curriculum (see ) to further understand how music lessons are implemented in China’s regular school setting.

Specifically, at the macro level, previous research has indicated that the national curriculum and textbooks, as expressions of the national goals, provided compulsory content knowledge for teachers to teach (Yang Citation2023). This study reveals that the CQMNCE, as another important element of national education highly aligned with the national curriculum (Yin, Li, and Wu Citation2016), might also pressure teachers to adopt a content-driven teaching mode. Lily described the CQMNCE, the nature of which was to assess students’ learning outcomes, as an additional strong motivation for her to naturally choose content-driven teaching to assure students’ learning.

At the meso level, previous research has recognised and praised the role of music inspectors under the MRS for bridging national goals and practical implementation (Wu Citation2021). In contrast, the participants’ lessons in this study reveal the risk of a highly unified and fixed teaching sequence emerging from music inspectors’ instruction. Because this fixed sequence also largely appears in MRS-organised demonstration lesson events (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023), this finding not only reveals the effect of MRS on lesson implementation but also indicates a potential issue related to teacher-centred education (TCE), in which the teacher shoulders the primary responsibility for knowledge transmission and lets students remain knowledge followers rather than be knowledge constructors (Lerkkanen et al. Citation2016).

At the micro level, although the activity-based lesson design that was revealed in this study was not officially included in the latest national curricula (Ministry of Education Citation2022), it frequently appeared in the participants’ lessons and was often mentioned by them. Based on its benefits of engaging students’ learning, motivating students’ appreciation of the arts, and promoting interactive relationships between teachers and students, an activity-based lesson design, especially in a whole-class learning mode, might be a better solution for teaching large classes with teaching constraints and time pressure.

Interpretation of SCE adaptation for music education in China

Another key issue in this study arises from the comparison between the revealed hierarchical status of Chinese music education and SCE as understood from an international perspective (Schweisfurth Citation2013): this is the issue of how to interpret the TCE-based pedagogical practices that were found in an SCE learning era to dominate the participants’ regular school music lessons. Notably, SCE emphasises individual students’ cognitive development through autonomous knowledge inquiry and shared responsible authority (Eni Astuti Citation2018), but students in the participants’ classrooms mostly followed pre-structured learning content and teacher-led activities. Similarly, while SCE encourages students to interact with their surroundings by communicating and reflecting on ideas (Wiggins Citation2015), students in this study had few opportunities to be heard, whether in group collaboration or in-class discussion, even though they could physically participate in class activities. Also, compared to other common schools, especially Chinese rural schools, which have been reported with a feature in TCE-based education (Sun and Leung Citation2014; Wang Citation2011), participants in School A are in a better educational context in which SCE practice should be more possibly implemented (Brinkmann Citation2015). Thus, based on the above observation, it sounds reasonable to interpret participants’ teaching context as a failure to implement SCE and still follow a TCE mode.

However, regardless of the presence of SCE training, the participants’ expressions of positive attitudes towards SCE and confidence in their ability to adapt SCE to their contextual teaching indicate an interesting tension between what the researchers observed and what the participants perceived. When considering the growing advocacy for SCE in music education alongside the positive attitude about its adaptation (Wang Citation2022; Yang Citation2018), simply describing music lesson implementation in China as a failed adaptation of SCE might overlook the cultural and contextual interpretation of the feature in lesson implementation.

In relation to this, Zhang, Leung, and Yang (Citation2023) advocate the use of collective SCE to understand China’s adaptation of SCE. A comparison of Wiggins’ lesson design (Citation2015) to the participants’ local adaptation in this study highlights Wiggins’ recommendation to teach smaller size classes, her focus on individual students’ needs, and her promotion of individual SCE for individuality (Elena Citation2015). In contrast, the participants’ use of predominantly content-driven teaching following a fixed sequence, the teaching pressures they faced amidst large class sizes, the time limitations they faced, and their requirement to complete the teaching of content knowledge all show that their adaptation of SCE emphasised fitting education to the needs of the whole class and promoting collective SCE for generality (Zhang, Leung, and Yang Citation2023). The activity-based lesson design further shows evidence of participants’ willingness to maintain a student-engaged education in the present era of SCE-based learning. As Lily described,

I believe SCE engages students in class … even in the China context, the physical movement with students experiencing music while following teachers’ directions will still be a way of using SCE to benefit students’ musical learning.

Conclusion

The twenty-first century has featured significant worldwide educational discussion that emphasises the centrality of students and their learning processes in education (Schweisfurth Citation2020). This study fills a gap in this discussion left by an inadequate number of empirical studies of Chinese music lesson implementation in the SCE learning era (Guo, Xu, and Li Citation2021) and supports a global understanding of the adaptation of SCE in the Chinese context.

Like Schweisfurth’s (Citation2020) and Brinkmann’s (Citation2015) concerns surrounding SCE adaptation in developing countries, the results of this study, on a surface level, appear to show a failure to implement SCE in China with the teacher-centred nature of its education. This may be attributed to the entrenched content-driven and fixed-sequence mode of teaching, teachers’ scarce sharing of authority, the insufficient attention given to students’ previous knowledge, and the scarcity of opportunities for students to exercise independent thought or creativity. These characteristics undermine the view that globally recognised SCE has been successfully implemented in China. However, the findings pertaining to the participants’ perceptions of adjusted implementations of SCE provide a unique perspective of how SCE is adapted contextually. When facing adaptive difficulties, it is possible for a region to adjust its educational pedagogy to effectively fit both the contextual requirements and the expectations of SCE-based learning. Here, using a collective SCE perspective to understand the status of teaching in China might support this view.

The limited number of participants in this study with all three female teachers means the results might not be representative and replicable, and the positive feedback about SCE might be a short-term rather than a long-term effect; nonetheless, this study could serve as a starting point for understanding contextual adjustments in the global adaptation of SCE. Future research might take two directions. First, statistical explorations of Chinese teachers’ perceptions of SCE using large-scale quantitative data could strengthen the assumptions made about the status of education in China and support Chinese educators searching for more appropriate teaching strategies to benefit student learning in an era of SCE. In addition, comparison studies exploring lesson implementations in other educational contexts would benefit from investigating SCE’s multiple adaptation and contextual adjustments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Le-Xuan Zhang

Le-Xuan Zhang is a Post-doc Fellow in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at The Education University of Hong Kong (EdUHK). She received her doctoral degree in the Department of Cultural and Creative Arts at EdUHK and worked as a research assistant for two years there. Before that, Le-Xuan received her master’s degree from Boston Conservatory and had six years of teaching experience in China and the USA, as a K-12 IB teacher, curriculum designer, music teacher, and choral director. She is a member of the International Society for Music Education (ISME) and has presented several times at ISME-related conferences and China National Music Education Conferences. Le-Xuan’s interests are in music education, assessment in education, implemented curriculum, international education, teacher education, and student-centered approaches.

Bo-Wah Leung

Bo-Wah Leung is Professor at the Department of Cultural and Creative Arts, and Director of the Research Centre for Transmission of Cantonese Opera at The Education University of Hong Kong. He is currently President of International Society of Music Education (ISME) and an award-winning professor of music for his research in incorporating Cantonese opera into the formal music curriculum. He received the prestigious Musical Rights Award from the International Music Council in 2011 as well as the Knowledge Transfer Award from the HKIEd in 2012 for his leadership in a research project entitled ‘Collaborative Project on Teaching Cantonese Opera in Primary and Secondary Schools’. His research interests include transmission of traditional music in schools and profession, and creative music making.

References

- Alford, B. L., K. B. Rollins, Y. N. Padrón, and H. C. Waxman. 2016. “Using Systematic Classroom Observation to Explore Student Engagement as a Function of Teachers’ Developmentally Appropriate Instructional Practices (DAIP) in Ethnically Diverse Pre-Kindergarten through Second-Grade Classrooms.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (6): 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0748-8.

- Bakeman, R., and V. Quera. 2011. Sequential Analysis and Observational Methods for the Behavioral Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Biase, D. R. 2019. “Moving beyond the Teacher-Centred/Learner-Centred Dichotomy: Implementing a Structured Model of Active Learning in the Maldives.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 49 (4): 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1435261.

- Bremner, N. 2020. “The Multiple Meanings of ‘Student-Centred’ or ‘Learner-Centred’ Education, and the Case for a More Flexible Approach to Defining it.” Comparative Education 57 (2): 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1805863.

- Brinkmann, S. 2015. “Learner-Centred Education Reforms in India: The Missing Piece of Teachers’ Beliefs.” Policy Futures in Education 13 (3): 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315569038.

- Cui, X. R. 2022. “New Direction, Breakthrough, and Journey of Arts Curriculum Reform: Interpretation of Music Curriculum in ‘Arts Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education (2022 Edition)’.” Global Education 51 (7): 3–13. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-WGJN202207001.htm

- Du, H. B. 2022. “Jujiao Hexin Suyang Tuxian Meiyu Gongneng” [Focus on Core Competencies, Highlight Aesthetic Education Function]. Basic Education Curriculum 5: 57–64. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-JCJK202209009.htm

- Elena, D. 2015. “Reconsidering the Didactic Practices from the Perspective of the Respect for the Educated Person’s Individuality.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.119.

- Eni Astuti, N. P. 2018. “Teacher’s Instructional Behaviour in Instructional Management at Elementary School Reviewed from Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory.” SHS Web of Conferences 42: 00038. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184200038.

- Eriksson, P., and A. Kovalainen. 2008. “Case Study Research.” In Qualitative Methods in Business Research, 115–136. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857028044

- Guo, B., X. W. Xu, and B. Li. 2021. “Jiyu wenxian de yinyue jiaoyu yanjiu fangfa fenxi” [An Analysis of Music Education Research Based on Literatures]. China Music 5: 32–38. https://doi.org/10.13812/j.cnki.cn11-1379/j.2021.05.005.

- Ji, J. 2013. “Establishing a New Paradigm for Music Education in China: From a Constructivist Perspective.” Unpublished Master’s thesis, Kansas State University. http://hdl.handle.net/2097/15571.

- Law, W. W. 2014. “Understanding China’s Curriculum Reform for the 21st Century.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 46 (3): 332–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.883431.

- Lerkkanen, M. K., N. Kiuru, E. Pakarinen, A. M. Poikkeus, H. Rasku-Puttonen, M. Siekkinen, and J. E. Nurmi. 2016. “Child-Centered Versus Teacher-Directed Teaching Practices: Associations with the Development of Academic Skills in the First Grade at School.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 36: 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.12.023.

- Liu, J. Z. 2011. Zhongguo xuexiao yinyue kecheng fazhan [The Development of China School Music Curriculum]. Shanghai: Shanghai Conservatory Press.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 4th ed. California: Sage.

- Ministry of Education, PRC. 2001. Music Curriculum Standards of Compulsory Schooling (Trial). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

- Ministry of Education, PRC. 2017. General High School Music Standards (2017 version). Beijing: People’s Education Press.

- Ministry of Education, PRC. 2022. Arts Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education. 2022 ed. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press.

- Mtika, P., and P. Gates. 2010. “Developing Learner-Centred Education among Secondary Trainee Teachers in Malawi: The Dilemma of Appropriation and Application.” International Journal of Educational Development 30 (4): 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.004.

- Palys, T. 2008. “Purposive Sampling.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by L. Given, 697–698. Sage.

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. California: Sage.

- Saldaña, J. 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 4th ed. London: Sage.

- Schweisfurth, M. 2013. Learner-Centered Education in International Perspective: Whose Pedagogy for Whose Development? Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Schweisfurth, M. 2020. “Future Pedagogies: Reconciling Multifaceted Realities and Shared Visions.” Documentation. UNESCO. https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/235046/.

- Sin, C. 2015. “Student-Centred Learning and Disciplinary Enculturation: An Exploration through Physics.” Educational Studies 41 (4): 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2015.1007925.

- Sun, Z., and B. W. Leung. 2014. “A Survey of Rural Primary School Music Education in Northeastern China.” International Journal of Music Education 32 (4): 437–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761413491197.

- Thompson, P. 2013. “Learner-Centred Education and ‘Cultural Translation’.” International Journal of Educational Development 33 (1): 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.02.009.

- von Oppell, M. A., and J. M. Aldridge. 2021. “The Development and Validation of a Teacher Belief Survey for the Constructivist Classroom.” International Journal of Educational Reform 30 (2): 138–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056787920939896.

- Wang, Z X. 2003. “Guangdongsheng zhongxiaoxue yinyue jiaoyu xianzhuang pingshu ji duice [An evaluation and countermeasures for Guangdong elementary and secondary school music education.” China: Journal of Xinghai Conservatory of Music 2: 86–87.

- Wang, D. 2011. “The Dilemma of Time: Student-Centered Teaching in the Rural Classroom in China.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.012.

- Wang, A. G. 2022. “Yiwu Jiaoyu Yishu Kecheng Biaozhun (2022 Nian Ban) Xiangguan Neirong Yandu” [Related Content Study of “Arts Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education (2022 Edition)”]. China Music Education 8: 5–10. https://tra-oversea-cnki-net.ezproxy.eduhk.hk/kns/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZYJA202208001&DbName=CJFQ2022

- Wiggins, J. 2015. Teaching for Musical Understanding. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Windschitl, M. 2002. “Framing Constructivism in Practice as the Negotiation of Dilemmas: An Analysis of the Conceptual, Pedagogical, Cultural, and Political Challenges Facing Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 72 (2): 131–175. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072002131.

- Wu, Y. H. 2021. “The Formation and Development of Music Education Researcher System in China Since 1949.” Explorations in Music 2: 8–18. https://www.fx361.com/page/2021/0809/8722556.shtml

- Yang, H. 2018. “Xiaoxue yinyue ketang de gexinghua guanli” [Individualized Management of Music Classroom Teaching in Primary School]. Journal of Teaching and Management 14: 47–49. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/91308a/201814/675350871.html

- Yang, Y. 2023. “Assessing Alignment Between Curriculum Standards and Teachers’ Instructional Practices in China’s School Music Education.” Research Studies in Music Education 45 (1): 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X221099852.

- Yang, Y., A. Yin, and T. Guan. 2021. “Mapping Music Education Research in Mainland China (2007–2019): A Metadata-Based Literature Analysis.” International Journal of Music Education 39 (2): 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761420988923.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Vol. 5. California: Sage.

- Yin, X. K., Y. F. Li, and B. Wu. 2016. “Woguo jichu yinyue jiaoyu zhiliang jiance gongju yanzhi de tansuo yu sikao” [Exploration and Reflection on the Development of Quality Monitoring Tools for Basic Music Education in China]. Art Education 12: 231–232. http://www.cqvip.com/qk/87186x/201612/670700643.html

- Yu, Z., and B. W. Leung. 2019. “Music Teachers and their Implementation of the New Music Curriculum Standards in China.” International Journal of Music Education 37 (2): 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418820647.

- Zhang, L. X., B. W. Leung, and Y. Yang. 2023. “From theory to practice: Student-centered pedagogical implementation in primary music demonstration lessons in Guangdong, China.” International Journal of Music Education 41 (2): 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614221107170.