Abstract

In order to analyze potential social risks, and achieve smooth implementation of investment activities in the China–Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC), we attempt to establish social impact and risk indicators. Both the impacts on the projects and the impacts of the projects are used to develop risk indicators in accordance with the literature review, reality and international standard principles. Using an analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and average value to analyze questionnaires of both Chinese and Pakistani respondents, we identify the importance of various risk indicators. The primary social risks of the western high mountain region include tribal obstacles and religious extremism. The social risks to the southeast coastal plains include preserving the historical and cultural heritage of the area and international protection of national parks. The social risks in north Kashmir include disputes, extremist threats, religious and cultural differences, and the protection of natural reserves. The social risks of the Xinjiang region primarily involve social issues faced by ethnic minorities and environmental pressures.

1. Introduction

In the era of globalization, governments are pursuing economic development, regional connectivity, and national prosperity. The ‘Belt and Road’ (B&R) initiative launched by the Chinese Government in 2013 aims to promote joint development, common prosperity, and cooperation between China and other Asian, European, and African countries via six economic corridors. Footnote 1 It has attracted considerable attention globally. The CPEC, one of the ‘six economic corridors’ and a particularly important part of the overall project, is the ‘construction pioneer’ and ‘flagship project’ of B&R (Chen and Zhang Citation2016). The CPEC will connect the Gwadar Port of Pakistan to China’s northwestern region of Xinjiang via a network of highways, railways, and pipelines. According to the development plan, the CPEC should be completed in the next 15 years and will require a total investment $46 billion (Table ).

Table 1. Projects approved under the CPEC in energy, transport, and infrastructure. *

In total, CPEC projects aim to add some 17,000 megawatts of electricity generation at a cost of approximately $34 billion, including coal, wind, solar, and hydropower. The rest of the money will be spent on transport infrastructure, including construction of 2000 miles of railway track, widening of the Karakorum highway, upgrading the Gwadar airport and existing highways, and extending 125 miles of tunnels linking the two countries. The 193 million people in Pakistan will benefit from the projects. The projects will fulfill energy demands of Pakistan and boost economic growth. However, some projects have caused resentment among Pakistani residents. The land acquisition of the Karot hydropower station in Pakistan will affect both the Punjab province and the Kashmir region. The total land acquisition area is 6,884,109 m2 and will affect 670 people. The land acquisition involves both state-owned and private land, which has caused disputes on compensation standards between different owners and has postponed the process of project construction (Zhou and Yan Citation2016).

All of these issues remind us that the social impacts of the projects should not be underestimated in the light of the investment activities for the CPEC. To date, there are quantified assessments of the social impacts on different industries by various means, such as questionnaires, interviewing, system dynamics, and indicator buildings. The results show that the implementations of major projects have had both negative and positive impacts on affected communities. Particularly, the review of social impacts of hydropower development, infrastructure construction, and energy projects has provided a detailed conceptual idea of the social impacts of different projects, which is to be one of our direct references for building indicators.

1.1. Importance of social impact assessment (SIA)

SIA can be defined as the process of assessing or estimating, in advance, the social consequences that are likely to follow from specific policy actions or project developments, particularly in the context of appropriate national, state, or provincial environmental policy legislation (Burdge and Vanclay Citation1996). It is now conceived as being the process of managing the social issues of development, which aims to influence decision-making and the management of social issues (Esteves et al. Citation2012). Understanding of SIA has been regarded as a useful foundation on which more robust and better-grounded SIA knowledge production may be built (IIED & WBCSD Citation2001). The SIA community is revisiting some core concepts, such as culture, community, power, human rights, gender, justice, place, resilience, and sustainable livelihoods (Walker et al. Citation2000; Burdge Citation2003; Esteves and Ivanova Citation2016). The need for SIA is as great now as ever. Vanclay (Citation2003) explained the core values, principles, and guidelines of SIA, including the principles of equity considerations, socially sustainable development, alternatives of any planned intervention, full consideration of potential mitigation measures of social and environmental impacts and no use of violence, harassment, intimidation, or undue force. Like all assessments, the SIA model is a comparative one. Problems related to the theoretical foundations of SIA and methodological challenges are some of the important issues faced by the paradigm (Barrow Citation2000; Lockie Citation2001; Vanclay Citation2012).

1.2. Social impacts of hydropower development projects

The social issues created as a result of the implementation of dam projects are important and complex. They include the preservation of cultural heritage, the resettlement of large numbers of people, a fair compensation for lost assets, the creation of new communities, the health and well-being of affected populations both upstream and downstream, the economic survival and development of these populations on a long-term basis, gender issues, and minority rights (Egre and Sececal Citation2003; Stuart et al. Citation2012; Marcus et al. Citation2012; Kelly and Desiree Citation2013). The social impacts of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) mainly include effects on the rural economy, infrastructure, transportation and housing, culture, health, and gender (Bryan et al. Citation2009). The social impacts of the Ilisu dam involve health issues, repercussions of new roads, gender-related issues and impacts on community relations, religious beliefs and lifestyles (Dominique and Pierre Citation2012). The Three Gorges Dam (TGD) is likely to flood approximately 34,000 ha of agricultural land. The unemployment of almost 1.5 million displaced people and disease risks are the important social effects of TGD (Sukhan and Adrian Citation2000; Zhang and Lou Citation2011; Dominique and Pierre Citation2012; Xu et al. Citation2013). The 2849 displaced people of Santo Antonio and Jirau projects largely comprise fishermen and others who depend on the rivers for their livelihoods (Philip Citation2014). The social impacts of dams involve changes to livelihood strategies due to flooding and being denied access to the remaining bamboo area and having reduced access to natural resources in Cambodia and the Mekong River Basin (Barrington et al. Citation2012; Kuenzer et al. Citation2013; Wang et al. Citation2013; Giuseppina et al. Citation2015).

1.3. Social impacts of infrastructure construction projects

The literature on the social outcomes of high-speed railway can be grouped under five main headings, namely: accessibility, movement and activities, health-related, finance-related, and community-related impacts (Peter and Karen Citation2012). After the opening of the Tohoku Shinkansen, cities close to it grew in population by 32% whereas those in the same region but in more remote locations saw no growth (John and Graham Citation2008). The results show high public acceptance of the high-speed railway due to perceived low environmental and social risks and high economic and social benefits. Accidents, land occupation and noise disturbance were of the highest concerns regarding China’s high-speed railway construction (He et al. Citation2015). The highway portion of the planned infrastructure would cause 120,000–270,000 km2 of additional deforestation over 20–30 years by clearing 400,000–1,350,000 ha of land per year. Deforestation inevitably leads to a loss of opportunity for sustainable use of standing forests, including tapping the value of environmental services (Philip Citation2002; Karst et al. Citation2009). The Qinghai Tibet Railway (QTR) will cause a dramatic influx of people from inland China and attract tourists from around the world. An increase in tourism will also result in a substantial increase in population, infrastructure and related human activities, which in turn will have dramatic impacts on local and regional environments (Zhang et al. Citation2008). More important, all tourism plans and programs are prepared by national, regional, or local authorities and are likely to have significant environmental effects (Lemos et al. Citation2012).

1.4. Social impacts of energy projects

The major social impacts include shifts in employment and an increase in occupational health and safety problems. A labor force will be needed in agriculture and forest production to cut, harvest, and transport biomass resources and for the operation of the conversion facilities (S.A & Naseema Citation2000). The results show that e-waste recycling in Pakistan has a potential negative contribution on the majority of social impact categories in the ‘worker’ stakeholder category. In the case of ‘community,’ e-waste recycling was seen as a source of livelihood for many, and this subcategory was rated positively (Umair et al. Citation2015). Meschtyb et al. (Citation2005) used interviewing, participant observation, and comparisons of the combined data to note that the development of the oil extraction industry and expansion of sea transport operations can bring benefits and disadvantages to the local population. The negative impact includes fewer employment opportunities for local people because they lack the required skills. The construction of the Hibernia offshore oil platform from 1990 to 1997 had significant negative social impacts on local communities (Storey and Jones Citation2003). Future development of the oil industry and marine transport will bring changes to the life of local and indigenous people (Meschtyb et al. Citation2005). The social and environmental impacts of renewable energy are wide ranging, and the social impacts of wind energy mainly include bird strikes, noise and visual interference (Saidur et al. Citation2011), despite it being the most sustainable energy followed by hydropower (Annette et al. Citation2009). Although wind energy is considered an environmentally sustainable power source, associated developments can give rise to an array of potential environmental effects, including visual, noise, ecological, land use, and marine impacts (Phylip-Jones and Fischer Citation2013, 2015).

In order to consider the CPEC’s potential social impacts on the world, countries, regions, communities, and at the project level, we suggest that the SIA of CPEC investment activities should be implemented for both the impacts on the projects (macro) and the impacts of the projects (micro)risk indicators perspective. The poor prospects of SIA and collaborative planning in China lie not only in the weak framework for environmental legislation but also in all institutions concerning state–society relations, the socialist governing ideology and traditional Chinese culture (Tang et al. Citation2008). The lack of SIA in Chinese project evaluation has resulted in social factors associated with this major loophole in the project’s approval and supervision process and with a tendency to ignore the project’s social impact on local residents. Social contradictions and social conflicts have been induced to local communities through land acquisition and the demolition of houses by the project, resulting in significant social issues. If we can perform a scientific assessment of the social impact of the project at the beginning of an investment, excessive social contradictions can be prevented (Teng et al. Citation2014).

Until now, there has not been a sufficiently comprehensive and systematic social impact analysis of investment and construction activities in the CPEC region. To fill this gap, this paper will perform two primary tasks. First, it will conduct a SIA of the CPEC investment activity with social risk indicators through a literature review and analysis of questionnaires from both the Chinese and Pakistani sides. Second, we will analyze the social impacts on different regions of CPEC with comprehensive risk scoring, which could become a SIA template and roadmap for other countries or regions.

2. Indicators and methods

2.1. Case study

The study area is located in the Indus River Basin between 23°13′ N and 40°18′ N latitudes and 60°00′ E and 79°57′ E longitudes. It has a total geographical area of 922,000 km2 and a population of approximately 189,319,400 people. According to the development plan between China and Pakistan Government, the CPEC’s scope includes Pakistan and Kashagar, along with China’s Tumxuk City, Artux City, and Akto County. The CPEC started in Xinjiang, Kashagar, and ended at Gwadar Port, Pakistan, for a total length of 3000 km. It is a combination of highway, railway, and cable channels and is an important part of the B&R.

2.2. Regional discourse

The territory of Pakistan consists of four provinces, two federal territories, and two special regions of Kashmir. Detailed social information about the CPEC region is described in Table , which indicates that the southeastern CPEC region has the largest population, the highest per capita gross domestic product (GDP) and the most developed industrial and agricultural areas. The southwestern and northern regions have a lower population and GDP. The data for the Chinese region are from the Kashgar region, where the GDP is significantly higher than that of Pakistani provinces because of recent growth and urbanization (KGIW Citation2017).

Table 2. Regional discourse of CPEC.

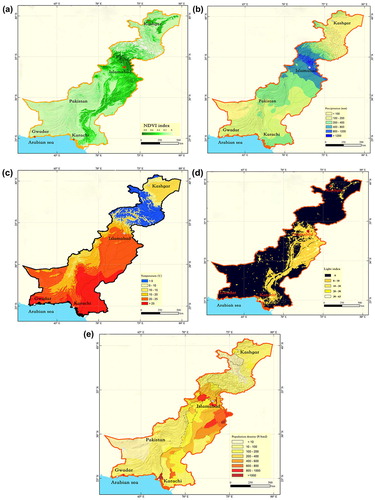

Figure shows the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), precipitation, temperature, light index, and population density of the CPEC. Figure (a) shows that the NDVI is high in the southeastern region, and relatively low in the southwestern and northern regions. In Figure (b), the high precipitation is mainly located in the southeastern and middle regions. In Figure (c), the Kashmir region has the lowest temperature of the CPEC region because of its high altitude and it is becoming increasingly warmer in the southern area of the CPEC. It is noted that the temperature in Kashgar is normal compared to that of Kashmir and the southern part of the CPEC. In Figure (d), the light index shows that in the southeastern region of CPEC, especially in Punjab Province, there are intensive population activities, which can reflect the economic development level to a certain extent. And it is consistent with the population density presented in Figure (e).

Figure 1. The socio-environmental conditions of the CPEC area with: (a) NDVI; (b) Precipitation; (c) Temperature; (d) Light index; and (e) Population density. Source: Authors.

Based on the information on CPEC regional and natural conditions, resources and economic development situation, and findings from previous studies, the CPEC is divided into the western high mountain region, the southeastern coastal plain region, the northern Kashmir region, and China’s Xinjiang region (Figure ).

2.3. Indicators and explanation

Either directly or indirectly, social risks will have different social impacts to investment activities. Therefore, we use the different social risks in the paper as our assessment indicators. The paper divides the social risks of investment activities in the CPEC region into macro- and micro-risks based on field research, questionnaires, and some principles and regulations set by international institutions, including the Environmental and Social Framework of the World Bank (WB Citation2017), the Safeguard Policy Statement of the Asian Development Bank (ADB Citation2009), the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol of the International Hydropower Association (IHA Citation2009), the Environmental and Social Assessment Procedures of the African Development Bank (AfDB Citation2015), and the Environmental and Social Framework of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB Citation2016), as well as practice in Pakistan and China and a related literature review (Walker et al. Citation2000; Egre and Sececal Citation2003; Meschtyb et al. Citation2005).

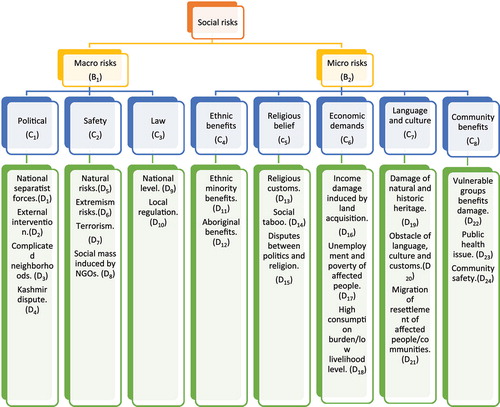

The macro-risks include political risks, safety risks, and legal risks, whereas micro-risks include issues involving ethnic benefits, religious beliefs, economic demands, language, culture, and community benefits (Table ).

Table 3. Social risk indicators of CPEC investment activities and explanation.

2.4. Methods

In recent years, risk management has been studied extensively in construction project management because of its practical importance (Aminbakhsh et al. Citation2013). Sometimes, we want to make risk management quantitative to assess projects’ potential impacts. However, benefits and costs are often difficult to express in monetary terms, especially when some of those benefits or costs, such as ‘improved accuracy’ and ‘learning efforts’ are intangible (Wijnmalen Citation2007). The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is a decision method proposed by Saaty for multiple schemes or multiple objectives. The main advantage of the AHP is its capability to check and reduce the inconsistency of expert judgments. The AHP is an effective method for solving the above-referenced problems. This method should be combined with other evaluation methods to reflect the real situation of venture capital projects to provide a basis for making the correct decision (Wei et al. Citation2004; Zhang and Li Citation2005). The AHP has been widely applied in the fields of multi-factor and multi-target decisions, scheme optimization and asset evaluation. With the development of project risk management, this method has been introduced into risk assessment projects as an effective risk management tool (Du and Deng Citation2005; Li Citation2009; Sun Citation2009). Furthermore, the AHP can compensate for the deficiencies of the expert investigation method. The qualitative comparison results from expert investigation methods are used for quantitative analysis, which is especially suitable for project risk management involving multiple indices and schemes (Ding and Shi Citation2004; Li and Yang Citation2005). The AHP is a good choice for assessing the risk of the construction of mining projects and port investments (Tian and Yu Citation2011). Most social impacts are related to human behavior and activities, which are often unpredictable and difficult to evaluate. However, analysis and judgment by familiar or proficient experts and managers in relevant areas and relevant industries can be useful to quantify qualitative problems and make them easier for people to understand and accept.

Therefore, in this paper, the AHP and average value combined with the regional discourse method (RDM) are applied to understand the social risks induced by investment activities in the CPEC region. Spatial analysis is a mode of thinking and a tool with multidisciplinary features. Its remarkable characteristic is that it has many sources, various methods, and complicated techniques (Zhao and Wang Citation2011). The understanding of spatial relations is defined between objects and events rather than in a coordinate system between fixed points and involves the greater consideration of differences in social space, spatial distribution, and their resulting interaction (Shi and Ning Citation2005). The RDM is a qualitative method based on the concept of human geography and regional divisions of the study area with experts’ experiences and opinions.

Through an analysis of the social risk factors that affect the CPEC, this paper constructs a hierarchical model of social risks in the economic corridor of China and Pakistan (see Figure ). The model consists of three levels: the target layer (B), the factor hierarchy (C), and the indicator hierarchy (D) (Figure ).

To build the judgment matrix, we consulted 15 domestic and foreign experts (including 5 sociology experts from the World Bank, 6 related enterprise managers from state-owned enterprises and 4 government officers from the Ministry of Environmental Protection, PR China) to discuss each layer of elements combined with the importance of Saaty 1–9 to obtain the judgment matrix.

In accordance with the above calculation steps, the weights of the influencing factors of B1 and B2 are calculated. In this paper, the weights of influencing factors of macro-risk are calculated as an example given below:

(1) Calculate geometric mean

= 0.5

= 2,

= 1 can be obtained.

(2) To normalize

,

can be obtained.

(3) Calculate the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix

=

=

(4) Calculate consistency index . and test the consistency.

Consistency index R.I = 0.58, then,

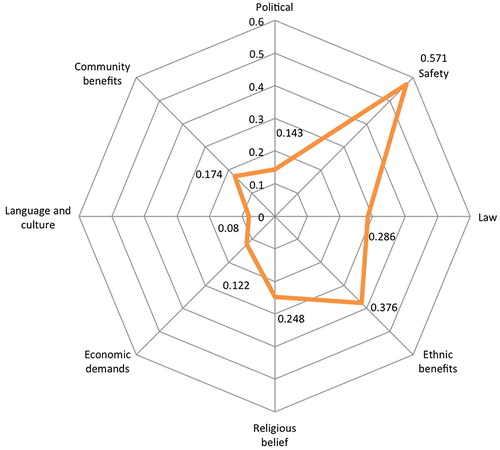

Consistency ratio C.R < 0.1 meets the requirements for consistency. We calculate the weights of micro-risk with the same methods to obtain the weights of the influencing factors. The weights of each factor are shown in Figures and .

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Results

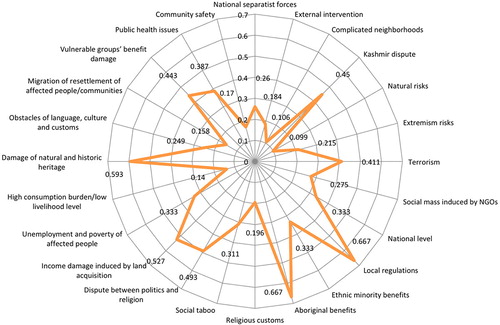

The different weights of each factor mean the different risk levels that gave us the basic direction for further discussion. When we established the importance of different indicators, we referred to the risk level between different indicators, which means that the higher the weight, the higher is the risk. In the target layer, the safety risk (including natural environment risks, extremism risks, terrorism and mass movement induced by NGOs) and ethnic benefits risk are 0.571 and 0.376, respectively, which are higher than other factors. In the factor layer, the risk of aboriginal benefits, local regulations, damage to natural and historic heritage, income damage induced by land acquisition, political and religious disputes, the Kashmir dispute and damage to vulnerable groups’ benefits are 0.667, 0.667, 0.593, 0.527, 0.493, 0.450, and 0.443, respectively, which are higher than other risks factors.

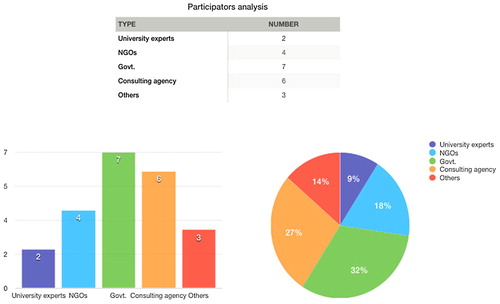

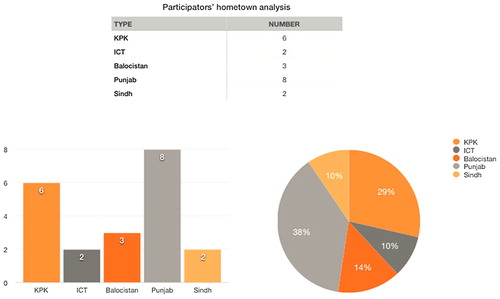

In order to analyze the viewpoints of the concerned officials, experts and stakeholders from Pakistan on CPEC’s social risk levels, we sent out a questionnaire to different participants. We received responses from 22 participants from government and nongovernment institutions and stakeholders from different provinces and regions of Pakistan. Most of these participants were from universities, NGOs, Pakistan’s Government, and consulting agencies. Their institutional distribution is shown in Figure . The respondents were mainly from Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province (KPK), Baluchistan, Punjab and Sindh Province. Their hometown/provincial distribution is shown in Figure .

The questionnaire was based on the different risk intensities at macro and micro levels. We set five different risk intensities and assigned an appropriate score according to the severity of the risk (see Table ).

Table 4. Risk intensities and assigned scores.

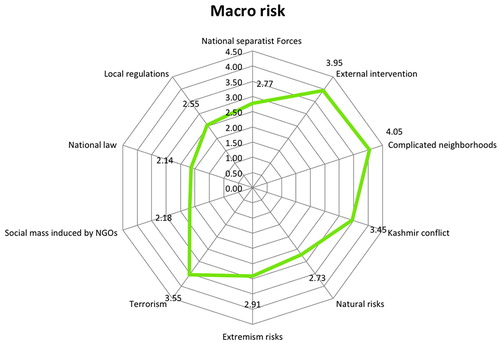

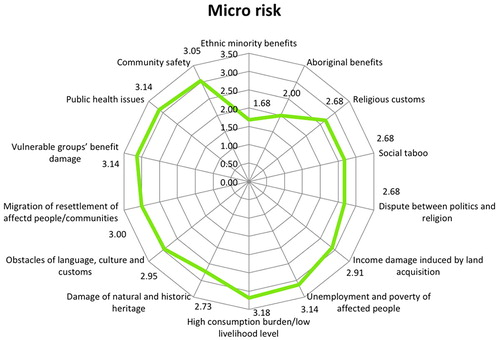

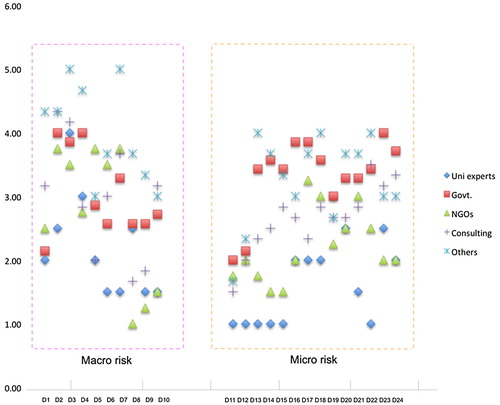

After receiving the responses from the participants, we averaged the risk scores for macro and micro levels. It is evident from Figure that the complicated neighborhoods possess highest risk at the macro level. External intervention, the Kashmir conflict and terrorism also possess higher risks due to more concerns from the Pakistani side. Figure depicts that unemployment and poverty, high consumption burden/low livelihood level, migration and resettlement of affected people or communities, vulnerable groups’ benefit damage, public health issues and community safety have a relatively high risk at the micro level. In contrast, ethnic minority benefits and aboriginal benefits belong to lower risk, and others are at the middle risk level. Furthermore, we averaged values for each factor (see Table ) for different types of participants as shown in Figure . It is evident from Figure that other stakeholders (including employee and data analyst) indicate the highest risk, whereas university experts show the lowest risk at the macro level. NGOs, government officials, and consulting agencies indicate moderate risk at the macro level. In addition, other stakeholders and government officials show higher risk than university experts at the micro level, while NGOs and consulting agencies indicate moderate risk at this level.

It is assumed that the proposed Chinese investments in Pakistan have different socio-environmental impacts. Some noted environmental impacts include increased noise level and declined air and water quality. Zhang et al. (Citation2017) emphasized that noise and individual risks are the important risks during the construction of CPEC. Huang et al. (Citation2017a) demonstrated that air quality and water consumption are the top two challenges of planned Chinese investments in Pakistan. These studies are more focused on environmental risks and challenges based on surveys or expert opinions. Some studies described social impacts involving unpredictable political risks and rapidly increasing livelihoods difficulties. Shi et al. (Citation2017) focused on various social risks in the CPEC region, such as political dispute, tribal barriers, religious extremists, and ethnic minorities by comparing the social, economic, and cultural aspects of the two countries. Using the AHP and average value methods, we found that from Chinese side the safety risk (0.571) (including natural environment risks, extremism risks, terrorism and mass movement induced by NGOs) and ethnic benefits risk (0.376) are the most important risks. As the CPEC region covers the areas with vulnerable social and natural environment, the safety risks of natural environment and terrorism are still the biggest and challenging to cope (Huang et al. Citation2017b; Tu et al. Citation2017; Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform of Pakistan Citation2018). Construction of 2000 miles of railway track, widening of the Karakorum highway, upgrading of existing highways, and extending 125 miles of tunnels linking the two countries will occupy the land temporally and will acquire it permanently. The ethnic minorities might be facing landlessness, joblessness, income loss, and displacement induced by land requirement (Singh Citation2008; Zhou and Yan Citation2016). For the safety risk, the project implementer should make protective measures to reduce disasters caused by earthquakes and debris flows. For extremism and terrorist attacks, the Chinese and Pakistani Government should fully coordinate and communicate, and take the necessary measures to protect the safety of staff and steadily promote the implementation of the project.

From Pakistani side, it is evident that the complicated neighborhoods (4.05) possess highest risk at the macro level. External intervention (3.95), and terrorism (3.55) also possess higher risks due to more concerns. It shows that Pakistani side is more concerned about the interference of neighborhoods and terrorist, which has been a trouble in Pakistan for decades (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China’s Citation2015; Xie Citation2016). Unemployment and poverty (3.14), high consumption burden and low livelihood level (3.18) have a relatively high risk at the micro level. In contrast, ethnic minority benefits and aboriginal benefits pose lower risks. Although it can be seen that the CPEC projects will create more job opportunities, increase employment rate, and boost economic growth (Malik and Chen Citation2017; Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform of Pakistan Citation2018), concerned Pakistani authorities are still worried about their benefit loss due to the implementation of CPEC. For the risks of unemployment, involuntary resettlement and livelihood sustainability, the stakeholders, such as the government, enterprises, and affected groups should fully consider the actual difficulties of the affected groups on the basis of complying with the relevant compensation policies, especially the rights protection of women, the elderly, and the children. It is highly expected that in plight of some unavoidable impacts, due consideration should be paid to the alternatives of any planned interventions.

3.2. Discussion

We combined the quantitative results and the opinions of experts and respondents (Figures , , , and ). Considering the similarities of project construction requirements, different industries in different regions of the CPEC are confronted with common social risks, such as land acquisition, involuntary resettlement, displacement, compensation, protection of labor and women’s rights.

3.2.1 Land acquisition and involuntary resettlement compensation

China has announced that it will invest US$46 billion in Pakistan by 2030, which it hopes will end the country’s chronic energy crisis and transform it into a regional economic hub (Huang et al. Citation2017a). For the process of building infrastructure, energy resources, and a manufacturing industry, areas of land will be required. Therefore, China is involved in land acquisition and house demolition, which will lead to different degrees and scales of resettlement, including the relocation of entire villages. The affected persons have experienced unemployment, loss of housing, and other economic losses. For the APs and social economic system to achieve sustainable livelihoods, there must be a large amount of investment in development. Although project staff can do a great deal to improve resettlement outcomes, there is always a preexisting social and political context of poor families (Vanclay Citation2017). In particular, consumption structure and living standards have resulted in conflicts. At the same time, because of different understandings of resettlement procedures and compensation standards, there could be demonstrations and even mass incidents.

3.2.2. Labor rights protection

In the course of societal development, people have a right to know about the passage of laws and regulations. Accordingly, an increasing number of government organizations, agencies and NGOs are attempting to strengthen the protection of labor rights by enacting various laws and regulations. The extant literature has found individual facets of political and economic globalization, such as trade, FDI, and individual treaties and conventions, to have varying impacts on labor rights (Blanton and Blanton Citation2016). To successfully process project construction, operations, and maintenance work, the project owners must hire a certain number of local workers. Consequently, project owners need to propose higher requirements for project investment, not only in accordance with local labor and employment laws and regulations related to payment but also in response to workers’ demands, which, if handled improperly, will trigger protests, strikes, and even bloodshed.

3.2.3. Women’s rights protection

The status of women and the protection of women’s rights are gradually being recognized as important by the public. In 2010, Pakistan promulgated regulations on the protection of women from workplace harassment, which formally protected women’s rights and interests by providing varying degrees of punishment to offenders. Therefore, if an investment project involves women’s rights, its operations must be strictly in accordance with the provisions of local religious customs, and appropriate measures must be requested to protect women’s rights.

In October 2015, the authors went to the Chinese part of the CPEC for research and conducted formal discussions with the local Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Transportation, and the Port Management Committee to understand the opinions and attitudes toward CPEC construction. Based on the importance of the indicators through the AHP methods, along with the RMD and the investigation of the CPEC, the RDM focuses on the social impacts of a divided region in accordance with the natural and social foundations. This is different from the regional level in that it aims at small, undivided regions. Based on the divided regions, we seek to analyze the risks that will affect the investment activities and the investment activities, which in turn will have impacts on local communities.

3.2.4. Potential risks due to regional difference

3.2.4.1. Western high mountain region

The full name of the Pakistan tribal area is the Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA). It is a buffer zone of 27,000 square kilometers along the Afghanistan border. Most of the inhabitants are Pashtun tribes. The tribal areas have great autonomy and, to some extent, the ambassadors have relatively independent powers. Tribal areas have no administrative or judicial institutions. Tribal elders primarily negotiate the internal affairs of the tribal areas. If conflicts arise within the tribe or between tribes, the elders pass judgment based on traditional customs. It is necessary to pay attention to potential risks for investment projects. If not handled properly, these risks may lead to project failure, bankruptcy, and huge losses. Yang (Citation2013) suggested that development policies that address tribal problems should be regional in scope. Planning policies should be designed to limit the importance of resource-based factors, whereas the social value system should play a significant role in restructuring the economy.

In addition to the relatively independent tribal area, Baluchistan and the Northwest Frontier Province border Afghanistan and Iran. Although most people believe in Islam, the struggle between Sunni and Shia Muslims has become increasingly fierce. Young Sunni Muslims have invested in and been inspired by Islamic State (ISIS), with their extreme religious ideology, and have attempted to use force to destroy the Shiites, causing social unrest. This situation presents an enormous potential risk for investment in the western Pakistan mountain area. Extreme conflict can lead to project delays, including forced shutdowns, which may cause huge losses and threaten the safety of the staff.

3.2.4.2. Southeastern coastal plain region

According to the Pakistan Heritage and Integration Department statistics, the Taxila, Harappa and Moen jo Daro archeological sites and the Rohtos, Badshahi, Uch-i-Sharif, Thatta and Makli historical and cultural sites are in the Punjab and Sindh provinces. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has recognized most of these sites as world cultural heritage sites. These cultural sites have benefited government agencies to study history and allow local residents to appreciate their glorious heritage. If the foundation survey is not sufficiently comprehensive during the process of project preparation, development, construction, and operation, it may indirectly lead to a series of social risks and permanent damage to ancient historical and cultural sites.

National parks were established to protect primitive civilization, historical landscape, and precious wildlife. National parks benefit from a worldwide protection movement for natural and cultural protection and have developed a series of progressive protective measures. Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh provinces include La Suhanra National Park and Kirthar National Park. La Suhanra, as a Forest National Park reserve, is situated in the southeast of the desert fringe of Punjab Province and was established to prevent the further westward flow of the desert and to reduce the frequency of city sand accretion. Kirthar National Park is located near the Kirthar Mountains and is the main wild animal protection area in the Sindh Province. The existence of national parks limits project investment activities.

3.2.4.3. Northern Kashmir region

Across conflict areas, international experience shows that projects in cross-border or disputed and conflict areas often experience potential political crises, which makes the security problems of projects and construction more prominent. Railways and highways are the CPEC’s main infrastructure construction projects. When the projects are close to or traverse the disputed Kashmir area, the conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir sovereignty may intensify. The international part of the CPEC may use the collective will as the foundation to counter the project’s construction.

Influenced by a specific geographical position and geopolitical game, the Kashmir area is facing a more prominent extremism threat, including violent terrorism and national separatism. In recent years, local Taliban forces in Pakistan have gradually developed and expanded. They continue to commit terrorist attacks in Pakistan occupied Kashmir, and the regional security situation is not optimistic. National separatist forces may use the interests of minority groups to create disputes and intensify contradictions. Violent terrorism and separatism have often targeted China’s project in Pakistan in an attempt to gain economic benefits and political rights, and employee safety cannot be guaranteed. The benefits of the projects cannot be shared by the local people, which not only increases the possibility of project failure but also potentially affects the stability of the local social order.

Kashmir is a multireligious place in which 77% of the local people are Muslim, 20% are Hindu, and a minority are Sikh and Buddhist. Significant differences in religious beliefs, customs, and culture lead to social risk in relation to investment projects in Kashmir. First, specific types of construction may threaten cultural relics or religious facilities. Second, conflict between religious groups may be caused by different standards of resettlement compensation. Pakistani land ownership includes private landlord ownership, Yuto Walid ownership and forms of state ownership, in which land belongs to private landlords, private farmers, and the nation, respectively. Because of private ownership, land may have more than one owner, and malicious land acquisition may raise land prices. When the scope of land acquisition involves different provinces and different types of land, it is difficult to establish a standard of compensation, and land acquisition efficiency will remain. Third, local religious resentment and exclusion may be caused by Chinese employees’ failure to understand local customs and religious customs. For example, 97% of Pakistan’s people are Muslim and are forbidden to drink alcohol. Wine and beer cannot be purchased in restaurants or shops. People in Pakistan are also forbidden to eat pork; they eat beef, mutton, and poultry.

Kashmir’s natural environment is relatively fragile, and its ecological system is unstable. Consequently, the government created the Khunjerab National Park Nature Reserve to protect endangered animals, including the snow leopard, wild goats, and Marco Polo sheep in the Himalayan habitat and to maintain the biodiversity of the mountain plateau region. However, site planning and project construction, especially for highways, railways, bridges, tunnels, and other infrastructure projects, often causes threats such as the destruction of vegetation and the blockage of animal migration channels in the construction stage and the completion of operations. This may lead to intervention and opposition from extreme environmental conservationists and NGOs.

3.2.4.4. Xinjiang region, China

The Kashagar area, including China’s Tumxuk City, Artux City, and Akto County, is a multiethnic region that includes the Uygur, Han, Hui, and Tajik. Based on historical and practical events, some ethnic minorities enjoy only limited participation in social and economic development. As a result, some groups and individuals cannot obtain shared benefits of investment projects and may be negatively affected and damaged by the project, causing them to fall into a poverty trap.

Environmental issues have become a high-risk factor for social conflicts. Xinjiang occupies a unique geographical position, with the Tianshan and Pamir Plateau from north to south through the West Kunlun Mountains around the region, the east of the Taklimakan Desert with a cold climate, rainfall, and low organic matter content in the soil. The region’s main rivers are supplied by water from ice and snow melt; the overall ecological environment is relatively fragile, and recovery capability is poor. Therefore, the development and construction of project activity can destroy the balance of the ecological environment, resulting in damage to plants and animal habitats along with other environmental concerns. Because local people rely on the natural environment, the environmental issues caused by project activities may affect people’s farming and lives through the destruction of land, grassland, and other material resources. In addition, it can be expected that for the affected residents, family income, and quality of life will decrease, which may severely affect stakeholders.

4. Conclusion

The CPEC is portrayed as a win-win initiative. The investment and construction of energy and infrastructure projects under the CPEC will affect both Pakistan and China in social, economic, cultural, resource, and other dimensions. The CPEC is a long-term project, and its impacts will remain for a long period. We developed indicators and used the questionnaire method, distributed to expert stakeholders, to judge the risk level based on different indicators from both Chinese and Pakistani perspective. The questionnaire from Chinese side revealed that safety and ethnic benefit risks are higher that other factors. According to the Pakistani side, political and safety risks are higher than other risks. We also found that different stakeholders within Pakistan have different attitudes to different risks. Based on the questionnaire results and the four divided regions in accordance with the RDM, we determined that social risks of the western high mountain region include tribal obstacles and religious extremism. The social risks to the southeast coastal plains include preserving the historical and cultural heritage of the area and international protection of national parks. The social risks in north Kashmir include disputes, extremist threats, religious and cultural differences, and the protection of natural reserves. The social risks of the Xinjiang region primarily involve social issues faced by ethnic minorities and induced by the environment. In this paper, we focused on the social impacts of the projects in the CPEC region using the different methods based on the perspective of experts and interviews with both Chinese and Pakistani stakeholders. As a part of the B&R, the CPEC has played an important role for Chinese foreign investment. The SIA for the CPEC is an advanced case study that has provided important and necessary social risk information for the CPEC and has provided a reference and roadmap for other parts of the B&R and other nations’ foreign investment. However, due to the limitations of samples, we argue that the specific SIA needs to be conducted with local stakeholders before the projects are implemented.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number 13&ZD172, 15BSH037], the Jiangsu Social Science Foundation [grant number 15SHB004], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number KYLX16_0690] and the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the survey and workshop participants. The authors are thankful to Bouckaert Frederick, Patil Rupesh for reading and editing the language for this article. And we are grateful for comments received by anonymous reviewers that have helped improve the article.

Notes

1. ‘Six economic corridors’ refer to the New Eurasian Continental Bridge Economic Corridor, the China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor, the China Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, the China–India–Burma Economic Corridor, and the China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor.

References

- Abbasi SA , Abbasi N . 2000. The likely adverse environmental impacts of renewable energy sources. Appl Energy. 65:121–144.10.1016/S0306-2619(99)00077-X

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank . 2009. Safeguard policy statement. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32056/safeguard-policy-statement-june2009.pdf.

- [AfDB] African Development Bank . 2015. Environmental and social assessment procedures. Abidjan: quality assurance and results department, compliance and safeguards division. http://www.afdb.org/leadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/SSS_%E2%80%93vol1_%E2%80%93_Issue4_-_EN_-_Environmental_and_Social_Assessment_Procedures__ESAP_.pdf.

- [AIIB] Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank . 2016. Environmental and social framework. http://www.aiib.org/upload.le/2016/0226/20160226043633542.pdf.

- Aminbakhsh S , Gunduz M , Sonmez R . 2013. Safety risk assessment using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) during planning and budgeting of construction projects. J Saf Res. 46:99–105.10.1016/j.jsr.2013.05.003

- Annette E , Vladimir S , Tim JE . 2009. Assessment of sustainability indicators for renewable energy technologies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 13:1082–1088.

- Barrington DJ , Dobbs S , Loden DI . 2012. Social and environmental justice for communities of the Mekong River. Int J Eng Social Justice Peace. 1(1):31–49.10.24908/ijesjp.v1i1.3515

- Barrow CJ . 2000. Social impact assessment: an introduction. London: Edward Arnold.

- Blanton R , Blanton SL . 2016. Globalization and collective labor rights. Sociol Forum. 31(1):181–202. DOI:10.1111/socf.12239.

- Bryan T , Yvonne B , Daming H . 2009. Social impacts of large dam projects: a comparison of international case studies and implications for best practice. J Environ Manage. 90:S249–S257.

- Burdge RJ , Vanclay F . 1996. Social impact assessment: a contribution to the state of the art series. Impact Assess. 14(1):59–86. DOI:10.1080/07349165.1996.9725886.

- Burdge RJ . 2003. The practice of social impact assessment background. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21(2):84–88. DOI:10.3152/147154603781766356.

- Chen JD , Zhang JQ . 2016. Location of Sino-Pakistan economic corridor in ‘one belt one road’ construction. J Xinjiang Normal Uni (Philosophy And Social Sciences). 37(4):125–133.

- Ding XQ , Shi S . 2004. Application of the analytic hierarchy process to project risk management. J Ocean Univ China. 34(1):97–102.

- Dominique E , Pierre S . 2012. Social impact assessments of large dams throughout the world: lessons learned over two decades. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21(3):215–224. DOI:10.3152/147154603781766310.

- Du XL , Deng SM . 2005. The application of analytic hierarchy process in venture investment project evaluation. J Nanchang Univ (Engineering & Technology). 27(4):63–66.

- Egre D , Sececal P . 2003. Social impact assessments of large dams throughout the world: lessons learned over two decades. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21(3):215–224. DOI:10.3152/147154603781766310.

- Esteves AM , Franks D , Vanclay F . 2012. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):34–42. DOI:10.1080/14615517.2012.660356.

- Esteves AM , Ivanova G . 2016. Using social and economic impact assessment to guide local supplier development initiatives. Handb Res Methods Appl Econ Geogr. 5:1–30. DOI:10.4337/9780857932679.00035.

- Giuseppina S , Frauke U , Sour K , Pin DL . 2015. Hydropower, social priorities and the rural-urban development divide: the case of large dams in Cambodia. Energy Policy. 86:273–285.

- He GZ , Mol APJ , Zhang L , Lu YL . 2015. Environmental risks of high-speed railway in China: public participation, perception and trust. Environ Dev. 14:37–52.10.1016/j.envdev.2015.02.002

- Huang YY , Fischer TB , Xu H . 2017a. The stakeholder analysis for SEA of Chinese foreign direct investment: the case of ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative in Pakistan. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 35(2):158–171. DOI:10.1080/14615517.2016.1251698.

- Huang H , Xu XY , Chen CJ . 2017b. The political risk and suggestions for Chinese enterprises’ investment in Pakistan. Int outlook. 2:132–148. DOI:10.13851/j.cnki.gjzw.201702008.

- [IHA] International Hydropower Association . 2009. Hydropower sustainability assessment protocol. http://www.hydrosustainability.org/IHAHydro4Life/media/PDFs/PDF%20docs/language%20docs%20for%20draft%20hydropower%20sustainability/HSAF-Draft_HSAP_Section_I_August_2009-english.pdf.

- [IIED] International Institute for Environment and Development, [WBCSD] World Business Council for Sustainable Development . 2001. Social impact assessment in the mining industry: current situation and future directions. IIED and WBCSD.

- John P , Graham W . 2008. The Ex-ante and Ex-post economic and social impacts of the introduction of high-speed trains in South East England. Planning Pract Res. 23(3):403–422. DOI:10.1080/02697450802423641.

- Karst TG , Wouter B , Bert VW . 2009. social impacts of transport: literature review and the state of the practice of transport appraisal in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Transp Rev. 29(1):69–90. DOI:10.1080/01441640802130490.

- Kelly M , Desiree D . 2013. Cumulative biophysical impact of small and large hydropower development in Nu River, China. Water Resour Res. 49:3104–3118. DOI:10.1002/wrcr.20243.

- [KGIW] Kashgar Government Information Website . 2017. National economy. http://www.kashi.gov.cn/Item/8758.aspx.

- Kuenzer C , Campbell I , Roch M , Leinekugel P , Tuan VQ , Dech S . 2013. Understanding the impact of hydropower developments in the context of upstream-downstream relations in the Mekong river basin. Sustain Sci. 8:565–584.10.1007/s11625-012-0195-z

- Lemos CC , Fischer TB , Souza MP . 2012. Strategic environmental assessment in tourism planning-Extent of application and quality of documentation. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 35:1–10.10.1016/j.eiar.2011.11.007

- Li WY . 2009. Application of AHP analysis in risk management of engineering projects. J Beijing Univ Chem Technol (Social Sciences Edition). 65(1):46–48.

- Li JH , Yang JM . 2005. An application of hierarchical analysis method in risk evaluation of mining project investment. Mining R&D. 25(6):9–12.

- Lockie S . 2001. SIA in review: setting the agenda for impact assessment in the 21st century. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 19(4):277–287.10.3152/147154601781766952

- Malik AR , Chen XP . 2017. [Translator] the economic perspective of the China-Pakistan economic corridor. Pacific J. 25(5):92–99.

- Marcus W , Andrea H , Peter J . 2012. Environmental and livelihood impacts of dams: common lessons across development gradients that challenge sustainability. Int J River Basin Manage. 10(1):73–92. DOI:10.1080/15715124.2012.656133.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China . 2015. Vision and Actions on jointly building silk road economic belt and 21st-century maritime silk road. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1249618.shtml.

- Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform of Pakistan . 2018. Long term plan for China-Pakistan economic corridor (2017–2030). http://cpec.gov.pk/long-term-plan-cpec.

- Meschtyb NA , Forbes BC , Kankaanpää P . 2005. Social Impact Assessment along Russia’s Northern Sea Route: petroleum transport and the Arctic Operational Platform (ARCOP). Arct Inst North Am. 58(3):322–327.

- Peter J , Karen L . 2012. The social consequences of transport decision-making: clarifying concepts, synthesising knowledge and assessing implications. J Transp Geogr. 21:4–16.

- Philip MF . 2014. Impacts of Brazil’s Madeira River Dams: unlearned lessons for hydroelectric development in Amazonia. Environ Sci Policy. 38:164–172.

- Philip MF . 2002. Avanca Brasil: environmental and social consequences of Brazil’s planned infrastructure in Amazonia. Environ Manage. 30(6):735–747.

- Phylip-Jones J , Fischer TB . 2013. EIA for wind farms in the United Kingdom and Germany. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 15(2):1–30.

- Phylip-Jones J , Fischer TB . 2015. Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) for wind energy planning: lessons from the United Kingdom and Germany. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:203–212.10.1016/j.eiar.2014.09.013

- Saidur R , Rahim NA , Islam MR , Solangi KH . 2011. Environmental impact of wind energy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 15:2423–2430.10.1016/j.rser.2011.02.024

- Shi S , Ning YM . 2005. Evolution on connotation of space in human geography. Scientia Geographica Sinica. 25(3):340–345.

- Shi GQ , Zhang RL , Peng SP , Wu S , Tang B . 2017. Social risks evaluation of overseas investment pertaining to China-Pakistan economic corridor construction. J Hohai Univ (Philosophy And Social Sciences). 19(1):59–64.

- Singh G . 2008. Mitigating environmental and social impacts of coal mining in India. Mining Engineers’ Journal. 8–24. (June), 8.

- Stuart O , Jamie P , Ashok C , David D . 2012. Dams on the Mekong River: lost fish protein and the implications for land and water resources. Global Environ Change. 22:925–932.

- Sukhan J , Adrian S . 2000. Resettlement for China’s Three Gorges Dam: socio-economic impact and institutional tensions. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 33:223–241.

- Storey K , Jones P . 2003. Social impact assessment, impact management and follow-up: a case study of the construction of the Hibernia offshore platform. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21(2):99–107. DOI:10.3152/147154603781766400.

- Sun JH . 2009. Application of comprehensive analytic hierarchy process evaluation model in project risk assessment. Stat Decis. 23:164–167. DOI:10.13546/j.cnki.tjyjc.2009.23.011.

- Tang BS , Wong SW , Lau MCH . 2008. Social impact assessment and public participation in China: a case study of land requisition in Guangzhou. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28:57–72.10.1016/j.eiar.2007.03.004

- Teng MM , Han CF , Liu XH . 2014. Index system for social impact assessment of large scale infrastructure projects in China. China Popul Resour Environ. 09:170–176.

- Tian JF , Yu Q . 2011. Application of analytic hierarchy process in port investment project evaluation. Commun Finance Account. 1:8–9. DOI:10.16144/j.cnki.issn1002-8072.2011.02.021.

- Tu HZ , lin YH , Qiao YR . 2017. Visual analysis of the trend of terrorism in Pakistan. Southeast Asia South Asian Stud. 4:94–99.

- Umair S , Björklund A , Petersen EE . 2015. Social impact assessment of informal recycling of electronic ICT waste in Pakistan using UNEP SETAC guidelines. Resour Conserv Recycl. 95:46–57. DOI:10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.11.008.

- Vanclay F . 2017. Project-induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to an opportunity for development? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 35(1):3–21. DOI:10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671.

- Vanclay F . 2003. International principles for social impact assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 21(1):5–12. DOI:10.3152/147154603781766491.

- Vanclay F . 2012. The potential application of social impact assessment in integrated coastal zone management. Ocean Coast Manage. 68:149–156.10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.05.016

- [WB] World Bank. Environmental and Social Framework . 2017. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/383011492423734099/pdf/114278-REVISED-Environmental-and-Social-Framework-Web.pdf.

- Walker JL , Mitchell B , Wismer S . 2000. Impacts during project anticipation in Molas, Indonesia: implications for social impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 20:513–535.10.1016/S0195-9255(99)00040-2

- Wang P , Lassoie JP , Dong SK , Morreale SJ . 2013. A framework for social impact analysis of large dams: a case study of cascading dams on the Upper-Mekong River, China. J Environ Manage. 117:131–140.

- Wei X , Xia EJ , Li QX . 2004. Comprehensive evaluation of risks in venture investment project decision–making. China Soft Sci. 2:153–157.

- Wijnmalen DJD . 2007. Analysis of benefits, opportunities, costs, and risks (BOCR) with the AHP–ANP: a critical validation. Math Comput Model. 46:892–905.10.1016/j.mcm.2007.03.020

- Xie GP . 2016. The construction of the ‘China-Pakistan Economic Corridor’ and its cross-border non-traditional security governance. Southeast Asian Affairs. 167(3):23–37.

- Xu XB , Tan Y , Yang GS . 2013. Environmental impact assessments of the Three Gorges Project in China: issues and interventions. Earth Sci Rev. 124:115–125.10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.05.007

- Yang Y . 2013. Reform of Pakistani Tribal Areas and Chinese Role. South Asian Stud Q. 3(3):56–64.

- Zhang F , Li HM . 2005. Application of analytic hierarchy process in evaluation of venture capital project. Commercial Res. 24:11–13. DOI:10.13902/j.cnki.syyj.2005.24.004.

- Zhang QF , Lou ZP . 2011. The environmental changes and mitigation actions in the Three Gorges Reservoir region, China. Environ Sci Policy. 14:1132–1138.10.1016/j.envsci.2011.07.008

- Zhang RL , Andam F , Shi GQ . 2017. Environmental and social risk evaluation of overseas investment under the China-Pakistan economic corridor. Environ Monit Assess. 189:253. DOI:10.1007/s10661-017-5967-6.

- Zhang TJ , Baker THW , Cheng GD , Wu QB . 2008. The Qinghai-Tibet railroad: a milestone project and its environmental impact. Cold Reg Sci Technol. 53:229–240.10.1016/j.coldregions.2008.06.003

- Zhao Y , Wang YS . 2011. Progress of spatial analysis. Geogr Geo-Inf Sci. 27(5):1–8.

- Zhou XJ , Yan DC . 2016. On land acquisition risks about intentional projects in the perspective of ‘One Belt and One Road’ – from the case of Karot Hydropower Station in Pakistan. J Xiangtan Univ (Philosophy and Social sciences). 40(4):53–59.