ABSTRACT

Written guidance can contribute to the development of effective SEA, delivering relevant information for those involved in policy, plan and programme making processes. Generally speaking, guidance should aim at setting best practice standards. However, to date, how guidance is impacting on SEA effectiveness and how it is best developed and maintained has not been explored to any great extent. As a consequence, it has remained unclear how a key ingredient of effective SEA, namely the support of an enabling context, should be approached. In this paper, we look at the perceived relevance of written guidance for the delivery of effective SEA, based on a two-stage survey with 26 practitioners (all with over 10 years of experience) from the UK and the Republic of Ireland, conducted between 2015 and 2017. Survey participants included representatives of the regulatory, consultancy and academic sectors. Our findings indicate that guidance can promote SEA effectiveness if it: (a) aims to go beyond basic legislative requirements; (b) is able to respond to the specific situation of application; (c) can establish a minimum standard for SEA; and (d) is able to stimulate the advancement of quality standards within a tiered approach to SEA.

Introduction

A key condition for Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) being able to develop into an effective decision support instrument in policy, plan and programme (PPP) making is an adaptability to the specific context of application (Hildén et al. Citation2004; Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; Gunn and Noble Citation2009). This is why the format of SEA is expected to differ, depending not just on the characteristics of a particular PPP system, but also on a range of wider important contextual aspects. These include, for example juridical, administrative, political and cultural aspects (see, e.g. Marsden Citation1998; Fischer Citation2005; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013).

As context is never static, but evolving over time, SEA is subject to continuous change. Consequently, it can be assumed that understanding of what contributes to best SEA practice is continuously evolving in the light of experiences made and knowledge acquired (Fischer Citation2007; Retief Citation2007; Posas Citation2011). There is thus a need to reflect on guidance regularly. This is best achieved with an interactive approach between those releasing guidance and those using it (Fischer et al. Citation2019).

It is within this context that responsive and ‘flexible’ SEA requirements are needed. However, there is no consensus on what flexibility should look like. As a consequence, flexibility has been interpreted in different ways (Fischer Citation2014; Tshibangu and Montaño Citation2016; Nadruz et al. Citation2018). Importantly, there have been suggestions that if SEA is defined too loosely, it may become an instrument that is used at will, in particular by those wanting to see particular outcomes (Malvestio and Montaño Citation2013).

With regards to a desired responsiveness and flexibility, Fischer (Citation2003) observed that following widespread criticism of the rational theoretical underpinnings of SEA, suggestions on how to improve the tool made at various points since the end of the 1990s have focused particularly on a better integration of SEA into ‘real’ decision-making and procedural flexibility (Kørnøv and Thissen Citation2000; Nielsson and Dalkmann Citation2001; Richardson Citation2005). Whilst this discussion has been important for SEA, an unintended side effect has been that it has lost much of its earlier clarity (Fischer and Seaton Citation2002). This has led to some policy, plan and programme (PPP) makers advocating supposedly simple and ‘painless’ approaches that, however, have often been found to be ineffective, in particular when compared with traditional formalized procedures that are usually perceived as being more ‘painful’ (Fischer Citation2007).

Whilst there are some widely accepted overall principles of SEA (see, e.g. Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2016), there are differences in the perception of responsiveness and flexibility between different disciplines and also systems/countries. There are, for example, countries where SEA has been reported to function in splintered, disperse PPP and project frameworks with a low capacity of self-organization (e.g. Brazil and Mexico according to, respectively, Montaño et al. Citation2014; González et al. Citation2014). Here, applying SEA effectively and integrating it into PPP making is seen as particularly difficult, unless SEA is considered an opportunity to support a more systematic organization of them (Malvestio et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, there are established systems in which PPP and project frameworks are more or less clearly understood (which is the case in, e.g. many European Union member states). Here, integration of SEA has been said to be often comparatively straightforward (Fischer Citation2006).

Differing and incoherent contexts partially explain the observation made by Noble et al. (Citation2012) that SEA guidance is frequently vague and – at times – confusing. On the other hand, specific guidance has been observed to be able to support effective SEA (Brown and Therivel Citation2000; Fischer Citation2006; Therivel Citation2010; Fischer and Yu Citation2018). This is associated with at least two principles of SEA, namely: (1) to deliver useful context specific information to PPP makers, as well as; (2) an ability to influence the content of the PPPs to which SEA is applied. In this context, two aspects have been observed to be key for effective guidance; delivery of suitable information, and; integration into PPP processes (Fischer et al. Citation2018). However, most existing SEA guidance has been observed to focus on a generic description of procedural stages and on the preparation of SEA reports only (Brown and Therivel Citation2000; Noble et al. Citation2012).

Whilst many advocates of SEA have stressed the importance of guidance for an effective application of the instrument, and in this context have made various suggestions of what this should look like (Partidario Citation2000; Caratti et al. Citation2004; Schijf Citation2011), to date, only a limited number of professional papers have been devoted to critically reviewing existing SEA guidance, not just its usage, but also its development. Those papers specifically dealing with guidance have focused mainly on the SEA process with some being dedicated to specific SEA procedural stages, including scoping, the development of alternatives, recommendations, preparation of the SEA report, monitoring and follow-up, as well as stakeholder and public engagement (see, e.g. Therivel et al. Citation2004; Noble et al. Citation2012; Fischer et al. Citation2019). Many other aspects are not well covered, though, including questions on how to integrate SEA with the PPP making process and how exactly SEA should be considered in decisions. More broadly speaking, guidance is often seen as a mechanism for bridging legislation and practice. In this context, De Montis et al. (Citation2016, p. 78) suggested that ‘SEA guidelines are prepared to help administrative bodies and practitioners convert in practice the general principles expressed in laws’. This is why SEA practitioners and theorists frequently suggest that guidance should provide details not only on procedures and methods, but also on wider issues, for example the context of an overall decision framework. This was suggested by, for example Noble et al. (Citation2012) when reflecting on the results of a survey on SEA guidance in Canada and also by Fischer (Citation2006), elaborating on what guidance for transport SEA should address.

A key challenge for SEA performance globally is an unclear impact on final PPP decisions. This challenge is perceived to be connected with a lack of effective integration of SEA into PPP processes along with weaknesses of underlying PPP frameworks that are frequently unsystematic and ill-explained (Fischer et al. Citation2009; Rega and Baldizzone Citation2015; Phyllip-Jones; Fischer Citation2014; Malvestio et al. Citation2018). Linkages with other PPP and project procedures are often particularly poorly explained (Brown and Therivel Citation2000; Therivel et al. Citation2004; Fischer Citation2006).

It is within this overall context that recent empirical research has suggested that SEA legislation is barely advancing in improving the integration of SEAs and PPPs. Baresi et al. (Citation2017), for example, observed that SEA legislation and guidance used in many regions of Italy are only complying with the minimum requirements of the European SEA Directive and the Italian National Decree, but do not really deal with integration in any meaningful way (see also Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006). Furthermore, De Montis et al. (Citation2016) suggested that the narrative of SEA guidance merely highlighted the need to effectively link SEA and PPP processes, however, without advancing on how to do this.

In order to contribute to the debate on what guidance for effective SEA should look like, and how it should be developed and maintained, in this paper the authors reflect on experiences of practitioners in the United Kingdom (UK) and the Republic of Ireland. At the heart of our paper are the results of a survey developed in two stages and conducted over two years (2015–2017). This consisted of personal interviews with a number of experienced practitioners (regulators, consultants and academics), followed by the application of written questionnaires with further SEA experts. All of these have had over 10 years of involvement with guidance in a number of different ways, including their preparation and use. This allowed them to critically reflect on their effectiveness.

Subsequently, first, our methodology is introduced. This is followed by a presentation of the main results and a critical discussion of them. Conclusions are drawn with regards to how to develop and maintain effective SEA guidance.

Methodology

Based on a comprehensive literature review, an analytical framework was designed to support the research underlying this paper (). This was the basis for a survey which was conducted with experienced UK and Republic of Ireland SEA experts. A systemic approach was adopted, assuming that the different actors, instruments, and procedures that are part of the SEA process should fulfil specific roles and functions in order to be able to maximize the overall system’s performance (mostly in terms of outcomes’ effectiveness).

Following Therivel (Citation1993), Jones et al. (Citation2005), Chaker et al. (Citation2006) and Fischer (Citation2007) an SEA system can be described on the basis of its regulatory context, the level of integration with PPP-making, its procedures and methodological elements, as well as the processes of review, approval and follow-up. The underlying rationale of this paper is that guidance needs to be able to contribute to all these elements of an SEA system.

The survey consisted of 18 personal interviews, adopting a semi-structured approach. Each interview took about 2 h and involved two senior managers and one analyst from the English Environment Agency; five representatives (of which two senior managers and three analysts) of the Scottish government (Environment Protection Agency, Historic Scotland, Natural Heritage); two representatives of local government; one senior manager from the Irish Environment Protection Agency; four senior consultants (professionally based in England and Scotland); and three academics (based in England).

The framework was introduced to the interviewees, explaining its rationale. Further clarifications were made during the interviews when requested by the interviewees. The interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (the first author), who would provide explanations, and formulate specific questions, focusing on every individual interviewee.

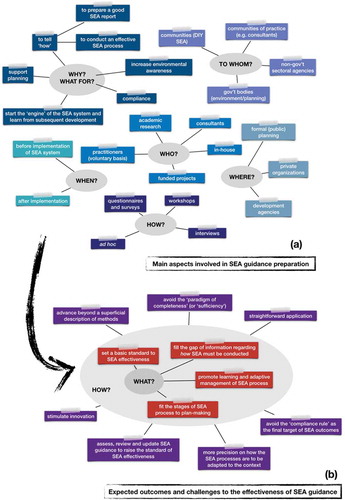

Interviews aimed at capturing perceptions of those interviewed on aspects of effective SEA guidance. It was supported by notes’ taking and observations of the interviewer. This enabled the interviewer to learn about the use of guidance in its particular context (Kawulich Citation2005; Guest et al. Citation2013). Core ideas were subsequently extracted from the data gathered in interviews, which were combined by similarity, thus establishing the key aspects to be considered in the development of SEA guidance. Concept diagrams, that is systematic depictions of concepts in previously defined categories (Eppler Citation2006) were prepared to illustrate the key aspects involved in guidance preparation and expected outcomes.

Following completion of the survey, an online, open-ended questionnaire was prepared. This was completed by eight further SEA experts, including four senior consultants, one representative of a local council, two academics and one senior manager from an environment agency. The questionnaire focused on key aspects of the effectiveness of SEA guidance, considering its content and usage, and included the following questions:

What do/don’t you like about SEA guidance/guidelines overall?

What do/don’t you like about the guidance/guidelines you are most familiar with?

If you were asked to revise/update the SEA guidance/guidelines you are most familiar with, what would be changed? excluded/included?

Considering the manner in which you were introduced to SEA guidance (who introduced you and how? why and where/what was the context?), what did you see as negative and positive aspects?

What would (an) effective SEA guidance/guidelines look like?

What would be a good approach to using SEA guidance/guidelines, considering your role as a practitioner and/or a coordinator of the SEA process?

The responses were codified by core ideas and subsequently grouped into different categories, reflecting the key aspects to be promoted towards a more effective approach to the development of SEA guidance.

Results

An initial important and somewhat unexpected finding is that SEA guidance is not always perceived as an inherent element of the SEA system. In this context, it is revealing that most interviewees had asked for the approach adopted in the underlying research to be clarified before the interviews. This was requested mainly in order to understand the underlying rationale/hypothesis of the research project, which was that guidance/guidelines have specific functions in SEA systems that are important for their effectiveness.

A second and probably not so unexpected finding is that individual perceptions are connected with both, the position occupied and role played by an interviewee within an SEA system. Here, regulators, for example tended to be more positive of the guidance/guidelines than, for example academics.

,) show two concept maps derived from the information obtained through the interviews. These address two questions, namely; (1) ‘what are the main aspects involved in SEA guidance preparation?’ and (2) ‘what are expected outcomes of guidelines and what are the challenges to their effectiveness?’.

Figure 2. (a), (b): context of SEA guidance development; (a) main aspects involved in SEA guidance preparation and (b) expected outcomes and challenges to the effectiveness of SEA guidance.

Main aspects involved in SEA guidance preparation

When looking into what purpose guidelines are produced for, seven main aspects were mentioned, which next to the obvious ‘to tell how to do it’ also include compliance with legal requirements, the support of an increased environmental awareness as well as the support of planning processes. One interviewee suggested that guidelines were needed in order to ‘start the engine for the development of SEA overall and to learn from subsequent development’. The latter implies regular maintenance/updates of guidelines. Finally, two more specific (technical) aspects were mentioned, including help with conducting an effective SEA process and help with the preparation of a good SEA report.

With regards to the question as to whom guidelines are prepared for, four main groups are identified. These include (1) ‘communities of practice’, that is those conducting SEA and preparing the necessary documentation (e.g. consultants). The main interest of those is receiving clear instructions on ‘how to do it’. Secondly, they include (2) government bodies (e.g. those responsible for the environment and planning), whose main interest it is to have a clear indication for how exactly formal requirements, as expressed through e.g. legislation, can be and are translated into action. Thirdly and fourthly, they include (3) nongovernmental sectoral agencies (e.g. environment) and (4) potentially affected communities. For both of these, interest for guidelines is derived from a desire to know about both ‘how to do it’, how legislation can be translated into action and what the scope for changing any particular PPP is.

When it comes to the question as to how guidelines are prepared (i.e. the specific approach taken), three consultative elements were mentioned, including questionnaires/surveys, interviews, as well as workshops. In addition, the possibility of an ‘ad-hoc’ approach for the preparation of guidelines was also mentioned. However, the value of guidelines that are developed in the absence of any consultations with practitioners appears questionable and the usefulness of resulting guidelines is most likely reduced.

With regards to who was developing guidelines, a wide range of possibilities were mentioned. Firstly, they can be prepared ‘in-house’, that is by an authority responsible for SEA. Secondly, they may be developed on the back of funded pilot projects. As a third option, academic research was mentioned. Fourthly, the private sector (i.e. a consultant) might be contracted and fifthly practitioners may decide to get together and write, what could be called ‘informal’ guidelines on a voluntary basis, if they feel there is a gap that needs to be filled.

Finally, when it comes to the question as to when to develop guidelines, two possibilities were mentioned; one before SEA is introduced into a system and one afterwards. Whilst the former will help practitioners ‘straight away’ (and possibly will support the ‘start’ of the SEA system, as previously mentioned), the latter means that experiences already gained with applying SEA can be taken into account in the development of guidelines, thus possibly making them more applied and useful.

Expected outcomes and challenges to the effectiveness of SEA guidance

With regards to the question as to what exactly the outcome of guidelines that enable effective SEA should be, four main components were identified:

to set a basic standard for SEA effectiveness;

to fill a gap in knowledge as to how exactly SEA should be conducted;

to support the integration of the SEA stages into PPP-making; and

to promote learning and adaptive management of the SEA process.

There are a number of aspects that should be considered when aiming at developing and maintaining guidelines in support of effective SEA. These are associated with a range of challenges. Whilst some of these are generic in nature, others are specific. The former include the need to assess, review and update guidelines regularly in order to enhance effectiveness. This is closely connected with a requirement to ‘stimulate innovation’. Furthermore, guidelines should lead to a more straight-forward (i.e. more simple) application of SEA. With regards to the latter, the following aspects were mentioned:

to avoid the ‘paradigm of completeness’; this means guidelines should focus on what is relevant in the specific situation they are prepared for, rather than trying to cover everything that could be remotely (but unlikely to be) relevant; this means scoping in issues that are relevant/significant, and scoping out those that are not.

To avoid the simple ‘compliance rule’ as the main aim of SEA; that is rather than simply complying with basic requirements, SEA should aim at reflecting good or best practice.

To advance beyond the superficial description of methods; there are many references to guidelines not going much beyond a superficial description of methods which could easily be derived from, for example textbooks; this wasn’t perceived by interviewees as being particularly useful.

To be clear about how SEA processes are to be adopted to the specific context; this is a similar point to 3, meaning that guidelines should strive at being precise about how SEA can be applied in a particular situation in practice.

Expected outcomes and challenges are at the heart of a number of key aspects that should be taken into account when aiming at promoting effective SEA guidelines. These aspects can be divided into those that relate to content and those that relate to usage. shows key content related aspects and shows key usage related aspects, derived from expert questionnaires and interviews.

Box 1. Key content related aspects to promote effective SEA guidelines.

Box 2. Key usage related aspects to promote effective SEA guidelines.

Discussion: main themes arising from expert interviews

Issues raised during interviews can be summarized and discussed under a number of main themes, as follows: (1) periods in the life of guidance with differing levels of usage; (2) the threat of legal challenges; (3) the role of the overall institutional and normative context, (4) the need for regular review and revision of guidance; (5) the need to engage in an exchange of best practice; (6) the need for effective tiering between SEA and EIA, and; (7) the need for SEA guidance to support learning.

1. Periods in the life of guidance with differing levels of usage

All interviewees mentioned periods of differing levels of usage in the life of guidance/guidelines. Thus, there are times of more intense ‘activity’ and times of less intense or even no usage. Times of high usage are usually associated with those immediately after publication and also during the phase of ‘adaptation’, that is when practitioners are learning to use new guidance. During these phases, a particular high level of influence on SEA is observed. At times this was said to stimulate experimentation and is also associated with the development of more creative approaches when preparing SEAs. Depending on the capacities for operating SEA, as well as on the status SEA has been able to achieve within PPP making, this phase is frequently followed by one where there is a push towards more minimalist compliance with guidance. This eventually results in setting a [minimalist] standards’ compliance. In interviews, the importance of these different periods was stressed in particular by consultants and government agencies. Statements from these two groups of interviewees are particularly revealing: ‘I usually focus on compliance’ and ‘SEA is not a tick-box exercise, but governments tend to consider it as if it was’. These statements were referring to guidelines that had been used for some considerable time (about 10 years) without any changes being introduced to them.

2. The threat of legal challenges

The threat of legal challenges to SEA can directly affect the approach taken. It may also reinforce the need to demonstrate that SEA and the associated PPP were using reasonable evidence and that they were done according to what is known to be good and ideally best practice. The threat of legal challenges was said to be a major factor in understanding how guidance is used by interviewees, e.g.: ‘as a consultant I want to protect myself from legal challenges’; and ‘planners believe that strictly following guidance, they will be protected from legal challenges’. In this context, SEA was seen as potentially playing an important role for avoiding legal challenges, as was suggested by one interviewee: ‘SEA is my best friend when dealing with the Planning Inspectorate’. If the threat of legal challenges is high, those conducting SEA will aim at sticking closely to guidance and established practices. In this context, guidance is perceived as an important source for deciding on what counts as reasonable evidence and what can be considered to be good practice. This means that those involved in SEA may be particularly resistant to divert from accepted guidance, even if it doesn’t reflect good or best practice (e.g. by being outdated) for fear of litigation. However, most interviewees also suggested that good practice frequently goes beyond what guidance is offering, in particular when it has been around for a long time without being updated. The need to combine compliance and good practice was seen as a particular challenge in this context: ‘Guidance means “beyond legal requirements”, and this must be balanced with the need of compliance’.

3. The role of the overall institutional and normative context

The level of detail provided in guidance on e.g. methods or procedural stages is said to correspond directly to the institutional and normative contexts. Specifically, it means that the more rigid the rules outlined in legislation are, the smaller the scope of diverting from prescribed procedures and methods tends to be. Interviewees also suggested that the institutional and normative context was a catalyst for the ‘compliance issue’ already discussed above under point 2. Whilst there is therefore a challenge for SEA in very rigid contexts, overall, guidance was suggested to be least effective in what may count as legally ‘weak’ systems. In this context, the importance of clear and strong legal requirements was stressed; ‘guidance on its own will not improve the SEA system – legal requirements are always needed’. This has to be seen in the context of a perceived need to be flexible. Weak (less powerful) legislation means that those involved in PPP making may aim at weakening SEA. In this context, there is an associated perception that SEA should be flexible. Finally, autonomy (and associated with this ‘power’ of those responsible for conducting SEA) plays another important role, as was suggested by one interviewee: ’as a public servant, when I find myself in a context of more autonomy to prepare an SEA, I can adopt best practices as a basic standard in our guidance’.

4. The need for regular review and revision of guidance

Interviewees suggested that SEA guidance needed to be continuously reviewed and revised, based on the on-going experiences with SEA as well as advances in knowledge. In this context, it is important that SEA is a quickly developing decision support instrument, for which understanding on what contributes to good practice is continuously advancing. In this context, interviewees suggested that ‘it is our duty to keep guidance updated and focused on effectiveness’. Furthermore, and importantly, interviewees also suggested that ‘after 10 years it needs to be updated – the context has changed’. The problem is that in reality guidance usually isn’t being updated at all and often remains untouched for many years. In this context, one interviewee suggested that: ’basically, updating SEA guidance is to be expected only after changes in legislation’.

5. The need to engage in an exchange of best practice

Exchanging experiences, in particular on best practices through the community of SEA practitioners was said to be particularly important in order to enhance the quality of SEA. Interviewees suggested that ultimately this would also stimulate the development of new approaches to guidance. In this context, one interviewee stressed the importance of the preparation of lists of good practice or ‘recommended’ SEAs: ‘those lists of recommended SEAs [and guidance] are a tool to promote the improvement of guidance, because good examples tend to be followed by consultants and practitioners’.

6. The need for effective tiering between SEA and EIA

The need for effectively tiering SEA and EIA and an associated need to consciously consider outcomes of related SEAs and EIAs from other tiers, sectors and administrative levels was seen as being a key component of effective SEA and it was suggested that guidance should clearly address how this can be achieved. In this context, guidance for different tiers would need to cover different aspects and focus on different issues. There are, for example, differences between short, medium and long term PPPs. Those differences have an impact on uncertainties in baseline evolution and prediction of effects, as well as in the choice of SEA objectives. As a rule of thumb, the higher the strategic level, the lower the level of details to be provided by guidance will be. In practice, guidance was said to very rarely effectively deal with tiering.

7. The need for SEA guidance to support learning

Interviewees suggested that guidance should function as a mechanism to support learning, pushing standards to a higher level, and going beyond simple compliance in order to achieve good SEA practice. In this context, systematic application of SEA (including systematic review and adaptation) was said to be of particular relevance. ‘SEA – and guidance – needs to be applied systematically in order to promote individual, social and institutional learning’. Furthermore, and in the same vein, in order for guidance to be useful, interviewees suggested that ‘SEA must act as a “critical friend” within the planning process’. Finally, a highly technical language adopted in SEA guidance was seen as a barrier to learning and it was suggested that technical language needed to be balanced with very effective communication, to ensure adequate comprehension.

Conclusions

Many authors see guidance as a key component for enhancing SEA effectiveness. In this context, what is usually said to be of particular importance is that guidance is able to; (a) establish a minimum standard for the SEA process and its integration into PPP making, and (b) stimulate a better standard than minimum requirements, in particular with regards to the quality of the SEA process and its various associated elements (e.g. consideration of alternatives, use of state-of-the-art methods).

Whilst our findings partly support these suggestions, it was also observed that in practice, guidance currently rarely achieves all its objectives. Importantly, interviewees stated that whilst guidance can be an enabler of good practice, it can also act as a barrier if it is outdated and/or not representing good practice at a particular point in time, due to, for example being around for too long without any revisions in the light of changing knowledge on effective SEA. In this context, one interviewee suggested that: ‘guidance could be constraining or delaying new improvements in methodologies, and new approaches’. Similar messages were brought forward by representatives of all three groups of interviewees (regulators, consultants and academics). A representative of a government agency even suggested that ‘we felt limited by our [own] SEA toolkit’. This is a clear indication that guidance for effective SEA requires regular/periodic review and revision.

Our findings are in line with what e.g. Hill and Hupe (Citation2002) observed, suggesting that continuous review and adaptation were key components of effective policy implementation. They are also broadly in line with the main messages brought forward by implementation theory (Smith Citation2018). In this context, the notion of ‘improvement cycles’ is a particularly useful concept for understanding how SEA guidance should be developed, reviewed and adapted, consisting of a continuous plan, do, check and act approach (see, e.g. Tague Citation1995).

Institutional and normative context was suggested to play a key role for how guidance needs to be approached in order to support the development of effective SEA, in particular with regards to weak and strong legal compliance traditions. In this context, it is particularly revealing to look at what Craigie et al. (Citation2009) observed for South Africa. They established that only 15% of those involved in EIA act on the respective law because they believe in it, but 70% for fear of litigation. Similar observations were also made in China (Yee et al. Citation2014). In the absence of a tradition of compliance, it will therefore be more challenging for guidance to support effective SEA.

Finally, and generally speaking, interviewees saw a need to approach guidance as a dynamic element of SEA systems. This includes consideration of a number of components, for example monitoring, evaluation and assessment of its use. Here, context was recognized as being of key importance. Overall, it was suggested that SEA guidance should go beyond legal compliance, driving SEA practice to push the boundaries of legal standards and stimulating innovative thinking. It was also suggested that friction and controversy can be seen as providing a good opportunity for e.g. the development of real alternatives and wider mitigation measures.

In conclusion, on the one hand, guidance can promote SEA effectiveness if it is stimulating a higher standard than existing minimum requirements. Therefore, it is important to go beyond simple legal compliance. On the other hand, guidance can also be a barrier to effective SEA application, if it is outdated, and not reflecting good practice elements. It is therefore vital for guidance to be updated regularly.

Broadly speaking, SEA practitioners are conscious of limitations of existing guidance. If they are formulated to promote simple legal compliance, they constrain the ‘evolution’ of SEA (unless this evolution is promoted by the legislation itself). Furthermore, legal challenges and litigation are seen to be an important reason for increasingly inflexible approaches to SEA.

Whilst methods and procedures are key issues for guidance to focus on, there’s currently an unexplored universe related to the integration of SEA into the planning process and into a tiered PPP system. It seems to be consensual in the literature that, to be effective, this integration – which includes guidance development – has to rely upon particular aspects of the SEA system. Overall, though, SEA guidance needs to be approached as a dynamic element in any SEA system.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of Fapesp (Sao Paulo state Scientific Research Foundation) through grant # 2017/00095-2.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baresi U, Vella KJ, Sipe NG. 2017. Bridging the divide between theory and guidance in Strategic Environmental Assessment: a path for Italian regions. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 62:14–24.

- Brown AL, Therivel R. 2000. Principles to guide the development of strategic environmental assessment methodology. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 18(3):183–189.

- Caratti P, Dalkmann H, Jiliberto R. 2004. Analysing strategic environmental assessment: towards better decision-making. Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar.

- Chaker A, El-Fadl K, Chamas L, Hatjian B. 2006. A review of strategic environmental assessment in 12 selected countries. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:15–56.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:65–72.

- Craigie F, Snijman P, Fourie M. 2009. Dissecting environmental compliance and enforcement. In: Paterson AR, Kotzé LJ, Sachs A, editors. Environmental compliance and enforcement in South Africa. Cape Town: Juta. 51–58.

- De Montis A, Ledda A, Caschili S. 2016. Overcoming implementation barriers: A method for designing Strategic Environmental Assessment guidelines. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:78–87.

- Eppler MJ. 2006. A comparison between concept maps, mind maps, conceptual diagrams, and visual metaphors as complementary tools for knowledge construction and sharing. Inf Vis. 5:202–210.

- Fischer TB. 2003. Strategic Environmental Assessment in post-modern times. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23:155–170.

- Fischer TB. 2005. Having an impact? – context elements for effective SEA application in transport policy, plan and programme making. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 7(3):407–432.

- Fischer TB. 2006. Strategic Environmental Assessment and transport planning: towards a generic framework for evaluating practice and developing guidance. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 24(3):183–197.

- Fischer TB. 2007. Theory and practice of strategic environmental assessment: towards a more systematic approach. UK: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB. 2014. Impact assessment: there can be strength in diversity. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 32(1):9–10.

- Fischer TB, Gazzola P. 2006. SEA effectiveness criteria-equally valid in all countries? The case of Italy. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:396–409.

- Fischer TB, Gazzola P, Jha-Thakur U, Kidd S, Peel D. 2009. Learning through EC directive based SEA in spatial planning? Evidence from the Brunswick Region in Germany. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(6):421–428.

- Fischer TB, Seaton K. 2002. Strategic environmental assessment – effective planning instrument or lost concept? Planning Practice and Research. 17(1):31–44.

- Fischer TB, Welsch M, Jalal AI, Szkudlarek Ł, Bonilla M, Mwaura F, Haladyj A, Tomšić Ž, Athar GR 2018. Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for Nuclear Power Programmes – Guidelines, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna. [accessed 15 Nov 2018]. https://www-pub.iaea.org/books/IAEABooks/12251/Strategic-Environmental-Assessment-for-Nuclear-Power-Programmes-Guidelines.

- Fischer TB, Welsch M, Jalal I. 2019. Guidelines for Strategic Environmental Assessment of nuclear power programmes – preparation process, contents and consultation feedback. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 37(2).

- Fischer TB, Yu X. 2018. Sustainability appraisal in neighbourhood planning in England. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09640568.2018.1454304

- González JCT, de la Torre MCA, Milán PM. 2014. Present status of the implementation of Strategic Environmental Assessment in Mexico. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 16(2):1450021.

- Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell EL. 2013. Collecting qualitative data. A field manual for applied research. London: Sage Publications; p. 376.

- Gunn JH, Noble BF. 2009. A conceptual basis and methodological framework for regional Strategic Environmental Assessment (R-SEA). Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 27:258–270.

- Hildén M, Furman F, Kaljonen M. 2004. Views on planning and expectations of SEA: the case of transport planning. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 24:519–536.

- Hill M, Hupe P. 2002. Implementing public policy. London: Sage.

- Jones C, Baker M, Carter J, Jay S, Short M, Wood C, editors. 2005. Strategic environmental assessment and land use planning: an international evaluation. London: Earthscan.

- Kawulich BB. 2005. Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 6(2):Art. 43. May [accessed 2017 Aug 10]. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/466/996#g51.

- Kørnøv L, Thissen WAH. 2000. Rationality in decision- and policy-making: implications for strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 18:191–200.

- Malvestio AC, Fischer TB, Montaño M. 2018. The consideration of environmental and social issues in transport policy, plan and programme making in Brazil: a systems analysis. J Clean Prod. 179(1):674–689.

- Malvestio AC, Montaño M. 2013. Effectiveness of Strategic Environmental Assessment applied to renewable energy in Brazil. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 15:1340007.

- Marsden S. 1998. Importance of context in measuring effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 16:255–266.

- Montaño M, Opperman PA, Malvestio AC, Souza MP. 2014. Current state of the SEA system in Brazil: a comparative study. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 16:1450022.

- Nadruz VN, Gallardo ALCF, Montaño M, Ramos HR, Ruiz MS. 2018. Identifying the missing link between climate change policies and sectoral/regional planning supported by Strategic Environmental Assessment in emergent economies: lessons from Brazil. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews. 88:46–53.

- Nielsson MN, Dalkmann H. 2001. Decision making and strategic environmental assessment. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 3(3):305–328.

- Noble B, Nwanekezie K. 2016. Conceptualizing strategic environmental assessment: principles, approaches and research directions. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 62:165–173.

- Noble BF, Gunn JH, Martin J. 2012. Survey of current methods and guidance for Strategic Environmental Assessment. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 30(3):139–147.

- Partidario MR. 2000. Elements of an SEA framework - improving the added-value of SEA. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 20(6):647–663.

- Posas PJ. 2011. Exploring climate change criteria for strategic environmental assessments. Prog Plann. 75:109–154.

- Rega C, Baldizzone G. 2015. Public participation in Strategic Environmental Assessment: a practitioners’ perspective. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:105–115.

- Retief F. 2007. Effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) in South Africa. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management. 9(1):83–101.

- Richardson T. 2005. Environmental assessment and planning theory: four short stories about power, multiple rationality, and ethics. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 25(4):341–365.

- Schijf B. 2011. Developing SEA guidance. In: Sadler B, Aschemann R, Dusik J, Fischer TB, Partidario MR, Verheem R, editors. Handbook of Strategic Environmental Assessment. London: Earthscan; p. 487–500.

- Smith MC. 2018. Revisiting implementation theory: an interdisciplinary comparison between urban planning and healthcare implementation research. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. 36(5):877–896.

- Tague NR. 1995. Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle. The quality toolbox. 2nd ed. Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press; p. 390–392.

- Therivel R. 1993. Systems of strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 13:145–168.

- Therivel R. 2010. Strategic Environmental Assessment in action. 2nd ed. London: Earthscan.

- Therivel R, Caratti P, Partidário MR, Theodórsdóttir AH, Tyldesley D. 2004. Writing Strategic Environmental Assessment guidance. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 22(4):259–270.

- Tshibangu GM, Montaño M. 2016. Energy related Strategic Environmental Assessment applied by Multilateral Development Agencies — an analysis based on good practice criteria. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:27–37.

- Yee W-H, Tang S-Y, Lo CW-H. 2014. Regulatory compliance when the rule of law is weak: evidence from China’s environmental reform. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 26(1):95–112.