ABSTRACT

Despite the use of environmental and social impact assessments for road projects, severe social impacts continue to occur. We discuss the social impacts associated with the construction, upgrading, widening and/or rehabilitation of roads in Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to a literature review, we analysed 10 road projects in Uganda by examining project planning documents, and undertaking in-depth interviews, group interviews and field visits. While there were some benefits from these road projects, especially dust reduction where roads became sealed, the significant land acquisition necessary for these linear projects has led to physical displacement, economic displacement, and disruption to the livelihoods of local people. Other issues included: inadequate community engagement; delayed payment of compensation and inadequate compensation; gender-based violence; poor road construction practice causing community safety concerns; project-induced in-migration or influx; sexual harassment; impacts on children; and issues around sex work. The lack of local community acceptance (social licence to operate) of the projects resulted in construction delays and increased costs. For more acceptable road projects, better community engagement, improved planning and management, and adequate funding for resettlement and compensation are essential.

Introduction

The number and scale of road infrastructure projects have been increasing in many parts of the world due to national development objectives, population growth, and because of the benefits to be reaped from improved road systems (ADB Citation2008; Alamgir et al. Citation2017; Bice et al. Citation2019), as well as the perceived need to provide access to previously remote places (Povoroznyuk et al. Citation2023). This has partly been facilitated by increased access to financing and road construction firms made possible by the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2021b). Improving the adequacy of roads contributes significantly to national and regional economic growth, and to social benefits such as enhanced safety (reduced injury and deaths), improved connectivity and access to social services, reduced travel time and travel cost for road users, increased competitiveness of cities, increased attractiveness for investment, business development opportunities for local entrepreneurs, and improved quality of life (United Nations Citation2001; Robinson and Thagesen Citation2004; Gichaga Citation2017; Khanani et al. Citation2021; Muvawala et al. Citation2021; Ghosh and Dinda Citation2022; Stjernborg Citation2023). However, especially when poorly implemented, road projects and their associated facilities such as borrow-pits and workers’ camps can also have a wide range of inadvertent negative environmental and social impacts (Davis Citation1977; Findlay and Bourdages Citation2000; Walker et al. Citation2011; Tserendorj et al. Citation2013; Harvey and Knox Citation2015; Montgomery et al. Citation2015; Clements et al. Citation2018; Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2019; Vilela et al. Citation2020; Vijayakumar et al. Citation2023; Wan et al. Citation2024). New roads may lead to the displacement of people living along the intended route. The widening or upgrading of existing roads may affect roadside traders for the duration of work and sometimes permanently, in both cases greatly affecting their lives and livelihoods. Issues associated with the usually male-dominated workforce and project-induced in-migration or influx are also significant risks for local communities (Tserendorj et al. Citation2013; World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2020; Gerrits Citation2024).

The lack of proper planning, implementation and management of road and other projects causes conflict with communities, delays to project completion, increases the cost of projects, creates road safety concerns, and causes social and environmental problems that may be irremediable (United Nations Citation2011; Hanna et al. Citation2016; Alamgir et al. Citation2017; Esteves et al. Citation2017; Vanclay and Hanna Citation2019; World Bank Citation2019a, Citation2019b 2019c). Land is an important element in road construction, and before road projects can commence, a right-of-way must be legitimately obtained, free of encumbrances and occupants. Land acquisition for roads and other projects is a major source of concern for local communities (North Citation1998; Vanclay Citation2017; Sedegah et al. Citation2023). The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to discuss, in a Sub-Saharan Africa context, the social issues that emerge from the design and construction of road projects. Our research is based on an analysis of 10 major road projects in Uganda, in-depth interviews with experts, group discussions with affected people, and a literature review about the social impacts from road projects, as well as on our extensive project experience.

Road infrastructure in Uganda

With an area of 241,000 km2 (about the size of the United Kingdom) and a population of 47 million people, Uganda is a rapidly developing Sub-Saharan African country. Many road projects, totalling thousands of kilometres, have been implemented in Uganda in recent decades to improve the connectivity and effectiveness of the road transport system. With no established railways, roads are the dominant mode of transport in Uganda, carrying virtually all freight and passenger traffic (NPA Citation2020; UNRA Citation2021). In the government’s Vision 2040 plan (NPA Citation2013), various targets were established, including an ‘average paved road density’ of 100 km per 1000 km2. This compares to less than 1 km per 1000 km2 in 2013 when the Vision 2040 targets were set, and to an expected 29.3 km per 1000 km2 in 2023 (NPA Citation2020).

There are different ways of comparing countries on the extent of development of their road system. Sometimes, the unit of measurement is kilometres of paved road per million inhabitants, other times it is kilometres per 1000 km2 of land area. Either way, Uganda is severely under-serviced. A World Bank report (Queiroz and Gautam Citation1992) revealed that paved roads varied from 170 km per million inhabitants in low-income countries, to 1,660 in middle-income countries, and 10,110 in high-income countries. Although this source is dated, the huge disparity between rich and poor countries continues to exist.

When Uganda gained independence in 1962, it only had a total of 844 km of paved roads (UNRA Citation2021). When Museveni became President in 1986, there was about 1,000 km of paved roads, mostly in very poor condition (Museveni Citation2021). In 2007, there were 2,651 km of paved roads and a total road network of 9,800 km. By 2020, there were 5,370 km of paved roads, being 26 percent of the total road network of 21,010 km (UNRA Citation2020). Dual carriage roadways (divided roads) increased from only 16 km in 1986 to over 80 km in 2018 (NPA Citation2020). By comparison, in 2022, Great Britain had a total road network of about 395,000 km (245,100 miles), nearly all of which was paved (UKDoT Citation2023).

The National Development Plan (NPA Citation2020) outlined a number of strategies for development including: fast-tracking oil, gas and mineral-based industrialization; promoting tourism; and improving transport infrastructure. The targets set for paved roads were 7,500 km by 2025; and 119,840 km (80% of total roads) by 2040 (NPA Citation2020). Generally proclaimed with much ballyhoo (Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2021b), road projects are usually expected to deliver public benefits, with harm being managed by undertaking (and hopefully implementing) environmental and social impact assessments (ESIAs) and resettlement action plans (RAPs). However, as happens around the world (Legacy Citation2017; Lee et al. Citation2020; Mottee et al. Citation2020), the political nature of the push for projects and their use to secure ongoing mandates for political elites mean that advocated projects do not necessarily achieve desired social outcomes (Muhoza et al. Citation2023). Transparency, accountability, monitoring & evaluation, and ESIA follow-up are done poorly, may be inaccurate or misleading (Jalava et al. Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2020; Mottee et al. Citation2020; Kahangirwe and Vanclay Citation2022), and are often corrupted (Anassi Citation2004; Oluseye Citation2024).

Ensuring the success of road projects requires that the government and project managers better identify and address all social risks associated with road development and to monitor the efficacy of any mitigation measures that might be implemented (Kahangirwe and Vanclay Citation2022). Of significance is that public interest and criticism of projects often increases over time as society becomes more empowered and more involved in project development through ESIA community engagement and by increasing democracy in society generally (Esteves et al. Citation2012). This means that local people now have higher expectations of projects and can be more demanding of good process and fair outcomes (Vanclay and Hanna Citation2019). Social impact assessment (SIA) can be used to assist in ensuring the fair and equitable distribution of project benefits, and in the avoidance and effective management of negative social impacts and human rights harms (Esteves et al. Citation2012, Citation2017; Vanclay et al. Citation2015).

Major road projects typically have a lengthy implementation timeframe (often 5 to 10 years) and significantly influence the local economy and accessibility of the location (Fan and Chan-Kang Citation2005; Lee et al. Citation2020). Consequently, many things that potentially impact local people and communities should be carefully considered in the planning of road projects, including: displacement of people; impacts on livelihoods; destruction of houses and other structures; adequate compensation; the splintering of communities; and project-induced in-migration (Tsunokawa and Hoban Citation1997; United Nations Citation2001; Stolp et al. Citation2002; Vanclay Citation2002, Citation2017, Citation2024; Montgomery et al. Citation2015; Smyth and Vanclay Citation2017; World Bank Citation2019a; Lucas et al. Citation2022; Gerrits Citation2024).

Methodology

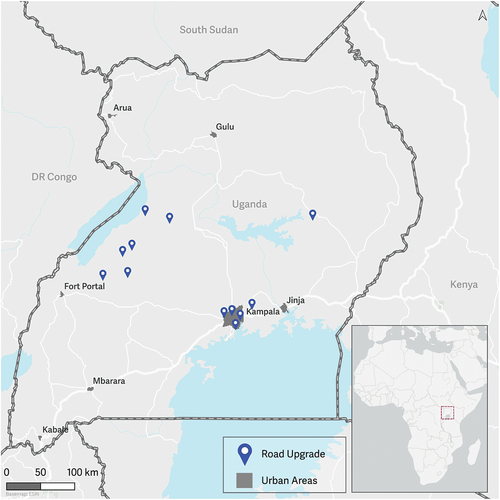

We identify and discuss the key social issues that emerge in the planning and implementation of road projects in a Sub-Saharan Africa context. In addition to a literature review and in-depth interviews with experts, we examined 10 major road projects in Uganda (see ), including undertaking group discussions with people affected by those projects. gives a general indication of where these projects were located. The projects were selected from the Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Project Status Reports of June 2022 (UNRA Citation2022) and March 2023 (UNRA Citation2023). Although the Project Status Reports vary over time and include small as well as large projects, usually they list around 20 active road projects at any one time. The criteria used to select the projects included that: they were externally financed and therefore arguably subject to international standards, including having an ESIA done in advance; they were likely to cause significant social impacts because of proximity to built-up areas; and they were accessible to the lead author for field observation and to interview affected people. The selection was purposive, and comprises an indicative set of the major road projects in Uganda, and are also likely to be representative of road projects across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 1. Approximate location the ten road projects examined for this research.

Table 1. Summary of ten road projects examined for this research.

Data collection was undertaken between February 2022 and June 2023. A range of methods was used, including: field observations of the 10 road projects; a document analysis of key documents relating to national road planning and the specific projects, including the ESIA and RAP reports for each project (where available); 60 in-depth interviews with experts; 10 interviews done using Google Forms; and 34 group discussions involving a total of about 300 project-affected people.

The 60 in-depth interviews were conducted by the lead author, and included ESIA or resettlement consultants, contractors, UNRA staff, local government authority staff, regulators, and five academics. Most interviewees spoke about road projects generally rather than specifically about the projects we examined. The lead author also conducted 34 group interviews involving about 300 project-affected people. These were relatively impromptu and primarily involved kiosk or stall holders along the route of each project. Most were women of working age. Most interviews (indepth and group) were done in English (the official language of Uganda), although some discussions were in the local languages, Luganda or Runyankore (which are spoken by the lead author). The principles of ethical social research (Vanclay et al. Citation2013) were observed, although, as most people in Uganda are averse to signing official forms, informed consent was verbally obtained before proceeding with any interview.

During the in-depth interviews, which generally took between 30 and 60 minutes, the lead author established rapport with the expert interviewees and made them feel comfortable, which helped generate forthright and insightful responses, especially regarding sensitive topics related to compensation, livelihood disruption, and other important issues. Consequently, the lead author was able to ask follow-up questions, probe for additional information, and circle back to key issues to gain a deep understanding of the interviewee’s attitudes, perceptions, motivations, and the issues being discussed. An interview guide was used, having the following questions:

What is your role in the road infrastructure development sector?

What are the social benefits provided by road infrastructure developments?

What are the key social risks and challenges experienced during planning, construction and rehabilitation of the road infrastructure in Uganda?

What are the causes of those social risks/challenges?

Are the social risks and challenges managed appropriately?

How are these social risks managed while initiating and implementing road projects?

What mitigation strategies could be adopted while initiating road projects to reduce harm to communities?

For various reasons (primarily their busyness), 10 people requested to complete a survey rather than an in-person interview, and therefore an online survey was established using Google Forms. This survey was substantially similar to the interviews in terms of the questions asked, but the online answers were less detailed than the answers given in the face-to-face in-depth interviews, and no probing was possible.

The group interviews with project-affected people generally lasted around 20 minutes each, although given their impromptu in situ nature, participants tended to stay for as long as they maintained interest, which meant that there were some comings and goings. For the in-depth and group interviews, the lead author/interviewer took notes of the responses to each question in a paper notebook and sometimes on his laptop computer. Key points from these notes were later transferred into a Word document.

In addition to the primary data collection, a targeted literature review was undertaken of documents addressing the social impacts of road projects, especially in a Sub-Saharan context. Searching was done via Scopus, Google Scholar and Google, and by following-up on any leads we received. It should be noted that this specific topic, the social impacts of roads, does not have a large literature base, and consequently, to make our paper an ongoing resource for this topic, we have cited most of the key publications we discovered.

Benefits associated with road improvement

Road projects can provide many benefits for communities, especially increased access to facilities (Robinson and Thagesen Citation2004; Vanclay Citation2024). For example, a World Bank report stated that improvement of roads in a mountainous area of India increased access to health clinics, which significantly improved maternal health and reduced infant mortality because there was a reduction in the number of births without medical support in small villages (Herrera Dappe et al. Citation2021). Road upgrading and rehabilitation reduces deaths and injuries from accidents (Gichaga Citation2017), and has various health benefits, most-notably reduced dust and thus less respiratory infections and eye infections (Greening Citation2011; Khan and Strand Citation2018). The 10 road projects in Uganda will likely have long-term social, economic and health benefits for local people and the region. Drawing on the ESIA reports and our primary data, the projects were likely to provide the following short and long-term benefits:

A safer, cleaner, and healthier living environment, with reduced dust and noise.

Improved access to social services.

Short-term job opportunities for subcontractors and local people.

Supply of equipment and materials by local suppliers.

Increased business for local retailers during construction (to workers) and beyond (to people who now have improved access to these retail outlets).

Rental income during construction from providing land for the contractors’ requirements, as well as accommodation for workers.

Increase in property values.

Because of perceived increased land value, local residents might be motivated to improve their houses and/or commercial premises to obtain higher returns.

Private investors might be attracted to invest in the area, leading to improved services and facilities.

Increased prosperity benefits town councils and districts through increased rate revenue.

Increased income for farmers by having an expanded consumer base to buy their product.

Increased activity in local markets, benefiting all traders.

It is important to realize that these alleged benefits are not equally distributed within a community, and may be mixed blessings. They are likely to cause local inflation and gentrification, which is likely to lead to increasing inequality (Vanclay Citation2002). Also, increased traffic created by the roads might negate some of the effects from their improvement. There is also the question of the opportunity cost: could the funds have achieved better social development outcomes if invested in a different way?

Negative social impacts associated with road improvement

Roads and road construction are known to have many negative social impacts. In some contexts, issues like the volume of traffic, safety, noise and vibration, transport justice, health impacts from emissions, aesthetic impacts on the landscape, the splintering of communities, and disruption and inconvenience during construction tend to be the primary issues of concern (Stolp et al. Citation2002; Geurs et al. Citation2009; Anciaes et al. Citation2017). In Sub-Saharan Africa, the primary social concerns from road projects are generally related to land acquisition, displacement and resettlement, impacts on people’s livelihoods, the adequacy of compensation, disruption to people’s lives, and inequality in the distribution of benefits (Jayawardena Citation2011; Chamseddine and Boubkr Citation2020; Khanani, Citation2021). Issues can also arise from: a failure to undertake adequate community engagement; a failure to accord Indigenous peoples with free, prior and informed consent; the fact that roads facilitate the in-migration of people (not all of whom will necessarily be consistent with the local culture and social fabric); and that the development of roads may hasten the onslaught of progress and the loss of traditional ways of living (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2024).

The social impacts during the undertaking of road works can be very serious. For example, in December 2014 and in September 2015, some local communities in Uganda complained about the social impacts from the upgrading of the 66 km Kamwenge-Fort Portal road, which was being funded by the World Bank. They claimed there was a ‘lack of participation, inadequate road and workplace health and safety measures, poor labor practices, inadequate compensation, fear of retaliation, sex with minors and teenage pregnancies by road workers, increased sex work, sexual harassment of female employees, the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), child labor, and school dropouts’ (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2016, p. 1). These concerns were investigated by the World Bank Inspection Panel, and were corroborated. Consequently, the World Bank decided to cease funding the project, which led to a lot of publicity about the case within Uganda and internationally.

In 2017, the World Bank received a somewhat similar complaint about a road project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which also drew attention to the effectiveness of the World Bank’s monitoring of project funding.

The Request for Inspection alleged loss of property, loss of livelihoods, use of violence against the community – including gender-based violence (GBV), and seizure of indigenous communities’ resources as a result of the Project’s implementation. Specifically, it alleged the Congolese Armed Forces (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo or FARDC), engaged by the Project’s Contractor to provide security, have occupied a quarry that is operated by the Requesters and is their source of income and livelihood. The Requesters also claimed there has been violence against the community and sexual violence against women during Project implementation. They further contended that the Contractor employed young boys as daily laborers and confiscated a portion of the workers’ salaries. (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2018, p. viii)

The Uganda and DRC Inspection Panel investigations led to much change within the World Bank, specifically to ensure that effective, operating, project-level grievance redress mechanisms were in place, and to better monitoring of funded projects. Also, much guidance about how to address gender-based violence in projects was produced (World Bank Citation2017, Citation2019a; World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2020).

Drawing on the findings of the Inspection Panel Reports of the Uganda (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2016) and DRC (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2018) cases, an ‘Emerging Lessons’ guidance document based on these cases (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2020), other literature, and the evidence we collected from the 10 projects we examined in Uganda, below we discuss the key social issues that arise in road projects in a Sub-Saharan context.

Physical displacement and involuntary resettlement

Road construction, widening and upgrading projects usually require additional landtake and/or the clearing of land in existing road reserves (right-of-ways). However, over time, the roadsides and undeveloped road reserves often become utilized by local people for various activities (ADB Citation2008). Thus, land acquisition for the road projects generally requires demolishing (or relocating) existing structures, sometimes including people’s houses.

In Uganda, families often have been settled in one location for generations. Home and sense of place is fundamental to people’s wellbeing, and anything that affects the home and/or where they live is likely to create significant social impacts (Smyth and Vanclay Citation2017, Citation2024). Some individuals may have strong ancestral ties to their land, and deceased relatives may be buried on the property or nearby. Most people consider the prospect of exhuming and relocating graves to be unacceptable, but having them paved over by a road could be even worse. In any event, the whole process of having to leave their home and land is very traumatic (Vanclay Citation2017).

Given that the road authority decides on the routing and design of the road, landowners have little say over what land is taken and whether they need to be resettled. Because the land is usually expropriated (rather than acquired through a ‘willing buyer, willing seller’ agreement), affected people generally feel they are forced to move against their will. Unlike projects in other sectors that, consistent with international standards, provide replacement housing that is better than what people had before and/or provide compensation at full replacement value, road projects in Uganda typically only provide compensation at well below replacement value, requiring affected people to make their own alternative living arrangements and meet any shortfall. This creates considerable stress and burden on displaced people.

Economic displacement and livelihood impacts

In addition to the removal of houses, road projects generally require demolition of other structures, including roadside stalls. To continue their livelihood activities, the owners of these structures may have to find alternative locations to conduct their business, which affects their financial and mental wellbeing in the short-term. According to international standards, these people should be compensated for lost income and inconvenience, and not just for the loss of any structures (Vanclay Citation2017; IFC Citation2023; Smyth and Vanclay Citation2024).

Even where stalls might not have to be demolished, access to them may be restricted during construction. In the projects we examined, shopkeepers affected by roadworks often had limited access to their stalls for many months because the contractors would dig trenches along the road, which might remain exposed for months, severely impairing access to the stalls (see ). Sometimes, sections of the road might be blocked-off to all traffic and pedestrians, completely restricting access for customers. Contractors generally paid little attention to the impacts of their activities on the lives and livelihoods of local people.

Squatters, encroachers and rightful users of road reserves

In some countries, an undeveloped road reserve could be an encumbrance over privately-owned land, while in other places, including Uganda, land cannot be declared a road reserve without it becoming publicly-owned land managed by the roads authority (Uganda Citation2019). Consequently, Uganda has many road reserves that have remained undeveloped for decades. Sometimes, these road reserves are leased to people for various purposes, with the leasees having some responsibility for land management and the right to use the land for approved purposes. Typically, however, undeveloped road reserves are left vacant and unsupervised, and are prone to attracting ‘squatters’ (people who seek to live there in informal housing) and ‘encroachers’ (people who seek to use the land for various purposes other than housing, typically growing crops, without having a legal right to do so) (Vanclay Citation2017; IFC Citation2023).

In Uganda, an occupier of land (squatter) may gain legal rights over that land if they have remained on it for 12 years or more without challenge by the owner (Uganda Citation1998). Since UNRA and local authorities do not have the resources to monitor all underdeveloped road reserves, there are many people who potentially are able to claim ownership over land in road reserves. This is problematic and disruptive for road projects because the appointment of contractors to implement the project is usually on the basis or assumption that there are no encumbrances or unsettled land ownership claims. Although the existence of potential claimants, squatters and encroachers should be identified in the project’s ESIA and RAP, social baselines are often inadequately done and so these phenomena are often understated. Also, delays between when the ESIA and RAP are done and appointment of the contractor can enable new instances of squatting and encroachment. Sometimes, the ESIA and RAP might not be completed before the road contractor is appointed. With potentially more landowners than was previously considered, projects can be delayed while the validity of land claims is determined. Also, more landowners means that additional compensation funding will be required, which usually has not been budgeted for. Furthermore, under international standards, squatters and encroachers should be compensated for lost assets, requiring additional funding. Since this extra funding is not easily provided by the Finance Ministry, the payment of compensation and project completion are often delayed.

Inadequate compensation, delays, and poor process

In Uganda, the valuation of property is done according to government guidelines (MLHUD Citation2017) and valuers must follow the set method to establish compensation entitlement. Landowners have no say in the compensation they receive and must accept the amount determined from the schedule, which is often years old. The group interviews revealed that compensation amounts were not adequate to purchase replacement land and that people were made worse-off. Also, the compensation did not include any allowance for inconvenience, disruption or disturbance (solatium, or pain and suffering). The inadequacy of compensation severely affected people’s wellbeing and mental health.

Most affected people were anxious about the content and implementation of the RAP reports. Fears included that tree and crop counts in the valuation report might vary from their understanding, and that the assessed compensation was inconsistent with their entitlement or with what they thought they should receive. These fears arose partly because of the failure of project proponents to provide the RAP report (and land acquisition maps) at accessible local locations so that affected people could verify the recorded information.

Somewhat inconsistent with international resettlement practice, in Uganda, people being compensated usually have to demolish all buildings, walls, and gardens and remove all materials and debris themselves (although this is partly to enable them to salvage materials for resale or to re-use elsewhere). Some people dutifully demolished their buildings early in the process, while others continued to use their structures and land up to the last minute. This inequality created tensions in the community, with the people who demolished their buildings early often feeling cheated.

Compensation was typically not paid in a reasonable timeframe. This occurred for several reasons, including unresolved disputes amongst property owners, lack of required documentation (such as proof of ownership), unresolved court cases relating to land ownership or about the level of compensation, and insufficient funding for the project, meaning that the authorities simply do not have the funds to pay the compensation that is due. Sometimes, usually for dubious purposes, politicians have attempted to interfere in the process, e.g. by encouraging local people to demand more compensation. Although arguably this might sometimes increase the ultimate amount of compensation paid, it leads to delays in project development and in the payment of compensation. Delays in the payment of compensation, and delays in project completion, cause significant hardship and impacts on people’s livelihoods and wellbeing.

There can be considerable delay between when people are asked to demolish their buildings and when roadwork actually starts. During field inspections for this research, the lead author observed that construction for some roads was still unfinished, even though buildings had been required to be demolished two years earlier. When people consider that they have had to vacate their land much earlier than necessary, they feel resentful. The delay can also lead to new incidents of squatting and encroachment.

The payment of compensation relies on the availability of funds to UNRA from the Finance Ministry, which are dispersed to affected people via a consultant. Often, the available funding is far less than the amount of compensation that is due. This results in delayed payment, and sometimes in non-payment. It also leads to distress and division amongst affected people, with some wondering why it was that certain people received early payment while others experience delayed payment or are not paid at all. These issues delay project commencement and completion, especially when people become agitated and blockade access to sites or machinery (Hanna et al. Citation2016; Kilajian and Chareonsudjai Citation2021).

During the group interviews, affected people complained about orphaned land not being compensated (i.e. land that becomes inaccessible or unusable because of the project). They stated that the Livelihood Restoration Plan and Community Development Plan were not adequately disseminated, and that there was little engagement with local communities in the development of those plans. Finally, although grievance mechanisms had been established, they were not effective and not trusted.

Issues with the ‘cut-off date’

The cut-off date is a key concept in project land acquisition (Vanclay Citation2017; IFC Citation2023). It is the date communicated to affected people announcing that they should desist from any further development or investment in their land and houses, for example renovations or planting trees and crops. The cut-off date mechanism enables the project proponent to not have to compensate affected people for any investment in their property made after this date. This legal mechanism is arguably reasonable when compensation and resettlement happens quickly after the announced date, and when the date is adequately notified, but extended delays to a project or to the payment of compensation after the announced cut-off date can create severe social impacts and could be a human rights issue, especially when land-based people have nothing to eat because crops were not planted (Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2021a).

In several group interviews, people stated that they were uncertain whether they should establish new kiosks, other structures, and/or plant crops. It was stated that (slightly modified):

sometimes when we want to plant crops, we are told that we are not allowed to do this because the authorities have already identified where the road will go, but we have not yet been compensated, even though we are already restricted in our usage of that land, thus affecting our livelihoods … this is not fair!

Disruption to people’s lives and other sources of nuisance and annoyance

It was reported that road construction activities disrupted traffic flow and impeded access to social amenities, e.g. schools, health services, markets, worship places and roadside businesses, sometimes for months. This disrupted the economic and social life in the community and caused stress and resentment. A UNRA official revealed that equipment may be ready for use on site before the compensation to affected individuals has been established, and that this was problematic because the presence of the equipment clearly indicated to local people that the project was going ahead regardless and that their views were inconsequential. Thus, the equipment was a visible omen – hanging like a dark cloud on the horizon – that annoyed and aggravated local people, who in frustration may sabotage or block access to prevent use of this equipment, resulting in delayed commencement of work and increased costs due to idle machinery, operators and workers.

Triggering of conflict and gender-based violence within families

The way compensation is disbursed, the inadequacy of the compensation, and the disruption and stress created by the project leads to conflict within many families, sometimes resulting in gender-based violence and family breakdown. Participants in the group interviews mentioned that the compensation gives some men the idea they are rich, leading them to spend money unwisely, including on extra-marital sexual activity. Some men take on extra wives. This behaviour leads to family conflict, relationship break-ups, and sometimes to physical violence (on both sides). In some cases, men completely abandoned their families resulting in an increased number of single mothers. People in our group interviews indicated that some men abused their wives because they feel they can have any woman they want.

Impacts from the influx of workers

Major road construction projects typically generate an influx of migrant workers, sometimes for years. This project-induced in-migration has many social consequences and needs to be managed carefully (Gerrits Citation2024). Construction workers are ‘mobile men with money’, and generally engage in behaviours that increase the spread of HIV/AIDS and other sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) in local communities (Tserendorj et al. Citation2013; Kuteesa Citation2014; World Bank Citation2019c). The spread of STIs, especially HIV/AIDS, increases pressure on local health systems, and has major social impacts in local communities.

The group discussions and expert interviews revealed local concern about possible use of child labour, which reduced community support for some projects. Regardless of whether children were being directly employed by the primary contractor or not, the relative wealth of project workers and the possibility that they were giving treats to children or befriending them was a possible incentive for children to skip school. Potentially, families in poverty may encourage children to beg or otherwise solicit gifts.

In several in-depth interviews, the issues around the Kamwenge to Fort Portal road were mentioned, including that there had been ‘many cases of child sexual abuse and teenage pregnancies by road workers’ (World Bank Inspection Panel Citation2016, p. ix). Although actual evidence of such misconduct in the projects we examined was limited, the general view of our research participants was that sexual activity by workers with local women was occurring and that this likely included under-aged females.

Children suffer many complications from under-age sexual activity that can last their whole life, including contracting various diseases, child pregnancy, parental abandonment, dropping out of school, and the implications of this for their life chances (Kuteesa Citation2014; Tanzarn Citation2017; World Bank Citation2019a). It is very important that projects, and all actors associated with them, take all reasonable steps to ensure that child sexual abuse does not occur.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to identify the key social issues that emerged when road projects are planned and executed. We found that road projects in Uganda and Sub-Saharan Africa are likely to cause physical displacement, economic displacement and livelihood disruption. Land acquisition processes were lengthy and delays often occurred. There were issues with project-induced in-migration and migrant labourers. To be consistent with international standards, project developers, implementers and sponsors must avoid and minimize the need for resettlement. There must be meaningful engagement with affected people and communities, adequate compensation at full replacement cost that is paid in a timely way, and effective livelihood improvement programs (Vanclay Citation2017; IFC Citation2023; Smyth and Vanclay Citation2024). People should be made better-off by projects, and certainly not be made worse-off (Gulakov and Vanclay Citation2024).

The local authorities and project-affected people we interviewed revealed that road projects often required much more land than was originally expected. This was problematic in many ways, including that additional compensation funding would be needed, but was often not available. Most project-affected people indicated they were sceptical about whether they would receive fair and timely compensation. Some revealed that, to obtain more compensation, they often engaged in opportunistic practices (such as construction of temporary buildings or planting of trees and crops). They stated that they had learned this from politicians and government officials who, because of their inside knowledge, often indulged in land speculation and other dubious dealings. Opportunistic and speculative behaviour remains a major problem for projects that require land acquisition (Vanclay Citation2017; IFC Citation2023; Smyth and Vanclay Citation2024), but often occurs because local people feel a sense of unfairness and injustice, especially because of inadequate compensation, and delays in the payment of compensation. Curiously, problems with the payment of compensation are partly related to the procedures of the World Bank and most IFIs, which tend to only cover the cost of the infrastructure development but not the cost of resettlement in their project financing. We would argue that all costs associated with physical and economic displacement and compensation for livelihood disruption should be seen as part of the overall project cost and be included in the financing arrangements. Excluding this critical element from the financing arrangement is a social risk and a project risk. In any event, to be consistent with international standards, the lender must check that the borrower has sufficient funds available to cover the full costs of implementing the project (including all physical and economic displacement). Not to do so would make the lender complicit in human rights harms.

Monitoring & evaluation are weak or missing elements in ESIA and RAP implementation generally (Jalava et al. Citation2015). Although these actions would provide opportunities to learn about the actual consequences of projects, this has not often happened. In Uganda, social impacts were rarely monitored, although traffic noise has been given special attention. Community participation has occurred, to some extent at least, but only in the early stages of the ESIA and RAP preparation processes. Clearly, community engagement processes need to be much improved.

The land acquisition process should be refocussed so that it creates inclusive and resilient communities, while also supporting the most vulnerable and marginalized people (FAO Citation2022). All elements of social impact assessment are essential, but some aspects are especially important: grievance redress mechanisms; consideration of gender; prevention of gender-based violence; and protection of vulnerable groups including but not limited to child headed households, the elderly, and orphans. Communities must be provided with adequate information and opportunities to make informed decisions about the planned infrastructure projects that impact their lives and livelihoods.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alamgir M, Campbell M, Sloan S, Goosem M, Clements G, Mahmoud M, Laurance W. 2017. Economic, socio-political and environmental risks of road development in the tropics. Curr Biol. 27(20):R1130–R1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.067.

- Anassi P. 2004. Corruption in Africa: The Kenyan Experience. Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford.

- Anciaes P, Metcalfe P, Heywood C. 2017. Social impacts of road traffic: perceptions and priorities of local residents. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 35(2):172–183. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2016.1269464.

- Asian Development Bank. 2008. Healthy Together, Our Future: Guidebook for HIV/AIDS/STI Prevention in the context of Mining and Transport. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/33483/social-analysis-transport-projects_0.pdf.

- Bice S, Neely K, Einfeld C. 2019. Next generation engagement: setting a research agenda for community engagement in Australia’s infrastructure sector. Australian J Public Adm. 78:290–310. doi: 10.1111/1467-8500.12381.

- Chamseddine Z, Boubkr A. 2020. Exploring the place of social impacts in urban transport planning: the case of Casablanca city. Urban Plann Transp Res. 8(1):138–157. doi: 10.1080/21650020.2020.1752793.

- Clements G, Aziz S, Bulan R, Giam X, Bentrupperbaumer J, Goosem M, Laurance S, Laurance W. 2018. Not everyone wants roads: assessing indigenous people’s support for roads in a globally important tiger conservation landscape. Hum Ecol. 46(6):909–915. doi: 10.1007/s10745-018-0029-4.

- Davis S. 1977. Victims of the miracle: development and the Indians of Brazil. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Esteves AM, Factor G, Vanclay F, Götzmann N, Moreiro S. 2017. Adapting social impact assessment to address a project’s human rights impacts and risks. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 67:73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2017.07.001.

- Esteves AM, Franks D, Vanclay F. 2012. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):34–42. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2012.660356.

- Fan S, Chan-Kang C. 2005. Road development, economic growth, and poverty reduction in China. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/80777/filename/80778.pdf.

- Findlay C, Bourdages J. 2000. Response time of wetland biodiversity to road construction on adjacent lands. Conserv Biol. 14(1):86–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99086.x.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2022. Voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests in the context of national food security (rev edn). Rome. 10.4060/i2801e.

- Gerrits R. 2024. Managing influx: project-induced in-migration. In: Vanclay F Esteves AM, editors. Handbook of social impact assessment and management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; p. 412–425.

- Geurs K, Boon W, van Wee B. 2009. Social impacts of transport: literature review and the state of the practice of transport appraisal in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Transp Rev. 29(1):69–90. doi: 10.1080/01441640802130490.

- Ghosh P, Dinda S. 2022. Revisited the relationship between economic growth and transport infrastructure in India: an empirical study. The Indian Econ J. 70(1):34–52. doi: 10.1177/00194662211063535.

- Gichaga F. 2017. The impact of road improvements on road safety and related characteristics. IATSS Res. 40(2):72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.iatssr.2016.05.002.

- Greening T. 2011. Quantifying the impacts of vehicle-generated dust. Washington (DC): Word Bank. 10.1596/27891.

- Gulakov I, Vanclay F. 2024. Continuing to put people first: embedding community investment in the sustainability standards of international financial institutions. Sustain Devel. doi: 10.1002/sd.3003.

- Hanna P, Vanclay F, Langdon EJ, Arts J. 2016. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest action to large projects. Extractive Industries Soc. 3(1):217–239. doi: 10.1016/j.exis.2015.10.006.

- Harvey P, Knox H. 2015. Roads: an anthropology of infrastructure and expertise. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press.

- Herrera Dappe M, Alam M, Andres L. 2021. The road to opportunities in rural India: the economic and social impacts of PMGSY. Washington (DC): Word Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8e21abab-d9a1-5a4f-812c-cce37defab35/content.

- [IFC] International Finance Corporation. 2023. Good practice handbook: land acquisition and involuntary resettlement. International Finance Corporation. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2023/ifc-handbook-for-land-acquisition-and-involuntary-resettlement.pdf.

- Jalava K, Haakana A-M, Kuitunen M. 2015. The rationale for and practice of EIA follow-up: an analysis of Finnish road projects. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 33(4):255–264. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2015.1069997.

- Jayawardena S. 2011. Right of way: a journey of resettlement. Colombo: Centre for Poverty Analysis. https://www.cepa.lk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Right-of-Way-English.pdf.

- Kahangirwe P, Vanclay F. 2022. Evaluating the effectiveness of a national environmental and social impact assessment system: lessons from Uganda. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 40(1):75–87. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2021.1991202.

- Khan R, Strand R. 2018. Road dust and its effect on human health: a literature review. Epidemiol Health. 40:e2018013. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2018013.

- Khanani R, Adugbila E, Martinez J, Pfeffer K. 2021. The impact of road infrastructure development projects on local communities in peri urban areas: the case of Kisumu, Kenya and Accra Ghana. Int J Community Well-Being. 4(1):33–53. doi: 10.1007/s42413-020-00077-4.

- Kilajian A, Chareonsudjai P. 2021. Conflict resolution and community engagement in post-audit EIA environmental management: lessons learned from a mining community in Thailand. Environ Challenges. 5:100253. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2021.100253.

- Kuteesa A. 2014. Local communities and oil discoveries: a study in Uganda’s Albertine Graben Region. Washington (DC): Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2014/02/25/local-communities-and-oil-discoveries-a-study-inugandas-albertine-graben-region/.

- Lee J, Arts J, Vanclay F, Ward J. 2020. Examining the social outcomes from urban transport infrastructure: long-term consequences of spatial changes and varied interests at multiple levels. Sustainability. 12(15):5907. doi: 10.3390/su12155907.

- Legacy C. 2017. Infrastructure planning: in a state of panic? Urban Policy Res. 35(1):61–73. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2016.1235033.

- Lucas K, Philips I, Verlinghieri E. 2022. A mixed methods approach to the social assessment of transport infrastructure projects. Transportation. 49(1):271–291. doi: 10.1007/s11116-021-10176-6.

- MLHUD. 2017. Guidelines for compensation assessment under land acquisition. Uganda Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development; https://mlhud.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Guidelines-for-Compensation-Assessment-under-Land-Acquisition.pdf.

- Montgomery R, Schirmer H, Hirsch A. 2015. Improving environmental sustainability in road projects. Washington (DC): World Bank; https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/220111468272038921/pdf/939030REVISED0Env0Sust0Roads0web.pdf.

- Mottee L, Arts J, Vanclay F, Miller F, Howitt R. 2020. Metro infrastructure planning in Amsterdam: how are social issues managed in the absence of environmental and social impact assessment? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(4):320–335. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2020.1741918.

- Muhoza C, Kløcker Larsen R, Diaz-Chavez R. 2023. Equity on the road in Uganda: how do interface bureaucrats integrate marginalized groups in the transport sector? J Transp Geogr. 113:103738. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2023.103738.

- Museveni. 2021. Achievements. Yoweri Museveni President. https://www.yowerikmuseveni.com/achievements.

- Muvawala J, Sebukeera H, Ssebulime K. 2021. Socio-economic impacts of transport infrastructure investment in Uganda: insight from frontloading expenditure on Uganda’s urban roads and highways. J Transp Geogr. 88:100971. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100971.

- North P. 1998. ‘Save our Solsbury!’: the anatomy of an anti‐roads protest. Environ Polit. 7(3):1–25. doi: 10.1080/09644019808414406.

- [NPA] National Planning Authority. 2013. Uganda vision 2040. Uganda National Planning Authority. http://www.npa.go.ug/uganda-vision-2040/.

- [NPA] National Planning Authority. 2020. Uganda third national development plan 2020–25. Uganda National Planning Authority. http://www.npa.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NDPIII-Finale_Compressed.pdf.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F. 2019. Social impacts of land acquisition for oil and gas development in Uganda. Land. 8(7):109. doi: 10.3390/land8070109.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F. 2021a. Cut-off and forgotten?: livelihood disruption, social impacts and food insecurity arising from the east African crude oil pipeline. Energy Res Soc Sci. 74:101970. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.101970.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F. 2021b. Resource financed infrastructure: thoughts on four Chinese-financed projects in Uganda. Sustainability. 13(6):3259. doi: 10.3390/su13063259.

- Oluseye O. 2024. Exploring potential political corruption in large-scale infrastructure projects in Nigeria. Project Leadersh Soc. 5:100108. doi: 10.1016/j.plas.2023.100108.

- Povoroznyuk O, Vincent W, Schweitzer P, Laptander R, Bennett M, Calmels F, Sergeev D, Arp C, Forbes B, Roy-Léveillée P, et al. 2023. Arctic roads and railways: social and environmental consequences of transport infrastructure in the circumpolar North. Arct Sci. 9(2):297–330. doi: 10.1139/as-2021-0033.

- Queiroz C, Gautam S. 1992. Road infrastructure and economic development: some diagnostic indicators. Washington (DC): World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/383071468739248249/pdf/multi-page.pdf.

- Robinson R, Thagesen B, editors. 2004. Road engineering for development. 2nd ed. Taylor & Francis.

- Sedegah D, Tuffour M, Premkumar J. 2023. We have fears: farmers’ eviction concerns of Tema motorway expansion, Ghana. Cogent Soc Sci. 9(1). doi: 10.1080/23311886.2023.2187009.

- Smyth E, Vanclay F. 2017. The social framework for projects: a conceptual but practical model to assist in assessing, planning and managing the social impacts of projects. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 35(1):65–80. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2016.1271539.

- Smyth E, Vanclay F. 2024. Social impacts of land acquisition, resettlement, and restrictions on land use. In: Vanclay F Esteves AM, editors. Handbook of social impact assessment and management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; p. 355–376.

- Stjernborg V. 2023. Social impact assessments (SIA) in larger infrastructure investments in Sweden: the view of experts and practitioners. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 41(6):463–475. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2023.2263236.

- Stolp A, Groen W, van Vliet J, Vanclay F. 2002. Citizen values assessment: incorporating citizens’ value judgements in environmental impact assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 20(1):11–23. doi: 10.3152/147154602781766852.

- Tanzarn N. 2017. Scaling up gender mainstreaming in rural transport: policies, practices, impacts and monitoring processes final case study report: uganda. Africa Community Access Partnership. https://www.research4cap.org/ral/Tanzarn-IFRTD-2017-ScalingUpGMPoliciesPracticesImpactsMonitoringProcesses-UgandaCS-AfCAP-RAF2044J-171213-redacted.pdf.

- Tserendorj S, Tsevelmaa Baldan T, Marshall P. 2013. Healthy together, our future: guidebook for HIV/AIDS/STI prevention in the context of mining and transport. Manilla: Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/81922/42027-012-dpta.pdf.

- Tsunokawa K, Hoban C, eds 1997. Roads and the environment: a handbook. Washington, D.C: World Bank. https://www.cbd.int/financial/doc/wb-roadsandenvironment1997.pdf.

- Uganda. 1998. The land act (chapter 227). Ministry of Land, Housing & Urban Development. https://mlhud.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Land-Act-Chapter_227.pdf.

- Uganda. 2019. Roads act, 2019. https://ulii.org/akn/ug/act/2019/16/eng@2019-09-25.

- UKDOT. 2023. Road lengths in Great Britain: 2022. United Kingdom Department of Transport. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/road-lengths-in-great-britain-2022/road-lengths-in-great-britain-2022.

- United Nations. 2001. Multistage environmental and social impact assessment of road projects: guidelines for a comprehensive process. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. ST/ESCAP/2177. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=ae804a12948f81f7f54e6f2fcb3b0a1c5b140e7f.

- United Nations. 2011. Guiding principles on business and human rights. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf.

- [UNRA] Uganda National Roads Authority. 2020. UNRA corporate strategic plan 2020/21-2024/25. Uganda National Roads Authority. https://www.unra.go.ug/resources/unra-strategic-plans/unra-corporate-strategic-plan-2020-21-2024-25.

- [UNRA] Uganda National Roads Authority. 2021. End of year performance for FY 2021/22 media briefing by the Executive Director. Uganda National Roads Authority. https://www.unra.go.ug/projects/roads

- [UNRA] Uganda National Roads Authority. 2022. UNRA projects status report for June 2022. Uganda National Roads Authority. https://www.unra.go.ug/resources/publications/annual-performance-reports/projects-status-report-for-june-2022.

- [UNRA] Uganda National Roads Authority. 2023. National roads projects status report, March 2023. Uganda National Roads Authority. https://www.unra.go.ug/projects/roads

- Vanclay F. 2002. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 22(3):183–211. doi: 10.1016/S0195-9255(01)00105-6.

- Vanclay F. 2017. Project induced displacement and resettlement: from impoverishment risks to livelihood enhancement and an opportunity for development. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 35(1):3–21. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2017.1278671.

- Vanclay F. 2024. Benefit sharing and enhancing outcomes for project-affected communities. In: Vanclay F Esteves AM, editors. Handbook of social impact assessment and management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; p. 426–443.

- Vanclay F, Baines J, Taylor CN. 2013. Principles for ethical research involving humans: ethical professional practice in impact assessment part I. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 31(4):243–253. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2013.850307.

- Vanclay F, Esteves AM, Aucamp I, Franks D. 2015. Social impact assessment: guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects. Fargo (ND): International Association for Impact Assessment. https://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/SIA_Guidance_Document_IAIA.pdf.

- Vanclay F, Hanna P. 2019. Conceptualising company response to community protest: principles to achieve a social license to operate. Land. 8(6):101. doi: 10.3390/land8060101.

- Vijayakumar A, Mahmood M, Gurmu A, Kamardeen I, Alam S. 2023. Social sustainability assessment of road infrastructure: a systematic literature review. Qual Quantity. 58(2):1039–1069. doi: 10.1007/s11135-023-01683-y.

- Vilela T, Harb A, Bruner A, da Silva Arruda V, Ribeiro V, Alencar A, Escobedo Grandez A, Rojas A, Laina A, Botero R. 2020. A better Amazon road network for people and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117. p. 7095–7102. 10.1073/pnas.1910853117.

- Walker R, Perz S, Arima E, Simmons C. 2011. The TransAmazon highway: past, present, future. In: Brunn S, editor. Engineering earth: the impacts of megaengineering projects. Springer; p. 569–599. 10.1007/978-90-481-9920-4_33.

- Wan Z, Titheridge H, Hou N. 2024. Current social impact assessment practices for transport projects and plans in Chinese cities. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 42(2):141–159. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2024.2317523.

- World Bank. 2017. Working together to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse: recommendations for world bank investment projects. Washington (DC): World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/482251502095751999/pdf/117972-WP-PUBLIC-recommendations.pdf.

- World Bank. 2019a. From crisis to opportunity: addressing risks of gender-based violence across the Uganda Portfolio. Washington (DC): World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/205561563917898576/pdf/From-Crisis-to-Opportunity-Addressing-Risks-of-Gender-Based-Violence-Across-the-Uganda-Portfolio.pdf.

- World Bank. 2019b. Good practice note: road safety. Washington (DC): World Bank. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/648681570135612401-0290022019/original/GoodPracticeNoteRoadSafety.pdf.

- World Bank. 2019c. Hopes, costs and uneven burden: the impacts of labor influx from road projects on women and girls in rural Malawi. Washington (DC): World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/390121557142364783/pdf/The-Impacts-of-Labor-Influx-from-Road-Projects-on-Women-and-Girls-in-Rural-Malawi-Hopes-Costs-and-Uneven-Burden.pdf.

- World Bank Inspection Panel. 2016. Republic of Uganda, transport sector development project – additional financing (P121097): investigation report 106710-UG. Washington (DC): World Bank Inspection Panel. https://www.inspectionpanel.org/sites/default/files/ip/PanelCases/98-Inspection%20Panel%20Investigation%20Report.pdf.

- World Bank Inspection Panel. 2018. Democratic Republic of Congo second additional financing for the high-priority roads reopening and maintenance project (P153836). Investigation Report 124033-ZR. Washington (DC): World Bank Inspection Panel. https://www.inspectionpanel.org/sites/ip-ms8.extcc.com/files/cases/documents/120- Inspection %20Panel%20Investigation%20Report%28English%29-27%20April%202018.pdf.

- World Bank Inspection Panel. 2020. Insights from the World Bank Inspection Panel: responding to project gender-based violence complaints through an Independent Accountability Mechanism. Washington (DC): World Bank Inspection Panel. https://www.inspectionpanel.org/sites/default/files/publications/Emerging%20Lessons%20Series%20No.%206-GBV.pdf.

- World Bank Inspection Panel. 2024. Bolivia: Santa Cruz Road corridor connector project (San Ignacio-San José) (P152281). Investigation Report 187506-BO. Washington (DC): World Bank Inspection Panel. https://www.inspectionpanel.org/sites/default/files/cases/documents/162-Inspection%20Panel%20Investigation%20Report-12%20February%202024.pdf.