ABSTRACT

This study explores how the ideological divide between the radical right and liberal left is anchored in the common sense reasoning of ordinary citizens. Across Western Europe, cleavage research has documented a divide in attitudes towards immigration and cultural liberalization which some view as a new cleavage of ‘universalism’ versus ‘particularism’. Yet it is unclear how this squares with the fact that most citizens are non-ideologues with only moderate political interest and knowledge. Building on Clifford Geertz, Pierre Bourdieu, and recent research into the politics of group identities, we theorize how even in the absence of fully worked-out political ideologies, citizens mobilize forms of common sense reasoning based on group distinctions and moral intuitions. We apply this approach in a rare qualitative comparison of political reasoning on both sides of the new divide, analyzing narrative interviews (N=64) with groups positioned on its opposing sides: workers or small owners voting for the radical right; and sociocultural professionals voting for the liberal left. We show how ‘common sense particularism’ and ‘common sense universalism’ draw on distinct intuitions regarding the worthy self, the scope of solidarity, and the normative status of community. These intuitions resonate with class-specific social experiences and group referents.

Introduction

‘The shaping of belief systems of any range into apparently logical wholes […] is an act of creative synthesis characteristic of only a miniscule proportion of any population’, writes Philip Converse in a canonical text of political sociology (Converse Citation1964, 8). Consistent and ideologically constrained beliefs may be common among politicians, activists and expert observers like political scientists. But the majority of citizens are non-ideologues and make sense of politics using categories that do not map neatly onto the divides of elite politics (Kinder and Kalmoe Citation2017). Recent research has indicated that group identities and moral commitments loom large in ordinary political reasoning, and that these are as important as ideology for understanding contemporary political conflict (see below and Zollinger Citation2022). As a consequence, political sociology has begun developing frameworks for understanding the group-centered, moral, and affective dynamics of non-elite political reasoning. In this article, we contribute to this endeavor both conceptually and empirically.

Conceptually, we revisit the work of Clifford Geertz (Citation1983) and Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1984) and propose that the notion of common sense is helpful for theorizing non-ideological modes of ordinary political reasoning. Common sense political reasoning differs from ideology in that it is more immethodical and ad hoc and operates primarily on the basis of moral intuitions and group distinctions taken from the domain of everyday life. Following Geertz and Bourdieu, we argue that distinct social groups draw on different forms of common sense, which are informed both by the groups’ social experiences and by the discourses of political elites.

Empirically, researching common sense political reasoning requires complementing well-established quantitative methods with qualitative studies of public opinion. In the empirical part of the paper, we apply our framework in an exploratory analysis of qualitative evidence on contemporary cleavage formation. Here we do not seek to develop a new model of attitude formation or cleavage change, but to demonstrate that qualitative research on common sense can be helpful for exploring how attitudes are expressed in the reasoning of ordinary citizens, beyond and complementary to ideological schemes of reasoning. The object of our study is a crucial divide of public opinion in contemporary Western European politics: the divide between ‘universalist’ and ‘particularist’ positions on immigration, cultural liberalization, and the politics of deservingness.

As numerous analyses show, the political salience of such issues has increased sharply in the last four or so decades, leading to the reorientation of parties and party systems, and amplifying long-existing differences in the political attitudes of the working and middle classes (see below and Hall et al. Citation2023). Where twentieth century political conflict was dominated by a distributional left-right opposition along the class cleavage, that line of conflict today is being complemented or even eclipsed by struggles over borders and belonging, libertarian ideas of sociopolitical governance, cosmopolitan openness, welfare chauvinism, and cultural conservatism (Rovny and Polk Citation2019; Zollinger Citation2022). Häusermann and Kriesi (Citation2015), among others, describe all these struggles as aspects of a common new cleavage of ‘universalism’ versus ‘particularism’ (see also Bornschier et al. Citation2021),Footnote1 where particularism stands for ‘collective heritage and tradition that command compliance, including a clear demarcation of boundaries between those who are members and those who are not’; while universalism points to a ‘conception of social order in which all individuals enjoy and support a wide and equal discretion of personal freedoms to make choices over their personal lives’ (Spicker Citation1994, 18).

Scholars are still grappling with questions about whether struggles about borders, inclusion, and authority do indeed form a unitary and new divide (Lux et al. Citation2022; Langsæther and Stubager Citation2019); whether they constitute a cleavage in the deeper sociological sense of a politically mobilized rift in social structure and identities (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2020; Strijbis et al. Citation2020; Teney et al. Citation2013); as well as about the potential structural drivers behind this divide – various authors citing globalization, educational expansion, value change, deindustrialization and tertiarization, labor market dualization and/or technological change as processes creating new winners and losers, and thereby the potential for conflict (see e.g. Beramendi et al. Citation2015; Kurer and Palier Citation2019). What is less contentious is that parties on the radical right and the liberal and/or green ‘new left’ often bundle opposite positions on the issues summarized as universalism-particularism; and that across many advanced capitalist countries the electorates of these parties are marked by an overrepresentation of certain educational groups and occupational classes: while particularly male and rural production workers and small owners with basic or intermediary degrees are overrepresented on the more conservative, closure-oriented, or particularist side of the divide; academically trained professionals – particularly women, city dwellers, and those employed in the sociocultural sectors – are overrepresented on the universalist side (Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018; Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2014; Oesch Citation2012; Ford and Jennings Citation2020).

In what to our knowledge is the first qualitative analysis of both sides of the new divide, we draw on a corpus of 64 narrative interviews collected in Germany, France, and the Netherlands, with respondents representing ideal-typical combinations of social and ideological profiles on the opposite poles of the new divide: workers and small business owners supporting the populist radical right on the one hand; and sociocultural professionals of the cultural middle class voting for new left parties on the other. In an in-depth reanalysis of data collected in two separate but coordinated research projects, we develop a comparative typology of common sense intuitions underlying particularism and universalism, touching on ideas of self, solidarity, and community. Regarding ideals of the worthy self, we show that particularism is expressed through moral notions of work-centered reciprocity and ‘earned esteem’; which contrast with a common sense ideal of ‘broadening of one’s horizons’, i.e. of personal growth brought on by the exposure to otherness, which is central to universalist reasoning. Regarding the scope of solidarity, common sense intuitions of a necessary prioritizing and making of ‘hard choices’ in the face of scarcity contrast with an emphasis on the ethical obligation of ‘giving back’ and sharing received privileges on the universalist side. Regarding the boundaries of community, the ideal of behavioral conformity with ‘shared rules’ contrasts with a commitment ‘not to judge’, asserting the normative neutrality of (most) cultural differences.

In this way, our study explores key forms of common sense reasoning by which the new divide is articulated among some of its most typical class bases. Although no causal conclusions can be drawn from our data, this perspective allows us to point out connections and affinities between universalist and particularist modes of political reasoning and typical forms of classed social experience described by other sociological studies. We thus seek to contribute to a deepened sociological understanding of certain well-attested patterns of political alignment in postindustrial societies.Footnote2 We show that for understanding how alignments along the new divide play out in the talk of ordinary citizens, it is important to complement existing analyses of public opinion with qualitative analyses of political reasoning beyond the level of ideologically informed attitudes and preferences.

Theoretical framework

Cleavage formation beyond ideology

Before we develop the concept of common sense reasoning, we would like to situate this approach in a wider shift of attention underway in current research on cleavage transformation. Classically, this research has proceeded by linking the changing ideological supply of New Left and Radical Right parties to the ideological preferences of distinct socio-structural groups. Political conflict between parties opposed along the new cleavage here is said to ‘activate voters’ ideological schema’ (Bornschier Citation2010, 62), where ideology is understood as a ‘cognitive representation of political space’ (ibid.), echoing important definitions of ideology as an ‘organizational scheme’ (Zaller Citation1992, 96) or ‘learned knowledge structure’ holding together political considerations in an ‘interrelated network’ (Jost et al. Citation2009, 310). Along similar lines, Kriesi and his collaborators (Citation2008) focus on ‘the ideological structure of national electorates’ (Kriesi Citation2008, 323, our emphasis), while centering their argument on the appeal of ‘ideological packages’ (ibid: 19) to social groups with distinct ideological preferences. Analogously, Oesch and Rennwald’s (Citation2018) influential study on the restructuring of Western European political competition identifies positions in the political space by the ideological positions of both political parties and voters.

While all these studies have been extremely fruitful for political research, they have largely focused on one specific form of political reasoning, that of ideological partisans motivated by political considerations similar to those that govern party competition. Defining the groups engaged in cleavage conflict via their ideological schemas presupposes that citizens’ political reasoning is relatively coherent and related to the political system in a reflexive way; be it in the form of a cognitive map or specific knowledge of the ideological supply most fitting to one’s preferences (see Ford and Jennings Citation2020, 299 for a similar observation). What this leaves relatively underexplored are other forms of political reasoning ‘innocent of ideology’ (Converse Citation1964). As has often been pointed out, a large majority of the population are neither particularly interested nor highly informed when it comes to political matters and do not hold political attitudes that are consistent or constrained by partisan considerations (Converse Citation1964; see also Achen and Bartels Citation2016; Gaxie Citation1978). The majority of citizens are non-ideologues showing only little knowledge of issue content (Campbell et al. Citation1960), and this holds today as much as it did in the 1960s (Achterberg and Houtman Citation2009; Althaus Citation2003; Della Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Kinder and Kalmoe Citation2017; Zaller Citation1992). Solely treating such citizens as members of ideological camps runs the risk of unduly projecting the standpoint of expert observers, giving us little way of knowing how political divides are expressed in the real-life reasoning of many ordinary citizens.

Recent strands of research, which our contribution builds on, have reacted to this problem by extending the analysis of cleavage formation to forms of reasoning beyond ideology. An important impulse came from studies in political psychology which pointed to the centrality of heuristics and cognitive shortcuts which may provide rationality and consistency also to the political considerations of ‘low information’ voters and non-ideologues (see Popkin Citation1992; Colombo and Steenbergen Citation2020; Mercier Citation2020; Boyer Citation2018). As a growing number of studies show, a particularly crucial set of heuristics draws on notions of group belonging, group evaluation, and senses of group position (e.g. Achen and Bartels Citation2016; Brensinger and Sotoudeh Citation2022; Davis and Wilson Citation2022; Gest Citation2016; Kinder and Kalmoe Citation2017; Kusow and deLisi Citation2021). Indeed, group-centered reasoning was what Converse (Citation1964) had already proposed as the more common alternative to ideologically consistent belief systems (see also Kinder Citation2006). This thread was recently picked up by Elder and O’Brian (Citation2022) who show that attitudes toward social groups structure political belief systems, in the sense that respondents form positions towards political issues by placing them in relation to more or less esteemed social in- and outgroups. Similarly, studies of affective polarization highlight the power of affectively charged group allegiances for anchoring political divides (Iyengar et al. Citation2019; Mason Citation2018; Gidron et al. Citation2020). Elder and O’Brian (Citation2022) also point out that the crucial register in which group distinctions are articulated is that of morality, particularly the comparison between more or less worthy kinds of people and behaviors (see also Haidt Citation2012; Hochschild Citation1986; Lamont Citation2000; Prasad Citation2009).

Interestingly, this ‘normative’, ‘group’ or ‘identity level’ of political divides had already been theorized as a central component of cleavage formation in classical definitions (see and Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Bartolini and Mair Citation1990; Kriesi Citation2010), but remained peripheral in empirical applications until very recently (De Wilde et al. Citation2022).

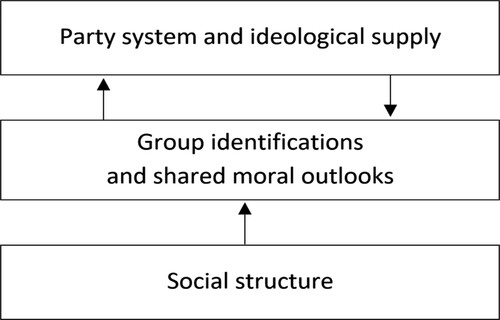

Figure 1. Three elements of a cleavage: social structure, group identifications and shared moral outlooks, and their reinforcement by parties’ differing ideological supply (our elaboration, based on Bartolini and Mair Citation1990; Lipset and Rokkan Citation1967; Bornschier Citation2010).

Regarding the universalism-particularism divide, Bornschier et al. (Citation2021) suggest that new cleavage politics is anchored in group identities by showing that radical right voters in four European countries identify with a consistent set of group categories (like ‘rural dwellers’, ‘fellow nationals’, or ‘people with an apprenticeship’) and demarcate themselves from others (like ‘cosmopolitans’, ‘cultured people’, and ‘university graduates’), while an almost symmetrically opposite pattern obtains for new left voters. Steiner et al. (Citation2023) find that group categories of ‘globalization winners’ and ‘losers’ are subjectively salient and politically consequential for voters. Particularism has also been linked to affectively charged forms of ‘rural consciousness’ and localism (Cramer Citation2016; Fitzgerald Citation2018) and the drawing of symbolic boundaries between one’s ingroup and specific outsiders, such as migrants and the poor (Rathgeb Citation2021; see also Gest Citation2016; Hochschild Citation2016; Gidron et al. Citation2020). Studies looking at morality have further shown the centrality of moral conservatism for particularist attitudes, emphasizing the importance of ‘binding’ moral foundations of loyalty, authority, and sanctity (Haidt Citation2012), as well as a cognitive link between political problems and ideals of family organization according to a ‘strict father’ model (Lakoff Citation2016).

Liberal – in our parlance: universalist – attitudes have been characterized as marked by moral concerns for the well-being of others (Miles and Vaisey Citation2015), the critical non-reification of the status quo of cultural practices (Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2009) and permissiveness (see also Broćić and Miles Citation2021). On the level of group identities, universalism has been linked to education-based identities and boundary work, especially in fields of study predicated on cultural rather than economic capital (Flemmen et al. Citation2022; Hooghe et al. Citation2022; Lamont Citation1987; Stubager Citation2009). Cosmopolitan lifestyles based on the engagement with diversity and transnational culture – which Ollrogge and Sawert (Citation2022) and Helbling and Jungkunz (Citation2020) find to form part of the group level of the new divide – has been characterized as a new or emergent form of cultural capital (Prieur and Savage Citation2013; Igarashi and Saito Citation2014; see also Calhoun Citation2002; Mau Citation2009). For sociocultural professionals in particular, it has also been suggested that client-oriented interpersonal work logics foster an identification with disadvantaged groups, such as migrants (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2014).

A crucial study by Delia Zollinger (Citation2022) on the universalism-particularism cleavage in Switzerland brings many of these threads together by looking at the self-understandings of far right and new left voters ‘in their own words’, through open-ended survey responses. Using quantitative text analysis, Zollinger reconstructs that far right voters’ self-descriptions typically center on ‘the dignity of a simple, honest life built around self-reliance on hard work and common sense, whereas new left voters highlight their self-perceived openness, tolerance, dynamism, and unorthodox lifestyle’ (ibid., 19). All this suggests that the universalism-particularism divide is rooted in a wide-reaching network of identifications, moral commitments and group demarcations that complements and exceeds differences in issue preferences and political ideologies. However, we are still missing a conceptual framework for understanding and comparatively studying this deeper structure of non-ideological reasoning and the way in which universalist and particularist attitudes are expressed through it.

Common sense political reasoning

We propose that this mode of ordinary political reasoning can be fruitfully theorized by drawing on the sociological notion of common sense. As famously worked out by Alfred Schütz (Citation1953), common sense stands for an intuitive, habitualized, and non-reflexive mode of making sense of the social world.Footnote3 It is based on a shared, and usually tacit, set of cultural and normative presuppositions specific to certain groups and specific historical moments; forming part of the realm of "background ideas" (Schmidt Citation2016, 320). As Clifford Geertz (Citation1983: 18ff.) explained, common sense is marked by a number of key characteristics: First of all, this reasoning insists on the naturalness, or ‘of-course-ness’, of social reality, i.e. the representation of matters as part of the ‘taken for granted’ ways of everyday life. Relatedly, common sense is ‘literal’, in the sense of an implicit conviction that most important realities are not cunningly hidden in the depths, but can be glimpsed quite straightforwardly from the surface of ‘things as they are’. As Berger and Luckmann (Citation1990, 37) write: ‘Common sense knowledge is the knowledge I share with others in the normal, self-evident routines of everyday life. […] It is simply there, as self-evident and compelling facticity.’ Thereby, common sense presents itself as inherently accessible and ‘open to all’, ‘the general property of […] all solid citizens.’ (Geertz Citation1983, 24). Furthermore, common sense is practical, as in not relating to an abstract knowledge of facts, but to a broader sagacity of knowing how to make judgments and navigate the social world.Footnote4 Following from this practical character, common sense is immethodical and ‘ad hoc’: ‘[It] comes in epigrams, proverbs, obiter dicta, jokes, anecdotes, contes moraux […] not in formal doctrines, axiomized theories, or architectonic dogmas’ (Geertz Citation1983, 23; see also Lévi-Strauss Citation1962).Footnote5

As displays, Geertz’s insights help clarify how the common sense perspective can complement one centered on ideological reasoning. Rather than being based on reflexive and theorized organizational schemes aiming at systematic coherence (Zaller Citation1992, 96), the common sense mode of reasoning is based on taken-for-granted and practical understandings anchored in a habitualized structure of implicit intuitions, i.e. a ‘sense of knowing without knowing how one knows’ (Epstein Citation2010, 296, see also Haidt Citation2012). And while ideological reasoning operates with explicitly political categories taken from the oppositions and distinctions of the political system (e.g. ‘left’ and ‘right’, ‘social liberalism’, ‘fiscal conservatism’, etc.), common sense reasoning draws on categories taken from the domain of everyday life (e.g. ‘do-gooders’, ‘tight purses’, or ‘lazy bones’). Importantly, it is because this social – rather than formally political – sphere constitutes the central domain of reference of common sense political reasoning, that categories of morality, group belonging, identification, and demarcation (e.g. ‘hard-working’, ‘tolerant’, ‘open-minded’ etc.) loom particularly large here. As Bourdieu (Citation1984: 418) writes:

There is every difference between the intentional coherence of the practices and discourses generated from an explicit ‘political’ principle and the objective systematicity of the practices produced from an implicit principle, below the level of ‘political’ discourse, that is, from objectively systematic schemes of thought and action, acquired by simple familiarization, without explicit inculcation, and applied in the pre-reflexive mode.

Table 1. Ideological vs common sense political reasoning.

Data and method

In the following empirical analysis we draw on this conceptualization of common sense for gaining a ‘thicker’ sociological understanding of non-ideological modes of reasoning across the new divide. We analyze interview data to reconstruct common sense forms of particularist and universalist reasoning and to relate them to the social experiences of central carrier groups. In thus seeking to study the socio-political conflict of the new divide ‘from the natives’ point of view’ (Geertz Citation1974), our approach draws methodological inspiration from what some have called an ‘ethnographic turn’ in political science research (Brodkin Citation2017; Wedeen Citation2010). As Katherine Cramer (Citation2016: 19, our emphasis) puts it, the aim of a similar approach ‘is to distinguish how people themselves combine attitudes and identities – how they create or constitute perceptions and use these to make sense of politics’. A privileged way to gain empirical access to these processes are in-depth narrative interviews (Czarniawska Citation2004). In contrast to closed-ended survey questions, where citizens are sometimes asked to position themselves on issues they are unfamiliar with or indifferent to (Duchesne et al. Citation2013; Gaxie Citation2011; Stoekel Citation2013), this method allows respondents to express themselves in their own terms (see Gamson Citation1992), thereby enabling researchers to study how salient categories acquire their meaning in the context of people’s social situation and everyday life.

In this paper, we utilize a theoretically guided pooled non-probability sample of in-depth interviews collected in the course of two research projects which were carried out separately but in close coordination with one another. Both studies centered on providing a qualitative extension of cleavage research by probing the embeddedness of political reasoning in self-understandings and biographical narratives (see Appendix A for interview protocols). For the present reanalysis of data from these two projects, interview samples are pooled so as to yield data on two populations most likely to engage in universalist and particularist political reasoning. These are respondents whose social position and political orientations align with the patterns established in previous cleavage research: workers and small business owners voting for the radical right (N = 44); and sociocultural professionals declaring sympathies with New Left Parties (N = 20).

Interviews with particularist workers and small owners were conducted in France and the Netherlands, those with universalist sociocultural professionals in Germany. The Dutch and French respondents were recruited via snowball sampling, personal networks of friends, colleagues and family as well as by visiting political meetings and contacting political parties. The German respondents were similarly sampled via snowballing, email lists, workplace visits, and public announcements, e.g. in doctors’ practices (see Damhuis Citation2020 and Westheuser Citation2021 for more detailed information on the data collection). A table summarizing socio-demographic information about our samples can be found in Appendix A. It is here shown that along a broad range of factors, including gender, region of residence (including East/West for Germany), degree of urbanization, sector, and employment status, the samples capture the variety found in the real world groups from which they are drawn. This appendix also discusses the sole exception for the factor of age. It is worth clarifying that qualitative samples do not aim at representativity but on drawing out a wide range of types from particularly informative cases. This is the case a fortiori for our exploratory study, where the focus lies on drawing out typical discursive forms of common sense universalism and particularism without claiming an exhaustive coverage of universalists and particularists as groups, or of universalism and particularism as cultural systems. What our sampling achieves is a selection of groups most likely to exhibit universalist and particularist orientations. While often considered problematic in quantitative studies, ‘sampling on the dependent variable’ is common practice in qualitative research, which is forced to compensate a lack of breadth and generalizability for a careful in-depth exploration of specific cases whose relevance has been identified from theory and previous research (Brady and Collier Citation2010; Kelle Citation2001).

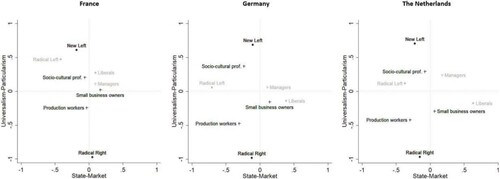

Since our pooling strategy does not lead to a comparison between countries but to an independent reconstruction of discursive patterns in two class-attitudinal groups, country-level social and institutional specificities are not foregrounded in this study. However, we looked at data e.g. on migration shares, GDP, and unemployment to ascertain that the countries are similar enough to warrant a pooling of data.Footnote9 shows an analysis of survey data justifying our pooled sampling and links our in-depth study to the larger cleavage pattern revealed in survey-based research. Factor analyses of attitudinal data from the European Social Survey (Round 8, 2016/17) reveal the exact same alignment of occupational classes and parties along the universalism-particularism dimension in all three countries under study here (data and method in Appendix B; for identical findings see e.g. Kriesi Citation2012, 273).

Figure 2. Political preference configurations by class and vote choice in France, Germany and the Netherlands, mean values of scores on factor scales, operationalization of the two dimensions based on Häusermann and Kriesi (Citation2015). Data: ESS8 (2016/2017).

What this establishes is that the components of our sample relate to one and the same larger phenomenon of a second dimension in the European attitudinal space (see also Oesch and Rennwald Citation2018; Rennwald and Evans Citation2014). Further, Appendix C provides an extensive cross-country comparison of the electoral, attitudinal and value orientations of sociocultural professionals across the three countries. This is to ensure that our sample of German sociocultural professionals is also informative regarding the French and Dutch cases, where this group is not covered by our data. As shown there, German sociocultural professionals are slightly more progressive and open to migration than their Dutch and French counterparts, but the overall pattern of this class’ attitudes and value orientations is very similar across the three countries. To not overload an already expansive paper, our analysis does not draw out differences between the discursive patterns of subgroups within the samples, e.g. between French and Dutch respondents. However, these and other differentiations can be found in the more extensive explorations in Damhuis (Citation2020) and Westheuser (Citation2021).

We re-analyzed our interview data through a three-step inductive approach that combines thematic and reconstructive analysis. First, we focused on sequences in which respondents discussed issues of the universalism-particularism divide (immigration, welfare deservingness, and cultural liberalism, as well as, less importantly, European integration) or the divide itself (e.g. in statements about radical right and new left parties and their supporters). We used techniques of thematic analysis (Ryan and Bernard Citation2003, 88ff.) to identify relevant themes in these interview transcripts. Besides conventional strategies such as coding repetitions, oppositions, metaphors and ‘indigenous categories’ (Patton Citation1990), this first step of the analysis put a special focus to features of common sense talk as theorized above, such as expressions of of-course-ness, the use of proverbs and colloquialisms, as well as moralized group distinctions. Second, we extended and reformulated these themes by developing a comparative typology (Kelle and Kluge Citation2010), which spells out three core oppositions between common sense universalism and particularism (see the concluding section). In a third step, inspired by reconstructive analysis techniques of the Documentary Method (Bohnsack Citation2014, 219ff.) and drawing on the wider corpus of interview data, we deepen our understanding of this typology by connecting respondents’ intuitions to the social conditions which shape their self-understandings and biographical narratives.Footnote10 While the first step yields central discursive patterns of particularist and universalist reasoning, and the second clarifies the dimensions on which these patterns are opposed, the third allows us to understand group-specific social experiences making these patterns resonate.

Results

The results of our analysis are presented in the form of a comparative typology of key common sense intuitions that inform positions on the universalism-particularism divide. We inductively reconstruct three intuitions underlying common sense particularism (which we label ‘Earned Esteem’, ‘Necessary Priorities’, and ‘Shared Rules’) and common sense universalism (‘Broader Horizons’, ‘Giving Back’, and ‘No Judgment’). These intuitions are shown to diverge along three underlying dimensions also identified inductively. The three dimensions of difference concern (1) conditions of worth expressed in self-ideals; (2) the scope of solidarity; and (3) the normative status of community and the rules of ingroup-outgroup relations.

Common sense particularism

Along these three dimensions, common sense particularism can be identified by three main intuitions: a self-ideal based on the valorization of effort and reciprocity, a scope of solidarity limited by a sense of scarcity and zero-sum competition, and the normative primacy of the autochthonous community. Each concerns distinct aspects of particularism and is articulated with reference to different moral group categories.

Self-ideal: earned esteem

The first intuition of particularist common sense is the ideal of an alignment of esteem and individual effort. Everything in life is to be earned, nothing to be expected for free. Particularist respondents typically describe themselves as part of ‘those who work’ (or those who worked, when retired or ill), stake their self-worth on this fact, and demarcate it from lazy ‘takers’. Highlighting what Lamont (Citation2000) called a ‘disciplined self’ of work ethic and responsibility, Pierre, a 58 year-old French worker in a vineyard who entered professional life at sixteen, depicted himself as someone who ‘worked all the time’. As with many other respondents, Pierre’s self-understanding was rooted in a biographical trajectory characterized by difficulties at school and the absence of institutionalized cultural capital in the form of diplomas (Bourdieu Citation1986). Along similar lines, Thomas, a welder in a factory of about fifty employees, who is building his own house and hoping to start his own welding business one day, described himself as ‘intellectually stupid (con) but manually good (bon)’. The fact that these respondents have made their way in life with their own hands, in the face of initial difficulties, anchored their profound belief in a reciprocity of achievements and personal effort. ‘Everyone is entitled to what they have worked for’Footnote11, as Jeremy, another welder, puts it. This self-ideal revaluates manual work by opposing it to less worthy groups, whose work ethic is seen to fall short of the respondents’ own moral discipline. According to Anthony, for instance, a 22 year-old warehouseman working in a Parisian suburb after repeating two years at high school, young Maghrebis do not break the law because of a lack of opportunities, but because of a lack of discipline:

If you move your ass, if you prove yourself, that’s all you need. I also had to prove myself. And I made it! … If they would agree that their fate is in their own hands, that it’s not because of their skin color, there would be much fewer problems. Instead we don’t stop giving them excuses.

The sense of producers’ pride and the political critique building on it (see also Ivaldi and Mazzoleni Citation2019; Kochuyt and Abts Citation2017) is at times even used to demarcate the entire nation from lazy and morally irresponsible people in countries abroad. Leon, a small business owner in a peripheral village thus considers it ‘crazy’ that in the Eurocrisis financial aid was provided to countries like Greece ‘where people wear pyjamas all day’. The variety and, to some extent, interchangeability of undeserving groups reveals that beyond any specific policy area, the core concern is with the moral principle of reciprocity between effort and reward. Political appeals of ‘welfare chauvinism’ and restricted deservingness activate common sense categorical schemes centered on a producerist self-ideal of ‘earned esteem’, which can be seen to resonate with a social experience of respondents with limited cultural capital drawing status from their capacity to prevail in challenging, often physically exhausting workplaces.

Solidarity: necessary priorities

The second intuition of particularist common sense centers on scarcity and the necessary restriction of one’s scope of solidarity under conditions of limited means. Particularist reasoning is centered on trade-offs and the inevitability of zero-sum competition, which is often highlighted by an analogy between private and state budgeting. Lenie, a retired cleaning woman, stated:

They say it’s wrong when you say ‘our own people first’, but that’s just the way it is. Because if my neighbor’s children are hungry, I feed my own children first. That’s just how it works. You're not going to feed your neighbor’s children first, are you? It’s that simple, right?

I always get this hippy socks idea [geitenwollensokken-idee], [that] everything has to be nice, you have to be kind to each other and everyone has to help each other. Sure, but there are limits. You can't help everyone. You must first make sure that you have everything in order before you can be good to someone else.

It is noticeable how frequently the critique of immigration is linked to the scandalization of suffering and social ills. Ideologically speaking, the alleged privileges of migrants are problematic because they violate the nativist principle of a preference for compatriots. What we want to highlight here, however, is that on a deeper level, it is also rejected as a break with the commonsensical intuition that in moments of scarcity and lack (‘the hungry child’, ‘misery’, ‘deep shit’) one is to focus on the essential, i.e. those closest and most deserving (see also Abts et al. Citation2021; Van Oorschot et al. Citation2022). Indeed, it would be hard to understand why social support and immigration should be presented as mutually exclusive without understanding that scarcity and necessary priorities stand at the center of the moral cosmology of particularist common sense. Scarcity, as the ground zero of ‘how things work’ ‘when it comes down to it’ is thought to bring out a deeper truth of social relations that limits the scope of altruism and centers the interest of self and ingroup. It would be nice ‘to be good to everyone’, but this is a decidedly unworldly wish. It is this sense of inescapable trade-offs and a realism of hard choices that indicates an elective affinity between the common sense of necessary priorities and the social experience of those familiar with managing a tight budget, be it their own, their family’s or that of their small firm.

Community: shared rules

The third intuition of common sense particularism is the conviction that every community has a fixed set of customary rules and that belonging to this place is conditional on demonstrating one’s abidance by these rules. This intuition overlaps with the first in placing a premium on individual effort and deploring its lack among migrant newcomers and other outsiders in need of ‘proving themselves’. Yet here the focus is more specifically on cultural conformity and the normative power that place confers to its symbolic ‘owners’, the people ‘from here’. As Jean-Yves, Sylvie’s husband, put it: ‘When you choose a country, well, you comply with what's going on there. You can't say, ‘no no, I don’t care’.’ Where in the previous section we saw an analogy of private and state budgeting, here respondents often draw an analogy between the private home and the national or local community, following the implicit principle of ‘My house, my rules’. Thus the young welder Jeremy complained that immigrants ‘act as if they were in their own home [chez eux] … They want to keep their own customs.’ Following the domestic role set, compliance to a country’s rules and customs is seen as a matter of politeness, as the proper way guests are to behave vis-à-vis their forthcoming hosts, as which the respondents understand themselves. Otherwise, as Henk, a middle aged service technician, puts it, the hosts are put in the patently absurd position of being ‘strangers in their own house’. He explains: ‘When you come here to the Netherlands, you are a guest and you have to behave. When I am a guest at your place, I adapt to you. I wouldn't even dare to offend my host or your family.’

We can certainly read this statement as a straightforward expression of nativist ideology, operating on the basis of what Roosens (Citation2000: 162) calls ‘primordial autochthony’, i.e. a quality attributed to one’s in-group of ‘being born on a well-defined territory from parents and ancestors who are and have been ‘first occupants’.’ Yet if we want to understand the logic of arguments like these ‘from the native’s point of view’, it is crucial to note that for the respondents themselves, their political content hinges on a common sense norm of respecting hosts and their families: ‘You see, it’s like when I went to Israel once’, Sylvie explained, ‘you put on the hat [i.e. the kippa], you put on that thing … you say nothing. It's normal. This just seems logical to me’. Following an intuitive moral realism, rules are here not understood as the outcome of negotiations between different normative standpoints, but as fixed and binding ‘as is’, due to the precedence of customs. Based on previous studies we can speculate that particularly among workers, the experience of a dominated position in the workplace, the non-negotiability of work imperatives, the ‘mute compulsion’ of markets, the rules of a schooling system perceived as hostile, and more authoritarian parenting styles provide an important background anchoring the insistence on shared rules (see e.g. Beck and Westheuser Citation2022; Kohn Citation1977).Footnote13

To sum up: in the particularism of non-elite citizens, positions on new divide issues of nationality, citizenship, deservingness or crime are discussed in common sense intuitions. Key intuitions are that of proving oneself worthy of what one receives by individual effort, making necessary priorities under conditions of scarcity, and respecting customary rules of a place and its ‘owners’. These forms of common sense share affinities with the social experience of workers and small owners, notably when it comes to their lower levels of institutionalized cultural capital (e.g. school diplomas), and their familiarity with non-negotiable rules, trade-offs, and cost–benefit analyses.

Common sense universalism

We now turn to three features of common sense universalism as articulated by Green- and left-leaning sociocultural experts, i.e. professionals in the education, health and cultural sectors also dubbed the cultural middle class. We reconstruct common sense universalism as shaped by an ideal of self-development through the engagement with otherness, an understanding of solidarity as altruism, and an attempt to both highlight the multiplicity of cultural horizons and abstain from evaluation. While all three aspects directly link to the ideological content of universalism, we show them to be rooted in intuitions of a common sense shaped by social experience.

Self-ideal: broader horizons

A first intuition of common sense universalism is an ideal of self-development through the exposure to cultural otherness. Among the German respondents, this ideal was encapsulated in the ubiquitous phrase ‘you have to look beyond your own nose’ (Über den Tellerand schauen, literally: ‘looking beyond the rim of one’s own plate’). The conceptual metaphor clearly stands for an attitude of curiosity and openness. But on a deeper level, it also expresses an implicit theory of moral development that is crucial for the common sense universalism of the cultural middle class. To gain a better understanding of the world, and to develop their inherent potential, this theory holds, each person must step outside their place and community of origin and learn to engage productively with otherness, be it through traveling, variegated professional experiences, or encounters with social others like migrants, non-middle class strata or culturally distant milieus. The respondents’ self-ideal is that of people who have mastered this kind of encounter and center it in a conduct of life of ‘openness to the world’ (Weltoffenheit). Openness here is not understood as an inherent character trait, but as a learned skill, often embedded in a developmental narrative in which the protagonist actively cultivated an acceptance of otherness. As Leonie, a rural doctor, explains:

After the Abitur I went to Zimbabwe for a year and did voluntary service and during my studies I also traveled a lot. So I feel pretty privileged compared to the rest of the world, also in terms of education and the social competences that my parents taught me. Where now when I work with patients or kids, you notice that they haven’t received that, they haven’t been socialized like this.

I just cannot stomach those pub counter slogans [Stammtischparolen] anymore. People complaining about foreigners without ever having been to a foreign country … There just weren’t many people who had studied, who had ever gotten out of their village … I think these generations first need to die out [wegsterben], as harsh as it sounds.

Solidarity: giving back

The second common sense intuition that universalism draws on is an understanding of material distributions not centered on scarcity (and the resulting question of ‘who gets what’), but on ethical questions of sharing and altruism (see also Haidt Citation2012: ch. 7), i.e. as questions of good character. The altruistic intuition rests on a positive anthropology which sees individuals as placed in a web of interdependence with others, both in the sense of beneficial sociability and of mutual obligations. In a distinctly middle class register, this altruistic commitment is linked by many to a sense of ‘privilege’, an obligation to ‘give back’ some of what the respondents feel to have received. As Wiebke, a junior academic living in a Western German university town, explains:

Everyone has a responsibility to help shape the world … And to not be careless and just let things happen … Because we have so many privileges and possibilities that we can spare the time to do something for our environment, and the world, and things we believe in.

I think one’s politics depend a lot on the circumstances in which one grows up. What is the spirit in which I live [Lebensgefühl]? … I myself feel protected enough in the world to not have to close myself off. I can open myself to a transformation towards more equality. I am not afraid of losing anything.

The group specificity of this common sense intuition can be identified with a work logic centered on immaterial goods like knowledge, health or social relations, as well as an occupational ethos of public sector work shielded from the profit motive (Kitschelt and Rehm Citation2014; Wright Citation1997). The social experience of sociocultural professionals decenters money and material relations – in stark contrast to that of the workers and small owners: status claims here are largely based on immaterial goods such as education or the capacity for leading a flourishing life; the acquisitive function of work is relativized vis-à-vis the promise of autonomy and an alignment of life and work with one’s values; and scarcity is relatively absent as a problem in respondents’ narratives.Footnote16 All this contributes to turning questions of material distribution into symbols of ethics, altruism, and character.

Community: no judgment

A third form of universalist common sense is a seemingly paradoxical impulse of a demonstrative non-distinction between cultural communities. Universalist respondents of the cultural middle class are attuned to differences in the cultural horizons of individuals and groups, but at the same emphasize their indifference so as to avoid judgment. As Kevin, a nurse living in a large multicultural city declares:

When I go outside, I do not notice whether people are, shall we say, not from our cultural zone [Kulturkreis]. Even if they are, I simply would not notice, because it is not of interest to me … It makes no difference what language someone speaks or whether they’re wearing a headscarf. I never cared about that, it’s just irrelevant to me.

Respondents often report active efforts to cultivate for themselves a more non-prejudiced mindset. Sophie, for instance, recounts a moment where she ascribed the sexist demeanor of a male colleague to his Arab roots, but immediately ‘caught herself’: ‘I suddenly realized, God, Sophie, you are also not free of this racist stuff! You also think in those stereotypes’. ‘I know I bear many prejudices’, Martin says, ‘but I do my best to overcome them’. The common sense of non-distinction thus takes the status of a feeling rule, a sense of how people feel they ought to feel (Hochschild Citation1979) which also shapes political outlooks: Respondents seek to train their emotional responses, thoughts, and expressions so as not to reinforce evaluative distinctions between social groups. Interestingly, norms of politeness form a central point of reference here as well, though in a way that sharply differs from the particularist pattern. For universalist respondents, communicating social differences is seen as inherently in danger of misrecognizing others. ‘I don’t want to put people in boxes’, Anne, a doctor, says when explaining why she doesn't like to speak about ‘classes’:

For me that always implies an evaluation. [Like] ‘worker’ is somehow a lower job. I don’t see it that way. It is super important that we have people who empty the trash cans, who serve us at the restaurant.

In summary, we can glean from the reasoning of one of its most typical carrier groups how universalist reasoning too operates on the basis of common sense intuitions, whose self-evidence and moral desirability respondents take for granted. These include an ideal of self-development through the encounter with cultural otherness, an ‘immaterial’ understanding of solidarity and distribution as symbols of ethics and character, and a sense of community defined by a feeling rule of demonstrative non-distinction. These intuitions are demarcated against three social categories: radical right supporters fearing the unknown, the underprivileged ‘who didn’t learn social competences’, and the ‘aloof’ and alienated rich. As this analysis also showed, the universalist common sense also bears elective affinities to the social experience of its cultural middle class bearers.

Conclusion

Recent studies indicate that a new political divide between universalism and particularism is not solely based on differences in issue preferences and political ideologies, but also rooted in a complex web of identifications, moral commitments, and group distinctions. Yet, as noted, we still lack a comprehensive conceptual framework for understanding and comparatively studying how universalism and particularism are articulated in non-ideological, moral and group-based reasoning across the divide. Inspired by the work of Clifford Geertz (Citation1983) and Pierre Bourdieu (Citation1984), we theorized this mode of reasoning beyond ideology as common sense – a habitualized, historically changing, and group-specific set of intuitions which people draw on when making sense of the world, including politics. Distinct from positions on issue content, the common sense perspective focalizes deeper sources of political alignment in moral intuitions and senses of group position. Although fuzzier and less systematic than ideology, forms of common sense can be studied systematically and comparatively, as we demonstrated in the empirical part of the article. Focusing on the highly relevant case of a divide between citizens with universalist and particularist preferences, we drew on extensive interview data to identify typical forms of common sense reasoning among core social bases of the new divide.

As summarized in , we inductively identified three central common sense intuitions for universalism and particularism, respectively. Particularism draws on intuitions of self-reliance, zero-sum-competition, and a moral realism regarding customary rules, while universalism draws on intuitions of an enrichment of subjectivity by the encounter with otherness, an ‘immaterial’, ethical reading of material relations, and a demonstrative relativism eschewing value judgments. These intuitions can be ordered along three latent dimensions of difference across the divide. First, universalism and particularism are shown to rest on starkly different ideals of the worthy self: While universalists pride themselves in being persons with broad horizons and cultural skills developed through the exposure to otherness, particularists emphasize their deservingness as self-reliant ‘makers’. Second, common sense intuitions differ with regard to the scope and conditions of solidarity. Common sense particularism was here shown to center material scarcity and the inevitability of trade-offs. Common sense universalism, by contrast, operates with a notion of solidarity as altruism, treating material distributions as symbols for immaterial goods and ethical character traits. Third, common sense reasoning on the two sides of the divide differs in its intuitions about community. Particularism was here shown to rest on a common sense intuition of shared rules, equating community, rules, and place. Drawing on a domestic host–guest analogy, cultural rules are understood as an expression of firstcomers’ privileged claims to ‘their’ place. By contrast, universalism was shown to mobilize a carefully cultivated common sense of non-distinction, rooted in prohibitions against judging cultural others. On the particularist side, we thus see how political reasoning is embedded in common sense notions of work and reciprocity, scarcity, competition, and the moral force of the customary. On the universalist side, political reasoning is entangled in common sense theories of subjective development and an ethical conduct of life implicitly centered on the immaterial goods of cultural capital.

Table 2. Typology of common sense particularism and universalism.

As our analysis indicates, the moral and group distinctions feeding into the new divide exhibit clear elective affinities with classed social experiences, positions, and status strategies. The universalist common sense of cultural middle class respondents, for instance, was shown to revolve around embodied and objectified cultural capital, with societal and personal development alike imagined in terms of educational experiences; and self-ideals focalizing embodied skills and (transnational) mobility. Similarly, feeling rules mandating a dethematization of difference could be interpreted in the context of occupational logics and a sense of social position specific to the cultural middle class. On the particularist side, we noted how common sense intuitions resonated with classed experiences of workers and small business owners in the forms of self-ideals with producerist overtones, a sense of scarcity and familiarity with trade-offs and cost–benefit analyses, as well as the socialization into non-negotiable rules.

Using Bourdieu’s (Citation1984: 418) terms, the common sense intuitions we observed can be understood as ‘generative formulae’ by which universalist and particularist reasoning is elaborated in everyday life. These intuitions concerning self, solidarity, and community add flesh to the ‘group identifications and shared moral outlooks’ () defining the identity or group level of a potential new cleavage. As shown in , particularist common sense intuitions underpin moralized in- and group distinctions between makers, contributors, hard workers, deserving nationals and rule-abiding people on the one hand; and takers, shirkers, and unfairly privileged, rule-breaking outsiders on the other. Universalist common sense distinguishes open, ethical, authentic, and non-judgmental people with variegated experiences and complex subjectivities from those ‘who never got out’, selfish materialists, as well as those who lack the will or education to think beyond stereotypes. While many of these in- and outgroup distinctions resemble those found in previous studies (e.g. Rathgeb Citation2021; Zollinger Citation2022), shifting the focus to common sense enables us to additionally grasp the overarching modus operandi by which the normative and group-related dimensions of universalism and particularism are articulated in ordinary reasoning.

This inductive analysis also reveals points in which common sense universalism and particularism directly oppose each other, attesting to processes of cleavage formation also on the non-ideological group level (see Bornschier et al. Citation2021): these are the centering of material or immaterial goods, the narrow or larger ethical scope ascribed to material distributions and the stark opposition between moral realism and moral relativism. At the same time, the analysis also shows how the new divide does not need to take the form of symmetrical ideological camps, mobilized e.g. as ‘patriots’ versus ‘globalists’, but can also form on the basis of asymmetrical intuitions, e.g. regarding the self-ideals of ‘deserving contributors’ and ‘people with broader horizons’, each tied in with incommensurable moral vocabularies. Disagreements which in public discourse become elaborated in terms of ideological enmity may, in fact, be the expression of differing common sense intuitions and social experiences (see also Hochschild Citation2016, 5ff). As our analyses shows both sides of the divide draw on arguments that are rational within the scope of their respective common sense presuppositions.

While the link between these social experiences and the group level of the new cleavage should be thought of as non-deterministic, the affinities between class and common sense reconstructed here add depth to survey evidence on the classed nature of the new divide (see e.g. Jarness et al. Citation2019; Flemmen et al. Citation2022). In the terminology of this study, our suggestion is that classed social experiences make distinct common sense intuitions appear more plausible than others. These intuitions, in turn, lend resonance to political appeals and condition the perceived appropriateness of public policies, akin to the "background ideas" studied by discursive institutionalism (Schmidt Citation2008, Citation2016). This specifies how forms of ordinary reasoning provide both mobilization potentials and constraints for political parties and other political entrepreneurs. Coming back to Converse (Citation1964), the anchoring of political thought in non-ideological intuitions also explains how attitudes can be structured along the new divide in electorates with relatively low levels of ideological consistency: even politically less sophisticated citizens can be mobilized on the basis of common sense intuitions.

Future studies could assess the independence and political force of common sense by comparing the reasoning of groups and class fractions already mobilized on the new cleavage (as looked at in this study) with that of groups that have proven unreceptive to such mobilization.Footnote18 Similarly, future studies could spell out how political entrepreneurs articulate and activate elements of the common sense of social groups, e.g. by analyses of political communication, or by tracing the common sense of comparable groups in settings with and without strong parties mobilizing on the new divide. On a broader methodological level, our findings lead to the plea that conventional survey analyses of cleavage politics be complemented with what Cramer (Citation2016) calls ‘listening methods’, based on ethnography and in-depth interviewing. To use Runciman’s (Citation1966, 7) words, surveys can ‘like an aerial photograph enable us [to] see clearly the outline of woods and fields; but this only increases our curiosity to look under the trees.’

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

The authors affirm that this article meets ethical guidelines and adheres to the legal requirements of the study country.

reus_a_2300641_sm5217.pdf

Download PDF (420.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Delia Zollinger and Simon Bornschier for their feedback on an earlier draft of this paper. We also thank the three anonymous referees for their constructive comments, along with the participants in a workshop at the Utrecht University School of Governance and the 28th International Conference of Europeanists (Lisbon, July 1st, 2022), particularly Dave Attewell, Lukas Haffert, Silja Häusermann and Aljoscha Jacobi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article

Notes

1 Other terminologies sharing the assumption of a unified cleavage structure emerging include that of ‘GAL-TAN’, i.e. Green-Alternative-Left versus Traditionalist-Authoritarian-Nationalist (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018); or that of a cleavage of ‘cosmopolitanism’ and ‘communitarianism’ (De Wilde et al. Citation2019).

2 A pattern which we name by the heuristic shorthand of the universalism-particularism divide while remaining somewhat agnostic about its status as a full-blown and politically unitary cleavage.

3 Schütz (Citation1953: 3, orig. emphasis) noted that ‘the social world […] has a particular meaning and relevance structure for the human beings living, thinking, and acting therein. They have preselected and preinterpreted this world by a series of common-sense constructs of the reality of daily life and it is these thought objects which determine their behavior.’

4 In this particular regard, our understanding of common sense could be linked to what Bourdieu (Citation1984) calls habitus, i.e. the embodied dispositions and schemes which individuals and groups draw on when making sense of the social world. In his Outline of a Theory of Practice, Bourdieu explicitly makes this connection, stating: ‘One of the fundamental effects of the orchestration of habitus, is the production of a commonsense world’ (Bourdieu Citation1977, 80, our emphasis).

5 Geertz adds a sixth quality of ‘thinness’ which we see as already implicit in the previous terms.

6 This understanding of common sense resembles that of Gramsci (Citation1971: 471), who writes that ‘[c]ommon sense is not a single unique conception, identical in time and space [but] fragmentary, incoherent, in conformity with the social and cultural position of those masses whose philosophy it is.’ In this historicity, the sociological usage of the term differs from that of analytic philosophy (see e.g. Moore Citation1993).

7 In Mouffe’s terms (2013: 2), common sense is the result of ‘sedimented hegemonic practices and never the manifestation of a deeper objectivity’.

8 In other words, we are looking at the ways in which universalism and particularism are articulated in non-ideological, common sense terms without suggesting that the same respondents might not also be mobilizing ideological schemes in other instances (or even simultaneously). Accordingly, we do not consider common sense and ideological political reasoning to be mutually exclusive on the level of individuals and groups. As Gaxie (Citation2013: 301) puts it, ‘all social agents usually activate several modes of production [of political opinions] at the same time’ (see also Bourdieu Citation1984, 426). The focus of analysis is not on non-ideologues as a discrete group, but on non-ideological modes of political reasoning.

9 For instance, in 2015, the share of migrants (of the total population) was 12.2% in France; 12.5% in Germany; and 11.8% in the Netherlands (Global Migration Data Portal Citation2023).

10 Accordingly, ‘the technique and end’ of our qualitative analysis, to cite C. Wright Mills (Citation1959, 236) is not to provide ‘frequencies or magnitudes’ (let aside making causal claims between an isolated independent and a specific dependent variable), but to give ‘the range of types’.

11 'Chacun bosse, chacun sa paye.’

12 Similarly, for Patricia, a 48 year-old widow and mother of three working in a large warehouse, the idea of admitting immigrants ‘doesn’t make sense’: ‘We welcome them while we have French people who are in misery and we don't help them. I find that repulsive!’

13 That said, specifically the prerogative of natives is an intuition shared by wide parts of society, making it somewhat harder to identify the specific social experience lending resonance to this intuition of common sense particularism.

14 As nurse Kevin puts it, ‘it tells you a lot about the personality of a person if you are afraid of anything you don’t know. That’s how politics and personality are linked, I think.’

15 For our analysis it is not important whether individuals ‘actually’ live up to this ideal, but only that it is a salient intuition which guides how respondents generate their social and political discourse.

16 Or it is treated as a temporary problem of life phases such as being a student or early career years.

17 He illustrates this as combining ‘brass band music and sausages on father’s day’ with ‘classical liturgy’.

18 In addition, mapping common sense in large-N studies could improve the external validity of this study, which, as an in-depth investigation of ideal-typical social and ideological profiles, has an exploratory character.

References

- Abts, K., Dalle Mulle, E., Kessel, S. and Michel, E. (2021) ‘The welfare agenda of the populist radical right in Western Europe: combining welfare chauvinism, producerism and populism’, Swiss Political Science Review 27(1): 21–40.

- Achen, C. and Bartels, L. (2016) Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Achterberg, P. and Houtman, D. (2009) ‘Ideologically illogical? Why do the lower-educated Dutch display so little value coherence?’, Social Forces 87(3): 1649–70.

- Althaus, S. L. (2003) Collective Preferences in Democratic Politics: Opinion Surveys and the Will of the People, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bartolini, S. and Mair, P. (1990) Identity, Competition, and Electoral Availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates, 1885–1985, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beck, L. and Westheuser, L. (2022) ‘Verletzte Ansprüche. Zur Grammatik des politischen Bewusstseins von ArbeiterInnen’, Berliner Journal für Soziologie 32(2): 279–316.

- Beramendi, P., Häusermann, S., Kitschelt, H. and Kriesi, H. (eds.). (2015). The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berger, P. L. and Luckmann, T. (1990) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, New York: Anchor Books.

- Bohnsack, R. (2014) ‘Documentary method’, in U. Flick (ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, London: Sage, pp. 217–33.

- Bornschier, S. (2010) Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right: The New Cultural Conflict in Western Europe, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bornschier, S., Häusermann, S., Zollinger, D. and Colombo, C. (2021) ‘How ‘us’ and ‘them’ relates to voting behavior—social structure, social identities, and electoral choice’, Comparative Political Studies 54(12): 2087–122.

- Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The forms of capital’, in J. G. Richardson (ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, Westport: Greenwood, pp. 241–58

- Bourdieu, P. (1989) ‘Social space and symbolic power’, Sociological Theory 7(1): 14–25.

- Boyer, P. (2018) Minds Make Societies: How Cognition Explains the World Humans Create, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Brady, H. E. and Collier, D. (2010) Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Brensinger, J. and Sotoudeh, R. (2022) ‘Party, race, and neutrality: investigating the interdependence of attitudes toward social groups’, American Sociological Review 87(6): 1049–93.

- Broćić, M. and Miles, A. (2021) ‘College and the ‘culture war’: assessing higher education’s influence on moral attitudes’, American Sociological Review 86(5): 856–95.

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2017) ‘The ethnographic turn in political science: reflections on the state of the art’, Political Science & Politics 50(1): 131–4.

- Calhoun, C. (2002) ‘The class consciousness of frequent travelers. Toward a critique of actually existing cosmopolitanism’, South Atlantic Quarterly 101(4): 869–97.

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E. and Stokes, D. E. (1960) The American Voter, New York: John Wiley.

- Colombo, C. and Steenbergen, M. R. (2020) ‘Heuristics and biases in political decision making’, in P. Redlawsk (ed.), Oxford Encyclopedia of Political Decision Making, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Converse, P. E. (1964) ‘The nature of belief systems in mass publics’, in D. E. Apter (ed.), Ideology and Discontent, New York: The Free Press, pp. 206–261.

- Cramer, K. J. (2016) The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Czarniawska, B. (2004) Narratives in Social Science Research, London: Sage.

- Damhuis, K. (2020) Roads to the Radical Right: Understanding Different Forms of Electoral Support for Radical Right-Wing Parties in France and the Netherlands, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davis, D. W. and Wilson, D. C. (2022) Racial Resentment in the Political Mind, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Della Carpini, M. X. and Keeter, S. (1996) What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters, New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- De Vries, C. E. and Hobolt, S. B. (2020) Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- De Wilde, P., Koopmans, R., Merkel, W., Strijbis, O. and & Zürn, M. (eds.), (2019) The Struggle Over Borders: Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- De Wilde, P., Langsaether, P. E. and Özdemir, S. (2022) ‘Critical junctures and the crystallization of cosmopolitanism and communitarianism’, European Political Science Review 15: 157–76.

- Duchesne, S., Frazer, E., Haegel, F. and Van Ingelgom, V. (2013) Citizens’ Reactions to European Integration: Overlooking Europe, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Duvoux, N. (2009) L’Autonomie des Assistés, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Elchardus, M. and Spruyt, B. (2009) ‘The culture of academic disciplines and the sociopolitical attitudes of students: a test of selection and socialization effects.’, Social Science Quarterly 90(2): 446–60.

- Elder, E. M. and O’Brian, N. A. (2022) ‘Social groups as the source of political belief systems: fresh evidence on an old theory’, American Political Science Review 116(4): 1407–1424.

- Epstein, S. (2010) ‘Demystifying intuition: what it is, what it does, and how it does It’, Psychological Inquiry 21(4): 295–312.

- Fitzgerald, J. (2018) Close to Home: Local Ties and Voting Radical Right in Europe, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Flemmen, M. P., Jarness, V. and Rosenlund, L. (2022) ‘Intersections of class, lifestyle and politics: new observations from Norway’, Berliner Journal für Soziologie 32(2): 243–77.

- Ford, R. and Jennings, W. (2020) ‘The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe’, Annual Review of Political Science 23(1): 295–314.

- Gamson, W. A. (1992) Talking Politics, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gaxie, D. (1978) Le Cens Caché: Inégalités Culturelles et Ségrégation Politique, Paris: Le Seuil.

- Gaxie, D. (2011) ‘What we know and do not know about citizens’ attitudes towards Europe’, in D. Gaxie, N. Hubé and J. Rowell (eds.), Perceptions of Europe: A Comparative Sociology of European Attitudes, Colchester: ECPR Press, pp. 1–16.

- Gaxie, D. (2013) ‘Retour sur les modes de production des opinions politiques’, in P. Coulangeon and J. Duval (eds.), Trente ans après La Distinction de Pierre Bourdieu, Paris: La Découverte, 293-306.

- Geertz, C. (1974) ‘‘From the native’s point of view’. On the nature of anthropological understanding’, Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 28(1): 26–45.

- Geertz, C. (1983) ‘Common sense as a cultural system. In Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology, New York: Basic Books, pp. 73–93.

- Gest, J. (2016) The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gidron, N., Adams, J. and Horne, W. (2020) American Affective Polarization in Comparative Perspective (Elements in American Politics), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Global Migration Data Portal (2023) Migration Shares. [Online]. Available at: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/dashboard/compare-geographic (Accessed: 21 July 2023).

- Gramsci, A. (1971) ‘Selections from the prison notebooks’, in Q. Hoare and G. Nowell-Smith (eds.), London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Haidt, J. (2012) The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Hall, P. A., Evans, G. and Kim, S. I. (2023) Political Change and Electoral Coalitions in Western Democracies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Häusermann, S. and Kriesi, H. (2015) ‘What do voters want? Dimensions and configurations in individual-level preferences and party choice’, in P. Beramendi, S. Häusermann, H. Kitschelt and H. Kriesi (eds.), The Politics of Advanced Capitalism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–230.

- Helbling, M. and Jungkunz, S. (2020) ‘Social divides in the age of globalization’, West European Politics 43: 1187–210.

- Hochschild, A. (1979) ‘Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure’, American Journal of Sociology 85(3): 551–75.

- Hochschild, J. L. (1986) What’s Fair. American Beliefs About Distributive Justice, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hochschild, A. (2016) Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, New York: New Press.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(1): 109–35.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G. and Kamphorst, J. (2022) “Field of Education and the Transnational Cleavage.” Paper Presented at the Conference “Cleavage Formation in the 21st Century,” University of Zurich, July 18/19th 2022.

- Igarashi, H. and Saito, H. (2014) ‘Cosmopolitanism as cultural capital: exploring the intersection of globalization, education and stratification’, Cultural Sociology 8(3): 222–39.

- Inglehart, R. (1990) Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ivaldi, G. and Mazzoleni, O. (2019) ‘Economic populism and sovereigntism: the economic supply of European radical rightwing populist parties’, European Political Science Review 11(3): 335–355.

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N. and Westwood, S. J. (2019) ‘The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States’, Annual Review of Political Science 22(1): 129–46.

- Jarness, V., Flemmen, M. P. and Rosenlund, L. (2019) ‘From class politics to classed politics’, Sociology 53(5): 879–99.

- Jarness, V. and Friedman, S. (2017) ‘‘I’m not a snob, but … ’: class boundaries and the downplaying of difference’, Poetics 61: 14–25.

- Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M. and Napier, J. L. (2009) ‘Political ideology: its structure, functions, and elective affinities’, Annual Review of Psychology 60(1): 307–37.

- Kelle, U. (2001) ‘Sociological explanations between micro and macro and the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods’, Forum Qualitative Social Research 2(1): 95–117.

- Kelle, U. and Kluge, S. (2010) Vom Einzelfall zum Typus, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kinder, D. R. (2006) ‘Belief systems today’, Critical Review 18(1–3): 197–216.

- Kinder, D. R. and Kalmoe, N. P. (2017) Neither Liberal, nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kitschelt, H. and Rehm, P. (2014) ‘Occupations as a site of political preference formation’, Comparative Political Studies 47(12): 1670–706.

- Kochuyt, T. and Abts, K. (2017) Ongehoord Populisme: Gesprekken Met Vlaams Belang-Kiezers Over Stad, Migranten, Welvaartsstaat, Integratie En Politiek, Brussel: ASP.

- Kohn, M. (1977) Class and Conformity. A Study in Values, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Koning, E. E. and Puddister, K. (2022) ‘Common sense justice? Comparing populist and mainstream right positions on law and order in 24 countries’, Party Politics, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688221131983.

- Kriesi, H., et al. (2008) West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H. (2010) ‘Restructuration of partisan politics and the emergence of a new cleavage based on values’, West European Politics 33(3): 673–85.

- Kriesi, H., et al. (2012) Political Conflict in Western Europe, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kurer, T. and Palier, B. (2019) ‘Shrinking and shouting: the political revolt of the declining middle in times of employment polarization’, Research & Politics 6(1): 1–6.

- Kusow, A. M. and deLisi, M. (2021) ‘Attitudes toward immigration as a sense of group position’, Sociological Quarterly 62(2): 323–42.

- Lakoff, G. (2016) Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lamont, M. (1987) ‘Cultural capital and the liberal political attitudes of professionals’, American Journal of Sociology 92(6): 1501–6.

- Lamont, M. (2000) The Dignity of Working Men: Morality and the Boundaries of Race, Class, and Immigration, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Langsæther, P. E. and Stubager, R. (2019) ‘Old wine in new bottles? Reassessing the effects of globalization on political preferences in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research 58(4): 1213–33.

- Lévi-Strauss, C. (1962) La Pensée Sauvage, Paris: Plon.

- Lipset, S. M. and Rokkan, S. (1967) ‘Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments: An introduction’, in S. M. Lipset and S. Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments, New York: Free Press, pp. 1–64.

- Lux, T., Mau, S. and Jacobi, A. (2022) ‘Neue Ungleichheitsfragen, neue Cleavages? Ein internationaler Vergleich der Einstellungen in vier Ungleichheitsfeldern’, Berliner Journal für Soziologie 32(2): 173–212.