Abstract

There is limited knowledge about why political actors are dissatisfied with journalism. This article attempts to answer this question by pointing to individual-level perceptual processes of politicians. We argue that part of politicians’ unease with the media can be explained by the hostile media phenomenon (HMP). Originally developed in audience research, the HMP refers to a process by which highly involved individuals tend to perceive media coverage as biased against their own views. Based on a survey of politicians in three European countries, we demonstrate that the HMP also holds for political actors. More importantly, we show that the HMP makes politicians less likely to contact journalists and more likely to use conflict and drama to gain public attention. Finally, the HMP decreases politicians’ trust in democracy by fostering the belief that the public is not adequately informed about political matters. Theoretical and societal consequences are discussed.

Introduction

Whether the relationship between politicians and journalists is characterized by mutual trust and understanding is a question that continues to garner attention from political communication scholars (Brants et al. Citation2010; Elmelund-Præstekær, Hopmann, and Nørgaard Citation2011; Maurer and Beiler Citation2017; Sellers Citation2000; Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011). There is no doubt that journalists and politicians depend on each other in a mutual, close, and sometimes uneasy relationship (Blumler and Gurevitch Citation1981). While journalists have to rely on the input of politicians to produce news, politicians likewise need journalists to communicate their ideas and arguments. In fact, many, if not most, politicians realize that they need to be visible in the news media to be politically successful (Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011; Strömbäck and van Aelst Citation2013).

In this context, the question of how political actors perceive journalistic content is of great importance. If politicians regard the news media as hostile to their own views, they may react with suspicion, conceal their plans and strategies, and become cynical about news media organizations and news journalists. This may have fundamental consequences on how politicians and journalists work together in fulfilling their public duties, and for democracy as such. More specifically, since journalists and politicians are mutually dependent and in need of each other, cynicism and distrust from one side may alter the behavior and perceptions of the opposing side (Brants et al. Citation2010).

Despite the relevance and timeliness of this topic, the nature and consequences of politicians’ bias perceptions of journalism are not well understood to date (Domke et al. Citation1999). Some have argued that unfavorable media portrayal of politicians or the rising agenda-setting power of journalism is responsible for politicians’ dissatisfaction with journalism (Brants et al. Citation2010). Most of this research is connected to the concept of “mediatization”, which refers to the growing importance of media logic compared to political logic in the process of communicating politics (Kriesi et al. Citation2013; Strömbäck Citation2008). Others find that structural or system-level factors matter for the relations between journalists and politicians (Maurer Citation2011). Yet there is no research on individual-level perceptual processes on the side of politicians. Also, we have scarce knowledge about how politicians’ hostile media perceptions are related to other important outcomes, such as contact to journalists or satisfaction with democracy.

This article suggests an alternative perspective to understand how politicians perceive the news media. We argue that, similar to individual citizens, politicians process and respond to media coverage, and therefore, are prone to the same perceptual phenomena (Kepplinger Citation2007). There is growing evidence that the extent to which the news content is objectively imbalanced is less important than individual perceptions of news media impartiality (Daniller et al. Citation2017; Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004; Matthes Citation2013a). To advance this argument, we draw on research on the hostile media effect or hostile media phenomenon (HMP) (Vallone, Ross, and Lepper Citation1985). More specifically, we suggest that politicians’ perceptions of journalism may in part be explained by a psychological process that is driven by high ego involvement. According to the HMP, highly involved audiences tend to perceive media coverage as biased against their own views (Vallone, Ross, and Lepper Citation1985).

By connecting the HMP to research on the relationship between politicians and journalists, this article fills two important research gaps. First, we are the first to empirically demonstrate that the HMP depends on politicians’ ideological extremity: The more extreme politicians are in their ideology, the more they see the media as hostile to their own views. This fundamental and novel finding helps us to further understand why politicians may evaluate journalistic news as biased. Second and even more importantly, this article explores the consequences of the HMP, a largely neglected area of research when it comes to political actors. More specifically, we test if hostile media perceptions impact the individual behavior of politicians, their campaign strategies, and their satisfaction with their own political system’s democratic performance.

The Relationship Between Politicians and Journalists

The relationship between journalists and politicians has been referred to as a “marriage de raison” (Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011) or a “tango of give and take” (Brants et al. Citation2010, 20) that is characterized by “trust and distrust, love and hate” (Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011, 76). There is no doubt that both sides depend on each other (Davis Citation2007; Sellers Citation2000). Journalists serve as a public “watchdog” that observes the political elite, informs, and also entertains the public. Politicians, by contrast, answer to the demands of the electorate by explaining their strategies and plans with the help of news media. In the past decades, there has been a rapid change in the relationship between journalists and politicians. Politicians are increasingly forced to adapt to the news media’s production logic. This “media logic,” as Altheide and Snow (Citation1979) call it, refers to the rules of selecting and constructing political news that foster attention among the public; for instance, conflict, negativity, personalization, or entertainment orientation (Strömbäck Citation2008). As a consequence, “many—if not most—political actors and institutions find themselves torn between the media and their logic, on the one hand, and politics and political logic, on the other” (Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011, 170).

Against this background, some studies have explored how politicians perceive and evaluate journalists. A recent survey of Dutch politicians reveals rather negative attitudes about political journalists (Brants et al. Citation2010). This cynicism is driven by dissatisfaction with the news coverage. Politicians in a range of European democracies also feel that journalists have a lot of power to set the political agenda and influence their careers (Maurer Citation2011) and that the portrayal of politics is governed by media logic. Those feelings are spurred by perceptions that journalists are politically minded actors (Maurer and Pfetsch Citation2014). That is, politicians believe that “journalists are too event driven and too eager for power struggles or for setting the political agenda themselves, and they are interpreting political reality more than covering the political issues and policy decisions in a substantial way” (Brants et al. Citation2010, 37). In line with this, the survey of Swedish and Norwegian members of the parliament by Aalberg and Strömbäck (Citation2011) suggests that politicians are dissatisfied with the way that the news media covers politics (see also Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011).

Although all these studies enhance our understanding of how politicians perceive and evaluate journalism, research remains rather scarce about the factors that prompt political actors to criticize the news media for their coverage (Domke et al. Citation1999). We suggest that one part of politicians’ critical evaluation of and behavior toward journalists can be explained by a well-known mechanism prominently studied in audience research, the HMP.

Explaining the Distrust of Politicians: The Hostile Media Phenomenon

The HMP describes a process in which highly involved individuals perceive the news media as more hostile compared to individuals who are less involved. The HMP was first observed by Vallone, Ross, and Lepper (Citation1985), who exposed pro-Israeli and pro-Arab American students to a television broadcast about the 1983 Beirut massacre. Although the news story was well-balanced, both groups perceived it as biased against their own views. The HMP has been replicated in a variety of topics all over the world (Huge and Glynn Citation2010; Matthes Citation2013a; Matthes and Beyer Citation2015), both inside (Gunther, Miller, and Liebhart Citation2009) and outside the laboratory (e.g., Matthes Citation2013a; Matthes and Beyer Citation2015; Rojas Citation2010; Tsfati Citation2007; Tsfati and Peri Citation2006), exploring mechanisms (e.g., Gunther, Miller, and Liebhart Citation2009; Matthes Citation2013a) and consequences (e.g., Rojas Citation2010; Tsfati and Cohen Citation2005a).

Pioneering studies on the HMP have exposed individuals to objectively fair and balanced news stories (Vallone, Ross, and Lepper Citation1985). In addition, the HMP can also be observed with unbalanced news content. This effect has been called the relative HMP. Gunther et al. (Citation2001), for instance, exposed animal-rights activists and primate researchers to strongly slanted news articles. Both groups identified the slant as relatively more unfavorable toward their own position. Another important feature of the HMP is that its effect depends on the expected reach of a medium and the characterization of the source as a journalist. In other words, the HMP cannot be observed when the identical article is presented in a non-media context simply because “a low-reach channel, one that has little or no apparent outside audience, is viewed with a benign eye” (Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004, 450). The HMO is usually explained by selective categorization, which makes “viewers with opposite attitudes recall identical items (e.g., images, facts, or arguments), but classify a predominance of individual items as hostile to their own side” (Giner-Sorolla and Chaiken Citation1994, 166).

It is important to stress that the HMP is driven by people’s involvement (Gunther et al. Citation2001; see Matthes Citation2013a). One key dimension of involvement is political or ideological extremity. That is, the effect has been found to be higher for people who hold extreme political attitudes (e.g., Matthes Citation2013a), or score high on ideology strength of extremity (Huge and Glynn Citation2010; Oh, Park, and Wanta Citation2011). In other words, those people who are extremely liberal or extremely conservative are more likely to be susceptible to the HMP compared to those who are more neutral on the left-right political spectrum (see Huge and Glynn Citation2010; Matthes Citation2013a). With regard to politicians’ perceptions of news coverage, we can conclude that ideology extremity should be a positive predictor of hostile media perceptions. In support of this notion, one could also argue politicians in the extremes are more distant to the positions of the mainstream media. In order to observe the HMP for political actors, therefore, we need to demonstrate that politicians that have high ideology extremity perceive the news media as hostile against their own political views. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: Politicians with high ideological extremity will perceive a greater news media hostility than politicians with low ideological extremity.

Consequences of Hostile Media Perceptions

Hostile media perceptions are certainly not without consequences. If politicians “think journalists are doing a bad job, this is likely to affect their interactions with the media” (Brants et al. Citation2010, 27). More specifically, politicians may conclude that journalists are not receptive to their arguments, and if they are, journalists may report them in distorted ways. Politicians may, therefore, see no point in presenting their views, revealing important background information, or giving journalists the opportunity to ask—presumably nagging—questions. As a result, politicians may fear that journalists will use any information they can get to counter-argue in order to strengthen opposing views. In terms of interpersonal relationships, such a reaction can be characterized as a lack of trust (Luhmann Citation1979; Misztal Citation1996). Trust (distrust) is associated with approach (avoidance) motivation, and it always refers to future action. According to Tsfati and Cohen (Citation2005a), when, based on the HMP, “our experience with an institution involves unfairness and deprivation, our future expectations of that institution will be less trusting” (31–32). As a consequence of hostile media perceptions and distrust, political actors are less likely to contact journalists and reveal their plans and ideas. This line of reasoning is supported by a plethora of studies that demonstrate that hostile opinion environments foster avoidance motivations with respect to interpersonal discussion, political participation, or engaging in social activities (e.g., Matthes Citation2013b; Nir Citation2011). Thus, when politicians believe that journalists tend to support opposing views, it is better to avoid rather than to seek contact. This leads to our second hypothesis:

H2: Hostile media perceptions will be negatively related to politicians’ contact with journalists.

Of course, when politicians are disgruntled due to hostile media perceptions, they can withhold information from journalists. However, to be successful in the political arena, they still need to spread and promote their ideas and goals. So, if politicians believe that journalists are not receptive to their arguments, they have to seek alternative ways of gaining public attention. That is, rather than using other strategies such as presenting arguments to journalists in a deliberate manner, they may rely on conflict and drama (instead of substance) in order to be heard in a public debate. Conflict and drama are important news values that increase the chances of media coverage (Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011). Conflict and drama may not only be used by journalists but also by politicians: If politicians employ conflict and drama, it is more likely that their arguments will be represented in the news. More specifically, conflict and drama make journalistic intervention less likely because these values are at the heart of the media logic (Strömbäck Citation2008). Without conflict and drama, politicians may believe that their opponents’ arguments will be favored. As Kriesi (Citation2012) observed, “those organizations that rely on the expansion of conflict need to do so, because they are not paid enough attention to otherwise” (14). Therefore, the perception of party-hostile news media should foster the belief that conflict and drama will override hostile journalistic attitudes and increase news visibility. In short, journalists may be biased when it comes to substantive issue arguments; but when it comes to conflict and drama, journalists have to listen.

H3: Hostile media perceptions will be positively related to politicians’ assessment that conflict and drama are effective communication strategies to gain public attention.

In addition to the belief in conflict and drama, hostile media perceptions may also influence politicians’ satisfaction with the functioning of democracy. Empirical data about political elite’s satisfaction with democracy are scarce. In one rare exception, Moritz (Citation2010) found that MPs have significantly higher level of satisfaction with democracy than normal citizens. But why does politician’s satisfaction with democracy matter? First, distrust in democracy may lead to a lack of support of core political institutions. For instance, when not satisfied with democracy, politicians may question the legitimacy of democratic rules and try to bypass institutions to advance their political aims. Second and related to this, given that political elites are role models with respect to their attitudes toward the political system (Higley and Burton Citation2006), dissatisfaction in politicians may spread to the general public triggering a downward spiral. That is, if parts of the political elite criticize the legitimacy of political institutions, one can expect a rapid decline of democratic support in those parts of the population that sympathize with those elites. Finally, for a democracy to thrive, political elites must share a willingness to compromise with other elites on issues that oppose them, “to obey largely unwritten rules of political conduct, and to support and protect existing political institutions” (Higley and Burton Citation2006, 202). Consequently, if some politicians lose trust in the political system, prospects for liberal democracy are at risk.

The argument that hostile media perceptions may influence an individual's satisfaction with democracy is also presented in a study by Tsfati and Cohen (Citation2005a). The authors observed a strong and significant relationship between audience members’ hostile media perceptions and their trust in democracy. When citizens see the media as hostile toward their views, they may conclude that the public is not adequately informed. Democracy, however, is built on the idea that all political actors have fair access to the news, and that the public gets all important information in order to arrive at informed opinions. That is, the news media should bring the views of all political actors to the public’s attention in a balanced way (see Graber Citation2003). This view is elaborated on by Tsfati and Cohen (Citation2005a):

The perception that others are ill informed because the news media are not providing them with access to the truth (as one sees it) is frustrating and detrimental to the belief that political decisions are being made in a fair and just way. Hence, in situations of high involvement, trust in news media is an especially crucial component of trust in democracy. (33)

H4: Hostile media perceptions will cause politicians to believe that the media does not adequately inform citizens about political matters (H4a). This belief, in turn, will decrease politicians’ satisfaction with democracy (H4b).

Finally, we aim to explain how the two strategies of getting media attention—contacting journalists and focussing on conflict and drama—impact politicians’ satisfaction with democracy. First, we theorize that the perceived effectiveness of conflict and drama in getting public attention is negatively related to politicians’ satisfaction with democracy. There is an array of empirical evidence that suggests that conflict leads citizens to decreased political trust at the individual, institutional, and system level (Mutz and Reeves Citation2005). In particular, conflict signals to the public that political actors are not able or not willing to come to a fair agreement on important political matters. For politicians, they may conclude that conflict reduces the likelihood of deliberative agreement, which is at the heart of democratic theory. Conflict and drama is arguably something negative in light of democratic theory and normative expectations toward politicians, according to which politicians are expected to succeed by their substantive arguments, not by relying on conflict. Thus, if politicians come to believe that a normatively negative strategy such as conflict pays off in general, they may put less trust in democracy.

Second, we assume the opposite effect for contact with journalists. Politicians, who (as a result of their low bias perceptions) frequently contact journalists to deliver their messages, should be more satisfied with democracy compared to politicians who choose to disdain journalists. Contact and satisfaction with democracy should, therefore, be positively related. The reasoning for this proposed relationship is threefold: First, when politicians have no or weak contact with journalists, they will be unsuccessful in shaping the public agenda. Limited contact, therefore, can be considered as disadvantageous in the political struggle, and will lead to limited satisfaction. When politicians are in frequent contact with journalists, by contrast, chances are higher that they can deliver their message to the public. Likewise, politicians also use journalists as an important resource to learn about what the public thinks (Davis Citation2007). Second and related to this, when there are infrequent contacts with journalists, politicians may believe that the media does not fulfill its main function as intermediary. This is arguably related to less satisfaction with democracy. Third, when there is infrequent contact, politicians either actively avoid contact, or they come believe that journalists prefer other elites. Given the importance of journalists in a democracy, both situations may be negatively related to satisfaction. This leads to our final two hypotheses:

H5: Politicians’ perception that conflict and drama are effective communication strategies will have a negative impact on their satisfaction with democracy.

H6: Frequent contact with journalists will have a positive impact on politicians’ satisfaction with democracy.

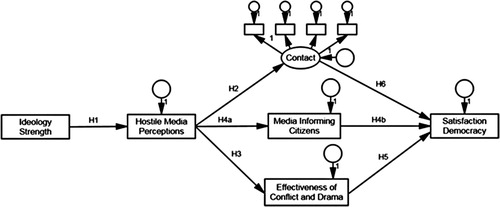

Our hypotheses are summarized in . Due to a lack of a theoretical basis, we have not formulated any hypotheses on the relationship between contact, the belief that media does not adequately inform citizens, and conflict/drama values (see ). However, we will, of course, report these relationships running alternative models. Due to the difficulty of collecting large samples of politicians, the hypotheses are tested with data from three countries: Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Because the choice of countries follows the similar systems design, we did not formulate hypotheses on the differences between the countries. However, the effect of country will be statistically examined and controlled.

FIGURE 1 Hypothesized relationships. Intercorrelations of the measurement errors (between Contact, Media Informing Citizens, and Effectiveness of Conflict and Drama), the effects of all controls, the direct effects of ideology extremity on all outcomes, the direct effect of Hostile Media Perceptions on Satisfaction with Democracy, and error labels are omitted for clarity reasons

Method

Data Collection

Data collection was completed as part of the ESF project “Political Communication Cultures in Western Europe—A Comparative Study”Footnote1 (see Pfetsch Citation2014). We focus only on politicians from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. These countries are particularly homogenous in terms of the political system (Lijphart Citation1999), the media system (Hallin and Mancini Citation2004), and their political-cultural heritage making them form a family of nations (Lehmbruch Citation1996). The similarity with respect to context allows for focus on individual-level processes among the politicians.

We used joint interview data of parliamentarians and a few government officials (Total N = 199; Germany n = 79, Switzerland n = 76, and Austria n = 44). The bulk of the respondents are parliamentarians (n = 180) sitting in the national parliament at the time of the study. Our sample also includes a small group of government officials (n = 19). The sampling procedure followed a positional approach, a technique often used in empirical elite research (Moyser and Wagstaffe Citation1987). That means that politicians occupying leading positions in a parliamentary group, a parliamentary group or committee, or the government were given priority in the sampling. These top-ranking individuals were selected using organizational charts available on the websites of the respective institutions.Footnote2 Sample size was set to n = 100 per country for practical reasons, politicians in leadership positions were approached first. In the parliament, the following positions were thus sampled with priority: presidents and vice-presidents of the house, leadership of the parliamentary groups and the standing committees. In Austria, all members of the so-called “main committee”, the most important standing committee, were included without exception. Rank-and-file parliamentarians were sampled in a second round to replace dropouts in the core sample. In Switzerland, a full sample of parliamentarians was drawn.

As the sample should reflect a variety of institutional perspectives, government officials were included as well. In this category, the positions of chancellor, federal minister, minister of state, state secretary, federal commissioner, and strategic advisor to the chancellor (Germany), or chief of cabinet (Austria) were included. However, no government officials were included in Switzerland; in Germany, chancellor and federal ministers were not contacted due to the small chances to get them to participate. Thus, altogether, 784 politicians were sampled and contacted (Austria n = 190; Germany n = 373; Switzerland n = 221) of which 199 responded resulting in an overall response rate of 25 percent. Due to the many efforts to get politicians to participate, the response rates, broken down by country and group, look quite satisfactory. In the category of government officials, they range from 24.4 percent (Austria) to 26.7 percent (Germany); among the parliamentarians, we reached between 21.1 percent (Germany) and 34.4 percent (Switzerland; Austria: 23.5 percent).

The interviews employed standardized closed questions and took approximately 20–30 minutes to complete. Questions were administered either by a Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI), personal interview, or as an online or mailed survey. Interviews were carried out by trained interviewers or the researchers themselves. In Switzerland, all interviews were carried out by a survey institute using trained interviewers.

Measures

As the dependent variable, we measured politicians’ purposeful contact with journalists. Politicians were asked how often (1 = “never” to 5 = “at least once day”) they “personally contact journalists”, “their spokespersons contact journalists”, they “meet with journalists for lunch or dinner”, and they “talk to journalists at receptions and other social events” (M = 2.64, SD = .72, α = .74). In line with Rojas (Citation2010), hostile media perceptions were gauged by combining two items. First, respondents were asked to place themselves on a political ideology scale ranging from 1 = “left” to 7 = “right” (M = 3.77, SD = 1.50). Second, they were asked to place the ideology of the national media landscape on the same left-right scale (M = 3.76, SD = 1.33). To assess hostile media perceptions, these two items were used. Politicians’ own ideological position was subtracted from the perceived media ideological position. The resulting absolute variable informed us about the perceived difference between the media’s ideology and that of the respondent (ranging from 0 to 6; M = 2.20, SD = 1.33). The higher the value, the more distant is a politician’s own ideological position from the one perceived in the media. It is important to stress that this measure does not tap bias or negative coverage.

Politicians were asked how effective they personally think it is “to gear political issues toward conflict and drama” (1 = “not effective at all” to 5 = “very effective”; M = 3.41, SD = .94) in order to attract public attention. The item “how satisfied are you with democracy?” (1 = “very dissatisfied” to 5 = “very satisfied”; M = 3.52, SD = .98) was used as a direct indicator of the subjective evaluation of the functioning of democracy. Finally, the belief that the news media adequately informs the public about politics was measured with the item “how would you say the media are informing citizens on political matters?” Responses were measured from 1 = “not very well” to 5 = “very well” (M = 3.10, SD = .88).

As the key independent variable to observe hostile media effects, we measured ideology extremity. Respondents at the extreme left (one and two) and extreme right (six and seven) were regarded as strong ideologues (35.5 percent; for this procedure, see Pattie and Johnston Citation2009; Nir Citation2005, Citation2011), the rest as low to moderate ideologues (64.5 percent).

Finally, to avoid underspecified regression models, we included a number of important controls (see Brants et al. Citation2010; Elmelund-Præstekær, Hopmann, and Nørgaard Citation2011; Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011). Besides age (18–29: 2.2 percent; 30–39: 9.8 percent; 40–49: 23.5 percent; 50–59: 36.6 percent; above 60: 27.8 percent), gender (1 = male, 2 = female; 69 percent male), and parliamentary role (0 = “opposition” with 35 percent, 1 = “government” with 65 percent), we measured work experience in years (ranging from 1 to 40, M = 12.46, SD = 8.45). We also included politicians’ rank (1 = parliamentarians, 2 = government ministers; 10 percent ministers). Politicians’ perception of media power was modeled as a latent variable comprised of three items (political influence of tabloids, political influence of public service TV, political influence of commercial TV; 1 = very low to 5 = very high).

Data Analysis

We used structural equation modeling to analyze the data. Although the share of missing values was low, we analyzed the data with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and probability of close fit (PCLOSE) served as criteria to evaluate the model fit. Contact with journalists as well as media power perceptions were modeled as latent variables. If not mentioned otherwise, we report unstandardized path coefficients (b).

Results

Our first hypotheses aimed at replicating the classic HMP for political actors. We found that politicians’ own political ideology and the perceived ideology of the media landscape were significantly and highly negatively correlated (r = −.64, p < .001). That is, the more politicians rate themselves as right-wing, the more they perceive the news media as left-wing (and vice versa). This is a clear indication of hostile media perceptions. To formally observe the full HMP, we looked for the relationship between ideology extremity and the hostile media perceptions variable in our structural equation model (see and ). The fit of the model was good (χ2 = 105.51, df = 63, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06, PCLOSE = 0.23). When only modeling the hypothesized paths depicted in , the fit is excellent (χ2 = 24.19, df = 17, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.46, PCLOSE = 0.52).

TABLE 1 Unstandardized structural equation modeling path coefficients

As predicted in hypothesis 1, there was a strong positive effect of ideology extremity on the subjective feeling that the media supports different views compared to one’s own (b = 1.84, p < .001). Having observed the HMP for political actors, we can now turn to the consequences of hostile media perceptions. Most importantly, and in line with our second hypothesis, there was a significant effect of hostile media perceptions on contacting journalists (b = −.17, p < .01). The negative sign of this effect indicates that bias perceptions make politicians less likely to actively reach out to journalists. The standardized coefficient shows that this effect was quite strong (β = −.29).

Hypothesis three examined the effect of bias perceptions on the perceived effectiveness of conflict and drama. The observed significant positive effect supports the hypothesis (b = .16, p < .05). In our fourth hypothesis, we postulated that the effect of bias perceptions on satisfaction with the functioning of democracy is mediated by the belief that the news media does a poor job in informing the public about political affairs. As expected, the path between media bias and the belief that the media adequately informs citizens was significantly negative (b = −.29, p < .001). The belief that the media adequately informs citizens exerted a significant effect on satisfaction with democracy (b = .24, p < .01). It is important to note that there was no direct effect of hostile media perceptions on satisfaction with democracy (b = .00, n.s.). As an additional test revealed, the indirect effect of bias on satisfaction with democracy, mediated by media performance in informing the public, was also significant with an additional bootstrapping test involving 5000 bootstrapping samples.

Contradicting hypothesis five, however, we found that conflict and drama were unrelated to satisfaction with democracy, although the effect pointed toward the expected direction and was close to conventional levels of statistical significance (b = −.15, p = .06). An additional structural model revealed that the perceived effectiveness of conflict and drama was unrelated to perceived media performance in informing the public (b = −.08, n.s.). We can conclude that the effectiveness of conflict and drama does not directly or indirectly relate to satisfaction with democracy.

Contrary to hypothesis six, we found no indication that contacting journalists increases satisfaction with democracy (b = −.03, n.s.). Additional structural models revealed that contact with journalists was also unrelated to effectiveness of conflict and drama (b = .05, n.s.). Yet there was a negative effect of contact on media performance in informing the public, albeit this effect was rather small (b = −.27, p < .05).

Regarding the control variables, there were some interesting findings. Female politicians were less likely to contact journalists (b = −.27, p < .05) compared to their male counterparts. While work experience and age had no effect on all outcome variables, political rank was found to be a highly significant predictor of contact behavior (b = .88, p < .001). Compared to opposition membership, government membership was negatively related to contacting journalists (b = −.49, p < .01). Finally, ideology extremity led politicians to be unsatisfied with democracy (b = −.39, p < .05). Perceived media power was related to effectiveness of conflict and drama (b = .61, p < .001).Footnote3

Discussion

Results from this study extend our understanding of the relationship between politicians and the media. We have demonstrated that politicians’ discomfort with journalism may, in part, be based on the HMP, a perceptual process that is well-understood in communication research. Even more important than the replication of the HMP for political actors, we demonstrated that bias perceptions can have consequences on how frequently politicians interact with journalists and how they evaluate the functioning of democracy. We observed a strong negative and highly significant relationship between hostile media perceptions on contact behavior. Politicians refrain from talking to journalists if they feel they are confronted with opinion-hostile media. They probably do so because they believe that journalists are differently minded and thus may not want to listen to their views. Politicians may also fear that journalists will misuse any provided information to support the opposing side. These findings underscore the insight obtained in other areas of communication research, which find that hostile opinion environments foster avoidance and dampen approach motivations (Matthes Citation2013b; Nir Citation2011). It is important to note that contact with journalists was well explained in our model (i.e., 29 percent explained variance). That is, we demonstrated that hostile media perceptions matter even though powerful predictors of contact were controlled for.

In addition, hostile media perceptions contribute to politicians’ dissatisfaction with the democratic performance of their political system by strengthening the belief that the public is not adequately informed about political matters. This result is perfectly in line with Tsfati and Cohen’s (Citation2005a) study that revealed the same effect for individual audience members. In addition to Tsfati and Cohen (Citation2005a), we were able to observe and compare the direct and indirect effects of media bias. Interestingly, there was no direct effect. Perceived bias led to dissatisfaction with democracy because politicians saw the danger of an ill-informed public audience. We believe this is an alarming finding. For individual citizens, the consequences of a disappointment with the functioning of democracy are likely to include a lack of participation and/or a rise of political cynicism. For political actors, however, the consequences of dissatisfaction with democracy may be much more severe; dissatisfaction with democracy can harm the political decision-making process, diminish the will to serve on behalf of the public interest, or decrease the allegiance to democratic norms.

Finally, hostile media perceptions also predicted the perceived effectiveness of conflict and drama as a means to sell information to the news media. That is, if politicians choose not to talk to journalists to deliver their message, they have to seek alternative strategies to ensure public attention. Conflict and drama is one such strategy, yet this strategy serves the media logic rather than the political logic (Strömbäck Citation2008). Therefore, by adopting this strategy, politicians may ultimately provoke what they—according to recent findings (e.g., Brants et al. Citation2010)—detest. By means of fostering the framing of politics in terms of conflict, the HMP may also contribute to the polarization of the media reality of politics, a development potentially eroding the quality of democracy.

It is worth repeating that the key outcomes of the HMP may be based, in part, on a mere perceptual error. That is, politicians who see the news against them may shy away from journalists and become skeptical toward democracy, although they may have no objective grounds to do so. This leads us conclude that the HMP increases the likelihood of misunderstandings between journalists and politicians. To reiterate, our findings indicate that ideology alone does not explain this process, only hostile media perceptions do.

There were also some other interesting findings. The effectiveness of conflict and drama was not related to satisfaction with democracy, neither directly nor indirectly (i.e., through the perceived media performance in informing the public). This contradicts findings from audience research (Mutz and Reeves Citation2005). In explaining this result, one could argue that conflict and drama are less problematic for politicians compared to audience members. Politicians are those who perform conflicts, so conflict and drama may be a habituated strategy. Citizens, in contrast, are those who observe conflicts and drama. Also, contrary to our expectations, contacting journalists did not increase the satisfaction with democracy. Rephrased, contact alone is not sufficient to inform politicians’ judgments about democracy (for similar findings, see Binder et al. Citation2009). It can be speculated that the specific characteristics of interpersonal communication with journalists—such as mutual understanding and respect—are more consequential in this context. In an additional regression analysis, therefore, we tested whether the effect of contact on satisfaction with democracy is moderated by the belief that the media adequately informs the public about politics. However, this interaction was not significant (b = .14, p = .51). It is not the case that contact increases satisfaction when politicians believe that the media do a good job.

The finding that high rank politicians, government members, and females were less likely to contact journalists compared to their respective counterparts, replicates results from previous research (Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011). Likewise, it is clear that strong ideologies lead to less satisfaction with democracy compared to weaker ideologies.

Alternative Explanations

One could argue that our observed relationship between hostile media perceptions and contact can be explained by the fact that politically extreme parties are, in reality, less likely to talk to journalists. However, this argument can be ruled out. As can be seen in , there was no direct effect of ideology extremity on contacting journalists. Compared to less extreme politicians, this means that politically extreme party members were no more or less likely to contact journalists per se. In contrast, they were susceptible to the HMP, which in turn, led them to refrain from contacting journalists. It follows that the HMP—not political extremity as such—drives contact behavior.

One may also argue that more extreme parties are treated more negatively in the media, and therefore, they perceive the media as hostile. However, we have not measured negative treatment in the media or objective media bias. By contrast, we measured ideological positions. The differences between respondent’s own ideology and the perceived ideology of the media is exactly what the HMP predicts (Vallone, Ross, and Lepper Citation1985): The more extreme an individual’s position is with respect to an issue, the more biased will this individual perceive the news media (Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004; Matthes Citation2013a). In our study, the more extreme politicians are in their ideology, the more distant they see themselves from the media.

Furthermore, there are grounds to question the causal order of the observed effect of hostile media perceptions on contacting behavior. It may be that contact leads to less hostile perceptions because it increases mutual understanding and respect. However, in defense of our model, we argue that there is an abundance of research indicating that contact per se by no means increases understanding and mutual trust (Binder et al. Citation2009). Also, we should keep in mind that the HMP is based on ideology which is a stable, trait-like construct. We believe it is unlikely that recent contacts with journalists can influence stable characteristics. By contrast, it seems likely that stable characteristics shape recent behavior. Of course, in order to prove this, we need panel survey data. Causal order cannot be assessed with cross-sectional models.

Implications

The finding that the HMP leads politicians to refrain from talking to journalists has potential implications for democracy and for journalism. If some politicians reduce their contact with journalists due to a perceived bias, the media may receive less substantial information about what these politicians do and, more importantly, why they do it. Politicians may then turn to alternative media sources, especially in the online world. This may, as a consequence, increase the likelihood of partisan media and echo chambers. Related to this, if some political actors receive less coverage because they reduce their contacts to the media, this may be noticed by the supporters of those politicians. The supporters, in turn, may become frustrated with the media as well, fostering hostile media perceptions among the audience. A democracy needs media representing a great variety of political viewpoints. This is a key condition for the public to trust the media. With respect to journalism, our findings suggest that journalists who wish to serve the public’s need for balanced information should avoid behaviors that make them look biased against particular views, because such behavior may exacerbate contact avoidance on the part of (a number of) politicians.

Furthermore, when politicians are not satisfied with democracy because they believe the media do not adequately inform the public, this may have negative implications as well. There are two issues: First, political elites may question the legitimacy of specific political institutions, or, when in government, even constrain political institutions as well as the news media. In short, if elites are dissatisfied with the system due to perceived bias in the media, they may try to limit the influence of the media when they are given the power. Although such conclusions are clearly beyond the scope of our data, there is now doubt that democracy can only work when politicians—who act on behalf of the sovereign in democracy—believe in it.

Limitations and Future Research

We have employed cross-sectional data as did most prior research on the relationship between politicians and journalists. To establish causal order, experiments would be the method of choice. Needless to say, conducting experimental studies with political elites is rather unlikely, if not impossible. Still, our survey-based approach to hostile media perceptions has important advantages in terms of external validity. Panel studies controlling the autoregressive effects of the dependent variables would be another alternative. However, given the common sample sizes of political elites and problems of panel dropout, the estimation of cross-lagged effects may not be possible. There is thus no alternative than to rely on cross-sectional data when studying political elites. Also, it is very important to note that the relationships we have observed between hostile media perceptions and contact and satisfaction with democracy are very strong and highly significant. It is thus unlikely that they entirely disappear when an auto-regressive effect of a prior state is controlled (i.e., in a panel study).

Since politicians have extremely limited time, we were only able to use single items for some constructs. It is important to note that the use of single items is very common in research on politicians (e.g., Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011; Brants et al. Citation2010; Van Aelst et al. Citation2008; Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011). More specifically, asking for political ideology as well as ideology of the media is straight forward and does not necessitate multiple items. As has been argued before, multiple items are not necessary if the attribute of an object is concrete (e.g., Bergkvist and Rossiter Citation2009). The same is true for satisfaction judgments (e.g., Nagy Citation2002), such as job satisfaction or satisfaction with democracy. Yet using single items is more problematic when it comes to perceived effectiveness of conflict and drama and the feeling that the news media adequately inform the public.

Of course, believing that conflict and drama is very effective in gaining attention is not a direct measure for the preference of conflict and drama. Although effectiveness and preference will be highly correlated, future research should work with more direct measures. More specifically, scholars should ask whether or not politicians engaged in conflicts to get attention, rather than employing a perceptual measure as we did in the present study. However, one drawback of such direct measures may be that politicians may not want to admit that they approve of using conflict and drama. Thus, the indirect measure we have used may also have advantages. Finally, although our sample of 199 politicians is as large as (and sometimes larger as the samples obtained in previous research (Aalberg and Strömbäck Citation2011; Brants et al. Citation2010; Van Aelst and Aalberg Citation2011), it would be beneficial to work with bigger samples. It is important to note that priority was given to the selection of top-ranking positions, while ordinary MPs were only included as replacements for top-ranking individuals. This explains differences to other studies that have sampled MPs only (Brants et al. Citation2010). Arguably, the higher the rank, the lower the response rate. Also, we have controlled the rank of the respondents in all analyses. Of course, larger samples and multiple items in each country are preferable. That would also help to determine measurement equivalence across countries (e.g., Matthes et al. Citation2012).

Considering that this study has documented the HMP in politicians, a number of conceptual follow-up questions can be presented. To begin with, we need to test classic theoretical propositions advanced in HMP research for political actors. This concerns, for instance, the question of the expected reach of a medium (Gunther and Schmitt Citation2004) or the role of affects in producing hostile media perceptions (Matthes Citation2013a). It would also be worthwhile to explore the consequences of the hostile media effects on politicians when they interact with journalists in social situations. Also, we need to explore if hostile media perceptions with mainstream media lead politicians to turn toward new and alternative media such as social media. Finally, whether journalists are aware of the bias perceptions of political actors and the effects these perceptions can have on journalists’ own behavior is another challenging, yet potentially fruitful, research question.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We used data from the project “Political Communication Cultures in Western Europe—A Comparative Perspective”, supported within the ECRP II program of the European Science Foundation and funded by FWF, FIST, AKA, DFG, MEC, VR, and SNF. We would like to thank the project coordinator, Barbara Pfetsch (Freie Universität Berlin), as well as Patrick Donges, and Fritz Plasser for the permission to work with these data.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The project was headed by Barbara Pfetsch who was also the Principal Investigator (PI) for Germany.

2. Because the information about the position of the respondent had to be separated from the rest of the data set to guarantee full anonymity, we are unable to provide the exact number of parliamentarians with leadership roles.

3. We also looked for country differences with a nested model comparison. This analysis compares a model without any constraints to a model that restricts a hypothesized path coefficient to be equal in all countries. With respect to hypothesis 1, the constrained model did not lead to a significant decrease in model fit. This indicates that the path coefficients do not differ significantly in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. This was also the case for all other hypotheses depicted in . This means that no country differences were observed. In addition, we also ran the model shown in controlling for country dummies. The findings remained the same. We additionally also tested the role of survey mode which varied between and within countries. Survey mode had no effects on our findings.

REFERENCES

- Aalberg, Toril, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2011. “Media-Driven Men and Media-Critical Women? An Empirical Study of Gender and MPs Relationships with the Media in Norway and Sweden.” International Political Science Review 32 (2): 167–187. doi:10.1177/0192512110378902.

- Altheide, David L., and Robert P. Snow. 1979. Media Logic. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

- Bergkvist, Lars, and John R. Rossiter. 2009. “Tailor-Made Single-Item Measures of Doubly Concrete Constructs.” International Journal of Advertising 28(4): 607–621. doi:10.2501/S0265048709200783.

- Binder, Jens F., Hanna Zagefka, Rupert Brown, Friedrich Funke, Thomas Kessler, and Amélie Mummendey. 2009. “Does Contact Reduce Prejudice or Does Prejudice Reduce Contact? A Longitudinal Test of the Contact Hypothesis among Majority and Minority Groups in Three European Countries.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96 (4): 843–856. doi:10.1037/a0013470.

- Blumler, Jay G., and Michael Gurevitch. 1981. “Politicians and the Press: An Essay in Role Relationship.” In Handbook of Political Communication, edited by Dan D. Nimmo and Keith R. Sanders, 467–493. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Brants, Kees, Claas H. de Vreese, Judith Möller, and Philip van Praag. 2010. “The Real Spiral of Cynicism? Symbiosis and Mistrust Between Politicians and Journalists.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 15 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1177/1940161209351005.

- Daniller, Andrew, Douglas Allen, Ashley Tallevi, and Diana C. Mutz. 2017. “Measuring Trust in the Press in a Changing media Environment.” Communication Methods and Measures 11 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1080/19312458.2016.1271113.

- Davis, Aeron. 2007. The Mediation of Power. A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Domke, David, Mark D. Watts, Dhavan V. Shah, and David P. Fan. 1999. “The Politics of Conservative Elites and the ‘Liberal Media’ Argument.” Journal of Communication 49 (4): 35–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02816.x.

- Elmelund-Præstekær, Christian, David N. Hopmann, and Asbjørn S. Nørgaard. 2011. “Does Mediatization Change MP-Media Interaction and MP Attitudes Toward the Media? Evidence From a Longitudinal Study of Danish MPs.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (3): 382–403. doi:10.1177/1940161211400735.

- Giner-Sorolla, Roger, and Shelly Chaiken. 1994. “The Causes of Hostile Media Judgments.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 30 (2): 165–180. doi:10.1006/jesp.1994.1008.

- Graber, Doris. 2003. “The Media and Democracy: Beyond Myths and Stereotypes.” Annual Review of Political Science 6 (1): 139–160. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085707.

- Gunther, Albert, Cindy T. Christen, Janice L. Liebhart, and Stella C.-Y. Chia. 2001. “Congenial Public, Contrary Press, and Biased Estimates of the Climate of Opinion.” Public Opinion Quarterly 65 (3): 295–320. doi:10.1086/322846.

- Gunther, Albert C., Nicole Miller, and Janice L. Liebhart. 2009. “Assimilation and Contrast in a Test of the Hostile Media Effect.” Communication Research 36 (6): 747–764. doi:10.1177/0093650209346804.

- Gunther, Albert C., and Kathleen Schmitt. 2004. “Mapping Boundaries of the Hostile Media Effect.” Journal of Communication 54(1): 55–70. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02613.x.

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini, 2004. Comparing Media Systems. Cambridge: CUP

- Higley, John, and Michael Burton. 2006. Elite Foundations of Liberal Democracy. Lanham, Boulder, New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Huge, Michael, and Carroll J. Glynn. 2010. “Hostile Media and the Campaign Trail: Perceived Media Bias in the Race for Governor.” Journal of Communication 60 (1): 165–181. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01473.x.

- Kepplinger, Hans M. 2007. “Reciprocal Effects: Toward a Theory of Mass Media Effects on Decision Makers.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 12 (2): 3–23. doi:10.1177/1081180X07299798.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2012. “The relationship with the media.” Unpublished manuscript., University of Zurich.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Sandra Lavenex, Frank Esser, Jörg Matthes, Marc Bühlmann, and Daniel Bochsler. 2013. Democracy in the age of Globalization and Mediatization. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Lehmbruch, G. 1996. “Die Korporative Verhandlungsdemokratie in Westmitteleuropa.” Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Politische Wissenschaft 2 (4): 19–41.

- Lijphart, A. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Form and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- Luhmann, Niklas. 1979. Trust and Power. Chichester: Wiley.

- Matthes, Jörg. 2013a. “The Affective Underpinning of Hostile Media Perceptions: Exploring the Distinct Effects of Affective and Cognitive Involvement.” Communication Research 40 (3): 360–387. doi:10.1177/0093650211420255.

- Matthes, Jörg. 2013b. “Do Hostile Opinion Environments Harm Political Participation? The Moderating Role of Generalized Social Trust.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25 (1): 23–42. doi:10.1093/ijpor/eds006.

- Matthes, Jörg, and Audun Beyer. 2015. “Toward a Cognitive-Affective Process Model of hostile media Perceptions: A Multi-Country Structural Equation Modeling Approach.” Communication Research. onlinefirst. doi:10.1177/0093650215594234.

- Matthes, Jörg, Andrew F. Hayes, Hernando Rojas, Fei Shen, S.J. Min, and Ivan Dylko. 2012. “Exemplifying a Dispositional Approach to Cross-Cultural Spiral of Silence Research: Fear of Social Isolation and the Inclination of Self-Censor.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 24 (3): 287–305. doi:10.1093/ijpor/eds015.

- Maurer, Peter. 2011. “Explaining Perceived Media Influence in Politics: An Analysis of the Interplay of Context and Attitudes in Four European Democracies.” Publizistik 56: 27–50. doi:10.1007/s11616-010-0104-3.

- Maurer, Peter, and Markus Beiler. 2017. “Networking and Political Alignment as Strategies to Control the News: Interaction Between Journalists and Politicians.” Journalism Studies, advance access.

- Maurer, Peter, and Barbara Pfetsch. 2014. “News Coverage of Politics and Conflict Levels.” Journalism Studies 15 (3): 339–355. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2014.889477.

- Misztal, Barbara. 1996. Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Moritz, Simon. 2010. “Political Support and Democratic Performance in Old and New Democracies.” In Democracy Under Scrutiny. Elites, Citizens, Cultures, edited by Ursula J. van Beek, 147–172. Opladen, Farmington Hills, MI: Barbara Budrich.

- Moyser, George, and Margaret Wagstaffe, eds. 1987. Research Methods for Elite Studies. London: Allan & Unwin.

- Mutz, Diana C., and Byron Reeves. 2005. “The New Videomalaise: Effects of Televised Incivility on Political Trust.” American Political Science Review 99 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051452.

- Nagy, Mark S. 2002. “Using a Single-Item Approach to Measure Facet Job Satisfaction.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 75 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1348/096317902167658.

- Nir, Lilach. 2005. “Ambivalent Social Networks and Their Consequences for Participation.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 17 (4): 422–442. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edh069.

- Nir, Lilach. 2011. “Disagreement and Opposition in Social Networks: Does Disagreement Discourage Turnout?” Political Studies 59 (3): 674–692. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00873.x.

- Oh, Hyun J., Jongmin Park, and Wayne Wanta. 2011. “Exploring Factors in the Hostile Media Perception: Partisanship, Electoral Engagement, and Media Use Patterns.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 88 (1): 40–54. doi:10.1177/107769901108800103.

- Pattie, Charles J., and Ronald J. Johnston. 2009. “Conversation, Disagreement and Political Participation.” Political Behavior 31 (2): 261–285. doi:10.1007/s11109-008-9071-z.

- Pfetsch, Barbara, ed. 2014. Political Communication Cultures in Western Europe: Attitudes of Political Actors and Journalists in Nine Countries. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rojas, Hernando. 2010. “‘Corrective’ Actions in the Public Sphere: How Perceptions of Media Effects Shape Political Behaviors.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 22 (3): 343–363. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edq018.

- Sellers, Patrick. 2000. “Manipulating the Message in the U.S. Congress.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 5 (1): 22–31. doi: 10.1177/1081180X00005001003

- Strömbäck, Jesper. 2008. “Four Phases of Mediatization: An Analysis of the Mediatization of Politics.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 13(3): 228–246. doi:10.1177/1940161208319097.

- Strömbäck, Jesper, and Peter van Aelst. 2013. “Why Political Parties Adapt to the Media: Exploring the Fourth Dimension of Mediatization.” International Communication Gazette, 75 (4): 341–358. doi:10.1177/1748048513482266.

- Tsfati, Yariv. 2007. “Hostile Media Perceptions, Presumed Media Influence and Minority Alienation: The Case of Arabs in Israel.” Journal of Communication 57: 632–651. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00361.x.

- Tsfati, Yariv, and Jonathan Cohen. 2005a. “Democratic Consequences of Hostile Media Perceptions: The Case of Gaza Settlers.” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 10 (4): 28–51. doi:10.1177/1081180X05280776.

- Tsfati, Yariv, and Jonathan Cohen. 2005b. “The Influence of Presumed Media Influence on Democratic Legitimacy: The Case of Gaza Settlers.” Communication Research 32 (6): 794–821. doi:10.1177/0093650205281057.

- Tsfati, Yariv, and Yoram Peri. 2006. “Mainstream Media Skepticism and Exposure to Extra-National and Sectorial News Media: The Case of Israel.” Mass Communication and Society 9 (2): 165–187. doi:10.1207/s15327825mcs0902_3.

- Vallone, Robert P., Lee Ross, and Mark R. Lepper. 1985. “The Hostile Media Phenomenon: Biased Perception and Perceptions of Media Bias in Coverage of the Beirut Massacre.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (3): 577–585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.577.

- Van Aelst, Peter, and Toril Aalberg. 2011. “Between Trust and Suspicion. A Comparative Study of the Relationship Between Politicians and Political Journalists in Belgium, Norway and Sweden.” Javnost – The Public 18 (4): 73–88. doi:10.1080/13183222.2011.11009068.

- Van Aelst, Peter, Kees Brants, Philip van Praag, Claes de Vreese, Michiel Nuytemans, and Arjen van Dalen. 2008. “The Fourth Estate as Superpower? An Empirical Study of Perceptions of Media Power in Belgium and the Netherlands.” Journalism Studies 9 (4): 494–511. doi:10.1080/14616700802114134.