ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant social distancing measures offer a compelling context through which to understand the changing relationship between journalism and place. Through an ethnography of news making at a major Indonesian news broadcaster, this study explored the material settings of news making during the pandemic and the consequences of the place-based realignments on journalistic practice, professionalism, and authority. Four main findings emerged. First, we found that as far as broadcast journalists are concerned there are no alternatives to the newsroom; making news in the newsroom was synonymous with their professional journalistic identity. A second finding is to highlight the key role of place in shaping press-source relations. In our case, the loss of physical proximity to government sources had major consequences for power relations between journalists and authorities. Third, certain news objects held particular meaning for journalists, and that when disrupted, can have deleterious consequences for their professional identity. Finally, our study witnessed an important shift in journalistic routines that favoured the live field report over pre-recorded packages or in-depth analysis. Findings are discussed in the context of ongoing debates about journalistic routines, identities, and the “material turn” in journalism studies.

Historically, journalists have faced disruptions to working conditions through wars, natural and man-made disasters, and health crises. In such situations, places including “where news-decision making occurs” and “the physical locations where reporting happens” (Usher Citation2019, 86) are forced to be realigned because they are not safe for journalists to work within or from. The COVID-19 pandemic shares many of these dynamics, but arguably accentuated due to its prolonged nature and associated social distancing measures that have directly affected the newsroom itself. The pandemic therefore offers an important context to investigate the changing “where” of journalism (Hallin Citation1986) which has often been overlooked in journalism studies literature.

This research aims to examine the changing places of news production from three perspectives: place as a “material setting of news,” as a meaning-making product by both journalists and sources, and as cultural, economic, and symbolic power (Usher Citation2019, 91). Theoretically, this study responds to calls to understand how the routines and practices of news production change when the places of news production are realigned (Usher Citation2019). It also responds to the need for more studies from inside non-Western newsrooms (Wasserman and de Beer Citation2009) in the pursuit of theory development. We address the research aim through a newsroom ethnographic study of a major national news broadcaster in Indonesia in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reporting Public Health Crises

Public health crises, ranging from “specific health issues, such as a disease outbreak in an otherwise unaffected community, to a full-scale disaster with property destruction and/or population displacement and multiple public health issues” (Bolton and Burkle Jr Citation2013, 210), have always been major news events, with journalists at the heart of the story. A rich body of literature focused on news content of public health crises from perspectives of, to name a few, the information, tone, and/or frames of news coverage (e.g., Ihekweazu Citation2017), the news construction of uncertain social risks (e.g., Chan Citation2016), and the representation of the “self” and “other” division (e.g., Joye Citation2010). Several studies also probed into journalistic practices when covering public health crises including struggles to conceptualise disease, news values, and conventions of outbreak reporting (e.g., Kim Citation2020), role perceptions of general and specialist journalists when covering health crises versus non-crises (e.g., Klemm, Das, and Hartmann Citation2019), the impact of specific routines and practices of news production on the health reporting (e.g., Thompson Citation2019), and the influence of news values on the news decision-making process when covering a pandemic (e.g., Hooker, King, and Leask Citation2012).

Early studies of the COVID-19 pandemic have mainly focussed on the financial difficulties of news media due to the cut of printing versions and the consequent lack of advertising revenues (Olsen, Pickard, and Westlund Citation2020), the inadequate public health reporting due to the shrinking press freedom and the prevalence of fake news (Bernadas and Ilagan Citation2020), the politicisation of this crisis in media representations (Tejedor et al. Citation2020), and the sourcing, framing, and tones of media representations of the pandemic prevention in Africa in Chinese and Western news media (Gabore Citation2020).

However, places of news production in public health crises coverage have rarely been given any attention in these settings. But one of the defining features of the COVID-19 pandemic is its disruptive impact on physical spaces, including newsrooms. This provides an important context through which to understand the dynamics of journalism and place.

Places of News Production and Journalistic Authority

Places of news production are closely associated with the symbolic power of the newsroom. Historically, the buildings in which news is made have been proximate to other places of societal power such as law courts, financial districts, government and police headquarters (Usher Citation2019). This is no coincidence, but instead represents both the utilitarian and symbolic value of being close to power. For instance, one of the central pillars of journalistic legitimacy lies in their access to news sources (Schmitz Weiss Citation2020; Usher Citation2015). Physical proximity facilitates both the formal and, crucially, informal networks that journalists rely on to glean information, get leads, and source stories.

People working within newsrooms are bound together by the place – its material settings - which “enables people to define themselves and to share experiences with others and form themselves into communities” (Rantanen Citation2009, 82). The division between the world where these “media people” work and the ordinary world has been naturalised and legitimised through, for example, restricting the access of “non-media people” to the sites of news production (Couldry Citation2000). Besides the symbolic meaning, physical newsrooms are necessary in maintaining journalistic professionalism through enabling in-person communications among news practitioners (Larrondo et al. Citation2016; Singer Citation2004). For instance, the physical arrangements of a newsroom can have profound impacts on the collaborative and creative practices of news production (Usher Citation2015). Here, research has examined the transformations of physical arrangements in newspaper newsrooms in countries such as the U.S.A (Robinson Citation2011; Usher Citation2014) and South Africa (Verweij Citation2009), witnessing the convenience brought by the physical closeness on news practitioners’ interpersonal communication, mutual respect, responsiveness to breaking news, and consequently, the enhanced productivity. Driven by the trend of platform convergence (Tapsell Citation2015), such innovations also happen in traditional television newsrooms. Here, news teams working in television are placed with those working in other areas in one centralised space to respond more effectively to the increasing demands of the news cycle. Moreover, a materialised newsroom equipped with high-tech production facilities draws news practitioners to the physical setting which can ensure their sense of professionalism and maintain the authority of the newsroom (Usher Citation2014).

Journalistic authority is maintained through their production of “credible and valid knowledge of reality” (Tong Citation2018, 258) as legitimate agents. Besides a tangible newsroom, reporting on or being near the scenes where news events happen is valued by journalists who can then “both claim authorship and establish authority for their stories” (Zelizer Citation1990, 38). To formalise their proximity to the places of news events, both newspaper and television reporting conventions include a place and dateline to refer to the scene where they report at the beginning or end of their coverage (Hallin Citation1986). News media also signify their professionalism via representation of the places where news events happen (Gutsche and Hess Citation2018). For television reporters, this comes in the visual backdrops that form the staple of this medium, but this also points to the importance of photojournalism for denoting place (Zelizer Citation1992). Even digital news reporters find ways to claim authority by producing digital cartography based on their in-depth understanding of news narratives (Usher Citation2020).

This is important when we consider journalism’s relationship with the geographical communities they typically serve. Place is central to both how news organisations see themselves (consider the number of newspaper titles with place names) and how they connect with their audiences. As foundational journalism studies research has shown, news organisations help foster a sense of community, belonging and shared norms related to a place in the world, and define what it means to be “local” (Gans Citation2004; Park Citation1923). For Usher (Citation2019), knowing places better than laypeople is a central source of journalistic trust and authority.

Place-Based Realignments in the News Industry

The changing political economy of news production has had important ramifications for journalism’s relationship with place. On economic grounds, for instance, many news organisations have cut back on permanent foreign bureaus, which have consequences for what people learn about certain places (McChesney Citation2015). The economic decline of newspapers has led, in some cases, to the relocation of the entire newspaper production from grand town centre buildings to smaller offices away from town and city centres (Usher Citation2015, Citation2019). Through a case study of The Miami Herald, Usher (Citation2015) showed how changes of the material and geographical setting of the newsroom had consequences on news coverage routines, such as longer commuting time to the newsroom and proximity to sources. These shifts in news production resulted in less influence of the newspaper in covering major subjects such as city policy, which ultimately weakened their connection to readers (Usher Citation2015).

At the same time, technology is having profound effects on journalists’ relationship with place. On the one hand, mobile technologies have enabled ordinary citizens to become more involved in the production of place-based knowledge (Goode Citation2009), which might be seen as a challenge to journalistic authority. On the other hand, news organisations are now also utilising such technologies as interactive maps, VR, and drones; which might provide journalists with the opportunity to reassert their knowledge of place (e.g., Wemple Citation2014; Usher Citation2019). New technologies also enable newsrooms to become increasingly dis-placed and virtual, with journalists (theoretically) being able to work from anywhere. Fort Worth’s Star-Telegram, for example, envisioned a totally virtualised news gathering and production routine with the physical newsroom discarded altogether (Usher Citation2014). Such phenomenon has led some scholars (e.g., Boczkowski Citation2015; Zelizer Citation2017) to question whether the materialised newsroom should remain the focus of journalism studies scholarship.

Where some online news organisations and newspapers are increasingly able to run a virtual newsroom, for broadcast news production, their reliance on material settings (the studio) and key technologies (e.g., high-quality cameras, specialist editing hardware) suggests that the newsroom may maintain its key role. However, whether broadcast news is undergoing place-based realignments is understudied in relation to other news media. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a potential displacing effect unlike other contexts studied before. Finally, the growing body of literature on the places of news making has overwhelmingly focused on Western newsrooms (e.g., Robinson Citation2011; Usher Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2019). Resultantly, we know very little about those in any non-Western context.

This study addresses the above gaps through an ethnography of news making in an Indonesian news broadcaster in the context of the pandemic. Our research questions are informed by Usher’s (Citation2019, 91) framework for understanding place in news production which takes account of (1) “Place as the geographic and material setting of news,” (2) “Place as lived: where action and meaning is made,” and (3) “Place as cultural, economic, and symbolic power.”

RQ1: How were the material settings of TV news production altered during the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ2: What impacts did these changes have on the lived experiences of TV journalists? And what new news making routines emerged during the pandemic?

RQ3: What were the consequences of the reconfiguration of places of TV news production for journalistic conceptions of cultural and symbolic power?

Context: Journalism in Indonesia

The development of Indonesia from an authoritarian regime into a largely successful democracy since the fall of President Soeharto in 1998 helped to liberate Indonesia’s media (Tapsell Citation2015). Several key developments in the Indonesian press history in the post-Soeharto era further contributed to the media freedom in the country, including the passage of the Press Law No. 40/1999 and Broadcasting Law No. 32/2002 which ensured citizens’ freedom of expression and speech, the reformation of the Press Council into an independent regulatory body, and the oversight of press freedom by professional (e.g., Alliance of Independent Journalists) and civil society (e.g., Tifa Foundation) organisations (Nugroho, Siregar, and Laksmi Citation2012).

Although the media industry in Indonesia has transformed from being controlled by the government to a relative liberated domain from the late twentieth century (Ekayanti and Hao Citation2018), governmental influence on journalistic autonomy can still be observed through, for example, journalists’ self-censorship (Kwanda and Lin Citation2020) and interventional practices on journalists as a result of political ownership (Ekayanti and Hao Citation2018). For example, to debunk the 2018 post-Palu disaster fake news, Indonesian journalists would wait for corresponding governmental responses instead of being independent and immediate in providing their own knowledge or referring to experts (Kwanda and Lin Citation2020). The combination of the increasing press freedom alongside the legacy of governmental influence (Lehmann-Jacobsen Citation2017) can perhaps explain the inherent paradoxical role perceptions among Indonesian journalists. Journalists in Indonesia highly value objectivity and precision in their news production which is the widely accepted norm in international journalism practice, but much less on their role of holding the government accountable (Hanitzsch Citation2005). Instead, they tended to partner with the government in putting forward the national development agendas (Pintak and Setiyono Citation2011).

Newsrooms in Indonesia are undergoing platform convergence, with television news now increasingly being merged with online platforms into one digitalised multiplatform (Tapsell Citation2015). This trend is accompanied by the transformation of TV broadcasting itself, i.e., the analogue-to-digital switchover, which started in 2011 (Ambardi et al. Citation2014). While other news media, such as newspapers and radio have witnessed trends of decline, TV is still dominant in the Indonesia media market (Tapsell Citation2015).

Method

Our study focuses on a major Indonesian broadcasting organisation, SCTV, based in Jakarta. SCTV is one of the two largest private national television stations in Indonesia and ranks at the top of the “most watched news programs” according to Nielsen for its flagship news program “Liputan 6” (which loosely translates as “The 6 Report”) (Ambardi et al. Citation2014, 23). SCTV has undergone digital convergence with Liputan6.com which is one of the five biggest online news portals in Indonesia based on Alexa rank in 2020.

The data provided here is obtained from ethnographic methods by relying on observations (recorded both visually and textually), interviews, company documents, and participant diary entries. Ethnography - widely used in the journalism studies field - focuses on understanding what people believe and think, and emphasising what people actually do within their own environment (Fetterman Citation2019; Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). All of the data was collected by the first author (though for consistency, we refer to “we” throughout the Method and the Findings sections). We used pseudonyms to ensure the anonymity of our participants.

On-Site and Online Observations

The observations were conducted in two ways, involving on-site and online observations due to the constraints resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak. We observed every one who was in the newsroom on the day of observation, including reporters, editors, production support, camera crew, and video journalists. The on-site observations were conducted in May and August 2020 and lasted for 21 days (approximately 150 h of observations). Most observations were conducted during the day shifts and occasionally, the night shifts. We had access to all parts of the newsroom to observe the daily production routines, and were frequently present at the studio as the news aired. We attended as many editorial meetings as we could, as well as meetings with the programming department and the research and development team. As for the online observations, we observed the newsroom for two weeks (approximately 30 h of observations) in April 2020 at the peak of the pandemic. These observations were mostly of editorial meetings, as well as smaller team meetings. Since most of the data were gathered through participant observation, the researcher tried to remain as an impartial observer and did not participate in the work itself. However, we participated in several informal work-related discussions, both within and outside the newsroom.

Interviews

Typical for ethnographies, we conducted two types of interviews (Fetterman Citation2019; Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). First, we conducted unstructured interviews with around 30 TV journalists, including camera crew, reporters, and editors during the observation (ranging from junior reporters to senior editors). These interviews were informal and were not recorded but kept in fieldnotes. Second, we conducted semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide with a total of 16 journalists and editors (again ranging from junior to senior roles). Each interview lasted around 45 min. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Fieldnotes, Diaries, and Supporting Documents

We kept detailed field notes of our daily interactions with the journalists, observations, and personal experiences during the fieldwork. However, we avoided making notes on a continuous basis while engaging with participants to prevent unnatural responses (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2007). We also asked participants (one reporter and four editors) to keep diaries (once daily entries) for two weeks in April 2020 to reflect on their experiences of covering the pandemic and their daily news routines. Finally, we took 35 photos and 60 min of video recording in newsrooms and galleries, and also collected then analysed internal documents such as news bulletin rundowns. Overall, these materials constituted more than a hundred pages of documentation transcripts and notes in Indonesian which were then translated into English, and imported into NVivo 12 qualitative software for analysis.

Data Analysis

All authors were involved in data analysis. We used manual interpretive coding which included a process of open coding, identification of major thematic categories, management of sub-categories, and development of dominant themes. Following these procedures, a closer reading of themes took place in a process of meaning condensation (Coffey and Atkinson Citation1996). Themes were discussed between the authors as “critical friends,” providing a point of reflection of interpretations.

Findings

The Power of the Newsroom

The observed TV newsroom and the studio is situated on the 9th floor as a part of the 22-storey SCTV headquarters in the middle of the city centre. The spacious open-concept newsroom sits in the floor’s centre, which is typical of a TV production site. A total of 260 staff, 140 from SCTV and 120 from Indosiar (another television network), shared the same floor. During normal times, 135 staff (SCTV = 70, Indosiar = 65), working on a shift basis, would occupy the newsroom at any one time. During the pandemic, this never exceeded 65 staff (SCTV = 35, Indosiar = 30), and was frequently considerably less.

When we came to observe the newsroom with a size of about 2000 square metres, it was almost empty. Multiple tables packed with computers arranged next to one another were also vacant. Only two places, the producers’ desks and the groups of assignment editors, were bustling. Before the pandemic, the newsroom was full of visitors on a daily basis who came as either guests for a news show or as guests going on a studio tour. During the outbreak, outsiders or “non-media people” were not allowed to enter the newsroom because of safety issues. Rey (Deputy Chief Editor) said that now there were no people from outside of the newsroom who were excited to visit the newsroom and no invited guests who were nervous or even intimidated before the interview. For her, the symbolic meaning associated with physical co-presence in places of news was waning, “it feels like we lose our pride.”

Besides the symbolic power, our participants emphasised the necessity of a materialised newsroom in maintaining professionalism. The reconfiguration of the newsroom created anxiety and tension among journalists. Rey (Deputy Chief Editor) said that “we know how important the newsroom is for journalists. It was difficult when we had to reduce the team and it was kind of chaotic and daunting to not be in the newsroom and to start working from home.” Cinta (Senior Producer) analogised a newsroom as a kitchen, a place to cook and prepare the best dishes. “I can’t imagine, without a newsroom, how we will treat content properly?”

One of the key consequences for professional news production due to a lack of a physical newsroom was the disabled in-person communications among news practitioners, which negatively impacted newsroom productivity. Journalists usually relied on physical interactions and robust discussions on which story, headline, or picture to be included before the pandemic. Now the scenes full of hustle and bustle were nowhere to be seen. One of the biggest challenges resulting from digital-only communications is that practitioners could not discuss topics in an in-depth way, debate something controversial, or involve sensitive content due to the concern of security. This finding was consistent across different teams ranging from producers to journalists. “Why do we need the newsroom? Because we need a place to discuss our ideas, to argue, to debate. This is the right place to find the way to make good news. Here from our desks, or there,” Carlo (Executive Producer) pointed to the meeting room. Similarly, Sonny (Coordinator of Assignment Editors) said, “This is what the newsroom is for. As an assignment editor, I argue a lot with the producers, and the newsroom is the best place to solve our problem.” Echoing Carlo and Sonny, Andy (Video Journalist), although assigned to cover news at the President’s office and working mainly on his own, said sometimes he needs to discuss and brainstorm with the assignment editors and producers in person, particularly when there were new policies from the President or latest issues from the government.

Instead of fostering ideas to ensure the quality of journalism, the newsroom could not even guarantee functional meetings due to a lack of in-person communication. Our observation in a special programme meeting witnessed the bumpy communications among participants. “We don’t know what people do when they don’t use their camera during the online meeting. They may be busy doing something else, not following our conversation,” said one of the producers. This unproductive online meeting reflected the fractured TV production process that heavily relies on teamwork. For example, the newsgathering team which serves as the foundation of the news production was now penetrated with various sentiments because of being relocated out of the central newsroom to another building. Rey (Deputy Chief Editor) said that some of the members of the newsgathering team were not happy and some even felt “dumped.” Meanwhile, many reporters stated that they were fine operating in a different location from the headquarters. “I enjoy this newly found freedom because I have no pressure from assignment editors and producers,” said Diva and Ken (Reporters). These mixed feelings about the reconfiguration of the places of working may act as reasons, excuses, or disguises for lack of engagement in the production, which was not an issue for in-person communication enabled by a centralised physical newsroom.

The professional news production was disrupted also because of the limited access to the in-house high-tech facilities for a period of time, which caused frustration among some news practitioners. This was felt most acutely by the production team. The biggest hurdle experienced by the newsroom was to put the show on-air. The production team used to work in a digitally connected and contained work environment where they can preview videos and check on graphics in a straightforward way. But when working from home, “It’s impossible to work without access to the necessary equipment and facilities that are only available in the newsroom,” said Dede (Producer). The makeshift nature of the home-made studio and the low quality of the visuals lessened the professionalism of the shows. Dede (Producer) stated that they can no longer sustain the higher technical standard than their print or online peers, which used to be a source of their esteem.

Going Live

Unsurprisingly, COVID-19 stories dominated the news agenda during the study period. Our analysis of Liputan 6 rundowns found that up to 90 percent of stories between February and May 2020 were about the pandemic, falling to around 60 percent from May to August. Gathering news from the field was still the dominant practice for around 70–80 percent of news content through the pandemic, but there was an important shift towards live stand-up segments. Throughout the observation in the SCTV control room, four to five reporters were ready to go live from different locations every day. Practitioners in different roles were consistent in recognising the necessity of live coverage from the sites of news events. Rey (Deputy Chief Editor) said, “Live report is the trademark of TV news; a kind of signature. This makes us different from the news agency.” Similarly, Dinno (Executive Producer) said, “Whenever we send reporters overseas, one of the important things they need to do is to look for a decent place to go live. Well, you might say it’s a show off. But I can say, it’s our power, our identity.”

Despite the personal safety issues imposed on live reporters, Dinno believed in the necessity of live reporting of the pandemic, “The reports on coronavirus are unpredictable, and what’s going on with the COVID-19 story is complex. So, the best way to deliver news is with a live report.” Similarly, Cinta (Senior Producer) said that “Coronavirus is a big enough story that the newsroom gets on it quickly. At the beginning, we had a big fight with the assignment editor manager to send the reporter to do live but then we realised the importance of sending reporters to do live.” It is questionable whether sending so many journalists to do live reports during an outbreak was a responsible decision, as several journalists contracted the virus when reporting from the field. Nevertheless, while some reporters resisted the idea of live coverage at the beginning of the pandemic, in the end they were convinced of its utility: “I think that’s what TV journalists are doing: performing live from the location, reporting real time, speaking to people in front of the camera,” said Renata (Reporter).

The TV editors strongly believed that real-time news coverage is of higher value compared to a pre-recorded story package for three main reasons. Firstly, having journalists on the sites of news events as witnesses can ensure the credibility of the coverage. Diva (Reporter) mentioned that “For me reporting live means reporting the facts. We want to share with our viewers what is going to happen. No fake news here because we are in the location, and the visual is real.” Secondly, the closer the proximity of the reporter to the event locations, the more poignant and immediate the impacts are to the audience, with higher ratings as a result. Sonny (Coordinator of Assignment Editors) said, “We have to send reporters to the field, going live on location regardless of the news, be it regular news or breaking news. In fact, the audience likes it and the rating is good.” Thirdly, in light of the decision to extend the flagship news program from 30 min to one hour (from March to mid-August), live news offered an easy way of filling airtime within the available resources.

Despite the high importance the newsroom placed on live reports during the pandemic, our study observed that most of the live reports were descriptive, speculative, and un-analytical, and were typically delivered by junior reporters. Live updates typically took place in the same handful of locations, including hospitals, quarantine houses, markets, airports, malls, and the subway. The content of the live reports was the same almost every day, with reporters updating the cases of COVID-19 infection and deaths, along with a brief eyewitness report of the surrounding environment. Reporters said that they just need to slightly change and update both the angle of the report and the data and then summarise the story.

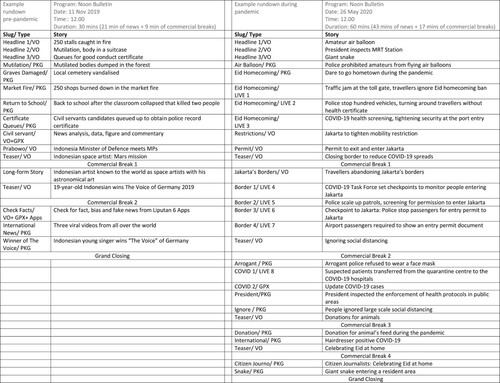

To illustrate some of these changes, particularly the shift towards live reports, shows two typical news programme rundowns from 2020 (mid-pandemic) and 2019 (pre-pandemic). With many human resources absorbed by the live reporting operations, fewer capabilities could be devoted to covering in-depth and analytical stories, which were typical of their programmes prior to the pandemic. While shows a similar number of news packages, there were qualitative differences between pre- and mid-pandemic packages. During the pandemic, packages were considerably shorter, had little analysis and seldom used data, figures and graphics, as these require newsroom system equipment. Moreover, we discovered that the investigation and documentary unit had been disbanded since the pandemic, and the journalists were moved to daily news beats. According to Jacob (Senior Journalist), apart from no longer being able to cover outside the region due to travel restrictions, they were considered to be a burden in the newsroom because investigative and documentary units are costly. Jacob suspected that management used the pandemic as an excuse to take this decision.

Source Dependency and Press-Government Relations

During the pandemic, Indonesian journalists - like their counterparts across the world - were particularly reliant on the government and official sources for information. Journalists mentioned that they had suffered restrictions from the government in accessing information since the outbreak started, and had faced growing difficulties in contacting officials. Journalists described the outbreak as a “comfortable time” for the government to not speak to or communicate with journalists in person. As the source of news became centralised, the authorities became more dominant and controlling of the news, and journalists had a fight to remain relevant. These changing power relations were as a direct result of changes in the material settings of press-government interactions brought about through COVID-19.

Journalists’ loss of on-site presence in government buildings was translated into their restricted access to ministers and other officials. This was compounded by the safety policy established by the newsroom since the beginning of the pandemic that barred guests, including the governmental officials, from the SCTV news studio. The information on every outbreak update, including regulations, treatments, and policies, was conveyed to the press in a one-way manner by a spokesperson of a special task force and committee for COVID-19 created by President Joko Widodo. Where our participants were granted access, the interview was often in the form of written questions, sent in advance, for ministers and spokespeople who were free to answer or ignore in their live briefings. Moreover, for a time, relevant press conferences could not be directly attended due to physical distancing regulations but could only be watched online.

Our participants gained access to officials through digital platforms such as Zoom, Skype, and WhatsApp but mentioned the difficulties of getting satisfactory responses. Carlo (Executive Producer) said, “It’s easy to get access to online Zoom or Skype interviews with government officials to talk about their policy or publish their campaign. But it’s difficult to approach them when it comes to a sensitive or controversial issue, and we need to be persistent.” He added, “During the pandemic, we can only wait for the government to respond from WhatsApp; sometimes we’re nervous when it comes to the deadline.” Indira (Assignment Editor) also said, “We can’t send a reporter during the pandemic to chase government sources to make sure they’re willing to appear on the screen.” Consequently, journalists had limited opportunities to interact with official sources, in particular, asking them questions and holding them to account.

The lack of physical contact between journalists and their official sources transformed into a practice that allowed untested and unchallenged information. Before the outbreak, it was common for journalists to chase their prime news sources (often literally down the street) until they got answers. Or, during press conferences, journalists might counter the official statements with data or facts they found on the field. If the sources tried to avoid questions, door-step interviews allowed journalists to ask for answers to their sources or insist on a response. Now, it was “more press releases, press conferences, less real reporting,” said Nadia (Assignment Editor). The consequence of this physical reorientation of press-source relations was that politicians and officials were more able to evade scrutiny from the press. Although some journalists attempted to verify the government information, the highly centralised and filtered information frustrated our participants: “We are not PR, but most of the time, we end up with a spokesperson as our source,” said Cinta (Senior Producer). Some participants felt quite powerless to change this: “we are frustrated, we are disappointed, but what can you say?” said Carlo (Executive Producer). More worryingly, some talked of abandoning their public service role: “Sometimes I prefer to make a funny story rather than stories from the government” said Ferdinand (Senior Producer).

Reclaiming Authority

Amidst the lingering pessimism of government control over the flow of information, journalists at SCTV found ways to remain relevant and assert their own place-based authority, especially in managing their relationship with the audience. Crisis events often see spikes in the use of citizen material by journalists, as they are not able to witness the events themselves (Allan Citation2013; Goode Citation2009). In our case, early in the pandemic the TV station created a team responsible for obtaining stories from citizen journalists. This team encouraged its journalists to find information and conduct interviews through digital channels such as video-call applications, or by asking the sources to send their answers through self-recorded videos. But from June onwards, citizen journalists’ reports have rarely been aired because most of the stories were not deemed suitable to be broadcasted. Rey (Deputy Chief Editor) explained that “We did spend too much time verifying and confirming the information. We also often asked them to retake, gave the guidance, and asked a lot to improve pictures and stories. Now we broadcast citizen journalists’ stories only if there is something unique and new from their stories. We need to be more selective.”

The decision on the reduced reliance on audience materials forms a part of a wider assertion of authority and boundary marking over other forms of news content that lack the production values and journalistic processes of TV news. Journalists were aware of the changing news and information landscape, particularly during the pandemic, where there is too much information circulating, often mixed with verified news and hoaxes. “So, the TV audience … or even digital/online audience they will always ask if the information is on TV yet or not. If not, they won’t fully believe in what’s online,” said Indra (Assignment Editor). During our observations, Indra reminded the team to strengthen their competence in verification, clarification, and confirmation of information. Alongside their move away from audience materials that lacked TV production values, this was an assertion of the unique authority that a professional newsroom could bring in order to remain relevant. Moreover, in terms of deciding news agendas, the newsroom tried not to be swayed by the content on social media. Sonny (Coordinator of Assignment Editors) said that “Up until now, if I am on duty, I focus on official info. But on what is trending on social media or personal matters and all, no.” Even though sometimes the TV coverage lacked novelty or compelling visuals, our participants valued their role as credible informants which, for them, was endorsed by rising viewing figures during the pandemic.

Besides setting a clear division between professional newsroom production and public materials, another attempt to reclaim the newsroom’s place-based authority came in the forms of making professional live reports. During the pandemic, the team started to use more 4G streaming equipment for live location reports which replaced the Satellite News Gathering (SNG) truck. The latter operation involved up to ten people and a large truck carrying heavy equipment. In comparison, the 4G streaming alternative could be delivered with just a two-person team and backpack-sized equipment; and therefore, fewer people needed to go outside during a pandemic when producing the same output. For many in the newsroom, having a smaller team to do the same task sounded like progress. However, some practitioners believed that using SNG meant better quality pictures and a more stable connection, even though the quality of 4G streaming equipment is improving. “SNG van is like our outside office, we can work there, edit the footage, and send the picture to the office,” said Ken (Reporter). Now the SNG was seldom used. “During this pandemic we only use SNG to make a national TV pool and we have a national broadcast forum now. One TV will be the one on duty, each TV is assigned to standby in a certain area/venue, so every TV station will receive the same material from one source,” said Indra (Assignment Editor). In normal times, this pooling of material resources amongst rival TV news companies rarely happens. While our participants accepted it in the circumstances, it was clearly a sore subject. Some TV journalists reminisced about appearing on the field with their big truck decorated with their media logo. For them, the SNG truck meant more than just producing news items with good sound and picture quality; it was a statement of their professional status. A number of participants spoke about how having SNG trucks from various news brands lining up on the sites of news events gives validation to TV journalists when working on the field. Alex (Field Producer) said, “It (SNG) represents us as TV people in many big events.”

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant social distancing measures offer a compelling context through which to understand the changing relationship between journalism and place. Through an ethnography of news making at a major Indonesian news broadcaster, this study explored the places of news making during the pandemic and the consequences of the place-based realignments on journalistic practice, professionalism, and authority.

Our findings showed that the established material settings of news production were forced to be reconfigured in order for journalists to remain safe from infection. Some journalists made news packages from home and the newsroom became half-deserted, with small teams working shifts. While reporters could still maintain some routines such as reporting from location, they were reliant on inferior equipment (as they saw it). Access to key sources – particularly government – was curtailed. What runs through these findings is how profound the consequences of some of these reconfigurations were for journalistic routines, professional identities, and perceptions of journalistic authority.

First, while some have recently questioned the centrality of the newsroom as a site of journalistic work and focus of academic study (e.g., Boczkowski Citation2015; Zelizer Citation2017), our study demonstrates that as far as broadcast journalists are concerned, there are no alternatives to the newsroom. On pragmatic grounds, a physical newsroom was seen as essential for fostering a productive working environment (see also Usher Citation2014, Citation2015). Findings show that while editorial meetings could be conducted online, meaningful and constructive communications among the practitioners were lost in the process. But the shortcomings of dis-placed news making were also symbolic. For many of our participants, making news in the newsroom was synonymous with their professional journalistic identity. They also spoke of how the newsroom lost its aura when it was no longer bustling with journalists, guests, and other media people. This is telling, because it suggests that the symbolic power of a newsroom does not just come from its material settings (its location, architecture, and physical layout, etc.) because these have not changed during the pandemic. Instead, it reminds us that the symbolic power of places is also constructed by the people who occupy them, and when these dynamics undergo major disruption, a place can quickly lose its aura (see Couldry Citation2000; Papacharissi Citation2015).

A second key finding is to highlight the key role of place in shaping press-source relations. As previous research has established, physical proximity to power is of the utmost importance to journalists, and throughout history news organisations have sought to locate themselves amongst powerful people and institutions (Schmitz Weiss Citation2020; Usher Citation2019). Where news organisations have put physical distance between journalists and such institutions (often on economic grounds), scholars have openly worried about their consequences for democratic accountability (McChesney Citation2015; Usher Citation2015). Although the news industry’s heavy dependency on governmental and official sources has been widely identified in previous studies from the perspectives of, for example, news routines, time pressure, and censorship, particularly during crisis events (e.g., Thorsen and Jackson Citation2018), our study showed how the dependency is particularly tied to physical proximity. As we documented, social distancing measures brought about through the pandemic had profound implications for press-government power relations. The loss of physical presence on sites of news reporting when covering governmental and official issues severely diminished the fourth estate role of Indonesian journalists – something they were seemingly quite powerless to prevent. Such findings demonstrate how delicate and finely balanced these power relationships are. They also raise further troubling questions that future research might explore: not least, whether press-government power relations in Indonesia ever fully return to pre-pandemic status, or have been led to a real setback by the pandemic; and to what extent other countries have undergone similar tilts towards government information control since the pandemic.

Equally interesting were the ways that journalists reasserted their symbolic power, and their relationship to material settings. Here, certain objects held particular meaning – our third key finding. Our participants were demonstrably able to produce news reports via 4G streaming equipment - equipment that would be considered state-of-the-art by non-broadcast journalists producing video content. However, their strong preference for SNG trucks, with editing facilities, better cameras, and company logos emblazoned on the side, perhaps reveals a particular occupational ideal of broadcast journalists. Their access to the unique material objects of broadcast news – such as the professional broadcast camera – is what separates them from other journalists. When they are made to use the same news making objects as non-broadcast specialists, it is a dent to their professional esteem. Amidst the “material turn” (Boczkowski Citation2015) in journalism studies that brings more attention to the broad spectrum of actors implicated in news making, the spatial distribution of places, and the role of technologies in the creation of news, little research has focussed on the material objects of broadcast news. Our findings demonstrate that when some of the meanings attached to certain legacy news objects are disrupted, they can have deleterious consequences for journalists’ professional identity.

Finally, our study witnessed an important shift in journalistic routines that favoured the live field report over substantial pre-recorded packages or in-depth analysis. As previous research has shown, liveness is especially essential for television broadcasting to establish its unique status in the news media industry, particularly during crises or other major news events (Berkowitz Citation1992; White Citation2004). For our participants, going live met a number of professional, commercial, and practical imperatives. However, there are temporal, material, and normative dimensions of these shifts in routine that are worthy of further discussion. Being live at important locations relating to the pandemic was important to our participants and it placed them as connected to the national community that they serve. However, the nature of the pandemic (with no physical epicentre, no visible spectacle, and a relatively slow unfolding of events) meant that while the journalists may have been live from a particular location, they were not witnessing any kind of live event. Here, journalists may be accused of failing to adequately understand the places from which they report (see Usher Citation2019). As some scholars argue, the places of live reporting often represent journalism’s attempts to illustrate and embody abstract issues as eyewitnesses, in a bid to establish their credibility and authority (Huxford Citation2007; Scannell Citation2014). But where a reporter is live from a location that does not coincide with an event that is actually unfolding, Huxford (Citation2007) argues that this represents no more than a delusion of proximity that serves to perpetuate a sense of placelessness.

In our study, the disruption of the places of news production, especially the newsroom, resulted in a slower newsroom working pace where fewer stories were being made. At the same time, the main news bulletin was extended by 30 min. With the associated reliance on live reports from the field, the result was – we would argue – more news content but less journalism. Here, the viewing public were subject to live pieces from the field to give the feeling of constant newness amid the unfolding events. But behind the scenes, the newsroom was operating well below capacity, with relatively little original newsgathering taking place. Such observations demonstrate a potential paradox of news temporality. Previous work on rolling broadcast news reporting has documented an obsession with liveness, speed, and a competitive desire to break the news first, often at the expense of accuracy and depth (Lewis and Cushion Citation2009; Rosenberg and Feldman Citation2008). This is often described – quite accurately – as fast journalism (Le Masurier Citation2015). But where there is lots of airtime taken up by live reports, but not much news actually broken, the news takes on a different temporality, which we would not characterise as fast.

Conclusion

In the emerging sub-field of geographies of news (see Reese Citation2016), our study demonstrates both the significance of the material settings of news, and reveals some of their complexities and contradictions in practice. Where recent work has examined the place-based realignments of newspapers and online newsrooms (Robinson Citation2011; Usher Citation2014, Citation2015), our study shows the value of examining different types of newsrooms. Here, we found that broadcast news retains some unique relationships with material objects (such as broadcast production facilities) and a working culture that favours physical proximity. As a field, we are only just scratching the surface of these relationships, and further empirical research should explore these dynamics in other under-researched news settings such as radio. Furthermore, while our study has expanded the study of journalism and place beyond Western newsrooms, we would hesitate to generalise to other contexts. Instead, we would press for further research – particularly in non-Western settings – where there is little work in this area. Given the material disruptions of the pandemic on newsrooms across the world, we would argue that this now gains greater urgency.

Returning to the pandemic, our study suggests that as far as news making is concerned, viewing the pandemic through the standard lens of public health crisis news reporting might not be productive. Compared to previous pandemics, the level of and prolonged disruption to news making processes makes this context quite unique. Existing knowledge of news production during public health crises is based on contexts where the newsroom has remained intact. To take a biological analogy, we are now beginning to learn how the body functions when its heart – the newsroom – is impaired. There are normative and democratic consequences of this that we will only fully understand over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allan, Stuart. 2013. Citizen Witnessing: Revisioning Journalism in Times of Crisis. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Ambardi, Kuskridho, Gilang Parahita, Lisa Lindawati, Adam Sukarno, and Nella Aprilia. 2014. Mapping Digital Media: Indonesia. Open Society Foundations. https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/55b62da84.pdf.

- Berkowitz, Dan. 1992. “Non-Routine News and Newswork: Exploring a What-a-Story.” Journal of Communication 42 (1): 82–94.

- Bernadas, Jan Michael Alexandre C., and Karol Ilagan. 2020. “Journalism, Public Health, and COVID-19: Some Preliminary Insights from the Philippines.” Media International Australia, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20953854.

- Boczkowski, Pablo J. 2015. “The Material Turn in the Study of Journalism: Some Hopeful and Cautionary Remarks from an Early Explorer.” Journalism 16 (1): 65–68.

- Bolton, Paul, and Frederick M. Burkle Jr. 2013. “Emergency Response.” In Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice, edited by Charles Guest, Walter Ricciardi, Ichiro Kawachi, Iain Lang, and Third Edition, 210–221. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chan, Chi Kit. 2016. “Defining Health Risk by Media Template: Hong Kong’s News Discourse of the Swine Flu Pandemic.” Journalism 17 (8): 1018–1036.

- Coffey, Amanda, and Paul Atkinson. 1996. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies. Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, and London: Sage.

- Couldry, Nick. 2000. The Place of Media Power: Pilgrims and Witnesses of the Media Age. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ekayanti, Mala, and Xiaoming Hao. 2018. “Journalism and Political Affiliation of the Media: Influence of Ownership on Indonesian Newspapers.” Journalism 19 (9–10): 1326–1343.

- Fetterman, David M. 2019. Ethnography: Step-by-Step. 4th ed. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, and Melbourne: Sage.

- Gabore, Samuel Mochona. 2020. “Western and Chinese Media Representation of Africa in COVID-19 News Coverage.” Asian Journal of Communication 30 (5): 299–316.

- Gans, Herbert J. 2004. Deciding What’s News: A Study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and Time. 2nd ed. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Goode, Luke. 2009. “Social News, Citizen Journalism and Democracy.” New Media & Society 11 (8): 1287–1305.

- Gutsche, Robert E., and Kristy Hess. 2018. Geographies of Journalism: The Imaginative Power of Place in Making Digital News. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hallin, Daniel C. 1986. “Cartography, Community, and the Cold War.” In Reading the News: A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture, edited by Robert Karl Manoff and Michael Schudson, 109–145. New York, NY: Pantheon.

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Hanitzsch, Thomas. 2005. “Journalists in Indonesia: Educated but Timid Watchdogs.” Journalism Studies 6 (4): 493–508.

- Hooker, Claire, Catherine King, and Julie Leask. 2012. “Journalists’ Views about Reporting Avian Influenza and a Potential Pandemic: A Qualitative Study: Journalists’ Views about Reporting Avian Influenza and a Potential Pandemic.” Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 6 (3): 224–229.

- Huxford, John. 2007. “The Proximity Paradox: Live Reporting, Virtual Proximity and the Concept of Place in the News.” Journalism 8 (6): 657–674.

- Ihekweazu, Chioma. 2017. “Ebola in Prime Time: A Content Analysis of Sensationalism and Efficacy Information in U.S. Nightly News Coverage of the Ebola Outbreaks.” Health Communication 32 (6): 741–748.

- Joye, Stijn. 2010. “News Discourses on Distant Suffering: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the 2003 SARS Outbreak.” Discourse & Society 21 (5): 586–601.

- Kim, Youngrim. 2020. “Outbreak News Production as a Site of Tension: Journalists’ News-Making of Global Infectious Disease.” Journalism, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920940148.

- Klemm, Celine, Enny Das, and Tilo Hartmann. 2019. “Changed Priorities Ahead: Journalists’ Shifting Role Perceptions When Covering Public Health Crises.” Journalism 20 (9): 1223–1241.

- Kwanda, Febbie Austina, and Trisha T. C. Lin. 2020. “Fake News Practices in Indonesian Newsrooms During and After the Palu Earthquake: A Hierarchy-of-Influences Approach.” Information, Communication & Society 23 (6): 849–866.

- Larrondo, Ainara, David Domingo, Ivar John Erdal, Pere Masip, and Hilde Van den Bulck. 2016. “Opportunities and Limitations of Newsroom Convergence: A Comparative Study on European Public Service Broadcasting Organisations.” Journalism Studies 17 (3): 277–300.

- Lehmann-Jacobsen, Emilie. 2017. “Challenged by the State and the Internet: Struggles for Professionalism in Southeast Asian Journalism.” MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research 33 (62): 18–34.

- Le Masurier, Megan. 2015. “What Is Slow Journalism?” Journalism Practice 9 (2): 138–152.

- Lewis, Justin, and Stephen Cushion. 2009. “The Thirst to Be First: An Analysis of Breaking News Stories and Their Impact on the Quality of 24-Hour News Coverage in the UK.” Journalism Practice 3 (3): 304–318.

- McChesney, Robert Waterman. 2015. Rich Media, Poor Democracy: Communication Politics in Dubious Times. 3rd ed. New York, NY: New Press.

- Nugroho, Yanuar, Muhammad Fajri Siregar, and Shita Laksmi. 2012. Mapping Media Policy in Indonesia. Engaging Media, Empowering Society. Indonesia: Centre for Innovation Policy and Governance. https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:168567&datastreamId=FULL-TEXT.PDF.

- Olsen, Ragnhild Kristine, Victor Pickard, and Oscar Westlund. 2020. “Communal News Work: COVID-19 Calls for Collective Funding of Journalism.” Digital Journalism 8 (5): 673–680.

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2015. “Toward New Journalism(s): Affective News, Hybridity, and Liminal Spaces.” Journalism Studies 16 (1): 27–40.

- Park, Robert E. 1923. “The Natural History of the Newspaper.” The American Journal of Sociology XXIX (3): 273–289.

- Pintak, Lawrence, and Budi Setiyono. 2011. “The Mission of Indonesian Journalism: Balancing Democracy, Development, and Islamic Values.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 (2): 185–209.

- Rantanen, Terhi. 2009. When News Was New. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Reese, Stephen D. 2016. “The New Geography of Journalism Research: Levels and Spaces.” Digital Journalism 4 (7): 816–826.

- Robinson, Sue. 2011. “Convergence Crises: News Work and News Space in the Digitally Transforming Newsroom.” Journal of Communication 61 (6): 1122–1141.

- Rosenberg, Howard, and Charles S. Feldman. 2008. No Time to Think. The Menace of Media Speed and the 24-Hour News Cycle. New York: Continuum.

- Scannell, Paddy. 2014. Television and the Meaning of “Live”: An Enquiry Into the Human Situation. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Schmitz Weiss, Amy. 2020. “Journalists and Their Perceptions of Location: Making Meaning in the Community.” Journalism Studies 21 (3): 352–369.

- Singer, Jane B. 2004. “Strange Bedfellows? The Diffusion of Convergence in Four News Organizations.” Journalism Studies 5 (1): 3–18.

- Tapsell, Ross. 2015. “Platform Convergence in Indonesia: Challenges and Opportunities for Media Freedom.” Convergence 21 (2): 182–197.

- Tejedor, Santiago, Laura Cervi, Fernanda Tusa, Marta Portales, and Margarita Zabotina. 2020. “Information on the COVID-19 Pandemic in Daily Newspapers’ Front Pages: Case Study of Spain and Italy.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (17): 6330.

- Thompson, Esi E. 2019. “Communicating a Health Risk/Crisis: Exploring the Experiences of Journalists Covering a Proximate Epidemic.” Science Communication 41 (6): 707–731.

- Thorsen, Einar, and Daniel Jackson. 2018. “Seven Characteristics Defining Online News Formats: Towards a Typology of Online News and Live Blogs.” Digital Journalism 6 (7): 847–868.

- Tong, Jingrong. 2018. “Journalistic Legitimacy Revisited: Collapse or Revival in the Digital Age?” Digital Journalism 6 (2): 256–273.

- Usher, Nikki. 2014. Moving the Newsroom: Post-Industrial News Spaces and Places. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/https://doi.org/10.7916/D8CJ8RRZ.

- Usher, Nikki. 2015. “Newsroom Moves and the Newspaper Crisis Evaluated: Space, Place, and Cultural Meaning.” Media, Culture & Society 37 (7): 1005–1021.

- Usher, Nikki. 2019. “Putting ‘Place’ in the Center of Journalism Research: A Way Forward to Understand Challenges to Trust and Knowledge in News.” Journalism & Communication Monographs 21 (2): 84–146.

- Usher, Nikki. 2020. “News Cartography and Epistemic Authority in the Era of Big Data: Journalists as Map-Makers, Map-Users, and Map-Subjects.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 247–263.

- Verweij, Peter. 2009. “Making Convergence Work in the Newsroom: A Case Study of Convergence of Print, Radio, Television and Online Newsrooms at the African Media Matrix in South Africa During the National Arts Festival.” Convergence 15 (1): 75–87.

- Wasserman, Herman, and Arnold S. de Beer. 2009. “Towards De-Westernizing Journalism Studies.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 448–458. London, UK: Routledge.

- Wemple, Erik. 2014. “Jon Stewart of ‘The Daily Show’ Rips CNN, Other Cable Networks over MH370 Coverage.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/erik-wemple/wp/2014/03/25/jon-stewart-of-the-daily-show-rips-cnn-other-cable-networks-over-mh370-coverage/?utm_term=.0dfdf9c5a3e2.

- White, Mimi. 2004. “The Attractions of Television: Reconsidering Liveness.” In MediaSpace: Place, Scale and Culture in a Media Age, edited by Nick Couldry and Anna McCarthy, 75–91. London and New York: Routledge.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 1990. “Where is the Author in American TV News? On the Construction and Presentation of Proximity, Authorship, and Journalistic Authority.” Semiotica 80 (1–2): 37–48.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 1992. Covering the Body: The Kennedy Assassination, the Media, and the Shaping of Collective Memory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2017. What Journalism Could Be. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.