ABSTRACT

During times of crisis or instability, citizens are more reliant on news media as a source of information. We need to better understand which news media people consume, how it changes over time, and whether two important predictors of news use – political interest and news media trust – affect news use during times of crisis. Specifically, we investigate the reciprocal dynamics between news media use, political interest, and news media trust in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Analyzing survey data from two waves from the Netherlands (N = 907, with a baseline just before the outbreak of the pandemic), we find that both traditional and online news use, based on self-report measures, increased in the first phase of the public health crisis. Our findings lend general but mixed support for the reciprocal dynamics between news media use and political interest. Interestingly, the results indicate a reciprocal relationship both for use of and trust in non-mainstream news websites and use of and trust in social media.

Changes in News Consumption during Times of Crisis: The Role of Political Interest and News Media Trust during the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, news media are of crucial importance to inform the public (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). Both traditional and online media play a central role in providing citizens with critical information from the government, health authorities, and expert sources. The media do not only help citizens to understand the COVID-19 crisis, but also motivate them to comply with severe measures (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). Hence, the information people consume shapes how citizens understand and respond to the COVID-19 crisis, and how they evaluate which institutions are helping address it (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). Yet, in our current high-choice media environment, increased news consumption may also have negative implications (see also González-Bailón Citation2017). For instance, news consumption via social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) and instant messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp) could facilitate the spread of mis- and disinformation (Brennen et al. Citation2020), which have been regarded as key threats to democracy (van Aelst et al. Citation2017).

Within the framework of media dependency theory, which states that citizens are more reliant on the media during times of crisis (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976; Lowrey Citation2004; Tai and Sun Citation2007), it has been shown that people’s perceived dependency is related to both their trust in media and to the sources they consume (Jackob Citation2010). It therefore seems safe to assume that understanding the interplay between news media use, political interest and news media trust (after all, two important predictors of news consumption), becomes especially important in times of crisis, in which the stakes are simply higher.

But, while the theory of media dependency highlights the relevance of changes in both traditional and online news consumption during times of a major public health crisis, there are only a few studies that indeed empirically examine such processes during times of crisis or instability, such as the September 11 terrorist attacks (Lowrey Citation2004) and the 2003 SARS epidemic in China (Tai and Sun Citation2007). However, since the publication of these studies, the news media landscape has evolved dramatically. With increased online and social media use for news (Newman et al. Citation2020), new evidence is needed that could contribute to this theoretical approach. We need to emphasize that we do not aim to offer a test of media dependency theory here. Instead, we use it as a starting point to substantiate our assumption that it is worth studying dynamic relationships in particular in times of crisis, and that this can offer additional insights beyond such studies in routine periods.

In particular, we explore the role of news media trust and political interest. We aim to understand what sources and platforms people trust during a crisis and, more importantly, how this affects their news consumption. It is expected that people who do not trust news media are less likely to consume news media during a crisis. This might have negative consequences, as people need to be informed during the crisis (e.g., to comply with measurements taken). Conversely, news consumption might also increase trust in the media, as it shows that it can provide valuable information. However, this effect might be stronger for traditional media compared to social media. We also need a better understanding in the role of political interest. Political interest can play a dual role; as citizens who are more interested in politics are more likely to consume news about public issues, whereas increased news exposure to public issues also advances interest (Lecheler and de Vreese Citation2017). It is expected that during a major crisis, political interest might be increased due to more exposure to and experienced importance of politics during the crisis.

However, a major issue in empirical studies exploring how the relationships between media use, trust, and interest differ during a crisis, concerns the timing. After all, to obtain a full picture of how people’s news consumption changed, an additional baseline measure just before a crisis is needed. In this study, we are, from a design perspective, in the fortunate position to have such data at our disposal. First, in this study, we investigate whether, and if so, how, self-reports of news consumption changed in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use two-wave panel survey data, including a baseline just before the outbreak of COVID-19, which allows us to explore changes over time. To contextualize our findings, we additionally compare this data with similar measures investigating media use using longitudinal survey data from earlier periods (2015–2017). Second, as several studies suggest that political interest (Kruikemeier and Shehata Citation2017; Strömbäck, Falasca, and Kruikemeier Citation2018; Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2019) and news media trust (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020) are crucial predictors of news media use, and we believe also during the COVID-19 crisis, as we mentioned above, we examine the causal impact of these predictors on news media use by estimating cross-lagged panel models. To account for the fact that online media becomes more important in informing people (Newman, Levy, and Nielsen Citation2019), we particularly focus on news consumption via non-mainstream news outlets and social media. Hence, the key research question of this study is: “To what extent do political interest and news media trust affect news consumption in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic?” Our research design provides opportunities to analyze the dynamic relationship between content preferences and consumer preferences (i.e., political interest and news media trust)—based on the idea of reinforcing spirals (Slater Citation2007)—during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We argue that these three main categories of features: content features, consumer features, and context features should be explored to understand patterns of news consumption (see Vermeer et al. Citation2020). Those groups of features cannot be studied in isolation, as it is the combination and interaction of all three groups of features to study news consumption in the digital society.

Media use during Times of Crisis

In the current study, we focus on the COVID-19 pandemic. In December 2019, a new coronavirus causing COVID-19 first broke out in China’s Hubei province and then spread to other regions in Asia before it quickly grew into a global pandemic crisis. It resulted in travel restrictions and lockdowns in many countries. In the middle of such a health and economic crisis, media are of crucial importance to inform the public. Traditional and online media take a central role in providing citizens with reliable and trustworthy information and motivating them to comply with severe regulations. Besides news media organizations, online news outlets aim to support citizens in understanding the COVID-19 crisis. Recently, Nielsen et al. (Citation2020) collected survey data in six countries (i.e., Argentina, the US, the UK, Germany, Spain, and South Korea) in March and early April 2020 to examine citizens’ news media use about COVID-19. The findings indicate that news consumption increased in all six countries. Most citizens are using either social media, search engines, video websites (e.g., YouTube), and instant messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp) (or combinations of these) to get news and information about COVID-19. Citizens may use different types of news media for different reasons; traditional mass media outlets (e.g., television, radio) are better at providing information to help citizens understand the world around them, whereas interpersonal communication (e.g., social media, instant messaging) allows citizens to share and discuss the latest developments.

In our current high-choice media environment, with increased media choice (van Aelst et al. Citation2017), people’s preferences have become more important predictors of news outlets and content they expose themselves to (Prior Citation2007): “The greater media choice there is, the more selective people have to be; and the more selective people have to be, the more important their preferences become” (Strömbäck, Falasca, and Kruikemeier Citation2018, 2). Citizens can much more easily opt out of news and only consume the non-political content they prefer. To understand news consumption in a high-choice media environment, we argue that it is important to combine content features (i.e., what?, e.g., news topics), consumer features (i.e., who?, including sociodemographics, political interest, news media trust), and context features (i.e., how?, date, time, platform). Those groups of features cannot be studied in isolation to study news consumption in today’s digital society (see Vermeer et al. Citation2020).

Several studies suggest that political interest (Kruikemeier and Shehata Citation2017; Prior Citation2007; Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2019) and news media trust (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020) have become more important predictors of news media use than they used to be. Even a completely informative news media environment is barely useful for democracy if citizens are not interested in the news or if they do not trust the news (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). Particularly in the early stages of a crisis, it is of crucial importance that citizens have access to reliable and trustworthy information and are interested in understanding the world around them. Nonetheless, there are not many studies focusing on the causal and/or reciprocal effects between news media use and such predictors. By building on the theory of media dependency, we aim to better understand these dynamics during times of crisis. While we do not offer a test of media dependency theory, we take the findings of media dependency theory as a starting point for our expectations and reasoning about the role of the media in times of this pandemic.

The theory of media system dependency states that particularly for societies in states of crisis or instability (e.g., public crisis, social change, or conflict), citizens are more reliant on the mass media as a source of reassurance and information (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976). Ball-Rokeach and Defleur (Citation1976) define dependency as “a relationship in which the satisfaction of needs or the attainment of goals by one party is contingent upon the resources of another party” (7), which intensifies when individuals perceive their social environment to be threatening. For example, during a public health crisis–bringing instability and potentially negative changes to society–citizens are in need of trustworthy information to better understand their social environment (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976; Hu and Zhang Citation2014; Lowrey Citation2004). In this way, a crisis leads to heightened media use. In turn, the greater this media dependency becomes, the greater the likelihood a message will exert affective, behavioral, and/or cognition effects (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976).

Few studies have examined media dependency in times of crisis or instability. A number of scholars have indicated that mainstream mass media, such as television and/or radio, became more important during a crisis (Ball-Rokeach Citation1998). Kim et al. (Citation2004) show that–after the September 11 terrorist attacks–even despite the growing importance of online news as an information resource, people’s reliance on traditional mass media increases in crisis situations. In a different context, Tai and Sun (Citation2007) examined media dependency among Chinese individuals during the SARS epidemic of 2003–when crucial information was not readily available from the mainstream mass media. They indicate that online news and short message service (SMS) text messages played an important role in making citizens aware of the disease. In our current digital society, with more news media choices availaible (e.g., non-mainstream news, instant messaging, social media), it is increasingly important to obtain a better understanding of how news media choices vary during times of crisis.

News Media use and Political Interest

First, we turn our attention to political interest, which is crucial in shaping perceptions and ideas about the (political) world (Moeller and de Vreese Citation2013). During a major crisis, political interest might be increased due to more exposure to and experienced importance of politics during the crisis. Many decisions that are made during the COVID-19 crisis, such as measures to work from home or closure of businesses, are political in nature and are discussed and explained in the media. As a consequence, increased media consumption, where its content is mainly focused on the pandemic and how politicians deal with it by implementing measures, is expected to instigate political interest. For instance, press conferences or talk shows interviewing politicians about measures that have been taken. Moreover, political interested citizens are expected to consume more news media. They might be more curious to know how politicians are dealing with the crisis and are therefore more likely to be exposed to news (as this is the most important source for information about how politicians deal with the pandemic situation). There is, however, very limited knowledge about the relationship between media consumption and political interest during crises.

Turning to the literature on political interest in general, we find that conceptually, political interest has been defined as “the degree to which politics arouses a citizen’s curiosity” (van Deth Citation2000, 278). According to Prior (Citation2010) “political interest is typically the most powerful predictor of political behaviors that make democracy work. Politically interested people are more knowledgeable about politics, more likely to vote, and more likely to participate in politics in other ways” (747). In our current high-choice media environment, political interest has become increasingly important as an individual-level factor behind news media use (Prior Citation2007).

Theoretically, according to Strömbäck and Shehata (Citation2019), there are three possible routes of influence between news media use and political interest: (1) Political interest influences the extent to which people follow the news–indicating selection effects (i.e., already politically interested seek out the news), (2) following the news media might influence political interest–indicating media effects (i.e., citizens who follow the news get more interested in politics), and (3) the effects run in both directions, with political interest influencing news media use which, in turn, influences political interest. Understanding whether correlations between political interest and news media use mirror selection effects, media effects, or reciprocal effects, demands access to panel data. To date, there is rather limited research using longitudinal data to investigate the reciprocal relationship between political interest and a wide variety of news outlets. Earlier work generally focused on comparing traditional and online news media. All these find some reciprocal relationships between political interest and news media use, but also differences across media types. Strömbäck and Shehata (Citation2010) used three-wave panel data to investigate the causal relationship between news media use and political interest in Sweden. The results found that there are indeed causal and reciprocal relationships between political interest and attention to political news, and between political interest and exposure to some, but not all, news media. Kruikemeier and Shehata (Citation2017) conducted a three-wave panel study among adolescents in Sweden to explore reinforcing spirals between traditional news media and online news consumption and political engagement, with political interest as one of the indicators. They found the process appears to be driven primarily by selection effects.

Political interest might only be partly influenced by situational factors, such as elections or a crisis, and is considered to be rather stable (Prior Citation2010; Shehata and Amnå Citation2019). News media use, on the other hand, may be more variable and subject to situational determinants. Hence, especially during a crisis, wherein people depend highly on the media to be informed about the crisis, news consumption might increase. While we already argued that news media use increases during times of crisis, we do not have any specific knowledge about exactly what news content citizens are interested in. As the COVID-19 pandemic has had consequences beyond the spread of the disease itself, the crisis might have affected interest in national news, as well as political news and economic news. Political interest could also trigger citizens to become more engaged and seek out additional information. To examine the reciprocal relationship between interest in news content and political interest in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we pose the following research question:

RQ1: To what extent do reciprocal influences exist between interest in news content and political interest during times of crisis?

Besides, citizens combine different news outlets, such as social media, search engines, video websites, and instant messaging apps, to get news and information about COVID-19 in the early stages of the pandemic (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). According to Boulianne (Citation2011) the characteristics of these news outlets, such as the effort and attention required to use these news outlets and the possibility to share information, determine the causal effects between political interest and news media use (see also Moeller, Shehata, and Kruikemeier Citation2018). In the current study, we extend previous work focusing on traditional news media only (e.g., Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2019), by examining the reciprocal influences between political interest and news use across a wide variety of platforms, including social media, instant messaging apps, and non-mainstream news websites. We explore the relationship between political interest and various news media outlets to understand whether news media use could affect political interest due to more exposure to and experienced importance of politics during the crisis. It could, for example, be argued that during times of crisis, highly politically interested citizens might be more informed about the crisis compared to citizens that are less interested in politics. In turn, this could lead to information inequalities between citizens. We pose the following research question:

RQ2: To what extent do reciprocal influences exist between news media use and political interest during times of crisis?

News Media use and News Media Trust

In times of a major public health crisis, it becomes particularly important that citizens use, and that they trust, the news media (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). Accurate, reliable, and trustworthy information will shape how people understand and respond to a public health crisis. In case of COVID-19, reliable and trustworthy information may prevent citizens to turn to inadequate (and potentially harmful) measures, as well as to either overreact (e.g., by hoarding groceries) or, more alarmingly, underreact (e.g., by engaging in unsafe behavior and unintentionally spreading the virus). Citizens feeling dependent on the media, for example in times of crisis, social change, or conflict, express significantly higher levels of trust in them, whereas citizens using more alternative information sources are–one may argue–probably feeling less dependent. In turn, it can be argued that trust in the news media is the reason for a feeling of media dependency and not the other way around. In a recent study, Nielsen et al. (Citation2020) collected survey data in six countries to understand how citizens access news and information about COVID-19. They also explore the trustworthiness of different news sources and platforms. The results indicate that news media organizations play a crucial role in offering news and information about COVID-19; news media are trusted by a majority in all six countries. However, citizens with lower levels of formal education rate news organizations less trustworthy. Although citizens rely on various platforms, they regard the news and information from social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), video sites (e.g., YouTube), and instant messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp) as much less trustworthy compared to news and information from news organizations.

Turning to the literature on general news trust, it can be found that news media trust is an important predictor of news media use (Kalogeropoulos et al. Citation2019). Recently, Strömbäck et al. (Citation2020) proposed a framework for future research on news media trust and its impact on media use. Besides understanding news media trust at different levels of analysis (e.g., news media in general, media type, individual media brands), the framework allows researchers to explore to what extent news media trust–at varying levels of analysis–is linked to news media use. Surprisingly, there is only a limited number of studies that explore the relationship between news media trust and news media use. Tsfati and Cappella (Citation2003) found that media skepticism is negatively related to mainstream news media use, but positively related to non-mainstream news media use. In a follow-up study, Tsfati (Citation2010) again found that exposure to mainstream media sources is related to trust in media, whereas exposure to non-mainstream sources is related to media skepticism. The same pattern was found by Fletcher and Park (Citation2017), using survey data from eleven countries: They found that citizens with low levels of media trust tend to prefer non-mainstream news sources, such as social media and blogs. Overall, previous work indicates that news media trust is related to increased news media use, whereas media distrust is related to increased use of non-mainstream news outlets. Additionally, previous research suggests that there is an effect where use of different news media types results in increasing trust in these particular news media (Hopmann, Shehata, and Strömbäck Citation2015). This suggests that the correlation between media use and media trust is not only a selection effect but also a media effect. During the COVID-19 crisis, news consumption that is perceived to be informative by its users –because it gives information about the pandemic situation– could positively affect users’ trust in the news media. It might give them information about how to navigate themselves in a difficult situation, for example how to protect themselves from the virus. Conversely, trust in the news media can be a positive predictor of news media consumption as people who trust the media might consume more media to get trustworthy information about how to deal with the pandemic situation or measures that are taken. Contrarily, people who trust the news less, might be less likely to turn to the media for news updates. All in all, news media trust, may serve as a possible link between media dependency and news media use during times of crisis (Jackob Citation2010). Hence, we pose the following research question:

RQ3: To what extent do reciprocal influences exist between news media use and news media trust during times of crisis?

Method

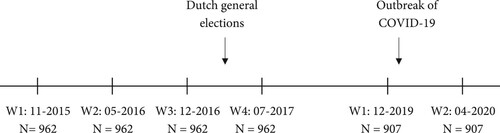

Empirically, this study utilizes longitudinal survey data from the Netherlands (see ). As part of a larger project (supported by the Research Priority Area ‘Information, Communication, and the Data Society’ (ICDS) of the University of Amsterdam), we conducted a two-wave panel study (N = 907): A first wave in early December 2019, just before the outbreak of COVID-19 was identified in Wuhan, China (World Health Organization Citation2020), and a second wave in April 2020, when COVID-19 has spread to the Netherlands where various measures were taken to prevent the spread of the virus. The data were representative of the Dutch population aged 18 years or older. Respondents were recruited by a panel company (Ipsos Netherlands). Among the respondents, 46.1 percent were female, mean age was 50.9 (SD = 15.9), and 25.7 percent had a low level of education, 50.4 percent had a medium level of education, and 23.9 percent had a high level of education.

In addition, to put our findings in perspective and contrast our data, we use longitudinal survey data from previous work, namely a four-wave panel study conducted between 2015 and 2017 (N = 962; Mage = 56.6, SDage = 16.3, 49 percent were female, percent had a high level of education). Respondents were recruited through CentERdata’s LISS panel, which comprised of a representative sample of the Dutch population aged 18 years or older.

Measures

We use the following set of variables (descriptive statistics are presented in )Footnote1:

News use: We categorize thirteen different types of traditional and online news media outlets. Using self-reports, respondents were asked how often they follow the news, (1) by watching television news, (2) by watching current affairs formats, (3) by watching talk shows, (4) by reading printed daily quality newspapers, (5) by reading printed daily tabloid newspapers, (6) by listening to radio news, (7) by visiting online-only news websites, (8) by visiting online news websites, (9) by visiting non-mainstream news websites, (10) by visiting opinion websites, (11) by using social media, (12) by using mobile news apps, and (13) by receiving text messages from friends and family (e.g., WhatsApp)–with response categories ranging from 0 to 7 days per week.

News interest: We asked respondents to rate their interest in nine news topics by asking: “How interested are you reading about the following types of news?”, namely (1) national news, (2) international news, (3) political news, (4) business and economic news, (5) opinion, (6) sports news, (7) news about science, technology, and innovation, (8) news about art and culture, and (9) entertainment and lifestyle news–with response categories ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 7 (very interested).

Political interest: We measured political interest by asking: “How interested are you in politics?”, ranging from 1 (not at all interested) to 7 (very interested).

Trust in media: We measured news media trust on the media type level (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020) by asking: “To what extent do you trust the following outlets?”, including newspapers, public broadcasting, commercial broadcasting, radio, online news websites, and social media–with response categories ranging from 1 (not at all trustworthy) to 7 (very trustworthy).

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for key variables.

Analytical Strategy

The main goal of this study is understanding to what extent political interest and news media trust affect news consumption in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. One major strength of our research design is that the key variables–political interest and news media trust–are measured identically across the two panel studies. Additionally, we have a baseline just before the outbreak of COVID-19, which allows us to explore changes over time. Given the nature of our data, two-wave panel data, and our interest in the reciprocal effects between news use, political interest and news media trust, we estimate cross-lagged panel models using structural equation modeling (see e.g., Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2019). This has several advantages. First, the cross-lagged effects indicate the presence of mutual influence between variables over time, such as media use and political interest or media use and news media trust. It helps us to assess whether the effects run from media use to, for example, political interest (media effects), from political interest to media use (selection effects), or whether there are reciprocal effects between media use and political interest (reciprocal effects). It also provides estimates of the stability of political interest, news media trust, and news media use between waves (Finkel Citation2008). Including past levels of news use, political interest, and news media trust as predictor variables is one of the great benefits of panel data, and strongly advances our ability to make causal inferences.

Results

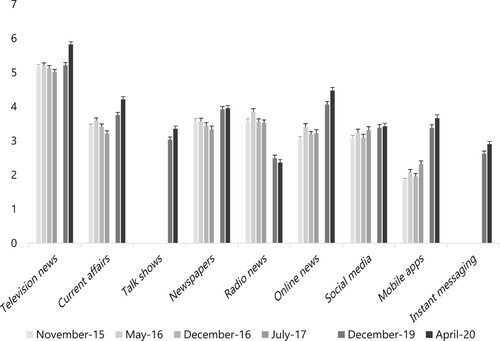

In the current study, we aim to understand to what extent news consumption has changed in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly whether political interest and news media trust affect such changes. Before we turn our attention to the causal and reciprocal effects of our variables, we aim to contextualize our findings by using data from earlier periods. and indicate that news consumption overall increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (in comparison to routine periods a few years ago). For example, watching television news decreased on average from 5.15 (November 2015) to 5.01 days per week (July 2017) (-.14). In April 2020, respondents watched television news, on average, 5.82 days per week (+.61). Visiting online news websites increased from 3.03 (November 2015) to 4.06 (December 2019) to 4.47 days per week (April 2020) (+1.04), and using mobile news apps from 1.81 (November 2015) to 3.37 (December 2019) to 3.66 days per week (April 2020) (+1.85)Footnote2.

The Role of Political Interest

We now turn our attention to the role of political interest. We aim to examine whether reciprocal effects exist between interest in news content, news media use, and political interest. Cross-lagged panel models indicate that political interest is indeed an important predictor of changes in news consumption (see also Figure A2, A3). First, shows the results from six cross-lagged models estimating the reciprocal effects of interest in various forms of news content on the one hand, and political interest on the other hand. We particularly focus on news content related to the COVID-19 pandemic, namely (inter)national news, political news, business and economic news, opinion, and news about science, innovation and technologyFootnote3. Reciprocal dynamics are evident for all six types of news content. Interest in political news has the strongest positive effect on subsequent levels of political interest (b = .34, p < .001), and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction (b = .30, p < .001), suggesting the presence of a reciprocal relationship between interest in various news topics and political interest.

Table 2. Cross-lagged effects between news interest and political interest (unstandardized coefficients).

Second, shows the results from thirteen cross-lagged models estimating the reciprocal effects of traditional as well as online news outlets on the one hand, and political interest on the other hand. Here the evidence for reciprocal effects is less striking. Reciprocal effects are evident predominantly with traditional news outlets. Watching current affairs shows as well as watching talk shows, and reading quality newspapers have positive effects on subsequent levels of political interest, and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction, suggesting the presence of a reciprocal relationship for each of these forms of news media use. Watching television news has a positive effect on political interest (b = .03, p = .006)–but there is no significant effect the other way around, indicating media effects rather than selection effects. We did not find any effects for reading tabloid news and listening to radio news. A second important finding from relates to mixed results for online news use. We only found a reciprocal relationship for visiting non-mainstream news websites and using mobile news apps, indicating positive effects on subsequent levels of political interest as well as the other way around. We found media effects–from news media use to political interest–for visiting online-only news websites (b = .04, p = .01)–but no evidence of selection effects. A selection effect–from political interest to news media use–is found for visiting online news websites (b = .09, p = .05). We did not find any effects for visiting opinion news websites, using social media or instant messaging for news.

Table 3. Cross-lagged effects between news use and political interest (unstandardized coefficients).

Taken together, the results suggest that there are some differences between traditional news use on the one hand, and online news use on the other hand, in terms of reciprocal relationships. It is worth noting that there is a certain degree of overlap in news use (e.g., in April 2020; Table A2). Citizens frequently combine traditional news outlets–those who frequently listen to the radio are also watching television news (Pearson’s r = .21), watching current affairs shows (r = .23), and watching talk shows (r = .23). A comparable pattern can be found for online news outlets–citizens who frequently use instant messaging apps for news are also more likely to visit non-mainstream news websites (r = .24), visit opinion news websites (r = .22), use social media (r = .41), and use mobile news apps (r = .26).

Finally, the results in and indicate that political interest remains rather robust over time, and is consistently higher than all forms of news media content and news media use (as reflected by the stability coefficients).

The Role of News Media Trust

Next, we turn our attention to news media trust. As shown in , citizens rate news organizations (e.g., broadcasters, newspapers) as rather trustworthy sources of information, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trust in news received from others, however, decreased on average from 4.20 (December 2019) to 4.06 (April 2020). We estimate cross-lagged panel models using structural equation modeling to analyze the causal and reciprocal effects between news media use and news media trust. The results are presented in (see also Figure A4). Interestingly, reciprocal effects are evident only with respect to social media and non-mainstream news websites. Each of these forms of news media use has a positive effect on subsequent levels of news media trust, and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction, suggesting the presence of a reciprocal relationship. Effects from news media use to news media trust are found for quality newspapers (b = .04, p = .010), tabloid newspapers (b = .02, p = .050), radio news (b = .03, p = .010), and online news (b = .03, p = .003). Not surprisingly, the results indicate significant differences between public and commercial broadcasting. Though we did not find any significant effects between television news, current affairs shows, or talk shows, and trust in commercial broadcasting, we found some effects for trust in public broadcasting. First, watching talk shows has a positive effect on subsequent levels of trust in public broadcasting (b = .04, p = .008), and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction (b = .11, p = .013), suggesting the presence of a reciprocal relationship between watching talk shows and trust in public broadcasting. We also found an effect of television news on trust in public broadcasting (b = .03, p = .014).

Table 4. Cross-lagged effects between news use and political interest (unstandardized coefficients).

Interestingly, as shown in there appears to be a significant degree of overlap in news media trust. Citizens who trust radio news are also more likely to trust public broadcasting (Pearson’s r = .74), commercial broadcasting (r = .59), and newspapers (r = .70). We also found that citizens who trust social media, are also more likely to trust non-mainstream websites (r = .49), and news received from friends and/or family (r = .37). It is also worth noting that the stability coefficients of trust in traditional news outlets, such as television news, newspapers, and radio news, are higher compared to online news outlets (e.g., online news, social media, instant messaging).

Next, we aim to further examine using social media and visiting non-mainstream news websites. Not only because they indicate reciprocal effects with news media trust, but also because such platforms could play an important role in facilitating the spread of mis- and disinformation. We estimated a series of cross-lagged panel models to understand the reciprocal effects between news media trust and news use. Trust in non-mainstream news websites has a positive effect on subsequent levels of social media use for news (b = .11, p < .01), and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction (b = .06, p < .01). We also found that trust in social media has a positive effect on subsequent levels of visiting non-mainstream news websites (b = .18, p < .01), and there are also significant positive effects in the other direction (b = .05, p < .01).

Discussion

The present study has aimed at making a distinct contribution to the literature by exploring changes in news consumption during a major public health crisis. In particular, we examined which news media citizens consume, how this changes over time, and whether two important predictors of news use–political interest and news media trust–affect changes in news consumption in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted a two-wave panel study in the Netherlands: A first wave in early December 2019, just before the outbreak of COVID-19 in China’s Hubei province, and a second wave in April 2020, when COVID-19 had spread to the Netherlands where various measures were taken to prevent the spread of the virus. The results indicate that both traditional as well as online news consumption increased in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (in comparison to routine periods a few years ago). Our findings also lend general but mixed support for the reciprocal dynamics between news media use, political interest, and news media trust. We will discuss our results and their implications for communication research in more detail in the next paragraphs.

While we did not explicitly test media dependency theory, our findings are in line with it (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976). During a crisis that brings instability and potentially negative changes to a society, citizens are in need of information to better understand the world around them. The higher the threat level, the more dependent people become on media, particularly mass media outlets. Our results indicate that news consumption increased in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is in line with what media dependency theory would suggest for times of crisis. Usage of television news surpasses that of all other media forms. We used panel data collected between 2015 and 2017 to put our findings in perspective. We indeed find more changes in news use in the period between 2019 and 2020 in comparison to panel waves in 2015, 2016, and 2017. This is in line with prior research on public crisis situations, such as the September 11 terrorist attacks (Lowrey Citation2004), the 2003 SARS epidemic in China (Tai and Sun Citation2007), as well as the COVID-19 pandemic in particular (Nielsen et al. Citation2020). Citizens may use different types of news media for different reasons; traditional mass media outlets are better at providing information to help citizens understand the world around them, whereas social media and instant messaging apps offer the opportunity to share and discuss the latest developments. Yet, one can argue that news use increased in the early stages of the pandemic, not only because of a higher threat level (Ball-Rokeach and Defleur Citation1976), but also because being forced to stay at home as well as feelings of boredom and loneliness may have led to increased news use (Léger et al. Citation2020).

We also aim to understand whether political interest and news media trust serve as a possible link between media dependency and news media use during times of crisis by examining their reciprocal dynamics. First, we extend previous knowledge by examining the relationship between political interest and interest in news content. The findings also clearly suggest a reciprocal effect for various news topics. The effects are particularly strong with respect to interest in political news. Political interest has a positive causal impact on interest in political news, and interest in political news has a positive causal impact on political interest. One reason for this result could be that, during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens were more interested in reading the latest news as a way to understand the highly changeable policies to control the outbreak of the COVID-19 and grasp the uncertainty and insecurity on how the virus will develop (both nationally and internationally). Besides, for many years, scholars have raised their concerns as consuming entertainment news might lead to opposite effects by negatively influencing political interest (Prior Citation2007). Although our regression analyses indicate that interest in entertainment and lifestyle news decreases political interest, we did not find any evidence for changes over time. The effects were generally positive. In other words, we did not find any support for ‘media malaise’–suggesting media have negative democratic influences (Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2010).

We also examined the relationship between political interest and news use across a wide variety of traditional as well as online news outlets–as called for by Kruikemeier and Shehata (Citation2017). By distinguishing between media effects and selection effects we aim to understand whether there are reciprocal influences between political interest and news media use (Slater Citation2007). We find some reciprocal relationships between political interest and news media use, but also differences across media types. The findings reveal several instances of reciprocal effects, particularly for traditional news media outlets (e.g., watching current affairs shows, reading quality newspapers). According to Strömbäck and Shehata (Citation2010) the relationship between news media exposure and political interest depends on political content. Exposure to news media that report extensively on politics primes citizens’ political interest. Contrarily, Kruikemeier and Shehata (Citation2017), found that political interest is primarily related to television and online news media use. Compared to research by Kruikemeier and Shehata (Citation2017), this study was conducted in Netherlands, with different time lags between panel waves, and based on a sample of the general population. More importantly, we conducted our study in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The exceptional conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic might help us to understand the reciprocal dynamics outside routine periods. It could for instance be argued that many decisions during the COVID-19 crisis are political in nature and are discussed and explained in the media. As a consequence, increased media consumption, where its content is mainly focused on the pandemic and how politicians deal with it by implementing measures, is expected to instigate political interest. For instance, press conferences or talk shows interviewing politicians about measures that have been taken. Moreover, our results indeed indicate that political interested citizens are consuming more news media. They might be more curious to know how politicians are dealing with the crisis and are therefore more likely to be exposed to news. In addition, different types of news media can be used for different reasons. For instance, traditional mass media outlets are better at providing information to help citizens to understand the crisis, whereas social media and instant messaging apps allow citizens to share and discuss the latest developments. More research is certainly needed to explore these relationships further. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that, in line with earlier work (Kruikemeier and Shehata Citation2017), we found stronger selection effects than media effects when examining specific forms of news media use. In line with the work of Prior (Citation2007), political interest turned out to be very stable. This indicates that citizens who are interested in politics are more likely to consume news, but this type of media use does little to further promote interest.

The storey is somewhat different for news media trust. In this case, in line with Strömbäck and Shehata (Citation2019), also comparing public service and commercial television, our findings suggest that public broadcasting makes a difference. More specifically, across cross-lagged models, our results reveal that there is a reciprocal relationship between trust in public broadcasting and watching television, but not for trust in commercial broadcasting. Public broadcasting television tend to provide more hard news (Reinemann, Stanyer, and Scherr Citation2016), leading those who are politically interested to watch public service television rather than commercial television (i.e., selection effect). Public service television also has a strong reputation as a reliable source for political and public issues, which, in turn, can have a stronger impact on political interest than watching commercial television (i.e., media effect; Strömbäck and Shehata Citation2019). It is also worth noting that this study was conducted in a country with comparatively strong public service broadcasting institutions.

Our findings reveal instances of reciprocal effects for visiting non-mainstream news websites and using social media. The discussion about mis- and disinformation online is focused around non-mainstream outlets, and particularly social media news use. Since (mis)information about the COVID-19 pandemic can be overwhelming, it is important to elaborate on these findings. It has been argued before that during a major public health crisis, citizens may increasingly rely on online and social media to share and discuss news. We found a reciprocal effect between trust in non-mainstream news and visiting non-mainstream news websites. We also found a reciprocal effect between trust in social media and visiting non-mainstream news websites. On the one hand, it can be argued that those who trust such outlets—because they offer an alternative view—prefer to use non-mainstream outlets precisely because they provide quick access to a range of views and perspectives. On the other hand, their audiences might learn that the same event can be presented in many different ways. As a result, they might become more aware of the manipulative power of news and thus more skeptical toward journalism (Tsfati Citation2010).

Besides, there is a reciprocal relationship between using social media for news and trust in social media. We also found a reciprocal effect between trust in non-mainstream news and using social media for news. According to Chen et al. (Citation2020), social media, due to their openness and participatory nature, offer important advantages in delivering interactive communication between, for example, governments and citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Citizens feel more concerned, valued, and recognized and feel a greater sense of belonging to governments as well as their social networks when public participation is embedded into political activities, such as public policy discussions. Yet, social media allow citizens to by-pass traditional media outlets, provide channels for attacks on the news media, and facilitate the spread of mis- and disinformation (Brennen et al. Citation2020). Although the relationship between use of and trust in these different types of communication channels may be more complicated than a negative (or positive) linear relationship, future research, possibly using mixed methods, needs to disentangle these relationships in greater detail.

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study has provided a set of findings to understand the relationship between political interest, news media trust, and news media use, a few shortcomings should be noted. First, despite being very common, measuring news consumption based on respondents’ self-reported answers is not optimal (see e.g., de Vreese and Neijens Citation2016). Potential problems with self-report measures not only include overreporting news exposure, but measuring a high number of news outlets could also result in motivational problems or difficulties with recalling news exposure. Hence, it can be questioned whether media consumption has changed or whether people’s recall of media use has changed. Various scholars have argued that tracking-based measures differ from survey-based measures (see e.g., Araujo et al. Citation2017; Scharkow Citation2016). A large meta-analysis of the reliability and temporal stability of self-reported media use by Scharkow (Citation2019) indicates moderate reliability (in line with the findings of the previously mentioned studies that compare with tracking data) but high temporal stability.

Furthermore, although panel data with two waves significantly advances our ability to make causal claims by allowing analyses over time, they do not solve the problem of causality. There are reasons for being cautious against too strong conclusions in this regard. Cross-lagged panel models are based on specific assumptions regarding the time lags between cause and effect (Finkel Citation2008). Although panel studies are stronger in terms of external validity than experiments, our panel surveys still have to deal with some biases. For instance, estimating cross-lagged panel models might lead to simultaneity bias. We cannot be fully certain whether the different findings have methodological or theoretical explanations. Although we find differences across media types, and modest correlations, more research is certainly needed to comprehensively understand the reciprocal relationship between political interest and news media use, for example by including attention and exposure measures.

Moreover, we address the key assumptions using two waves of panel data covering a period of five months. Therefore, we can only examine changes in news use in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. A crisis usually consists of four stages, with a particularly high threat level during the outbreak stage (Fink Citation1984). Citizens are likely to have varying levels of information needs in different phases of a crisis; the use of traditional mass media, for example, is likely to decline after the outbreak of a crisis (Hu and Zhang Citation2014). Furthermore, at a certain stage, the news might also simply be “too much” for citizens eventually leading to news avoidance (de Bruin et al. Citation2021). Future research could extend the initial findings by examining the reciprocal relationship between news media use, political interest, and news media trust over an extended period of time, to understand whether these dynamics differ at different stages of a crisis.

Nonetheless, this study has provided a strong set of findings to understand news consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. By focusing on two important predictors of news use, namely political interest and news media use, these findings not only update and advance earlier research about the mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects, but also provide a further understanding of the role of context and content features in news consumption patterns.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

The research was supported by the Research Priority Area ‘Information, Communication, and the Data Society’ (ICDS) of the University of Amsterdam. https://www.uva-icds.net.

Notes

1 To improve the representativeness of the sample, we present our descriptives using a weighting factor— based on a combination of the following variables: gender, age, education, and region.

2 We also examined the correlation between news use measures across panel waves (see Figure A1). We find more changes in news use measures in the period between 2019 and 2020 in comparison to panel waves in 2015, 2016, and 2017. Put differently, the correlation coefficients indicate a strong relationship between news use measures between, for example, 2016 and 2017 (watching television news: r = .81, reading printed daily newspapers: r = .72, listening to radio news: r = .78, visiting online news websites: r = .67, using social media: r = .71, and using mobile news apps r = .68). We found somewhat less strong correlations between news use measures in the period from December 2019 to April 2020. The correlations between prior and latter values of visiting online news websites, using social media, and using instant messaging are .62, .58 and .46, respectively. Correlation coefficients are somewhat stronger for traditional news consumption between December 2019 and April 2020 (watching television news: r = .78, reading printed daily newspapers: r = .72, and listening to radio news: r = .63).

3 In addition, we estimated a series of cross-lagged panel models with interest in sports news, arts and culture news, and entertainment and lifestyle news (Figure A2). Surprisingly, the results indicate that sports news as well as arts and culture news have positive effects on subsequent levels of political interest–but there are no effects the other way around.

References

- Araujo, T., A. Wonneberger, P. Neijens, and C. de Vreese. 2017. “How Much Time do you Spend Online? Understanding and Improving the Accuracy of Self-Reported Measures of Internet use.” Communication Methods and Measures 11 (3): 173–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1317337.

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J. 1998. “A Theory of Media Power and a Theory of Media use: Different Stories, Questions, and Ways of Thinking.” Mass Communication and Society, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.1998.9676398.

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J., and M. L. Defleur. 1976. “A Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects.” Communication Research 3 (1): 3–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/009365027600300101.

- Boulianne, S. 2011. “Stimulating or Reinforcing Political Interest: Using Panel Data to Examine Reciprocal Effects Between News Media and Political Interest.” Political Communication 28 (2): 147–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.540305.

- Brennen, J. S., F. M. Simon, P. N. Howard, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation. Retrieved from http://www.primaonline.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19_reuters.pdf.

- Chen, Q., C. Min, W. Zhang, G. Wang, X. Ma, and R. Evans. 2020. “Unpacking the Black box: How to Promote Citizen Engagement Through Government Social Media During the COVID-19 Crisis.” Computers in Human Behavior 110), doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106380.

- de Bruin, K., Y. de Haan, R. Vliegenthart, S. Kruikemeier, and M. Boukes. 2021. “News Avoidance During the COVID-19 Crisis: Understanding Information Overload.” Digital Journalism, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1957967.

- de Vreese, C. H., and P. Neijens. 2016. “Measuring Media Exposure in a Changing Communications Environment.” Communication Methods and Measures 10 (2-3): 69–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1150441.

- Fink, S. 1984. Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable. New York, NY: AMACOM Books.

- Finkel, S. E. 2008. “Linear Panel Analysis.” In Handbook of Longitudinal Research: Design, Measurement, and Analysis, 475–504. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier.

- Fletcher, R., and S. Park. 2017. “The Impact of Trust in the News Media on Online News Consumption and Participation.” Digital Journalism 5 (10): 1281–1299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1279979.

- González-Bailón, S. 2017. Decoding the Social World: Data Science and the Unintended Consequences of Communication. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Hopmann, D. N., A. Shehata, and J. Strömbäck. 2015. “Contagious Media Effects: How Media use and Exposure to Game-Framed News Influence Media Trust.” Mass Communication and Society 18 (6): 776–798. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2015.1022190.

- Hu, B., and D. Zhang. 2014. “Channel Selection and Knowledge Acquisition During the 2009 Beijing H1N1 flu Crisis: A Media System Dependency Theory Perspective.” Chinese Journal of Communication 7 (3): 299–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2014.926951.

- Jackob, N. 2010. “No Alternatives?” The Relationship Between Perceived Media Dependency, use of Alternative Information Sources, and General Trust in Mass Media. International Journal of Communication 4: 589–606.

- Kalogeropoulos, A., J. Suiter, L. Udris, and M. Eisenegger. 2019. “News Media Trust and News Consumption: Factors Related to Trust in News in 35 Countries.” International Journal of Communication 13: 3672–3693. doi:https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-175863.

- Kim, Y. C., J. Y. Jung, E. L. Cohen, and S. J. Ball-Rokeach. 2004. “Internet Connectedness Before and After September 11 2001.” New Media & Society 6 (5): 611–631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/146144804047083.

- Kruikemeier, S., and A. Shehata. 2017. “News Media use and Political Engagement among Adolescents: An Analysis of Virtuous Circles Using Panel Data.” Political Communication 34 (2): 221–242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1174760.

- Lecheler, S., and C. H. de Vreese. 2017. “News Media, Knowledge, and Political Interest: Evidence of a Dual Role from a Field Experiment.” Journal of Communication 67 (4): 545–564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12314.

- Léger, D., F. Beck, L. Fressard, P. Verger, P. Peretti-Watel, P. Peretti-Watel, … J. Ward. 2020. “Poor Sleep Associated with Overuse of Media During the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Sleep, doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaa125.

- Lowrey, W. 2004. “Media Dependency During a Large-Scale Social Disruption: The Case of September 11.” Mass Communication and Society 7 (3): 339–357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327825mcs0703_5.

- Moeller, J., and C. de Vreese. 2013. “The Differential Role of the Media as an Agent of Political Socialization in Europe.” European Journal of Communication 28 (3): 309–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113482447.

- Moeller, J., A. Shehata, and S. Kruikemeier. 2018. “Internet use and Political Interest: Growth Curves, Reinforcing Spirals, and Causal Effects During Adolescence.” Journal of Communication 68 (6): 1052–1078. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy062.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, A. Schulz, S. Andı, and R. K. Nielsen. 2020. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 (Tech. Rep.).

- Newman, N., D. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2019. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019 (Tech. Rep.).

- Nielsen, R. K., R. Fletcher, N. Newman, J. S. Brennen, and P. N. Howard. 2020. Navigating the ‘infodemic’: How people in six countries access and rate news and information about coronavirus (Tech. Rep.).

- Prior, M. 2007. “Post–Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. Cambridge.” England: Cambridge University Press, doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139878425.

- Prior, M. 2010. “You’ve Either got it or you Don’t?” The Stability of Political Interest Over the Life Cycle. Journal of Politics 72 (3): 747–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000149.

- Reinemann, C., J. Stanyer, and S. Scherr. 2016. “Hard and Soft News.” In Comparing Political Journalism, edited by C. D. Vreese, E. Frank, and D. N. Hopmann, 131–149. London: England: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315622286

- Scharkow, M. 2016. “The Accuracy of Self-Reported Internet use: A Validation Study Using Client log Data.” Communication Methods and Measures 10 (1): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2015.1118446.

- Scharkow, M. 2019. “The Reliability and Temporal Stability of Self-Reported Media Exposure: A Meta-Analysis.” Communication Methods and Measures 13 (3): 198–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2019.1594742.

- Shehata, A., and E. Amnå. 2019. “The Development of Political Interest among Adolescents: A Communication Mediation Approach Using Five Waves of Panel Data.” Communication Research 46 (8): 1055–1077. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217714360.

- Slater, M. D. 2007. “Reinforcing Spirals: The Mutual Influence of Media Selectivity and Media Effects and Their Impact on Individual Behavior and Social Identity.” Communication Theory 17 (3): 281–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x.

- Strömbäck, J., K. Falasca, and S. Kruikemeier. 2018. “The mix of Media use Matters: Investigating the Effects of Individual News Repertoires on Offline and Online Political Participation.” Political Communication 35 (3): 413–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1385549.

- Strömbäck, J., and A. Shehata. 2010. “Media Malaise or a Virtuous Circle? Exploring the Causal Relationships Between News Media Exposure, Political News Attention and Political Interest.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (5): 575–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01913.x.

- Strömbäck, J., and A. Shehata. 2019. “The Reciprocal Effects Between Political Interest and TV News Revisited: Evidence from Four Panel Surveys.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (2): 473–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018793998.

- Strömbäck, J., Y. Tsfati, H. Boomgaarden, A. Damstra, E. Lindgren, R. Vliegenthart, and T. Lindholm. 2020. “News Media Trust and its Impact on Media use: Toward a Framework for Future Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 139–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1755338.

- Tai, Z., and T. Sun. 2007. “Media Dependencies in a Changing Media Environment: The Case of the 2003 SARS Epidemic in China.” New Media & Society 9 (6): 987–1009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807082691.

- Tsfati, Y. 2010. “Online News Exposure and Trust in the Mainstream Media: Exploring Possible Associations.” American Behavioral Scientist 54 (1): 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764210376309.

- Tsfati, Y., and J. N. Cappella. 2003. “Do People Watch What They do not Trust? Exploring the Association Between News Media Skepticism and Exposure.” Communication Research 30 (5): 504–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203253371.

- van Aelst, P., J. Strömbäck, T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. de Vreese, J. Matthes, … J. Stanyer. 2017. “Political Communication in a High-Choice Media Environment: A Challenge for Democracy?” Annals of the International Communication Association 41 (1): 3–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551.

- van Deth, J. W. 2000. “Interesting but Irrelevant: Social Capital and the Saliency of Politics in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 37 (2): 115–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007088702196.

- Vermeer, S. A. M., D. Trilling, S. Kruikemeier, and C. de Vreese. 2020. “Online News User Journeys: The Role of Social Media, News Websites, and Topics.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1114–1141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1767509.

- World Health Organization. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019