ABSTRACT

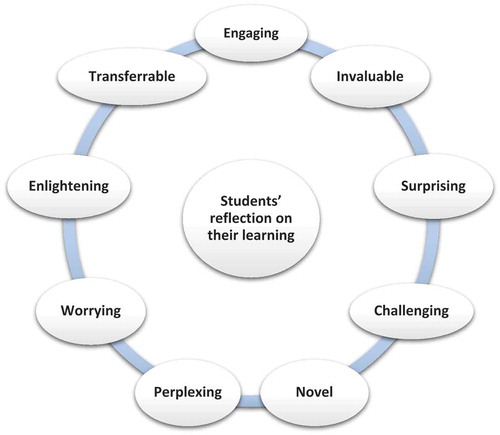

Reflective journals are used to develop students’ writing skills, assess reflection level, gather research data, promote teachers’ professional development, promote instructional practices, and affect students’ learning. However, little research explored the impact of reflective journals on undergraduate students’ learning and its challenges in an English writing course. The current study fills the gap in the literature by exploring Qatari female undergraduate students’ perspectives of reflective journals in an English writing course and identifying their challenges with using reflective journals. Social constructivism and Gibb’s reflective cycle informed the theoretical framework of the study. Using a case study methodology, the researcher designed a reflective journal based on Gibbs’ reflective cycle. Accordingly, reflective journals, written by 55 Qatari female undergraduate students, were collected and qualitatively analysed using thematic content analysis. Findings revealed that students experienced the following learning moments in their English writing course: engaging, invaluable, surprising, challenging, novel, perplexing, worrying, enlightening, and transferrable. Moreover, participants reported a number of benefits and challenges of using reflective journals that are peculiar to the Qatari context. Implications for using reflective journals in higher education are provided.

1. Introduction

Reflection on learning and learning from reflective experience are essential skills for learning and decision-making processes (Bell et al., Citation2011). Due to its significance, reflection is embedded in university graduate attributes, course objectives and assessments, and professional standards (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013).

Developing students’ reflection skills in higher education is important for some reasons. First, it promotes effective and lifelong changes in students’ lives (Rogers, Citation2001). Second, it prepares students effectively for their professional contexts (Phan, Citation2007). Moreover, it helps students engage in reflective dialogue and explicitly connect theory to practice, when supported by teachers’ feedback (Brockbank & McGill, Citation2007). Besides, it makes learning more relevant, contextualised and meaningful to students (Higgins, Citation2011). Also, it effectively informs instructional practices at the university level (Ahmed, Citation2019). Furthermore, it helps teachers think critically about their professional development (Helyer, Citation2015) and helps students think critically about their learning (Bennett et al., Citation2016).

Research showed that keeping a reflective journal has other benefits for students. It helps students keep a progress log on a project (Loo, Citation2002); learn course content and connect it to their lives (Moon, Citation2006); improve observation skills through documentation and analysis of field observation (Craft, Citation2005); clarify students’ thinking and critical reflection on incidents discussed in class and improve their writing (R. Fisher, Citation2005); develop students’ voice and affirm beliefs and insights (Hatcher & Bringle, Citation1997); reflect on deeply-rooted beliefs (Tsang, Citation2003); and identify and solve their problems (Durgahee, Citation1998).

Reflective journal writing is ‘a teaching strategy whereby students write their experiences and feelings “uncensored” in their writing style for further reflection and analysis’ (Heath, Citation1998, p. 593). The current study operationally defines reflective journals as a teaching/learning strategy in which students question and reflect on their own learning to enhance their learning and reflection experiences in a university context. Therefore, the current study attempts to investigate the impact of reflective journals on students’ learning and their challenges of using these journals to yield new understandings and interpretations of using reflective journals in a conservative university context in Qatar.

2. Literature review

This section reviews the literature and previous studies related to the importance and benefits of reflective journals and their associated challenges.

2.1. Importance & benefits of reflective journaling

Previous research highlighted that reflective journaling is essential for developing students’ critical thinking and reflective practices. For example, Simpson and Courtney (Citation2007) explored how 20 Middle Eastern nurses used reflective journaling to guide their critical thinking and clinical experiences. Findings highlighted that reflective journaling helped them reflect, speculate, synthesise experienced events during their clinical practice; enabled them to write down subjective and objective data; created a dialogic relationship between nurses and their educators; and improved their English writing. In another study, Chitpin (Citation2006) investigated the effectiveness of reflective journals to develop pre-service teachers’ reflective practices. The 28 reflective journal entries enabled pre‐service teachers to identify and find applicable solutions to curriculum, classroom management and assessment issues.

Previous research reported that reflective journals are a useful tool for learning. For example, Fullanaa et al. (Citation2016) explored Spanish students’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of reflective learning. Findings indicated that students believed reflective learning helped them better understand their learning and motivation to learn. Students reported understanding the aims of the reflective learning experience, the degree of personal openness and the system of assessment, as some challenges. The current researcher informed course instructors that students need to understand the aims of reflection and the degree of personal openness.

Similarly, Chirema (Citation2007), who used reflective journals to enhance reflection and learning among 42 nursing students, suggest that reflective journaling is a useful tool that enhances learning and reflecting, but not for all students. Correspondingly, Rué et al. (Citation2013) used reflective journals with problem-based learning with law undergraduate students. Findings revealed that reflection fosters students’ quality of learning and improves their own learning.

Additionally, Turhan and Kirkgoz (Citation2018) explored 49 Turkish pre-service teachers’ critical reflections, development of their reflection level over time, and the benefits of observation and critical reflections. Findings showed that the participants did not reach a high level of critical reflections; however, they experienced a real classroom environment, gained new insights into teaching skills, identified good and bad teaching practices, recognised the positive and negative aspects of a teacher, and realised the gap between theory and practice.

Reflective journals helped students develop their reading comprehension, English writing skills and word choice and voice. For example, Chang and Lin (Citation2014) investigated the effect of online reflective journals with 98 undergraduate students. The experimental group which used online reflective journals outperformed the control group in reading comprehension, organisational writing skills and preparation of final exams. Similarly, Alsaleem (Citation2013), who examined the effect of WhatsApp journaling, reported that the experimental group students improved in their word choice and voice.

2.2. Challenges of reflective journaling

Despite its benefits, reflective journaling has some challenges. For example, Abednia et al. (Citation2013) reported that the lack of reading the course materials and taking part in class discussions, and the conflict between the schooling background and the nature of reflective journals, as some challenges. Therefore, the writing teachers in the current study ensured that Qatari female students have access to the reading materials and took part in the classroom discussion. However, the researcher could not control the possible tension between the Qatari schooling background and the nature of reflective journals as some Qatari female students were not used to reflection in their high schools.

In another study, Varner & Peck (Citation2003) found grading reflective journals, the frequency of grading, and grading bias, challenging. Unlike non-native speakers, native-speaker students found writing reflective journals very natural. Similarly, L1 Arabic students have problems with their cohesion and coherence in their L2 English writing (Ahmed, Citation2010). In the current study, students’ reflective journals were graded upon completion.

Writing in the personal voice and facilitating the reflection process are two other reported challenges (Pavlovich, Citation2007). In the current study, Qatari students found having a voice a bit problematic; however, the required training was done to help students reflect elaborately and critically.

In their study, O’Connell and Dyment (Citation2011) referred to the following nine challenges with using reflective journaling: (1) the lack of training or structure on how to use reflective journals; (2) writing to please the teacher to get a good grade; (3) reflective journaling is an annoying busywork for some students; (4) reflective journals will not meet all the students’ needs and learning styles; (5) some ethical issues may arise from the communication between the teacher and students when sensitive and confidential information is revealed in their reflective journals; (6) reflective journals are time-consuming for some students; (7) some legal considerations might arise due to the use of reflective journals as evidence in court; (8) evaluating reflective journals can be challenging, and (9) critical reflection could be a challenge for some students.

Students’ voice in the educational process can add value to improving education (McDermott, Shank, Shervinskie & Gonzalo, Citation2019); and identify factors that help/hinder students’ learning (Seale, Citation2009). However, previous research emphasised that students’ viewpoints are absent from significant discussions that have a direct impact on them (Messiou, Citation2019).

Therefore, the current research fills in the literature gap by attempting to further enhance our understanding of the voices of female Qatari students through their reflective journals in an English writing course in a university context in Qatar. The current study contributes to having students’ voices heard and incorporated into planning, decision making and pedagogy to enhance their learning and reflection and improve the quality of higher education. Besides, reflective journals can help enhance students’ awareness of the value of journaling on one hand and overcome the associated challenges on the other hand. Therefore, the overarching aim of the current study is to explore the impact of reflective journals on Qatari female undergraduate students’ learning and its associated challenges at a university in Qatar. Based on the reviewed literature and the research aims, the current study is guided by the two following questions:

What is the impact of reflective journals on Qatari female undergraduate students’ learning in an English writing course?

What challenges do Qatari female undergraduate students encounter with their use of reflective journals in an English writing course?

3. Methods

Situated within an interpretive qualitative research design, the current case study uses students’ written reflective journals to understand the context where the participants act to justify why things happened the way they did (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2000). In particular, the current study aims to explore the impact of reflective journals on Qatari students’ learning and identify students’ challenges with reflective journals.

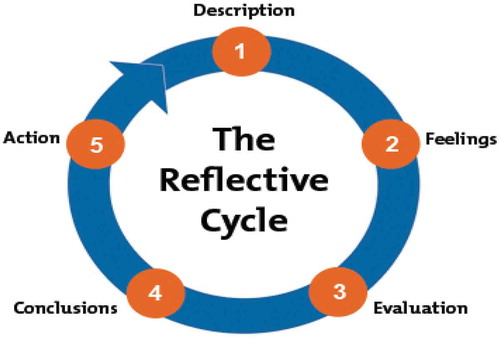

Social constructivism, along with Gibbs’ reflective cycle (Gibbs, Citation1988) informed the theoretical framework of the current study. Knowledge is socially constructed through the viewpoints of the study participants (Andrews, Citation2012) and how culture and context interact to interpret and understand reality (Pritchard & Woollard, Citation2010). Guided by the five phases of description, feelings, evaluation, conclusion and action in Gibb’s reflective cycle (Gibbs, Citation1988) (See ), the researcher designed a reflective journal template with some probing questions to help Qatari female undergraduate students reflect on their learning of English writing and their challenges with using reflective journals (See appendix).

Figure 1. The reflective cycle (Gibbs, Citation1988).

3.1. Participants and instructional context

The current study took place in a university in Qatar, known for its conservative nature where male and female interaction is limited based on the code of modesty (Romanowski & Al-Hassan, Citation2013).

As shown in , 50 undergraduate female Qatari students and 3 male teachers participated voluntarily in the current study. Two reasons lie behind the choice of female participants: education is segregated in the concerned university in Qatar, and the instructors were assigned to teach female participants at the time of the study. Participants were 50 bilingual female students in different years of study whose age ranged from 18 to 22 years old. L1 Arabic was the students’ mother tongue and L2 English was the Medium of Instruction (EMI).

Table 1. Participants’ demographics.

Participants were asked to write a weekly reflective journal using the template in the appendix. Participants were informed that their teachers and the researcher would read their reflective journals. The reflective journal is a formative assignment marked out of 5% upon completion. The issue of teacher-students power relations was not seemingly affecting students as they knew that the full mark is guaranteed upon completion of the reflective journals and their teachers ensured that their viewpoints would neither impact their grades nor their relations with them. Consequently, participants wrote their reflective journals unbiasedly.

Using purposive sampling, along with the accessibility criterion (Silverman, Citation2001), participants voluntarily agreed to take part in the current research and signed an informed consent form.

3.2. Data collection

Despite the plethora of reflection models (Bass et al., Citation2017; Gibbs, Citation1988; Johns, Citation1994), Gibbs (Citation1988) () was used in the current study as it helps students reflect on their learning in a structured way (Ahmed, Citation2019; Helyer, Citation2015). Moreover, Gibbs’ model provided a guiding structure and some questions to ease female students’ reflection on their learning and their challenges with using reflective journals, as this was their first experience with reflective writing. Five specialists in TESOL/Applied Linguistics reviewed the reflective journal template designed by the researcher to check the face validity. Moreover, the reflective journal template was piloted on three students from the same sample to check the clarity of questions and ease of response. Based on the students’ feedback, some adjustments were made, and the final version of the journal was designed.

A reflective journal provided a framework to help students structure their reflection. Based on the students’ superficial and brief responses to the reflective journal dimensions and questions during the first week of the course, the researcher trained the three teachers for an hour on how to help students respond elaborately and critically to the reflective journal questions. Consequently, the teachers trained their female students, through real anonymous examples, on how to reflect critically. Students used to submit their weekly reflective journals electronically via Blackboard. The teachers used to respond constructively to all participants.

3.3. Data analysis

The researcher adopted an exploratory approach to analyse students’ reflective journals. Preliminary themes that emerged during the analysis were coded thematically. The two research aims and questions guided the topic ordering and the construction of themes and sub-themes. Using a thematic content analysis approach (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994; Radnor, Citation2001), the preliminary themes were confirmed as the researcher looked for other thematically similar and relevant examples. However, a few different themes and sub-themes were added through the analysis. To ensure inter-rater reliability, two research assistants in the department were involved in the coding process. The interrater reliability was 0.82, which proves that the analysis of students’ reflective journals was reliable.

3.4. Ethical issues

The current study was guided by BERA ethical guidelines (British Educational Research Association [BERA], Citation2018). First, the participants were informed about the research aims and purposes of the study. Second, participants read and signed an informed consent form voluntarily. Third, issues related to the participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were ensured. Fourth, participants were given the right to withdraw from the study for any reason and at any time. Finally, the participants’ identity was protected by using numbers instead of students’ real names (e.g., S. 19).

4. Findings

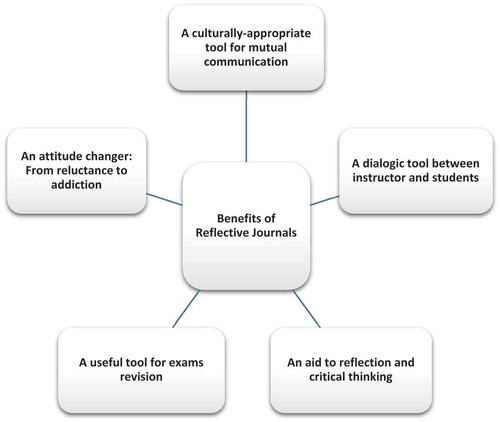

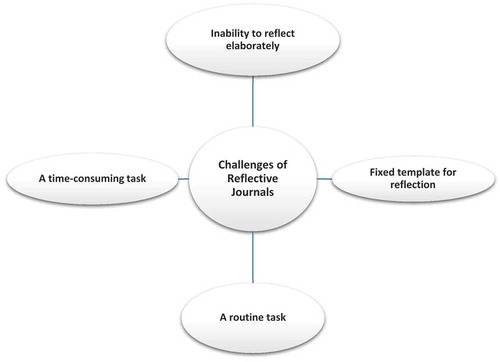

Analysis of students’ reflective journals revealed three themes: students’ reflection on their learning, benefits of reflective journals and challenges with reflective journals.

4.1. Students’ reflection on their learning moments

Participants revealed that they experienced different learning moments through their reflective journals, as shown in .

4.1.1. Engaging moments

Fifty-three participants experienced engaging and fun learning moments in the writing course. A sample journal entry is presented thus:

The three writing classes per week were fun, delight and full of interesting new information and a friendly atmosphere. I enjoyed learning about how to write a newsletter. The lecture time is short (FIFTY minutes only), but I do enjoy it, and that makes me feel like it is even shorter (S. 19, week 7).

4.1.2. Invaluable moments

Forty-four participants experienced invaluable learning moments. A journal entry is presented below:

I considerably developed some new ideas about summary writing and biased writing. I have significantly developed some new strategies to improve the readability and clarity of writing in terms of grammar and content. I realised that we have to avoid many commonly misused words to formulate proper bad news messages (S. 11, week 10).

4.1.3. Surprising moments

Thirty-five participants experienced surprising moments. A sample entry is shown below.

Writing concisely was surprising as I did not know that we can replace many words with two or three words only. I was surprised to know that the simpler writing style, the better. (S. 17, week 6).

4.1.4. Challenging moments

Twenty-two participants experienced challenging moments on different occasions as expressed by the following entries.

… I felt more challenged when asked to paraphrase the writer’s ideas properly (S. 39, week 4).

Unravelling adjective-noun strings was the toughest topic we studied because the technical jargon is beyond our vocabulary (S. 50, week 3).

4.1.5. Novel moments

Nineteen participants experienced new learning moments. A sample entry is presented below:

I love the writing class because I learn something new in every class. For example, avoiding bias in my writing was new, as my biased writing went unnoticed in other courses (S. 22, week 9)

4.1.6. Perplexing moments

Twelve students experienced perplexing moments. A sample entry is presented below:

It was confusing for me to understand the denominalising lesson and activities (S. 29, week 2).

4.1.7. Worrying moments

Eleven students experienced worrying moments. Two sample entries are shown below:

Probably, the number of assignments throughout the course worries me, but I will do my best. (S. 33, week 1).

Simply, anything about grammar causes anxiety. When I get down to specifics, I get lost. It’s an old habit to dislike grammar because of the teacher (S. 42, week 8).

4.1.8. Enlightening moments

Six participants illustrated that using reflective journals is an enlightening process. A sample example is shown below:

I like keeping a reflective journal because it reinforces my learning of what was fully understood and what needs more practice (S. 49, week 11).

4.1.9 Transferrable moments

Commenting on the transfer of learning to other courses, five participants raised the topic of fatty words as exemplified thus:

The topic of fatty words and phrases was very useful as it helped me trim the fatty words and phrases while writing the assignments of other courses (S. 31, week 3).

The reflective journals were successful in portraying a mix of different students’ learning moments. The participants revealed that they experienced some negative feelings, such as feelings of worry, surprise, confusion, and challenge. Moreover, the participants reported their positive emotions of engagement, value, novelty, enlightenment and transferability.

4.2. Benefits of reflective journals

Analysis of findings revealed five benefits of reflective journals, as shown in below.

4.2.1. An attitude changer: from reluctance to addiction

Forty-two participants indicated that a reflective journal changed their attitude from reluctance to addiction. This view is exemplified thus:

I did not want to use reflective journals at the beginning as it is a new type of writing for me. When I started writing regularly and received the teacher’s feedback, I became used to it. Now, I am writing reflective journals for myself in other courses (S.9, week 12).

4.2.2. An aid to reflection and critical thinking

Twenty-eight participants indicated that a reflective journal aided their reflection and critical thinking as exemplified below:

In my high school, I was used to memorising and rote learning, but now I started to be a reflective learner who questions, discusses and argues. This is a new skill that I learnt from this assignment (S. 18, week 13)

4.2.3. A useful tool for exams revision

Nineteen participants illustrated that a reflective journal is useful for exams revision, as shown in the sample example below:

I found out that reflective journals are like a portfolio recording all my reflections on the course weeks. I used reflective journals as a refresher to my memory to revise before exams (S. 44, week 10).

4.2.4. A dialogic tool between instructor and students

Seventeen participants indicated that a reflective journal creates a useful dialogue between the instructor and his students. A sample example is given thus:

The feedback I get from my instructor in my reflective journals is invaluable. He responds by giving some constructive comments, which give me the feeling that my views are valued. It is an interactive, written channel of communication (S. 31, week 9).

4.2.5. A culturally-appropriate tool for mutual communication

Fourteen participants expressed that a reflective journal is a culturally-appropriate tool for mutual communication where the information is kept private and confidential. Two extracts below highlight this benefit:

Female teachers taught me from primary to high school. I feel shy when I am taught by a male teacher. Segregation in education is part of my Qatari culture. Therefore, a reflective journal corresponds properly to our cultural specifics to express my views about learning openly. It is private and confidential between the teacher and me only. This made me write freely and fearlessly about what I like and do not like in class (S. 23, week 5).

4.3. Challenges of reflective journals

Analysis of findings revealed four challenges of reflective journals, as shown in below.

4.3.1. Inability to reflect elaborately

Thirteen participants believed that they were unable to reflect elaborately as exemplified below:

I sometimes find it difficult to elaborate on my answers to the reflective journal questions because I am used to giving brief answers to the questions (S. 3, week 4).

4.3.2. A fixed template for reflection

Twelve participants indicated their dislike of a fixed template as reported below:

I wish I had an open, reflective journal which is not set by the boundaries in the reflective journal template. The questions limit my ability to reflect outside the box. (S. 16, week 13).

4.3.3. A routine task

Ten participants referred to the reflective journal as a routine task as exemplified thus:

The reflective journal assignment is graded upon completion. Therefore, I answer the questions from my viewpoint. It is like an everyday task that you do regularly (S. 35, week 15).

4.3.4. A time-consuming task

Seven participants thought that writing reflective journals was a time-consuming task, as shown below:

I find reflective journals a time-consuming activity that does not add value as it is graded upon completion and does not have an assessment rubric (S.1, week 11).

5. Discussion

This section discusses the findings of the current study: students’ learning moments; benefits of using reflective journals; and challenges with using reflective journals.

5.1. Students’ learning moments

In the present study, the participants reported experiencing some negative learning moments such as challenging, perplexing, and worrying learning moments, whereas, others were positive such as engaging, invaluable, novel, enlightening and transferrable learning moments.

It can be argued that reflective journals are a useful tool that promoted learning and reflection (Chirema, Citation2007). In the Qatari context, reflective journals enabled students to express their viewpoints about instructional practices (Ahmed, Citation2019). In the Emirati context, reflective writing improved students’ conceptual understanding of course content and promoted a growth mindset (Hussein, Citation2018). Furthermore, reflective journals enabled Denton’s students to identify more effective strategies for learning and anxiety management (Denton, Citation2018). Besides, Lee (Citation2013) revealed that reflective journals developed students’ remembering, self-encouragement, and self-realisation. Finally, in the Omani context, reflective journals developed students’ self-regulation strategies (Al-Rawahi & Al-Balushi, Citation2015).

Learning through reflective journals is important as it relates to ‘Optimal Learning’ (Schneider et al., Citation2016) and ‘Significant Learning Moments’ Bruce et al., Citation2011). These optimal/significant learning moments are indicative of the factors that Qatari female undergraduate students perceive as positively impacting on their learning. Students feel more confident, pleased and successful in their learning when they are exposed to challenging tasks which they can manage to accomplish (Schneider et al., Citation2016). Moreover, when students experience more optimal learning opportunities in their classes, they tend to perceive their subject as significant to them and their futures (Schneider et al., Citation2016). Presumably, this scenario applies to the Qatari context, where the participants tend to love their English writing classes when they are exposed to optimal learning opportunities where they can learn and develop their English writing skills in a favourable learning environment.

5.2. Benefits of reflective journals

The participants of the current study revealed the following five benefits of reflective journals: an attitude changer: from reluctance to addiction; an aid to reflection and critical thinking; a useful tool for exams revision; a dialogic tool between instructor and students; and a culturally-appropriate tool for mutual communication.

5.2.1. An attitude changer: from reluctance to addiction

Qatari female participants reported that they were reluctant to use reflective journals at the beginning of the course; however, most participants addicted reflective journaling by the end of the course. This suggests that students changed their unfavourable attitude towards reflective journals to that of a favourable one. Hence, this leads us to question the notion of ‘resistance to change’ as a possible reason for failing to benefit from academic support services and changing their academic behaviours (Dembo & Seli, Citation2004). Based on my experience, two reasons seem to justify Qatari participants’ resistance to change. First, reflective journaling was a new type of assignment to which Qatari students were not used in other courses at university or even in high schools. Second, students’ need for training and practice in using reflective journals may be a plausible reason why the participants resisted to change.

Interestingly, students, who were willing to change, exerted efforts into writing reflective journals and believed in their significance (Cisero, Citation2006). Similarly, students shifted their attitude positively about elderly clients and emphasised that journal writing could elicit students’ feedback on their learning (Williams & Wessel, Citation2004).

5.2.2. An aid to reflection and critical thinking

Some Qatari female undergraduate participants revealed that reflective journals aided their reflection and critical thinking skills. In corroboration with this, Gray (Citation2007) stressed that reflective journals, among other reflection tools, could aid participants’ reflection and consequently act as a mediating factor between experience, knowledge and action.

5.2.3. A useful tool for exams revision

The participants of the current study regarded reflective journals as a useful tool for exam revision. In support of this finding, first-year students reported using their reflective journals to revise from the different questions on their readings along with students-made questions Beveridge (Citation1997). Interestingly, Varner & Peck (Citation2003) signalled the importance of reflective journals and recommended using them to measure students’ knowledge and application of those concepts as substitutes for exams.

5.2.4. A dialogic tool between instructor and students

The participants of the current study considered reflective journals as a dialogic tool between instructor and students. This finding is important as it resonates with the concept of dialogic education, which Wegerif (Citation2006) viewed as a way of writing, a way of knowing and shared enquiry. It is important to teach our students in all educational stages to engage in dialogues where knowledge is continually constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed (Wegerif Citation2006). However, it is recommended that teachers use reflective journals with care paying much attention to addressing students’ sensitive and confidential issues (O’Connell & Dyment, Citation2011).

5.2.5. A culturally-appropriate tool for mutual communication

The participants of the current study revealed that reflective journaling is a culturally-appropriate tool for mutual communication between male teachers and female students in a conservative community. This finding is substantiated by previous research in which Qatari students used reflective journals to express and discuss their viewpoints openly about their teachers’ instructional practices (Ahmed, Citation2019). In Jordan, the researchers referred to the participants’ difficulty to talk freely during the interviews as they might be overheard by their relatives in clinical settings (Al-Amer et al., Citation2019). The researchers attribute this problematic issue to the collectivist culture of the Arab communities (Al-Amer et al., Citation2019).

5.3. Challenges with reflective journals

The participants of the current study revealed four challenges with using reflective journals: inability to reflect elaborately; a fixed template for reflection; a routine task; and a time-consuming task. It is crucial to identify these challenges so that teachers can address them and provide the participants with an optimal learning environment.

The first challenge from which some participants complained is their inability to reflect elaborately. This finding suggests that the participants are not accustomed to writing reflectively in other university courses or at high school. These participants fall in the category of ‘non-reflectors’; participants can summarise and describe the concepts, but they lack the assessment of their learning (Kember et al., Citation1999). In support of this finding, Mallek et al. (Citation2019) showed that female Emirati students scored lower than their male counterparts in the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT). In another study, international students from high-power distance cultures found it difficult to reflect critically in writing or challenge the reading materials or instructors (Varner & Peck, Citation2003). However, Al-Hazmi (Citation2006) reported that 19 Saudi undergraduate students critically reflected on their learning in Arabic and English in an English writing course.

Students’ unease with using a fixed template for reflection is the second challenge. These participants felt that the reflection template does not give them a personal space where they can reflect openly. In uniformity with that, Nicol and Dosser (Citation2016) believed that some participants preferred a structured model for reflection such as Gibb’s Cycle (Gibbs, Citation1988). On the other hand, Goodyear et al. (Citation2013) indicated that trainees poorly completed the structured reflection form. This denotes that the context plays a vital role in deciding to use a structured or an unstructured reflective journal.

Viewing the reflective journal as a routine work that lost its value is the third reported challenge. This finding is similar to those students who thought that reflective journaling is an irritating work that lost its place in the educational arena (O’Connell & Dyment, Citation2011). Some reasons for not finding reflective writing interesting are not framing the reflective journals properly (Thorpe, Citation2004), students’ inability to demonstrate learning because of their prior education that does not cater for developing reflective writing (Blaise et al., Citation2004; K. Fisher, Citation2003), and using traditional exams that contrast with the nature of reflection (O’Connell and Dyment (Citation2011)

Finally, the participants regarded reflective journals as a time-consuming task. Three reasons might justify why reflective journaling is a time-consuming activity for some students: students disliked reflective journaling and found it time-consuming (Otienoh, Citation2009); some other students may procrastinate writing their journals to the last minute (Anderson, Citation1992); the big number of reflective journals required from students might make reflective journals a time-consuming task (Dunlap, Citation2006). Based on my teaching experience in the Qatari context and other Arab contexts, I can tell that few students might submit their assignments late due to procrastination.

6. Implications, recommendations and conclusion

The current research is limited by some issues. First, a sample size of 50 undergraduate participants and 3 English writing instructors is quite small. Second, this research is limited by gender, as only female participants took part in the current study. Third, collecting data through one research instrument only (i.e. reflective journals) could be a limitation. In the next few lines, I am proposing some insightful implications for the use of reflective journals to inform teachers and stakeholders’ decision-making and pedagogical change.

First, reflection is an essential 21st century skill that needs to be incorporated into undergraduate education at university. At the university level, reflection helps students become lifelong learners who link theory to practice (Rogers, Citation2001). It also helps students make learning more relevant, meaningful and contextualised (Higgins, Citation2011). At the professional level, reflection prepares students for their professional contexts (Phan, Citation2007).

Second, university instructors and stakeholders need to strengthen and develop the factors that promote and support students’ learning and properly address those factors that hinder students’ learning. Consequently, students will be provided with an optimal learning experience where they perceive the significance of their learning and become confident learners (Schneider et al., Citation2016).

Third, university instructors and stakeholders need to seriously consider students’ voice while teaching and assessing students at different educational stages. Moreover, instructors need to seek professional development opportunities that embellish students’ positive learning moments of engagement, enlightenment, value, novelty and learning transfer; and diminish students’ negative learning moments of worry, surprise, and confusion.

Additionally, the five benefits of reflective journals reported by the study participants imply that the use of reflective journals is significant to hear students’ voice to express their views openly on their university learning and ensure that their views are not absent in important decision-making processes and pedagogical innovations.

Finally, the challenges associated with the participants’ use of reflective journals suggest some issues. First, the method and process of writing reflective journals need scaffolding and facilitation to help students reflect smoothly. Second, students need to be able to choose either structured or unstructured reflective journals to enable them to reflect on whatever convenient channel to them. Third, variation in the reflective journals questions is required to avoid the boredom. Finally, the weekly reflective journals need to be bi-monthly per semester, along with a final reflection paper. The journals reduced number will lessen the pressure on students and make them value journaling.

The current research suggests conducting future research in the following areas. First, male students’ voice needs to be heard about their own learning and concerns at the university level. Another possible study could measure the reflection level of both male and female students at the university level. Besides, a study could explore students’ learning types: surface or deep learning. Moreover, a cross-cultural study exploring the impact and challenges of reflective journals across cultures on students’ learning is recommended. Finally, an interdisciplinary study is needed to examine the impact and challenges of reflective journals across disciplines.

The current study contributed to a deeper understanding of reflective journals to hear students’ voice on their learning and the challenges associated with reflective journals. The current research provided evidence that students, when given a chance, can reveal their perspectives about their own learning openly, freely and confidently through the use of reflective journals.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Core Curriculum Program at Qatar University for funding my conference presentation at the 21st Century Academic Forum, Martin Conference Center, Harvard University, Boston, USA, 20–22 March 2016, in which I presented the research findings of the current study. I would also like to thank Qatar National Library (QNL) for funding the Article Publication Charges (APCs) and making this article open access.

I would also like to thank Prof. Debra Myhill, Professor of Education, and Dr. Esmaeel Abdollahzadeh, Senior Lecturer in TESOL, Graduate School of Education, University of Exeter, UK, for their insightful feedback and review of the first draft of this research paper. Finally, I would like to thank the editor and associate editor of Reflective Practice along with the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and review of this research paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Abdelhamid M. Ahmed

Dr. Abdelhamid M. Ahmed is a Lecturer of Education at the Core Curriculum Program, Qatar University. He obtained his PhD in Education (TESOL/Applied Linguistics), Graduate School of Education, University of Exeter, UK. His areas of research expertise include L2 English writing problems, socio-cultural issues, assessing writing, feedback in L2 writing, and reflective journals. He is the co-editor of the following books: Teaching EFL Writing in the 21st Century Arab World: Realities & Challenges; Assessing EFL Writing in the 21st Century Arab World: Revealing the Unknown; Tradition Shaping Change: General Education in the Middle East and North Africa; and Feedback in L2 English Writing in the Arab World: Inside the Black Box.

References

- Abednia, A., Hovassapian, A., Teimournezhad, S., & Ghanbari, N. (2013). Reflective journal writing: Exploring in-service EFL teachers’ perceptions. System, 41(3), 503–514. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0346251X13000687

- Ahmed, A. (2010). Students’ problems with cohesion and coherence in EFL essay writing in Egypt: Different perspectives. Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal (LICEJ), 1(4), 211–221. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b8f7/8d637f4f3a78cfb4b652c3d23d82a3819e77.pdf

- Ahmed, A. (2019). Students’ reflective journaling: An impactful strategy that informs instructional practices in an EFL writing university context in Qatar. Reflective Practice, 20(4), 483–500. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14623943.2019.1638246

- Al-Amer, R., Ramjan, L., Glew, P., Darwish, T., Randall, S., & Salamonson, Y. (2019). A reflection on the challenges in interviewing Arab participants. Nurse Researcher, 27(2), 19–22. Retrieved from https://journals.rcni.com/nurse-researcher/evidence-and-practice/a-reflection-on-the-challenges-in-interviewing-arab-participants-nr.2018.e1559/abs

- Al-Hazmi, S. (2006). Writing and reflection: Perceptions of Arab EFL learners. South Asian Language Review, 16(2), 36–52.

- Al-Rawahi, N., & Al-Balushi, S. (2015). The effect of reflective science journal writing on students’ self-regulated learning strategies. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 10(3), 367–379. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1069260

- Alsaleem, B. (2013). The effect of” whatsapp” electronic dialogue journaling on improving writing vocabulary word choice and voice of EFL undergraduate Saudi students. Arab World English Journal, 4(3), 213–225. Retrieved from http://www.21caf.org/uploads/1/3/5/2/13527682/alsaleem-hrd-conference_proceedings.pdf

- Anderson, J. (1992). Journal writing: The promise and the reality. Journal of Reading, 36(4), 304–309. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40016635?seq=1

- Andrews, T. (2012). What is social constructionism? Grounded Theory Review, 11(1), 39–46. Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com/2012/06/01/what-is-social-constructionism/

- Bass, J., Fenwick, J., & Sidebotham, M. (2017). Development of a model of holistic reflection to facilitate transformative learning in student midwives. Women and Birth, 30(3), 227–235. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28359752

- Bell, A., Kelton, J., McDonagh, N., Mladenovic, R., & Morrison, K. (2011). A critical evaluation of the usefulness of a coding scheme to categorise levels of reflective thinking. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(7), 797–815. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02602938.2010.488795

- Bennett, D., Power, A., Thomson, C., Mason, B., & Bartleet, B. (2016). Reflection for learning, learning for reflection: Developing indigenous competencies in higher education. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 13, 2. Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1656&context=jutlp

- Beveridge, I. (1997). Teaching your students to think reflectively: The case for reflective journals. Teaching in Higher Education, 2(1), 33–43. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1356251970020103

- Blaise, M., Dole, S., Latham, G., Malone, K., Faulkner, J., & Lang, J. (2004). Rethinking reflective journals in teacher education [Paper presentation]. Australian Association of Researchers in Education (AARE), Melbourne, Vic.

- British Educational Research Association [BERA]. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchersresources/publications/ethicalguidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2007). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education. (2nd ed.). Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Bruce, C., McPherson, R., Sabeti, F., & Flynn, T. (2011). Revealing significant learning moments with interactive whiteboards in mathematics. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 45(4), 433–454. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2190/ec.45.4.d

- Chang, M., & Lin, M. (2014). The effect of reflective learning e-journals on reading comprehension and communication in language learning. Computers & Education, 71, 124–132. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S036013151300287X

- Chirema, K. (2007). The use of reflective journals in the promotion of reflection and learning in post-registration nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 27(3), 192–202. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0260691706000591

- Chitpin, S. (2006). The use of reflective journal keeping in a teacher education program: A popperian analysis. Reflective Practice, 7(1), 73–86. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623940500489757

- Cisero, C. (2006). Does reflective journal writing improve course performance? College Teaching, 54(2), 231–236. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/CTCH.54.2.231-236

- Craft, M. (2005). Reflective writing and nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(2), 53–57. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/fd01fb1ff52d16f735453a6e4a1d9a53/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=47628

- Dembo, M., & Seli, H. (2004). Students’ resistance to change in learning strategies courses. Journal of Developmental Education, 27(3), 2. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ718559

- Denton, A. (2018). The use of a reflective learning journal in an introductory statistics course. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 17(1), 84–93. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1475725717728676

- Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Dunlap, J. (2006). Using guided reflective journaling activities to capture students’ changing perceptions. TechTrends, 50(6), 20–26. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11528-006-7614-x

- Durgahee, T. (1998). Facilitating reflection: From a sage on stage to a guide on the side. Nurse Education Today, 18, 158–164. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S026069179880021X

- Fisher, K. (2003). Demystifying critical reflection: Defining criteria for assessment. Higher Education Research and Development, 22(3), 313–325. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0729436032000145167

- Fisher, R. (2005). Teaching Children to Think. Nelson Thornes.

- Fullanaa, J., Palliseraa, M., Colomerb, J., Peñac, R., & Pérez-Burrield, M. (2016). Reflective learning in higher education: A qualitative study on students’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education, 41(6), 1008–1022. Retrieved from https://srhe.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03075079.2014.950563#.Xl6r3qgzY2w

- Gibbs, G. 1988. Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic.

- Goodyear, H., Bindal, T., & Wall, D. (2013). How useful are structured electronic Portfolio templates to encourage reflective practice?. Medical Teacher, 35(1), 71–73. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/0142159X.2012.732246

- Gray, D. (2007). Facilitating management learning: Developing critical reflection through reflective tools. Management Learning, 38(5), 495–517. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1350507607083204

- Hatcher, J., & Bringle, R. (1997). Reflection: Bridging the gap between service and learning. College Teaching, 45(4), 153–159. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/87567559709596221

- Heath, H. (1998). Keeping a reflective practice diary: A practical guide. Nurse Education Today, 18, 592–598. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0260691798800105

- Helyer, R. (2015). Learning through reflection: The critical role of reflection in work-based learning. (WBL). Journal of Work-Applied Management, 7(1), 15–27. Retrieved from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JWAM-10-2015-003/full/html

- Higgins, D. (2011). Why reflect? Recognising the link between learning and reflection. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 12(5), 583–584. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623943.2011.606693

- Hussein, H. (2018). Examining the effects of reflective journals on students’ growth mindset: A case study of tertiary level EFL students in the United Arab Emirates. IAFOR Journal of Education, 6(2), 33–50. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1181055

- Johns, C. (1994). Nuances of reflection. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 3, 71–75. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2702.1994.tb00364.x

- Kember, D., Jones, A., Loke, A., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., Tse, H., ... Yeung, E. (1999). Determining the level of reflective thinking from students’ written journals using a coding scheme based on the work of Mezirow. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 18(1), 18–30. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/026013799293928?needAccess=true

- Lee, S. (2013). Effects of reflective journal writing in Japanese students’ language learning. [Unpublished MA thesis]. The Indiana University of Pennsylvania, School of Graduate Studies and Research.

- Loo, R. (2002). Journaling: A learning tool for project management training and team-building. Project Management Journal, 33(4), 61–66. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/875697280203300407

- Mallek, R., Albaity, M., & McMillan, D. (2019). Individual differences and cognitive reflection across gender and nationality: The case of the United Arab Emirates. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1567965. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23322039.2019.1567965

- McDermott, C., Shank, K., Shervinskie, C., & Gonzalo, J. (2019). Developing a professional identity as a change agent early in medical school: The students’ voice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(5), 750–753.

- Messiou, K. (2019). The missing voices: Students as a catalyst for promoting inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–14. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13603116.2019.1623326

- Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Moon, J. (2006). Learning journals: A handbook for reflective practice and professional development. Routledge.

- Nicol, J., & Dosser, I. (2016). Understanding reflective practice. Nursing Standard, 30(36), 34–42. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/97e5ef2277590e5454a8ed6e54f3bfe2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2042228

- O’Connell, T., & Dyment, J. (2011). The case of reflective journals: Is the jury still out? Reflective Practice, 12(1), 47–59. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623943.2011.541093

- Otienoh, R. (2009). Reflective practice: The challenge of journal writing. Reflective Practice, 10(4), 477–489. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623940903138332

- Pavlovich, K. (2007). The development of reflective practice through student journals. Higher Education Research & Development, 26(3), 281–295. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07294360701494302

- Phan, H. (2007). An examination of reflective thinking, learning approaches, and self‐efficacy beliefs at the University of the South Pacific: A path analysis approach. Educational Psychology, 27(6), 789–806. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01443410701349809

- Pritchard, A., & Woollard, J. (2010). Psychology for the classroom: Constructivism and social learning. Routledge.

- Radnor, H. (2001). Researching your professional practice. Open University Press.

- Rogers, R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37–57. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1010986404527

- Romanowski, M., & Al-Hassan, S. (2013). Arab middle eastern women in Qatar and their perspectives on the barriers to leadership: Incorporating transformative learning theory to improve leadership skills. Near and Middle Eastern Journal of Research in Education, 1, 3. Retrieved from https://www.qscience.com/content/journals/10.5339/nmejre.2013.3

- Rué, J., Font, A., & Cebrián, G. (2013). Towards high-quality reflective learning amongst law undergraduate students: Analysing students’ reflective journals during a problem-based learning course. Quality in Higher Education, 19(2), 191–209. Retrieved from https://srhe.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13538322.2013.802575#.Xl6ydqgzY2w

- Ryan, M., & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 244–257. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

- Schneider, B., Krajcik, J., Lavonen, J., Salmela‐Aro, K., Broda, M., Spicer, J., ... Viljaranta, J. (2016). Investigating optimal learning moments in US and Finnish science classes. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53(3), 400–421. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/tea.21306

- Seale, J. (2009). Doing student voice work in higher education: An exploration of the value of participatory methods. British Educational Research Journal, 36(6), 995–1015. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01411920903342038

- Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analysing talk, text and interaction. Sage Publications.

- Simpson, E., & Courtney, M. (2007). A framework guiding critical thinking through reflective journal documentation: A Middle Eastern experience. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13(4), 203–208. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2007.00629.x

- Thorpe, K. (2004). Reflective learning journals: From concept to practice. Reflective Practice, 5(3), 327–343. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1462394042000270655

- Tsang, A. (2003). Journaling from internship to practice teaching. Reflective Practice, 4, 221–240. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14623940308269

- Turhan, B., & Kirkgoz, Y. (2018). Towards becoming critical reflection writers: A case of English language teacher candidates. Reflective Practice, 19 (6),749–762. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14623943.2018.1539651

- Varner, D., & Peck, S. (2003). Learning from learning journals: The benefits and challenges of using learning journal assignments. Journal of Management Education, 27(1), 52–77. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1052562902239248

- Wegerif, R. (2006). Dialogic Education: What is it, and why do we need it? Education Review, 19, 2. Retrieved from https://web.a.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=14627272&asa=Y&AN=23074711&h=nVPyvro%2bCa8Uir2Q9zuIGSfEOqP86z9HGHmwaw6Ix0bmymPpOuziBZLM8peJienh96iUZOQwux%2bn8heMSyVygA%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d14627272%26asa%3dY%26AN%3d23074711

- Williams, R., & Wessel, J. (2004). Reflective journal writing to obtain student feedback about their learning during the study of chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Journal of Allied Health, 33(1), 17–23. Retrieved from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asahp/jah/2004/00000033/00000001/art00004