ABSTRACT

This study aimed to describe self-rated reflective capacity in students enrolled in post-registration specialist nursing education at the advanced level. We applied a non-experimental and cross-sectional design. A survey of 156 specialist nursing students at two universities in Northern Sweden was conducted. Data were collected in 2019 using a web-based questionnaire assessing self-rated reflective capacity through the Reflective Capacity Scale of the Reflective Practice Questionnaire. Data were analyzed descriptively using frequencies and proportions. Correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s rho. Results show that students specializing in psychiatric care and oncological care report a higher reflective capacity than students specializing in other areas. We found no significant correlations between reflective capacity and gender, and reflective capacity in total did not correlate with age or work experience. We conclude that reflective capacity might vary between nursing students in different areas of specialization. Further research is needed to understand causes and impacts of variations in nursing students’ reflective capacities.

Introduction

The complex, changing and unpredictable nature of nursing practice requires nurses to be able to adapt to the situation at hand and learn from experience. Thus, nursing is considered a ‘reflective practice’ (Goulet et al., Citation2016), and the development of reflective capacity in nurses and nursing students is considered desirable. Reflective capacity can be understood as ‘the ability, desire, and tendency of students to engage in reflective thought during their academic studies and clinical practices’ (Rogers et al., Citation2019, p. 1). The focus of this study was to explore prevalence and variations in self-reported reflective capacity in students enrolled in post-registration specialist nursing education at the advanced level. We believe this to be a first step towards understanding more about how educational needs of specialist nursing students might vary depending on factors, such as specialization, age, experience, and gender.

Background

The concept of reflective capacity is relevant for specialist nursing education as it might have implications both for students learning as well as their future practice. Reflective practice is regarded as the integration of theory and practice, a requisite for personal and professional development, and a strategy for fostering person-centred approaches to care (Goulet et al., Citation2016). Reflection may be most useful when viewed as a learning strategy (Mann et al., Citation2009); in this way, it may assist nurses and nursing students to connect and integrate new learning to existing knowledge and skills. Reflection may also help nurses and nursing students to explicitly integrate the affective aspects of their learning. Mann et al. (Citation2009) identified modest evidence that reflective practice can be developed and that improved reflective ability is associated with systematic attempts to develop it. The factors that have been associated with its successful development appear to be a facilitating context, a safe atmosphere, mentorship and supervision, peer support and time to reflect (Mann et al., Citation2009). While pedagogical approaches to teaching reflection in nursing typically focus on written reflection, engaging students used to constant access to digital technology in reflection might require the creative use of digital media (Newton & Butler, Citation2019).

Reflection is considered a defining feature of nurses’ clinical judgment and a key concern for nursing education (Klenke-Borgmann et al., Citation2020). Further, it is an important element of effective empathy education in nursing education (Levett-Jones et al., Citation2019) and considered significant for fostering students’ compassion (Younas & Maddigan, Citation2019). As shown by Fragkos (Citation2016), many reflective techniques used in health-care education can be associated with deep learning, understanding, attitudes, beliefs, and satisfaction. Reflective writing can enhance student nurses’ reasoning skills and awareness in clinical situations (Bjerkvik & Hilli, Citation2019). Further, reflection appears to be positively associated with various learning outcomes, for example, improved technical skills, increased self-awareness and increased interpersonal, perceptual and relational skills (Fragkos, Citation2016).

There is also evidence that self-reflective practices have positive effects on nursing students in terms of decreased stress and anxiety, and increased learning, competency, and self-awareness (Contreras et al., Citation2020). Reflective ability, a subset of reflective capacity, is considered a key characteristic of resilient behaviour, and research has suggested that by focusing on reflective ability, nursing education can foster resilient practices (Walsh et al., Citation2020). Nursing students’ over-confidence in their own abilities can limit their capacities to reflect on their own practice (Hughes et al., Citation2016), and nursing students who fail clinical practice typically demonstrate an inability to reflect on practice, which contributes to a lack of self-awareness (Scanlan & Chernomas, Citation2016).

In clinical settings, reflective practice is often referred to as the theoretical foundation for nurse-mentoring programmes (Hoover et al., Citation2020), in which mentees are encouraged to engage in critical reflection to facilitate professional development. Reflection is also considered a defining characteristic of adequate and effective clinical supervision in nursing (Howard & Eddy‐Imishue, Citation2020). The existing literature has suggested positive effects of clinical supervision, although further research is needed to evaluate its impact (Cutcliffe et al., Citation2018). Clinical supervision in the form of reflective practice groups has been reported to promote self-awareness, clinical insight, and quality of care (Dawber, Citation2013; Dawber & O’Brien, Citation2014) and to facilitate stress management and team-building (Dawber, Citation2013; O’Neill et al., Citation2019). In addition, written narratives have been suggested as a strategy to enhance nurses’ reflective practices (Choperena et al., Citation2019).

Reflective capacity has been conceptualized as incorporating four dimensions of reflection: reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, reflection with others, and self-appraisal (Rogers et al., Citation2019). The concepts of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action are derived from the theories on reflective practice introduced by Schön (Citation1983, Citation1987). Professional practice requires practitioners to be able to adapt to novel and unique situations. This is done through the process of reflection-in-action in which the initial understanding of a situation is challenged, and a new understanding is constructed and tested (Schön, Citation1983). Reflection-on-action refers to the ability and willingness to learn from experiences (Ghaye & Lillyman, Citation2010). Reflection with others in formal supervision or with peers serve to facilitate insight and understanding, while self-appraisal involves reflecting upon and questioning one’s capabilities for practice (Rogers et al., Citation2019). Previous research on reflective capacity report a correlation between the ability, desire, and tendency to engage in reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, reflection with others and self-appraisal (Priddis & Rogers, Citation2018). Using the Reflective Practice Questionnaire (RPQ), Rogers et al. (Citation2019) identified various degrees of reflective capacity in general public (3.51), medical student (4.16), and mental-health practitioner samples (4.27).

Reflective capacity is considered essential for nursing education and practice. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have focused on specialist nursing students reflective capacities. Overall, the research on the relationship between reflective capacity and gender, age, work experience and area of specialisation is scarce. It is possible that different areas of specialization provide and require different prerequisites for developing reflective capacity or that the necessity of reflective capacity varies between specialities. It might also be that different areas of specialization attract nurses with different aptitudes for or interests in reflective thinking. Understanding if, how and why reflective capacity varies among nurses can help inform nursing education and practice.

Aim

This study aimed to describe self-rated reflective capacity in students enrolled in post-registration specialist nursing education at the advanced level.

Materials and methods

Design

The design of this study was cross-sectional and data were collected using a web-based questionnaire. The design was chosen to study self-rated reflective capacity in registered nurses at a single point in time and to make comparisons possible between specific groups in the population. The reporting of this study follows the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies (Von Elm et al., Citation2008).

Participants and setting

The selection of study participants was consecutive, and the sample-comprised students currently enrolled in post-registration specialist nursing education at the advanced level at two universities in Northern Sweden in March 2019. All students were registered nurses with clinical experience. A total of 306 students enrolled in specialist nursing education at the advanced level were invited to participate in the study, and 156 completed questionnaires were received.

In Sweden, education to become a registered nurse requires three years of study and leads to an academic exam at the bachelor’s level (180 ECTS). Following undergraduate education, a number of advanced-level specialist education programmes are offered at universities. The duration of an advanced-level specialist education is usually one year (60 ECTS) and leads to a master’s degree in one of a number of specialties that include anesthesiology nursing, intensive care nursing, perioperative nursing, prehospital nursing, psychiatric nursing, pediatric nursing, oncological nursing, or elderly-care nursing. Furthermore, there are two longer specializations in primary health care (75 ECTS) and midwifery (90 ECTS).

Data collection

Data collection took place during March and April 2019, and the electronic survey was dispatched by email to the study population with two subsequent waves of reminders.

Data were collected through an electronic survey that comprised the Reflective Capacity Scale of the Reflective Practice Questionnaire (RCS-RPQ) previously developed and psychometrically tested by Priddis and Rogers (Citation2018). The RCS-RPQ comprises four sub-components with four items pertaining to each sub-component: reflective-in-action, reflective-on-action, reflective with others, and self-appraisal. The scoring of the RCS-RPQ follows a six-point Likert-type scale: (1) Not at all, (2) Slightly, (3) Somewhat, (4) Moderately, (5) Very much, (6) Extremely. The four items of each sub-component are then averaged to provide the sub-component score, and the full 16 items are averaged to provide the average score for the scale as a whole (cf., Rogers et al., Citation2019). Higher scores on the RCS-RPQ indicate a higher reflective capacity. The RCS-RPQ in the survey was followed by questions about the demographic profiles of the study participants, such as age, gender, working experience, advanced-level specialist education enrolment and previous specialist education. Using the same data set as this study, Gustafsson et al. (Citation2021) found the Swedish version of the RCS-RPQ to be a valid and reliable instrument that assesses the self-rated reflective capacity of health-care practitioners. The overall Chronbach Alpha value for the Swedish version of the RCS-RPQ was 0.915 and for the sub-components 0.737 (reflective-in-action), 0.824 (reflective-on-action), 0.832 (reflective with others), and 0.784 (self-appraisal). Corrected item-total correlations were positive and >0.30.

In the original instrument developed by Priddis and Rogers (Citation2018), the term ‘clients’ is used to describe the interaction between care seekers and health-care practitioners. However, they argue that the RCS-RPQ can be used across different professions since interactions may be with ‘clients, patients, customers, patrons, students, or any other term a profession uses to describe the recipients of the service’ (p. 4). In this study, the term ‘patients’ is used.

Data analysis

Data from the electronic survey were entered into the statistical programme SPSS version 26 and then analysed descriptively using frequencies and proportions. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality indicated that data for the sub-components were not normally distributed. Correlations and comparisons between groups were therefore analysed using non-parametric methods. Comparisons between groups were presented descriptively using means but analyzed statistically using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney’s U-test. Correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s rho. Significance was set at 5% and missing data was excluded from the analysis.

Ethical considerations

This study adhered to ethical principles of informed consent and confidentiality. As this study was based on non-sensitive data, according to Swedish law no formal ethical approval was required.

Results

A total of 156 completed questionnaires were returned, resulting in a response rate of 50.98%. Characteristics of study participants are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample

Reflective capacity

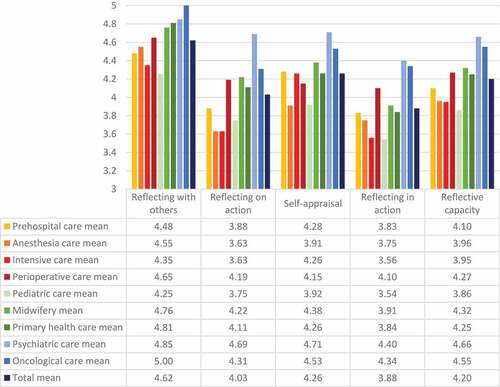

In the sample of specialist nursing students, the mean self-rated reflective capacity for the group total was 4.20 (SD 0.72). For the sub-components, the means for the group total were 4.62 (SD 0.83) for reflective with others, 4.03 (SD 0.90) for reflective-on-action, 4.26 (SD 0.84) for self-appraisal and 3.88 (SD 0.82) for reflective-in-action.

Gender

No significant differences in self-rated reflective capacity were found in relation to respondent gender (). There is a tendency that women rated their reflective capacity higher than men for all sub-components except self-appraisal, but this tendency was not significant.

Table 2. Gender differences in self-rated reflective capacity in post-registration specialist nursing students

Age and work experience

There were no significant correlations between age and the sub-components reflective with others, self-appraisal or reflective-on-action or with reflective capacity in total (). A weak but significant correlation was found between age and reflective-in-action. No significant correlations were found between work experience and the sub-components reflective with others, reflective-on-action or reflective-in-action nor with total reflective capacity. For the sub-component self-appraisal, a weak but significant positive correlation with work experience was found.

Table 3. Correlations between self-rated reflective capacity and age and work experience in post-registration specialist nursing students

Multiple specializations

Prior to their current enrolment at the university, 12 students had an advanced-level specialist education, whilst 144 students were registered nurses without prior advanced-level specialist education. No significant differences in means between registered nurses and nurses with prior specializations were found ().

Table 4. Differences in self-rated reflective capacity in post-registration specialist nursing students between undergraduate nurses and nurses with prior specialization

Area of specialization

Differences in self-rated reflective capacity depending on ongoing specialist programme are presented in . The specialist programmes in oncological care and psychiatric care are characterized by consistently higher mean self-rated reflective capacity than other specialist programmes.

Discussion

We aimed to study self-rated reflective capacity in students enrolled in post-registration specialist nursing education at the advanced level and, specifically, the impact of gender, age, experience, multiple specializations, and focus of specialization. We found no significant correlations between reflective capacity and gender, and reflective capacity in total did not correlate with age or work experience. Our findings suggest that students specializing in psychiatric care and oncological care report a higher reflective capacity than students specializing in other nursing areas.

Overall, our study suggests that our sample of specialist nursing students tends to have a higher degree of reflective capacity (4.20) than that of the general public (3.51) and on par with that of medical student (4.16) and mental-health practitioner samples (4.27) as reported by Rogers et al. (Citation2019). Reflective capacity in total did not correlate with gender, age, or experience, although the sub-component reflective-in-action correlated positively with age and self-appraisal with work experience. Female participants tended to rate their reflective capacity higher than men, but this difference was not significant. Ottenberg et al. (Citation2016) found that female medical students tended to express higher reflective capacity scores compared to male students. More studies with a larger sample size are needed to draw any firm conclusion about the relationship between gender and reflective capacity, and to explore whether potential differences are clinically relevant. As our sample presented only 12 participants with prior specialization, we are not able to make any valid conclusions on the impact of multiple specializations on differences in reflective capacity.

Our main finding is that specialist nursing students’ reflective capacity varies between different areas of specialization. Our findings describe students specializing in psychiatric care and oncological care as reporting a higher reflective capacity than students in emergency care specializations, especially intensive care. We believe this suggests a number of possibilities to be considered in nursing education and practice, and that warrant further research. The differences in reflective capacity between specialties reported in our study might reflect differences in culture and tradition. Clinical supervision has a long-standing tradition in psychiatric nursing (Buus & Gonge, Citation2009) which might indicate that psychiatric nurses are expected to be highly reflective. However, clinical supervision is also considered a common phenomenon in nursing in general (Cutcliffe et al., Citation2018). Differences might also reflect different practice environments. Nurses of various specialties may experience staff shortages, oppressive ward cultures, and other working conditions that can hinder reflection. There are, however, several fundamental differences between how work is typically organized in, for example, psychiatric or oncology inpatient units, on the one hand, and intensive care units on the other. For example, psychiatric and oncological care might be more prone to intra- and interdisciplinary discussions relating to patients’ subjective and existential experiences, while intensive care might be more focused on responding to vital objective findings bedside. We find it reasonable to assume that such differences might account for some of the differences in reflective capacity in our results. Likewise, differences in reflective capacity might reflect differences in the curricula for various specialist programmes. For example, psychiatric and oncology nursing programmes might emphasize the need for reflection on interpersonal and ethical aspects of nursing, while intensive care programmes might want to prioritize the integration of the medical and technical aspects of care. We further suggest that differences in reflective capacity might reflect the attraction of different nursing specialties to different personalities. For example, mental health nursing is considered the least attractive career option amongst undergraduate nursing students (Happell & Gaskin, Citation2013), and a review of the literature found that there might be differences in personality between nurses in different specialties (Kennedy et al., Citation2014). It seems plausible that, for example, many intensive care nurses possess a somewhat different mindset than oncology nurses, and that this, to some extent, is related to reflective capacity.

There is also the possibility, of course, that differences in reflective capacity between specialties in our findings reflect how the actual need for reflective capacity differs between specializations, for example, the interpersonal nature of mental health or oncological nursing calls for careful considerations and reflection, while the technical and acute nature of intensive care calls for decisiveness and action. Interpersonal relationships in nursing requires empathy, and empathy requires that nurses are able to reflect on their own feelings and on the patients perspective (Lakeman, Citation2020). Thus, some nursing specialties might place higher demands on nurses capacity for reflection in order to deliver emphatic and compassionate care. There is, however, a risk that such assumptions merely reflect uninformed and outdated conceptualizations of nursing. Nurses of all specialties in today’s health-care environments need to apply professional judgment and take action in response to complex needs. Thus, our findings might reflect that acute-care nursing education and practice might benefit from further emphasising fostering reflective capacity in specialist nurses and nursing students.

Study limitations

We do not know to what extent the results reflect differences in academic curricula between specializations, differences between students’ workplaces before and during undertaking advanced nursing studies, or variations in characteristics of nurses choosing to pursue different specializations. The small sample sizes of the different subgroups increase the risk of type II errors and motivate further research with a larger population. In addition, the relatively small number of male participants makes it difficult to draw any conclusion about the impact of gender on self-rated reflective capacity. Self-reports of perceived capacity are always problematic, as it is possible that students with low reflective capacity might lack self-awareness, which is the ability to think about one’s own practice from a critical perspective. It is, therefore, possible that they overestimate their own abilities (c.f. Scanlan & Chernomas, Citation2016). This could imply that students who are highly self-aware may underestimate their abilities as they are conscious of their own shortcomings.

Conclusion

This study suggests that reflective capacity might vary between nursing students in different areas of specialization. Further research is needed to understand the possible causes and impacts of variations in nursing students’ reflective capacities. The study highlights differences in reflective capacity that might need to be considered when organizing and facilitating nurses and nursing students’ learning. To benefit from outcomes, such as improved technical skills, increased self-awareness and increased interpersonal, perceptual, and relational skills that are established based on nurses’ reflective capacities, we suggest that educators and managers value and further develop opportunities for reflection in both education and practice.

Authorship

All authors were responsible for the study’s original conception and design. SeG, SiG, and ÅE were responsible for the translation procedure. SiG was responsible for data collection with the participation of SeG, ÅE, and BL. SiG performed the statistical analysis with the participation of SeG. Interpretations of data were discussed and revised with the input of all authors. SeG and SiG drafted the manuscript, which was then revised with the input of all authors. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the valuable contribution of Dr. Helena Backman in reviewing and commenting on the statistical analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sebastian Gabrielsson

Sebastian Gabrielsson is Associate Professor in Nursing at Luleå University of Technology, and a registered nurse specialized in psychiatric care. He has a clinical background in acute psychiatric care. His research uses qualitative and mixed methods and include both professional and service user perspectives. Areas of special interest include psychiatric inpatient care and inpatient mental health nursing, and reflective and recovery-oriented practices.

Åsa Engström

Åsa Engström is Professor in Nursing at Luleå University of Technology. She has a PhD and a master’s degree in nursing, and is a registered nurse with specialization in intensive care nursing. Åsa Engström is the vice chairman of the Swedish Nurses’ Association. Her research interests are within nursing care, foremost within intensive care nursing

Britt-Marie Lindgren

Britt-Marie Lindgren is an Associate Professor in Nursing at the Department of Nursing, Umeå University, Sweden. Currently, she has an appointment as Head of the Department of Nursing. She teaches in several of the department’s programs, preferably on psychiatric nursing but also on qualitative methods. Her research interests are self-harming behaviour, mental ill-health, recovery and psychiatric nursing in various contexts.

Jenny Molin

Jenny Molin is a mental health nurse and Senior Lecturer at the Department of Nursing, Umeå University, Sweden. She teaches at the advanced level of mental health nursing education and also has a clinical employment in acute psychiatric inpatient care. Her research interests are mental ill-health, recovery, psychiatric nursing in various contexts and nursing interventions in psychiatric inpatient care.

Silje Gustafsson

Silje Gustafsson is a district nurse and Assistant Professor at Luleå University of Technology. Her research areas are primarily self-care and telephone nursing. During her doctoral studies, she received The Norrbotten Academy’s Health Science Prize 2014 for her efforts to improve and develop telephone nursing. After receiving her doctorate, she entered a position as a postdoc at Karolinska Institute. In collaboration with the national telephone helpline 1177 and researchers at KI and the University of Skövde, work is underway to strengthen the quality and scientific basis for the advice given at 1177. In 2016, Silje was invited as a keynote speaker at the Pharmaceutical Congress, where she also participated in a debate panel on self-care counselling in a pharmacy context. Furthermore, she has contributed to the start-up of a national network for research in telephone nursing, and has on several occasions presented her research at both national and international conferences. She is a chapter author for two peer-reviewed chapters in educational literature and has published 17 scientific articles in eleven peer-reviewed scientific journals. Silje is a supervisor for two doctoral students, and is responsible for a course at the doctoral level in research ethics

References

- Bjerkvik, L. K., & Hilli, Y. (2019). Reflective writing in undergraduate clinical nursing education: A literature review. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.11.013

- Buus, N., & Gonge, H. (2009). Empirical studies of clinical supervision in psychiatric nursing: A systematic literature review and methodological critique. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 18(4), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00612.x

- Choperena, A., Oroviogoicoechea, C., Zaragoza Salcedo, A., Olza Moreno, I., & Jones, D. (2019). Nursing narratives and reflective practice: A theoretical review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(8), 1637–1647. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13955

- Contreras, J. A., Edwards‐Maddox, S., Hall, A., & Lee, M. A. (2020). Effects of reflective practice on baccalaureate nursing students’ stress, anxiety and competency: An integrative review. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 17(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12438

- Cutcliffe, J. R., Sloan, G., & Bashaw, M. (2018). A systematic review of clinical supervision evaluation studies in nursing. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1344–1363. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12443

- Dawber, C. (2013). Reflective practice groups for nurses: A consultation liaison psychiatry nursing initiative: Part 2 – The evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00841.x

- Dawber, C., & O’Brien, T. (2014). A longitudinal, comparative evaluation of reflective practice groups for nurses working in intensive care and oncology. Journal of Nursing & Care, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1168.1000138

- Fragkos, K. C. (2016). Reflective practice in healthcare education: An umbrella review. Education Sciences, 6(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030027

- Ghaye, T., & Lillyman, S. (2010). Reflection: Principles and practice for healthcare professionals. Quay Books.

- Goulet, M. H., Larue, C., & Alderson, M. (2016). Reflective practice: A comparative dimensional analysis of the concept in nursing and education studies. Nursing Forum, 51(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12129

- Gustafsson, S., Engström, Å., Lindgren, B. M., & Gabrielsson, S. (2021). Reflective capacity in nurses in specialist education: Swedish translation and psychometric evaluation of the reflective capacity scale of the reflective practice questionnaire. Nursing Open 8(2), 546–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.659

- Happell, B., & Gaskin, C. J. (2013). The attitudes of undergraduate nursing students towards mental health nursing: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(1–2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12022

- Hoover, J., Koon, A. D., Rosser, E. N., & Rao, K. D. (2020). Mentoring the working nurse: A scoping review. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00491-x

- Howard, V., & Eddy‐Imishue, G. E. K. (2020). Factors influencing adequate and effective clinical supervision for inpatient mental health nurses’ personal and professional development: An integrative review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12604

- Hughes, L. J., Mitchell, M., & Johnston, A. N. (2016). ‘Failure to fail’ in nursing–A catch phrase or a real issue? A systematic integrative literature review. Nurse Education in Practice, 20, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.06.009

- Kennedy, B., Curtis, K., & Waters, D. (2014). Is there a relationship between personality and choice of nursing specialty: An integrative literature review. BMC Nursing, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-014-0040-z

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educators’ guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(4), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000669

- Lakeman, R. (2020). Advanced empathy: A key to supporting people experiencing psychosis or other extreme states. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 8(1). https://pacja.org.au/2019/11/advanced-empathy-a-key-to-supporting-people-experiencing-psychosis-or-other-extreme-states-2/

- Levett-Jones, T., Cant, R., & Lapkin, S. (2019). A systematic review of the effectiveness of empathy education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 75, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.01.006

- Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(4), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2

- Newton, J. M., & Butler, A. E. (2019). Facilitating students’ reflections on community practice: A new approach. In S. Billett, J. Newton, G. Rogers, & C. Noble (Eds.), Using post-practicum interventions to augment healthcare students’ clinical learning experiences (pp. 235–258). Springer.

- O’Neill, L., Johnson, J., & Mandela, R. (2019). Reflective practice groups: Are they useful for liaison psychiatry nurses working within the emergency department? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.003

- Ottenberg, A. L., Pasalic, D., Bui, G. T., & Pawlina, W. (2016). An analysis of reflective writing early in the medical curriculum: The relationship between reflective capacity and academic achievement. Medical Teacher, 38(7), 724–729. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1112890

- Priddis, L., & Rogers, S. L. (2018). Development of the reflective practice questionnaire: Preliminary findings. Reflective Practice, 19(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1379384

- Rogers, S. L., Priddis, L. E., Michels, N., Tieman, M., & Van Winkle, L. J. (2019). Applications of the reflective practice questionnaire in medical education. BMC Medical Education, 19(47), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1481-6

- Scanlan, J. M., & Chernomas, W. M. (2016). Failing clinical practice & the unsafe student: A new perspective. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 13(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102748

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey-Bass.

- von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2008). STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

- Walsh, P., Owen, P. A., Mustafa, N., & Beech, R. (2020). Learning and teaching approaches promoting resilience in student nurses: An integrated review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 45, 102748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102748

- Younas, A., & Maddigan, J. (2019). Proposing a policy framework for nursing education for fostering compassion in nursing students: A critical review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(8), 1621–1636. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13946