ABSTRACT

The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights calls for accessible higher education (HE), stating that it is necessary for the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity. Within this context, our research is centred on the Aristotelian principles of equity and fairness. To achieve these outcomes, our completed, Stage One research (2008–2019, 5603 participants), took place inside the university context and focused on designing out identified barriers to access and participation in mandatory assessment tasks for all students, including those with a disability. Building on our Stage One learnings and to generate increased inclusion, Stage Two involved the development of authentic HE assessment tasks which generate external, reflective, and inclusive practitioners who value shared social membership. This research seeks to support and strengthen the core philosophy of HE and the guiding principles of the participating university, Queensland University of Technology, which state: ‘ … the real world asks us … to guide it towards collective benefit.’ To achieve these outcomes, this university ‘ … partners with students to develop their self-knowledge, professional integrity and ethical leadership to enable them to become … global citizens who create positive social change’. This Stage Two research has been facilitated by the unique, author created integration of the Teaching and Assessing of Reflective Learning Model and the Experiential Learning Model (TARLEM). TARLEM focuses simultaneously on developing discipline-based content, the mastery of reflective practice skills, and an understanding of the reason for the task in terms of the social impacts of international business decision-making. The cross-cultural, cross-discipline and online/on campus participants are enrolled students in a UG IBU degree (622 responses).e

1. Introduction

1.1. Foundations of accessible education and prior research learnings

The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights calls for accessible higher education (HE), stating that it is necessary for the ‘full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity’ (United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, Citation1976). Within this context and centred on the Aristotelian principles of equity and fairness (Barnes, Citation1995), our Stage One research took place inside the Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, over a 12-year period with 5603 HE Business students participating (Taylor et al., Citation2021)Footnote1.

While Goal 2 of the Australian Government’s National Strategy for International Education 2025 document (2016, pp. 13–14) is to deliver the best possible student experience and consistent with prior research including Jackson and Oguro (Citation2018), our Stage One research involving a series of face-to-face interventions confirmed that there are significant challenges to the achievement of these goals for all universities. At the heart of these challenges was significant levels of hostilities within the student cohort across cultures and disciplines, particularly when these students were expected to engage in mandatory teamwork-based assessment tasks.

In terms of positive research outcomes, our intervention learnings indicated that diversity issues can be resolved through the application of carefully scaffolded reflective support and the introduction of cultural competency and reflective practices-based specialist-led, support workshops for all students prior to the commencement of mandatory team-work tasks. With this scaffolded support in place, our interventions (2008–2019) successfully designed out the barriers to student access and participation (Graham et al., Citation2018) within summative assessment tasks. These remodelled, mandatory, assessment tasks, in turn, ‘ … operated as a technology of inclusion, where all students had the opportunity to learn and to demonstrate what they have learned (Graham et al., Citation2018, p. 104; Graham, Citation2024)’.

In focusing on the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of tertiary education and student learning, a sustainable and potentially ‘exportable’ resource for supporting, influencing, motivating, and inspiring heterogenous student cohorts and their teaching teams to learn together was created and widely disseminated nationally and internationally (Taylor et al., Citation2017, Citation2021, Citation2023; University of Oxford, Citation2017).

1.2. Bringing about an empathetic change in society by the fostering of external graduate professional practice skills

Of importance to note is that these successful, inclusion outcomes from our Stage One Project were limited to students working within the university and within their team-based assessments. In contrast, our current, Stage Two research, while continuing to be centred on the Aristotelian principles of equity and fairness, foregrounds, firstly, the guiding principles put forward by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) within which the research was conducted. These principles seek to honour the overall role that HE is expected to fulfill generally which is based on: ‘ … the real world asks us … to guide it towards collective benefit … across the nation and around the world.’. To achieve these outcomes QUT ‘ … educates, inspires and partners with students to develop their self-knowledge, professional integrity and ethical leadership to enable them to become truly global citizens who create positive social change’ [Queensland University of Technology (Citation2023), p. 2 and 10].

Second, our Stage Two research also seeks to prioritise the authentic-assessment – based research disseminated by Jan McArthur in her Higher Education 2022 article ‘Rethinking authentic assessment: work, wellbeing, and society’. That is, our current research has been designed to assist all students to develop their graduate professional practice skills within the external business world. To achieve this outcome, our research design rethinks the concept of the UG mandatory, individual, major project, and final exam assessment tasks within an International Business Unit (IBU) offered by QUT, one of Australia’s largest universities.

In focusing on experiential teaching and learning (D. A. Kolb’s, Citation1981, Citation1984), understanding emotional intelligence (Cook et al., Citation2011) and the overall concept of empathy (Demetriou & Nicholl, Citation2022), our Accounting/Business-based project seeks to contribute to the earlier research in this area. Of note, these concepts have been found to be of critical importance for the creation of a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Knapp, Citation2010) in the fields of Medicine/Health Care professionals (Peisachovich et al., Citation2023), Post-Graduate Engineering students (Thorpe, Citation2016) and Business Communications practitioners (Fuller et al., Citation2021).

These cross-disciplinary articles have a common basis of highlighting the importance of social-emotional competence for educators, which is commonly held to be an important prerequisite for the quality of teacher–student interactions and student outcomes (Aldrup et al., Citation2022). As highlighted by Demetriou and Nicholl (Citation2022, p. 5), ‘thinking about the potential of social and emotional skills for education is not new. Back in 1933, John Dewey (1933, p. 189) wrote of the necessity to address students’ social and emotional skills in education: ‘There is no education when ideas and knowledge are not translated into emotion, interest, and volition’.

Thus, in summary, the key objective of these authentic assessments is to focus student attention not only on the attainment of discipline-based knowledge and successful teamwork strategies across cultures/disciplines (the focus of Stage One of our research) but to also ensure that our students see the importance of utilising their content knowledge to bring about an empathetic change in society (McArthur, Citation2022). For example, in the mandatory, major, student project, and adopting a real-world case-study scenario, the IBU students were required to work closely with their Superannuation Fund clients, who have a long-term, environmental protection investment focus, to recommend an appropriate industry and nation-based, investment option.

This integration of empathy and authentic tasks to assist with the generation of real-world professional skills is also consistent with the requirements for degrees if they wish to be accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) International. Founded in 1916, making it the longest serving global accrediting body for business schools globally, an AACSB accreditation marks a Business school with a standard of excellence that is highly sought after. At the heart of the AACSB approach to learning is that it requires authentic contexts which can provide opportunities for knowledge and skill acquisition. ‘

…In the field of education, situated learning challenges us to see learning not just in insulated classrooms, but in real-world experiences. This enables us to create dynamic, complex, social, diverse, and global learning environments both inside and outside of our university walls’ (Visco and Murrell, Citation2022).

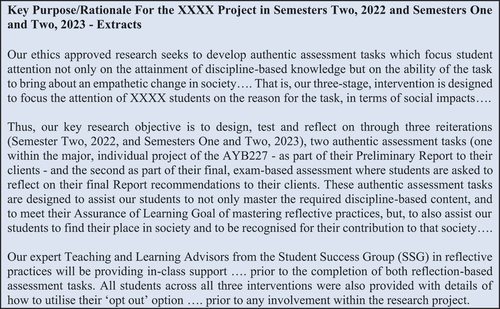

1.3. An ethics-approved, opt-out research methodology provides a unique data set

With a focus on strengthening inclusion opportunities to include the fostering of external graduate professional practice skills, it was critically important that as many students as possibly participated in our research interventions. Thus, the methodology adopted for our research included a reiterative, targeted intervention (Semester Two, 2022 and Semesters One and Two 2023) which involved 622 reflection-based, mandatory, assessment task responses from 311 participants (two per student). The learnings identified in this research, as highlighted in Section 7.2., will then be utilised within the Semesters One and Two, 2024 research interventions.

Given the overall issue of a lack of student engagement across the HE sector,Footnote2 the primary, ethics-approved, authentic-task-based assessment tasks testing instrument consisted of an ‘opt out’ of the research option for all students. Working in conjunction with the University-based Ethics Review Committee, the research was conducted in a non-threatening manner with the support of the university’s independent Student Success Group (SSG). The independent security provided by the SSG of all the opt-out information for all three semesters, satisfied all of the relevant ‘opt-out’ conditions stated under the Australian Government’s National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2023, Chapter 2.3.6 Qualifying or Waiving Conditions For Consent. All ‘opt-out’ emails were also retained in confidence by the SSG until after all final unit results had been processed and published to students. SSG is totally independent of both the teaching team and the research team for the project.

The continued presence of the SSG-based, independent, teaching, and learning advisors within the classrooms for the participating students created a psychologically safe environment (Edmondson, Citation2004) for all students within which they were fully informed of all aspects of the research project (as detailed in Sections 5.1 and 5.2) and how to adopt their preferred participation option simply and anonymously. Of most interest to the students was becoming involved in authentic/real life projects (international profit shifting/use of tax havens and potential auditing collusion issues by global corporations and the related impacts on both developed and developing nations) which would assist them to develop both empathy and professional practice skills.

Given this significant level of protection and the high level of interest in the project itself, it was not surprising that no student in any of the three intervention periods sought to ‘opt-out’ of the research. Also, of importance for the relevance of our Stage Two research findings for other universities and contexts, the student participants are cross-cultural and cross-discipline and include online and on-campus student attendance modes.

1.4. Authentic assessment task design strategy

Sustainable development for global corporations is of significant interest in the media and in terms of student feedback and in-class questions. In turn, an example of one of the authentic assessment tasks provided to students across the three interventions (2022/2023) was included as part of their major, individual project (Mandatory Authentic Assessment Task One).

Within this context and utilising a range of resources provided such as the Environmental Protection Index (Wolf et al., Citation2022), students were assisted to reflect on selecting investment options in nations rating highly within this index and within industries that met the United Nations Development Goals (Citation2015). Students were then encouraged to reflect on the potential for using their professional skills to promote investment options which can reduce the widespread flooding and loss of homes and communities that a range of nations have faced including Australia, the United Kingdom, and the European Union (Climate Council of Australia Ltd, Citation2022; The Times, London, United Kingdom, December; Citation2022; European Environment Agency, Citation2023).

Thus, at the heart of our Stage Two, authentic assessment tasks is the need to foreground the reason for the task, in terms of social impacts, and to ensure that each student sees themselves ‘not as an isolated individual but as part of a wider society’ (McArthur, Citation2022). Within their formal assessment tasks, students were therefore expected to be able to understand both the relevant content issues and were asked to reflect on the social impacts of international business practices and the ability to work with their clients to foreground a sustainability agenda.

In addition to sustainability-based tasks, Mandatory, Assessment Task Two included, within the invigilated, final exam, a second authentic task based on alternating case scenarios (for example, different case scenarios were utilised across the final and deferred exams) was also developed within the key International Business content areas of International Taxation (profit shifting/use of tax havens) and International Auditing (collusion between the external auditors and the corporate directors) and the social impacts created. For example, audit firms can, at times, fail to use adequate professional judgement in gaining a genuine understanding of a company’s financial position such as in the UK company case of Carillion Ltd. The Carillion collapse then resulted in major building project shutdowns, more than 3,000 redundancies, significant financial losses to suppliers and lenders and cost UK taxpayers more than £180 m (National Audit Office/UK House of Commons Citation2018; UK Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee/UK Parliament, Citation2018).

2. Creation of a unique integrated experiential/Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning Model (TARLEM)

2.1. Enriching D. A. Kolb’s (Citation1981,Citation1984, Citation2005) experiential learning model

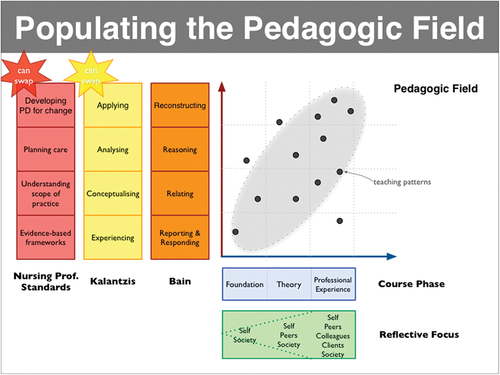

As detailed in Section Four, the two authentic assessment tasks generated within the Stage Two research were embedded with an integrated Experiential/Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning Model (TARLEM) as set out in (TARL Model) and 4.1 (TARLEM). This author created integrated model and applied for the first time to our knowledge, seeks to transition UG students from a ‘self’ and ‘peers’ (team members) focus to becoming external, reflective, and inclusive practitioners who value shared social membership.

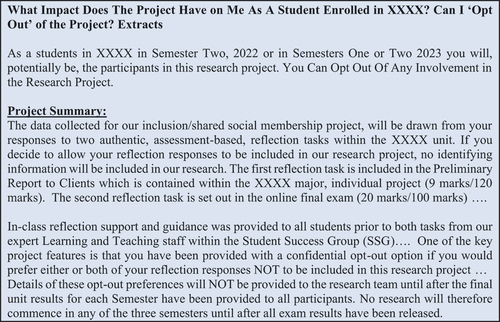

Figure 1. The TARL model – Taylor et al. (Citation2021): applying adapted levels from Bain et al. (Citation2002) – reflective focus on external, professional practice, clients and society within ‘real’ experiences.

Integrating the TARL Model, with its reflective focus on professional practice and ‘real’ tasks as delineated in , into Kolb’s experiential learning model also ensures that our students meet the University’s Assurance of Learning Goal (AOLG) for graduating students in terms of mastering reflective practices within real world/authentic scenarios. These AOLGs are an important aspect of obtaining and retaining membership for all Business Schools globally within the (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business AACSB, Citation2020).

The critical importance of Kolb’s experiential learning model (ELM) (Citation1984) for this research, as elaborated in Section Four, is the model’s inherent understanding that students need to cycle through four stages for learning to be effective and they can enter at any stage within the cycle. These four stages include having a concrete experience (CE) followed by observation of, and reflection on, that experience (RO). This leads to the formation of abstract concepts (AC) and generalisations (or conclusions), which are then used to test hypothesis in future situations, resulting in new experiences (AE) (Gibbs, Citation1992; D. A. Kolb, Citation1981, Citation1984).

Of importance, for our Stage Two research, the model makes explicit the importance of encouraging students to reflect and for teaching staff to provide students with feedback to reinforce their learning. To achieve these desired learning outcomes and, again, as detailed in and , a foundation stone of our three-stage intervention is that students and staff (including the Senior Tutors teaching within the IBU) needed to be taught how to reflect in deep, critical, and transformative ways to engender sustainable, life-long, learning practices (Mezirow, Citation2006; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013).

Figure 2. Transitioning from prioritising the self and peers as learners to a reflective focus on professional practice, clients and society. Inclusion within the TARLE model – (D. A. Kolb, Citation1984; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013; Taylor et al., Citation2021; Van Akkeren & Tarr, Citation2022).

2.2. Foundations of genuine inclusion

Reflection at a broad level can have multiple purposes and therefore has been acknowledged as being difficult to define. Reflection for learning has been variously explicated and applied in educational settings (see Boud, Citation1999; Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013), but at the broad level, we suggest that the most generative definition for both domestic and international students’ learning in higher education includes two key elements 1) making sense of experience in relation to self, others, and contextual conditions; and importantly, 2) reimagining and/or planning future experience for personal, professional, and social benefit (Taylor et al., Citation2021).

Of particular relevance to the achievement of effective reflection for our Stage Two research then is that this definition demands that students engage in reflection that accounts for a rigorous examination of their beliefs and practices in relation to community, culture, and professional futures. These issues are outlined in detail in Section Four.

2.3. Article aims and methodology

Within the context of the Aristotelian principles of equity and fairness (Barnes, Citation1995) and consistent with the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights which calls for accessible higher education (HE) (United Nations [UN], Citation1976)’, our Stage One and completed research objective (2008–2019 with 5603 participants) took place inside the university context (Taylor et al., Citation2021). This research focused on the designing out of identified barriers to access and participation in mandatory, team-based, assessment tasks for all students, including those with a disability (Graham et al., Citation2018).

Building on our Stage One learnings and to generate increased inclusion levels, this article’s key objective is to elaborate on our Stage Two research which focuses on the development of authentic HE assessment tasks. At the heart of these tasks is the objective of providing our UG IB students with the opportunity to develop external, graduate professional practice skills. These skills are designed to facilitate our business/professional-based students to apply empathy/inclusion in their professional practices which will allow them to both find their own place in society and to foster shared social membership (McArthur, Citation2022). For example, utilising real-world case scenarios related to sustainable business practices, students needed to be provided with opportunities to reflect on how a focus on investment options in developed nations recommended to their superannuation fund clients may act to marginalise developing nations.

A foundation stone of the Stage Two research was that students and staff needed to be taught how to reflect in deep, critical, and transformative ways to engender sustainable, life-long, learning practices (Mezirow, Citation2006; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013; Taylor et al., Citation2021). Drawing on the reflective practice literature and learning theories, a new, transferable, and customisable model for teaching and assessing reflective learning (TARL) in all HE courses was conceptualised by the authors (Taylor et al., Citation2021). This model seeks to develop student capacities which will lead to an enhancement of their learning and their professional practice and was embedded into the participating UG IBU by the intervention team experts in international business/cultural competency/curriculum/assessment design/reflective learning.

This TARL model was then integrated with D. A. Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning model to generate the TARLEM as previously elaborated (Taylor et al., Citation2021). Within this framework, this research therefore focuses on simultaneously developing: discipline-based content; the mastery of reflective practice skills; and an understanding of the reason for the task in terms of the social impacts of international business decision-making (McArthur, Citation2022).

Given our primary objective of strengthening inclusion opportunities for all students by fostering external graduate professional practice skills, it was critically important that as many students as possible participated in our research interventions. Thus, the methodology adopted for our research included a reiterative (2022/23), targeted intervention which involved 622 reflection-based, mandatory, assessment task responses from 311 participants (two per student).

In turn, the primary, ethics-approved, authentic assessment task testing instrument consisted of an ‘opt out’ of the research option for all students. The regular, in-class, presence of the Student Support Group-based, independent, Teaching, and Learning advisors, created a psychologically safe environment (Edmondson, Citation2004) for all students to freely adopt the participation option they preferred.

Given that no student opted out of the research, the data included in our research represent the reflections of all enrolled students in the IB unit across three iterations who completed the mandatory assessment tasks. The research assistant employed within the project, funded by a university-based teaching and learning grant, and then independently processed all of the authentic task responses.

3. Transformative learning

3.1. TARL model

Within large classes, a ‘rich, learning environment’ can be achieved for both students and staff through the creation of a welcoming sense of community: ‘ … which requires a strong bond of communal competence along with a deep respect for the particularity of experience. When these conditions are in place, communities of practice are a privileged locus for the creation of knowledge (Snepvangers & O’Rourke, Citation2020; Florian & Linklater, Citation2010; Wenger, Citation1998, p. 214)’.

To provide this ‘rich, learning environment’ which would facilitate the necessary level of personal examination and reflection by HE students for which we argued earlier, we utilised the teaching and assessing reflective learning (TARL) model (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013) which introduces the concept of the pedagogic field. This field can best be imagined as a two-dimensional space where categories (or levels) of reflection are set against the development stages students experience across a course/unit.

highlights the pedagogic field with these dimensions. The dots represent specific teaching episodes or teaching patterns that are relevant for students at a particular stage in their course and that target a specific level (and sometimes a range) of reflection. Of critical importance to our Stage Two research is the ability of the TARL model to assist students to develop an external focus on building their professional, client-based skills and to reflect on what role they would like to play in society utilising the ‘teaching episodes’ of ‘real’, authentic assessment tasks.

Again, referring to , the development-based dimension (horizontal axis) highlights the varied demands on teaching as students’ progress through a program/course of study or act within different contexts including in terms of professional practice. In contrast, the category-based dimension (vertical axis) in captures the progression from rudimentary reflective thinking to more sophisticated thinking such as that set out in the 4Rs Model of Reflective Thinking elaborated by Bain et al. (Citation2002) and as elaborated in .

Table 1. Reflective support table provided to assist students to identify and analyse and then operationalise the client feedback received.

3.2. Developing a reflective focus on professional practice, clients and society

As was the case for our Stage One research which focused on ‘self’ and ‘peers’ within team-based assessment tasks, for our Stage Two research, the TARL model generated a critical, intervention team breakthrough. The individual major project, final exam, mandatory assessment tasks expected the students to move from a focus on the self and peers as learners to a reflective focus on professional practice, clients, and society (as per the purple- and green-bounded indicators in the development-based, horizontal axis in the TARL model outlined in ).

To achieve this transformation, and as further detailed in Section 4:

students needed explicit support/scaffolding in terms of the provision of ‘real’, authentic assessment tasks which were client-based. In Authentic-Task One, students were required to write a summary, preliminary, investment recommendation report to their clients (Part A of the mandatory, Major Individual Project task). Support processes included students being provided with annotated examples of effective/ineffective reports/advice to clients and a complete sample report which utilised reflective prompts that related to the marking criteria. Students were also provided with a two-hour Q & A support workshop – on campus and recorded – where the UC (the Chief Investigator within the research team) and senior tutors (and project markers) responded to all queries. A very active Discussion Board (DB) was also provided with a specific DB heading for the Major, Individual Project, Preliminary Report queries.

as is the case with IB practitioners, students also needed initial support in terms of how to address the feedback received from their clients. This type of support included teaching students how to weigh up the feedback received, including the strengths and weaknesses identified, what information/resources would be needed to respond to the client feedback provided, and how to justify a plan of action.

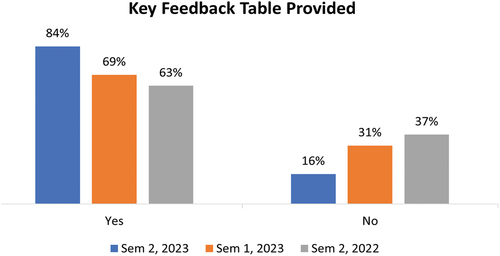

A summary Feedback table, as highlighted in , was provided for all students as identified below and 63–84% of students (2022–2023) utilised this table to assist them in analysing the client-based feedback received. Examples of the student use of this table are provided in and examples of how to complete these tables were also provided to students; and

(3) For Assessment Task Two, a mandatory, final exam, reflection-based question (for example, a case study from the International Taxation content related to profit shifting/use of tax havens and the negative impacts on both developed and developing nations), a reflection-based support workshop was provided to students – on campus and recorded. This workshop utilised a practice case study which assisted students to identify the relevant social impacts of international business activities related to alternating cases focusing on International Taxation (IT) or International Auditing (IA) activities.

Table 2. Example one – student completed, reflective support table – mandatory major individual project submission.

Table 3. Example two.

To ensure exam integrity, the primary, final exam completed by the majority of students,students would contain an IT case study scenario and questions. In contrast, the deferred/supplementary exam question would then adopt an alternate IA case scenario. An example of the support materials/readings provided for this final exam question on International Taxation is provided in .

Table 4. International taxation – example support resources provided – final exam.

Within this workshop, specialist staff from the university’s, independent, Student Success Group (SSG), assisted students to develop the specialist skills needed to utilise the Four Rs of Reflection as developed by Bain et al. (Citation2002) and as set out below in . The use of this 4 Rs Model of Reflection was then expected as part of the final exam reflection question responses.

Table 5. Using the four Rs of reflection to foster professional practice skills and social empathy - Bain et al. (Citation2002).

4. Inclusion within an integrated experiential/Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning Model (TARLEM)

4.1. Enriching D. A. Kolb’s (Citation1981, Citation1984) experiential learning model

In addition to the social impacts’ focus of international business decision-making and to master the relevant technical content, the authentic assessment tasks were specifically generated with an integrated Experiential/Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning Model as set out in . This integrated model was created by the authors to assist our students in transitioning to a reflective practitioner focus. Utilising this TARLE model also ensures that our students meet the University’s Assurance of Learning Goal (AOLG) for graduating students in terms of mastering reflective practices. These AOLGs are an important aspect of obtaining and retaining membership as a Business School within the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, Citation2020).

Kolb’s experiential learning model (Citation1981; Citation1984) is based on the understanding that all students need to cycle through all four stages for learning to be effective and they can enter at any stage within the cycle. These four stages include having a concrete experience (CE) followed by observation of, and reflection on, that experience (RO). This leads to the formation of abstract concepts (AC) and generalisations (or conclusions), which are then used to test hypothesis in future situations, resulting in new experiences (AE) (Gibbs, Citation1992; D. A. Kolb, Citation1984).

As highlighted by Van Akkeren and Tarr (Citation2022), at the heart of this four-stage approach is that, as Kolb suggests, different people naturally prefer a certain learning style with factors influencing what that style may entail. This may include, for example, the social environment, educational experiences, and/or the cognitive abilities of the individual. Referred to as active learning, independent learning, learning by doing, work-based learning, and/or problem-based learning (Healey & Jenkins, Citation2000), this approach is seen as particularly relevant to higher education (Fleming et al., Citation2008).

Of importance, for our Stage Two research, the model makes explicit the importance of encouraging students to reflect and for teaching staff to provide students with feedback to reinforce their learning. To achieve these desired learning outcomes and, again, as detailed in , a foundation stone of our Stage Two, three-stage intervention is that students and staff needed to be taught how to reflect in deep, critical, and transformative ways to engender sustainable, life-long, learning practices (Mezirow, Citation2006; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013).

4.2. The dangers associated with reflection expectations without scaffolding

While a critical aspect of Kolb’s experiential learning model (ELM) is Stage Two – Reflective Observation – reflecting on/reviewing the experiences, the success of Kolb’s ELM relies heavily on individual academics to create a suitable reflective process for student participants (Morris, Citation2019). The issue then becomes that while the value of reflective learning is widely accepted in educational circles as a means of improving students’ lifelong learning and professional practice in HE (Rodgers, Citation2002; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013), reflection is difficult to do well and is often not taught in any explicit way (Rodgers, Citation2002; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013). For example, there is evidence to suggest that reflective writing by HE cohorts tends to be superficial unless it is approached in a consistent and systematic way (Orland-Barak, Citation2005). Bain et al. (Citation2002) argue that deep reflective skills can be taught, however they require development and practice over time.

4.3. The foundations of genuine inclusion

Reflection at a broad level can have multiple purposes and therefore has been acknowledged as being difficult to define. Reflection for learning has been variously explicated and applied in educational settings (see Boud, Citation1999; Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013), but at the broad level, we suggest that the most generative definition for both domestic and international students’ learning in higher education includes two key elements which are at the heart of our, profession-based, Stage Two research 1) making sense of experience in relation to self, others, and contextual conditions; and importantly, 2) reimagining and/or planning future experience for personal, professional, and social benefit (Taylor et al., Citation2021). Of particular relevance to the achievement of effective reflection for our Stage Two research then is that this definition demands that students engage in reflection that accounts for a rigorous examination of their beliefs and practices in relation to community, culture, and professional futures.

Reflection may be expressed differently depending on people’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds, as prior experience impacts on the ways in which we understand and deliberate about how and why we do things (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2013). Additionally, many scholars and practitioners have emphasised the important role reflection, and in particular self-reflection, plays for international and cross-cultural work and understanding (Furman et al., Citation2008; Taylor et al., Citation2015).

As briefly summarised in Section 2.4., while the importance of reflection is widely recognised (Taylor et al., Citation2021), a key issue is that reflection is commonly embedded into assessment requirements in HE subjects, without the necessary scaffolding or setting out of clear expectations for students. Within this context, reflection expectations can represent a barrier to learning. These inclusion barriers can then be intensified for students within any practical, authentic/experiential assessment task which seeks to transition the student ‘self’ and ‘peers’ toward professional practice and social empathy unless the necessary support processes are provided.

As highlighted in Section 3 and drawing on the reflective practice literature and learning theories, a new, transferable, and customisable model for teaching and assessing reflective learning (TARL) in all HE courses has been conceptualised (Taylor et al., Citation2021). For this Stage Two research, this TARL model has been incorporated into the Reflective Observation (RO) stage of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model to further develop student-based, reflective capacities.

In turn, students will be able to respond more confidently to the two, mandatory, reflection-based, authentic tasks included in our research project. To support this development in reflective practice skills for IB students participating, our expert Teaching and Learning Advisors in reflective practice from the University’s Student Success Group (SSG) provided in-class support to all our IB students prior to the completion of both reflection-based, authentic, and assessment tasks.

Students were also able to access a support recording prepared by the SSG experts on reflection, which included step-by-step explanations, for example, of the Four Rs of Reflection (Bain et al., Citation2002) and how to apply them. These issues, the embedding process associated with the TARLE Model and the overall results achieved will be elaborated in Section 5.

5. Embedding the integrated TARLE model into mandatory assessment tasks

5.1. Building psychological safety to support the ‘opt-out’ research methodology

Throughout Semester Two, 2022, and Semesters One and Two, 2023, all enrolled students who attempted mandatory assessment tasks in the UG IBU participated in inclusion interventions. As detailed in Sections Three and Four, all students were provided with support reflective practice workshops conducted by the independent, university-based Student Success Group (SSG) across the three intervention semesters in 2022/23. Active engagement by students in the workshop was encouraged with an initial overview of the 4Rs reflection process provided, including in-class concrete examples as detailed in (Bain et al., Citation2002; Taylor et al., Citation2015, Citation2021).

These workshops were provided prior to these students being required to complete the mandatory, authentic tasks which were contained in the major, individual project and the final exam. In turn, 622 responses were obtained from cross-cultural, cross-discipline and across both on-campus and online enrolled students.

As summarised in Section 1.4, given the ethically approved opt-out methodology adopted within the research conducted in a psychologically safe environment, no student made the decision to opt out of allowing the research team to utilise their assessment task responses for our research. Thus, all enrolled students within the three interventions who completed these mandatory tasks are included in this study.

It was also critically important that all of the students across the three iterations were able to engage regularly with the independent SSG experts in advance of being required to complete the two mandatory assessment tasks in order to build a psychologically ‘safe’ environment (Edmondson, Citation1999, Citation200). This was the case given, and as previously detailed in Section 1.4, that the ‘opt-out’ research methodology adopted required any student who wished NOT to be involved in the research project, to confidentially advise the SSG of their wish to opt out of research participation.

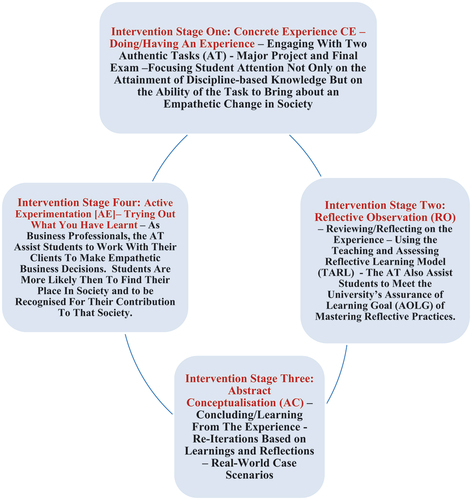

5.2. Ethics approval – disclosure requirements

As required by the ethics clearance obtained for the Stage Two research, details of the project, the project team, and the key purpose/rationale for the project had to be provided to all students on the IBU Canvas site prior to any student involvement with the authentic assessment task activities. In addition, students were required to be notified via Discussion Board, an Announcement and as part of the class lectures as to the location of the project details. For example, and as extracted below in , our primary research rationale was provided on the IBU site for each of the three interventions in advance of any research being undertaken.

Figure 3. Key purpose/rationale – on-line and In-class dissemination to students - ethics approval pre-requisite requirement.

An additional ethics clearance requirement related to the dissemination of details related to the project’s impact on each student and to highlight the process for ‘opting out’ of the project if this was desired. The relevant advice to all students in relation to these issues and provided again prior to any student involvement in the authentic, assessment tasks is summarised in .

5.3. Generalised value of research learnings across units, faculties, and universities

In terms of selecting a unit within which to embed our, author created, TARLEM, an IBU was selected which meant that the data collected across the three iterations related to cross-cultural and cross-discipline students from a wide range of countries. The student responses also included students enrolled both online and on-campus, and given the ethics-approved, ‘opt-out’ methodology in place, these responses were obtained from all of the students who were enrolled in the IBU across 2022/2023 who completed the mandatory assessment tasks.

The student responses received for mandatory, authentic task one, related to the mandatory, major individual project question where students were required to analyse the client feedback from their ‘real world’ clients on the Preliminary Report provided by the students. Within this authentic task, the clients identified to the students (their investment consultants) that they had a sustainability priority for future global investments. Section 3 and and evidence the success of the authentic tasks utilised. The individual, student-based, examples provided below also indicate the success of the TARLE model in supporting the transitioning of a UG student focus from the ‘self’ and ‘peers’ to a reflective practitioner and social empathy perspective as discussed in detail in Sections 3 and 4.

For example, the two students’ responses extracted below from within the Semester Two, 2023 cohort, highlight a clear understanding of the need to successfully align client-based objectives with the related environmental impacts of business decision-making, in their industry selection. This authentic assessment task was successful in generating a ‘real’ context for UG students where they were supported in their transitioning to external, reflective, and inclusive practitioners who value shared social membership.

… it is recommended to invest in automotive/car manufacturing industry with the highest growth rate over 2022–2027 in the UK, Germany, and Japan respectively, which met AUS$900 million investment requirement. In addition, the automotive/car manufacturing industry is actively promoting green transition to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Electric vehicles are expected to stimulate the automotive market’s supply and demand as coping with climate change. Carbon dioxide emissions are the main cause of global warming. Thus, the global automotive/car manufacturing industry transferring of manufacturing electric vehicle market is showing exponential growth. [Student One]

… … Based on the key criteria outlined by State Superannuation Fund (SSSF), it was determined in the preliminary report that the fund considers allocating their capital to make an AUS$900 million investment in the automotive industry in the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan. The three selected countries met the criteria of having mostly adopted IFRS and being within the 25 most sought-after investment nations as listed in the 2023 AT Kearney Confidence Index Report and are within the top 40 nations listed on the 2022 Environmental Performance Index. The selected countries are therefore following and implementing environmentally conscious policies and are seen as a desirable investment location by large global business leaders. [Student Two]

Key strengths and weaknesses of each country are outlined in Appendix 6. It was determined that an investment be made in the automotive industry as it is perfectly positioned to benefit from the global push for sustainability and is strongly backed by government incentives and subsidises. Companies focusing on this industry within the target countries are focusing all their attention to building sustainable cars using the most sustainable practices. The positioning of companies in these national sectors are government supported, and therefore the risk of investment is heavily reduced. [Student Two – cont’d]

By integrating the TARL Model, with its reflective focus on professional practice and ‘real’ tasks as delineated in , into Kolb’s experiential learning model which, at its heart, prioritises, concrete examples such as authentic tasks, also ensures that our students meet the University’s Assurance of Learning Goal (AOLG) for graduating students in terms of mastering reflective practices within real world/authentic scenarios. These AOLGs are an important aspect of obtaining and retaining membership for all Business Schools within the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB, Citation2020).

6. Results

6.1. Mandatory assessment task one

Mandatory Assessment Task One required students, within their Major, Individual Project, to provide a preliminary report to clients related to suggested nation and industry-based investment options for a real-world client with a stated sustainability context. This authentic assessment task, embedded into the IBU across three semesters, was uniquely generated within the Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning and Experiential Learning model (TARLEM) which the author created as elaborated in Section 3.

A core feature of Mandatory Assessment Task One is the objective of assisting students to move from a focus on the ‘self’ and ‘peers’ as learners to a reflective focus on professional practice, clients, and society as detailed in Section 3 and . The independently processed data clearly highlight that the TARLEM, integrating both reflective practice skills development and utilising ‘real-world’ case scenarios, strongly facilitated a successful professional practice transition as detailed in and and across three iterations.

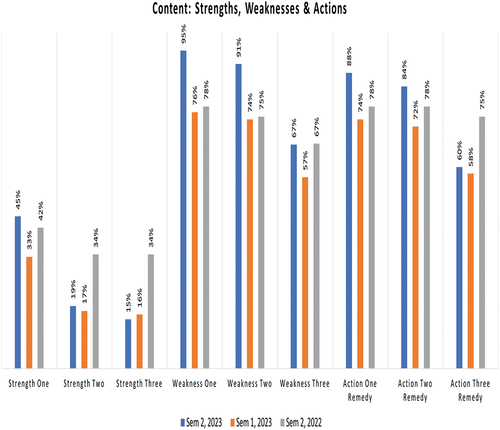

Figure 5. Preliminary report provided to clients – major individual project - value of client feedback provided for the students in identifying both strengths and weaknesses of investment recommendations and to then Be able to action remedies – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Figure 6. Preliminary report provided to clients – major individual project – extent of student use (yes or No) of professional practice-based, feedback analysis table provided across three iterations – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Of note, the level of successful transition to a professional practice ‘mind set’ generally increased () across the three iterations, for example, 95% of students were able to identify their primary, client identified, investment recommendation weakness in Semester Two, 2023 compared to 67% of students in Semester Two, 2022. The use of the key client feedback analysis table (an important tool for professional practitioners) also increased from 63% to 84% in the same time frame as highlighted in .

Thus, it is clear that the support processes included within the TARLE model were extremely successful in transitioning students to a society-based, professional practice focus. These TARLE-based resources included: the provision of expert led reflective practice workshops; the provision of annotated examples of effective/ineffective reports/advice to clients; and a sample report which utilised reflective prompts that related to the marking criteria.

6.2. Mandatory assessment task two

For Assessment Task Two, a mandatory, invigilated, final exam, reflection-based question, was based on an alternating, reflective, professional practice case study related to the social impacts of International Taxation or International Auditing business decisions. These case study scenarios and the associated, mandatory, final exam question, were again embedded into the IBU across three iterations within the integrated TARLE Model. For example, under exam conditions, the students were required to respond to a series of International Taxation questions related to profit shifting/use of tax havens and the impacts on both developed and developing nations.

To support the students in their transitioning from a focus on ‘self ‘and teamwork ‘peers’ to socially conscious, practitioners, a reflection-based support workshop was provided to students – on campus and recorded. This workshop utilised a practice case study scenario which assisted students to identify the relevant social impacts of international business activities.

Within this workshop specialist staff from the university’s, independent, Student Success Group (SSG), assisted students to develop the specialist skills needed to utilise the Four Rs of Reflection as developed by Bain et al. (Citation2002) and as set out in . These resources were provided on-campus (in lectures) and via a readily available support video for all students to access as needed. The use of this 4 Rs Model of Reflection was then expected as part of the final exam reflection question responses.

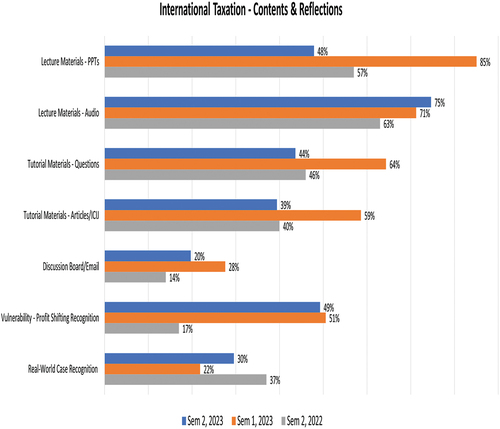

In addition, and as highlighted in , a wide range of lecture and tutorial materials were provided including; a complete set of lecture PPTs and related recordings; weekly tutorial/oral presentation questions; full PPTs and recordings of team-based oral presentations across all classes and for all three iterations; full recordings of one of the on-campus workshops each week for online students to review (many of these students were off shore); full tutorial/oral presentation solutions; a practice exam and a two-hour final exam revision workshop. The significant level of use of these resources is documented in .

Figure 7. Final exam reflection question – reflective professional practice case study – social impacts alternating case studies related to international taxation and international auditing – TARLE model-based support resource use across three iterations – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Of note, there were significant increases in engagement levels from the Semester Two, 2022 cohort to the Semester One classes in particular. There were two factors in play which contributed to these outcomes. Firstly, the research team, including the Unit Co-ordinator and the reflection-based, cultural competency experts and working from student feedback across iterations, provided additional support materials including a range of examples, highlighting how to apply the Four Rs of Reflection. These examples were disseminated by Discussion Board and Announcements to reach as many students as possible which created the opportunity for students to also respond to DB queries adding their own queries as well as staff/research team members. Thus, a network of professionally based collegiality and social empathy-orientated discussions took place across the student cohort.

The second factor of importance in terms of the data identified in was that the Semester Two, 2023, students had a lower level of overall engagement in lectures and tutorials than was the case in Semester Two, 2022 and Semester One, 2023. Thus, the Semester One, 2023 students, who were highly engaged in all their classes, accessed a higher level of resources than, the Semester Two, 2023 cohort. Additional assessment task restructuring within the TARLE Model is being conducted to provide assessment task marks for genuine levels of class-based participation for future iterations of this project which will take place in Semesters One and Two, 2024. This issue will be further highlighted in our overall conclusions and learnings in Section 7.

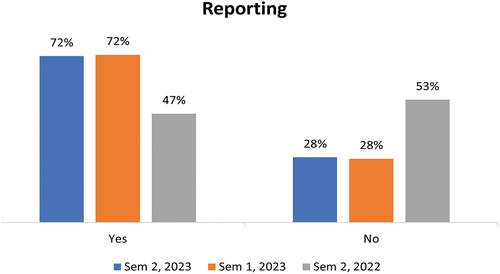

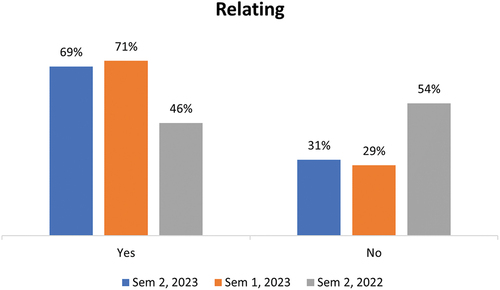

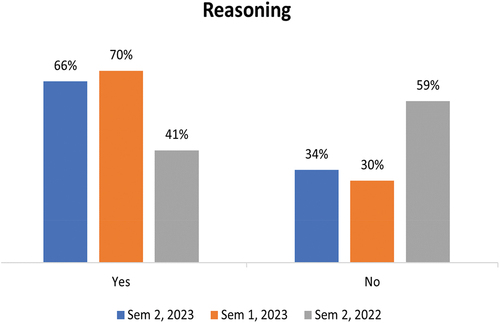

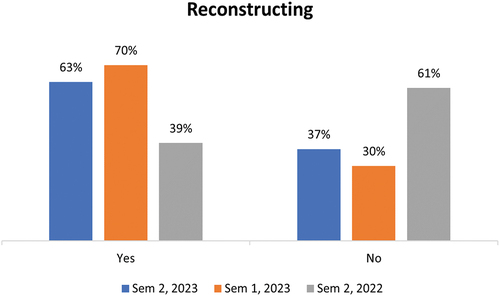

This same results pattern across the three iterations was also evident in the student use of the Four Rs of Reflection under exam conditions (Bain et al., Citation2002) with significant increases in the use of all four levels of the Four Rs of Reflection from Semester Two, 2022, to Semesters One and Two, 2023 ( and ). However, as discussed earlier, Semester One, 2023, student use of the reflective framework under exam conditions, exceeded, in all four reflection levels, the student use levels in the Semester Two, 2023 student cohort. However, even with lower levels of engagement in place, the resources embedded within the TARLE model continued to ensure that the generally less-engaged Semester Two, 2023, students continued to participate at the 63–72% level.

Figure 8. Final exam reflection question – four Rs of reflection model (Bain et al., Citation2002) – exam conditions – (students use reflection model – yes or No) across three iterations reporting dimension – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Figure 9. Final exam reflection question – four Rs of reflection (Bain et al., Citation2002) – exam conditions - (students use reflection model – yes or No) – across three iterations relating dimension – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Figure 10. Final exam reflection question – four Rs of reflection (Bain et al., Citation2002) – exam conditions - (students use reflection model – yes or No) – across three iterations reasoning dimension – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

Figure 11. Final exam reflection question – four Rs of reflection (Bain et al., Citation2002) – exam conditions – (students use reflection model – yes or No) – across three iterations reconstructing dimension – in order of latest research (sem 2, 2023).

7. Discussion and key learnings

7.1. Discussion

As detailed in Section Four, the two, mandatory, authentic assessment tasks generated within our Stage Two research were embedded within an integrated Experiential/Teaching and Assessing Reflective Learning Model (TARLEM) as set out in (TARL Model) and 4.1 (TARLEM). This model, created by the authors, successfully assisted UG students to transition from a ‘self’ and ‘peers’ (team members) focus to becoming external, reflective, and inclusive practitioners who valued shared social membership. This successful outcome is detailed in the results review provided in Section 6.

Of importance, and as in the highlighted, reflective student examples provided in Section 5.3., the support structure within the TARLEM model resulted in client-based recommendations for investment opportunities from the perspective of reflective practitioners which, firstly, indicated empathy with their client’s environmental priorities. Second, the examples provided also indicated significant empathy for the social impacts of their international business related, investment recommendations on our global society.

Also of significance was that the research methodology was based on a highly commended, ethics approved psychologically safe, ‘opt-out’ methodology. In turn, the data pool for all three iterations included all enrolled students who completed the mandatory major project and final exam authentic, assessment tasks.

A third point was that the IBU selected included cross-cultural/cross-discipline and online and on-campus students. Thus, the results could be fairly considered as generalisable to a wide range of units, faculties, and universities globally.

7.2. Key learnings

Within the author created, TARLE Model context, four key learnings from this face-to-face, intervention process are:

Building on our Stage One research learnings (2008–2019, 5603 participants), we believe that innovative curriculum and assessment design in the form of the Stage Two, uniquely integrated TARLE Model, can substantially support the transitioning of UG students, across disciplines and cultures, to become reflective and inclusive practitioners who value shared social membership. However, these beneficial outcomes required rigorous reflective learning processes as an integral part of transitioning interventions across three iterations.

Consistent with Edmondson (Citation2004), the success of our collaboration with three cohorts of students (622 responses) required students to feel ‘psychologically safe’ to not only participate in authentic assessment tasks but to also be able to provide honest reflective responses. This was particularly the case given the ethics approved, ‘opt-out’ methodology included students contacting the SSG in confidence if they wanted to withdraw from the project.

Thus, it was of significant benefit for the students to be able to work closely with the SSG reflective experts throughout the semester without fear of judgements or reprisals from academic staff. To further support this ‘psychologically safe’ environment for students to ‘opt out’ without concern, one of the key, ethics requirements for the approved methodology was that the SSG did not provide the academic staff with any details on any students who had withdrawn from the project, until AFTER the final exam results had been processed. Thus, no work commenced on the project by the research team until all results in the IBU had been processed and released officially.

(3) Our third learning from our Stage Two research was that the authentic assessment tasks needed to foreground the reason for the task, in terms of social impacts, and to ensure that each student could, in the end, see themselves ‘not as an isolated individual but as part of a wider society’ (McArthur, Citation2022). Within their formal assessment tasks, students must be able to understand both the relevant content issues and to be able to reflect on the social impacts of international business practices and their ability to work with their clients to foreground a sustainability agenda.

(4) As highlighted in the Results Section 6, the Semester One, 2023 students were highly engaged in all their classes, and, in turn, accessed a higher level of resources than, the Semester Two, 2023 cohort. The lower level of engagement by students generally within this latter cohort will be addressed in an additional assessment task restructuring within the TARLE Model for the Semesters One and Two, 2024, iterations. That is, modification to the mandatory assessment task ‘weighting’ will take place to provide assessment task marks for genuine levels of class-based participation.

Acknowledgment

I would also like to write an acknowledgment to Catriona Windsor, at the Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sue Taylor

Sue Taylor is a Senior Lecturer/Co-Ordinator, the Faculty of Business and Law, QUT, Qld., Australia, a Senior Fellow of the UK HEA and has participated as both a HEA Fellowship Reviewer and is an International Examiner for the Global Undergraduate Awards. She was winner of the 2020 Australian Awards for University Teaching – Citation for Outstanding Contribution to Student Learning and the winner of multiple other teaching awards including three Vice-Chancellor’s Performance Awards for Teaching Excellence. Her most recent research focus has been of the development of a holistic, inclusive and sustainable intercultural team building and peer review process which inspires students and staff to learn together with and through technology-enhanced, collaborative interactions.

Mary Ryan

Mary Ryan is Professor and Head of the Department of Educational Studies at Macquarie University in NSW, Australia. She is President of the New South Wales, Australia, Council of Deans of Education and is a Principal Fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy (HEA). Professor Ryan is also the recipient of an AAUT citation for outstanding contribution to student learning. Her research investigates discourses of literacy, learning, youth culture and teachers’ work.

Leonie Elphinstone

Leonie Elphinstone is an experienced psychologist in the area of cultural competence. She specialises in designing courses in the development of cultural competence for Business Faculties in Universities. As an accredited Advanced Cultural Intelligence (CQ) Facilitator and Trainer, she utilises the cultural intelligence model in training and presentations to provide strategies for flexibility in participants’ approaches and in order to maximise the advantages of the increasing cultural diversity within and between cultures.

Notes

1. As detailed in Table 4.2 of this 2021 article.

2. For example, in a prior research project within this same university, and involving more than 800 UG students which utilised an ‘opt in’ methodology, minimal student engagement took place in either the online, confidential survey, or in terms of the more than 100 confidential focus group opportunities provided over more than a 12-month period. The research team, with global expertise in designing assessment tasks which reduce barriers to understanding, met with every tutor and with every student attending any of the tutorials to ensure the students were familiar with the project aim of supporting inclusion within the class assessment tasks. The confidential nature of the independent team of researchers and all responses received were also emphasized, however, the response levels remained at a minimal level.

References

- Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., & Klusmann, U. (2022). Is empathy the key to effective teaching? A systematic review of its association with teacher-student interactions and student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 34(3), 1177–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09649-y

- Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2020). Guiding principles and standards for business accreditation,July 28, AACSB.

- Bain, J., Ballantyne, R., Mills, C., & Lester, N. (2002). Reflecting on practice: Student teachers’ perspectives. Post Pressed.

- Barnes, J. (1995). The Cambridge companion to Aristotle. Cambridge University Press.

- Boud, D. (1999). Avoiding the traps/seeking good practice in the use of self-assessment and reflection in professional courses. Social Work Education, 18(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479911220131

- Climate Council of Australia Ltd. (2022). The great deluge: Australia’s new era of unnatural disasters. Climate Council.

- Cook, C., Bay, D., Visser, B., Myburgh, F., & Njoroge, F. (2011). Emotional intelligence: The role of accounting education and work experience, issues in accounting education. American Accounting Association, 26(2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-10001

- Demetriou, H., & Nicholl, B. (2022). Empathy is the mother of invention: Emotion and cognition for creativity in the classroom. Improving Schools, 25(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480221989500

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A team-level lens. In R. Kramer & K. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239–272). Russell Sage.

- European Environment Agency. (2023). Disasters in Europe: More frequent and causing more damage. https://www.eea.europa.eu/subscription/eea_main_subscription/natural-hazards-and-technological-accidents/view

- Fleming, A. S., Pearson, T. A., & Riley, R. A. (2008). West Virginia university: Forensic accounting and fraud investigation (FAFI). Issues in Accounting Education, 23(4), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.2008.23.4.573

- Florian, L., & Linklater, H. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: Using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(4), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588

- Fridrich, A., Jenny, G., & Bauer, G. (2015, October 18). The context, process, and outcome evaluation model for organisational health interventions. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/414832

- Fuller, M., Kamans, E., van Vuuren, M., Wolfensberger, M., & de Jong, M. (2021). Statements and professional development programs of the institute of management accountants (IMA 2008), and the competency map of the certified management accountants of Canada (CMA 2010). Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(3), 333–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519211001125

- Furman, R., Coyne, A., & Negi, N. J. (2008). An international experience for social work students: Self-reflection through poetry and journal writing exercises. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 28(1–2), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841230802178946

- Gibbs, G. (1992). Teaching more students projects. Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council and Oxford Polytechnic.

- Graham, L. (2024). Inclusive education for the 21st Century: Theory, policy and practice (2nd ed.). Routledge Books.

- Graham, L., Tancredi, H., Willis, J., & McGraw, K. (2018). Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment. Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0266-y

- Hartwig, K., Stokhof, H., & Fransen, P. (2020). A new country, new university, new school – how do I cope? International student experiences. Journal of International Students, 29(S2), 1–10.

- Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2000). Kolbï’s experiential learning theory and its application in geography in higher education. The Journal of Geography, 99(5), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340008978967

- Jackson, J., & Oguro, S.). (Eds). (2018). Intercultural interventions in study Abroad, chapter one, introduction, enhancing and extending study abroad learning through intercultural interventions. Routledge.

- Knapp, R. (2010). Collective (team) learning process models: A conceptual review. Human Resource Development Review, 9(3), 285–299, at p.296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484310371449

- Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

- Kolb, D. A. (1981). Learning styles and disciplinary differences. In A. W. Chickering (Ed.), The modern American college (pp. 232–255). Jossey-Bass.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (vol. 1). Prentice-Hall.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- McArthur, J. (2022). Rethinking authentic assessment: Work, well-being, and society. Higher Education, 85(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y

- Mezirow, J. (2006). An overview of transformative learning. In P. Sutherland & J. Crowther (Eds.), Lifelong learning (pp. 1–12). Routledge.

- Morris, T. H. (2019). Experiential learning – a systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), 1064–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279

- National Audit Office/UK House of Commons 2018; UK Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee/UK Parliament. (2018). Institute for government summary, Sasse, T. Britchfield, C. and Davies, N. 2020. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/carillion-two-years-on.pdf

- Orland-Barak, L. (2005). Portfolios as evidence of reflective practice: What remains ‘untold’. Educational Research, 47(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188042000337541

- Peisachovich, E., Kapoor, M., Da Silva, C., & Rahmanov, Z. (2023). Experiential learning approaches for developing professional skills in postgraduate engineering students. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36076

- Queensland University of Technology. BluePrint 6 2023, George street, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810210400402

- Ryan, M., & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

- Snepvangers, K., & O’Rourke, A. (2020). Creative practice as a catalyst for developing connectedness capabilities: A community building framework from the teaching international students project. Journal of International Students, 10(S2), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10iS2.2762

- Taylor, S., Ryan, M., & Elphinstone, L. (2021). Generating genuine inclusion in higher education utilising an original, transferable, and customisable model for teaching and assessing reflective learning. Reflective Practice Journal, 22(4), 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1933408

- Taylor, S., Ryan, M., & Elphinstone, L. (2023). HERDSA 2023 annual conference, Brisbane, 7th July, showcase presentation – transforming disciplinary knowledge to achieve an empathetic change in society: Authentic Assessment’s role in fostering shared social membership and inclusion.

- Taylor, S., Ryan, M., & Pearce, J. (2015). Enhanced student learning in accounting utilising web-based technology, peer-review feedback and reflective practices: A learning community approach to assessment. Higher Education Research and Development, 34(6), 1251–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1024625

- Taylor, S., Ryan, M., Pearce, J., & Elphinstone, L. (2017, March 20). Enhancing integration within Australia’s globally engaged university sector: Bridging cultures and transforming student learning and assessment in accounting. Oxford Education Research Symposium, St Hugh’s College, Oxford, UK.

- Thorpe, D. S. (2016). International conference on engineering education and research, Sydney, Australia. Experiential learning approaches for developing professional skills in postgraduate engineering students, Sydney, Australia (pp. 1–8).

- The Times. (2022, December 27). Ben Clatworthy. United Kingdom. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/uk-weather-counting-the-cost-after-year-of-climate-disaster-hp998969r).

- United Nations Development Goals. (2015). Department of economic and social affairs sustainable development, transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

- United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. (1976, October 22). Article 13, international covenant on economic, social, and cultural rights. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx

- University of Oxford. (2017). International trends in higher education 2016–17. International Strategy Office.

- Van Akkeren, J., & Tarr, J. A. (2022). The application of experiential learning for forensic accounting students: The mock trial. Accounting Education, 31(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2021.1960573

- Visco, & Murrell. (2022, September 21). Aligning Student learning outcomes with assessment, association to advance collegiate schools of business. https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2022/09/aligning-student-learning-outcomes-with-assessment

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932

- Wolf, M. J., Emerson, J. W., Esty, D. C., de Sherbinin, A., & Wendling, Z. A. (2022). 2022 environmental performance index. Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. epi.yale.edu