Abstract

Research on compact cities repeatedly reveals inadequate amounts of land for outdoor recreational activities. However, few studies examine the practices of planning outdoor recreation in the compact city. This study explores the integration of sites for outdoor recreation into the compact city using a Swedish municipality as a case study. The paper draws on material semiotics to show the existence of several parallel planning trajectories, of which only certain adhere to the compact rationale. Results indicate a need to overcome administrative silos and suggest the potential of engaging with past planning for addressing the multifaceted topic of outdoor recreation.

Introduction

The compact city paradigm has become the dominant narrative in urban planning (Bibri et al., Citation2020; Kjærås, Citation2021; Pérez, Citation2020; Sharifi, Citation2016). With its “modern high-rise buildings and high-tech mobility infrastructure” (Haarstad et al., Citation2023, p. 6) the compact city promises more attractive urban areas and a radical break with late-modernist spatial planning. Research indicates that the mixed land-use pattern of the ideal compact city, characterised by proximity among housing, services, leisure opportunities, and public transport, leads to reduced greenhouse gas emissions due to the increased adoption of sustainable modes of travel (Kain et al., Citation2022). Besides offering a sustainable alternative to sprawling urban forms, the compact city is also claimed to be health-promoting. ‘Walkable’ neighbourhoods with mixed-use functions are frequently claimed to have positive health effects (Heinen et al., Citation2010; Sallis et al., Citation2016). Despite this, research on outdoor recreation and green spaces repeatedly shows that compact city forms fail to provide sufficient spaces for outdoor recreation (Haaland & van den Bosch, Citation2015; Hautamäki, Citation2019; Lennon, Citation2021; Qviström et al., Citation2016). A contradiction thus emerges between the compact city as a model for urban sustainability and public health, and the seeming difficulty of engaging with geographies of health, especially in the form of publicly accessible sites for outdoor recreation (Balikçi et al., Citation2022), which are important for promoting mental and physical health (ten Brink et al., Citation2016). The purpose of this paper is to probe deeper into this identified contradiction and scrutinise local planning for outdoor recreational sites in Sweden in order to address the rationales guiding the ‘practice of provision’ (Boulton et al., Citation2018) in the context of compact city development. Taking theoretical inspiration from science and technology studies (STS), the paper discloses how, in the face of compact urban ideals, sites for outdoor recreation are continuously made possible to plan, but only via certain practices and techniques.

Outdoor recreation in the compact city has been researched from multiple angles. GIS, surveys, and statistics are used to examine individual practices and preferences (see e.g., Hegetschweiler et al., Citation2017; Komossa et al., Citation2019; Lehto et al., Citation2022; Lindholst et al., Citation2015; Zhou et al., Citation2021), while qualitative studies explore experiences of using outdoor recreational amenities, their perceived accessibility, and their (un)just distribution (Børrud, Citation2016; Flemsæter et al., Citation2015; Gurholt & Broch, Citation2019). Further studies examine couplings between urban green space as an ecosystem service and as an amenity for outdoor recreation (see e.g., Jansson, Citation2014; Russo & Cirella, Citation2018; Tzoulas et al., Citation2007). However, Boulton et al. (Citation2018) argue that studies pay insufficient attention to factors shaping the ability of local governments and their planning offices to supply urban green space; in particular, there is a need for more qualitative studies. Furthermore, studies of the operational and conceptual ambiguities of green space policy indicate the need for closer scrutiny of the ways policies are implemented in daily practice (Hislop et al., Citation2019). Thus, more research is needed on the “practice of providing greenspace” (Boulton et al., Citation2018, p. 86). While Boulton et al. (Citation2018) refer to the provision of urban green space in general, this paper focuses on planning spaces for outdoor recreation – through specific amenities, land use designations, or other means. This includes programmed spaces (e.g., football pitches, skate parks, tennis courts) as well as less programmed spaces (e.g., urban forests, parks, roaming areas) for both organised or non-organised activities, performed in a group or individually. This width of spaces mirrors the results from a recent survey conducted by the European Union (Citation2022) on the preferred spaces for physical activities among Swedish residents. The survey reports that conducting physical activities outdoors, in parks, or on the way between the home, work or school is more common than conducting physical activities at sports fields or similar. This tendency, which is also visible at the EU scale (ibid.), indicates that outdoor recreation is a practice that spans over a multiscalar and multifaceted landscape (see also Skriver Hansen, Citation2021) and includes both formal and informal activities, and thus requires a planning practice able to encompass a diversity of spaces. The trend of conducting outdoor recreational activities away from programmed sports fields could be understood as a result of a decreased interest in participating in organised sports and sports associations, in favour of spontaneous and individually conducted physical activities (Hedenborg et al., Citation2022). Though, sports associations still hold important positions in civil society (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2016). This indicates the importance of a broad provision of a diversity of spaces, for organised as well as non-organised activities, integrated and easily accessible in the urban fabric.

The paper adopts a material-semiotic approach, taking inspiration from scholars interested in the modification of planning issues (Asdal, Citation2015; Asdal & Hobæk, Citation2016, Citation2020) and the work dedicated to rendering complex issues as possible to plan or making issues plan-able (Valve et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Empirically, the paper presents a case study of municipal urban planning in Sweden. The compact city paradigm is influential in Sweden, where it is closely intertwined with discourses on urban sustainability (Bibri et al., Citation2020; Zalar & Pries, Citation2022). In debates on national and local development policies and plans, a densified and compact city is repeatedly described as the only viable sustainable future (Lisberg Jensen et al., Citation2023; Tunström, Citation2007). Swedish authorities also point to the health benefits of compact cities, especially their potential to increase active modes of transportation (see e.g., Boverket, Citation2022). The comprehensive integration of multiple policy fields lies at the core of the Swedish planning system (Schmitt & Smas, Citation2020). In this context, how spaces for outdoor recreation are being integrated into urban, compact, fabrics merits further scrutiny.

Following this introduction, I briefly describe the Swedish planning system. A section on the theoretical underpinnings of the paper leads to a description of the methods and materials employed. I then present the case study of Upplands Väsby Municipality and examine the processes of making outdoor recreation plan-able (Valve et al., Citation2022) in the compact city. The paper ends with a discussion and concluding reflections.

Outdoor Recreation and Compact Cities in Swedish Urban Planning

Urban planning in Sweden is largely the responsibility of 290 municipalities, which have a monopoly on urban planning. National legal frameworks, principally the Planning and Building Act (SFS Citation2010:900) and the Environmental Code (SFS Citation1998:808) prescribe planning processes and tools but leave it up to local municipalities to determine the contents of land use plans. Land use planning is steered mainly by two types of plans: the municipal comprehensive plan (översiktsplan) and detailed development plans (detaljplan). The comprehensive plan is a political document setting out the vision for the future development of the municipality and is not legally binding. The detailed development plan is legally binding and regulates land use and building techniques in a specific limited area of the city.

The Swedish planning system is often described as comprehensive and integrative, whereby public bodies, i.e., municipalities, have responsibility for spatial coordination and horizontal integration of multiple policy sectors (Schmitt & Smas, Citation2020). This also entails balancing public and private interests and determining the spatial distribution of public and private amenities in the urban fabric (see Bjärstig et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a key challenge facing Swedish planning authorities is to determine how diverse planning topics, stemming from different policy sectors, relate to each other within the common “spatio-legal framework” (Rannila, Citation2021) of land use planning. This is especially challenging since different policy sectors adhere to “diverging spatial logics” (Schmitt & Smas, Citation2020, p. 7), supported by potentially conflicting political or economic rationales. This raises questions regarding how the integration of different planning issues takes place in practice.

Today national or regional guidelines for recreational planning in Sweden are scarce, even though rhetoric on the benefits of recreation, especially in the outdoors, features prominently in both national and local policies (Bergsgard et al., Citation2019; Petersson-Forsberg, Citation2014). In the absence of national guidelines, it is up to local politicians, in conversation with local planning officers, to incorporate outdoor recreation in the municipal comprehensive plan and subsequent detailed development plans. These tasks have been identified as a challenge for local planning authorities (Stenseke & Hansen, Citation2014).

The integration of health and outdoor recreation into urban planning is not a new concern in Sweden. Outdoor recreation, leisure and sports figured prominently in Swedish planning at the height of the welfare era in the 1960s and 1970s (Pries & Qviström, Citation2021). During this period, the broad interest in sports and outdoor recreation was supported by extensive research, policies, norms and regulations (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2016; Giulianotti et al., Citation2019; Idrottsutredningen, Citation1969), which materialised in outdoor recreational sites throughout Sweden (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2016; Pries & Qviström, Citation2021; see also Braae et al., Citation2020) in the forms of sports halls, roaming areas, running paths, tennis courts and many other amenities. Critics of modernist planning (se e.g., Mehaffy & Haas, Citation2020) often fail to acknowledge the central role of landscape and leisure planning in Swedish urban planning in the mid-twentieth century (Hautamäki & Donner, Citation2021; Kärrholm & Wirdelöv, Citation2019; Pries & Qviström, Citation2021; Valzania, Citation2022).

Making Outdoor Recreation Plan-Able

How to plan spaces for outdoor recreation is not immediately evident. Rather outdoor recreation, as other complex or multifaceted topics, needs to be addressed through processes of delineation, interpretation and categorisations in order to be framed into more or less stable planning interventions (Asdal, Citation2015; Asdal & Hobæk, Citation2016). Asdal (Citation2015) names this process of framing phenomena into manageable topics as the process of formulating planning ‘issues’, pointing to the everyday work at play in ‘sorting out’ complex or contested phenomena. Defining how planning issues can be operationalised and made tangible in the landscape is thus a central task of planning and as Valve et al. (Citation2013; see also Valve et al., Citation2022) phrase it, a way of rendering planning issues as plan-able. This process of securing plan-ability could, as Valve et al. (Citation2022) argue, be seen as an ontological work as it delineates a particular version of the issue at hand via mobilising actors into a shared analytical frame, and subsequently translates and operationalises policy objectives into schemes of implementation. However, this trajecotry is far from linear but rather experimental and requires repeated efforts to re-stabilise and re-frame issues as contexts and conditions changes (ibid.).

Studying the ‘practice of provision’ of spaces for outdoor recreation would, from this Science and technology studies inspired perspective, suggest following how outdoor recreation is interpreted and delineated (what the issue of outdoor recreation is and what the spatial forms of the issue are). Secondly, following how the issue becomes implemented, looking into the techniques used to operationalise outdoor recreation and following the material arrangements that are suggested based on those operationalisations.

As earlier researchers of compact cities with attention to material-semiotic relations have pointed out (see e.g., Kjærås, Citation2021; Pérez, Citation2020) it is not sufficient to address planning processes as separate from addressing material constitutions, and distribution, of sites. Instead, a material-semiotic perspective can be a tool for addressing the complex arrangements found in urban planning (Asdal, Citation2015; Valve et al., Citation2017). From elements such as political narratives, to charts, maps, lists and categorisations of land and its uses and the situatedness and landscape of the sites themselves, outdoor recreation becomes sorted out, framed, and shaped into phenomena that are amenable to the institutional technologies of urban planning (Li, Citation2007; Valve et al., Citation2013).

Methods and Materials

The paper is based on a case study of Upplands Väsby, a mid-sized Swedish municipality located between Stockholm and Uppsala. The selection was based on an initial search for cases across the Stockholm capital region, an area characterised by compact city developments and urban densification. Upplands Väsby is identified as a strategic area for urban expansion in the Stockholm Regional Plan (Region Stockholm, Citation2018). This, together with the prevalence of major ongoing developments accompanied by a rhetoric of compact city making, and a documented history of acclaimed recreational planning (see Pries & Qviström, Citation2021) formed the basis for selection. Thus, Upplands Väsby is used as a paradigmatic case of outdoor recreational planning in a Swedish compact city under construction.

The case study draws on a variety of documents produced by the municipality concerning land use planning, urban development, outdoor recreational planning, and maintenance of recreational amenities (see ). Following Asdal (Citation2015) and Asdal and Reinertsen (Citation2021) I perceive these planning documents and policies as active elements in shaping the issue of outdoor recreation as well as the material constitution of sites for outdoor recreation.

Table 1. Plans, policies and documents from the case study. Titles translated from Swedish by the author.

The written material was supplemented with eight qualitative interviews with municipal employees (see ). Selection of interviewees was based on their roles within the municipal organisation and their involvement in strategic work within their respective departments or sub-departments, or in multiple large-scale development plans and projects.

Table 2. List of interviewees and their main responsibilities.

The interviews were semi-structured and conducted in Swedish. They lasted from 40 to 60 minutes and were recorded and then transcribed. All quotes that appear below were translated into English by the author. Analysis of the interviews loosely followed Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) description of thematic analysis. The first coding was made by collecting codes that appeared frequently in the interview transcripts. The coding was influenced by empirical observations in previous research that identified conflicts between urban densification and outdoor recreation (see e.g., Haaland & van den Bosch, Citation2015; Hautamäki, Citation2019; Zalar & Pries, Citation2022). This generated codes that, from multiple angles, captured perceived obstacles, practical everyday work tasks, descriptions of responsibilities and knowledges regarding outdoor recreation. These codes were then collected into themes. This step of the analysis brought in notions from the theoretical foundation, putting attention to how the issue of outdoor recreation was formulated and operationalised. A third step of analysis followed, where themes were revised and analysed with attention to how the issue(s) of outdoor recreation became rendered into the material and geographical arrangements, looking at maps, renderings, descriptions of any geographical or material elements concerning outdoor recreation.

Upplands Väsby: A Compact City in the Making

Upplands Väsby Municipality covers roughly 84 square kilometres and most of the 47,000 inhabitants live in the central urban area surrounding the commuter train station. From its beginnings as a low-density semi-rural area in the early twentieth century, Upplands Väsby experienced a rapid wave of urbanisation starting in the 1950s and culminating in the 1970s with the building of a new commercial and public centre, surrounded by both low- and high-rise residential buildings. These residential and commercial areas are still dominating the urban landscape, however increasingly embedded in new residential developments.

According to official projections, the population of Upplands Väsby will grow to 63,000 inhabitants by 2040. This expected increase in population is linked to expansive urban development, which is supposed to transform Upplands Väsby from a “suburb” to a “city” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018c). The creation of this new city implies extensive densification and restructuring of the existing urban environment. Outdoor recreation, such as health and sports, are mentioned as crucial elements for the future compact city, as aspects contributing to good quality of life (ibid.).

Outdoor recreation impinges upon the work of several municipal departments, as displayed in . However, the main actors involved in planning, maintaining, and developing sites for outdoor recreation can be found at the Department of Planning (via land use planning) and the Department of Culture and Leisure (via management of facilities and in the role of specialist in sports and recreational governing).

Table 3. Organisation of committees and departments in upplands väsby municipality with a short and selective description of each department’s responsibilities. Source: www.upplandsvasby.se.

The following four sections present results from the thematic analysis of interviews and studies of municipal documents. The results are interpreted according to the theoretical frame of the paper, seeking to address how the issue of outdoor recreation is defined, how it is operationalised and what material arrangements such operationalisations suggest. Four parallel planning trajectories become visible following this interpretive work, indicating that outdoor recreation is rendered plan-able under different guises: as quality, as programmed amenities, as a temporal strategy, and as an ecosystem service.

Outdoor Recreation as Quality

Firstly, the result shows a planning trajectory portraying outdoor recreation as an issue of quality to include in the compact city. In the strategic planning of the municipality, density is visualised as a non-diversified space, and in this space outdoor recreation appears as a quality, but how this quality is to be materially provided is not specified.

In the municipal comprehensive plan, which sets out the aim of transitioning from suburb to city, access to a wide range of small and large recreational amenities is held to be a positive quality. However, the plan does not address the location of new outdoor recreational spaces. It focuses instead on future needs for indoor facilities, stating that “by the year 2040 at least four additional sports halls, three gymnasiums, three synthetic grass football pitches and one indoor ice rink will be required” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018e, p. 48), a calculation based on population forecasts. The location of these additional facilities is not specified. While the comprehensive plan combines the interests of all municipal departments and sectors, it is combined and produced at the Department of Planning.

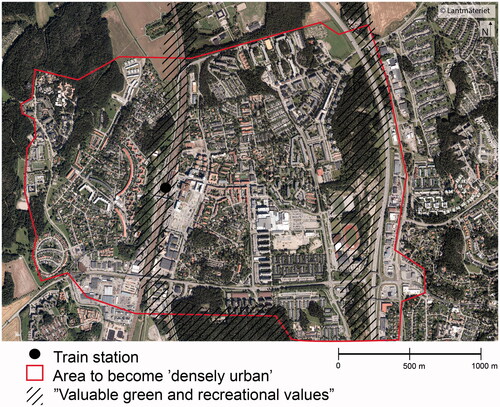

The exclusion of outdoor recreational sites in the strategic plans for Upplands Väsby is visible in the comprehensive land use map. The map, a compulsory component of the comprehensive plan, defines four main building typologies: ‘rural,’ ‘small-scale,’ ‘medium-dense’ and ‘dense urban.’ The area allocated to ‘dense urban’ development appears on the map as an undifferentiated surface covering most of the central area of the municipality (see ). This contrasts with earlier comprehensive land use maps, where new developments and planned interventions were defined spatially down to individual premises (see e.g., Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2005). Interviewee 1, a comprehensive planning officer, comments upon this imagery:

Figure 1. Central Upplands väsby, showing the area demarcated as “densely urban” in the comprehensive plan and the location of two areas containing “valuable green and recreational values.” Aerial photo from lantmäteriet ©, modified by the author.

As far as I understand, there were quite far-reaching discussions; the main point is that we don’t [spatially] define anything in this compact city, we just assume that it will work.

This way of displaying the future city of Upplands Väsby is more than solely a design choice; it effectively pushes potential land-use conflicts to a later stage in the planning process, when priorities among multiple uses will inevitably have to be assigned.

To operationalise the ‘dense urban’ building typology, the municipality makes use of the Swedish concept stadsmässighet, which can be roughly translated as ‘functioning as a city’ (Tunström, Citation2007). The concept implies a collection of more or less explicitly defined urban qualities (Metzger & Wiberg, Citation2017), and aligns closely to the international model of new urbanism. Stadsmässighet is often used normatively to denote a city characterised by streetscapes laid out in a grid pattern, clearly referencing a nineteenth-century urban form and sharply demarcated from the modernist “suburban” building typology (Tunström, Citation2007). In the context of Upplands Väsby, the concept of stadsmässighet is defined in two policy documents, from 2013 and 2018 (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2013, Citation2018c). The definition is in the form of a list of nine qualities that a city should strive to attain, including, among others:

Frequently used public spaces, including parks for recreation

Experiences, such as spontaneous sports

Clear boundaries between public and private [spaces] that are “naturally intelligible.”

Diversity and variety

Social and ecological growth

These qualities are to be developed by a set of design features summarised in another list, including:

Buildings of variable designs, heights, and forms of tenure

Building typologies that delineate and create streets, places and parks with clear distinctions between public and private

A streetscape that contains active ground floor uses

A streetscape where multiple modes of traffic coexist

An ecological and socially multifunctional urban structure, rich in ecosystem services and meeting places

The policy implies moving beyond a modernist planning legacy. This includes replacing traffic separation, green open spaces (described in the policy as a “no-man’s-land” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018c, p. 9)) and spacious building typologies with a compact, mixed city, bound together by a grid street pattern. The vague land use map and the elusive qualities of urbanity are translated into strategies for ordering urban materialities into city blocks and specific schemes for streets and public spaces. Outdoor recreation is included in the list of qualities of the compact city but excluded from the design features, which focuses on the arrangement of streets, facades and buildings. Depictions of an elusive ‘densely urban’ future effectively leave future outdoor recreation as an unmapped and unpredictable land use (c.f. Zalar & Pries, Citation2022).

The Department for Culture and Leisure has recently developed a new “sports strategy” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2019a), the first since 1980. The plan does not discuss where sports or recreational activities are to take place, instead focus lies on questions of equal access to participation in both organised and unorganised sports.

This approach to planning outdoor recreation, which acknowledges its value but disregards its spatiality, is only made possible by an unspoken reliance on the products of past recreational planning inspired by the modernist planning paradigm from which the municipality so keenly wants to escape. It is assumed that future residents will continue to make use of recreational amenities, including sports fields, urban forests and sites, dating back to the 1960s and 1970s (see e.g., Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2017).

Outdoor Recreation as Programmed Amenities

Secondly, in opposition to rendering outdoor recreation as an issue of qualities, another planning trajectory pushes the view of outdoor recreation as a question of well defined, and well programmed, recreational sites. By leaning on the long history of both sports associations, and of the existing outdoor recreational sites of the municipality, operationalising planning interventions becomes a challenge of maintenance.

For the Department of Culture and Leisure, arguing in favour of protecting and expanding existing outdoor and indoor recreational amenities is part of their everyday work, especially in response to current proposals for compact urban development. Access to land is a central topic of concern, as described by Interviewee 8:

If the priority is to densify the already densely populated areas, well then maybe a sports hall will not be the highest priority. Then there is no room for [recreation] in the dense urban area. And then one can ask, where can recreation take place?

Given the challenges involved in finding new sites to expand the recreational landscape within the compact city, the additions of new functions at existing sites represents a more feasible strategy. Examples include adding a new obstacle course alongside an existing running path; drawing new maps of proposed running routes; and adding new features such as parkour tracks and outdoor gyms to existing recreational sites.

Vilundaparken, where the new parkour track depicted in is located, is a focal point for outdoor recreational activities and outdoor recreational planning initiatives. With a history dating back to the 1960s, Vilundaparken have since then been a central feature of the intricate landscape of linked public green spaces and recreational sites within and adjacent to residential areas (Upplands Väsby kommun, 1979, Citation2008). A recent planning proposal would disrupt this historical trajectory by adding residential developments to the area, rebranded as “Väsby Sports City” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018d). Although planning of the new sports city is currently paused, due to unresolved issues of ground water protection, the idea of densifying the space by incorporating new residential buildings and services is still prominent in municipal marketing materials.

Figure 2. Three examples of new features added to existing recreational facilities and streetscapes. Photos by the author.

While the construction of Väsby Sports City remains on hold, a new indoor football hall was recently opened adjacent to the project area. The new football hall was built in response to energetic lobbying by local sports associations (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2022). However, the hall does not add to the exiting recreational supply, but rather replaces two outdoor gravel football pitches. Furthermore, the decision to construct the new football hall was made outside of the conventional planning process, without the production of a new detailed development plan for the area. The budget for the project covers the bare minimum: a full-size indoor football pitch on artificial grass, but with no changing rooms, additional parking spaces or other services (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2019c). How the closed-off, boxy building with an indoor 11-player artificial grass playing field will be fitted into the dense mixed-use building typology with active ground floors depicted in plans for the ‘Sports City’ remains to be seen.

The example of the new football hall highlights the central role played by local sports associations. Given the lack of national norms and standards, the needs of sports associations become a central factor underpinning arguments in favour of investment in new recreational amenities, indoors and outdoors. According to Interviewee 8, this leads to concerns about local democracy. Sports associations only enrol part of the total population and therefore cannot be seen as reflecting the overall needs and wishes of people in the area. Furthermore, some associations are more forthright than others in voicing their demands and, in the words of the interviewee, “put pressure on local politicians and local media.”

From this perspective, the absence of such programmed provision to meet the needs identified by the Department for Culture and Leisure, outdoor recreation only becomes plan-able by a continuous re-ordering and refinement of existing programmed sites, separately from spatial planning at large.

Outdoor Recreation as a Temporal Strategy

Thirdly, it is possible to detect a planning trajectory drawing in a rather different set of elements than seen in the previous two. Local political debates and a sense of urgency for decision-making, coupled together with public space design initiatives lays ground for ad hoc investments and a scattered geography of outdoor recreation.

Interviewee 1, a detailed planning officer, reflects on the combination of urgency for decision-making and lack of available land for outdoor recreation:

From a political point of view, there are different interests [that want to] develop different kinds of sports facilities and it […] is often very urgent […] and in the end, they have to be put where there is space; and there is not so much space in what is densely urban today.

As elections for the local municipal government are held every four years, decisions regarding investments and the provision of outdoor recreational amenities can become tangled up in local political debates. An example of this is the longstanding debate about the plans for a skate park in Smedby, a residential area in south-central Upplands Väsby. Following years of political and public debate on funding for the project and where it should be located, a project start date was set for 2017. However, funding was withdrawn following municipal elections in late 2018. The project was restarted in 2019, but at a different location, at the existing sports complex in Vilundaparken (Salmaso, Citation2020; Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018b, Citation2019b). A report by the Department of Culture and Leisure states that local sports associations based in Vilundparken see the plan as a “short-term solution, which hampers development of existing sports in the area.” The report notes the absence of a “holistic approach and a long-term strategy” for the recreational use of Vilundaparken (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2019b, p. 2). This example illustrates the difficulty of adding a new facility to an existing mix of facilities.

Planning new amenities in tandem with new residential areas, as part of detailed development plans, could, in theory, make it easier to set aside land for recreational use. However, this is not always the case, according to the interviewees. While the language of the comprehensive plan is too vague regarding locations of outdoor recreational amenities, the detailed development plans have limited scope to contribute to policy decisions. Reflecting on this gap between policy levels, one interviewee explains that the limited geographic scope of the detailed development plan makes it a blunt instrument for recreational planning (see also Petersson-Forsberg, Citation2014). Legally, a detailed development plan can only regulate land use within the project perimeter, often covering little more than a single city block. As noted by Interviewee 5, the subsequent “fine-scale planning” and “furnishing” of public places lie outside the formal planning process, as things that happen only after the plan has received formal approval. The same applies to compensatory actions taken when densification forces recreational amenities to relocate. For example, in a recently adopted detailed development plan for one of the major densification projects, planning for outdoor recreation is explained in the following terms:

The proposed plan implies that existing tennis courts will be used for new buildings. Investigation [to identify] a new location is ongoing. The plan proposes [creation of] a public park along the stream with new activity areas that could include [an area for] boules, a playground and spaces for activities (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2017, p. 15)

The high priority accorded to compact developments, the limited geographic scope of detailed development plans, and ad hoc political decision-making, hamper engagement with outdoor recreation from within the detailed planning process. Thus, decisions on outdoor recreational provision are pushed back to the final stages of development, when furnishing and setting the detailed design of public space.

Outdoor Recreation as an Ecosystem Service

Fourth, a parallel trajectory to render outdoor recreation plan-able is via the terminology of ecosystem services. Outdoor recreation as an issue of cultural ecosystem services enables its operationalisation firstly into blue and green values, which should enable outdoor recreational possibilities, and in a second step, into specific elements of the urban environment, such as green rooftops, flower planters and stormwater dams. Upplands Väsby Municipality pays close attention to ecosystem services, in line with recent national guidelines (Miljödepartementet, Citation2017), and a plan for protecting and expanding ecosystem services throughout the municipality was recently produced (Upplands Väsby Kommun & Ekologigruppen, Citation2016). The work with ecosystem services is conducted within the department of planning by experts in environmental planning. Cultural ecosystem services identified by the municipality include those related to health and leisure experiences, a category which includes outdoor recreation, in the form of access to nature. Nature, in this context, comes in a variety of forms. According to Interviewee 5, individual trees in the streetscape “contribute lots of ecosystem services, including recreation and wellbeing.” The idea that a few trees along a street are a recreational amenity betrays an understanding where outdoor recreational values are calculated and quantified as a collection of discrete points.

Using ecosystem services as a proxy for outdoor recreational values is an effective strategy for fitting recreation planning to the limited geographic scale of detailed development plans. At this scale, Interviewee 1 explains, “There is a focus on green and blue values. It is very seldom [that anyone says] ‘maybe we should take the opportunity to build a sports hall here’.” This relates to the difficulty of demonstrating social, or cultural, values through the framework of ecosystem services. Social values escape the confinements of quantification (cf. Setten et al., Citation2012) and as such are “difficult to evaluate” after the plan is realised, as explained by Interviewee 2.

In one major development area surrounding the train station, Upplands Väsby Municipality is working extensively to add green and blue features into the urban fabric. Under the heading of “passages for recreation” the plan explains that the design of streets will make them “recreational and rich in experiences.” This is to be done by creating urban squares that also function as parks, incorporating “trees and other vegetation that improves the microclimate and … reinforces ecosystem services in the area” (Upplands Väsby kommun, Citation2018a, p. 31). On the one hand, outdoor recreation is abstracted as a service “disconnected from the complexities of the social world” (Setten et al., Citation2012, p.305); at the same time, it is simplified and solidified into discrete entities.

Discussion

The paper set out to scrutinise local planning for outdoor recreational sites to address the practice of provision in the context of Swedish compact city making. The results have shown that there is not one practice of provision, but several, as seen in the different planning trajectories described above. While consensus prevails on the importance of outdoor recreation, tensions emerge when ‘outdoor recreation’ is to be defined as a plan-able issue and operationalised into specific material arrangements (c.f. Valve et al., Citation2017). These material arrangements are, to varying degrees, successfully integrated into the cityscape and will by extension influence how and where urban residents may conduct their everyday outdoor recreation.

Rendering outdoor recreation as an aspect of ecosystem services, and thereby also of ecological sustainability, is an effective way of modifying it into a plan-able issue. So is also the move to define outdoor recreation as a non-localised quality of life in the compact city, as seen in the narrative of Stadsmässighet. Both these versions of outdoor recreation are portrayed as realisable through streetscapes, green roofs, amenity planting, or urban parks; and therefore, as Hautamäki shows, “conceptualised and modified to fit in with the compact city policies and fulfil the priority of densification” (Citation2019, p. 27). Similarly, it is also possible to insert smaller, local initiatives into the dominating logic of compactness. Outdoor gyms in parks, mapped walking routes through the cityscape, and activity areas for spontaneous sports adjacent to playgrounds are all spatially limited enough to be ‘furnished’ at later stages of site development. The furnishing of streetscapes thus becomes an important means of providing opportunities for spontaneous recreation but as elements of design rather than a question of planning. Safeguarding extensive places for amenities, as demanded by sports associations, proves to increasingly conflict with the goal of compactness. The facility-based approach of outdoor recreation provision continues to evolve in the work of the Department of Culture and Leisure, but only through the more intensive use of existing sites already demarcated for recreational use.

Hence, if planning for compact cities, in Sweden and elsewhere, continues to enforce an understanding of outdoor recreation as primarily a question of ecosystem service or as a non-materialised quality one runs the risk of marginalising the material geographies supporting other – more space-consuming – forms of outdoor recreation, a negative process that is already underway (Jansson & Schneider, Citation2023). The results also indicate a possible conflict emerging between sites for specialised or indoor recreational activities, especially if advocated by local sports associations, and non-programmed urban green spaces for non-organised outdoor recreation. This is an unfortunate direction as informal recreational activities are increasingly popular, while participation in sports associations is reducing in Sweden (Hedenborg et al., Citation2022).

In the Swedish case, safeguarding, refining and expanding existing legacies of modernist leisure planning provides one way of securing the continuous provision of outdoor recreational sites. Even though the compact city is portrayed as a new alternative to a past era of modernist planning, it remains dependent on past planning for recreational provision. Planning for outdoor recreational sites is thus caught between the political vision of the compact city, supported by national and international research that argues for a break with a modernist urban planning legacy (see also Kärrholm & Wirdelöv, Citation2019; Zalar & Pries, Citation2022), and continued dependency on a leisure planning legacy in the form of sites for outdoor recreational purposes.

Concluding Reflections

This paper shows that, despite its precarious position in the compact city, outdoor recreation is still on the agenda for urban planners, albeit in a marginal position. Outdoor recreation is not posed as an opposition to the compact city, neither in interviews nor in documents, but only if outdoor recreation is rendered as compatible to the advocated form of a compact city. Hence, the paper discloses how the processes of rendering outdoor recreation as a plan-able issue are multiple. Even if integration between sectors appears at an analytical level – relating to the consensus of the need and importance of residents’ access to outdoor recreation – tensions emerge when operationalisations adhere to diverse spatial logics.

Valve et al. (Citation2013) use plan-ability to point to the experimental aspects of planning, where issues need to be formulated, tested, and repeatedly sought to be stabilised. The aspect of experiment is present also in the case of recreational planning in Upplands Väsby. However, what becomes visible is how the use of the material inertia of existing recreational landscapes acts as a prerequisite for such experimentalism, as an infrastructure that keeps providing recreational opportunities that the compact city cannot (such as multiscalar green landscapes and extensive sites for organised and non-organised sports). Nevertheless, diminishing urban green spaces in the wake of densification partially undermines the complexity of this infrastructure (Zalar & Pries, Citation2022). Thus, drawing on the notion of plan-ability provides a more complex picture of how high ambitions yet insufficient material operationalisations (as identified by e.g., Lisberg Jensen et al., Citation2023) coexist. The historical attentiveness contributes to the notion of plan-ability by enabling a deeper understanding of the material-historical tensions that may intercept to open or close potential routes for rearranging both planning issues and their material manifestations.

The findings of the paper indicate that the several parallel trajectories for how to plan and engage with outdoor recreational sites partly depend on the organisational set-up of the municipality. As discussed in an earlier section, the responsibility for outdoor recreation is divided within the municipal organisation, creating a structural fragmentation (see also Balikçi et al., Citation2022). What the paper shows is that this fragmentation not only has effect on processual issues of who does what and when but enforces opposing material configurations. This highlights the need for plannig practice to transcend administrative silos, not only for finding a shared analytical understanding of outdoor recreation, but especially for encouraging a discussion on the geographical requirements for a multitude of recreational activities.

The paper discloses the need for scrutiny of the material arrangements of green spaces in the compact city paradigm, going beyond a semantic representation of the positive benefits of green to address the changing patterns of green on the ground (see also Engström & Qviström, Citation2022). To do so, a continued effort to investigate the practices of provision is needed. Especially coupled with attention to how existing landscapes are mobilised and rearranged as a central part of such practices. And, to what versions of green, and outdoor recreation, the practices of provision adhere to, as this might imply drastically different material configurations. To continue probing into the messy integration of outdoor recreation into the compact city, further research would benefit from considering the roles of local political organisations, landowners, and developers in modifying issues and the ordering of land use in the compact city.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers whose comments on earlier versions of this paper contributed to sharpening the argument and research focus. The author would also like to thank Mattias Qviström for his helpful comments throughout the process of writing this paper. Thanks also to Helena Valve and Märit Jansson for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amalia Engström

Amalia Engström holds a PhD landscape architecture, specialising in landscape planning, from the Department of Urban and Rural Development at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala.

References

- Asdal, K. (2015). What is the issue? The transformative capacity of documents. Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory, 16(1), 74–90.

- Asdal, K., & Hobæk, B. (2016). Assembling the whale: Parliaments in the politics of nature. Science as Culture, 25(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2015.1093744

- Asdal, K., & Hobæk, B. (2020). The modified issue: Turning around parliaments, politics as usual and how to extend issue-politics with a little help from max weber. Social Studies of Science, 50(2), 252–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312720902847

- Asdal, K., & Reinertsen, H. (2021). Doing document analysis: A practice-Oriented method. Sage.

- Balikçi, S., Giezen, M., & Arundel, R. (2022). The paradox of planning the compact and green city: Analyzing land-use change in Amsterdam and Brussels. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 65(13), 2387–2411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2021.1971069

- Bergsgard, N. A., Borodulin, K., Fahlen, J., Høyer-Kruse, J., & Iversen, E. B. (2019). National structures for building and managing sport facilities: A comparative analysis of the Nordic countries. Sport in Society, 22(4), 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1389023

- Bibri, S. E., Krogstie, J., & Kärrholm, M. (2020). Compact city planning and development: Emerging practices and strategies for achieving the goals of sustainability. Developments in the Built Environment, 4, 100021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2020.100021

- Bjärstig, T., Thellbro, C., Stjernström, O., Svensson, J., Sandström, C., Sandström, P., & Zachrisson, A. (2018). Between protocol and reality – Swedish municipal comprehensive planning. European Planning Studies, 26(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1365819

- Boulton, C., Dedekorkut-Howes, A., & Byrne, J. (2018). Factors shaping urban greenspace provision: A systematic review of the literature. Landscape and Urban Planning, 178, 82–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.05.029

- Boverket. (2022). Mobilitet för ett aktivt vardagsliv [Mobility for an active everyday life]. https://www.boverket.se/sv/samhallsplanering/stadsutveckling/halsa-forst/aktiv-mobilitet/

- Braae, E. M., Riesto, S., Steiner, H., & Tietjen, A. (2020). Welfare landscapes: Open spaces of Danish social housing estated reconfiguerd. In M. Glendinning & S. Riesto (Eds.), Mass housing of the Scandinavian welfare states: Exploring histories and design strategies (pp. 13–23). University of Edinburgh.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Børrud, E. (2016). How wide is the border? Mapping the border between the city and the urban forest as a zone for outdoor recreation. In K. Jørgensen, M. Clemetsen, K. H. Thorén, & T. Richardson (Eds.), Mainstreaming landscape through the european landscape convention. Rutledge.

- Engström, A., & Qviström, M. (2022). Situating the silence of recreation in transit-oriented development. International Planning Studies, 27(4), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2022.2129598

- European Union. (2022). Special eurobarometer 525 – Sport and physical activity. Country Factsheet Sweden.

- Fahlén, J., & Stenling, C. (2016). Sport policy in Sweden. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(3), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2015.1063530

- Flemsæter, F., Setten, G., & Brown, K. M. (2015). Morality, mobility and citizenship: Legitimising mobile subjectivities in a contested outdoors. Geoforum, 64, 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.017

- Giulianotti, R., Itkonen, H., Nevala, A., & Salmikangas, A.-K. (2019). Sport and civil society in the Nordic region. Sport in Society, 22(4), 540–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1390906

- Gurholt, K. P., & Broch, T. B. (2019). Outdoor life, nature experience, and sports in Norway: Tensions and dilemmas in the preservation and use of urban Forest. Sport in Society, 22(4), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1390938

- Haaland, C., & van den Bosch, C. K. (2015). Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(4), 760–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009

- Haarstad, H., Kjærås, K., Røe, P. G., & Tveiten, K. (2023). Diversifying the compact city: A renewed agenda for geographical research. Dialogues in Human Geography, 13(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221102949

- Hansen, A. S. (2021). Understanding recreational landscapes – A review and discussion. Landscape Research, 46(1), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1833320

- Hautamäki, R. (2019). Contested and constructed greenery in the compact city: A case study of Helsinki city plan 2016. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 14(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2019.1623543

- Hautamäki, R., & Donner, J. (2021). Modern living in a forest – Landscape architecture of Finnish forest suburbs in the 1940s–1960s. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 104(3), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.1989320

- Hedenborg, S., Fredman, P., Hansen, A. S., & Wolf-Watz, D. (2022). Outdoorification of sports and recreation: A leisure transformation under the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. Annals of Leisure Research, 27(1), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2022.2101497

- Heinen, E., van Wee, B., & Maat, K. (2010). Commuting by bicycle: An overview of the literature. Transport Reviews, 30(1), 59–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640903187001

- Hegetschweiler, K. T., de Vries, S., Arnberger, A., Bell, S., Brennan, M., Siter, N., Olafsson, A. S., Voigt, A., & Hunziker, M. (2017). Linking demand and supply factors in identifying cultural ecosystem services of urban green infrastructures: A review of European studies. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 21, 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2016.11.002

- Hislop, M., Scott, A. J., & Corbett, A. (2019). What does good green infrastructure planning policy look like? Developing and testing a policy assessment tool within Central Scotland UK. Planning Theory & Practice, 20(5), 633–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1678667

- Idrottsutredningen. (1969). Idrott åt alla: betänkande [Sport for all: Report]. SOU, 1969, 29.

- Jansson, M. (2014). Green space in compact cities: The benefits and values of ecosystem services in planning. The Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, 26(2), 139–160.

- Jansson, M., & Schneider, J. (2023). The welfare landscape and densification – Residents’ relations to local outdoor environments affected by infill development. Land, 12(11), 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112021

- Kain, J.-H., Adelfio, M., Stenberg, J., & Thuvander, L. (2022). Towards a systemic understanding of compact city qualities. Journal of Urban Design, 27(1), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2021.1941825

- Kärrholm, M., & Wirdelöv, J. (2019). The neighbourhood in pieces: The fragmentation of local public space in a Swedish housing area. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(5), 870–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12735

- Kjærås, K. (2021). Towards a relational conception of the compact city. Urban Studies, 58(6), 1176–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020907281

- Komossa, F., van der Zanden, E. H., & Verburg, P. H. (2019). Characterizing outdoor recreation user groups: A typology of peri-urban recreationists in the Kromme Rijn area, The Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 80, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.017

- Lehto, C., Hedblom, M., Öckinger, E., & Ranius, T. (2022). Landscape usage by recreationists is shaped by availability: Insights from a national PPGIS survey in Sweden. Landscape and Urban Planning, 227, 104519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104519

- Lennon, M. (2021). Green space and the compact city: Planning issues for a ‘new normal’. Cities & Health, 5(sup1), S212–S215. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1778843

- Li, T. (2007). Practices of assemblage and community forest management. Economy and Society, 36(2), 263–293.

- Lindholst, A. C., Caspersen, O. H., & van den Bosch, C. C. K. (2015). Methods for mapping recreational and social values in urban green spaces in the Nordic countries and their comparative merits for urban planning. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 12, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2015.11.007

- Lisberg Jensen, E., Alkan Olsson, J., & Malmqvist, E. (2023). Growing inwards: Densification and ecosystem services in comprehensive plans from three municipalities in Southern Sweden. Sustainability, 15(13), 9928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139928

- Mehaffy, M. W., & Haas, T. (2020). New urbanism in the new urban agenda: Threads of an unfinished reformation. Urban Planning, 5(4), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i4.3371

- Metzger, J., & Wiberg, S. (2017). Contested framings of urban qualities: Dis/qualifications of value in urban development controversies. Urban Studies, 55(10), 2300–2316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017712831

- Miljödepartementet. (2017). Government communication 2017/18:230 Strategi för Levande städer – politik för en hållbar stadsutveckling [Strategy for living cities – Politics for a sustainable urban development].

- Pérez, F. (2020). ‘The miracle of density’: The socio‐material epistemics of urban densification. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 617–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12874

- Petersson-Forsberg, L. (2014). Swedish spatial planning: A blunt instrument for the protection of outdoor recreation. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 5–6, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2014.03.003

- Pries, J., & Qviström, M. (2021). The patchwork planning of a welfare landscape: Reappraising the role of leisure planning in the Swedish welfare state. Planning Perspectives, 36(5), 923–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2020.1867884

- Qviström, M., Bengtsson, J., & Vicenzotti, V. (2016). Part-time amenity migrants: Revealing the importance of second homes for senior residents in a transit-oriented development. Land Use Policy, 56, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.001

- Rannila, P. (2021). Relationality of the law: On the legal collisions in the Finnish planning and land use practices. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18785443

- Region Stockholm. (2018). RUFS 2050: regional utvecklingsplan för stockholmsregionen: Europas mest attraktiva storstadsregion. [RUFS 2050: Regional development plan for the Stockholm region: Europe’s most attractive metropolitan region].

- Russo, A., & Cirella, G. T. (2018). Modern compact cities: How much greenery do we need? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102180

- Sallis, J. F., Cerin, E., Conway, T. L., Adams, M. A., Frank, L. D., Pratt, M., Salvo, D., Schipperijn, J., Smith, G., Cain, K. L., Davey, R., Kerr, J., Lai, P.-C., Mitáš, J., Reis, R., Sarmiento, O. L., Schofield, G., Troelsen, J., Van Dyck, D., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., & Owen, N. (2016). Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet (London, England), 387(10034), 2207–2217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2

- Salmaso, E. (2020). Skateparken står fortfarande stilla – över ett år senare [The skate park is at a standstill – over one year later] mitt i Upplands Väsby. https://www.mitti.se/nyheter/skateparken-star-fortfarande-stilla-over-ett-ar-senare/lmtbs!8000569/

- Schmitt, P., & Smas, L. (2019). Shifting political conditions for spatial planning in the Nordic countries In. A. Eraydin & K. Frey (Eds.), Politics and conflict in governance and planning: Theory and practice (pp. 133–150). Routledge.

- Schmitt, P., & Smas, L. (2020). Dissolution rather than consolidation – Questioning the existence of the comprehensive-Integrative planning model. Planning Practice & Research, 38(5), 678–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2020.1841973

- Setten, G., Stenseke, M., & Moen, J. (2012). Ecosystem services and landscape management: Three challenges and one plea. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 8(4), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2012.722127

- SFS. 1998:808. Environmental Code [Miljöbalk].

- SFS. 2010:900. Planning and Building Act [Plan- och bygglag].

- Sharifi, A. (2016). From garden city to eco-urbanism: The quest for sustainable neighborhood development. Sustainable Cities and Society, 20, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2015.09.002

- Stenseke, M., & Hansen, A. S. (2014). From rhetoric to knowledge based actions – Challenges for outdoor recreation management in Sweden. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 7-8, 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2014.09.004

- ten Brink, P., Mutafoglu, K., Schweitzer, J.-P., Kettunen, M., Twigger-Ross, C., Baker, J., Kuipers, Y., Emonts, M., Tyrväinen, L., & Hujala, T. (2016). The health and social benefits of nature and biodiversity protection. A report for the European commission (ENV. B. 3/ETU/2014/0039). Institute for European Environmental Policy.

- Tunström, M. (2007). The vital city: constructions and meanings in the contemporary Swedish planning discourse. Town Planning Review, 78(6), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.78.6.2

- Tzoulas, K., Korpela, K., Venn, S., Yli-Pelkonen, V., Kaźmierczak, A., Niemela, J., & James, P. (2007). Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using green infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.02.001

- Upplands Väsby Kommun. (2016). Utvecklingsplan för ekosystemtjänster i Upplands Väsby Kommun [Development plan for ecosystem services in Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (1976). Fritidsplan 1976–1980 [Leisure plan 1976–1980].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2005). Framtidens Upplands Väsby – ”Den moderna småstaden”. Strategisk kommunplan 2005–2020 [Future Upplands Väsby – “The modern small town”. Strategical municipal plan 2005-2020].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2008). Vilundaparken planprogram. Samrådshandling [Vilundaparken planning programme, consultation document].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2013). Stadsmässighet – definition för Upplands Väsby kommun [Urban Qualities – Definition for Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2017). Detaljplan för Järnvägsparken [Detailed development plan for The Railway Park].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2018a). Detaljplan för Östra Runby med Väsby stationsområde [Detailed development plan for East Rundby with Väsby station area].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2018b). Investeringsanmälan – Skatepark Smedby KS/2018:332 [Investment notification – Skate park Smedby]

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2018c). Stadsmässighetsdefinition för Upplands Väsby kommun [Definition of Urban qualities for Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2018d). Väsby Idrottsstad, Vilundaparken, Förslag till planprogram [Väsby sport city, Vilundaparken. Proposal for planning programme].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2018e). Väsby Stad 2040. Ny översiktsplan för Upplands Väsby kommun [Väsby City 2040. New comprehensive plan for Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2019a). Aktiv hela livet – Idrottsstrategisk plan för Upplands Väsby kommun [Active through life – Sports strategy for Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2019b). Förslag på placering av skatepark i Vilundaparken KFN/2017:1 [Proposal for localisation of skate park in Vilundaparken]

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2019c). Sammanträdesprotokoll kultur- och fritidsnämnden 2019-06-18 [Minutes, culture and leisure committee 2019-06-18].

- Upplands Väsby kommun. (2022). Vilunda fotbollshall har öppnat [Vilunda football hall has opened]. https://www.upplandsvasby.se/arkiv/nyheter/2022-04-01-vilunda-fotbollshall-har-oppnat.html

- Upplands Väsby kommun & Ekologigruppen. (2016). Utvecklingsplan för ekosystemtjänster i Upplands Väsby Kommun [Development plan for ecosystem services in Upplands Väsby municipality].

- Valve, H., Åkerman, M., & Kaljonen, M. (2013). ‘You only start filling in the boxes’: Natural resource management and the politics of plan-ability. Environment and Planning A, 45(9), 2084–2099.

- Valve, H., Kaljonen, M., Kauppila, P., & Kauppila, J. (2017). Power and the material arrangements of a river basin management plan: The case of the archipelago sea. European Planning Studies, 25(9), 1615–1632. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1308470

- Valve, H., Lazarevic, D., & Pitzén, S. (2022). The co-evolution of policy realities and environmental liabilities: Analysing the ontological work of policy documents. Geoforum, 128, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.12.005

- Valzania, G. (2022). Towers once in the park: Uprooting Toronto’s welfare landscapes. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 104(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2022.2032256

- Zalar, A., & Pries, J. (2022). Unmapping green space: Discursive dispossession of the right to green space by a compact city planning epistemology. City, 26(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2021.2018860

- Zhou, C., Zhang, Y., Fu, L., Xue, Y., & Wang, Z. (2021). Assessing mini-park installation priority for regreening planning in densely populated cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 67, 102716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102716