ABSTRACT

The interspecies interactions between farmers and livestock have provided an important conceptual and empirical focus in expanding our understanding of animal geographies, with a burgeoning literature exploring the intricate material and discursive (re)positioning of animals across different socio-spatial contexts. This paper offers a new direction for understanding these human-animal encounters by exploring the ways in which farmer and animal identities are mediated by social media. By drawing on a qualitative analysis of UK farmers’ tweets about their livestock and semi-structured interviews about farmers’ use of social media, this paper examines how social media allows a reworking of the spatiotemporalities of animal-human relations and offers farmers the opportunity to co-construct their identities with their livestock and farming practices. The paper identifies three ways in which farmer–livestock relations are mediated by social media. Firstly, that animals are made visible as actors within farming cultures to those beyond the farm gate. Secondly, that the role of farm animals as subjects and objects is negotiated throughout temporal moments online and thirdly that representations on social media of interactions with animals plays a role in the (re)construction of farmers’ identities.

Resumen

Las interacciones entre especies entre ganaderos y ganado hanproporcionado un importante enfoque conceptual y empírico paraampliar nuestra comprensión de las geografías animales, con unaliteratura floreciente que explora el intrincado (re)posicionamientomaterial y discursivo de los animales en diferentes contextossocioespaciales. Este artículo ofrece una nueva dirección paracomprender estos encuentros entre humanos y animales al explorar lasformas en que las identidades de los ganaderos y los animales estánmediadas por las redes sociales. Basándose en un análisiscualitativo de los tweets de los agricultores del Reino Unido sobresu ganado y en entrevistas semiestructuradas sobre el uso de lasredes sociales por parte de los ganaderos, este artículo examinacómo las redes sociales permiten una reelaboración de lasespacio-temporalidades de las relaciones entre animales y humanos, yofrece a los ganaderos la oportunidad de co-construir sus identidadescon sus prácticas ganaderas y agrícolas. El artículo identificatres formas en que las relaciones entre agricultores y ganaderosestán mediadas por las redes sociales. En primer lugar, que losanimales se hagan visibles como actores dentro de las culturasagrícolas para quienes están más allá de las puertas de lagranja. En segundo lugar, que el papel de los animales de granja comosujetos y objetos se negocia a lo largo de momentos temporales enlínea y, en tercer lugar, que las representaciones en las redessociales de las interacciones con los animales desempeñan un papelen la (re)construcción de las identidades de los ganaderos.

Résumé

Les interactions entre les fermiers et leurs animaux ont offert unefocalisation empirique et conceptuelle importante pourl’élargissement de nos connaissances en géographie animale, avecun nouveau courant de recherche qui étudie le (re)positionnementdiscursif et matériel complexe des bêtes au travers decontextes sociospatiaux différents.Cet article offre une direction nouvelle pour comprendre cesrencontres entre humains et animaux, avec une explorationdes représentations médiatiséesde leursidentités respectives dans lesréseaux sociaux. En s’appuyant sur une analyse qualitative detweets de fermiers britanniques concernant leur bétail etd’entretiens semi-structurés sur l’utilisation des réseauxsociaux par les exploitants agricoles, cet article étudiecomment cesmédias permettentune réécriture sur des plans temporels et spatiaux dans lesrelations entre les animaux et les humains et offrent auxagriculteurs l’occasion de coconstruire leursidentités avec leurs pratiques agricoles et bétaillères. L’articledécouvre que les relations entre les agriculteurs et leurs bêtessont médiatisées par les réseaux sociaux de trois manières : enpremier, les animaux sont rendus visibles en qualité d’acteurs ausein des cultures agricoles pour toutes les personnes en-dehorsdeslimites de la ferme. Ensuite,le rôle des animaux en tant que sujets et objets est négocié parle biais de moments temporels en ligne. Finalement, lesreprésentations des interactionsavec les animaux sur les réseauxsociaux jouent unrôle dans la (re)construction des identités des fermiers.

Introduction

In recent years, the interspecies interactions between farmers and livestock have provided an important conceptual and empirical focus in expanding our understanding of animal geographies, with a burgeoning literature exploring the intricate material and discursive (re)positioning of animals across different socio-spatial contexts. This work has considered how animals might become materially and discursively (re)positioned in light of changing structural conditions and emerging technologies, and the moral ambiguities faced within human-livestock relations (Convery et al., Citation2005; Holloway & Morris, Citation2014; Yarwood & Evans, Citation2006). Drawing on data from the qualitative analysis of social media posts and semi-structured interviews, this study offers a new direction for understanding human-animal encounters by exploring the ways in which farmer-animal identities are mediated by social media. Social media, we suggest, enables the spatio-temporalities of farming lives, and human-livestock relations, to be expanded, offering the ability to connect, through posts and online interactions, to others who are geographically distanced, and at any time of the day or night (Treem & Leonardi, Citation2013). The paper examines the nature of farmers’ depictions of animals on X (the platform formerly known as Twitter) and their narratives around these posts, and in doing so contributes to the broader geographical scholarship around the ‘digital turn’ (Ash et al., Citation2018). It does this by adding animals to the discussion of the multifarious ways that virtual spaces (re)produce socio-spatial relations and how social media can be utilized in the (re)presentation of, and reflection upon, human-animal relations.Footnote1

The need to attend to the online and virtual spaces of animals has been noted by Holloway and Morris (Citation2014), who suggest that traditional spaces for evaluating livestock – such as auctions, agricultural shows, or breed society handbooks – may be supplanted by online spaces. In contrast to these more decontextualized off-farm settings, the paper sees how social media posts capture animals in their more everyday contexts. Drawing on an analysis of farmers’ posts on X, alongside in-depth interview with farmers using social media, the paper offers fresh insight into the rhythms and relationships of working with farm animals and how such online technologies ‘increasingly produce or mediate spatio-temporalities in their complex entanglements in everyday life’ (Lynch & Farrokhi, Citation2022). First, we consider the ways in which depictions of animals are narrated and styled on social media, to give animals a voice and/or include them as part of an ongoing storyline. Following this, we examine how the boundaries of the commodification of livestock are troubled, and reworked, in X posts. Finally, this work is brought together in exploring the ways that animals can help (co)construct farming identities.

Livestock–farmer relations

Farmer–livestock relations have been a fruitful ground for considering animal geographies, with considerable attention paid to how animals are (re)constructed within networks of farming practice (Holloway, Citation2007; Miele, Citation2016) and the socio-affective relations between humans and livestock (Wilkie, Citation2005). This research has increasingly focused on the material and emotional spaces that humans and livestock share. At a broad geographical scale, work has investigated how livestock may play a role in regional identity and place-making (Yarwood & Evans, Citation2006). At the scale of the farm, allied work has noted how farmers’ interaction with livestock may be identity-enhancing (Convery et al., Citation2005), with specific attention paid to how livestock are an embodiment of hard work (Burton et al., Citation2021). Here, the Bourdieusian-inspired work on the ‘good farmer’ (. Burton et al., Citation2021) has been deployed, which recognizes the different forms of capital (economic, social and cultural) and how farmers seek to accrue, display, and exchange capital in achieving good farmer status within the ‘rules of the game’ (Bourdieu, Citation1990) of farming. Within this framing, livestock represent not only economic capital but social and cultural capital as they embody good decision-making and stockpersonship (Yarwood & Evans, Citation2006). As Burton et al. (Citation2008) note, good farmer status relies on the outward display of symbols and performance of good farming – which for animals might include the aforememntioned agricultural shows or auctions – and that these can be interpreted by the intended audience.

Arising in farmer–livestock discussions are the often complex and ambiguous relationships that exist, with Holloway’s (Citation2001) discussion of hobby farming, for example, exploring the ethical ambiguities as animals are socially constructed simultaneously as ‘livestock’ and ‘pet’, within discourses of care, ethical relations, and food production. Convery et al. (Citation2005) and Wilkie (Citation2005) note that similar moral geographies and ambiguities may exist within more commercial agriculture. Using concepts of ‘decommodification’ and ‘recommodification’, Wilkie (Citation2005) examines how animals’ status as ‘commodity’ is fluid, noting how farmers may build up individual and personalized relationships (and animals demonstrate their individual subjectivities) within which animals become decommodified and then recommodified at the point of sale or slaughter. In noting the multifarious nature of these relations, Wilkie (Citation2005) refers to four categories of interaction between farmers and livestock: detached detachment (animals seen as commodities without individuality), concerned detachment (seen as sentient commodities but lacking individuality), concerned attachment (in which processes of decommodification and recommodification coexist and animals may be seen as individuals whilst remaining commodities at different points in time) and attached attachment (wherein animals become individualized, and not recommodified, within meaningful animal-human relationships).

Convery et al. (Citation2005) focus on the 2001 UK foot and mouth epidemic and used the idea of ‘emotional geographies’ to understand the seemingly contradictory position of seeing livestock as both ‘friends’ and ‘sources of food’, noting the moral challenge of death via culling considered to be in the wrong place (outside the abattoir) and at the wrong time (outside the normal pattern of selling animals when they are ready to enter the food chain or have reached the end of their ‘productive’ lives). Ellis (Citation2016, p. 111), considering contemporary beef production, refers to this as ‘boundary work’, which creates ‘the social and emotional space needed for modern beef production and consumption’. They note the processes ranchers undertake which enable them to understand their emotions in ways that do not disrupt the production process, specifically: their sense of responsibility to animals as well as consumers; religious-centred beliefs of dominion, which offers a moral justification of humans’ hierarchical exploitation of animals; and faith in the cycle of production, wherein they see the whole cycle of animals’ lives. Significant, here is animal agency, where work has noted how, especially for farmed animals, animals’ ‘lives unfold according to fixed genetic or species-specific scripts, rather than as complex subjects who act with intention and purpose, both individually and collectively’ (Blattner et al., Citation2020, p.1). Work in this area has noted how animals may elide human placings through acts of resistance (or the ‘consequential doings of animals’ (Chao, Citation2023)), and how agency is relationally achieved out of the interactions between heterogeneous materials which may vary across space and time.

Taken together, this work highlights the conceptual importance of considering animals as ‘quintessential hybrids’ (Buller & Morris, Citation2003, p. 217) – that is, they are (co)produced with farmers, farming technologies and materials spaces, which in turn may be (re)shaped by broader policies, market changes and regulatory frameworks. As Miele (Citation2016, p. 60) suggests, ‘animals do not pre-exist the network that brings them into being’ and are co-constituted within farming practices and networks. Recognising this involves moving beyond an essentialist framing of animals and animal subjectivities, and whilst humans may seek to position animals – discursively and materially – animals’ unruliness may often elide these classifications and positionings (Donald, Citation2019).

Social media, animals, and online engagement

Geographers are increasingly paying attention to the ways that digital technologies, and social media in particular, transform socio-spatial relations and augment the production of space (Ash et al. Citation2018; Liu, Citation2022), noting how these technologies may encourage new social and cultural practices and discourses and (re)produce spatio-temporalities as they are intricately entangled within everyday life (Lynch & Farrokhi, Citation2022). Work in this area has examined the ‘digital mundane’, where the networked practices of everyday routines and activities are explored, noting how technologies such as social media have affective potential (Leszczynski, Citation2019). Ensuing work has noted the styles and performances of the online presentation of the self, and the potential politics around this (Holton et al., Citation2023; Liu, Citation2022). Underpinning this, social media scholars have noted, are the multiple affordances of such technologies, including: visibility (where knowledge, activities and behaviours which may be previously unseen, are made visible), persistence (as content endures after posting), editability (where posts may be changed after position) and association (the ability to connect with other content and users through processes such as tagging) (Frison & Eggermont, Citation2015).

This affective potential of social media is seen in those previous studies examining the accounts of animals in videos, photographs and texts online (Berland, Citation2019). Examples include social media curated on behalf of pets, within which human owners represented them in a way that highlights their individual characters, behaviours and activities similar to the human influencer (Maddox, Citation2020; Ngai, Citation2022). Jacobson et al. (Citation2022) liken animals’ portrayal on social media accounts of pets as similar to the anthropomorphizing previously seen when animals are used in traditional advertising, with positioning from the animal’s voice portraying emotion, similarly to Ngai’s (Citation2022, p. 6) assertion that ‘human and nonhuman subjects co-habited social media as affective communities’. Photographs are often central to this process. As Berger (Citation2013, p.18) notes ‘photographs bear witness to a human choice being exercised in a given situation. A photograph is a result of the photographer’s decision that it is worth recording that this particular event or this particular object has been seen’. As such they stand as both are a mix of presentation, representation (or ‘quotation from reality’ (Berger, Citation2013)) and performance, and in the context of social media ‘practices and process of making and posting photos are entangled with people’s imaginations and perceptions of places, on the basis of their social and cultural identities [and are] reframed by the visual and textual contents on social media platforms’ (Liu, Citation2022, p. 178). In contrast to pets, the representation of farm animals on social media has received less attention and presents an opportunity to investigate the nuanced ways that animals who are not typically defined as companions are (re)presented and spoken about and how this can problematize their positioning as a subject and/or object.

In focusing on human-horse blogs, as a forerunner to social media, Schuurman (Citation2014) argues that online posts may be a presentation of the owner’s self, with posts about animals being well cared for serving to reinforce an identity as a responsible owner. They argue that charting human-animal relations over time – including their conflicts and transformations with their horses – shows this trajectory as an active and mutual process, and the commentary they provide shows how those closes to animals are able to interpret their embodied communications (Schuurman, Citation2014). As Ngai (Citation2022) agree in their discussion of pets, subjectivity is socially mediated through multiple others, including nonhumans.

In contrast to pets, the representation of farm animals on social media has received less attention and presents an opportunity to investigate the nuanced ways that animals who are not typically defined as companions are spoken about and how this can problematize their positioning as a subject and/or object. An exception is Linné (Citation2016) consideration of social media marketing campaigns in the Swedish dairy industry which sees how romantic and idyllic representations of the production process – which depict happy cows as willing producers of milk – are capitalized on. In contrast to these encounters imagined on behalf of brands, Riley and Robertson (Citation2021) acknowledge that social media facilitates the ‘working out loud’ practices of farmers as they communicate parts of their working lives that are usually unseen. McLoughlin and Casey (Citation2022, p. 38) outline how this may include farmer’s views of animals as their visual memoir draws on the fact that ‘auto-photography renders visible so-called hidden relations and socialities’ such as the contradictions in mediating the life and death of cattle. Following the literature around animals in digital culture, it is expected that pets are brought into conversation through the intimacy of the household and their construction as individuals imbued with personhood (Charles, Citation2014). However, this study extends this body of work to explore the ways in which farm animals are brought into proximity and visibility by social media in ways that are not always possible as part of a private farm workspace.

Methods

The paper draws on the qualitative analysis of 5000 tweets and semi-structured interviews with 22 farmers who use social media and are based in the UK. Whilst, by its nature, social media moves beyond geographical boundaries, we decided to focus specifically on the UK in order to pick up on broadly similar agricultural structures (in terms of policy and legal contexts as they relate to livestock farming), which might not be possible if working across multiple countries. The discourse analysis of tweets provides an insight into the scope of narratives about farming lives communicated by farmers on social media, and the thematic analysis of interviews supplement these by exploring the ways that farmers use social media and how these uses (re)shape, transmit and extend pre-existing notions of farming identities. From the data, it emerged that interactions with animals are important for farmers’ presentation of their work and identities to the wider public and that this sits within a wider context of a political landscape fraught with concerns for animal welfare and the sustainability of animal agriculture.

Besides analysis of the written corpus of the tweets, the meaning of attached photographs and videos allowed us to examine representations of animals by those who interact with them on a daily basis. This research contributes to that burgeoning work ‘narrating the complex and entangled lives of animals and their human keepers’ (Hamilton & Taylor, Citation2017, p. 177). As Hamilton and Taylor (Citation2017) recognize in their case for ethnography after humanism, the agency of animals is not part of the research process, but their inclusion from the perspective of farmers tells us about the ways in which human-animal relationships are socially constructed. Multi-species methodologies can incorporate visual data (Hamilton & Taylor, Citation2017) and here we extend this to online spaces by examining everyday encounters between farmers and their stock as depicted on social media. Despite the researchers not sharing space with animals as a traditional (non-virtual) ethnography would imply, the examination of social media data accounts for the performance of interactions with livestock in the public domain.

The tweets were selected through snowball sampling by building a network of farmers from each tweet identified. The three phased sample firstly consisted of a X (Twitter) search using the hashtag #farm24 as a ‘topical marker’ (Einspänner et al., Citation2014, p. 100).Footnote2 This was chosen as a search term to identify farmers who tweet, given that Wang and Wei (Citation2020, p. 4) acknowledge that ‘the use of hashtags on X is not only a tool to bookmark the content but also a symbol signalling the membership of a community’. As it is possible for any user to engage with farming hashtags, the X accounts of farmers could be discerned from X bios. Given that the X API restricts searches to display tweets of up to a week old, 49 tweets were shown from a search of #farm24 which consisted of seven unique farm/ers.

The most recent 100 tweets from each of the seven farmers were imported into Nvivo (Citation2020) to form the first phase of the sample. The second phase of the sample entailed selecting four followers of each of the initial farmers identified, repeating this process for a third stage until 50 farmers were sampled. The selection was based on the content of tweets as related to farming life and was dependent on public access (cf. Sergi & Bonneau, Citation2016). Therefore, theoretical sampling, similarly utilized by Schneider (Citation2016) in their study of X discourses, shaped the selection of farmer users through the variation of symbols about farming identities presented. The extension of the sample beyond hashtags aimed to reduce the bias of individuals who engage in tagging practices who are often those wishing to contribute to debate (Marwick & Boyd, Citation2011) or the politics of specific hashtags, such as #farm24.

The recruitment of interview participants was, similarly to the tweets, through chain referral sampling (Heckathorn, Citation2002). Firstly, farmers from the X analysis were invited to participate and, from their followers, any users who indicated a farmer identity in their bio, as well as those running YouTube channels with farming embedded in their content, were contacted. The semi-structured interviews were conducted on the telephone or via video call and lasted from half an hour to two hours. The topics discussed included history of social media use, preferred practices, and depictions of farming lives. These questions were broad enough to inductively discern that work with livestock was entangled with how they viewed their identities and their decisions regarding aspects of their work to share or omit online. A thematic analysis of both sets of data revealed that a form of ‘working out loud’ on social media (Sergi & Bonneau, Citation2016) that a typology of generic professions ignores is human-animal relations; the focus of this paper.

A multimodal discourse analysis of tweets, comprising textual and visual data, was conducted by initially using the ‘working out loud’ typology of Sergi and Bonneau (Citation2016) which characterizes the practices of tweets for narrating work. However, a gap was observed in this typology which resulted in the development of new codes from the data. For example, the initial theme of interaction with animals included codes such as caring for animals, knowing animals and expressing through animals on which this paper is based. The nuances of a farming context in comparison to Sergi and Bonneau’s (Citation2016, p. 384) focus on ‘any organisation and professional field’ is shown by tweets which ‘express’ the feelings of animals with whom farmers work rather than their own.

Akin to the approach taken by McCrow-Young (Citation2021) in their analysis of Instagram data, although the tweets are publicly available, steps have been taken to maintain the anonymity of those tweeting. In response to ongoing debates about the privacy of social media data raised by the likes of Townsend and Wallace (Citation2016), distinguishing characteristics from photographs and videos, as well as times and dates of tweets have been masked. Furthermore, the tweets have been paraphrased – maintaining the sentiment and themes of the tweet but changing specific wordings – in order that these are not searchable through search engines. The original tweets in the farmer’s own words were analysed and it is only for the purposes of presenting the data in this report that paraphrasing is used to mitigate identification of the farm/ers.

Bringing animals out of the shadows

Our analysis found that the multimedia of tweets, typically the combination of text and photos, is stylized by farmers to reinforce the ways in which farm animals are positioned. Unlike representations of animals in popular culture that are imagined, tweets are farmer-generated depictions of the multispecies interactions that they have experienced. Whilst farmers come to know animals through ‘encountering them as animal subjects’ (Holloway & Morris, Citation2014, p. 1), Turnbull et al. (Citation2020, p. 6) note that social media representations are different to the live experiences of seeing and hearing them in person or via zoom calls which serve to ‘generate real-time, more-than-human affects’. As such, tweets rely on commentary and stylization to contextualize them based on relationships shared between farmers and their individual animals, as well as cultural knowledge and expectations which govern breed standards and good stockpersonship whereby an animal’s, and indeed a farmer’s, quality is judged by the animal’s appearance (Holloway & Morris, Citation2014). Farmers noted in the interviews that the audience of their tweets comprises both farming communities and the wider public and our analysis revealed how farmers aim to render photographs meaningful through their accompanying text explanations – or what Riley and Robertson (Citation2022) refer to as didactics. In what follows we uncover the ways that farmers curate tweets about animals, namely by showing individual faces, comedic performances, talking from the animal’s perspective, and archiving beyond embodied interactions with animals.

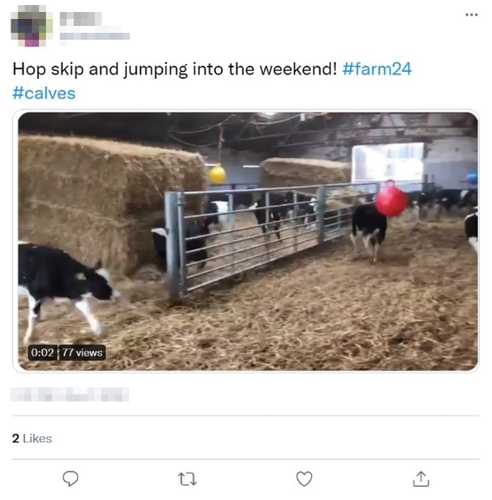

, showing a calf apparently sleeping in a drinking trough, and much like a human relaxing in an armchair, serves as a useful entrée to many of the themes that emerged from our analysis. At one level, the picture offers an appreciation of animal agency and ‘their wilfulness to resist human structures’ (Donald, Citation2019, p. 471) and, at a second and interrelated level, it also exposes the emotional geographies – depicting them as potentially mischievous, playful and, most significantly, happy. In terms of their positioning, the visibility on social media meant that animals can be shown beyond their usual sites of spectacle – such as agricultural shows or the auction market (Burton et al., Citation2021) – and instead be seen in their everyday spaces of the farm. Farmers’ tweets about animals often included a humorous element due to the novelty of something being out of place, in contrast to the normative behaviours encouraged in public settings where rosettes or sales are at stake. For example, the tweet in is framed as a ‘documentary’ which acknowledges the natural setting in which the calf is found without preparation.

Previous geographical work has noted the recent (re)positioning of animals as spectacles of consumption, rather than simply units of production, on farm parks (Evans & Yarwood, Citation1998) and social media can be seen as both an extension of, and departure from, this. The affordances of visibility and persistence allowed animals to be framed on social media as consisting of more than just their productive qualities, towards revealing more of their individual agency and characteristics. The two following extracts illustrate some of the intentions of farmers in posting details of their animals on social media:

It’s good to be able to show people the animals so they can see that are looked after well and not ill-used … and can see the stuff that they get up to (Farmer 10)

Farmers get a bad press, so it’s good to show happy cows, and to get a few likes and positive comments on them (Farmer 4)

The reference to showing how the animals are ‘well looked after’ was the most common theme amongst interviewees. As will be returned to later in the paper, displays of good stockpersonship are an integral aspect of the professional identity of farming, but the presentations of pictures of animals moved beyond showing their physical qualities towards demonstrating their agency and emotions. Both interview extracts show how animals are ascribed emotions such as contented, chilled () or happy () – which can be seen as a discursive strategy wherein they are positioned as willing accomplices in production (cf. Linné, Citation2016), rather than being exploited or, in the words of Farmer 10, ‘ill-used’. As Farmer 4 hints at, this process moved beyond just the display of these pictures towards what Shifman (Citation2013) refers to as ‘emotional arousal’, whereby pictures are purposefully curated to stimulate compassion, from others, towards these animals. The use of the associated caption, as Berger (Citation2013) notes, works to enhance the power of the photograph. Whilst for several farmers this was aimed at their individual case, for others, such as Farmer 4, this was part of a wider strategy whereby animals were used to counter the negativity around animal welfare and the wider industry and where the negative press around industrialized agriculture could be challenged.

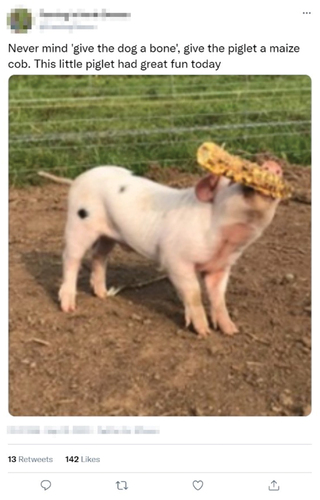

Another way in which tweets about animals are stylized is by talking from the perspective of animals. The horse’s thoughts () are reported in first person, meaning that the farmer can reflect on their own good practice by showing that they recognize the perspective of animals and can interpret their behaviours (Kaarlenkaski, Citation2014). As Wilbur and Gibbs (Citation2020, p. 268) argue, writing from the perspective of the animal can facilitate ‘de-centring the human as primary agent’, and our analysis demonstrated that farmers often used the animal’s viewpoint as what Beierl (Citation2008, p.215) refers to as ‘rhetoric strategy’ in order to ‘engender empathy in the reader, to consider how it would feel like to be an animal’. Whilst it has been noted by Berger (Citation2013) that animals have become exoticized and remote as a result of capitalism, speaking for animals within these tweets offers a level of ‘interspecies intimacy’ (Linné, Citation2016) as it constructs their status as subjective beings.

Interlaced with this speaking for animals is the way that photos may contribute towards what is called the ‘cute economy’ (Maddox, Citation2020). In discussing their posts on social media, Farmers 3 and 14 made both implicit and explicit reference to this:

People seem to always like a picture a cow chewing the cud, or a wide-eyed cute calf […] I’ll often put something up like that, nobody wants to see a grizzly old tup, or a lame cow” (Farmer 3)

I got a lot of views and comments on a video of all the lambs running and skipping in the field (Farmer 14)

Holloway and Morris (Citation2014, p. 3) recognize the ‘complex interplay and relationship between these animals’ functionality and aesthetic appeal’, and such a tension is revealed in the extracts from farmers which highlight a recognition of what might be popular with their audience and a preference towards these cute displays rather than the harder realities of working with animals, such as illness, which may be open to misinterpretation. Lorimer (Citation2007, p.918) recognizes that animals have varying degrees of ‘nonhuman charisma’ which refers to ‘characteristics of a species’ appearance and behaviour, which trigger strong emotional responses’. The extracts from Farmers 3 and 14 show an awareness of this, not only with the child-like characteristics of skipping lambs used to appeal to, and trigger, emotional responses from their followers, but also capturing particular activities that they undertake. For Farmer 3, the pictures and videos of a cow chewing its cud might offer ‘calmness, tranquillity, and country life, symbolically opposed to industrialization, urbanization, and the mass production of food’ (Linné, Citation2016, p. 720). Following this, echoes the observations of Farmer 14, with a video presented showing happy calves ‘skipping and jumping’. The literature on social media has noted how the digital practice of ‘baby spam’ has been extended to showing animals, online, as ‘fur babies’ (Maddox, Citation2020) and our observations, here, suggest that it too can be extended to livestock – showing their aesthetic qualities and charisma and, as turned to later in the paper, how this can enhance the identities of farmers themselves.

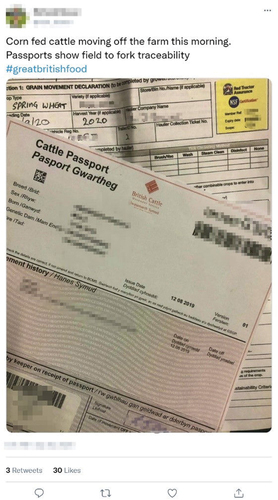

The analysis also revealed how tweets can move beyond the specific and lively interactions with animals towards producing a digital afterlife of human-animal relations by being curated as an archive. Human-livestock interactions on farms may be short-lived – as animals are sold or culled – but the durability of X allows animal engagements to be temporally extended. In , a cattle passport is offered as a material trace of the animal as it moves beyond the affective space (the farm) and into the food system (the fork). The animal is presented not as their material, fleshy and lively self, but through the proxy of paperwork. Here, attention is focused less on appealing to the emotional responses of the audience, but towards the wider positions of animals in the farming system, using them to inform an online audience about the nature of the farming industry and, more specifically, as a way of speaking about the qualities and characteristics of the farmer themselves. It is it to these two themes the paper now turns.

Troubling the commodification boundary

Work on livestock has considered how, through spaces such as the farm, the auction market, or the slaughter house, animals (de/re)commodified status shifts over their lifecourse (Gillespie, Citation2020). gives an example of these ambiguous (de/re)commodifying relations and how the affordances of social media might offer particular insight into the intricacies of these farmer–animal relations. At one level, the tweet can be read as another example of the deindividualizing of farm animals, wherein the use of ‘first batch’ of lambs positions them as a collective or reduced to numbers and the depiction of eating stubble turnips – a high energy crop commonly used to fatten lambs for slaughter – as an integral part of the development of this commodity. At another level, though, the ability of the farmer to note the ‘enjoyment’ of the animals as well as their own pleasure in seeing (and depicting) this, speak both to the simultaneous ‘moral ambiguity’ (Holloway, Citation2001) that farmers may feel, and also gives an insight into how the recommodification process may take place beyond the more public spaces such as the auction market. Whilst this latter space has been observed as one where the process of recommodification is complete – as the animal becomes reduced to its sale price, weight, or commodified characteristics - Riley (Citation2011) has highlighted how this is part of a broader process, which involves not only the material preparation (such as that depicted in the grazing of stubble turnips) but also discursive practices, or boundary work (Ellis, Citation2016) which might ease the moral ambiguity of the farmer. The social media posts allow these more longer-term processes to be documented more fully and also to illuminate processes akin to what Wilkie (Citation2005) refers to as ‘concerned detachment’ – where () the farmer’s deindividualizing practices can be seen to coexist with a clear and stated (in the post) emotional attachment to their animals.

The temporal affordances of X are significant, here, as they allow not only the final aspects of recommodification to become visible but also the processes that precede this, which usually take place in the more private spaces of the farm. In addition to filling the time points not previously seen within the animal’s lifecourse, X’s affordances of frequency and durability also allow insight into farmer–livestock relations. and highlight how the ability to tweet at regular intervals and over a longer time period allows certain ‘plot lines’ (Riley & Robertson, Citation2021) to be drawn in relation to animals. In , we can see an example of what Wilkie (Citation2005) refers to acts of individuality, which make animals stand out from the crowd and wherein the animal subject begins to emerge. The focus on infantilisation and tameness imbues the piglet with a pet-like identity whilst occupying a different role as food which is also acknowledged in the tweet. In addition to highlighting the common approach of cross-species comparison which farmers undertook on social media, the example highlights how farmers’ decommodification of animals may be fleeting experiences – not limited to certain stages of the animal’s lifecourse, but through individual acts and individual moments where they step out of that view as commodity and exhibit, in this case, playful or childish characteristics. The opposite aspect of this is seen in , where these ‘cuter’ characteristics are seen as gradually receding – a process which the accompanying text suggests runs in parallel with a gradual recommodification process as the farmer explicitly notes how the chickens require more space and greater amounts of feed. Taken together, these examples illustrate how social media gives new insight to the (re)commodification process – allowing, through regular posts, the longer-run and cumulative nature of this process to be documented, rather than just the specific points in the process (such as the sale of animals), and the more fleeting, everyday, moments and encounters to be seen where animals may become more than simple commodities.

Whilst the two aforementioned examples highlight the specific moments () or points of transition in the recommodification process (), offers an example of the longer-term nature of the boundary-blurring within this process, and the coexistence of processes of individualization and deindividualization. Wilkie (Citation2005, p. 214) has noted in earlier discussion of human-livestock relations that the financial, commodified, relationship to animals coexists with ‘a less obvious, but nonetheless important socio-affective component’. In this instance, highlights how these more socio-affective elements become more obvious via social media, with pictures of both the farmer and their children engaging with animals not in agricultural production terms, but in something more akin to owner and pet. Whilst R1 foregrounds the commodified nature of the cows – referring to the cohort of calves from weaning (around 6–8 months) to around one year old – the text of the tweet reveals the intertwining lives of humans and livestock, and highlights how animals, for humans, not only act as commodities funding an occupation but also biographical markers of the evolution of their lives and the significance of their associated achievements. As Farmer 2 noted in interview ‘I’m really proud of our animals … I love them and want to show them off’. Important, here, is how X serves to alter the spatiotemporalities of the commodification process. The platform allows both depiction and reflection – with pictures enabling socio-affective engagements to be captured (and shared) and the associated text allowing a level of reflection which can be seen, in itself, as part of the boundary work as farmers face the moral ambiguity of rearing, using, and ultimately killing, livestock. Previous work has noted that such processes are usually spatialized in relation to places such as the abattoir (Convery et al., Citation2005) and may have temporalities associated with animals reaching the optimum size of slaughter, or reaching the end of their ‘productive’ lives (Riley, Citation2011). X, however, enables not only discursive practices of recommodification to take place but for the commodification/decommodifcation boundary to be challenged as pictures may be presented, and reflected upon, after animals’ sale or slaughter. Important, here, is how X allows the socio-affective engagements to be caught on camera and the accompanying text allowing a level of reflection and curation (cf. Berger, Citation2013), which itself may form part of the (re)commodification process helping navigate the moral ambiguity farmers may face in rearing, using, and ultimately killing, livestock. A further aspect of this is the impact of COVID19. Echoing the sentiment in , it illustrates how particular events or fleeting encounters may challenge the commodity/non-commodity boundary. Here, and in many similar tweets, COVID brought a change to the status of human-animal relations, both structurally in seeing farmers as ‘key workers’ in a wider hierarchy of mobilities that came into being during lockdown (Gorman, Citation2021) and also in seeing animals providing companionship as they took on the form of ‘lockdown buddies’, or as Farmer 12 noted ‘the only ones were allowed to mix with [laughter]’. Although work within wider animal and health geographies literature has noted some of the caring roles that animals take on, highlights how the multidirectional nature of care (Gorman, Citation2021) might also be visible in agriculture, as animals provide company as well as structure to farming days and lives.

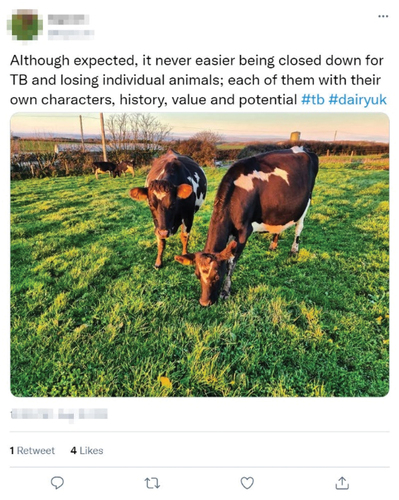

It has been noted that ‘qualities that define liveliness in the [animal] are precarious and can be dismantled easily with injury, aging, or a decline in fertility’ (Gillespie, Citation2020, p. 288) and the social media posts offered new ways of thinking about the moral geographies and the boundary work farmers do in relation to animal death. Bovine TB was a particularly prominent feature of the Tweets analysed, with the threat of culling infected animals, and the impact on wider herds and associated livelihoods. Whilst similar emotions are reported to those in discussion of Foot and Mouth, unlike the sudden culling, and hence lifescape disruption, reported on by Convery et al. (Citation2005), farmers were able to plot the timelines of culling – reporting on forthcoming TB test dates, as as well as near real-time reporting of the results of these tests. What this allowed is the process of recommodification to commence online, and for the moral ambiguity of their siutation to be eased through a positioning of victim to the disease and the government rules associated with it. , for example, allows both a verbalization of this recommodificaiton process – as animals individual characteristics are reflected upon in anticipation of their culling, and shows how this process need never be entirely complete as the durability of X means that posts about that animal, and the farmer’s associated responsibility, may exist (and be reflected upon) well beyond the life of the animal.

Constructing farmer and animal identities/

In addition to the focus on animals’ activities, it was clear from the analysis that curating posts was, in itself, ‘a self-representational strategy’ (Maddox, Citation2020). As the previous work on farming identities has shown, the display of farming competencies is central to the accruing of good farmer status, often in the form of at-a-distance ‘over the hedgerow’ observations (Burton, Citation2004). X posts allowed a change to the geographies of these observations by enabling a wider audience to view the previously less-accessible spaces of the farm, such as the cowshed. and are examples of this and show the way that farmers’ identities may be framed in relation to animals. Echoing the earlier observations, these show the importance of happy animals and, both implicitly and explicitly, say something about the farmers themselves. For , the attention focused on comfortable and ‘happy’ cows in their winter housing, whilst follows a similar theme and notes the ‘extra’ care that the animals receive at Christmas. Although Holloway (Citation2001) has noted the importance of care to the identity of hobby farmers, these examples highlight a similar case within more commercial farming systems. This is enabled by presenting pictures of animals resting and eating, and with accompanying text demonstrating how the farmers recognize their animals’ needs and how they react to these. Whilst good stockpersonship may traditionally be assessed by outcomes – that is through measures like milk yield or presentation at livestock sales and shows – social media allows the everyday places and lives of animals to be shared and farmers’ understanding of, and care for, their animals to be shown directly. Such frequency and detail allowed the broader narratives of intensive agriculture to be punctuated and, in the words of the farmers interviewed show that ‘we are more than factory farmers’ (Farmer 6) and ‘we care for them … not just kill them’ (Farmer 17).

Whilst many of the pictures posted on social media are of animals rather than their human carers or keepers, their composition and associated texts often position animals, extending Goffman’s (Citation1959) dramaturgical lexicon, as ‘stagehands’ in the performance of farming identities. Rather than seeing these as what Goffman (Citation1959) refers to as ‘props’, we prefer stagehands as it reveals more of the relations between animals and humans which, whilst they may arguably remain hierarchical, are nonetheless didactic and mutually reinforcing. shows an example of this in practice, with the cow the central figure depicted, but the reference to the cow as a ‘co-pilot’ foregrounding the activities of the farmer themselves. Here, the depiction of the use of a grass platemeterFootnote3 simultaneously combines a display of the farmer’s technical farming proficiency (embodied cultural capital) – in understanding the science of grass growth and measurement – and their care for animals in terms of providing optimum quality grazing. The cow, in this context, serves as the embodiment of farming skill – both more conventionally in her physical stature, alignment and markings, which show the clear success of the bloodlines and breeding programme of the farmer (Morris & Holloway, Citation2008), but also in being a stagehand in the farmer’s current performance of farming competence.

The depiction in , combining pictures of sheep with a view of the broader (snow-filled) landscape, emphasizes the animals’ reliance on the farmer – in this case via the provision of winter fodder as their grazing becomes inaccessible. Moreover, it serves to reinforce the characteristic of stoicism which has so often been noted in the discussion of farmer identity (Riley, Citation2016b). The spatial and temporal affordances of X – that is, the ability to tweet to a geographically unrestricted audience, ‘whenever we feel like it, day or night’ (Farmer 6) - meant that pictures of animals could show the variety, volume and repetitiveness of their tasks. As Farmer 11 suggested:

I’ll post a cow calving at one in the morning […] good for the people to see the hard work that goes into us producing their food.

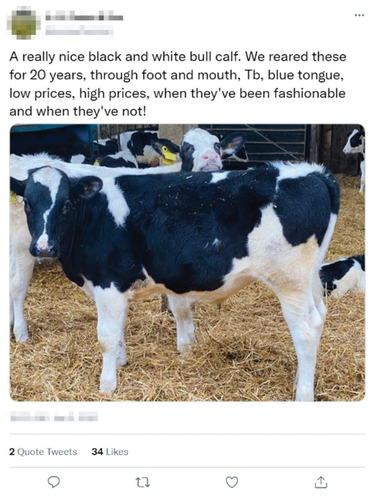

Important, here, is how animals as stagehands are used in the curation of posts which present the ‘hard work’ central to farming identity and status. Whilst tweets such as shows, individually and cumulatively, the real-time activities of animals, the accompanying text allowed a level of self-reflection not just on the care for animals, but farmers’ own thoughts and emotions associated with this care. shows an example of such reflection. The reference to ‘just a really good black and white calf’ hints at the dichotomy between ‘data’ and the visual in the assessment of livestock (see Morris & Holloway, Citation2008), with the latter being drawn on by the farmer here. The accompanying narrative in his tweet, however, moves beyond just the present, and specific, visual characteristics of this particular animal, to talk of the longer history of their practice and livestock relations. Although Yarwood and Evans (Citation2006) note that cultural capital may be derived from bloodlines of livestock – particularly as they demonstrate farming heritage and the persistence of a family farm in particular – this example considers longevity in terms of their continued, and repeated, management practices with animals, which involves buying new replacements each year. Here, they foreground their skill through being able to navigate and continue this practice over many years, showing their stoicism and steadfastness in the face of the changing fortunes (and fashions) of agriculture.

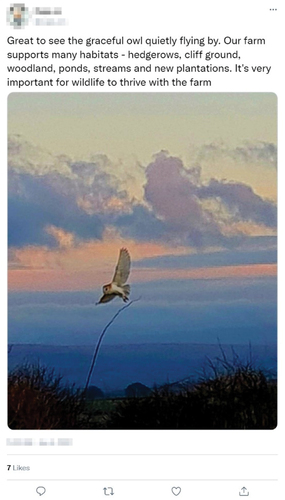

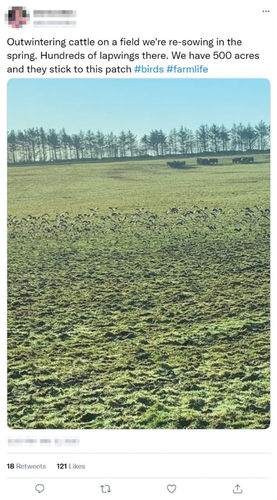

In addition to the qualities of good stockpersonship, exhibits the traits of size, frame and quality – that is, the animal’s productive qualities. As much research on farming identities has noted, production-orientated symbols are commonly referenced by farmers, and their symbolic power is enduring (Burton et al., Citation2021). Recent literature, however, has noted that farmers may be drawing on a wider range of symbols beyond just those focused on production – with more environmentally sensitive practices being a significant example (Riley, Citation2016a). and show how this identity-association with animals extends into these environmental discussions. These tweets show depictions of animals beyond livestock, but the farmer-livestock-landscape nexus is central to them. The depiction of the barn owl is accompanied with the text which focuses on the suitable habitat – including hedgerows – that are created and maintained as a result of the management of livestock on their farm. In discussing their curation of such posts, Farmers 1 and 7 noted:

I think everyone loves to see pictures of wildlife, especially birds … shows we’re doing a good job. (Farmer 1)

I like to have those things posted up there … to show people that we are not ruining the countryside. [laughter] (Farmer 7)

In both cases there was a conscious curation of the posts presented, with the farmers acutely aware of the likely responses to their posts. As noted earlier, the presentation of animals online can open farmers up to public criticism, especially when platform settings mean their posts are available to the wider public, and Farmer 1 notes how pictures of wildlife are potentially more palatable to a broader audience and, as they go on to note, carries the connotation that they are ‘doing a good job’ from an environmental perspective on their farm. Farmer 7 is more explicit in noting that their curation strategy is aimed at correcting the broader narrative of farming as being harmful to the environment, and uses posts of the flourishing wildlife on their farm as visible evidence of the positive impact of their farming. follows a similar display of environmental good farming (Riley, Citation2016a), but places emphasis on the intra-species compatibility on their farm. Whilst there are debates around outwintering cattle from an environmental perspective – focused specifically on the impacts of poaching – the farmer provides the visual evidence of large numbers of lapwing, a bird species whose decline is associated with agricultural intensification, and notes their active preference for this particular area of land (from over 500 acres). This post illustrates not only how species productively coexist on their farm but also illustrates how more individualistic managements may have some environmental benefit. Whilst the use of outdoor feeders, as seen in the background of this picture, are actively discouraged on open land within agri-environment schemes, the farmer's posts show how cows may create a suitable micro-climate for these endangered birds to thrive.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted how digital and material lives are intertwined and entangled (Kinsley, Citation2013) and offers a new direction for understanding human-animal encounters by exploring the ways in which farmer and animal identities are mediated by social media. The paper has shown that the visual culture of social media allows a reworking of the spatio-temporalities of animal-human relations and offers farmers the opportunity to co-construct their identities with their livestock and farming practices. In the same way that Butler and Holloway (Citation2016, p.526) notes how mediating technologies of Automated Milking Systems involve a ‘negotiation of new ways of “being” a dairy stockperson’, online platforms may facilitate both new ways of being a stockperson and allow a more fine-grained picture of those human-livestock interactions which are not usually visible to a wider public. Whilst animal-human relations in places such as agricultural shows or auction markets offer more choreographed performances (Holloway, Citation2001), these online relations are, we have seen here, both more individual – with common tropes including humour and foregrounding animals’ appealing aesthetic characteristics – and more mundane.

Although previous research has highlighted the significance of material spaces to the boundary work around processes of re/de-commodification and associated moral ambiguities, we have shown the social media can instate these boundaries and encompass everyday activities – such as a cow becoming part of a family photograph. The paper has shown that being able to present, through posts, the micro spatio-temporalities of everyday farming life, social media gives an insight into how the decommodification may be fleeting experiences and individual moments, rather than limited to specific animals lifecourse transitions (such as moving into production, or being the right age for sale or slaughter). As such, the paper moves beyond the common dualism which frames more commercial farming systems as deindindividulasing animals, versus less commercial, or hobby, farms as individualizing and more caring, by noting the individual representations of care, familiarity and emotion that more commercial farmers may be able to present on social media. It also troubles this boundary through allowing pictures of, and post-hoc reflections upon, animals to take place – as what may be termed a digital afterlife – beyond the finality of the conventional points of recommodification when animals have left their farm or their care. Whilst recognizing the human-led accounts we draw from, the paper has seen that social media offers insights for the wider discussion of animal agency and subjectivity (Fletcher & Platt, Citation2018), allowing reports of resistant, individualistic or unexpected behaviours to be articulated. Moreover, social media posts and associated practices of curation offer a route through which we might better understand the multifarious ways that animals might resist, elide and be (re)placed into the ‘categorical and practical orderings of people’ (Fletcher & Platt, Citation2018, p. 225).

The paper has seen how social media use may be a self-representational strategy for farmers, wherein the presentation of their interactions with animals is an identity-enhancing act. Whilst farmers’ skills of stockpersonship may often be assessed on outcomes – such as sale price or level of animal productivity (see R. J. Burton et al., Citation2021) – the more frequent presentations via social media allow more everyday practices and engagements to be seen. From here, farmers are able to demonstrate, to others, their skills of stockpersonship and care for animals. The paper has noted the multifarious ways that farmers discursively position animals within this process – including as co-operators, rather than exploited units of production, and as lively, wilful and sometimes unruly characters rather than deindividualized members of herds of flocks. Animals are framed relationally to humans and are often afforded human characteristics in order to include them in the same moral community. Here, the paper contributes to the wider discussion of emotional and moral geographies. Geographers have noted how moral boundaries are ‘naturalized in, and through, landscapes, in the interplay of their material and representational forms and related significations’ (Setten & Brown, Citation2009, p.191), and the paper has seen how the (re)presentation of animals on social media is consciously choreographed, with the framing of particular images – such as those of cute, happy, or contented animals – and the rhetoric strategy of speaking from the perspective of animals serving to offer ‘emotional arousal’ to their audiences. These observations are important for wider understandings of how emotions are placed and social (Anderson & Smith, Citation2001), noting how social media may facilitate the boundary work of (and around) these emotions, allowing individuals to document and (re)present their everyday emotions, facilitating a reflection on these through (through processes of curation) and to utilize the affective qualities of the platform to direct audiences to a particular interpretation.

In highlighting these practices, the paper illustrates that the ‘networks of practice’, noted in previous geographical work, move beyond the farmer and their livestock to include a wider (virtual) audience. Our interviews reveal that social media posts are subject to curation as a result of reflection about imagined audiences, dominant discourses and their lived experiences alongside animals, through which the presentation of the (farming) self is mobilized. Methodologically, the paper opens up discussion of not only how social media posts such as photographs may be both (re)presentations and performances (cf. Berger, Citation2013) – and hence how they can be used to understand what places and practices are significant to those individuals and contexts – but also how the associated curation may tell us about the continuing struggles around the presentation of the self online (Ash et al. Citation2018) and how social media may be a reflexive space through which users may undertake a range of affective practices. Future work could, accordingly, extend our analysis of farmers’ use of social media to include how wider audiences – from both within and beyond agriculture – receive, react to, and understand these posts.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the British Academy for funding this research, and the to the farmers who generously gave their time to be interviewed. Any errors or omissoins remain our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. X (formerly Twitter) is a social media and social networking service (with over 350 million estimated users) which allows users to send and respond to messages in a 280-character-long form, including images and videos, known as Tweets.

2. A hashtag advertised by the British supermarket Morrisons and the Farmers Guardian to encourage farmers to show consumers the work that they undertake in producing the food that they eat.

3. Device used for measuring grass cover in grazing land.

References

- Anderson, K., & Smith, S. J. (2001). Editorial: Emotional geographies. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 26(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5661.00002

- Ash, J., Kitchin, R., & Leszczynski, A.(2018). Digital turn, digital geographies?. Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 25–43.

- Beierl, B. H.(2008). The Sympathetic Imagination and the human—animal bond: Fostering empathy through reading imaginative literature. Anthrozoös, 21(3), 213–220.

- Berger, J.(2013). Understanding a photograph. Penguin.

- Berland, J. (2019). Virtual menageries: Animals as mediators in network cultures. MIT Press.

- Blattner, C. E., Donaldson, S., & Wilcox, R.(2020). Animal agency in community. Politics and Animals, 6(0), 1–22.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Polity Press.

- Buller, H., & Morris, C. (2003). Farm animal welfare: A new repertoire of nature‐society relations or modernism re‐embedded? Sociologia Ruralis, 43(3), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00242

- Burton, R. (2004). Seeing through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘productivist’ behaviour. Sociologia Ruralis, 44(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2004.00270.x

- Burton, R. J., Forney, J., Stock, P., & Sutherland, L. (2021). The good farmer: Culture and identity in food and agriculture. Routledge.

- Burton, R., Kuczera, C., & Schwarz, G. (2008). Exploring Farmers’ Cultural Resistance to Voluntary Agri-environmental Schemes. Sociologia Ruralis, 48(1), 16–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00452.x

- Butler, D., & Holloway, L.(2016). Technology and restructuring the social field of dairy farming: Hybrid capitals,‘stockmanship’and automatic milking systems. Sociologia Ruralis, 56(4), 513–530.

- Chao, S. (2023). Bouncing back? kangaroo-human resistance in contemporary Australia. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6(1), 331–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486221084194

- Charles, N. (2014). ‘Animals just love you as you are’: Experiencing kinship across the species barrier. Sociology, 48(4), 715–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513515353

- Convery, I., Bailey, C., Mort, M., & Baxter, J. (2005). Death in the wrong place? Emotional geographies of the UK 2001 foot and mouth disease epidemic. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.10.003

- Donald, M. M. (2019). When care is defined by science: Exploring veterinary medicine through a more‐than‐human geography of empathy. Area, 51(3), 470–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12485

- Einspänner, J., Thimm, C., & Dang-Anh, M. (2014). Computer-assited content analysis of X data. In K. Weller & J. Burgess (Eds.), X and society (pp. 97–108). Peter Lang.

- Ellis, C. (2016). Boundary Labor and the production of emotionless commodities: The case of beef production. The Sociological Quarterly, 55(1), 92–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12047

- Evans, N., & Yarwood, R.(1998). New places for” old spots”: The changing geographies of domestic livestock animals. Society & Animals, 6(2), 137–165.

- Fletcher, T., & Platt, L. (2018). Just) a walk with the dog? Animal geographies and negotiating walking spaces. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1274047

- Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Toward an integrated and differential approach to the relationships between loneliness, different types of Facebook use, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Communication Research, 47(5), 701–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215617506

- Gillespie, K. (2020). The afterlives of the lively commodity: Life-worlds, death-worlds, rotting-worlds. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(2), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20944417

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

- Gorman, R. (2021). Animal geographies in a pandemic, COVID-19 and similar futures. Springer.

- Hamilton, L., & Taylor, N. (2017). People writing for animals, ethnography after humanism. Springer.

- Heckathorn, D. D. (2002). Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems, 49(1), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2002.49.1.11

- Holloway, L. (2001). Pets and protein: Placing domestic livestock on hobby-farms in England and Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 17(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(00)00045-0

- Holloway, L. (2007). Subjecting cows to robots: Farming technologies and the making of animal subjects. Environment and Planning D-Society & Space, 25(6), 1041–1060. https://doi.org/10.1068/d77j

- Holloway, L., & Morris, C. (2014). Viewing animal bodies: Truths, practical aesthetics and ethical considerability in UK livestock breeding. Social & Cultural Geography, 15(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.851264

- Holton, M., Riley, M., & Kallis, G. (2023). Keeping on [line] farming: Examining young farmers’ digital curation of identities,(dis)connection and strategies for self-care through social media. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 142, 103749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103749

- Jacobson, J., Hodson, J., & Mittelman, R. (2022). Pup-ularity contest: The advertising practices of popular animal influencers on Instagram. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121226

- Kaarlenkaski, T.(2014). Of cows and women: Gendered human-animal relationships in Finnish agriculture. Relations: Beyond Anthropocentrism, 2(2), 9–26.

- Kinsley, S. (2013). Beyond the screen: Methods for investigating geographies of life ‘online’. Geography Compass, 7(8), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12062

- Leszczynski, A. (2019). Platform affects of geolocation. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 107, 207–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.011

- Linné, T. (2016). Cows on Facebook and Instagram. Television & New Media, 17(8), 719–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476416653811

- Liu, C. (2022). Imag(in)ing place: Reframing photography practices and affective social media platforms. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 129, 172–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.01.015

- Lorimer, J.(2007). Nonhuman charisma. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(5), 911–932.

- Lynch, C. R., & Farrokhi, B. (2022). Digital Geographies and everyday life: Space, materiality, agency. In S. A. Lovell,S. Coen,& M. Rosenberg (Eds.),The Routledge handbook of methodologies in human geography (pp. 196–206). Routledge.

- Maddox, J. (2020). The secret life of pet Instagram accounts: Joy, resistance, and commodification in the Internet’s cute economy. New Media & Society, 23(11), 3332–3348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820956345

- Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: X users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

- McCrow-Young, A. (2021). Approaching Instagram data: Reflections on accessing, archiving and anonymising visual social media. Communication Research & Practice, 7(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2020.1847820

- McLoughlin, E., & Casey, J. (2022). On “finishing” a visual memoir of care and death on an Irish cattle farm. Visual Anthropology Review, 38(1), 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12256

- Miele, M. (2016). The making of the brave sheep or … the laboratory as the unlikely space of attunement to animal emotions. GeoHumanities, 2, 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2016.1167617

- Morris, C., & Holloway, L. (2008). Genetic technologies and the transformation of the geographies of UK livestock agriculture: A research agenda. Progress in Human Geography, 33(3), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508096033

- Ngai, N. (2022). Homemade pet celebrities: The everyday experience of micro-celebrity in promoting the self and others. Celebrity Studies, 14(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2022.2070714

- NVivo. (2020). NVivo User guide. https://help-nv.qsrinternational.com/20/win/Content/projects-teamwork/saveand-copy-projects.htm

- Riley, M. (2011). ‘Letting them go’ – agricultural retirement and human–livestock relations. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 42(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.08.004

- Riley, M. (2016a). How does longer term participation in agri-environment schemes [re] shape farmers’ environmental dispositions and identities? Land Use Policy, 52, 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.010

- Riley, M. (2016b). Still being the ‘Good Farmer’: (non-)retirement and the preservation of farming identities in older age. Sociologia Ruralis, 56(1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12063

- Riley, M., & Robertson, B. (2021). # farming365–exploring farmers’ social media use and the (re)presentation of farming lives. Journal of Rural Studies, 87, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.08.028

- Riley, M., & Robertson, B. (2022). The virtual good farmer: Farmers’ use of social media and the (re) presentation of “good farming”. Sociologia Ruralis, 62(3), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12390

- Schneider, C. J. (2016). Police presentational strategies on X in Canada. Policing and Society, 26(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2014.922085

- Schuurman, N. (2014). Blogging situated emotions in human–horse relationships. Emotion, Space and Society, 13, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2014.08.002

- Sergi, V., & Bonneau, C. (2016). Making mundane work visible on social media: A CCO investigation of working out loud on X. Communication Research & Practice, 2(3), 378–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2016.1217384

- Setten, G., & Brown, K. M.(2009). Moral landscapes. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 7, 191–195.

- Shifman, L.(2013). Memes in digital culture. MIT press.

- Townsend, L., & Wallace, C. (2016) Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. Available at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf

- Treem, J. W., & Leonardi, P. M.(2013). Social media use in organizations: Exploring the affordances of visibility, editability, persistence, and association. Annals of the International Communication Association, 36(1), 143–189.

- Turnbull, J., Searle, A., & Adams, W. M. (2020). Quarantine encounters with digital animals: More-than-human geographies of lockdown life. Journal of Environmental Media, 1(Supplement 1), 6.1–6.10. https://doi.org/10.1386/jem_00027_1

- Wang, J., & Wei, L. (2020). Fear and hope, bitter and sweet: Emotion sharing of cancer community on X. Social Media & Society, 6(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119897319

- Wilbur, A., & Gibbs, L. (2020). ‘Try it, it’s like chocolate’: Embodied methods reveal food politics. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(2), 265–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1489976

- Wilkie, R. (2005). Sentient commodities and productive paradoxes: The ambiguous nature of human–livestock relations in Northeast Scotland. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.10.002

- Yarwood, R., & Evans, N. (2006). A lleyn sweep for local sheep? Breed societies and the geographies of Welsh livestock. Environment and Planning A, 38(7), 1307–26. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37336