ABSTRACT

Qatar University is currently at a crossroads, having to respond to competing institutional, national, and international language policy issues. This paper aims to reveal how Qatar University's internal and external stakeholders perceive the future directions of the university's language in education policy. In particular, through Q-methodology, we attempt to uncover social perspectives on three educational language policy options, proposed to the university's higher administration, by the strategic planning team, to respond to pressing linguistic needs and priorities. The aim is to initiate and support a more-informed discussion about language in education policy at Qatar University. Results indicate strong agreement among the various perspectives taken by the university's stakeholders regarding the need for a language in education policy that seeks to manage the relationship between Arabic and English in a parallel way.

Introduction

Internationalization policies at universities worldwide have contributed to questions of medium of instruction (Crandall & Bailey, Citation2018). Universities nowadays find themselves in convoluted linguistic situations that could be characterized by the pressure to manage internationalized faculties and student bodies, the imperative to prepare students to function in a globalized world, and the inevitability of adopting internationalized curricula. Within this trend of internationalization, ‘English has become the lingua franca that indexes prestige, competitiveness, employability, and economic success’ (Miranda et al., Citation2018, p. 203).

However, the linguistic consequences of internationalization are not similar for all universities. In countries where English is the dominant or official language, internationalization in higher education has been realized as, ‘business as usual’ (Liddicoat, Citation2018). Such universities’ language planning endeavors have been mostly intended to address students’ deficient linguistic abilities in the form of academic support programs (Baik & Greig, Citation2009) or in the form of assessing the English language capabilities of the enrolled students (Murray, Citation2014). Whereas, in non-Anglo-Saxon countries, the linguistic tension between the need to introduce English as a medium of instruction in universities, and the threat of losing the status of the national language(s) is salient. Higher education institutions in such countries have been increasingly facing the need to plan languages to respond to the changing internationalized linguistic context in which they operate, while at the same time aligning with national language policies that promote indigenous language(s). In such situations, the development of a comprehensive language in education policy becomes a complex process through which the demands of all stakeholders must be met concurrently.

This paper examines the situation at Qatar University (henceforth QU); recognized as the world's most international university according to The Times Higher Education World University Rankings (Wazen, Citation2016).Footnote1 Through Q-methodology, we attempt to reveal how QU's stakeholders, including faculty members, administrators, students, parents, educational partners, and market partners, perceive the future directions of the university's language in education policy. In particular, we aim to uncover social perspectives taken by QU's stakeholders on three educational language policy options, proposed to the university's higher administration, by the strategic planning team, to respond to pressing linguistic needs and priorities. Before considering this in more detail, we first examine how universities’ roles have changed over time, and briefly discuss the implications of these changes on language in education policies.

Universities in change: implications on language in education policies

Chen and Lo (Citation2012) wrote, ‘the idea of university across Plato, Newman, Kant, Humboldt, Weber, Japers, Parsons and Habermas to Minogue, Kerr, Branett and Delanty have been fading from the present discussion about higher education’ (p. 51). The university of the past was seen as a learning institution for elites who had the economic capacity to pursue their quest for knowledge. As Morley (Citation2010) noted, universities were synonymous with elitism, exclusion and inequality. To a certain extent, universities were cultural landmarks for their home nations. They educated their own students, prepared their own staff intellectually, and stowed the cultural histories of their regions (Hultgren et al., Citation2014).Footnote2

Today's idea of a university is another story. The global trends of commercialization and marketization have led to seismic changes in higher education institutions worldwide. Universities nowadays are diversified, globalized, marketized, technologized, neo-liberalized, and privatized (Morley, Citation2012). The forces that brought about these metamorphoses are multiple and interactive. Under the condition of globalization, wider political and economic processes led universities worldwide to adopt market-based systems, to commercialize their research, to democratize their educational systems through massification and diversification processes, and led to the competitive struggle over achieving the status of world-class university (Henkel, Citation2010). All of these metamorphoses brought with them various forms of external and internal regulations.

Universities had now become institutions of societies as distinct from the old days when they were institutions in society (Barnett, Citation1994). Universities are now receiving close attention from the state, in exchange, governments place demands on them. As Barnett (Citation2012) notices, knowledge inquiry and learning processes have to prove their worth through their economic impact. It is not enough that these activities are applicable; now they have to generate an economic return in some form. Consequently, universities are perceived as economic agents competing in a lucrative market and promoting the brand of the national state internationally.

Naturally, the changing roles of universities have had an impact on educational language policies. At Universities other than Anglo-Saxon, the discourses of internationalization, globalization, and marketization were the main driving force behind the growing role of English as a medium of instruction. Such universities have now a clear utilitarian mission: to foster economic competitiveness at the global level. The teaching of and in English facilitates such mission. The concept of ‘international education’ has been deployed to refer to curricular elements that work towards fostering students’ competencies to function in international environments. This includes teaching in and learning of English as a lingua franca, among other several activities aimed at contributing to international and intercultural understandings. The interest in the English language became ‘economic’ rather than ‘scholarly.’ Many universities started to market their programs as being taught in English in a further attempt to tap into the lucrative student market (Hultgren et al., Citation2014). This served to attract not only international students but also local students who aspire to receive international education.

The globalization of the market economy implies that nation-states are nowadays more or less interdependent, and compelled to compete in the same markets for the same resources, including human capital such as universities’ graduates. This has, in many ways, intensified global competition among universities. In effect, global rankings started to have an outsized impact on universities. Nowadays, many universities have a ranking strategy and/or institutional units that benchmark rankings performance. Hultgren (Citation2014) establishes that there is a correlation between university rank and Englishisation. For Coleman (Citation2013), the battle for excellence has played a crucial role in the growing role of English in universities worldwide. Even in countries that have long held onto a policy of using only their national languages (e.g. France, Japan, Germany), they are now using English as a medium of instruction after realizing the importance of the language for competing effectively in the global arena (Gill, Citation2010). In effect, a characteristic divide has been made, in many non-Anglo-Saxon universities, between teaching the natural, technical, and medical sciences in English (shortened to the Sciences) and teaching the human and social sciences in the local language(s) (shortened to the Humanities). Not only is the English language more widespread in Sciences than in Humanities, but there is also a tendency for the language to be instrumentally constructed in such majors (Hultgren et al., Citation2014). Still, many argue that associating local languages with ‘soft’ (i.e. non-science) subjects will have adverse effects on the development of local languages as a vehicle of scientific knowledge (Annamalai, Citation2010, p. 191). For this, several universities in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland have officially adopted a policy of parallellingualism. Parallellingualism, or parallel language use, is a term coined, perhaps in 2002 (Hultgren et al., Citation2014), to refer to ‘the concurrent use of several languages within one or more areas. None of the languages abolishes or replaces the other; they are used in parallel’ (Nordic Council, Citation2007, p. 93). Under internationalization, such universities found in parallellingualism a way to both avoid a threat and seize an opportunity. The threat is the ‘domain loss’ of the local languages, which refers to the idea that, in a given domain, the national language may lose status and/or functionality if used less or not at all (Hultgren et al., Citation2014). The opportunity is, adopting a parallel language use policy allows for national languages to remain ‘society bearing,’ that is, fully functional in each register and domain. For a language to be a society- bearing, it has to be used in all domains, which includes academia. Parallellingualism then could ensure that the ‘domain loss’ is avoided and that the national language(s) is retrained in a ‘society bearing’ state by using it in parallel with global language(s). Although the concept of ‘domain loss’ has attracted a fair amount of criticism (see Preisler, Citation2009; Haberland, Citation2005), and the notion of parallel language use lacks clarity (Harder, Citation2008), according to Phillipson, parallellingualism can be seen as ‘a recipe for raising language awareness and ensuring a reciprocal dialectic between the national language and English’ (Citation2018, p. vi).

Internationalization then has led to changes in the language ecology of contemporary universities and has triggered reactions and positionings regarding the use of the languages involved (Cots et al., Citation2014). Several studies have investigated universities’ language in education policies in response to internationalization (e.g. Villares, Citation2019; Soler & Gallego-Balsà, Citation2019; Mortensen, Citation2014), and some have identified the ways through which different stakeholders perceive the situation (e.g. Garrett & Gallego Balsà, Citation2014; Lazdowski, Citation2015; Lasagabaster, Citation2015). Although such studies focused on different contexts, they still share one aspect: the coexistence of two languages, one of them being a local language struggling for maintenance, while the other being a dominant language with a significant international presence. This study contributes to such a growing body of literature. It reports about the situation in QU, aiming to reveal the social acceptability of three educational language policy options proposed to the university's higher administration, by the strategic planning team, as the following section further explains.

Language in education policy at Qatar University

In this section, we trace QU's language in education policy trajectory over the past two decades. We do this through discoursing official documents, chiefly among them is the White Paper; a document issued by the university's strategic planning team to determine its direction for the 2017–20 strategic planning cycle.

Among the many issues discussed in the White Paper, conflicts in determining QU's language in education policy are outlined. Making reference to Qatar's 2030 National Vision, turning the country into a competitive knowledge-based economy, the White Paper retells the story of Qatar's educational reform. Through the Education for a New Era initiative, launched in 2002, the Qatari leadership sought to prepare Qataris for the challenges of the new century. The initiative aimed to provide a series of professional degree programs that bridged the gap between tertiary education institutions and the labor market, specifically in the fields of petroleum engineering, business administration, and health, with a focus on English as the medium of instruction. During that period, QU enforced English as the medium of instruction in almost all its programs.

Yet, a decade after the reform began, according to the White Paper, English as the medium of instruction proved to be ‘ineffective as it created a barrier for students’ success’ (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 28). Between 2002 and 2012, QU's language in education policy became a fiercely debated issue, especially after the revelation of Qatar's third Human Development Report (Citation2012), which argued: ‘Qatar has made large investments in education and training infrastructure for Qataris, and multiple opportunities now exist. Nevertheless, education performance is not progressing at a commensurate pace, despite a decade of reforms’ (III). According to Qatar's five-year National Plan (Citation2011), the problem was that fewer Qataris are gaining admission to college, and more are dropping out of higher education. The report focused on low enrolment levels for Qatari males, attributing this to the fact that many Qataris avoid public higher education because of its English language perquisites.

As a result, the White Paper explains that, in 2012, the Qatari government issued a law declaring Arabic as the medium of instruction at public educational institutions. For QU, the law required the university to adopt Arabic as the medium of instruction in Law, International affairs, Business and Economics, and Journalism and Mass Communication programs. The White Paper explains that QU has activated the law in the required programs, while other technical programs, which are considered important in the local market, continued to be taught in English. Yet, the White Paper argues that this has created a linguistic gap between high school graduates and QU study requirements and refers to a ‘substantial deficiency’ in the quality of high school students (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 28). The deficiency created is that students in public schools, being taught in Arabic, are not prepared for QU's scientific programs, being taught in English, by the time they graduate from secondary school.

In addition to referring to the university's obligation to align with Qatar's 2030 National Vision of establishing a knowledge-based economy, the White Paper also stresses, ‘there is a need for the university to be responsive to the cultural sensitivities regarding the medium of instruction’ (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 28). Referring to the 2016 draft law on the Preservation of Arabic Language that makes it a requisite for all official institutions in Qatar to use the Arabic language in all documents, contracts, transactions, correspondence, publications, and advertisements, the White Paper acknowledges that this may require QU to teach its programs in Arabic. Yet, shifting fully into Arabic has been seen as a risk as ‘Qatar University has seen a much wider focus on international partnerships rather than on a regional level’ (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 34).

The White Paper concludes that QU is, therefore ‘unable to satisfactorily meet the expectations of all of its stakeholders [regarding its language in education policy] given this complex picture of high-school graduates with differing language competencies and the needs of the labor market’ (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 28). In proposing strategic options for dealing with the situation, the White Paper suggests adopting one of three educational language policy options: (1) offer of humanities and social sciences programs in Arabic, while offering scientific programs in English through a Bilingual Scientific Model; or (2) redefine the university as one where all degree programs at all levels, in addition to all communications, are conducted in the Arabic language through a Culturally Grounded Model; or (3) redefine the university as an Arabic centered institution where all programs are offered in Arabic as the medium of instruction, while also offering parallel tracks in English; based on a sufficient and identifiable demand from prospective students and employers through a Competitive Bilingual Model (Qatar University, Citation2016, p. 28).

Although QU has not yet decided officially on any of the proposed models, a functional division was made between teaching Humanities in Arabic, while teaching Sciences in English. Still, according to the Student Satisfaction Survey (2018–2019), which was issued by the university, and involved 1071 graduates from different QU colleges, the satisfaction of graduates in Colleges of Pharmacy and Engineering with their Arabic language reading and writing skills is 57%, whereas 55% of graduates in Islamic Studies College are not satisfied with their English language skills in reading and writing. According to QU, both percentages are below expectations (Qatar University, Citation2019, p. 1). This, among other issues, urges QU to develop and implement a comprehensive language in education policy.

While the White Paper has identified possible language in education policy options for QU, a wide spectrum of societal opinion exists around all proposed options. In this paper, we attempt to reveal the different social perspectives that exist around the three proposed language in education policy options. The aim is guide policymakers in developing and implementing a comprehensive language in education policy that satisfies the needs of its various stakeholders.

Methodology

For exploring QU's stakeholders’ perspectives on the three proposed language in education policy options, Q-methodology (henceforth Q) was utilized. One of the prominent ways in which Q can be used is to reveal different social perspectives that exist on an issue or topic (Webler et al., Citation2009). Q is a qualiquantological method (Stenner & Rogers, Citation2004) that statistically quantifies individuals’ subjectivity, while providing in-depth qualitative descriptions (Kamal et al., Citation2014). William Stephenson, the inaugurator of Q, was interested in building a research methodology that examines the subjectivity of the research informants, which he defines as ‘what one can converse about to others or to oneself’ (Citation1989, p. 501). He argued that subjectivity has to be studied empirically by accepting participants’ constructions of their worlds, rather than imposing researcher- defined categories onto it. For this, Stephenson introduced Q as a way to reveal shared viewpoints about an issue, in a purposefully selected group of people, by combining the qualitative sorting technique and the quantitative by-person factor analysis, as opposed to by-variable factor analysis done with SPSS (Lundberg, Citation2019). Q has proven to be a reliable research methodology in various studies (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012).

In language policy field, Lo Bianco (Citation2015) poses that Q is a highly adaptable research tool to the different circumstances, settings, and needs of agencies commissioning policy advice. He maintains that Q offers the prospect of a sharp focus on key questions in language policy, especially the centrally important question of exploring, defining, and analyzing language problems. He identified four stages in a Q research. First, the public argument around language problems is extensively sampled to form what is referred to as a concourse. The concourse includes a number of statements (Q-statements); each suggests a subjective opinion about the issue under investigation. Second, from the concourse, a representative sample of the statements is selected (the Q-set). Third, participants are purposely selected and invited to rank the Q-set through sorting activity (i.e. doing a Q-sort). Finally, Q-sorts are analyzed using statistical techniques of correlation and inverted factor analysis to reveal underlying patterns. Finding the patterns suggests the existence of inter-subjective ordering of beliefs shared among participants. As such, the results of the analysis in a Q study are interpreted in the form of different social perspectives (Webler et al., Citation2009).

Research design

For this study, a rich and representative body of statements that capture the range of positions taken by QU's stakeholders around each language in the education policy option proposed by the White Paper was collected. The total number of the statements in the concourse was 47. We draw on various sources such as newspaper articles, policy documents, and informal discussions with individuals who have interest and relevance to the issue under investigation. Next, we culled the initial statements to reduce them. This involved studying each statement individually and discarding repetitious, marginal, idiosyncratic, or ephemeral statements (Lo Bianco, Citation2015). The culling process was aided by the application of Dryzek and Berejikian’s (Citation1993) political discourse analysis matrix. To ensure reaching a balanced and well-formulated Q-set with a good coverage of the three language in education policy options proposed by the White Paper, a strategic sampling was adopted (Webler et al., Citation2009). That is, we categorized statements under three main categories: QU as a learning environment, QU as a work community, and QU as a societal agent. These categories emerged inductively from our initial analysis. This resulted in reducing the initial statements to 23 Q-items, which were reformulated in both Arabic and English, being the native languages of the potential participants. Each statement was given an identifying number to facilitate data recording. Q-items in this study contain ‘excess meaning’ (Webler et al., Citation2009). Two external experts were approached to evaluate the Q-items in terms of their simplicity, clarity, wording, and breadth and depth (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). Then, the culled items were piloted with four individuals. This led to slight adjustments, after which the Q-set was finalized. shows Q-items in relation to language in education policy options proposed by the White Paper, while Q-items can be found in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Q-items in relation to language in education policy options.

Next, participants were selected. As Q method represents an inversion of more traditional R research methods, each participant in this study was selected purposefully and treated as a variable. Lo Bianco (Citation2015) argues that the key criterion in selecting participants in a Q study is their relevance to the question, usually in the form of recent and active participation in the debate, research, or policymaking on the particular language problem. To select participants, we needed first to identify QU's stakeholders. In this regard, we depended on The International Institute of Business Analysis's definition of a stakeholder in the context of business analysis or change as: ‘A group or individual with a relationship to the change, the need, or the solution’ (IIBA, Citation2017, p. 4). For the purpose of this study, such definition applies to those directly involved with QU's language in education policy (students, parents, QU's faculty and administrators), those who provide inputs (high school principals and teachers), and those who receive the outputs of the process (local market), as well as others who are impacted in some way (partners from other universities in Qatar). shows QU's stakeholder categories for this study.

Table 2. QU's stakeholders.

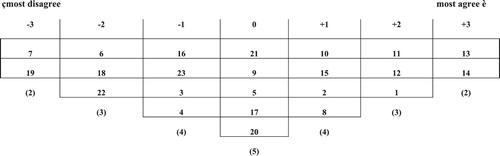

65 participants from all QU's stakeholder categories were interviewed to conduct the Q- sorting. Participants were provided with explanatory information about the research and signed a consent form. After gathering their demographic data (i.e. age, gender, education level, and occupation), participants were provided with a blank sorting grid and were asked to sort 23 items on a scale −3 to +3 in response to the question (or the condition of instruction in Q terminology): rank these statements according to your level of agreement/ disagreement. The grid was constructed as a 7-point forced quasi-normal distribution as it facilitates revealing perspectives (Brown, Citation2008). The right-most column was labeled as the most agree (+3), while the left-most column was labeled as the most disagree (−3), and the central column was labeled as the neutral (0). Upon the completion of sorting, participants were encouraged to elaborate on their choices of items at +3 and −3. Their responses were transcribed for further analysis. Participants were also asked if they would add any additional statements, and such suggestions were taken. Finally, the resulting sorts were analyzed using PQ-Method software (Schmolck, Citation2014), looking for overall correlations, weighing single statements, and scores for groups of statements, as the following section further explains.

Analytical procedures

The data gathered from the 65 participants form all QU's stakeholder categories were statically analyzed using PQ-Method software, which provides a variety of by-person factor extraction, rotation methods, and a number of statistical measures. Once we had completed the data entry, we performed a centroid factor analysis, which is a factor extraction procedure that looks for repeated patterns by performing by-person factor analysis. This followed by a varimax rotation to account for the maximal amount of opinion variance (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). After the elimination of factors with insufficient statistical strength, four factors (F-1, F-2, F-3, and F-4) were extracted, accounting for 53% of the opinion variance. Each of these factors exemplifies an archetypical social perspective that represents participants with similar views. Brown’s equation (Citation1980) was used to calculate each Q-sort's significance at the p < 0.01 level: 2.58 × (1 ÷ √no. of items in Q set). For this study, factor loadings of at least ±0.54 were significant at the p < 0.01 level.

50 of the 65 Q-sorts loaded significantly on one of the four factors. All Q-sorts loaded significantly on the same factor were emerged to a signal ideal typical Q-sort according to the procedure of weighted averaging. Such shared understanding of the issues under investigation is referred to as factor array. shows the factor array for F-1 in this study. Then, the crib sheet method, as described by Watts and Stenner (Citation2012), was utilized for a holistic inspection of the Q-items in the factor arrays. We looked at each factor array independently, examining statements that were given the highest ranking (+3), the lowest ranking (−3), those ranked higher in which factor than by any other factor, and those ranked lower in that factor than by any other. This prevented the oversight of items ranked indifferent (or zero) in a given factor for the description of its viewpoint if they were given extreme scores in other factors (Lundberg, Citation2019). We also created largely drawn versions of each factor array. In such drawings, we added the demographic and other relevant information to analyze further the patterns found among the Q-sorts.

Results

As mentioned earlier, 4 factors (F-1, F-2, F-3, and F-4) were extracted; each represents a social perspective on QU's language in education policy shared by a group of participants. All four emerged factors met sufficient statistical criteria to be included in this study despite their varying explained opinion variance. No confounded loadings were found. presents a summary of all factors, including the opinion variance and significant loadings separated by stakeholder category, while Q-sort values for items are presented in Appendix 1.

Table 3. Opinion variance and significant loadings separated by stakeholder category.

In what follows, a qualitative interpretation and description of the single factors is presented. We developed labels for the emerging factors that reflect the general sentience of participants (Stenner & Rogers, Citation2004). We also use Q-items and comments made by the participants during the interviews, to construct a comprehensive narrative. The figures in brackets represent factor item ranking. To illustrate, for F-1, (13: +3) indicates that Q-item 13 was ranked in the most agree position by the merged average of all informants loaded on this factor, while (7: −3) designates that Q-item 7 was ranked in the most disagree position.

F-1: No longer either/or thinking – a parallel language use is needed

A total of 17 participants loaded significantly on F1, accounting for 31% of the explained opinion variance. F-1 consists of a comparatively high percentage of customers (students from different colleges and levels, and parents), followed by suppliers (high school teachers and principals) and QU's employees (faculty and administrators), and finally, a global bank Qatari manager.

Participants loaded on this factor believe that no language should encroach upon another in QU. They strongly believe that QU should provide all learning and teaching resources as well as all policies and regulations in both Arabic and English (13: +3) & (14: +3). Here, the desired parallel use of Arabic and English is recognized not as an instrument for going global or competing in markets, but rather as a resource for enriching students’ academic experiences (11: +2). Participants loading on this factor believe that QU students from all disciplines should be given different mediums of instruction choices (12: +2). They strongly disagree with the commonly held views that English is unnecessary for QU students in social sciences and humanities colleges, both for their academic studies and future careers (19: −3) & (18: −2). Although participants loading on this factor believe that enforcing Arabic as the medium of instruction in QU is important for building bridges with the local community (1: +2), they do not support designating it as the only internal official language for reaching students and faculty (7: −3). As such, they believe that QU should not focus on hiring monolingual native Arabic faculty and administrators (6: −2). They are against activating a language in education policy that offers the Humanities programs in Arabic, while offering Sciences programs in English. They believe that such policy can negatively affect the communication between QU's different colleges (22: −2). In this sense, participants loaded on F-1 refuse the Bilingual Scientific Model and the Culturally Grounded Model. They seem to lean more towards the Competitive Bilingual Model, mainly if it ensures equal prospects for all QU's students, regardless of their majors, with the intention to enrich their academic experiences, regardless of the market imperatives.

F-2: English is important for the market and teaching sciences – let us not to forget

A total of 14 participants loaded significantly on F-2, accounting for 10% of the explained opinion variance. F-2 consists of a high percentage of customers (students from different colleges and levels, and parents), followed by suppliers (high school teachers and principals). In addition, an influential senior leader from QU's higher administration, and the Chief Executive Officer of Qatar Finance and Business Academy loaded on this factor.

Participants loading on this factor focused on the importance of English to the market and the teaching of Sciences in QU and seem to be cautioning against losing sight of the role and power of English. Thus, attracting English-speaking faculty to teach in QU's scientific colleges is their first priority (23: +3). Their eyes seem to be on markets when discussing QU's language in education policy. They strongly believe that adopting English as the medium of instruction in scientific colleges will meet the needs of the local market (17: +3). Alternatively, they agree with the possibility of offering parallel tracks in both Arabic and English to ensure meeting the community's needs of empowering the Arabic language (10: +2). They also seem to support giving students different mediums of instruction choices (12: +2). For participants loading on this factor, it is impossible to raise Arabic to be the sole vehicle of instruction in QU. A shortage of qualified Arabic-speaking faculty and the absence of adequate educational resources forbid such action as much as it might be desired. Hence, they oppose the Arabization of the sciences and related resources at QU. (4: −2). They suspect that QU students would prefer to study only in Arabic (3: −2), and they strongly contest the focus on recruiting monolingual native Arabic faculty and administrators in QU (6: −3). Therefore, they are against enforcing Arabic as the only official internal language used in QU to reach students and faculty (7: −2). Yet, participants loading on this factor seem to fall between two extremes. On the one hand, they believe that QU needs to activate a bilingual language policy that combines teaching Humanities programs in Arabic and teaching Sciences programs in English (21: +2). On the other hand, they seem to strongly disagree with the view that English is unnecessary for the academic success of students in the Humanities colleges (19: −3). In this sense, participants loading on this factor are against the Culturally Grounded Model and seem to be vacillating between the Bilingual Scientific Model and the Competitive Bilingual Model.

F-3: Let us improve language learning and teaching in QU- both in Arabic and English

A total of 10 participants loaded significantly on F-3, accounting for 7% of the explained opinion variance. F-3 consists of a comparatively high percentage of QU employees (faculty members from different colleges and academic rankings and administrators), followed by customers, suppliers and, finally, an influential Qatari businessman.

Participants loading on this factor seem to focus on the need for QU's students, from all disciplines, to have adequate linguistic competences in both Arabic and English. The emphasis here is on helping students develop and improve their bilingual linguistic abilities. For participants loading on this factor, the students majoring in the sciences may face the challenge of developing their English language proficiencies adequately while simultaneously learning academic content in English. As such, participants loading on this factor strongly believe that QU needs to attract English-speaking faculty to teach in its Sciences colleges (23: +3), on the condition that they are linguistically responsive. That is, they assist scientific major students to develop their English language skills, while studying the academic content. For participants loading on this factor, many instructors in QU have little or no preparation for providing such type of linguistic assistance. At the same time, participants loading on this factor dismiss the claim that Arabic is insignificant for scientific major students’ academic performance or career prospects (20: −2). They believe that QU students, from all disciplines, need more opportunities to improve their Arabic language (5: +2), through compact and intensive courses offered without augmenting degree course curricula. Still, participants loading on this factor vividly oppose considering English as unnecessary for Humanities students’ future careers (18: −3). They believe that QU must provide appropriate measures to enhance students’ exposure to both languages, such as providing all learning and teaching resources, as well as policies and regulations in Arabic and English (13: +2) & (14: +3). This desire of enabling QU students from all majors to be exposed to both languages drove participants loading on this factor to strongly oppose the focus on recruiting monolingual native Arabic faculty and administrators (6: −3) or assigning Arabic as the only official internal language in QU (7: −2). In this sense, participants loading on this factor are against the Culturally Grounded Model and the Bilingual Scientific Model and seem to accept the Competitive Bilingual Model, especially if it is developed with the aim to enhance the linguistic skills of QU's students from different colleges, and in both Arabic and English.

F-4: Arabic should come first, although English is important

A total of 9 informants loaded on F-4, accounting for 5% of the explained opinion variance. F-4 consists of a variety of QU stakeholders, among whom are three managers from the media and construction industries, and health sector. Interestingly, participants loading on this factor seem to disagree with the views that adopting English as the medium of instruction in the scientific disciplines at QU will meet the needs of the market (17: −2). They understand QU's language in education policy with reference to the aims of the Qatari national state. They believe in the responsibility of QU, as the primary national university in the country, in preserving and promoting the Arabic language. They strongly believe that adopting Arabic as the medium of instruction at QU will build bridges with the local community (1: +3). For them, this will undeniably lead to achieving Qatar National Vision 2030 of preserving the Arabic and Islamic identity (2: +3). They believe that QU's students, from all disciplines, need more opportunities to learn and improve their Arabic language skills (5: +2). They strongly reject the claim that Arabic is unessential for students in scientific majors, both for their academic success and career prospects (20: −3). At the same time, they seem to strongly advise QU to refrain from implementing a language in education policy that ignores the role English can play in Humanities students’ academic success (19: −3). They believe that QU needs to develop a language in education policy that serves the sentimental (identity-related) needs of students as well as their instrumental (practical-economic) requirements. They trust that offering parallel tracks in both Arabic and English could solve the dilemma, as it will not only ensure meeting the different needs of the university's stakeholders (10: +2), but will also lead to achieving linguistic justice in the Qatari society (9: +2). They believe that Arabic in Qatar is disadvantaged by the increasing role of English in different spheres. In such a situation, linguistic justice is not only desirable but also viable and achievable through the dedication of public institutions such as QU. Participants loading on this factor oppose adopting a language in education policy that differentiates between teaching Humanities in Arabic while teaching the Sciences in English (22: −2). In this sense, they voted against the Bilingual Scientific Model and the Culturally Grounded Model. They seem to favor the Competitive Bilingual Model, particularly if it works towards safeguarding the role of Arabic as the national language on the one hand, while on the other hand, introduces English as the medium of instruction in some majors.

Discussion

In general, results indicate strong agreement among the various perspectives taken by QU's stakeholders, with most of the differences being about the level of emphasis given to a few different Q-items. Such differences turned out to be significant in defining the perspectives among each other. Still, there also seems to be some disagreement among the participants on a few issues. In what follows, we highlight points of disagreement across perspectives, before outlining non-conformational points, which involve issues that were not consensual but also not in strong disagreement. Lastly, we discuss consensus points in details.

Points of disagreement

Participants seem to disagree on the purposes and effects of QU's medium of instruction. Both Q-items 1 and 17 articulate the views that address the relation between QU's choice of medium of instruction and wider societal and economic issues. Q-item 1, which is associated with the Culturally Grounded Model, enunciating the view that adopting Arabic, as the medium of instruction at QU shall build bridges with the local community, received different scoring across the emerging perspectives. It received positive scores by participants who loaded on F-1 and F-4. Yet, it scored a negative score in F-2, and around zero in F-3: (2, −1, 0, 3). Similarly, participants disagreed on Q-item 17, which relates to the Bilingual Scientific Model, expressing the view that adopting English as the medium of instruction in scientific disciplines shall meet the needs of the market. It received positive scores in F-2 and F-3. Yet, it received a negative score on F-4, and scored around zero in F-1 (0, 3, 1, −2). This may tell that QU's stakeholders conceptualize the role of the university as a social agent differently and therefore hold different expectations regarding the purposes and effects of its choices of the medium of instruction on the local market and community.

Non-conformational points

As for points that were not consensual but also not in strong disagreement with each other, an example can be found in Q-item 8, which expresses the view that non-Arab faculty and administrators at QU should have a minimum level of communication skills in Arabic. Participants loaded on F-1 seem to slightly agree, while participants loading on F-2 marginally disagree, whereas participants loading on both F-3 and F-4 appear to be neutral (1, −1, 0, 0). Another example of a non-confrontational point is Q-item 16, which articulates the view that industrial and commercial sectors could establish partnerships with QU through which they require the teaching in English in some specializations based on their needs. Participants loading on F-1 and F-4 seem to slightly disagree, while participants loading on F-2 seem to be somehow in favor of the idea, whereas participants loading on F-3 seem to be neutral (−1, 1, 0, −1). Through not being either negatively or appositively assertive regarding both Q-items, it seems that there is a shared sense among participants that these topics are less important than other issues.

Consensus points

On the one hand, all perspectives gave low scores to statements that suggest monolingual practices, such as Q-items 6, 7, 18, and 19. Both Q-items 6 and 7 relate to the Culturally Grounded Model. Respectively, they express the subjective opinions on whether QU's should focus on recruiting monolingual native Arabic faculty and administrators, and whether Arabic should be designated as the only internal official language in QU used to reach students and faculty. Both items received negative scores in the four emerging perspectives: (−2, −3, −3, −2) and (−3, −2, −2, −1). Whereas Q-item 18, which associates with the Bilingual Scientific Model, concerning the commonly held view that QU's graduates from Humanities colleges often work in careers that requires only Arabic, received strong negative scores in three perspectives: F-1, F-2 and F-3, suggesting rejection, and scored around zero in F-4, suggesting neutrality (−2, −1, −3, 0). Another area of ‘consensus against’ is Q-item 19, which associates with the Bilingual Scientific Model, articulating the commonly held view that QU's Humanities students do not need English for their academic studies. While the existing literature refers to a characteristic divide made in non-Anglo-Saxon universities between teaching Sciences in English, and Humanities in the local language(s) (e.g. Hultgren et al., Citation2014; Annamalai, Citation2010), to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the acceptability of such divide among stakeholders. The results of this study indicate that, in the context of QU, such a divide is unanimously repudiated (−3, −3, −1, −3).

On the other hand, participants agree with statements that insinuate the need for Arabic and English to be used productively side by side. This includes Q-items 15 and 10. Both Q-items associated with the Competitive Bilingual Model. For Q-item 15, which expresses the view that QU needs to recruit bilingual academic staff in all disciplines, participants from different QU's stakeholders’ categories reached a striking consensus: (1, 1, 1, 1). Q-item 10, is another example of a consensus among QU's stakeholders: (1, 2, 1, 2). It articulates the need to offer parallel tracks in both Arabic and English in QU, to ensure meeting the different needs of the university's stakeholders.

Based on the above, neither Arabic medium for all nor English medium for a few is a desirable educational language policy for QU's different stakeholders. This leaves the option for a language in education policy that seeks to manage the relationship between Arabic and English in a parallel way.

The development of parallel language use policy is a project that requires considerable organizational commitment. Parallel language use does not entail the reduplication of all teaching and learning activates undertaken in a university in two languages (i.e. in the context of QU, all subjects taught in Arabic should also be offered in English and vice versa). Rather it implies the need to create a harmonious existence between local and global language(s). At QU, this can start with developing an explicit language policy for the university as a whole, a crisp text that communicates QU's corporate identity and brand and provides a convincing rationale for its commitment to both Arabic and English. Such language policy should be integrated with QU's internationalization policy, linked to the Qatari state's regulations issued to promote Arabic as the national language and reflect the role of the QU locally and regionally. Such policy should be developed based on Needs Analysis of study disciplines and of students’ future employment. Such a policy should also lead to practical applications through which QU needs to provide linguistic support in both Arabic and English to students and faculty. Support provided should be reviewed on a regular basis. The level of support may be increased or decreased for any particular language if certain conditions are met. Support with students’ language proficiency development is needed at all levels (BA, MA, Ph.D.). Students’ language proficiency needs assessment at each level, and QU needs to develop its tests of proficiency in both Arabic and English. The time allocated for teaching in both Arabic and English should be handled flexibly at each level. As for faulty, they need to be well trained linguistically, culturally, and pedagogically. When recruiting academic staff, consideration needs to be given to whether a potential lecturer/professor has personal experience of foreign/second language learning and appreciates the need to foster this among students.

Limitations

The data analysis in this study centered on revealing how QU's stakeholders perceive the three educational language policy options proposed by the White Paper. There was little explanation provided concerning why participants of each stakeholder category perceive the situation as they do. While the demographic information collected could have allowed for an explanation regarding the why aspects, space limitation led to focus on the how aspects. Thus, this study should be seen as exploratory. That is, it was conducted to have a better understanding of the existing problem and not to provide conclusive results. However, we hope that this study inspires scholars working in the language policy field to undertake similar studies so that a more comprehensive picture can emerge regarding language in education policies in higher education in the region.

Final remarks

Through Q-methodology, this study attempted to reveal the social acceptability of three educational language policy options proposed to tackle pressing linguistic needs and priorities in QU. The results indicate that the emerging perspectives of the university's stakeholders paid less attention to English as a monster and more attention to English as a mate, less attention to the nativeness as a benchmark for language use in educational contexts, and more attention to pragmatic sociolinguistic practices in an internationalized era. We conclude this paper by arguing that the involvement of various stakeholders in the making of language in education policies legitimizes their creation. Miranda et al. remind us ‘the democratic structures of public universities include mechanisms for the wide participation of potential policy agents at different levels of the micro-context’ (Citation2018, p. 219). It is therefore the responsibility of those in top-level positions to facilitate such participation, and those at the bottom level to (re)claim role. A democratic construction of language in education policy may take longer, but the enrichment and validation achieved deserve going the extra mile. In this perspective, the discussion and decision-making process about language in education policy must be shared and augmented between policymakers and stakeholders in a continuous top-down and bottom-up movement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Dr Hadeel Alkhateeb is an Assistant Professor in the College of Education at Qatar University. She received an MA in Translation Studies in the Arabic Israeli conflict from Salford University. Her Doctorate degree is from University College London where she researched the impact of neoliberalism on Qatar’s language policy and language planning. She does research in educational language policy, the Sociolinguistics of Higher Education, Language Planning and Policy, and Language Policy Evaluation.

Dr Muntasir Al-Hamad is a specialist in comparative Semitic Languages syntax and grammar, and is highly interested in applied and socio-linguistics. He teaches Arabic at the Arabic for Non–Native Speakers Center at Qatar University, after he worked as the director of Amstone Project on Abrahamic Religions at the University of Manchester, as well as a lecturer of Arabic and Oriental Studies at the Manchester Metropolitan University. He is also directly involved in many research, training, and consultancy responsibilities in Qatar and abroad.

Dr Eiman Mustafawi is an Associate Professor of Linguistics at Qatar University. Her research interests range from Arabic phonology and language production in healthy and linguistically impaired populations to sociolinguistics and issues of Bilingualism. She has numerous publications in theoretical and applied Linguistics including studies in clinical linguistics and language policies. She obtained her PhD from University of Ottawa in Canada in 2006. She has assumed a number of administrative posts between 2007–2016 including the position of the Dean of Arts and Sciences and has been a visiting scholar at Pembroke College and the Centre for Islamic Studies at Cambridge University, UK, during 2016–2017.

ORCID

Eiman Mustafawi http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5271-9461

Notes

1 See THE website: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/how-qatar-university-became-most-international-institution-world.

2 We acknowledge here that while universities of the past reflected their cultural and national settings, an internationalist impulse had always run deep. As Lo Bianco (Citation2010) noticed, ‘Knowledge cannot easily be confined within bounded geopolitical spaces, and the technical skill and philosophical reflection that universities produce stimulates cross-border markets for their exchange’ (p. 38). In such case, ‘A shared medium of instruction and standardized literacy [have been always] indispensable for the possibility of international education, even when the language concerned does not retain a home base in any nation’ (Lo Bianco, Citation2010, p. 38).

References

- Annamalai, E. (2010). Medium of power: The question of English in education in India. In J. Tollefson, & T. Amy (Eds.), Medium of instruction policies: Which agenda? Whose agenda? (pp. 177–194). Routledge.

- Baik, C., & Greig, J. (2009). Improving the academic outcomes of undergraduate ESL students: The case for discipline-based academic skills programs. Higher Education Research and Development, 28(4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903067005

- Barnett, R. (1994). The limits of competence: Knowledge, higher education and society. The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Barnett, R. (2012). The future university: Ideas and possibilities. Routledge.

- Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity. Yale University Press.

- Brown, S. R. (2008). Q methodology. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 2, pp. 699–702). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. http://www.yanchukvladimir.com/docs/Library/Sage

- Chen, S., & Lo, L. (2012). The trajectory and future of the idea of the university in China. In R. Barnett (Ed.), The future university: Ideas and possibilities (pp. 50–58). Routledge.

- Coleman, J. (2013). Forward. Multilingual matters. In A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster, & J. M. Sierra (Eds.), English-medium instruction at universities: Global challenges (pp. xiii–xv). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Cots, J., Llurda, E., & Garrett, P. (2014). Language policies and practices in the internationalization of higher education on the European margins: An introduction. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874430

- Crandall, J., & Bailey, K. (2018). Global perspectives on language education policies. Routledge.

- Dryzek, J. S., & Berejikian, J. (1993). Reconstructive democratic theory. American Political Science Review, 87(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938955

- Garrett, P., & Gallego Balsà, L. (2014). International universities and implications of internationalization for minority languages: Views from university students in Catalonia and Wales. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874434

- Gill, S. (2010). Medium of instruction policy in higher education in Malaysia: Nationalism versus internationalization. In J. Tollefson & T. Amy (Eds.), Medium of instruction policies: Which agenda? Whose agenda? (pp. 135–152). Routledge.

- Haberland, H. (2005). Domains and domain loss. In B. Preisler, A. Fabricius, H. Haberland, S. Kjærbeck, & K. Risager (Eds.), The consequences of mobility (pp. 227–237). Roskilde University.

- Harder, P. (2008). What is parallel language use? Retrieved October 15, 2019 from http://cip.ku.dk/om_parallelsproglighed/oversigtsartikler_om_parallelsproglighed/hvad_er_parallelsproglighed/

- Henkel, M. (2010). Change and continuity in academic and professional identities. In G. Gordon & C. Whitchurch (Eds.), Academic and professional indefinites in higher education (pp. 3–12). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244

- Hultgren, A. (2014). English language use at the internationalized universities of Northern Europe: Is there a correlation between Englishisation and world rank? Multilingua, 33(3-4), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0018

- Hultgren, A., Gregersen, F., & Thøgersen, J. (2014). English in Nordic Universities: Ideologies and practices. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- International Institute of Business Analysis. (2017). IIBA global business analysis core standard: A companion to a guide to the business analysis body of knowledge- Version 3. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. https://publications.iiba.org/public/IIBA_Global_BusinessAnalysis_CoreStandard.pdf

- Kamal, S., Kocor, M., & Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. (2014). Quantifying human subjectivity using Q method: When quality meets quantity. Qualitative Sociology Review, 10, 60–79. http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/ENG/Volume30/QSR_10_3_Kamal_Kocor_Grodzinska-Jurczak.pdf

- Lasagabaster, D. (2015). Language policy and language choice at European Universities: Is there really a ‘choice’? International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2014-0024

- Lazdowski, K. A. (2015). Stakeholders’ roles in education language policy research in West Africa: A review of the literature. Reconsidering Development, 4(1). http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/reconsidering/vol4/iss1/1

- Liddicoat, A. (2018). Language planning in universities: Teaching, research and administration. Current Issues in Language Planning, 17(3-4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2016.1216351

- Lo Bianco, J. (2010). The importance of language policies and multilingualism for cultural diversity. International Social Science Journal, 61(199), 37–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2010.01747.x

- Lo Bianco, J. (2015). Exploring language problems through Q-sorting. In F. M. Hult, & D. C. Johnson (Eds.), Research methods in language policy and planning: A practical guide (pp. 69–80). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lundberg, A. (2019). Teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform concerning multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Learning and Instruction, 64, 101244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244

- Miranda, N., Matha, B., & Harvey, T. (2018). Conflicting views on language policy and planning at a Colombian university. In A. Liddicoat (Ed.), Language planning in universities: Teaching, research and administration (pp. 203–219). New York.

- Morley, L. (2010). Professional lecture ‘imagining the university of the future’. Retrieved January 25, 2020. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/newsandevents/sussexlectures/louisemorley.php

- Morley, L. (2012). Imagining the university of the future. In R. Barnett (Ed.), The future university: Ideas and possibilities (pp. 26–35). Routledge.

- Mortensen, J. (2014). Language policy from below: Language choice in student project groups in a multilingual university setting. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874438

- Murray, N. (2014). Reflections on the implementation of post-enrolment English language assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2013.824975

- Nordic Council. (2007). Deklaration om nordisk språkpolitik. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-607

- Phillipson, R. (2018). Forward. In R. Barnard & Z. Hasim (Eds.), English medium instruction programmes: Perspectives from South East Asian Universities (pp. xiii–xv). New York: Routledge.

- Preisler, B. (2009). Complementary languages: The national language and English as working languages in European universities. In P. Harder (Ed.), English in Denmark: Language policy, internationalization and university teaching (pp. 10–28). Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Qatar National Development Strategy 2011–2016. (2011). Qatar general secretariat for development planning. Doha, Qatar. http://www.gsdp.gov.qa/gsdp_vision/docs/NDS_EN.pdf

- Qatar’s Third Human Development Report. (2012). Expanding the capacities of Qatari youth: Mainstreaming young people in development. http://www.youthpolicy.org/library/wp-content/uploads/library/2012_Qatar_Human_Development_Report_Eng.pdf

- Qatar University. (2016). The white paper. Doha, Qatar.

- Qatar University. (2019). Student satisfaction survey. Doha, Qatar.

- Schmolck, P. (2014). PQMethod. Release 2.35. Retrieved August 16, 2019 from http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de/qmethod/downpqmac.htm

- Soler, J., & Gallego-Balsà, L. (2019). Language policy, internationalisation, and multilingual higher education: An overview. In J. Soler & L. Gallego-Balsà (Eds.), The sociolinguistics of higher education (pp. 17–41). Cham: Palgrave Pivot.

- Stenner, P., & Rogers, R. (2004). Q methodology and qualiquantology: The example of discriminating between emotions. In Z. Todd, B. Nerlich, S. McKeown, & D. D. Clarke (Eds.), Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice (pp. 101–120). Psychology Press.

- Stephenson, W. (1989). The study of behaviour: Q- technique and its methodology. University of Chicago Press.

- Villares, R. (2019). The role of language policy documents in the internationalisation of multilingual higher education: An exploratory corpus-based study. Languages, 4(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4030056

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Sage.

- Wazen, C. (2016). How Qatar University became the most international institution in the world. The World Rankings. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/how-qatar-university-became-most-international-institution-world

- Webler, T., Danielson, S., & Tuler, S. (2009). Using Q method to reveal social perspectives in environmental research. Social and Environmental Research Institute. www.serius.org/pubs/Qprimer.pdf