ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the motivations behind the implementation of bilingual education in the Dutch preschool system and relates this to the status of Dutch in the Dutch educational system. Based on the analysis of policy documents and questionnaires filled in by parents and teachers, this study reveals two different underlying ideologies that the government, daycares and parents have adopted. The ideology of the Dutch government and daycare organizations visited by a Dutch-speaking audience is centered around Dutch-speaking children acquiring English as a foreign language. On the other hand, non-Dutch speaking parents and daycare organizations visited by an international audience rather want to expose non-Dutch speaking children to Dutch, to facilitate better integration into the Dutch community. The data thus suggest that not only English but also Dutch is important for many parents. Still, the introduction of bilingual daycares is part of an ongoing ‘Englishization’ of the Dutch educational system that has been taking place for decades. Future research should determine what a larger scale introduction means for the status of the Dutch language in the Dutch preschool system in the long run.

Introduction

In the Netherlands, being fluent in a foreign language in addition to Dutch is considered an asset. Foreign language learning is promoted in the Dutch educational system: in secondary education, all pupils learn English, and in the lower years of secondary education the acquisition of German and French is also compulsory. Whereas pupils’ interest in German and French is decreasing (Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen, Citation2018), the role of English has become more prominent in Dutch society.

The role of the English language has become increasingly bigger after two world wars, and due to globalized pop culture English has firmly established itself in Dutch society (Edwards, Citation2016, p. 16). Nowadays, English is often used as a working language or second language next to Dutch in areas such as commerce and popular culture (Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen, Citation2018); and Ammon and McConnell (Citation2002) have argued that English might be considered a national second language. The English language has taken on functions in education, business and media that ‘cannot be attributed merely to the accommodation of foreigners’ and a sound knowledge of English is considered essential in Dutch students’ future work lives, both nationally and internationally (Edwards, Citation2016, p. 66).

While concerns have been raised about the status and use of Dutch due to the prominent position of English (for an overview, see Nortier, Citation2011), English is gaining ground in the Dutch educational system. This ‘Englishization’ (a term coined by Earls, Citation2013) of the Dutch educational system has already left its marks in primary and secondary education: bilingual Dutch-English primary and secondary schools are becoming increasingly popular (Edwards, Citation2016, p. 28) and in 2017, the Dutch government proposed to introduce bilingual education into the Dutch preschool system (Staatsblad Citation249, Citation2017). As part of a pilot study, bilingual curricula using English, French or German as an additional language next to Dutch could be implemented into Dutch preschool education. However, none of the participating daycare centers opted for German or French.Footnote1 By implementing Dutch-English bilingual curricula into the preschool system, effectively a fully bilingual track in the Dutch education system is created, running from zero to eighteen. Afterwards, one can choose to enroll in a Dutch or one of many English taught bachelor programs in higher education.

This paper will delve deeper into the motivations behind the implementation of bilingual input in Dutch preschool education. Based on an analysis of collected policy documents and questionnaires filled in by parents and teachers, this study aims to uncover the ideologies that underlie the initiative to introduce bilingual Dutch-English education into the Dutch preschool system. What is the ideology behind this initiative? And what does this tell us about the status of the two languages in bilingual preschools in the Netherlands?

Background

Ideologies in bilingual education

Bilingual education is a simplistic label for a phenomenon that can be manifested in a variety of ways. The term has been used to refer to many different sorts of education in which different languages are implemented. For example, it is not only used to refer to a classroom in which formal instruction is used to foster bilingualism, but also to a classroom where bilinguals are present.

In different types of bilingual education, the status of the two languages involved shapes the way bilingual input is implemented. The way in which bilingual education is designed is thus a reflection of the roles that these languages play in society on a cultural, social and political level and reflect the language ideologies that are present in society (Spolsky, Citation2004). Language ideologies are the different ways people think about language and how it should be used (Silverstein, Citation1979). These thoughts about language are a product of cultural, political and moral interests; they are socially constructed and ‘constructed in the interest of a specific social or cultural group’ (Kroskrity, Citation2004, p. 501).

The term language ideologies are often used interchangeably with language attitudes since both involve speakers’ feelings and beliefs about language and language use (Kroskrity, Citation2018). While some consider the terms to be indistinguishable, others assume that language attitudes can offer a window into understanding the status of languages in society and the underlying ideologies, since language attitudes could be dominated by ideological positions present in society (Dyers & Abongdia, Citation2010). Within this view, studying language attitudes thus provides insight into language status and underlying ideologies.

Language ideologies are translated into language policies once ‘a person or a group seeks to impose their language ideologies on others through management of others’ language’ (Bernstein et al., Citation2018, p. 458). Language policies thus reflect underlying ideologies and can be carried out through different kinds of management (Spolsky, Citation2004). Policies can be carried out through de jure management (explicit plannings and interventions) and de facto management (implicit social practices). Consequently, studying language ideologies in education entails studying language policies in a classroom context, which in turn involves studying language management (de jure and de facto).

Underlying ideologies are thus not only reflected in how the bilingual programs are designed, but also in their societal and educational aims, and for whom the forms of bilingual education are designed. Whether education is considered bilingual in the literature is not only determined by the languages offered in the classrooms but also by students and their language backgrounds (Baker, Citation2011; García & Wei, Citation2014). The different forms of bilingual education can thus be distinguished by the following key dimensions: (1) how it is organized, (2) who the target audience is, (3) what the societal and educational aim is, and (4) the status of the languages involved. This subsection will discuss various forms of bilingual education in relation to these four key dimensions: monolingual, weak prestigious, strong prestigious and translanguaging forms of bilingual education.

Forms of education that involve groups consisting of students with non-native language backgrounds are often categorized as being monolingual forms of bilingual education (Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). The societal aim is then to immerse these non-native speakers in the majority language (Baker, Citation2011). Baker (Citation2011) states that the overall aim of these monolingual forms of bilingual education is not to create bilingual speakers, but rather competent monolingual speakers of the more prestigious majority language.

Types of bilingual education that involve languages of children from immigrant homes should be distinguished from types of bilingual education that involve educational elites. The latter involve languages that have a high degree of cultural prestige (Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). These forms of bilingual education have been labeled prestigious bilingual education (García & Wei, Citation2014). These prestigious forms of bilingual education can be implemented in different ways: some of which have been considered weak in the literature, while others are thought to be strong (Baker, Citation2011).

In weak forms of bilingual education large parts of the curriculum are offered in the majority language to which some foreign language teaching of a second prestigious language is added (Baker, Citation2011). The second language is not necessarily used as a medium of instruction, but the main focus is rather on language learning of that second language. This type of bilingual education mostly leads to a limited knowledge of a foreign language (Baker, Citation2011). However, Baker (Citation2011) notes that when economic circumstances encourage the acquisition of a particular second language with power (such as English in the Netherlands), a weak form of bilingual education might be fruitful.

In so-called strong forms of bilingual education two languages with power can serve as a medium for classroom communication and teaching, rather than being taught as separate foreign language teaching subjects (Baker, Citation2011). The aim of such forms of bilingual education is to create competent bilingual speakers of both languages. Cummins (Citation2008) claims that these types mostly stem from the idea that the two languages should be kept apart at all times, either by subject, time or teacher. Within this approach, switching between languages and language is often stigmatized and not considered helpful, since it is assumed that this might lead to confusion and disturb distinct separation of the languages.

The most common way to establish boundaries between the two languages in strong forms of bilingual education is by separating the two languages by teacher, the so-called ‘one person-one language’ principle (henceforth: OPOL) (Ronjat, Citation1913). This approach requires the presence of two teachers in the classroom, one of whom communicates consistently in one language and one in the other. By using this approach, students are conditioned to associate one language with a specific person. It is believed that this reduces chances of mixing the two languages (Baker, Citation2011).

The aforementioned forms of bilingual education have in common that they seem to be built upon the assumption that the language groups are homogeneous (García & Wei, Citation2014, p. 50), such as language minority students having to learn a majority language (monolingual forms) or language majority students learning a high-prestige foreign language (prestigious weak and strong forms of bilingual education). García and Wei (Citation2014) instead state that bilingualism classrooms are filled with speakers of different origins, characteristics and experiences. Also, while supporters of the OPOL-principle believe language mixing to be unhelpful and undesirable, García and Wei (Citation2014) claim that there is plenty of empirical evidence that in bilingual classrooms, both teachers and students switch between languages very often to teach and learn.

For these reasons, García and Wei (Citation2014) introduce the concept of translanguaging: instead of talking about an L1 and L2, the relationship between the two languages should be reinforced. Translanguaging is defined by Canagarajah (Citation2011) as ‘the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system’ (p. 401). For bilingual education this would mean that all languages of all students and teachers are integrated inside the classroom without boundaries and separations, allowing students to draw from all of their language skills (in two or more languages), rather than inhibiting and constraining these language skills to monolingual instructions and practices (García & Wei, Citation2014). Furthermore, in the aforementioned forms of bilingual education (monolingual, weak and strong), the amount of time spent on the languages generally depends on the status of the languages: if two languages of power are involved, both are typically allowed to be present (weak and strong forms), if one language of power is involved, only this language tends to be allowed (monolingual forms). In the translanguaging forms of bilingual education however, all languages are welcome, irrespective of status (García & Wei, Citation2014). See for an overview of the different forms of bilingual education in relation to the four key dimensions.

Table 1. Overview of forms of bilingual education.

This overview illustrates that the different ways in which bilingual education can be designed resonate with different underlying attitudes towards and ideologies about the two languages concerned. One of the goals of this study is to uncover the underlying ideologies of the initiative to introduce Dutch-English bilingual education into the Dutch preschool system by describing this initiative in relation to the four key dimensions listed in . Because the initiative fits into a wider trend of Dutch-English bilingual education, the next subsection will discuss the role of the English language in Dutch society and education.

The role of English in Dutch education

Out of the 25 member states of the European Union, inhabitants from the Netherlands are most likely to speak English as a foreign language: in the Special Eurobarometer 386, 90% of the respondents in the Netherlands indicated to speak English (European Commission, Citation2012). This could be attributed to the role of English in Dutch education: according to Ammon and McConnell (Citation2002), the Netherlands is ‘one of the most advanced countries in Europe concerning the integration of instruction of English in the national education system’ (p. 99).

Today, the English language has integrated the most in Dutch higher education. Over the years, a large part of Dutch curricula in higher education switched to English because of ‘the commodification of education and competition between universities’ (Edwards, Citation2016, pp. 31–32). Proponents claim that students from abroad have no intention to learn Dutch, thus offering curricula in English constitutes a big selling-point for Dutch universities. Nowadays, out of all non-English speaking countries, the Netherlands offers the highest number of English-taught programs in higher education in Europe (Wächter & Maiworm, Citation2008). A growing number of bachelor's programs are being taught only in English, as well as approximately 70% of the master's programs (Nuffic, Citation2017, p. 14). Still, opponents claim it might lead to a decrease in educational quality and drive a wedge between an elite and the rest of the Dutch population (Adam, 2012; as cited in Edwards, Citation2016).

In secondary education, the introduction of bilingual Dutch-English programs in 1990 was met with little criticism. Up until then, English had already been a compulsory subject in all streams of secondary education (corresponding to the previously discussed prestigious weak forms of bilingual education). The decision to offer bilingual secondary education was a bottom-up decision, mostly driven by parents and teachers who believed that proficiency in English would benefit the children's education and socioeconomic status (Edwards, Citation2016, p. 29). The Ministry of Education set three main criteria to the implementation of bilingual curricula in Dutch secondary schools, which are still effective today. First, schools are allowed to teach no more than 50% of the total number of lessons in English. Second, the Dutch curriculum has to be followed. Third, bilingual programs may not come at the expensive of Dutch language proficiency (Admiraal et al., Citation2006, p. 77). Bilingual secondary education is usually offered in lower years of secondary education (age group 12–15 years). English is used as a medium of instruction (using the CLIL method: Content and Language Integrated Learning) in a variety of subjects (Admiraal et al., Citation2006), a system that corresponds most to the aforementioned prestigious strong forms of bilingual education. In the last two years of secondary education, Dutch is often used as a medium of instruction instead of English, since parents want their children to have a Dutch preparation for the Dutch school leaving exams (Admiraal et al., Citation2006).

Bilingual secondary education was explicitly intended for Dutch children who are raised monolingually at home and to enhance Dutch pupils’ opportunities in education and on the national and international job market. Some worry that these bilingual tracks might only attract an educational elite (Sieben & Van Ginderen, Citation2014; Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). Despite these worries, the number of bilingual tracks in secondary education in the Netherlands is still growing (Sieben & Van Ginderen, Citation2014). Nowadays, bilingual curricula are implemented in all streams of secondary education (vmbo, havo and vwoFootnote2). In 2021, 130 secondary schools in the Netherlands are a part of netwerk tto (tweetalig onderwijs ‘network bilingual education’) and were reported to offer bilingual curricula (Nuffic, Citation2021).

In primary education a similar movement towards bilingual education is taking place. In 1986, English was introduced as a mandatory subject into Dutch primary education for groups 7 and 8 (i.e. pupils aged 11 and 12) and over the last two decades, an increasing number of Dutch primary schools have implemented English in their curricula in lower groups by means of early foreign language education, known as vvto (vroeg vreemdetalenonderwijs ‘early foreign language education’) in the Netherlands. Vvto is a prime example of what Baker (Citation2011) would classify as a prestigious weak form of bilingual education: large parts of the curriculum are offered in the majority language (Dutch), to which some foreign language teaching of English is added, typically by means of games and singing for a maximum of three hours a week starting at age four (Nortier, Citation2011). The number of schools offering vvto rose from 20 in 1999 (Taalunieversum, 2006; as cited in Edwards, Citation2016) to 1212 out of 6808 schools in 2018 (Nuffic, Citation2018).

Similar to the initiative in secondary education, the increase in foreign language teaching at primary school was mainly driven by parental demand. Even though the government promotes vvto in primary schools, there have been some concerns about this development: opponents believe that the time spent on English will be at the expense of time spent on Dutch (De Korte, Citation2006), which would lead to deficiencies in both languages for children from immigrant families (Appel, Citation2003). Despite such criticisms, early English foreign language teaching has become increasingly popular in Dutch primary education: in 2013 the government announced a pilot study into bilingual primary education, known as tpo (tweetalig primair onderwijs ‘bilingual primary education’). This pilot study allows 17 primary schools to teach up to 50% of the time in English. This 50% maximum is considerably higher than the maximum of three hours a week that is currently permitted.

As part of this pilot study, Jenniskens et al. (Citation2018) investigated the ways in which bilingual curricula were implemented. Results showed that the majority of schools used the OPOL-principle to implement a bilingual curriculum, corresponding to prestigious strong forms of bilingual education. Also, both parents and teachers had positive attitudes towards early English language teaching in Dutch primary schools. Bilingual primary education thus seems to continue to make progress, not only due to government support, but also due to parental demand and positive views on bilingual primary education.

Current study

Similar to developments in primary education, in 2017, the Dutch government proposed a pilot study for the introduction of bilingual education into the Dutch daycare system. This paper reports on data collected in this pilot study, called Project MIND (Multilingualism in Daycare), in which participating daycare centers were allowed to offer either English, German or French in addition to Dutch. Before the start of this pilot study, daycare centers were only allowed to offer other languages next to Dutch (1) if this was a commonly used regional language, and (2) if the daycare's audience mainly consisted of highly skilled migrant workers (in the document referred to as ‘expats’) (Staatsblad Citation249, Citation2017, p. 5).

In the Netherlands, daycare centers offer care for children between zero to four years. Some daycares have special groups for babies or toddlers (so-called horizontal groups), whereas other combine the age groups (vertical groups). Usually, on all groups, at least two staff members are present, since the ratio of children per staff member ranges from 1:4 (0–2 years) to 1:8 (2–4 years).

All participating organizations in the pilot study choose to offer English. This illustrates the prominent role of English in Dutch society and education, as previously discussed. They were free to design their bilingual input, as long as they did not exceed the maximum of 50% of the allowed English input. In total, ten daycare organizations signed up for this pilot study, with eighteen locations in different parts of the country. Not all daycare organizations were fully bilingual, some offered bilingual education only to one of their groups. In total, 35 bilingual groups (including their children, parents and teachers) participated in the pilot study.

This study seeks to uncover the ideology behind this initiative to introduce bilingual Dutch-English education into the Dutch preschool system. To do so, this study will focus on language policies of the daycare centers and attitudes towards the two languages to investigate the status of the two languages, since ideologies are reflected in language policies and attitudes towards the two languages involved (Bernstein et al., Citation2018; Dyers & Abongdia, Citation2010).

This study will make use of qualitative as well as quantitative methods. First, policy documents will be analyzed, such as the official announcement of the pilot study by the Dutch government to determine the societal and educational aims. The daycares’ policy plans will be analyzed to gain further insight into de jure management. Second, this study relies on teacher questionnaires to investigate de facto language management (Spolsky, Citation2004). Third, to further understand the audience and their attitudes towards the languages involved, parental questionnaires will be used.Footnote3

In doing so, the initiative will be discussed in relation to the aforementioned key dimensions along which different forms of bilingual education can vary and will answer the following research questions: (1) how is the bilingual input organized (de jure and de facto management), (2) for whom is bilingual preschool education intended (and who, in reality, visit Dutch-English daycares?), (3) what is the societal and educational aim of this initiative, and (4) what is the status of the languages involved?

Method

To uncover the ideology behind this initiative, data collection was accomplished in a variety of ways. This study relies on collected documents such as policy plans, a teacher questionnaire and parental questionnaire.

Policy documents

In 2017, the Dutch government announced the pilot study on the implementation of bilingual programs in Dutch daycare in the Dutch Staatsblad. This document, consisting of 21 pages, is an official publication of changed laws and an official notice of the pilot study. Since ideologies are constructed in the interest of a social or cultural group (Kroskrity, Citation2004), to unravel the government's aims and ideology, the document was analyzed on (1) reasons for implementing a bilingual program into Dutch preschool education, and (2) the intended target audience.

In addition, pedagogical policy plans from all participating daycare centers were analyzed. All daycare organization in the Netherlands are required to have a pedagogical policy plan, in which they elaborate on their views on four pedagogical matters: (1) how emotional safety is guaranteed, (2) how the development of personal skills is promoted, (3) how the development of social skills is promoted, and (4) how the transfer of values and standards take place. Also, if any bilingual input is offered, daycare organizations are required to elaborate on its implementation and organization in their policy plans.

At the start of the pilot study, all participating daycare centers provided their pedagogical policy plans. The length of the plans ranged from 14 to 50 pages. Pedagogical policy plans from all participating organizations (ten in total) were analyzed on two aspects: (1) reasons for implementing a bilingual language program (educational aims), and (2) how the two languages are implemented in their daily routines (de jure management).

Teacher questionnaire

The teacher questionnaire served to gain further insight into de facto management. This questionnaire contained a total number of 17 questions about topics such as language switching, as well as language proficiency in Dutch and English, content of conversations inside the classroom and the organization's general communication practices. For each organization, this questionnaire was filled in on paper by the Dutch-speaking and English-speaking teachers who worked most often at the participating groups, and thus had the most knowledge of the organization's language strategies and the bilingual input being offered. In total, 47 teachers filled in this questionnaire. To investigate de facto management, only the answers to questions on language switching and language proficiency were used.

Parental questionnaire

Parents were asked to fill out a questionnaire on their child's language development and language proficiency, weekly schedules, as well as questions about language input offered at home, content of conversations at home, switching between languages and language mixing. The questionnaire's length was dependent on the number of languages spoken at home. To elicit more information on the children's demographic background, questions about language proficiency and language backgrounds of the parents were included, as well as questions about their educational backgrounds, reasons for choosing bilingual daycare and questions about the attitudes towards Dutch and English.

The parental questionnaire was created by using Easion Survey version 3.107 (Parantion, Citation2017) and was sent by e-mail. Parental questionnaires were filled out and completed for 236 children in total. In this study, only the information on the language background, educational background, motivations and attitudes is included.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed in two different ways. For the policy documents relevant passages were noted down and analyzed qualitatively. These were passages in which reasons for bilingual implementation of bilingual programs and/or (targeted) audiences were discussed. In addition, for the pedagogical policy plans, passages that mentioned the way bilingual input was implemented were also marked to gain further insight into de jure management.

Data from the questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively. Since answers to the questions on language switching used from the teacher questionnaires were multiple choice closed-ended questions, no pre-processing of the data was necessary. Parental questionnaire data also partly consisted of answers to multiple choice-close-ended questions (questions on language and educational backgrounds). However, questions on the parents’ motivations and attitudes were all open questions. Answers to these questions were coded into different categories that were developed inductively from the data.

Results

Results will be presented in light of the four key dimensions along which different forms bilingual education can vary. This section begins by discussing the organization of bilingual input (de jure and de facto) and it will then go on to discuss the aims, (intended) audience and attitudes towards Dutch and English.

Organization of bilingual input

De jure management

The daycare organizations had different ways of implementing bilingual input into their daily routines: according to the policy documents, six out of ten daycares implemented the OPOL-principle where one teacher only spoke Dutch and the other only spoke English. At all times, two teachers were present inside the classroom. This would typically result in an approximately fifty-fifty language distribution where a clear separation between the two languages is made by linking one language to one person, responding to strong forms of bilingual education as formulated by Baker (Citation2011).

Whereas the majority of daycare centers opted for an OPOL-principle, one daycare organization chose a slightly different approach. In its policy document, it mentioned that one teacher only spoke Dutch, whereas the other switched between Dutch and English. This daycare organization reported this teacher to be using Dutch and English throughout all activities during the day. This means that no clear boundary between languages was set and children attending this organization would typically be less exposed to English during the day than children attending organizations in which an OPOL-principle is implemented.

According to the policy plans, three organizations opted for a system that resembled early foreign language instruction the most (and thus responding to weak forms of bilingual education), only offering English language input during set times of the day. In these organizations, English was not necessarily used as a medium of instruction for teaching or for basic classroom communications, but rather as a separate subject on its own. Two of these organizations adopted English foreign language instruction methods created for preschool: Groove.Me (Blink Engels, Citationn.d.) and Benny's Playground (Early Bird, Citationn.d.). One organization adopted the so-called sandwich-method during snack time, in which every English sentence was consequently translated in Dutch and then back to English (English-Dutch-English, resembling a sandwich).

De facto management

To gain insight into de facto management, the language use of staff members inside the classroom was examined more closely by means of a questionnaire. In response to a closed question if they would adapt their language choice, 27 teachers out of 47 teachers who filled in the questionnaires about language input indicated they would indeed adapt their language choice to the children's needs, and therefore switch between languages. The questionnaire also contained multiple choice closed-ended questions on language proficiency in Dutch and English. Results showed that the Dutch-speaking teachers reported to have advanced, beyond advanced or perfect proficiency in English (76%) and the English-speaking teachers in Dutch (67%). This means that, in theory, the majority of Dutch- or English-speaking teachers are able to switch between languages.

In a multiple choice closed-ended question, teachers were asked why they would switch languages. The main reason for teachers to switch to either Dutch or English was for children to be able to understand them: 25 out of 27 teachers reported that they switched languages for this reason. Additionally, 17 out of 27 teachers switched languages to comfort children and 15 out of 27 to correct children. Interestingly, the teachers who reported not to switch between languages were able to speak the other language. Only five out of 20 teachers who reported not to switch categorized themselves as being absolute beginners or beginners in the other language.

It should be noted that 42 of the 47 teachers who filled in this part of the questionnaire worked at organizations where – according to the policy documents – the OPOL-principle was adopted, meaning that they were supposed to stick to one language (either Dutch or English) when communicating with a child. Clearly, there are differences between de jure and de facto language management and policy documents do not reflect the true state of affairs. Results from the questionnaire indicate that 25 out of these 42 OPOL-teachers did switch languages for the aforementioned reasons. This illustrates that some teachers are stricter than others at sticking to the OPOL-principle.

Aims and intended audience

The official announcement was analyzed to gain further insight into the societal and educational aims of this initiative are and whether or not this initiative was introduced in the interest of a specific social group (Kroskrity, Citation2004). It gives a number of reasons for introducing bilingual preschool education. First, it is stated that ‘young children have the unique power to learn multiple languages through play’ (Staatsblad Citation249, Citation2017, p. 6) and that ‘bilingualism can be an advantage for children, because from a very young age, they are aware of language comprehension and learn to deal with differences in interpretation’ (Staatsblad Citation249, Citation2017, p. 6). Furthermore, the announcement states that (1) a growing number of Dutch parents want their children to learn English at an early age, (2) parents find it important that their child becomes fluent in English because they believe it will benefit their future and better prepare them for the English classes at secondary school, and (3) it will enhance future opportunities on an internationally oriented job market (Staatsblad Citation249, Citation2017, p. 6). Thus, the official request seems to be targeted towards Dutch-speaking children: the aim is that they acquire an additional second language at a young age while it is still relatively easy to do so.

Also the participating daycare organizations’ policy plans were analyzed to gain further insight into the daycares’ aims. Similar to the statements made by the Dutch government in the official announcement of the pilot study, all daycare centers highlighted children's capacities to easily acquire two languages simultaneously in their pedagogical policy plans. In addition, they also mentioned the advantages that bilingualism might have, such as benefits for future careers and educational paths as well as cognitive benefits.

However, the participating daycare centers seemed to differ in the audiences they targeted. Roughly, two different audiences were targeted by different organizations: children who acquire English as a second language and/or children who acquire Dutch as a second language. Whereas five daycare centers only explicitly mentioned the advantages of acquiring English in addition to Dutch in their policy plans (similar to the official announcement of the Dutch government), five daycare centers also discussed the advantages of exposure to the Dutch language for children who do not hear Dutch at home, but any other language. One daycare explicitly mentioned that their audience consists for a large part of children from highly skilled migrant workers who acquire English as their first or second language, who sometimes stay in the Netherlands only temporarily and who usually attend 100% English daycares. Another daycare center mentioned that parents who speak English would want their children to get acquainted with Dutch because it might lead to an easier integration into the Dutch community. Thus, whereas the educational aim as stated by the government in the official request seemed to be targeting monolingual Dutch speakers, some daycare centers instead seemed to be targeting non-Dutch speaking children of highly skilled migrant workers, who acquire Dutch as their second (or third or fourth) language.

Audience

Characteristics and motivations

While the government appeared to envisage a Dutch-speaking target audience, in reality, results from our parental questionnaire indicate that the audience mainly consisted of multilingual families. shows which languages were spoken at home per organization.

Table 2. Overview of children's language background.

The results from the parental questionnaire paint a highly international, multilingual picture: the majority of children (72%) visiting a bilingual daycare center grew up in a multilingual household. Only 28% of the audience consisted of children growing up in a monolingual Dutch household. Approximately 37% of the children grew up in a household where no Dutch is spoken at all (3% English only, 18% English and any other language, 16% other languages). This means that many children acquired Dutch as a second language in the bilingual daycare centers. This is in line with the pedagogical policy plans from some organizations that specifically seemed to target non-Dutch-speaking children. In addition, approximately a quarter of the children (25%) grew up with both Dutch and English (and any other language) at home.

It should be noted that there was an interplay between the demographic characteristics of the audience and implementation of the English language into daily routines: the more multilingual the audience, the more English the language input offered at daycare centers. The majority of organizations, visited by a more multilingual audience opted for strong forms of bilingual education by implementing the OPOL-principle. Organizations opting for weaker forms of bilingual education seemed to have a more monolingual Dutch audience (in organizations H, I and J's audiences consisted of monolingual Dutch children for 64%, 67% and 80% respectively, whereas organizations A, B and C were not visited by any monolingual Dutch children).

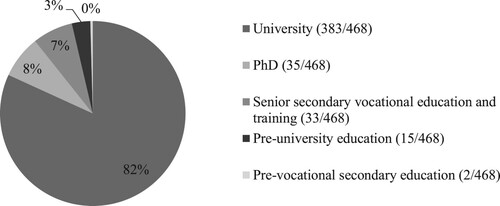

In addition, results from the questionnaire do not only show that the majority of the children grew up in a multilingual household, but that the parents were also highly educated. illustrates that a large majority of parents completed university (82%). Also, 8% of parents completed their PhD. The results from the parental questionnaire thus suggest that the bilingual daycare centers had a highly educated, international audience.

In an open question, parents were asked about their reasons for choosing bilingual daycare (see for an overview). Approximately one-third of the parents (30%) indicated that they did not necessarily choose this daycare center for its bilingual nature but for practical reasons such as proximity to the home: these were mostly Dutch-speaking parents. Parents who did choose bilingual daycare for a specific reason, gave a wide variety of reasons for doing so. The main reason parents gave was that they wanted to preserve their English heritage (19%). Another 10% of the parents indicated to find it important that their child learned a second language at a young age, and that they therefore opted for bilingual education. Some parents claimed to have chosen a Dutch-English daycare center to better integrate in the Netherlands (5%); these were all parents who indicated not to speak any Dutch at home and who would otherwise have opted for 100% English daycares meant for children of highly skilled migrant workers. This corresponds with policy plans from daycares who also targeted children acquiring Dutch as a second language.

Table 3. Parents’ reasons for choosing bilingual daycare (n = 236).

Language attitudes and status

In addition to questions about their main motivations for choosing bilingual Dutch-English daycare, parents were also asked about their attitudes towards the two languages. First, parents were asked if they wanted their child to learn English and Dutch. Most parents wanted their child to learn both English and Dutch: 88% of the parents indicated that they wanted their child to learn English, 95% of the parents indicated that they wanted their child to learn Dutch. Parents were also asked why they wanted their child to learn Dutch and English in two open questions (see for reasons parents gave for wanting their child to learn English).

Table 4. Parents’ reasons for wanting their children to learn English (n = 208).

The main reason parents give is because English is the language of the family (24%). Once again, the multilingual character of the audience is reflected in this answer. Others believe knowledge of English can be beneficial to their children's future career and education opportunities (20%). Additionally, some parents want their child to learn English because English is considered a world language (19%). Other parents think knowledge of the English language might facilitate communication with others (14%) and some parents want their child to learn English because they are considering moving abroad in the future (13%).

When parents were asked for reasons why they wanted their child to learn Dutch, again, the multilingual language backgrounds and international characteristics of the audience are reflected in the answers (see ). Whereas for English the most frequently mentioned reason was that English was the language of the family, for Dutch, most parents (46%) wanted their child to learn the language because it is the language of the country of residence (this answer was only given by parents who did not speak Dutch at home). One-third (33%) of the parents wanted their child to learn Dutch at daycare because it is the language of the family. It should be noted that all Dutch-speaking parents indicated that they wanted their child to acquire Dutch at bilingual daycare.

Table 5. Parents’ reasons for wanting their children to learn Dutch (n = 236).

Discussion and conclusion

This study sought to uncover the ideology behind the initiative to introduce bilingual Dutch-English education into the Dutch preschool system. To do so, the study focused on language policies of the daycare centers and attitudes towards the two languages. The initiative was discussed in relation to the key dimensions along which different forms of bilingual education can vary: (1) organization of bilingual input (de jure and de facto), (2) audience, (3) societal and educational aims, and (4) status of Dutch and English.

By using qualitative data (the analysis of policy documents) as well as quantitative methods (teacher and parental questionnaires) two competing underlying ideologies were found. When it comes to the societal and educational aims, a discrepancy between the aims of the Dutch government and the aims of some of the organizations and the majority of parents was found. These aims corresponded with two different ideologies. The Dutch government's intentions appear to be most in line with a prestigious strong ideology: the official request seems to be targeted towards Dutch-speaking children and the aim is that they acquire an additional second language of power (English) because it is believed that it will benefit their future. The policy plans of daycare centers mostly visited by Dutch-speaking children also resonated with these prestigious strong motivations. On the other hand, policy documents – especially those from daycare organizations visited by an international audience – were focused on exposing non-Dutch speaking children to Dutch. Data from parental questionnaires on the motivations of parents to enroll their children in bilingual daycare reflected the same two ideologies.

Not only the targeted audiences, but also the way the bilingual input was implemented varied from daycare to daycare. Analysis on de jure language management showed that six out of ten daycares chose for so-called strong forms of prestigious bilingual education by means of an OPOL-principle, whereas others opted for weaker forms of prestigious bilingual education by adopting early English language methods and fewer hours of exposure on fixed times of the day. However, results on de facto language management from the teacher questionnaire showed that the policy documents from organizations do not necessarily reflect the true state of affairs: the majority of the OPOL-teachers indicated to switch between languages. While this finding is suggestive of translanguaging approaches to bilingual education, it remains to be seen whether this behavior is fully rooted in the translanguaging ideology where all languages are welcome, irrespective of time, person or status. Previous studies show that teachers sometimes switch languages if they feel that the child's wellbeing is at risk (Caporal-Ebersold & Young, Citation2016). Also, it should be noted that information on de facto management was only gathered through two questions on language switching: this information is based on what teachers themselves report to be doing. No classroom observations were included in this study to further analyze language use in- and outside the classroom.

This study further revealed an interplay between audience and organization of bilingual input. Monolingual Dutch children mostly visited weaker forms of bilingual education whereas the multilingual audience mostly visited organizations where strong forms of bilingual education were implemented. This could possibly be attributed to the fact that some of the OPOL-organizations already offered bilingual input before the start of the pilot study, because their audience consisted of highly skilled migrant workers. The organizations opting for weaker forms of bilingual input started doing so at the start of this study. These organizations were mostly visited by Dutch-speaking children.

The different ideologies, reflected in different aims (targeting Dutch-speaking versus non-Dutch speaking children), as well as different ways of organization of bilingual input (weak versus strong), and different target audiences visiting the daycare centers (monolingual versus multilingual), make it difficult to qualify the entire initiative as being one of the four different forms of bilingual education, as laid out in . In general, the initiative as formulated by the Dutch government could be qualified as being prestigious in the sense that it targets a language majority audience and it involves two languages that have a high degree of cultural prestige (García & Wei, Citation2014; Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). However, some organizations instead seem to target a multilingual audience – one that in many cases already speaks English – and want to expose them to the national language instead. The prominent position of English in Dutch society (Edwards, Citation2016; Nortier, Citation2011) illustrates that the English language might – in some ways – have a higher cultural and educational prestige than the Dutch language: in the Netherlands, English is often used as a symbol of prestige, an identity marker and an expression of status (Edwards, Citation2016). Thus, organizations targeting an English-speaking audience and exposing them to a somewhat less prestigious state language make this a unique form of bilingual education that is not captured in the traditional categorization of bilingual education, as described in Ideologies in bilingual education.

In addition, the results show that the bilingual daycare centers also attract a highly educated elite: data from the parental questionnaires show that 90% of the parents completed university. This results echoes concerns about bilingual education being elitist (Sieben & Van Ginderen, Citation2014; Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). Even though bilingual daycare is still in a pilot phase in the Netherlands, it is telling that daycare organizations have registered for this pilot study that primarily cater to a highly educated audience. This finding raises questions: did these organizations decide to implement a bilingual curriculum because of their highly educated audience? Or did the organizations attract this highly educated audience after implementing Dutch-English bilingual input? Whereas some organizations explicitly stated to have implemented bilingual input because of their (highly educated) international audience, for the other organizations this remains unclear. One way or the other, these findings resonate with the idea that prestigious bilingual education often involves educational elites (Sierens & Van Avermaet, Citation2014). However, it should be noted that the data were gathered in the context of a pilot study: in our data, a substantial part of the audience consists of highly educated, multilingual families. If the Dutch government decides to introduce bilingual preschool education on a larger scale, and allow other languages, the composition of the audience might very well change. After all, the number of highly skilled migrant workers is limited (383.000 workers out of 17 million inhabitants in 2018, p. 9; Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Citation2020), and more Dutch-speaking families will ultimately have the opportunity to visit bilingual preschools.

What do these results ultimately say about the status of the Dutch and English language in Dutch bilingual preschool education? On the one hand, the introduction of bilingual preschool education in the Netherlands is part of an ongoing ‘Englishization’ (Earls, Citation2013) of the Dutch educational system (described in The role of English in Dutch education): it is related to a societal as well as educational change that has been taking place for decades. In that sense, Dutch-English bilingual preschool education can be viewed as a product of the importance of English in Dutch society. This is also illustrated by the fact that, even though they were allowed to, none of the participating daycare centers choose to offer French or German in addition to Dutch.

On the other hand, our results from the parental questionnaires suggest that Dutch is important for many parents: 95% of parents indicated that they want their child to learn Dutch and 30% of the parents did not necessarily choose this daycare center for its bilingual nature. This may indicate that the English language does not necessarily pose a threat to the status of Dutch in bilingual daycares. In addition, the Dutch-English bilingual daycare centers open up more opportunities for multilingual (international) audiences to acquire the Dutch language. Sending their children to bilingual daycare centers where Dutch as well as English (often one of their home languages) is spoken, is an accessible way for their children to get acquainted with the Dutch language. Still, the introduction of Dutch-English curricula into Dutch preschool education could be viewed as another example of the increasing role of the English language in Dutch education, which leads some people to believe that the status and use of Dutch needs to be defended (for an overview, see Nortier, Citation2011). Future research should determine what larger scale introduction, that would create a fully bilingual English-Dutch educational track running from zero to eighteen, would mean for the status of the Dutch language in the Dutch preschool system in the long run.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [D.K.], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Darlene Keydeniers

Darlene Keydeniers is a PhD candidate within Project MIND (Multilingualism in Daycare) at the University of Amsterdam. This project investigates the effects of Dutch-English bilingual input at daycares on the acquisition of the two languages. For this project, Darlene studies the acquisition and development of the Dutch language.

Suzanne Aalberse

Suzanne Aalberse works as an Assistant Professor at the department of Dutch linguistics at the University of Amsterdam and is involved in Project MIND. Her main interests are language variation and change, language contact, (bilingual) language acquisition and the relationship between acquisition processes and (non)-change.

Sible Andringa

Sible Andringa works as an Assistant Professor at the department of Dutch linguistics at the University of Amsterdam. Apart from being a collaborator in Project MIND, Sible ran several studies investigating the role of input instruction and awareness in second language learning. He aims to do theoretically driven research that may have practical, pedagogical implications.

Folkert Kuiken

Folkert Kuiken is a Professor of Dutch as a Second Language and Multilingualism at the department of Dutch linguistics at the University of Amsterdam (special Chair of the city of Amsterdam). Folkert is the project leader of Project MIND.

Notes

1 At the start of the pilot study, one daycare center signed up to offer French. Due to staffing problems, the daycare center had to drop out of the experiment.

2 Vmbo, havo and vwo are three different streams of secondary education in the Netherlands. Vmbo stands for pre-vocational secondary education, havo for senior general secondary education and vwo for pre-university education.

3 Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee Faculty of Humanities at the University of Amsterdam (2017–61). All participants gave permission through written informed consent.

References

- Admiraal, W., Westhoff, G., & De Bot, K. (2006). Evaluation of bilingual secondary education in the Netherlands: Students’ language proficiency in English. Educational Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610500392160

- Ammon, U., & McConnell, G. (2002). English as an academic language in Europe. A survey of its use in teaching. Peter Lang.

- Appel, R. (2003, June). Meer Engels betekent minder Nederlands. NRC Handelsblad.

- Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Multilingual Matters.

- Bernstein, K. A., Kilinc, S., Deeg, M. T., Marley, S. C., Farrand, K. M., & Kelley, M. F. (2018). Language ideologies of Arizona preschool teachers implementing dual language teaching for the first time: Pro-multilingual beliefs, practical concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1476456

- Blink, E. (n.d.). Engels leren door muziek. https://groove.me/over-grooveme/

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

- Caporal-Ebersold, E., & Young, A. (2016). Negotiating and appropriating the “one person, one language” policy within the complex reality of a multilingual crèche in Strasbourg. London Review of Education, 14(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.14.2.09

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2020, februari). Internationale kenniswerkers. Nederland in vergelijking met 13 andere Europese landen. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2020/07/internationale-kenniswerkers-in-nederland-en-europa

- Cummins, J. (2008). Teaching for transfer: Challenging the two solitudes assumption in bilingual education. In N. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 1528–1538). Springer.

- De Korte, S. (July, 2006). Engelse les aan kleuters populair. Nemo Kennislink. https://www.nemokennislink.nl/publicaties/engelse-les-aan-kleuters-populair/0

- Dyers, C., & Abongdia, J. F. (2010). An exploration of the relationship between language attitudes and ideologies in a study of francophone students of English in Cameroon. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630903470837

- Earls, C. W. (2013). Setting the catherine wheel in motion: An exploration of “englishization” in the German higher education system. Language Problems and Language Planning, 37(2), 125–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.37.2.02ear

- Early Bird. (n.d.). Peuters leren Engels met Benny’s playground. https://www.earlybirdie.nl/engels-voor-peuters.html

- Edwards, A. (2016). English in the Netherlands: Functions, forms and attitudes. John Benjamins.

- European Commission. (2012). Europeans and their languages. Special Eurobarometer 386. http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jenniskens, T., Leest, B., Wolbers, M., Krikhaar, E., Teunissen, C., De Graaff, R., Unsworth, S., & Coppens, K. (2018). Evaluatie pilot Tweetalig Primair Onderwijs: Vervolgmeting schooljaar 2016/17.

- Koninklijke Nederlandse Academie van Wetenschappen. (2018). Talen voor Nederland. In M. Huisjes (Ed.), Koninklijke Nederlandse akademie van Wetenschappen (pp. 1–79). KNAW. https://www.knaw.nl/shared/resources/actueel/publicaties/pdf/20180205-verkenning-talen-voor-nederland.

- Kroskrity, P. (2004). Language ideology. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 496–517). Blackwell.

- Kroskrity, P. (2018). Language ideologies and language attitudes. Oxford Bibliographies. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199772810/obo-9780199772810-0122.xml

- Nortier, J. (2011). “The more languages, the more English?” In A. Wilton, A. De Houwer, & J. Benjamins (Eds.), English in Europe today: Sociocultural and educational perspectives (pp. 113–132). John Benjamins.

- Nuffic. (2017). Meer studenten, en misschien ook betere. Transfer: Onafhankelijk Vakblad Over Internationalisering in het Hoger Onderwijs, 24(3), 13–19.

- Nuffic. (2018). Internationalisering in beeld 2018: feiten en cijfers uit het onderwijs.

- Nuffic. (2021). Alle tto scholen in Nederland. https://www.nuffic.nl/onderwerpen/tweetalig-onderwijs/alle-tto-scholen-nederland

- Parantion. (2017). Easion Survey. https://www.easion.nl

- Ronjat, J. A. (1913). Le développement du langage observé chez un enfant bilingue. Champion.

- Sieben, I., & Van Ginderen, N. (2014). De keuze voor tweetalig onderwijs. Mens en Maatschappij, 89(3), 233–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5117/MEM2014.3.SIEB

- Sierens, S., & Van Avermaet, P. (2014). Language diversity in education: Evolving from multilingual education to functional multilingual learning. In D. Little, C. Leung, & P. Van Avermaet (Eds.), Managing diversity in education: Languages, policies, pedagogies (pp. 204–222). Multilingual Matters.

- Silverstein, M. (1979). Language structure and linguistic ideology. In P. Clyne, W. F. Hanks, & C. L. Hofbauer (Eds.), The elements: A parasession on linguistic units and levels (pp. 193–247). Chicago Linguistic Society.

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Staatsblad 249. (2017). Besluit van 6 juni 2017, houdende tijdelijke regels voor een experiment in het kader van meertaligheid in de dagopvang en het peuterspeelzaalwerk (Tijdelijk besluit experiment meertalige dagopvang en meertalig peuterspeelzaalwerk). https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2017-249.html

- Wächter, B., & Maiworm, F. (2008). English-taught programs in European higher education. ACA Papers on International Cooperation in Education. Lemmens.