ABSTRACT

Many universities in non-English speaking countries have been adopting English as a medium of instruction to internationalize their education. We set out to compare the language policies of a Finnish and a Japanese university using the lens of language ideology – a set of normative beliefs about the social dimension of language. Data were collected from selected documents of the two universities, and analyzed utilizing critical discursive psychology. This social constructionist approach allows mapping out language ideological landscapes – interrelationships among different co-occurring language ideologies – from which students may draw ideas about how they orient themselves towards their peers on international campuses today. Our analysis shows that different language ideological landscapes are constructed in the language policies of the two universities, affording them different positioning in the phenomenon of internationalization. The findings suggest that both multilingualism and languaging would be important discursive resources for universities to maintain ethnolinguistic nationalism and ensure equality among students with different linguistic backgrounds, in the process of internationalization of higher education through English. On international campuses where multilingualism is prevalent, students are likely to be constructed as cosmopolitans for inclusion, locals and foreigners for exclusion, or ‘native/native-like and non-native speakers’ for hierarchy through different monolingual language ideologies.

Introduction

Over the last decades, adopting English-medium instruction (EMI) has been a common strategy for non-English speaking countries to internationalize their higher education (Macaro et al., Citation2018). In this transformation, we are especially interested in how language ideologies – sets of normative beliefs about the social dimension of language – in university language policies might inform the ways that students make sense of their interactions with their peers, acknowledging that such ideologies likely create a certain system of social categories and power relations by mediating between ideas about language and people (Woolard & Schieffelin, Citation1994). We approach language ideologies as both constituted by and constitutive of their context (Kraft & Lønsmann, Citation2018), and see university language policies as evidence of language ideologies that are widespread on university campuses and that are relevant for the ways that members of the university community construct and are constructed by the social world.

Language policies have been approached as consisting of declared language policies (de jure policies) and linguistic practices (de facto policies; Johnson, Citation2013; Lo Bianco, Citation2008; Shohamy, Citation2006; Spolsky, Citation2004). Previous studies on university language policies have drawn on this framework to identify discrepancies between language ideologies in university language policies and linguistic practices of students and staff members. Some studies (e.g. Jenkins, Citation2014; Kuteeva, Citation2014) challenge ‘native-speaker’ norms of English prevalent in university language policies as creating inequalities among students. Instead, they argue for the notion of English as a lingua franca to respect students’ multilingual practices. Other studies (e.g. Airey et al., Citation2017; Björkman, Citation2014; Jenkins & Leung, Citation2019) suggest that, rather than prioritize national categories of language, universities should take academic and discipline-specific linguistic practices into account.

However, as meso-level actors in language planning (Liddicoat, Citation2016; Lo Bianco, Citation2005), universities apparently also need to balance the vitality of English and the national language(s) in terms of higher-level language planning (see Robertson & Kedzierski, Citation2016). It is therefore important to examine how different co-occurring language ideologies interconnect with one another in university language policies (both de jure and de facto policies), forming what Kraft and Lønsmann (Citation2018) have termed a language ideological landscape. Kraft and Lønsmann highlight the futility of examining the ideologies connected to one specific language in isolation since ‘ideologies of one language are linked to its relationship to other languages and to ideologies of these other languages’ (Citation2018, p. 47). Furthermore, Phan (Citation2016) points to the importance of ‘mov[ing] beyond making polarized assumptions about English language users’ identity positionings based largely on moral and ethical judgements of one another’s ideologies’ (p. 354).

In this paper, we analyze language ideological landscapes in the language policies of the University of Jyväskylä (JYU) in Finland and Akita International University (AIU) in Japan, with a focus on social meanings afforded to students. In recent years, Nordic countries have been seen as putting an emphasis on the need to protect their national languages from the spread of English in the academic domain (e.g. Bolton & Kuteeva, Citation2012; Saarinen & Taalas, Citation2017). Meanwhile, Japan has been seen as emphasizing its own uniqueness against others associated with English by promoting English while undermining Japanese in international contexts (Phan, Citation2013; see also Hashimoto, Citation2000, Citation2013). We find that comparing these two potentially different contexts can offer interesting insights into the process of internationalization of higher education through EMI. Our data were collected from selected documents of JYU and AIU to identify both de jure and de facto language policies that are relevant to students – their academic success and interactions on campus. In the analysis, we utilize critical discursive psychology to illuminate inconsistencies or contradictions among different co-occurring ideologies. Our questions are: (1) What language ideological landscapes are constructed in the language policies of JYU and AIU that concern students? (2) What social categories and power relations do these ideological landscapes afford to students?

Theoretical framework

Language ideologies

We define language ideologies from a critical perspective as ‘the cultural (or subcultural) system of ideas about social and linguistic relationships, together with their loading of moral and political interests’ (Irvine, Citation1989, p. 255). Language ideologies connect language and the social world, endowing groups of speakers with specific characteristics, status, rights, and obligations (see also Woolard, Citation1998). Language ideologies inform our understandings of linguistic practices, simultaneously erasing phenomena that do not align with the specific point of view (Gal, Citation2006). However, speakers have more than one dominant ideology at their disposal, as the notion of language ideological landscapes and the analytical concepts of critical discursive psychology put forward. Interactions between and among speakers of different languages or language varieties may be regarded as potentially rich in language-related categorization. Different language ideologies publicly available and maintained in popular, institutional, political, or scientific discourses may serve as the material for people to construct in- and out-groups and rationalize such categorization and constructed power relations (Woolard & Schieffelin, Citation1994).

We see language ideologies as situated and both constituted by and constitutive of their context (Kraft & Lønsmann, Citation2018). As meso-level actors in language planning (Liddicoat, Citation2016; Lo Bianco, Citation2005), universities can be seen as not only reproducing higher level national and institutional ideologies about language but also as constructing other ideologies and possibly challenging existing dominant ideologies – especially since universities are at the center of scientific debates about language and multilingualism. In this sense, university language policies are likely to be products of negotiations among different stakeholders including those involved in national-level planning, internationalization efforts as well as those with an understanding of language and multilingualism research. With this in mind, university language policies can be approached as representing language ideologies pervasive on university campuses, which inform the ways that members of the university community create and are created by the social world.

We are specifically interested in language ideological landscapes constructed in university language policies. We see that these (potentially diverse and perhaps even dilemmatic) constellations of ideas about the status, epistemic authority, or desirability of speakers of different languages and language varieties on international campuses may serve as the ‘prevailing discursive environment’ (Seymour-Smith et al., Citation2002, p. 254) from which students can draw to explain and rationalize the ways in which they orient themselves to their peers. Here, we also acknowledge that the applications of any language ideology are ‘interest-laden and positioned’ (Gal, Citation2005, p. 25) and thus construct and normalize a certain system of social categories and power relations among them.

Language ideologies and paradigms in multilingualism research

Language ideologies are produced and reproduced across different social spheres such as in media, policy, or mundane everyday interactions. To understand them in more depth, it is important to reflect them against discussions about language and language diversity in the realm of scientific discourse. In fact, intellectual ideology (represented in formal theories) and lived ideology (represented in commonsensical ideas) should be seen as intricately interrelated and mutually informing each other (Billig et al., Citation1988).

Ideas about the nature of language and language use in the context of language diversity and multilingualism research have been changing so drastically that one could describe them as a paradigmatic shift. The conventional conception of language has seen language as an idealized, immutable, and decontextualized entity that pre-exists and determines language use (Lüdi, Citation2013). This view treats language as a nameable closed and internally homogeneous system bound to a national group that is a conduit for some underlying ‘national culture’ and that is mutually exclusive – though inter-translatable – with other such systems (see Gal, Citation2006; Piller, Citation2012). By highlighting the distinctness and internal homogeneity of a social group, this standard language ideology legitimates political arrangements such as claims to a territory, state, and political autonomy (Gal, Citation2006).

The notion of homogeneous speech communities of monolingual, monocultural nationals that such traditional conceptualization of language conveys has been increasingly challenged (Kramsch & Whiteside, Citation2007). Alternatively, language has been approached as languaging – an emergent, contextual, and interactional activity (Lüdi, Citation2013) that is not backed up by a self-contained linguistic system. This approach treats persons in interaction as dynamically and creatively drawing on any linguistic resources they may have to address local interactional problems and construct shared understanding.

Critics of traditional approaches to language (e.g. Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012) have discussed the problematic nature of the concept of multilingualism, pointing out that it reproduces the notion of language as a distinctive and objective entity. New constructs that highlight the creative, emergent, context-bound, and pragmatic character of linguistic practices have been offered. Translanguaging (e.g. Canagarajah, Citation2011; García & Li, Citation2014) highlights how speakers draw on and transcend their linguistic repertoires that defy the traditionally construed boundaries among supposedly autonomous language systems to generate new meanings and identity positions, exhibiting both creativity and criticality. Multilanguaging (e.g. Lüdi, Citation2013) describes how interactants negotiate shared understanding through simultaneously mobilizing their multilingual repertoires or resources (both verbal and embodied). In defining metrolingualism, Makoni and Pennycook refer to practices where interactants ‘use, play with and negotiate various identities through language; it does not assume connections between language, culture, ethnicity, nationality, or geography but rather seeks to explore how such connections are produced, resisted, defied or rearranged’ (Citation2012, p. 449).

These developments are also reflected in discussions on the global position of English. There has been severe criticism of the concept of the native speaker (e.g. Holliday, Citation2006, Citation2015; Kabel, Citation2009; Piller, Citation2001) that highlights the notion’s socially constructed character and its ideological power in normalizing ethnolinguistic nationalism, promoting a monolingual mindset and justifying not only symbolic but also material inequalities among different speakers of English. Jenkins (e.g. Citation2011) has argued for abandoning the English as Second Language/English as Foreign Language paradigm that constructs L2 speakers of English as deficient and never able to meet the ‘native speaker’ proficiency standard. Instead, she points to English as a Lingua Franca as a new empowering discourse where English is recognized as a global language that belongs to anyone who uses it in different domains of social life. In a similar vein, Kuteeva (Citation2014) speaks of academic English as one variety of global English that is nobody’s first language – thus challenging the native speakerism ideology and its persistence in higher education contexts (see also Piller, Citation2016).

Methodology

Critical discursive psychology

Critical discursive psychology (CDP) reframes traditional psychological concepts, such as social categories, as socially constructed emergent and fluid resources that may be made relevant in text and talk to create order in the social world (Reynolds & Wetherell, Citation2003; Wiggins, Citation2017). One of the core ideas of CDP is that talk and text about any topic can be highly irregular and incongruent, leading to different, dilemmatic versions of social reality (e.g. Wetherell, Citation1996). CDP works with the analytical concepts of interpretative repertoires, subject positions, and ideological dilemmas. An interpretative repertoire is an easily recognizable common-sense description or explanation about a topic made up of familiar themes, tropes, and places (Wetherell, Citation1998). Interpretative repertoires are building blocks for developing different versions of the social reality (Wetherell & Potter, Citation1992). They can be seen as bridges that connect situated discourse to the broader social context and socially available collective resources for discussing different topics (Wetherell, Citation1996). The interpretative repertoires deployed in text and talk afford specific subject positions – roles, rights, and obligations – to entities and persons (Reynolds & Wetherell, Citation2003). Within a single text there may be different interpretative repertoires employed; the inconsistencies among these repertoires may result in ideological dilemmas as divergent and perhaps even competing accounts are offered to the readers to ponder, negotiate, and make sense of (e.g. Reynolds & Wetherell, Citation2003). We find these analytical concepts useful to examine interrelationships, especially inconsistencies or contradictions, among different co-occurring language ideologies that together form a specific language ideological landscape.

Data set

We analyze the language policies of JYU in Finland and AIU in Japan that are relevant to students. These universities were selected because both are in unique positions in their national contexts. JYU is a multidisciplinary public university that comprises 6 faculties and provides 17 English-medium master’s programs (one of them is a joint program with other European universities) in different disciplines as well as various bachelor’s and master’s programs primarily in Finnish. It is also common that some courses are entirely or partially delivered in English in the programs other than the English-medium ones. What is unique about JYU is that it is highly interested and active in applied linguistics research and its application to linguistic practices on campus. In contrast, AIU is a small public liberal arts college that offers 3 undergraduate and 2 graduate programs in English and 1 graduate program in Japanese (about Japanese language teaching). It is the only Japanese public college/university that specifically focuses on EMI. Some compulsory courses in the Japanese-medium program are also taught in English. A small admission quota is officially placed for foreign students in the undergraduate programs, but not in the graduate programs. We expect that similarities between these very different universities can be interpreted as something common across different contexts of EMI for internationalization of higher education.

The initial data were collected from several policy documents of JYU and AIU (see ) in order to identify de jure language policies in policy-level texts. Students may not read these documents on their own, but the documents would be relevant to them as ultimate references of their linguistic practices on campus. Moreover, it is likely that other persons on campus that students interact with (lecturers, administrative staff) are very much aware of these documents and draw on them in interactions with students. As the data analysis progressed, further data were collected from some procedure documents (see ) in order to identify de facto language policies in practice-level texts. These documents are highly relevant to students because they are expected to read the documents in the application process for admission to their programs and over the course of their studies. The overall word count of the 39 JYU documents was 86,393, and that of the 16 AIU documents was 73,814. We limited our data sources to documents publicly available on the JYU and AIU webpages in the form of PDF files or webpage text to make sure that we analyzed documents that were indeed publicly available to relevant stakeholders. We call all the different data sources documents for the sake of practicality.

Table 1. Initial data sources.

Table 2. Additional data sources.

Data analysis

We regard language ideologies as interpretative repertoires because the two concepts are remarkably similar. In fact, language ideologies can be explained using the analytical concepts of CDP. Language ideologies are widely used in text and talk to describe or explain language or language use in relation to people as language speakers, providing entities and persons with language-related social categories (see Woolard, Citation1998), thus placing them in specific positions in relation to one another. When some language ideologies are deployed side by side, ideological dilemmas may be created between and among them (e.g. ‘native-speaker’ norms of English and the notion of English as a lingua franca, see Jenkins, Citation2014). Hence, one can say that language ideologies are interpretative repertoires about language and its speakers.

The first author was in charge of the analysis, but she discussed her choices with the second author throughout the process to ensure the robustness of analysis. First, she went over the material to identify different ways of discussing language-related matters (such as the nature of language and multilingualism on campus, preferred languages and language choices in different situations and interactions, expected language proficiency of students, etc.). She then inductively searched for patterns across these representations to identify language ideologies, with reference to some common language ideologies reviewed in the previous section. By corollary, she attended to the different subject positions these ideologies afford to students, that is, different language-related social categories for students and power relations among them produced in the documents. Next, she explored ideological dilemmas in each university’s language policies to map out the language ideological landscape. Finally, she addressed possible connections between institutional discourses of JYU and AIU in our findings and the national discourses of Nordic countries and Japan in prior literature (e.g. Phan, Citation2013; Saarinen & Taalas, Citation2017).

The documents analyzed in this study are in three languages: Finnish, Japanese, or English (see and ). Although the first author was responsible for the analysis, the authors used their combined linguistic resources to help the first author make sense of all the documents in detail. The first author is fluent in Japanese and English, while the second author is proficient in Finnish and English. The first author carried out the analysis of all the AIU documents, checking the consistency between the Japanese and English versions of the documents. Yet, she discussed her findings with the second author throughout the process. The second author assisted in the analysis of the JYU documents by discussing JYU Language Policy (only available in Finnish) thoroughly with the first author, and also comparing the Finnish and English versions of other JYU documents. In case of slight differences between the two versions of the document, the original language version was given priority in the analysis.

Findings

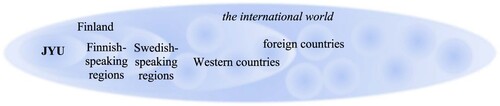

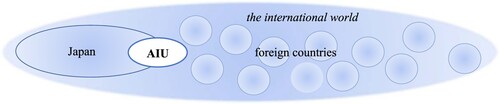

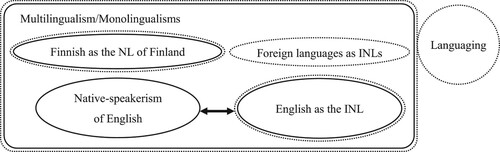

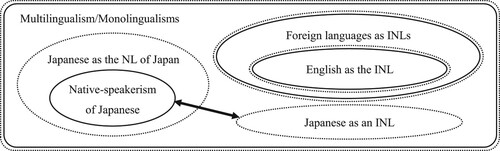

Our analysis of policy- and practice-level texts of the different documents of JYU and AIU identifies different de jure and de facto language policies as manifestations of language ideologies. As shown in and , different sets of co-occurring ideologies construct different ideological landscapes in the language policies of JYU and AIU that concern students, affording the two universities different positioning in the phenomenon of internationalization (see and ). Despite the differences, multilingualism/monolingualisms is commonly formed of three types of monolingual language ideologies – national language ideologies, international language ideologies, and native-speakerism – which are all based on the notion about language as a closed system bound to a national group and existing before/outside interaction.

Figure 1. Language ideological landscape in JYU language policies.

Note: dotted figures–de jure policies, solid figures–de facto policies, double arrow–ideological dilemma, NL–national language, INL–international language.

Figure 2. Language ideological landscape in AIU language policies.

Note: dotted figures–de jure policies, solid figures–de facto policies, double arrow–ideological dilemma, NL–national language, INL–international language.

National language ideologies as both de jure and de facto policies encourage students to cherish languages as not only means of local communication but also conduits for underlying membership in national communities. International language ideologies allow students to utilize named languages as means of international communication. Lastly, native-speakerism as another de facto policy connects authenticity or legitimacy of language proficiency and status to students from specific countries. These three types of ideologies provide students with three prototypical sets of social categories: locals and foreigners, cosmopolitans, and ‘native and non-native speakers’ – the nature of which is mutually exclusive, inclusive, or hierarchical. Hence, multilingualism/monolingualisms as both de jure and de facto language policies constructs the student community as based on membership in different national communities.

In addition, only as a de jure language policy of JYU, languaging is constructed based on the notion about language as an emergent, contextual, and flexible practice in interaction. It draws attention to linguistic practices in everyday interactions on campus and in society. We will hereafter explain how different language ideologies are constructed and interrelated in the language policies of JYU and AIU, paying attention to accompanying constructions of social categories for students and power relations among them.

JYU’s de jure multilingualism/monolingualisms for mutual exclusion and inclusion with a hint of languaging

In the first paragraph of JYU Kielipolitiikka [JYU Language Policy], Finnish as the national language of Finland and foreign languages as international languages form multilingualism/monolingualisms, providing students with the mutually exclusive social categories of locals from Finland and foreigners and the inclusive category of foreign-language-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 1

Jyväskylän yliopisto on perinteiltään vahvasti suomenkielinen, mutta monikielinen ja kulttuurinen akateeminen yhteisö. Vuonna 2015 yliopistossa työskentelee ja opiskelee yli sadan eri kansalaisuuden edustajia. Yhteiskunnan moninaisuus näkyy selvästi myös yliopiston arjessa, jossa monikielisyys ja -kulttuurisuus ovat resursseja, joita arvostetaan ja hyödynnetään tavoitteellisesti läpi yliopistoyhteisön. (JYU Kielipolitiikka)

[The University of Jyväskylä has a strong Finnish-speaking tradition, but is a multilingual and multicultural academic community. In 2015, more than a hundred representatives of different nationalities will work and study at the university. The diversity of society is also clearly visible in the everyday life of the university, where multilingualism and multiculturalism are resources that are valued and utilized purposefully throughout the university community. (JYU Language Policy, authors’ own translation)]

Notably, the emphasis on Finnish over foreign languages echoes JYU’s positioning in the phenomenon of internationalization. In Extract 1, JYU is depicted as part of a larger international community (the world at largest) in the connection between ‘the diversity of society’ and ‘the everyday life of the university’. In other words, the university finds itself in internationalization of a wider society because the boundaries between the university, the Finnish society, and the larger world are presented as permeable.

Part of another paragraph of the same document in the section titled ‘yliopisto opiskeluympäristönä’ [‘the university as a study environment’] adds English as the international language to multilingualism/monolingualisms, offering students the inclusive social category of English-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 2

Tähän kuuluvat sekä suomen kielen ja kulttuurin vaaliminen että toisen kotimaisen kielen, englannin kielen ja vieraiden kielten viestintätaitojen monipuolistaminen sekä kulttuuritietoisuuden ja -osaamisen kehittäminen. (JYU Kielipolitiikka)

[This includes the preservation of the Finnish language and culture, as well as the diversification of communication skills in the second domestic language, English and foreign languages, and the development of cultural awareness and competence. (JYU Language Policy, authors’ own translation)]

Besides multilingualism/monolingualisms, languaging is constructed somewhat oddly in only one paragraph of JYU Language Policy, which is disconnected from the rest of the document for the different understanding of language operating there.

Extract 3

Kielipolitiikka edistää dynaamista monikielisyyttä, kykyä reagoida joustavasti ja nopeasti viestinnällisiin tilanteisiin, valmiutta käyttää osittaistakin kielitaitoa sekä avarakatseisuutta ja positiivista asennetta eri kieliä ja erilaista kielenkäyttöä kohtaan. (JYU Kielipolitiikka)

[Language policy promotes dynamic multilingualism, the ability to respond flexibly and quickly to communicative situations, the readiness to use even partial language skills, as well as open-mindedness and positive attitudes towards different languages and different language use. (JYU Language Policy, authors’ own translation)]

AIU’s de jure multilingualism/monolingualisms for inclusion and implicit mutual exclusion

In the first paragraph of AIU Institutional Policies and Regulations, foreign languages as international languages, English as the international language, and Japanese as the national language of Japan together form multilingualism/monolingualisms. This affords students the inclusive social categories of foreign-language- and English-speaking cosmopolitans and the mutually exclusive categories of locals from Japan and foreigners.

Extract 4

Akita International University … aims to educate students so that they may use their fluency and practical skills in foreign languages, especially in English … to contribute to the prosperity of both the international and local community. (AIU Institutional Policies and Regulations, also available in Japanese)

The emphasis on foreign languages along with the absence of Japanese is explained by AIU’s positioning in the phenomenon of internationalization. In Extract 4, AIU is depicted as a mediator between the local (Japan) and international (the world at largest) community in its mission: ‘to educate students … to contribute to the prosperity of both the international and local community’. The Japanese society is separated from the larger world, and the university is placed somewhere between the two while also being separated from both communities.

In this vein, AIU Graduate Program Policies adds Japanese as the international language to multilingualism/monolingualisms, offering students the inclusive social category of Japanese-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 5

The mission of the Akita International University Graduate School of Global Communication and Language (AIU GSGCL) is to prepare students for careers in professional communication fields that make positive contributions to today’s global society. With programs in English and in Japanese … , the GSGCL provides students with the knowledge and practical skills they need to advance their careers. (AIU Graduate Program Policies, also available in Japanese)

JYU’s de facto multilingualism/monolingualisms for mutual exclusion and inclusion or hierarchy

In the list of acceptable proof of Finnish language proficiency for the Finnish-medium programs of JYU, Finnish as the national language of Finland is constructed, affording the mutually exclusive social categories of locals from Finland and foreigners to students.

Extract 6

- Perusopetus, toisen asteen tutkinto tai muu korkeakoulukelpoisuuden antava tutkinto suoritettu suomen kielellä (mikäli päättötodistuksessa äidinkieli hyväksytyllä arvosanalla) … .

(JYU Hakeminen yhteishaussa)

[- Primary education, secondary level degree or another degree giving eligibility for higher education completed in Finnish (if mother tongue features in the final certificate with a passing grade) … .

(JYU Applying in the Joint Application, authors’ own translation)]

The application process of 4 English-medium programs includes the demonstration of English language proficiency. In the assessment criteria, English as the international language is constructed, offering students the inclusive social category of English-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 7

English language proficiency demonstrated during the application process

The Centre for Multilingual Academic Communication (Movi) of JYU will assess the academic readiness and language proficiency of the applicant based on a written pre-task and an interview. The evaluation criteria are based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), adapted for academic purposes.

(JYU Admission Criteria, Master’s Degree Programme in Educational Sciences)

However, exclusive/hierarchical constructions of students as English speakers are also to be found in different documents of JYU. In the list of acceptable proof of English language proficiency for 12 English-medium programs, native-speakerism of English is constructed, providing students with the hierarchical social categories of ‘native/native-like and non-native speakers’ of English.

Extract 8

- Upper secondary education completed in English in a Nordic country (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland), the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand.

- A higher education degree completed in English in an EU/EEA country, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand.

- An international language proficiency test in English … .

(JYU Admission Criteria, Master’s Degree Programme in Banking and International Finance)

The co-occurrence of those different language ideologies in the different practice-level texts establishes de facto multilingualism/monolingualisms in the language policies of JYU. As with the de jure multilingualism/monolingualisms, Finnish is clarified as the national language of Finland to solidify the mutually exclusive categories of students as locals from Finland and foreigners although Finnish language proficiency is not firmly connected to membership in the Finnish society. With respect to English, while it is treated as the international language in some English-medium programs, in many such programs native-speakerism of English is constructed to create an ideological dilemma when paired with the notion of English as the international language. Consequently, the hierarchical categories of students as ‘native/native-like and non-native speakers’ of English contradict the inclusive category of students as English-speaking cosmopolitans. All in all, JYU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms as a whole conveys JYU’s strong interest in the preservation of Finnish in its internationalizing student community through English. Seemingly, the category of students as foreign-language-speaking cosmopolitans is the only social category that can facilitate the inclusion of students without any conflict.

AIU’s de facto multilingualism/monolingualisms for inclusion and hierarchy

In the additional note of the language requirements for the undergraduate programs of AIU, English as the international language is constructed, affording students the inclusive social category of English-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 9

Even in countries/regions (e.g. U.S.A, Australia, etc.,) and educational institutions (e.g. International school, etc.,) where the education system in which the first language is English and entirely taught in English, applicants are required to submit an official document that proves the medium of instruction is English.

(AIU Undergraduate Admission Information and Application Form for International Students, also available in Japanese)

The notion of English as the international language is more consistent in the language requirements for all the graduate programs. In the same document, native-speakerism of Japanese is also constructed together with foreign languages as international languages, providing students with the hierarchical social categories of ‘native and non-native speakers’ of Japanese and the inclusive category of foreign-language-speaking cosmopolitans.

Extract 10

English Language Teaching Practices

TOEFL iBT®TEST 88, TOEFL®PBT TEST 570, or an equivalent level of English demonstrated by another English test … .

Japanese Language Teaching Practices

Native Speaker of Japanese (Must meet 1) or 2) of the requirements below)

TOEFL iBT®TEST 71, TOEFL®PBT TEST 530, or an equivalent level of English demonstrated by another English test … .

Must meet both of the following requirements- TOEFL iBT®TEST 61, TOEFL®PBT TEST 500, or an equivalent level of English

demonstrated by another English test … .

- Those who demonstrated proficiency by language test other than English … .

Non-Native Speaker of Japanese (Must meet both of the requirements below)

TOEFL iBT®TEST 61, TOEFL®PBT TEST 500, or an equivalent level of English demonstrated by another English test … .

JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) 1st-level, or N1 level.Global Communication Practices

TOEFL iBT®TEST 79, TOEFL®PBT TEST 550 or an equivalent level of English demonstrated by another English test … .

(AIU Graduate Program Admissions, also available in Japanese)

The co-occurring different language ideologies in the different practice-level texts together form de facto multilingualism/monolingualisms in the language policies of AIU. Foreign languages, especially English, are treated as international languages in line with the de jure multilingualism/monolingualisms, and thus the inclusive categories of students as foreign-language- and English-speaking cosmopolitans are reinforced. However, since native-speakerism of Japanese is constructed, an ideological dilemma is created when paired with the notion of Japanese as the international language. This dilemma places the inclusive category of students as Japanese-speaking cosmopolitans in contradiction with the hierarchical categories of students as ‘native and non-native speakers’ of Japanese. Nevertheless, the inclusion of students can be facilitated by the categories of foreign-language- and English-speaking cosmopolitans, as seen in the emphasis on foreign languages as international languages in the alternative language requirements for ‘native speakers’ of Japanese in the Japanese-medium program. AIU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms as a whole indicates AIU’s strong interest in foreign languages, especially English, as resources for internationalization alongside the assumed vitality of Japanese. In any case, the categories of students as locals from Japan and foreigners remain for implicit mutual exclusion.

Discussion

We have mapped out the language ideological landscapes in the language policies of JYU and AIU as ‘prevailing discursive environments’ (Seymour-Smith et al., Citation2002, p. 254) from which students may draw ideas about how to orient themselves towards their peers as language speakers. As illustrated in our analysis, multilingualism based on a monolingual view of national membership is dominant in both universities, although the notion of languaging with an attention to linguistic practices in interaction is also identified in one paragraph of JYU Language Policy. In JYU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms, Finnish is emphasized as the national language of Finland in contrast to foreign languages as international languages, and an ideological dilemma occurs between the notion of English as the international language and native-speakerism of English. This ideological landscape affords students the social categories of locals from Finland and foreigners for mutual exclusion, foreign-language- and English-speaking cosmopolitans for inclusion, and ‘native/native-like and non-native speakers’ of English for hierarchy. In AIU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms, an emphasis is put on foreign languages, especially English, as international languages in implicit contrast to Japanese as the national language of Japan, and an ideological dilemma occurs between the notion of Japanese as an international language and native-speakerism of Japanese. This ideological landscape affords students the social categories of foreign-language-, English-, and Japanese-speaking cosmopolitans for inclusion, locals from Japan and foreigners for implicit mutual exclusion, and ‘native and non-native speakers’ of Japanese for hierarchy.

In acknowledging that the notion of national language plays a significant role in developing and maintaining a modern nation-state and its people as an ‘imagined community’ (Anderson, Citation2006; see also Blommaert, Citation2010), the construction of the national language in contrast to foreign languages as international languages in JYU and AIU can be interpreted as expressing ethnolinguistic nationalism (whether it be explicit or implicit). Apparently, multilingualism based on a monolingual view of national membership is vital for universities to maintain ethnolinguistic nationalism in the process of internationalization although it has been challenged for failing to attend to the flexibility and fluidity of people’s linguistic practices (e.g. García & Li, Citation2014; Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012). The student community would thus necessarily be constructed as based on membership in different national communities.

In this respect, with the understanding that native-speakerism is grounded on the notion of national language (see Doerr, Citation2009; Hackert, Citation2009), the ideological dilemma between the notion of Japanese as an international language and native-speakerism of Japanese in AIU can be seen as displaying the tension between internationalization and ethnolinguistic nationalism. Likewise, the dilemma between the notion of English as the international language and the altered version of native-speakerism of English in JYU can be interpreted as displaying such a tension, in that English is presented as a language of higher education institutions in Western countries including Finland. This indicates that native-speakerism needs to be constructed for the maintenance of ethnolinguistic nationalism concerning language proficiency and status when the national (or institutional) language(s) is/are also seen as an international language(s) although this specific ideology has long been criticized for potential contribution to inequality among English speakers with different linguistic backgrounds (e.g. Holliday, Citation2006, Citation2015; Kabel, Citation2009; Piller, Citation2001).

However, some attempts to mitigate the presence of native-speakerism are visible in both universities. In the case of AIU, the notion of foreign language, especially English, as international languages is emphasized in the alternative language requirements for ‘native speakers’ of Japanese in the Japanese-medium program. This practice still within the scope of the notion of national language is in line with the recent argument that multilingual resources of ‘native speakers’ of English are important for enhanced communication and fairness among students in international universities where English is used as an academic lingua franca (Jenkins & Leung, Citation2019). In the case of JYU, the notion of English as the international language is also constructed against native-speakerism of English, without classifying English as a foreign language. This view of English is closer to the recent understanding of academic English as nobody’s first language (Kuteeva, Citation2014; see also Jenkins & Leung, Citation2019; Leung et al., Citation2016), which has developed and been developed by the reconceptualization of language as languaging (e.g. García & Li, Citation2014; Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012). Seemingly, JYU is attempting to put the notion of languaging into practice in their language policies although ‘English’ (a named language) still figures in their documents.

Overall, JYU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms with the emphasis on Finnish can be interpreted as reconstructing the recent discourse in Nordic countries – English as a threat to Nordic (academic) languages (Björkman, Citation2014; Bolton & Kuteeva, Citation2012; Saarinen & Taalas, Citation2017). It enables JYU, as part of a larger international community, to emphasize the need of protecting Finnish against the vitality of English in its internationalizing community where Finnish is not presented as an international language. However, English is not portrayed as a threat to Finnish; rather, it is internalized as its institutional language (see Lanvers & Hultgren, Citation2018). Meanwhile, AIU’s multilingualism/monolingualisms with the emphasis on foreign language, especially English, appears to be in line with the Japanese national discourse – English as a resource to highlight Japanese national identity (Hashimoto, Citation2013; Phan, Citation2013; see also Hashimoto, Citation2000). It allows AIU, as a mediator between the local and international community, to focus on internationalization through English. Yet, Japanese is not necessarily undermined, as indicated in the construction of Japanese as an international language and native-speakerism of Japanese.

The comparison of the language ideological landscapes in the language policies of JYU and AIU suggests that, in the process of internationalization through EMI, both multilingualism and languaging would be important discursive resources for universities as meso-level actors in language planning (Liddicoat, Citation2016; Lo Bianco, Citation2005) to cope with both maintaining ethnolinguistic nationalism for the sake of higher-level language planning and ensuring equality among students with different linguistic backgrounds. Multilingualism portrays students as members of national communities and likely creates inequalities among them, but at the same time, it can facilitate inclusion of all as cosmopolitans. In contrast, languaging can remove national categories from the student community, but it cannot contribute to the maintenance of ethnolinguistic nationalism. On international campuses where multilingualism is prevalent, students are likely to be constructed as cosmopolitans for inclusion, locals and foreigners for exclusion, or ‘native/native-like and non-native speakers’ for hierarchy through different monolingual language ideologies. This means that students as language speakers would need to negotiate different ways of being with their peers on campus, some of which might present moral and ethical dilemmas to students.

In this paper, we focused on the language policies of the two universities. However, we also identified nationalism on a broader scale and related social categories for students in the universities' policies not about language per se (e.g. the favor to those who completed their higher education in Finnish institutions in terms of proving English language proficiency in many English-medium programs of JYU; the small admission quota for foreign students in the undergraduate programs of AIU). Addressing interconnectedness of different policy areas in future research may provide further implications for university language policies as part of a bigger picture of internationalization or Englishization of higher education, and its meaning for students.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Taina Saarinen, Peppi Taalas, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mai Shirahata

Mai Shirahata is Doctoral Researcher in Intercultural Communication at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her doctoral research project focuses on language ideologies and students' identity construction in internationalizing higher education.

Malgorzata Lahti

Malgorzata Lahti works as Senior Lecturer in Communication at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has extensive experience designing and running courses in intercultural communication, and she has co-run international master’s programmes (Intercultural Communication; Language, Globalization and Intercultural Communication) offered at the department. Lahti’s research interests include interculturality and multilingualism in professional and academic contexts, critical approaches to intercultural communication, and face-to-face and technology-mediated team interaction.

References

- Airey, J., Lauridsen, K. M., Räsänen, A., Salö, L., & Schwach, V. (2017). The expansion of English-medium instruction in the Nordic countries: Can top-down university language policies encourage bottom-up disciplinary literacy goals? Higher Education, 73(4), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9950-2

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Billig, M., Condor, S., Edwards, D., Gane, M., Middleton, D., & Radley, A. (1988). Ideological dilemmas: A social psychology of everyday thinking. Sage Publications.

- Björkman, B. (2014). Language ideology or language practice? An analysis of language policy documents at Swedish universities. Multilingua, 33(3–4), 335–363. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0016

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Bolton, K., & Kuteeva, M. (2012). English as an academic language at a Swedish university: Parallel language use and the ‘threat’ of English. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(5), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2012.670241

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01207.x

- Doerr, N. M. (2009). Investigating “native speaker effects”: Toward a new model of analyzing “native speaker” ideologies. In N. M. Doerr (Ed.), The native speaker concept: Ethnographic investigations of native speaker effects (pp. 15–46). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gal, S. (2005). Language ideologies compared: Metaphors of public/private. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 15(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2005.15.1.23

- Gal, S. (2006). Migration, minorities and multilingualism: Language ideologies in Europe. In C. Mar-Molinero & P. Stevenson (Eds.), Language ideologies, policies and practices: Language and the future of Europe (pp. 13–27). Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hackert, S. (2009). Linguistic nationalism and the emergence of the English native speaker. European Journal of English Studies, 13(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825570903223541

- Hashimoto, K. (2000). ‘Internationalisation’ is ‘Japanisation’: Japan's foreign language education and national identity. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 21(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860050000786

- Hashimoto, K. (2013). ‘English-only’, but not a medium-of-instruction policy: The Japanese way of internationalising education for both domestic and overseas students. Current Issues in Language Planning, 14(1), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2013.789956

- Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60(4), 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl030

- Holliday, A. (2015). Native-speakerism: Taking the concept forward and achieving cultural belief. In A. Swan, P. Aboshiha, & A. Holliday (Eds.), (En)Countering native-speakerism (pp. 11–25). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Irvine, J. T. (1989). When talk isn’t cheap: Language and political economy. American Ethnologist, 16(2), 248–267. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1989.16.2.02a00040

- Jenkins, J. (2011). Accommodating (to) ELF in the international university. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(4), 926–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.05.011

- Jenkins, J. (2014). English as a lingua franca in the international university: The politics of academic English language policy. Routledge.

- Jenkins, J., & Leung, C. (2019). From mythical ‘standard’ to standard reality: The need for alternatives to standardized English language tests. Language Teaching, 52(1), 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000307

- Johnson, D. C. (2013). Language policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kabel, A. (2009). Native-speakerism, stereotyping and the collusion of applied linguistics. System, 37(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.09.004

- Kraft, K., & Lønsmann, D. (2018). A language ideological landscape: The complex map in international companies in Denmark. In T. Sherman & J. Nekvapil (Eds.), English in business and commerce: Interactions and policies (pp. 46–72). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Kramsch, C., & Whiteside, A. (2007). Three fundamental concepts in second language acquisition and their relevance in multilingual contexts. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 907–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00677.x

- Kuteeva, M. (2014). The parallel language use of Swedish and English: The question of ‘nativeness’ in university policies and practices. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874432

- Lanvers, U., & Hultgren, A. K. (2018). The Englishization of European education: Foreword. European Journal of Language Policy, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2018.1

- Leung, C., Lewkowicz, J., & Jenkins, J. (2016). English for academic purposes: A need for remodelling. Englishes in Practice, 3(3), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/eip-2016-0003

- Liddicoat, A. J. (2016). Language planning in universities: Teaching, research and administration. Current Issues in Language Planning, 17(3–4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2016.1216351

- Lo Bianco, J. (2005). Including discourse in language planning theory. In P. Bruthiaux, D. Atkinson, W. G. Eggington, W. Grabe, & V. Ramanathan (Eds.), Directions in applied linguistics (pp. 255–263). Multilingual Matters.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2008). Tense times and language planning. Current Issues in Language Planning, 9(2), 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664200802139430

- Lüdi, G. (2013). Receptive multilingualism as a strategy for sharing mutual linguistic resources in the workplace in a Swiss context. International Journal of Multilingualism, 10(2), 140–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2013.789520

- Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., An, J., & Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000350

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2012). Disinventing multilingualism: From monological multilingualism to multilingual francas. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 439–453). Routledge.

- Phan, L. H. (2013). Issues surrounding English, the internationalisation of higher education and national cultural identity in Asia: A focus on Japan. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2013.781047

- Phan, L. H. (2016). English and identity: A reflection and implications for future research. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 26(2), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.26.2.10pha

- Piller, I. (2001). Who, if anyone, is a native speaker? Anglistik. Mitteilungen des Verbandes Deutscher Anglisten, 12(2), 109–121.

- Piller, I. (2012). Intercultural communication: An overview. In C. B. Paulston, S. F. Kiesling, & E. S. Rangel (Eds.), The handbook of intercultural discourse and communication (pp. 3–18). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Piller, I. (2016). Linguistic diversity and social justice: An introduction to applied sociolinguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, J., & Wetherell, M. (2003). The discursive climate of singleness: The consequences for women’s negotiation of a single identity. Feminism & Psychology, 13(4), 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/09593535030134014

- Robertson, S. L., & Kedzierski, M. (2016). On the move: Globalizing higher education in Europe and beyond. The Language Learning Journal, 44(3), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2016.1198100

- Saarinen, T., & Taalas, P. (2017). Nordic language policies for higher education and their multi-layered motivations. Higher Education, 73(4), 597–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9981-8

- Seymour-Smith, S., Wetherell, M., & Phoenix, A. (2002). “My wife ordered me to come”: A discursive analysis of doctors’ and nurses’ accounts of men’s use of general practitioners. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105302007003220

- Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Routledge.

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Wetherell, M. (1996). Fear of fat: Interpretative repertoires and ideological dilemmas. In J. Maybin & N. Mercer (Eds.), Using English: From conversation to canon (pp. 36–41). Routledge.

- Wetherell, M. (1998). Positioning and interpretative repertoires: Conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse & Society, 9(3), 387–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926598009003005

- Wetherell, M., & Potter, J. (1992). Mapping the language of racism: Discourse and the legitimation of exploitation. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Wiggins, S. (2017). Discursive psychology: Theory, method and applications. Sage Publications.

- Woolard, K. A. (1998). Language ideology as a field of inquiry. In B. B. Schieffelin, K. A. Woolard, & P. V. Kroskrity (Eds.), Language ideologies: Practice and theory (pp. 3–47). Oxford University Press.

- Woolard, K. A., & Schieffelin, B. B. (1994). Language ideology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 23(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.23.100194.000415