ABSTRACT

This study examined whether institutions of higher education in the Arab world have adopted approaches that promote linguistic sustainability. Specifically, we used Q methodology to explore 30 graduates’ perceptions of whether the educational language policies in force during their tertiary education positively impacted their wellbeing after graduation. Based on their priorities, the graduates sorted 29 statements that articulated some of the social, cultural and economic impacts of their universities’ educational language policies. The results show that graduates took four distinct positions, which were given labels representing their general sentiments: We deserved better, We wanted more, It was enough but not everything and We cannot complain. This study concludes that three main linguistic areas were neglected in these graduates’ tertiary studies: language and identity, investment as a second language learning construct and parallellingualism. We maintain that higher education institutions could provide a more sustainable linguistic experience for Arab graduates by addressing these shortcomings, among others.

Introduction

Since the inauguration of ‘Our Common Future’ by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987, sustainability has become ‘the watchword for international aid agencies, the jargon of learned planners, the theme of conferences and learned papers, and the slogan of environmental and developmental activists’ (Lele, Citation1991, p. 607). The Commission (1987) defined sustainability as the ‘development [that] meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (p. 8). As a proposed holistic approach and societal goal, sustainability comprises three main dimensions – ecological, social and economic – that should be considered together to realise the desired prosperity. In all these three dimensions, sustainability is understood as the capacity to endure (Bromley, Citation2008). While the concept of sustainability has been strongly criticised as vague, ill-defined, an insubstantial and cliched platitude and a buzzword (e.g. Drummond & Marsden, Citation2005; Lele, Citation1991), the search for a sustainable development path has gained political legitimacy in many societies (De la Fuente, Citation2021).

As Stibbe (Citation2019) wrote, ‘It is often hard for people to see a connection between language and sustainability’ (p. 234). Still, many scholars have made this connection. Notable among these is Bastardas-Boada (Citation2004), who promoted ‘linguistic sustainability’, which sought intercommunication with the other without undermining the linguistic and cultural resources that identify one’s self. Bastardas-Boada (Citation2004) observed that the sustainability philosophy generally ‘seek[s] the integral development of the human being, with a humanist approach and not a purely economistic social progress’ (p. 2). Applying this sustainable logic to the linguistic reality, he wrote, ‘Just as sustainable development does not negate the development and the desire for material improvement of human societies but at one and the same time wants to maintain ecosystemic balance with nature, so ‘language sustainability’ accepts polyglottisation and intercommunication among groups and persons yet still calls for the continuity and full development of human linguistic groups’ (Bastardas-Boada, Citation2004, p. 6).

To this end, this study examines whether Arab higher education institutions have adopted such an approach to linguistic sustainability. Specifically, using Q methodology, we attempt to answer the following questions: How do graduates in Arab universities perceive the impact of the educational language policies implemented during their tertiary education on their social, cultural and economic well-being after graduation? Did such educational language policies allow graduates to intercommunicate with the other without undermining their linguistic and cultural resources? The sites of this study are Algeria and Qatar. Although their economic and political statuses differ, both are Arab countries that share a political history of being a colony or a protectorate controlled by imperial powers and a globalised moment of reclaiming themselves internationally. Perhaps more importantly in the light of this study, both countries share relatively low rankings in the Sustainable Development Report (Citation2021), placed 64th and 94th, respectively.

Still, the relevance of this study is not limited to higher education in the Arab world. Rather, this study is pertinent to the context of global higher education. Worldwide, universities are finding themselves in ‘convoluted linguistic situations that could be characterized by the pressure to manage internationalised faculties and student bodies, the imperative to prepare students to function in a globalized world, and the inevitability of adopting internationalized curricula’ (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a, p. 415). Therefore, albeit with certain particularities, the linguistic situation in higher education in the Arab world epitomises global higher education. This study aimed to contribute an empirical analysis to language policy research by investigating how ‘language matters are never just language matters’ (Civico, Citation2021, p. 196) – that is, by recognising that their causes and consequences are found in many seemingly unrelated fields.

In what follows, we first discuss the scholarly argument around sustainability and educational language policies and the connection between both terms. Next, we provide contextual background on educational language policies in both Algeria and Qatar. We then introduce Q methodology as our tool for exploring graduates’ perceptions of these policies. Finally, we present and discuss the findings of the study and provide concluding remakes.

Sustainability and educational language policy

Although this study is about ‘sustainability’, we use the term with ambivalence and caution. As Stibbe (Citation2019) argued, ‘The term sustainability and its counterpart sustainable development have a long history of use and abuse since [they] came to prominence’ (p. 234). The root of the problem is the word ‘development’. In tracing its political coinage, Esteva (Citation2010) points to American politicians at the end of World War II who wanted to consolidate and reinforce their hegemony. Specifically, when President Truman took office on 20th January 1949, he maintained that Americans ‘must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of [their] scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas’ and stressed that ‘the old imperialism, exploitation for foreign profit, has no place in our plans … What we envisage is a program of development’ (cited in Esteva, Citation2010, p. 2). At that point, an era of development was launched to serve the ‘other’, and the associated idea of ‘underdevelopment’ began. Around two-thirds of the global population was declared underdeveloped and ceased to be what they really were in all their diversity. These communities were transmogrified into an inversion of ‘developed’ reality or ‘a mirror that belittles them and sends them off to the end of the queue, a mirror that defines their identity, which is really that of a heterogeneous and diverse majority, simply in the terms of a homogenizing and narrow minority’ (Esteva, Citation2010, p. 2).

While the term ‘development’ originally referred to an alleged ‘altruistic goal of poverty reduction in poor countries through helping their economies to grow’ (Stibbe, Citation2019, p. 54), it rapidly mushroomed to create other terms. These included ‘equitable development’, with the aim of building human well-being through a fairer society, ‘sustainable development’, which confirmed that the environment should be protected, and ‘sustained growth’, focusing on international economic competition (Stibbe, Citation2015). However, behind the masks of these terms, the Global North has been maximising its own economic growth at the expense of both the Global South and the environment (Stibbe, Citation2019). Although the discussion above is a simplification, mainly due to space limitations, it serves to show how the so-called altruistic endeavours to benefit the world have been manipulated to serve the political and economic agendas of wealthy nations at the expense of other societies, other species and the ecosystems that make life (Stibbe, Citation2019).

In this study, we understand sustainability mainly in relation to intrinsic goals – that is, goals that are cherished in themselves, in contrast to extrinsic goals, such as economic growth. We follow Crompton (Citation2010) in arguing that ‘sustainability is the pursuit of intrinsically valuable goals such as human health, wellbeing, poverty reduction, peace, social justice, and the survival and wellbeing of other species, underpinned by care for the ecosystems that life depends on’ (p. 10). The question then becomes, how do educational language policies relate to such an understanding of sustainability? The following lines attempt to provide an answer.

Far earlier than others, Kaplan and Baldauf (Citation1997) considered educational language policies as forms of human resource development planning. Planning language(s) in education aims ‘to develop language abilities that a society identifies as important for social, economic, or other objectives’ (Kirkpatrick & Liddicoat, Citation2019, p. 2). In this sense, educational language policies ‘make statements about which languages will be included in education and the purposes for which those languages will be taught and learned’ (Kirkpatrick & Liddicoat, Citation2019, p. 2). Therefore, educational language policies serve to construct an anticipated future linguistic situation, with official bodies aiming to shape emerging linguistic ecologies by providing what is required to bring them to life (Liddicoat, Citation2013). Shaping the desired linguistic ecologies necessitates ‘studying the interactions between any given language and its environment’ (Haugen, Citation1971, p. 325) – that is, the language’s sociocultural ecosystem. For Bastardas-Boada (Citation2004), ‘if this ecosystem suffers no fundamental disturbances, it will tend to reproduce itself intergenerationally, even though with internal change, via self-co-construction of the codes by the new individuals’ (p. 12). Conversely, if the ecosystem registers a large and powerful enough entry of exogenous linguistic elements, then ‘there could occur a reorganisation of competencies and norms of linguistic usage, and this could lead to important evolutionary repercussions’ (Bastardas-Boada, Citation2004, p. 12).

In an era of ‘supercomplexity’ in higher education (Barnett, Citation2000), especially in the Global South, the sociocultural ecosystem surrounding and impacting educational language policies has registered the entry of considerable exogenous linguistic elements. These include the glottophagic expansion of dominant languages (Phillipson, Citation2018), toxic doses of bilingualism (Beltran, Citation2013) or unilingualism (Smit, Citation2018), hostility towards indigenous language teaching and learning (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020b) and other economic, political and educative measures of globalisation, internationalisation and technological innovations (Bastardas-Boada, Citation2004). In effect, the entry of these exogenous linguistic elements has led to a perennial question of language planning in higher education (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a; Liddicoat, Citation2016).

Some argue that universities must abandon local language(s) and adopt global language(s) if their attendees are to advance academically and economically. Others argue that the focus should be on maintaining linguistic diversity and distinct collective identities in higher education as a way of ‘avoiding the poverty and anonymity that are the destination of disorganisation of the traditional subsistence ecosystem, and of the continuance of the knowledge and wisdom each culture has produced’ (Bastardas-Boada, Citation2004, p. 4). At first, these perspectives may seem irreconcilable. However, the ultimate goal of achieving the sustainability of the sociocultural ecosystem encompassing educational language policies in higher education necessitates taking both perspectives into account. In some universities, local languages are used to teach non-science specialisations, while global languages are used to teach science specialisations (Annamalai, Citation2010). In other universities (especially Nordic universities) policies of parallel language use (or parallelism) are enforced. ‘The parallel use of language refers to the concurrent use of several languages within one or more areas. None of the languages abolishes or replaces the other; they are used in parallel’ (Gregersen, Citation2018, p. 9). Such policies represent a shift in the field of educational language policy from a focus on psycholinguistic models to the sociological dimensions of language learning and teaching. That is, the focus is not limited to linguistic input and output in language teaching and learning, but it also includes the relationship between university students and the larger social world (Norton, Citation2013).

To conclude, educational language policies can be seen as forms of human resource development planning intended to shape a desired and anticipated linguistic ecology in relation to intrinsic goals. Achieving sustainability of educational language policies mainly requires creating a harmony between the different endogenous and exogenous linguistic components of the surrounding sociocultural ecosystem. Accordingly, achieving sustainable educational language policies requires a ‘constant iteration between [educational institutions] and the nation, policy and practice’ (Lo Bianco & Aliani, Citation2013, p. 132) – in other words, the integration of bottom-up perspectives with top-down directives. In effect, this will positively influence the social, cultural and economic well-being of the attendees of higher education (Bastardas-Boada, Citation2000).

Educational language policy in Algerian and Qatari universities

In the modern sense, the higher education system in both Algeria and Qatar is relatively new. It was only after independence in 1963 that the Algerian government began to rebuild its higher education system (Le Roux, Citation2017). Similarly, in Qatar, the first national university was established in 1973, after independence. The early results of tertiary education in both Algeria and Qatar were notable (UNESCO, Citation2018). Not only did the higher education system provide the high-level skills necessary for the labour market, but it also empowered domestic constituencies in building societal institutions, increased social capital and promoted social cohesion.

Until the 1980s, both countries had invested heavily in free higher education, relaying on Arabic as the medium of instruction, with reasonably positive results (UNESCO, Citation2018). Despite this relative success, since the 1990s, certain criticisms have been levelled against tertiary education in both countries, mainly by international organisations and think tanks. The higher education systems in both countries were described as lacking quality, with outdated and traditional methods of instruction (UNESCO, Citation2018). Deficiencies in the management, effectiveness and efficiency of these systems were described (World Bank, Citation2017). It has been argued that basic learning takes place in the mother tongue; however, ‘the modern world also requires relative mastery of at least one secondary language, either French or English, especially … for the labor market that tends to be more and more international’ (UNESCO, Citation2018, p. 12).

In 2004, both Algeria and Qatar launched sweeping educational reforms. Algeria moved away from the Napoleonic educational system to the LMD system: 3-year Bachelor, 2-year Master and 3-year Doctorate (MERIC-NET, Citation2019). Although both Arabic and French were still considered a necessity (Djebbari & Djebbari, Citation2020), English were steadily promoted and imposed for various educational and economic reasons. That is, French was seen as a ‘reference point, a stimulant that would force Arabic to be on the alert’ (Djebbari & Djebbari, Citation2020, p. 42), while English was considered ‘the magic solution to all possible ills including economic, technological and education ones’ (Djebbari & Djebbari, Citation2020, p. 42). Likewise, Qatar reformed its public higher education system with a focus on English as the medium of instruction. However, ‘a decade after the reform began … English as the medium of instruction [in Qatar’s public higher education] proved to be ineffective as it created a barrier for students’ success’ (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a, p. 418). As a result, the government reverted to Arabic, issuing a law declaring it the medium of instruction at public universities.

The impact of these educational reforms on educational language policies has been thoroughly explored in both countries, with many similar conclusions. Scholars have reported a linguistic gap between students at public high schools, who are taught in Arabic, and science programmes, which are taught in English / French (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a; Bouherar & Ghafsi, Citation2021). Additionally, in both countries, a characteristic divide has been established between teaching natural, technical and medical sciences in English/ French and teaching human and social sciences in Arabic (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a; Bouherar & Ghafsi, Citation2021). In the Qatari context, one result of such a division is that, for the 2019–20 academic year, 57% of the graduates in the colleges of pharmacy and engineering were not satisfied with their Arabic-language reading and writing skills, whereas 55% of graduates in Islamic studies colleges were not satisfied with their English-language reading and writing skills (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a). Likewise, in the Algerian context, Bouherar and Ghafsi (Citation2021) discuss high school students’ failure at university, attributing the cause to the French language barrier. For them, high school students’ lack of French language competencies, having studied in Arabic medium schools, prevent them from pursuing scientific majors that are available in French only in Algerian public higher education.

Although the linguistic situation in higher education may seem identical in Algeria and Qatar, there is a difference that makes the Algerian context peculiar. Algeria’s Berber population has been protesting for Tamazight language rights. Although Tamazight was officially recognised as an official language four times through constitutional amendments (in 2002, 2008, 2016 and 2020), a fierce linguistic war has been going on between Islamists defending the Arabic language and reformists promoting Tamazight as a way of preserving the country’s Berber identity and fostering multiculturalism and individual rights in the educational system. It has also been argued that the educational language policy of Algeria’s universities does not facilitate the employability of its graduates outside their country. That is, with a Francophone education, Algerian graduates may not have equal chances of being recruited compared to their Anglophone counterparts (Bouherar & Ghafsi, Citation2021).

These issues have been the central concern of several scholarly endeavours that investigated how a linguistic balance can be attained and sustained in public higher education. These endeavours have included identifying the social perspectives associated with several language-in-education policy options in higher education (Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020a), documenting clashes between local and global languages (Bouherar & Ghafsi, Citation2021) and exploring university students’ perceptions of the role of local and global languages in their educational careers as well as the importance of each language in their futures (Ellili-Cherif & Alkhateeb, Citation2015; Mustafawi & Shaaban, Citation2018). The results of these studies reveal a preference for mother-tongue instruction despite the awareness that it could jeopardise graduates’ employment chances and future studies.

Methodology

To explore graduates’ perceptions of whether educational language policies implemented during their university education positively impacted their social, cultural and economic well-being after graduation, we used the Q methodology (henceforth Q). Q was developed in 1935 by William Stephenson, who was concerned with establishing a scientific method of studying human subjectivity, which simply refers to ‘a person’s idiosyncratic point of view’ (Good, Citation2010, p. 213). Stephenson’s basic idea was to draw a distinction between the conventional factor analysis used to correlate traits or test items in R-methodology (e.g. surveys and questionnaire), and correlating persons in Q. In concrete terms, ‘Q-methodology applies to a population of tests or traits, with persons as variables; R-methodology to a population of persons, with tests or traits as variables’ (Good, Citation2010, p. 214). Over the years, Q has earned all the marks of an established scientific practice (Good, Citation2010; Watts & Stenner, Citation2012).

A Q study begins with developing a Q-sample derived from a concourse, which is a population of opinion statements on a particular topic of interest (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). The Q-sample contains a number of Q-statements; each should articulate a subjective opinion around the issue under investigation. Then, participants (i.e. P-set) are strategically recruited and asked to rank the Q-statements based on the condition of instruction (i.e. research question). The ranking process (i.e. Q-sorting activity) is carried out using a quasi-normal distribution grid (e.g. from −5 to +5), which specifies the number of Q-statements that can be placed in each column (Good, Citation2010). Then, the resulting Q-sorts are analysed using a specialised computer package (e.g. PQMethod), which correlates each Q-sort with every other Q-sort, resulting in a correlation matrix (Good, Citation2010). Factor analysis is then used to extract a number of factors, each representing a shared point of view among a group of participants. Interpretation of these points of view means bringing statistical factors to life, that is, into social narratives, discourses, or shared perspectives (Webler et al., Citation2009). The following sections explain how these stages were conducted in this study.

Q-sample

As mentioned earlier, the Q-sample is a selective portion of a larger concourse. It includes a number of Q-statements; each articulates a subjective opinion on the issue under investigation, and all will be ranked by the research participants. To develop the Q-sample in this study, we first needed to define a concourse that included a number of ‘messages or communications’ about the topic under investigation (Stephenson, Citation1986, p. 43). Stephenson (Citation1986) emphasised both the conversational and informational qualities of a concourse. Therefore, we first conducted two focus group sessions with a group of graduates from Algerian and Qatari universities (n = 10). During the focus group sessions, graduates were asked to respond to the following questions:

Can you describe your mastery level of the Arabic and English/French languages before enrolling in college?

Can you describe your experience of learning in Arabic and/or English/French during your tertiary education?

Can you describe your mastery level of the Arabic and English/French languages after graduation?

Can you describe how your level of mastery of the Arabic and English/French languages acquired from your tertiary education contributed to enhancing (or not) your communication with members of your society?

Can you describe how your level of mastery of the Arabic and English/French languages acquired from your tertiary education contributed (or not) to finding a job?

Is there anything else you would like to mention regarding your linguistic experience during your tertiary education?

The graduates’ responses were transcribed, establishing the ‘conversational’ element of the concourse. We then conducted extensive item sampling by reviewing the relevant literature, which functioned as the ‘informational’ element in the concourse (e.g. Alkhateeb et al., Citation2020b; Bouherar & Ghafsi, Citation2021; Ellili-Cherif & Alkhateeb, Citation2015; Mustafawi & Shaaban, Citation2018). This resulted in 121 Q-statements, which had to be culled to reach a balanced and representative Q-sample. This necessitated, as Lo Bianco (Citation2015) advised, discarding repetitious and ephemeral items. This resulted in 29 Q-statements, each was given an identification number, reformulated in Arabic and printed on Q-sort cards that resembled playing cards. It should be noted here that ‘The exact size of the final Q set will, to a great extent, be dictated by the subject matter itself’ (Watts & Stenner, p. 61). Stephenson used as few as 20 in his play theory book (Stephenson, Citation1967). His first Jung Q sample, on the other hand, contained 80 (Stephenson, Citation1953, p. 83), but his second Jungian Q sample contained 121 (Stephenson, Citation1953, p. 187). Consequently, the number of statements in Q studies have ranged widely, from as few as 20 or so upwards to more than 100. We then piloted the Q-sample with two graduates to ‘ensure that statements are comprehensible for the respondents and to identify any unforeseen problems’ (Zabala et al., Citation2018, p. 1188). Feedback received from piloting facilitated the revision and adjustments of the Q-sample, after which the Q-sample was finalised (see Appendix 1).

Q-sorting activities

The selection of participants in Q research can be described as intentional and strategic sampling rather than opportunity sampling (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). The main principle in such strategic sampling is that participants’ viewpoints matter in relation to the subject under investigation (Watts & Stenner, Citation2012). Also, as Watts and Stenner (Citation2012) argued, ‘Q does not need a large number of participants, and it is not interested in headcounts. It just needs enough participants to establish the existence of its factors’ (p. 88). With these criterions in mind, we used the snowball sampling technique to select graduates. That is, we asked every graduate we have met during the focus group discussions to suggest a former colleague from their university or other universities with a similar perspective on educational language policy, and a former colleague with a different perspective on educational language policy. This resulted in a group of 30 graduates from different universities in both Algeria (n = 15) and Qatar (n = 15), with different specialisations, graduated between the years 2000 and 2022. provides information about these universities as well as the number of participating graduates from each university.

Table 1. Universities list.

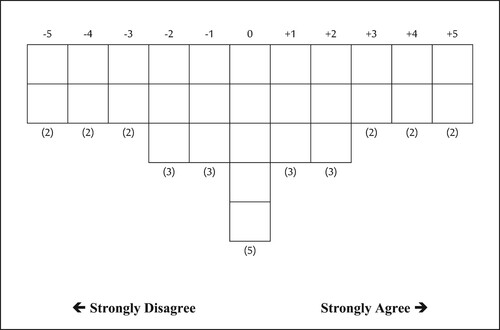

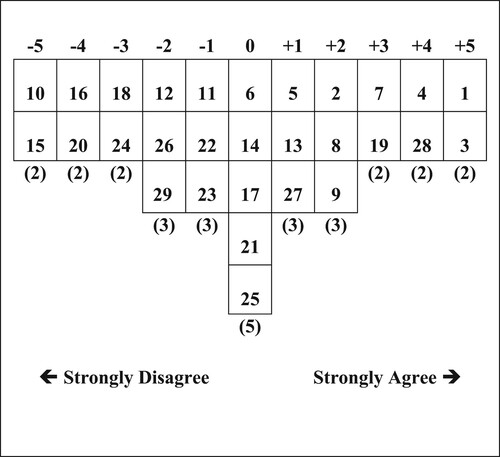

Each graduate met face-to-face with one of the researchers in this study. Before the sorting activities started, we conducted some ethical formalities (i.e. participants signed consent forms) and obtained some demographic information. Each graduate was then given a blank grid and 29 Q-statements in a signal pile. As for the grid, we used an 11-point sorting grid. The values ranged from −5 (Most disagree) to +5 (Most agree) (see ). Regarding the Q-statements, we explained to the participating graduates that each statement articulated a subjective opinion about the issue under investigation and asked them to rank these statements on the grid based on the following condition of instruction: Tertiary education often provides students with a language experience. These cards present some opinions on such experiences. With which opinions do you agree, with which do you disagree, and about which do you feel uncertain? Upon the completion of sorting, the graduates were asked to elaborate on their choices of items at +5 and −5 and their responses were transcribed for further analysis.

Analytical procedures

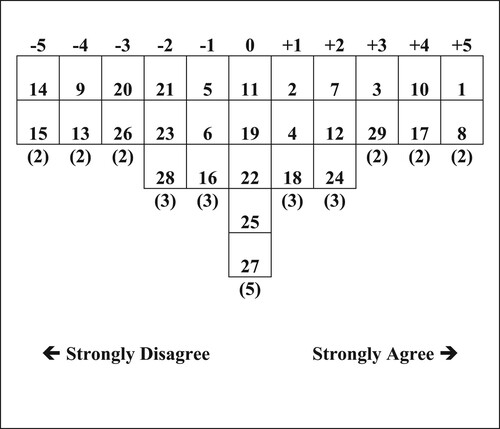

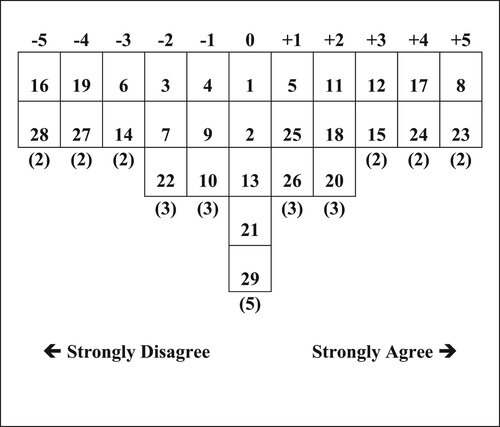

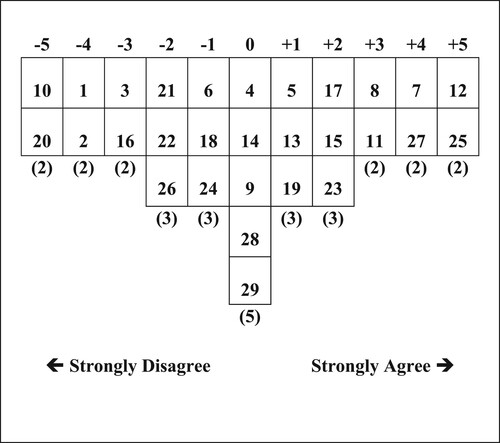

The 30 completed Q-sorts were statistically analysed using PQMethod software (Schmolck, Citation2014). The software facilitated computing intercorrelations among Q-sorts, which were then factor analysed with centroid factor analysis and rotated analytically (Varimax). This led to a four-factor solution (F-1, F-2, F-3, and F-4), explaining 46% of the opinion variance. To calculate each Q-sort’s significance at the p < 0.01 level, we used Brown’s (Citation1980) equation: 2.58× (1÷√the no. of items in the Q-set). Factor loadings of at least ± 0.50 were significant at the p < 0.01 level. Based on this, 28 Q-sorts loaded significantly on one of the four factors that emerged, while two were null cases. The four-factor solution indicates that there are four distinct groups of graduates identified in this study; hence, four distinct perspectives need to be interpreted. To enable such an interpretation, a factor array was constructed for each of the emerging factors. ‘A factor array is, in fact, no more or less than a single factor exemplifying Q sort configured to represent the viewpoint of a particular factor’ (Sage, Citation2018, p. 9). show the factor arrays for the emerging factors in this study, while presents a quantitative summary of the emerging factors.

Table 2. Quantitative summery of the emerging factors.

Results

As mentioned earlier, four factors (F-1, F-2, F-3, and F-4) were extracted; each represents a social perspective shared by a group of graduates on the educational language policies implemented during their tertiary education. In the coming sections, we provide a qualitative interpretation of these social perspectives, which are presented in the following way:

For each social perspective, we gave a label that ‘provide[s] readers with a shorthand identification of what the perspective is about’ (Zabala et al., Citation2018, p. 1189).

Presenting each social perspective, we provide a table that specifies some of the demographic information of the graduates associated with that perspective.

In presenting each social perspective, we used Q-items as well as their factor ranking to provide a comprehensive narrative.

In presenting each social perspective, we used comments provided by graduates during the Q-sorting activities to further elucidate their standpoints.

F-1: We deserved better

Nine graduates loaded significantly on F-1, accounting for 13% of the explained opinion variance. These graduates come from different universities in both Algeria and Qatar and graduated in the period between 2000–2021. As shown in , seven out of nine of these graduates specialised in social sciences or humanities majors.

Table 3. F-1 Loadings.

Those graduates strongly believed that their pre-university schooling was the main reason for their good mastery of the Arabic language (Q-item 1: + 5). Pre-university schooling, in their contexts, was more focused on developing and implementing Arabic than a second global language (French in Algeria or English in Qatar) (Q-item 4: + 1). Additionally, they considered themselves auspicious because their families attached great significance to enhancing their Arabic language competencies (Q-item 3: + 3). Consequently, they grew confident with their Arabic linguistic skills to the point of ostentatiousness that their skills were immune from possible deterioration (Q-item 26: – 3). In brief, both their pre-schooling education and their families sowed the seeds for their organic attachment to the Arabic language. Perhaps this what drives them to demand the implementation of language policies that support the teaching and use of the Arabic language as a mother tongue, both at the university and market levels (Q-item 17: + 4; Q-item 12: + 2). Still, upon embarking on tertiary education, these graduates needed something new. Nevertheless, they aptly noted two major directions in their universities’ educational language policies. The first promotes the Arabic language in the social sciences and humanities, while the second endorses a second global language in the natural sciences (i.e. French in Algeria and English in Qatar) (Q-item 8: + 5). Most of these graduates were trapped as social science and humanities majors in the first direction. One corollary of such policies, their Arabic and second language repertoires (i.e. French or English), were not equally enhanced (Q-item 9: – 4). That is, the Arabic language was more present in their academic journeys. Although these graduates acknowledged that their second language skills improved slightly during their college studies (Q-item 7: + 2), this improvement did not meet their academic needs and expectations (Q-item 10: + 4). For them, this issue could have been resolved if they had received linguistic assistance from student support centres during the tertiary education. Nonetheless, such support was not available (Q-item 14: – 5). What made things even worse for these graduates was that they did not acquire second language skills in parallel with learning other subjects, that is, in natural settings (Q-item 13: – 4). This deprived them of the chance to understand the social dynamics that govern the second language’s use. The outcome was that these graduates managed to join the local labour market but were unequipped for a more linguistically diverse global one (Q-item 24: + 2). Consequently, after graduation, they needed to learn a different language (Q-item 29: + 3) (mainly English for Algerian graduates) .

Table 4. F-2 Loadings.

Table 5. F-3 Loadings.

Table 6. F-4 Loadings.

F-2: We wanted more

Six graduates loaded significantly on F-2, accounting for 12% of the explained opinion variance. Most of these graduates came from Algerian universities specialising in the social sciences or humanities and graduated in the period between 2012–2021.

Similar to their counterparts who loaded on F-1, graduates loaded on the F-2 factor distinctly noted that their universities promoted the Arabic language in social sciences and humanities majors while fostering English/French in the sciences (Q-item 8: + 5). Because of this, these graduates believe that their universities failed to futureproof their employability. Drawing on their experiences after graduating, these graduates asserted that an excellent proficiency level in the Arabic language was not what the marketplace looked for. Rather, English or French linguistic skills are the highest in demand (Q-item 23: + 5). Graduates loaded on this factor believe that their universities should have planned to produce global market-ready graduates. However, their universities’ language policies failed to close the gap between their linguistic skills and industry expectations. In this case, the linguistic skills for graduates here were insufficient to obtain a good career (Q-item 28: – 5) in a global market (Q-item 24: + 4). Still, this is not to suggest that their Arabic skills were better. On the contrary, these graduates noticed a partial deterioration in their Arabic language proficiency (Q-item 15: + 3). For this, they blamed old-fashioned methods of teaching the Arabic language. In short, graduates here believe that their tertiary education failed to enrich both their Arabic and English/French skills (Q-item 6: – 3; Q-item 7: – 2). Adding insult to injury, graduates here denied receiving any linguistic support services from student learning support centres (Q-item 14: – 3) that could have enhanced both their learning experiences and academic successes. According to these graduates, what could have been improved is that language policies that support the teaching and use of the Arabic language at both universities and in the labour market were implemented (Q-item 17: + 4; Q-item 12: + 3). In parallel, efficient multilingual education was provided. The latter issue is conspicuous for graduates loaded on this factor, especially since their linguistic repertoire obtained throughout their tertiary education failed them immensely. That is, these graduates were unable to communicate better with others from different linguistic backgrounds in their communities after graduation (Q-item 19: – 4) and were negatively and significantly impacted in their employability (Q-item 27: – 4). After graduation, these graduates could not repair the ‘linguistic’ damage by enrolling at language centres, as they were already entangled with several new social and professional engagements (Q-item 16: – 5).

F-3: It was enough, but not everything

Seven graduates loaded significantly on F-3, accounting for 11% of the explained opinion variance. Most of these graduates came from the Qatari university and varied in their specialisations between social sciences, humanities, and sciences majors. They graduated in the period between 2013–2022.

Similar to their counterparts who loaded on F-1 and F-2, graduates loaded on the F-3 factor also noticed that their universities’ language policies had two different directions: emphasising the Arabic language in social sciences and humanities majors, while relying on English/French when teaching scientific majors (Q-item 8: + 3). Graduates loaded on this factor were among those who had to walk through the latter direction. That is, their tertiary education was more oriented towards using English/French, while the Arabic language was neglected (Q-item 11: + 3). Still, these graduates believe that they have ‘linguistically’ benefited from their college studies (Q-item 20: – 5). Their tertiary education enhanced their second language competencies (Q-item 7: + 4), although at the expense of their Arabic language skills (Q-item 6: – 1). Graduates loaded on this factor strongly affirmed that their acquired English/French linguistic skills met their academic expectations and needs (Q-item 10: – 5). Still, to be recruited, they had to enhance their communicative skills in their specific field or occupation (Q-item 25: + 5). For this, they improved their specific field speaking and writing skills independently, and without the need to enrol at language centres (Q-item 16: – 3). In doing so, these graduates were able to maintain the linguistic skills that they acquired from their tertiary education and boost their employability (Q-item 27: + 4). However, they could not celebrate their success in this regard, as their Arabic language was missing. The language was also absent in their pre-university schooling (Q-item 1: – 4), neglected by their local communities (Q-item 2: – 4), and abandoned by their families (Q-item 3: – 3). For this, graduates loaded on this factor emphatically believed that their universities should have compensated for their ‘linguistic’ loss, through emphasising better teaching of the Arabic language (Q-item 12: + 5).

F-4: We cannot complain

Six graduates loaded significantly on F-4, accounting for 10% of the explained opinion variance. Most of these graduates came from the Qatari university and pursued diverse specialisations. They graduated in the period between 2014–2022.

These graduates believed that their tertiary education enhanced their Arabic and English/French linguistic repertoires equally (Q-item 9: + 2). They were linguistically prepared for university, as their pre-university schooling had contributed greatly to their Arabic language competencies (Q-item 1: + 5; Q-item 4: + 4). Moreover, their families contributed substantially to enhancing their Arabic language skills (Q-item 3: + 5), shielding them from deterioration (Q-item 15: −5). At the same time, their tertiary education enhanced their English/French language skills (Q-item 7: + 3). Graduates loaded on this factor emphatically refuted being disappointed with their second language competencies (Q-item 10: −5) or having to enrol in language schools to improve them (Q-item 16: −4). Their tertiary education helped them develop considerable linguistic skills (Q-item 20: −4) by offering them access to up-to-date academic resources (Q-item 18: −3), which enabled them to communicate better with members of their communities after graduation (Q-item 19: + 3) and join good jobs (Q-item 28: + 4) in a global market (Q-item 24: −3). The key to this ‘linguistic’ satisfaction was that these graduates studied their second language in parallel with other field subjects, which enabled them to use the acquired linguistic skills in natural settings (Q-item 13: + 1). Graduates loaded on this factor do not believe that their universities needed to emphasise better teaching of Arabic (Q-item 12: – 2), as the language for them will take care of itself. That is, like many Arabs, they believe that the Arabic language, the symbol of Islam and the language of the Holy Quran, is immune from change in the lives of Muslims and Arabs. In short, graduates loaded on this factor lived happy ‘linguistic’ lives during their tertiary education and were relatively able to maintain their linguistic skills after graduation (Q-item 27: + 1).

Discussion

Through Q methodology, we explored graduates’ perceptions of the impact of educational language policies implemented during their tertiary education on their social, cultural and economic well-being in both Algeria’s and Qatar’s higher education systems. The results demonstrate that the pre-university linguistic readiness of these graduates varied (see factor ranking for Q-items 1, 2, 3 & 4), which contributed to their different linguistic experiences (see factor ranking for Q-items 6, 7 & 9). Consequently, the impact of their linguistic experiences on their overall well-being diverged significantly (see factor ranking for Q-items 19, 20 & 27). The question then becomes: to what extent were the educational language policies implemented during these graduates’ tertiary studies sustainable. Answering the previous question requires returning to the general three-step formula for linguistic sustainability proposed by Bastardas-Boada (Citation2004): Maintain the ‘linguistic’ roots, nurture new ‘linguistic’ branches and create harmony between the ‘roots’ and the ‘branches’. In the following sections, we discuss whether the examined educational language policies adhered to this formula for linguistic sustainability.

Maintain the ‘linguistic’ roots: language and identity

The graduates who participated in this study unanimously believed that the educational language policies implemented during their tertiary education had failed to enhance their Arabic language skills (Q-item 6: – 1, – 3, – 1, 0). Hence, most felt that their universities should have emphasised better teaching of the Arabic language as their mother tongue (Q-item 12: + 2, + 3, + 5, – 2), urging the implementation of language policies to support the teaching and use of the Arabic language at universities and in the labour market (Q-item 17: + 4, + 4, + 2, 0). Perhaps more crucially, graduates believed that the educational language policies implemented during their tertiary studies were unreliable or insignificant sources to help maintain and promote their Arabic identities (Q-item 21: – 2, 0, – 2, 0).

Issues of identity are central to the sociolinguistic field (Norton, Citation2013) and, therefore, crucial constructs in educational language planning. In sociolinguistic research, identity is defined as ‘how a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is structured across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future’ (Norton, Citation2013, p. 45). As this definition suggests, identity ‘never signifies anything static, unchanging or substantial, but rather always an element situated in the flow of time, ever changing, something involved in a process’ (Wodak et al., Citation1999, p. 11). Identity is continuously reconstructed and negotiated in a bilateral relationship between a structured result (the state and its agencies) and a forming force (the habitus of social agents) (Bourdieu, Citation1986). In any given society, this dynamic between a ‘structured result’ and a ‘forming force’ serves to embellish cultural and social reproductions in a Bourdieuan sense. If a given structured result (i.e. the university in this study) fails to assume (or abuses) its responsibility of feeding cultural and social reproductions, individuals then search for and claim alternative and more powerful identities (Norton, Citation2013). In such a case, the sociocultural ecosystem may suffer fundamental disturbances and exogenous alternations, losing its capacity to sustain. To avoid such loss, universities, among other educational agencies, need to sustain collective and individual identities through broader and more coherent curricula in which a specific language, along with its literature, arts and culture, is taught innovatively as a continuous whole.

Nurture new ‘linguistic’ branches: investment as a second language learning construct

Although most graduates who participated in this study acknowledged that their tertiary education enhanced their second language skills (Q-item 7: + 2, – 2, + 4, + 3), for some, this enhancement did not meet their academic expectations and needs (Q-item 10: + 4, – 1, – 5, – 5). For others, it was insufficient to join the global linguistically diverse market (Q-item 24: + 2, + 4, – 1, – 3). Hence, to be recruited, some graduates had to improve their second language proficiencies after graduation (Q-item 25: 0, + 1, + 5, 0).

So why do the results vis-à-vis graduates’ second language learning experiences vary considerably across the emerging perceptions? Norton’s scholarly work (Citation2000; Citation2001; Citation2013) provides a possible answer. Theorising the multifaceted relationship between second language learners and the social world, Norton concluded that motivation, as a psychological construct, is insufficient in explaining how second language learning takes place. She turned our attention away from the conventional question ‘Are students motivated to learn a second language?’ to ‘Are teachers and students invested in the second language practices of the classroom or community?’ (Darvin & Norton, Citation2015, p. 37). While earlier research relying on dichotomies that define the learner as motivated or unmotivated, anxious or confident, introvert or extrovert assumed that second language learning is merely a product of motivation, Norton (Citation2013) showed that learners invest in second language learning when it assists them in acquiring a wider range of symbolic and material resources, which will in turn increase their cultural capital and social power. At the same time, the extent to which second language learners are able to invest in a target language and claim legitimacy as speakers is contingent on how power is negotiated in different societal or classroom fields. That is, social factors can either facilitate or inhibit second language learning. The findings of this study show that social factors, represented by universities’ educational language policies, have been invested in second language learning for students specialising in natural, technical and medical sciences, while students specialising in social sciences and humanities have been denied this investment. This point is further discussed in the following section.

Create harmony between the ‘roots’ and the ‘branches’: parallellingualism

The graduates who participated in this study unanimously asserted that their universities’ language policies were mainly divided between promoting Arabic in the social sciences and humanities majors and fostering English or French in the scientific majors (Q-item 8: + 5, + 5, + 3, + 2). These graduates were unappeased by linguistic assistance from student learning support centres, intended to provide comprehensive academic support services to university students (Q-item 14: – 5, – 3, 0, 0). Hence, for most of them, their tertiary studies failed to enhance their first and second language repertoires equally (Q-item 9: – 4, – 1, 0, + 2).

Research demonstrates that not only are global languages (i.e. English or French) more widespread in scientific than in humanities specialisations, but there is also a trend for these global languages to be instrumentally constructed in such majors (Hultgren, Citation2014). It has also been argued that associating local languages with non-science specialisations has negative impacts on the development of these languages as vehicles of scientific knowledge (Annamalai, Citation2010). The question then arises: is there a way to reconciliate the coexistence of two languages (first local and second global languages) in all majors to provide equal opportunities for academic success, greater communicative scope and cultural integration? A possible answer lies in a policy of parallellingualism. Parallellingualism refers to ‘the concurrent use of several languages within one or more areas. None of the languages abolishes or replaces the other; they are used in parallel’ (Nordic Council, Citation2007, p. 93). In an internationalised and globalised era in higher education, several universities (especially Nordic) have developed and implemented policies of parallellingualism to avoid the ‘domain loss’ of local languages and allow them to remain ‘society bearing’ – that is, fully functional in each register and domain (Hultgren, Citation2014). While the concept of parallellingualism tends to lack clarity (Harder, Citation2008), Phillipson (Citation2018) has argued that parallellingualism can be seen as ‘a recipe for raising language awareness and ensuring a reciprocal dialectic between the national language and [global languages such as] English [or French]’ (p. vi) – that is, a recipe for linguistic sustainability.

Conclusion

Through Q methodology, this study investigated Algerian and Qatari graduates’ perceptions of whether educational language policies implemented during their tertiary education positively impacted their social, cultural and economic well-being after graduation. The overall aim was to understand the influence of these educational language policies and what this impact says about linguistic sustainability’s future in higher education in both countries. The results can be summarised as follows.

On one hand, as this study examined the linguistic ecologies of postcolonial and globalised higher education in both Algeria and Qatar, it confirms that Arabic as the first and national language is positioned vis-à-vis global languages such as English/French as either the language of ‘becoming’ (in need of nominal promotion) or the language of times past (in need of preservation), but never as the language of scientific knowledge. Such a position must be reconsidered to further epistemic justice and sustainable impact. On the other hand, although both Algeria and Qatar kept their colonial languages in their higher education systems, English/French is either insufficiently taught – and thus not learned – or selectively taught to certain student groups (i.e. those enrolling in science majors), despite their necessity in today’s globalised world. Moreover, educational language policies, especially in the Algerian higher education, are unable to accommodate diversity, protect the minority rights (i.e. Berber) and defuse tensions, thus incapacitating graduates to communicate effectively with their social environment. Taken together, these findings suggest that both countries’ linguistic sustainability in higher education is threatened by restrictive educational language policies. Harmonising the local and global linguistic codes requires ecological interventions that do not force the languages’ sociocultural ecosystems to act in a highly prescribed way. Rather, realising linguistic sustainability in higher education in both Algeria and Qatar (and likely elsewhere) requires educational language planning that encourages the spontaneous development of the different linguistic elements. We conclude by arguing, as Pflepsen (Citation2016) noted, that holistic and effective language planning in educational institutions requires a student-oriented approach in which relevant situation analysis (or a mapping exercise) is conducted. This may include gathering information about the actual needs and practices of students.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hadeel Alkhateeb

Hadeel Alkhateeb is an Associate Professor of Language Policy and Language Planning at the College of Education at Qatar University where she has been a faculty member since 2009. Hadeel completed her Ph.D. at the University College of London. Her research interests include: language in education policies, educational policy in Arab higher education, linguistic imperialism, and Q-methodology.

Salim Bouherar

Salim Bouherar is an Associate Professor of English at Setif 2 University, Algeria. His research interests include the comprehension process of idioms, teaching materials of English as a second/foreign language, linguistic and cultural imperialism, critical pedagogy, and language planning and policy.

References

- Alkhateeb, H., Al Hamad, M., & Mustafawi, E. (2020a). Revealing stakeholders’ perspectives on educational language policy in higher education through Q-methodology. Current Issues in Language Planning, 21(4), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2020.1741237

- Alkhateeb, H., Romanowski, M., Du, X., & Cherif, M. (2020b). The reconstruction of academic identity through language policy: A narrative approach. Asian Englishes, 23(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2020.1785184

- Annamalai, E. (2010). Medium of power: The question of English in education in India. In J. Tollefson, & T. Amy (Eds.), Medium of instruction policies: Which agenda? Whose agenda? (pp. 177–194). Routledge.

- Barnett, R. (2000). Realizing the university in an age of supercomplexity. SRHE; Open University Press.

- Bastardas-Boada, A. (2000). Language planning and language ecology. Towards a theoretical integration. Symposium: 30 years of ecolinguistics, Graz, Austria. http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/151317/1/Language-Planning-and-Language-Ecology-Towards-a-theoretical-integration3.pdf

- Bastardas-Boada, A. (2004). Towards a ‘language sustainability’: Concepts, principles, and problems of human communicative organisation in the twenty-first century. Forum de les Cultures 2004: Dialogue on linguistic diversity, sustainability and peace. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333784235

- Beltran, C. (2013). Challenges of bilingualism in higher education: The experience of the languages department at the Universidad Central in Bogotá. Colombia. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 7, 245–258. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1062582.pdf

- Bouherar, S., & Ghafsi, A. (2021). Algerian languages in education: Conflicts and reconciliation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood.

- Bromley, D. W. (2008). Sustainability. The New palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity. Yale University Press.

- Civico, M. (2021). Language policy and planning: A discussion on the complexity of language matters and the role of computational methods. SN Social Sciences, 1(8), 197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00206-6

- Crompton, T. (2010). Common cause: The case for working with our cultural values. WWF-UK. http://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/common_cause_report.pdf

- Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2015). Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000191

- De la Fuente, M. (2021). Education for sustainable development in foreign language learning: Content-based instruction in college-level curricula. Routledge.

- Djebbari, Z., & Djebbari, H. (2020). Language policy in Algeria: An outlook into reforms. Al- Lisāniyyāt, 26(1), 39–53.

- Drummond, I., & Marsden, T. (2005). The condition of sustainability. Routledge.

- Ellili-Cherif, M., & Alkhateeb, H. (2015). College students’ attitude toward the medium of instruction: Arabic versus English dilemma. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3(3), 207–213. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2015.030306

- Esteva, G. (2010). Development. In W. Sachs (Ed.), The development dictionary: A guide to knowledge as power (2nd ed) (pp. 55–73). Zed Books.

- Good, J. (2010). Introduction to William Stephenson’s quest for a science of subjectivity. Psychoanalysis and History, 12(2), 211–243. https://doi.org/10.3366/pah.2010.0006

- Gregersen, F. (2018). More parallel, please: Best practice of parallel language use at Nordic Universities: 11 recommendations. Nordic Council of Ministers. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1203291/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Harder, P. (2008). What is parallel language use? http://cip.ku.dk/om_parallelsproglighed/oversigtsartikler_om_parallelsproglighed/hvad_er_parallelsproglighed/

- Haugen, E. (1971). The ecology of language. The Linguistic Reporter, 25, 19–26. Reprinted in Haugen 1972: 324-329.

- Hultgren, A. (2014). English language use at the internationalized universities of Northern Europe: Is there a correlation between Englishisation and world rank? Multilingua, 33(3-4), 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0018

- Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B. (1997). Language planning: From practice to theory. Multilingual Matters.

- Kirkpatrick, A., & Liddicoat, A. (2019). The Routledge international handbook of language education policy in Asia. Routledge.

- Lele, S. (1991). Sustainable development: A critical review. World Development, 19(6), 607–621. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/105953/mod_resource/content/9/texto_1.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(91)90197-P

- Le Roux, C. S. (2017). Language in education in Algeria: A historical vignette of a ‘most severe’ sociolinguistic problem. Language & History, 60(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/17597536.2017.1319103

- Liddicoat, A. (2016). Language planning in universities: Teaching, research and administration. Current Issues in Language Planning, 17(3–4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2016.1216351

- Liddicoat, A. J. (2013). Language-in-education policies: The discursive construction of intercultural relations. Multilingual Matters.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2013). Language Planning and Student Experiences: Intention, Rhetoric and Implementation. Multilingual Matters.

- Lo Bianco, J. (2015). Exploring language problems through Q-sorting. In F. M. Hult, & D. C. Johnson (Eds.), Research methods in language policy and planning: A practical guide (pp. 69–80). Wiley-Blackwell.

- MERIC-NET. (2019). The higher education system in Algeria: National report. http://www.meric-net.eu/files/fileusers/National_Report_template_MERIC-NET_Algeria_English.pdf

- Mustafawi, E., & Shaaban, K. (2018). Language policies in education in Qatar between 2003 and 2012: From local to global then back to local. Language Policy, 18(2), 209–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-018-9483-5

- Nordic Council. (2007). Deklaration om nordisk språkpolitik. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:norden:org:diva-607

- Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Longman/PearsonEducation.

- Norton, B. (2001). Non-participation, imagined communities, and the language classroom. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research (pp. 159–171). Pearson Education.

- Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

- Pflepsen, A. (2016, July 27). Planning for language use in education: Best practices and practical steps for improving learning. UNESCO. Retrieved October 27, 2022 from: https://world-education-blog.org/2016/07/27/planning-for-language-use-in-education-best-practices-and-practical-steps-for-improving-learning/

- Phillipson, R. (2018). Forward. In R. Barnard, & Z. Hasim (Eds.), English medium instruction programmes: Perspectives from south east Asian universities (pp. xiii–xv). Routledge.

- SAGE. (2018). Using Q methodology as a course feedback system. SAGE. https://methods.sagepub.com/base/download/DatasetStudentGuide/q-methodology-coursework

- Schmolck, P. (2014). PQMethod (Release 2.35) [Computer software]. http://schmolck.userweb.mwn.de/qmethod/downpqmac.htm

- Smit, U. (2018). Beyond monolingualism in higher education: A language policy account. In J. Jenkins, W. Baker, & M. Dewey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua franca (pp. 387–399). Routledge.

- Stephenson, W. (1953). The study of behavior: Q-technique and its methodology. University of Chicago Press.

- Stephenson, W. (1967). The play theory of mass communication. University of Chicago Press.

- Stephenson, W. (1986). Quantum theory of advertising. Missouri School of Journalism.

- Stibbe, A. (2015). Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology and the stories we live by. Routledge.

- Stibbe, A. (2019). Education for sustainability and the search for new stories to live by. In J. Armon, S. Scoffham, & C. Armon (Eds.), Prioritizing sustainability education: A comprehensive approach (pp. 233–243). Routledge.

- Sustainable Development Report. (2021). https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/rankings

- UNESCO. (2018). Financing higher education in Arab states. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/financing.pdf

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. SAGE.

- Webler, T., Danielson, S., & Tuler, S. (2009). Using Q method to reveal social perspectives in environmental research. Social and Environmental Research Institute. http://www.serius.org/pubs/Qprimer.pdf

- Wodak, R., de Cillia, R., Reisigl, M., & Liebhart, K. (1999). The discursive construction of national identity, (Angelika Hirscr, Trans.). Edinburgh University Press.

- World Bank. (2017). Toward a diversified knowledge-based economy: Education in the Gulf cooperation countries: Engagement note. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29271/122881-WP-EducationSectorEngagementNotefinal-PUBLIC.pdf?sequence = 1

- Zabala, A., Sandbrook, C., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). When and how to use Q methodology to understand perspectives in conservation research. Conservation Biology, 32(5), 1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13123