ABSTRACT

This study demonstrates that linguistic landscape analysis is a powerful tool for assessing the effectiveness of a university language policy, as it provides in situ evidence for discursive patterns shaping language use in public space. It uses the official language policy of a Norwegian institution of higher education (Høgskulen på Vestlandet, HVL) as a case study, contrasting its language guidelines with the linguistic make-up of the signage in the linguistic landscape on one of its campuses. The comparison shows that the linguistic landscape prioritizes the national representational level (use of Bokmål) in its bottom-up signage, while the language policy of the university mainly highlights regional and international aspects (connected to the parallel use of Nynorsk and English). At the same time, it is shown that the top-down signage issued by the university does not efficiently implement its language policy goals, as bilingual Nynorsk-English signs are rare, Nynorsk faces substantial competition from Bokmål, and English is both neglected and constructed as a less important variety.

Introduction

Higher educational institutions are a context in which language policy issues surface almost automatically. This is the case because they represent spaces in which not only the language varieties of the local geographical context play a role but also the use of languages of wider academic communication. Universities have become international workplaces, and there is a trend of them becoming increasingly internationalized as a result of a cross-cultural exchange of knowledge, researchers, and students, as well as international collaborations in higher education and research. Norway makes no difference in this respect (see Ljosland, Citation2011, Citation2015).

A high public visibility of languages that play a role in international communication can, on the one hand, be considered an index of the degree of internationalization of the institution at hand. On the other hand, such sociolinguistic realities can also be actively shaped in order to foster internationalization or to facilitate communication among international scholars, employees and students. This article presents a study that investigates these issues as they manifest themselves at a specific Norwegian institution of higher education: Høgskulen på Vestlandet, also known informally as HVL, and more recently as Western Norway University of Applied Sciences.

The following section outlines basic issues in Norwegian language policy, which serve as a theoretical backdrop for this study. After outlining linguistic landscape analysis as a methodology, I carry out a discourse analysis of HVL's official language policy document and a linguistic landscape analysis of HVL's Kronstad Campus in Bergen. The concluding section summarizes central findings and discusses them in relation to potential language policy adaptations and further implementation.

Language policy in Norway

The sociolinguistic situation in Norway is often described as unique and progressive (e.g. Jahr, Citation2018; Vikør, Citation2018; but see Trudgill, Citation2018). Linguistic diversity is in this policy not just protected through the promotion of minority languages on Norwegian territory (Sami, Norwegian sign language), but also through granting official status to two written standard varieties of Norwegian: Bokmål, the most commonly used written standard variety nationwide (historically closer to Danish), and Nynorsk, a less frequently used standard based on Western Norwegian dialects. Both standard varieties are taught at school. However, Nynorsk is regularly used by 600,000–640,000 Norwegians only (Sanden, Citation2020, p. 202), which amounts to 10–15% of the population (Berezkina, Citation2018, p. 65). Therefore, it represents a minority variety that is both regionally and politically marked (Linn, Citation2014, p. 43). Bokmål possesses the status of a default standard, which also predominates in the teaching and learning of Norwegian as a foreign language. Despite substantial state support for Nynorsk, its implementation in official or professional contexts often remains marginal (e.g. Sanden, Citation2020). The multilingual focus of Norway's language policy can, for example, be witnessed on television, with the national TV channel NRK presenting news in Sami, Nynorsk, Bokmål and Norwegian sign language at different times of the day.

Another idiosyncratic feature of the sociolinguistic profile of Norway is that regional dialects enjoy high prestige and vitality across usage contexts and social groups. This contrasts with many other European countries, where the use of regional dialects is on the decrease, as spoken official language use orients to the standard variety or at least avoids (strongly) regional speech features.

While historically, Norwegian language policy has focused on the co-existence of the two written standards, more recent language policy activism has concentrated more on the role of English, which is commonly perceived as a threat to Norwegian (see Graedler, Citation2014). Central issues in this respect are lexical gaps in the Norwegian technical vocabulary and the prevention of domain loss to English, as the latter is becoming increasingly prominent in areas such as research, higher education and business (Hultgren, Citation2015).

This situation has given rise to a strategy of parallel language use (‘parallelingualism’; Linn, Citation2010, p. 124), which is today a common language policy goal in the Nordic countries more generally (Gregersen, Citation2018; Hultgren, Citation2018). The aim is to use Norwegian and English side by side. In the university context, for example, this allows for the pursuing of two central goals at the same time: internationalization in higher education and research, and protection and cultivation of the national language (Linn, Citation2014; Ljosland, Citation2014). However, the use of the two languages is in general not conceived in an equal fashion, even though the term ‘parallel’ suggests this. Language policy documents rather formulate the goal with the slogan ‘Norwegian when you can, English when you have to’ (Linn, Citation2010, p. 124), which de facto means a privileging of Norwegian. Still, English plays a strong role in Norwegian society today and English proficiency levels among Norwegians are generally high, which has induced some researchers to claim that it borders second (rather than foreign) language status (e.g. Berezkina, Citation2018, p. 70; Rindal, Citation2015, p. 242).

Methodological considerations

The main data for this study consist of HVL's language policy document and the public signage on HVL's Kronstad campus in Bergen. Similar combinations of data types have recently been used to study linguistic diversity on campuses of universities that offer English-medium instruction, i.e. educational contexts in which English plays a central role (see Anderson, Citation2019; Jenkins et al., Citation2019; Mauranen & Mauko, Citation2019). It will be of interest to see how such an approach can be used to shed light on the language policy and linguistic landscape of an institution of higher education where English is in general not the medium of instruction.

This study utilizes a discursive approach to language policy (Barakos, Citation2016; Barakos & Unger, Citation2016; Johnson, Citation2016; Savski, Citation2021), meaning that both the language policy document and the linguistic landscape of HVL will be studied to uncover language-related discourses. Both data types will be analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively, to find evidence for aspects that surface repeatedly (intertextually) in the data and thus can be interpreted as traces of language-related discourses. This procedure incorporates the analysis of both language-related ideologies (the language policy document as a top-down structuring mechanism) and actual linguistic practices (the linguistic landscape). As pointed out by Hultgren et al. (Citation2014, p. 2), language policy ideologies are value-laden discursive formations that stipulate which linguistic practices should or should not occur in a public space. An analysis of linguistic practices, by contrast, documents how language is actually used, and thus often reveals clashes with the normative ideologies surfacing in official language policies.

Linguistic landscape analysis is still an underexplored methodology in research on language policies (see Barni & Bagna, Citation2015; Gorter, Citation2019; Lou, Citation2017 for outlines of this methodology). A recent handbook entitled Research Methods in Language Policy and Planning: A Practical Guide (Hult & Johnson, Citation2015), for example, does not contain a chapter on linguistic landscape analysis. However, today we see increasing efforts in linguistic landscape studies to incorporate analyses of language policies (Gorter, Citation2021; Shohamy, Citation2015) and to study linguistic landscapes in order to scrutinize whether official language policies are implemented in a particular space (e.g. Han & Wu, Citation2020; Hult, Citation2018; Kretzer & Kaschula, Citation2021; Savski, Citation2021; Shohamy, Citation2015). This is because linguistic landscape analysis represents an excellent tool for documenting the visibility, competition, and ethnolinguistic vitality of language varieties in a given place. Such an analysis is not just meant to describe sociolinguistic facts as they unfold in public space. Through a comparison of these facts with the official language policy, the analysis possesses the additional applied linguistic value of identifying on which aspects future language policy measures need to concentrate to change the status quo toward the set target.

A linguistic landscape analysis provides a systematic investigation of the signage in a specific public space. The signage includes all sorts of signs that are used to communicate in this space and may include, for example, billboards, traffic signs, road signs, posters, flyers, shop fronts, graffiti, and restaurant menues (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010; Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997; Shohamy, Citation2019). In their collectivity, these signs are taken to be evidence for what kind of a social space the place in question is. Language choices on public signage are the result of a negotiation of official language policies, language attitudes and people's communicative needs (Hult, Citation2018, p. 336). Oftentimes, public signage gives us access to insights on who frequently visits, lives or works in a certain space, which competing discourses and ideologies surface, or which social atmosphere predominates in it. Furthermore, – and this is what this study wants to take advantage of – public signage can give us information on how language policies shape (or fail to shape) a concrete locality.

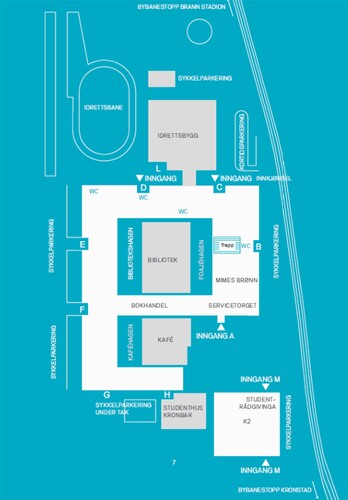

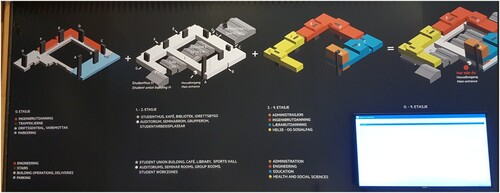

As is typical of a linguistic landscape framework, the public signage on campus was documented through photos, which were taken over a time period from January to April 2021. The photo data of the landscape inside and outside the buildings on campus were collected during times when the campus was close to empty (due to Covid lockdown or holidays), as the focus of analysis is on the signage rather than on the social actors normally populating this space. However, in order to include less permanent signage that is connected to the presence of higher amounts of people on campus, I also took a tour around campus to spot signs that had not been on display during the other times of data collection (for example, signs saying that the local coffee bar is open). Photos were taken on the ground and second floors of the main building (K1), including the hallways, classrooms, the restaurant area, and the library. The higher floor levels were not included, as they house mainly offices, which are not easily accessible to the general public. Another reason for excluding the higher levels is that HVL does not allow employees to put up notices, posters or other material in the office workspaces, which leads to a fairly impoverished linguistic landscape in these spaces that would not have merited analysis. I also documented all floors of the K2 building and the sports building (called Idrettsbygg on the map in ), as well as all outside areas of the campus. After an inspection of the photo material, doublets were discarded. This yielded a total amount of 393 signs to be analyzed. I included exclusively signs that had a verbal component in them, so the material contains verbal signs as well as multimodal (verbal and visual) signs.

All signs were then analyzed in terms of the following aspects: top-down vs. bottom-up signs, the language varieties displayed, and the language configuration on linguistically diverse signs (duplicating, complementary or overlapping information; visual dominance mechanisms). These classificatory procedures form the basis for the quantitative analysis of representational features. While the quantitative analysis reveals how frequently the individual varieties (and combinations of them) appear in the linguistic landscape, the qualitative analysis focuses more specifically on issues of language configurations in multilingual signs.

The traditional top-down/bottom-up distinction known from linguistic landscape research was retained for the classification of signs in this study, but extended by an additional category for signs that cannot be characterized as either top-down or bottom-up in a meaningful way. Signs that can with a high degree of certainty be traced back to the institution HVL as a sign issuer were classified as top-down. Such signs form a group in which the official language policy should be implemented. All other pieces of communication that have been produced by people working on campus (students, employees or businesses) were categorized as bottom-up signs. The third category comprises signs that occur on campus but have neither been issued nor produced by HVL, its students, employees and associated businesses. Classic examples are inscriptions on technical devices and items of consumption, that is, signage whose appearance has been determined by parties outside the university.

The collection of this textual material is supplemented by an ethnographic component, as is common in recent types of critical discourse analysis (see Krzyżanowski, Citation2011). I had started working at HVL in November 2020, a short time before I started taking the first photos. My professional work on campus provided me with insights on official university policies and campus life more generally speaking. Still, as a new employee, I felt that I inevitably adopted the perspective of an outsider who is not yet fully familiar with the context. This allowed me to act as a naïve observer who explores a space previously unknown to him. As a fairly new employee of foreign origin with substantial professional experiences at the international level, I approach HVL language policy clearly not from a neutral perspective. Still I would like to argue that my position in relation to the subject matter is legitimate, as it allows me (1) to place the ‘critical’ focus of my discourse analysis on aspects that Norwegian employees and students with limited international academic experience are not necessarily aware of, and (2) to foreground the perspective of a minoritized, but growing, group of HVL employees and students from other countries, who substantially contribute to the internationalization of HVL as a workplace.

In the autumn term 2021, HVL hosted 17,580 registered students, with HVL's student organization estimating the number of foreign students as up to 600 (3.4%; under different, non-pandemic circumstances, it would probably have been higher). These figures are likely to rise in the future. This will cause a situation in which a higher use of English on campus will be called for, for the sake of inclusiveness; and more use of English will in the long run also attract more international students. Estimations of the percentage of international students at Norwegian universities range around 10% (Hultgren et al., Citation2014, p. 1; Linn, Citation2014, p. 41).

Furthermore, at the moment of writing, HVL hosts 107 employees from all over the world that have specified a non-Norwegian origin (data from HVL's salary department). In total, HVL has 2147 employees, so the percentage of these foreign employees amounts to 5%. As not all employees of foreign origin have specified their nationality, the actual figure is higher (and likely to rise in the future). While some foreign employees (from Denmark and Sweden) can be assumed to have at least passive Norwegian comprehension skills, the majority have L1s that are unrelated to Norwegian and therefore will depend on the use of English on campus, at least during their initial years of employment.

Analysis of HVL’s language policy

HVL is a fairly new institution of higher education that was created through the merging of five former university colleges across Western Norway (in Bergen, Førde, Haugesund, Stord and Sogndal) in January 2017. It boasts itself to be ‘one of the largest educational institutions in the country’ and has declared receiving university status as its central aim, with the fusion constituting a strategic move to achieve this goal (planned for 2023). The university has a Nynorsk (Høgskulen på Vestlandet) as well as an English name (Western Norway University of Applied Sciences). Informally, the institution is often referred to by the acronym HVL, which can be read as more inclusive as far as Norwegian is concerned, because this abbreviation also matches the Bokmål version of the name (Høyskolen på Vestlandet).

Furthermore, HVL has developed a marketing campaign promoting its role in Norwegian higher education (HVL, Citation2018b). Central aspects of this campaign are outlined on the university's website (www.hvl.no). The passages cited in the following are taken from the English version of the university's ‘About us’ pages (HVL, Citation2019; bold print added):

(1)

Internationalisation

HVL shall attain an international position and work to achieve education and R&D activities of high international quality. We shall increase the expertise of the academic environments and educate good candidates by means of good mobility agreements for students and staff and internationalisation of all the educational cycles. HVL will strengthen education and research and develop a diverse and stimulating environment through international recruitment of students and staff.

(2)

HVL shall train and educate competent candidates. Research, development work and innovation shall be of high international quality. We will communicate and share relevant knowledge.

In other passages, internationalization is coupled with more specific geographic areas, thus indicating a dual focus on the international and regional levels (3), on the international and national levels (4), or a triple focus on the international, national and regional levels (5).

(3)

HVL has a clear professional-oriented profile. Through education, research and development we create new knowledge and expertise, anchored internationally and with solutions that work locally.

(4)

HVL must be a distinct national and international conveyor of new knowledge within our areas of expertise.

(5)

To ensure greater quality and relevance, research activities shall take place in a regional, national and international research community and involve students and partners.

HVL's official language policy is outlined on its website under the title Språkpolitiske Retningslinjer (‘Language Political Guidelines’; HVL, Citation2018a). The guidelines have been in effect since 26 April 2018 (HVL, Citation2018a). This is important to note because this means that from the passing of the guidelines to the final month of data collection for this study, HVL has had three years to work toward an implementation of its language policy, and this would include the design of top-down signage on campus.

As is typical of language policy documents in Norway, the guidelines are written in Nynorsk. In contrast to the general practice on HVL's webpages, there is no ‘English’ menu option in the right-hand top corner of the page. This suggests that the target group is people who study and work at HVL and understand the regional standard Nynorsk, while students and employees from abroad without a Norwegian-language background are excluded. This must be interpreted as a marked absence, as a substantial part of the guidelines deals with the use of English (next to Norwegian). In other words, the agency in terms of the implementation of this language policy is placed in the hands of Norwegian language users. This is clearly legitimate as far as the promotion of Nynorsk is concerned, as international students and employees are unlikely to play a role in this process. It is, however, less straightforward for the promotion of English as a parallel language, which could be centrally driven by international students and employees.

The document consists of five sections: 1. Overordna språkpolitikk (‘Overall language policy’), 2. Utdannig og undervisning (‘Education and teaching’), 3. Forsking og formidling (‘Research and dissemination’), 4. Administrative forhold (‘Administrative contexts’), and 5. Oppfølging og språklege kvalitetstiltak (‘Follow-up and linguistic quality measures’). For reasons of space, I will concentrate here on section 1, because it has the greatest implications for the linguistic landscape on campus. Passages from the other sections will only be discussed in brief.

The overall aim of HVL’s language policy is sketched out in the introduction to the guidelines:

(6)

Dei språkpolitiske retningslinjene for HVL er utforma med tanke på at høgskulen skal kunne vere eit språkleg føredøme for norske universitet og høgskular når det gjeld god og rett bruk av språket; særleg nynorsk, men òg bokmål og teiknspråk. Høgskulen ønskjer dessutan å finne ein god balanse mellom bruken av norsk og det viktigaste parallellspråket, engelsk, både når det gjeld utdanning, forsking og formidling.

‘The language political guidelines for HVL have been created bearing in mind that the college should be able to become a linguistic role model for Norwegian universities and colleges as far as good and correct language use is concerned; especially Nynorsk, but also Bokmål and sign language. The college furthermore wishes to find a good balance between the use of Norwegian and the most important parallel language, English, concerning education, research and dissemination.’

The aim outlined here is a highly ambitious one, namely HVL acting as a role model for Norwegian universities. This suggests the creation of a more progressive type of language policy, which is expected to be imitated by other Norwegian institutions of higher education in the future. However, this is a daring claim, given that HVL's regional orientation to Western Norway is quite specific. The role model function is here connected to the three national standard varieties, with Nynorsk being ranked before Bokmål and Norwegian sign language (særleg nynorsk, men òg bokmål og teiknspråk ‘especially Nynorsk, but also Bokmål and sign language’). Also note that the central goal is to ensure ‘good and correct language use,’ rather than incorporating issues revolving around communicative efficiency or identity values. The role model function is not extended to the use of English, which is said to be a parallel language of Norwegian. (It is interesting to note that English is constructed as ‘the most important parallel language’ in (6). This indicates that there are other such languages, but it remains unclear which ones.)

The section on the overall language policy contains four sub-sections: Generelt (‘General’), Nynorsk, Parallelspråk (‘Parallel languages’), and Klarspråk (‘Clear language’). I will concentrate on the first three sub-sections, as these contain information on the use of linguistic varieties, which is the focal point of the linguistic landscape analysis carried out further below.

In the introductory section, Norwegian and English are laid out as central target languages in which high proficiency is desired. More specifically HVL is said to aim to:

(7)

[…] sjå til at både tilsette og studentar kan kommunisere og uttrykkje seg på eit godt, klart og forståeleg norsk språk både munnleg og skriftleg. HVL ønskjer òg at tilsette og studentar skal meistre engelsk munnleg og skriftleg.

[…] make sure that both employees and students can communicate and express themselves using a good, clear and understandable Norwegian language both spoken and written. HVL also wishes that employees and students should master English in spoken and written form.

In the sub-section on Nynorsk, the guidelines refer to the fusion agreement (fusjonsavtalen) specifying that Nynorsk should be the main language variety for HVL as a merged university. This is justified through its smaller role as a written standard compared to Bokmål (which is implied to necessitate protective mechanisms), HVL's location in Western Norway, and an orientation to Western Norwegian culture and identity. In terms of implementation, the following measures are specified: central documents at the institute level should be in Nynorsk; in announcements and circulars, Bokmål and Nynorsk should be used at least 25% of the time (in accordance with the Norwegian Law about Language Use in Public Services [Lov om målbruk i offentleg teneste]); Nynorsk technical terms for research and education should be developed. At the same time, students and employees are said to have the right to choose whether they use Bokmål or Nynorsk. This indicates an awareness that actual language practices may clash to some extent with the official language policy.

The sub-section on parallel language use is most relevant for the use of English. It is not a coincidence that this is the passage in the document where internationalization is highlighted:

(8)

Høgare utdanning og forsking vert i aukande grad internasjonalisert. Det gjeld også ved Høgskulen på Vestlandet. Vestlandsregionen, som er høgskulens regionale omland, har eit internasjonalt og utoverretta nærings- og arbeidsliv, som treng solide kunnskapar både i norsk og engelsk.

Ut frå ein slik bakgrunn er det sjølvsagt at Høgskulen på Vestlandet må styrkje sin kompetanse i parallellspråk, særleg i engelsk. Av same grunn må parallellspråksbruk vere eit berande element i språkstrategien ved HVL.

Higher education and research become increasingly internationalized. This is also the case at HVL. The Western Norway region, which is the regional environment of the college, has an international and outreaching economy and work life that necessitates solid knowledge both of Norwegian and English.

Against such a background, it is a matter of course that HVL has to strengthen its competence in parallel languages, especially in English. For the same reason, parallel language use has to become a sustainable element in the language strategy of HVL.

In the sub-section on 'Clear language’ (Klarspråk), it is noteworthy that a connection with democracy is drawn that is absent from the previous sections on variety choice: Eit klart og godt språk styrkjer demokratiet (‘Clear and good language strengthens democracy’). This seems counter-intuitive, as higher inclusivity levels can first and foremost be achieved through the use of varieties students and employees are familiar with, while clarity and ‘good’ language use rather point to esthetic quality judgements in relation to language. The clearest and most pleasing language use has little democratic value if it is in a language that is not understood by the target audience.

The following sections on education and teaching, research and dissemination, and administrative contexts also contain references to language choice. With respect to the language of instruction, the following is outlined:

(9)

Norsk, nynorsk og bokmål, skal vere det sentrale undervisningsspråket ved HVL. Det gjeld på alle nivå. Der det høver, kan dansk, svensk eller teiknspråk nyttast i undervisninga.

Norwegian, Nynorsk and Bokmål, should be the central language of instruction at HVL. This is valid for all levels. Where it is suitable, Danish, Swedish or sign language can be used in teaching.

The section on research and dissemination shows the clearest traces of a domain loss discourse. On the one hand, the dominant role of English as a publication language is acknowledged. On the other hand, it is pointed out that Norwegian needs to be protected as an academic language. It is suggested that this can be done by adding Norwegian abstracts to English publications, developing Norwegian technical terminology, and translating research literature into Norwegian.

The section on administrative contexts highlights that the rising number of international students and employees exerts pressure on technical and administrative staff to develop English language skills. The most direct reference to language use in the linguistic landscape of HVL can be found in the following quote:

(10)

Fakultet, institutt, læringssenter o.l. ved HVL skal også namnsetjast på engelsk. Dei viktigaste skilta skal ha tekst både på nynorsk og engelsk.

Faculties, institutes, learning centers and similar entities at HVL should also be labeled in English. The most important signs should have text both in Nynorsk and English.

presents how often which specific language varieties are mentioned in the language policy document. When looking at the frequencies of the individual variety references, one finds that Norwegian (norsk) is mentioned most often (42 times), followed by English (engelsk, 33 times). This shows that a central issue in the document is to regulate under which circumstances Norwegian and English can or should be used. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that Nynorsk is mentioned 13 times on its own, while Bokmål only receives one individual mention. This is an expression of a language policy that intentionally prioritizes Nynorsk as an otherwise minoritized written standard. Norwegian sign language is mentioned nine times. Other varieties are not mentioned individually. There is a marked absence of Sami, which is a minority language with co-official status in certain parts of Norway.

Table 1. References to language varieties in HVL's language policy document.

The coordinated references to language varieties add another perspective to this representation. It has been shown in studies on binomials that the first component in coordinative structures is generally perceived as more important or powerful (see Motschenbacher, Citation2013). Based on this assumption, the coordinated references indicate a ranking that views Norwegian varieties as more important than English. We find eight instances of Norwegian (Norwegian, Nynorsk, Bokmål, Norwegian sign language) being mentioned before English, and only one instance of English being mentioned before Norwegian. The latter occurs in the sub-section on PhD education, i.e. a context where English de facto plays a higher role. The remaining coordinated structures additionally indicate a ranking within the group of Norwegian varieties, with Nynorsk being named before Bokmål, and Nynorsk and Bokmål before Norwegian sign language.

The ranking of varieties as evident from coordinated references in the HVL language policy document thus unfolds as follows:

Norwegian [ > Nynorsk > Bokmål > Norwegian sign language] > English

Overall, the language policy document creates an impression of English as a necessary evil. This representation is far away from a more productive image of English as being embraced by students and employees as a valuable resource for expression and identification. We now turn to the analysis of the linguistic landscape on HVL's Kronstad Campus.

Linguistic landscape analysis of HVL’s Kronstad Campus

Quantification of language varieties in the linguistic landscape

presents the absolute and relative frequencies of the variety choices in relation to top-down, bottom-up and other signage on HVL's Kronstad Campus. When analyzing this data, it is of interest to relate the findings for the top-down signage to HVL's official language policy. Another pertinent aspect is a comparison of the top-down and the bottom-up signage on campus, in order to see whether there are clashes between them.

Table 2. Usage frequencies of linguistic varieties on HVL campus.

When comparing the top-down to the bottom-up signage, it is remarkable that both types show similar percentages of monolingual (86.1% and 85.0%) and multilingual signs (13.9% and 15.0%). Viewed from this perspective, the two types of signage seem to correspond. However, a closer look at the individual language categories reveals quantitative differences within the monolingual and multilingual groups.

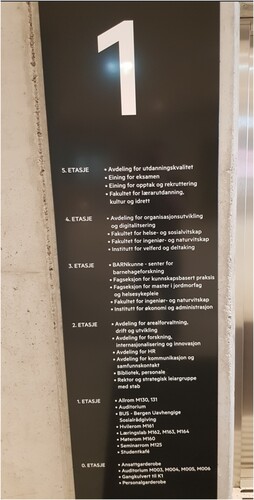

Within the monolingual group, the top-down signage is dominated by Nynorsk (39.3%), while the bottom-up signage is predominantly in Bokmål (55.8%). and illustrate top-down signs in Nynorsk. shows an overview of the floors in one of the university buildings. Various lexical items on the sign are Nynorsk-specific (e.g. eining ‘unit,’ lærar ‘teacher,’ forsking ‘research,’ vitskap ‘science,’ leiargruppe ‘leader group’).

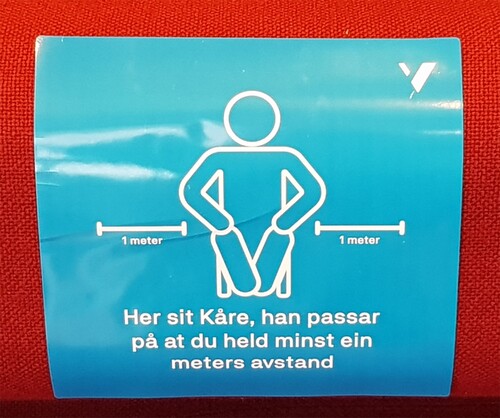

shows a Covid-related sign – a sticker that is meant to help people to keep a distance when sitting down on the sofas in the university building. The sign exhibits a personification strategy, both visually in the depiction of a (prototypically) male sitting person and verbally through an explicit naming of this person with a male Norwegian personal name (Kåre). In the text, it is the verb forms (sit ‘sits,’ passar ‘takes care,’ held ‘hold’) and the grammatically feminine numeral ein ‘one’ that are Nynorsk-specific. (The text translates as ‘Here sits Kåre, he takes care that you keep at least one meter distance’; the symbol in the top right corner is HVL's logo).

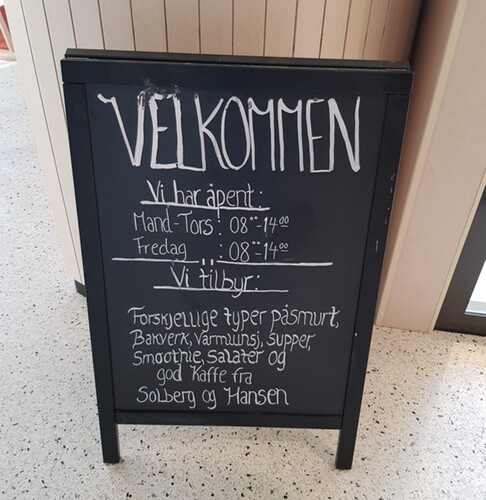

The use of Nynorsk on top-down signs contrasts with the overwhelming use of Bokmål on bottom-up signs. The latter tend to provide a better reflection of the actual or preferred linguistic practices of the social actors working in a certain space. This is in the following examples further underlined by their hand-written nature. shows a coffee bar menu written on a blackboard with chalk. The two lexical items åpent ‘open’ and kaffe ‘coffee’ point to Bokmål (the Nynorsk forms would be opent and kaffi).

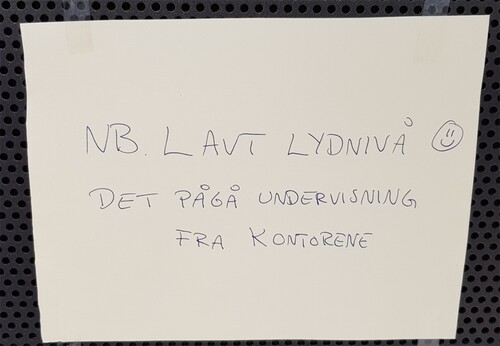

In , we see a handwritten note attached to an office door that asks people in the hallway to remain silent (the text translates as ‘NB. Low sound level  Teaching going on in the offices’). Lexical items that are Bokmål-specific in this sign are pågår ‘goes on’ (here represented as pågå, with the inflectional ending missing, which probably points to a non-native language user), the preposition fra, and the plural inflection -ene in kontorene ‘the offices.’

Teaching going on in the offices’). Lexical items that are Bokmål-specific in this sign are pågår ‘goes on’ (here represented as pågå, with the inflectional ending missing, which probably points to a non-native language user), the preposition fra, and the plural inflection -ene in kontorene ‘the offices.’

While Bokmål is still the second most frequent choice in the top-down signage with a substantial share of 18.9%, Nynorsk is clearly less common in the bottom-up signs (5.3%). There is also a group of signs (typically with short verbal text parts), in which it cannot be decided whether the Norwegian used is Nynorsk or Bokmål (see category ‘Nynorsk/Bokmål’ in ). These are similarly common in top-down and bottom-up signs (10.7% and 14.1%). However, there is a greater difference in the number of signs that display both Nynorsk and Bokmål material. These are clearly more common in top-down signs (14.8%) than in bottom-up signs (3.9%). This difference merits a closer look in the qualitative analysis.

Concerning the question in how far the top-down signage implements HVL's language policy, it needs to be pointed out that there is a clash between representational goals and actual communicative practices. A language policy with a dual focus on the promotion of Nynorsk as a regional language and English as a language of wider international communication would ideally be implemented in the shape of bilingual Nynorsk-English signs. However, these only make up 6.6% of all top-down signs documented. While the promotion of Nynorsk is clearly visible in the top-down signage (39.3% vs. only 5.3% in bottom-up signs), it does not seem to be in full effect, as Bokmål still has a substantial share of 18.9% in the top-down signage. The greatest clash is constituted by a neglect of English in HVL's top-down signage. Only 2.5% of the top-down signs are in English exclusively. On the other hand, in all multilingual configurations on the top-down signs (13.9% in total), English plays a role next to Norwegian varieties.

With the signage that is neither top-down nor bottom-up, the greatest idiosyncrasy is that Nynorsk does not play a role at all, while the share of both English-only (23.1%) and multilingual signs (30.8%) is substantially higher than in the other two conditions.

Qualitative analysis of the linguistically diverse signage

A qualitative analysis of the linguistically diverse signs can shed further light on which varieties are contextually treated as more important than others. This may have something to do with how much and which information is conveyed in which variety and how the varieties are visually represented on the signs. The analysis will focus on signs that show a co-presence of the two Norwegian standard varieties Bokmål and Nynorsk and on signs that exhibit material from two or more languages.

In the previous section, we saw that signs combining Nynorsk and Bokmål forms are more common in the top-down category than in the bottom-up category. A closer qualitative analysis of these signs is enlightening with respect to which of the two varieties is treated as more important. Many of the top-down signs are overwhelmingly in Bokmål, with the verbal part of the university logo being the only text part that is in Nynorsk. We see this, for example, in , showing a top-down sign completely in Bokmål (plural forms studenter ‘students’ and arrangementer ‘events,’ veiledning ‘guidance’). Only the Nynorsk HVL logo (with the name Høgskulen på Vestlandet) at the bottom left side of the sign clashes with this.

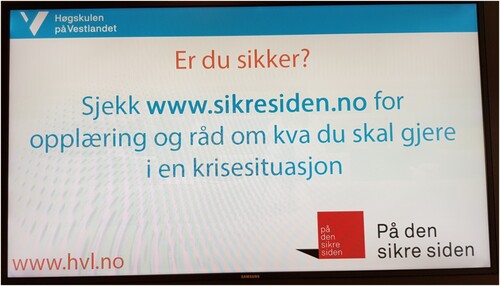

While in such examples, it can clearly be delimited which text parts are in which Norwegian variety, this is not such a straightforward task in other signs. Sometimes, one finds texts on signs that contain both traces of Nynorsk and Bokmål. On top-down signs, such cases of variety mixing are likely an outcome of people who normally use Bokmål trying to use Nynorsk on behalf of HVL, which may lead to a Nynorsk text with an admixture of Bokmål features. In , for example, we see two lexical items besides the HVL logo that qualify as Nynorsk (kva ‘what,’ gjere ‘do’) as well as two forms that are Bokmål-specific (the indefinite article en, the definite form siden ‘the side’).

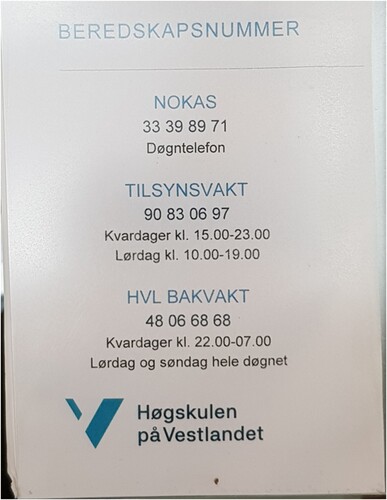

Similarly, in Nynorsk lexical items (kvardag ‘weekday,’ HVL logo) are juxtaposed with Bokmål material (Lørdag ‘Saturday,’ hele ‘whole’). The form kvardager is especially interesting, as it constitutes a Nynorsk lexical item (kvardag, vs. hverdag in Bokmål) with a Bokmål plural inflection (-er, vs. -ar in Nynorsk).

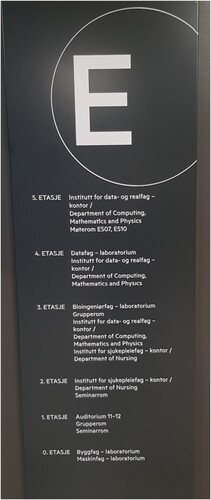

In order to investigate the relationship between English and Norwegian in the linguistic landscape more specifically, it is pertinent to analyze signs on which the two languages co-occur ( and ). On the top-down side, a combination of Nynorsk and English would correspond to the official language policy. Still, this leaves open whether the two languages are in fact treated equally on actual signs. Interestingly, none of the top-down signs that combine Nynorsk and English shows a fully parallel use of the two varieties. In all cases, more information is presented in Nynorsk than in English, which indicates that Nynorsk, and the people who are addressed through Nynorsk, possess a privileged status vis-à-vis English and people unfamiliar with Nynorsk. presents a case from the data in which fully parallel language use involving Nynorsk and English is almost achieved. The sign presents a map of the floors of the main university building. In all passages where information is provided in both languages, the Nynorsk text is presented on top of the English text, which is another index of the predominance of Nynorsk. There are two aspects that are provided in Nynorsk exclusively: the floor names (0. etasje, 1.-2. etasje etc.) and the locator phrase Her står du (‘You are here’).

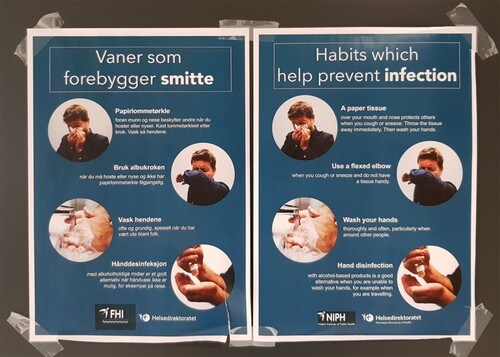

Fully parallel use of Norwegian and English can be found in , which shows a presentation of Covid measures in Bokmål and English. This can be read as a positive example of parallel language use, as all text parts (even the logos at the bottom) are presented in the two languages. The only aspect that would indicate a privileging of Norwegian is the fact that the Bokmål version of the poster is presented on the right side, which may be taken to suggest that this is the original version, from which the English version on the left side has been created through translation.

In some passages, the translation is not literal. For example, the English text asks people to throw the tissue away immediately, while the Norwegian text says kast lommetørkleet etter bruk ‘throw the tissue away after use.’ The English version systematically uses possessive pronouns in connection with body-part nouns where the Norwegian version has none (e.g. your mouth, twice your hands vs. munn ‘mouth,’ hendene ‘the hands’). Also, the English text draws more on hedging devices (help prevent vs. forebygger ‘prevent’) and personal constructions (when you are unable to wash your hands vs. når handvask ikke er mulig ‘when handwashing is not possible’; when you are travelling vs. på reise ‘on a trip’).

represents a typical example of Nynorsk-English co-use on top-down signage in terms of the amount of information conveyed in the two varieties. Similarly as the sign in , this is a floor overview. All information is presented in Nynorsk, but only some information is co-presented in English. The room information for floors 0 and 1 is provided in Nynorsk exclusively. For floors 2–5, only the department names are presented in both varieties, while other pieces of information are in Nynorsk and stay untranslated (e.g. kontor ‘offices,’ seminarrom ‘classrooms,’ laboratorium ‘laboratory,’ grupperom ‘group rooms,’ bioingenjørfag ‘bioenigineering,’ møterom ‘meeting rooms’). Where both languages are used, Nynorsk is invariably depicted on top of English, indicating a hierarchy.

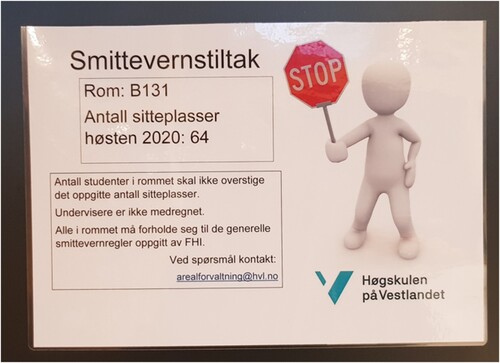

In some cases, signs exhibit just a tokenistic use of English and are otherwise dominated by Norwegian text. This is illustrated in , which shows a Covid sign outlining information on the maximum number of people allowed in a classroom. The main text on the left side of the sign is in Bokmål. On the right side, we find the Nynorsk HVL logo at the bottom, and a stylization of a faceless human figure holding up a stop sign. The form STOP can be considered English, as in Norwegian the word would be spelled differently (stopp).

Other languages than Norwegian and English appear mainly in the bottom-up and other signs. Multilingualism beyond the use of English and Norwegian is almost non-existent among the top-down signs. Signs in the ‘other’ category are often texts displayed on products or devices in which certain technical specificities are outlined in many different (mainly European) languages. Languages found on bottom-up signs include Italian, French, Latin, Swedish, Arabic, Spanish, Icelandic, German and Polish. Examples of this can be found in , depicting a Polish football sticker on the HVL parking lot, and , which shows a coffee bar menu. The latter is framed by headings (e.g. kaffemeny ‘coffee menu’, dagens filterkaffe ‘filter coffee of the day’, spise sammen ‘eat together’) and marginal texts (e.g. inneholder melk ‘contains milk’) in Bokmål, which is thus the dominant language in the sign. But certain product names listed on the menu are in Italian (e.g. Latte, Macchiato, Cappuccino, Mocca, Americano, Espresso, Cortado, Prosecco), while others are in English (Bounty, After Eight, Dirty Chai, Sweet Chilli).

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that linguistic landscape analysis is an effective tool for research on language policies and their implementation (see overview in ). The insights of this study bear relevance beyond the institution investigated. They are of interest to university contexts across the globe in which language policies do not just have to deal with the competition between a local variety and English as an international lingua franca but with an additional competition between several local varieties.

Table 3. Language varieties at HVL: Language policy vs. linguistic landscape.

The analysis of the linguistic landscape of a university campus provides analysts with insights that cannot be gained from an analysis of language policy documents alone. Most importantly, such an in situ analysis captures the juxtaposition of official and grassroots linguistic practices and thus gives researchers access to the competition of communication-related discourses that tends to unfold on campuses. An analysis of the top-down signage helps assess whether an official language policy has been sufficiently implemented and whether adjustments are necesssary, while the bottom-up signage fosters a better understanding of the unregulated practices of the people who work and study at a university. As official language policies generally have the goal to counter developments at the grassroots level that are deemed problematic, one is likely to find contrasts between top-down and bottom-up communicative practices. However, a realistic language policy will normally seek to incorporate the communicative status quo at the grassroots level, which forms a backdrop for the implementation of an official language policy.

HVL's official language policy document exhibits a dual focus on the promotion of Nynorsk as a regionally associated written standard and on the use of English as a parallel language that plays a central role for the internationalization of higher education and research. This dual focus is an outcome of two major ideologies shaping Norwegian language policies: an ‘internationalist’ discourse, which favors the use of English, and a ‘culturalist’ discourse, whose purpose is the protection of the national and, in the case of HVL, regional variety (Hultgren et al., Citation2014, p. 2).

A combination of these two aspects seems a reasonable strategy, given that HVL places emphasis on its regional as well as international orientation. Against the backdrop that parallel language use in Norwegian higher education usually involves Bokmål and English, HVL's aim to promote Nynorsk must be evaluated as a fairly progressive move. Since Nynorsk plays only a minor role in the learning of Norwegian as a foreign language, the co-reliance on English as a language of wider communication is in this context even more essential, as it helps including international students and employees whose familiarity with Nynorsk is (at least initially) likely to be low.

The qualitative analysis of the signs on HVL's Kronstad Campus reveals that the status of Nynorsk is less central in the top-down signage than suggested by the quantitative analysis. Signs often just show minimal usage of Nynorsk that is limited to the HVL logo and are otherwise in Bokmål. Moreover, one sometimes finds Nynorsk texts with an admixture of Bokmål-specific features.

In the multilingual signage, Norwegian is generally treated as privileged vis-à-vis English. Virtually all Norwegian-English bilingual signs present more information in Norwegian than in English, and Norwegian is in general used before English (either on top or to the right of English text passages). In addition, some signage supports the notion of ‘translanguaging’ (Gorter, Citation2021, p. 15), as it can be difficult to separate various ‘languages’ or ‘varieties’ as discrete entities in the verbal material (see, for example, the Nynorsk-Bokmål mixing illustrated in and , and the multilingual languaging illustrated in ).

Problematic aspects arise when we compare HVL's official language policy with the use of linguistic varieties on campus. The top-down signage issued by HVL shows a strong tendency to be in Nynorsk and thus largely conforms to the official language policy. The major point in which an insufficient implementation can be verified is the parallel use of English, which is hardly ever put into practice and, if so, only fragmentarily. Besides a further increase in Nynorsk top-down signage, the most important recommendation would therefore be to systematically implement parallel English use, to render the campus environment more inclusive. This would mean an increase of bilingual (Nynorsk-English) signage. Arguing in favor of parallellingualism has traditionally been common in contexts where Norwegian is in danger of losing usage domains to English. In the case of HVL, by contrast, it could be argued that orienting to parallellingualism is a strategy to support a stronger co-implementation of English, which currently is clearly under-represented in its linguistic landscape.

Arguably, an institution of higher education that prioritizes a regionally restricted variety as part of its language policy runs counter to the aim of internationalization that universities generally pursue today. This means that such a move needs to be coupled with measures that target international students and employees and thus address the communicative disadvantage that this group faces in the light of a promotion of Nynorsk, which represents a less foreigner-friendly option than Bokmål with its predominance in the learning of Norwegian as a foreign language. To redress this loss of inclusiveness, and to increase inclusiveness for people who have little or no command of Norwegian, the simultaneous promotion of English as the international lingua franca on campus is a viable (if not the only) option. Previous research on language choices on university campuses (see contributions in Jenkins & Mauranen, Citation2019) amply documents the link between internationalization, international competitiveness and the use of English in higher education and research. For HVL, turning into a fully-fledged university should therefore go hand in hand with an internationalization of its communicative practices.

Another aspect that is noteworthy is the fact that the bottom-up signage on campus is dominated by the use of Bokmål. This suggests that, at the grassroots level, the promotion of Nynorsk as the only written standard in HVL's public communication may be viewed critically, as it represents a forced choice that does not conform to the actual linguistic practices of the people who work and study in this context. An artificial curbing of Bokmål in HVL's official communication furthermore has the effect of prioritizing a regional over a national orientation, which may not be deemed adequate for an institution of higher education.

A socially realistic language policy for an educational institution cannot be implemented in an exclusively top-down fashion. Its success is likely to increase when the actual linguistic practices of the people working and studying at the institution are taken into account (Ljosland, Citation2015). An analysis of the linguistic landscape on campus constitutes one way of making its ‘lived’ language policy accessible. As Linn (Citation2010) has shown, Norway has a strong tradition of listening to the ‘voice from below’ (i.e. the voice of the language users) in language policy matters. Clashes between top-down and bottom-up language policies of a university campus should therefore lead to adaptations in its official language policy. A central goal in such language policy reforms will normally be to achieve higher levels of inclusivity. However, the current campus development (campus utvikling) project initiated by HVL (running November 2021 to April 2022) does not refer to language use on campus in any way (see also HVL, Citation2020).

A final point to note is that languages other than Norwegian and English do not play a significant role on campus. This is, for example, true for Sami, which is absent from the linguistic landscape of HVL, even though it has co-official status in some parts of Norway. Viewed from the point of view of the growing ethnic heterogeneity in Norwegian society caused by immigration, the linguistic landscape of HVL creates a relatively impoverished picture of linguistic diversity, which runs counter to an encouraging and valuing of cultural diversity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Heiko Motschenbacher

Heiko Motschenbacher is a full professor of English as a second/foreign language at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen. He is the founder and co-editor of the Journal of Language and Sexuality. His research interests include language, gender and sexuality, critical discourse analysis, corpus linguistics, English as a lingua franca, language, nationalism and Europeanisation, and linguistic inclusion in ELT. Among his most recent publications are the monographs Language, Normativity and Europeanisation (2016; Palgrave Macmillan) and Linguistic Dimensions of Sexual Normativity (2022, Routledge) as well as guest-edited special journal issues on Corpus Linguistics in Language and Sexuality Studies (2018), Linguistic Dimensions of Inclusion in Educational and Multilingual Contexts (2019) and Diversity and Representation in the ELT Classroom (2022).

References

- Anderson, L. (2019). Internationalisation and linguistic diversity in a mid-sized Italian university. In J. Jenkins, & A. Mauranen (Eds.), Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus: Insider accounts of the use of English and other languages in universities within Asia, Australasia, and Europe (pp. 50–73). Routledge.

- Barakos, E. (2016). Language policy and critical discourse analysis: Toward a combined approach. In E. Barakos, & J. W. Unger (Eds.), Discursive approaches to language policy (pp. 23–49). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barakos, E., & Unger, J. W. (2016). Introduction: Why are discursive approaches to language policy necessary? In E. Barakos, & J. W. Unger (Eds.), Discursive approaches to language policy (pp. 1–9). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barni, M., & Bagna, C. (2015). The critical turn in LL: New methodologies and new items in LL. Linguistic Landscape, 1(1/2), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.1-2.01bar

- Berezkina, M. (2018). ‘Language is a costly and complicating factor’: A diachronic study of language policy in the virtual public sector. Language Policy, 17(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-016-9422-2

- Gorter, D. (2019). Methods and techniques for linguistic landscape research: About definitions, core issues and technological innovations. In M. Pütz, & N. Mundt (Eds.), Expanding the linguistic landscape: Linguistic diversity, multimodality and the use of space as a semiotic resource (pp. 38–57). Multilingual Matters.

- Gorter, D. (2021). Multilingual inequality in public spaces: Towards an inclusive model of linguistic landscapes. In R. Blackwood, & D. A. Dunlevy (Eds.), Multilingualism in public spaces: Empowering and transforming communities (pp. 13–30). Bloomsbury.

- Graedler, A. (2014). Attitudes towards English in Norway: A corpus-based study of attitudinal expressions in newspaper discourse. Multilingua, 33(3-4), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0014

- Gregersen, F. (2018). More parallel, please! Best practice of parallel language use at Nordic universities: 11 recommendations. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Han, Y., & Wu, X. (2020). Language policy, linguistic landscape and residents’ perception in Guangzhou, China: Dissents and conflicts. Current Issues in Language Planning, 21(3), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2019.1582943

- House, J. (2003). English as a lingua franca: A threat to multilingualism? Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00242.x

- Hult, F. M. (2018). Language policy and planning and linguistic landscapes. In J. W. Tollefson, & M. Pérez-Milans (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language policy and planning (pp. 333–352). Oxford University Press.

- Hult, F. M., & Johnson, D. C. (2015). Research methods in language policy and planning: A practical guide. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hultgren, A. K. (2015). English as an international language of science and its effect on Nordic terminology: The view of scientists. In A. Linn, N. Bermel, & G. Ferguson (Eds.), Attitudes towards English in Europe: English in Europe, volume 1 (pp. 139–164). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Hultgren, A. K. (2018). The Englishization of Nordic universities: What do scientists think? European Journal of Language Policy, 10(1), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2018.4

- Hultgren, A. K., Gregersen, F., & Thøgersen, J. (2014). English in Nordic universities: Ideologies and practices. In A. K. Hultgren, F. Gregersen, & J. Thøgersen (Eds.), English in Nordic universities: Ideologies and practices (pp. 1–26). John Benjamins.

- HVL. (2018a). Språkpolitiske retningslinjer for Høgskulen på Vestlandet (“Language political guidelines for HVL”). Retrieved November 9, 2021, from https://hvl.no/om/sentrale-dokument/reglar/sprakpolitiske-retningslinjer/.

- HVL. (2018b). Interaction – sustainability – innovation: Strategy 2019-2023. (Brochure)

- HVL. (2019). Strategy HVL 2019-2023. Retrieved April 18, 2021, from https://www.hvl.no/en/about/strategy/.

- HVL. (2020). Stort campusutviklingsprosjekt skal gjere HVL til ein meir attraktiv studiestad (“Large campus development project should make HVL a more attractive study location”). Retrieved November 8, 2021, from https://www.hvl.no/aktuelt/stort-campusutviklingsprosjekt-skal-gjere-hvl-til-ein-meir-attraktiv-studiestad/.

- Jahr, E. H. (2018). Two centuries of Norwegian language planning and policy: Why and how it all started, and how it is divided into three different periods. In E. H. Jahr (Ed.), Perspectives on two centuries of Norwegian language planning and policy: Theoretical implications and lessons learnt (pp. 9–14). Kungliga Gustav Adolfs Akademien för Svensk Folkkultur.

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2010). Introducing semiotic landscapes. In A. Jaworski, & C. Thurlow (Eds.), Semiotic landscapes: Language, image, space (pp. 1–40). Continuum.

- Jenkins, J., Baker, W., Doubleday, J., & Wang, Y. (2019). How much linguistic diversity on a UK university campus? In J. Jenkins, & A. Mauranen (Eds.), Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus: Insider accounts of the use of English and other languages in universities within Asia, Australasia, and Europe (pp. 226–260). Routledge.

- Jenkins, J., & Mauranen, A. (eds.). (2019). Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus: Insider accounts of the use of English and other languages in universities within Asia, Australasia, and Europe. Routledge.

- Johnson, D. C. (2016). Theoretical foundations for discursive approaches to language policy. In E. Barakos, & J. W. Unger (Eds.), Discursive approaches to language policy (pp. 11–21). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kretzer, M. M., & Kaschula, R. H. (2021). Language policy and linguistic landscapes at schools in South Africa. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(1), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1666849

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2011). Ethnography and critical discourse analysis: Towards a problem-oriented research dialogue. Critical Discourse Studies, 8(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2011.601630

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002

- Linn, A. R. (2010). Voices from above – voices from below: Who is talking and who is listening in Norwegian language politics? Current Issues in Language Planning, 11(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2010.505070

- Linn, A. R. (2014). Parallel languages in the history of language ideology in Norway and the lesson for Nordic higher education. In A. K. Hultgren, F. Gregersen, & J. Thøgersen (Eds.), English in Nordic universities: Ideologies and practices (pp. 27–52). John Benjamins.

- Ljosland, R. (2011). English as an academic lingua franca: Language policies and multilingual practices in a Norwegian university. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(4), 991–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.007

- Ljosland, R. (2014). Language planning in practice in the Norwegian higher education sector. In A. K. Hultgren, F. Gregersen, & J. Thøgersen (Eds.), English in Nordic universities: Ideologies and practices (pp. 53–82). John Benjamins.

- Ljosland, R. (2015). Policymaking as a multi-layered activity: A case study from the higher education sector in Norway. Higher Education, 70(4), 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9832-z

- Lou, J. J. (2017). Linguistic landscape and ethnographic fieldwork. In C. Mallinson, B. Childs, & G. van Herk (Eds.), Data collection in sociolinguistics: Methods and applications (2nd edition) (pp. 94–98). Taylor & Francis.

- Mauranen, A., & Mauko, I. (2019). ELF among multilingual practices in a trilingual university. In J. Jenkins, & A. Mauranen (Eds.), Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus: Insider accounts of the use of English and other languages in universities within Asia, Australasia, and Europe (pp. 23–49). Routledge.

- Motschenbacher, H. (2013). Gentlemen before ladies? A corpus-based study of conjunct order in personal binomials. Journal of English Linguistics, 41(3), 212–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424213489993

- Rindal, U. (2015). Who owns English in Norway? L2 attitudes and choices among learners. In A. Linn, N. Bermel, & G. Ferguson (Eds.), Attitudes towards English in Europe: English in Europe, volume 1 (pp. 241–269). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Sanden, G. R. (2020). The second-class Norwegian: Marginalisation of Nynorsk in Norwegian business. Current Issues in Language Planning, 21(2), 202–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2019.1697556

- Savski, K. (2021). Language policy and linguistic landscape: Identity and struggle in two southern Thai spaces. Linguistic Landscape, 7(2), 128–150. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20008.sav

- Shohamy, E. (2015). LL research as expanding language and language policy. Linguistic Landscape, 1(1-2), 152–171. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.1.1-2.09sho

- Shohamy, E. (2019). Linguistic landscape after a decade: An overview of themes, debates and future directions. In M. Pütz, & N. Mundt (Eds.), Expanding the linguistic landscape: Linguistic diversity, multimodality and the use of space as a semiotic resource (pp. 25–37). Multilingual Matters.

- Trudgill, P. (2018). “Norwegian as a normal language” and other studies in Scandinavian Linguistics. Novus Press.

- Vikør, L. S. (2018). The Norwegian language situation: An overview. In E. H. Jahr (Ed.), Perspectives on two centuries of Norwegian language planning and policy: Theoretical implications and lessons learnt (pp. 15–28). Kungliga Gustav Adolfs Akademien för Svensk Folkkultur.