ABSTRACT

There is a growing number of ethnically and culturally diverse students in Dutch junior vocational high schools. This article examines teachers’ multicultural attitudes, their perceptions of cultural diversity related to school policy and school climate, and the chance of general and diversity-related burnout. The present research also characterises teachers in terms of their multicultural attitudes and perceptions of school policy and climate through cluster analysis. Results are based on questionnaire data of 120 teachers, working at five locations of a multicultural junior vocational high school in a highly urbanised part of the Netherlands. Correlational, regression, and variance analyses indicated that the highest levels of general and diversity-related burnout were found among teachers categorised as assimilationist in attitude and who perceived their school as pluralistic. Teachers could be divided into three types of profiles: (1) relative assimilative attitude, (2) no pronounced assimilative attitude, and (3) moderate assimilative attitude. Teachers with the second profile showed the highest chance for burnout.

Introduction

As the Western world becomes more culturally and ethnically diverse, so does its classrooms. More than ever, teachers and students encounter ethnic and cultural diversity in their classrooms. This trend is strongly linked to immigration, which represents steadily growing globalisation and increasing mobility of people, also within the European Union (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2004; Castles and Miller Citation2003; Entzinger and Van der Meer Citation2004; Hofstede Citation1991; Koopmans, Michalowski, and Waibel Citation2012; Scheffer Citation2014). In 2015, approximately four million of the 17 million residing in the Netherlands were either first or second-generation immigrants (CBS Citation2015). Approximately 2.7 of these four million had their roots in non-western countries, mostly Morocco, Turkey, Surinam, and the Dutch Antilles, Eastern Europe (former Balkan States), the Middle East, and African countries. The four largest cities are home to 45% of the nation’s immigrants (CBS Citation2015). Consequently, multicultural classrooms have become the ‘standard’ classroom. Multicultural classrooms are characterised by diversity in ethnicity, religion, mother tongue, and cultural traditions (Banks and McGee Banks Citation2004; Ben-Peretz, Eilam, and Yankevelevitch, Citation2006; Vedder Citation2006).

Teaching is a challenging and stressful job (Vedder, Horenczyk, and Liebkind Citation2007). Teachers face great demands on their energy and personal skills, sometimes with the risk of burnout. Burnout is described as a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity (Maslach and Jackson Citation1986). Travers and Cooper found in their research in the U.K. (Citation1993) that teachers suffered from higher levels of stress than the average population and persons who also worked in client-related professions such as medical doctors, nurses, and hospital staff. Dutch figures point in the same direction (CBS Citation2015). According to the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics (CBS Citation2015), the burnout rate for Dutch teachers in 2015 was 18%, which was higher than for any other profession. The highest rate of 21% burnout was found at urban junior vocational high schools (AOB Citation2015; Arbo Unie Citation2015; CBS Citation2015; DUO Citation2014; van Daalen Citation2010), which also happen to have the highest numbers of culturally and ethnically diverse classrooms. The majority of immigrant students in the Netherlands attend junior vocational education (CBS Citation2015). The over-representation of ethnically diverse students in junior vocational high schools seems to be associated with teacher burnout rates (AOB Citation2015; Arbo Unie Citation2015; CBS Citation2015; DUO Citation2014). Teacher burnout is affected by many different factors, including teachers’ attitudes and expectations (Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002; Vanheule and Verhaeghe Citation2004). The present study examines the possible link between cultural diversity and teacher burnout by examining the role of teachers’ multicultural attitudes, as well as their multicultural perceptions of school policy and school climate. In particular, the focus is on whether a (mis)match between teacher multicultural attitudes and their perceptions of school policy influences chance for burnout in teachers.

Though many teachers have grown up in a culturally diverse society, teachers are often not well prepared to deal with ethnic and cultural diversity in their classroom (Banks and McGee Banks Citation2004; Wubbels et al. Citation2006), which may lead to stress and burnout. The increasing ethnic and cultural diversity in schools and classrooms weighs heavily on teachers, and the reality of the educational setting at present is one of increasing ‘cultural mismatch’ (Cockrell et al. Citation1999) between teachers, students, and parents (Shor Citation2005; Tatar and Horenczyk Citation2003; Vedder and Horenczyk Citation2006). This affects teachers working with immigrant students and makes teachers less able to face the challenges posed by multicultural contexts. Lucas (Citation1997) discussed the mismatch between teaching styles developed for – and successfully implemented with – native-born children and those necessary for immigrant students, and classroom difficulties related to the students’ lack of basic knowledge about how the school functions. The results of this mismatch are, according to Lucas (Citation1997), immigrant students performing worse in academic tasks than non-immigrants and showing behavioural problems in class. It is, thus, imperative to address the complex and intricate challenges that teachers face who work with culturally and ethnically diverse student populations. All these ‘acculturative stressors’ may negatively affect the personal and professional well-being of teachers. An effect of this can be ‘diversity-related burnout’ (Tatar and Horenczyk Citation2003) among teachers. Diversity-related burnout is a distinct construct that reflects the negative impact of daily coping with cultural and ethnically diverse students. This type of burnout has been shown to be related to the degree of cultural heterogeneity of the school and to the teacher’s own views toward multiculturalism (Dubbeld et al. Citation2017; Tatar and Horenczyk Citation2003).

Although much research has been conducted on teachers’ burnout (AOB Citation2015; van Horn, Schaufeli, and Enzmann Citation2001), there is a lack of literature that focuses on teachers’ perceptions and attitudes of multiculturalism at ethnically diverse (junior vocational) high schools in relation to burnout (Bowen Citation2005; Dubbeld et al. Citation2017; Prick Citation2006; van Daalen Citation2010; Vink Citation2010). Research has shown that the perceptions and attitudes of teachers have a significant influence on the social atmosphere of the school and attitudes of the students (Banks Citation2004b; Vedder Citation2006).

Teachers bring their own cultural attitudes, values, hopes, and beliefs to the classroom (Banks Citation2004a). Knowledge and attitudes are closely interrelated, and both are likely to affect classroom practice (Banks Citation2004a; den Brok, Bergen, and Brekelmans Citation2006). As indicated by Vollmer (Citation2000), teachers’ perceptions and attitudes have a strong impact on the classroom’s educational and social climate. In particular, beliefs about inclusivity and heterogeneity in classrooms are one of the greatest predictors of teaching effectiveness (Stanovitch and Jordan Citation1998). Often, teachers are unaware of their ideological assumptions, which have been ‘naturalized’ to such an extent that they are seen as part of the ‘common sense’. Among teachers who work with immigrant students, these ideological assumptions include societal beliefs regarding newcomers’ acculturation and the role of the school in this process.

According to Reichers and Schneider (Citation1990), school climate is widely defined as the shared perception of ‘the way things are around here’. More specifically, school climate is the shared perception of organisational policies and procedures, both formal and informal. These shared perceptions and attitudes of organisational policies, practices, and procedures enable individuals to make sense of ambiguous and conflicting organisational cues. Hoy and Miskal (Citation2005) define school climate as ‘the set of internal characteristics that distinguishes one school from another and influences the behaviour of people’. This definition, which establishes school social climate as one of the key characteristics that distinguishes different schools from another, clearly identifies school climate as a critical variable to consider in the current study. Galloway et al. (Citation1982) suggested that teacher burnout may be mediated by school organisation and school climate despite objectively unfavourable conditions. It may well be that school climate and organisational culture within schools has an effect on the levels of burnout that teachers experience (Horenczyk and Ben-Shalom Citation2001; Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002).

An exploratory study in the Netherlands examined teachers’ attitudes regarding multicultural classrooms (Wubbels et al. Citation2006). These focus groups showed that teaching in multicultural classrooms requires specific competences in creating positive teacher–student relations and achieving student engagement. Teachers’ positive attitudes toward multicultural students facilitate inclusion in a mainstream setting because positive attitudes are closely and positively related to motivation to work with and to teach ethnically diverse students (Kalyava, Gojkovic, and Tsakiris Citation2007). Thus, positive beliefs toward inclusiveness are one of the key factors in facilitating the process of teaching and student learning. In contrast, negative beliefs and prejudice can have a detrimental effect on the school environment (Agirdag, Loobuyck, and Van Houtte Citation2012; Bakari Citation2003; Eisikovits Citation2008; Vollmer Citation2000), and consequently affect teachers’ stress levels and well-being.

According to Banks (Citation2004b), teachers should be aware of the major ideologies related to ethnic pluralism and be able to examine their own philosophical positions. The two major positions he distinguishes are the cultural pluralist ideology and the assimilationist ideology (Banks Citation2004a). The pluralist ideology is useful because it informs us about the importance of culture and ethnicity within society. The assimilationist ideology argues that the school should socialise youth, so they will be effective participants within the common culture and will develop commitments to its basic values and ideologies. In schools with an assimilationist orientation, the task of integrating immigrants is usually seen as marginal, and no major structural or pedagogical changes are considered necessary. Schools that adopt a pluralistic philosophy place much importance on the education of their immigrant students (Gillborn and Ladson-Billings Citation2004; Joshee Citation2004; Luchtenberg Citation2004; Partington Citation1998).

Historically, schools in Western societies have had assimilation rather than pluralism as their major goal (Banks Citation2004b; Gordon Citation1975). An assimilationist conception of citizenship existed in most Western democratic nation-states. Even though recently (Entzinger and Van der Meer Citation2004; Hofstede Citation1991; Scheffer Citation2014) Dutch society has become increasingly pluralistic, both culturally and ethnically, for a long time an assimilationist conception of citizenship and education existed in the Netherlands (Berry et al. Citation2006; Gordon Citation1975; Penninx et al. Citation1999). The students were expected to acquire the dominant culture of the school and society, but the school neither legitimised nor assimilated parts of the students’ cultures. In general, a pluralistic stance by teachers is likely more conducive to the adaptation of their immigrant students (Horenczyk and Ben-Shalom Citation2001; Rumberger and Palardy Citation2005; Vedder, Horenczyk, and Liebkind Citation2007), as well as contributes to a positive school climate (Agirdag et al. Citation2012; Bakari Citation2003; Kalyava, Gojkovic, and Tsakiris Citation2007; Stanovitch and Jordan Citation1998). However, in some cases immigrant students who behave in line with the assimilative viewpoint will adjust better when their teachers and other educational agents also hold assimilationist expectations (Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002; Vedder, Horenczyk, and Liebkind Citation2007).

Research has shown there is often a difference between teachers’ multicultural attitudes in school and towards society at large. A study by Horenczyk and Tatar (Citation2002) showed that teacher attitudes were highly assimilationist in the school context, whereas attitudes dealing with immigrants in the wider society were predominantly pluralistic. Although multicultural rhetoric is gaining ground in educational discourse, actual educational practices in many immigrant-receiving societies suggest that schools continue to seek to assimilate immigrant students into the societal mainstream (Olneck Citation1995). Many teachers working in multicultural classes are unable to move away from their own assimilationist attitudes and teaching styles (Berry and Kalin Citation1995; Eisikovits Citation2008; McInemey et al. Citation2001), which will likely have a negative effect on the school environment for both students and teachers. By holding on to an ideology that can have an aversive effect on a multicultural classroom, teachers might be causing themselves a lot of additional work stress. Teachers’ attitudes and perceptions toward school policy and school climate should be a central focus in research to understand teachers’ perceptions and attitudes vis-à-vis ethnic and cultural diverse students. School policy and school climate provide an identity for its members and generate commitment to the school organisation (Greenberg and Baron Citation2000).

The current study

There is little empirical research focussing on the factors that may lead to (diversity-related) burnout in multicultural classrooms. The present study took place at ethnically and culturally diverse junior vocational high schools in the Netherlands. The burnout rate at this type of schools is a dramatically high 21% (AOB Citation2015; Arbo Unie Citation2015; CBS Citation2015; DUO Citation2014). This study focuses on teachers’ multicultural attitudes, perceptions of school policy, and school climate in relation to general and diversity-related burnout. In particular, the focus was on whether a (mis)match between teacher multicultural attitudes and their perceptions of school policy influenced burnout in teachers. Only two studies could be identified that addressed some of these concepts (Dubbeld et al. Citation2017; Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002). In particular, the study by Tatar and Horenczyk (Citation2003) in Israel suggested that teachers working in multicultural schools can experience types of stress that add to regular teacher stress. They found the highest level of diversity-related burnout among teachers categorised as assimilationist and who work in schools that they perceive as assimilationist. Those teachers who embraced multiculturalism more strongly reported fewer feelings of stress when teaching in ethnically diverse classrooms (Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002; Vedder and Horenczyk Citation2006).

The following research questions were investigated: Is there an association between general and diversity-related burnout and teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perceptions toward school policy and school climate? If so, to what degree? Are there combinations of teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perceptions that are more or less beneficial (to blame) for general or diversity-related burnout?

Method

Participants and procedure

Respondents completed a self-report questionnaire consisting of four major parts, each including several sections. The questionnaire was distributed among 200 teachers working in five multicultural junior vocational high schools (VMBO) in a highly urbanised western part of the Netherlands. Dutch junior vocational education (VMBO) prepares students for intermediate vocational education, but it does not qualify them for a profession. The intermediate vocational training that follows after the VMBO can prepare students for a wide array of professions, educated at the so-called secondary vocational high school (MBO). The instructions stated that the questionnaire aimed to map teachers’ perceptions and impact of daily teaching in ethnically diverse classes in the Netherlands.

In total, 120 teachers completed the questionnaire (response rate 60%). Sixty-one female teachers (50.8%) and 59 male teachers (49.2%). The average age of the teachers was 43.07 years (SD = 10.14), ranging from 22 to 64 years old. The mean number of years of teaching experience was 14.96 (SD = 10.76), ranging from 1 to 40. The majority of teachers (98 or 82%) were born in the Netherlands, and 22 of the teachers (18%) were non-native born.

Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The survey began with questions about teachers’ background characteristics, namely age, gender, education, years of teaching experience, school subject, country of birth, and teachers’ religion.

Multicultural teacher attitudes

The second section measured teachers’ attitudes toward multiculturalism, using the ‘Multicultural Ideology Scale’, developed by Berry and Kalin (Citation1995) and translated to Dutch general and educational context using translation and back translation (Dubbeld Citation2007). This scale measured teachers’ attitudes toward multiculturalism and consisted of six items describing potential characteristics of teachers’ attitude toward multiculturalism. Respondents indicated their agreement with each statement on a four-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). The instrument consisted of two subscales, pluralistic ideology (two items; Cronbach’s alpha = .78, for example, ‘We have to help immigrants from various countries of origin to retain their own cultural background’) and assimilationist ideology (four items; Cronbach’s alpha = .65, for example, ‘It is best for the Netherlands when immigrants distance themselves as quickly as possible from their cultural background’).

The third section included teachers’ perceptions of the school’s multicultural policy and school climate, which were primarily based on the ‘Perceived Multicultural School Climate Questionnaire’ (Greenberg and Baron Citation2000; Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002) and the MEOCS (Military Equal Opportunity Climate Survey’s used in the USA and Canadian Army; Landis, Dansby, and Tallarigo Citation1996). The original questionnaires were translated to the Dutch general and educational context using translation and back translation (Dubbeld Citation2007). The questionnaire examined teachers’ perceptions at three levels: (A) perceptions of school policy, (B) perceptions of school climate for students, and (C) perceptions of school climate for teachers.

(A) Pluralistic school policy – This part consisted of five possible situations encountered by teachers at their school with regard to multiculturalism. For example, ‘My school values students’ diverse cultural backgrounds’ Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.75. Teachers estimated the extent to which each of these situations were likely to occur in their school on a four-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). The higher the score, the more pluralistic teachers perceived their school to be.

(B) Cross-cultural interactions between students – This part consisted of a list of three statements related to the perceived integration and interaction of students of different ethnic backgrounds. Teachers indicated the extent to which they believed students of different ethnic and cultural background interacted, both during and after class. An example of a statement was ‘Native and non-native students spend time with each other during breaks’. Answers were on a four-point scale from 1 (‘totally disagree’) to 4 (totally agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84. The higher the score, the more different students were perceived to interact with each other.

(C) Teachers’ openness to diversity – This part consisted of two statements reflecting how teachers at the school handled diversity: ‘Teachers at this school take students’ cultural background into account’ and ‘Teachers at this school discipline native students less often than non-native students for the same misbehaviour’. Teachers indicated the extent to which they agreed with these statements on a four-point scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (definitively agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79. The higher the score, the more open to diversity teachers were perceived to be.

General and diversity-related burnout

The fourth part of the survey consisted of scales for general and diversity-related burnout developed by Tatar and Horenczyk (Citation2003). The section consisted of a list of eight items describing potential characteristics of teachers’ burnout. The items were adapted from a modified Hebrew version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach and Jackson Citation1986) and were also used in a study by Tatar and Yahav (Citation1999). The modified Hebrew version was developed in an extensive study aimed at revealing the relevant items of burnout, as reported by Israeli teachers (Tatar and Horenczyk Citation2003). The questionnaire was adapted to the Dutch general and educational context using translation and back translation (Dubbeld Citation2007). All items were formulated on four-point Likert scales, with a response format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). One sample of the five items for general burnout is: ‘I feel that working closely with students causes a great deal of tension’. Three items dealt with the potential characteristics of teachers’ diversity-related burnout. A sample item was: ‘Daily working with immigrant students frustrates me’. The reliability of the two scales was good; Cronbach’s alpha was 0.77 for the general burnout scale, and 0.75 for the diversity-related burnout scale.

Statistical analyses

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 19) was used to analyse the data. First, descriptive analyses were carried out. This included computing mean scores and standard deviations for each of the scales of the questionnaire. Subsequently, to answer the research questions, correlations between background characteristics, perceptions, and burnout were computed. To test the research questions, two multiple regression analyses with assimilative and pluralistic attitudes and perceptions of school policy and school climate as predictors and general burnout and diversity-related burnout as dependent variables, respectively, were performed. The backward method was used to only identify the strongest predictors of burnout.

Subsequently, a cluster analysis was conducted to create clusters with the five predictors as variables. In cluster analysis, respondents are assigned to groups (clusters) based on a set of variables or objects so that the respondents in the same cluster are more similar to each other than to those in other clusters (Tan, Steinbach, and Kumar, Citation2005). In the current study, cluster analysis was used to identify groups of teachers (profiles) who showed different patterns of scores across the five predictors. Hierarchical clustering with squared Euclidian distances was used to ensure that profiles were optimally different from each other. Ward’s method (Citation2001) was selected to make sure that teachers within the profile were optimally similar. Solutions with two to six clusters were tested in the search for the optimal number of profiles. For each of the cluster solutions, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to establish the amounts of variance explained by the solution(s) and to determine whether the profiles were significantly different from each other. The optimal number of profiles was determined to be three. Solutions with fewer than three profiles explained considerably lower amounts of variance in each of the five variables. More than three profiles explained more variance in teachers’ scores, but these solutions had few respondents in some profiles and, moreover, in the three cluster solution, each of the profiles was still interpretable, whereas this was much harder in solutions with more clusters. The three profiles will be discussed in the results section. In addition, ANOVAs was conducted to test whether the three clusters of teachers differed in terms of general and diversity-related burnout. All tests were conducted at the 95% confidence level; with a sample of 120 the margin of error was 8.92.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

provides the means and standard deviations for all the variables in this study. The overall means for general and diversity-related burnout were just below the midpoint of the scale, both scales scored around 2 (on a scale from 1 to 4). The standard deviations of both scales were moderate, which means that there were some differences between teachers.

Table 1. The means and standard deviations attitudes perceptions in relation to burnout.

The scale of pluralistic attitudes had a mean of M = 2.60 (SD = 0.57), which was higher than the mean of assimilative attitudes M = 1.85 (SD = 0.50), and both were around the midpoint of the scale. This means there was a variety of attitudes among teachers, but on average attitudes were more pluralistic than they were assimilationist. The scale of pluralistic school policy had a mean of M = 3.07 (SD = 0.41), implying that on average teachers perceived their school to be rather pluralistic. Cross-cultural interaction between students had a mean of M = 2.39 (SD = 0.61), which is just above the midpoint of the scale, indicating that teachers perceived that students of different ethnic backgrounds interacted somewhat with each other. Finally, the scale of teachers’ openness to diversity had a mean of M = 3.16 (SD = 0.58), which means that on average teachers were perceived by their colleagues to be rather open to diversity.

Correlations were computed to explore relationships between teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perceptions towards school policy and school climate and their burnout scores (see ). Results indicated a positive relationship between assimilative attitudes and both forms of burnout, however, there was no statistically significant relationship between teachers’ pluralistic attitudes and both burnouts. The more teachers’ attitudes were assimilative, the higher their score on both burnouts. Teachers’ perceptions of school policy, cross-cultural interactions between students, and teachers’ openness to diversity all correlated negatively with both burnouts. More specifically, the more pluralistic teachers perceived their school to be, the more they perceived different students to interact, and the more they perceived their fellow teachers to be very open to students’ different cultural backgrounds, the lower their burnout scores were.

Table 2. Correlations between all main variables (N = 120)ᵃ.

General burnout, diversity-related burnout, and teachers’ perceptions of school policy and school climate

To examine which attitudes or perceptions of school policy and climate variables best predict burnout and diversity-related burnout, two regression analyses were performed using the backward method (see and ). The results of the regression analysis for general burnout showed that, initially when all variables were included in the analysis (R2 = .16), only assimilative attitude was a significant predictor of general burnout, β = .25, p < .01. In the final model (R2 = .15), three variables were significant predictors of general burnout, namely assimilative attitude, β = .20, p < .05, pluralistic school policy, β = −.20, p < .05, and cross-cultural interactions between students, β = −.18, p < .05. Thus, the less assimilative teachers’ attitudes were, the more they perceived the school to be pluralistic, and the more they perceived different students to interact, the lower their general burnout scores were.

Table 3. Regression analysis predicting general burnout using the backward method.

Table 4. Regression analysis predicting diversity-related burnout using the backward method.

The results of the regression analysis for diversity-related burnout showed a slightly different picture. In the model with all predictors (R2 = .18), just as with general burnout, only assimilative attitude was a significant predictor, β = .33, p < .001. However, in the final model (R2 = .17), three variables were included, but only two were statistically significant, namely, assimilative attitude, β = .29, p < .001, and cross-cultural interactions between students, β = −.18, p < .05. Thus, the less assimilative teachers’ attitudes and the more they perceived students with different ethnic backgrounds to interact, the lower their diversity-related burnout scores were.

Cluster analysis findings

Subsequently, based on the questionnaire data, a cluster analysis was conducted to create clusters with the five predictors as variables. Three clusters of teachers were identified, so that the respondents in the same cluster are more similar to each other than those in other clusters.

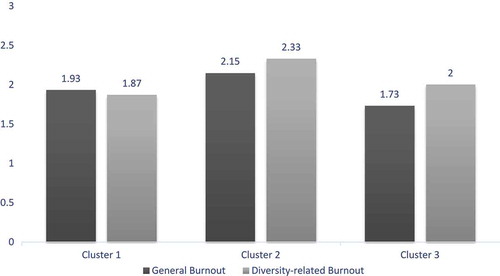

As shown in , there were three substantial groups of teachers that could be labelled as followed: (1) Relative assimilative attitude, (2) No pronounced assimilative attitude, (3) Moderate assimilative attitude. In cluster 1, teachers showed relatively high assimilative attitudes, but they saw their school as rather pluralistic. They seemed to view teachers as rather tolerant of student diversity, but they perceived the interaction between students as average. In cluster 2, teachers showed no really pronounced attitudes, yet their perceptions of the school were rather pluralistic, and especially the school climate was perceived as open to diversity with much student interaction. In cluster 3, teachers held the least assimilative attitudes, they perceived their school as rather pluralistic, but when it came to climate they perceived the lowest level of interaction between different students, though they did think fellow teachers were very open to student diversity.

Table 5. Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) scores by clusters.

Additional analyses of variance were conducted to test whether teachers from the three clusters differed with respect to their general and diversity-related burnout scores (see ). The clusters of teachers differed both on general burnout, F(2,117) = 7.37, p < .001, as well as on diversity-related burnout scores, F(2,117) = 12.03, p < .001. Teachers from cluster 2 had higher general burnout scores (M = 2.15, SD = .50) than teachers from cluster 3 (M = 1.73, SD = .46). The same difference was found for diversity-related burnout scores (M = 2.33, SD = .50 and M = 2.00, SD = .43 for cluster 2 and cluster 3 teachers, respectively). In addition, teachers from cluster 1 scored lower (M = 1.87, SD = .45) on diversity-related burnout than teachers from cluster 2 (M = 2.33, SD = .50).

Discussion

The research described in this article aimed to answer the questions whether there is an association between general and diversity-related burnout and teachers’ multicultural attitudes and perceptions toward school policy and school climate? If so, to what degree? Are there combinations of teachers’ attitudes and perceptions that are more or less beneficial for general or diversity-related burnout? The results reported in this paper showed that the more assimilative teachers’ attitudes were and the less they perceived school policy and school climate as pluralistic, the higher general and diversity-related burnout scores, and vice versa. The less assimilative teachers’ attitudes were and the more they perceived different students to interact, the lower their general burnout scores.

Regarding diversity-related burnout, the results were different; the less assimilative teachers’ attitudes were, and the more they perceived students with different backgrounds to interact, the lower their diversity-related burnout scores. It was shown that the highest level of burnout was present in teachers who held assimilationist attitudes and worked in schools that they perceived as having a policy of pluralism. The less assimilative teachers’ attitudes were, the more they perceived the school to be pluralistic. It cannot be ruled out that the effect is actually in the opposite direction, with teachers with burnout developing and adopting assimilationist attitudes as a result of their unsuccessful attempt to implement a more pluralistic approach. The assimilationist strategy can be perceived by the burnout teacher as an easier and more efficient way to deal with culturally and ethnically diverse classes. Teachers’ attitudes and perceptions in school are influenced by aspects of school organisation and school policy as it relates to cultural and ethnic diversity (Banks Citation2004a; Horenczyk and Tatar Citation2002; Vedder, Horenczyk, and Liebkind Citation2007). Most teachers are socialised within society-schools and teacher education institutions with mainstream-centric norms, teachers therefore likely embrace an assimilationist stance and view pluralistic ideologies as radical (Banks Citation2004b; Eldering Citation2002; Eisikovits Citation2008). According to Eisikovits (Citation2008), many teachers working in multicultural classes are unable to move away from their own assimilationist stance and teaching habits, while others do not know how to deal with immigrant students showing some degree of seclusionism. In an absence of systematic training, teachers rely heavily on personal experience as a source of knowledge.

The study also investigated what distinct profiles of attitudes and perceptions teachers have and how these profiles are associated with general and diversity-related burnout. This analysis revealed three distinct and substantial profiles, labelled as ‘a relative assimilative attitude’, ‘no pronounced assimilative attitude’, and ‘moderate assimilative attitude’. The findings enhance our understanding of different ways in which general and diversity-related burnout can be experienced. There were important and meaningful differences in teachers’ attitudes. The findings indicated that the highest levels of assimilationist attitudes among teachers who saw their school as rather pluralistic were found in profile one and three. As for profile two, teachers showed no pronounced assimilative or pluralistic attitudes. The results showed that when teachers did not have a clear, outspoken assimilationist or pluralistic attitude they were more susceptible for general and diversity-related burnout. The highest levels of both burnouts were found among teachers categorised as assimilationist and who work in schools perceived by them to be pluralistic. Likewise pluralistic teachers who work in what they perceive as pluralistic settings showed the lowest degrees of both burnouts. Thus, it seems that a pluralistic attitude is a necessary condition for the prevention of both burnouts.

Limitations and implications

Overall, the findings of this study provided some useful insights with respect to teachers’ attitudes and perceptions toward school policy and school climate in relation to general and diversity-related burnout. The current study had some limitations that should be mentioned, which might have implications for further research. A first limitation concerned the selective sample of the study; the current study only focused on teachers working at ethnically diverse vocational high schools in the highly urbanised Western part of the Netherlands. Second, the study included self-report measures. The use of the questionnaire seemed to be the only way to reach a large group of teachers to profile their attitudes and perceptions, but at the same time it implied that no in-depth information was gained about the nature and impact of burnout that was experienced.

The further development and refinement of specific scales for investigating teachers’ profiles is necessary. This kind of information might be helpful for further describing and interpreting the profiles. It is recommended the present research design be extended with other methodological strategies, including qualitative techniques and longitudinal studies, that would shed light on more complex relationships between the variables, in addition to exposing the meanings of each of these for teachers, the students, students’ parents, and the school organisation. In-depth interviews with teachers would be especially interesting for further research.

This research may contribute to better understanding of the complex and often conflictual role that teachers need to develop and perform when working in multicultural classrooms. This understanding can help them face challenges associated with ethnically and culturally diverse classes. This can be done by identifying teachers with high levels of general and diversity-related burnout to provide them with the necessary assistance, and determining the factors which contribute to general and diversity-related burnout, both at the level of teacher-student and teacher-class interactions, as well as at school policy level (Tatar and Horenczyk Citation2003; Vedder Citation2006).

The results of this study should be taken as an indication that all is not well in the teaching profession in the Netherlands. Efforts are needed to change the attitudes and perceptions of teachers, so that the school evolves into an institution that cherishes cultural and ethnic diversity as a resource for development and learning, also for teachers (Vedder and Horenczyk Citation2006). Within this context, multicultural teacher training is important to prepare teachers for their role in ethnically diverse classes. Effective teacher education programmes should help teachers explore and clarify their own ethnic and cultural identities and develop more positive attitudes toward other racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. To change the role of the school from being a cultural transmitter into being a cultural transformer, the approach of teachers and schools needs to change (Banks Citation2004a). To succeed in this, in turn, multicultural teacher training will have to take on a more important role (Vedder Citation2006).

Providing learning opportunities for the school staff to learn how to organise differentiation practices within a whole class is absolutely necessary to prevent them from becoming entangled in vicious circles leading to more stress and burnout. Increased attention to the expectations of teachers regarding their immigrant students is also necessary. Determination and support of policy makers is required to provide schools and teachers with the necessary means to cope with arising challenges, and gain more insight in such challenges by studying these topics in depth. Although this study was carried out in the Netherlands, the aforementioned implications may also be applicable for teachers who work with ethnic diverse students elsewhere.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anneke Dubbeld

Anneke Dubbeld is a Ph.D. student of the Welten Institute, at the Open University of the Netherlands. She is working on a project about teachers’ multicultural attitudes in relation to general burnout and diversity-related burnout, among teachers working in urban junior vocational high schools in the Netherlands and with cultural heterogeneous classes in the Dutch context.

Natascha de Hoog

Natascha de Hoog is an assistant professor of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at the Open University of the Netherlands, where she teaches research methods. Her research interests include topics such as attitudes & behaviour change, social identity, communication & affect, and health behaviour.

Perry den Brok

Perry den Brok is full professor and chair of the Education & Learning Sciences group at Wageningen University and Research. His research interests include learning environments, science education, teacher learning and professional development, interpersonal relationships in education and multicultural education. He also acts as teacher educator and is involved in educational innovation projects, both at the level of secondary as well as higher education.

Maarten de Laat

Maarten de Laat is director of the Learning, Teaching & Curriculum division at the University of Wollongong. His research concentrates on social learning, networked learning relationships and use of digital technologies to design and facilitate, learning and innovation student-centred online learning environments.

References

- Agirdag, O., P. Loobuyck, and M. Van Houtte. 2012. “Determinants of Attitudes toward Muslim Students among Flemish Teachers: A Research Note.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 368–376. doi:10.1111/jssr.2012.51.issue-2.

- AOB. 2015. Algemene Nederlandse Onderwijs Bond [Research about Teachers Working Conditions in Relation with Burnout]. Utrecht: The Netherlands.

- Arbo Unie. 2015. Ministerie Van Sociale Zaken En Werkgelegenheid (Szw) [Research about Teachers’ Burnout in the Netherlands]. The Hague: The Netherlands.

- Bakari, R. 2003. “Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes toward Teaching African American Students: Contemporary Research.” Urban Education 38: 640–654. doi:10.1177/0042085903257317.

- Banks, J. A. 2004a. “Multicultural Education: Historical Development, Dimensions, and Practice.” In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, edited by J. A. Banks and C. McGee Banks, 3–29. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Banks, J. A., ed. 2004b. Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Banks, J. A., and C. McGee Banks. 2004. Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Banting, K., and W. Kymlicka. 2004. Do Multiculturalism Policies Erode the Welfare State? School of Policy Studies, Working Paper 33.

- Ben-Perez, M., B. Eilam, and E. Yankelevitch. 2006. “Classroom Management in Multicultural Classrooms in an Immigrant Country: The Case of Israel.” In Handbook of Classroom Management Research, Practice, and Contemporary Issues, edited by C. M. Evertson and C. S. Weinstein, 1121–1139. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berry, J. W., J. S. Phinney, D. Sam, and P. Vedder, eds. 2006. Immigrant Youth in Cultural Transition: Acculturation, Identity and Adaptation across National Contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Berry, J. W., and R. Kalin. 1995. “Multicultural and Ethnic Attitudes in Canada: An Overview of the 1991 National Survey.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 27: 301–320. doi:10.1037/0008-400X.27.3.301.

- Bowen, P. 2005. Anxiety and Intimidation in the Bronx and the Bijlmer: An Ethnographic Comparison of Two Schools. Dutch University Press. The Netherlands: Amsterdam.

- Brok, P. D., T. Bergen, and M. Brekelmans. 2006. “Convergence and Divergence between Teachers’ and Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Behaviour in Dutch Secondary Education.” In Contemporary Approaches to Research on Learning Environments: World Views, edited by D. L. Fisher and M. S. Khine, 125–160. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Castles, S., and M. J. Miller. 2003. The Age of Migration. International Population Movements in Modern World. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2015. Ziekteverzuim Overheid [Absenteïsme Gouvernement]. CBS: The Netherlands: The Hague.

- Cockrell, K. S., P. L. Placier, D. H. Cockrell, and J. N. Middleton. 1999. “Coming to Terms with “Diversity” and “Multiculturalism” in Teacher Education: Learning about Students, Changing Out Practices.” Teaching and Teacher Education 15 (4): 351–366. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00050-X.

- Dubbeld, A. 2007. “Multiculturalism and Stress (In Dutch).” Internal report, department of Educational studies. Leiden, the Netherlands: Leiden University.

- Dubbeld, A., N. de Hoog, P. Den Brok, and M. de Laat. 2017. “Teachers’ Attitudes toward Multiculturalism in Relation to General and Diversity-Related Burnout.” European Education. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/10564934.2017.1401435.

- DUO. 2014. Bureau Onderwijsonderzoek: Werkdruk in het primair en voortgezet onderwijs [Work Pressure in Primary and Secondary Education]. Utrecht: The Netherlands.

- Eisikovits, R. A. 2008. “Coping with High-Achieving Transnationalist Immigrant Students: The Experience of Israeli Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 277–289. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.06.006.

- Eldering, L. 2002. Culture and Education: Intercultural Pedagogy from an Ecological Perspective. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Lemnis caat.

- Entzinger, H., and J. Van der Meer. 2004. Transnational Nederland. Immigratie En Integratie [Transnational Immigration and Integration in the Netherlands]. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij De Arbeidspers.

- Galloway, D., F. Pankhorst, C. Boswell, and K. Green. 1982. “Sources of Stress for Class Teachers.” National Education 64: 164–169.

- Gillborn, D. 2004. “Anti-Racism: From Policy to Practice.” In The RoutledgeFalmer Multicultural Reader, edited by G. Ladson-Billings& and D. Gillborn, 35–48. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Gordon, M. M. 1975. “Toward a General Theory of Racial and Ethnic Group Relations.” In Ethnicity: Theory and Experience, edited by N. Glazer and D. P. Moynihan, 84–110. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Greenberg, J., and R. A. Baron. 2000. Behavior in Organizations. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Hofstede, G. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

- Horenczyk, G., and U. Ben-Shalom. 2001. “Multicultural Identities and Adaptation of Young Immigrants in Israel.” In Ethnicity, Race, and Nationality in Education: A Global Perspective, edited by N. K. Shimahara, I. Holowinsky, and S. Tomlinson-Clarke, 57–80. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Horenczyk, G., and M. Tatar. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes toward Multiculturalism and Their Perceptions of the School Organizational Culture.” Teaching and Teacher Education 18 (4): 435–445. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00008-2.

- Hoy, W. K., P. A. Smith, and S. R. Sweetland. 2005. “The Development of the Organisational Climate Index for High Schools: Its Measure and Relationship to the Faculty.” High School Journal 8: 38–49.

- Joshee, R. 2004. “Citizenship and Multicultural Education in Canada: From Assimilation to Social Cohesion.” In Diversity and Citizenship Education: Global Perspectives, edited by J. A. Banks, 127–156. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kalyava, E., D. Gojkovic, and V. Tsakiris. 2007. “Serbian Teachers’ Attitudes toward Inclusion.” International Journal of Special Education 2: 30–35.

- Koopmans, R., I. Michalowski, and S. Waibel. 2012. “Citizenship Rights for Immigrants: National Political Processes and Cross-National Convergence in Western Europe, 1980–2008.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (4): 1202–1245. doi:10.1086/662707.

- Landis, D., M. R. Tallarigo, and R. S. Tallarigo. 1996. “The Use of Equal Opportunity Climate in International Training.” In Handbook of Intercultural Training, edited by D. Landis and R. S. Bhagat, 244–263. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lucas, T. 1997. Into, Through, and beyond Secondary School: Critical Transitions for Immigrant Youth. Arlington, VA: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Luchtenberg, M., ed. 2004. Migration, Education, and Change. New York: Routledge.

- Maslach, C., and W. B. Schaufeli. 1993. “Historical and Conceptual Development of Burnout.” In Professional Burnout: Developments in Theory and Research, edited by W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, and T. Marek, 1–16. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

- Maslach, C., and S. E. Jackson. 1986. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- McInemey, V., D. M. McInemey, M. Cincotta, P. Totaro, and D. Williams. 2001. Teachers Attitudes To, and Beliefs About, Multicultural Education: Have There Been Changes over the Last Twenty Years? Australia: University of Western Sydney.

- Olneck, M. R. 1995. “Immigrants and Education.” In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, edited by J. A. Banks and C. A. M. Banks, 310–327. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Partington, G. 1998. Perspectives on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education. Katoomba. NSW, Australia: Social Science Press.

- Penninx, R., J. Rath, K. Groenendijk, and A. Meyer. 1999. “The Politics of Recognizing Religious Diversity in Europe.” Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences 35: 53–67.

- Prick, L. G. M. 2006. Drammen Dreigen Draaien. Hoe Onderwijs Twintig Jaar Lang Werd Vernieuwd [Nagging, Threatening and Turning. How Education Renewed in Twenty Years]. Amsterdam: Mets & Schild.

- Reigers, A. E., and B. Schneider. 1990. “Climate and Culture: An Evolution of Constructs.” In Organisational Climate and Culture, edited by B. Schneider, 5–39. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Rumberger, R., and G. Palardy. 2005. “Does Segregation Still Matter? the Impact of Student Composition on Academic Achievement in High Schools.” Teacher College Record 107: 1999–2045.

- Scheffer, P. 2014. Het Land Van Aankomst [The Country of Arriving]. Amsterdam: Bezige Bij.

- Shor, R. 2005. “Professionals’ Approach Towards Discipline in Educational Systems as Perceived by Immigrant Parents: The Case of Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel.” Early Child Development and Care 175: 457–465. doi:10.1080/0300443042000266268.

- Stanovitch, P. J., and A. Jordan. 1998. “Canadian Teachers’ and Principals’ Beliefs about Inclusive Education as Predictors of Effective Teaching in Heterogeneous Classrooms.” Elementary School Journal 98: 221–238. doi:10.1086/461892.

- Tan, P. N., M. Steinbach, and V. Kumar. 2005. Introduction to Data Mining. Boston, MA: Pearson Addison-Wesley.

- Tatar, M., and G. Horenczyk. 2003. “Diversity- Related Burnout among Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 19: 397–408. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00024-6.

- Tatar, M., and V. Yahav. 1999. “Secondary School Pupils’ Perception of Burnout among Teachers.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 69 (4): 457–468.

- van Daalen, R. 2010. Het VMBO Als Stigma. Lessen, Leerlingen En Gestrande Idealen [Stigma VMBO. Lessons, Students and Lost Ideals]. Amsterdam: Augustus.

- van Horn, J. E., W. B. Schaufeli, and D. Enzmann. 2001. “Teacher Burnout and Lack of Reciprocity.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01376.x.

- Vanheule, S., and P. Verhaege. 2004. “Powerlessness and Impossibility in Special Education: A Qualitative Study on Professional Burnout from a Lacanian Perspective.” Human Relations 57: 497–519. doi:10.1177/0018726704043897.

- Vedder, P. 2006. “Black and White Schools in the Netherlands.” European Education 38 (2): 36–49. doi:10.2753/EUE1056-4934380203.

- Vedder, P., and G. Horenczyk. 2006. “Acculturation and the School Context.” In Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation, edited by D. L. Sam and J. W. Berry, 419–438. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vedder, P., G. Horenczyk, and K. Liebkind. 2007. “Ethno-Culturally Diverse Education Settings: Problems, Challenges and Solutions.” Educational Research Review 1: 157–168. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2006.08.007.

- Vink, A. 2010. Witte Zwanen, Zwarte Zwanen. De Mythe Van De Zwarte School. Segregatie in Scholen En Samenleving [White Swans, Black Swans. The Myth of the Black School. Segregation in Schools and Society]. Amsterdam: Querido.

- Vollmer, G. 2000. “Praise and Stigma: Teachers’ Constructions of the ‘Typical ESL Student’.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 21 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1080/07256860050000795.

- Ward, C. 2001. “The A, B, Cs of Acculturation.” In Handbook of Culture and Psychology, edited by D. Matsumoto, 411–445. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Wubbels, T., P. Den Brok, I. Veldman, and J. van Tartwijk. 2006. “Teacher Interpersonal Competence for Dutch Secondary Multicultural Classrooms.” Teachers and Teaching Education 12: 407–433. doi:10.1080/13450600600644269.