ABSTRACT

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an important means to address conflicts, support local development and build trust between businesses and civil society. Yet CSR often fails to live up to its ambitions and can even exacerbate conflicts between companies and communities. In this article we consider how changing CSR strategies over the past four decades between Brazilian company Vale to Norwegian company Hydro have fomented or mitigated company–community conflicts in Northern Brazil. We find that paternalistic and philanthropic approaches of Vale over time led to deep resentment and mistrust due to underdevelopment and environmental damages. Moreover, while Hydro’s more modern CSR strategies sought to deepen community engagement and build legitimacy, the company has struggled in addressing the legacies inherited from Vale and past and current civil society grievances. The case suggests that even forward-thinking CSR approaches are vulnerable to failure where they prioritise business risk over community engagement, neglect to account for past legacies in areas of operation, and fail to create a shared vision of future development. It suggests that EI companies should both understand and engage with their social and environmental impacts in the past, present, and future and create shared economic benefits in the short and long term in order to address social conflicts.

Introduction

Actors in the extractive resources sector often operate in challenging environments. In poor, unstable or ‘low-governance’ areas, extractive industries (EI) companies and other multinational enterprises (MNEs) are often the primary economic actors, wield outsize political power, and are required to address complex issues that would otherwise be the responsibility of government.Footnote1 Local communities often maintain a tense relationship with EI firms, beholden to companies for local development, while holding grievances related to inadequate revenue sharing, limited consultation, and environmental damages.Footnote2 These grievances can shape deep-rooted social conflicts and present operational risks for companies, particularly where they manifest as violent opposition and social instability.Footnote3 As such there is ‘a growing appreciation that unmitigated environmental and social risks have the potential to negatively influence the financial success of large-scale developments in the extractive industries’.Footnote4

In recognising that older more traditionally philanthropic approaches to CSR in the EI have failed to deliver socio-economic benefits,Footnote5 building relationships with stakeholders and strengthening the companies’ social licence to operate (SLO) is becoming more important.Footnote6 It is seen as increasingly necessary for businesses to prioritise deeper community engagement, environmental responsibility and support for local development to improve livelihoods of local communities and reduce social conflicts negatively impacting businesses. This is reflected in new CSR paradigms that have been embraced by global actors in the EI. Transformative CSR or CSR 2.0Footnote7 and Creating Shared Value (CSV)Footnote8 are approaches to corporate citizenship that broadly posit that businesses will be more successful where they create value for both themselves and the local communities, govern responsibly and act with environmental integrity.

How then might shifting approaches to CSR and community engagement shape dynamics of long-standing social conflicts in extractive sectors? We consider this question using a case study of alumina refining operations of Vale and Hydro in Barcarena in the Brazilian Amazon over the past four decades. We utilise open-ended qualitative interviews with civil society, industry and government stakeholders combined with analysis of secondary material on the CSR approaches of Vale and Hydro. We find that paternalistic approaches of Vale led to deep resentment and mistrust stemming from under-development and environmental damages. Moreover, while Hydro sought to deepen community engagement and build legitimacy since it assumed majority ownership in 2011, the company today struggles with legacies inherited from Vale and the deficiencies in their own CSR approach.Footnote9 This case shows that even well-intentioned CSR can be ineffective or damaging where firms one-sidedly promote their own vision of ‘socially responsible development’ and fail to understand and respond to the territorial legacies in areas of operation. To reduce social conflicts, it would therefore be wise of EI firms to fully engage with the past, present and future operational impacts of their activities, and develop shared visions with communities to address short-term social and ecological challenges and long-term institutional challenges.

Social conflict and CSR in the extractive industries

EI companies are criticised for adverse social, environmental, political and economic impacts.Footnote10 While violent conflicts often receive attention,Footnote11 social conflicts – the continuum of everyday contention and grievances a community expresses against EI corporations – are inherent in the EI.Footnote12 Inadequate community engagement or consultation, unfulfilled expectations vis-à-vis economic development, insufficient revenue sharing, lack of compensation for losses due to mining activity, land dispossession and environmental degradation may trigger and sustain opposition.Footnote13

Such grievances can lead to intractable social conflicts. Operations of EI firms have a real or perceived effect of damaging environmental commons and inadequately supporting local development or resource sharing, which can undergird local opposition. Moreover, this often intersects with existing power dynamics in extractive regions, and can be tied to longstanding political, cultural, geographic or identity-based forms of exclusion or oppression.Footnote14 This confluence of historical and contemporary factors can lead to enduring opposition to extraction.

Where this occurs, communities engage in both semi-organised disruptive activities designed to affect operations and place political pressure on companies and governments. Often increasingly empowered and connectedFootnote15 local communities voice grievances to elicit some form of concession or dialogue from companies, or political response – such as environmental regulation – from government. For companies, the operational and reputational risks of social conflict are clear.Footnote16 Strikes, protests and riots can disrupt production, logistics, supply chains, materially damage facilities or assets, and further stoke resentment among workers or local communities. Procedural opposition, including formal complaints or legal actions, can be just as disruptive, with new regulations or injunctions radically delaying existing operations or halting explorations into new projects.Footnote17

As such, expectations of corporate conduct have changed in recent decades, particularly vis-à-vis labour conditions, environmental and social justice and sustainable development.Footnote18 Companies voluntarily integrate policies and regulations concerning CSR into their operational strategies,Footnote19 with a greater onus on meaningfully contributing to social development.Footnote20 Yet beyond CSR as organisational risk management in precarious environmentsFootnote21 there is value in firms building relations and long-term legitimacy and creating value for local communities.Footnote22 In establishing mutually beneficial relationships – or shared valueFootnote23 – between companies and civil society, open engagement and mitigating negative socio-environmental impacts is central.Footnote24 These relationships underpin the SLO, where companies establish legitimacy, credibility and trust with local communitiesFootnote25 through activities including social programmes, basic service delivery, vocational training, and local development or infrastructure projects.Footnote26

Yet the potential for CSR to address conflicts and deliver societal benefits varies depending on underlying logics. CSR may be seen as a firm’s moral imperative or simply a means to improve profitability.Footnote27 CSR may be explicit, where firms expressly internalise their responsibility for societal interests, or implicit where firms simply deliver the (mandatory and customary) obligations of corporate actors.Footnote28 Impact also depends on how strategies are implemented at the global and local levels or within companies, as well-designed and intentioned CSR portfolios may in certain cases carry little weight in the firms overall strategic decisions. Given this, CSR activities are often criticised as a branding or greenwashing activity that fails to meaningfully create positive impacts for local communities, and even as an action which may shape further conflicts.Footnote29 However, while firms often do not properly internalise costs of social conflicts,Footnote30 CSR activities are core to their successful long-term operational strategiesFootnote31 and are central to how businesses can contribute to prosperous and peaceful societies.Footnote32

Case and methodological approach

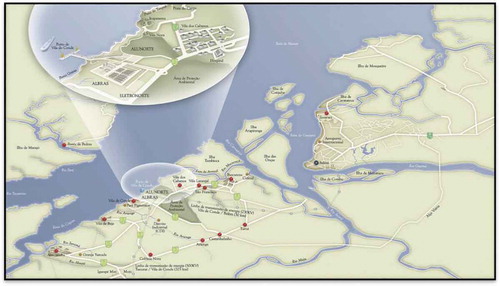

This case examines trajectories of resources companies Vale and Hydro in Barcarena municipality ( and ). Situated in the Amazon River delta in mineral-rich Pará state approximately 40 km from the state capital Belém, the town of Barcarena (population 120,000) is strategically important both due to its processing and refining industry, and major road, rail and sea linkages facilitating mineral, cattle and soya exports. Despite the third highest GDP per capita in Pará, Barcarena has extremely low levels of development, struggling with unmanaged urban growth and high rates of violence.

In the late 1970s, the Brazilian state-owned utility Vale was established in Barcarena. Construction commenced in 1978, with the first plant, Albras, opening in 1985, and Alunorte, the world’s largest alumina refinery, following in 1995. Numerous EI companies and associated services followed in subsequent years. Vale was privatised in 1997, becoming one of the largest extractive companies in the world. In 2011 Norwegian resources company Hydro, a minority shareholder, bought Vale’s shares to assume a 91 per cent ownership stake in Alunorte and a 51 per cent stake in Albras, becoming the largest foreign investor in the region.

In examining these companies, we use a qualitative case study methodology with a semi-structured interview design. As methodological challenges abound in studies of business–society relations,Footnote33 there is considerable scope for qualitative methodologies to elucidate motivations, intentions, perceptions and mechanisms underlying business–society interactions.Footnote34 Moreover, this strategy is suitable for engaging with management stakeholders about business strategies, impacts and challenges, and with vulnerable populations to elaborate on socially or politically contentious topics. Rather than testing specific hypotheses, our approach identified perspectives of relevant populations and built a narrative from their responses focusing on the drivers of social conflicts between EI companies and civil society in Barcarena; and how CSR approaches intersected with these. In applying this methodology, research findings emerged through a consensus of voices over multiple field visits and interviews.

Over four field visits to Barcarena in 2015 and 2016 we conducted semi-structured interviews with approximately 100 respondents. These included current and former CSR staff with Hydro, employees at Alunorte who had worked under both Vale and Hydro, community leaders, local municipal politicians, academics, NGO leaders, and community residents. We also consulted key strategy documents related to company policies and procedures to CSR, community outreach documents, and reports from local NGOs. Purposive sampling identified managerial interviewees at Hydro in Norway and Brazil and expanded using snowball techniques. Local politicians were purposively selected based on relevant portfolios and engagement with local multistakeholder dialogue projects,Footnote35 as were NGOs that coordinated these dialogue efforts.

In selecting local residents, we applied a snowball sampling approach, with multiple visits to multiple field sites and communities in Barcarena. We also purposively sought to represent a cross-section age, gender and socio-economic status among the sample of local populations. All respondents are anonymised, and all communities remain non-specified other than being in the Barcarena municipality. Data were triangulated across respondents to understand the challenges related to civil society–company engagement, identify core aspects of CSR under Vale and Hydro, and identify relevant challenges and opportunities for future conflict resolution. Where they reflect representative views of populations interviewed, we use respondent quotations which elucidate the experiences, perceptions and concerns about business and political actions and impacts in the community, community-company relations and CSR strategy. Interviews were primarily conducted in Portuguese with a local gatekeeper, translated by authors and assistants to English and edited for clarity. Selected interviews with Hydro managers were conducted in English. We attach in an appendix our Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist, a standardised robustness assessment for qualitative research.Footnote36

We considered alternative explanations for our findings. First, conflicts might remain due to Hydro merely replicating approaches of Vale. Perusing annual reports, documents on Vale’s corporate citizenship, and triangulating across interviews, however, suggests that there is a clear difference in approach between companies and that the strategic intent behind CSR approaches differs significantly. Second, we considered whether the position of Hydro as a key economic and political actor saw other grievances directed at them that were not due to Hydro’s own actions. While clear that some grievances were voiced about the state and local government and other companies, the operations of Hydro were clearly identified as the primary concern in Barcarena.Footnote37 A final consideration is the issue of response bias, particularly related to social desirability bias and demand characteristics. As Hydro’s CSR approach is highly regarded internally, managers may be reticent to discuss flaws. However, we found managers open to discussing problematic aspects of Hydro’s approach. For local populations, respondents often repeated narratives of dissatisfaction for nearly all major stakeholders in Barcarena, and we did note instances of grievances that appeared exaggerated. Moreover, several members of civil society organisations were known (or came to be known) as having agendas or ‘axes to grind’. Counteracting this, as in all fieldwork, is challenging. We paid close attention to potential motivations underlying what was said, triangulated across multiple interviewees, and often across the same interviewee on multiple occasions. During fieldwork, we were also careful to not interpret interviews in light of the values or positions that we may have expected interviewees to hold – such as civil society being critical of the EI or CSR managers being overwhelmingly positive about their own activities. What emerged is a narrative that supports what we describe here in our findings that we believe accurately summarises managerial and civil society sentiment.

Social conflict and CSR in Barcarena

Vale: 1978–2011

The development agenda of the Brazilian government in the 1970s and 1980s linked rural areas to networks of global capital for the purposes of modernisation and development.Footnote38 Vale was a key actor in this agenda, and across the Brazilian Amazon, large (often extractive) corporations became influential economic and political actors. In Barcarena the growth of industrial activity led to a socio-spatial reordering of the municipality and a socio-economic dependence on large-scale industrial activity.Footnote39 Local institutional weakness and corruption eroded the agency of civil society,Footnote40 and when corporations failed to deliver the broader developmental benefits promisedFootnote41 socio-environmental conflicts proliferated.Footnote42

In Barcarena, Vale’s engagement with local communities was patriarchal, reflecting paternalistic modes of company–community relations of the time.Footnote43 Vale used a ‘company town’ model, developing planned facilities for workers and their families close to refineries at Villa dos Cubanos, leaving the rest of the municipality underdeveloped. Alongside the town with company-provisioned housing, roads, lighting, water and sanitation, informal communities sprung up to house those who arrived hoping to find work. Despite this inequality, Vale was generally viewed rather positively as they provided many services in the region in lieu of the local government. Reflective of Brazil’s history of philanthropic approaches to CSR, Vale’s paternalism was inherent in how the company cultivated goodwill – and soothed dissent – by intermittently supporting discretionary investments. Vale strategically used relatively small investments in social projects to engender support from communities to preserve their SLO and secure their operations. Close links were maintained with selected community leaders, and unions were financially supported by Vale to encourage a compliant workforce and minimise risks of worker strikes or walkouts.Footnote44

Over time Vale’s approach exacerbated inequality, weakened civil society and created dependence on private industry for local development, with the company becoming the de facto patron of the community. This ‘reinforc(ed) a cycle of dependency’ between the local community and industryFootnote45 and despite ‘criticisms of the industrial impacts, (citizens) found themselves entangled in an asymmetric relationship of power with the local ventures’.Footnote46 Focus group interviews with long-time community leaders reiterated that the town was largely beholden to the acts of Vale. Few benefits outside of discretionary projects trickled down to communities, and many residents moved to high-risk fenceline areas as a livelihood strategy, hoping to gain compensation in the event of industrial expansion.

An important juncture in company–community relations was the privatisation of Vale in 1997. This, and the subsequent purchase by Hydro of a minority ownership stake in Alunorte and Albras in 2001, saw a more conscious approach to CSR emerge. An organised, ‘military-like’ management structureFootnote47 was established, with Vale taking the position that local development was now the responsibility of the local government rather than the company. As a result, basic services which were previously provided or maintained by ‘public Vale’ were no longer supported by ‘private Vale’.Footnote48 While approaches to community development remained focused on discretionary, short term support, this evolved into an agenda of more formalised small-sale projects as revealed in the company’s Annual Reports and Sustainability Reports from the 2000s.Footnote49 While some programmes supported community education and small-scale manufacturing, other activities were simply framed as ‘investments’ such as paving roads, or building markets or fire stations. Despite this, Vale was no longer willing to play the role of community patron that it had previously assumed prior to the company’s privatisation.

This period saw tensions and conflicts between Vale and local communities intensify. Vale was seen as not delivering on their social development role the community had become accustomed to, and the selective disbursements Vale made became more contentious. Several interviewees perceived that community leaders were paid off to garner support for ValeFootnote50 – or to avoid social conflicts that could lead to plant shutdowns or disruptions to operations.Footnote51 Other authors have noted Vale as ‘extremely bureaucratic’, ‘slippery’, confrontational and hesitant to engage in dialogue where grievances emerged.Footnote52 While Vale’s mid-2000s annual reports note the company’s dialogue programmes with the local community, interviews suggest engagement was relatively shallow, poorly organised, irregular, and largely disinterested in reciprocal dialogue. One community leader claimed Vale ‘bought’ good relationships with some community leaders through favours, while they excluded leaders that were critical towards the company.Footnote53

The most incendiary conflicts related to a series of environmental accidents in the 2000sFootnote54 that have contributed to lasting environmental degradation and land and water contamination. Most notably, during unusually heavy rainfall in 2009, large quantities of Red Mud, a waste by product from the alumina refining process, spilled from tailings dams of Alunorte into the Murucupi River. Vale and now Hydro deny culpability for environmental damages and livelihood impacts, yet lawsuits and appeals have continued for almost a decade. In addition to legal proceedings, civil society has expressed their grievances though regular major road blockages and protests at plant gates, causing frequent and significant interruptions to logistics, supply and operations. Thus, despite the move towards a more modern CSR approach following Vale’s privatisation, deep-seated conflict lines over exclusion from benefits and environmental damages became profoundly ingrained in company–community relationships in Barcarena.

Hydro: 2011–

In this context of heightened grievances over underdevelopment and environmental damages, Hydro took ownership from Vale in 2011. Looking to mark itself anew, and in aiming to be a global leader in corporate citizenship standards for extractive firms, Hydro adopted a more explicit and progressive form of CSR compared with Vale. At the time of acquisition Hydro’s annual report stated:

As we integrate the new operations, we will also emphasize social responsibility, including working conditions, combating corruption and engaging with stakeholders as we do in our existing operations. Hydro will implement appropriate HSE (health, safety and environment) and CSR strategies reflecting our new, major presence in Brazil based on our core values reflected in The Hydro Way.Footnote55

Hydro sought to develop local legitimacy though community development and supporting dialogue initiatives. The firm engaged human rights organisations to assess their local operations, and criticisms and recommendations appear to have been internalised and incorporated into CSR practices.Footnote56 They also declared their long-term commitment to capacity building in Barcarena and sought to deepen ties with local stakeholders. Committing to a more regular and widespread programme of community visits and outreach than Vale, Hydro became the only industry member in Barcarena to voluntarily participate in the multistakeholder Intersectoral Dialogue Forum – arbitrated by national Brazilian NGO IEB and monitored by Norwegian NGO Norwegian Church Aid. The forum brought together civil society organisations, local government representatives and local Hydro management. Since commencing formally in 2014, key inputs have been made to the Urban Master Plan in Barcarena for zoning and land use; and advocated for local government transparency and responsible revenue use.Footnote57 Overall, the Forum succeeded in reducing the animosity and hostility towards Hydro among key civil society organisations and has created an environment of contentious yet co-operative dialogue that has had tangible inputs into development issues in Barcarena.

Through these activities Hydro tried to reframe itself as a more progressive and responsible corporate actor. Hydro CSR managers based in Brazil repeatedly pointed out that Hydro rejected the ‘philanthropic approach of Vale’ in Barcarena, claiming that ‘we have very different approaches’.Footnote58 While this ‘reframing’ led to awareness of Hydro as a new owner, our interviews suggest that little has changed in a meaningful way for residents and that many remain sceptical or outright critical of the company. Despite Hydro’s interest to deepen dialogue with communities, outreach strategies have underwhelmed. Canal Direito, Hydro’s community newsletter, for instance, is often not received or read; many are unaware of the Intersectoral Dialogue Forum or dismiss it after years of tokenistic consultation and community relations under Vale. One longtime resident of Barcarena said: ‘The companies come (out to the communities) and make promises in meetings. But nothing happens. (I’m) tired of listening to the bullshit and false promises […]’.Footnote59

While communication between Hydro and civil society representatives in the Forum have improved, Hydro’s activities show little to no positive short-term impact on the livelihoods of the community. Exacerbated by poor local government service delivery,Footnote60 Hydro’s elimination of discretionary (and most project based) funding was seen by many as an indication of the firm no longer ‘contributing’ to the community in the way that Vale did. This refrain was common across interviewees in the community. While Hydro initiated or extending focused social programme innovations (e.g. in education) and broader technological improvements in environmental safety, these assertions of good corporate citizen ship fall largely on deaf ears. Hydro’s CSR approach has faced challenges in scaling up positive developmental impacts in the short term; and is further hamstrung by the incapacity and lack of political vision of the local government to design policy to improve social development.Footnote61 Even those directly benefiting from employment, were at times critical. Plant workers disapproved of the newer restrictive corporate culture and perceived new processes as top-down and unnecessary and local management confirmed that Hydro struggled with introducing a new culture of transparency. Bluntly, as one resident summarised, ‘things are getting better, but things have not really gotten any better’.Footnote62

Most seriously, however, for social conflict and opposition are the legacies of environmental damages Hydro inherited from Vale, and how they intersect with other forms of political, economic and social exclusion in Barcarena under Vale’s stewardship. Hydro appears to have fundamentally misunderstood or underestimated the deep-rooted animosity among civil society towards the EI surrounding the degradation of the natural environment over the past four decades. The Red Mud spill in 2009 inflamed civil society grievances, particularly as both Vale and now Hydro denied their culpability, fighting thousands of cases against damages stemming from the incident. Hydro has itself responded by promoting their investments in new technologies that reduce the volume of red mud waste from refining – pushing a technocratically ‘green image’. Yet this has not resonated with the community, who remain highly sceptical given the history of industrial accidents, and conflicts have even been exacerbated by claims that Hydro’s new waste storage facilities are built on environmentally protected lands.Footnote63

Given this, strikes, plant shutdowns, road closures and other incidents have been regular occurrences over the past decade, often flaring up when news of legal, labour, or environmental issues emerge. Recently, grievances over Hydro’s lack of local hiring saw roads to plants blocked regularly during 2017.Footnote64 Legal action surrounding claims Hydro illegally built on environmentally protected lands were filed in December 2017, and coincided with some of the more serious protests of recent times.Footnote65 This came to the fore in February 2018, when heavy rains led to the flooding of Hydro’s Alunorte facility with untreated water used in refining operations released into and polluting local waterways. This confluence of inadequate operational oversight and an inability for Hydro to internalise and respond to local grievances related to environmental damages was inflammatory, culminating in volatile protests throughout 2018. Reflecting on the situation, Miklian et al. also note that: ‘in adopting conventional CSR strategies, (Hydro) reproduced a bias towards core business risks at the detriment of community relations, ruptures that later turned an environmental spill into a major public relations disaster’.Footnote66

These recent incidents show the fragility of states of ‘peace’ in light of intractable community conflicts. Yet even beyond conflicts related to grievances between civil society and the EI, Hydro is entangled in the broader dynamics of local conflict and violence. Barcarena has a homicide rate of 50 per 100,000, with violence and insecurity affecting worker safety, governance capacity and Hydro’s physical assets. While some of its social programmes – including its flagship educational and conflict mediation programme among youth in schools that sends a football team to compete in the Norway Cup youth football competition – address the issues violence in the community at the margins, Hydro’s CSR activities appear to have limited direct focus on the broader context of violence in Barcarena.Footnote67

Moreover, these narrow, targeted attempts to deliver particular types of social impact are unlikely to be successful in overcoming the breadth of community grievances and the context of violence and conflict Hydro operates in. On one hand, Hydro’s focus on targeting social programmes while supporting a long-term approach to the development of local political and civil society capacity resonates with the notion that companies focus on ‘a different kind of social investment […] to reinforce the social and political functions that are missing or compromised in the fragile context of which the company is part’.Footnote68 Yet this has proved insufficient to insulate the company from conflicts and promote peace in the local community. Hydro appears not to have fully understood the legacies of territorial grievances in Barcarena, where companies today are linked with – and deemed answerable for – the histories and memories of political, economic or environmental exploitation in the region that can precede the company itself. In buying Vale, Hydro also bought the history of the company, and the good- and ill-will that came with it. Ultimately, Hydro’s CSR approach of prioritising operational risk over deeper community engagement did not adequately understand how local histories could affect operations; nor has it shaped a shared vision of the future with the community of Barcarena that may have addressed these grievances and addressed conflicts.

Discussion

Over the past four decades, conflict has defined the relationships between the community of Barcarena and EI companies Vale and Hydro. Initially perceived as a positive developmental influence, Vale’s esteem was eroded as local populations saw little of the economic gains from industry, and land and environmental disputes became central and communities were excluded from consultation. These negative perceptions of the company and industry followed over to Hydro when it took ownership of Alunorte in 2011, despite the company having aimed to differentiate itself from Vale and build value for both themselves and local communities. This shift from Vale to Hydro’s approaches seems to reflect the move from CSR to CSR 2.0 where ‘paternalistic relationships between companies and the community based on philanthropy will give way to more equal partnerships’.Footnote69 Hydro notes that they:

strive to ‘mak(e) a difference by creating fundamental value – whether financial, environmental or societal’, and acknowledge that ‘society is made up of our customers, partners, and the communities we operate in. Our commercial interests and our social responsibilities are one: business and societal needs are inseparable.Footnote70

Yet, positive change has yet to fully emerge. Hydro’s relationship with the community is little improved despite conscious attempts at dialogue. The company also still faces many of the same challenges that beset ValeFootnote71 and most seriously has not adequately addressed – and even exacerbated – legacies of environmental grievances. Thus, despite their desire to ‘do good’, Hydro have prima facie failed in creating shared value for both company and community. This can be seen as a disconnect between the aggregate-level conceptualisation of ‘good corporate citizenship’ and the local level implementation of such policies. At the conceptual level, for instance, Hydro’s innovations in environmentally-safe storage of refining by-products align with goals of responsible environmental stewardship. Investing in community dialogue, supporting local political capacity building, and engaging in participatory planning to improve socio-structural conditions are all – on paper – credible attempts to empower the society in which Hydro operates.

Yet this case shows that such activities will count for little if they are not implemented in a way that resonates locally with communities. In seeking ‘shared value’ Hydro’s CSR efforts in Barcarena appear ahistorical in their narrow, forward-looking engagement with the causes of intractable conflict and community grievances. Environmental pollution is grave despite technological investments. Moreover, there has been little immediate or meaningful benefit seen by most of the local population. Basic services remain dire despite Hydro’s support for social projects, and employment opportunities remain skewed to skilled labour from elsewhere in Brazil. As such, Hydro’s goals of legitimacy and shared value creation have not come to fruition despite a more explicitFootnote72 CSR platform than Vale. As one CSR manager admitted, Hydro missed an opportunity to more compellingly reiterate the differences in corporate culture and social responsibility between itself and Vale when it took ownership.Footnote73

This is not Hydro’s fault entirely. Governance deficits limiting service delivery contribute to conflicts and negatively impact Hydro’s operating environment. Yet central to Hydro’s challenges are its struggles with legacy issues inherited from ValeFootnote74 and an arguably naïve assumption that ‘good CSR’ could overcome legacies of ‘bad practice’. This speaks to the fact that Hydro’s focus on long-term structural change and capacity building gives little tangible development in the near term, while simultaneously offering little in terms of broader meaningful changes to operations in an environmentally damaging industry.

In understanding this, Carson et al. note how Hydro’s broader corporate focus on ‘building communities might be seen as symptomatic of CSR as a (re)legitimizing strategy […] (though) it might be argued that this explication of values is a matter of “window dressing” more than of actual changes in corporate practice’.Footnote75 In Barcarena this rings true, with Hydro’s focus on long term capacity building and dialogue not requiring meaningful changes to broader operational practices, nor a tangible engagement with the legacies of the industry prior to their arrival. Similarly, many of the company’s actions – such as the promotion of technological solutions in their operations to promote environmental responsibility – may be seen more as an attempt to position themselves as ‘globally’ legitimate. Locally, however, this was intrinsically undermined by their firm stance on their own (lack of) environmental responsibility.

This underscores the challenges of applying what might be global models of CSR to local contexts in developing countries,Footnote76 or to areas of limited state presence or ‘statehood’.Footnote77 Emerging approaches to CSR tailored to fragile or developing contexts may be more helpful. Visser suggests CSR strategies should make clear economic contributions and account for ‘dilemmas or trade-offs’ such as economic development versus environmental protection.Footnote78 Proponents of inclusive business models are also critical of CSR that fails to account for livelihood impacts and environmental footprint of their activities, advocating instead for communities as partners rather than beneficiaries.Footnote79 Others see potential in Hybridised CSR approaches, where global standards of socially responsible corporate practice are modified based on local context.Footnote80

Moreover, beyond CSR as simply building a SLO or as risk management, businesses should recognise how their actions can shape cultures of peace and conflict more directly.Footnote81 Ultimately, addressing conflict is good for both firms and civil society, and businesses can work towards doing so by implementing conflict sensitive engagement with communities;Footnote82 and incrementally build towards supporting societies even outside of express conflict situations.Footnote83 Hydro’s experience suggests this can be challenging, as outside of the Intersectoral Dialogue Forum, Hydro has been largely unable to reduce social conflicts directed at them or the industry, nor support reduction of violence and conflict more broadly. This reiterates that while CSR efforts may reduce EI related conflicts in the short term, effects can be ‘varied and locally-contingent’, and CSR itself may itself even be ‘deeply embedded in legitimising the violence of capitalism, including the slow violence from degrading local environments’.Footnote84

Thus, more than simply focusing on shared value and long-term investments, this case reiterates that companies need to understand conflict sensitivity more concertedly as a core aspect of their CSR efforts.Footnote85 This requires asking tough questions of businesses. In many cases, key aspects of operations may be fundamental to exacerbating conflicts and making piecemeal efforts at the margins may be ineffective at addressing long-standing grievances. The findings here also suggest the need to attend to the temporal dimension of corporate citizenship as related to company–community conflicts in the EI. Hydro’s struggles emphasise that gaining community acceptance and SLO is a continual process of negotiation,Footnote86 with legitimacy supported or eroded by the ‘cumulative social and environmental impacts’ involving ‘multiple companies, projects, components and activities’.Footnote87 In insufficiently understanding and responding to the past, Hydro has undermined its own prospective CSR activities, and seen local conflicts exacerbate. This underlines the need to critically consider the nature of current CSR and CSV approaches which largely focus on forward looking value creation for companies and communities. As this case shows, companies who enter areas of operation must also consider the inherited responsibilities that come with the past and make engaging with the histories of a region central to how they move forward if they are to address conflicts and grievances and deliver on promises of shared value creation.

Conclusion

Hydro’s experience in Barcarena shows that a forward-looking CSR and heavy commitment of financial resources will not necessarily address conflicts related to extraction in areas of operation. To have real positive impact for companies and communities, CSR and dialogue activities must move from merely discussing grievances to designing a shared vision of a common futureFootnote88 – and act on these to deliver both short-term and long-term benefits to local populations. Moreover, if companies do not acknowledge and engage with legacies of past grievances, their ability to be seen as socially, economically and environmentally legitimate by the local community will be challenged. And this in turn undermines efforts to support peaceful societies in contexts of underlying social and violent conflict.

Finally, this case shows that grievances related to social conflicts between local communities and extractive firms can be inherently spatial and temporal in nature – deeply rooted in a territory and connected over time. It would be wise for firms’ CSR approaches to understand these dynamics more thoroughly. While forward-looking approaches are necessary to create shared value, these can be weakened where companies do not account for or are not responsive to the past. Serious engagement with social and environmental impacts in the past, present, and future and the creation of local economic benefits in the short and long term are integral for EI companies to address social conflicts and support peaceful societies where they operate.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Giselle Hoover Silveira for in-field assistance and knowledgeable insights. The authors also thank Professor Deanna Kemp and researchers at the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining at the University of Queensland for discussions that assisted in the development of this article. A word of thanks also goes to the guest editors of this issue and two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments. This work was supported by the Latin America section of the Utenriksdepartement (Norwegian Ministry for Foreign Affairs) [grant number BRA-14/0027] and Norges Forskningsråd [Research Council of Norway] (grant number 231757/F10).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kristian Hoelscher

Kristian Hoelscher is a senior researcher at PRIO. His research examines conflict and development with focus on themes of urbanisation, natural resources, innovation and the private sector.

Siri Aas Rustad

Siri Aas Rustad is a senior researcher at PRIO. Her research examines how conflict relates to natural resources, the role of the extractive industry development aid, health and education.

Notes

1. Oetzel and Miklian, ‘Multinational Enterprises, Risk Management’.

2. Lujala et al., ‘Engines for Peace?’.

3. Spence, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in the Oil and Gas Industry’.

4. Franks et al., ‘The Cumulative Dimensions of Impact’, 7576.

5. Virah-Sawmy, ‘Growing Inclusive Business Models in the Extractive Industries’.

6. See Dare et al., ‘Community Engagement and Social Licence to Operate’.

7. Visser, The Age of Responsibility.

8. Porter and Kramer, ‘The Big Idea’.

9. This has been further exacerbated by the release of chemical tailings water in to local rivers in February 2018, leaving Hydro mired in an ongoing operational crisis.

10. Ballard and Banks, ‘Resource Wars’; Jenkins, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and the Mining Industry’.

11. Such as the protracted insurgency in the Niger Delta in Nigeria. See for example Obi and Rustad, Oil and Insurgency in the Niger Delta.

12. Conde, ‘Resistance to Mining’; Andrews et al., The Rise in Conflict Associated with Mining Operations; Calvano, ‘Multinational Corporations and Local Communities’.

13. McKenna, Corporate Social Responsibility and Natural Resource Conflict; Jenkins ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and the Mining Industry’; Andrews et al., The Rise in Conflict Associated with Mining Operations; Holden and Jacobson, ‘Ecclesial Opposition to Nonferrous Mining in Guatemala’; Ballard and Banks, ‘Resource Wars’; Ponce and McClintock, ‘The Explosive Combination of Inefficient Local Bureaucracies and Mining Production’; Mensah and Okyere, ‘Mining, Environment and Community Conflicts’; Conde and Le Billon, ‘Why Do Some Communities Resist Mining projects?'.

14. Perrault and Valdivia, Hydrocarbons, Popular Protest and National Imaginaries; Kohl and Farthing, ‘Material Constraints to Popular Imaginaries’.

15. Conde, ‘Resistance to Mining’.

16. Franks et al., ‘Conflict Translates Environmental and Social Risk’.

17. Ibid.; Bebbington et al., ‘Mining and Social Movements’.

18. Ruggie, ‘Protect, Respect, Remedy’; Newell and Frynas, ‘Beyond CSR?’.

19. Humphreys, ‘A Business Perspective on Community Relations in Mining’; Kapelus, ‘Mining, Corporate Social Responsibility and the Community’; Reed, ‘Resource Extraction Industries in Developing Countries’; Jenkins, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and the Mining Industry’; Bebbington et al., ‘Contention and Ambiguity’.

20. Hamann, ‘Mining Companies’ Role in Sustainable Development’; Esteves, ‘Mining and Social Development’; ICMM, Approaches to Understanding Development Outcomes from Mining; Parra and Franks, ‘Monitoring Social Progress in Mining Zones’.

21. Prandi and Lozano, CSR in Conflict and Post-Conflict Environments; Kytle and Ruggie, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility as Risk Management’.

22. Zandvliet and Anderson, Getting it Right.

23. Porter and Kramer, ‘The Big Idea’.

24. Moffat and Zhang, ‘The Paths to Social Licence to Operate’.

25. Dare et al., ‘Community Engagement and Social Licence to Operate’; Thomson and Boutilier, ‘The Social Licence to Operate’; Owen and Kemp, ‘Social licence and Mining’; Prno and Slocombe, ‘Exploring the Origins of “Social License to Operate” in the Mining Sector’.

26. McNab et al., Beyond Voluntarism; Kemp, ‘Community Relations and Mining’; Martinez and Franks, ‘Does Mining Company-Sponsored Community Development Influence Social Licence to Operate?’.

27. Berger et al., ‘Mainstreaming Corporate Social Responsibility’; Carroll and Shabana, ‘The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility’.

28. Matten and Moon, ‘“Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR’.

29. Frynas, The False Developmental Promise of Corporate Social Responsibility; Gilberthorpe and Banks, ‘Development on Whose Terms’; Hilson, ‘Championing the Rhetoric?’.

30. Franks et al., ‘The Cumulative Dimensions of Impact’.

31. Kemp and Owen, ‘Community Relations and Mining’.

32. Miklian, ‘Mapping Business-Peace Interactions’.

33. Crane et al., ‘Quants and Poets’.

34. Bass and Milosovic, ‘The Ethnographic Method in CSR Research’.

35. Rustad and Hoelscher, ‘Supporting Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue in Barcarena’.

36. Tong et al., ‘Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research’.

37. This position is also evidenced by the fiercely critical response in the community over the environmental accident at Hydro’s Alunorte complex in February 2018.

38. Evans, Dependent Development.

39. da Silva et al., ‘Territorial Planning in the Amazonian Mining Towns of the State of Para’.

40. Nahum, ‘The Modern Territorial Reordering of Barcarena’.

41. Coelho et al., ‘Políticas públicas, corredores de exportaçãos’.

42. Hoschtelter and Keck, Greening Brazil; Cornejo et al., ‘Promoting Social Dialogue in the Mining Sector in the State of Pará’.

43. Cornejo et al., ‘Promoting Social Dialogue in the Mining Sector in the State of Pará’.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid., 23.

46. Moreira and Castro, ‘Perspectives, Impacts and Perceptions’, 1.

47. Interview, Alunorte employee, April 2016.

48. Interview, civil society leader, April 2016.

50. Interviews, April 2016. One noted that ‘civil society leaders who were unemployed were paid by Vale to tell them what other civil society leaders talked about’.

51. Several interviews, Barcarena community leaders and residents, April 2016.

52. Wachelke, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Local Communities as Stakeholders’.

53. Interview, April 2016.

54. IEB, Posicionamento da Rede da Sociedade Civil Pró-Fórum em Barcarena.

55. Hydro, Hydro Annual Report 2010.

56. Hydro engaged the Danish Institute for Human Rights to evaluate their operations in 2014 (Danish Institute for Human Rights, Summary Report). Mild criticisms regarding grievance mechanisms and community engagement raised in the report appear to have been acted on since and were discussed during interviews with Hydro Brazil CSR staff in 2015 and 2016.

57. Rustad and Hoelscher, ‘Supporting Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue in Barcarena’.

58. Interview, Hydro CSR Managers, April 2016.

59. Interview, community resident, April 2016.

60. A CSR manager stated that ‘there are people coming to Hydro all the time to ask for things: food, jobs, hospitals, medicine. Because the local government is weak, people come to the companies (instead)’. Interview, April 2016.

61. Ganson, ‘Companies in Fragile Contexts’. Cumulative information gathered in our own interviews confirm this.

62. Interview, April 2016.

63. Noted in several interviews, 2015 and 2016.

65. ‘População protesta contra danos causados pela Hydro e interdita acesso a Barcarena’, 14 December 2017. Available at: https://www.diarioonline.com.br/noticias/para/noticia-472843-.html.

66. Miklian et al., ‘Business and Peacebuilding’, 17.

67. See also Ganson, ‘Companies in Fragile Contexts’, on the how Hydro is affected by the dynamics of violence in Barcarena and Hydro’s responses.

68. Ganson, ‘Companies in Fragile Contexts’, 1.

69. Visser, The Age of Responsibility.

71. Similar observations are made by Ganson, ‘Companies in Fragile Contexts’.

72. See Matten and Moon, ‘“Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR’, on implicit and explicit CSR.

73. Interview, senior Hydro CSR manager, November 2015.

74. Danish Institute for Human Rights, Summary Report.

75. Carson et al., ‘From Implicit to Explicit CSR in a Scandinavian Context’.

76. Jamali and Mirshak, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)’; Jamali et al., CSR Logics in Developing Countries.

77. Azizi and Jamali, ‘CSR in Afghanistan’.

78. Visser, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries’.

79. Virah-Swamy, Growing Inclusive Business Models in the Extractive Industries.

80. Jamali and Karam, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries’.

81. Miklian, ‘Mapping Business-Peace Interactions’; Oetzel and Miklian, ‘Multinational Enterprises, Risk Management’; Ford, Regulating Business for Peace; Oh and Oetzel, ‘Once Bitten Twice Shy?’.

82. Haski-Leventhal, ‘From CSR and CSV to Business and Peace’.

83. Fort, ‘Gentle Commerce’.

84. Gamu and Dauvergne, ‘The Slow Violence of Corporate Social Responsibility’, 1.

85. For recent examples of conflict sensitive business practice, see Miklian et al., ‘Business and Peacebuilding’; Ganson et al., ‘Capacities and Limitations of Private Sector Peacebuilding’; Orsini and Cleland, Human Rights Due Diligence in Conflict Affected Settings.

86. Dare et al., ‘Community Engagement and Social Licence to Operate’.

87. Martinez and Franks, ‘Does Mining Company-Sponsored Community Development Influence Social Licence to Operate?’, 297.

88. Franks, ‘Avoiding Mine-Community Conflict’.

References

- Andrews, T., B. Elizalde, P. Le Billon, C.H. Oh, D. Reyes and I. Thomson, 2017. The Rise in Conflict Associated with Mining Operations: What Lies Beneath? CIRDI, Vancouver.

- Azizi, S. and D. Jamali, 2016. ‘CSR in Afghanistan: A Global CSR Agenda in Areas of Limited Statehood’. South Asian Journal of Global Business Research 5(2), 165–189.

- Ballard, C. and G. Banks, 2003. ‘Resource Wars: The Anthropology of Mining’. Annual Review of Anthropology 32, 287–313.

- Bass, A.E. and I. Milosevic, 2018. ‘The Ethnographic Method in CSR Research: The Role and Importance of Methodological Fit’. Business & Society 57, 174–215.

- Bebbington, A., D.H. Bebbington, J. Bury, J. Lingan, J.P. Muñoz and M. Scurrah, 2008. ‘Mining and Social Movements: Struggles over Livelihood and Rural Territorial Development in the Andes’. World Development 36(12), 2888–2905.

- Bebbington, A., L. Hinojosa, D.H. Bebbington, M.L.M.L. Burneo and X. Warnaars, 2008. ‘Contention and Ambiguity: Mining and the Possibilities of Development’. Development and Change 39(6), 887–914.

- Berger, I.E., P. Cunningham and M.E. Drumwright, 2007. ‘Mainstreaming Corporate Social Responsibility: Developing Markets for Virtue’. California Management Review 49, 132–157.

- Bunker, S.G., 1984. ‘Modes of Extraction, Unequal Exchange, and the Progressive Underdevelopment of an Extreme Periphery: The Brazilian Amazon, 1600–1980’. American Journal of Sociology 89(5), 1017–1064.

- Calvano, L., 2008. ‘Multinational Corporations and Local Communities: A Critical Analysis of Conflict’. Journal of Business Ethics 82(4), 793–805.

- Carroll, A.B. and K.M. Shabana, 2010. ‘The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice’. International Journal of Management Reviews 12(1), 85–105.

- Carson, S.G., Ø. Hagen and S.P. Sethi, 2015. ‘From Implicit to Explicit CSR in a Scandinavian Context: The Cases of HÅG and Hydro’. Journal of Business Ethics 127(1), 17–31.

- Coelho, M., M. Monteiro and I. Santos, 2009. ‘Políticas públicas, corredores de exportaçáo, modernizaçáo portuária, industrializaçáo e impactos territoriais e ambientais no município de Barcarena, Pará [Public Policies, Export Corridors, Port Modernisation, Industrialisation and Territorial and Environmental Impacts in the Municipality of Barcarena, Pará]’. Novos Cadernos NAEA 11(1), 141–178.

- Conde, M., 2017. ‘Resistance to Mining. A Review’. Ecological Economics 132, 80–90.

- Conde, M. and P. Le Billon, 2017. ‘Why Do Some Communities Resist Mining Projects while Others Do Not?’ The Extractive Industries and Society 4(3), 681–697.

- Cornejo, N., C. Kells, T.O. de Zuniga, S. Roen and B. Thompson, 2010. ‘Promoting Social Dialogue in the Mining Sector in the State of Pará, Brazil’. Consilience, the Journal of Sustainable Development 3(1), 1–67.

- Crane, A., I. Henriques and B.W. Husted, 2018. ‘Quants and Poets: Advancing Methods and Methodologies in Business and Society Research’. Business & Society 57(1), 3–25.

- Da Silva, J.M.P., C.N. Da Silva, C.A.N. Chagas and G.R.N. Medeiros, 2014. ‘Territorial Planning in the Amazonian Mining Towns of the State of Para (Brazil)’. Modern Economy 5, 1053–1063.

- Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2014. Summary Report – High Level Human Rights Observations: Hydro CSR Assessment Brazil 2014. DIHR, Copenhagen.

- Dare, M., J. Schirmer and F. Vanclay, 2014. ‘Community Engagement and Social Licence to Operate’. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32(3), 188–197.

- Davis, R. and D.M. Franks, 2014. ‘Costs of Company-Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector’. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Report, no. 66. Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA.

- Esteves, A., 2008. ‘Mining and Social Development: Refocusing Community Investment Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis’. Resources Policy 33(1), 39–47.

- Evans, P., 1979. Dependent Development. The Alliance of Multinational, Local and State Capital in Brazil. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Ford, J., 2015. Regulating Business for Peace. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Fort, T., 2014. ‘Gentle Commerce’. Business, Peace and Sustainable Development 4, 107–112.

- Franks, D., 2009. ‘Avoiding Mine-Community Conflict: From Dialogue to Shared Futures’. Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Environmental Issues in the Mining Industry, Santiago.

- Franks, D. and T. Cohen, 2012. ‘Social Licence in Design: Constructive Technology Assessment within a Mineral Research and Development Institution’. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79, 1229–1240.

- Franks, D.M., D. Brereton and C.J. Moran, 2013. ‘The Cumulative Dimensions of Impact in Resource Regions’. Resources Policy 38(4), 640–647.

- Franks, D.M., R. Davis, A.J. Bebbington, S.H. Ali, D. Kemp and M. Scurrah, 2014. ‘Conflict Translates Environmental and Social Risk into Business Costs’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(21), 7576–7581.

- Frynas, J.G., 2005. ‘The False Developmental Promise of Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Multinational Oil Companies’. International Affairs 81, 581–598.

- Gamu, J.K. and P. Dauvergne, 2018. ‘The Slow Violence of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Case of Mining in Peru’. Third World Quarterly 39(5), 959–975.

- Ganson, B., 2018. ‘Companies in Fragile Contexts: Redefining Social Investment’. Africa Centre for Dispute Settlement Working paper. Africa Centre for Dispute Settlement, Cape Town.

- Ganson, B., B. Miller, S. Cechvala and J. Miklian, 2018. ‘Capacities and Limitations of Private Sector Peacebuilding’. CDA Report. CDA Collaborative Learning, Cambridge, MA.

- Gifford, B., A. Kestler and S. Anand, 2010. ‘Building Local Legitimacy into Corporate Social Responsibility: Gold Mining Firms in Developing Nations’. Journal of World Business 45(3), 304–311.

- Gilberthorpe, E. and G. Banks, 2012. ‘Development on Whose Terms?: CSR Discourse and Social Realities in Papua New Guinea’s Extractive Industries Sector’. Resources Policy 37, 185–193.

- Hamann, R., 2003. ‘Mining Companies’ Role in Sustainable Development: The “Why” and “How” of Corporate Social Responsibility from a Business Perspective’. Development Southern Africa 20(2), 237–254.

- Harvey, B., 2014. ‘Social Development Will Not Deliver Social Licence to Operate for the Extractive Sector’. The Extractive Industries and Society 1(1), 7–11.

- Haski-Leventhal, D., 2014. ‘From CSR and CSV to Business and Peace’. Business, Peace and Sustainable Development 4, 3–5.

- Hilson, G., 2006. ‘Championing the Rhetoric? “Corporate Social Responsibility” in Ghana’s Mining Sector’. Greener Management International 53, 43–56.

- Hochstetler, K. and M. Keck, 2007. Greening Brazil: Environmental Activism in State and Society. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

- Holden, W.N. and R.D. Jacobson, 2009. ‘Ecclesial Opposition to Nonferrous Mining in Guatemala: Neoliberalism Meets the Church of the Poor in a Shattered Society’. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien 53(2), 145–164.

- Humphreys, D., 2000. ‘A Business Perspective on Community Relations in Mining’. Resources Policy 26(3), 127–131.

- Hydro, 2011. Hydro Annual Report 2010. Available at: https://www.hydro.com/globalassets/1-english/investor-relations/annual-report/2010/downloads/annual-report-2010.pdf [Accessed 3 January 2019].

- Instituto Internacional de Educa ção do Brasil (IEB), 2012. Posicionamento da Rede da Sociedade Civil Pró-Fórum em Barcarena: Por uma Barcarena justa, democrática e sustentável. [Position of the Pro-Forum Civil Society Network in Barcarena: For a Just, Democratic and Sustainable Barcarena]. Instituto Internacional de Educa ção do Brasil (IEB), Belém.

- International Council on Mining and Mineral (ICMM), 2013. Approaches to Understanding Development Outcomes from Mining. ICMM, Canberra.

- Jamali, D. and C. Karam, 2018. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries as an Emerging Field of Study’. International Journal of Management Reviews 20(1), 32–61.

- Jamali, D., C. Karam, J. Yin and V. Soundararajan, 2017. ‘CSR Logics in Developing Countries: Translation, Adaptation and Stalled Development’. Journal of World Business 52(3), 343–359.

- Jamali, D. and R. Mirshak, 2007. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and Practice in a Developing Country Context’. Journal of Business Ethics 72, 243–262.

- Jenkins, H., 2004. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and the Mining Industry: Conflicts and Constructs’. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 11, 23–34.

- Kapelus, P., 2002. ‘Mining, Corporate Social Responsibility and the Community’. Journal of Business Ethics 39(3), 275–296.

- Kemp, D., 2009. ‘Mining and Community Development: Problems and Possibilities of Local-Level Practice’. Community Development Journal 45(2), 198–218.

- Kemp, D. and J.R. Owen, 2013. ‘Community Relations and Mining: Core to Business but Not “Core Busines”’. Resources Policy 38, 523–531.

- Kohl, B. and L. Farthing, 2012. ‘Material Constraints to Popular Imaginaries: The Extractive Economy and Resource Nationalism in Bolivia’. Political Geography 31(4), 225–235.

- Kytle, B. and J. Ruggi, 2005. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility as Risk Management: A Model for Multinationals’. Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper, no. 10. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Lujala, P., S.A. Rustad and S. Kettenmann, 2016. ‘Engines for Peace? Extractive Industries, Host Countries, and the International Community in Post-Conflict Peacebuilding’. Natural Resources 7, 239—250.

- Martinez, C. and D.M. Franks, 2014. ‘Does Mining Company-Sponsored Community Development Influence Social Licence to Operate? Evidence from Private and State-Owned Companies in Chile’. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32(4), 294–303.

- Matten, D. and J. Moon, 2008. ‘“Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for A Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility’. Academy of Management Review 33(2), 404–424.

- McKenna, K., 2016. Corporate Social Responsibility and Natural Resource Conflict. Routledge, London.

- McNab, K., J. Keenan, D. Bereton, J. Kim, R. Kunanayagam and T. Blathwayt, 2012. Beyond Voluntarism: The Changing Role of Corporate Social Investment in the Extractive Sector. Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- Mensah, S.O. and S.A. Okyere, 2014. ‘Mining, Environment and Community Conflicts: A Study of Company-Community Conflicts over Gold Mining in the Obuasi Municipality of Ghana’. Journal of Sustainable Development Studies 5(1), 64–99.

- Miklian, J., 2018. ‘Mapping Business-Peace Interactions: Five Assertions for How Businesses Create Peace, Business’. Peace and Sustainable Development 10(1), 1–19.

- Miklian, J., P. Schouten, C. Horst and Ø. Rolandsen, 2018. ‘Business and Peacebuilding: Seven Ways to Maximize Positive Impact’. Peace Research Institute Oslo Report. PRIO, Oslo.

- Moffat, K. and A. Zhang, 2014. ‘The Paths to Social Licence to Operate: An Integrative Model Explaining Community Acceptance of Mining’. Resources Policy 39, 61–70.

- Moreira, B. and R. Castro, 2013. ‘Perspectives, Impacts and Perceptions: The Influence of the Aluminum Industry in Barcarena’. Paper presented at the XLVIII CLADEA meeting, Rio de Janeiro, 20–22 October.

- Nahum, J.S., 2017. ‘The Modern Territorial Reordering of Barcarena’. In Modernization and Political Actions in the Brazilian Amazon, ed. J.S. Nahum. Springer Briefs in Latin American Studies. Springer, Cham.

- Newell, P. and J.G. Frynas, 2007. ‘Beyond CSR? Business, Poverty and Social Justice: An Introduction’. Third World Quarterly 28(4), 669–681.

- Obi, C.I. and S.A. Rustad (eds.), 2011. Oil and Insurgency in the Niger Delta: Managing the Complex Politics of Petro-Violence. Zed Books, London.

- Oetzel, J. and J. Miklian, 2017. ‘Multinational Enterprises, Risk Management, and the Business and Economics of Peace’. Multinational Business Review 25(4), 270–286.

- Oh, C.H. and J. Oetzel, 2017. ‘Once Bitten Twice Shy? Experience Managing Violent Conflict Risk and MNC Subsidiary-Level Investment and Expansion’. Strategic Management Journal 38(3), 714–731.

- Orsini, Y. and R. Cleland, 2018. Human Rights Due Diligence in Conflict Affected Settings: Guidance for Extractives Industries. International Alert, London.

- Owen, J.R. and D. Kemp, 2013. ‘Social Licence and Mining: A Critical Perspective’. Resources Policy 38(1), 29–35.

- Parra, C. and D. Franks, 2011. ‘Monitoring Social Progress in Mining Zones – The Case of Antofagasta and Tarapaca, Chile’. In Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Social Responsibility in Mining, eds. D. Brereton, D. Pesce and X. Abogabir, Santiago (Chile), 19–21 October.

- Perreault, T. and G. Valdivia, 2010. ‘Hydrocarbons, Popular Protest and National Imaginaries: Ecuador and Bolivia in Comparative Context’. Geoforum 41(5), 689–699.

- Ponce, A.F. and C. McClintock, 2014. ‘The Explosive Combination of Inefficient Local Bureaucracies and Mining Production: Evidence from Localized Societal Protests in Peru’. Latin American Politics and Society 56(3), 118–140.

- Porter, M.E. and M.R. Kramer, 2011. ‘The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value’. Harvard Business Review 89(1), 2–17.

- Prandi, M. and J.M. Lozano (eds.), 2011. CSR in Conflict and Post-Conflict Environments: From Risk Management to Value Creation. Institute for Cultural Innovation and Escola de Cultura de Pau, Barcelona.

- Prno, J. and D.S. Slocombe, 2012. ‘Exploring the Origins of “Social License to Operate” in the Mining Sector: Perspectives from Governance and Sustainability Theories’. Resources Policy 37(3), 346–357.

- Reed, D., 2002. ‘Resource Extraction Industries in Developing Countries’. Journal of Business Ethics 39, 199–226.

- Ruggie, J., 2008, ‘Protect, Respect, Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights’. Human Rights Council of the United Nations. UN Doc. A/HRC/8/5.

- Rustad, S.A. and K. Hoelscher, 2016. ‘Supporting Multi-Stakeholder Dialogue in Barcarena, Brazil’. PRIO Policy Brief, no. 26. PRIO, Oslo.

- Spence, D., 2011. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in the Oil and Gas Industry: The Importance of Reputational Risk’. Chicago-Kent Law Review 86(1), 59–86.

- Thomson, I. and R. Boutilier, 2011. ‘The Social Licence to Operate’. In SME Mining Engineering Handbook, ed. P. Darling. Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration, Colorado, 1779–1796.

- Tong, A., P. Sainsbury and J. Craig, 2007. ‘Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups’. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19(6), 349–357.

- Virah-Sawmy, M., 2015. ‘Growing Inclusive Business Models in the Extractive Industries: Demonstrating a Smart Concept to Scale up Positive Social Impacts’. The Extractive Industries and Society 2(4), 676–679.

- Visser, W., 2008. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries’. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, eds A. Crane, A. McWilliams and J. Moon. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Visser, W., 2011. The Age of Responsibility: CSR 2.0 And the New DNA of Business. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

- Wachelke, M., 2015. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Local Communities as Stakeholders – A Case Study from Barcarena, in the Brazilian Amazon’. MA diss., Unversity of Oslo.

- Zandvliet, L. and M.B. Anderson, 2009. Getting It Right: Making Corporate–Community Relations Work. Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield.

Appendix

Table A1. COREQ framework assessment.