ABSTRACT

When #MeToo reached Sweden in the fall of 2017, it gave rise to nearly 80 industry-specific petitions that demanded a stop to sexual misconduct in the workplace, some with their own hashtags. This article examines the discourse of #MeToo on Twitter in Sweden in relation to these petition hashtags. Focusing on how #MeToo, petition hashtags, and other hashtags are co-articulated in Tweets, it maps the emergent network of hashtags using SNA and explores the resulting interpretative frames using discourse analysis. By co-articulating the MeToo and petition hashtags with hashtags related to Swedish politics and feminism, and by utilising the @-mention function to call out responsible politicians and industry executives, Twitter users extended the initial #MeToo frame beyond individualised problems and solutions common in connective action networks. We suggest that Twitter users utilise platform affordances to perform framing work in relation to political hashtags, not unlike framing work performed in traditional social movements.

Introduction

When #MeToo reached Sweden, it gave rise to nearly 80 industry-specific petitions signed by thousands of women, that demanded an end to the universal problem of sexual violence in the workplace (Karin Hansson Citation2020). While some Swedish social media posts under #MeToo, and much of the Swedish media coverage, focused on individual cases and named perpetrators, the petitions and the related media attention framed sexual harassment and assault as a structural rather than an individual problem (Tina Askanius and Jannie Møller Hartley Citation2019; Hansson Citation2020). The particularities and wide dispersion of #MeToo in Sweden are described as unique by women’s rights experts, researchers and politicians, citing explanations such as the country’s relatively high level of gender equality, widespread feminist self-identification among officials and political parties, and a longstanding tradition of feminist organising (Andrea Booth and Kelsey Munro Citation2017; Ester Pollack Citation2019; Kajsa Stål, Magnus Abrahamsson, and Maria Höglund Citation2021).

Feminist hashtags are used to shed light on the widespread problem of sexual assault and gender-based violence by linking together personal experiences, transforming them into collective stories (Tanya Serisier Citation2018). In this study, we understand #MeToo as an expression of networked connective action. Connective action networks emerge around so called “personal action frames,” individually expressive action frames that are inclusive of personal reasons for demanding change or speaking out about a problem and doesn’t require the adoption of a collective identity (Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg Citation2013).

Through the personal action frame of speaking out about experiences of sexual violence to shed light on a widespread problem, #MeToo dispersed globally. However, #MeToo also gave rise to the sector-specific petitions for change in Sweden, many with their own unique hashtag for social media dispersion. As these petitions addressed structural issues like workplace norms and power relations, they extended the #MeToo personal action frame.

In this article, we look into how #MeToo and the petition hashtags unfolded together on Swedish-language Twitter, focusing on how hashtags were co-articulated within the #MeToo hashtag ecosystem and what framing effects these practises of co-articulation produced. We will address the following research questions:

RQ1.

When, and with which varying intensities over time, did the Swedish industry-specific hashtags emerge on Twitter?

RQ2.

What interpretive frames emerged around these hashtags, and how did they express and/or relate to the personal action frame of #MeToo and the feminist structural frames used in the petitions?

RQ3.

How did the industry-specific hashtags co-occur with one another, with the #MeToo hashtag, and/or with other hashtags?

RQ4.

How did such co-occurrences constitute co-articulations—discursive relations that adapted, extended, or transformed the #MeToo frame?

Feminist hashtags and their emergence on Twitter

Social media platforms function as spaces for the development of feminist counter-discourse as they enable the linking together of heterogenous personal stories via hashtags (Bernadette Barker-Plummer and Dave Barker-Plummer Citation2017; Rosemary Clark Citation2016). In the feminist tradition of “speaking out” about experiences of gendered violence and injustice, feminist hashtags like #MeToo and others enable collective narratives to form from the practice of linking together personal stories (Serisier Citation2018). Thus, hashtag feminism helps authorise individual stories by placing them side-by-side, eventually constituting a collective story.

While feminist hashtags have affected public discourse by raising awareness and garnering media attention, they have also been criticised for their limited ability to produce political transformation (Clark-Parsons Rosemary Citation2021; Gill Rosalind and Orgad Shani Citation2018; Mendes Kaitlynn, Ringrose Jessica, and Keller Jessalynn Citation2018; Serisier Citation2018). Political hashtags are critiqued for oversimplifying structural political issues, turning them into individual problems that are solved by “cancelling” an individual that has committed acts such as racist comments or sexual harassment (Bouvier Gwen Citation2020; Mendes, Ringrose, and Keller Citation2018; Serisier Citation2018; Gill and Orgad Citation2018). They are also critiqued for overemphasising the act of speaking out, and thus reinforcing neoliberal notions of individual solutions based on women empowering themselves while unjust power relations can remain intact (Banet-Weiser Sarah Citation2018; Serisier Citation2018). On social media in particular, women are called on to speak up and to be empowered, falsely promising a politically meaningful voice while the social media economy rather promotes popularised versions of political messages that reinforce status quo and render marginalised people voice-less (Banet-Weiser Citation2018; Jilly Boyce Kay Citation2020). On the other hand, many prominent men have lost their jobs following allegations of sexual harassment and assault in Sweden (Mikael Delin Citation2018), indicating that #MeToo reached beyond messages of empowerment.

#MeToo in Sweden — industry-specific petitions for change

To date, there are 77 sector-specific Swedish #MeToo initiatives (Hansson Citation2020). In some cases, they developed into petitions that were published on opinion pages in news media and/or handed in to politicians, in which women demand an end to sexism, sexual harassment and assault in their workplaces (Lisa Salomonsson Citation2020). Many of them started out as closed Facebook groups, mailing lists and shared Google Docs where stories were collected and political demands negotiated (Pollack Citation2019; Karin Hansson, Malin Sveningsson, Maria Sandgren, and Hillevi Ganetz et al. Citation2019; Salomonsson Citation2020). In an analysis of the initial 28 petitions published in Swedish news media, Hansson (Citation2020) found that the groups employed particular, structural, feminist frames to construct sexual harassment as a structural problem. These frames differ from the overall media coverage of #MeToo in Sweden and elsewhere, which was largely focused on individual cases concerning celebrities (Askanius and Hartley Citation2019; Sara De Benedictis, Shani Orgad, and Catherine Rottenberg Citation2019).

Furthermore, the organisers and participants in the sector-specific #MeToo initiatives expressed strong feelings of trust in the technological tools used to connect and share stories (Hansson et al. Citation2019). The participants noted the importance of particular technological properties, such as the ability to create closed Facebook groups, where participants could share experiences with one another while constructing a collective narrative that could be transformed into petitions (Salomonsson Citation2020). Thus, #MeToo seems to have dispersed in Sweden in a way that W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg (Citation2012, 755–757) refers to as hybrid between connective and collective action. While #MeToo spread to Sweden via individuals opting into a connective action network built around the hashtag, it also gave rise to semi-official organisations such as those that were formed around the industry-specific petitions that made use of the technological affordances of social media platforms to build coalitions and mobilise resources.

Framing work in connective action networks

Much political action in the internet age is characterised by a networked logic provided by digital technology, tying people together in large-scale, fluid networks (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Manuel Castells Citation2012). Theorised by Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2012) as connective action networks, current political action networks facilitated by social media give rise to particular communities, politics and potential effects. Two elements are especially important in such connective action formations according to Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2012, 744–745); political content that is easily personalised and inclusive of diverse personal motivations, and technology that supports the co-construction and co-distribution of those political themes in networks.

The easily personalised political content of connective action networks separates them from traditional forms of collective action, where individuals need to adopt a collective identity based on ideological or group identification. Framing in social movements based on collective action is described by social movement scholars (see David Snow, Robert Benford, Holly McCammon, Lyndi Hewitt and Scott Fitzgerald Citation2014) as a process of meaning-making, closely tied to collective identities. The resulting frames need to be able to bridge differences among participants, thus making personal expression as political action difficult (Snow et al. Citation2014; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012). Connective action networks require less framing work from the individual as they make use of personal action frames that are easily individualised and often stem from common personal experiences (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012, Citation2013; Jiyoun Suk, Aman Abhishek, Yini Zhang, S. Y. Yun Ahn, T. Correa, C. Garlough, and D. V. Shah Citation2021). Some movement scholars (Snow et al. Citation2014; Zeynep Tufekci Citation2017; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2013) suggest that movements based on personalised political action may find it difficult to frame injustice and pose coherent political demands.

The second property of connective action networks is the role played by digital technology. Bennett and Segerberg (Citation2012, 753) refer to digital technology as an important constituent and actor in emergent connective action networks, as it produces spaces for the co-construction and co-distribution of political content. Furthermore, constituent elements of digital technology add particular properties to connective action networks, such as temporality and fragility, ad hoc organisation, and extendable and adaptable discursive frames (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Maya Stewart and Ulrike Schultze Citation2019, 6; Samuel Merrill and Johan Pries Citation2019).

In this study, we explore the possibilities and limitations of framing work on Twitter in relation to #MeToo in Sweden. We understand #MeToo as an example of a connective action network as it 1) built on a “personal action frame” calling on individuals to share their personal experience without adopting a collective identity or particular ideological affiliation, and 2) dispersed quickly through social media networks. Framing work is understood here as a discursive practice producing political demands, problems and solutions in particular ways. We define discursive practices as articulations of elements in relation to one another, inspired by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (Citation1985). Discursive articulations are thus understood as “any practice establishing a relation among elements such that their identity is modified as a result … ” (Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985, 91). As the discourse of connective action networks emerges within digital media, Twitter is a constituent of the discourse we explore. This context, more broadly, can be conceptualised as a “hashtag ecology” (Moa Eriksson Citation2018, 3987), or “hashtag ecosystem” (Xu Weiai Wayne Citation2020, 1086), wherein the relational network of hashtags and the discursive processes of meaning-making that propagate through it constitute a dynamic environment.

Data and methods

The data for this study was collected using Twitter’s API v2 for academic researchers (https://developer.twitter.com/en/products/twitter-api/academic-research). At the time of data collection in early 2021, data spanning the period from October 15 2017 until March 31 2021 was downloaded. For the purpose of this article, analyses draw on a subsample covering October 15 2017until October 15 2020. As we wanted to analyse the broader context of other hashtags emerging around, and occurring together with, Tweets about #MeToo in Sweden, we sampled Tweets based on them being posted in the Swedish language (as tagged in the Twitter API), and containing the phrase “metoo” with any form of capitalisation and with or without the hash symbol. The resulting dataset consisted of 201,133 Tweets. The majority of the activity took place during the first six to eight months after the initial breakthrough of the hashtag.

Based on our particular interest in the spin-off petitions and related hashtags, we carried out a closer analysis of the posting activity around those hashtags. The sample was made starting from a publicly available inventory of #MeToo-related petitions in Sweden (Hansson Citation2020). This inventory included 77 different petitions, 61 of which could be found in the dataset. This is due to the fact that not all petitions used clearly agreed-upon hashtags, and not all petitions were active on Twitter. Out of these 61 hashtags, we chose to limit the analyses of the emergence and frames of the petitions in relation to RQ1 and RQ2, and the co-articulations in relation to RQ4, to those that occurred more than 200 times in the dataset, as we deemed them more influential in the overall discourse. This meant focusing on the top 18 petition hashtags based on how often they were co-occurring with #MeToo (). See for translations and affiliations of the hashtags.

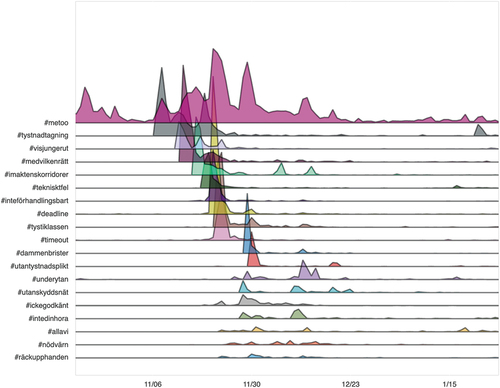

Figure 1. Number of co-occurrences with the #metoo hashtag for the 18 most frequent petition hashtags.

Table 1. Analysed hashtags — translations and affiliations.

In our analysis of how these 18 petition hashtags emerged over time, we produced a categorical ridge plot using the Bokeh visualisation library for Python (https://docs.bokeh.org/). This method leverages KDE (Kernel Density Estimation), meaning that the plot () reflects not absolute numbers, but rather a continuous probability density curve. The motivation for using KDE in our study is that it offers a highly readable visualisation of the varying intensities, expressed as densities, by which the analysed hashtags were used. The higher the curve, the more intense the use of the hashtag at a given point in time.

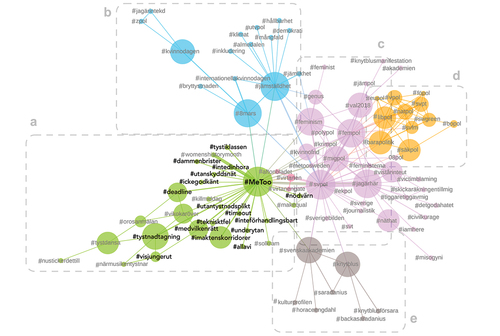

For the network analysis of co-occurrences (RQ3), the entire sample of 61 hashtags was used. A graph was created, using NetworkX (Aric A. Hagberg, Daniel A. Schult, and Pieter J. Swart Citation2008), based on co-occurring pairs of hashtags in the dataset (33,959 pairs in the 201,133 Tweets). For visualisation, using Gephi (Mathieu Bastian, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy Citation2009), edges with a weight below 50 were filtered. Connections between hashtags that happen less than 50 times are not shown as a connecting line (), and hashtags that are not part of any co-occurrence pair that appears 50 times or more are not shown as nodes in the visualisation. The width of edges (connecting lines) represents the number of connections (weight). The size of the visualised nodes is scaled according to their network centrality, calculated as betweenness (Ulrik Brandes Citation2001), and the node colours are set according to which cluster nodes belong to (Renaud Lambiotte, Jean-Charle Delvenne, and Mauricio Barahona Citation2009). The interpretation of is thus that the larger the circle, the more important the hashtag is in the relational system of co-occurring hashtags; the thicker the connecting lines, the more often two hashtags are used together in Tweets; and, hashtags with the same colour occur together often enough for them to be considered as belonging to a cohesive cluster of hashtags that tend to be used in similar contexts.

Figure 3. Clustered network of co-occurring hashtags in tweets (cluster a: petition hashtags; b: women’s day/gender equality; c: gender and migration in Swedish politics; d: Swedish politics and the 2018 election; e: Swedish academy scandal).

Discourse analysis was used for RQ2 and RQ4, which examine framing practises in relation to the emergent hashtag ecosystem described above. We coded 2,360 Tweets from a subset of the 5,640 Tweets that contained the #MeToo tag and one or more of the top 18 petition hashtags. Tweets were selected by excluding retweets and replies in order to elicit themes only from original #MeToo posts. For RQ2, we used open coding to derive themes and frames from the material, resulting in codes such as “culture of silence, disgust/anger, bravery.” We used closed categories to code expressions of structural/feminist frames or individual/personal action frames. Tweets were coded as “individual” if they relied on the acts of individuals (not in a formal capacity, such as individual politicians) for representations of problems and solutions, or if they spoke out about personal experiences of sexual violence. Tweets were coded as “individual + structural” when they encompassed both acts of individuals and either structural explanations of problems, political solutions, or references to collective action. Tweets were coded as structural if they exclusively addressed problems and/or solutions in terms of structure, meaning culture, power relations, political initiatives, or work-place or industry-related changes.

In order to understand practises of co-articulation of hashtags as framing work in response to RQ4, we used the following concepts derived from David A. Snow, E. Burke Rochford, Steven Worden and Robert Benford (Citation1986):

frame extension—extending the boundaries of the #MeToo personal action frame to encompass differing understandings of problems and solutions;

frame amplification—activating a particular frame in a new context, e.g., using one petition hashtag in the launch of another;

frame bridging—linking structurally unrelated but compatible frames to one another; and

frame transformation—transforming the meaning of a frame by applying new understandings of problems and solutions.

Ethical Considerations

Since Twitter users were not informed about this study, and since the content touches on personal and sensitive stories, we have followed the ethical recommendations of the Association of Internet Researchers in the following ways; we have removed Twitter handles of content producers and other mentioned users; translated Tweets from Swedish to English in a non-verbatim manner; and masked links (Casey Fiesler and Nicholas Proferes Citation2018; Annette Markham Citation2012; Association of Internet Researchers Citation2012; Clark-Parsons Citation2021).

Findings

The emergence of a hashtag ecosystem

Turning first to RQ1, about when and with which intensities the Swedish industry-specific hashtags around #MeToo emerged on Twitter. shows the intensities of the top 18 most frequent petition hashtags. The figure covers the period from mid-October 2017, when #MeToo took off on Twitter, until the end of January 2018. This is the window of time within which most of the Twitter activity around the petition hashtags happened.

The plot reveals that there are two typical shapes by which petition hashtags appeared. The first shape is represented by patterns by which there is an initial spike in activity, in most cases coinciding with publications launching the petitions on various mainstream media platforms. Examples of this pattern are mirrored by the first twelve subplots below the shape for #MeToo at the top of . All petitions from #tystnadtagning and down to #utantystnadsplikt follow a pattern by which there is initial explosive activity, followed by a waning pattern with a number of intermittent smaller spikes in activity.

The second type of shape is represented by the bottom seven petitions in . The intensities of the petitions ranging from #underytan to #räckupphanden all represent more of a simmering pattern where there are some initial, softer, waves gradually picking up intensity to reach their highest levels over time, and not in the form of any significant sole spike. Some of these also have several spikes of near-equal intensity, rather than a gradually waning pattern. These differing shapes of intensity indicate that the hashtag ecosystem around #MeToo is structured as a connective action network constituted by smaller networks formed around the petition hashtags, tied together while simultaneously following different patterns of activity.

Interpretive frames across hashtags

We turn now to RQ2 about the framing of problems and solutions related to the issue of sexual harassment and assault. As mentioned in relation to RQ1, the emergence of petition hashtags on Twitter coincided with coverage of them in mainstream media as circulating content from media outlets was a common practice in the dataset. By contrast, personal accounts of experiences of sexual harassment and assault were rare in the dataset. The content of early petition hashtag Tweets suggests that other platforms were used for collecting personal stories, while Twitter was used by petition organisers and participants to spread petition content, as seen in the examplesFootnote1 below:

Enough now! I am one of the 1,400 signatories of the petition #imaktenskorridorer #metoo https://<link>

I have signed, of course. Trade unions are all about equality, justice, and solidarity. Patriarchal structures belong in the history books along with sexual assault and harassment. It is #inteförhandlingsbart [“non-negotiable”] #metoo https://<link>

Additionally, Twitter users employed Twitter @-mentions to call out or pull in responsible politicians and organisations. Doing so visibly connected the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault in the workplace with powerful actors that were deemed responsible by the Twitter audience, as seen in the example Tweets below.

In the list of candidates for the government from [political party], there is one man who is reported for rape against @<user>. What do you have to say @<political party>? #metoo #metoosweden #imaktenskorridorer #riksdagsvåldet [“parliamentary violence”]

This is really happening, right now. What is Skolverket, Lärarförbundet, Skolinspektionen doing to fix it? No one dares to say anything for fear of consequences. @<user> [head of Lärarförbundet] @<user> [then minister for upper secondary education] @<user> [former minister for upper secondary education] #gymnasieminister #metoo #metoosweden #tystiklassen https://<link>

Recommended reading: “Here are the election promises we in metoo-uppropen want to see” #val2018 [“Election 2018”] #imaktenskorridorer #tystnadtagning #metoo https://<link> @<user> [then minister of equality] @<user> [then minister of social work] @justitiedep [department of justice] @<user> [then minister of upper secondary education]

Petitions, Twitter users, and Twitter affordances thus co-produced extensions of the initial #MeToo frame of speaking out about personal experiences. As the speaking was done elsewhere, Twitter became a platform for widened reach, dialogue with responsible actors, and for posing political demands in front of an audience. This is arguably related to the constitution of the Swedish Twitter audience. Only 18% of Swedes aged 8 and over use Twitter, (Internetstiftelsen, The Swedish Internet Foundation Citation2022) and Swedish Twitter is sometimes referred to as a place for journalists and politicians exclusively. The five Swedish accounts with the highest engagement rate in 2021 belonged to three top politicians, one political activist and one political journalist (Medieakademin Citation2021). This makes such meaningful “mentions” possible, which frames #MeToo as a structural issue.

Throughout the dataset, Tweets construed the problem with sexual violence in the workplace as supported by a culture of silence or a sexist culture in workplaces, whole industries, and in society as a whole. The two examples below show how such cultures were cited as explanations for the prevalence of sexual harassment and violence in the workplace:

#metoo #visjungerut #tystnadtagning and now #medvilkenrätt. Important testimonies show sexism is prevalent throughout society. No one gets spared, no matter what education or background you have. This is everybody’s problem!

It’s the male structures that need to be changed! #medvilkenrätt #metoo #kräverförändring [“demand change”]

Thus, the personal action frame of #MeToo was extended in the Twitter discourse around the petition hashtags to encompass structural explanations of the prevalence of the problem and demands for political solutions. This extension emerged from the language of the petition op-eds as well as Twitter affordances such as links and mentions. In effect, this suggests that #MeToo constitutes a hybrid form of activism in which participants also perform framing work and adopt a sort of collective identity as a basis for posing demands.

Further indicating this hybridity, articulations of the act of speaking out, which were central in the discourse, seemed to support both structural frames and personalised action frames. Tweets praised women for speaking out, and both victim-survivors and bystanders were called on to speak up and resist male violence. Such depictions of the act of speaking out as brave and strong, although rightful, may reinforce neoliberal iterations of feminism that focus on individual women’s empowerment and confidence as solutions to gender inequality (Banet-Weiser Citation2018). In the three examples below, Tweets described the act of speaking out as brave, prompted victim-survivors and others to speak up, and urged victim-survivors to report crimes to the police:

My daughter asked, why is it okay because we are children? Although us adults act as if it were okay, it is not. To my daughter—keep getting angry when someone doesn’t treat you right. Don’t accept bad treatment, never be ashamed, always speak up. #metoo #tystiklassen https://<link>

“The perpetrator’s best friend is silence,” a quote from #allavi #metoo Whenever you see or hear something, whenever you are exposed to violence, scream and yell!

I’m so angry—report the crimes to the police, nail those perpetrators right now! Women in the tech industry launch #teknisktfel https://<link> #svpol [“Swedish politics”] #crime #sexcrime #justice #police #report #metoo #technology

By calling on women to speak out, Tweets risked framing the problem as simply related to speaking, and thus the mere act of speaking out becomes the solution (Serisier Citation2018). This shifts the attention away from the violent acts, the men who performed them, and the structures and power relations that support the prevalence of these acts. Further, the technological promise of access to vast audiences might actually reinforce unequal possibilities for meaningful political voice, as pointed out by Kay (Citation2020, 7–8). Thus, speaking may only be a solution for some.

By contrast, both petition participants and other Twitter users praised the petitions for using the collected stories as a basis for posing particular political demands. In the two Tweet examples below, #MeToo and the petitions were construed as changemakers:

ALL TOGETHER NOW—we need to continue with this much-needed societal change! [heart emoji] #metoo #tystnadtagning #timesup

It seems like it’s really happening at last: #sjungut #teknisktfel #tystnadtagning #deadline #medvilkenrätt and more will come—this is a structural problem #metoo https://<link>

These expressions of hope framed #MeToo and the petitions as much-needed instigators of societal change.

Notably, the circulation of petition content on Twitter seemed to open up discursive space for structural framings of problems and solutions that went beyond speaking out. This was further reinforced by Tweets that made use of @-mentions to pose political demands to organisations and politicians, as well as Tweets that co-articulated petition hashtags with political hashtags and hashtags that signalled structural framings of problems, as will be further discussed in relation to RQ3 and RQ4 below.

Mapping the network of hashtags

Turning then to RQ3, about how the petition hashtags co-occurred with one another, with the #MeToo hashtag, and with other hashtags, the network visualisation presented in gives an overview of the context.

It is notable, firstly, that all of the top 18 hashtags, except two, appear as belonging to the same cluster (A) in the network. The tags #tystiklassen, #dammenbrister, #ickegodkänt, #utantystnadsplikt, #timeout, #teknisktfel, #imaktenskorridorer, #inteförhandlingsbart, #underytan, and #allavi all appear as “satellite” hashtags of #MeToo, the only connection (with a weight of 50 and above) to any other hashtag is to #MeToo.

By contrast, another subset of tags — #deadline, #medvilkenrätt, #tystnadtagning, and #visjungerut—constitute a more dynamic (cf. cross-connections) and active (cf. node sizes) sub-network within the larger cluster. Interestingly, here, additional #MeToo-related tags, not surfacing as being among the most prominent ones based on their direct co-occurrence with #MeToo (), appear. Tags such as #tystdansa (“be quiet and dance,” dancers), #vikokaröver (“overboiled,” restaurants), and #orosanmälan (“notification of concern,” social workers), when considering their co-occurrences with other hashtags than #MeToo, have clearly played an even more important role in the overall relational system of tags than some of the “satellite” hashtags mentioned earlier. Similarly, but not as prominent, the tags #intedinhora (“not your whore”) and #utanskyddsnät (“without a safety-net”), constitute a minor sub-network through cross-connection.

Some of the relations in thses sub-network can possibly be explained by offline connections or similarities between the groups behind the petitions. For instance, the co-occurrence of the hashtags related to actors’ petitions #tystnadtagning, opera singers’ petitions #visjungerut, dancers’ petitions #tystdansa and the music industry petition #närmusikentystnar, as well as the co-occurrence of the hashtags #intedinhora and #utanskyddsnät, which related to women and girls in vulnerable positions in society (who have experienced commercial sexual exploitation, and who engaged in drug use, sex work or criminal activities, respectively).

Furthermore, the network analysis shows that the #MeToo hashtag, aside from being a hub in the cluster of petition hashtags, is also embedded in a broader ecosystem, where it brings together clusters relating to International Women’s Day and discourse on gender equality (B), gender and migration in Swedish politics (C), Swedish politics and the 2018 election (D), and the sexual assault scandal surrounding the Swedish Academy (Richard Orange Citation2018).

Hashtag co-articulations as framing work

By turning to RQ4, we explore the ways in which the petition hashtags, the #MeToo hashtag and other hashtags co-occurred in the Tweets. We suggest that these co-occurrences can be understood as practises of co-articulation that extended and transformed the #MeToo frame and brought together the clusters of hashtags mentioned above into an emergent hashtag ecosystem.

When petition hashtags and the MeToo hashtag are simply stacked at the end of a Tweet, their co-articulation takes the shape of a chain of equivalence forming an interpretative frame for the Tweet as a whole. This may work as a form of frame amplification (Moa Eriksson Krutrök and Simon Lindgren Citation2018), where new petition initiatives use previous petition hashtags to ensure reach and produce particular meanings without addressing them explicitly in the Tweet language. Such amplification by hashtag stacking at the end of the Tweet is a common pattern throughout the petition Tweets that practice co-articulation, as seen in the two examples below:

Yet another industry, and I’m not surprised. This is reality, this is what is considered normal. #metoo #medvilkenrätt #visjungerut #tystnadtagning #notsilentanymore https://<link> @SvD [newspaper Svenska Dagbladet]

“Not all men”? #svpol #metoo #deadline #tystnadtagning #närmusikentystnar #medvilkenrätt #inteförhandlingsbart #visjungerut #teknisktfel #imaktenskorridorer #tystdansa #vikokarover #stilleforopptak #ickegodkänt #tystiklassen #timeout #tystdansa

Similar to hashtag stacking, the #MeToo hashtag and one or more petition hashtags are sometimes co-articulated in linguistically meaningful ways, where the hashtags function as words in a story or message. Arguably, this linguistic co-articulation produces the same effect of frame amplification, but can also constitute framing work that extends or even transforms the #MeToo frame by negotiating problems and solutions, similar to framing work done within collective action organisations. In the example below, three petition hashtags are articulated together with suggestions that they represent only the beginning of the #MeToo movement, and that more will come:

More to come in relation to #metoo. #tystnadtagning, #visjungerut and now #medvilkenrätt is a brave and impressive start! https://<link>

Additional hashtags are also connected to the #MeToo and petition hashtags in these ways. Notably, well-established hashtags that refer to topics around Swedish gender equality and migration politics were used, producing frame bridging effects that embed the #MeToo discourse within a larger hashtag ecosystem, as mentioned in relation to RQ3 (cluster C). The two examples below use hashtags related to gender equality politics (#fempol, #feminism), supporting the framing of sexual harassment and assault as a structural problem with political solutions mentioned in relation to RQ2:

4139 journalists have had enough. Follow @deadline_nu [official account for #deadline] for updates on the latest #MeToo petition! #Deadline #ffse [’Follow Friday Sweden’] #fempol [’Feminist politics’] #tystnadtagning #visjungerut #imaktenskorridorer #inteförhandlingsbart https://<link>

Agreed! #imaktenskorridorer #metoo We need more #fempol #feminism to protect and deepen our #democracy #eupol [“EU politics”] #svpol https://<link>

Furthermore, the dataset includes other hashtags that suggest feminist interpretative frames in relation to the causes of sexual violence, such as norms and the patriarchy. Co-articulations of such hashtags with the #MeToo hashtag provide an interpretative framework that extends the #MeToo-frame beyond speaking out, as mentioned in relation to RQ2. In the first example below, the hashtags #normcritique and #consent frame problems and solutions as structural. The second and third example use the hashtags #patriarchy and #womensrightsarehumanrights, framing #MeToo as a feminist issue related to power relations and women’s rights. The fourth example shows how #MeToo is co-articulated with hashtags from the equality cluster (B) mentioned in relation to RQ3, in this case #genderequality:

#ickegodkänt are disappointed at the open letter from the trade-unions. We feel it lacks a proper plan of action. #metoo #school #teachers #normcritique #consent https://<link>

11,050 physicians have signed #utantystnadsplikt #metoo #sexism #sexualharassment #abuse #kvinnouppror [’feminist uprising’] #patriarchy #svpol #opinionlive [’Swedish TV debate show’] https://<link>

To all of those who said #metoo would disappear as quickly as it came about, and that it wouldn’t bring change. Another horrible testimony. “Will destroy your career before it even started” https://<link> #medvilkenrätt #womensrightsarehumanrights

Join forces, demand a stop to nude scenes! https://<link> #tystnadtagning #metoo #vågavägra [’dare to refuse’] #mänsomhatarkvinnor [’men who hate women’] #genderequality #feminism

Tweets that make use of hashtags related to migration politics, on the other hand, constitute a transformation of the #MeToo frame. Some Tweets combine the #MeToo and #migpol (“migration politics”) hashtags to shift attention away from issues of sexual harassment and assault and towards critical narratives around immigration. Such Tweets perform acts of frame bridging between the #MeToo discourse and the discourse in Swedish immigration politics by highlighting crime as an imagined connection. In the first example below, attack rapes are said to be committed almost exclusively by immigrants. In the second example, the Tweet extends the #MeToo-related frame of cultures of silence by claiming there is a similar culture around proposed connections between criminality and immigration:

Immigrants commit 95% of attack rapes, when will we pay attention to that? #medvilkenrätt #metoo #aktuellt [Swedish TV news show] #Sweden #svpol #migpol [“migration politics”] #rapefugees https://<link>

The taboo surrounding sexual harassment in the workplace is just like the taboo surrounding criminality connected to immigration because of #migpol #svpol #metoo #deadline #tystnadtagning #taboo #multiculturalism #migration #crime

Additionally, non-established hashtags are sometimes used to reinforce the meaning of the Tweet language. This disregards the tagging aspect of hashtags to make content easily accessible, rather they seem to be used precisely for co-articulation purposes. This points to the co-creation of social media platforms by developers and users. While hashtags have the functionality to organise Twitter content into searchable categories, users also utilise them to give context and meaning to Tweets by articulating them in discursively meaningful ways (Suk et al. Citation2021, 280). The first example below shows how the hashtag #thebystander reinforces the claims in the Tweet language, calling on bystanders to speak up. In the second example, the hashtags #shame and #perpetrator are used to express a connection between the practice of speaking out about one’s experiences of sexual violence and shifting the blame from the victim-survivors to the perpetrator:

We need to make sure co-workers also dare to speak up when they see something. The key is joint action. #MeToo #utantystnadsplikt #thebystander https://<link>

Watching #tystnadtagning one more time, I’m moved and feel confident we need to shift the #shame to where it belongs, with the #perpetrator! #metoo https://<link>

As the analysis for RQ4 shows, hashtag co-occurrences in relation to the #MeToo and Swedish petition hashtags constitute meaningful co-articulations that extend and transform the #MeToo frame, and produce frame bridging effects that position #MeToo within a wider discourse around Swedish politics and discourse on gender equality.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we have mapped the emergent “hashtag ecosystem” of Swedish #MeToo and its industry-specific spin-off hashtags on Twitter. The results indicate that the #MeToo and petition hashtags were embedded in a broader ecosystem of hashtags and topics, as they brought together clusters of hashtags relating to gender equality and feminism, Swedish politics on gender and migration, and the 2018 Swedish election. We suggest that these hashtag co-occurrences constituted discursive co-articulations that negotiated, extended and transformed the #MeToo personal action frame. Twitter users employed platform affordances such as hashtags and @-mentions, and drew on different iterations of feminism, to perform framing work. Although political hashtags based on personal action frames, such as #MeToo, risk individualising structural problems, we suggest that they also give rise to dynamic negotiations of meaning that can extend such frames. In some contexts, framing work through discursive co-articulations and technical affordances may transform political hashtags into hybrid and entangled forms of connective and collective action networks of networks that build on both personal and collective identities and understandings of problems and solutions.

The hashtag ecosystem that emerged with #MeToo on Swedish Twitter illustrate the complex meaning-making processes and networked structures involved in social media-mediated discourse production. This study aims to widen the understanding of the possibilities and limitations of political hashtags. By focusing on the co-articulation of hashtags, we suggest that social media users utilise platform affordances in creative ways to do framing work that modifies and expands the limits of personal action frames.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa Lindqvist

Lisa Lindqvist is a PhD student in Sociology at Karlstad University, Sweden. Her research interests include mixed methods approaches to social media activism, framing practices in political hashtags, and user experiences of doing feminism in digital spaces. Her focus is on the Swedish #MeToo movement as a sociotechnical phenomenon, its constituent discourses, and the affective dimensions of participation.

Simon Lindgren

Simon Lindgren is Professor of Sociology at Umeå University, Sweden, and director of DIGSUM, an interdisciplinary academic research centre for the study of social dimensions of digital technology. His research is about politics, power, and resistance at the intersection of society and digital technologies. He uses critical discourse approaches, computational text analysis, and social network analysis to study issues relating to movements, mobilization, opinions, and identities.

Notes

1. All Tweet examples are translated from Swedish to English, and slightly reworded, by the authors.

References

- Askanius, Tina, and Jannie Møller Hartley. 2019. “Framing Gender Justice: A Comparative Analysis of the Media Coverage of #metoo in Denmark and Sweden.” NORDICOM Review: Nordic Research on Media and Communication 40 (2): 19–36. doi:10.2478/nor-2019-0022.

- Association of Internet Researchers. 2012. “Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIr Ethics Working Committee (Version 2.0).” Aoir.org. Accessed March 14, 2022. http://www.aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2018. Empowered: Popular Feminism and Popular Misogyny. Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9781478002772.

- Barker-Plummer, Bernadette, and Dave Barker-Plummer. 2017. ”Hashtag Feminism, Digital Media, and New Dynamics of Social Change: A Case Study of #YesAllWomen.” In Social Media and Politics: A New Way to Participate in the Political Process, edited by Glenn W. Richardson, 79–96. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy. 2009. “Gephi: An Open-Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks.” In Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/13937/13786

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2012. “The Logic of Connective Action.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 739–768. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2013. ”The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics.” In Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139198752.

- Booth, Andrea, and Kelsey Munro. 2017. “Why is the #MeToo Movement Sending Shockwaves Through Sweden?” SBS News, November 27. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/why-is-the-metoo-movement-sending-shockwaves-through-sweden

- Bouvier, Gwen. 2020. “Racist Call-Outs and Cancel Culture on Twitter: The Limitations of the Platform’s Ability to Define Issues of Social Justice.” Discourse, Context & Media 38: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100431.

- Brandes, Ulrik. 2001. “A Faster Algorithm for Betweenness Centrality.” The Journal of mathematical sociology 25 (2): 163–177. doi:10.1080/0022250X.2001.9990249.

- Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity.

- Clark, Rosemary. 2016. ““Hope in a Hashtag”: The Discursive Activism of #WhyIStayed.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (5): 788–804. doi:10.1080/14680777.2016.1138235.

- Clark-Parsons, Rosemary. 2021. ““I SEE YOU, I BELIEVE YOU, I STAND WITH YOU”: #MeToo and the Performance of Networked Feminist Visibility.” Feminist Media Studies 21 (3): 362–380. doi:10.1080/14680777.2019.1628797.

- De Benedictis, Sara, Shani Orgad, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2019. “#MeToo, Popular Feminism and the News: A Content Analysis of UK Newspaper Coverage.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (5–6): 718–738. doi:10.1177/1367549419856831.

- Delin, Mikael. 2018.”Dokument: Metoo kan påverka – även om det inte blir en valfråga.” Dagens Nyheter, January 1. https://www.dn.se/nyheter/sverige/dokument-metoo-kan-paverka-aven-om-det-inte-blir-en-valfraga/

- Eriksson, Moa. 2018. “Pizza, Beer and Kittens: Negotiating Cultural Trauma Discourses on Twitter in the Wake of the 2017 Stockholm Attack.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 3980–3996. doi:10.1177/1461444818765484.

- Eriksson Krutrök, Moa, and Simon Lindgren. 2018. “Continued Contexts of Terror: Analyzing Temporal Patterns of Hashtag Co-Occurrence as Discursive Articulations.” Social Media + Society 4 (4): 205630511881364. doi:10.1177/2056305118813649.

- Fiesler, Casey, and Nicholas Proferes. 2018. ““Participant” Perceptions of Twitter Research Ethics.” Social Media + Society 4 (1): 205630511876336. doi:10.1177/2056305118763366.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Shani Orgad. 2018. “The Shifting Terrain of Sex and Power: From the ‘Sexualization of Culture’ to #MeToo.” Sexualities 21 (8): 1313–1324. doi:10.1177/1363460718794647.

- Hagberg, Aric A., Daniel A. Schult, and Pieter J. Swart. 2008. “Exploring Network Structure, Dynamics, and Function Using NetworkX.” In Proceedings of 7th Python in Science Conference SciPy Conference, edited by Gael Varoquaux, Travis Vaught, and Jarrod Millman, 11–15. Pasadena, CA, August 19–24.

- Hansson, Karin. 2020. ”#Metoo petitions in Sweden 2017–2019 (version V2).” (dataset). Harvard Dataverse. doi:10.2478/njms-2020-0011.

- Hansson, Karin, Malin Sveningsson, Hillevi Ganetz, and Maria Sandgren. 2020. “Legitimising a Feminist Agenda: The #metoo petitions in Sweden 2017–2018.” Nordic Journal of Media Studies 2 (1): 121–132. doi:10.2478/njms-2020-0011.

- Hansson, Karin, Malin Sveningsson, Maria Sandgren, and Hillevi Ganetz. 2019. “’We Passed the Trust on’: Strategies for Security in #MeToo Activism in Sweden.” In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work: The International Venue on Practice-Centred Computing and the Design of Cooperation Technologies – Exploratory Papers, Reports of the European Society for Socially Embedded Technologies. doi:10.18420/ecscw2019_ep14.

- Internetstiftelsen, The Swedish Internet Foundation. 2022. “Svenskarna och internet 2022.” Accessed October 21, 2022. https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/rapporter/svenskarna-och-internet-2022/

- Kay, Jilly Boyce. 2020. Gender, Media and Voice: Communicative Injustice and Public Speech. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47287-0.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

- Lambiotte, Renaud, Jean-Charles Delvenne, and Mauricio Barahona. 2009. “Laplacian Dynamics and Multiscale Modular Structure in Networks.” IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 1 (2): 76–90. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2015.2391998.

- Markham, Annette. 2012. “Fabrication as Ethical Practice.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (3): 334–353. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2011.641993.

- Medieakademin. 2021. “Maktbarometern.” Accessed January 22, 2022. https://medieakademin.se/maktbarometern/

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessica Ringrose, and Jessalynn Keller. 2018. “#MeToo and the Promise and Pitfalls of Challenging Rape Culture Through Digital Feminist Activism.” European Journal of Women’s Studies 25 (2): 236–246. doi:10.1177/1350506818765318.

- Merrill, Samuel, and Johan Pries. 2019. “Translocalising and Relocalising Antifascist Struggles: From #KämpaShowan to #KämpaMalmö.” Antipode 51 (1): 248–270. doi:10.1111/anti.12451.

- Orange, Richard. 2018. ”No Peace Prize: The Continuing Crisis Inside the Swedish Academy.” TLS Times Literary Supplement (6029): 24. Gale Academic OneFile. Accessed January 22, 2022. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A632754915/AONE?u=anon 76934357&sid=googleScholar&xid=63824b91

- Pollack, Ester. 2019. “Sweden and the #MeToo Movement.” Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 10 (3): 185–200. doi:10.1386/iscc.10.3.185_1.

- Salomonsson, Lisa. 2020. “Is #akademiuppropet a Kind of Digital Counter-Public?” European Journal of Women’s Studies 27 (1): 89–98. doi:10.1177/1350506819885708.

- Serisier, Tanya. 2018. Speaking Out – Feminism, Rape and Narrative Politics. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98669-2.

- Snow, David, Robert Benford, Holly McCammon, Lyndi Hewitt, and Scott Fitzgerald. 2014. “The Emergence, Development, and Future of the Framing Perspective: 25+ Years Since ”Frame Alignment”.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 19 (1): 23–46. doi:10.17813/maiq.19.1.x74278226830m69l.

- Snow, David A., E. Burke Rochford Jr, S K. Worden, and R D. Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” American sociological review 51 (4): 464–481. doi:10.2307/2095581.

- Stål, Kajsa, Magnus Abrahamsson, and Maria Höglund. (Executive Producers). 2021. “Metoo – hösten som förändrade Sverige [Metoo – The Autumn that Changed Sweden] [TV Documentary Series].” Brand New Content; SVT, Sveriges Television AB. https://www.svtplay.se/metoo-hosten-som-forandrade-sverige

- Stewart, Maya, and Ulrike Schultze. 2019. “Producing Solidarity in Social Media Activism: The Case of My Stealthy Freedom.” Information and Organization 29 (3): 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.003.

- Suk, Jiyoun, Aman Abhishek, Yini Zhang, S Y. Yun Ahn, T. Correa, C. Garlough, and D V. Shah. 2021. “#MeToo, Networked Acknowledgment, and Connective Action: How “Empowerment Through Empathy” Launched a Social Movement.” Social science computer review 39 (2): 276–294. doi:10.1177/0894439319864882.

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2017. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Weiai Wayne, Xu. 2020. “Mapping Connective Actions in the Global Alt-Right and Antifa counterpublics.” International Journal of Communication 14. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11978.