ABSTRACT

We still know little about whether and how gender informs, shapes, or influences art perception. This multidisciplinary article investigates the role that gender might play in the perception of art through historical analyses and an eye-tracking experiment. We first traced how gender identity, sexual identity, and sexual orientation have been used to theorize the existence of a gender-binary difference between viewers in traditional aesthetics and feminist art theory. To test whether such claims reflect any measurable experience, we collected eye-tracking data from 84 participants and divided them into two groups of cisgender, heterosexual individuals by self-definition. Each group participated in two experiments; the first showed digital reproductions of mixed artworks, varying in subject, style, form, and size; the second showed artworks with only one figure, either explicitly showing sex-linked traits or not. In both cases, we measured the number of fixations, average fixation duration, and saccade amplitude as well as differences in the location of fixations and entropy. Our analysis did not detect any significant difference between the groups. This proves empirically, for the first time, that in spite of having been often reiterated in history, gender binary categories are not suitable for describing the visual perception of art.

Introduction

In 2008, in a compelling critical review of the work conducted in the field of Feminist Philosophy of Art, A.W. Eaton listed some of the questions to which the research thus far could not provide a satisfying answer (Anne A. W Eaton Citation2008). More than 10 years have passed, bringing along new directions for feminist studies, intersectional debates, and an essential updated review “Feminist Aesthetics” (A. W Eaton Citation2021). A comparison between the two articles shows that, while the discourse has been greatly amplified, some of the questions Eaton originally asked remained unanswered, or at least largely unexplored. Among them is the following: In what ways does gender inform, shape, or influence art perception and the aesthetic experience?

The question can be tackled from different perspectives; at least one of them, Eaton points out, should be empirical; an answer could and should come from art history, psychology, and cognitive science (Eaton Citation2008, 876). As it will become clearer in the course of this paper, however, each of the disciplines which has engaged with the issue empirically has, so far, only produced partial and unsatisfactory answers.

Inquiries of art-historical nature on the “male” and “female” aesthetic experience have mainly focused on uncovering the links between socio-economic structures and the construction of gender in its complexity—encompassing not only biological sex but also gender identity and sexual orientation. Hence, we now know that supposed gender-based differences in the perception of art are historically tied to socially constructed, multifaceted gender roles and expectations; however, it remains unclear whether these differences have been merely prescribed at a theoretical level or could be in fact experienced by art viewers.

Studies in psychology and cognitive science, on the other hand, have been able to quantify experienced differences in art perception—yet more often than not, they rely on an oversimplified understanding of gender as a category. Factors such as sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not considered individually as contributing elements to a definition of gender. This easily leads to a misattribution of sex-based results to differences in gender identity, and vice versa.

In light of these methodological limits, this paper argues for the necessity of a transdisciplinary answer to the question posed by Eaton, an answer which can, respectively:

Clarify which aspects of gender have been taken into account when investigating how it informs, shapes, or influences the perception of art and

assess whether gender differences in the perception of art are in fact experienced by viewers and can be translated into monitorable behaviour.

We try to fill this gap by combining theoretical and experimental methods. The historical study analyses what aspects of gender have historically been described as relevant in the visual experience of art. To do so, it outlines different sources in which perception has been discussed as a gendered phenomenon: in traditional aesthetics (eighteenth to nineteenth century) and in feminist art theory (twentieth century). These examples will show how the act of looking at artworks has historically been subjected to a binary categorization.

The second study assesses experimentally whether these gender-binary categories reflect a measurable behaviour. We designed two different eye-tracking experiments. In both cases, we looked for differences in as many oculometric parameters as possible: number of fixation, fixation duration, and saccade amplitude as well as differences in heatmaps of fixations and entropy, between two groups of self-identified cisgender, heterosexual men, and women. Our aim was to understand whether sex, gender identity, and/or sexual orientation affect art perception in a way that could be described as binary with any statistical significance. The results of the study show that this is not the case.

Method 1) Historical study

Gender roles and the explorative gaze

Through centuries of theoretical speculation, the perception of art came to be understood as a binary phenomenon. The way we look at, and appreciate, artworks has often been described in historical sources by highlighting the perceptual capabilities of one group through direct contrast with another.

Given that discourses on aesthetic theory have historically been male dominated (Linda Nochlin Citation1971), it comes as no surprise that the authors, discussing gender-based differences, define aesthetic perception as an innate ability of the male sphere. To give a notable example, in the third section of his Observation on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764), Immanuel Kant discusses the opposite tendencies between men and women at the level of perception. According to Kant, women are innately drawn towards mostly beauty, to everything that is decorative and adorned; men, on the other hand, to the sublime (AA 02:228). The sublime is an intellectual, sopra-sensual, and abstract category, which, according to Kant, women are naturally incapable of grasping because of their lack of reason (John T Goldthwait Citation1991, xxix).

This binary contrast, first introduced by Edmund Burke with his Philosophical enquiry into the Origins of our idea of Sublime and Beautiful (Citation1757), quickly finds a relevant position within the European aesthetic discourse. In his satirical poem Lyric Odes to the Royal Academicians, published in 1782 Peter Pindar describes the annoying behaviour of female visitors of an art exhibition:

Although the Ladies with such Beauty blaze,

They very frequently my passion raise—

(…) Passing amidst the Exhibition crowd,

I heard some Damsels Fashionably loud;

(…)

What charming Colours! here’s fine Lace, here’s Gauze!

What pretty Sprigs the fellow draws!

(…)

See those red Lips, oh la! they seem so nice!

What rosy Cheeks then, Cousin, to entice!

(Reported in Palmer Citation2009, 6)

The female visitors unnerve the poet by being too excited about trivial aspects of painting: how painters render objects and images of their daily interest such as lace, or how beautifully they portray lips and cheeks. Pindar’s critique, much like Kant’s, stems from the assumption that women would be incapable of, and uninterested in, grasping complex matters such as philosophy, mythological allegories, and generally more abstract aspects of the artistic endeavour. They are distracted by details, searching in the image for the elements that appear familiar to them.

Similarly, in his 1851 collection of essays Parerga and Paralipomena, Arthur Schopenhauer writes on women:

Women never get beyond a subjective point of view. (.) ordinary women have no susceptibility for art at all (.) their way of looking at things is quite different from ours; they like to take the shortest way to their goal, and, in general, manage to fix their eyes upon what lies before them; while we, as a rule, see far beyond it. (.) those concrete things, which lie directly before their eyes, exercise a power which is seldom counteracted to any extent by principles of thought (.) or in general, by consideration for the past and the feature, or regard for what is absent or remote. (Schopenhauer, Citation1990, 196)

The domain of women has hence been considered the present, the trivial, and the daily. Conversely, men were described as able to go beyond the subjective point of view, being able to recur to the blind intellect, to consider what is absent, and remote. Similarly, John Ruskin would discuss the roles and duties of men and women in Victorian society in Sesame and Lilies (1865) and declare that women’s aesthetic power lies mostly in the arrangement of the house (Ruskin, Citation1900, 84).

The sources above highlighted described one type of binary contrast, which corresponds to the dominant narrative of aesthetic literature produced between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the intellectual, abstracted perception of men juxtaposed to the “too detailed” and superficial perception of women. At least until 1900, it is rare to encounter sources of this kind written from a woman’s perspective. The travel diaries of Lady Eastlake (1809–1893), wife of the painter, collector, writer, and director of the National Gallery, Charles Eastlake (1793–1865) are a notable exception. Her publications served a specific purpose: justifying the presence of women in the cultural spheres of respectable society in Victorian England. Writing in an anonymous form and adopting the tone of a gentleman, Lady Eastlake contrasts the eyes of women with those of men in an 1845 article for the Quarterly Review:

That there are peculiar powers inherent in ladies’ eyes, this number of the Quarterly Review was not required to establish; but one in particular (…) we must in common gratitude be allowed to point out. We mean that power of observation (…) which once removed from the familiar scene and returned to us in the shape of letters or books, seldom fails to prove its superiority. Who, for instance, has not turned from the slap-dash scrawl of your male correspondent—with excuses at the beginning and haste at the end, and too often nothing between but sweeping generalities—to the well-filled sheet of your female friend, with plenty of time bestowed and no paper wasted, and overflowing with those close and lively details which show not only that observing eyes have been at work, but one pair of bright eyes in particular? (Elizabeth Eastlake Citation1845, 98)

The article, titled “Lady Travelers” praises the observational skills of women, travelling alongside their male companions to foreign countries, in search of artistic novelties (Hilary Fraser Citation2014, 68). It is interesting to note here how the “female eye” and the concern for detail already suggested by Kant, Schopenhauer, and Ruskin are not dismissed as misogynistic conjecture. Rather, it is reinforced but acquires a positive connotation. Women’s explorative eyes are trained in the “familiar scene” are juxtaposed with the—rather lousy-ones of men. The terms are inverted, but the domain of each gender in the visual perception of art remains expressed in binary terms, in accordance with the stark separation of the male and female social spheres in everyday life.

Sex, sexual attraction, and the male gaze

Since the 1970s, feminist critique pointed to another factor involving the gender-based polarization of perception when looking at Western art. From the Renaissance to the end of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, the artistic genre of the nude has appealed to the senses of heterosexual men. With Giorgione’s and then Titian’s Venus (respectively, 1507–10 and 1535), the theme of the Venus Naturalis or the depiction of physical love takes over the pictorial tradition and transforms the way the female body is portrayed till the present day: sensuous, and available (Kenneth Clark Citation1956, 114–117). Conversely, the heterosexual female perception of male nudity finds virtually no space in art production, and consequently in our museums. Even when women were accepted into art academies, they were denied access to life-drawing classes involving male models till the late 19th century. Therefore, historically, sensual representations of the male body are rare, and they are, with a few exceptions, created by male artists and are not primarily meant to be gazed at by heterosexual female viewers (Tamar Garb Citation1993, 36).

This idea of a “male gaze” has meanwhile become an established concept, popularized by Laura Mulvey in a 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (Laura Mulvey Citation1975). The term “male gaze” is used to explain the sexualizing attitude of the heterosexual male and how it has shaped the Western representation of the female body Much of western art depicting women can be regarded as an erotic invitation to heterosexual men, whereas the same cannot be said regarding representations of men for heterosexual women:

One might simplify this by saying: men act, and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women, but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus, she turns herself into an object—and most particularly in an object of vision. (John Berger Citation1972, 47)

The term male gaze does not refer to an empirical phenomenon, nor does it predict where the viewers’ gaze will linger, or how images are interpreted by specific individuals. Rather, it refers to the response that images in the western tradition prescribe to their viewers. It identifies the “ideal viewer” of art with the heterosexual male. This seems to largely apply to the artistic production of male artists between the sixteenth and the twentieth century.

The sexualized representation of bodies, and specifically of the female body, has therefore been ascribed the potential to create a general perceptual divide through not only gender identity but also sex and sexual orientation; between the male, specifically the male heterosexual audience, who can more easily identify with their “ideal viewer,” and the perception of women, who can identify with the passive object in the image but must shift their attitude to appreciate the (male-made) work of art (Carolyn Korsmeyer and Brand Weiser Peg Citation2021).

Concluding remarks on the historical study

Art perception has been theorised to be gender-shaped or at least gender-informed in historical writing; as the cited sources highlight, different aspects of gender have been considered in building up such discourses. These span from gender identity, intended as the self-affirmation of social role and its expectations, to the sexual attraction of the heterosexual man towards the depicted female nudity, to the sexual identity of the female viewer identifying depicted sexual characteristics as her own. Even if the aspects taken into account are multiple, the sources agree in delineating binary differences, between cisgender heterosexual men and women, in the act of looking at art and in the derived experience.

While it is not possible to empirically assess whether the historical viewer could experience any of the differences described by literature, we do have the means to test the contemporary viewer. In fact, psychological studies on perception often employ gender as a binary variable to define opposite groups of viewers.

Method 2) experimental study

Gender as a binary variable

Psychologists have conducted several studies on gender-related differences in visual perception. Ayako Miyahira, Kiichiro Morita, Hiroshi Yamaguchi, Kensaku Nonaka, and Hisao Maeda (Citation2000) monitored the exploratory eye movements of two groups of subjects, divided by gender into a male and female group of 39 participants each. They recorded the number of gaze points (fixations >0.2 seconds) as well as gaze duration during the observation of a face and complex scenes (10–15 seconds per stimulus). The study found that women exhibited a longer mean gazing time, with fewer gaze points, than men. This, however, was true only for adult participants, whereas sub-groups of children and elderly participants did not report significant differences. The authors thus conclude that visual information processing may be regulated by gonadal hormones.

More recently, Sargezeh, Tavakoli & Daliri (Bahman Abdi Sargezeh, Niloofar Tavakoli and Mohammad Reza Daliri Citation2019) examined the viewing behaviour of two groups divided by sex, men and women, looking at photographs of indoor environments, monitoring among other things the number of fixations, fixation duration, number of saccades, and saccade amplitude. They found significant differences between groups: women performed larger saccades (eye movement from one fixation point to another) which the authors interpreted as a more explorative gaze behaviour. Moreover, the authors speculated that women tend to inspect images faster than men, due to the ratio of fixation duration/saccade duration, i.e., shorter fixations and longer saccades. This experiment involved a sample of 25 men and 20 women.

A second stream of research has investigated how we behave when we are confronted with images of people. Valuch Christian, Lena S Pflüger, Bernard Wallner, Bruno Laeng and Ulrich Ansorge (Citation2015) recorded the eye-movements of 40 participants looking at “masculine” and “feminine” faces: their data suggested that men’s attention is more effectively captured by feminine faces and that generally men and women differ in how fast their eye-movements are depending on the gender of the face shown. Antoine Coutrot, Nicola Binetti, Charlotte Harrison, Isabelle Mareschal and Alan Johnston (Citation2016) examined the eye-movements of 405 participants watching videos of another person, reporting not only that woman performed more explorative gaze movements but also that they appeared to look more at the left eye of female actresses in the film.

Several studies have confronted the viewing behaviour of heterosexual men and women when looking at sexualized characters, mainly in ambient photographs. In a literature review conducted on the topic, Rupp & Wallen (Heather A. Rupp and Kim Wallen Citation2008) report that men’s viewing behaviour seems to be dependent on the sex depicted in photographs, while contextual factors may have a higher impact on women. Studies in biopsychology suggest that the duration of viewing time could be an indicator of sexual attraction as far as heterosexual men are concerned (Charlotte Hall, Todd Hogue and Kun Guo Citation2011, Meredith L Chivers, Gerulf Rieger, Elizabeth Latty and J Michael Bailey Citation2004).

Importantly, the studies discussed above do not mark a distinction between sex-linked traits (e.g., hormonal exposure) and gender ones (culturally shaped roles). When gender is considered a variable, it is mostly framed as a combination of the two. Interestingly, while all tested groups were defined based on self-assessed gender, the difference in results was often explained by bringing hormonal traits into the picture, with little consideration of cultural notions that could shape gender itself. For instance, Hall, Hogue, and Guo (Citation2011) suggest that women´s heterogeneous eye-movement behaviour could be impacted by fertility levels, making more fertile women more inclined to “visually assess their competitors,” a behaviour not mirrored in men.

On the basis of the cited literature, two assumptions can be made about visual perception: firstly, that the experience of one’s own gender, sexual orientation, and/or sex-linked traits informs our visual experience; secondly, that individuals whose gender and sex are not explicitly in conflict with prevalently binary societal norms (heterosexual cisgender individuals) have displayed an eye-movement behaviour which can be described as binary.

These remarks apply to the non-aesthetic or common visual experiences—while experimental investigations in the visual experience of art exist, they have not, so far, tested gender-based differences at the level of eye movements. Different methods have been employed, producing varied outcomes; Camilo J Cela-Conde, Francisco J Ayala, Enric Munar, Fernando Maestú, Marcos Nadal, Miguel A Capó, David Del Río et al. (Citation2009) studied the brain activity of people looking at both artistic and non-artistic pictures and revealed through magnetoencephalography some variations in the location of brain activity between men and women. Specifically, parietal brain regions reported different activity when stimuli were judged as “beautiful” by the participants: activity was bilateral in women and lateralized to the right hemisphere in men. Martin Tröndle, Volker Kirchberg and Wolfgang Tschacher (Citation2014) analysed the experience of art in the museum setting by providing their participants (n 576) with data gloves, which measured location, as well as heart rate, and skin conductance level during the museum visit (approximately 30 min per participant). Seven out of 70 works in the exhibitions elicited different responses (walking behaviour, skin conductance, and heart rate) between men and women, although no common characteristic could be found among them. Observation time was reported to be very similar between the two groups. This literature, much like the above-cited research on visual perception, suggests that artworks could elicit a gender-based binary response at the level of eye movements—yet to this day, this has not been tested with eye-tracking technology.

Research question and hypotheses

Summing up, our literature review has uncovered several open issues:

There is a large body of literature describing the act of looking as subjected to binary difference. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this ascribed different innate “perceptual abilities” to men and women. From the twentieth century onwards, in an effort made to overcome the patriarchal limits of traditional aesthetic philosophy, feminist literature has rather focused on a gendered “divide” in art making and perception. However distant these two traditions are in aims and scopes, they reflect a long-lasting discourse that sees sex, gender identity, and sexual orientations as factors that can be used to make a distinction between viewers and that likely inform the viewing experience of art. Yet, to this day, this discourse remains theoretical, with no empirical support.

Gender has been used as a discrete variable in testing the visual perception of photographs and natural scenes. Differences in eye movements have been attributed to gender, although it is unclear if these results are attributed to sex and sex-linked traits such as hormonal levels, whether they are culturally and socially driven, or a combination of the two.

While some empirical evidence exists on art perception, eye-tracking was not employed to test whether sex, gender identity, and/or sexual orientation inform or shape the perception of art.

We, therefore, designed two eye-tracking experiments to verify whether gendered differences can be detected when looking at art and if they can be described as binary at the level of eye movements. Our definition of gender for this scope included the three separated variables of sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation; the separation was designed to allow for repeated testing with different variable combinations if necessary.

The first experiment was intended to test potential differences that, as described in eighteenth and nineteenth-century aesthetic writings, occur when men and women look at all artworks but especially complex ones. Women have traditionally been ascribed a behaviour which is associated with acute attention to detail; men, on the other hand, a behaviour indicating a more thoughtful, but less detailed elaboration of the visual stimuli. Therefore, we designed an experiment comprising paintings varying in subject and style to test whether any gender-based difference could be monitored in the number, duration, or concentration of fixations, as well as in the amplitude of saccades.

Experimental investigations on visual attention have shown that women can perform larger scan paths, as well as shorter fixations when looking at interior scenes. This is exactly the opposite of the aesthetic theories from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that assumed that women concentrate more on details. We, therefore, assumed that there is no gender-specific visual behaviour in regard to paintings of different subjects, styles, forms, and sizes. Our first hypothesis was that the stimuli included in Experiment 1 would not elicit unified differences in eye movements according to gender.

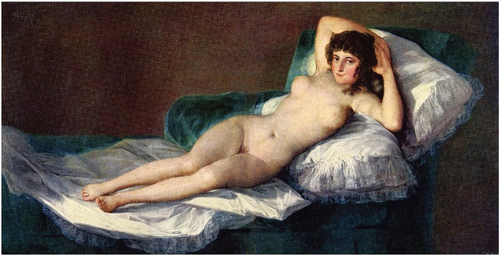

The second experiment focused on differences that might be triggered by specific contents of the artworks; this was to test the hypothesis of the gendered divide within the perception of western art at the eye-movement level. Therefore, we presented paintings exhibiting clothed and nude male and female figures. Approximately half of them showed explicit sex-linked traits (as ), and the other half shown in similar positions, with no visible sex-linked traits (as ). Given, the psychological literature that underlines sexual attraction as a factor for the viewing experience, we hypothesized gender-based differences between participants, especially in the concentration of fixations on specific parts of the paintings, but only when viewers were confronted with sexually explicit figures.

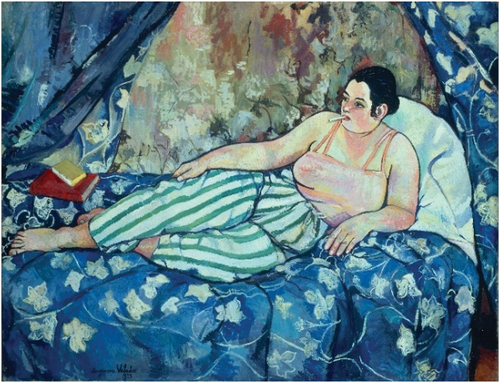

Figure 2a. Suzanne Valadon, the Blue Room (1923), oil on canvas, 90 × 116 cm, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou Paris.

Figure 1a. Francisco de Goya, La Maja desnuda (1795–1800), oil on canvas, 94,7 × 188 cm, Museo del Prado.

Figure 1b. Anne Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, the Sleep of Endymion (1793), oil on canvas, 198 × 261 cm, Musée du Louvre.

To summarize, we hypothesized that no binary, gender-based differences could be monitored in viewing behaviour for general paintings (Experiment 1). However, we expected to find differences between the participants for sexually explicit paintings (Experiment 2).

Experiment design

Eighty-four participants between the age of 20 and 35 were recruited via a public notice board: we advertised two experiments as a study on art appreciation. Participants were aware that their eye movements would be recorded, but they were not informed of the aim of the study until after both experiments had been completed. Each participant received 15€ for their participation. To avoid bias linked to art expertise, we excluded students of art or art history and art experts. In case of visual impairment, correcting contact lenses were allowed. Participants wearing glasses were excluded to ensure a higher level of precision since the reflection of some lenses was observed to disrupt the recording procedure.

In the first part of the study (Experiment 1), we presented a randomized sequence of 14 pictures to each participant for 60 s. The selection of stimuli represented different art historical genres: four history paintings, four genre paintings, three landscape paintings, and three still lives. Stimuli varied stylistically, including paintings produced between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. They also varied semantically, i.e., in subject matter, including paintings with and without human figures—images of women, men, and children, interior scenes and landscapes, compositions with fruit, and animals. The variety reflected the aim of monitoring viewers’ responses to artworks, independently from content or style.

In the second part (Experiment 2), we showed each participant 24 pictures for 20 s each, again in a randomized order. Unlike the first, the second experiment was designed to monitor differences in oculometric parameters according to the content of the pictures—clothed and nude paintings of men and women. We selected stimuli showing one main figure at the centre of the composition. Of these stimuli, 12 presented male figures and 12 female figures; 13 were explicitly showing sex-linked traits; 11 others were not. A list of all the stimuli (and relative abbreviations for analysis purposes) can be found in the Appendix.

During both parts of the experiment, we recorded eye movements with the eye tracker iView X RED 5 by SMI, recording at 120 Hz.

After the two series of images, each participant was presented with a questionnaire and asked to declare their sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

Data preparation

Assuming that the strongest possible binary difference in the data should be observed between two groups of heterosexual cisgender men and women, we first defined two groups based on participants’ questionnaire responses.

This resulted in a sample of 56 participants (29 heterosexual cisgender men and 27 heterosexual cisgender women). In case of a detected binary difference, we envisioned a second round of analysis to test whether this would vary along with one of the three variables; as the results of the study will show, however, this proved to not be necessary.

Eye movement data were pre-processed and analysed with the Eyetrace software (Kübler et al., Citation2015). In order to detect any differences between the two groups of participants, we analysed a) the number of fixations, the duration of fixations, the saccade amplitude, and the scanpath length, b) the distribution of fixations on overall painting (heatmaps), c) the distribution of fixation on each part of the painting (fixation maps or grid method), and d) the entropy of fixations.

Data analysis

Overall descriptive eye-movement statistics

First, we calculated the number of fixations and the amplitude of saccades for each painting and each subject. Fixation duration was approximated from the total viewing time and number of fixations. Based on saccade amplitude, we then calculated two measures: the average saccade amplitude and the total length of the scan path for each trial. Next, we averaged across stimuli to obtain an average measure for each participant. While all stimuli of Experiment 1 were grouped together, the stimuli of Experiment 2 were divided between those showing female figures and those showing male figures. Independent samples t-tests compared male and female participants for each group of paintings separately (See results ). We report Cohen’s d as a measure of the effect size.

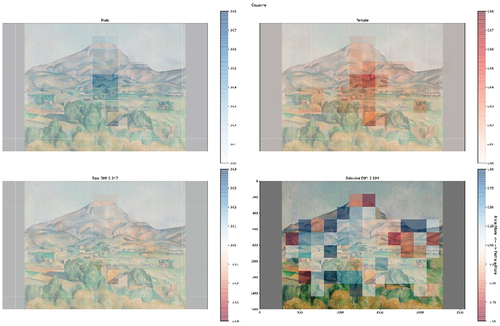

Distribution of Fixations: Heatmaps Comparisons

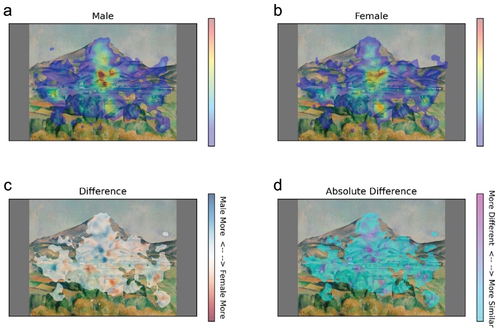

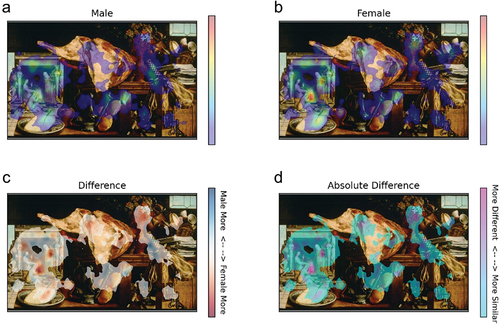

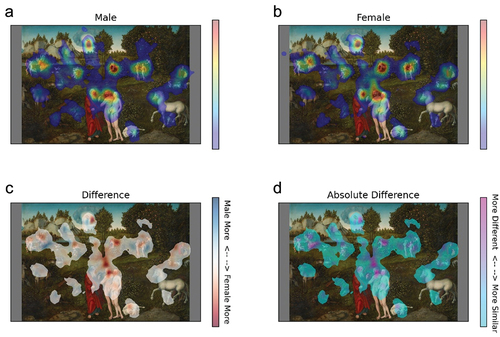

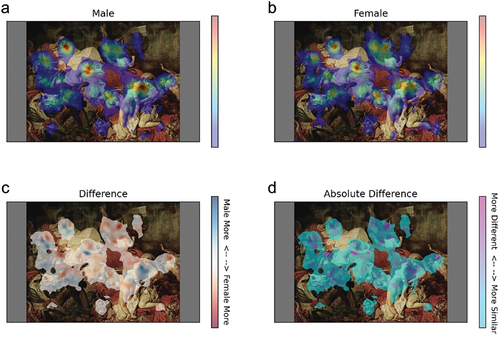

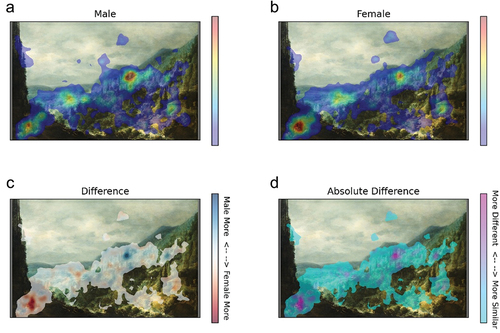

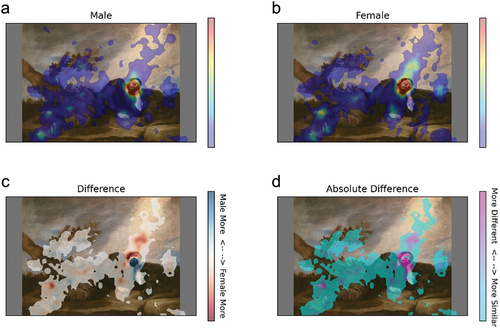

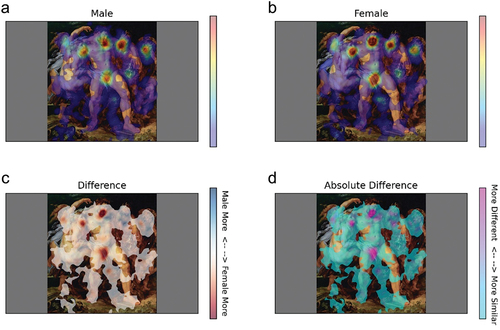

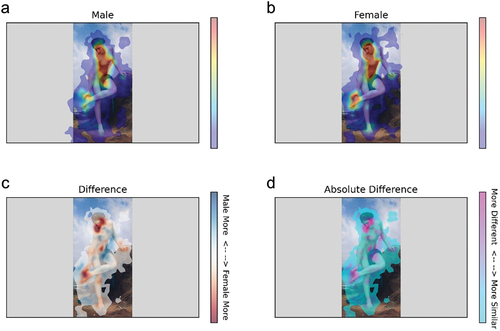

In order to obtain a heatmap of fixations for each painting separately for both experiments, we averaged fixations across participants pixel-by-pixel for each group separately. Next, we used a Gaussian filter with a standard deviation of 25 pixels to smooth the fixations, to obtain an overall heatmap for the male () and female () groups. To visualize gender-based differences, we subtracted the female from the male average heatmap, thereby visualizing areas that are more often fixated by male and female participants separately (). Finally, to see which areas are the most different between the groups, we have taken the absolute value of the differences (). For visualization purposes, we truncated the minimum and maximum values of the saliency maps between 70% and the 99.5% percentiles of the distribution.

Distribution of fixations: fixation map comparison (grid method)

With this analysis, our goal was to measure how similar the distribution of fixations was, between the groups locally compared to each part of each painting. In order to do this, we covered the image area with a grid of rectangles and calculated the fixation probability within each cell of the grid for each painting and each participant. To obtain an average fixation grid for each painting, we averaged the fixations grids across male and female participants. To calculate the difference in these fixation maps, we calculated the mean absolute difference between each cell of the average male and female fixation distributions for each painting. We repeated this process with 12 different grid resolutions: from 6 × 4, up to 24 × 15 (horizontal*vertical cells).

To test whether the calculated differences were statistically significant, we used a permutation test. Due to multiple comparisons, we only report differences as significant if p < .01. To visualize differences between the male and female groups, we produced an overlay 16 × 10 grid, colour-coded (blue: more male fixations, red: more female fixation, white: no difference). To calculate the relative difference between the male and female fixation probability locally, we calculated the difference between the median fixation probability of males and females for each cell and divided it by the median fixation probability of that cell (see example ).

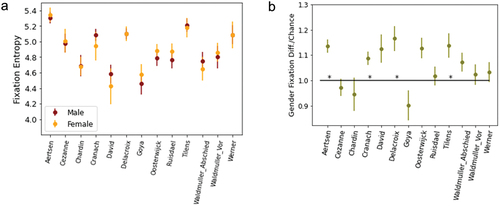

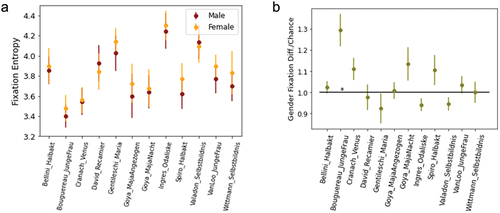

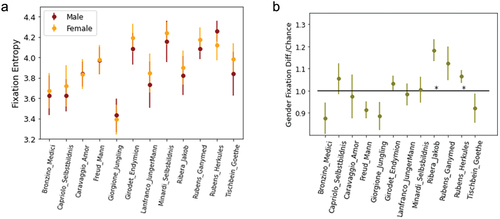

Entropy

Additionally, we calculated how focused or scattered the distribution of fixations was for the whole image. Mathematically, this can be described as the level of entropy—low entropy: focused fixations, high entropy: scattered fixations. To this end, we calculated the natural logarithm-based entropy of each fixation probability grid (as described in the previous section), for each participant and painting, and compared the average entropies obtained for male and female participants with an independent samples t-test.

Results

Overall eye-movement statistics

We compared the number of fixations and fixation duration between the groups of both experiments by separately assessing the female and male paintings in Experiment 2. We found no significant differences in these comparisons (Exp 1: t = 0.05, p = 0.959; Exp 2 female subject: t = 0.36, p = 0.7185; Exp 2 male subject: t = 0.60, p = 0.5511). Similarly, we compared the average saccade amplitude (Exp 1: t = 0.33, p = 0.7406; Exp 2 female: t = 0.58, p = 0.5649; Exp 2 male: t = 0.001, p = 0.9991) and the total scanpath lengths (Exp 1: t = 0.12, p = 0.9078; Exp 2 female: t = 0.67, p = 0.5056; Exp 2 male: t = 0.06, p = 0.9536) across groups, and again we found no significant differences. Finally, we compared the fixation entropy between groups, and again, we found no significant differences (Exp 1: t = 0.63, p = 0.5294; Exp 2 female: t = 0.34, p = 0.7354; Exp 2 male: t = 0.5, p = 0.6155). There is, hence, no difference in the overall distributed vs. focused nature of fixations between the groups. To summarize, general descriptive statistics of eye-movements do not show any gender-based differences.

While there were no overall differences in the descriptive statistics of eye-movements, we could still expect to find local effects: gender-based differences in the frequency of fixating different parts of the stimuli (as visualized by heatmaps and quantified by grid-based comparisons) or differences in fixation distribution for certain paintings (as measured by the entropy).

Quantitative fixation map (grid method) and entropy

Experiment 1: We found no differences in entropy for any of the paintings in Experiment 1 (). Comparisons between fixation maps generated with the grid method showed significant, though small, differences between the groups, but only for 4 out of 14 paintings (by Aertsen, Cranach, Delacroix, and Tilens) existed ().

Experiment 2: There was no significant difference in entropy for any of the paintings (). In the comparison of the fixation maps (grid method), we found a significant difference only for Bouguereau (t = 3.39, p=.006; ), Ribera (t = 3.75, p=.003), and Rubens´ Hercules (t = 3.4, p = 0.006; ). Note that a significant difference cannot arise due to a chance difference with an arbitrary grid division, but only if it is consistently present using multiple grid resolutions.

Discussion

Understanding the results

Experiment 1 presented a broad variety of paintings. We did not find any overall significant differences in any of the oculometric parameters: neither in fixation number, nor in fixation duration, saccade amplitude, and scanpath length between the groups of cisgender, heterosexual male and female viewers. Small significant differences in both fixation location and entropy between groups of viewers were found for 4 out of 14 paintings: a Vanitas still life by Pieter Aertsen with Christ, Mary and Martha (: women observe the women in the background and the flowers in the foreground longer), Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden by Cranach the Elder (: women look longer at some of the figures), The Death of Sardanapalus by Eugène Delacroix (: the two groups slightly differ in which parts of the figures they concentrate on), and a Mountain Landscape by Jan Tilens (). While it may be interesting to investigate why these differences exist, we can confidently conclude based on the majority of the paintings and the minor differences in the four mentioned that there is no systematic difference in generally viewing patterns of the gender groups.

We had expected that based on a diverse selection of paintings there would be no overall, gender-based binary differences in viewing patterns and Experiment 1 confirmed this expectation. The results of Experiment 2 were more surprising. Half of the paintings in this experiment were chosen for their explicit sexualised content. We expected clear differences between groups of cisgender heterosexual male and female viewers when looking at the sexually explicit stimuli of the same vs. opposite gender. However, in this experiment, we also did not find any statistically significant differences between the two groups. Some differences in the locations of fixations were observed, but only for 3 out of 24 paintings: After the Bath, by William Adolphe Bouguereau (); Jusepe de Ribera’s Jacob’s Dream (), and Peter Paul Rubens Hercules ().

Differences that we expected in regard to explicit images were only low: for Rubens’ Hercules (women were looking for longer to the drapery concealing his pelvic area), and for Bouguereau (men were looking longer to the drapery concealing the women’s pelvic area). If this result was consistent across paintings we could attribute it to sexual attraction—however, other sexually explicit images did not report any similar gender-related differences (see ).

Bouguereau’s was the only picture depicting a female nude which was looked at differently between the groups of male and female viewers (). As better shown by the heatmap, the most striking difference occurs in correspondence of the subject 's face, stomach, tigh, and left foot. Interestingly, other paintings included in the experiment present nudity and explicit sex-linked traits—the fact that they did not make a difference in the way they attracted attention could hence be related to the mode of representation or to the composition of the image. This remains to be tested in future studies.

Conclusions

The goal of this transdisciplinary study was to answer the question of whether and how gender informs, shapes, or influences the perception of art. On the one side, we provided an analysis of historical literature and showed that difference is often described as binary: theories polarized viewers into two opposite spheres, “the male” and “the female,” generally without further reflecting on whether such a distinction is based on biological sex, gender identity, and/or sexual orientation, and without delivering any empirical proof for the assumption of such polarization. On the other side, we studied for the very first time gender differences in art perception experimentally, on the most fundamental level of eye movements. The results show that a binary classification of viewers based on sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation does not justify any polarization of eye-tracking results. Looking at digital reproductions of paintings, self-declared heterosexual, cisgender women did not display a behaviour which could be described as consistently different from that of heterosexual, cisgender men. Remarkably, even the representation of explicitly sexualized, naked figures did not create a perceptual divide between heterosexual men and women.

Altogether, our results are in accordance with Korsmeyer and Peg’s (Citation2021) statement: “Sometimes a facile reading of the gaze tempts one to exaggerate the sharpness of gender distinctions into the male viewer and the female object of the gaze, though most feminists avoid such over-simplification.”

In both reviews cited at the beginning of this paper, A.W. Eaton devotes a section to two types of feminist engagement with aesthetics and art perception, as well as artistic practice and its history. She defines them as “Humanism” and “Gynocentrism”; the first direction seeks to explain the exclusion of women and non-cisgender artists from the canon, as well as eventual gender-correlated differences, with social mechanisms of exclusions reproduced in history. According to this view, in absence of a patriarchal social structure, women would have achieved the same canon of production and appreciation as men. A gynocentric approach, on the other hand, sees gender as a fundamental differentiating factor in the production and reception of art. According to a gynocentric view, in the absence of a patriarchal social structure, women would nonetheless have developed a parallel canon of art perception and production, according to their fundamentally female experience of the world (Eaton Citation2021, 12). The result of our experiment shows that there appears to be no coherent way of monitoring a female experience even within a heterosexual cisgender group—suggesting that a gynocentric approach to art viewing would not be supported by empirical evidence. This can be interpreted as an important indicator: that fundamental categories, based on gender alone and detached from social mechanisms, are not suitable to describe art perception. Our findings caution against the use of over-simplified gender groups in experimental studies, evidencing the need for more meaningful categories to describe art viewers and their behaviour.

Future research directions and limitations

Our literature review has brought together a historical discourse and a body of empirical research; we have then attempted to fill an evident gap in both directions. As a byproduct, the present study has also underlined the differences between the two cultures: on one side, a philosophical/literary one that has so far treated gender from different perspectives in its multifaceted nature (to the point of questioning its validity altogether); on the other, a strictly experimental one which needs to rely on discrete categories and consequently has so far treated “gender” as such. Our experiment wanted to build on the existing experimental discourse but also take into account a more nuanced understanding of “gender,” in order to form the basis for further and more refined experimental investigation, establishing a dialogue between these two cultures.

In order to do this, we decided to maintain discrete categories but assessed participants by biological sex, gender identity, and sexual preference so that at least these variables would be considered as equally relevant in the definition of a gender category. Our results are to be interpreted as groundwork for future study, as they evidently call for more research in the same direction; first of all, several experiments would be necessary to assess whether any difference, binary or not, could be detected if a different combination of these three variables was to be tested—e.g.) grouping participants by biological sex only, including multiple gender identities within the same group, or vice versa. Furthermore, the results also seem to underline that even within groups of cisgender, heterosexual participants, visual perception is extremely individual, suggesting that gender-related variables could be secondary to more specific ones: hormonal traits and age groups, but also aspects of cultural upbringing and education, types of media consumed, affective states and more.

The study was performed in Vienna, with a sample of young participants who were mostly white, German-speaking university students. Social and economic conditions and cultural upbringing were not considered as variables and as such one can argue that the results are limited and do not reflect the experience of a large portion of the population. This is true, and it calls for studies of the same nature with a different pool of participants, and especially those whose ideas on gender have been shaped by different cultural traditions.

Finally, the study only reports the behaviour of the contemporary viewer. It is possible that different results would have been yielded by a group of nineteenth-century viewers, given that gendered expectations have changed over time. Our findings can therefore be interpreted as a challenge to the perpetuation of inherited categories such as gender binarity, which, despite their historical replication, may not fully align with our contemporary behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Mario T. Thalwitzer for initiating the research behind this study as well as Hamida Sivac and Seda Pesen for their comments and suggestions. We thank the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, grant P25821) for supporting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Berger, John 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

- Burke, Edmund 1757. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Idea of Sublime and Beautiful. London: R.J. Dodsley.

- Cela-Conde, Camilo J., Francisco J. Ayala, Enric Munar, Fernando Maestú, Marcos Nadal, Miguel A. Capó, David Del Río, et al. 2009. “Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in the Neural Correlates of Beauty.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (10): 3847–3852. 10.1073/pnas.0900304106

- Chivers, Meredith L., Gerulf Rieger, Elizabeth Latty, and J. Michael Bailey. 2004. “A Sex Difference in the Specificity of Sexual Arousal.” Psychological Science 15 (11): 736–744. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x

- Christian, Valuch, Lena S. Pflüger, Bernard Wallner, Bruno Laeng, and Ulrich Ansorge. 2015. “Using Eye Tracking to Test for Individual Differences in Attention to Attractive Faces.” Frontiers in Psychology 42 (6): n.p. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00042

- Clark, Kenneth 1956. Venus. In the Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton: Princeton Univeristy Press.

- Coutrot, Antoine, Nicola Binetti, Charlotte Harrison, Isabelle Mareschal, and Alan Johnston. 2016. “Face Exploration Dynamics Differentiate Men and Women.” Journal of Vision 16 (14): 1–19. doi:10.1167/16.14.16

- Eastlake, Elizabeth 1845. “Lady Travelers.” Quarterly Review 76: 98–137.

- Eaton, A. W. 2008. “Feminist Philosophy of Art.” Philosophy Compass 3 (5): 873–893. doi:10.1111/j.1747-9991.2008.00154.x

- Eaton, A. W. 2021. “Feminist Aesthetics.” In The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Philosophy, edited by Kim Q. Hall and Ásta, 295–311. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fraser, Hilary. 2014. Girl Guides: Travel, Translation, Ekphrasis. In Women Writing Art History in the Nineteenth Century: Looking Like a Woman, 62–98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Garb, Tamar 1993. “The Forbidden Gaze: Women Artists and the Male Nude in Late Nineteenth-Century France.” In The Body Imaged: The Human Form and Visual Culture in the Renaissance, edited by Kathleen Adler and Marcia R. Pointon, 33–42. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Goldthwait, John T., ed. 1991. Kant’s Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Hall, Charlotte, Todd Hogue, and Kun Guo. 2011. “Differential Gaze Behavior Towards Sexually Preferred and Non-Preferred Human Figures.” The Journal of Sex Research 48 (5): 461–469. doi:10.1080/00224499.2010.521899

- Korsmeyer, Carolyn, and Brand Weiser. Peg. 2021. “Feminist Aesthetics.” InThe Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/feminism-aesthetics/

- Kübler, Thomas C., Katrin Sippel, Wolfgang Rosenstiel, Enkelejda Kasneci, Wolfgang Fuhl, and Guilherme Schievelbein. 2015. “Analysis of Eye Movements with Eyetrace.” In 8th International Joint Conference, BIOSTEC, Lisabon, Portugal, January 12–15.

- Miyahira, Ayako, Kiichiro Morita, Hiroshi Yamaguchi, Kensaku Nonaka, and Hisao Maeda. 2000. “Gender Differences of Exploratory Eye Movements a Life Span Study.” Life Sciences 68 (5): 569–577. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00963-2

- Mulvey, Laura 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16 (3): 6–18. doi:10.1093/screen/16.3.6

- Nochlin, Linda. 1971. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, edited by Vivian Gornick and K. Moran Barbara, 480–510. New York: Basic Books.

- Palmer, Caroline Elizabeth. 2009. “Women Writers on Art and Perceptions of the Female Connoisseur, 1780-1860.” Ph D. diss, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

- Rupp, Heather A., and Kim Wallen. 2008. “Sex Differences in Response to Visual Sexual Stimuli: A Review.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 37 (2): 206–218. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9217-9

- Ruskin, John 1900. “Of Queens’ Gardens.” In Sesame and Lilies, edited by A.B. Agnes Spofford Cook, 72–105. New York: Silver, Burdett and Company.

- Sargezeh, Bahman Abdi, Niloofar Tavakoli, and Mohammad Reza Daliri. 2019. “Gender-Based Eye Movement Differences in Passive Indoor Picture Viewing: An Eye-Tracking Study.” Physiology & Behavior 206: 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.03.023

- Schopenhauer, Arthur 1990. “The Weakness of Woman.” In History of Ideas on Woman: A Source Book, edited by Rosemary Agonito, 191–230. New York: Perigee Books.

- Tröndle, Martin, Volker Kirchberg, and Wolfgang Tschacher. 2014. “Subtle Differences: Men and Women and Their Art Reception.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 48 (4): 65–93. doi:10.5406/jaesteduc.48.4.0065

Appendix

List of Stimuli

Experiment I

Pieter Aertsen, Vanitas (1552)

Jean Simon Chardin, The ray (1727)

Maria van Oosterwijck, Vanitas (1668)

Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire (1895)

Jacob van Ruisdel, The Windmill of Wijk bij Duurstede (c. 1670)

Jan Tilens, Mountain Landscape (1610)

Francisco de Goya, Blind Man’s Bluff (1788)

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Parting of the Parents (1854)

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Early spring in Wienerwald (1861)

Arthur Alexander von Werner, Im Etappenquartier von Paris, (1894)

Jan Breughel the Older and Peter Paul Rubens, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Men (1617)

Lucas Cranach the Older, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (1530)

Jacques-Louis David, the Oath of the Oratii (1784)

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus (1827)

Experiment II

Female figures

Giovanni Bellini, the young woman at her Toilette (1515) (explicit)

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, After the bath (1875) (explicit)

Lucas Cranach the Older, Venus (1532) (explicit)

Jacob van Loo, Young woman Going to Bed (c.1650) (explicit)

Jacques-Louis David, Portrait of Mme Récamier (1800)

Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Great Odalisque (1814) (explicit)

Suzanne Valadon, The Blue Room (1923)

Orazio Lomi Gentileschi, The Penitent Mary Magdalene (c. 1622) (explicit)

Francisco de Goya, La Maja vestida (1800–1807)

Francisco de Goya, La Maja desnuda (1795–1800) (explicit)

Karoline Wittmann, Self-portrait with Apple and vinegar jug (1948) (explicit)

Eugen Spiro, Nude at the Toilette (1930) (explicit)

Male Figures

Lucian Freud, man with Leg up (1992) (explicit)

Giorgione, Portrait of a Young Man (Antonio Brocardo) (1508–10)

Peter Paul Rubens, Ganymed (1611) (explicit)

Peter Paul Rubens, The Drunken Hercules (c. 1611)

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Cosimo de Medici as Orpheus (1537)

Domenico Caprioli, Self portrait (1512)

Tommaso Minardi, Self portrait (1803)

Caravaggio, Amor Vincit Omnia (1602) (explicit)

Jusepe de Ribera, Jacob’s dream (1639)

Anne Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, The Sleep of Endymion (1793) (explicit)

Johan Heinrich Wilhelm, Goethe in the Roman Campagna (1787)

Giovanni Lanfranco, Young Man Lying on a Bed with Cat (1620)