ABSTRACT

This article centres on students’ experiences and recommendations regarding how Canadian secondary schools can enhance the critical consciousness of young people about gender-based violence (GBV). We describe findings from three participatory art-based workshops with adolescents in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Nova Scotia. When asked what they wanted teachers to know when teaching about GBV issues, participants expressed the importance of strong teacher-student and student-student relationships, approaching GBV education in ways that addresses its scope, root causes, and impact on survivors, imparting practical knowledge for GBV prevention, response, and resistance, and providing students opportunities for agency and leadership. Findings were situated within a feminist intersectional lens and indicated that adolescent girls continue to live with GBV, experiencing harassment, discrimination, and discomfort and that, for Indigenous girls, experiences of GBV were compounded by racist and colonial violence experienced in and out of school. These experiences of violence contradicted the safe and caring learning environments that participants called for.

Introduction

In developing strategies for effective pedagogical approaches for teaching about sensitive subjects with broad social implications such as gender-based violence (GBV), student perspectives are not always sought. Yet student perspectives should be forefront in this research, as they are directly experiencing classrooms where these social issues are (or are not) addressed. The concept of student voice is built on the understanding that young people have unique and valuable perspectives, which should not only be heard but also responded to by adults, and that they should be given ‘opportunities to actively shape their education’ (Cook-Sather Citation2006, 359–360). Recognising the value of student voice in influencing schools does not mean that students’ perspectives are the only or even the most important perspectives, but that those who seek to enhance education quality can benefit from consulting and listening to students (Flutter and Rudduck Citation2004). Bourke and Loveridge (Citation2018) identify listening to students as an educational, social, and political imperative for three reasons: a) they have a right to have their voices considered in decisions that affect them; 2) it helps them enhance their sense of identity and to know themselves; and 3) it is an effective means of ensuring policy and practice responds to the needs and interests of young people.

In this article, students’ experiences and recommendations are centred in examining how Canadian secondary schools can enhance the critical consciousness of young people about GBV. We describe findings from three participatory art-based workshops with adolescents in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Nova Scotia. Following an introduction to key concepts related to GBV, participants across all groups emphasised the importance of learning about GBV issues through formal education, but expressed that, in their experience, it had usually not been taught in ways they felt were sufficiently holistic, when they had learned about it at all. When asked what they wanted teachers to know when teaching about GBV issues, participants expressed the importance of strong teacher-student and student-student relationships, addressing GBV in ways that address the scope and root causes and its impact on survivors, and providing students opportunity for agency and leadership, including the choice to opt out of lessons that they think may be (re)traumatising, reflecting the reality that GBV, harassment, and discrimination already permeate much of their lives.

Given the importance of recognising and wrestling with researcher positionality that is well established in feminist qualitative research (e.g., Olukotun et al. Citation2021), we briefly describe some of the most prominent facets of our socio-political locations and identities. This article’s co-authors are but two members of the research team who have contributed to this project. Catherine has led the project from its inception; she is a White cisgender heterosexual woman newly appointed to a faculty position at an Ontario university. Salsabel joined the project in a later stage; she is a woman of colour, middle-school teacher, teacher educator, and sexual violence prevention educator and researcher.

GBV in Canada

GBV is defined as ‘violence that is committed against someone based on their gender identity, gender expression, or perceived gender’ (Cotter and Savage Citation2019, n.p.). It is a continuum that encompasses various attitudes and behaviours, is rooted in systemic inequities, and is experienced differently across intersecting identities and communities. Trudell and Whitmore’s (Citation2020) national survey demonstrated that GBV in Canada has been exacerbated significantly by the COVID-19 pandemic. Women and girls, especially those who are Black, Indigenous, racialised, LGBTQ+, and gender-nonconforming are often the most vulnerable (Cotter and Savage Citation2019). Indigenous women and girls are among the most likely to experience GBV (Conroy and Cotter Citation2017) and are tragically missing and murdered at what Anaya (Citation2013) calls ‘epidemic rates’ (9), a phenomenon referred to as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

GBV has been widely documented in Canadian schools. LGBTQ+ students across Canada reported experiencing homophobic and transphobic comments, verbal harassment, physical harassment, and sexual harassment, and the majority experienced school as unsafe, experiences that were compounded for non-White LGBTQ+ students (Peter, Campbell, and Taylor Citation2021). Highly prevalent forms of GBV that are not always recognised as gender-based include bullying and cyber-bullying (Greene et al. Citation2012; Pepler and Milton Citation2013). GBV has harmful impacts on victims’ school engagement, academic achievement, and mental and physical health (Conroy and Cotter Citation2017; Gruber and Fineran Citation2007), in addition to contributing to intergenerational cycles of violence and increased risk of violence later in life (Greene et al. Citation2012). An extensive report by Pepler and Milton (Citation2013) highlighted the institutional faults of the school and legal system in the mishandling of the case of Rehtaeh Parsons, a sexual violence victim who experienced digital bullying related to her assault, as key contributors to her death by suicide. Pepler and Milton’s recommendations for change included, specifically, teaching about GBV early.

Teaching and Learning about GBV

Analysis of the Ontario curriculum found that, although there are opportunities to teach about GBV, critical engagement with complex GBV concepts is often limited to upper-year optional secondary school courses (Vanner Citation2021). Much of the scholarship on teaching about GBV exists within higher education; those who work postsecondary and community contexts have long called for K–12 education to join them to take on the challenge of GBV prevention (e.g., Clarke-Vivier and Stearns Citation2019), citing school simultaneously as an important factor in addressing GBV and a place in which it occurs. However, the literature on teaching and learning and GBV in K–12 education is slim, and scholars have mainly focused on sex education.

In 1988, Fine argued that the absence of sexuality education on desire and risk was contributing to girls’ victimisation and terror, particularly for girls of colour, and that comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) could empower girls. Decades later, Fine and McClelland (Citation2006) reflected that not much had changed. Youth who receive CSE are more likely to engage in safe sex and at a later age (Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty Citation2008) and to form healthy, responsible relationships (Ollis Citation2014). Despite the plethora of research and policy updates in the direction of CSE, there remain gaps in its successful implication, particularly for certain student populations; for example, Maticka-Tyndale (Citation2008) found that Indigenous youth are less likely to receive CSE. Bialystok and Wright (Citation2019) advocate for critical sexuality education, arguing that it ‘must go beyond “comprehensive” education to anti-oppressive education that is framed by intersectional approaches’ (354). Education is not limited to schooling, and researchers have found that youth learn both dominant and resistant discourses related to sexual and gender-based violence through public pedagogy via various digital spheres (Almanssori and Stanley Citation2021). Extracurricular spaces have also been explored for their potential for transformative learning (Love Citation2017).

Canadian students want to learn about various GBV topics (Meaney et al. Citation2009; Larkin et al. Citation2017). In Meaney and colleagues’ 2009 study, Canadian secondary students rated highly the importance of learning about sexual coercion and assault, personal safety, and sexual decision-making and communication. Student resistance to GBV within educational institutions has received scholarly and media attention (Lewis and Marine Citation2018), but this attention has been mainly restricted to postsecondary school. Nevertheless, teachers experience various barriers to teaching about GBV and other difficult topics. Barriers include union and governmental policies, threats to job security, and lack of training and knowledge. Teachers in an Australian study cited fears that teaching about GBV was outside their comfort zone, beyond their skills and qualifications, and presented emotional risks for teachers and students (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2021; Dadvand and Cahill Citation2021). Teachers also expressed fears of evoking parental and community backlash, particularly in relation to right-wing expectations that school should be depoliticised. In Canada, backlash has been observed in parental opposition to CSE curricula (Bialystok and Wright Citation2019).

Teacher and Student Identity

Recent emerging scholarship has focused on the role of the explicit and hidden curricula in students’ lives. Critical and feminist scholars have been instrumental in observing that schools can be places that reproduce dominant perspectives on reality (Deem Citation2012; Weiler Citation2017), but that there is also potential for transformation and resistance (McInerney Citation2009; Scorza, Mirra, and Morrell Citation2013). School is experienced differently for teachers and students who belong to social groups at various intersections of marginality and privilege. For example, Indigenous girls who live in poverty in Canada often experience alienation and a lack of support from teachers and administrators (Dhillon Citation2011).

Critical and feminist scholars have troubled dominant understandings of student disengagement in schools, arguing that it is often framed within the individual deficit model and that we should instead trouble the economic and social structures of school and society which cause student disengagement (McInerney Citation2009). Scorza, Mirra, and Morrell (Citation2013) and McInerney (Citation2009) argue that critical pedagogies are antidotes to student disengagement and should be considered essential components of academic excellence. Teachers’ engagement in critical and feminist pedagogies is heavily influenced by their intersecting identities and those of their students (Vanner, Holloway and Almanssori, Citationunder review), as schools reflect the broader systems of inequity and privilege that are present in the surrounding communities.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this study brings into conversation feminist theory, intersectionality, and feminist pedagogy. Shrewsbury’s framing of feminist pedagogy as underpinned by components of community, empowerment, and leadership was used to situate our findings. Recognising that feminist theory has historically centred White, middle-class women, and excluded other experiences of womanhood and gender (hooks Citation1981; Crenshaw Citation1991), we bring in intersectionality (Collins Citation2015) to strengthen this analytical framework.

Feminist theories centre gender as an analytical category for understanding social experience, theorising GBV as intimately connected to power relations and patriarchal social structures. Growing research demonstrates that communities with higher patriarchal norms tend to have higher rates of GBV (Casey and Lindhorst Citation2009). Experiences of GBV are situated within sociopolitical concepts including rape culture, hegemonic masculinity, heteronormativity, and intersectionality, which have been found to be important concepts in GBV prevention education. For example, Pérez-Martínez et al.’s (Citation2021) multi-country systematic review revealed that a ‘gender transformative’ (1) approach to prevention, which engages students in learning about hegemonic masculinities, has been successfully implemented in GBV prevention programming in K–12 and postsecondary schools. Feminist scholars have supported this gendered approach, particularly as it highlights men’s and boys’ roles in GBV prevention (Flood Citation2011; Keddie Citation2021).

The work of Black feminist thinkers in the 1960s and subsequent decades, which centred African American women in its analysis of power relations in the US, eventually provided a framework that has been used to analyse the social, cultural, and political experiences of marginalised groups (Collins Citation2015). Within an intersectional framework, gender and race are mutually constitutive and inseparable (Ferber Citation2007). Lemelle (Citation2010) even suggests moving beyond considering race and gender as distinct categories, as both function as instruments in sociopolitical relations. Students’ experiences of learning are impacted by gender, race, class, and other social constructs, all situated in systemic power structures. For example, research demonstrates that adults view Black girls aged 5–14 as less innocent and less in need of protection from GBV (Epstein, Blake, and González Citation2017). Rahimi and Liston (Citation2009) found that teachers often believe that poor Black girls were encouraged by their culture to be sexually active and that Black teenage pregnancy was a means of securing welfare, which shows that ‘not all women are considered equally violable’ (Hall Citation2004, 13), despite the fact that non-White women are statistically more vulnerable to GBV. Similarly, not all men are considered equally capable of violating. The ‘ideal’ victim is constructed as a White, young, middle-class woman (Hall Citation2004), while the ‘natural’ perpetrator is dominantly portrayed as a man of colour or a Black man (Sharpley-Whiting Citation1997). This is tied to the contemporary construction of Black masculinity, in which there is ‘a continued emphasis on Black bodies as inherently aggressive, hypersexual, and violent’ (Ferber Citation2007, 11). In Canada, colonial powers have historically used patriarchy as a central tool of domination, the legacy of which continues to impact Indigenous communities (Anderson Citation2016). Thus, although patriarchy is the most prominent context in which GBV occurs, it is simultaneously an instrument of other systems of oppression.

Feminist Pedagogy

Feminist pedagogy ‘intentionally troubles, politicizes, and transforms educational experiences’, (Almanssori Citation2020, 54). According to Shrewsbury (Citation1987), feminist pedagogy begins with ‘a vision of the classroom as a liberatory environment in which we, teacher-student and student-teacher, act as subjects, not objects’ (6). Feminist pedagogues often focus on complex, nuanced, and multifaceted issues in which curriculum topics are political in nature and alternative ways of knowing, such as emotion, narrative, and lived experience, are often emphasised (Almanssori Citation2020). We outline the three components of feminist pedagogy theorised by Shrewsbury and discuss how these concepts have shifted through intersectional feminist scholarship.

Empowerment

According to Shrewsbury (Citation1987), empowerment entails developing students’ independence and agency in learning, their sense of responsibility in the classroom as a learning community, and their commitment to intellectual challenge. ‘In such a system, the teacher’s knowledge and experience is recognised and is used with the students to increase the legitimate power for all’ (169), she says. Notions of empowerment have been critiqued by those who, drawing on Foucault (e.g., Foucault Citation1980), point out that power circulates; as such, empowerment cannot be given or gained (Gore Citation1990). Feminist understandings of education have evolved to consider the varied experiences of students and teachers based on their places in the social world. Feminist pedagogues have been instrumental in troubling ideals such as empowerment and democratic dialogue. Boler (Citation2004) reminds us that ‘not all voices are created equal’ (4), that ‘different voices carry different weight’ (11), and that educators have an obligation to moderate classroom dynamics. The notion of a pedagogy of discomfort has been put forward to recognise and problematise ‘the deeply embedded emotional dimensions that frame and shape daily habits, routines, and unconscious complicity with hegemony’ (Boler and Zembylas, Citation2003, 108). Such a pedagogy prioritises the emotional, embodied experiences of learning as an essential component of the critical classroom.

Community

Shrewsbury (Citation1987) posits that a key part of feminist pedagogy is ‘a re-imaging of the classroom as a community of learners where there is both autonomy of self and mutuality with others’ (170). Mutuality involves connectedness and a shared sense of relationship. However, community can be threatened when power dynamics in the classroom are not moderated by the educator in thoughtful and intentional ways (Boler Citation2004; Ellsworth Citation1989). Kimmel (Citation2018) points out, ‘To be white, or straight, or male, or middle class is to be simultaneously ubiquitous and invisible’, adding, ‘this invisibility is political’ (iii). This invisibility has various functions in the classroom. It can make it challenging for students of dominant social categories to attain a critical consciousness. Discussions of power and privilege are often met with resistance by White, male, settler, middle-class, straight, and able-bodied students. Given these critiques, feminist understandings of community have been transformed in a way that is mindful of the function of power relations within and outside the classroom.

Leadership

Leadership, according to Shrewsbury (Citation1987), is characterised by the agency that each member of the feminist classroom develops throughout its span. It complements community and empowerment by charging them with an active element, in which teachers and learners assume shared responsibility for accomplishing the purpose of the course (Shrewsbury Citation1987). Feminist pedagogues have written extensively about student agency. hooks’ (Citation1994) theory of engaged pedagogy emphasises community, collectivity, and cooperation and encourages students to become engaged members in the classroom and the social world. Weiler (Citation1988) stated that ‘for feminists, the ultimate test of knowledge is not whether it is true according to an abstract criterion, but whether or not it leads to progressive change’ (63). Developing student agency is multifaceted rather than prescriptive, and may involve practices such as co-creation of norms, assignments and collaboration in the assessment and evaluation of learning. It can also be achieved through the assignment of experiential learning and social action projects, such as those that involve consciousness raising (e.g., Creasap Citation2014). Notions of accountability, complicity, and resistance as related to systems of oppression, are mobilised by feminist educators to build student agency within and beyond the classroom.

Methodology

Three workshops were planned with distinct groups. Participants were recruited based on their involvement in extracurricular groups that dealt with social justice issues including gender equality, although each had a different approach to how this was taken up with their members.

Young Indigenous Women’s Utopia

The Young Indigenous Women’s Utopia (YIWU) is an award-winning Indigenous-led community group that draws on traditional Indigenous knowledge to empower girls to challenge colonial and gender-based violence and re-imagine a collective future (Altenberg et al. Citation2018; Wuttunee, Altenberg, and Flicker Citation2019). They are based in Treaty 6 Traditional Homeland of the Métis Peoples, also known as Saskatoon, and its members come from numerous First Nations communities. The group has been working with a core group of Indigenous girls since 2016; their work has been connected throughout to the broader research project Networks for Change and Well-being, led by Claudia Mitchell and Rehelobile Moletsane, that uses participatory research to support Indigenous girls to challenge GBV, thus many of the participants were experienced research participants and knowledge creators. For this workshop, the YIWU members invited a friend, thus some participants were new to the research process and to the GBV concepts discussed. 10 self-identified girls ages 11–17 participated in the workshop, which took place over two days in June 2019. Catherine had previously worked with YIWU and had a prior relationship with the group.

Guys Group

The seven participants (self-identified boys ages 15–17) from the Guys Group workshop had all been members of guys groups run by a community organiser and health consultant, who runs programmes with adolescent boys on health and positive masculinity across Nova Scotia. The participants attended the same high school but were in different grades and had varying levels of familiarity with each other. Their group activities involved regular local meetings that used dialogue and individual and collective reflection; several of the participants had also attended a broader youth leadership conference in Toronto. All identified as African Nova Scotian and lived in Halifax. Catherine did not have a prior relationship with the group; it was the participants’ first time participating in a research project. The workshop took place over two mornings in December 2019.

Rangers 12th Unit

Rangers is a Girl Guides of Canada programme; they meet on a weekly basis with self-identified girls ages 15–17, but the program is otherwise flexible and based on the needs, interest, and context of the group and their leaders. Four girls from the Ottawa Rangers 12th Unit opted to participate in the workshop. Catherine invited the participation of the Girl Guides because of their mission and values that emphasise girls’ empowerment and their own girl-driven research, including on gender equality and feminism (Girl Guides of Canada Citation2018). The four Rangers participants for this workshop, however, had not participated in a research project before. The workshop was divided into three evening sessions spanning from December 2019 to March 2020.

Data Collection and Analysis

Each workshop was different but maintained a common format. The researchers worked with the group leaders to develop an agenda that responded to their group. The YIWU group leaders were most involved, leading the design of all non-research activities and contributing to the research activity design. The framework used in the YIWU workshop was then adapted by the researchers for use in subsequent workshops, where the group leaders were consulted but less involved in design. Each workshop began with an introduction to the project and key concepts of GBV, followed by an art-based non-research activity to process the difficult knowledge discussed. Research activities began with a carousel paper activity, in which participants wrote responses to prompts on a flip-chart paper, before rotating to another paper and building on the responses written there by other participants (Vanner et al., forthcoming). The carousel papers were followed by audio-recorded focus group discussions in which the researcher(s) and participants discussed the carousel papers. The participants then worked in small groups to develop cellphilms focusing on the question, ‘What do you want your teachers to know when teaching about GBV?’ Cellphilms are participatory videos using basic technology such as a cellphone or tablet to democratise the research and creation process (MacEntee, Burkholder, and Schwab Cartas Citation2016).

This project constitutes a form of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR), which invites young participants to engage in cooperative learning and knowledge production, often using visual methods (Anderson Citation2019; MacEntee and Flicker Citation2018). YPAR involves participants not only through data collection but also in data analysis (Foster-Fishman et al. Citation2010). In these workshops, initial data analysis took place with participants during the workshops themselves through the multiple methods used to collect and reflect upon the concepts and ideas emerging with the participants. This occurred first through the focus groups, in which Catherine reviewed the carousel papers with the participants and worked with them to identify themes and validate or correct her initial interpretation of the themes and their significance. The development of cellphilms also constituted participatory analysis, as the participants identified the theme from the carousel papers that was most meaningful to them and developed a cellphilm on that theme that spoke directly to teachers.

Following the workshops, data was formally analysed following Charmaz’s (Citation2014)Constructing Grounded Theory, involving coding, memoing, and thematic analysis throughout the data collection process. We used a multimodal analysis (Jewitt Citation2015) that documented and analysed not only the words spoken and/or written, but also images, silences, and relationships between the comments, particularly for the carousel papers and cellphilms. Focus groups, carousel papers, and cellphilms were transcribed by research assistants; data was organised and collaboratively coded using Nvivo software.

Results

Participants envisioned classroom-based education about GBV that was driven by relationships of support with caring teachers and peers, that taught about GBV wholistically and emphasised the impacts on individuals, was responsive to student agency, provided opportunities for student leadership, and imparted practical knowledge for GBV prevention, response, and resistance. Participants’ narratives demonstrated that, for adolescent girls, learning about GBV is not hypothetical. They live with GBV, experiencing harassment, discrimination, and discomfort – including within the school setting – that contradicted the safe and caring learning environments they sought. For Indigenous participants, experiences of GBV were compounded by racist and colonial violence experienced in and out of school.

My School Didn’t Really Talk About That Kind of Stuff

While participants described varying degrees of formal education about GBV, at least one participant in each workshop indicated they had not learned about GBV in school. Many felt this was a significant gap that undermined their ability to prevent and respond to GBV. As YIWU participants stated, to ‘grow up with that knowledge’ would enable them to ‘point it out and deal with it right then, instead of way later’. For Guys Group participants, understanding the impact of GBV was considered pivotal, as they thought that boys and men would be less likely to act violently if they understood GBV’s full impact. While the research focus was on secondary school, participants in all workshops stated that GBV education needed to begin earlier. Yet, as a Guys Group participant stated, they felt that early exposure should be followed by sustained education: ‘start young, don’t wait till we get older to start teaching us about it. And then also you can’t just like let it go. You have to keep re-teaching it.’

For those who had learned about GBV in school, many took issue with how it was addressed, mostly expressing frustration around only learning about some aspects of the issue. For female participants, their frustration had a personal tone. A Rangers participant described how, in her French Catholic school,

… we really didn’t learn that much … we had a super brief workshop about consent, but I wouldn’t even call it that, it was maybe a 10 minute talk. Everything that we heard about kind of rape and sex and stuff like that, it’s always very women-focused and girl-focused … [as if] it’s up to us to kind of not get raped, in a way?

In the YIWU workshop, the conversation often focused on learning about MMIWG. Some YIWU participants had learned about it in school but not in gendered terms which, they felt, led to an incomplete understanding of the issue:

It’s like going to a doctor all your life and them not really telling you what’s wrong with you. But they’re just like telling you the symptoms but not telling you like, ‘You have this disorder, you have this certain type of disease …

The frustration was more palpable, however, for YIWU participants who had not learned about MMIWG in school at all:

My school thinks that they’re very like cultured because they have Indigenous Studies … we wear pink for bullying day, or orange for residential school day … I think it would be fair to wear red on Monday for Red Dress Day,Footnote1 but we didn’t do that at all, we didn’t celebrate that. We didn’t honour them …. me and my cousins and my sisters wore red pins in the shapes of dresses and the teachers would be like ‘oh, is that to symbolize something?’ and we would have to give them the story behind it. Like my one teacher said she’s never heard of that, so I pretty much taught her about it.

The concept of learning ‘the real meaning’ of these issues was prevalent across workshops: participants wanted to learn about GBV deeply and wholistically, in ways that covered not only its prevalence but also the impact, root causes, and actions they could take to prevent it and respond.

Tell It Like It Is

Participants expressed a desire to learn about GBV issues in ways that depicted the reality of the situation. The concept ‘Telling the Truth’ was a title of cellphilms from two workshops and reflected in a Guys Group participant’s advice to teachers: ‘tell it like it is’. Participants valued statistics to understand the prevalence of GBV, as demonstrated in statistics-oriented cellphilms from all workshops, but also emphasised that statistics should be accompanied by testimonies from people who could speak to the experience, as stated in the Rangers cellphilm: ‘Yes, it’s important to know how many people get raped per year, but also tell us about the survivors and their journeys to recovery’. Particularly for Guys Group participants, hearing real-life testimonies, whether through documentaries, case studies, or guest speakers, was important for grasping the reality of the situation. One Guys Group participant said, ‘I feel like the biggest effect is like hearing from a person. You like actually look at someone and think, oh wow, you actually went through it, that’s crazy. It really puts it into perspective of what people actually go through’. Participants in the Rangers group expressed a desire to learn about GBV alongside narratives of sex and gender positivity and fluid gender identities, instead of the focus on sex as inherently risky they experienced in health class. In their cellphilm, they explained: ‘We’d much rather know the gory details about sex than be left to fend for ourselves in the real world. Why are we taught that the only outcome of sex is unwanted pregnancy and STDs for days? There are so many other aspects to sex and we deserve to know the whole truth’.

Participants in all workshops wanted practical knowledge on how to prevent, resist, and respond to GBV. For the female participants, this was largely about protecting themselves. One YIWU participant wrote, ‘Indigenous youth already live in fear of being abducted because we know that there is a target on our people – teach us what to do when in this situation’. The nature of the action-oriented knowledge they asked for varied based on their familiarity with the issues. For example, a Rangers participant’s comment reflected a common misperception about the main GBV risk, centring on girls’ actions: ‘safety precautions can be taught. For example, stay away from dark alleys and walking alone at night’. By contrast, other participants in the same workshop and in the YIWU workshop spoke passionately about the need to teach boys about GBV prevention, rather than placing the onus on girls to protect themselves. The message of teaching boys to respect girls also emerged from the Guys Group participants, who raised the need to counteract the representations of masculinity they are exposed to from the media:

If it was a major topic that was actually talked about in schools and forced on the students so they actually learn how to treat people and how to treat women … that’s not really something that you learn. Most of the time you learn how you treat people from the media and the perception of what it gives you. And, usually, it’s a bad image.

The YIWU participants also extended calls for action-oriented information for collective action, seeking to connect with other advocacy groups to prevent GBV.

Not Alone

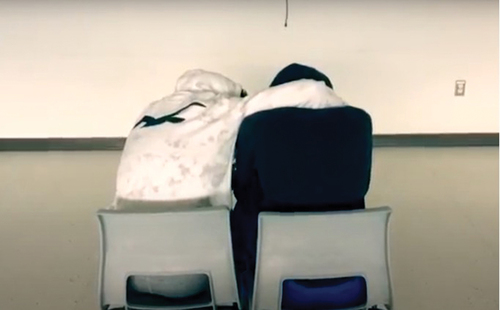

Students emphasised the importance of safe learning environments characterised by supportive peers and a caring teacher. The importance of peer support, particularly for those who may have been affected by GBV, is captured in the Guys Group cellphilm titled ‘Not Alone’, in which a student sitting by himself is joined by another student, who comforts him, and they leave together (). Messages appear saying, ‘Your not alone. It’s not your fault’. and ‘1/3 people’. We then see both students walking out together, with the second student’s arm around the first’s, followed by another message stating, ‘If its not you Lend a hand’. Participants spoke positively about their extra-curricular learning, partly because they had a supportive peer group that had developed over an extended period. While the same dynamics may not be fully possible in a formal classroom, teachers can emphasise relationship and community-building activities prior to teaching about difficult knowledge.

Across the workshops, participants felt they retained knowledge better when it was delivered from teachers in engaging ways. For YIWU participants, they valued learning that draws on traditional forms of knowledge that disrupt colonial ways of knowing. One YIWU participant said she wanted to learn about GBV issues from ‘a certain type of person’, while another pointed to the guest their group leader had brought in to teach the introductory part of the workshop on gender norms, who she appreciated because, ‘he talked about how a Two-Spirited person could sit within the teepee when it’s just like you’ve only ever been taught about two genders’. While YIWU participants described wanting more Indigenous teachers who were able to integrate Indigenous knowledge and cultural practices, as illustrated in the advice to ‘Keep calm and keep smudging – smudging will cleanse your mindset’, They also advised that non-Indigenous teachers could bring this knowledge into their classroom through relationships with established local Indigenous leaders. One YIWU participant expanded on this, describing her experience connecting with a non-Indigenous teacher:

… the Indigenous Studies teacher is really nice and he knows everything … it’s like he’s meant to be an Indigenous person but he’s not. He’s stuck in like a different body …. He’s leaving though this year which is really sad because he was like the only one there I could really talk to about this stuff.

Also consistent across groups was that participants said they listen most to teachers who demonstrate they care about the student as a person. A Guys Group participant explained,

If you have that like mother figure teacher teaching stuff like this, you know like that it’s coming from like deep down place and she actually cares for the students because she’s showing her students that she cares for them. And if it’s one of those teachers that sits behind their desk on their computer all day like, it’s not really gonna get to that student. Because I know when certain teachers speak, I listen better than others.

These quotes highlight that students recognise when teachers demonstrate personal interest in them as individuals, and that students’ relationships with these teachers enhances their engagement in class.

Did You Know That, Teacher?

Students expressed that teachers should be knowledgeable about the GBV issue they were teaching about, reflexive of where they may have knowledge gaps, and welcoming of students’ knowledge. The desire for teacher reflexivity was expressed most explicitly in a skit in the Guys Group cellphilm, ‘Who Teaches Who’, in which a student approaches his teacher after class:

Student: Excuse me, teacher?

Teacher: Hi. Yes, how are you?

Student: I feel kind of bad. I’d like to talk to you about today’s class.

Teacher: What’s wrong with it? I’m pretty sure I covered everything to do with [GBV].

Student: You see, that’s the thing. You didn’t really cover any of it.

Teacher: Yeah, I did.

Student: No, you didn’t.

Teacher: Well, then you tell me about it.

Student: It’s pretty much discrimination against another gender and violence towards another gender. Did you know that, teacher?

Teacher: No, I didn’t. I might have to do more research so I can actually teach the class. Thank you for everything. Have a great day.

Student: Thank you for letting me talk to you.

Teacher: No problem.

In this cellphilm, the student criticises the teacher’s lesson, but appreciates the teacher’s ability to reflect on and adapt his lesson.

Numerous participants described sharing knowledge they gained extra-curricularly with their peers and teachers. A YIWU participant explained:

Participant: Well, like they never taught us about that kind of stuff … like Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, and then there’s like the young men, who get stopped by police, who always get like asked questions and they don’t have the rights, the police don’t have the rights to ask those questions. So, then that’s another form of gender-based violence.

Researcher: So, you were asked to [write an editorial] about it but you weren’t actually taught about it?

Participant: Oh no, I had been taught about it out of school. But not in school. I wanted to write about it because it wasn’t learned, I didn’t learn about it in school.

The GBV knowledge that participants had acquired extra-curricularly was empowering, often spurring them to fill the knowledge gaps in their formal education.

Students across workshops indicated that they sought a classroom environment where they could engage in learning that respected their experiences and perspectives, rather than one-way communication. Guys Group participants repeatedly emphasised the effectiveness of their group leader, who used dialogue-based activities to help them develop their own opinions while also considering other perspectives. One participant explained,

… he would make us think about it. So, he would give us two different perspectives, not just one side of it. So, like one of the activities we did … what would you let your son do compared to your daughter? Yeah, that was really eye opening. Everybody in the room could see that it was a big difference and they should be treated equally.

One of the most frequent suggestions across workshops was the notion that students should be informed in advance when discussion of a GBV issue was planned and allowed to excuse themselves if they worried it would be (re)traumatising. Conversations with students illustrated that there are multiple ways for teachers to embrace students’ knowledge and agency, from providing opportunities to present or dialogue with peers, being open to their feedback, and allowing them to decide for themselves what they could (or could not) handle.

Living With It

We did not ask participants about their own GBV experiences yet, in both the Rangers and YIWU workshops, participants shared that they experience GBV regularly, including at school. Several Rangers participants described harassment from peers, feeling that teachers and administrators responded insufficiently or even with hostility.

Participant: So, harassment in the halls … there’s been maybe two or three assemblies about it in our school but, the thing is, it doesn’t really prevent it from happening. A lot of what I’ve noticed is it’ll happen to most girls and when it’s happened two or three times you just kind of learn to ignore it and live with it, in a way? I know that sounds kind of bleak.

Participant: I know! And then they get mad at you because you’re making a big deal …

Researcher: Who gets mad at you?

Participant: Like the people that are doing it and the administration just kind of [sigh].

Participant: They’d say like, ‘Oh, it’s just a joke.’ It sucks, it’s not funny, it’s not a joke. A lot of the times I’ve noticed like some of my friends come forward about it and nothing’s happened.

Participants in the YIWU workshop also reported experiencing gender discrimination at school, for example through differentiated expectations for girls and boys. More poignantly, YIWU participants described feeling demeaned and excluded at school based on their Indigenous identity, as expressed in two YIWU cellphilms: ‘Stereotypes on Indigenous Students’ and ‘Class Excludes Indigenous Students’. The latter involved a skit that showed students being excluded from an in-school dance class, eventually being told to drop the class. In the skit, the students reflect:

Student: Don’t you notice we’re the only Indigenous girls and we’re getting left out?

Student: Yeah, she does this all the time.

At the end, signs appear that say, ‘Based on true events. No student should be excluded. We should all be treated equally’. Another YIWU cellphilm reflects participants’ fear of being targeted or abducted in their communities, showing a girl waiting for a bus while somebody drives by in a car, waving money and shouting, ‘Do you want to party?’ (). The YIWU participants’ narratives illustrate how gender, racial, and colonial discrimination coincide in their experiences in and out of schools. The experiences of harassment and discrimination described by both groups of female participants sharply contrasted with the supportive learning environments that participants said should contextualise learning about GBV, pointing to the improbability of effectively teaching about GBV while multiple forms of violence are being experienced by girls at school.

Discussion

In alignment with Shrewsbury’s (Citation1987) framework, the discussion is organised according to feminist pedagogical principles of empowerment, community, and leadership. Shrewsbury’s (Citation1987) understanding of empowerment as using teacher knowledge and experience to develop student independence, agency, and commitment to intellectual challenge was reflected in the students’ perspectives, as they pointed out they wanted knowledgeable, skilled teachers who are receptive to student feedback and can reflect on their own knowledge gaps. Participants also emphasised the value of teachers bringing alternative ways of knowing into the classroom. Notions of empowerment, however, were threatened in the classroom for students based on their places in the social world, as evidenced by Indigenous girls in the YIWU group, who reported that they experienced exclusion through racialised, gendered, and colonial discrimination in school. This finding is supported by research that shows that Indigenous girls in Canada often experience exclusion and a lack of support from teachers (Dhillon Citation2011). Boler and Zembylas’ (Citation2003) pedagogy of discomfort, which embeds emotional dimensions within classroom learning, is relevant as most participants strongly believed that students should be able to opt-out of GBV learning that they fear will be retraumatizing. While teachers may seek to empower students by providing them the option to leave a class, Cedar Iahtail (Citation2021) cautions that this option should only be provided after ensuring that sufficient culturally relevant support is provided to students in class and that there should be an appropriate and accessible in-school space designed for healing available for those who choose to leave.

Shrewsbury (Citation1987) theorises community as a balance between autonomy of self and mutuality with others came out most prominently in the Not Alone theme, in which participants emphasised the value of building communities of support and relationality. Positive GBV educational experiences included close and sustained relationships with peers and deep relationships with teachers in which students feel seen. They described their extra-curricular experiences as characterised by these strong connections, as well as activities that invited communal dialogue and were skilfully moderated by their group leader, enabling diverse perspectives to co-exist while presenting students with new knowledge and enabling them to reach their own conclusions. Shrewsbury’s definition of community as extending beyond the classroom space is also reflected in the participants’ calls for bringing in community leaders with ‘real life’ experiences of GBV prevention to facilitate a wholistic understanding. Finally, within this theme it is important to consider the finding that learning about GBV can be an embodied experience, particularly for students who experience it in their daily lives, not just as an object of study.

Themes related to students’ conscious critiques of their GBV learning and wanting to contribute their own knowledge align with Shrewsbury’s (Citation1987) conceptualisation of leadership as shared responsibility assumed by teachers and students. As leadership is tied to student agency and engaged pedagogy (hooks Citation1994), participants demonstrated agency by offering valuable suggestions for teachers and schools, based on their complex lived experiences. Students in this study actively reflected on the inadequacy of GBV education within their schooling experiences and pointed out that GBV education should occur sooner and in a manner that represents the whole truth, including sexuality and consent, and that is situated within the broader contexts of gender, race, colonialism, and other social and systemic power structures. Within the framework of leadership, participants also pointed out their desire for practical strategies for social change, a key feature of feminist pedagogy (Almanssori Citation2020; Creasap Citation2014). Their calls for early, comprehensive GBV education that is action-oriented and engages boys effectively (Flood Citation2011), are supported by many feminist scholars, particularly those who work in sexual violence prevention (Clarke-Vivier and Stearns Citation2019; Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty Citation2008; Ollis Citation2014).

The participants’ perspectives provide powerful testimonies about the need for more teaching about GBV issues, at earlier points in their education, and outside of CSE for the purposes of understanding its connections to our broader social world. They emphasised that they already experience GBV in and out of school and that they hungered to learn about the issue in engaging, intersectional, identity-sensitive, and action-oriented ways and to understand their own roles in resisting the systemic inequities that underlie it. This investigation adds to the literature by centring students’ voices on how GBV can be addressed in K–12 education in a robust manner that connects to the tenets of feminist pedagogy and complements similar advances in postsecondary school. It is limited, however, in that it invited perspectives of students outside of and disconnected to their immediate classroom contexts. Further research that brings together observations and perspectives of students and teachers in the same class would provide even more insight and communal understandings of classroom learning and activism to build upon the findings of this study.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, we gratefully acknowledge the participation and engagement of the youth participants of this study and their group leaders, Morris Green, Jennifer Altenberg, Allison Sephton, and Laura Riggs, who made this research possible. We also acknowledge the contributions of Allison Holloway and Yasmeen Shahzadeh, who were enormously helpful during data collection and initial analysis, and Dr. Claudia Mitchell, whose guidance and advice have blessed this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Red Dress Day is an annual event held by the REDress Project in memory of the lives of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls across Canada.

References

- Almanssori, S., and M. Stanley. 2021. “Public Pedagogy on Sexual Violence: A Feminist Discourse Analysis of YouTube Vlogs after #metoo”. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 1–24. doi:10.1080/15505170.2021.1895382.

- Almanssori, S. 2020. “Feminist Pedagogy from Pre-Access to Post-Truth: A Genealogical Literature Review.” Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education/Revue Canadienne Des Jeunes Chercheures Et Chercheurs En Éducation 11 (1): 54–68 15 June 2020. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjnse/article/view/69579

- Altenberg, J., S. Flicker, K. MacEntee, and K. D. Wuttunnee. 2018. “We are Strong. We are Beautiful. We are Smart. We are Iskwew’: Saskatoon Indigenous Girls Use Cellphilms to Speak Back to Gender-Based Violence.” In Disrupting Shameful Legacies: Girls and Young Women Speaking Back through the Arts to Address Sexual Violence, edited by C. Mitchell, and R. Moletsane, 65–79, Leiden: Brill Sense.

- Anaya, J. 2013. “United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya: Statement upon Conclusion of the Visit to Canada, United Nations” (15 October 2013). http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/statements/statement-upon-conclusion-of-the-visit-to-Canada

- Anderson, A. J. 2019. “A Qualitative Systematic Review of Youth Participatory Action Research Implementation in US High Schools”. American Journal of Community Psychology 65 (1–2): 242–257. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12389.

- Anderson, K. 2016. A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. 2nd ed. Toronto: Women’s Press.

- Bialystok, L., and J. Wright. 2019. “Just Say No’: Public Dissent over Sexuality Education and the Canadian National Imaginary.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (3): 343–357. doi:10.1080/01596306.2017.1333085.

- Boler, M., and M. Zembylas. 2003. Discomforting Truths: The Emotional Terrain of Understanding Difference. In Pedagogies of Difference 115–138. New York: Routledge.

- Boler, M. 2004. “All Speech Is Not Free: The Ethics of Affirmative Action Pedagogy.” Counterpoints 240: 3–13 29 Nov 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42978376

- Bourke, R., and J. Loveridge. 2018. Radical Collegiality through Student Voice: Educational Experience, Policy and Practice. Singapore: Springer.

- Cahill, H., and B. Dadvand. 2021. “Triadic Labour in Teaching for the Prevention of Gender-Based Violence.” Gender and Education 33 (2): 252–266. doi:10.1080/09540253.2020.1722070.

- Casey, E. A., and T. P. Lindhorst. 2009. “Toward a Multi-Level, Ecological Approach to the Primary Prevention of Sexual Assault.” Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 10 (2): 91–114. doi:10.1177/1524838009334129.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Clarke-Vivier, S., and C. Stearns, C. 2019. “MeToo and the Problematic Valor of Truth: Sexual Violence, Consent, and Ambivalence in Public Pedagogy.” Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 34(3): 55–75.

- Collins, P. H. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142.

- Conroy, S., and A. Cotter. 2017. “Self-Reported Sexual Assault in Canada, 2014.” In Ottawa, Canada: Ministry of Industry, Statistics Canada https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14842-eng.pdf?st=TAHvRAvx 29 Nov 2021.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2006. “Sound, Presence, and Power: ‘Student Voice’ in Educational Research and Reform.” Curriculum Inquiry 36 (4): 359–390. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x.

- Cotter, A., and L. Savage. 2019. “Gender-Based Violence and Unwanted Sexual Behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial Findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces.” Juristat 85 (49) 29 Nov 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/85-002-X201900100017

- Creasap, K. 2014. “Zine-Making as Feminist Pedagogy.” Feminist Teacher 24 (3): 155–168. doi:10.5406/femteacher.24.3.0155.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Identity Politics, Intersectionality, and Violence against Women.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039.

- Dadvand, B., and H. Cahill. 2021. “‘Structures for Care and Silenced Topics: Accomplishing Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education in a Primary School’.” Pedagogy Culture and Society 29 (2): 299–313. doi:10.1080/14681366.2020.1732449.

- Deem, R. 2012. Women and Schooling. New York: Routledge.

- Dhillon, J. 2011. “Social Exclusion, Gender, and Access to Education in Canada: Narrative Accounts from Girls on the Street.” Feminist Formations 23 (3): 110–134. doi:10.1353/ff.2011.0041.

- Ellsworth, E. 1989. “Why Doesn't This Feel Empowering? Working Through the Repressive Myths of Critical Pedagogy.” Harvard Educational Review 59(3): 297–325.

- Epstein, R., J. Blake, and T. González. 2017. “Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood”. Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality 29 Nov 2021. https://www.blendedandblack.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

- Ferber, A. L. 2007. “The Construction of Black Masculinity: White Supremacy Now and Then.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 31 (1): 11–24. doi:10.1177/0193723506296829.

- Fine, M., and S. McClelland. 2006. “Sexuality Education and Desire: Still Missing After All These Years.” Harvard Educational Review 76(3): 297–338.

- Flood, M. 2011. “Involving Men in Efforts to End Violence against Women.” Men and Masculinities 14 (3): 358–377. doi:10.1177/1097184X10363995.

- Flutter, J., and J. Rudduck. 2004. Consulting Pupils: What’s In It For Schools? New York: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Foster-Fishman, P. G., K. M. Law, L. F. Lichty, and C. Aoun. 2010. “Youth ReACT for Social Change: A Method for Youth Participatory Action Research”. American Journal of Community Psychology 46 (1–2): 67–83. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9316-y.

- Foucault, M. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1980. C. Gordon,edited by New York: Random House .

- Girl Guides of Canada. 2018. “Sexism, Feminism and Equality: What Teens in Canada Really Think“. 29 Nov 2021 https://www.girlguides.ca/WEB/Documents/GGC/media/thought-leadership/201SexismFeminismEquality-WhatTeensinCanadaReallyThink.pdf

- Gore, J. M. 1990. “What Can We Do For You! What Can ”We” Do For ”You”?: Struggling Over Empowerment in Critical and Feminist Pedago“. The Journal of Educational Foundations 4(3): 5–27.

- Greene, M., O. Robles, K. Stout, and T. Suvilaakso. 2012. A Girl’s Right to Learn without Fear: Working to End Gender-Based Violence at School. Toronto: Plan Canada.

- Gruber, J. E., and S. Fineran. 2007. “The Impact of Bullying and Sexual Harassment on Middle and High School Girls.” Violence Against Women 13 (6): 627–643. doi:10.1177/1077801207301557.

- Hall, R. 2004. “It. Can Happen to You’: Rape Prevention in the Age of Risk Management.” Hypatia 19 (3): 1–18 29 Nov 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3811091

- hooks, B. 1981. Ain't I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism. Boston: South End Press.

- hooks, b. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

- Iahtail, C. 2021. “Presentation at Spirit Bear Teacher Professional (Un)learning Summer Retreat.” University of Ottawa, August 18 and 19.

- Jewitt, C. 2015. “Multimodal Methods for Researching Digital Technologies.” In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Technology Research, edited by S. Price, C. Jewis, and B. Brown, 22, London: SAGE Publications.

- Keddie, A. 2021. “Engaging Boys in Gender-Transformative Pedagogy: Navigating Discomfort, Vulnerability and Empathy.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society: 1–14. Advanced online publication. doi:10.1080/14681366.2021.1977978.

- Kimmel, M. S. 2018. Privilege: A Reader. New York: Routledge.

- Kohler, P. K., L. E. Manhart, and W. E. Lafferty. 2008. “Abstinence-Only and Comprehensive Sex Education and the Initiation of Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy.” Journal of Adolescent Health 42 (4): 344–351. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026.

- Larkin, J., F. Flicker, S. Flynn, C. Layne, A. Schwartz, R. Travers, J. Pole, and A. Guta. 2017. “The Ontario Sexual Health Education Update: Perspectives from the Toronto Teen Survey (TTS) Youth.” Canadian Journal of Education 40 (2): 1–24 29 Nov 2021. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2264

- Lemelle, J. A. J. 2010. Black Masculinity and Sexual Politics. New York, USA: Taylor and Group, Routledge.

- Lewis, R., and S. Marine. 2018. “Student Feminist Activism to Challenge Gender-Based Violence”. In Gender Based Violence in University Communities: Policy, Prevention and Educational Initiatives, edited by S. Anitha, and R. Lewis, 129–149, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Love, B. 2017. “Oh, They’re Sending a Bad Message’: Black Males Resisting and Challenging Eurocentric Notions of Blackness within Hip-Hop and the Mass Media through Critical Pedagogy.” In The Critical Pedagogy Reader, edited by A. Darder, D. Torres, and M. P. Baltodano, 400–411, New York: Taylor and Francis.

- MacEntee, K., C. Burkholder, and J. Schwab Cartas. 2016. “What’s a Cellphilm? an Introduction.” In What’s a Cellphilm? Integrating Mobile Phone Technology into Participatory Visual Research and Activism, 1–15. Rotterdam: Sense Publications.

- MacEntee, K., and S. Flicker. 2018. “Doing It: Participatory Visual Methodologies and Youth Sexuality Research.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Sexual Development: Childhood and Adolescence, edited by S. Lamb, and J. Gilbert, 352–372. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108116121.019.

- Maticka-Tyndale, E. 2008. “Sexuality and Sexual Health of Canadian Adolescents: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.” The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 17 (3): 85–95.

- McInerney, P. 2009. “Toward a Critical Pedagogy of Engagement for Alienated Youth: Insights from Freire and School‐Based Research.” Critical Studies in Education 50 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1080/17508480802526637.

- Meaney, G. J., B. J. Rye, E. Wood, and E. Solovieva. 2009. “Satisfaction with School-Based Sexual Health Education in a Sample of University Students Recently Graduated from Ontario High Schools.” Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 18 (3): 107–125.

- Ollis, D. 2014. “The Role of Teachers in Delivering Education about Respectful Relationships: Exploring Teacher and Student Perspectives.” Health Education Research 29(4): 702–713.

- Olukotun, O., E. Mkandawire, J. Antilla, F. Alfaifa, and J. Weitzel. 2021. “An Analysis of Reflections on Researcher Positionality.” The Qualitative Report 26 (5): 1411–1426. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4613.

- Pepler, D., and P. Milton. 2013. External Review of the Halifax Regional School Board’s Support of Rehtaeh Parsons. Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia.

- Pérez-Martínez, V., J. Marcos-Marcos, A. Cerdán-Torregrosa, E. Briones-Vozmediano, B. Sanz-Barbero, MC. Davó-Blanes, N. Daoud. C. Edwards, M. Salazar, D. La Parra-Casado, and C. Vives-Cases. 2021. “Positive Masculinities and Gender-Based Violence Educational Interventions Among Young People: A Systematic Review.” Trauma Violence Abuse. Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1177/15248380211030242

- Peter, T., C. P. Campbell, and C. Taylor. 2021. Still Every Class in Every School: Final Report on the Second Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools. Key Takeaways. Toronto: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust.

- Rahimi, R., and D. D. Liston. 2009. “What Does She Expect When She Dresses like That? Teacher Interpretation of Emerging Adolescent Female Sexuality.” Educational Studies 45 (6): 512–533. doi:10.1080/00131940903311362.

- Scorza, D. A., N. Mirra, and E. Morrell. 2013. “It Should Just Be Education: Critical Pedagogy Normalized as Academic Excellence.” The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 4 (2): 15–34.

- Sharpley-Whiting, T. D. 1997. “When a Black Woman Cries Rape: Discourses of Unrapeability, Intraracial Sexual Violence, and the State of Indiana V. Michael Gerard Tyson.” In Spoils of War: Women of Color, Cultures, and Revolutions, edited by D. Sharpley-Whiting, and R. T. White, 45–57, Washington, DC: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

- Shrewsbury, C. M. 1987. “What Is Feminist Pedagogy?” Women’s Studies Quarterly 15 (3/4): 6–14 30 Nov 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40005427

- Trudell, A.L., and E. Whitmore. 2020. “Pandemic Meets Pandemic: Understanding the Impacts of COVID- 19 on Gender-Based Violence Services and Survivors in Canada.” Ending Violence Association of Canada & Anova. https://endingviolencecanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2021

- Vanner, C., A. Holloway, and S. Almanssori. Under Review. “Teaching and Learning with Power and Privilege: Student and Teacher Identity in Education about Gender-Based Violence”. Submitted to Teachers and Teacher Education.

- Vanner, C., Y. Shahzadeh, A. Holloway, C. Mitchell, and J. Altenberg. Under Review. Forthcoming. “Round and Round the Carousel Papers: Facilitating a Visual Interactive Dialogue with Young People”. Under Review Leading and Listening to Community: Facilitating Qualitative, Arts-based and Visual Research for Social Change (UK: Routledge), edited by C. Burkholder, F. Aladejebi, and J. Schwab Cartas

- Vanner, C. 2021. “Education about Gender-Based Violence: Opportunities and Obstacles in the Ontario Secondary School Curriculum.” Gender and Education: 1–17. Advanced online publication. doi:10.1080/09540253.2021.1884193.

- Weiler, K. 1988. Women Teaching for Change: Gender, Class and Power. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

- Weiler, K. 2017. “Feminist Analysis of Gender and Schooling.” In The Critical Pedagogy Reader, edited by A. Darder, D. Torres, and M. P. Baltodano, 273–294, New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Wuttunee, K. D., J. Altenberg, and S. Flicker. 2019. “Red Ribbon Skirts and Cultural Resurgence”. Girlhood Studies 12 (3): 63–79. doi:10.3167/ghs.2019.120307.