ABSTRACT

This paper aims to map and understand tactics and practices of resistance to standardised testing in England by focusing on the More Than a Score (MTAS) campaign. More specifically, this paper examines the role of professional organisations affiliated to the MTAS campaign in the production and mobilisation of expert knowledge as a tool for resistance. In particular, by examining their transactions and exchanges, we identify three main tactics of resistance: i) a diffused policy approach, ii) expert reports, and iii) a deep understanding of network boundaries. The development and use of these tactics allowed MTAS to move beyond traditional forms of resistance, towards more complex and granular modes of refusal and contestation. We conclude with a discussion about how this work can extend our understanding of resistance and the tensions and compromise that multi-stakeholder resistance involve.

Introduction

Standardised testing has become a ubiquitous part of schooling across economically developed nations (Lingard, Martino, and Rezai-Rashti Citation2013; Verger, Fontdevila, and Parcerisa Citation2019). At the same time, various stakeholders, including scholars, practitioners, parents, and politicians continue to debate the merits, purposes, and utility of testing. Some actors have grown increasingly sceptical of how tests are being used, leading various groups to mobilise around a desire to resist such trends in education (see Campos Martinez et al. Citation2022). In the U.S., for example, a group of New York-based parents initiated the Opt-Out Movement, which has grown in number and force over the past several years (see Hursh et al. Citation2020; Pizmony-Levy, Lingard, and Hursh Citation2021). In Chile, students and teachers have banded together to resist high-stakes testing and other forms of neoliberal control of the education sector (Stromquist and Sanyal Citation2013). In the United Kingdom, the More than a Score (MTAS) campaign has been organised around the effort to reduce the testing of early years students. It is with this last organisation that we have focused on our year-long network ethnography, which serves as the basis of this paper.

The MTAS organisation is made up of multiple actor groups and has been in operation since 2016. Despite its highly active status within the education landscape in England, there is currently no external research on the organisation’s activities, effectiveness, or tactics. As education researchers work to understand resistance and its relationship to testing and accountability in schools, MTAS offers an interesting case for investigating how a broad coalition of parent- and professional- organisations can influence policy and practice. While our broader project encompasses multiple dimensions and aspects of MTAS, we use this paper to look at one of the key actor groups of the network – the professional organisations. This is because the professional organisations occupy a particularly significant role in helping the network accomplish its primary goals through the deployment and strategic mobilisation of various forms of expert knowledge.

To this end, we use this paper to address the following question: How does the development and use of knowledge-based tactics and practices of resistance allow MTAS to move beyond traditional forms of contestation and transgression, towards more complex and granular modes of refusal and struggle? The paper is organised in the following ways: first, we provide a background to the current testing environment. We start with a broad view of test-based accountability in the context of the UK, with reference to some of the key policy tools within the testing accountability system, and then situate this within the international literature on resistance movements. Then, we articulate our use of network ethnography and how we managed the effects of COVID-19 on our ability to access MTAS events. We follow our analysis of the professional organisations affiliated with the MTAS campaign with a focus on their use of expert knowledge as a technology of resistance. We conclude with a discussion about how this work can extend our understanding of resistance and the tensions and compromise that multi-stakeholder resistance involve.

Background

Test-based accountability in England

The high-stakes accountability system in England is the result of a complex articulation of standardised assessments, end of secondary high-stakes examination (GCSEs) and a consequential inspection system that combine public display of performance data via rating systems and league tables. On the one hand, the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) is responsible for state-funded schools’ inspections in England. Unlike other countries where there is no external inspection (Finland), or the emphasis is on improvement through self-evaluation (Ireland, Singapore)Footnote1, inspection in England plays a key part in the accountability framework, with emphasis on external inspection and a short notice period. Ofsted inspections will result in a school being placed into a banded category, ranging between outstanding, good, requires improvement, and inadequate, with serious consequences for schools on the lowest band which face mandatory academy conversion and high-frequency inspectionsFootnote2.

All key stages are subject to intense testing and monitoring. In reception (age 4), the government has recently introduced the Reception Baseline Assessment (RBA), aimed at making ‘end-to-end’ school-level progress measures possible, producing ‘simple’, un-contextualised data. The purpose of the reception baseline assessment is to ‘provide an on-entry assessment of pupil attainment to be used as a starting point from which a cohort-level progress measure to the end of key stage 2 (KS2) can be created’ (Standards & Testing Agency Citation2019, p.4). In primary, Standard Assessment Tests (SATs) in English and maths are administered to children in Year 2 and Year 6 to monitor their educational progress, and schools’ effectiveness is determined on the basis of these scores which are publicly available. Finally, the main assessment for KS4 is a tiered exit qualification known as General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSEs), which determine school and college sixth form options (A levels) and subsequent eligibility for university courses. A recent report by the DfE (Department for Education) (Citation2017) argues that ‘the high stakes system can negatively impact teaching and learning, leading to narrowing of the curriculum and “teaching to the test”, as well as affecting teacher and pupil wellbeingFootnote3’. The NUT report titled ‘Exam Factories? The impact of accountability measures on children and young people’ (Citation2015) highlights that school strategies in relation to accountability have resulted in additional work for teachers, making them tired and stressed (12). These strategies include i) the use of teacher appraisal to set targets related to improving pupils’ attainment (linked to performance-related pay in many schools), ii) explicit targets/outcomes for every lesson/activity, and iii) mock Ofsted inspections, among others.

There are also more specific strategies related to the production, scrutiny, and use of data to target teaching such as detailed and frequent data gathering and scrutiny of pupils’ progress, use of data to target individual pupils, and regular preparation for national tests. In this context, Bradbury and Roberts-Holmes (Citation2017) refer to the increased prominence and visibility of data in schools as ‘datafication’Footnote4, drawing attention to the velocity and volume of data-based demands on teachers. Indeed, they claim data collection has a significant impact on the classroom, driving pedagogy and dominating workloads. Data itself have ‘come to partly represent the teacher’s pedagogical focus and a means by which to measure their competence and ability’ (Roberts-Holmes Citation2015, 307), and teacher’s pedagogy has ‘increasingly narrowed to ensuring that children succeed within specific testing regimes which interpret literacy and numeracy in very particular ways’ (303).

Resistance to test-based accountability – international cases

By different means and to different ends, movements to resist the effects of test-based accountability have taken hold around the world (see Campos Martinez et al. Citation2022). Such efforts have been led by various groups, from university students and teachers in Chile to school parents in New York City. While the research on these movements is still emerging, some scholars have provided rich accounts of various resistance tactics and outcomes to date. In New York, for example, researchers have been following and analysing the NY Opt-Out Movement for several years (e.g., Green Hursh et al. Citation2020; Pizmony-Levy and Saraisky Citation2016; Saraisky and Pizmony-Levy Citation2020). This research has found that strategic coordination (e.g., via social media) to mobilise parents and teachers has led to elected political leaders at the local level and, ultimately, the shift to optional testing that requires parental authorisation (Chen, Hursh, and Lingard Citation2021). Similar to our study, Wang (Citation2021) also drew on network analysis to better understand how actor and discourse networks have shaped the Opt-out movement in New York. She found that the opt-out advocacy coalition (i.e., those who supported the movement) was larger in number and in influence, which led to significant gains for the resistance to testing in the state.

Research on Chile’s Alto al SIMCE (Stop SIMCE), which has also relied on coordinated media campaigns (i.e., social and traditional media outlets), has brought together academics, teachers and higher education students to reduce the number of exams students are required to sit and end school rankings (Montero, Cabalin, and Brossi Citation2018; Sisto et al. Citation2022). Similar movements are taking place across Brazil (Rodrigues, de Almeida, and Simões Citation2022), Isreal (Sabag and Feniger Citation2022), Norway (Skedsmo and Camphuijsen Citation2022) and Catalonia (Parcerisa et al. Citation2022). While there are specific tactics and actors within these different contexts, the motivations to disrupt the hyper-focus on testing, standardisation and accountability are similar.

Like these national contexts, England’s testing measures have also been met with growing scepticism from parents and other public actors, such as teacher groups, politicians (Moss Citation2022). One of the groups that has positioned itself as a key player, particularly in their push back against early years’ testing, is the More than a Score (MTAS) campaign. More Than a Score is a coalition of organisations and individuals connected to early years and primary education including parents’ groups, academics, trade unions and subject associations. As stated on their website, this diverse group of organisations is united under the call to ‘to change the way primary school children are assessed and the way schools are held accountable through high-pressure statutory tests’. Over the course of the MTAS campaign, they have added to their repertoire of strategies, including the use of professionally produced videos, social media presence, and mass emailing. They have also produced a ‘toolkit’ that provides tips for individuals who want to get involved within their local area. It is designed to help ‘raise awareness of More Than A Score and adds to the growing number of voices opposed to the current system of high stakes government testing in primary schools’ (MTAS, Citationn.d. 2). These include tips for writing to local council and/or Member of Parliament (MP), how to organise local meetings and events, and how to participate in boycotts. We contend that MTAS can be best understood as an issue network (Travis and Abaidoo-Asiedu Citation2016). Issue networks are an alliance of various interest groups and individuals who unite to promote a common cause or agenda in a way that influences government policy. Issue networks are generally free-forming groups of people in the public sector coalesce not through a congressional committee or a National Agency but to accomplish a task at hand.

Methodology

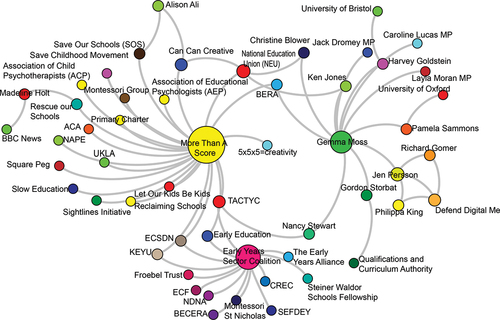

Powerful policy players in global education such as the OECD, the World Bank and UNESCO have been well researched, while others, such as edu-businesses, EdTech companies, philanthropies and social enterprises, have only recently started to be explored. In our previous work (Ball, Junemann, and Santori Citation2017; Campos Martinez et al. Citation2022), we gave primary attention to the new actors in the global education policy network (foundations, education corporations, think tanks, funding platforms and management service companies) while acknowledging the need to study voices of dissent. These dissident voices question and challenge shared beliefs of the mainstream global policy community members, and they are unwelcome and often unheard, or rarely attended to. Such voices are excluded from the mainstream global education epistemic community because they speak about education differently and constitute a network among themselves, which we continue to investigate in this paper. We suggest that ‘network ethnography’ (Ball and Junemann Citation2012; Ball, Junemann, and Santori Citation2017) is best suited to our attempt to specify the exchanges and transactions between organisations involved in resisting standardised testing in England, and the roles, actions, motivations, discourses, and resources of the different actors involved. The network we describe and research is primarily focused on the More Than a Score campaign (see ), and includes teacher, parent, and head teacher-led organisations, as well as other related professional bodies.

Figure 1. MTAS network.

Network ethnography involves close attention to organisations and actors within a field, to the chains, paths and connections that join up these actors, and to ‘situations’ and events in which policy ideas are mobilised and assembled. Börzel (Citation1998, 253) describes policy networks as

a set of relatively stable relationships which are of non-hierarchical and interdependent nature, linking a variety of actors who share common interests with regard to a policy and who exchange resources to pursue these shared interests acknowledging that cooperation is the best way to achieve common goals.

In the case of MTAS, the diversity of organisations involved in the campaign (not only in terms of mission but also in terms of internal structure and representativeness) provides an interesting opportunity to explore interaction and governance within a non-hierarchical space with varying degrees of power (understood in terms of social, economic, reputational and knowledge capital, and as we have recently claimed, legitimacy capital – see Holloway and Santori Citation2022).

There are two key elements in social networks: the ‘nodes’ (which can be individuals, organisations or even subject positions) and the ‘ties’, which are the links between them. Rather than focused on ‘individual attributes’ social network analysis is a method for studying ‘social relations’ (Burt Citation1978). However, the ‘lines’ in a network diagram do not always represent the quality of those relations. The challenge, Crow (Citation2004) warns, is to identify what ‘passes’ through networks. That is, schemes, programmes, propositions, artefacts, techniques and technologies, and money move through these network relations. Indeed, they move at some speed, gaining credibility, support and funding as they move, mutating and adapting to local conditions at the same time. To this end, we focus our analysis on the different forms of value that the participant organisations bring to the MTAS coalition and the particular ways in which these capitals materialise, providing further leverage for policy change.

Data collection

There are different sorts of data involved in network ethnography, and a combination of techniques for data gathering and elicitation. Network ethnography requires deep and extensive Internet searches (focused on actors, organisations, events and their connections). There is a large body of material available online (newsletters, press releases, videos, podcasts, interviews, speeches and web pages, as well as social media such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and blogs) that can be identified and analysed as data in policy research. Drawing on initial findings from actor- and organisation-focused searches, we developed topic lists and open-ended questions to inform each in-depth interview with nodal actors within the network. We contacted and interviewed every member organisation of the MTAS campaign, with a total of 20 semi-structured interviews with directors and spokespersons of member organisations of the MTAS coalition. We also contacted and in some cases interviewed other actors identified by our interviewees as being central to the network or having made specific contributions to the development or success of the campaign. The interviews lasted between 40 minutes and an hour and a half and involved questions about i) organisation background and participant role in it, ii) factors contributing to the organisation’s decision to join the MTAS campaign, iii) what being a member of the MTAS coalition entailed, iv) what they brought to the campaign/contributed to the functioning/success of MTAS, v) perception of the key actors/stakeholders in the running of the campaign, vi) perception of the main successes and challenges ahead. In order to maximise the relational potential of the interviews, we relied heavily on follow-up questions as a way to explore emergent associations. We also conducted post-interview searches that in turn informed subsequent interviews.

Network ethnography also involves participating in some of the key occasions where the network participants under consideration come together. As Cook and Ward (Citation2012, 139) put it, conferences ‘continue to be important in creating the conditions under which policy mobility may or may not take place’. Conferences and other events (both face-to-face and online) are moments when both bonding and bridging ties are forged and renewed (Granovetter Citation1973; Putnam Citation2000). Whilst COVID-19 restricted the opportunities to organise and attend face-to-face events, as part of our network ethnography we attended a series of online events including:

Toxic testing – why fundamental reforms are needed now (22 September 2019).

EYFS Reforms Consultation: Q&A session (21 January 2020).

Drop SATs 2021 webinar (21 September 2020), Expert panel, over 200 school leaders, and MPs.

Drop SATs 2021: A United Call for Action (15 December 2020).

Data analysis

To analyse the qualitative interview data, we began by open coding to understand the scope and substance of the interviews. We also used analytic memoing to track our ongoing thinking and theorisation while meeting regularly to discuss what we were finding. A combination of hand-coding and NVivo was used to chart regularities in the data in relation to particular themes and identify both prevailing tendencies and discrepant cases (LeCompte and Preissle Citation1993). While NVivo facilitated detecting patterns from a relational perspective (using word frequency charts, word clouds and comparison diagrams), we were cautious in our reliance on Qualitative Data Analysis software which can sometimes obscure the more implicit/embedded aspects of narrative accounts.

We used Gephi software to create the network diagram. The size of the nodes is proportional to the number of connections, and the ties represent any form of exchange (of knowledge, influence, funding, etc.). Given that this is a rather small network (<100 nodes), SNA metrics such as centrality, density and clustering coefficient were not necessarily relevant to the analysis. Instead, the network diagram is used to visually convey the diversity of stakeholders (from child psychotherapist associations to children’s art organisations, to parent groups), and as a visual cue to understand the role of some key organisations and actors.

In the following sections, we deploy and examine these sorts of materials and claim they have the potential to illuminate the extent of influence of new kinds of actors on processes of policy, and the identification of new spaces of policy and conduits (both virtual and face-to-face), relations and interactions between actors. We use these data as the basis for an analysis of the dynamics and labour of the MTAS network.

High-stakes testing: a complex policy issue

In the context of England, statutory tests represent a complex policy issue characterised by relative apathy from parents and considered inconsequential for the government. Unlike other controversial issues such as abortion and drug laws that quickly develop into clear-cut political views and positions, standardised testing represents a more opaque and subtle issue that is therefore less likely to receive attention from the public. According to the Chief Executive of Early Education:

trying to get people to say testing four-year-olds is bad is surprisingly rather different. You know, you get dismissed as alarmists [inaudible] they’re not sat down in rows, it’s not like sitting an exam, you know. Or, you know, a lot of sort of middle-class people going, ‘Oh, but my four-year-old was fine’, and not thinking about the fact that maybe their four-year-old isn’t typical of every four-year-old. (…) I think there is a lot of apathy around these things, that if you could, sort of, surface … if you could engage parents, I think, yes, you would find quite a lot who would think, oh, maybe that’s not so great, but you have to kind of get them to engage with quite complex arguments before they’re in a position.

Positioning this issue as a policy problem represents a challenging task, as statutory testing does not seem to gain visibility against other competing issues and agendas. As noticed by the Chief Executive of Early Education:

So, you know, you think about, are these issues that MPs will hear about on the doorstep? Generally, no, they’re not. They might be hearing, ‘I can’t go back to work because I haven’t got a place at nursery’, or, you know, ‘My nursery bills are higher than my mortgage’, but they’re not generally hearing, ‘I’m worried that my four-year-old is being tested’, or, ‘I don’t like the type of learning that my child is being offered’.

As a result of this relative apathy from parents, and the consequent lack of interest from MPs, there is little incentive for the Conservative government to consider advice from experts and contemplate policy change. The DfE has been described as ‘unswayable’ in their approach to Reception Baseline Assessment (RBA):

Yes, I’ve been going to meetings with the DfE and the Standards and Testing Agency around the foundation stage profile, for instance, and raising anything about the baseline and the reforms they’re doing to the EYFS, they will talk about other things, but they say baseline is non-negotiable. It’s going to happen, don’t talk to us about it. So, it’s a closed door. (Chair of TACTYC)

So instead of seeking immediate policy change, the overall MTAS strategy focuses on long-term policy change through the development of a common understanding and shared sense of legitimacy. This approach was described by a spokesperson of TACTYC as ‘supporting a groundswell’, a growth of support both from within the education sector but also from political parties. She notes:

it is trying to support a groundswell, trying to build a consensus that this is wrong and that something has to change. We now have got to the point where every political party, except the Tories, have said that they would change it, you know, that they’re going to scrap SATs, that they’re not going to do the baseline, etcetera. And, you know, even the NAHT, who is supporting baseline, is partly doing that in order to get rid of the Key Stage 1 SATs, so that’s their main reason. They think, well, we’ll at least have all those years free of standardised testing, and they see it as a first step and then we can get rid of the baseline. So, you know, there is a growing agreement that it’s gone too far, that it’s too limiting and it’s really looking at, yeah, not direct action change as much as trying to get the policies changed, I think. (Chair of TACTYC)

As noted by Pickett (Citation1996, 458), ‘the strategic knowledge of power necessary for effective resistance must be more concerned with this productive function of power than with the less important negative techniques’. The groundswell that the Chair of TACTYC refers to in the excerpt above can be related to the idea of a ‘gesture’, some sort of movement that expresses a broader view of the role education and learning in society, and the experience of learning for children and their families.

Professional organisations in the MTAS coalition

There are several professional organisations associated with MTAS. These include the British Educational Research Association (BERA), the Association for Professional Development in Early Years (TACTYC), the British Association for Early Childhood Education (Early Education), the National Association for Primary Education (NAPE), Early Childhood Studies Degrees Network (ECSDN), Association of Child Psychotherapists (ACP), and Association of Educational Psychologists (AEP). Whilst all these organisations provided valuable input to the strategy and direction of the MTAS campaign, in this paper we will be focusing on three of them (BERA, TACTYC and Early Education), whilst making occasional reference to the others based on publicly available information as well as our own interview data. The selection of organisations under analysis in this paper is based on the centrality of their representatives in the strategy and executive direction of the MTAS campaign (usually referred to as the core group by interviewees) and the diversity of their contributions. So the centrality of these organisations in the network was not necessarily due to the number of connections or available resources but related to the leadership, labour and commitment from their directors/chairs/president. Data triangulation from our interviews, events attended, internet searches and newspaper coverage corroborates this decision. Hereafter we will provide a brief overview of each of these organisations to offer some background to the mechanisms and practices that they deploy towards destabilising dominant understandings around early years teaching and learning.

BERA is a member-led charity that exists to encourage educational research and its application for the improvement of practice and public benefit. With more than 2000 members, BERA publishes four peer-reviewed journals and has 35 Special Interest Groups (SIGs), which represent the particular research concerns of different members. BERA also hosts dedicated networks for Early Career Researchers and Independent researchers, as well as the British Curriculum Forum.

TACTYC is a charity that promotes high-quality professional development for early years practitioners to enhance the educational well-being of the youngest children. Its main areas of action are advocacy and lobbying – responding to early years policy initiatives and contributing to the debate on the education and training of the UK early years workforce; information and support – developing the knowledge-base of all those concerned with early years education and care by disseminating research findings through the international Early Years Journal, annual conference, website and occasional publications and encouraging informed and constructive discussion and debate.

Early Education is a national charity supporting early years practitioners with training, resources and professional networks, and campaigning for quality education for the youngest children. Early Education offers support to its 3500 members through publications, training and consultancy, national events and conferences, and local branch meetings. In the following section, we show how the work of these professional organisations contributes to the collective aims and outcomes of the MTAS campaign.

Tactics of resistance

Based on our thematic coding of interview data and documentary sources, we have identified three main tactics and practices of resistance: i) the deployment of a diffused approach to policy with a rather conciliatory attitude to dealing with diverse (and often conflicting) stakeholders’ interests which we tentatively describe as ‘diffused politics’, ii) the production and circulation of expert reports, and iii) the ability to use their understanding of the boundaries of the network in order to guard against the unilateral advancement of government policy. Through the illustrations we present and discuss, we offer glimpses and examples of the working, evolution and dissemination, language and shared assumptions that make this community, as a network, effective in relation to education policy and education reform, and which hold it together epistemically.

Diffused politics

Travis and Abaidoo-Asiedu (Citation2016) note that ‘the actors in issue networks do not necessarily know, nor agree with, one another (…). They are intellectually and/or emotionally committed to the issues, not each other’ (3420). Networked forms of resistance (like MTAS) are characterised both by diversity and ambiguity. The MTAS coalition brings together a diverse range of stakeholders, with competing, and sometimes conflicting, views and interests. Unlike common understandings of resistance characterised by unilateral and collective refusal, MTAS uses compromise amongst its diverse stakeholders to project solidarity and conceal internal conflict.

TACTYC Chair’s reference to ‘fine points’ nicely captures the contradictions and tensions that characterise the coalition, and in order to hold this diverse group of organisations together some of the key positions of the coalition have to remain diffuse and elusive. This relates to Foucault’s account of modern power as ‘ubiquitous, diffuse, and circulating’, which emphasises the difficulty of resistance. Since power is spread throughout society and not localised in any particular place, notes Picket, ‘the struggle against power must also be diffuse’ (Pickett Citation1996, 458). As noted by the Chair of TACTYC, the use of ‘signposting without putting the MTAS letterhead on it’ epitomises the contradiction and ambiguity that the MTAS campaign must embrace. This is in stark contrast with the strategies deployed by other anti-testing movements internationally, such as the Opt-out movement in New York, which conveys an explicit, univocal message exhorting parents to boycott the standardised tests by opting out.

Expert knowledge/reports

Another salient tactic of resistance deployed by professional organisations in the MTAS coalition is the production of expert reports. Expert reports and position papers are generally used to condense/stabilise meaning in a semantic field, and thus control processes of sense-making and interpretation (Duke and Thom Citation2014). However, expert reports only occasionally result in policy change (Lundin and Öberg Citation2014), as they usually speak to a specific audience and require multiple translations. As we have noted elsewhere, processes of translation by which academic insights are reproduced in policy contexts are complex, ‘incorporating discursive elements, networks of people and organisations, and the material production of highly consumable texts, books, events and talks’ (Ball, Junemann, and Santori Citation2017, 916). This suggests the need to move away from the production of highly codified texts that have academics as the main audience, towards the production of ‘highly consumable texts’. As noted by the former BERA president, ‘where the BERA relationship to More Than A Score rests is that BERA contributes in kind. And the in kind, if it exists as a tangible something that More Than A Score could point to, is the Baseline Without Basis report. BERA funded the Baseline Without Basis report, I convened the panel’.

The ‘A Baseline Without Basis’ report (Goldstein et al. Citation2018), she notes, was ‘written to intervene’, evidencing an implicit effort to build in accessibility and circulation as a structural feature of the report instead of leaving its take up to chance. This was done from the outset with the strategic selection of trusted and politically involved panel members. As the former BERA president explained:

So, I just asked people that I knew and trusted, from very diverse backgrounds, to get involved on that issue. (…) It’s also been written to intervene, all right, so that the panel that I composed for the BERA Better Without Baseline report, is a panel that are themselves both academics and politically engaged, roughly speaking. So we’ve composed a panel with diverse interests to speak from an academic position but to speak with the intention of intervening.

Some of the expert panel members were key assets to the design and construction of the Better Without Baseline report based on their reputation and expertise. For instance, the former BERA president described Professor Harvey Goldstein as a ‘long-time plague on government from a statistical point of view’, and Professor Gordon Stobart (former Qualifications and Curriculum Authority [QCA]) as someone who ‘understands absolutely how to influence government’. But they made it clear that influencing government required not just the production of relevant knowledge but its active mobilisation through the right channels. Box 2 illustrates how expert views are mobilised within parliament.

There are several elements to pull out from this excerpt. The first one relates to the policy credibility that facilitates access to these spaces. We have noted elsewhere (Ball, Junemann, and Santori Citation2017) that reputation and social relations (both accumulated over time) can be converted into policy credibility and facilitate access to policy conversations and various sites of policy. The former BERA president described herself as a ‘person who has substantive interests in the connections between policy, research, and practice, who has a trajectory within BERA’, and as ‘a permanent boundary-spanner’. Boundary spanners ‘tend to have high network capital because they are proficient at creating inter- and intra-organisational social connections’ (Hogan Citation2015, 307). Her double role as former president of BERA and representative of the MTAS coalition brought together research gravitas and activist commitment.

The second element relates to the actual ability to inhabit and navigate policy spaces, which we understand as network capital (see Ball, Junemann, and Santori Citation2017). Urry (Citation2007, 197) defines network capital as ‘the capacity to engender and sustain social relations with those people who are not necessarily proximate and which generates emotional, financial and practical benefit (although this will often entail various objects and technologies or the means of networking)’. Network capital generates a certain sort of expertise that can be deployed in persuasive performances – policy pitches – in both intimate and public arenas. This involves speaking about, explaining and justifying policy ideas. That is, the work of ‘framing and selling’ policy (Verger and Curran Citation2014) discursively reworking policy agendas, joining up previous policy ideas to new ones, mounting ‘jurisdictional challenges’ (Reckhow and Snyder Citation2014) and recognising and taking advantage of or opening up new ‘policy windows’. As the former BERA president notes in her account of the parliamentary briefing, her conversation with the backbench shadow education spokesman resulted in an opportunity to shape the discussion towards parental rights to withdraw their children from statutory assessment, in turn getting the attention of other MPs in the room. Network capital, Urry notes, ‘is a product of the relationality of individuals with others and with the affordances of the “environment”’ (Urry Citation2007, 198). In this case, the parliamentary briefing constituted a positive environment to gauge the political appetite for change.

The final element relates to the ways in which ‘previous pathways of interconnection and more contingent (and chance) intersections’ (Cook and Ward Citation2012, 140) can be leveraged to bring about change. The former BERA president described how MTAS’s previous involvement with Defend Digital Me, an organisation that protects children’s rights to privacy and family life, acquired new value in the context of the discussion around parental rights to withdraw their children from statutory assessments, and hence her recollection about ‘getting little hotspots bubble up’ at the parliamentary briefing. This represents ‘a form of “buzz” generated by the co-presence of policy makers and practitioners from a range of different contexts’ (Cook and Ward Citation2012, 150).

Network boundaries

A third tactic of resistance deployed by MTAS professional organisations relates to their understanding of network boundaries, and its use as an asset for resistance. By understanding of network boundaries, we mean a clear sense of the size and structure of the network, including the centrality of nodal players, and the overall density and cohesion of the network as well as the presence of sub-groups or cliques. This deep understanding of the network and its boundaries results in a clear sense inclusion and exclusion, or put differently, who is in the network and who is not. In Citation2018, the DfE published what they presented as a review of the Early Learning Goals (ELGs) but was in fact a comprehensive rewrite of the EYFS Statutory Framework, including the Educational Programmes for each Area of LearningFootnote5. The fact that such an extensive process of change had been embarked upon with very little engagement with sector representatives and experts caused concern and frustration in the early years sector. In the quote below, the Chief Executive of Early Education provides a compelling account of their understanding the early years sector, and how they used this understanding to counter unsubstantiated governmental attempts of reform.

So, when we have gone in and talked to officials, on numerous occasions I’ve taken groups of experts in with me and we’ve sat and we’ve talked through drafts and we’ve addressed key concerns, and yet there’s still this strong sense that officials and ministers aren’t listening or are only hearing very selectively what they want to hear. And I kept being told, ‘Well, you’re saying that but we’re hearing different things from different people’, and I thought, ‘That’s really odd because I talk to a lot of other organisations in the sector and they’re all saying the same thing’. So, I got as many organisations as I could think of, who represent particular parts of the sector, together in a coalition. (…) Yeah, so we’ve had this really strong coalition, which I think represents everyone I can think of within the early years sector and we all have a very joined-up view about what’s wrong with these changes and yet officials still turn round and say, ‘Oh, well, but we hear different things from people’. So, I really am fascinated to know who these other people are that they talk to, because I’m not saying they don’t exist, but I’m not convinced they’re remotely representative.

As noted in the interview excerpt above, concerns about the process and objectives of the new non-statutory curriculum guidance, ‘Development Matters’ (DfE Citation2020), resulted in the development of a sector wide coalition, the Early Years Sector Coalition. The Early Years Sector Coalition represents a diverse group of organisations in the sector, including day nurseries, HE institutions, teacher associations and other multi-stakeholder organisations. Box 3 presents information displayed on TACTYC’s website, which lists the organisations involved, indicating the number of members each of them represents.

The Early Years Sector Coalition used two technologies of resistance that evidence the strategic deployment of deep knowledge of the structure and boundaries of the network which we discuss in detail: purpose-designed consultations and commissioned literature reviews. As noted in the press release statement on the non-statutory guidance for the EYFS, the Coalition:

produced a review of the research literature from the last 10 years to identify evidence which should be informing the changes. This was publicly launched and published and offered to the government to inform its thinking.

carried out a survey of 3270 practitioners’ views on what aspects of the EYFS should be changed to support ministers’ stated objectives. This was also published and shared with government.

These tactics evidence an ability to delineate the field both through processes of consultation and knowledge-synthetisation. Early Education seems to have the organisational authority to identify, contact and persuade organisations to join a coalition, and the expertise to classify and curate existing research in the field over a 10-year period.

As a technology of resistance, to commission a literature review is a powerful tool to question the legitimacy of the government decision to review EYFS statutory framework, retaining the power to legitimise the need for change within the academic and practitioner community. Put simply, the Early Years Sector Coalition claims that if there are no scientific publications that consider the EYFS statutory framework to be an issue, then there are no grounds to justify the reform.

The evidence review was conducted using the principles of Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA)Footnote6 and is in line with government guidelines. The review design was conducted according to systematic protocols which ensured that the sources retrieved were both high-quality and relevant to the research questions. The overarching research questions were developed to specifically address current government initiatives and priorities: How far does the rationale for the prime and specific areas and the characteristics of effective learning reflect current knowledge about early learning and teaching? What aspects of the EYFS are affirmed and what needs adjustment based on evidence from the last 10 years? The Early Years Sector Coalition evidence review concluded that there ‘is no substantiated case for the EYFS Statutory Framework to be significantly changed’ (Pascal, Bertram, and Rouse Citation2019, 7). One concrete outcome of the evidence review was that the DfE invited Early Education to be part of the EYFS Advisory Panel.

The practitioner consultation created a tension between desk-based bureaucrats and frontline practitioners, by portraying the mismatch between the alleged ground of the EYFS statutory framework review and the perceptions from those on the ground. The report (Bamsey et al. Citation2020) claims that, when asked how well the current EYFS supports children’s development across the seven areas of learning, respondents were overwhelmingly positive about how well it supports the Prime Areas of Development (personal social and emotional development; communication and language; physical development); over 80% of respondents judged that children’s development was well supported or very well supported in these areas by the current EYFS (14).

Taken together, these two technologies of resistance are designed to retain control by the production of specific forms of expert knowledge. These are in the form of an evidence review, by producing knowledge about what has been said by scholars in the field; and in the form of a practitioner consultation, in order to establish the perceptions and concerns from those on the ground.

Conclusion

While resistance in education (broadly) has been investigated in a variety of ways, resistance to high-stakes testing remains a space that is relatively under-explored and under-theorised (Campos Martinez et al. Citation2022). Across the literature, some have focused on more overt forms of resistance, like the Opt-out Movement in the U.S. (Hursh et al. Citation2020; Pizmony-Levy, Lingard, and Hursh Citation2021), or the collective protests against neoliberal reforms in Chile (Stromquist and Sanyal Citation2013). Others have focused more on the ‘everyday’ forms resistance that take place in classrooms and schools (Anderson and Cohen Citation2015; Blackmore Citation2004; Perryman et al. Citation2011). We argue that MTAS as a conglomerate of organisations has operationalised resistance in a way that sits outside of this obvious binary.

Over and against traditional forms of resistance based on political dissent – as protest, opposition, contestation, dissidence, or rebellion – (Niesen Citation2019), the MTAS coalition has developed a more nuanced, long-term approach for policy change based on consensus building as a key technology of resistance. This form of ‘concerted resistance’ is based upon awareness of the difficulty of resisting long-established, heavily bureaucratic structures (like SATs, which were introduced in England three decades ago), and the complexities of policy processes and partisan politics, traditions and alliances. Faced with an ‘unswayable’ government, the overall MTAS strategy focuses on ‘supporting a groundswell’, as a movement that expresses a broader view of the role of education and learning in society, and the experience of learning for children and their families. To this end, MTAS’s knowledge-based organisations fulfil a central role in the development of policy credibility and network capital. Throughout the paper, we have explored key tactics in the push against high-stakes testing which include a diffused politics, by using compromise amongst its diverse stakeholders to project solidarity and conceal internal conflict; leveraging expert-knowledge and reputation to shape sense-making and interpretation of existing policy frameworks through position papers and expert reports; and deep understanding of network boundaries, using processes of consultation and knowledge-synthetisation to delineate the contour of the network. Our work suggests the need to understand more complex and granular modes of refusal and contestation that move beyond traditional forms of resistance as political dissent and to continue study the tensions and compromise that characterise ‘concerted’ forms of resistance.

Ethical statement

Approved by King’s College London Ethics Committee. Ethical Clearance Reference Number: MRA-18/19–14344.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Daniel Gellai for his help with the design of the network diagram.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Caroline Perry, Research and Information Service, Research Paper 126/13, October 2013. Available at: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2013/education/12613.pdf

2. Nerys Roberts, House of Commons Library, Briefing paper 07091, August 2019.

3. See for instance https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/may/01/sats-primary-school-children-suffering-stress-exam-time

4. ‘The translation of information about all kinds of things and processes into quantified formats’ (Sellar 2015, 769).

5. For a comprehensive account of the changes to the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework see: https://foundationyears.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/EYFS-Reforms-Table-of-changes.pdf?utm_source=Foundation+Yearsandutm_campaign=d2819a1221-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_21_05_01_COPY_01andutm_medium=emailandutm_term=0_8f9a6de061-d2819a1221–321538225andmc_cid=d2819a1221andmc_eid=97c3870c06

6. According to DfID, rapid evidence assessments provide a more structured and rigorous search and quality assessment of the evidence than a literature review but are not as exhaustive as a systematic review. See https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/rapid-evidence-assessments

References

- Anderson, G., and M. Cohen. 2015. “Redesigning the identities of teachers and leaders: A framework for studying new professionalism and educator resistance.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 23: 85.

- Ball, S. J., and C. Junemann. 2012. Networks, New Governance and Education. Bristol, Policy.

- Ball, S. J., C. Junemann, and D. Santori. 2017. Edu. Net: Globalisation and Education Policy Mobility. London: Routledge.

- Bamsey, V., J. Georgeson, A. Healy, and B. Ó Caoimh. 2020. Mapping the Landscape: Practitioners Views on the Early Years Foundation Stage. Watford, U.K: The British Association for Early Childhood Education.

- Blackmore, J. 2004. “Leading as Emotional Management Work in High Risk Times: The Counterintuitive Impulses of Performativity and Passion.” School Leadership & Management 24 (4): 439–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430410001316534.

- Börzel, T. A. 1998. “Organizing Babylon: On the Different Conceptions of Policy Networks.” Public Administration 76 (2): 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00100.

- Bradbury, A., and G. Roberts-Holmes. 2017. The Datafication of Primary and Early Years Education: Playing with Numbers. Abingdon, London, U.K: Routledge.

- Burt, R. 1978. “Applied Network Analysis: An Overview.” Sociological Methods & Research 7 (2): 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912417800700201.

- Campos Martinez, J., A. Falabella, J. Holloway, and D. Santori. 2022. “Anti-Standardization and Testing Opt-Out Movements in Education: Resistance, Disputes and Transformation.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30:132. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.7506.

- Chen, Z., D. Hursh, and B. Lingard. 2021. “The Opt-Out Movement in New York: A Grassroots Movement to Eliminate High-Stakes Testing and Promote Whole Child Public Schooling.” Teachers College Record 123 (5): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812112300504.

- Cook, I. R., and K. Ward. 2012. “Conferences, Information Infrastructures and Mobile Policies: The Process of Getting Sweden “BID Ready”.” European Urban and Regional Studies 19 (2): 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411420029.

- Crow, G. 2004. “Social networks and social exclusion: an overview of the debate.” In Social Networks and Social Exclusion: Sociological and Policy Issues, edited by P. In, A. Chris, G., and D. Morgan, 7–19. Aldershot: UK. Ashgate.

- (Department for Education). 2020. Development Matters: Non-statutory curriculum guidance for the early years foundation stage. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/development-matters--2

- DfE (Department for Education). 2017. “Primary Assessment in England.” Government Consultation. https://consult.education.gov.uk/assessment-policy-and-development/primary-assessment/supporting_documents/Primary%20assessment%20in%20England.pdf.

- Duke, K., and B. Thom. 2014. “The Role of Evidence and the Expert in Contemporary Processes of Governance: The Case of Opioid Substitution Treatment Policy in England.” International Journal of Drug Policy 25 (5): 964–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.015.

- Goldstein, H., G. Moss, P. Sammons, G. Sinnott, and G. Stobart. 2018. A Baseline without Basis: The Validity and Utility of the Proposed Reception Baseline Assessment in England. London: British Educational Research Association. https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/a-baseline-without-basis.

- Granovetter, M. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78:360–380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469.

- Hogan, A. 2015. “Boundary Spanners, Network Capital and the Rise of Edu-Businesses: The Case of News Corporation and Its Emerging Education Agenda.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (3): 301–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014.966126.

- Holloway, J., and D. Santori. 2022. “Legitimising Capital: Parent Organisations and Their Resistance to Testing in England.” Paper presented at Reformed Project conference. Barcelona, June 15-17

- Hursh, D., J. Deutermann, L. Rudley, Z. Chen, and S. McGinnis. 2020. Opting Out: The Story of the Parents’ Grassroots Movement to Achieve Whole-Child Public Schools. Stylus Publishing, LLC: Myers Education Press.

- Hutchings, M. 2015. Exam Factories? The Impact of Accountability Measures on Children and Young People. London: National Union of Teachers.

- LeCompte, M. D., and J. Preissle. 1993. Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research. 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press.

- Lingard, B., W. Martino, and G. Rezai-Rashti. 2013. “Testing Regimes, Accountabilities and Education Policy: Commensurate Global and National Developments.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (5): 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.820042.

- Lundin, M., and P. O. Öberg. 2014. “Expert Knowledge Use and Deliberation in Local Policy Making.” Policy Sciences 47 (1): 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-013-9182-1.

- Montero, L., C. Cabalin, and L. Brossi. 2018. “Alto Al SIMCE: The Campaign Against Standardized Testing in Chile.” Postcolonial Directions in Education 7 (2): 174–175.

- Moss, G. 2022. “Researching the prospects for change that COVID disruption has brought to high stakes testing and accountability systems.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30: 139.

- MTAS, n.d., More Than a Score: a grassroot’s toolkit for organising. Available at: https://www.morethanascore.org.uk/get-involved/

- Niesen, P. 2019. “Introduction: Resistance, Disobedience or Constituent Power? Emerging Narratives of Transnational Protest.” Journal of International Political Theory 15 (1): 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755088218808065.

- Parcerisa, L., A. Termes, A. Termes, and J. Collet-Sabé. 2022. “Why Do Opt-Out Movements Succeed (Or Fail) in Low-Stakes Accountability Systems? A Case Study of the Network of Dissident Schools in Catalonia.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30 (133). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6330.

- Pascal, C., T. Bertram, and L. Rouse. 2019. Getting It Right in the Early Years Foundation Stage: A Review of the Evidence. Watford: The British Association for Early Childhood Education.

- Perryman, J., S. Ball, M. Maguire, and A. Braun. 2011. “Life in the Pressure Cooker –School League Tables and English and Mathematics teachers’ Responses to Accountability in a Results-Driven Era.” British Journal of Educational Studies 59 (2): 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.578568.

- Pickett, B. L. 1996. “Foucault and the Politics of Resistance.” Polity 28 (4): 445–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/3235341.

- Pizmony-Levy, O., B. Lingard, and D. Hursh. 2021. The Opt-Out Movement and the Reform Agenda in U.S. Schools. Teachers College Record. 123 (5), https://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=23658Press.

- Pizmony-Levy, O., and N. G. Saraisky. 2016. Who Opts Out and Why? Results from a National Survey on Opting Out of Standardized Tests. 1–64. New York, NY: Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8K074GW.

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Reckhow, S., and J. W. Snyder. 2014. “The Expanding Role of Philanthropy in Education Politics.” Educational Researcher 43 (4): 186–195. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14536607.

- Roberts-Holmes, G. 2015. “The “Datafication” of Early Years Pedagogy: “If the Teaching is Good, the Data Should Be Good and if There’s Bad Teaching, There is Bad Data.” Journal of Education Policy 30 (3): 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.924561.

- Rodrigues, C. M. L., K. W. C. de Almeida, and M. U. Simões. 2022. “Disputes Around Assessments in Early Childhood Education in Brazil.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30 (134). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6456.

- Sabag, N., and Y. Feniger. 2022. “Parents’ Resistance to Standardized Testing in a Highly Centralized System: The Emergence of an Opt-Out Movement in Israel.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30 (135). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6328.

- Saraisky, N. G., and O. Pizmony-Levy. 2020. “From Policy Networks to Policy Preferences: Organizational Networks in the Opt-Out Movement.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 28:124–124. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.4835.

- Sisto, V., L. Núñez-Parra, A. López-Barraza, and L. R. C. Del Valle. 2022. “La rebelión de las bases frente a la estandarización del trabajo pedagógico. El caso de la movilización contra la Ley de Carrera Docente en Chile.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30 (138). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6460.

- Skedsmo, G., and M. K. Camphuijsen. 2022. “The Battle for Whole-Child Approaches: Examining the Motivations, Strategies and Successes of a Parents’ Resistance Movement Against a Performance Regime in a Local Norwegian School System.” Education Policy Analysis Archives 30 (136). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.30.6452.

- Standards and Testing Agency. 2019. Assessment Framework, Reception Baseline Assessment. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachmentdata/file/868099/2020AssessmentFrameworkReceptionBaselineAssessment.pdf.

- Stromquist, N., and A. Sanyal. 2013. “Student Resistance to Neoliberalism in Chile.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 23 (2): 152–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2013.790662.

- Travis, B. J., and K. Abaidoo-Asiedu. 2016. “Issue Networks: The Policy Process and Its Key Actors.” In Global Encyclopaedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by A. Farazmand, 3418–3423 . Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20928-9_2445.

- Urry, J. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Verger, A., and M. Curran. 2014. “New Public Management as Global Education Policy: Its Adoption and Rec-Contextualisation in a Southern European Setting.” Critical Studies in Education Policy 55 (3): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014.913531.

- Verger, A., C. Fontdevila, and L. Parcerisa. 2019. “Reforming Governance Through Policy Instruments: How and to What Extent Standards, Tests and Accountability in Education Spread Worldwide.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 40 (2): 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1569882.

- Wang, Y. 2021. “Examining the Actor Coalitions and Discourse Coalitions of the Opt-Out Movement in New York: A Discourse Network Analysis.” Teachers College Record 123 (5): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812112300506.