ABSTRACT

Following calls to ‘bewilder’ (Snaza 2013) the pioneers of early education, this article positions Montessori pedagogy as a ‘desire path’ that acts as resistance to normative policy-driven pathways in early childhood education and care. Desire paths are alternative tracks made aside from officially established walking routes. In this paper I think with the metaphor of pathways and desire paths positioning an educator’s choice to practice Montessori pedagogy as an approach which wanders outside of mainstream qualifications and education. To do this, I take fragments of a professional life story that chart the agentic nature of choosing Montessori pedagogy as a way to problematise how walking that desire line challenges, and defies normative pathways. I also propose a re-reading of Montessori’s pedagogy, not as pioneering but as nomadic, and suggest that social desire paths enable Montessori education to be viewed as multiple, situated, alternative tracks to prescribed pathways.

Introduction

Traveller, your footprints are the only road, nothing else.

Traveller, there is no road;

you make your own path as you walk.

Antonio Machado (1875–1939) (Citation2003)

Montessori pedagogy has become enmeshed in glocalised discourses reflecting both its international reach and multiple, local interpretations. Initiated by Doctor Maria Montessori (1870–1952) this distinctive pedagogy has moved beyond its original context in early twentieth-century Rome and has extended its impact and reach across the globe. As of 2022 there are at least 15,000 Montessori schools documented in 154 countries around the world (Debs et al. Citation2022).

Based on her observations, Montessori asserted that children move through planes of development and sensitive periods, with their self-construction fostered through self-directed activities in a specially prepared learning environment (Marshall Citation2017). In contemporary contexts, Montessori pedagogy is subject to multiple interpretations by numerous local, national, and international organisations and there is much ongoing debate about how the approach is enacted with reference to authenticity, fidelity, and cultural responsiveness (Murray and Daoust Citation2023).

Although a range of practices are enacted under the term ‘Montessori’, the Association Montessori Internationale (Citationn.d.) cite the following features as hallmarks of authentic Montessori practice:

Mixed age classrooms – for children. e.g., 2 ½ or 3 to age 6.

Children’s choice of activity from within a range of options.

Uninterrupted ‘work cycle’ – ideally three-hour blocks.

A constructivist or discovery approach with children learning hands on from materials rather than by direct instruction.

Specialised materials design by Montessori and collaborators.

Freedom of movement within the classroom.

A trained Montessori teacher.

As a figure, Maria Montessori is often ascribed pioneer status, featuring in textbooks and educator syllabi as an innovator in early childhood education. She has been described as a ‘pioneering giant’ (Boyd Citation2018) and her work as ‘ground-breaking’ (Sirem Citation2022). I want to trouble that framing of pioneer status and the notion of the pioneering spirit offering instead a reconceptualisation of Montessori’s approach in terms of wayfaring. I propose that ideas of nomadism and wayfaring offer more explorative and emergent framings of this pedagogy and its contemporary enactments. In exploring these ideas, I draw on the multiplicity of theories of nomadism rather than a singular conceptualisation. This paper therefore offers a perspective of Montessori’s thinking and writing as a way to critically consider dominant discourses in the current early childhood education policy. As such, I offer three moves:

a re-reading of Montessori pedagogy as a lens through which to critically consider dominant discourses in English curricular and workforce policy.

An interpretation of one Montessori educator’s desire path as resistance to normative pathways of educator qualifications, learning environment, curriculum, and assessment.

A rethinking of Montessori pedagogy, not as pioneering but as nomadic.

Whilst Montessori education has a global presence, I draw on my own experience and research as a white, male, British, Montessori-trained early childhood educator who qualified and practised in England. I situate this new perspective alongside data drawn from a previous study (Archer Citation2020) of the education and professional identities of early childhood educators in early twenty-first century England.

A road less travelled: Montessori Education in UK context

To contextualise this thinking and the research which informed this analysis, I offer some background on Montessori qualifications and early childhood workforce policy in England. In a wider UK context, Montessori pedagogy is overwhelmingly found outside of public education and has historically been the preserve of voluntarily and privately run early childhood education and care (ECEC) centres and schools. It is often defined by its exclusivity (BBC, Citation2016). Whilst much Montessori education is found in more affluent areas of the UK, there exist a number of Montessori early childhood settings in low-income areas (Archer Citation2022c).

With (early) education policy devolved to the administrations of the four UK nations, it is important to highlight fundamental differences in curricula, regulation, funding, and workforce policy across the United Kingdom (Georgeson et al. Citation2022). This article draws on my prior policy analysis, empirical data collected in an earlier study and my professional knowledge of Montessori education in an English context. Educators who work in English Montessori ECEC centres conventionally pursue pedagogically specific qualifications, typically a Montessori early childhood diploma. However, despite their accreditation these qualifications lack currency in mainstream centres. As a result, it has been argued that proponents of this pedagogical approach have typically operated on the margins of mainstream early childhood education (Eacott and Wainer Citation2023; Whitescarver and Cossentino Citation2008) and their qualifications are poorly recognised (Payler and Bennett Citation2020).

The provision of Montessori initial education for educators in the UK has evolved significantly and is complex with multiple teacher education providers subscribing to different interpretations of the pedagogy. Initially, Montessori teacher education was first delivered by Dr Maria Montessori in 1919 in London. Today numerous Montessori teacher education providers offer an array of qualifications. Distinct from initial teacher education for mainstream schools, Montessori initial teacher education takes the form of a range of qualifications at multiple levels delivered by both Higher Education Institutions (HEI) and private training organisations. Montessorians, who typically work in the UK’s private and voluntary sectors of ECEC hold qualifications at different levels, including ‘entry’ level, graduate and postgraduate levels. Some Montessori qualifications have a degree of international currency whilst others are more context specific, meeting UK regulatory criteria. There now exist several different England-specific Montessori education qualifications situated within an even more complex framework of government approved early childhood qualifications (n = 83) (Department for Education, Citation2022b). To further complicate this landscape, some Montessori qualifications are considered ‘full and relevant’Footnote1 on a government list of accepted qualifications and others are not (Department for Education, Citation2022b). This has implications for educator employment and their deployment within staffing ratios of early childhood settings.

Official walkways: workforce policy and qualifications

These Montessori qualifications are situated within a long history and a broader context of early childhood initial education and professional development. English early childhood workforce policy has long prescribed qualification pathways for educators. These qualification routes have seen numerous changes in recent decades as periods of political interest and disinterest in early education and care have shaped the landscape. Notably, there has been recent critique about the lack of clear and coherent policy focus for the development of early childhood qualifications (Lawler Citation2020; Nutbrown Citation2021; Pascal, Bertram, and Cole-Albäck Citation2020).

In addition to the fluctuating policy attention, the ‘mixed market’ of ECEC provision and differing regulatory requirements between the state maintained and private and voluntary sector provision have created inconsistencies in qualification requirements. It has been argued that existing qualification routes perpetuate disparities between educators employed in the state maintained and private and voluntary sectors (Osgood et al. Citation2017).

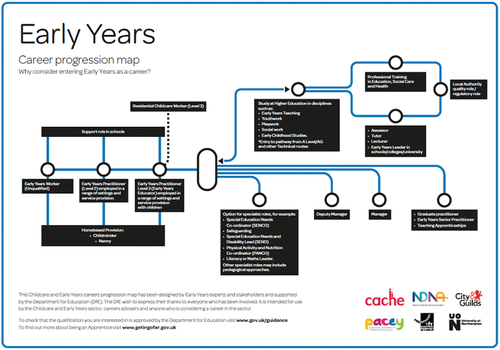

Recently, these pathways have been detailed in a government sanctioned ‘career progression map’ which couples some approved qualifications to a limited number of professional roles (see Appendix 1). The map was produced as:

… a tool for staff to plan their careers and for those interested in working in the sector to see the range of jobs and opportunities on offer. The map provides detailed information about different early years job roles, entry points and progression routes.

This map seeks to support early childhood educators to navigate a highly complex terrain of qualification levels and the types of early education-related roles which such qualifications enable them to undertake. Notwithstanding the accessibility of the infographic, I argue that such a policy technology acts as a process of credentialising (Archer Citation2022b) across professional roles. This credentialising serves to establish the credibility and validity of some qualifications (and roles) according to government prescribed standards. These form part of wider ECEC centre regulation which stipulates which qualifications are acceptable and which are not (Department for Education, Citation2022b). Montessori qualifications are excluded from this map.

In order to further interrogate the relationship between the Montessori pedagogical approach in England and the relationship between policy directives and educator experiences, I turn the focus, initially, to a critical analysis of early childhood workforce policy.

Critical cartography to map the territory and the absences

Osgood writes:

When governments are understood to invest in particular discourses to serve specific political agendas it becomes important to dismantle those discourses and assess their effects upon the subjective professional identities of those working within nurseries.

Such an analysis provided an impetus for a previous study (Archer Citation2020) and my critical turn to analysing contemporary early childhood workforce policy (Archer Citation2022b). My analysis concluded how the policies of standard setting, credentialising and surveillance create discursive borders which are established and maintained to create the ‘ideal’ professional identities of early educators. Drawing on this and research informed by the reconceptualised critical theory work of Kinchloe and McLaren (Citation2000) who explore hegemony, ideology, and discursive power, I note:

criticalists begin to study the way that language in the form of discourses serves as a form of regulation and domination … in this context power discourses undermine the multiple meanings of language establishing one correct reading that implants a particular hegemonic/ideological message … This is a process often referred to as discursive closure.

Working in this tradition and seeking to critically analyse the ‘career progression map’ I turn to critical cartography to discern power discourses and discursive absences in the map. Critical cartography, according to Firth (Citation2015), is the idea that maps – like other texts such as the written word, images or film – are not (and cannot be) value-free or neutral. Maps reveal and perpetuate relations of power, often in the interests of dominant groups.

Maps are neither mirrors of nature nor neural transmitters of universal truths. They are narratives with a purpose, stories with an agenda. They contain silences as well as articulations, secrets as well as knowledge, lies as well as truth.

Whilst much critical cartography ‘as a tool of socio-spatial power’ (Harley Citation1992) is located in disciplines of geography and environmental sciences, this approach, grounded in critical theory, lends itself to analysis of conceptual as well as land cover maps. As such, cartographic analysis affords a critical reading of the aforementioned ‘career progression map’.

Working with this approach to the career map reveals a normative, linear framework of qualifications which delimits the initial education territory. Career progression, according to the framework, couples a limited number of endorsed qualifications with specific professional roles. However, many approved qualifications and the diversity of professional roles are absent from this over simplified map. This highlights the discursive closure and silence in the territory depicted on this policy technology. I argue that such cartography results in forms of complexity reduction and diversity reduction of initial education (and the professional roles this qualifies educators for) thereby opening a space for some educator identities (and pedagogies) and closing down others. Such prescription results in cartographic silences in government policy around Montessori education and professional development outside of these ‘norms’. Such silences serve to ‘cartographically categorically ignore or discount disempowered peoples and their knowledges in making maps’ (Krygier and Wood Citation2009, 10).

This analysis also reveals how prescribed pathways through a government endorsed ‘career progression map’ create forms of discursive closure around the ‘ideal’ professional identities of early educators. That is to say, through standards setting and credentialising, the ‘ideal’ early childhood educator is envisaged, one who meets government sanctioned standards and qualifications. In this way, the discursive construction of roles such as ‘early years teacher’, ‘early years educator’, defined by these standards, present particular versions of who early childhood educators should strive to become, and ‘what occupations they view as possible and not possible’ (Laliberte-Rudman Citation2015, 55). Such discursive closure creates challenges for early childhood educators wishing to traverse other routes and assert subjectivities based on their agency, relational ethics, and preferred pedagogy. As a result, such a policy requires English Montessori educators to navigate a qualifications terrain with a map which is both partial and exclusionary. This analysis has established policy context and includes policy critique to analyse dominant discourses in workforce policy. I now turn to empirical data to look beyond the map and reflect on the agency of (Montessori) early educators.

Wayfaring on desire paths

Wayfaring helps us find what we seek in the spaces between the roads.

Given that critical cartography analyses maps as they reflect and perpetuate relations of power, I note the limitations of such maps. In responding to these limitations, and with interest in the lived experiences of those excluded by such a map, I look to the agency of educators and the notion of the alternative routes along which they travel.

In this article, I work with the notion of ‘desire paths’ as a heuristic. Desire paths are ‘paths and tracks made over time by the wishes and feet of walkers, especially those paths that run contrary to design or planning. Free-will ways’ (McFarlane Citation2018). The origins of this term have been traced back to the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who wrote of ‘lignes de désir’ in his 1958 book ‘The Poetics of Space’ (Bachelard and Jolas Citation2014). Such desire paths or lines are trodden and unbiased towards existing constructed routes. They ‘indicate yearning’ (Brown Citation2003) and are expressive of the routes we want to take as an alternative – or at least in addition to – the established footpaths that were planned. Such paths are usually most noticeable in parks and woodlands where people often feel free to bypass existing tracks and take or forge the most expedient path to where they want to go. They might be read as visible signs of agency and autonomy. In the book ‘Two Degrees West’, Nick Crane (Citation1999) describes such paths as:

… the imprints of ‘foot anarchists’, individuals who had trodden their own routes into the landscape, regardless of the intentions of government, planners, and engineers … . They were expressions of free will, ‘paths with a passion’, and an alternative to the strictures of railings, fences and walls that turned individuals into powerless apathetic automatons. On desire paths you could break out, explore, ‘feel your way across the landscape.

For Furman (Citation2012) who has spent years looking at desire paths, they tell us something about ‘the endless human desire to have choice; the importance of not having someone prescribe your path’ (115). Such desire paths or lines have also been described as forms of resistance and ‘civil disobedience’ (Ballard, Joyce, and Muller Citation2012). Using this heuristic, I argue that Montessori pedagogy is an approach to education which operates outside of mainstream education (at least in an English context) and one which reflects the idea of wayfaring on a desire path: an alternate route to well-trodden walkways.

For this study, desire paths as a heuristic also afford greater focus on the agency of the walker/educator. This reading shifts away from the constraints of a truncated representation of qualifications and professional roles to recognising not only the choices an educator makes beyond the map but their active role in forging their own path. As Ingold (Citation2021) writes:

Every trail, however erratic and circuitous, is a kind of lifeline, a trajectory of growth. This image of life as a trail or path is ubiquitous among peoples whose existential orientations are founded in the practices of hunting and gathering, and in the modes of environmental perception these entail. Persons are identified and characterised not by the substantive attributes they carry into the life process, but by the kinds of paths they leave.

In order to further explore this notion of desire paths in the context of this study, I look to an individual educator’s reflections of working with a Montessori pedagogy and of expressions of agency and resistance.

Amy’s desire path: Montessori pedagogy as resistance

This paper draws on data from an interview with a Montessori qualified educator, one of a series of interviews (n = 18) from an empirical study which gathered the professional life stories of early educators in England in 2019. Amy (pseudonym) was an early childhood educator in a day nursery whose own career ‘desire path’ illustrates her choice to engage with and enact a Montessori pedagogy. Amy qualified as a Montessori educator and recently completed a master’s degree in early childhood education. At the time of the interview, she was employed in a Montessori nursery in the South of England.

In relaying her professional life story, Amy detailed how Montessori pedagogical values informed her work and her subversion and disruption in her role in an ECEC centre. She illustrated this through recollections of occasions when she had challenged colleagues in practice and the management of the centre on policy design and implementation. I explore these further through the themes of the role of the educator, the learning environment, curriculum and assessment.

Role and identity of the educator

Throughout the interview, it was clear that Amy positioned herself as fracturing a professional subjectivity which was shaped through policy discourses. She formed an agentive subjectivity through challenging conventional qualification pathways:

I think the emphasis on qualifications over experience needs changing. It’s ridiculous isn’t it that I could get on a master’s degree based on my experience and it was a huge learning curve. But they still say I can’t be a room supervisor because I don’t have a level 3 qualification, but an eighteen-year-old can come out with a Level 3 with no ability to reflect on their practice whatsoever.

Here, Amy is confronting the contours of the career progression map whereby prescribed (pre-degree level) qualifications are built into regulatory requirements for a ‘room supervisor’ role to the exclusion of a higher-level postgraduate qualification. Her contention is that her master’s degree has enabled greater reflection and reflexivity and yet leaves her unqualified for a specific role within the nursery. Notably, neither her master’s degree nor her Montessori qualification meets the regulatory requirements for a room supervisor as stipulated in regulations. Amy also asserted both a policy critique and a frustration at a lack of autonomy:

We are not given the freedom to use all that understanding and knowledge that we develop, nor trusted to support each other in implementing it…bombarded with opposing expectations even within government documentation …

She continued:

We are encouraged to become more professional by gaining prescribed educational qualifications yet are still earning minimum wage … . I would say half of the workforce have early years degrees and they are still on £7.80 per hour …

Amy’s feelings of being undervalued and underpaid are explicit. She acknowledged the structural discourses around the status and pay of early educators and critiqued the disconnection between policy rhetoric and her lived experiences. Further, in national occupational standards policy, the notion of educator ‘responsibilities’ are only related to health and safety and accidents and emergencies. There is a notable absence of reference to ethical practice and wider pedagogical responsibilities.

I argue that Montessori education is defined by a deep respect for the child (Montessori Citation2012) and an ethic of care. It is a conspicuously relational practice:

Based on a relationship of trust, the Montessori teacher supports children’s relational development with each other also, helping students to develop increasing self-discipline and self-control, and only stepping in to help when necessary.

This definition sits in contrast to Amy’s feelings of not ‘[being] trusted’, as it appears she grapples with the expectations of the ‘path’ of standards and her Montessori education.

Environment

Qualification standards for an Early Years Educator (Department for Education, Citation2023a) oblige educators to ‘Provide learning experiences, environments and opportunities appropriate to the age, stage and needs of individual and groups of children’. Notably, in statutory terms, the educator’s responsibilities for the learning environment do not go further than this. Conversely, a Montessori pedagogue is responsible for creating ‘a hands-on, self-paced, collaborative, and joyful classroom’ (Association Montessori Internationale Citationn.d.). The ‘prepared environment’ is described as:

The visible environment includes accessible furniture, a variety of workspaces, and scientifically designed materials displayed for free choice of activity. These materials support concrete exploration which leads to both practical skills and abstract knowledge. Such exploration is initiated through minimalist lessons offered by the trained Montessori teacher followed by hands-on, self-directed, and self-correcting learning which can be individual, collaborative, or peer-to-peer.

However, Montessori’s sensorial education goes beyond offering the child exposure to new sensory experiences. Rather, through the aesthetics of the physical environment, the sense of calm and order created through carefully displayed and self-correcting learning materials, it is suggested this helps the child to distinguish, classify and absorb the information received by means of the senses (Montessori Citation1917, 203).

When discussing her experiences, Amy rejected the ‘busyness, the chaos’ of other early childhood environments in which she had worked in favour of the organisation and ‘sense of calm’ which, she found and created in a Montessori education centre. She actively resisted moves to ‘continually add to the resources’ (as advised by external advisers and consultants) and ‘trusted in the Montessori materials’. It appeared that in shaping and resourcing the physical environment thus, Amy was reflective, but also principled in her pedagogical decision-making. Indeed, rejection of external advice and the maintaining an authentic Montessori environment (as she perceived it) were further examples of resistance to normative expectations.

Curriculum policy and enactment

In addition to, and interwoven with her understanding of her professional identity and the Montessori environment, Amy also critiqued the English Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum from her position as a Montessorian:

I think if you look back on how it [initial 2008 version of the EYFS framework] was approached, who was involved in it, the writing of it, and it was pretty transparent and what kind of philosophies were at play and now you look at the most recent version − 2017 – and you can’t find out who was involved, what theories are involved. So, it makes you think it is very much a Conservative, neoliberal economic agenda

and that actually children are not being seen as developing human beings but as potential economic units that will get exam results and take their place in the workforce.

I think what’s interesting is I worked in another nursery for four months and I just couldn’t bear it. The influence that the EYFS had on practice that was not mediated by Montessori or anything else that was separated from it, it was so clear how destructive it could be and how if its applied, how the government want it to be applied, absolutely, it became a tick list for children.

Amy’s analysis of ‘you can’t find out who was involved, what theories are involved’ reflects her perception both of a lack of transparency in policy formation, but also a lack of recognition of educational thinkers and a long heritage of multiple theories in the evolution of early childhood education and care. Her assertion that these policy texts do not reflect their histories, nor the influence of educational thinkers is reflected by Clough:

so many documents have been published that seem to come out of nowhere, no references to the work they draw on, no acknowledgement of whet went before … Indeed now that everything is published ion the internet, the policy archaeology may well become more and more difficult to trace …

Notably, several international early childhood education curricular frameworks detail multiple pedagogical theories and their influence on ECEC thinking and practice. Australia’s Early Years Learning Framework (Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Citation2009), Singapore’s ‘Nurturing Early Learners’ (Ministry of Education, Citation2013), Scotland’s ‘Realising the Ambition’ (Education Scotland, Citation2020), amongst others, all explore a range of educational thinkers, acknowledging their formative influence on contemporary pedagogies. In addition, the sector-led development of non-statutory guidance in England in the form of ‘Birth to Five Matters’ (Early Years Coalition, Citation2021) offers a fertile source of theory and research led inspiration for practice. These policy texts explicitly recognise the rich, plural, divergent traditions and influences on early childhood education and care practices.

Conversely, I argue that the English Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework is explicitly a standard setting document. There is an emphasis – notably through the proliferation of ‘musts’ in the document – on standards compliance. There are no explicit references to underpinning theories nor recognition of educational thinking (pioneer or otherwise). As Amy notes, there is no acknowledgement of how theories can ‘mediate’ policy.

In the Department for Education commissioned international research on early childhood pedagogy, Wall et al. (Citation2015) suggest that England does ‘not adhere to one certain pedagogical approach at national level’ (5). The implication is that an English ECEC system embraces multiple pedagogical approaches to early childhood education and care. I argue that this rhetoric of plurality contrasts with the reality of policy technologies which do not embrace this diversity of pedagogy. This results in particular pedagogical approaches becoming framed as ‘alternative’ to normative pathways.

Of note is the document ‘Unhurried Pathways’ (Early Childhood Action, Citation2012) which offered a ‘new framework for early childhood’. This document, developed by early childhood advocates was developed as the statutory EYFS framework was being ‘revised’. The document engages with a number of different theories including Montessori’s:

Unhurried Pathways, sets out an approach to early childhood which aims to shift the discourse about young children away from a statutory, ‘politics-centred’ approach, and towards one in which professionals working in the field reclaim their autonomy and professionalism – such that early years practice can be grounded in unique local contexts, with diversity actively welcomed and embraced, rather than being undermined by an ideology of uniformity, mechanical compliance and ‘normalisation’.

This framework explicitly rejects discourses of the statutory, celebrates educator agency and autonomy and notably emphasises the multiplicity of pathways in early childhood education and care. It celebrates plurality and diversity of approaches in ECEC recognising the importance of the local, emergent, contingent, and explicitly unhurried approach to young children’s experiences.

Assessment

Amy’s desire path was formed both through her advocacy of a Montessori inspired approach and through her rejection of numerous normative and performative frameworks and their constitutive power. Through her choices and actions, she trod another path enacting Montessori pedagogy and multiple micro-resistances (Archer Citation2022c) against the performativity of contemporary policy demands. An example of such micro-resistance took the form of Amy rejecting normative developmental milestones for assessing young children as ‘a cohort’ in the Reception Baseline AssessmentFootnote2

Rather, Amy chose to respond:

So, when information about baseline came out, I asked our manager and Director whether they minded if I wrote a little article for parents because they would be taking their children from our setting into baseline assessment and they don’t know about it. And maybe they would just think, well this is what happens at school. But actually, it’s not inevitable, you don’t have to put your child through it.

Amy articulated how her rejection of this assessment of ‘a cohort’ of children through the baseline assessment was at odds with her view of the ‘unique child’. Whilst Amy appears to adopt a developmentalist perspective (embracing the notion of ‘sensitive periods’ from her Montessori training) she is resisting the state-imposed framework and its limited and limiting imaginary nature of the child.

In addition, Amy rejects the dominant discourse of school readiness with its prescribed trajectories linked to discrete, limited summative measures of a ‘good level of development’ (Department for Education, Citation2023b). Rather, she articulates an alternative narrative of early education not as preparation for school, but as an ‘aid to life’Footnote3. In this way, Amy expresses a perspective of Montessori early education as ‘preparation for life’ as opposed to preparation for school, rejecting the dominant school readiness discourse. She presents Montessori education as a mode of resistance to the binary of the ready/unready child (Kay Citation2018) describing a wider approach to both pedagogy and assessment through Montessori education as ‘starting from the child rather than the tick list’.

Whilst the linear trajectories of developmentalism remain discernible in her approach, Amy signals a more expansive perspective to assessment in which observations of individual children and sensitive, responsive pedagogy take precedence. As Osgood and Mohandas (Citation2022) attest ‘Montessori’s views on observation are inconsistent but tend to focus on ‘what observations can tell us about the child, in the moment, against some narrow imaginary of the developmental child’. The relational approach to assessment, which Amy advocates, tells ‘richer accounts of “child” through a relational ontology’ (Osgood and Mohandas Citation2022, 305). Indeed, Amy advocates for a ‘rich record’ of the child’s holistic development over the classification of children through politically determined summative assessments. Her perspective and prioritisation of the individual learning journeys of each child were core element of her work, which her Montessori education had inspired.

As part of a discussion on assessment, Amy also recounted an interaction with an Ofsted inspector who was inspecting the nursery where she worked: ‘… the Ofsted inspector said I want to see every child with a graph like this [indicates a line graph rising diagonally upwards left to right] I replied: “but it doesn’t go like that”’. Here, Amy is describing how she was held accountable for a particular version of children’s development during an inspection and expected to produce data on how her performance resulted in normalised and uniform trajectories of children’s progress. This conveys the power of a dominant discourse in prescribing and holding an educator to account for normative development and outcome accountability through disciplinary means. Amy’s rejection of this perspective is rooted in the different path she walks. She points to the complex, contingent nature of children’s learning, but also her prioritising of accountability to child and family over external accountability.

Reviewing the fragments from Amy’s professional life story, I argue Amy has drawn on her Montessori education to resist uniformity and reclaim her autonomy as expressed above. She perceives her Montessori pedagogy and the ethos which informs her work as ‘mediating’ the effects of policy incursions. She expresses both her agency and resistance in critiquing dominant policy discourse and forging her own path. Amy’s responses, including a series of micro-resistances (Archer Citation2022a) reflect the subversive way in which early educators often ‘circumvent, mediate and disrupt demands upon them’ (Archer and Albin-Clark Citation2022, 22). Following this analysis, I turn to consider the agentic nature of Amy’s Montessori pedagogy as walking a desire path and how this might be read as nomadism.

Not pioneering but nomadic wayfaring

Your wayfaring journey should aim for beauty and richness of experience, not just direct travel connection. Because it can.

The Special Issue call for papers referred to troubling the ideas of ‘pioneer’ and ‘pioneering practices’. Such terms allude to oppressive forces which colonise lands and indigenous populations. These are concepts rooted in settler colonialism with all the implications of human, economic and environmental exploitation. They speak of acquisition, extraction and the repression and displacement of indigenous peoples and cultures.

With due respect to the innovations of these historical educators and thinkers, such connotations of pioneering are problematic in framing this work. It can be argued that the expansion of the Montessori approach to Global Majority and Minority countries is seen as a colonisation. Indeed, the global circulation of Montessori education in the early twentieth century (informed by centrally defined and tightly controlled teacher education programmes) might be read as colonisation in practice. Mohandas (Citation2023) draws attention to the colonial capitalist context in which the Montessori approach arose, and the ‘civilizing mission’ embedded in the origins of the project. Further, they highlight how Western colonial logic is woven into the developmentalist approach of Montessori pedagogy.

Notwithstanding this important critique, I want to highlight the importance of glocalised interpretations and enactments, where this worldwide approach comes into dialogue with local contexts. I draw on a recent example of a project which hybridises indigenous knowledges with a Montessori approach at the Inuktitut Preschool in Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) Nunavut, Canada. The preschool blends Montessori methods with Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit ways) and Inungnuinniq (traditional Inuit child-rearing). The founder describes their work:

People from outside might say ‘this is a Montessori programme implemented in an Inuit community’, but we’re turning that round. Actually, it is old, old knowledge here at Pond Inlet and that is what we are reflecting in the pre-school.

Thus, I suggest that despite an argument suggesting the colonising prospect of such an approach, Montessori education continues to ‘land’ differently in multiple contexts and remains open to situated interpretations and enactments. This is a glocalised pedagogy ‘suggesting the customisation and adaptation of global perspectives to local conditions’ (Robertson Citation1995, 26). Further, I argue that a re-reading or ‘bewildering’ of the notion of Montessori as pioneer enables a new understanding which rejects the ideas of ‘pioneer’ and ‘pioneering’ and recasts this work as wayfaring; as nomadic. In doing so, and returning to Amy’s work, I consider her desire path of Montessori education as wayfaring nomadism.

Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) propose ‘nomad thought’ as a different theoretical perspective which embraces multiplicity over conventional hierarchical systems which are determined, ordered and classified. Rather, nomadology is defined by the micropolitical or deterritorialised, that which is free, unlimited, and unspecified. As Aldea (Citation2014) elucidates:

under the nomadic order … a number of people are scattered across an expanse of land, without clear borders or exclusive ownership. The route from point A to point B is not determined in the same way as under the sedentary order. Rather, stopping places are subordinated to the journey itself …

In a study on student teachers, Leafgren (Citation2018) describes participants as having ‘a nomadic imagination towards radical non-compliance’ (187). These ‘disobedient professionals’ revealed a nomadic inclination for resisting normalising structures of power that authorities impose through policy technologies. As Leafgren notes:

‘Nomadism’ is a way of life that exists outside of the organizational ‘state’. The nomadic way of life is characterized by movement across space, which exists in sharp contrast to the rigid and static boundaries of the state.

According to Tally (Citation2010, 15) ‘Nomad thinkers are like sudden, bewildering eruptions of “joyful wisdom” in an apparent continuum of stable meanings, standard commentaries, settled thought’. These understandings of nomad suggest notions of wayfaring, openness, resistance to conventions and the embracing of a radical imagination.

Returning to Amy’s professional life story, I propose that Amy’s journey is one of the wayfaring, of walking unconventional routes to well-worn paths. Amy’s nomadism can be seen in her ‘radical non-compliance’ in refusing to endorse the Reception Baseline. Indeed, in terms of assessment, for Amy, the stopping places (of summative assessment) are subordinated to the journey itself. Her thoughts on assessment as ‘richer accounts of the child’ suggest she is a nomad thinker who is disrupting conventions and using her Montessori pedagogy to envisage how such an approach can mediate or mitigate reductive assessment technologies.

Amy’s pedagogical approach and her rejection of limiting policy technologies (e.g., curricula and assessment regimes) moves beyond critique. I suggest that Amy’s thinking and her work illustrate wide awakeness (Greene Citation1995), scepticism, and a willingness to operate beyond conventions. Amy’s Montessori informed pedagogy is disruptive and reflects a transgressive imagination as she envisages an ‘alternative’ way of working in early childhood education. Adopting Montessori principles related to the learning environment, curriculum and assessment, the imaginary of the child, Amy positions herself ‘outside the static boundaries of the state’ (Leafgren Citation2018, 190). Thus, her work might be reconceptualised not as pioneering practice but as a nomadic. Indeed, her nomadic disposition for rejecting the power discourses in numerous policy technologies is illustrative of a ‘nomadic resistance’ (Osgood et al. Citation2013).

The qualifications she had undertaken, the modes of assessment she rejected and those she adopted coupled with the Montessori pedagogy she chose to enact reflect an alternative desire track, and she wandered beyond prescribed routes. Through her words and actions, Amy expresses a form of ‘critical agency’ (Rebughini Citation2018) where action is oriented both against and beyond the situation. In terms of negation, Rebughini puts forward the notion that critical agency ‘stems from a refusal to adapt oneself’ (7). Drawing on Foucault’s concept of parrhesia, understood as truth telling and a resistance to acquiescence, Rebughini develops the notion that critical agency is also simultaneously read in an affirmative sense, of looking beyond current situations and creating transformative alternatives: In this regard, the negation of reality is not a refusal, a pure act of resistance, but a search for an alternative way to know and to act (Rebughini Citation2018, 7). The desire path, which I perceive Amy walks, is both as an expression of agency and ‘yearning’ (Brown Citation2003) but also one of the resistance. It is a path which rejects normative pathways in search of personal and professional meaning.

Future social desire paths?

Work by Nichols (Citation2014) explores the notion of social desire paths as ‘instances wherein individual interests and desires collectively, but independently, make imprints on the social landscape over time’ (167). Such social desire paths focus on micro-level actions considering moves driven by individual agencies whilst also considering the implications and meanings behind why actors forge these alternative tracks. Social desire paths emerge when the existing routes do not meet the needs or aspirations of individuals or groups. Examples of social desire paths include when residents choose one-by-one to relocate from a particular community or when educators find creative ways to circumvent regulations. When multiple, independent individuals react to conventions, norms and structures in related ways, social desire paths are made. They are independent and plural yet also collective endeavours.

In the context of this exploration of contemporary early childhood policy, this social desire path analysis discerns the routes that organisational structures and associated policy technologies (such as the career progression map) do not recognise or even exclude. This analysis provides a means to perceive the actions of individuals, in this case, Montessorians as following alternative but plural pathways reflecting the situated variations in the nomadism they exhibit. This prompts additional questions about the motivations for pursuing Montessori desire paths and the need for further research in understanding the impetus of Montessorians in pursuing these paths rather than well worn, prescribed routes.

Conclusion

This paper has positioned Montessori pedagogy as a ‘desire path’, a path of resistance and as disruption to normative policy driven pathways in early childhood education and care. Deploying critical cartography, I analysed a government sanctioned ‘career progression map’ as presenting limited (and limiting) qualification and career pathways for early childhood educators in England. This analysis highlighted both the discursive closure around professional roles and the absences of many qualifications from the map. I concluded that with no reference to Montessori qualifications (or indeed any other pedagogically specific qualifications) the map is partial and exclusionary.

In addition, from an analysis of empirical data (a professional life story interview) three assertions are made. First, I have argued that in a contemporary English context Montessori pedagogy can be viewed as a pathway alternative to government sanctioned routes detailed in an official career progression map. Amy’s critique of government frameworks and assertion of Montessori pedagogy as mediating policy was illustrated in multiple micro-resistances against the performativity of contemporary policy demands.

Secondly, I propose that the desire path Amy chooses, and walks is a path of resistance. Amy’s words are read as a rejection of the limitations of the career map. Rather, she dispenses with the conventions of prescribed routes and rejects much of the discourse which underpins the map. She not only forges a different path in terms of chosen qualifications but draws on her pedagogical values to actively resist numerous policy incursions. Amy enacts a pedagogy of resistance to statutory curricular, assessment and inspection regimes articulating both her frustration and objection to dominant discourses in these policies. Through numerous challenges and micro-resistances (Archer Citation2022a) Amy disrupts demands upon her and asserts a different subjectivity.

In addition, bewildering pioneering thinking and practices results in a rereading of Montessori pedagogy as nomadic. Rejecting claims of a pioneering spirit and pioneering practices, rather I suggest that Montessori education reflects a wayfaring and tenets of nomadism. Drawing on work by Leafgren who describes the ‘nomadic imagination towards radical non-compliance’ (Citation2018, 187) I analyse Amy’s responses as nomadic. In her account of learning and working in contemporary early childhood education and care, Amy conveys not only a rejection of many policy conventions and demands upon her but a critical agency in walking a ‘Montessori path’.

Finally, I recast this path as social desire paths. Beyond Amy’s wayfaring there exists local, national, and international communities of educators inspired by Montessori pedagogy. Such a movement might describe a community subscribing to a pedagogy collectively wayfaring social desire paths. Nichols (Citation2014) highlights how social desire paths highlight viable alternatives to existing social structures. They are traversed individually and collectively, and can be perceived as ‘elective easements’. As Macfarlane (Citation2012) writes ‘Paths are human; they are traces of our relationships’. (81).

Notably Nichols (Citation2014) suggests

social desire paths are connected to values. The behaviours that drive alternative use of formal structures that create social desire paths are rooted in a prioritization of values not represented or supported in existing structures.

In terms of contemporary Montessorians, recognising that shared values might underpin social desire paths arguably offers solidarity in a movement which has operated on the margins of mainstream education (Eacott and Wainer Citation2023). The desires and choices of individual Montessori educators are imprinting paths on the landscape, and the recognition of these paths can lead to actions that have direct implications for policy and practice. Further research deploying social desire path analysis to consider any shared values of Montessorians and their motivations to walk these desire paths would illuminate this terrain further.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. ‘Full and relevant’ qualifications are defined as qualifications that demonstrate depth and level of learning appropriate to specified outcomes of full early years, childcare or playwork qualifications as determined by the Department for Education.

2. Reception Baseline Assessment (in 2018) was a summative assessment in children’s first year of formal schooling (at age 4 or 5) and was intended to ‘provide a baseline for measuring the progress children make throughout their primary school career’. The RBA is designed to provide a measure of children’s performance at a cohort rather than an individual level. The assessment therefore focuses on the information needed to provide a reliable and valid baseline for progress measures which will be reported at the end of Key Stage 2’ (NFER, Citation2018).

3. ‘To aid life … that is the basic task of the educator’. Montessori (Citation2012, 86).

References

- Aldea, E. 2014. Nomads and Migrants: Deleuze, Braidotti and the European Union in 2014. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/nomads-and-migrants-deleuze-braidotti-and-european-union-in-2014/.

- Aljabreen, H. 2020. “Montessori, Waldorf, and Reggio Emilia: A Comparative Analysis of Alternative Models of Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood 52:337–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00277-1.

- Archer, N. 2020. Borderland Narratives: Agency and Activism of Early Childhood Educators. PhD dissertation, University of Sheffield.

- Archer, N. 2022a. “‘I Have This Subversive Curriculum underneath’: Narratives of Micro Resistance in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 20 (3): 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X21105990.

- Archer, N. 2022b. “Uncovering the Discursive ‘Borders’ of Professional Identities in English Early Childhood Workforce Reform Policy.” Policy Futures in Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103221138013.

- Archer, N. 2022c. The Work of Montessori Nurseries in Underserved Areas of England. https://www.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/-/media/files/research/montessori/montessori-nurseries-report.pdf.

- Archer, N., and J. Albin-Clark. 2022. “Telling Stories That Need Telling: A Dialogue on Resistance in Early Childhood Education.” The Forum 64 (2): 21–29. https://doi.org/10.3898/forum.2022.64.2.02.

- Association Montessori Internationale. n.d. Montessori Programmes. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://montessori-ami.org/about-montessori/montessori-programmes.

- Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. 2009. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. http://www.deewr.gov.au/Earlychildhood/Policy_Agenda/Quality/Documents/Final%20EYLF%20Framework%20Report%20-%20WEB.pdf.

- Bachelard, G., and M. Jolas. 2014. The Poetics of Space. London: Penguin.

- Ballard, S., Z. Joyce, and L. Muller. 2012. “Editorial Essay: Networked Utopias and Speculative Futures.” 1.https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/380.

- BBC. 2016. Fit for a Prince? Montessori Schools Tackle ‘Middle-class’ Image. January 14 2016. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-35253290.

- Boyd, D. 2018. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability and the Legacies of Two Pioneering Giants.” Early Years 38 (2): 227–239.

- Brown, P. L. 2003. “Whose Sidewalk Is It, Anyway?” New York Times, January 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/01/05/weekinreview/ideas-trends-whose-sidewalk-is-it-anyway.html.

- Chickweed Arts. 2021. Building the Heart of a Child: Pirurvik Preschool. https://vimeo.com/545287524.

- Clough, P., and C. Nutbrown. 2014. Early Childhood Education: History, Philosophy and Experience. London: Sage.

- Crane, N. 1999. Two Degrees West: An English Journey. London: Penguin.

- Debs, M. C., J. de Brouwer, A. K. Murray, L. Lawrence, M. Tyne, and C. von der Wehl. 2022. “Global Diffusion of Montessori Schools: A Report from the 2022 Global Montessori Census.” Journal of Montessori Research 8 (2): 1–15.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press.

- Department for Education. 2022a. Early Years Career Progression Map. London: DfE. https://www.ncfe.org.uk/sector-specialisms/early-years-and-childcare/education-childcare-career-toolkit/.

- Department for Education. 2022b. Early Years Qualifications Achieved in the United Kingdom. London: DfE. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-qualifications-achieved-in-england.

- Department for Education. 2023a. Early Years Educator (Level 3): Qualifications Criteria. London: DfE. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-educator-level-3-qualifications-criteria.

- Department for Education. 2023b. Early Years Foundation Stage Profile 2023 Handbook. London: DfE. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1109972/Early_Years_Foundation_Stage_profile_2023_handbook.pdf.

- Eacott, S., and C. Wainer. 2023. “Schooling on the Margins: The Problems and Possibilities of Montessori Schools in Australia.” Cambridge Journal of Education: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2023.2189228.

- Early Childhood Action. 2012. Unhurried Pathways. Early Childhood Action. https://www.academia.edu/5714991/Unhurried_Pathways_a_new_framework_for_early_childhood.

- Early Years Coalition. 2021. Birth to Five Matters. London: Early Education. https://birthto5matters.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Birthto5Matters-download.pdf.

- Education Scotland. 2020. Realising the Ambition. Livingstone: Education Scotland.

- Firth, R. 2015. “Critical Cartography.” The Occupied Times of London 27:1–9. https://repository.uel.ac.uk/download/2bbbc23956a6a44fb873b1a17c9d17abc5cc4ad9f7901be9115083b654322dba/2935704/critical%20cartography%20final.pdf.

- Furman, A. 2012. “Desire Lines: Determining Pathways Through the City.” The Sustainable City VII: Urban Regeneration and Sustainability 155 (155): 23. https://doi.org/10.2495/SC120031.

- Georgeson, J., G. Roberts-Holmes, V. Campbell-Barr, N. Archer, S. Fung Lee, K. Gulliver, M. Street, G. Walsh, and J. Waters-Davies. 2022. Competing Discourses in Early Childhood Education and Care: Tensions, Impacts and Democratic Alternatives Across the UK’s Four Nations. London: British Educational Research Association. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/competing-discoursesin-early-childhood-education-and-care.

- Greene, M. 1995. Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, the Arts, and Social Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Harley, J. B. 1992. “Deconstructing the Map.” In Writing Worlds: Discourse, Text, and Metaphor in the Representation of Landscape, edited by T. J. Barnes and J. S. Duncan, 231–248. London, New York: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2021. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kay, L. 2018. School Readiness: A Culture of Compliance? EdD thesis, University of Sheffield. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/20433/.

- Kinchloe, J. L., and P. McLaren. 2000. “Rethinking Critical Theory and Qualitative Research.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 138–157. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Krygier, J., and D. Wood. 2009. “Critical cartography.” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, edited by R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 340–344. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Laliberte-Rudman, D. 2015. “Situating Occupation in Social Relations of Power: Occupational Possibilities, Ageism and the Retirement ‘Choice.” South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 45 (1): 27–33. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a5.

- Lawler, R. 2020. Lost Decade for Early Years Workforce. London: Early Years Alliance. https://www.eyalliance.org.uk/news/2020/01/“lost-decade”-early-years-workforce.

- Leafgren, S. 2018. “The Disobedient Professional: Applying a Nomadic Imagination Toward Radical Non-Compliance.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 19 (2): 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118779217.

- Macfarlane, R. 2012. The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot. London: Penguin.

- Machado, A. 2003. There Is No road: Companions for the Journey. California: University of California.

- Marshall, C. 2017. “Montessori Education: A Review of the Evidence Base.” Science of Learning 2 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0012-7.

- McFarlane, R. (@RobGMacfarlane). 2018. “[Twitter].” March 25, 2018. 7:00am. https://twitter.com/robgmacfarlane/status/977787226133278725?lang=en.

- Ministry of Education. 2013. “Nurturing early learners: A curriculum for kindergartens in Singapore. Educators’ guide: overview.” Singapore: Ministry of Education. https://www.moe.gov.sg/docs/default-source/document/education/preschool/files/nel/edu/guide/overview.pdf.

- Mohandas, S. 2023. “Transforming Practice: A Critical Interrogation of Montessori.” In Montessori Life: A Publication of the American Montessori Society, 41–49. Vol. 353 (2). New York: American Montessori Society.

- Montessori, M. 1917. The Advanced Montessori Method: Spontaneous activity in education, translated by Florence Simmonds. Vol. 1. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

- Montessori, M. 2012. The 1946 London Lectures. Vol. 17. Amsterdam: Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company.

- Murray, A. K., and C. Daoust. 2023. “Fidelity issues in Montessori research.” The Bloomsbury handbook of Montessori education, edited by A. Murray, E. M. T. Ahlquist, M. McKenna, and M. Debs, 199–208. London: Bloomsbury.

- NFER. 2018. The Reception Baseline Assessment. Slough: NFER.

- Nichols, L. 2014. “Social desire paths: an applied sociology of interests.” Social Currents 1 (2): 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329496514524926.

- Nutbrown, C. 2021. “Early childhood educators’ qualifications: a framework for change.” International journal of early years education 29 (3): 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1892601.

- Osgood, J. 2012. Narratives from the nursery: Negotiating professional identities in early childhood. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Osgood, J., D. Albon, K. Allen, and S. Hollingworth. 2013. “‘Hard to reach’ or Nomadic Resistance? Families ‘Choosing’ Not to Participate in Early Childhood Services.” Global Studies of Childhood 3 (3): 208–220. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2013.3.3.208.

- Osgood, J., A. Elwick, L. Robertson, M. Sakr, and D. Wilson. 2017. “Early Years Teacher and Early Years Educator: a scoping study of the impact, experiences and associated issues of recent early years qualifications and training in England.” Middlesex University/TACTYC. http://tactyc.org.uk/research.

- Osgood, J., and S. Mohandas. 2022. “Grappling with the Miseducation of Montessori: A Feminist Posthuman Rereading of ‘Child’ in Early Childhood Contexts.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 23 (3): 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/14639491221117222.

- Pascal, C., T. Bertram, and A. Cole-Albäck. 2020. Early Years Workforce Review: Revisiting the Nutbrown Review: Policy and Impact. London: Sutton Trust.

- Payler, J., and S. Bennett. 2020. “Workforce composition, qualifications and professional development in Montessori early childhood education and care settings in England.” Milton Keynes, UK: Montessori St. Nicholas Charity and The Open University. https://oro.open.ac.uk/72360/1/Open%20University%20Montessori%20final%20research%20report%2021%20Sept%202020.pdf.

- Rebughini, P. 2018. “Critical agency and the future of critique.” Current Sociology 66 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392117702427.

- Robertson, R. 1995. “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity Heterogeneity.” In Global Modernities, edited by M. Mike Featherstone, S. Lash, and R. Robertson, 25–44. London: Sage.

- Short, J. R. 2003. The world through maps: a history of cartography. Ontario: Firefly books.

- Sirem, Ö. 2022. “Montessori Education.” In Student-Friendly Teaching Approaches, edited by A. Ari, 13–33. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Snaza, N. 2013. “Bewildering education.” Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 10 (1): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2013.783889.

- Tally, R. T., Jr. 2010. “Nomadography: The ‘Early’ Deleuze and the History of Philosophy.” Journal of Philosophy: A Cross-Disciplinary Inquiry 5 (11): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/jphilnepal20105113.

- Wall, S., I. Litjens, and M. Miho Taguma. 2015. Pedagogy in early childhood education and care (ECEC): an international comparative study of approaches and policies Research brief. London: Department for Education. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445817/RB400_-_Early_years_pedagogy_and_policy_an_international_study.pdf.

- Wayfaring Britain. n.d. “Routes and Planning.” Accessed April 2, 2023. https://wayfaringbritain.com/routes.

- Whitescarver, K., and J. Cossentino. 2008. “Montessori and the Mainstream: A Century of Reform on the Margin.” Teachers College Record 110 (12): 2571–2600. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811001202.

Appendix 1

Career progression map