ABSTRACT

Despite concerns on their effectiveness and legitimacy, carbon markets are often presented as the main tool of climate policy. Developing countries are particularly eager to establish and interlink their carbon markets to benefit from global climate investment flows. Turkey is a belated but willing player in this endeavor. In tracing the ambivalent politics of establishing a carbon market in Turkey, we focus on the perceptions of different actors vis-à-vis carbon marketization attempts. Using policy documents, 22 expert interviews, and process tracing, we question the underlying assumptions on carbon markets in a country with unambitious climate targets. Our findings suggest that the making of carbon market in Turkey is not necessarily a rational, national interest-driven process but instead one promoted by the international organizations including World Bank and the EU. We conclude that this preference for market-based instruments defer public interest, favor more incremental policies, and ignore distributive justice concerns.

Introduction

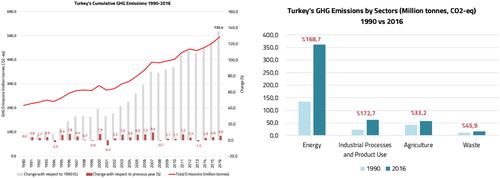

As the European Commission’s 2018 report underlines, Turkey has only ‘some level of preparation’ for harmonization with the European Union (EU) in the area of environment with ‘no progress made’ from the previous year on climate change.Footnote1 Three key requirements that are highlighted by this report are to a) complete alignment with the directives on key sectors (water, waste, industry), b) to ensure harmonization with cross-cutting legislation including EU acquis on informed public participation, and last but not least c) to complete the country’s alignment with the EU climate targets by ratifying Paris Agreement and implementing Turkey’s contribution to this end. ‘[F]ull alignment with the Emissions Trading Directive is needed,’ concludes the report in what otherwise reads like a pessimistic scorecard.Footnote2 We argue that these points call for an informed, extensive, and participatory public debate on climate change policies in Turkey after the entry into force of the Paris Agreement and in light of the EU's shifting climate leadership.Footnote3 While Turkey’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by 135.4 percent between 1990-2016 – thereby showing the highest rate of change among all OECD members – the country long delayed action by emphasizing its ‘special circumstances.'Footnote4 The twelve-year lag between 1992, when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was signed, and 2004, when Turkey ratified it, can be seen as a wasted opportunity for Turkish society to strengthen its institutional capacity as well as knowledge base on climate change. It was only with the ratification of the UNFCCC in 2004 and subsequent ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in 2009 that climate change started gaining policy attraction in Turkey. Today however, in an era when concerted, global climate action is more necessary than ever, Turkey's climate policy and prospects for ratification of the 2015 Paris AgreementFootnote5 still are in limbo as the country’s GHG emissions are skyrocketing with no peak on the horizon (see ).

Figure 1. Turkey’s cumulative GHG emissions and their sectorial breakdown (1990-2016) (Data: TURKSTAT, Charts: the authors).

Mainstream economists often refer to climate change as ‘the greatest market failure’ in history.Footnote6 Following this logic at the risk of sidelining numerous policy tools to mitigate anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, market-based instruments seem to dominate the global debates today. Emissions trading schemesFootnote7 (ETS), as the prime tool of market-based solutions, are typically presented as one-stop-shop ‘cost-effective solutions’ to address the planetary crisis.Footnote8 Although ETS appear in different types and varying levels of coverage,Footnote9 the idea of emissions trading can simply be explained as a GHG mitigation policy choice whereby an authority puts a maximum limit (or cap) on the aggregate GHG emissions in or across defined territories and distributes the emissions rights so that emissions are tradable between market participants.Footnote10 Alternatively, market participants can voluntarily set self-targets in the bottom-up model, a model we will come back later. In the trading process, greenhouse gas mitigation actions are reduced to abstract units that are supposedly quantifiable, verifiable, and commensurate.Footnote11 This idea of fixing market failure via a market-based mechanism (trading abstract mitigation units) was further engrained in the global climate negotiations and favored over other policy options such as command-and-control.Footnote12 Article 17 of the now defunct Kyoto Protocol introduced the first comprehensive global ETS, the Clean Development Mechanism.Footnote13 With the kick-off of this trading scheme, global climate governance entered a new era where climate change politics are effectively constricted within an uneven debate in which predominantly market-based alternatives are discussed.Footnote14

This article sets out to critically examine the making of the carbon market in Turkey through an in-depth case study focusing on the role of international actors (the EU and the World Bank) and the perceptions of the key stakeholders who took part in the process. The findings suggest that Turkey's carbon market in the making is not necessarily driven by rational economic motives or climate policy priorities. Rather, this process is heavily influenced by the policy agenda of international actors, with policy learning happening at the upper echelons of climate policy-making rather than through a comprehensive multi-stakeholder discussion on its potentials and pitfalls. The next section provides a detailed overview of the background literature on emission trading from a critical perspective. It is followed by a discussion of our methods and data sources and then our empirical findings. We then turn to diverging voices on the prospect of a national carbon market. The penultimate section elaborates on the main findings of the study in relation to the risks and opportunities of establishing a national carbon market. The article concludes with new research directions for a critical study of carbon markets in Turkey.

For a fistful of credits: political ecology of carbon markets

Carbon trading is a politically contested, multi-actor, and multi-scalar economic policy to mitigate greenhouse gases that are causing climate change.Footnote15 Put simply, carbon is rendered into a fictitious commodity, and a commodity market with scarcity is purposefully created for this commodity to function.Footnote16 As the theory suggests, any healthy market mechanism requires uniform, quantifiable, and commensurate units of trade, whether material or financial. However, in order for carbon trading to succeed, one must also assume that the carbon goods and services to be cheaper in one end of the trade. Machaquiero reminds us that what is being traded here in fact ‘is not carbon per se but atmospheric space – theoretically empty – that can be filled up with polluting emissions.’Footnote17 After all, polluting rights are matters of sovereignty as much as the questions on who owns the atmospheric space and with which authority. Uniformity of the units of trade in carbon marketsFootnote18, then, ensures that emissions in one part of the world can be readily compensated by and substituted for reductions elsewhere. This is what Beuret calls ‘the mathematics of counting carbon,’ a process in which carbon emissions are first made ‘calculable,’ then made ‘legitimate,’ and eventually re-politicized (or post-politicized, in other words) as a matter of public concern that can only be dealt with through market mechanisms.Footnote19

Despite policymakers’ strong emphasis on the need for market mechanisms as the cornerstone of efficient climate policy in developing countries, scientific literature is more hesitant to agree that this is the case. This is precisely because ‘the least costly approach to emissions reductions,’ as Carton maintains, ‘follows the path of least resistance’ based on the ‘seemingly neutral category such as economic efficiency.’Footnote20 Therefore, a focus on carbon markets as the silver bullet for the climate crisis is often a misplaced hope built on the ignorance of ‘historically specific socio-ecological relations.’Footnote21 In response to such ignorance, Lane argues that the efficiency argument for carbon markets is simply wrong since the basis of such arguments is laid ‘behind the scene, above our heads and before action.’Footnote22 This has made carbon trading a bonanza for consultants, bureaucrats, businesses with corporate social responsibility agendas, and carbon market traders rather than establishing goal-driven socio-ecological improvement. National and increasingly subnational authorities have a key role in facilitating this relationship.

As a prime example of ‘nature as accumulation strategy'Footnote23, carbon markets are influenced by the state’s uneven role over allocation of allowances, patterns, and regulations across different actors.Footnote24 On the one hand, this means that while states actively commodify carbon for market transactions, on the other hand, they also consciously create ‘climate rent'Footnote25 that is only up for grabs by a privileged few. Elaborating on this point, Andreucci et al. argue that ‘the state plays a key facilitating and regulating role – not only does it establish, modify or enforce property rights regimes and relations, but [it also] acts as a de facto landlord or asset owner.’Footnote26 Eventually, situating carbon markets at the core of any climate policy risks substituting ‘more marginal for more transformative climate action’ and creating uneven socio-spatial organization since markets actively seek to substitute more profitable forms of polluting.Footnote27 Moreover, such interventions also involve the extension and domination of market values across all institutions and socio-ecological relations.Footnote28 In essence, carbon markets produce profits over an assumption of absence or non-occurrence. Therefore, the design of carbon markets essentially involves political visions shaped by the traceability and tradability of this absence.Footnote29 By forging new connections, identities, and responsibilities, this absence leads to emergent ‘carbon economies’ normalizing enclosures, uneven socio-spatial ordering and production of new political subjectivities on how the climate crisis ought to be solved.Footnote30 The insistence on carbon markets as silver bullets should rather be understood in terms of legitimizing and stabilizing particular regimes of accumulation instituted through ‘the ambivalent role of state in creating, distributing and enforcing carbon rights.’Footnote31

Callon suggests that carbon markets are particularly interesting (or even ‘civilizing’) since they are experiments on what networked markets could be, with EU ETS being a key example.Footnote32 European Union's cornerstone climate policy instrument, EU ETS was unveiled in 2005 coinciding with the entry into force of the Kyoto Protocol. Yet, its history precedes this date. Although being the proponent and strong supporter of imposing economy-wide carbon taxes in early days of international climate negotiations, the European Commission embraced the global leadership of carbon markets after a long period of policy diffusion shaped by tough lobbying efforts. From the late 1990s onwards, the EU was exposed to lobbying from ‘predominantly oil and gas producers’ and electricity utilities, which at first campaigned for a national emissions trading scheme in the UK.Footnote33 After U.S. declined to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, the EU embraced this neoliberal, U.S.-style environmental permit trading system, whose acceptance was a result of ‘bureaucratic politics and policy entrepreneurship within the European Commission under domestic and international incentives.’Footnote34 Bailey identifies three main factors driving this ultra-quick political pregnancy: i) ongoing advanced debates on market mechanisms, ii) the European Commission's entrepreneurship and focus on trading as an economic opportunity, and iii) the idea to assume global leadership on carbon markets.Footnote35

Diffusion of carbon markets, like those spearheaded by the EU, are not neutral, apolitical processes. Thanks to the critical literature that consolidated over the past decade, we now have a better understanding of who benefits from carbon trading schemesFootnote36 and who loses in return.Footnote37 Fungibility of carbon, as Machaquiero suggests,Footnote38 produces a certain set of social relations between traders, project developers, business, states, and other stakeholders. This fungibility enables these stakeholders to hold the assumption that ‘atmospheric emptiness’ can be exchanged in terms of tons of CO2-equivalent.Footnote39 This emptiness gains more meaning when considering the uneven distributional impacts of carbon markets and their role in outsourcing pollution across borders without any net positive impact in addressing climate change. Thus, carbon markets, even those with stringent standards like EU ETS, help to deflect the climate crisis spatially, materially and politically.Footnote40

Oscar Reyes refers to carbon markets as ‘zombies’ due to their perpetual resuscitation subsequent to market collapses and failures.Footnote41 Advancing this zombie analogy, Lane and Stephan suggest that carbon markets in fact reveal the face of zombie neoliberalism, which is ‘empirically defunct yet still [politically] dangerously powerful.’Footnote42 Machaquiero reminds us how this tautology became the norm: ‘[C]arbon markets exist, and if they exist, it is because they work; because they work, they must continue to exist.’Footnote43 Another problem with carbon markets is their focus on the cheapest option as this curtails long-term structural measures that are crucial for a transformation in the economy towards deep decarbonization.Footnote44 The assumption is that under a well-functioning cap, high costs associated with emitting greenhouse gases will serve as an incentive for businesses to seek low- or zero-carbon modes of production.Footnote45 However, more often than not the politically negotiated, weak (or even non-existent) cap itself is a result of contestation and bargaining among those who seek economic efficiency. On this, Ervine warns against ‘concluding that if only the price was higher, emissions trading would solve our climate woes.’Footnote46

Being a politically negotiated carbon market ridden with multiple risks (such as abundant allowance surpluses due to economic recession, price volatility, sub-prime carbon risks, and even fraud susceptibility),Footnote47 the EU ETS by and large failed to meet its high promises on creating investment for decarbonization of power generation and only tangentially contributed to EU's climate policy targets.Footnote48 But then, why are developing countries like Turkey eager to embrace a failed policy instrument ridden with such risks? This is the central question we delve into in the following sections.

Research design

This study focuses on the making of the carbon market in Turkey by drawing on an in-depth analysis of the policy documents, secondary literature, and semi-structured interviews conducted with 22 key experts from public, private, academic, and civil society institutions (details of which are given in ) to triangulate the data. The interviews lasted between 36 minutes to 77 minutes and were conducted individually.Footnote49 Although attempts were made to contact state officials from diverse institutions, only one respondent in a key state institution participated in the interviews. However, given the respondent’s pivotal position vis-à-vis Turkish climate policy, we believe that the responses provided by this person are broadly representative of the national climate policy trajectory.

Table 1. Institutional distribution of respondents (n = 22).

By also drawing on process tracing understood as the exploration of a temporal sequence of events or phenomena, we engage with the political and social construction of carbon market in Turkey and attempt to describe its journey systematically. Following a political ecology-based critique of carbon markets, this study eventually aims to answer the following research questions:

What are the drivers, assumptions, arguments, and motivations regarding the preferential treatment of carbon markets as a climate policy in Turkey?

Which actors have been influential and/or more powerful relative to other actors in this policy preference? Whose ideas count and why?

Making the carbon market in Turkey: a brief history

Despite shortcomings, interlinked emission trading schemes continue to expand globally. Turkey is one of the pilot countries of this ongoing expansion. As an EU accession country with no access to the EU ETS and an Annex I country with no net GHG mitigation commitments, Turkey is a latecomer to the game.Footnote50 Although Turkey's official communications to the UNFCCC repeatedly argue being the country with ‘the lowest per capita primary energy consumption and the lowest per capita GHG emissions, among Annex I Parties,’Footnote51 the country's per capita emissions demonstrated an almost 1.5-fold increase, from 3.88 ton/capita to 6.3 ton/capita, between 1990-2016. Simultaneously, Turkey’s climate politics are increasingly drawn into market-based climate policies particularly in light of the new global climate agreement signed in Paris in 2015. As Ciplet and Roberts reiterate, Paris Agreement effectively reduced the international climate governance to ‘cheerleading for private and voluntary national action’ driven by libertarian ideals of justice, marketization, voluntarism and exclusive decision-making.Footnote52 Consequently, with additional pressure from international financing institutions and the private sector, Turkey accelerated its efforts to lay down legislative groundwork in pursuit of establishing an emission trading system that can be linked to international carbon markets.

While Turkey could not benefit from the market-based mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol due to its positioning within the developed country bloc, Annex I, Turkish companies has long championed voluntary carbon markets – the under-regulated ‘Wild West’ of carbon markets – with a total of 218 registered projects starting as early as 2005.Footnote53 The country ranked as high as the world's 6th largest carbon offset supplier in 2016.Footnote54 Unable to cater to the formal compliance markets under the UNFCCC, Turkish companies initially embarked on voluntary carbon market projects across a number of sectors (see ). In doing so, these companies mainly focused on a limited number of mitigation options in the absence of a national cap on GHG emissions. Adoption of the monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) regulation through a ministerial communiqué (see for a timeline of key legislation) eventually signaled that the country is preparing to put emissions trading at the very heart of its climate policies. This move – promoted by both the EU and the World Bank and complemented by the efforts of bilateral aid agencies from Europe like German GIZ – helped realize Turkey's intention to link up with the existing carbon markets. This was, in essence, the result of a World Bank-driven policy learning and diffusion process that Turkey embarked on in 2013, titled Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR).Footnote55 Similarly, as a concrete output of the bilateral cooperation with German GIZ,Footnote56 a Carbon Management Training Center specializing in carbon market trainings was established in 2016 together with the Turkey Environmental Protection Foundation (TUCEV), an offshoot of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. Despite the dwindling mutual interest in the country's accession to EU, Turkey still envisages the full transposition of the EU ETS Directive as of 2019 and is currently moving towards harmonization despite some setbacks. Therefore, Turkey continues to be subject to criticism by the European Commission due to limited progress in its (non-)alignment with the EU’s climate and energy policies.Footnote57

Table 2. Voluntary carbon projects in Turkey as of 2017.

Table 3. Regulations in place relevant to the establishment of Turkish national carbon market.

Turkey's determination to effectively monitor its GHG emissions first and then establish its own national emission trading system is striking. Proponents yield support to this vision by suggesting that the expansion of ETS-based climate policy instruments through linked markets would ease the potential economic impacts of undertaking emission reduction efforts.Footnote58 However, critics suggest that without concrete emission reduction targets, Turkey most likely risks its own interests and the effectiveness of its climate policies as well as positioning itself at a very disadvantageous position in international climate negotiations.Footnote59 Furthermore, there is no substantial evidence for the claim that stringent regulation and fair distributions of emissions allowances will be at the heart of Turkey's ETS in the making.Footnote60

Estimates suggest that Turkey has 1,071 million tons CO2-equivalent emissions reduction potential in renewable energy, waste management, and energy efficiency areas between 2013-2020, which would provide up to 33.4 million USD in revenue from trading activities within voluntary carbon markets.Footnote61 In 2015, Turkey catered for approximately 50 percent of all voluntary transactions in Europe, amounting to 3.1 million tons of CO2 equivalent.Footnote62 Although the country attracted the lion's share of Europe's voluntary transactions, it only produced revenues around 2 million USD due to the very low prices (1.1 USD/ton) of its carbon credits, which stalled at 1.9 million tons of CO2 equivalent.Footnote63 According to Sever and Bağdadioğlu,Footnote64 this experience suggests that the ‘need for a strictly regulated official carbon market does not seem vital at this stage in Turkey.’ Nevertheless, Turkey still emerged as the largest single source of voluntary carbon credits in Europe with transactions totaling 35 million tons of CO2 equivalent between 2007-2015.Footnote65

With a growing GHG emissions baseline and a ‘critically insufficient’Footnote66 climate policy, Turkey is one of the 14 countries developing national emission trading systems. The country became a participant in the World Bank’s PMR project as of 2011 and presented its first Market Readiness Proposal in 2013.Footnote67 Turkey’s intention here was announced as evaluating its various mitigation options through mapping relevant policy landscape; developing technical, institutional, and regulatory capacity; planning an appropriate national market-based instrument; and enhancing organizational engagement. Consequently, Turkey received international funding (3 million USD) for the first phase (2014–2017) to achieve legislative enforcement, including a pilot phase for measuring, reporting and verification (MRV) of emission reductions in cement, refinery, and electricity sectors.Footnote68 With the first phase of PMR project about to end now, features of the future Turkish carbon market are becoming clearer (see ).

Table 4. Features of the emerging Turkish carbon market.

The grass is (not) always greener on the other side: diverging voices

While the establishment of a national carbon market appears as the only tangible climate policy of Turkey in decades, not everyone agrees. There are fragmented drivers, motivations, and assumptions behind Turkey's intention about setting up a national ETS, as confirmed by some of our interviewees who took part in the process. Since carbon markets provide an effective way to remove climate policy from the sphere of the political and legitimize this depoliticization with the requirements of the international policy agendaFootnote69, they also serve to keep the basic social structures of carbon-intensive development intact. For instance, one of our respondents suggested UNFCCC process being the single most important driver and argued that alleged competitiveness and efficiency of the carbon markets provide the typical argument for the proponents of ETS in Turkey (Academic, August 2015). Therefore, establishment of the Turkish ETS appears to be the main policy avenue through which Turkey would catch up with the rest of the world on the Paris Agreement. A less articulated matter, however, is the critical role of international financing and development institutions in supporting carbon marketization in Turkey. In essence, as another respondent noted, ‘Turkey pays attention to this topic mainly to strengthen its bargaining power in the UNFCCC rather than aiming for any immediate economic gain’ (Business representative, August 2015). Following this line of thinking, international organizations seem to be riding on this wave and thereby facilitating Turkey’s integration with carbon markets even though the feasibility, effectiveness and desirability of this move is questionable.

Let us consider World Bank first. The forementioned PMR project can be understood as the preparatory stage for the eventual establishment of a national ETS in Turkey. Promoting market readiness is the driving motive for the World Bank to tap into new carbon markets in developing countries with none-to-little self-identified mitigation commitments, like Turkey. However, even the PMR project's own reports indicate potential pitfalls for market-based instruments in the country such as the major uncertainty on cost effectiveness, stakeholder acceptance, and environmental outcomes due to the behaviors of potential market actors vis-à-vis the state.Footnote70 Despite acknowledgement of such risks, there still seems to be a major push by the international organizations. summarizes the crucial gatekeeper role played by these organizations towards the establishment of a national carbon market in Turkey.

Table 5. International organizations’ major interventions in developing the Turkish carbon market.

On top of the push by international organizations, many of our respondents also agreed that Turkey’s relatively relaxed experience with voluntary carbon markets are highly instrumental in attracting private sector buy-in towards a national ETS. When Turkish companies started the first carbon transactions back in 2005, state institutions were initially at best cautious, if not reactionary. But, once the dreams of economic gains were realized through the influx of funding for speculative projects such as small hydropowerFootnote71, the attitude of state institutions in charge of climate policy shifted rapidly. Reenacting their authority in instituting, distributing and regulating greenhouse gas mitigation, these institutions turned their face towards formally registering voluntary projects in the country. At first, a set of regulations regarding a clearinghouse mechanism to keep track of the voluntary carbon trade activity was issued. However, due to the voluntary nature of such transactions and the state’s reluctance to reinforce oversight, none of our respondents seemed to be convinced of the utility of the voluntary carbon project registry. In the past few years, with the increase in supply-side negative pressure on the price of carbon, the profit margins have decreased further for companies who try to sell their carbon offset credits. Such a landscape leaves little incentive for measuring, reporting and verifying whether the GHG reduction even happened in the first place.

Another topic raised by our respondents was the indifference of the private sector towards climate policy, with the exception of some large, well-established business conglomerates. The primary motivation for this indifference appears to be the presumably shallow prospects of immediate economic gains and disbelief in potential regulatory measures by the state. Our respondents also indicated that a Turkish ETS would not be very useful in the absence of a properly functioning MRV system and be vulnerable to fraud and/or windfall profits for some with targeted exceptions. This is not very surprising since Turkey itself consistently avoided undertaking any binding mitigation commitments since the beginning of the climate regime.Footnote72 Our respondents therefore underlined the prioritization of the industrial perspective concerning carbon trade as it is mainly seen as an additional financing opportunity rather than a climate policy tool. While the aforementioned PMR project’s outputs assumed a bottom-up approach (i.e. no national overall limit to emissions) to cap-setting given the Turkish government’s high expectations for short-term economic growth, the real results are likely to remain ‘highly uncertain.’Footnote73 Needless to say, Turkey’s economy with mounting debt and currency crises – part of which is stemming from debt-fuelled, imported fossil fuel-driven energy sector – today is not in the best position to meet those high expectations.Footnote74

Some of respondents from business and state institutions indicated that their knowledge on the functioning of emissions trading was relatively limited, and therefore, they perceived the PMR project as a capacity building opportunity. Notwithstanding the need for capacity building, many of these respondents also posed the same question: ‘Why don't we also discuss alternative policy options?’ Addressing this rhetorical question, some have even shown preferences towards regulatory policy interventions instead of market-based instruments. For instance, ‘If only we can have a correct baseline,’ suggested one of our respondents, ‘[…] then we can suggest that a particular policy option is a sound one. Today, energy and climate policies are shaped by existing economic priorities more than anything else’ (Business representative, August 2015).

When it comes to power relations between different actors, almost all the representatives from non-state actors (that is business, academia and NGOs combined) criticized state institutions because of their exclusive approach to climate policy-making. Experts from businesses argued that even though they are invited to some of the meetings, their suggestions are never taken into consideration. This is despite the fact that private sector is way closer to decision-making processes in comparison with NGOs or academia as clearly shown by the composition of the inter-ministerial Coordination Board on Climate Change and Air Management Control. However, the power dynamics inside the coordination board appear highly asymmetric, both within the government institutions and across umbrella groups representing business interests. For instance, the final say of the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources is perceived to be much stronger than that of the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization – both being institutions whose mandates became further vague with the country's new presidential rearrangement. Given the fact that Turkey's environmental policies were historically superseded by ambitious energy infrastructure policies implemented by state institutions with slightly clearer mandates and some degree of attention to ‘public interest’ (kamu yararı), the future seems even bleaker now.Footnote75

A number of NGO representatives among our respondents also raised further concerns about the accountability of a potential ETS in Turkey, an issue directly related with recognition and participation.Footnote76 These respondents suggested that NGO involvement in the MRV system would be critical for the effectiveness and fairness of the market transactions. They also argued that a lock-in to market-based instruments would still shut the doors to other ambitious mitigation policies particularly in the absence of an absolute emissions cap, which the Turkish government clearly rejects. For example, one of our respondent posed the following question: ‘How can the authorities be sure that the Turkish ETS will not be susceptible to corruption or fraudulent activity even when the EU ETS has been shaken by scandals and illegal activities?’ (NGO representative, August 2015). Indeed, carbon trade in Turkey is found ‘likely to be exposed to fraud, which was one of the major problems in the EU ETS,’ not least due to problems over double countingFootnote77 and taxation.Footnote78

In relation to this, our respondents referred to elusive Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) practices in Turkey as an analogy for future carbon transaction monitoring activities. There are numerous cases of malfeasance in EIA processes, as these are commissioned and paid by the investors themselves with the state acting as the interlocutor of its preferred investment. For instance, Can's recent research on the voluntary carbon transactions in Turkey provides evidence for structural tokenism for projects, even when they are externally certified.Footnote79 Thus, our respondents also underlined the uneven socio-spatial role that ETS might play and shared concerns that such a system may further entrench existing social, economic, and environmental injustices. Attesting to such concerns, Kuş et al. recently found that ‘it does not seem economically and technically feasible to apply for carbon certification’Footnote80 in the forestry sector, also in part due to potential distributional injustices such as landgrabs and enclosures these carbon offset projects may trigger.Footnote81

The final argument emerging from our interviews was the concern that Turkey may eventually become the European Union's carbon offset backyard.Footnote82 Since Turkey is the largest provider of carbon credits to Europe even within the framework of under-regulated voluntary markets, integration within the EU ETS can further lead to uneasy outcomes regarding socio-spatial impacts with emergent accumulation opportunities for big players and deleterious environmental impacts for locals.Footnote83 ‘You know the rest of the story,’ concluded one of our respondents, referring to the failed Clean Development Mechanism projects that contributed to an overall increase in global GHG emissions (NGO representative, August 2015). In a similar vein, a recent econometric studyFootnote84 estimates that Turkey will face economic welfare-decreasing impacts of joining the EU ETS in the likely case that EU raises its 20-20-20 targetFootnote85 and pledges a 30-percent reduction from the business-as-usual. However, in the unlikely case that Turkey raises its ambition and itself pledges a 20-percent reduction from business-as-usual, the rest of the EU ETS participants may even start selling carbon credits to Turkey to meet the latter’s targets through offsets.Footnote86 All in all, we argue that these findings reveal the generally held yet ungrounded belief in the efficacy of carbon pricing and demonstrate a substantial prejudice against transformative non-market regulatory action such as enforcement of ambitious economy-wide emissions caps and bold just transition initiatives.Footnote87

Discussion

Once presented as the ‘Turkish Delight’ from the Middle East,Footnote88 Turkey's potential for carbon markets is still raising eyebrows – although it lost its early appeal due to the existing contraction in global carbon markets. As of today, European emission allowance prices hardly make any sense even if you accept the market-logic, given the rapid deep decarbonization required to avoid further disturbance to the Earth's climate system. However, this fact only becomes grimmer when we consider that voluntary carbon allowances originating in Turkey were sold for 1.1 USD/ton on average in international markets in 2016.Footnote89 Equally striking is that the increasing volumes of global carbon trade are not even enough to sustain the market value of carbon for rapid decarbonization, thus refuting its own economic arguments.Footnote90 Despite this backdrop, Turkey's formal attempts to establish a national carbon market are crystallized in three strategy documents, none of which have yet materialized. While the National Climate Change Action Plan put forth a target ‘to conduct studies towards establishment of a carbon market in Turkey until 2015’ back in 2011 (Targets Y4.1 and Y4.2), the Istanbul International Finance Center Strategy and Action Plan also reiterated a commitment to establish a national carbon market between 2011-2015 (Action 33). In a similar fashion, the national Energy Efficiency Strategy Document from 2012 set a target ‘establishing carbon trading and carbon market infrastructure in Turkey over 18 months’ (SA-07), a long-overdue target.

Our findings here show that whereas the UNFCCC process appears to be the most important justification for the push for carbon markets; the experts working in this domain frequently question the basis of arguments for establishing a national ETS in Turkey. Most often, unwieldy state bureaucracies’ inefficiency and inability to deal with new challenges such as climate change are presented as cues to justify market-led approaches. However, as Adaman and Madra remind us, neoliberalism is not only a drive towards marketization, but rather it is the economization of our social relations with one another and with nature.Footnote91 In a time when Turkey's authoritarian neoliberalism is taking a bold turn not only to marginalize dissent including environmental movements in the name of progress but also to protect ‘the circuits of capital accumulation’ by cordoning off decision-making from ‘popular pressures, public input and non-partisan auditing mechanisms,’ carbon markets seem an even more toxic approach to climate policy.Footnote92 In short, the expansion of market logic to climate policy and the ‘constitutive role of state in co-producing and maintaining’Footnote93 carbon markets does not amount to a rollback of the state but rather a newly defined power for the state to control ‘its subjects through an interface of economic incentives,’ together with coercion where necessary.Footnote94 Yet, this comes with a caveat: ‘the marketable permits system […] requires a priori setting of a cap.’Footnote95 Needless to say, Turkey’s reluctance to set an absolute cap or set a peak year is an inherent contradiction with its ambitions to push for an effective carbon market. This is why, despite the big push from various sides, a national carbon market in Turkey has not yet materialized. Moreover, without undertaking a net emission reduction target, Turkey's ambitions to be one of the global carbon market players in compliance markets do not seem to have a realistic horizon. This observation reaffirms the initial point of our research: the Turkish state’s push for carbon markets as the key tenet of its climate policy is indicative of its lust for new circuits of accumulation and distribution of ‘climate rent’ among cronies.

Our findings also align with an understanding of the Turkish state and its international interlocutors not as homogeneous entities but rather as multiple forms of social relations between various political and economic interests seeking further power through state-sanctioned carbon markets. This is the epitome of neoliberal climate policy, in which the states play a central role as part of the global wave of neoliberalization of environmental policies.Footnote96 However, such an approach downplays concerns on fairness, erodes legitimacy of public policy to address climate change equitably, and reduces procedural justice to techno-managerial governance of socio-environmental issues. The push by international organizations in the form of grants and projects also risk creating path dependencies in the wrong direction for Turkey since ‘carbon markets are political constructs constituted by the constellation of social actors, which dominate them.’Footnote97 Given the current authoritarian neoliberal moment and the state of crony capitalism in the country, it would also be useful to keep in mind that the history of carbon markets is ridden with politically motivated exceptions and exemptions.Footnote98 Therefore, these mechanisms also run the risk of simply being new excuses for economic re-distribution to those who are already powerful. That carbon markets are highly prone to capture by influential market players, that they oversimplify the complexity of climate change, and that they promote private gains at the expense of public welfare are all serious arguments to this end.Footnote99 After all, focusing on ‘a bubble of compliance in a whirlpool of speculation’Footnote100 with the intermediacy of international organizations does not amount to a robust climate policy.

Besides these, there are also multiple problemsFootnote117 with the political fixation with carbon markets as the prime climate policy superseding all other alternatives. Carbon markets, SwyngedouwFootnote101 argues, are part and parcel of a post-political shift that narrows the alternative pathways of decarbonization. LeonardiFootnote102 calls this fixation the carbon trading dogma: the belief that market failure can only be viably solved by further marketization. Not only does such a fixation reduce climate policy to a matter of expert knowledge and market players’ moves, but also it hollows the politics of market value creation, which are all about reach, force, and priority of particular values.Footnote103 States and private companies extend the abstraction of carbon as a commodity within ETS so to be able to drift away from their central responsibility towards avoiding catastrophic climate change. Major actors such as the World Bank and the EU facilitate this shift by marketizing climate policy in the developing world ‘while disadvantaging policy alternatives outside the market paradigm.’Footnote104 A similar push can be seen in the words of an EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) official who recently ‘emphasized that the developments in the country bring up the need for establishment of an emissions trading scheme.’Footnote105 Yet, carbon markets only ‘form one among a plurality of sites where issues of techno-science, economics, politics and ethics are currently being entangled in new, contentious patterns.’Footnote106 This brings us back to our initial research question of ‘why are policymakers so reliant on carbon markets when empirical evidence suggests that they do not work?’Footnote107

We suggest a number of answers to this question. First, the technopolitics of carbon markets oscillating between the World Bank, the EU, and finance flow-hungry developing countries like Turkey can only be understood within the process of marketization rendered as a topic pervasively dependent on expert knowledge and top-down political practice. Turkey, with its technocratic developmentalist political legacy, is a perfect fit for such interventions.Footnote108 Second, carbon marketization can be better explored within the territorial logic of uneven development processes that require ‘backyards’ to dump their waste. The EU's push to include Turkey into EU ETS and Turkey's push to prioritize carbon markets in key sectors such as cement, steel, and electricity shall be considered in this light. Third, the territorial logic of carbon marketization intersecting with the ‘incorporeal networks of commodity and capital markets’Footnote109 is essential for neoliberal global climate governance. Thus, the push for linking existing carbon markets and midwifing the birth of new ones are presented as a silver bullet to solve the global climate conundrum although they are rather ‘castles in the air’ with the uncertainty of their life after the Paris Agreement.Footnote110

Favoring the establishment and linkage of carbon markets in countries like Turkey will neither lead to a strong global carbon price nor make these emerging markets less vulnerable to fraud. Moreover, we believe the stakes are much higher with the ‘fatal attractions of win-win solutions,’ or having one's cake (e.g. no absolute emissions reduction targets) and eating it too (e.g. making windfall profits through carbon trading).Footnote111 After all, carbon markets persistently fail across all four criteria (additionality, equality, complexity blinding, and enclosing commons) for a pluralist approach to valuation of nature, even if we disregard all the problems with the valuation of nature.Footnote112 Rather, as GreenFootnote113 suggests, the worst possible outcome of such moves could be the pretentious linkage of carbon markets while the net GHG emissions continue to go up without stringent caps and careful economic management. Turkey, with its laggard climate policy legacy and institutional capacity problems, is not immune to such shortcomings. Yet to conclude on a hopeful note, we suggest that there are alternatives: For example, alternative radical proposals such as instituting carbon forum model instead of a carbon market modelFootnote114 or moving away from taxing work to taxing resource use and environmental damage is but one way to go against the grain of mainstream climate policies and Turkey’s political-economic dynamics.Footnote115

Conclusion

This study critically engaged with the emergence of the Turkish ETS and examined this subject through the lens of political ecology. Based on interviews with key experts and analysis of policy documents and processes, our findings challenge the inevitability of establishing carbon markets in Turkey as the ultimate climate policy facilitated by international organizations. These findings sit comfortably with the argument that carbon markets, in essence, contribute to the production of new subjectivities in the form of ‘techno-economic citizenship’ and reinforce the process of carbon marketizationFootnote116 rather than being the single most rational policy choice. Further research is needed on emerging political subjectivities to reveal why regulatory non-market policies with careful distributional aspects are not publicly debated in countries like Turkey, although this option was considered in the World Bank-funded PMR reports. This may take the shape of in-depth case studies on specific carbon market transactions as well as a deeper look into the international political economy of carbon marketization. Additional critical assessment of alternative climate policy options, we argue, will improve both Turkey's political position in the UNFCCC and contribute to protect its unique socio-ecological systems from the ills of climate change.

Acknowledgements

We thank our respondents for their time, two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their insightful and engaging comments. We also thank Megan Gisclon for the copyediting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Note on contributors

Ethemcan Turhan is a postdoctoral researcher at KTH (Royal Institute of Technology) Environmental Humanities Lab, Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment in Stockholm, Sweden. Dr. Turhan received his B.Sc. from Middle East Technical University and master's and Ph.D. degrees from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Before moving to KTH, he worked as a Mercator-IPC fellow on climate change in Istanbul Policy Center, Sabancı University. His scholarly work appeared on Applied Energy, Sustainability Science, New Perspectives on Turkey, Energy Research and Social Science, WIREs Climate Change, Ecological Economics, Journal of Political Ecology and Global Environmental Change.

Arif Cem Gündoğan is an independent researcher based in Istanbul, Turkey. He is a senior consultant on climate change and low carbon development with experience in private sector and international organizations. Mr. Gündoğan received his M.A. in Environment and Development at the Department of Geography, King’s College London where he studied as a Jean Monnet Scholar. He also completed advanced certificate programmes on the economics and governance of climate change (London School of Economics and Political Science) and climate change, adaptation and development (University of East Anglia).

ORCID

Ethemcan Turhan http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5074-5017

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. European Commission, Turkey 2018 Report. Note that no progress report was published in 2017, so the previous year here refers to 2016.

2. The EU Emissions Trading Directive is ‘a cornerstone of the EU's policy to combat climate change and its key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively. It is the world's first major carbon market and remains the biggest one,’ as the European Commission’s website suggests.

3. Skjærseth, “The European Commission’s Shifting Climate Leadership.”

4. Turhan et al., “Beyond Special Circumstances.”

5. As of October 2018, Turkey is among the 16 countries which have not yet ratified Paris Agreement out of 197 parties to the UNFCCC. Paris Agreement entered into force on 4th November 2016.

6. Stern, The Economics of Climate Change.

7. This term is sometimes conflated with ‘carbon trading,’ ‘carbon markets’ or ‘cap-and-trade,’ despite nuances. For simplicity, we prefer to use them synonymously within the scope of this work.

8. Egenhofer, “The Making”; Tietenburg, Emissions Trading: Principles and Practice; and Meckling, Carbon coalitions.

9. Hepburn, “Carbon Trading,” and Narassimhan et al., “Carbon Pricing.”

10. Felli, “Environment, not Planning.”

11. Lohmann, “Climate as Investment.”

12. Castree, “Crisis, Continuity and Change,” and Jordan, Wurzel, and Zito, “Still the Century.”

13. UNFCCC Decision 11/CMP.1 – Modalities, rules and guidelines for emissions trading under Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol (KP).

14. Lohmann, Carbon Trading.

15. Lederer, “Carbon Trading.”

16. Lane and Newell, “The Political Economy.”

17. Machaqueiro, “The Semiotics of Carbon,” 85.

18. Certified emissions reductions (CER) or European emission allowances (EUA).

19. Beuret, “Counting Carbon,” 8.

20. Carton, “Dancing to the Rhythms,” 14–5.

21. Ibid.

22. Lane, “The Promiscuous History,” 584.

23. Smith, “Nature as Accumulation Strategy.”

24. Bryant, “Nature as Accumulation Strategy?”

25. Felli, “On Climate Rent.”

26. Andreucci et al., “Value Grabbing,” 32.

27. Bryant, “The Politics of Carbon Market Design,” and Bryant, “Nature as Accumulation Strategy?”

28. Dempsey and Suarez, “Arrested Development?”

29. Knox-Hayes, “The Spatial and Temporal Dynamics.”

30. Bridge, “Resource Geographies 1.”

31. Pearse, Pricing Carbon in Australia, 7. See also Johnstone and Newell, “Sustainability Transitions and the State.”

32. Callon, “Civilizing Markets,” our emphasis; see also Kuch, The Rise and Fall.

33. Meckling and Jenner, “Varieties of Market-based Policy.”

34. Ibid., 863; See also Skjærseth and Wettestad, EU emissions Trading.

35. Bailey, “The EU Emissions Trading Scheme.”

36. Lederer, “Carbon Trading.”

37. Mathur et al., “Experiences of Host Communities.”

38. Machaqueiro, “The Semiotics of Carbon.”

39. Ibid.

40. Pearse, Pricing Carbon in Australia.

41. Reyes, “Zombie Carbon.”

42. Lane and Stephan, “Zombie Markets,” 2.

43. Machaqueiro, “The Semiotics of Carbon,” 90.

44. Lohmann, “Capital and Climate Change.”

45. Carton, “Environmental Protection as Market Pathology?”

46. Ervine, “How Low Can It Go?” 17.

47. Vlachou and Pantelias, “The EU’s Emissions Trading System.”

48. IEA, World Energy Outlook 2014. See also Gilbertson, Carbon Pricing.

49. All interviews were conducted under the conditions of anonymity and with the approval of King’s College London Research Ethics Committee.

50. Annex 1 is the group of developed countries as per UNFCCC, from which Turkey so far unsuccessfully attempted to differentiate itself. See Turhan et al., “Beyond Special Circumstances,” and Turhan, “Climate Change Policy in Turkey.”

51. MOEU, Sixth National Communication of Turkey Under the UNFCCC, 60.

52. Ciplet and Roberts, “Climate Change,” 154.

53. Nachmany et al., “The GLOBE Climate Legislation Study.”

54. Ecosystem Marketplace, Unlocking Potential.

55. For further information, please see the project website: http://www.worldbank.org/projects/P126101/pmr-turkey?lang=en

56. German Corporation for International Cooperation GmbH.

57. European Commission, Turkey Progress Report 2014, 2015, 2016, 2018.

58. Telli, Voyvoda, and Yeldan, “Economics of Environmental Policy,” and Arı and Köksal, “Carbon Dioxide Emission.”

59. Erdoğdu, “Turkish Support,” and Yeldan, “The Economics of Climate Change.”

60. Toklu, “Overview.”

61. Arı, “Voluntary Emission Trading Potential.”

62. EBRD, “Carbon Markets”.

63. Ecosystem Marketplace, Unlocking Potential. Even considering the current 10-year high of approximately 21 €/ton in European compliance markets as of October 2018, this price is still nowhere near the conservative estimate of ‘at least 40-80 USD/ton by 2020’ which eventually needs to go up to 100USD/ton by 2030 to reach Paris Agreement targets, according to Stiglitz et al., Report of the High-Level Commission. Moreover, savvy energy companies are already shielding themselves from higher costs of carbon, see: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-energy-companies-analysis/savvy-european-utilities-shield-themselves-from-higher-carbon-costs-idUSKCN1LF1EZ

64. Sever and Bağdadioğlu, “International Arrangements,” 60.

65. Ecosystem Marketplace, “Raising Ambition.”

67. MOEU, “Market Readiness Proposal.”

68. PMR Turkey, “PMR Project Implementation Status Report.”

69. Methmann and Stephan, “Political Sellout!”

70. Ricardo Energy & Environment, Assessment of Market Based, 26, 53, 63, 64.

71. Eren, “Transformation.”

72. Turhan et al., “Beyond Special Circumstances.”

73. Ecofys, “Roadmap for the Consideration.”

74. Akçay, Neoliberal populism in Turkey, and Ersoy and Kandemir, “Turkey Faces Ticking Bomb.”

75. Adaman, Akbulut, and Arsel, Neoliberal Turkey, and Bridge, Özkaynak, and Turhan, “Energy Infrastructure.”

76. Schlosberg and Collins, “From Environmental to Climate Justice.”

77. Bumpus, “The Matter of Carbon.”

78. Sever and Bağdadioğlu, “International Arrangements,” 63–5.

79. Can, “Türkiye'de Uygulanan ve Gönüllü Karbon Piyasalarında.”

80. Kuş et al., “Carbon Certification,” 136.

81. See also McCarthy, “A Socioecological Fix.”

82. Backyard here refers to its usage as in ‘Not-in-my-backyard’ (NIMBY), an emblematic environmental outcry for unwanted land uses or polluting facilities near residential areas.

83. Bumpus and Liverman, “Accumulation by decarbonization.”

84. Olçum and Yeldan, “Economic Impact Assessment.”

85. EU’s 20-20-20 targets are 20 percent reduction on energy consumption, 20 percent reduction of GHG from 1990 baseline and 20 percent increase in energy efficiency by 2020.

86. Olçum and Yeldan, “Economic Impact Assessment.”

87. Heffron and McCauley, “What Is the ‘Just Transition’?”

88. Ecosystem Marketplace, Fortifying the Foundation, 37.

89. Ecosystem Marketplace, Unlocking Potential.

90. Bryant, “Nature as Accumulation Strategy?”

91. Adaman and Madra, “Understanding neoliberalism.”

92. Tansel, “Authoritarian Neoliberalism,” 199.

93. Ibid.

94. Adaman and Madra, “Understanding Neoliberalism.”

95. Ibid.

96. MacNeil and Paterson, “Neoliberal Climate Policy,” and Ciplet and Roberts, “Climate Change.”

97. Pearse and Böhm, “Ten Reasons,” and Ervine, “How Low Can It Go?”

98. Calel, “Carbon Markets.”

99. Spash, “The Brave New World,” and Paterson, “Political Economies of Climate Change.”

100. Berta, Gautherat, and Gün, “Transactions in the European Carbon Market.”

101. Swyngedouw, “Apocalypse Forever?”

102. Leonardi, “Carbon Trading Dogma.”

103. Bryant, “The Politics of Carbon Market Design.”

104. Ibid.

105. Anadolu Ajansı. Türkiye karbon fiyatlandırmasına hazırlanıyor (Turkey is preparing for carbon pricing), 31 March 2017, https://aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/turkiye-karbon-fiyatlandirmasina-hazirlaniyor/784761?amp=1

106. Blok, “Clash of the Eco-sciences,” 470.

107. Leonardi, “Carbon Trading Dogma,” 71.

108. Adaman, Akbulut, and Arsel., Neoliberal Turkey.

109. Bailey and Maresh, “Scales and Networks,” 456.

110. Jevnaker and Wettestad, “Linked Carbon Markets.”

111. Muradian et al., “Payments for Ecosystem Services.”

112. Kallis, Gómez-Baggethun, and Zografos, “To Value or not to Value?”

113. Green, “Don’t Link Carbon Markets.”

114. Felli, “Beyond the Critique.”

115. Kallis, “Radical Dematerialization.”

116. Blok, “Clash of the Eco-sciences.”

117. For example, regarding the concerns on environmental integrity of carbon markets, see Schneider and La Hoz Theuer, “Environmental integrity.”

Bibliography

- Adaman, F., B. Akbulut, and M. Arsel. Neoliberal Turkey and Its Discontents: Economic Policy and the Environment Under Erdoğan. London: IB Tauris, 2017.

- Adaman, F., and Y. M. Madra. “Understanding Neoliberalism as Economization: The Case of the Environment.” In Global Economic Crisis and the Politics of Diversity, edited by Yıldız Atasoy, 29–51. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Akçay, Ü. Neoliberal populism in Turkey and its crisis. No. 100/2018. Working Paper, Institute for International Political Economy Berlin, 2018.

- Andreucci, D., M. García-Lamarca, J. Wedekind, and E. Swyngedouw. “‘Value Grabbing’: A Political Ecology of Rent.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 28, no. 3 (2017): 28–47.

- Arı, İ. “Voluntary Emission Trading Potential of Turkey.” Energy Policy 62 (2013): 910–919.

- Arı, I., and M. Aydınalp Köksal. “Carbon Dioxide Emission From the Turkish Electricity Sector and its Mitigation Options.” Energy Policy 39, no. 10 (2011): 6120–6135.

- Bailey, I. “The EU Emissions Trading Scheme.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1, no. 1 (2010): 144–153.

- Bailey, I., and S. Maresh. “Scales and Networks of Neoliberal Climate Governance: the Regulatory and Territorial Logics of European Union Emissions Trading.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34, no. 4 (2009): 445–461.

- Berta, N., E. Gautherat, and Ö. Gün. “Transactions in the European Carbon Market: A Bubble of Compliance in a Whirlpool of Speculation.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 41, no. 2 (2017): 575–593.

- Beuret, N. “Counting Carbon: Calculative Activism and Slippery Infrastructure.” Antipode 49, no. 5 (2017): 1164–1185.

- Blok, A. “Clash of the Eco-sciences: Carbon Marketization, Environmental NGOs and Performativity as Politics.” Economy and Society 40, no. 3 (2011): 451–476.

- Bridge, G. “Resource Geographies 1: Making Carbon Economies, old and new.” Progress in Human Geography 35, no. 6 (2011): 820–834.

- Bridge, G., B. Özkaynak, and E. Turhan. “Energy Infrastructure and the Fate of the Nation: Introduction to Special Issue.” Energy Research & Social Science 41 (2018): 1–11.

- Bryant, G. “The Politics of Carbon Market Design: Rethinking the Techno-Politics and Post-Politics of Climate Change.” Antipode 48, no. 4 (2016): 877–898.

- Bryant, G. “Nature as Accumulation Strategy? Finance, Nature, and Value in Carbon Markets.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108, no. 3 (2018): 605–619.

- Bumpus, A. G. “The Matter of Carbon: Understanding the Materiality of tCO2e in Carbon Offsets.” Antipode 43, no. 3 (2011): 612–638.

- Bumpus, A. G., and D. M. Liverman. “Accumulation by Decarbonization and the Governance of Carbon Offsets.” Economic Geography 84, no. 2 (2008): 127–155.

- Calel, R. “Carbon Markets: a Historical Overview.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 4, no. 2 (2013): 107–119.

- Callon, M. “Civilizing Markets: Carbon Trading Between in Vitro and in Vivo Experiments.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 34, no. 3 (2009): 535–548.

- Can, F. “Türkiye'de Uygulanan ve Gönüllü Karbon Piyasalarında Faaliyette Bulunan Projelerin Paydaş Katılımı Açısından Değerlendirilmesi.” Ekonomi, Politika & Finans Araştırmaları Dergisi 3, no. 1 (2018): 1–17.

- Carton, W. “Environmental Protection as Market Pathology? Carbon Trading and the Dialectics of the ‘Double Movement.’” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, no. 6 (2014): 1002–1018.

- Carton, W. “Dancing to the Rhythms of the Fossil Fuel Landscape: Landscape Inertia and the Temporal Limits to Market-Based Climate Policy.” Antipode 49, no. 1 (2017): 43–61.

- Castree, N. “Crisis, Continuity and Change: Neoliberalism, the Left and the Future of Capitalism.” Antipode 41, no. 1 (2010): 185–213.

- Ciplet, D., and J. Timmons Roberts. “Climate Change and the Transition to Neoliberal Environmental Governance.” Global Environmental Change 46 (2017): 148–156.

- Dempsey, J., and D. C. Suarez. “Arrested Development? The Promises and Paradoxes of ‘Selling Nature to Save it.’” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106, no. 3 (2016): 653–671.

- EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development). “Carbon Markets”, n.d. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://turkishcarbonmarket.com/carbon-markets.

- Ecofys. Roadmap for the consideration of establishment and operation of a Greenhouse Gas Emissions Trading System in Turkey, 2016. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://pmrturkiye.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ETSFinalReport_EN.pdf.

- Ecosystem Marketplace. Raising Ambition State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2016, 2016. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_5242.pdf.

- Ecosystem Marketplace. Fortifying the Foundation: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2009, 2009. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_2343.pdf.

- Ecosystem Marketplace. Unlocking Potential State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2017, 2017. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://www.cbd.int/financial/2017docs/carbonmarket2017.pdf.

- Egenhofer, C. “The Making of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme: Status, Prospects and Implications for Business.” European Management Journal 25, no. 6 (2007): 453–463.

- Erdoğdu, E. “Turkish Support to Kyoto Protocol: A Reality or Just an Illusion.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 14, no. 3 (2010): 1111–1117.

- Eren, A. “Transformation of the Water-Energy Nexus in Turkey: Re-Imagining Hydroelectricity Infrastructure.” Energy Research and Social Science 41 (2018): 22–31.

- Ersoy, E., and A. Kandemir. “Turkey Faces Ticking Bomb with Energy Loans of $51 Billion.” Accessed July 30, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-11/turkey-faces-ticking-time-bomb-with-energy-loans-of-51-billion.

- Ervine, K. “How Low Can It Go? Analysing the Political Economy of Carbon Market Design and Low Carbon Prices.” New Political Economy (2017): 1–21. doi:10.1080/13563467.2018.1384454.

- European Commission. Turkey Progress Report 2014. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2014/20141008-turkey-progress-report_en.pdf.

- European Commission. Turkey 2015 Report. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2015/20151110_report_turkey.pdf.

- European Commission. Turkey 2016 Report. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_turkey.pdf.

- European Commission. Turkey 2018 Report. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20180417-turkey-report.pdf.

- Felli, R. “On Climate Rent.” Historical Materialism 22, no. 3-4 (2014): 251–280.

- Felli, R. “Environment, not Planning: the Neoliberal Depoliticisation of Environmental Policy by Means of Emissions Trading.” Environmental Politics 24, no. 5 (2015): 641–660.

- Felli, R. “Beyond the Critique of Carbon Markets: The Real Utopia of a Democratic Climate Protection Agency.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences (in press. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.031.

- Gilbertson, T. Carbon Pricing: A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance. Indigenous Environmental Network and Climate Justice Alliance. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://www.ienearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Carbon-Pricing-A-Critical-Perspective-for-Community-Resistance-Online-Version.pdf.

- Green, J. F. “Don't Link Carbon Markets.” Nature 543, no. 7646 (2017): 484.

- Heffron, R. J., and D. McCauley. “What is the ‘Just Transition’?” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 88 (2018): 74–77.

- Hepburn, C. “Carbon Trading: a Review of the Kyoto Mechanisms.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 32 (2007): 375–393.

- ICAP (International Carbon Action Partnership). Emissions Trading Worldwide ICAP Status Report, 2016. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://icapcarbonaction.com/images/StatusReport2016/ICAP_Status_Report_2016_Online.pdf.

- IEA (International Energy Agency). World Energy Outlook 2014. Paris: OECD, 2014.

- Jevnaker, T., and J. Wettestad. “Linked Carbon Markets: Silver Bullet, or Castle in the Air?” Climate Law 6, no. 1-2 (2016): 142–151.

- Johnstone, P., and P. Newell. “Sustainability Transitions and the State.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions (in press. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.006.

- Jordan, A., R. K. Wurzel, and A. R. Zito. “Still the Century of ‘New’ Environmental Policy Instruments? Exploring Patterns of Innovation and Continuity.” Environmental Politics 22, no. 1 (2013): 155–173.

- Kallis, G. “Radical Dematerialization and Degrowth.” Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, no. 2095 (2017): 20160383.

- Kallis, G., E. Gómez-Baggethun, and C. Zografos. “To Value or not to Value? That is not the Question.” Ecological Economics 94 (2013): 97–105.

- Knox-Hayes, J. “The Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Value in Financialization: Analysis of the Infrastructure of Carbon Markets.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 50 (2013): 117–128.

- Kuch, D. The Rise and Fall of Carbon Emissions Trading. Hampshire: Springer, 2015.

- Kuş, M., H. Ülgen, Y. Güneş, R. Kırış, A. Özel, and U. Zeydanlı. “Carbon Certification of Afforestation and Reforestation Areas in Turkey.” In Carbon Management, Technologies, and Trends in Mediterranean Ecosystems, edited by Sabit Erşahin, Selim Kapur, Erhan Akça, Ayten Namlı, and Hakkı Emrah Erdoğan, 131–137. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- Lane, R. “The Promiscuous History of Market Efficiency: The Development of Early Emissions Trading Systems.” Environmental Politics 21, no. 4 (2012): 583–603.

- Lane, R., and P. Newell. “The Political Economy of Carbon Markets.” In The Palgrave Handbook of the International Political Economy of Energy, edited by T. Van de Graaf, B. K. Sovacool, A. Ghosh, F. Kern, and M.T. Klare, 247–267. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Lane, R., and B. Stephan. “Zombie Markets or Zombie Analyses? Revivifying the Politics of Carbon Markets.” In The Politics of Carbon Markets, edited by Benjamin Stephan, and Richard Lane, 1–23. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Larry, L. Carbon trading: A critical conversation on climate change, privatisation and power, Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 2006. http://www.daghammarskjold.se/wp-content/uploads/2006/09/carbon_trading_web.pdf.

- Lederer, M. “Carbon Trading: Who Gets What, When, and How?” Global Environmental Politics 17, no. 3 (2017): 134–140.

- Leonardi, E. “Carbon Trading Dogma: Theoretical Assumptions and Practical Implications of Global Carbon Markets.” Ephemera 17, no. 1 (2017): 61–87.

- Lohmann, L. “Climate as Investment.” Development and Change 40, no. 6 (2009): 1063–1083.

- Lohmann, L. “Capital and Climate Change.” Development and Change 42, no. 2 (2011): 649–668.

- Machaqueiro, R. “The Semiotics of Carbon: Atmospheric Space, Fungibility, and the Production of Scarcity.” Economic Anthropology 4, no. 1 (2017): 82–93.

- MacNeil, R., and M. Paterson. “Neoliberal Climate Policy: From Market Fetishism to the Developmental State.” Environmental Politics 21, no. 2 (2012): 230–247.

- Mathur, V. N., S. Afionis, J. Paavola, A. J. Dougill, and L. C. Stringer. “Experiences of Host Communities with Carbon Market Projects: Towards Multi-Level Climate Justice.” Climate Policy 14, no. 1 (2014): 42–62.

- McCarthy, J. “A Socioecological fix to Capitalist Crisis and Climate Change? The Possibilities and Limits of Renewable Energy.” Environment and Planning A 47, no. 12 (2015): 2485–2502.

- Meckling, J. Carbon Coalitions: Business, Climate Politics, and the Rise of Emissions Trading. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

- Meckling, J., and S. Jenner. “Varieties of Market-Based Policy: Instrument Choice in Climate Policy.” Environmental Politics 25, no. 5 (2016): 853–874.

- Methmann, C., and B. Stephan. “Political Sellout! Carbon Markets Between Depoliticising and Repoliticising Climate Politics.” In The Politics of Carbon Markets, edited by Benjamin Stephan, and Richard Lane, 261–279. London: Routledge, 2015.

- MOEU (Ministry of Environment and Urbanization). Sixth National Communication of Turkey under the UNFCCC, 2016. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://unfccc.int/files/national_reports/non-annex_i_natcom/application/pdf/6_bildirim_eng_11_reducedfilesize.pdf.

- MOEU (Ministry of Environment and Urbanization). Market Readiness Proposal Under the Partnership for Market Readiness Programme, 2013. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://www.thepmr.org/system/files/documents/TUR-FINAL-MRP_2013-05-03%20Final.pdf.

- Muradian, R., M. Arsel, L. Pellegrini, F. Adaman, B. Aguilar, B. Agarwal, E. Corbera, et al. “Payments for Ecosystem Services and the Fatal Attraction of win-win Solutions.” Conservation Letters 6, no. 4 (2013): 274–279.

- Nachmany, M., S. Fankhauser, T. Townshend, M. Collins, T. Landesman, A. Matthews, C. Pavese, K. Rietig, P. Schleifer, and J. Setzer. The GLOBE Climate Legislation Study: A Review of Climate Change Legislation in 66 Countries. Fourth Edition. London: GLOBE International and the Grantham Research Institute, London School of Economics, 2014.

- Narassimhan, E., K. S. Gallagher, S. Koester, and J. R. Alejo. “Carbon Pricing in Practice: a Review of Existing Emissions Trading Systems.” Climate Policy 18, no. 8 (2018): 967–991.

- Olçum, G. A., and E. Yeldan. “Economic Impact Assessment of Turkey's Post-Kyoto Vision on Emission Trading.” Energy Policy 60 (2013): 764–774.

- Özdemir, E. “Türkiye'de gönüllü karbon piyasaları.” 2017. Accessed July 30, 2018. http://bizden.lifenerji.com/bizden-haberler/turkiyede-gonullu-karbon-piyasalari/.

- Paterson, M. “Political Economies of Climate Change.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9, no. 2 (2018): 1–16.

- Pearse, R. Pricing Carbon in Australia: Contestation, the State and Market Failure. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Pearse, R., and S. Böhm. “Ten Reasons why Carbon Markets Will not Bring About Radical Emissions Reduction.” Carbon Management 5, no. 4 (2014): 325–337.

- PMR (Partnership for Market Readiness) Turkey. PMR Project Implementation Status Report, 2017. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://www.thepmr.org/system/files/documents/Turkey_PMR%20ISR_2017_03032017.pdf.

- Reyes, O. “Zombie Carbon and Sectoral Market Mechanisms.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 22, no. 4 (2011): 117–135.

- Ricardo Energy & Environment. Assessment of Market Based Climate Change Policy Options for Turkey. 2017. http://pmrturkiye.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/PMR-Turkey_MBI-Final-Report.pdf.

- Schlosberg, D., and L. B. Collins. “From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5, no. 3 (2014): 359–374.

- Schneider, L., and S. La Hoz Theuer. “Environmental Integrity of International Carbon Market Mechanisms Under the Paris Agreement.” Climate Policy (2018): 1–15. doi:10.1080/14693062.2018.1521332.

- Sever, D., and N. Bağdadioğlu. “International Arrangements, the Kyoto Protocol and the Turkish Carbon Market.” In Energy and Finance: Sustainability in the Energy Industry, edited by André Dorsman, Özgür Arslan-Ayaydin, and Mehmet Baha Karan, 49–67. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- Skjærseth, J. B. “The European Commission’s Shifting Climate Leadership.” Global Environmental Politics 17, no. 3 (2017): 84–104.

- Skjærseth, J. B., and J. Wettestad. EU Emissions Trading: Initiation, Decision-Making and Implementation. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2008.

- Smith, N. “Nature as Accumulation Strategy.” Socialist Register 43 (2007): 16–36.

- Spash, C. L. “The Brave new World of Carbon Trading.” New Political Economy 15, no. 2 (2010): 169–195.

- Stern, N. H. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Stiglitz, J. E., N. Stern, M. Duan, O. Edenhofer, G. Giraud, G. Heal, E. la Rovere, et al. Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices. Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, 2017. https://www.carbonpricingleadership.org/s/CarbonPricing_FullReport.pdf.

- Swyngedouw, E. “Apocalypse Forever?” Theory, Culture & Society 27, no. 2-3 (2010): 213–232.

- Tansel, C. B. “Authoritarian Neoliberalism and Democratic Backsliding in Turkey: Beyond the Narratives of Progress.” South European Society and Politics 23, no. 2 (2018): 197–217.

- Telli, Ç., E. Voyvoda, and E. Yeldan. “Economics of Environmental Policy in Turkey: A General Equilibrium Investigation of the Economic Evaluation of Sectoral Emission Reduction Policies for Climate Change.” Journal of Policy Modeling 30, no. 2 (2008): 321–340.

- Tietenburg, T. H. Emissions Trading: Principles and Practice. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Toklu, E. “Overview of Potential and Utilization of Renewable Energy Sources in Turkey.” Renewable Energy 50 (2013): 456–463.

- Turhan, E. “Climate Change Policy in Turkey: Current Opportunities, Persistent Problems: Introduction.” New Perspectives on Turkey 56 (2017): 131–133.

- Turhan, E., S. C. Mazlum, Ü. Şahin, A. H. Şorman, and A. Cem Gündoğan. “Beyond Special Circumstances: Climate Change Policy in Turkey 1992–2015.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 7, no. 3 (2016): 448–460.

- Vlachou, A., and G. Pantelias. “The EU’s Emissions Trading System, Part 2: A Political Economy Critique.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 28, no. 3 (2017): 108–127.

- Yeldan, E. “The Economics of Climate Change Action in Turkey: A Commentary.” New Perspectives on Turkey 56 (2017): 139–145.