ABSTRACT

While previous research shows that environmental policy attitudes depend on trust in government, existing studies have either focused exclusively on trust in politicians and democratic institutions (political trust) or conflated such measures with trust in a wider range of impartial government institutions and actors. In this study, we distinguish between trust in partial institutions that enact laws and policies on the one hand, and trust in impartial institutions that exercise government authority and enforce policies on the other, and systematically analyse their respective influence on climate policy preferences. In addition to investigating the direct influences of trust, we also focus on how trust in government institutions moderates the relationship between climate change concern and climate policy attitudes cross-nationally. Using European Social Survey data from 2016, we demonstrate that individual-level trust in both partial and impartial government institutions constitutes an important determinant of climate policy attitudes. Moreover, while we find no evidence of direct effects of trust at the country level, we demonstrate that individuals who are concerned about climate change are more likely to hold positive attitudes towards climate policies in high-trust countries, particularly where trust in impartial institutions such as the legal system and the police is high.

Key policy insights

Individuals’ tendency to favour climate policies depends on their trust in both partial government institutions that enact policies (e.g. parliament, politicians) and impartial institutions that enforce these policies (e.g. legal system, police).

At the country level, trust in impartial institutions plays a particularly crucial role for the translation of individuals’ climate change concern into support for climate policies.

A climate policy platform with broad public support not only relies on a trustworthy political system that enacts sound climate policies, but also on well-functioning and trustworthy government institutions that ultimately enforce these policies.

Introduction

Intensifying problems posed by increasing greenhouse gas emissions and climate change will most likely never be solved in the absence of regulatory, incentive-based policies that impose sanctions on polluting activities and/or encourage sustainable modes of conduct (IPCC, Citation2018). Indeed, real world implementation often attests to the effectiveness of climate policies such as carbon taxes (Murray & Rivers, Citation2015; O’Gorman & Jotzo, Citation2014) or subsidies on renewable energy (Hughes & Podolefsky, Citation2015). However, environmental policies aimed at mitigating climate change, like any other policy, ultimately rely on public support (Tjernström & Tietenberg, Citation2008), and climate policies such as carbon taxes can often meet widespread public opposition (Harrison, Citation2010; Rhodes et al., Citation2017).

Previous research has linked public support for climate (and other environmental) policies to trust in government, showing that people are more likely to favour a wide range of environmental policies if they trust various government institutions and actors, and/or live in countries with high levels of trust (e.g. Fairbrother, Citation2016; Harring & Jagers, Citation2013; Konisky et al., Citation2008). Given that trust in politicians and the political system is low in many countries (Newton et al., Citation2018), lack of trust in government potentially constitutes a crucial obstacle for the enactment of much needed climate policies.

Most previous studies have, however, primarily focused on trust in partial government institutions and actors that enact laws and policies (such as parliament, politicians and political parties) or conflated it with trust in impartial government institutions and public officials that implement and enforce policies and laws (such as the legal system, the police and government bureaucracy). We argue that this is problematic for several reasons. First, a well-functioning democracy does not necessarily guarantee a legal system that is robust and devoid of corruption (Charron & Lapuente, Citation2010; Rothstein, Citation2011; Rothstein & Teorell, Citation2008). As a result, public trust in these institutions are not necessarily linked. Large surveys confirm this discrepancy, showing that while politicians are one of the least trusted groups in society, public trust in the police is often higher than in many other groups and institutions (Newton et al., Citation2018).

Second, there is evidence that impartial institutions are equally or possibly even more important compared to partial institutions in creating public legitimacy (Rothstein, Citation2009). Given that climate policy, like any public policy, relies on the perception that government is legitimate, it is therefore crucial to distinguish and study trust in both partial and impartial government institutions when attempting to assess the influence of trust in government on climate policy attitudes (cf. Harring, Citation2018). In other words, it is reasonable to assume that public support for climate policies depends not only on the extent to which people trust in their political representatives but also, and perhaps even more so, on whether they trust in the institutions that are assigned the tasks of enforcing and implementing government policies.

In addition to distinguishing between trust in partial and impartial government institutions, we also extend our analysis of climate policy attitudes by devoting particular attention to the indirect effects of trust. In doing so, we add to existing research on the influence of trust in government on various environmental policy attitudes that has primarily been preoccupied with direct effects. After all, since people who are not concerned about climate change have few reasons to support any policy aimed at mitigating climate change (see, e.g. Kyselá et al., Citation2019), trust in government should have particularly important consequences for the link between climate change concern and climate policy preferences. Previous research has shown that climate change concern is one of the most important individual-level predictors of climate policy preferences (Smith & Leiserowitz, Citation2014), yet we expect that the influence of climate change concern depends on the level of trust in government among individuals and the countries in which they live (cf. Fairbrother et al., Citation2019). In this study, we design research investigating not only the direct influence of trust in different government institutions but also the moderating influence of trust (at both the individual and country level) on the relationship between climate change concern and climate policy attitudes across countries.

In the following section, we begin by reviewing the most relevant literature with regard to the relationship between trust in government and public support for climate policies. We then provide an account of the data and methods, followed by a presentation of our results. Finally, we discuss the results in relation to previous research and present our main conclusions.

Literature review

Trust in government and support for environmental policies

Previous research on environmental and climate policy attitudes has studied a wide range of outcomes, such as the willingness to pay for environmental protection (e.g. Fairbrother, Citation2016; Harring & Jagers, Citation2013) as well as preferences specifically for energy-supply technologies and energy-demand reduction (for an overview, see Whitmarsh et al., Citation2011). Previous studies have shown that greenhouse gas emissions are generally lower in countries with higher levels of trust in government (Tjernström & Tietenberg, Citation2008), thus suggesting that effective climate policies rely on public trust. While some studies have shown that trust in government’s capacity to design effective climate policies can be important for public attitudes towards climate change and other environmental problems (e.g. Lorenzoni & Pidgeon, Citation2006), a larger literature has shown that trust in government (in a broader sense) is a key predictor of climate (and other environmental) policy attitudes.Footnote1

One group of studies shows that trust in politicians is consistently associated with more positive attitudes towards carbon taxes and other related policies (Hammar & Jagers, Citation2006; see also Jagers et al., Citation2010). A larger group of studies on environmental policy attitudes expand the conceptualization and measurement of trust in government beyond a mere focus on politicians to include a broader set of actors and institutions, such as people in government and government authorities more broadly (e.g. Fairbrother, Citation2016; Harring & Jagers, Citation2013; Kollmann & Reichl, Citation2015; Konisky et al., Citation2008). While these studies show that trust is associated with a greater willingness to support environmental (e.g. fossil fuel) taxes and support government intervention to protect the environment, they either use single items or conflate all trust indicators into a single composite measure. Even though conflating trust in different government institutions and actors indeed has its merits, for example when contrasting the impact of trust in government with other predictors, it limits the possibilities to make comparisons between the effects of trust in different forms of government institutions.

Empirical analyses show that, while most measures of trust in government tend to form one single higher order dimension, they also tend to cluster into trust towards two fundamentally different categories of government institutions, namely, partial and impartial government institutions (Zmerli & Newton, Citation2017). Partial government institutions refer to institutions that create laws and policies (such as parliament, politicians and political parties) whereas impartial government institutions refer to those that implement and enforce government policies (such as the legal system, government bureaucracy, and the police). According to Rothstein (Citation2009, p. 313), government legitimacy and political support ‘is created, maintained, and destroyed not by the input but by the output side of the political system’, that is, by impartial institutions that enforce policies. This is corroborated by empirical studies showing that even public satisfaction with democracy appears to rely more on the quality of impartial government institutions than the functioning of democracy itself (Dahlberg & Holmberg, Citation2014). One of the reasons is that people have very little direct contact with democratic institutions on the input side of the political system, and the interactions that they do have (e.g. when voting in national elections), result in few direct consequences for their lives (Rothstein, Citation2009). In contrast, people’s lives are more clearly affected at the output side, where policies are implemented and laws are enforced (see also Kumlin Citation2004). More importantly, while people expect partiality and partisan competition at the input side (e.g. in parliament and among politicians), they expect the output side (e.g. law enforcement and government bureaucracy) to be characterized by impartiality and fairness (Rothstein Citation2009; see also van der Meer, Citation2017). Indeed, previous research has shown that the perceived quality of impartial government institutions has independent effects on attitudes towards taxation and social policies and that more fundamental orientations and attitudes are more likely to translate into concrete policy preferences if the quality of government is high (e.g. Svallfors, Citation2013). Taken together, this all suggests that trust/distrust in impartial institutions should have particularly important consequences for public attitudes towards government policies.

Very few studies on environmental policy attitudes distinguish between trust in different government institutions. One exception is Harring (Citation2018), who uses non-representative data from Sweden (college students) to investigate the influence of trust in politicians, government and parliament (labeled ‘political trust’), and trust in Swedish authorities (labeled ‘institutional trust’), on support for different environmental policies. The author finds that, while trust in politicians and parliament matter for support for all policies studied, trust in government authorities only matter for ‘pull’ policies such as subsidies. This suggests that trust in partial institutions might be more important for environmental policy support. However, these relationships only apply to a very small segment of a single country (Swedish college students). Furthermore, it is not clear what respondents think of when asked about ‘Swedish authorities’. Whereas the generalisability and specific meaning of these results are somewhat unclear, they nevertheless demonstrate the merits of distinguishing trust in different government institutions.

A few studies use cross-national data to study the effects of political trust at both the individual and country level. For instance, Smith and Mayer (Citation2018) find positive effects of trust in government on people’s willingness to give part of their income and willingness to pay more taxes to mitigate climate change. The authors combine several trust items into a single measure, including trust in the national government and cabinet ministers, the parliament, political parties, presidency and monarchy, courts, and local government. The authors also test the interaction between their trust measure and climate change risk perceptions but fail to find conclusive evidence of such an effect on the willingness to pay. Similarly, Fairbrother (Citation2016) finds positive effects of a single item measuring political trust (public officials and politicians), both at the individual and country level, on individuals’ willingness to make sacrifices in order to protect the environment.

While few studies on attitudes towards environmental policy distinguish and focus explicitly on trust in impartial government institutions and actors that enforce laws and policies, some studies exist that focus on government performance. Most notably, one group of studies has focused on the quality of government (QoG), in terms of the impartiality, lack of corruption, and effectiveness of institutions that exercise government authority and enforce government policies, such as the legal system, police, and government bureaucracy (cf. Rothstein, Citation2011). For instance, in a study on the relationship between environmental policy preferences and corruption (which is a central aspect of QoG), Harring (Citation2014) shows that high levels of corruption in the public sector is associated with public perceptions that economic environmental policy instruments are less effective, suggesting that well-functioning institutions that implement and enforce policies are essential for environmental policy support. In another study using a broader measure of government quality, Harring (Citation2016) finds that public preferences are more positive towards coercive environmental policy instruments, and more averse with regard to reward-based instruments, in countries with lower quality government, suggesting that the trustworthiness of government institutions has different implications for public support depending on the environmental policy in question. Since the actual functioning of impartial government institutions most likely influences political support through people’s perceptions (van der Meer, Citation2017), it is reasonable to assume that trust in impartial institutions is a key predictor of climate policy attitudes.

Indirect (moderating) influence of trust in government

In contrast to most previous research, we also focus on the indirect effect of trust in terms of its moderating influence on the relationship between environmental concern and policy support.Footnote2 A number of studies have investigated whether environmental concern is more likely to translate into support for environmental policy in the presence of political trust but most of these studies have either failed to find such an interaction effect (Davidovic et al., Citation2019; Fairbrother, Citation2016) or produced inconclusive results (Smith & Mayer, Citation2018).

There may be several explanations for these findings. First, while these studies estimate direct effects of political trust at the country level on environmental policy preferences, they do not estimate cross-level interaction effects. Hence, they ignore the distinction between the individual-level disposition to trust government actors and institutions, and the contextual effect of living in a country where the level of trust in government is generally high. Second, most of these studies use survey items tapping relatively broad concepts on both the dependent and independent variable side, focusing on the willingness to pay higher taxes for environmental protection or on concern for the environment in general. These studies might have produced very different results if items were used that measure policy support and (environmental) concern in relation to specific environmental problems, such as climate change.

A recent study that appears to remedy these shortcomings finds that people who believe in anthropogenic and destructive climate change are more likely to favour increasing fossil fuel taxes in countries where the level of trust in partial government institutions is high (Fairbrother et al., Citation2019). However, since only trust in partial institutions is included in the analysis, the study cannot speak to the importance of trust in impartial government institutions or their relative importance. Meanwhile, recent studies demonstrate how environmental attitudes are more likely to translate into preferences about environmental policies (e.g. taxes and spending) in countries where the quality of impartial government institutions is high (Davidovic et al., Citation2019; Kulin & Johansson Sevä, Citation2019). To the extent that people’s trust perceptions reflect actual quality of government, this suggests that trust in impartial institutions constitutes an important yet previously neglected influence on the relationship between climate change concern and climate policy attitudes.

Methods

In this study we use data from the European Social Survey (ESS) collected in or around 2016, across 23 European countries. The countries included in the study are: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), Czech Republic (CH), Estonia (EE), Finland (FI), France (FR), Germany (DE), Hungary (HU), Ireland (IE), Israel (IL), Iceland (IS), Italy (IT), Lithuania (LT), Netherlands (NL), Norway (NO), Poland (PL), Portugal (PT), Russian Federation (RU), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE), Switzerland (CH), Slovenia (SI), and United Kingdom (UK). The data for each country consists of a representative sample of the adult population (ESS Round 8, Citation2016).

Dependent variables

To measure the underlying tendency of individuals to be favourable towards climate policies as well as to measure attitudes towards specific policies aimed at mitigating climate change, we used all of the available items in the ESS measuring climate policy preferences (European Social Survey, Citation2016). While only three items are available in the ESS, they tap several crucial climate policy domains such as renewable energy and fossil fuels, thus covering both the supply- and demand-side, as well as the push/pull characteristics, of climate policies. The three items initially asked respondents ‘To what extent are you in favour or against the following policies in [country] to reduce climate change?’. The first item concerns taxes, asking respondents about their support for ‘Increasing taxes on fossil fuels, such as oil, gas and coal’. The second item concerns subsidies, asking respondents about their support for ‘Using public money to subsidise renewable energy such as wind and solar power’. Finally, the third item concerns bans, asking respondents about their support for ‘A law banning the sale of the least energy efficient household appliances’. Item responses for all three items were recoded so that higher values indicate stronger support, where 1 = ’Strongly against’, 2 = ‘Somewhat against’, 3 = ‘Neither in favour nor against’, 4 = ‘Somewhat in favour’, and 5 = ‘Strongly in favour’.

To measure overall favourability towards climate policies, we used principal component analysis (PCA) to extract an underlying ‘favourable to climate policy’ dimension. The PCA shows that all items load on a single component/factor (eigenvalue > 1) with factor loadings between 0.6 and 0.9. The shared variance amounts to approximately 50%, meaning that roughly half of the variation in the items is explained by this underlying dimension. In addition to studying the relationship between trust and individuals’ overall tendency to favour climate policies, we also study the relationship between trust and attitudes towards each of the three policies separately.

Independent variables: trust in government

To measure trust in partial and impartial institutions, we used a set of items from the core questionnaire of the ESS. The items ask respondents to what extent they ‘personally trust each of the institutions’: ‘ … [country]'s parliament’, ‘ … politicians’, ‘ … political parties’ (partial), ‘ … the legal system’, ‘ … the police’ (impartial). To test the overall reliability of the distinction between trust in partial and impartial government institutions, as well as testing for measurement equivalence across countries, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Overall, the standardized factor loadings were large (>0.8) and the model fit indices were acceptable (e.g. CFI = 0.993 and RMSEA = 0.059), suggesting that it is reasonable to measure trust in these two types of government institutions separately and that the measurements are comparable across countries (see Chen, Citation2007).Footnote3 However, since cross-national multilevel structural equation models with fewer than 40 countries is generally advised against (e.g. Meuleman and Billiet Citation2009), we obtained factor scores from PCA and used these scores in a series of multilevel regression models. The PCA analyses demonstrated that, for each factor, all items load on a single component/factor (eigenvalue > 1) with all factor loadings higher than 0.8 and explained variances between 81% and 85% (for impartial and partial, respectively). The correlation between the unrotated factors was only moderately high (r = 0.63), suggesting that while the two trust measures are related (since they both measure trust in government), they nevertheless appear to tap trust in different, i.e. partial and impartial, government institutions.

Independent variables: climate change concern and controls

To measure climate change concern, we used an item asking respondents ‘How worried are you about climate change?’. Item responses are 1 = ‘Not at all worried’, 2 = ‘Not very worried’, 3 = ‘Somewhat worried’, 4 = ‘Very worried’, 5 = ‘Extremely worried’. We also used a number of control variables. As a measure of political ideology, we used an item that asks respondents to place themselves on an 11-point political left–right scale, where 0 = ‘Left’ and 10 = ‘Right’. As a measure of generalized trust, we used an item asking respondents ‘Would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’ (0 = ‘You can’t be too careful’, 10 = ‘Most people can be trusted’). We also aggregated the trust scores into country means. At the country level, we also controlled for Eastern European countries using a dummy variable (1 = Eastern European, 0 = others).Footnote4 Finally, we also used the demographic control variables education (years), gender (1 = woman, 0 = man), and age (years). In Appendix Table A1, we report descriptive statistics (country means) for all key variables.

Methods and analyses

To analyse the data, we used multilevel analysis (MLA), i.e., a hierarchical linear models approach (Hox et al., Citation2017; Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012). In MLA, the statistical models take into consideration the nested structure of the data, in this case individuals nested in countries, while allowing for estimating effects of country-level factors such as national trust levels on individuals’ policy attitudes. In the analysis, we estimate the direct effects of trust at both the individual and country level, as well as the indirect effects of trust at the country-level in terms of its (cross-level) interaction with individuals’ climate change concern. In estimating the cross-level interaction effects, we followed best practice recommendations, for instance by including random slopes for all key individual-level variables (see, e.g. Aguinis et al., Citation2013; Bell et al., Citation2019). Given our substantive interest in the moderating influence of trust in government on the relationship between climate change concern and climate policy preferences across countries, where we assume that the strength of the effects of concern differ cross-nationally, this approach is particularly suitable since it allows for estimating the effects of concern on policy preferences both within and between countries.

We ran a series of MLA models for each dependent variable, starting with an empty model followed by models where variables were added in a stepwise procedure. In the results section, we only present one model for each dependent variable, which include our main variables of interest and key controls. We also ran a series of analyses estimating direct effects as well as cross-level interactions using additional controls at the country level, such as GDP (log), the level of individualism, Eastern European, and generalized trust. In the presented models, however, we only kept the country-level variables that were statistically significant in at least one of the models (direct effects of generalized trust and Eastern European). It should be noted that the inclusion of additional controls at the country level did not substantially alter our main results.Footnote4

Results

In , four models focusing on the direct effects of trust are presented where the general tendency to favour climate policies (factor), as well as preferences regarding three specific climate policies (taxes, subsidies, and bans), were regressed on the trust in government measures at both the individual and country level. The presented models also include the individual-level variables climate change concern, generalized trust, political ideology as well as country-level variables for generalized trust and Eastern European countries (dummy). The models also control for the demographic variables of sex, age, and education.Footnote5 The results show that the direct individual-level effects of trust in both partial and impartial government institutions are both statistically significant for the underlying climate policy preference factor, as well as each measure of specific climate policy preferences, except for the effect of trust in partial government institutions on attitudes towards subsidies on renewable energy. Hence, in line with previous research on environmental policy attitudes, our results show that individuals who are more trusting in government are generally more supportive of environmental policies.

Table 1. Multilevel regression analysis: Climate policy preferences, direct effects.

With regard to the strength of the effects on the overall favourability of climate policies, we found that trust in impartial government institutions has only a marginally weaker effect compared to trust in partial institutions. This suggests the general tendency among people to favour climate policies not only depends on their trust in government institutions that enact policies but also (and almost as strongly) on their trust in institutions that enforce policies. Focusing on attitudes towards specific climate policies, the effect on attitudes towards fossil fuel taxes is considerably stronger with regard to trust in partial institutions compared to trust in impartial institutions. However, when shifting the focus to subsidies on renewable energy, only trust in impartial institutions has a statistically significant effect. The effects on bans are both comparably small in size, yet trust in partial institutions appears somewhat more important than trust in impartial institutions. At the country level, none of the trust in government variables have a statistically significant direct effect on any of the climate policy attitude measures. We only found a statistically significant effect of generalized trust at the country-level with regard to fossil fuel tax preferences, suggesting that people are more likely to support increasing fossil fuel taxes if they live in countries where people are generally more trusting towards other people.

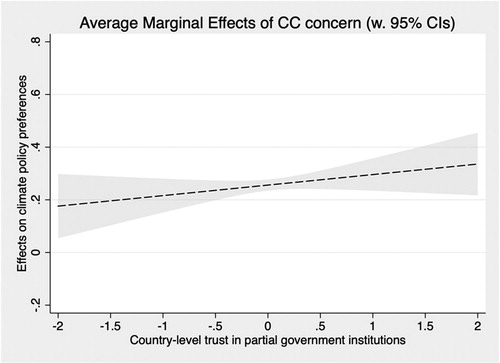

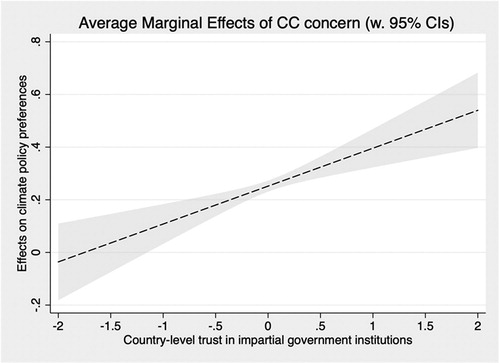

In the second set of multilevel models, we investigated the indirect effects of trust in government by analyzing the moderating influence of the trust measures (at both the individual and country level) on the individual-level relationship between climate change concern and climate policy attitudes. In , we included interaction terms based on the interaction between each of the two trust measures and the climate change concern item. While none of the individual-level interaction effects were statistically significant, the results show that the interaction effects for climate change concern and country-level trust in government institutions are statistically significant for several policy attitude measures, in particular those involving trust in impartial institutions. With regard to the relationship between climate change concern and the general tendency to favour climate policies, we only find a moderating influence of trust in impartial government institutions, as the cross-level interaction effect involving trust in partial institutions is not statistically significant. This means that people who worry about climate change are more likely to support climate policies in countries with higher levels of trust in impartial government institutions, such as the legal system and the police.

Table 2. Multilevel regression analysis: Climate policy preferences, interaction effects.

Similarly, the translation of climate change concern into favourable attitudes towards specific climate policies appears to depend almost exclusively on trust in impartial government institutions. Only with regard to favouring increasing fossil fuel taxes, we find effects of trust in both partial and impartial government institutions, yet still a comparably stronger moderating influence of trust in impartial institutions. Our results therefore add to previous research that has found a similar moderating influence of trust in partial institutions (cf. Fairbrother et al., Citation2019), since they suggest that trust in impartial institutions is an even more important moderator of the relationship between climate change views and attitudes towards fossil fuel taxes. Regarding subsidies and bans, only trust in impartial institutions appears to explain the extent to which climate change concern is translated into support for these policies. In contrast to the models with only direct effects, we also find a negative effect of generalized trust at the country level and Eastern European countries on favouring bans on inefficient household appliances.Footnote6

In and , the cross-level interaction effects are illustrated in two graphs, displaying the marginal effects of climate change concern on the general tendency to favour climate policies at different levels of trust in government. The figures clearly show that trust in impartial institutions () is comparably more influential (steeper slope) than trust in partial institutions () in strengthening the link between climate change concern and individuals’ overall support for climate policies. As expected, while the individual-level effect of climate change concern on the general tendency to favour climate policies is virtually non-existent at low levels of trust in impartial government institutions, it is statistically significant and substantial (based on the confidence intervals, approx. 0.4–0.7) at high levels of trust.

Discussion

From the outset, we expected that climate policy preferences should depend not only on trust in partial government institutions (such as parliament and politicians) but also in impartial institutions (such as the legal system and the police). We also expected trust in government, especially at the country level, to primarily operate indirectly through the strengthening or weakening of the individual-level relationship between climate change concern and climate policy attitudes.

In line with our expectations, we found that trust in both partial and impartial government institutions matters for climate policy attitudes. However, similar to Smith and Mayer (Citation2018), we only found direct effects of trust at the individual-level, thus contradicting the results from other studies finding direct effects of country-level trust in partial institutions on policy attitudes (e.g. Fairbrother, Citation2016; Fairbrother et al., Citation2019). Our results show that trust in both types of government institutions has unique effects on policy attitudes, and that individuals’ trust in impartial institutions (unlike trust in partial institutions) matters for attitudes towards all policies studied. For instance, our results suggest that people are more likely to favour subsidies if their trust in impartial institution is high, whereas we found no such direct effect of trust in partial institutions. Hence, our results not only demonstrate the importance of distinguishing between trust in partial and impartial institutions, but also that trust in impartial institutions, in contrast to previous studies using non-representative samples (Harring, Citation2018), appears to matter for attitudes towards a wide range of climate policies.

Although not the main aim of our study, we showed that trust in partial and impartial institutions has different effects on climate policy preferences depending on the policy in question, thereby corroborating similar results in previous studies using non-representative samples (e.g. Harring, Citation2018). However, the nature of these linkages remains elusive. The policy attitudes measures not only relate to different types of policy instruments with different steering functions (e.g. taxes and subsidies) but also to different policy domains at both the supply and demand side (e.g. fossil fuels and renewable energy). Future research should strive to more carefully measure policy instruments and policy domains separately, and assess their linkages to trust in different types of government institutions. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, no cross-national datasets include survey items that enable the separation of policy instruments (e.g. taxes or subsidies) from policy domains (e.g. fossil fuels or renewable energy), while also including measures of trust in partial and impartial government institutions.

Turning to the indirect effects of trust in government, we primarily expected to find a moderating effect of trust at the country level on the individual-level relationship between climate change concern and policy preferences. Indeed, in line with previous studies, we found no moderating influence of trust at the individual level (Davidovic et al., Citation2019; Fairbrother, Citation2016). We did identify cross-level interaction effects, where individuals’ climate change concern is more likely to translate into support for climate policies in countries with higher levels of trust in government. However, we found a comparably weaker cross-level interaction effect on attitudes towards increasing fossil fuel taxes involving country-level trust in partial government institutions. Instead, we found consistent cross-level interaction effects involving trust in impartial institutions across all climate policy attitude measures. This suggests that people who are concerned about climate change are more likely to hold favourable attitudes towards climate policies in countries where trust in government, most notably trust in impartial institutions, is generally high. This is consistent with the broader literature claiming that public legitimacy relies more heavily on institutions at the output-side of government (e.g. Rothstein, Citation2009; Dahlberg & Holmberg, Citation2014). Indeed, future studies on climate policy attitudes could benefit by systematically distinguishing and investigating the role of impartial government institutions.

Finally, it should also be noted that impartial government institutions span a broad array of institutions, including not only those studied here, but also potentially important implementing institutions such as the public bureaucracy and government agencies. Public perceptions about these types of institutions might also be of importance in generating public legitimacy for government policies (cf. Rothstein, Citation2011). Future studies on climate policy attitudes should therefore strive to also include measures of trust in a wider range of impartial government institutions and assess their relative importance for climate policy preferences.

Conclusion

Our findings constitute a crucial contribution to the existing literature since they show that trust in impartial institutions, separate and apart from trust in partial institutions, have important consequences for public climate policy preferences. Since levels of political trust (i.e. trust in partial institutions) are low in many countries, we argue that policies that depend more heavily on trust in partial institutions (e.g. fossil fuel taxes) can constitute an inextricable challenge to politicians and policymakers. Instead, subsidies (on renewable energy) appear to provide a more viable alternative, as we have shown that public acceptability and/or support for such policies primarily relies on trust in impartial (rather than partial) institutions, such as the legal system and the police. Since trust in these types of institutions is considerably higher compared to trust in politicians and other partial institutions, subsidies will most likely meet less public opposition and thus prove easier to implement.

Our results also reveal an influence of societal levels of trust in government that is primarily indirect in nature, as people who worry about climate change are substantially more likely to support climate policies if they live in a society where impartial institutions such as the legal system and the police (as opposed to the political system) is generally perceived as trustworthy. In countries where trust in impartial institutions is generally low, on the other hand, people who worry about climate change are not more likely to support climate policies than those who do not. This provides a perhaps counter-intuitive conclusion for policymakers; in order to facilitate greater support for environmental policies that address climate change, it appears as if people have to perceive that impartial government institutions, such as the legal system and the police, are trustworthy, or that they live in a country where many people think so. Hence, our results suggest that a successful climate policy platform with broad public support not only relies on government providing sound climate policies, but also on well-functioning and trustworthy government institutions that ultimately enforce these policies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (621.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This is in line with the broader literature on the influence of trust in government on public support for government policies in general, showing that if people distrust politicians, government officials, and the system of government more broadly, they will be less likely to support government policies across a wide range of domains (Chanley et al., Citation2000; Hetherington, Citation2005; Rudolph & Evans, Citation2005). According to Levi and Stoker (Citation2000, p. 491), ‘the more trustworthy citizens perceive government to be, the more likely they are to comply with or even consent to its demands and regulations’.

2 The idea that there are moderating factors that constrain the translation of environmental concerns into support for, or participation in, some type of pro-environmental action has a long history in the broader literature on individuals’ environmental attitudes and behaviours. Much of this literature identifies a conspicuous concern-behaviour gap, where people who display relatively high levels of environmental concern often fail to act on these concerns (see, e.g., Kollmuss & Agyeman, Citation2002). A growing number of studies have tied this gap to societal factors linked to the national context, such as the level of individualism, human development, economic prosperity, and generalized trust (Eom et al., Citation2016; Johansson Sevä & Kulin, Citation2018; Pisano & Lubell, Citation2017; Tam & Chan, Citation2018).

3 See Appendix Table A2 for a detailed overview of the CFA model fit statistics.

4 We include the Eastern European dummy variable to take into account the unique legacy in Eastern European countries, for instance the historic shift from authoritarian and centralised communist rule to democracy, market economy, and national sovereignty. Due to this legacy, scholars have argued that political trust operates quite differently in Eastern European countries (e.g. Rose & Mishler, Citation2011). Moreover, several studies have demonstrated distinct patterns in Eastern European countries with regard to public opinion on climate change (Chaisty & Whitefield, Citation2015; McCright et al., Citation2016; Smith & Mayer, Citation2018), suggesting that it is important to control for the unique Eastern European experience not least when studying the relationship between trust in government and climate policy attitudes. The results from all additional analyses can be obtained from the authors upon request.

5 A side from the latent measures of trust in partial and impartial government institutions and the climate policy support factor, all variables in the models are unstandardized.

6 To assess whether the cross-level interaction effects could be found in both Eastern and Western European countries, we also ran separate OLS regressions for each country and examined the effect sizes (see Appendix, Table A3). While the strength of the relationship between climate change concern and climate policy preferences is more closely linked to trust levels in Western European countries, we still found support (albeit weaker) for these relationships in Eastern European countries. However, due to the relatively small number of countries, it is difficult to draw any strong conclusions about East-West differences based on these results.

References

- Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Culpepper, S. A. (2013). Best-practice recommendations for estimating cross-level interaction effects using multilevel modeling. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1490–1528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313478188

- Bell, A., Fairbrother, M., & Jones, K. (2019). Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Quality & Quantity, 53(2), 1051–1074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0802-x

- Chaisty, P., & Whitefield, S. (2015). Attitudes towards the environment: Are post-Communist societies (still) different? Environmental Politics, 24(4), 598–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1023575

- Chanley, V. A., Rudolph, T. J., & Rahn, W. M. (2000). The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1086/317987

- Charron, N., & Lapuente, V. (2010). Does democracy produce quality of government? European Journal of Political Research, 49(4), 443–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01906.x

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

- Dahlberg, S., & Holmberg, S. (2014). Democracy and bureaucracy: How their quality matters for popular satisfaction. West European Politics, 37(3), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.830468

- Davidovic, D., Harring, N., & Jagers, S. C. (2019). The contingent effects of environmental concern and ideology: Institutional context and people’s willingness to pay environmental taxes. Environmental Politics, 29(4), 674–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1606882

- Eom, K., Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Ishii, K. (2016). Cultural variability in the link between environmental concern and support for environmental action. Psychological Science, 27(10), 1331–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616660078

- ESS Round 8: European Social Survey Round 8 Data. (2016). Data file edition 2.1. NSD – Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC.

- European Social Survey. (2016). ESS round 8 source questionnaire. ESS ERIC Headquarters c/o City University London.

- Fairbrother, M. (2016). Trust and public support for environmental protection in diverse national contexts. Sociological Science, 3, 359–382. https://doi.org/10.15195/v3.a17

- Fairbrother, M., Johansson Sevä, I., & Kulin, J. (2019). Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: Evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Global Environmental Change, 59, 102003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102003

- Hammar, H., & Jagers, S. C. (2006). Can trust in politicians explain individuals’ support for climate policy? The case of CO2 tax. Climate Policy, 5(6), 613–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2006.9685582

- Harring, N. (2014). Corruption, inequalities and the perceived effectiveness of economic pro-environmental policy instruments: A European cross-national study. Environmental Science & Policy, 39, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.08.011

- Harring, N. (2016). Reward or punish? Understanding preferences toward economic or regulatory instruments in a cross-national perspective. Political Studies, 64(3), 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12209

- Harring, N. (2018). Trust and state intervention: Results from a Swedish survey on environmental policy support. Environmental Science & Policy, 82, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.01.002

- Harring, N., & Jagers, S. (2013). Should we trust in values? Explaining public support for pro-environmental taxes. Sustainability, 5(1), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5010210

- Harrison, K. (2010). The comparative politics of carbon taxation. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 6(1), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.093008.131545

- Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton University Press.

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge.

- Hughes, J. E., & Podolefsky, M. (2015). Getting green with solar subsidies: Evidence from the California solar initiative. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 2(2), 235–275. https://doi.org/10.1086/681131

- IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Jagers, S. C., Löfgren, Å, & Stripple, J. (2010). Attitudes to personal carbon allowances: Political trust, fairness and ideology. Climate Policy, 10(4), 410–431. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2009.0673

- Johansson Sevä, I., & Kulin, J. (2018). A little more action, please: Increasing the understanding about citizens’ lack of commitment to protecting the environment in different national contexts. International Journal of Sociology, 48(4), 314–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2018.1515703

- Kollmann, A., & Reichl, J. (2015). How trust in governments influences the acceptance of environmental taxes. In F. Schneider, A. Kollmann, & J. Reichl (Eds.), Political economy and instruments of environmental politics (pp. 53–70). The MIT Press.

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401

- Konisky, D. M., Milyo, J., & Richardson, L. E. (2008). Environmental policy attitudes: Issues, geographical scale, and political trust. Social Science Quarterly, 89(5), 1066–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00574.x

- Kulin, J., & Johansson Sevä, I. (2019). The role of government in protecting the environment: Quality of government and the translation of normative views about government responsibility into spending preferences. International Journal of Sociology, 49(2), 110–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2019.1582964

- Kumlin, S. (2004). The personal and the political: How personal welfare state experiences affect political trust and ideology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kyselá, E., Ščasný, M., & Zvěřinová, I. (2019). Attitudes toward climate change mitigation policies: A review of measures and a construct of policy attitudes. Climate Policy, 19(7), 878–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1611534

- Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 475–507. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.475

- Lorenzoni, I., & Pidgeon, N. F. (2006). Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Climatic Change, 77, 73–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9072-z

- McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E., & Marquart-Pyatt, S. T. (2016). Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environmental Politics, 25(2), 338–358.

- Meuleman, B., & Billiet, J. (2009). A Monte Carlo sample size study: How many countries are needed for accurate multilevel SEM? Survey Research Methods, 3(1), 45–58. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-1041001

- Murray, B., & Rivers, N. (2015). British Columbia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax: A review of the latest “grand experiment” in environmental policy. Energy Policy, 86, 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.08.011

- Newton, K., Stolle, D., & Zmerli, S. (2018). Social and political trust. In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust (pp. 1–37). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/

- O’Gorman, M., & Jotzo, F. (2014). Impact of the carbon price on Australia’s electricity demand, supply and emissions (Working Paper No. 1411). Centre for Climate Economics & Policy, July 2014.

- Pisano, I., & Lubell, M. (2017). Environmental behavior in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of 30 countries. Environment and Behavior, 49(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515600494

- Rhodes, E., Axsen, J., & Jaccard, M. (2017). Exploring citizen support for different types of climate policy. Ecological Economics, 137, 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.027

- Rose, R., & Mishler, W. (2011). Political trust and distrust in post-authoritarian contexts. In S. Zmerli & M. Hooghe (Eds.), Political trust: why context matters (pp. 1–117). ECPR Press.

- Rothstein, B. (2009). Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338795

- Rothstein, B. (2011). The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. University of Chicago Press.

- Rothstein, B. O., & Teorell, J. A. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance, 21(2), 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x

- Rudolph, T. J., & Evans, J. (2005). Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00148.x

- Smith, N., & Leiserowitz, A. (2014). The role of emotion in global warming policy support and opposition. Risk Analysis, 34(5), 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12140

- Smith, E. K., & Mayer, A. (2018). A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Global Environmental Change, 49, 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.02.014

- Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (2012). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage.

- Svallfors, S. (2013). Government quality, egalitarianism, and attitudes to taxes and social spending: A European comparison. European Political Science Review, 5(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577391200015X

- Tam, K. P., & Chan, H. W. (2018). Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Global Environmental Change, 48, 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.12.001

- Tjernström, E., & Tietenberg, T. (2008). Do differences in attitudes explain differences in national climate change policies? Ecological Economics, 65(2), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.06.019

- van der Meer, T. (2017). Dissecting the causal chain from quality of government to political support. In C. van Ham, J. A. Thomassen, K. Aarts, & R. Andeweg (Eds.), Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis: Explaining trends and cross-national differences in established democracies (p. 136). Oxford University Press.

- Whitmarsh, L., Upham, P., Poortinga, W., McLachlan, C., Darnton, A., Devine-Wright, P., Demski, C., & Sherry-Brennan, F. (2011). Public attitudes, understanding, and engagement in relation to low-carbon energy: a selective review of academic and non-academic literatures. Report for the RCUK Energy Programme.

- Zmerli, S., & Newton, K. (2017). Objects of political and social trust: Scales and hierarchies. Handbook on Political Trust, 104–124. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782545118.00017